BANKS, THE NEW JAGUAR CUB

TRAFFICKING AWARENESS

RESPONSIBLE PET CHOICES

CIGAR ORCHID CONSERVATION

ANIMALS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

TRAFFICKING AWARENESS

RESPONSIBLE PET CHOICES

CIGAR ORCHID CONSERVATION

ANIMALS AND THE ENVIRONMENT

2

12

15

Jeff Ettling, Ph.D., President and CEO

David Hagan, Chief Life Sciences Officer

Holly Ellis, Chief Financial Officer

Nikki Smith, Chief Philanthropy and Community Engagement Officer

Paula Shields, Chief People and Culture Officer

Leanne White, Director of Learning and Conservation Engagement

Kelly Rouillard, Director of Marketing

Rick Holzworth, Director of Support Services

Todd Martinsen, Director of Business Operations

Chuck Ged, Chair

Lucia Lindsey, Chair Elect, VC Capital Campaign

Missy Peters, Secretary

George Mikes, VC Finance & Treasurer

Anne Marie Cushmac, VC Governance

Salmaan Wahidi, VC Animal Care, Conservation and Wellness

Paula Renfro, VC Education

Karen Estella Smith, VC Garden & Art

Kerri Stewart, VC Special Projects & Properties

John Hayt, Honorary Advisor

16 What's New Births, Hatchings, Acquisitions

18 Cigar Orchid Conservation

20 JAX Zoo Tube

21 Animals and the Environment

22 Jaguar Cub

24 Snapshot Society Wild Zoo Animals

Paul Blackstone

Scott Chamberlayne

Jonathan Coles

Donna Deegan (COJ)

Kenyonn Demps

Dan Fields

Wilfredo Gonzalez

René Kurzius

Barnwell Lane

Clint Pyle

Param Sahni

Paul Sandler

Joel Swanson

Scott Witt

Danny Berenberg

Ivan Clare

Dano Davis

Diane David

Lenore McCullagh

Elizabeth Petway

Herbert Peyton

Clifford Schultz

Frank Surface

Janet Vaksdal Weaver

COUNCIL

Martha Baker

J.F. Bryan

Carl Cannon

Howard Coker

Charles Commander

Jed Davis

Matt Fairbairn

Joseph Hixon

J. Michael Hughes

Lewis Lee

David Loeb

Richard Martin

Frank Miller

John A. Mitchell

Thomas Schmidt

Bill Rowe

Carl “Hap” Stewart

James Stockton

Penny Thompson

Courtenay Wilson

For hundreds of thousands of years, some of the most iconic zoo animals like elephants, lions, giraffes, jaguars and others thrived in the wild. Fast forward to 2023, and we can see these same animals dwindling in numbers as their ecosystems rapidly decline. While threats to plants and animal species can come from a multitude of sources including pollution, deforestation, destruction of natural habitats and climate change, illegal wildlife trafficking has also contributed significantly to the problem. Now, groups like the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and other conservation organizations have stepped up to raise awareness to help put an end to the illicit sale and ownership of exotic animals.

Wildlife trafficking is an international environmental crime that is devastating wildlife species across the globe as poachers, traffickers and highly organized global crime organizations relentlessly look to meet a rapidly growing demand. The overexploitation of wildlife can also pose health threats to humans, native species and livestock, especially if it introduces viruses or bacteria that native populations are unprepared to defend against.

The diverse and significant implications of wildlife trafficking, in turn, means that protecting wildlife, forests and fish must be part of a comprehensive approach to eradicating the illegal wildlife trade. That’s why we support dozens of conservation programs for plants, animals and habitats that are important to the future of wildlife and the wild places we all love. We provide homes to some of the most endangered species on earth, and through cooperative reproduction programs with other AZA accredited zoos and aquariums, work to ensure the survival of vulnerable plants and animals. Want to help support our conservation efforts and tackle wildlife exploitation?

With every membership, donation, admission or special event ticket, you help our ongoing efforts. These funds support our daily operations, and a percentage of every purchase goes directly to our various conservation efforts. Read on to learn more about the unlawful purchase and sale of exotic animals from around the globe, the laws and regulations being passed to prevent the exploitation of animals and what we are doing to help!

White-lipped island pitvipers were confiscated by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) as part of a multi-year investigation. Multiple individuals were uncovered attempting to sell approximately 200 snakes that were illegally imported into the state of Florida as part of the pet trade.

See page 16 for more details.

Pets enrich our lives by giving us companionship and pleasure. Studies have shown that they are even good for our health. Pets can provide stress relief, unconditional love and emotional support. They play integral roles in human culture and experience, but it is critical to make responsible decisions when choosing pets.

There are significant differences between domestic and wild animals. Domestic animals include farmed animals and pets such as dogs, cats, horses, pigs, cows, sheep and goats.

These species have been selectively bred over thousands of years to adapt to human environments, provision and control. A wild animal belongs to a species that has not been domesticated. While some wild animals may become accustomed to humans, or “tamed,” a wild animal that is raised by humans does not become domesticated. Most wild animals are not appropriate as pets due to public health and safety, animal welfare and conservation consequences.

“Most wild animals are not appropriate as pets…”

Wild animals can inflict serious and life-threatening injuries. They have natural instincts required for survival in the wild, which often lead to unpredictable bouts of aggression. For this reason, it is particularly dangerous to keep carnivores and primates as pets. In response to growing public safety concerns, Congress passed the Big Cat Safety Act in 2022, which prohibits private possession of lions, tigers, leopards, cheetahs, jaguars, cougars or any hybrid of these species. Another proposed bill, the Captive Primate Safety Act, would similarly prohibit private possession of primates including prosimians, monkeys and apes. Primates not only pose significant risk of injury, but they also carry distinct risks of transmitting viral, bacterial, parasitic and fungal diseases, some of which can be deadly to humans.

Regardless of how adorable they are, wild animals are not domesticated and can pose a risk of injury. A kinkajou famously demonstrated this in 2006. Paris Hilton required a tetanus shot after being bitten.

The Big Cat Safety Act (BCPSA) was signed by the POTUS on December 20, 2022. It is a significant long term achievement for all animal conservation and welfare organizations and prevents the exploitation of big cats. The BCPSA had been introduced every year since 2012. In 2020 it passed the House and later passed in the Senate in 2022.

Regardless of how adorable they are, wild animals are not domesticated and can pose a risk of injury. A kinkajou famously demonstrated this in 2006. Paris Hilton required a tetanus shot after being bitten.

The Big Cat Safety Act (BCPSA) was signed by the POTUS on December 20, 2022. It is a significant long term achievement for all animal conservation and welfare organizations and prevents the exploitation of big cats. The BCPSA had been introduced every year since 2012. In 2020 it passed the House and later passed in the Senate in 2022.

Primates have complex psychological and social needs. Even though they are smart, they're still wild animals and can be unpredictably aggressive or transfer a zoonotic disease. Endangered primates, like this Lemur, do not make good pets.

Wild animals in human care require specialized expertise and extensive resources to thrive. Many people do not have the knowledge or resources to properly care for a domestic pet, much less a wild animal. Failure to provide species-appropriate environment, nutrition, socialization and veterinary care often leads to physical and psychological damage. Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) accredited zoos usually cannot take in former pets due to behavioral issues and unknown genetics, and most reputable animal sanctuaries stay at or near capacity. This makes placement in professional care difficult or impossible once a wild animal becomes unmanageable in a human household.

Learn more at Not a Pet

“Take the pledge to be an advocate for wildlife…”Lemur

Keeping wild animals as pets can directly and indirectly counter conservation efforts. Millions of animals are illegally captured and traded for the exotic pet trade, many of which suffer and die in the process. Even keeping wild animals legally as pets undermines the message of conservationists who work to educate indigenous people not to collect the local wildlife for pets. When exotic pets are released or escape into non-native habitats, they can become invasive wildlife that has detrimental effects on native species and ecosystems.

Before deciding on any pet, domestic or not, make sure to understand the needs and risks, and objectively assess your ability to be a responsible pet owner. Take the pledge to be an advocate for wildlife and learn more at the Not a Pet campaign, a partnership between AZA’s Wildlife Trafficking Alliance and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW).

In Florida animals from the wild (including injured, orphaned, or abandoned native animals) are never eligible to be kept as personal pets. Learn more at FWC.

Responsibly bred leopard geckos (pictured) can make good pets for future pet owners interested in reptiles. Visiting a local shelter is an excellent way for future pet owners to find domesticated dogs and cats. In all cases, it is important for future pet owners to have very good knowledge of the animals and the ability to meet their care requirements.

Green iguanas, an invasive species, have negative impacts on native Florida wildlife. They eat endangered snails and nickerbean, the host plant of the endangered Miami Blue Butterfly. They are on Florida's Prohibited Nonnative Species List and cannot be kept as pets. Learn more

Green iguanas, an invasive species, have negative impacts on native Florida wildlife. They eat endangered snails and nickerbean, the host plant of the endangered Miami Blue Butterfly. They are on Florida's Prohibited Nonnative Species List and cannot be kept as pets. Learn more

How long have you worked at the Zoo?

I have worked at the Zoo for almost 10 years. What does a day in your shoes look like?

The first thing is to prioritize the work according to need. I usually respond first to emails from Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) or Europe regarding the Okapi Conservation Project as they are six to eight hours ahead of us. I contact my staff to review what they are working on and offer help if they need it. We support conservation projects around the world so all three of us take time to check in with a partner to see how they are doing and if they have any specific needs coming up that they might need funding to implement. That way we can plan our awards and budget for them. We use our Conservation Strategic Plan to guide our decisions on which projects to support. As time permits, I also virtually meet with the staff of the Okapi Conservation Project (OCP) to review program status in DRC and discuss areas of concern. I have led this Project for almost 36 years which has protected the largest population of okapi left in DRC. A good deal of time is spent fund raising for this project. As founder and President of the International Rhino Foundation (IRF) and board member of the Wildlife Conservation Network I respond to requests

for comments on actions being considered by both organizations. I travel to oversee projects I am associated with and to attend board meetings.

I spend a good deal of time participating in meetings at the Zoo to coordinate our activities with other departments and to help support the Zoo’s mission.

I started my zoo career working as a night watchman at the Children’s Zoo in Boston while I was in graduate school at Northeastern University. After receiving my master’s degree in Zoology, I worked as a bird keeper for the Boston Zoological Society at the Stone Zoo. A year later I became Assistant Director of the Children’s Zoo at Franklin Park. I was always fascinated by the Pacific Northwest and after a year at the zoo I loaded up my Newfoundland dog, my 3 boa constrictors, a porcupine (I did my masters work on porcupines and had one as a pet) and a red-tailed hawk (I was an apprentice falconer) and drove to the Okanagan Game Farm in Penticton British Columbia, Canada to work as their education coordinator.

In Canada, I was exposed to wild nature on a grand scale and traveled around BC and Alberta whenever I had a chance. At the game farm I was fortunate to raise two wolves, a black bear, a grizzly bear and a cougar kitten, which gave me insight into four of the most fascinating species of carnivores in North America. My stint in Canada helped me take a position with the New York Zoological Society (now the Wildlife Conservation Society) as curator of a new off-sight breeding center for threatened species (the first of its kind) on St. Catherine’s Island off the coast of Georgia.

I began leading safaris to Africa as a Curator, which began my lifelong love of the people and wildlife of such a diverse continent. I met paper magnate Howard Gilman on a safari to Zambia where we shared a tent and a mutual passion to help wildlife. My wife and I had our first child on the Island which we shared with two other families. After six years when our daughter needed to go to school, I took a position with the Gilman Paper Co. to start the Conservation Center at White Oak Plantation north of Yulee on the St. Mary’s River. For 30 years I led the development of White Oak Conservation Center which became the premier facility for breeding endangered animals, conservation research and training of aspiring biologists. While at White Oak I developed my lifelong attachment to Okapi, rhinos and cheetahs and helped start organizations to support their survival in the wild.

When the Howard Gilman Foundation sold White Oak, my wife and I settled in Jacksonville and that is when the Zoo provided me with office space to continue my

international conservation work. In 2013, Tony Vecchio asked me to become the Curator of Conservation for the Zoo. It is a pleasure to work with all the dedicated, caring and supportive people here at the Zoo.

The okapi is my favorite animal. I have dedicated most of my professional life to making sure okapi have a place not only in nature but also in the hearts and minds of the people living in the DRC.

Now that okapi are no longer exhibited at the Zoo, I enjoy watching the giant otters. Our commitment to conservation in Guyana is reflected in our work with this species at the Zoo and in the wild. My favorite place in the Zoo is the Asian Garden. I try to walk through the garden every day. It is so different; it’s peaceful, a place to reorganize your thoughts.

I developed a fascination with wild places by reading books by explorers and watching movies like the Swiss Family Robinson and all the Tarzan films. As a child I was always collecting turtles, frogs and praying mantis to look at and release. When I was young, I spent my summers with my grandparents in northern Massachusetts on their homestead where I was free to roam and explore,

watching birds and beavers. I worked at a zoo in Hartford, Connecticut during summer breaks in college. My major in college was Biology and Vertebrate Zoology in graduate school; I wanted to learn all I could about our natural world.

Are you native to Florida? If so, where? If not, where did you grow up?

I grew up in Hartford, Connecticut. I was always interested in natural sciences and majored in Biology in college. I went to college in New Hampshire which afforded time to spend weekends in nature. Once we moved south to Georgia in 1976, we loved the wildness we found on the coast. We then moved to White Oak in 1982, and since then my wife and family have called Florida home for 43 years.

What is your favorite part of your career or what is your most memorable experience at the Zoo (or your old zoo)?

I have had so many wonderful opportunities in my life and have met so many amazing conservationists around the world. I cherish being able to breed okapi in Congo and bring three animals to the US that genetically saved the managed population. Also, memories like traveling in a plane with black rhinos from Zimbabwe when a rhino put his horn through the top of the crate a few inches short of the aluminum skin of the plane. A close call.

I am most proud of co-founding several very influential conservation organizations that are making major contributions to conserving wildlife all around the globe - International Rhino Foundation, Wildlife Conservation Network, Okapi Conservation Project and White Oak Conservation Center.

I am an avid kayaker and bird watcher. As I get older, I most enjoy spending time with my family and our dogs outdoors and interacting with our blue fronted amazon parrot, Jellybean, who has been with us for 35 years.

Please share any other comments you would like included in your article (stories, experiences, more about yourself etc.)

I travel a lot. I have been to Africa well over 120 times and each trip is a story of its own. In DRC we engage with the Mbuti pygmies to help conserve okapi in the wild. They are the smallest people on earth, and I am tall, so we present quite a contrast when we are together. Overall, working at the Zoo fills my overwhelming need to be around animals and animal people.

It comes as a surprise to many that we are a non-profit organization. With our mission of “connecting communities with wildlife and wild places” we have staff dedicated to achieving this mission through fund raising efforts. With many exciting changes on the horizon, we have decided to integrate the word "philanthropy" into our fund raising department. The word itself means "love of humanity" and we believe that caring for our world and all species is integral to humankind. The friendly faces of our Philanthropy team have distinct roles in moving the future of our organization forward. We love to talk with Members about their passion for the Zoo, so feel free to say hello when you see us!

• Tamarah Thames Philanthropy Experience Officer

• Brenna Blake Philanthropy Engagement Officer

• Bruce Williams Senior Philanthropy Officer, Grants & Government Affairs

• Nikki Jackson Smith Chief Philanthropy and Community Engagement Officer

• Kamille Cooper Philanthropy Events Officer

• Morgan McClure Corporate Philanthropy Officer

• Maranda Shelton Philanthropy Coordinator

For more information on Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens philanthropy efforts, visit jacksonvillezoo.org/support or call us at (904) 757-4463 ext.196.

Ali, our 33-year-old bull elephant was examined in March by esteemed colleagues from South Africa under general anesthesia for having an infected tusk or "bad tooth." Ali was kept safely asleep for nearly five hours as the specialized root canal was performed by Dr. Gerhard Steenkamp. Dr. Adrian Tordiffe led the anesthetic part of the procedure with the assistance of local veterinary anesthesiologist, Dr. James Bailey, and our zoo’s veterinary team. Under the skilled guidance of Corey Neatrour, Assistant Curator of Mammals, the elephant care specialists worked alongside Ali for many months to ensure our 11,000-pound patient would be properly positioned for the procedure. Like the elephant crew, our animal health team had been coordinating the anesthetic part of the examination since 2022. Sarah Block, our most senior veterinary technician, oversaw the ordering of the equipment and medical supplies needed for such a large patient. Since general anesthesia is not commonly performed

Since Ali needed to lie down for such a long period of time, he required the assistance of a crane to help him up to his feet. While this was a high-stress situation, we had planned for all scenarios and were able to safely assist him to ensure a successful recovery. After the procedure, Ali continued taking pain medications and has been eating well. We are grateful to our elephant care specialists, the animal health and nutrition team, the leadership team, the executive board, and the entire zoo crew for coming together flawlessly for such a “huge” procedure. Most of all, a big thanks to Ali for being one of the most magnificent and cooperative animals with whom I have ever worked. This was the epitome of teamwork. Thank you for supporting the zoo to provide the “ivory tower” of medicine and care for our animals.

in adult elephants, we invited colleagues from many facilities to participate in this monumental procedure. The combined medical teams placed several IV catheters which delivered 132 liters of IV fluids. Ali also had an endotracheal tube placed in his trachea, or windpipe, to ensure his lungs were properly oxygenated while he was lying on his side. A team of nearly 30 people closely monitored his vital signs, and an additional 30-plus members from animal programs, animal nutrition, horticulture, facilities, and more participated in many essential roles throughout the procedure.

Photo: John Reed

Photo: John Reed

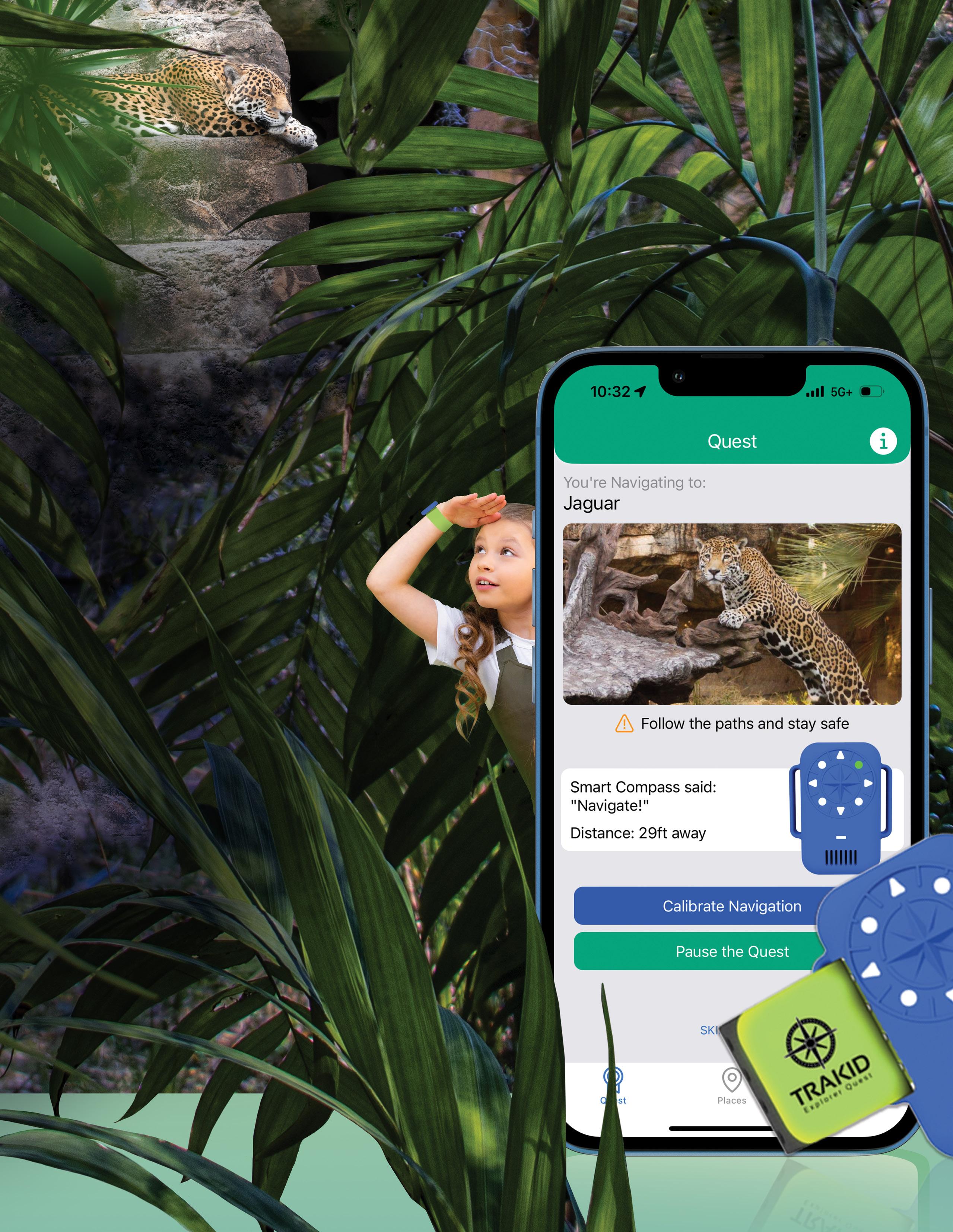

DIGITAL SCAVENGER HUNT

Interactive fun creates a curiosity for learning. As Nature Agents, you can discover, learn, and bond together on a digital scavenger hunt using the NEW Explorer Quest app!

LEARN MORE AT jacksonvillezoo.org

DOWNLOAD EXPLORER QUEST APP MANUALLY OR SCAN

POWERED BY

COMPASS PAIRS WITH MOBILE APP

POWERED BY

COMPASS PAIRS WITH MOBILE APP

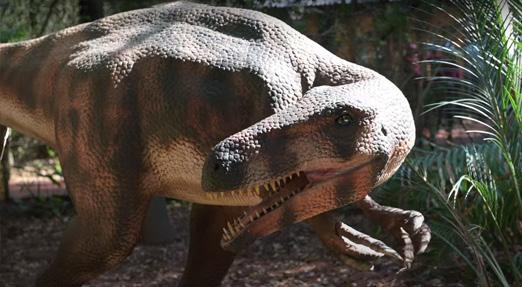

Travel back millions of years to experience the thrill of the prehistoric age of dinosaurs. Along the way, join forces with our team of educational scientists to unravel the environment dinosaurs lived in and the plants they consumed. Come and see 18 of the most fascinating dinosaurs including Triceratops and the mighty Tyrannosaurus Rex.

Carnivores, herbivores or omnivores? Test your dinosaur knowledge with fun and fascinating activities at Dinosauria. Learn about paleobotany—the study of terrestrial fossils including the study of prehistoric fossils, and how plants from prehistoric ages are ancestor species to those found in Florida!

Journey along paths with full-scale, scientificallyaccurate animatronic dinosaurs with realistic movements and roaring sounds. Find out how dinosaurs evolved over time, where they lived, how they behaved and the discoveries paleontologists and paleobotanists have made about their habitats.

Kids can hone their artistic skills with the Drawing Alive Digital Game by coloring dinosaurs and watching them digitally come alive on screen. Plus, artwork is a take home souvenir for kids to enjoy.

Disnosauria is part the Total Experience package. Members will also be given the exclusive option to purchase Dinosauria a 'la carte, on-site only.

Presented by

By Donna Bear, Curator of Species Management and Jasmine Alvarado, Species Management Officer

By Donna Bear, Curator of Species Management and Jasmine Alvarado, Species Management Officer

The white-lipped island pitviper, along with the eastern diamondback rattlesnake, large-eyed cat snake, two-striped forest pitviper and western Gaboon viper acquired earlier this year, were confiscated by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) as part of a multi-year investigation. Individuals were uncovered attempting to sell approximately 200 snakes (24 different species) that were illegally imported into the state of Florida as part of the pet trade. The FWC has strict permitting laws and regulations regarding the captivity, breeding, importation and sale of venomous and non-native reptiles.

The venomous, white-lipped island viper is native to Indonesia and BaliTimor-Leste. While typically green, there are also yellow and blue variants. The beautiful viper can only be found on Komodo Island. Arboreal, they spend the majority of their lives in trees. Their coloring helps them camouflage, providing the perfect advantage to capture their prey, like small birds, frogs, lizards and rodents. They can inhabit tropical forests, dry woodlands or rural areas, depending on where they can find food. The white-lipped island viper is ovoviviparous, meaning the female will give birth to live young after having grown within individual eggs inside her. Once born, these vipers are immediately independent, but they are also ready to defend themselves. When threatened, they will open their mouth showing their venom-filled fangs and curve their body into an s-shape, ready to strike at any second. While a newborn viper bite might not be fatal, it can cause pain, swelling and internal and external bleeding. Heed its warning and stay back.

(Bugeranus carunculatus)

One of the largest cranes in the world, the wattled crane can grow up to 5.7 feet tall with a maximum wingspan of 7.9 feet wide with an average weight of 18 pounds when fully grown. Native to sub-Saharan Africa, the wattled crane thrives best in wetlands. Their long beaks are perfect for digging through the soil, foraging for insects, snails, small vertebrates and various aquatic vegetation. Breeding season varies depending on water levels since the wattled crane builds their nest by piling vegetation into a mound with a small moat surrounding it. The clutch size is the smallest of all cranes, usually just one egg, but on occasion two. The incubation and fledgling period of the egg and subsequent chick is the longest of any crane. Incubation lasts for 33 to 36 days then in 90 to 130 days the chick is finally fledged. When hatched, the wattle crane chick already has a slightly developed wattle. In captivity, the wattled crane does not always breed successfully, so we feel incredibly lucky to have another chick to add to our animal population here at the Zoo.

(Eulemur

flavifrons)Native to Madagascar, the blue-eyed black lemur is one of the 25 most endangered primate species in the world due to habitat loss and illegal trafficking in fur, meat and the pet trade. Aside from the brown spider monkey, this species of lemur is the only other non-human primate that has blue eyes. A rare sight in the wild indeed. A sexually dimorphic species, blue-eyed black lemurs' sexes can be easily determined by their fur color. Males are black. Females and newborns are a reddish-tan color. If the infant is male, the fur will start to grow black between four to eight weeks of age. While usually one offspring is born at a time, twins do occur. The baby lemur will cling to its mother for the first three weeks of its life. After that, they will start to explore on their own, but still stay close to the mother for food and protection. It will start to eat solid foods at four to six weeks but will not fully wean until five to six months. Mainly frugivores (fruit eaters), they will also eat leaves, berries, seeds and occasionally insects. Originally believed to be a subspecies of the black lemur ( Eulemur macaco ), the blue-eyed black lemur was not classified as its own species until 2008.

South Florida is home to many unique ecosystems and species. Development changes the landscape to be suitable for human activities and typically displaces native species. Animals are able to move and flee these activities, but native plants are not able to relocate in the same way. Conservation concerns also include poaching or the illegal collection of threatened and endangered plant species. One of the most unique ecosystems in Florida is the Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park. This 85,000-acre preserve is home to an amazing diversity of species and is home to 44 species of native orchids. Orchids are highly sought after by poachers, and this puts them at the top of the priority list for conservation.

Cyrtopodium Punctatum, commonly known as the cigar orchid, bee swarm orchid, or cow horn orchid is a remarkable species that puts on a huge show of beautiful flowers and has been sought after by collectors for decades. Clear cut logging of the Fakahatchee in the 1940s put significant pressure on the amount of habitat available for cigar orchids, but poaching of cigar orchids made the problem even worse. Poachers would harvest the flowering plants and sell them to collectors where these plants usually ended up dying. By 2006 it was believed there were less than 25 individual plants in the entire 85,000-acre swamp forest.

To restore the population to sustainable numbers, an ambitious restoration experiment was conceived. State Park managers and Atlanta Botanical Garden worked to cross pollinate cigar orchid plants in the wild and legally harvest seed. This seed was then grown in Atlanta and plantlets were produced for restoration. In 2015, the Zoo joined the fieldwork when seedlings were transported back to South Florida for outplanting. Over the years, around 2,000 plants were planted back in their habitat and monitored for survival. Many of the plants have thrived in their new home and some have even produced flowers. In the future we hope to observe naturally occurring seedlings. Every membership contributes to conservation projects locally and abroad!

“Conservation concerns also include poaching or the illegal collection of threatened and endangered plant species.”

To see additional videos please visit our YouTube Channel

To understand the relationship animals have with our environment and ecosystem, we should revisit our 9th grade science class and think back to the carbon cycle, which is the chemical backbone for life on our planet. The carbon cycle is a process that moves carbon between plants, animals, microbes and the atmosphere. In a process called photosynthesis, plants use the sun, water and carbon dioxide to produce oxygen and energy. Animals then consume plants, oxygen and other animals, and release nutrients back into the soil and atmosphere as part of the cycle. While this seems like a very simplified answer to why animals are important to the ecosystem and environment, it is easy to forget that this balance can be easily disrupted and cause significant ramifications.

Everything, even something we find as noxious as a mosquito, has its place in the life cycle. Mosquitoes provide food for bats and spiders who help control agricultural pests, fertilize plants and act as a food source for other higher-level predators. Though the connection to different ecosystems and environments is sometimes quite complicated depending on the animal being considered, all have an impact on the system and disrupting even the smallest part of it can cause damage.

Though there are many ways in which humans impact this carbon cycle, activities in the illegal wildlife trade have significant repercussions. In Guam, hunting and poaching of bat species is illegal, but it is an integral part of local customs and is an ongoing issue. The bats are heavily reduced in numbers and the seed dispersal needed for reforestation is heavily impacted, affecting the ability of the

island’s native environment to naturally repair itself. Wildlife trafficking also occurs, which removes other species from outlying islands, decimating populations in habitats that rely solely on those species for reforestation. It becomes a vicious circle when an activity such as trade, particularly illegal trade, poses far-reaching implications.

Imagine the repercussions of bats being taken out of the system because the mosquito and other agricultural pests have been eliminated. An immediate impact would occur on bat pollinated plants like cacao (cocoa), bananas, agave (tequila, sweetener), cashews and balsa. The removal of this one species will have an impact on everyone’s day-to-day life.

There have been recent studies that are beginning to quantify the importance of animals in the management and regulation of the carbon cycle. Findings show that some populations help contribute to offsetting the human impacts on the climate and the environment. Acknowledging and respecting the role animals play in sustaining the environment is key.

On a simpler note, animals provide us with food, provide seed dispersal and pollination for plants we need and use, as well as give back nutrients to the earth and atmosphere that benefits every living thing on earth. We often forget our own taxonomy, which is:

As fellow animals, we are intrinsic to the environment, and we must not forget that other animals are too.

Born April 7, 2023

Parents

Babette and Harry

Habitat

Dense rain forest, arid scrubland, reed thickets, and shoreline forests with reliable water sources.

Range

Southwestern United States and Mexico south through Central and South America as far as Patagonia

Conservation Status

IUCN Redlist Near Threatened Population Trend Decreasing

A departure this month from photo tips and technical how-to-do. Let’s talk about wild animals. The term “wild” has many meanings. Untamed, primal and natural are all words that come to mind when thinking of the term. As a photographer, I love exploring places that bring me in contact with all different facets of the environment, but especially the wildness. One of the reasons I love a zoo or aquarium so much is because it gets me closer to a wild part of our world that I likely won’t ever get to see any other way. It allows my imagination to run free. It takes me to a place in my mind that is comforting and enjoyable.

From mammals, birds, reptiles and even insects, these creatures are fascinating. They are at the Zoo, but they are still wild. I love this, and it’s why I strive to make images that eliminate any signs of human influence. I try to imagine how they would look in their native, natural environment. It’s my tribute to these magnificent creatures with whom we share our world. Nothing gives me more pleasure than to totally immerse myself in our natural world and to try to capture its beauty through photography.

Although, one thing I wrestle a bit with is this: what if lovely images of wild animals helps contribute to inspiring people to want one of their own? All too often people fall in love with a wild animal and end up acquiring one, usually from the illegal pet trade market. This is a tragedy on two fronts. First and foremost, wild animals simply do not make good pets. They get too big or too wild and their owners end up getting rid of them, usually by releasing them or selling them off. Secondly, it supports trafficking in wild animals, removing them from their natural habitats, weakening biodiversity and introducing the chance of diseases in their non-native environment. However, through awareness and education, photos that I or other nature photographers take can be a great learning opportunity. It’s okay to love a beautiful photo of a jaguar, komodo dragon, pittviper or any other wild species, while respecting and protecting wildlife and wild places at the same time.

I’ll get back to technical tips and advice next time. Until then, here are some of my favorite images, hopefully showing the amazing wild animals we are blessed to have at the Zoo.

Friday nights through August 11

jacksonvillezoo.org/illumiNights