1. Foreword

Looking back on the BEESPOKE project

Professor John Holland, Project Coordinator

The project has been a pleasure to coordinate, and I am so pleased that we have managed to deliver such a wide variety of new information and practical recommendations that can help with the conservation of pollinators in agricultural areas.

Such international projects are also highly valuable for the participants as we learn much from outside our normal spheres of influence and can use this to develop our own skills. For myself, I have been particularly intrigued by the results of the surveys which provided new insights into land managers attitudes to pollinators. The majority were unconcerned about levels of crop pollination, and this is understandable given that the high proportion of respondents that were arable farmers growing crops such as oilseed rape which is primarily wind pollinated. However, the fruit growers were also not so concerned and this may be because they use honeybees, there are still sufficient wild pollinators for their needs or because they are not monitoring levels of pollination or pollinators and so are unaware of any declines. The project has provided the tools to help monitor pollinators and pollination whilst the new predictive maps will also help identify potentially deficient areas.

However, we know that pollinators are declining as are many other types of insects and it would be prudent to implement measures now to support pollinators thereby ensuring we have sufficiently robust and diverse suite of pollinators to survive climatic fluctuations, but also as important, to support pollination of wild plants to which wild pollinators are intrinsically linked, as is the functioning of agroecosystems.

It was encouraging to see that many land managers’ motivation for supporting pollinators was for conservation. Our hope is that the policy recommendations and practical advice developed by the project will be utilized and thereby help land managers establish higher quality and effective habitats for pollinators. Our experiences in the project have shown the challenges of establishing and managing new wildflower areas and that land managers need greater flexibility and effective training alongside financial support, but without too much bureaucracy, to ensure such high-quality habitats are achieved.

Indeed, the whole agricultural landscape needs to deliver a greater abundance and diversity of flowering plants and trees if pollinators are not to decline further, and this is our key message to all land managers and policy makers.

photo: Jayna Connelly

photo: Jayna Connelly

photo: Vlaamse Landmaatschappij

photo: Vlaamse Landmaatschappij

2. Key Outputs & Recommendations

2. Key Outputs & Recommendations of the Project

Professor John Holland, Project Coordinator & Michelle Fountain, NIAB East MallingAfter four years the BEESPOKE project comes to an end in June 2023. For our final conference organized as the ‘Policy Influencer Event: New solutions to help reverse Europe’s biodiversity and pollinator crisis on farmland’ (together with the Interreg NSR project PARTRIDGE) we summarized our key outputs and recommendations. This article highlights the main aspects. The following articles in the magazine will cover these outputs and recommendations in more detail.

Project overview

The North Sea Region is one of the most productive agricultural areas in the EU and across the EU the value of crop pollination was estimated at 15 billion. Support for creating pollinator rich habitats has been available for many years in most member states to help reverse declines in pollinators. However, uptake is often low. In addition, levels of crop pollination are rarely considered in crop management yet can have considerable impact on crop yields and quality.

The project was established to develop new expertise and tools for land managers and policy makers so that they can improve levels of pollinators and crop pollination, thereby creating more sustainable and resilient agroecosystems.

This included developing new wildflower seed mixes, training materials to improve management pollinators and measuring crop pollination, and predictive land management software. Many demonstration sites were also established to help us engage more directly with land managers and obtain feedback on our new tools. We also wanted to understand why land managers were not encouraging pollinators and whether current agri-environment schemes could be improved to better support pollinators. Surveys and economic investigations were therefore conducted. The BEESPOKE project was

represented by 7 North Sea Region (NSR) countries with 18 partners including researchers, seed companies, and advisors.

Key outputs Seed mixes developed

Standard seed mixes contain a limited range of plant species. The project developed bespoke seed mixes to support pollinators of crops

reliant upon bees for pollination (e.g. apples, and strawberries). We measured the attractiveness of our wildflower mixes to pollinators and other beneficial insects, and quantified the success of the seed mixes on farms.

Recommendations for seed mixes in general (page 16) and grassland mixes (page 18)

New wildflower areas

New wildflower areas were established on over 300 sites and the project partners reached out to over 350,000 people. This shows the level of interest in pollinators by all actors in the agricultural industry.

Recommendations for establishment, management and AES for wildflower areas (page 14)

Farmers attitudes

Very little information is available regarding farmer attitudes to pollinators and crop pollination. We carried out surveys of land managers to determine attitudes and experiences of supporting pollinators, crop pollination and agri-environment schemes across the NSR countries.

Research insights into costs & benefit from adaption of seed mixes (page 34) and adoption of pollinator management (page 36)

Agri-environment schemes

SWOT analyses were conducted for each countries agri-environment schemes (AES) measures to support pollinators. These were then analyzed to identify how their schemes could be improved. These findings and those from the project were used to develop a series of future policy recommendations.

Policy recommendations (page 14)

Training, guidance & online resources

In-field training events were conducted in each NSR country. Such approaches are the best way to engage land managers but do require considerable financial resources. We produced 10 guides on how to support pollinators and measure crop pollination and 30 videos covering pollinator identification, measuring pollination and wildflower habitat management. The project partners have widely promoted project findings and pollinator conservation through a wide range of media. We have created a legacy of free online resources available to farmers, politicians, advisors and the public.

Guides & tutorials (page 48-52) and research insights (page 27)

Predictive tools

Two predictive tools were also developed. The first quantified the levels of crop pollination by region or farm, and the second estimates the added value of flower areas for pollinators.

Predictive tools (page 41)

Key recommendations

Seed mixes

Wildflower seed mixes should be tailored for the locality (soil type), target insect groups and achievable maintenance regimes of mowing and management if to be successful. Annual and perennial flower seed mixes should be sown.

Native seeds - location

We recommend the use of locally grown seed, where possible, as local seed will be adapted to the local environment. However, no single seed mix fits all situations, targets or even budget and must be adapted to the needs of the farmer, crop and environment.

AES payments - economics

AES payments vary widely across the NSR countries. The costs of establishing and maintaining small areas of AES habitats is much higher than for crops and targeted wildflower mixes are also more expensive. As a result of this AES payments need to reflect these higher costs. AES should also include options to support flowering plants in all non-crop habitats such as woodland, scrubland, grassland and field margins.

Flexibility

AES rules need to be more flexible to give farmers ownership of what they plant and where. This will ultimately lead to an interest in implementing floral areas and deliver better results for the benefit of pollinators and the environment. The establishment of new wildflower areas can be difficult, hence AES should be flexible to accommodate variable weather, farm equipment and skills of the land manager.

Food for pollinators

Pollinators respond positively to the total abundance of floral resources and diversity of flowering species. The amount land taken out of production can be reduced if higher quality areas are created but this depends on land managers having the support, motivation and skills to create such habitats.

Multiple Benefits

Ideally, floral resources should span from March to October via a range of flower-rich habitats which can include grasslands, woodlands and hedgerows. Weeds can also provide valuable resources therefore herbicides should be used sparingly and scruffy areas left alone. By supporting insect fauna year-round, multiple benefits will be realized; not only pollination, but pest control services, biodiversity gains and added social value.

Advice

We believe that land managers need access to free training on benefits for crop pollination and management of pollinators and their habitats. Those providing the advice need knowledge of not just biodiversity and management but also agronomy and constraints that farmers are under.

The BEESPOKE project goes a long way toward these key recommendations and helps farmers, policy makers and advisors reach a more sustainable farming delivery system with greater benefits for wildlife, the environment and people. Overall, our key message is that we need to increase plant diversity and flower abundance on farmland if we are to create more resilient agro-ecosystems.

Final conference of BEESPOKE & PARTRIDGE: Policy Influencer

Event in Brussels, May 2023

How can agri-environmental schemes be improved to increase farmland biodiversity and crop pollination?

Suggestions and solutions for these challenges were presented and discussed in Brussels during the final conferences of the BEESPOKE and PARTRIDGE projects at the European Committee of the Regions in Brussels.

Watch both projects presented their key outputs and recommendations and follow the inspiring stakeholder panel discussions where a European Commission member, scientists and a farmer expressed their point of view.

photo: NIAB

photo: NIAB

3. Recommendations

3.1 Policy Recommendations

Flemish Land Agency (VLM - Vlaamse Landmaatschappij)Agri-Environment Schemes (AES) are important for the conservation of farmed environments of high nature value, for the protection of agroecosystems and arable wildlife. In most member states (MS), farmers can have a sown flower areas as part of their AES. However, uptake has been low despite these being one of the most valuable habitats for a range of wildlife. Ways to increase uptake need to be explored.

Sustainable protection of wild bees in agricultural areas assumes a wide range of measures of which maintaining natural flower-rich vegetation, grasslands, flowering hedges and woodland, ‘messy corners’, regulating pesticide, etc., form the basis. These can be reinforced with additional supporting measures such as establishment of flower fields/edges on farms.

Establishment of flower areas within fields is a measure promoted as AES in several MS. The BEESPOKE policy recommendations are made specifically for flower areas and can be considered when developing AES’s or Eco Schemes.

Our partners from the Flemish Land Agency developed these recommendations on the following main points. You can find the detailed recommendations here

1. Seed mixture use of locally adapted species

2. Sowing and managing flower strips more flexibility

3. Quality control of seed mixes encourage locally produced seeds

4. Remuneration financial encouragement

5. Legislation voluntary measures

6. Advisory services importance of proper advice

7. Engagement actions improve communication and participation

3.2 Principles for Selecting Seed Mixes for Wildflower Strips

Lene Sigsgaard (University of Copenhagen and Norwegian University of Life Sciences), Thomas van Loo (Inagro), Regine Albers (Carl von Ossietzky University Oldenburg), John Holland (Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust)

Pollinators and pollination are under pressure, as pollinators lack food and habitat in the landscape. In many places the natural flowering vegetation is not enough to support pollinators. The EU considers that there is a pollination deficit.

By sowing wildflower strips pollen and nectar can be provided to insects. Perennial flower strips and flowering hedgerows also provide overwintering sites and year-round habitat so pollinator communities can build up. Hereby wildflower strips can be used to increase pollinators and insect biodiversity and the stronger pollinator community ensures that crops get a more reliable pollination service.

In order to establish a wildflower strip, we recommend considering the following principles for the selection of the right seed mix:

Native seeds

• Choose plants that are compatible with region, climate and soil type.

• Include native plants in the mix. Insects are evolutionarily adapted to the native plants of the region, for this reason native plants will have value beyond providing pollen and nectar food for the natural enemies and will also contribute to biodiversity and wildlife.

Attract the right audience

• Choose flowers with known value to beneficial insects:

- Leguminous plants (Fabaceae), such as clovers and vetches, are great for bees especially for honeybees and bumblebees, which can use their tongues to get to the nectar.

- Solitary bees and natural enemies of pests (predators, parasitoids)

need open flowers, which have nectar accessible. Flower families include for example Asteraceae, Apiaceae, Rosaceae, Malvaceae or Geranium.

Perennials!

• Choose perennial mixes. A flower strip that remains in place for several years will build up a population of beneficials year by year and thus increase in value with time.

• Create a flower mix which provides food for different beneficial insects, which will be flowering from early spring to late autumn to support pollinators and natural enemies all season.

• Annual flower strips will provide food during spring-summer only. Annual strips can be relevant in annual crops and should then be connected with permanent habitats such as hedgerows providing nesting and overwintering sites.

• Including grasses in the mix can make a flower strip more robust to traffic. However, in North-Western European climate grasses can become too dominant. Select non-competitive and tussock forming grasses and include less than 15% by weight and certainly no more than 40%.

Sowing, cutting, mowing

• Perennial strips do not flower the year they are sown but will flower the following spring when sown in autumn. Autumn sowing works best in North-Western Europe as spring may be too dry.

• If a perennial mix is sown in spring up to 20% annuals can be added to have some flowers the first year after sowing. Possible annuals to use are a mix of cornflower, poppy and corncockles.

• Flower strips should be cut 1-3 times per year. Find more details about the management of flower strips in our guides here.

• Phased mowing of Lucerne. Lucerne is a flowering crop and by phased mowing flowers are secured pollinators. Such an approach can also be used for legume only seed mixes.

• More flowering crops in the landscape. Examples: field beans, read beans, chickpeas, cup plant

Care for your weeds

• Weeds are also a good source of floral food for solitary bees, hoverflies and natural enemies of pests. Some species also flower early (Dandelions) or late in the year (Dead nettles) and so can extend the time over which floral resources are available. Natural regeneration or cultivating the soil in early spring can encourage annual weeds whilst leaving scruffy areas allows both annuals and perennial weeds to survive.

Not all bloom at once

Lene Sigsgaard from the University of Copenhagen investigated perennial flower strips on demo sites in Denmark. While “these native, highly diverse, perennial flower strips do look more like green ‘vegetation strips’ as not all species bloom at once, interestingly we still see more pollinators in apple trees near flower strips than in apple trees near ‘grass strips’ even when grass strips have more flower heads per m2 [of dandelions and daisies] than flower strips.”

Examples of seed mix compositions

Example 1

Highly diverse, native perennial flower mix to support pollinators and natural enemies. For interrow flower strips and marginal strips in various crops including apples and strawberries (University of Copenhagen and HortiAdvice, Denmark)

Grasses Herbs Taller herbs1

Poa trivialis Hypochaeris radicata Vicia sepium Hypericum perforatum

Lolium perenne Prunella vulgaris Medicago lupulina Knautia arvensis

Festuca guestfalica Centaurea jacea Leucanthemum vulgare Pastinaca sativa

Poa pratensis Lotus corniculatus Galium mollugo Origanum vulgare

Cynosurus cristatus Achillea millefolium Leontodon autumnalis

Poa nemoralis Bellis perennis Carum carvi

Festuca rubra rubra Mit. Sanguisorba minor Campanula rotundifolia

Anthoxanthum odoratum Cichorium intybus Geranium pyrenaicum

Silene dioica Trifolium pratense

Myosotis scorpioides Leontodon hispidus

Primula elatior Silene flos-cuculi

Crepis capillaris Daucus carota Lathyrus pratensis

Example 2

Highly diverse mix in grassland field margins (Agrarisch Collectie Waadrâne, the Netherlands)

Example 3

photo: Inagro - Bombus pascuorum on cup-plant

photo: Inagro - Bombus pascuorum on cup-plant

3.3 Herb-rich Grasslands for Cows and Pollinators

Regine Albers (Carl von Ossietzky University Oldenburg)Historically, grasslands that were shaped by agricultural practice have been some of the most important habitats for pollinators in Central Europe. A great number of plants flowered in them and there were plenty of nesting opportunities. This changed with the intensification of grasslands. Grasses were bred for more biomass, meadows became larger in size, soil were , and fertilizers increased the amount of fodder produced. The productivity increased food production greatly but changed the landscape to a grass-dominated environment with harsh conditions that only few plant species can withstand. Flower strips are not an option in grasslands, but bringing back some of the plant species to the meadows can be of great value for the farmer as well as the insects.

Biodiversity effects can assist in getting the most value out of a meadow. These consist of two mechanisms: the selection effect, meaning that in a mix of species there is always one that can be the most productive under the current conditions, and the complementarity effect. This describes the ability of species to harvest different resources, for example, by having different rooting depths. Both effects lead to the coexistence of species over time.

In the Northwest of Germany, dairy production is of major importance. This is where the University Oldenburg and the Grassland Center started a study on seed mixtures for intensively used grasslands with four to five cuts per year. Five mixtures of increasing diversity were created to and tested on three different soil types. They were surveyed for vegetation development, floral resources, pollinators, and fodder quality. We found that a mix of grasses, legumes, and herbs produced great fodder quality and quantity, frequently provided many flowers, and was popular with insect pollinators.

Grassland seed mix composition

1. Grasses

Grasses are of course the most important part of a grassland seed mix. A highly productive species like perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) is a great base. Grasses are most productive in spring when great amounts of fresh roughage are needed for the cattle. Depending on the local conditions and the soil, it can be valuable to include more grass species. Further, mixing several species decreases the spread of plant diseases. Climate change increases the probability of droughts, so including a drought resilient species like cocksfoot (Dactylis glomerata) can reduce the risk of losses that are likely to happen with just L. perenne

2. Legumes

The second component to a good grassland mix are legumes. The most commonly used species are white and red clover (Trifolium repens and T. pratense). Both have a strong summer growth that complements the spring growth of the grasses.

The greatest value of legumes is through, the symbiosis with nitrogen fixing bacteria meaning that they produce their own N fertilizer that they also share with surrounding plants. In our study, the farmers could reduce the use of inorganic fertilizers, lowering production costs.

The high N availability is mirrored in the high protein content of legume fodder. Cows like the taste and even increase their fodder intake when fed legumes. Clovers also have deeper roots that reduce vulnerability to droughts. There are more legumes that can be used, for example birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus) which is very popular with bumblebees and thrives on slightly alkaline soils.

3. Herbs

The last part of the mix is herbs which is the most challenging one as most herbs cannot withstand the frequent cutting of an intensive management. We used ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolata), a deeprooting species that is resilient to drought, produces a lot of biomass in summer and adds easily accessible flowers that attracted many hoverflies in our study. It further adds healthy plant metabolites to the cow’s diet. Another herb with similar properties that is increasingly being used is chicory (Cichorium intybus). This species is of high nutritional value and adds another kind of flowers for pollinators.

Management recommendations

Our five project farmers who managed the 25 ha of BEESPOKE grassland are all convinced that clover is part of the solution and established it on more fields. Some even worked with clovers for many years. They are very engaged in exploring new farming methods and sharing their experiences with others. The knowledge exchange between farmers and project partners was of great worth for both sides.

The fields do not require special management. The mixture is created for cutting but can be adapted for pastures and for oversowing established meadows. The local soil conditions must be taken into account in the selection of plant species. It is important though to control weeds thoroughly as herbicides are not an option after establishment. Furthermore, insect-friendly mowing techniques like mowing from one side to the other or from the middle to the outsides, increase the potential benefits for pollinators. If possible, mowing should take place after the legumes and herbs bloomed.

A diverse environment is essential for the lifecycle of pollinators. The importance of extensively managed or semi-natural habitats like hedges, buffer strips and ditches cannot be overstated. Diverse grasslands can be a valuable addition the landscape mix.

Herb-rich grasslands are a great alternative for grass monocultures, but they do not stand by themselves.

Do you want to learn more about grasslands?

We recorded our webinar on herb-rich grasslands from June 2023. You can watch it here.

Learn about the value of reestablishing diverse herb-rich grasslands, their benefits for pollinators, biodiversity and farmers as well as and the management of those meadows. Our project partners from Germany and the Netherlands share their expertise and learnings from 4 years of the BEESPOKE project.

4. Research Insights

4.1 Cup-plant: A Perennial Fodder Crop with Potential

A prospection of the properties of cupplant (Silphium perfoliatum) as a fodder crop

Thomas van Loo, Inagro

Thomas van Loo, Inagro

A changing climate with more extreme weather conditions, a decrease in biodiversity, fewer permitted pesticides, soil erosion... These are current topics where the cup-plant can possibly offer help as an alternative crop. To estimate whether this crop has potential as a fodder crop, Inagro studied the pollinators on cup-plant flowers and analysed five different plots. Inagro carried out this research in the framework of BEESPOKE, where we look for ways to support pollinators in the agricultural landscape.

Cup-plant, a plant with many assets

The cup-plant is a perennial crop that can remain productive for more than 20 years without having to till the soil. Moreover, it is a very tall plant, which can reach more than 3 m in height and accordingly produces a lot of biomass. Its ability to withstand drought thanks to its roots that grow more than 2 m deep, combined with its ability to withstand flooding for several days in winter, make it an attractive crop in today’s weather patterns. Moreover, the deep roots make it possible to recover nutrients that might otherwise have leaked away too deep into the soil.

In addition, the cup-plant has interesting flowering properties. The plants produce many flowers, which are very attractive to many beneficial insects such as hoverflies (natural enemies) and bees (pollinators). The plants flower quite late in the summer, at a time when few other plants produce nectar. The cup-plant thereby offers the needed food resources for many insects at this time of the season.

Promising fodder

Currently the main interest in the crop is focussing on its usage as an energy-crop, for methanization. A study shows that plants harvested at the end of the flowering period also show promising nutritional properties

• The plants contain a lot of sugar, so the product is tasty and possible for silage.

• You do have to supplement the crop with other products that are less structured.

• The protein content seems to vary widely but is probably related to soil fertility and the degree of dehydration of the plants.

• Some trace elements and minerals are clearly increased in sunflower crown: For example, there is 10 times more calcium than in corn.

Results from plants that already are about 10 years old are not performing less than the younger plants. Attractiveness for pollinators was investigated on 1 location, but only on a handful of plants due to unforeseen circumstances.

Would you like to know more about the study of cup-plant as a fodder

photo: Inagro - Bombus pascuorum on cup-plant

photo: Inagro - Bombus pascuorum on cup-plant

4.2 Autogamy and flower visitation by pollinators in different varieties of flowering crops

Thomas van Loo, InagroIn this study, Inagro investigated to what extent a series of crops are attractive for pollinators and thus play a role in supporting these insects in the landscape. The study took place on a small-scale trial field at the premisses of Inagro in Beitem, Belgium in 2022. Additionally, a trial was set up to investigate to what extend several varieties of these crops benefit from insect pollination. The crops in this study were lupins, summer field beans, gold-of-pleasure, soybeans, red Phaseolus beans and chickpeas.

Pollinators and crops: bees and flowers need each other

Pollinators need plants to provide them with food to survive and to reproduce. Many plant species in their turn need pollinators for their own reproduction. Some flowering plants produce flowers but are also able to produce seeds without pollinators. Although being able to produce seeds without pollinators, yield in these plants often still is higher if they are supplementary pollinated by insects.

Flower visitors: (un)faithful?

Although Inagro counted quite some pollinators in the earliest flowering crops (summer field beans, gold-of-pleasure and lupins), the pollinator activity dropped dramatically from mid-July onwards. Furthermore, many flower visits were registered as “nectar robbing”, which is a behaviour where pollinators surpass the pollination mechanism of the flowers by gnawing a hole at the base of the flower. Therefore, there was little activity that resulted in effective pollination in this trial study.

• Only Buff-tailed bumblebees (B. terrestris) has been observed making these holes, both in this study as well as in previous studies.

• Honeybees themselves cannot make the holes but they to use the premade holes as well.

• From other pollinator species it is known that they only access the flowers via the regular way: these species have longer tongues with which they can reach the nectar glands at the base of the flower through a regular flower visit.

In previous, more large-scale studies, we found that both B. terrestris and honeybees show a mixed behaviour of robbing nectar combined with regular flower visits, so they both do act as true pollinators as well. When performing a regular visit, they probably collect pollen to feed to their larvae, instead of nectar.

Buff-tailed bumblebees and honeybees: dominant, but not in all crops

• In summer field beans, the highest densities of pollinators were observed (B. terrestris and honeybees), and here almost exclusively

nectar robbing was observed as a type of flower visit.

• In gold-of-pleasure, many hoverflies were observed in addition to honeybees.

• In lupins, only regular flower visitation was observed. Possibly the flower tube of lupins is shorter, or the nectar glands are higher in the flowers than in field beans.

• Flower visitation in red beans was dominated by B. terrestris, which exclusively robbed nectar. The honeybees showed mainly regulatory behaviour.

• In chickpeas, almost all flower-visiting behaviour was regulatory (no individuals of B. terrestris were observed in the chickpea fields during monitoring).

• Very few individuals were observed visiting soybean (B. terrestris and honeybees), but then this crop only started flowering at a time when pollinator activity was already declining.

Of all the observations in this study, B. terrestris and honeybees were the dominant species.

Conclusion

Since true pollinator activity was low in almost all of the crops, the present study cannot draw conclusions on the effect of insectpollination in terms of nutritional value and yield parameters for most of the crops.

It would be valuable to revisit this kind of study, under a higher true pollination pressure (more bees, and/or a higher diversity of bees including long tongued species). However, what the present study might point to regarding crop pollination is on the one hand the need to support pollinators throughout the whole year to avoid drops in pollinator activity, and on the other hand the need to support bumblebee species which have longer tongues in the agricultural landscape, since these are the species which generally only exhibit regular flower visitation behaviour. These species however are the ones which have declined the most in the recent past. It is unclear to what extent the crops themselves also provide valuable pollen in terms of nutritional value for pollinators: this is needed to feed their larvae throughout the season in their colonies. In any case, flowering crops alone are probably not sufficient to meet all pollinator needs throughout the year. In addition, bumblebees also need nesting facilities in the near vicinity.

4.3 Wider Biodiversity Benefits of Wildflower Areas

Exploring the benefits of encouraging pollinators for wild plants on farmland

Lucy Capstick, Game & Wildlife Conservation TrustAs part of work carried through the extension to the BEESPOKE project, the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust aimed to demonstrate some of the wider biodiversity benefits of wildflower areas.

The decline in pollinators on farmland is threatening populations of wild plants which depend on pollinators for reproduction. Management which encourages pollinator populations on farmland to support crop pollination could therefore also benefit these wild plants.

Aims of the study

We aimed to explore how the amount of wildflower habitat and different farming practices affected the pollination of wild plants, specifically hawthorn. We looked at hawthorn pollination because it is common on farmland in the UK and previous work (Jacobs et al., 2009) has shown that it is dependent on insect pollination for reproduction and therefore berry production (an important winter food source for farmland wildlife) but was also under-pollinated.

We compared hawthorn pollination in hedges on farms employing more regenerative practices (16) and more conventional practices (15) and with varying amounts of wildflower habitat. Regenerative agriculture practices aim to protect soil health and includes reducing tillage, increasing use of cover crops and using diverse crop rotations. These practices have some benefits for wildlife, however the impacts on pollinators are less well understood.

Survey setup

In the summer of 2022, we measured hawthorn pollination of 31 hedges across two regions of the UK, Southern and Eastern (photo 1).

We visited the hedges when the hawthorn was in flower (in May) and marked 20 clusters of flowers along a 60 m transect, counting the number of flowers in each cluster. We went back to the hedges in July and again in September to count the number of flowers in each cluster that produced immature and mature fruits respectively. The greater the proportion of flowers that produced fruits (fruit set) the higher the pollination levels.

On the May and July visits we also measured the number of pollinators present on each site; we walked along the 60 m transect and counted all the bumblebees, solitary bees, hoverflies, and butterflies seen within 2m (photo 2). After this survey we also set pan traps (small brightly coloured bowls filled with water) at either end of the transect for 48 hours. This meant we could get an insight into the pollinators present in the habitat over a longer period.

Finally, we assessed the availability of floral resources on and adjacent to the hedge at six points along the transect (every 10 m). We counted and identified the flowerheads in a 1 m x 2 m vertical quadrat on the side of the hedgerow and in a 1 m x 1 m horizontal quadrat placed on the adjacent hedge bank (photo 3).

Study results

Across the 31 sites we observed many species of pollinators on our hedge transect in May and July including 151 bumblebees, 423 butterflies and 54 solitary bees. Notable solitary bees seen included Andrena tibialis (Grey-gastered Mining Bee) which is nationally rare and Andrena haemorrhoa (Early mining bee) which is known to forage on hawthorn.

We aimed to relate the availability of floral resources to the pollinators present and consequently to the pollination of hawthorn. More nature friendly farming methods could increase the availability of floral resources and or pollinator numbers and diversity.

• We did find that fruit set of hawthorn was higher on regenerative farms in both the Southern and Eastern regions, but this did not clearly link to the number of pollinators present.

• The number of pollinators seen adjacent to the hedge varied depending on region and by the functional group of pollinators. For example, more bumblebees were seen on more regenerative farms and more butterflies were observed in the Southern region.

• Conversely in the pan trap samples more pollinators were counted on farms using more conventional practices and in the Eastern region.

We explored whether these patterns could be linked to the floral resources available. We did see a trend towards higher numbers of flower heads and umbellifers adjacent to the hedge on farms with more regenerative practices and for both regions. This could explain the higher number of bumblebees seen on these sites. Our next steps are to explore specific interactions between pollinators and plant species and to relate this to the specific farming practices used and the wildflower area in the landscape.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the landowners and managers who gave us access to their farms for this study. This work was partially funded by the BEESPOKE and partial funding also came as part of the H3 project. H3 is part of the ‘Transforming UK food systems’ research programme funded via UKRI’s Strategic Priorities Fund (BB/ V004719/1).

4.4 Farm Level Costs and Benefits from Adoption of BEESPOKE Pollinator Friendly Seed Mixes

Iain Fraser, University of Kent, June 2023Introduction

There is a significant body of research demonstrating that insects in general and pollinators in particular are in decline. As a result, there are a myriad of government policies (e.g. Agri-environmental policy (AEP)) and associated initiatives that seek to reverse the decline. However,

• Do they have the appropriate land management knowledge and skills to support pollinator friendly activities?

• Do they have the necessary land and other resources, including time, available to devote to this type of activity?

• Do the financial implications of adoption make sense?

To examine these questions, we have examined two AEP options available in England as part of the Countryside Stewardship Scheme (CSS) (AB1: Nectar flower mix; and AB8: Flower-rich margins and plots). The scenarios we examine also apply to other Interreg North Sea Region (NSR) partner countries that employ very similar policy options. Our analysis considers how changes to the cost of wildflower seed mixes might influence the economic incentives facing potential adopters. It has been implemented in Excel and it includes key land

there is still the need to train land managers in the skills needed to identify pollinators and determine the pollination levels required for optimal crop production. And even when suitable training is available there is also a need to understand the potential likelihood of adoption of farm level practices explicitly designed to support pollinators either for production or biodiversity.

The decision to adopt or not one or more of the pollinator friendly practices can be a complex choice. This is because adoption requires land managers to simultaneously consider:

use management decisions and the associated economic implications. Although our analysis is only illustrative it does enable us to see how the choice of alternative seed mixes impacts the financial incentives arising from the management of land used to support pollinators.

The Cost of Seed Mixes

The cost of seeds used to create the wildflower margins and strips varies significantly. For example, in the UK costs can range from around £100 per hectare to in-excess of £2,000 per hectare. This variation depends on the composition and source of the seed used. Similar

variations in seed costs are also reported in other NSR countries. Currently, agricultural seed suppliers advertise seed mixes that can be used when adopting the AEP options such as AB1 and AB8. However, research conducted as part of the BEESPOKE project indicates that seed mixes that include a greater proportion of perennial flowers and less grass (and less aggressive grass) not only yield an increased number of flowers but a mix of flowers that can yield pollen for a much longer period each year. In addition, the BEESPOKE seed mixes will last much longer (up to 20 years) and require far less active management to supress excessive grass growth.

But, these mixes are significantly more expensive and so the question remains: Will land use managers adopt them?

Costs, Benefits and Adoption?

In undertaking our analysis, we identified the costs and benefits associated with growing wildflower strips on arable and orchard farms. Our analysis included versions for which AEP payments are available because of adoption of AB1 or AB8 as well as the potential impact on crop production. We also included the opportunity cost of lost production, variation in costs associated with seed bed preparation, ongoing management of flower strips and if the flower strips are grown on fragmented parcels of land.

In general, the cost of seed mix is not the main issue driving the balance between costs and benefits. That said, the use of a lower cost seed mix will increase the financial attractiveness of adoption. However, many of these mixes are not as effective as those developed by the BEESPOKE project when it comes to supporting pollinators. But, the impact on crop production as a result of enhanced pollination is less clear. Employing land that is currently in production can have a significant impact on the economics of whether or not to adopt this type of land use activity. Also, as parcels of land become more fragmented the costs of land preparation and management increase significantly. The magnitude of these costs is such that the economic incentives from adoption are negative for the given levels of payments on offer for AB1 and AB8. Importantly, the level of payments on offer in other NSR countries for related activities are generally higher and this clearly has a positive impact on the likelihood of adoption. It is only when there is little or no lost income from reducing existing

crop production such as planting within orchards or replacing grassy non-productive areas between and around fields fields. In addition, in the case of orchards there can be an increase in fruit yield and quality that strengthens the economic incentive. Also, in some NSR countries, it has been found that there are also economic and biodiversity benefits when modifying seed mixes used in pasture production for livestock.

Concluding Observations

Our analysis indicates that the economic incentives facing land managers in terms of flower strip adoption to support pollinators are (in England) marginal. This result holds even before we consider the higher cost associated with employing the BEESPOKE seed mixes. But these seed mixes produce higher environmental benefits.

Very simply, if policy makers really want to increase levels of adoption and more importantly the ecological effectiveness of flower strips then payment levels, certainly in England, will need to increase.

Finally, there is evidence that adoption is also being hindered by complexity and overly prescriptive AEP design.

Clearly, the scientific evidence exists for how we can support pollinators, but this must be aligned with better policy design and implementation if efforts to reverse the decline in wild pollinators is to be successful.

5.From Fields to Landscapes

Challenges of scaling out innovative solutions

Lotta Fabricius Kristiansen & Magnus Ljung (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences)Bridging the implementation gap

New approaches to pollinator management and monitoring are necessary, along with empowering land managers to adopt such practices. The BEESPOKE project aims to address these challenges by promoting a bottom-up, land manager approach for scaling out developed solutions. Implementing these measures on a broad scale will instigate change at various levels, from fields to landscapes.

In agriculture and horticulture, traditional methods like field trials and experimental farms have facilitated the adoption of new technologies. However, the uptake of valuable measures, especially those related to ecosystem services like pollination, often suffers from a significant implementation gap. Collaborative efforts among landowners and growers are crucial in these cases, requiring engagement beyond farm gates and managing diverse perspectives through effective communication and learning methodologies.

Work package six of BEESPOKE focuses on formative evaluation and monitoring to facilitate communication and scaling out. Recognizing that no single solution is universally applicable, the development of a toolbox for advisors and others involved in the process of change becomes invaluable. Within BEESPOKE, various communicative tools have been applied and refined to bridge the implementation gap, enabling actors to operate at both field and landscape levels. Some of these tools will be discussed further.

1. Demonstration farms

On-farm demonstrations have a long tradition in Europe, originally driven by the need for efficient agriculture to sustain a growing population. These demonstrations aimed to transfer knowledge and

inspire other farmers to change their practices. Over time, various strategies for on-farm demonstrations and research have emerged, including the monitor farm model, which emphasizes a participatory and practice-oriented approach.

Participatory group-based extension models offer several advantages,

such as higher adoption rates, improved farm productivity, enhanced social well-being among farmers, and increased knowledge and skills through peer support. Such models could be viewed as a steppingstone between formal demonstration processes and farmers’ actions, by demonstrating innovations and facilitating monitoring and comparisons within a familiar context.

Within the BEESPOKE project, farm-level demonstrations have been established across the North Sea Region. These farms, with diverse production lines, serve as monitoring farms for methods and practices that promote tailored solutions for crop-specific pollinators and biodiversity enhancement. Additionally, these demo farms inspire and provide a learning environment for fellow farmers. Through demo farm events, experiences and knowledge are shared and discussed.

2. Educational material and field guides

Most farmers growing insect-pollinated crops do not measure pollinator visits to their crops, what types they are, or whether their

crop yield is being limited by inadequate pollination, and few know how to do so. Usually, they are depending on advisors to help with the assessment. By adding a possibility for farmers to a simplified valuation on their own, the way towards action is shorter. BEESPOKE has developed simple protocols for the monitoring of pollinator populations in a variety of crops, including field guides and videos to

networking, the focus would be on whether participants expanded their network. If the objective is the adoption of new measures, organizers should monitor participants’ inclination to adopt the demonstrated innovation. Understanding what the targeted group perceives and takes away, both in the short and long term, is key.

It is also valuable to keep different knowledge aspects apart. It enables us to specify the aim of an activity or measure. Ask yourself, what do we want the growers and farmers to improve?

• Know-why (motivation, raised awareness):

Participants are aware that there are specific problems or challenges and/or that new options are available and may be needed in the future.

• Know-what (the demo topic):

Participants are informed on specific novelties (new practices, materials, varieties, machinery, etc.)

• Know-how:

Participants can connect the new information to their own practices and are able to assess possibilities to implement it on their farm.

We also might want to know “what do participants do with what they brought home?”

enable non-specialists to identify insect pollinators. The protocols show the growers how to measure whether their crop yield is limited by inadequate pollination. Making the training materials available and tested, training sessions for farmers and agronomists have been held on the demonstration farms. The materials produced are now available in different languages and can be used for educational purposes in schools, farmers’ events or citizen science projects in the future.

All BEESPOKE guides & tutorials can be found on page 48 or directly on our website and Youtube channel.

3. Monitoring and evaluation

Learning from experience is vital for improving communication and ensuring sustainable uptake. Monitoring and evaluating the effects of measures and events are essential to assess their success. Formative evaluation is used for continuous improvement, and it is crucial to align the evaluation with the objectives. For example, if the objective is

Evaluating new practices resulting from specific events or guidelines is complex. It takes time for participants to make actual changes in their farming practice since it might require financial investments, additional skills and knowledge, and a readjustment in the farmer’s usual routine or even a change of mindset. Decision-making for change is influenced by multiple information sources such as publications, demos, workshops, newsletters, advisory services, and interactions with other farmers. Thus, a comprehensive and long-term strategy is crucial for scaling out innovative solutions. It is important to take the abovementioned evaluations and reflections seriously to improve future events, on-farm demonstrations, and other activities.

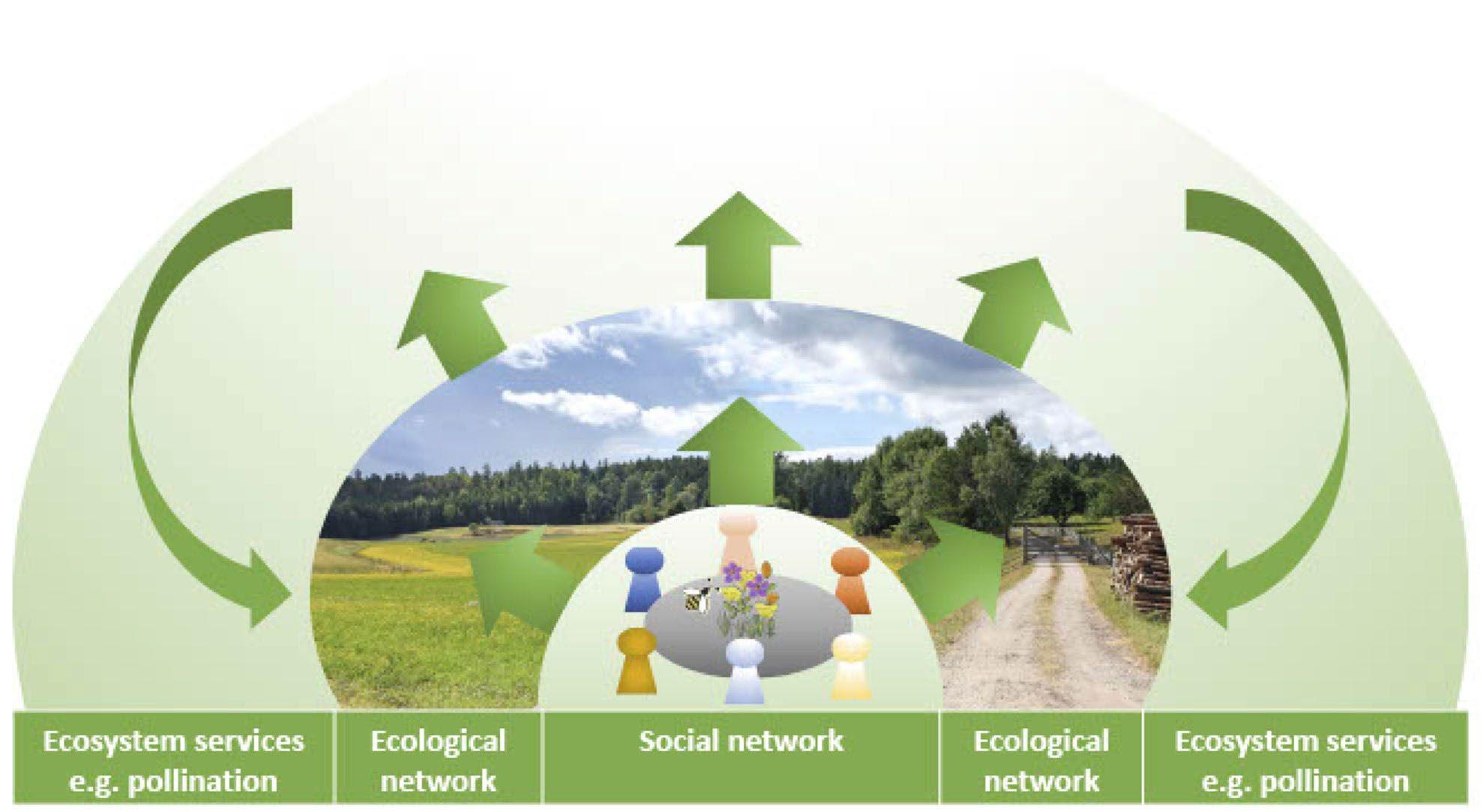

4. Connecting social networks to the ecological network

Moving from field to landscape, not only changes how we must approach the ecological network and its potential, but it also changes the social system, whom to involve and finding new ways of interacting. This is in itself an innovative process, asking for specific

competencies. Social and institutional innovations, like biodiversity conservation, are a shared responsibility and therefore easily becomes nobody’s responsibility. When fostering stakeholder collaboration, long-term considerations are essential. Designing the work with sufficient intensity, particularly during critical phases, and ensuring continuity over time due to the slow pace of land management change is crucial to maintain stakeholder engagement.

There is a strong link between farm business economics and socioecological sustainability. Conservation of certain ecological values often relies on active and traditional cultivation. A holistic development perspective for rural areas, including entrepreneurship and the local economy, is important. A strong and shared vision for rural areas, held by core actors, becomes instrumental because it is about creating supporting structures in many areas of development. Therefore responsible scaling out is not just about technical feasibility but relates also to different ideas on progress and development.

Specific strategies for scaling out will need to be tailor-made and context-specific. For this, we do not only need standards and guidelines, but individual and collective competencies as well as conducive spaces for appropriate strategy development and implementation. Only then we can move from field to landscape, from an individual grower to a learning community, as well as be able to approach the pollination challenges as holistically as possible.

5. Key recommendations for policy

It is important to create good enough external preconditions for the abovementioned measures to be scaled out. It is about creating conducive policy environments, both on regional and (inter)national levels.

Some recommendations are:

1. Support the development of new approaches to facilitate change, including adapting these to the unique characteristics of local networks and platforms for learning and co-innovation in new areas (creating space for experiments).

2. Establish systems for vertical integration of actors in the policy chain.

3. Motivate landowners to invest in pollination management by funding new measures for improved biodiversity, and make sure that such schemes are sustained over a longer period.

4. Demand systems for formative evaluation, for continuously improving preconditions and methods when scaling out social and institutional innovations, so that we consciously learn from our experiences.

photo: Jan-Willem van Kruyssen

photo: Jan-Willem van Kruyssen

6. Predictive Tools

6. Predictive Tools for Farmers

BEESPOKE helps farmers to promote pollination

Dr. Ivan Meeus & Dr. Daniel Ariza (Ghent University)BEESPOKE provides two tools which help farmers to improve land use to promote pollinators. More specific we make suggestions how pollination services can be improved for a specific crop of interest.

TOOL 1

Expected pollination service and effect of a flower strip

Tool 1 calculates the free pollination service of wild bees based on the landscape characteristics in the landscape around the crop of interest. The user is able to draw an area where landscape improvement (for example a flower strip) can be placed; the tool calculates the percentage that the pollination service increases.

TOOL 2 Selecting wildflower seeds for your crop

A second tools helps to select good flower seeds, i.e. flowers to support the bee species that will pollinate the crop of interest, a second tool will give some suggestion of flowers supporting good pollinator species per crop and country. Note the suggestions made here are for inspiration, and knowledge on how attract bee crop pollinator species, abiotic factors like soil, sun, … are not integrated.

On the BEESPOKE Tools

Website you can find: BEESPOKE helps farmers to promote pollination

Dr. Ivan Meeus & Dr. Daniel Ariza (Ghent University)• Both tools

• Step by step explanation how to use the tools

• Background information on the mechanisms & calculations behind it and the data supporting the tools

All information will be placed on: beespoketools.weebly.com

The work on this site is still ongoing, it will be updated and finally a new site will be made: UGpollinationtools.com (not yet online)

photo: Jan-Willem van Kruyssen

photo: Jan-Willem van Kruyssen

7. Guides, Tutorials, & Inspiration

7.1 Guides & Tutorials

One aim of BEESPOKE is to develop farmer friendly methods for measuring their own pollination and levels of pollinators and to improve pollination by establishing bespoke wildflower areas. To support these activities as well as general biodiversity we developed several guides and video tutorials.

Monitoring Pollination & Pollinators

By monitoring the numbers and diversity of pollinators you can gain valuable insight in the relationship between crop yield and pollination (potential pollination deficit). Thereby evidence can be provided to what extent the wildflower margins are benefitting crop pollination.

With our guides you can learn how to estimate your pollination potential, how to conduct pollinator monitoring and how to identify solitary bees and bumblebees.

Supporting Pollinators & Biodiversity

If you want to take action for pollinators and general biodiversity on your land, the following guides are developed to support you with your efforts. Learn how to establish and maintain a perennial wildflower area, how other habitats can help biodiversity or how to build a nesting possibility for solitary bees.

Upcoming guides!

Follow us on social media and our website to not miss out our upcoming guides this summer:

• Estimating Pollination in Blackcurrant

• Estimating Pollination in Cherry

• Estimating Pollination in Raspberry

• Estimating Pollination in Strawberry

• Matching Flowers to Pollinators

• BEESPOKE Seed Mix for Solitary Bee

• BEESPOKE Seed Mix for Easement strips

Video Tutorials, Interviews & More

On our Youtube channel you can find many additional as well as complementary video tutorials which can help you support your efforts for pollinators. Get inspired by interviews with farmers who share their experiences and knowledge about pollinator-friendly measures. You can also find more videos with additional knowledge about pollinator-friendly farming, webinars, the BEESPOKE project in general or our project partners.

Visit our webpage for all of our guides. If you are interested in scientific literature, you can find our publications as well as further reading here as well.

7.2 The BEESPOKE Poster

Brighten up your office wall!

Jayna Connelly, Lucy Capstick, John Holland (Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust) Illustrations by Anne-Lieke FaberYour flower strips and hedges are colourful habitats

With this poster we aim to inspire land managers to support pollinators and other wildlife with flower strips and hedges throughout the year. We provide concise habitat management recommendations per season for wildflower areas and hedges. In each season you can find the main plant species, pollinators and other wildlife for which you can provide habitat on your farmland.

The poster is available to download here: in English, Dutch or German

On our website you can find detailed instructions to establish wildflower areas and recommendations for their management. You can print the single seasons in A4 format and combine them to the whole year on your wall.

Transform your land into the colourful, lively home for pollinators and other wildlife which not only benefit the whole ecosystem but you and your crops as well!

Follow the seasons and find out what you can do for pollinators and other wildlife in your wildflower areas and hedges.

BEESPOKE

DO NOT CUT HEDGES DURING SPRING

They provide pollen for pollinators and habitat for nesting birds.

SUMMER SPRING

HEDGEROW FOLIAGE provides food for caterpillars of butterflies and moths and flowers for pollinators.

Hedges provide WINDBREAKS creating warm micro climates for wildlife.

Please visit our website for detailed management recommendations.

Sunny, low fertility, not water-logged areas are best for WILDFLOWER STRIPS.

Cut legume

FLOWER STRIPS AND GRASSLAND. Leave scruffy areas with weeds for bees.

In first year, PREPARE SEED BED for broadcasting seed in August.

Cut hedges on ROTATION of every 2-3 years. Hedges of different growth stages should be present.

AUTUMN WINTER

Hedges are IMPORTANT SHELTER for birds and other wildlife from wind and rain.

Plant new HEDGES to fill in gaps. Cut or lay overgrown hedges in rotation.

SOW SEED late August to September.

Cut plot in September. Leave 1 metre wide section uncut for OVERWINTERING INSECTS.

REMOVE GRASS CUTTINGS to maintain low nutrient soil for plant diversity.

IVY is an important late flowering plant.

Hoverflies such as DRONE FLIES will be active as early as January.

During mild winters BUFF-TAILED BUMBLEBEES will have a second brood.

If you would like to stay in touch with us and receive all updates on the BEESPOKE project, just visit our website or social media pages!

BEESPOKE

jw@vankruyssen.eu