Fall 2022VOL. 2 NO. 1 Sankalpa A Compassionate Eye – Rebecca Lerner From Breath to Prana – Pauline Schloesser Power of Inversions – Roger Cole, Ph.D. Pranayama John Schumacher Pajama Yoga – Marcia Monroe Back Leg in Standing Poses – Lois Steinberg, Ph.D. Tribute to Faeq – Carolyn Belko

IYNAUS CONVENTION 2023 with ABHIJATA IYENGAR MAY 15 — 20 TOWN & COUNTRY RESORT SAN DIEGO, CA VISIT: https://iynaus.org/convention2023 REGISTRATION OPENS SOON

THE LIGHT’S MISSION

The Light, the magazine of the Iyengar Yoga community in the U.S., is published twice a year by the Publications Committee of the Iyengar Yoga National Association of the U.S. (IYNAUS). The Light is designed to provide interesting, educational, and useful information to IYNAUS members to:

• Promote the dissemination of the art, science, and philosophy of yoga as taught by B.K.S. Iyengar, Dr. Geeta S. Iyengar, and Prashant Iyengar.

• Communicate information regarding the standards and training of certified teachers.

• Report on studies regarding the practice of Iyengar Yoga.

• Provide information on products and services related to Iyengar Yoga.

• Review and present articles and books written by the Iyengars.

• Be a platform for the expression of experience and thoughts from members of all diverse backgrounds, both students and teachers, about how the practice of yoga affects their lives.

• Present ideas to stimulate every aspect of the reader’s practice.

IYNAUS BOARD OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE CHAIRS CONTACT LIST

Fall 2022 PRESIDENT Gloria Goldberg president@iynaus.org

VICE PRESIDENT

Hector Jairo Martinez vice.president@iynaus.org

SECRETARY

Adrienne Klein secretary@iynaus.org

TREASURER

Tay Bulanda treasurer@iynaus.org

CHIEF EQUITY AND INCLUSION OFFICER

Stephanie Perry Bush yogaequityspb@iynaus.org

ARCHIVES

Kathleen Quinn, Chair archives@iynaus.org

ASSESSMENT

Nina Pileggi, Chair assessment.chair@iynaus.org

CONTINUING EDUCATION

Susan Johnson, Chair continuinged@iynaus.org

ETHICS

Janet Lilly, Chair ethics@iynaus.org

EVENTS

SulieAnna Tay (Tay), Chair events@iynaus.org

FINANCE

Tay Bulanda, Chair treasurer@iynaus.org

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Letter from the President . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Letter from the Editor 3

A Compassionate Eye, Rebecca Lerner, Dan Shuman 5

From Breath to Prana, Pauline Schloesser 11

Power of Inversions, Roger Cole, Ph.D. 17

In the Beginning Preliminary Pranayama, John Schumacher 30

Pajamas Yoga, Marcia Monroe 33

Back Leg in Standing Poses, Lois Steinberg, Ph.D 35

Tribute to Faeq, Carolyn Belko 38

Patricia Walden birthday, Randy Just 42

GOVERNANCE

Gretchen House, Chair regional.support@iynaus.org

MEMBERSHIP

Gretchen House, Chair membership@iynaus.org

PUBLICATIONS

Daniel Shuman, Chair publications@iynaus.org

PUBLIC RELATIONS/ MARKETING

Emilie Burnod, Chair socialmedia@iynaus.org

REGIONAL SUPPORT

Gretchen House, Chair regional.support@iynaus.org

SERVICE MARK & CERTIFICATION MARK

Gloria Goldberg, Attorney in Fact for B.K.S. Iyengar, Chair trademarks@iynaus.org

SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY

Nicholas Jouriles, Chair technology@iynaus.org

VOLUNTEER

Janet Lilly, Chair volunteer@iynaus.org

YOGA & EQUITY

Hector Martinez, Co-chair Megan Bowles, Co-chair yogaequity@iynaus.org

YOGA RESEARCH

Anne Clatworthy, Chair research@iynaus.org

THE LIGHT IS PRODUCED BY THE IYNAUS PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE:

Dan Shuman, Chair, Editor, The Light Jennie Williford, Editor, Samachar Don Gura, Art Director David Monteith, Copy Editor Sheryl Abrams, Advertising Susan Goulet, Advisor

WRITERS: Roger Cole Lois Steinberg Marcia Monroe Daniel Shuman Lucienne Vidah

Carolyn Belko Jim Benvenuto Pauline Schloesser John Schumacher

ADVERTISING

Text-only ads start at $50. A premium classified ad can be purchased for up to $125. Full-page, half-page, quarterpage, and classified advertising is available. All advertising is subject to IYNAUS board approval. Ads are secondary to the magazine’s content, and we reserve the right to adjust the placement of ads as needed. For more information and ad rates, please contact Sheryl Abrams at (512) 571-2115 or yogabysheryl.tx@gmail.com

The Light | Fall 2022 1

Cover photo: Caption and credit here

IYNAUS COMMITTEES

ARCHIVES

Kathleen Quinn

ASSESSMENT

Nina Pileggi

CONTINUING EDUCATION

Susan Johnson

ETHICS

Janet Lilly EVENTS

Tay Bulanda

FINANCE

Tay Bulanda

GOVERNANCE AND ELECTIONS

Gretchen House

MEMBERSHIP

Gretchen House

PUBLICATIONS

Jennie Williford

Dan Shuman

PUBLIC RELATIONS AND MARKETING

Emilie Burnod

REGIONAL SUPPORT

Gretchen House

SERVICE AND CERTIFICATION MARK

Gloria Goldberg

SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY

Nicholas Jouriles

VOLUNTEER

Janet Lilly

YOGA AND EQUITY

Hector Martinez

Megan Bowles

YOGA RESEARCH

Anne Clatworthy

PAST PRESIDENTS:

Organizational Board-1991 Mary Dunn

Dean Lerner

Karin O’Bannon

Neuberger

Salaniuk

Apt

DiCarlo

Beach

Lucey

Carpenter

For a full list of committee members and volunteers, visit our website Board and Staff

Letter FROM THE PRESIDENT

Dear Members,

With this issue of The Light, I would like to welcome and introduce you to our new Chair of Publications, Daniel Shuman. We have had an extraordinary group of volunteers heading up publications over the last few years.

First, Holly Walck Kostura revamped the entire publication format. She renamed the magazine “The Light” and separated out Samachar as a quarterly newsletter. In addition, she moved the magazine into a fully digital publication. When Holly stepped down, Jerrilyn Crowley took the reins. Jerrilyn put together several issues of The Light. I was always thrilled and fascinated with the content she curated and published.

Now Daniel Shuman! Daniel is a CIYT, and a CYT, and a faculty member of the Iyengar Institute of New York. He began practicing postural yoga in 2004 and started teaching in 2009. In July of 2019, Daniel spent a month in Pune, India, studying with the Iyengar family. From 2014 until 2020, he apprenticed with senior teacher James Murphy. Daniel is not only a CIYT but also a bass player with a BA in Jazz Studies and Performance from William Paterson University. His bass playing is well-documented on over 40 recordings in genres ranging from Americana to metal. As a musician, he has toured most of the continental United States, as well as much of Europe and the U.K.

When I first spoke to Daniel regarding this position, he immediately resonated with the creative aspect of putting the magazine together. To give you a little insight into how these magazines come together—first the chair comes up with a theme and then works with our community to develop articles and content to fit that theme. It requires hunting down photos, finding previously published articles, and coaxing members to write articles. Once the content is ready, the magazine is edited, laid out, and designed. While it is a very fun job, it is also challenging to get the magazine done on a schedule. It is a lot of work.

The next issue of The Light will come out this winter with the theme of “Recovery.” As I said, the Publications Committee is always looking for contributions from our community. If you have an interesting idea for an article, please let us know. In the meantime, enjoy the latest issue of The Light!

Randy Just President

2 The Light | Fall 2022

1992 1998

1998 2000

2000 2002 Jonathan

2002 2004 Sue

2004 2006 Marla

2006 2008 Linda

2008 2012 Chris

2012 2014 Janet Lilly 2014 2017 Michael

2017 2019 David

2019 2022 Randy Just

“

Letter

If you can adapt to and balance in a world that is always moving and unstable, you learn how to become tolerant to the permanence of change and difference.” —B.K.S. Iyengar

Welcome to the Fall 2022 issue of The Light. The theme of this issue is “Sankalpa”, which is a familiar concept to practitioners of Iyengar Yoga. During these challenging times, we are repeatedly tasked with cultivating a deeper sense of intention in the face of adversity. I am deeply grateful for the guidance I’ve received from David Monteith, our copy editor, and Don Gura, who does our layout. I would also be completely lost without President Randy Just’s tireless efforts, as well as Advertising Coordinator Sheryl Abrams, and Jerri Crowley, The Light’s previous editor in chief.

This issue finds us, still, in complex and shifting times. Our practice offers us a cornerstone of consistency and solace, in order to better adapt to life’s challenges. My new vantage point as editor of The Light allows me some fresh perspective on the work of the devoted educators, who, despite maintaining many professional obligations, have contributed fantastic and substantive pieces for this issue. Rebecca Lerner bared her soul, and showed how an early trauma led her to the path of yoga. Pauline Schloesser unpacked some of Prashant Iyengar’s profound ideas about pranayama Carolyn Belko, Lucienne Vidah, and Jim Benvenuto, all longtime students of Faeq Biria, presented a moving tribute to their teacher.

John Schumacher and Lois Steinberg provided insightful pieces on practice, pranayama and asana, respectively. And, of course, we have an absolutely massive piece from Roger Cole, who explains some of the science behind inversions, and gives us a way to understand that science experientially. Finally, Marcia Monroe shares some personal experiences about teaching and assessing online during the pandemic. I hope to share more members’ experiences on that in forthcoming issues.

I hope that you find this issue helpful for your practice and teaching. Perhaps some of you who feel inclined to write but haven’t quite gone through with it will feel compelled. Please consider submitting—we want to hear from you!

Dan Shuman

Editor in Chief, The Light

IYNAUS OFFICERS AND REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES

OFFICERS AND EXECUTIVE COUNCIL PRESIDENT Gloria Goldberg

VICE PRESIDENT Hector Jairo Martinez

TREASURER Tay Bulanda

SECRETARY Adrienne Klein

CHIEF EQUITY AND INCLUSION OFFICER Stephanie Perry Bush

SENIOR ADVISOR AND ATTORNEY FOR THE IYENGARS

Gloria Goldberg

ETHICS

Janet Lilly ASSESSMENT Nina Pileggi

REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES

IYAGNY Dan Shuman

IYALA

Amy Brown

IYAMW Jennie Williford

IYANE Rosie Richardson IYASCUS Gretchen House

IYASE Janet Lilly

STAFF

IYASW Lisa Henrich

IYAUM Susan Johnson IYACSR Sheri Cruise

IMIYA Avery Kalapa IYANW Sara Russell

IYANC Ramona Atanacio

Julia Fogelson, IYNAUS Store Manager store@iynaus.org

Nicholas Jouriles, IYNAUS Web manager webmaster@iynaus.org

The Light | Fall 2022 3

FROM THE EDITOR

4 The Light | Fall 2022

A Compassionate Eye:

Senior CIYT Rebecca Lerner

BY DAN SHUMAN

Rebecca Lerner is a name that is likely familiar to many Iyengar Yoga students, both in the United States and abroad. A four decades-long practitioner, she operates the Center for Well Being in Lemont, Pennsylvania, where she teaches alongside husband and fellow senior teacher Dean Lerner. She serves both her local community and the broader Iyengar community, including many teachers who travel to Lemont regularly for teacher intensives. (pre-COVID, that is)

I knew Rebecca from her workshops at the Iyengar Yoga Institute of New York, as well as teacher training at the Center. One of the silver linings of the pandemic Zoom era was that I was able to be a regular online student of hers. I draw great inspiration from her ability to teach a varied, multilevel group, creating a truly profound sense of unity. I am grateful that Rebecca granted me an interview, which, originally I had intended to be part of a larger issue on trauma. As with many things, the project changes as you get into the weeds with it. In the end, I feel we have a portrait of Rebecca as a student and teacher that I am sure will be inspirational to our community, and I hope you enjoy it as much as I did! I have edited it for purposes of clarity and readability. —Dan Shuman

TRAUMATIC STARTS

REBECCA: I’d had a horrific trauma on Friday, June 13, 1973. Over the years, I think I identified with my injury and my trauma a lot. As a young person—I was 16—and that was my identity. I wasn’t into yoga or natural... anything. I was living at home, in a tight knit, Roman Catholic family. I was the eldest of six. I didn’t know anything about alternatives, or how to deal with what happened to me on a different plane than the physical. Like, Ok, great, I almost lost my leg and now I’m wearing a full leg brace, and now what?

I fell through a greenhouse where I was employed. It was a dumb thing to do, but I sat on the roof. Supposedly, the wooden structure of the glazed panes was really sturdy. But it was an old roof, and I fell through a few panes— buttocks first—and was hanging, suspended there.

I could have crashed to the floor, about 8 ft. below, but I panicked. Maybe I should have just let myself go through, but I held myself up and twisted to get out and jump down from this low roof with a submerged greenhouse. I ended up severing the femoral artery and the sciatic nerve right down to the bone. I remember hearing the blood pouring out of my body, and no one was around. I was crying for help. An employee about my age heard me, and thought very quickly. She grabbed a towel by the pool, and a stick, and crafted a tourniquet up above the injury, to stop the flow of blood. I think I

They were able to stitch everything back up, but I had a permanent sciatic injury.

would have otherwise bled to death. Her intervention basically saved the leg and saved my life. Eventually, the ambulance came. It was all a blur, and I was in shock.

As a young person in high school, trying to blend in, I wanted to be just like everybody else. I was not a renegade person who liked to be different. After the accident, I wasn’t the same. They were able to stitch everything back up, but I had a permanent sciatic injury. I had to wear a full leg brace to my upper thigh crease which was heavy, metal, and bulky. I felt disfigured. And it’s a terrible thing to say. I’m not proud of what I thought, because I believed I would be stigmatized because of the disfigurement.That was my 16-year-old mentality. Now I’m different, and people are going to think there is something wrong with me mentally! Of course, you grow out of that ignorant stage. But, at the time, I had to deal with looks and stares, and being handicapped. It was an egoic blow to be unable to wear trendy shoes and clothing and instead walk about with orthopedic shoes and crutches.

At the time, we were not aware of sports medicine and special therapies. My supportive parents did the very best they could do. I was fortunate to have

The Light | Fall 2022 5

some sessions with a Czech physical therapist who did biosound therapy. It was the first time after the accident I felt that my life might go on. The treatments were meant to trigger the sciatic nerve to bring about dorsiflexion. There was a glimmer of movement in my toes and ankle, but that was it. I discovered I had only plantar flexion and inversion.

FINDING YOGA

Before my accident, I was a gymnast in high school. Afterwards, I lost my ability to engage in that sport as well as other typical fun activities. The world has made incredible advancements to accommodate being physically challenged. There’s a surfer with one leg, marathon blade runners, Special Olympics, etc. But mine was the typical world of the 70s. We were a middleclass, large family without huge resources. We didn’t have connections to specialists or alternative modalities that may have helped.

In 1976, a friend suggested I try yoga, and I purchased Richard Hittleman's 28-Day Yoga Plan. I practiced the poses in my living room, holding on to a wall for balance, as I couldn’t balance independently on my left leg. But I learned the poses, and thought, I love this yoga. And it was only on the physical ‘hatha’ yoga part of it. I wasn’t into meditation or anything spiritual yet. It was more like, Oh, this is something with my physical body that I can do, and I think it’s going to help me.

After a while I realized I needed more information. The instructions would refer to breathing, but I didn’t understand when or how to breathe. So the same friend said, “Let’s go take a class.”

That was my first experience. I took off my brace, got on a mat, and did yoga. It was very life-changing for me. I started to experience compassion for myself, and to develop much needed self-esteem. Those weren’t the words I had then, but I can articulate them now, looking back.

I realized I was getting my self-esteem back from the accident but still was thinking only superficially. That was my attitude at the time, but that’s gradually changed over the decades of being involved in yoga. In my classes, prior to the invocation, I’ll sometimes tell my students, “You get entangled in the outer self and the outer identity, the outer narrative, of who you are.”

About three years later, I discovered Iyengar Yoga, and then all hell broke loose! I thought, There is a CHANCE I might cure myself with yoga, and get my properly functioning leg back. While I had great success recovering on many levels, the sciatic nerve did not regenerate to provide strength, structure, and dorsiflexion. I did not develop back pains that can afflict many due to sciatic nerve injuries, but because of my asymmetric gait and limp, my right hip required a replacement in 2007. In any case, yoga gave me a new chance, a new try at feeling good about myself.

The poses were meaningful and strengthened my physical body. Through the physical aspect of asana I became more intrigued with the emotional/mental body where I was still suffering. I thought I was a lesser individual because I wasn’t “whole.” This was very damaging and incorrect thinking. In hindsight, I realize my injury was the best teacher to understand the stronghold the kleshas had on my life. Our physical appearance has nothing to do with mental acuity, or spiritual ability.

6 The Light | Fall 2022

“Don’t practice for cosmetic beauty, practice for cosmic beauty. Practice for inner beauty and inner light.” — B.K.S. Iyengar

I started to experience compassion for myself, and develop much needed self-esteem.

Rebecca Lerner in Marichyasana I

COMPASSIONATE EYE CONTINUED

I didn’t understand the concept of the kleshas , or emotional disturbances, until after 1980, when I became cognizant of something deeper than the physical outer body. Feeling sorry for yourself and feeling dejected are the work of the ego. It fosters a passive aggressive pride that says, I don’t want to go forward, and I don’t want to do anything, because, Why should I? This is self-defeating and does not follow sound yogic philosophy, to be concerned about the impermanence of our human body.

I remember listening to an NPR interview with a fellow who was completely paralyzed, except his big toe. It occurred to me that everything in my body was basically fine, except my lower left leg. Here’s this man who communicates with people by moving his big toe! That really struck me. This interview made me see how one can fall into the trap of feeling hopeless and unable to pick oneself up, and inspired me with his tenacity to thrive. It’s important to be thankful for what you have. Some years after my accident, I was able to cultivate gratitude.

SOMETHING TO OFFER

As I’ve been able to identify more with what I can achieve rather than my limitations, it’s become clearer to me that I might have something to share with people. They might not have a sciatic nerve injury, which is unique, but injuries are not unique. So many practitioners have many obstacles such as osteoarthritis, comorbidities, scoliosis, cancers, aging, etc. People began to ask me about their problems. I think I had empathy, having been there, through a whole range of negative emotions, having practiced classical asanas that are no longer advisable. I would ask myself, "How can I start to adapt certain asanas so they are therapeutically sound and uplifting? I became more and more interested in modifications that benefited me. And I was able to cultivate that eye, that intuition, when working with students.

When I say intuition, I mean it in the sense that everybody has it. Everyone has intuition, and the next step is to tune into one’s inner wisdom/buddhi As I taught more, I developed an interest in helping

others. Helping students online can be done. Modifying poses with commonly accessible props as well as modifying the stages students will potentially be able to accomplish is my goal. Not all will have an array of wooden props found in studios, nor someone to help adjust the props. It's not a perfect situation teaching online, but it is workable.

BREAKING IT DOWN

My teacher Mary Dunn was always supportive and objective when helping me. She'd say, “Rebecca, try this,” and she never made me feel like there were limitations. She was always inspiring. Mary had such a gift for helping others help themselves. That is the goal of my teaching, too. I was inspired by Mary, Guruji, Geetaji, and Patricia Walden. Dean, who has helped me tremendously, is another inspiration. He worked with me to put together my yoga foot brace that I wear while practicing and teaching.

I’m interested in breaking a pose down into its principal actions, its key characteristics, its signature components, the natural way a pose can flow, or how it doesn’t flow. How does one access the fluidity? Where do people get stuck? I sort things out with the use of props, if necessary, and I try to make it an enjoyable learning and discovery process. I do believe that sukha is a very key word—sthira sukham asanam. Sukha is happiness, happiness in the yogic context of neutrality and equanimity, sthira is steadiness.There should be sthira sukham asanam always present in our practice. People have told me I have inspired them to keep going when things get tough. I’m deeply honored and happy that I’ve helped someone feel that they can go a little further. Many of my students are teachers. They find that this approach is helping them be more effective in supporting their students. Just a small way of looking at the asanas with a different eye, a compassionate eye, a friendly eye, an analytical eye. Self-analysis is really important. You have to analyze it for yourself.

LEARNING FROM THE IYENGARS

Guruji gave me the biggest gift of self-actualization. At an early U.S. convention he saw my left leg and said, “Let that side be your guru and teach the rest of you.” I saw Guruji in Pune in '87. He had that critical, objective eye. It was the straight shot of an arrow to the problem

The Light | Fall 2022 7

Everyone has intuition, and the next step is to tune into one’s inner wisdom/buddhi.

with a pose. He taught us the principles of trial and error, comparative study, and judicious practice. Over the years, this has been a motto for me. As Guruji has told his teachers, we need to put ourselves in the students’ situation. He would try to emulate a person’s problem. He could emulate a kidney problem, a neck problem, even a brain tumor, and figure out how to help. Abhi, Geetaji, and many others who worked closely with Guruji speak of his brilliance in this regard. A small atom of that is the ability to have an interest. Mary Dunn always said you have to keep a keen interest, a deep interest in pranayama, in asana. Guruji expected us to dive deep into this subject.

When I began traveling to Pune to study in the late 80s, Guruji was teaching less and less of the public classes, although during the intensives he did teach. I am definitely part of a cohort born and bred in the briar patch of Geetaji Iyengar during the late 80s, 90s, and 2000s. She was holding all of the public classes. I was always impressed with how seamlessly she would teach a pose in stages. Take, for instance, Uttana Padasana. That's a complex pose with the arching of your neck, arms and legs extended out and your back, abdomen, dorsal—How do you get someone into that pose? “Have your knees bent, keep your elbows down to support so you don’t put all the weight on your neck. Get the arm action.”

Look into the Preliminary and Intermediate course booklets. Prime example Utkatasana: arm action followed by leg action, leg action followed by arm action. Arms and legs together. That inspires me. When you learn an important principle of Geetaji’s and apply it to your practice of any particular pose, your understanding deepens. You begin to see where a student might have problems, and you can give them suggestions.

ALL TEACHING IS MULTILEVEL

Our center is a small place, 20 or so students would be a big class. My students are central Pennsylvanian people, with a few advanced practitioners, and our teachers. I went up for my Junior I, II, III, and Senior I Assessments working with my local core group, as well as my outof-town workshop participants. But those came later. I wasn’t doing a lot of traveling in the beginning. Being inspired to keep fresh and teach a Kurmasana action, or Ardha Baddha Padmottanasana upright, or some portion of a challenging backbend. I always thank my Monday morning gentle yoga class of women and a few men at the Center for Well- Being. They were my humble students who would give me advice or say, “This

Something I learned from my first teacher Ramanand Patel is that, when someone is experiencing an emotional breakdown, don’t run, hug, and coddle. Give them space.

variation really worked for me,” and I would say, “Did you know this was the pose you were working on?” And they would be shocked when they saw the picture in Light on Yoga. So my multilevel approach really came about as the result of teaching my local students.

As I developed our teacher education and out-of-town workshops, I was in a bigger community. There were people with different abilities. The challenge is keeping everybody going, enjoying their practice in a community. Some people can do more, some can do less, and, as a teacher, one develops the skill of doing three things at once. Abhi has done that at conventions and online, giving modifications to a wide range of people.

WHEN PROBLEMS ARISE

Something I learned from my first teacher Ramanand Patel is that, when someone is experiencing an emotional breakdown, don’t run, hug, and coddle. Give them space. Don’t immediately try to fix it.

At first it seemed insensitive, but now I see the wisdom. Depending on the student, a teacher shows karuna (compassion), in different situations, upeksha—remaining impartial or neutral. You may have to be indifferent to the fact that they are having a breakdown, but make them feel comfortable to be in class, should they choose to remain. Indifference may sound crude to some people. Strive to keep your pace as a teacher without drawing too much unwanted attention to the student. Always follow up after class with sincere support.

I remember teaching at Feathered Pipe Ranch and someone was having an emotional time. I didn’t know what was going on. So I changed the format of the class with students in standing poses facing the other direction to offer privacy to this particular student, so they could be free with their emotions in Adho Mukha Virasana. Afterwards, we talked.

You want to be able to support students, and you don’t always know what their background is. This is why cultivating sensitivity, maitri (friendliness), karuna

8 The Light | Fall 2022

COMPASSIONATE EYE CONTINUED

(compassion), mudita (joy), and upeksha—neutrality is necessary for all yoga teachers.

COMMON SENSE

Common sense is not common to you until it becomes a particular part of your mental bank of memories, thinking process, and your being-ness. Common sense does dawn on you at some point. Studying with Geetaji, I would frequently think, “Why did I not think of that myself?” Now, I’d like to think I am able to apply her principles of common sense! Geetaji is no longer with us, but she’s always with us in our hearts. Her legacy, like Guruji’s lives on. She’s always with me. Her teachings were so impactful and so deep. I still listen to her recordings frequently.

CONTINUING TO LEARN

I recently took a class online with Abhi where she used the chair to twist in a way that was so effective, and new to me. My eyes opened up. We are always students at heart and I do my best to catch as much as possible of Abhi’s teaching. I want to pass that feeling on to students to help them see and do more, and be more alive in their practice and teaching.

Our teaching is unique to us because of our own experience, but our foundational fundamental learning has come from the Iyengars. Don’t get me wrong, we all have plenty to contribute. I find myself taking one aspect of a particular teaching point of Geetaji’s and developing a whole class with this in mind. We give credit to the Iyengars, and take credit for what we develop in our own practice. Humility is necessary to remain a student of yoga.

MOVING FORWARD

Iyengar Yoga is moving. It’s fresh, and it’s going with the times. Many senior teachers are in their 70s now. Everything is changing. We are aging. As our practices change, the way we teach is going to change. I love that, in this system, we address the needs of so many different students. We have to pay attention to the younger students coming up, and guide them to feel fulfilled. We consider those in the class who can do more, and inspire them. So it isn’t just us old folks showing, “Here is a chair, here is a block, here are multiple props.”

Multifaceted teaching, the ability to teach in this stellar way that is expected of us, keeps us alive. It keeps us teaching longer, because we are held at attention with what we’ve learned, yet we can go with what we are personally capable of doing.

I’ll tell you there are a lot of poses such as arm balances that I can no longer complete as when I was younger, due to shoulder problems, hip replacement, and leg issues. Like anybody else, there are problems that arise along the way. But I still feel motivated to do things. I recently taught an arm balance class, and said to myself, “Wow, these movements are hard for me!” But I wanted to take it as a challenge, to help people help themselves. Those who can’t do the classic pose will see, “Oh, here’s what I can do. I can go this far, and others can go farther.” As a student, teacher, and mentor, I’m on my toes staying alert and present. Being in the present moment without regrets that certain asanas within my practice are over for me. Religiously maintaining my daily pranayama and meditation practices is essential. How else do we stay fresh, alert, and honest?

Whether a seasoned practitioner comes to class, or an aging, long time beginner, I’m held accountable. Thanks to the Iyengars and all my mentors, I feel motivated to keep a high standard; it keeps me alive as a practitioner and, as a result, keeps teaching fresh.

The Light | Fall 2022 9

Humility is necessary to remain a student of yoga.

Rebecca Lerner in Dwi Pada Viparita Dandasana

10 The Light | Fall 2022 Iyengar Yoga with Brian Tradition • Learning Practice • Study • Teaching www.iybrian.com

From Breath to Prana:

A Review of Prashant Iyengar’s Educational Lectures on Pranayama

BY PAULINE SCHLOESSER, PH.D

This article is a continuation of a project to bring to light Sri Prashant Iyengar’s lectures on YouTube. Here the focus is on 10 lectures (Sessions 25–34) dedicated to the subject of classical pranayama. Prashantji’s lectures contain many complex ideas; so many that it would be impossible to summarize them all in a few short paragraphs. Instead, I have identified a few of Prashantji’s central aims that seem to connect the lectures.

These include:

•

An attempt to define classical pranayama in its mystical and philosophical context

• A contrast between classical pranayama and what is commonly taught as pranayama today

• Practical demonstrations, through conducted audio classes, of shvasayama and pranayama to illustrate his points.

• An argument for the necessity of pranayama for any serious yoga endeavor.

What follows is a brief introduction to each lecture, with a link to the actual lecture on YouTube.

Pranayama is much more than the voluntary manipulation of breath or nostrils. Pranayama is regulation of prana, or life force.

Session 25: Koshas as the Context of Pranayama

Session 25

backdrop for understanding pranayama. In this session, the observation and regulation of breath (shvasayama) is distinguished from the regulation of life force (pranayama). And the first of the five koshas, annamaya kosha, is described.

Session 26: Pranayama Works through the Pranamaya Kosha

As yoga has become popular, more people have been introduced to pranayama. But it is not really pranayama in the classical sense. Pranayama is much more than the voluntary manipulation of breath or nostrils. Pranayama is regulation of prana, or life force. And this has to be understood in reference to the pranamaya kosha. Therefore, the entire kosha system must be the

You know that you feel good after a session of what we call pranayama, but did you know genuine pranayama works to transform our personalities? This happens when one accesses the pranamaya kosha, which houses the six chakras. Prashantji explains that the chakras have everything to do with our deep-seated tendencies, or vasanas. Each chakra governs a different set of tendencies, from our survival habits to our sense of identity, to our heart-filled passions. Pranayama helps us to burn the six enemies: anger, greed, delusion, pride, envy, and infatuation. So if we want our yoga to evolve towards samadhi, pranayama is essential. And if samadhi is out of reach, pranayama works on our culturing of our consciousness. This is because pranayama gives access to the pranamaya kosha The six chakras and their governances are described in this session. The importance of managing this inner infrastructure through pranayama is an essential key to spiritual culturing and development.

The Light | Fall 2022 11

Session 26

Session 27: Mystical Aspects of Pranayama and Manomaya Kosha

Session 28: Vijnana and Anandamaya Koshas and their Atmas

Session 27 Session 28

Before continuing his discussion of the koshas, and manomaya kosha in particular, Prashantji introduces us to the mystical aspect of sound forms as Shakti, or divine energy. These divine energy forms are necessary for essential pranayama, which has the power to work on our vasanas, and thus our destiny (prarabdha) in life. We learn that each of the six chakras has a letter form, called an akshara. These aksharas are indestructible forms of shakti. We start with “la,” “va,” “ra,” “ya,” and “ha.” If you combine each of the vowel sounds with each of the consonants in Sanskrit language, you get a myriad of divine sounds forms that resonate uniquely in the human embodiment. The silent chanting of Sanksrit sounds are the secret technology of vasana management in yoga.

A second theme is the five pranas: apana, prana, samana, udana, and vyana, which are energies that govern different parts and functions of the embodiment. The third theme is the glory and divinity of the nostrils. Yoga shastra has postulated “twin divine physicians” who guard the nostrils and keep impurities out. They are called “ashwini kumars.”

Then there is a continuation of the five koshas with a discussion of the third kosha , the manomaya kosha Manomaya kosha should not be interpreted as “mind.”

Rather, the manomaya kosha holds our karmas that will manifest in future lives. Yoga lore holds that there are 8.4 million classes of life, and we have been all those 8.4 million life forms before. The karmas of these lives are stored in the manomaya kosha. Our future incarnations will be directed by this storehouse in the manomaya kosha

More discussion on koshas takes place here; the vijnanamaya kosha is defined as containing the inner Self, the transcendent individual atma, who is free from karma and the effects of karma. Then anandamaya kosha is described as the “divinity zone,” “Isvara,” “Brahma,” or “antaryami” within us. Whereas we have some access through our intellect and senses to the first three koshas, the last two are transcendent and inaccessible to the mind. The koshas are also richly described as atmospheres having their own atma, like the sun has an atmosphere called the corona, and its center, called the core.

Just regulating the breath will not be pranayama, and you will not have the profound effect on mind and tendencies.

Pranayama works on annamaya and pranamaya koshas; and this is the context for traditional pranayama in yoga. If you know the technology of tattva kriyas and mantra, you can reach the pranamaya kosha in pranayama and transform your habits, habitual mind, tendencies, and personality. If you are not working with sound forms (bija mantra, tattwa kriya, or vowel sounds) you will not be doing pranayama, but you’ll be doing “shvasayama.” Even shvasayama is a step up from what is commonly touted as pranayama in consumerist culture where what is called “pranayama” is indistinct from mere respiratory regulation. Just regulating the breath will not be pranayama, and you will not have the profound effect on mind and tendencies. That is why it is important to start working with sound forms.

12 The Light | Fall 2022

FROM BREATH TO PRANA CONTINUED

Session 29: Factors that Distinguish Genuine Pranayama from Mockery

•

No understanding of how asana relates to pranayama, or how asana educates us about the breath, breathing, and prana

•

As a corollary, classical pranayama comes within a proper context of adhyatma (spiritual quest) and mysticism, such as the esoteric physiology of the pranamaya kosha.

•

It might also be noted here that pranayama is related to asana by Patanjali in the scheme of Ashtanga Yoga

Session 30: The Difference between Shvasayama and Pranayama

One of Prashantji’s frequent lecturing techniques is to define a concept by what it excludes. Here he defines classical pranayama by divulging how popular or consumer pranayama is a mockery. Today’s popular notion of pranayama is not classical for the following reasons:

• Dealing with the breath as merely respiratory breath; that is making reference to lungs and inhalation and exhalation (which assumes a temporal, empirical mind, not the associated or cosmic-alized mind).

• Ignorance of the pranayama mudra, its context, or even the basic understanding that it is not necessary to block the gates of the nostrils and deviate the septum to control breathing passages in the nose.

• Ignorance regarding the pranamaya kosha in the context of the other koshas; and failure to place pranayama within the context of the pranamaya kosha

• Lack of appreciation for all that the breath does in the external realm as well as the internal realm.

• Ignorance of the five pranas and their different functions.

• Lack of any reference to the distinction between pranayamas which employ the use of mantra and those that do not.

• Lack of reference to prana kriyas (350 sounds forms) or vacchika kriyas (the speech-ly acts) in asana and pranayama and their powers.

Do you know the difference between pranayama and shvasayama? For many years now, Prashantji has been trying to tell us that what passes for pranayama in pop yoga culture is actually shvasayama (Shvasa = breath; ayama = regulation). Pranayama is regulation of prana, vital energy; Shvasayama is regulation of breath.

It’s not that Shvasayama is bad and pranayama is good. Shvasayama is a necessary precursor to pranayama. Studying the breath, then regulating the breath is done before prana kriyas, tattva kriyas, and chakra kriyas; it is also done as a break after a certain set of kriyas has been performed.

But in pop yoga culture, no one seems to understand this distinction. What they are presenting is actually shvasayama and not pranayama. Moreover, gross and low-tech blocking of nostrils with the fingers is presented as digital pranayama . As discussed in the previous lecture, there is a traditional pranayama mudra that must be played delicately on the bridge of the nose, with tips of the thumb joining those of ring and small finger. Then, the placement of the fingertips is specific to the cartilage just beneath the bony

The Light | Fall 2022 13

Session 29

Session 30

structure of the nose. The hand should be thought of as a beautiful “ornament.”

A very important aspect of the breath that goes unnoticed in pop yoga culture is its freedom from karmic shackles. Now here is a fascinating discussion of how the practice of real pranayama leads toward moksha, liberation. You’ve always known you should practice pranayama regularly, but why? It is not about respiratory fitness or health; pranayama is intended for the culturing of consciousness that can put us on the road to samadhi.

While the mind and body are limited by so many factors, including karma, the breath is like a newborn baby every cycle. It is pure and available to us, most of the time working for us, in every act, thought, and emotion. For every act, there is a corresponding breath that allows it to happen. For every emotion, there is a typical kind of breathing pattern. For every state of mind, there is a corresponding breath. These things need to be observed, studied, and understood before one undertakes pranayama

To give us a taste of the kind of shvasayama, that prepares one for pranayama, Prashant conducts a short class. We are asked to perform some supine asanas and start observing the breath. Then we get into the interactive culture of body, breath, and mind systems working for mutual benefits. After some time, “uddiyanic mannerisms” are suggested, whilst observing specific regions of the body. We are instructed to change the nature of the breath: from thick and pneumatic to thin and rarified. We are encouraged to observe the distinction between breath “ploughing” and breath “seepage.” Then we are introduced to “graphic modes” of the breath. These are some of the gems regularly given in Prashantji’s pranayama classes. Of course, the result is a progressively cleansing and soothing experience that takes the mind into what Prashant likes to call “meditativity.”

Session 31: Breath is the Vehicle for Prana

Did you ever wonder where prana would fit on the Sanhhya table of metaphysics? Well, if it’s not Isvara or Purusa, then it has to be Prakrti, right? As it happens, according to at least three different Shastra sources, Prana is on the level of Buddhi tattva, which is one generation down from mula prakrti

The import here is that if we have access to prana, we can involute, dematerialize, and transform from our mind, intelligence, and identity to citta—the cosmic consciousness. We can take ourselves back to nearly the subtlest form of prakriti by becoming absorbed in prana And yoga technology of pranayama does just that.

Prashantji divides the mind into two categories: vasanic mind and pranic mind. The normal, everyday mind we use in the business activity of life is vasani; it moves with our preferences and aversions toward and away from various external objects. Then there is the mind that is conditioned by pranayama: the pranic, purified, and cosmic-alized mind.

Session 32: Patanjali’s Criteria for Pranayama

Having explained the necessity of using sound forms for breath to become pranic, Prashantji now

14 The Light | Fall 2022

FROM BREATH TO PRANA CONTINUED Session 31 Session 32

A very important aspect of the breath that goes unnoticed in pop yoga culture is its freedom from karmic shackles.

reviews other criteria for pranayama, from YSP II. 50. “Bahyabhyantara Stambha Vrittir Desa Kala

Sankhyabhih Paridrsto Dirgha Suksmah.” If Paridrstah is regulation, it is to be applied to place or region (desa); to the issue of timing (kala); and performed repeatedly (stambha vritti ).

So, pranayama cannot be just watching the breath and having slow soft inhalations or exhalations. We’ve already seen that traditional pranayama is done with sound forms to access the pranamaya kosha. But now Patanjali tells us that there must be Desa Paridrstatah: a mental focus on a specific region in the body. In Prashantji’s classes, these desas number five or six: the head, chest, upper abdomen, lower abdomen, pelvic floor, and sometimes the back. Obviously, we are not dealing with respiratory breath here. We are dealing with esoteric anatomy: breathing channels or “nadis” said to exist all over the embodiment. The location or region qualification is about mind sensitivity of breathing channels in whatever region you have chosen.

Kala Paridrstatah, or timing of the breath cycles, has to do with volume and velocity of breath. So we can increase the volume of the breath by shortening the duration of a cycle in a thick, quick inhalation or exhalation. Or we can increase the volume with a longer, thinner, more rarefied breath. Kala is managed by regulating the speed of inhalation or exhalation as well as the volume of breath handled.

Then, Sankhya Paridrstatah requires that there must be repeated identical cycles: they must be focused on the same particular region, with the timing (velocity and volume), to qualify as pranayama. If you have not chosen a region for the sensitivity to observe, or if you are changing the velocity and volume every other cycle of breath, this is not yet pranayama. We may start like this, but eventually we have to have repeated consistent cycles to get toward pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi.

Session 33: Nostrils and Prana Kriyas Are High-Tech Means to Divinity Within Us

Here we have a session in which Prashantji conducts a pranayama class. With a spotlight on the marvels of the human nostrils, we are educated about their parts and the mysticism of the divinities that guard the gates of the nostrils. This orientation is important to sensitize us to the importance of nostrils and their parts: membrane and membrane carpets, septum, floor, roof, and outer gates.

Next Prashantji educates us about prana kriyas. These are divine sound forms, called matrikas in the mantra shastra. Using the vowels as sound forms, we discover that the pathways of the breath and prana will change in the nostrils, depending on which vowel you use. That is why, in esoteric yoga, pranayama is considered “nada sadhana,” or a practice of sacred sounds. The sounds channelize the breath into prana nadis, or internal rivers of divine energy. And this is the essential difference between shvashayama (mere breath regulation) and pranayama, regulation of life force.

Prana is the manifestation of Devi within us, he says. The same sound forms (a to ksa) that unfolded the cosmos can be utilized within us to expand the consciousness. So also for sacred names, like the 1000 names of Visnu, or Devi, and mantras. There are too many kriyas listed to recount, but the important point is that using sound forms is high technology for reaching the pranamaya kosha, and these must be done within the parameters set out by Patanjali in combination with place, timing, and repeated cycles.

Session 34: Pranayama Opens the Corridor to Samadhi

Pranayama does not happen without Sanskrit sound forms. These could be vowels, combinations of consonants with vowels, sacred mantras, or names

The Light | Fall 2022 15

Session 33 Session 34

The sounds channelize the breath into prana nadis, or internal rivers of divine energy.

FROM BREATH TO PRANA CONTINUED

of deities. This should be understood prior to digital manipulation of the nostrils. Otherwise, we might fall prey to the common notion that anyone and everyone can just start blocking their nostrils as in anuloma, pratiloma, nadi shodhana, etc., without understanding the traditional context of pranayama, which is adhyatma, or the spiritual quest to realize God or realize the Self. It won’t work to reform the citta

Pranayama makes us feel serene, sublime, and wonderful. But this is not its traditional purpose. According to Patanjali, pranayama has one purpose: to launch us to the inner limbs of yoga (antaranga sadhana), by removing the veil of ignorance covering our inner light. YSP II.52 says “Tatah ksiyate prakasavaranam.” From that (pranayama) the covering of illusion (avaranam) is destroyed (ksiyate). Then YSP II.53 says, “dharanasu ca yogyata manasah.” Fitness and qualification (yogyata) of the mind (manasah) for concentration (dharanasu) are rendered.

In our consumerist culture, we are always looking for what asana or pranayama can do for us, Prashantji notes. So we may approach pranayama as something that will make us feel good. Prashant wants us to place asana and pranayama in the context of Patanjali's Ashtanga Yoga. There we see that the purpose of asana is to prepare the mind for pranayama. YSP II.48 says “tatah dvandvah anabhighatah,” from mastery of asana (tatah) there is a cessation of disturbance (anabhighatah) of dualities (dvandvah). So the unafflicted mind is the outcome of asana in a classical sense, not physical fitness. Similarly, the outcome of pranayama in the classical sense is to launch us into samyama, the antaranga sadhana of dharana, dhyana, samadhi, and not to make us feel relaxed and content. “Pranayama is a corridor,” Prashantji says, “and all meditation must be launched by pranayama.”

Pauline Schloesser, Ph.D., CIYT-Level 2, C-IAYT, lives in Houston, Texas, and teaches in her studio, Alcove Yoga. She is currently working on a collaborative project to transcribe Prashant S. Iyengar’s series of lectures on YouTube.

16 The Light | Fall 2022

The unafflicted mind is the outcome of asana in a classical sense, not physical fitness.

Asana

The Power of Inversions Heart and Circulation Upside Down

BY ROGER COLE, PH.D. INTRODUCTION

Here’s a guide to deepening your experience of inverted asanas by applying science to practice. Inversions, when performed skillfully, redirect fluid flows and pressures in your body in ways that can improve your health and quiet your mind.

B.K.S. Iyengar famously said, “Yoga is a practical art,” meaning that when you practice, you reap practical benefits. You’ll get the most out of this guide if you do the quick practice demos suggested along the way.

We’ll focus narrowly on blood circulation and the heart because this lays the foundation for understanding how inversions also affect fluid flows in the lymphatic system, brain, lungs, and elsewhere. We’ll emphasize two of the most useful effects of inverted asanas (1) draining and filling, and (2) stimulating reflexes.

Draining and filling refers to draining fluids away from one part of the body and filling up another. For example, elevating the legs enhances circulation not only by helping blood drain out of leg veins, but also by increasing the pressure, and therefore the volume, of blood filling the heart.

Stimulating reflexes refers to activating fluid pressure sensors to trigger beneficial physiological responses. For example, increasing the volume of blood filling the heart triggers a set of reflexes that, over time, can reduce your body’s overall blood volume. Reducing the body’s blood volume can lower blood pressure.

Although inversions have well-documented, important physiological effects, there is not enough clinical evidence to justify making medical claims about them, and some inversions may be risky for some people. Only attempt poses that you know are safe for you, and only teach poses that you know are safe for your students. If you have any doubts, or have a medical condition, or want to use yoga as therapy, please do it only with the approval and supervision of qualified medical professionals.

Practice Demo Round 1

Before we dig into the science, now would be a good time to do the first practice demo, if you are willing and able. It should only take a few minutes. It will help you intuitively understand the anatomy and physiology of inversions in ways that could never be expressed in words or pictures. We’ll revisit the same practice later.

To practice, simply get into the postures listed below one after another, doing the sequence first in forward order, then in reverse order. Stay in each position very briefly — just long enough to get a sense of how it feels, then move on to the next one and compare how it feels. (This is harder than it sounds, because the poses feel so good you’ll probably want to stay in them much longer.) If you can’t do all the poses, just do the ones you can. Set up your props in advance if possible (see photos).

Sequence (10 to 30 seconds per posture):

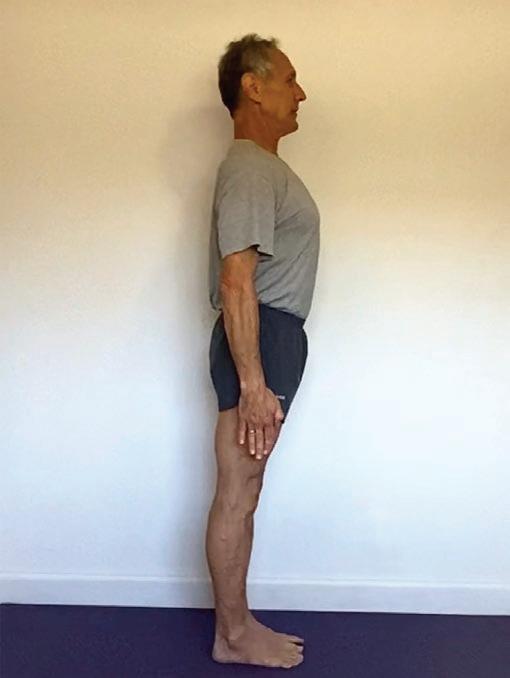

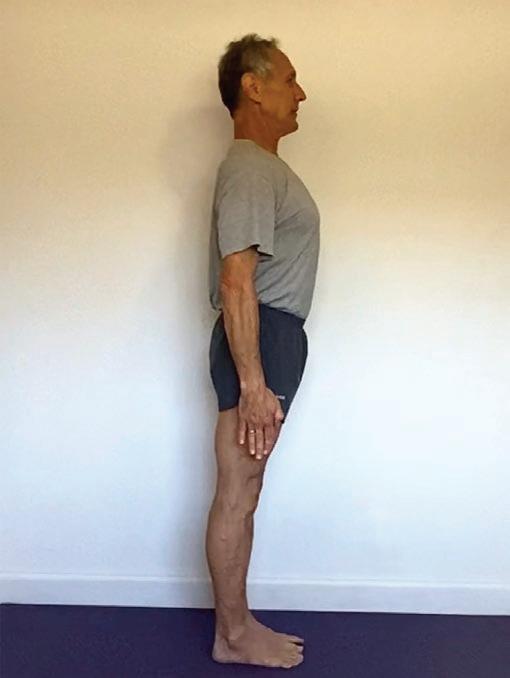

1. Tadasana (standing upright)

The Light | Fall 2022 17

ON

Asana 1. Tadasana

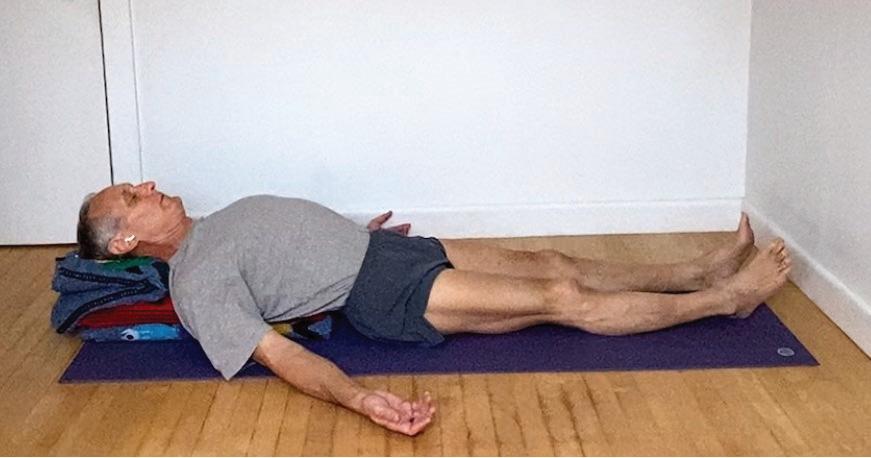

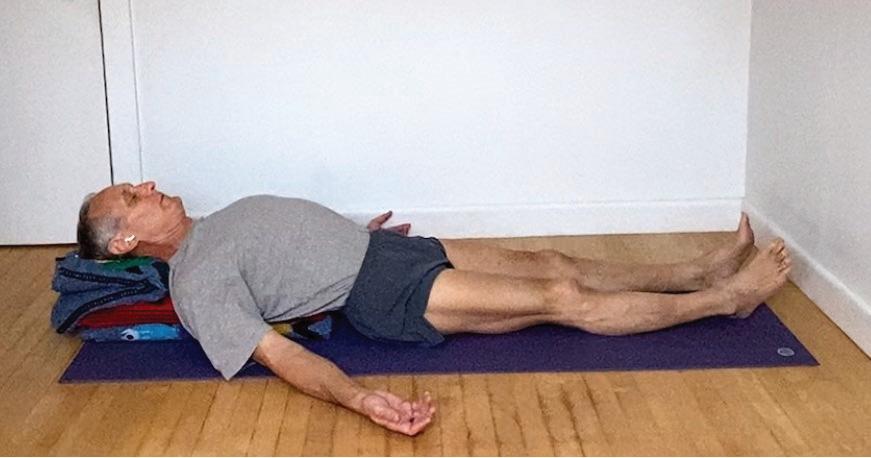

2. Supported Savasana (lying with legs and pelvis on the floor, back elevated on long folded blankets, head supported higher than the back.)

5. Viparita Karani (lying with pelvis elevated on stacked, folded blankets, legs up a wall, chest lifted, tops of shoulders and head on the floor)

3. Savasana (lying flat with legs, pelvis, trunk, and head all on the floor at the same level, or as close to level as you can comfortably manage)

5.5 Add a head support to Viparita Karani

4. Supported Urdhva Padasana (lying flat with legs up a wall, and with pelvis, trunk, and head all on the floor at the same level)

18 The Light | Fall 2022 ON ASANA CONTINUED

Asana

2. S

upported Savasana

Asana 3. Savasana

Asana 4. Urdhva Padasana

Asana 5. Viparita Karani

Asana 5.5. Viparita Karani (head elevated)

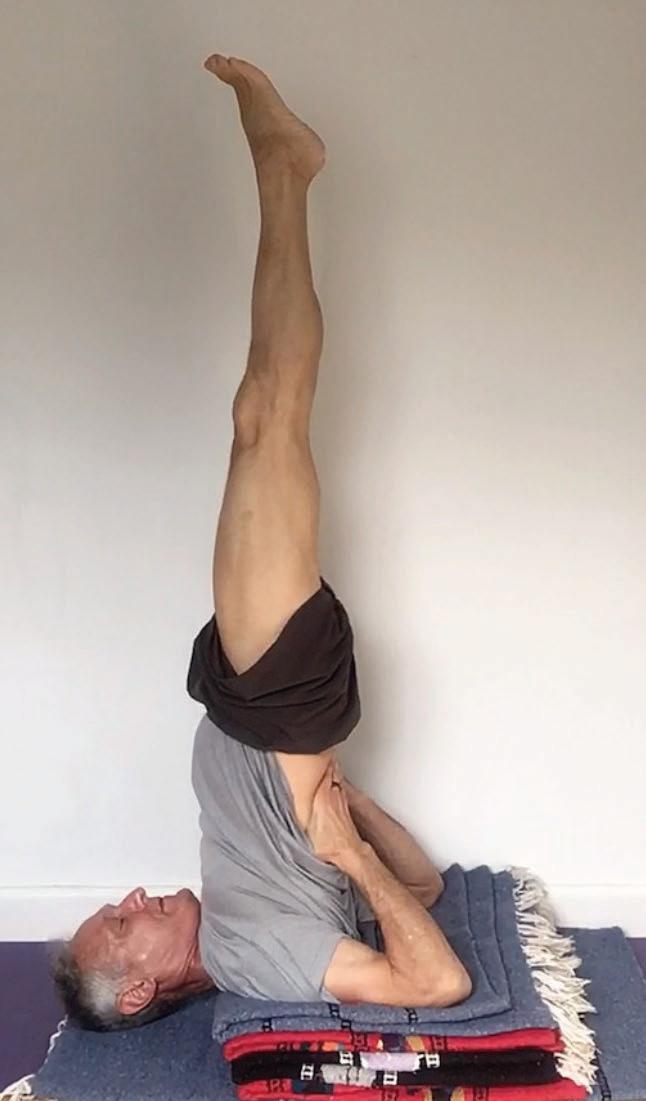

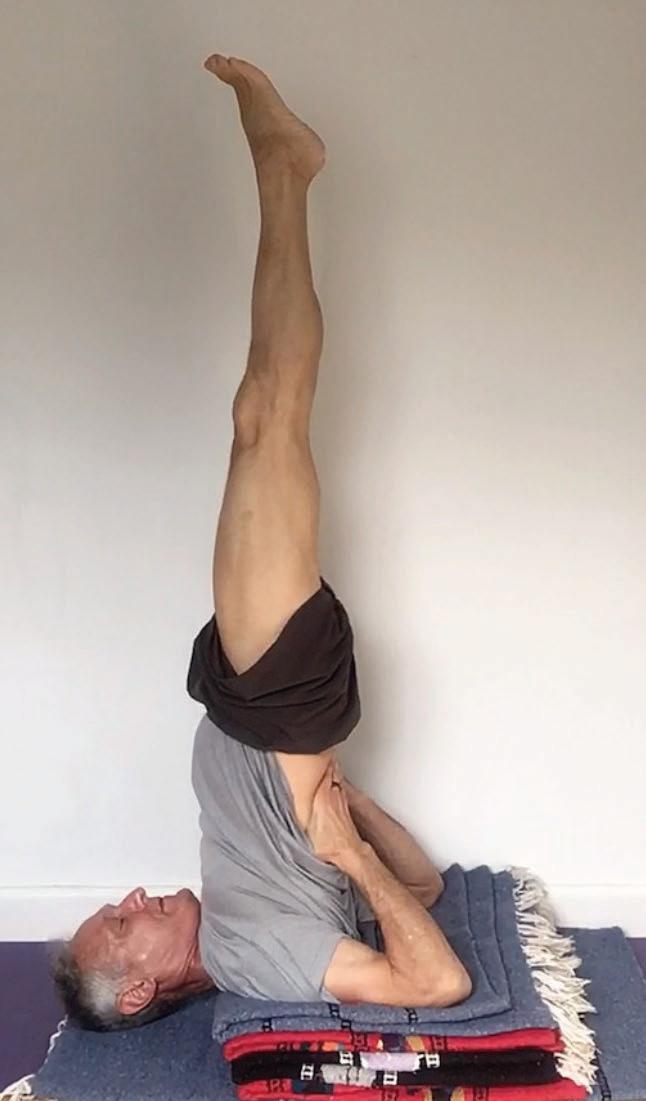

6. Salamba Sarvangasana

(Shoulderstand with the back of the head on the floor, shoulders elevated on the edge of a stack of folded blankets or a comparable prop, and the shoulders, trunk, pelvis, and legs in a vertical line, or as close to vertical as you can comfortably manage)

BASICS OF CIRCULATION

The heart pumps blood out through arteries, and blood returns to the heart through veins. This is circulation. The heart functions as if it were two pumps; one circulates blood through the lungs, the other circulates it through the rest of the body. Here, we’ll only talk about circulation through the rest of the body.

The heart pumps out blood to the body at high pressure. The blood exits the top of the heart through a single, giant artery called the aorta. The aorta branches into large arteries, which in turn branch into smaller and smaller arteries, which finally branch into fine capillaries that reach every cell.

The capillaries deliver oxygen, nutrients, water and other important molecules to the cells. The cells excrete carbon dioxide and other waste products into the fluid that surrounds them (the interstitial fluid).

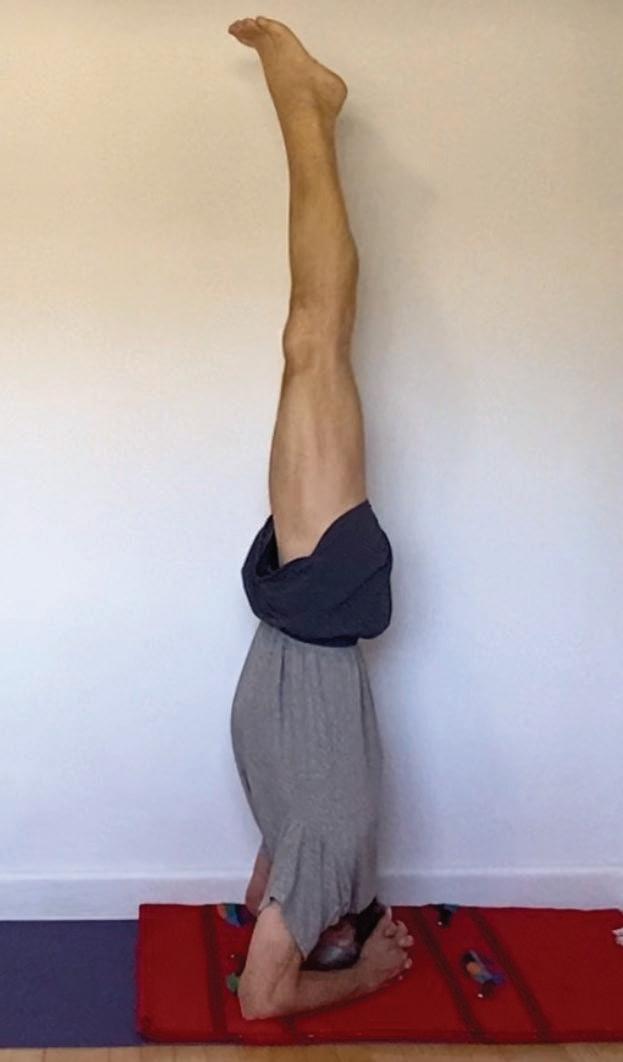

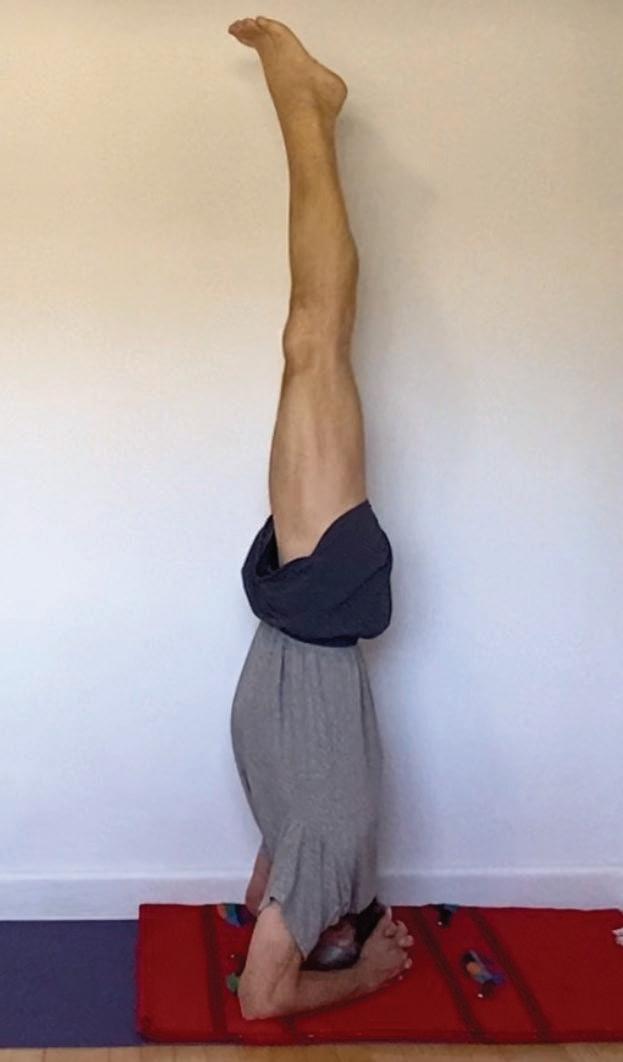

7. Salamba Sirsasana I

(Headstand I, top of head and forearms on the floor, the rest of the body in a vertical line, or as vertical as you can comfortably manage)

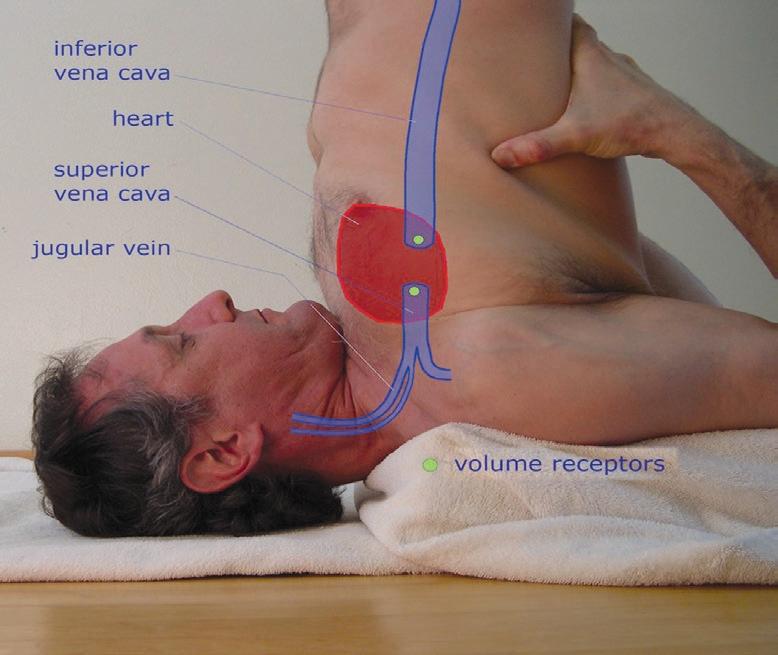

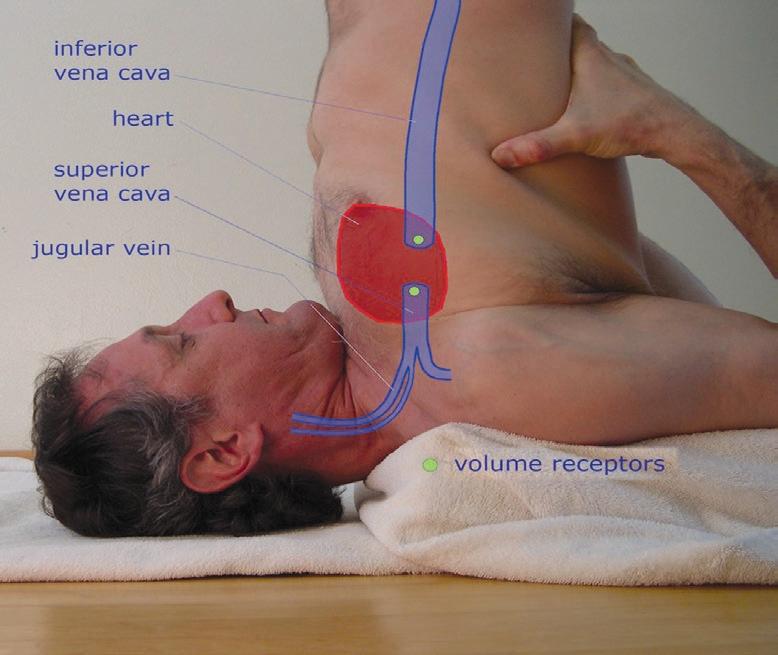

On the path back to the heart, the venules converge into small veins, which converge into larger and larger veins, until all venous blood ends up in one of two giant veins, the superior vena cava or the inferior vena cava.

The blood from the capillaries begins its journey back to the heart in tiny veins called venules. The venules collect water and small molecules from the interstitial fluid. On the path back to the heart, the venules converge into small veins, which converge into larger and larger veins, until all venous blood ends up in one of two giant veins, the superior vena cava or the inferior vena cava (see illustration 1). These two veins deliver blood to the same receiving chamber of the heart, the right atrium.

8. Repeat the same sequence in reverse order

The Light | Fall 2022 19

Asana 6. Salamba Sarvangasana

Illustration 1: Venae Cavae, Heart, and Volume Receptors in Salamba Sarvangasana

Asana 7. Salamba Sirsasana

The lymphatic system runs roughly parallel to the venous system and also carries fluid back to the heart. It collects interstitial fluid containing waste (large molecules, bacteria, cellular debris, etc.) in lymphatic vessels. Once the fluid is inside the vessels it is called lymph. Lymphatic vessels, like veins, converge into larger vessels as they progress toward the heart. Along the way, lymph passes through nodes that filter and process it. All the processed lymph ultimately drains into the superior vena cava, where it becomes part of the venous blood that returns to the heart.

Unlike arterial (outbound) blood, the inbound venous blood and lymph operate at low pressure. They do not have a pump pushing them along. Several mechanisms move these fluids. One is the contraction of skeletal muscles that squeeze the veins and lymphatic vessels. Many of these vessels, especially in the legs and arms, have one-way valves, so squeezing them reliably propels venous blood and lymph toward the heart. Another mechanism is breathing. For example, the same vacuumlike negative pressure in the chest that draws air into the lungs during inhalation also helps draw venous blood and lymph toward the heart. A third factor, gravity, can be the most powerful driver of venous and lymphatic return to the heart under some conditions; however, under other conditions, it can be a strong impediment. We’ll focus next on ways we can strategically use gravity in yoga to aid desirable draining and filling of arterial blood, venous blood, interstitial fluid, and lymph.

DRAINING AND FILLING

Fluids flow downhill, so the first rule of draining and filling is to elevate the part of the body you want to drain above the part you want to fill. A crucial point to keep in mind is that the greater the height difference between the source of the fluid and its destination, the stronger the gravitational draining will be and the greater the pressure the fluid will exert below. The source of the fluid does not have to be directly above the destination, it just has to be higher. We’ll sometimes refer to the height difference as the “vertical drop” even when the fluid travels diagonally down or stairsteps down.

The second rule of draining and filling says that because all circulating blood comes from the heart and returns to the heart, the vertical drop that matters most in an asana is not the height difference between the feet and the head (although this still does matter), it is the height difference between the heart and whatever part of the body you want to drain or fill. For example, in any pose with the legs elevated, the strength with which gravity drains blood away from the feet depends much more on how far the feet are above the heart than on how far the feet are above the head. Likewise, in poses with the head below the heart, the degree to which gravity increases blood pressure in the head depends mainly on how far the head is below the heart, with a much smaller influence of how far the head is below the feet.

The main reason for this lies in the venous system, because it contains three to five times more blood volume than the arterial system1. All venous blood returning from body regions below the heart (that is, the legs, pelvis, abdomen, and lower thorax) flows into the inferior vena cava, then into the heart. All venous blood returning from body regions above the heart (that is, the head, neck, upper chest, and arms) flows into the superior vena cava, then into the heart. There are no veins that go around the heart to connect blood in the lower body to blood in the upper body. Therefore, during an inversion venous blood from the lower body cannot drain into or put filling pressure on veins in the upper body, and during an upright posture, veins in the upper body cannot drain into, or put filling pressure on, veins in the lower body.

The situation in the arterial system is more complicated, so we won’t try to untangle it here, but the upshot is that standing upright increases arterial pressure in the legs far more than turning upside down increases arterial pressure in the head. We’ll see how this plays out when we discuss Tadasana and Salamba Sirsasana

20 The Light | Fall 2022 ON ASANA CONTINUED

We’ll focus next on ways we can strategically use gravity in yoga to aid desirable draining and filling of arterial blood, venous blood, interstitial fluid, and lymph.

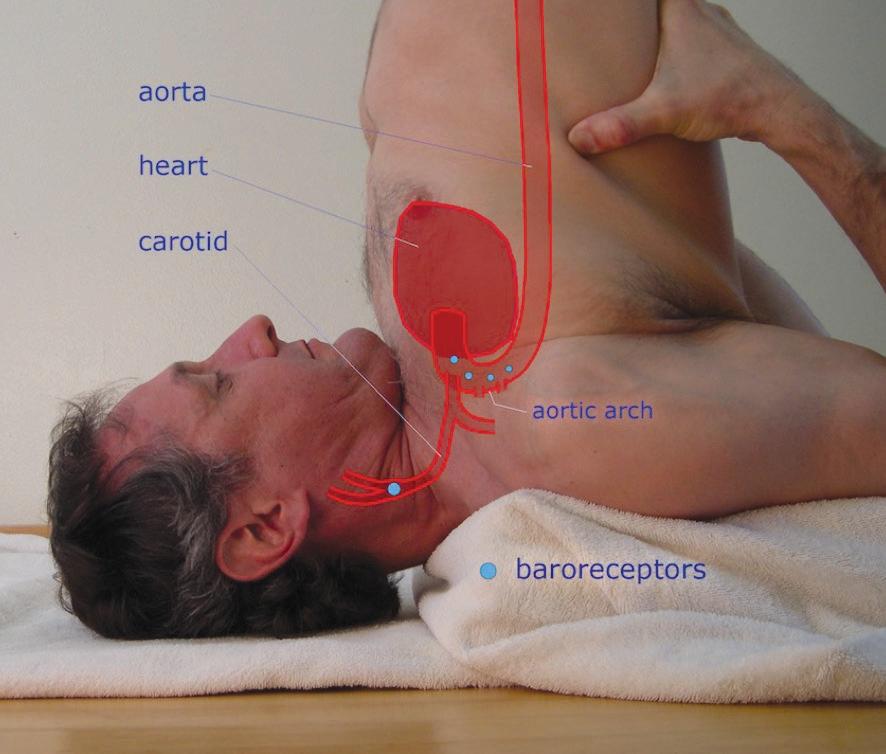

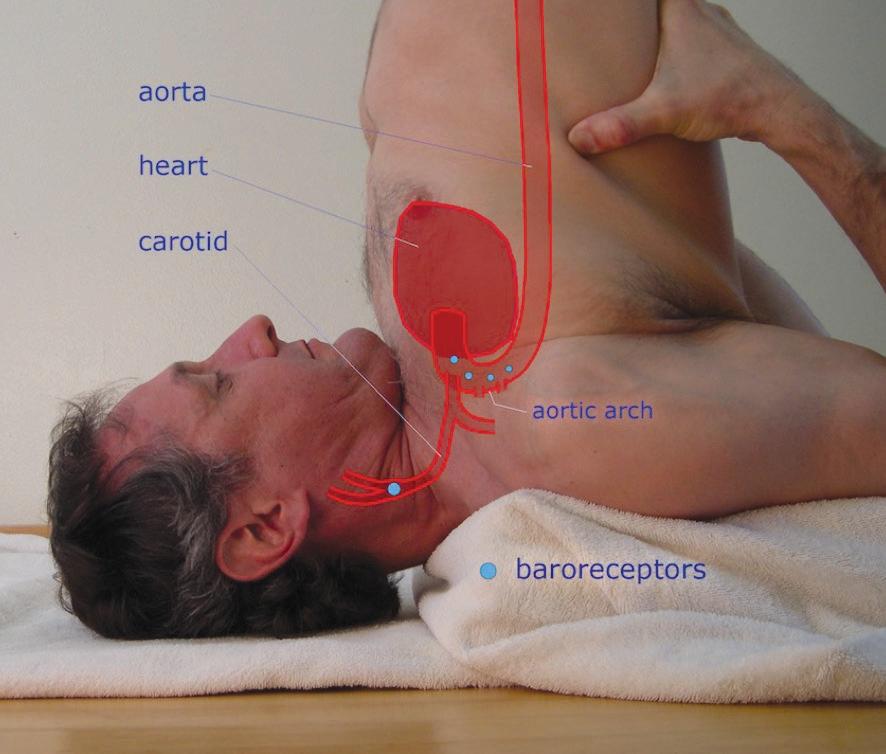

Illustration 2: Aorta, Heart, and Baroreceptors in Salamba Sarvangasana

To make sense of how specific asanas affect draining and filling, it’s useful to know the general layout of some major arteries and veins (see illustrations 1 and 2). The aorta is attached to the top of the heart. It first travels up toward the head a short distance (this is the ascending aorta), then arches over (this is the aortic arch) and finally runs down the trunk to the abdomen (this is the descending aorta).

The first arteries that branch off the aorta come out of the top of the arch, then divide further to deliver blood to the head, neck, upper chest, and arms. Additional arteries branch off of the descending aorta at various levels to supply blood to the trunk. The lower (abdominal) end of the aorta splits into arteries that bring blood to the pelvis and legs.

When we are standing upright, as the heart pumps out blood, gravity opposes its upward flow, and this reduces its pressure. The higher the blood rises, the lower its pressure becomes; therefore, blood pressure systematically falls as blood rises through the ascending aorta, the top of the aortic arch, and the arteries of the upper chest, neck, and head. Meanwhile, gravity accelerates and therefore increases the pressure of the downward flow of blood out of the aortic arch, down the descending aorta, and through all the arterial branches that serve the trunk, pelvis, legs, and feet. When we turn completely upside down, gravity exerts the opposite gravitational effects on the blood in the arteries, including the aorta itself.

It’s very important to understand how inversions affect blood flow and blood pressure in the head, so we’ll take a closer look at its pathways. Arterial blood travels through the neck to reach the head via two carotid arteries and two vertebral arteries. (The illustration shows just one carotid artery and omits the vertebral arteries). Each carotid artery splits into two branches within the neck. The internal carotid artery brings blood to the brain and other structures inside the skull. The external carotid artery brings blood to the face and other structures outside the skull. Venous blood exits the head mainly via two jugular veins. Each jugular vein has an internal and an external branch. (The illustration shows the two branches of one jugular vein.)

When you are upside down with the heart higher than the head, gravity helps push arterial blood downward into the head but it also hinders the flow of venous blood out of the head. The net result is that gravity does not increase blood flow through the head during inversions. It does, however, increase blood pressure

in the head, in both the arteries and the veins. Blood vessels in the brain may be somewhat protected from increased pressure because the skull acts like a closed, fluid-filled box that makes it hard for arteries and veins to expand too much. Blood vessels in the face, nose, eyes, and other areas outside the skull are less protected from elevated pressure, but do have some defense mechanisms.

Gravity-induced changes in blood pressure trigger a number of important and interesting reflex responses.

BLOOD PRESSURE REFLEXES

Gravity-induced changes in blood pressure trigger a number of important and interesting reflex responses. We’ll look at three types of reflexes that inversions or other asanas can clearly trigger: the first are called highpressure baroreflexes, the second are volume reflexes (also known as low-pressure baroreflexes), and the third are local arterial pressure reflexes. Each type of reflex is triggered by strategically-located stretch-sensors that send stronger signals when stretched by higher blood pressure and weaker signals when released due to lower blood pressure.

High Pressure Baroreflexes

The stretch sensors for high-pressure baroreflexes are called high-pressure baroreceptors, or just baroreceptors. The best known of these are nerves embedded in the arch of the aorta and in the carotid artery (see illustration). When these sensors are stretched by a rise in blood pressure, they elicit a set of responses that generally tend to lower blood pressure and otherwise calm the body and mind. When a fall in blood pressure reduces the amount of stretch on these sensors, they elicit a set of responses that generally tend to raise blood pressure and activate the body and mind. One consequence of this physiology is that when you go into poses that invert the heart, it often triggers a relaxation response. Another is that when you do standing poses, it activates you.

High-pressure baroreceptors don’t respond much, if at all, to small changes in blood pressure, but do respond to moderate-to-large changes (in a graded fashion). Many of these responses are fast-acting; for example, a rise in pressure at the baroreceptors almost immediately causes the heart to beat much more slowly, the heart muscle fibers to contract more gently, the smooth muscles that constrict most arteries and some veins

The Light | Fall 2022 21

to relax, and the body to breathe more slowly. Other responses are slower-acting; for example, the rise in pressure on the baroreceptors may gradually reduce the levels of several hormones that make the body retain salt and water, thereby tending to eventually reduce blood volume. Conversely, a substantial fall in pressure at high-pressure baroreceptors does the opposite: it greatly speeds up the heartbeat, makes the heart squeeze harder, constricts blood vessels, and so forth.

This means that finding ease and stillness in inversions can often be the key to unlocking their potency.

Perhaps the most interesting high-pressure baroreflex response, from a yoga perspective, is that stimulating the carotid or aortic baroreceptors can trigger a series of nerve signals that significantly slow down your brain waves.2,3,4 Although this has not been studied directly in yoga asanas, it is almost certainly one of the ways that supported inversions like Viparita Karani quiet your mind. If you want to take advantage of this calming reflex in yoga, it’s important to understand that it is easiest to trigger if your body and brain are already partly relaxed. This means that finding ease and stillness in inversions can often be the key to unlocking their potency. Finally, it’s useful to know that the calming baroreflex has an alerting counterpart: lowering blood pressure within the carotid artery and aortic arch can activate your brain; this may be one reason why standing poses generally wake you up.

Volume Reflexes (Low-Pressure Baroreflexes)

The stretch sensors for volume reflexes are called volume receptors, or sometimes low-pressure baroreceptors. Like their high-pressure cousins, they act to reduce load on the circulatory system when it’s high, and vice versa. The best known volume receptors are embedded in the right atrium, at the junctions where the superior and inferior venae cavae come in to deliver blood to the heart. When heart filling pressure increases, it stretches these sensors, and they in essence tell the body and brain that there is an increased volume of venous blood filling up the heart. This elicits a set of reflex responses that tend to reduce the volume load on the heart. A fall in filling pressure elicits opposite responses.

One volume-unloading reflex response to the stretching of the heart’s volume receptors is immediate dilation of veins in the arms and elsewhere so they can, in effect, temporarily store excess blood. Another is increased urine production by the kidneys so the body excretes more liquid. Stretching these receptors can also induce several of the same volume-reducing hormonal responses that the high pressure baroreflexes do. In addition, stimulating the volume receptors signals the heart to secrete its own powerful, home-grown, volumelowering chemical. There are no reports of volume reflexes affecting breathing or brain waves the way that high-pressure baroreceptors do, but this can’t be ruled out because it has not been studied.

Local Arterial Pressure Reflexes

The stretch sensors for local arterial pressure reflexes are located in the walls of certain arteries, for example in tiny arteries in the nasal passages. These reflexes can automatically constrict the arteries when they are filled up at high pressure. The constriction can expel excess blood and limit refilling. This may defend the arteries against damage if blood pressure gets too high during inversion.

With these reflexes, anatomical pathways and principles in mind, we’ll now explore how draining and filling work in the asanas of our demo sequence.

PRACTICE DEMO ROUND 2: EXPERIMENT AND FEEL

The focus of this round is to notice the specific sensations described in the observation instructions below, and to feel how they change when you transition quickly from one pose to the next (holding, again, for 10–30 seconds). It would be ideal to avoid interruptions by setting up the props for all the poses in advance, but if this is not practical, set up the props for two or three poses in a row, practice, then set up two or three more. Go back and forth between poses to better compare differences if you like.

There’s no need to try to figure out what is happening physiologically during this practice, just notice how things feel. We’ll analyze later.

Keep the instructions handy; refer to them frequently as you go along.

22 The Light | Fall 2022 ON ASANA CONTINUED

Observation Instructions for Practice Demo Round 2

1. Tadasana

Notice whether you experience these sensations:

• elevated blood pressure in your feet and ankles;

• no particular blood pressure sensation in your heart, upper chest, neck, head, face, nasal passages/sinuses, or eyes;

• an alert mental state.

2. Supported Savasana

First, notice whether your nasal passages are clear, making it easier to breathe through your nose, and whether you feel reduced pressure in your sinuses.

Next, notice whether the sensation of pressure or fullness in your heart and upper chest are higher than they were in Tadasana.

Finally, notice what pressure, if any, you feel in your feet compared to Tadasana

3. Savasana

Notice whether you feel an even distribution of pressure or fullness from your feet to your head, or perhaps a very slightly uneven distribution directing a bit more pressure and fullness toward your chest and head.

Notice whether your nostrils are less clear than in supported Savasana.

4. Supported Urdhva Padasana

Notice whether you feel:

• a sense of blood draining from the feet — a distinct drop in pressure — compared to Savasana;

• moderately elevated pressure in the rest of your body, distributed evenly from pelvis to head.

5. Viparita Karani

As you move directly from Urdhva Padasana to Viparita Karani, notice whether you feel:

• increased pressure or fullness in the area of your heart, which then spreads to your upper chest, neck, face/head, and arms;

• a distinct further drop in pressure in your feet.

Now try this first experiment while still in Viparita Karani

• disturb the alignment of the pose by dropping your chest and laying your upper back on the floor (untucking your shoulder blades), then notice whether you feel a fall in pressure in your upper chest and neck;

• return to the proper Viparita Karani alignment of lifting and opening your chest, lifting the lower tips of the shoulder blades high off the floor and pressing them into your back, and maximally rolling the tops of your shoulders far underneath you; notice whether you feel a restoration of pressure in your upper chest and neck.

5.5 Now try this second experiment while still in Viparita Karani

• elevate your head by placing a rather thick folded blanket under it, and notice whether this reduces pressure in your head and face, and/or reduces nasal congestion;

• remove the head support so your head is back on the floor, and notice whether this restores pressure to your head, face, and nasal passages.

Notice whether Viparita Karani feels especially relaxing.

6. Salamba Sarvangasana

As you move from Viparita Karani to Salamba Sarvangasana, notice whether you feel:

• a very strong increase in blood pressure focused especially in your upper chest;

• a strong increase in blood pressure in your neck, head, and face;

• a large further drop in blood pressure in the feet, legs, and pelvis compared to Viparita Karani;

• a more active brain, compared to Viparita Karani.

7. Salamba Sirsasana I

When you change from Salamba Sarvangasana to Salamba Sirsasana I, notice whether you feel:

• a distinct shift of blood pressure to the head itself, especially strong in regions nearest the floor (for example, the top of head, forehead, eyes);

• possibly less pressure in the neck and upper chest compared to Salamba Sarvangasana, but still high pressure there;

• either strong clogging or strong clearing of the nose and sinuses;

• similar or lower in pressure in the feet, legs, and pelvis compared to Salamba Sarvangasana;

• a more active brain, compared to Salamba Sarvangasana

8. Repeat the same sequence in reverse order

9. After the final Tadasana, lie flat in Savasana again until you feel ready to move.

The Light | Fall 2022 23

WHAT IS (PROBABLY) HAPPENING IN THE POSTURES

Here are proposed explanations of some of the things that may happen in each posture. They are grounded in science, but only a few of them are based on direct experimental measurements in yoga asanas. There are no fixed practice instructions for this section, but it’s extremely useful to revisit some of the poses as you read along.

1. Tadasana

Why there may be a feeling of pressure in the feet and ankles in Tadasana

The vertical distance from the heart to the feet is maximal in Tadasana, so gravity creates a very strong increase in arterial pressure as blood travels down the descending aorta through the leg arteries to the feet.

For example, one study found that in people who are standing up, arterial blood pressure measured at the ankle averaged 222/142 mm Hg, while arterial blood pressure measured at the arm averaged 129/79 mm Hg.5 Over time, this high pressure in the lower legs and feet can push excess fluid out of the capillaries into the interstitial space, causing swelling.

Meanwhile, the great vertical distance between the heart and the feet in Tadasana also increases downward pressure in the venous system. This makes it harder for the veins and lymph vessels to collect fluid from the interstitial space and send it upward toward the heart. In addition, the downward pressure causes the veins to expand, so a large volume of blood pools in the venous system of the legs and feet. You may see veins in your feet become distended in this pose.

All the factors above may contribute to a feeling of pressure in the feet in Tadasana

Why there may not be any marked feeling of low pressure or fullness in the heart, upper chest, neck, head, face, nasal passages/sinuses, or eyes in Tadasana

The circulatory system has several mechanisms for moving blood upward against gravity while standing.

Let’s look separately at moving venous blood up from the feet to the heart and pushing arterial blood up from the heart to the head.

When we stand upright, pooling of venous blood and interstitial fluid in the abdomen, pelvis and legs effectively removes about 10–20% of our total blood volume from circulation.6 This reduces the amount of venous blood available to fill the heart from below via the inferior vena cava. However, in Tadasana, strong action of the leg muscles squeezing the leg veins, plus constriction of smooth muscle in the walls of some leg veins, aided by one-way valves, helps push a sufficient amount of venous blood up through the legs to increase blood volume in the abdomen. There, strong breathing takes over to help draw a sufficient amount of venous blood upward through the inferior vena cava into the heart to achieve partial filling. Meanwhile, since the head, neck, and upper chest are above the heart in Tadasana, gravity assists the return of venous blood from these regions to the heart via the superior vena cava. This partially offsets the reduced venous-filling pressure from below, so although heart-filling pressure and volume are likely to be somewhat low in Tadasana compared to other poses, it is high enough for us to function normally. This may be partly why there is no marked feeling of low pressure in the heart in this pose. (The pressure is, in fact, somewhat low, but our body can deal with it, so it feels normal.)

In Tadasana, the head is as far above the heart as it can be, so the heart has to work extra hard to pump arterial blood upward with sufficient pressure to supply the head, especially the brain. When we move from lying down to standing, there is an immediate, large fall in blood pressure in the aortic arch and carotid artery, and this quickly triggers strong high-pressure baroreflexes. These increase the pressure of blood being pumped upward out of the heart to the upper chest, neck, head, face, nasal passages, sinuses, and eyes, partially or completely offsetting the tendency of gravity to lower pressure in these locations. This is the main reason that there is no marked feeling of low pressure in regions above the heart in Tadasana.

Why you may feel an alert mental state in Tadasana

The same baroreceptors that activate your cardiovascular system also activate your brain.