EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

While central to policy, programmatic, and research initiatives, the perspectives of global peacebuilding actors are rarely interrogated. Global peacebuilders — such as those engaged with the United Nations and global peace consortiums — are often regarded as experts in peacebuilding policy, peace promotion, and/or peace education. They play a critical role in bridging communication gaps between local, state, and international levels, yet bring their own assumptions to identifying the drivers of everyday peace. This calls for innovative ways to clarify how global peacebuilders think about pathways to peace and build a shared understanding of peacebuilding goals in conflict-affected societies.

We convened four groups of global peacebuilding actors, engaging them in a visual, participatory known as Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping. Each group engaged in focus group discussion and drew a ‘mental map’ representing their consensus on the variables of importance and perceived causal drivers of everyday peace. The four maps represent visual data amenable for thematic analysis and semi-quantitative comparison. Simulation models illustrate divergent perspectives among global experts on what drives conflict and peace. A lack of conceptual clarity — mapping pathways to peace in ways that fail to be clear, cohesive, or inclusive — is a challenge to policy, research, and programming work.

Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping exercises enable stakeholder groups to visualize their assumptions, identify points of consensus and divergence, compare perspectives and sharpen theories of change. They are a valuable tool for generating policy dialogue and guiding decision-making on system change. Crucially, they support stakeholder analyses across diverse groups — global peacebuilding experts, local peacebuilders, and local communities conflict-affected communities — helping to clarify what drives everyday peace. We

encourage policymakers, practitioners, and researchers to conduct cognitive mapping exercises within and across global organizations. This brief exemplifies an innovative way to promote dialogue, clarify understanding of policy-oriented and programmatic goals, and discuss system change for peacebuilding efforts.

Keywords

Everyday Peace, Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping, Participatory Research, Peacebuilding, System Change, Theory of Change.

KEY INSIGHTS

» The perspectives of global peacebuilders are under-examined, yet vital to understanding how global actors frame pathways to peace in conflict settings.

» Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping enables stakeholder groups to visualize their assumptions, identify points of consensus, compare perspectives, and sharpen theories of change.

» We present four maps and a simulation model to illustrate that global experts hold divergent or elusive perspectives on what drives everyday peace. A lack of conceptual clarity — mapping pathways to peace in ways that fail to be clear, cohesive, or inclusive — poses a challenge for programmatic policy.

» Participatory mapping exercises clarify assumptions and theories of change, enhancing program design, policy coherence, and dialogue within and across organizations.

BACKGROUND

Everyday Peace

The term ‘everyday peace’ captures the habitus of ordinary life in conflict or post-conflict settings. Roger Mac Ginty defined everyday peace as “the routinized practices used by individuals and collectives as they navigate their way through life in a deeply divided society.”1 A research focus on everyday peace has helped to clarify how peace is envisaged by local peacebuilding actors and by communities impacted by violence, insecurity, and discrimination. What has been rarely interrogated are the perspectives of global peacebuilders, in charge of peacebuilding policy, peace promotion, and peace education. This perpetuates asymmetrical power dynamics in humanitarian and international development circles, often replicating colonial legacies regarding whose knowledge will count when defining local, state, and international needs and priorities at times of conflict and peace. 2 Global peacebuilding actors are often understood by international organizations and governments to be ‘experts’ in research, policy and practice, building peace on behalf of conflict-affected communities. They often play a critical role in bridging communication gaps between local community members and the representatives of international or state institutions. However, global experts will bring their own set

of assumptions to a peacebuilding agenda and to stakeholders’ problem-solving discussions: global peacebuilders may not espouse the same vision of everyday peace as local conflict-affected communities, nor identify the most consequential pathways to peace. Moreover, policy-makers and practitioners may seldom have the opportunity to think consensually and systematically about tangible ways to make a difference. This calls for innovative ways to understand how global actors frame the pathways to everyday peace and build a shared understanding of policy-oriented goals.

Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping

We used the Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping (FCM) methodology to discuss the central question of “What factors impact everyday peace?” with global peacebuilding experts. FCM is a participatory research tool used to generate ‘mental maps’ of stakeholder knowledge to enhance decision-making and model future scenarios of change.3-6 Participants engage in a focus group discussion to co-create a ‘mental map’ that helps visualize how causal relationships are perceived. In the course of discussion, they generate and define variables (e.g., drivers of everyday peace), and build a visual ecosystem, drawing direct/indirect links across variables (with positive/negative arrows), assigning relative (positive or negative) weights to each arrow, and coloring the map to categorize thematic domains. Use of an online platform (https://www.mentalmodeler. com) helps to build maps in real time, in sessions that last between 90 and 120 minutes. The online platform also helps to generate semi-quantitative analyses of map characteristics and scenarios that simulate the effects of system change.4 For example, Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping has been used to compare expert with other stakeholder viewpoints, revealing how diplomats, professors, students, refugees, and ordinary citizens everyday peace in Mauritania.7 Cognitive mapping has also been used to understand factors relating to peace and social cohesion in urban environments,8 to the impact of conflict on food systems,9 and to improve data quality for research in post conflict regions.10

STAKEHOLDER MAPS

We convened four stakeholder groups of global peacebuilders. Two were convened at the headquarters of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). The other two were convened at the University for Peace (UPEACE), whose establishment was approved by the United Nations General Assembly in Costa Rica, and at an international meeting of the Early Childhood Peace Consortium (ECPC) in Türkiye to build evidence and advocacy for inclusive peace.11 Mapping sessions were facilitated by two co-authors, one of whom (lead author) was present for all four mapping exercises (March-September 2024). Each session lasted about 90 minutes and included between 8 and 15 participants. Because each group included participants with diverse national backgrounds, organizational roles, and lived experiences of conflict, the mapping exercises carried credibility in showing why it is important to build a shared mental map of peace. We analyzed the four maps in terms of visual knowledge representation regarding the perceived causal drivers of everyday peace. The groups are anonymized, at the request of some participants, to avoid associating their map with a specific institutional position. We redrew the digital maps, created in MentalModeler, to feature variables according to

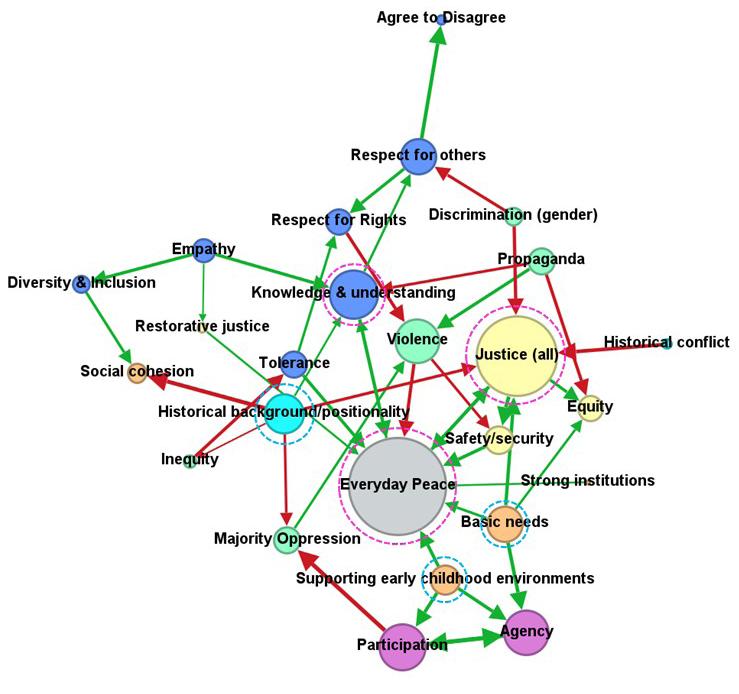

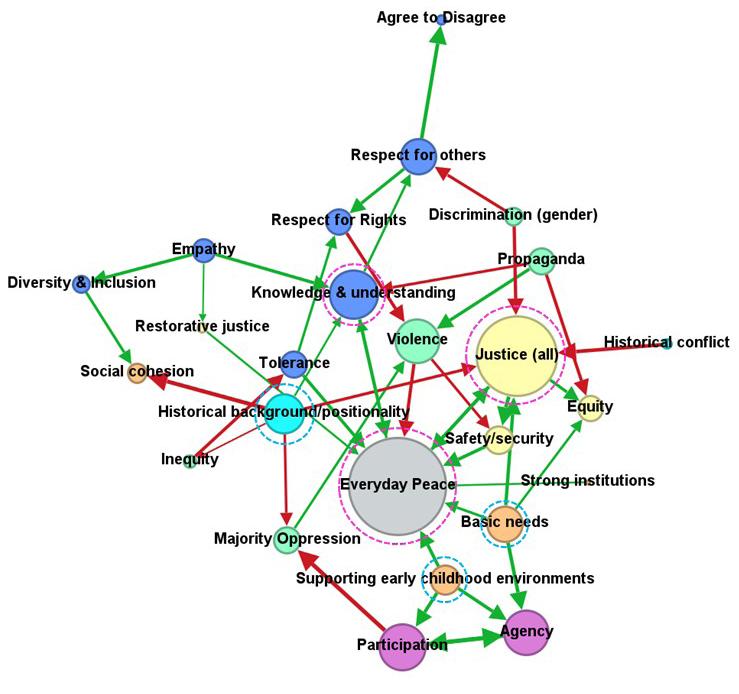

their relative importance (centrality), as circles of different sizes (reflecting the number of incoming and outgoing arrows). Each map reflects how participants thought of positive and negative connections, as links representing perceived causality, and how they grouped variables that conceptually went together. Here, we examine how groups of experts see everyday peace, in terms of connecting to individual, community, and/or state-level variables. For example, Group 1 reached consensus that everyday peace is largely shaped by individual and community-level dynamics rather than formal state institutions (Figure 1). One of the most important variables is this map is ‘justice’ — which for participants, included “environmental justice, social justice, and economic justice” as well as community-based systems of justice. Indeed, defining justice proved challenging, as did tracing clear connections between justice and peace, as group members grappled with the complexity of the peace ecosystem. Their definition of everyday peace emphasized “understanding the other, trying to put yourself in the other’s shoes, trying to build that bridge from yourself to the other.” Respect for difference and community voice figured prominently in the themes they saw as central to everyday peace.

: Map showing everyday peace in terms of factors and perceived causal connections. This group drew two large variables (everyday peace and justice). Historical background/positionality, basic needs, and supporting early childhood environments were impacting (driver) variables with direct influence on everyday peace.

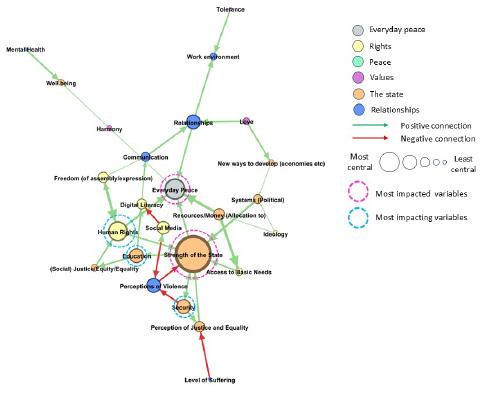

For their part, Group 2 saw ‘trust’ as the most significant variable in the landscape of peace (Figure 2). Trust was strongly linked to social cohesion and security, but only indirectly influenced everyday peace.

Participants emphasized that both community-level actors and state-level factors mattered for everyday peace. For example, they thought that women held an influential role in promoting peace, as did state institutions through the rule of law and justice. The

group described everyday peace as “living your life the way that you want and having opportunities to participate in decision-making processes” — for reducing discrimination and promoting social cohesion.

Figure 2: Map showing everyday peace in terms of factors and perceived causal connections. This group drew one large variable (trust) that indirectly influenced everyday peace. Intolerance and rule of law directly impacted trust, while inequality/discrimination directly impacted social cohesion.

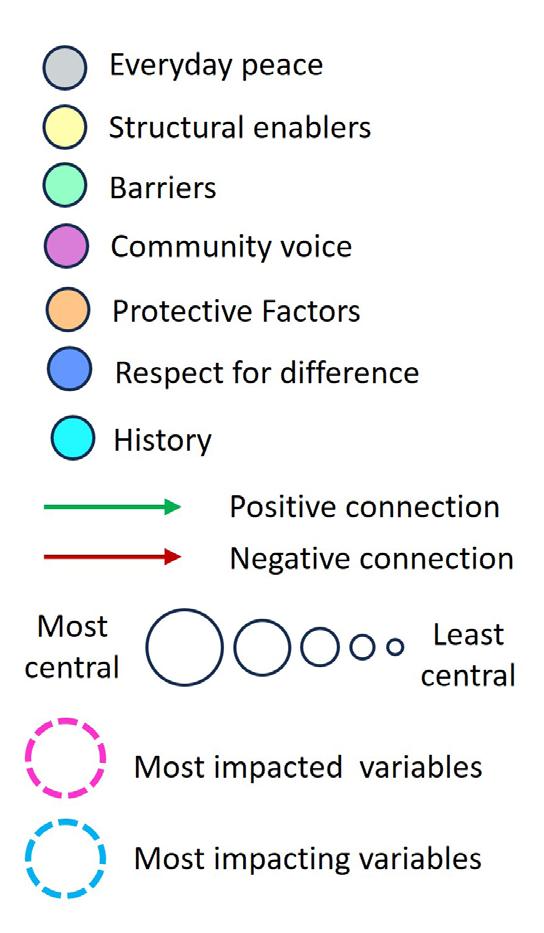

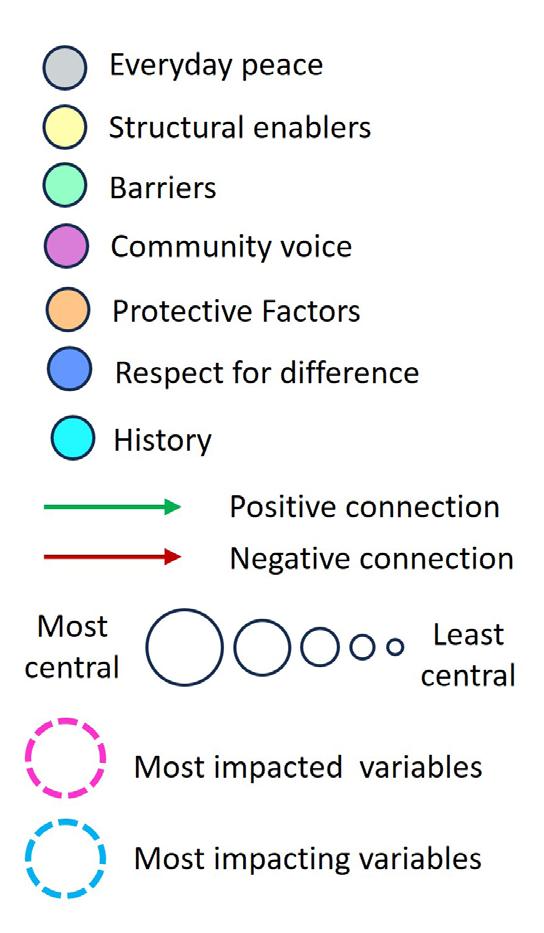

By contrast, Group 3 placed central emphasis on the ‘strength of the state’ and ‘human rights’ as key variables for everyday peace (Figure 3). Participants defined everyday peace as being closely tied state fragility, specifically “how fragile or how strong is a state to address the basic needs of its citizens.” They discussed the state structures that provide access to education, justice, money, and security, as well as the promotion of human rights in contexts where institutional legitimacy is often contested or weak. They also highlighted the roles of social media, digital literacy, and freedom of assembly within the peace ecosystem. This reflected a broad understanding of peace as requiring longterm investments in civic knowledge, an element often overlooked in high-level policy discourse.

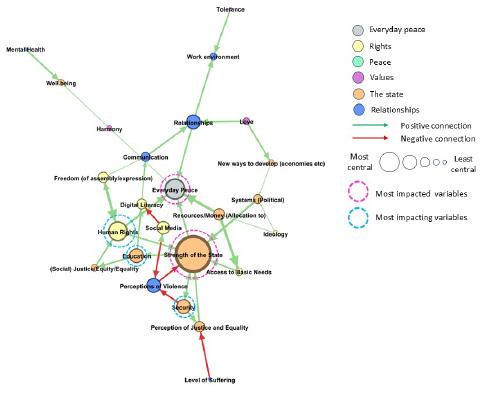

In developing their map, Group 4 participants reflected that many variables were necessary, but none alone were sufficient to influence everyday

peace (Figure 4). They identified the lack of legal and political rights, as well as a sense of ‘unpredictability,’ as key risks, while highlighting justice, economic opportunity, and freedom from violence as essential enablers of everyday peace. They wrestled with how links between variables should best reflect direct or indirect causality - for example, how freedom of expression could promote a ‘sense of justice,’ which in turn would foster both everyday peace and ‘hope for the future,’ or how economic opportunity would foster ‘hope for the future,’ thereby strengthening everyday peace. The map integrated perspectives on how economic, social, and political dimensions of empowerment intersect with psychological empowerment for people living in conflict-affected societies, anchored by a definition of everyday peace as the “opportunity to find self-fulfillment and growth in a community and feel valued within that community.”

Figure 3: Map showing everyday peace in terms of factors and perceived causal connections. This group drew one large variable (strength of the state). Human rights, education, and security were the most impacting (driver) variables in the system.

Figure 4: Map showing everyday peace in terms of factors and perceived causal connections. For this group, impacting (driver) variables were freedom from violence, freedom of expression, not having legal & political rights, corruption, economic opportunity, and unpredictability.

SCENARIO OF CHANGE

We turn to generating a hypothetical scenario that offers insights into theories of change. Importantly, Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping offers a participatory approach to systems analysis. For each map, the Mental Modeler software generates a matrix which defines system dynamics by listing variables and translating their interconnections into quantitative values (+1 and -1).3-6 Hypothetical scenarios allow us to better understand how groups of respondents perceive pathways to change and identify potential intervention points. For example, we ran a scenario maximizing

(to +1 value) the variables participants had labeled ‘justice,’ ‘grievance mechanisms,’ ‘restorative justice,’ and ‘sense of justice’ to predict how prioritizing justice could impact everyday peace in their respective maps.

Figure 5: Hypothetical scenario showing the impact of activating variables related to state ‘justice’ in the peace ecosystem. The scenario is run for each group of participants in turn. The percentage values indicate relative change. For example, group 1 sees impacts that include decreased violence, as well as positive system change. All but Group 3 see direct impacts on everyday peace, although these are substantive only for Group 4.

Figure 5 illustrates the hypothetical impacts of activating the justice-related variables in each of the four maps. The scenario suggests that strengthening systems of justice will lead to system change, although impacts are perceived as substantive only for Group 4. Notably, from the perspective of Group 3 participants, activating justice predicts modest effects on human rights, security, and strength of the state, with no consequential change on everyday peace per se. This highlights that global experts hold divergent perspectives when mapping connections between justice and peace, reflecting how they grappled with elusive definitions, complex interconnections, and drivers of change. For example, participants debated how state justice, social justice, and respect for rights can operate as causal drivers within complex systems. In these mapping exercises, justice is consistently identified as a key variable, yet it remains ambiguously understood and unevenly connected to central elements of the peace ecosystem. A lack of clarity poses challenges for policy, research, and programming efforts aiming to advance coherent and inclusive approaches to peace and justice.

CONCLUSION

We have highlighted a diversity of perspectivesand divergence — across groups of peacebuilding experts engaged in United Nations and global peace consortiums. Indeed, peace efforts invite an understanding of complexity at every level of society, even among groups of experts responsible for shaping global peacebuilding policy, practice, and peace education efforts. We see, for example, a different emphasis being placed on notions of justice vs. trust, human rights vs. economic opportunity, and strength of the state vs. social cohesion. Such a diversity of views might well reflect differences of lived experience, field of expertise, organizational mission, or situational context. However, differences in perspectives in how global peacebuilders think about peace are consequential in themselves, as they structure efforts to promote peace in diverse conflict-affected settings. The issue is that peacebuilding experts might approach programming efforts to advance peace and justice in ways that are not always clear, cohesive, or inclusive. Indeed, creating space for discussions

that carefully identify which variables are key to system change can be very challenging. Group 3 participants, for example, reflected that they seldom had the opportunity to discuss, among themselves, how organizational goals connected with their lived experience of peace and conflict. The mapping exercise was beneficial to them as an internal tool for reflection, clarification, and learning. For their part, Group 2 participants spoke confidently about the links between trust, social cohesion, and everyday peace, but were less certain how these connections translate into tangible outcomes across different conflict-affected contexts. Groups 1 and 4 mapped different pathways to peace, with strikingly different implications for how strengthening systems of justice might shape everyday peace. Where knowledge about peace remains ambiguous or fragmented, divergent perspectives can create disconnects within and across organizations. Unless explicitly addressed, these gaps in knowledge can lead to unintended or unrecognized misalignments in theories of change. They can also entrench disconnects between how international experts, local peacebuilders, and local citizens understand sustainable peacebuilding.7,12

Future iterations of Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping could deepen understanding of shared goals and decisionmaking. They would leverage a participatory approach to make stakeholder knowledge ‘visible’ to stakeholders themselves, as they engage in discussion, build shared understanding, and map often-contested concepts. With respect to everyday peace, this methodology helps clarify complexity and, ideally, “thread the needle” between local, state, regional, and international peacebuilding priorities. 2,5,6 There is also potential in employing cognitive mapping tools to support

peacebuilding in other ways, such as leveraging digital outputs for local and regional knowledge-sharing and fostering stakeholder engagement across greater distances and scales.13 Participatory tools can be applied flexibly, to identify perceived relationships of influence and problem-solving strategies.14

POLICY RECOMMENDATION

We encourage policymakers, practitioners, and researchers to engage in cognitive mapping exercises within and between organizations, in order to promote discussion and interactive dialogue on pathways to peace. Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping offers an innovative way to make stakeholder knowledge explicit. It is helpful to examine gaps in consensus and to promote dialogue within and across groups. It may also be valuable to pair this mapping tool with other participatory, digital, and/or quantitative approaches, in order to deepen consensus-building and decisionmaking for reaching tangible outcomes in localized settings. This will build a shared understanding of policy-oriented and programmatic goals as well as clarify the theories of change for peacebuilding efforts.

Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping session conducted at the University for Peace, Costa Rica.

HOW TO CITE

Panter-Brick, C.1, Logan, S.1, Qtaishat, L.2 , Faieta, J.1, Fallon, C.1, Hanoz, S. 3, Khoudour, D.2 , Lancaster, I. 4, Rashid, U.5, Salcedo, A.5, Wild, M. 5, Williams, B.1, Simon, D.1, Wall, K.4, Weir, B.1 (2025). How Global Peacebuilders Think: A Tool for Policy Dialogue and System Change, Policy Brief, Peacebuilding Initiative, Jackson School of Global Affairs, Yale University

Co-authors’ affiliation:

1 Jackson School of Global Affairs, Peacebuilding Initiative, Yale University

2 Independent Consultant

3 Early Childhood Peace Consortium (ECPC), Türkiye

4 United States Institute of Peace (USIP), Washington DC

5 University for Peace (UPEACE)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Jackson School of Global Affairs (Peacebuilding Initiative) and the MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies (Collaborative International Research Grant) for generous funding support.

REFERENCES

1. Mac Ginty, R. (2014). Everyday peace: Bottom-up and local agency in conflict-affected societies. Security Dialogue, 45(6), 549-564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614541461

2. Firchow, P. (2018). Reclaiming everyday peace: Local voices in the measurement and evaluation after war. Cambridge University Press.

3. Barbrook-Johnson, P., and Penn, A.S. (2022). Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping. In: Systems Mapping. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-01919-7_6

4. Gray, S.A., Gray, S., Cox, L.J., and Henly-Shepard, S. (2013). Mental Modeler: A Fuzzy-Logic Cognitive Mapping Modeling Tool for Adaptive Environmental Management, 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 2013, pp. 965-973, doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2013.399.

5. Tbaishat, D., Qtaishat, L., Eggerman, J.J., Panter-Brick, C., and Dajani, R. (2025). Mapping the perceived impacts of a social innovation program on women’s agency and life satisfaction. Frontiers in Sociology 10:1527841. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2025.1527841

6. Panter-Brick C, Qtaishat L, Eggerman JJ, Thomas, H, Kumar P, and Dajani R (2024). Volunteer programs, empowerment, and life satisfaction in Jordan: mapping local knowledge and systems change to inform public policy and science diplomacy. Frontiers in Sociology 9:1371760. https://www.frontiersin.org/ articles/10.3389/fsoc.2024.1371760/full

7. Panter-Brick, C., Williams, W., Abdem, A.E., Dhehby, K., Coulibaly, Y., and Eli, T.B. (under review). Everyday peace in Mauritania: A systems mapping, visual approach of stakeholder experience. Frontiers in Political Science.

8. Setiawan, W., and Sutrisna, M. (2010). Investigating the potential of built environment in promoting social cohesion within an urban environment. In Procs 26th Annual ARCOM Conference, September, pp. 6-8.

9. Dowd, C., Polzin, S. S., Gleason, K., Yang, R., Narang, P., and Patel, R. (2024). Conflict’s impacts on food systems: Mapping available evidence of interactions. Journal of International Development, 36(4), 21522171. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3899

10. Dhattiwala, R. (2017). Mapping the self: challenges of insider research in a riot-affected city and strategies to improve data quality. Contemporary South Asia, 25(1), 7-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09584 935.2017.1297385

11. Leckman J., Panter-Brick, C., and Salah, R. (2014). Pathways to Peace: The Transformative Power of Children and Families. Strüngmann Forum Report, volume 15. MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit. edu/9780262549219/pathways-to-peace/

12. Alexander, P., Echavarría Alvarez, J., Brett, R., Holt, V.K., Lombard, L., McWilliams, M., Panter-Brick, C., Picco, E., Thomas, H., Thurston, A., Quinn, J., and Williams, B. (2023). Strategies for Sustainable Peacebuilding: Implementation and Policy. Policy Brief. Yale Jackson School of Global Affairs & Keough School of Global Affairs, University of Notre Dame. https://jackson.yale.edu/wp-content/ uploads/2025/06/MN111062-policy-brief-jackson_sustainable_peacebuilding.pdf

13. Tosunlu, B. H., Guillaume, J. H., & Tsoukiàs, A. (2023). Conflict Transformation and Management. From Cognitive Maps to Value Trees. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.07838.

14. Hoffman, E. A. (2021). Cognitive-Affective Mapping and Digital Peacebuilding. Todo Peace Institute. Policy Brief. https://toda.org/assets/files/resources/policy-briefs/t-pb-111_cam-and-digitalpeacebuiling-hoffman.pdf