A crane goes up. A house goes for sale. A new stadium is built on an old neighborhood. A city people call home changes.

For centuries, land has been embezzled from native hands while being misconstrued by their new bearers. This is nowhere more apparent today than in the dense urban centers of society. While settler colonialists in spaces like the americas and Africa use to make these moves outwardly apparent, pillaging peaceful bodies and erecting walls to establish new boundaries of ownership, the urban colonialists of today work much more covertly behind the walls of legality and corporatization. Entities like real estate developers have worked in tandem with other agents of control, like local governments, to in essence reconstruct the vibrant and diverse urban center into a network of property that sits either “unused” or as net detriment to the urban zones it inhabits. Homes are devalued to make way for sports arenas, and high rise condos sit as property based assets waiting for liquidity. What this exploration hopes to accomplish is to make visible the underhand, colluding, and backdoor methods that urbancolonialist institutions like developers use to “rightfully” take land from the public, and then place that information in the hands of those who need it most: those living in those areas.

Since the first peoples were dispossessed from their homes, there has been a continuous cycle of conquest and colonialism. Lands are seen as capital and commodified by those who wish to use it for the advancement of their own agendas. While before it was land that was expropriated from Indigenous communities and labor from enslaved African peoples, scholars like Andrew Hersher posit the same dispossessions are occurring against working class and disadvantaged communities of color2. This ties back to the inherent bias in the capitalistic global system we call home, where lands are ceded by controlling powers to those that can use them most “industrious and rational”v (and that never means living a healthy and social urban life).

This transmogrification of lands that once worked harmoniously with their co-inhabitors is seen in a variety of means within the colonialist model. Take for example Detroit, a once vibrant urban center of commerce and diverse communities. Much of the city has now been colonized by developers, buying up empty and lived in structures only to raze them for surface parking of cars1. No longer are colonialists satisfied with lands working in tandem with communities, choosing instead to turn them into pure generators of profit that feed back into a cycle of dispossession.

Why is there nothing here?

City thought this was a more productive use of the land they took

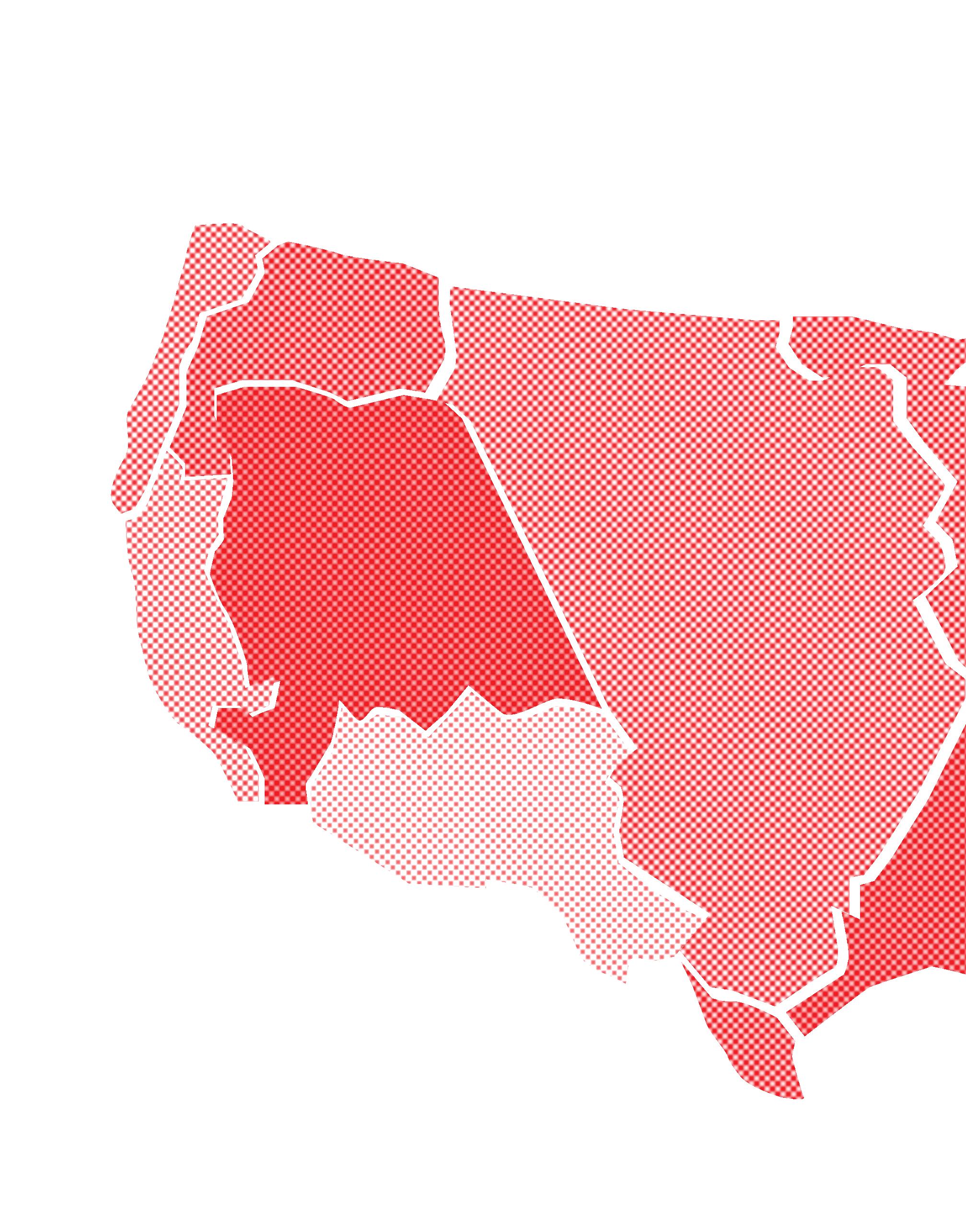

It is important to note at the top of this publication that all lands owners mentioned are not the true native stewards of these spaces, and at the same time the cycle of colonization has been happening long before the life of urban society has been challenged. Purposefully we do not use the word “decolonization” when referring to the repatriation of lands, as true repatriation (and rematriation for that matter) does not involve furthering a settler narrative which is already in progress. Heeding the words of authors like Tuck and Yang who analyze these differences, using decolonization in any way other than the true return of lands to their native stewards and the collective recognition of how land our relationship to it has always been consciously different to traditional understandings6.

This land is not ours, its theirs Desert

NW Coast

Plateau Plains

Understanding and learning from indigenous populations is a careful and dangerous line to follow. Often colonists will “adopt” the native ways relations with and around the land, but many times this becomes an evasion towards an unearned innocence to the atrocities that led us to the current paradigm6. By flushing out these ideas here, we do not posit that the issues we discuss later in the piece amount to decolonization, but rather that they begin to move the narrative in a direction away from outward colonial collection and towards a more democratic model of land and land ownership.

Original Map Credit: National atlas. Indian tribes, cultures & languages12

Gentrification is a word so embedded in the tactics of invisible colonist discourse that it is hard to separate the collective and the marketed connotation. It a term so wildly generalized through different lenses that much of the meaning can be lost through translation. There comes a certain point where the revitalization and development of a community shifts from working with to working against. Much of this comes down to the framing of community and culture, and once that culture begins to be pushed away from the native community that calls it home identity becomes the resource siphoned by the capitalist system11 .

Original

Original

How do you separate out and find a balance between an improvement in community living / neighborhood improvement and the encroaching onset of gentrification. Balance comes from finding new tools for cities to understand and grasp a wider network of outcomes. These include methods such as using new data, building social and physical infrastructure, strengthening local culture, and engaging with community members11. It is important to note that these tools are not only agents for positive social change, as the same data and framing can be construed by developers to paint a wildly different picture of a neo-liberalist urban future.

One of the most powerful,but seldom mentioned, forces pushing and degrading the native urban network is economics. Capitalism is founded on a system of revenue and surplus, and that surplus as of late has been funneled back into urban centers by private entities as a way to pull more revenue into their stream. Great public works and skyscraper buildings are no longer collective efforts of person and state, but rather our current neo-liberal economies places the power to rapidly urbanize and destroy the city in the hand of those who control that economic surplus. David Harvey labels this rightfully so as “the right to the city”, which to claim ownership of is to claim power over the forces of shaping urbanism in our cities4.

The only way to change the way cities have been rapidly colonizing land away from their stewards and transmuting it into global capital is through the democratic reclamation of the “right to the city”. Preventing the rapid accumulation of property and the dispossession there in from natives is the first step towards a more unified and democratic development of urban spaces4. It is projected that by 2050, 89% of the population of the US will live in urban areas3 , the power to shape those areas should not fall to the hands of those that will milk it for value.

In nearly every big city in the US, countless high rise luxury residences are being built. While this means more and more housing, rarely does it mean more people living in those areas. Built as the new age of capitalist colonization “zombie” urbanism seems to be the empty promise of choice. The phrase was coined by Matthew Soules who in his piece discussed the numerous ways in houses are no longer being built for inhabitation, but instead stand as pieces of capital speculation to generate liquid income for the wealthy8. This creates a settler colonial commodification and ownership of the land built on the back of institutional policies that promote this investment.

This trend can be seen clearly by anyone looking up in NYC. The numerous high rises built in the last decade sit over 50% vacant, while their construction was subsidized through tax breaks in exchange for the creation of un-affordable “affordable housing”13. This dispossess now two groups of urban natives, and provides no where near the social and physical infrastructure to make reconciliations for the lands they colonized.

-Note the natural beauty, history, and human experience

A very clear example of this phenomenon is presented in the two images portrayed here. They are both of the same place, Historic Mill City Ruins Park in Minneapolis. The top shows a historically engaging and social space of exploration, while the right portrays an almost apocalyptic rendition of the space crumbling and overgrown as though out of a movie10. That image is also one of the first images to come up when one searches “ruin porn”, putting a great smear over the great social legacy of the space.

-Note the focus on crumbling ruins, abandonment, and feeling of age

There is no tactic used more often in the argument of redevelopment and urban-colonialism than that of “Ruin Porn”. Originally coined by a blogger in 2009 criticizing portrayals of Detroit,the term refers to the constant expression of urban futures through the lens of a yet unreached fall of the anthropocentric. Used by entities in the same line of argument as previously mentioned, framing the urban center as destitute in need of capitalistic management. This ignores the obvious point of how these neoliberal policies and practices were the ones to put these structures in a state of disrepair. Iyko Day succinctly describes this phenomenon as these ruling entities depicting nostalgia for a lost future rather than call-to-arms against the historical and political conditions of our present5. All of these are rooted in factors of race and the urban colonial desire to conquer the “underutilized lands”

While many of the invisible forces and moves made within the urban fabric have been antagonistic against native lands and the will of residents, it is important to mention those similar forces working for the positive. While building density and neoliberal systems of control have been growing, at the same time there has been a resurgence of public support for the creation of social infrastructures. Ranging from parks, public libraries, and community centers, these spaces of public create meaningful social interaction against the will of colonial forces. These “Places of the People”, as labeled by Eric Clineberg in his study of these spaces, project remediation of land abuses into the neighborhood fabric by creating unseen networks community support and spatial improvement7.

While a modern repatriation of the land back to their native stewards might be extremely difficult, in the current neo-liberal climate the collective caring of the spaces that now inhabit that land and might be closer to that mutual benefit. Communal support for pieces of public infrastructure like parks and libraries push narratives away from urban rot and enterprise repossession by urban colonialists.

While the conversations of these issues normally consist of academic papers or institutional arguments, the target audience of this piece is the resident and its primary goal is visibility. Having a piece that can be published and dispersed amongst a range of communities creates conversations long after the first, and can become a catalyst for deeper exploration on the topics brought forward. Through the lenses of decolonization, gentrification, and neoliberalist urbanism, the inherent and historically founded power structures embedded in our legal and economic system favoring the corporation over the native become visible.

-“Detroiters for Parking Reform.” Detroiters for Parking Reform, October 13, 2021. https://www.reformdetroitparking.org/.

-Andrew Herscher, “Settler Colonial Urbanism: From Waawiyaataanong to Detroit at Little Caesars Arena,” in Between Catastrophe and Revolution: Essays in Honor of Mike Davis, eds. Michael Sorkin and Daniel Bertrand Monk (New York: OR Books, 2021)

-Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. 2021. “U.S. Cities Factsheet.” Pub. No. CSS09-06.

-David Harvey. “‘The Right to the City.’” Essay. In The City Reader, 270–78. London: Routledge, 2016.

-Day, Iyko. “Ruin Porn and the Colonial Imaginary.” PMLA/ Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 136, no. 1 (2021): 125–31.

-Eve Tuck (Aleut) and K. Wayne Yang “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, Society 1(1, 2012): 1-40.

-Klinenberg, Eric. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. New York, NY: Broadway Books, 2019.

-Matthew Soules, “Zombies and Ghosts,” Places Journal, May 2021. Accessed 20 Apr 2022. Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017

-Pham, Diane. “Ruin Porn: An Internet Trend That Is Older than You Think.” ArchDaily. ArchDaily, November 27, 2014.

-Saunders, Pete. “The Scales of Gentrification: Cities Strive to Find the Balance Point between Revitalization and Gentrification. (Cover Story).” Planning 84 (11): 16–23.

-Sturtevant, William C, and U.S Geological Survey. National atlas. Indian tribes, cultures & languages: United States. Reston, Va.: Interior, Geological Survey, 1967. Map. https://www. loc.gov/item/95682185/.

-Urbi, Jaden. “Why New York’s Billionaires’ Row Is Half Empty.” The B1M, December 15, 2021. https://www.theb1m.com/video/whynew-yorks-billionaires-row-is-half-empty.