Editor-HelenAbbott

Design-KeriannO'Rourke

AssistantDesign-AnnaNorriss

Proofreader-JanetSchorer

Proofreader-EmilyJaneGrant

Advertising-TomScott

ISTA

LakesideOffices

TheOldCattleMarket

CoronationPark

Helston,Cornwall

TR130SR

UnitedKingdom

office@ista.co.uk

SUBSCRIPTIONS

DigitalcopiesofSceneare availablethroughtheISTAShop. www.ista.co.uk

To receive member benefits and more

year.Formostofus,theworstofthe pandemichaspassedandIhopeyoufeel optimistic,enthusiasticandexcitedabout thepotentialofwhat’stocome.

‘Excited’ is a word you will have heard ISTA staff use again and again recently because it best describes how we feel! We have had such a busy few months creating, developing and refining much of what we do and Scene has not escaped that. So, it is with immense pleasure and anticipation that we launch this issue, the first of our new look theatre journal.

As editor, I would like to extend a very warm welcome to you all - regular readers and new We are thrilled to bring you features and articles written by a truly impressive collection of artists and educators.

This issue is focussed on exploring the world through theatre. Topics covered include Verbatim Theatre; arts in criminal justice; theatre and wellbeing; storytelling; and theatre in challenging environments.

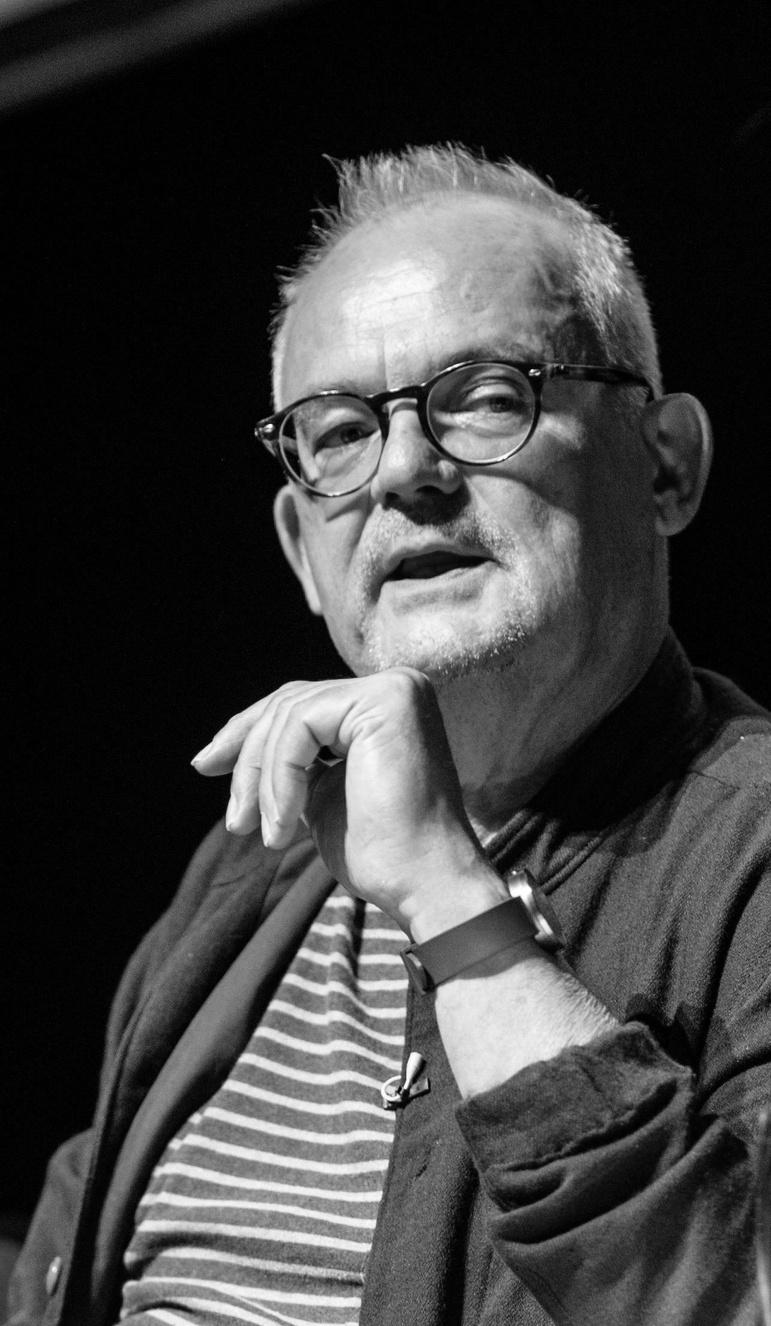

We also have units of work, case studies, profiles and an interview with ISTA Patron and Professor of Creative Education at the University of Warwick, Jonothan Neelands.

I take this opportunity to thank our contributors, all of whom have volunteered their time and expertise. I see such a bright future for Scene and believe, with your support, it can continue to educate and inspire the theatre community over the coming years. I am excited (thrilled, exhilarated, elevated, animated, enlivened, electrified, stirred, moved, delighted…) for you to read this September issue! Please, as always, stay in touchyou are welcome to contact me at helen@ista.co.uk with your thoughts, suggestions or ideas.

HelenAbbott Editor

Editor

The International Schools Theatre Association (ISTA) specialises in global learning through theatre.

We are a UK based charity, founded in 1978, providing transformative learning experiences for educators and young people worldwide. We create communities of learning, working closely with over 240 member schools around the world and we are the International Baccalaureate’s exclusive global provider of teacher training for Diploma Theatre.

We believe in the unique power of theatre and the arts to connect, develop, transform and empower people to become active members and change makers in their own communities and the world.

Clickanyofthelinksbelowformoreinformation.

#aworldofdifference

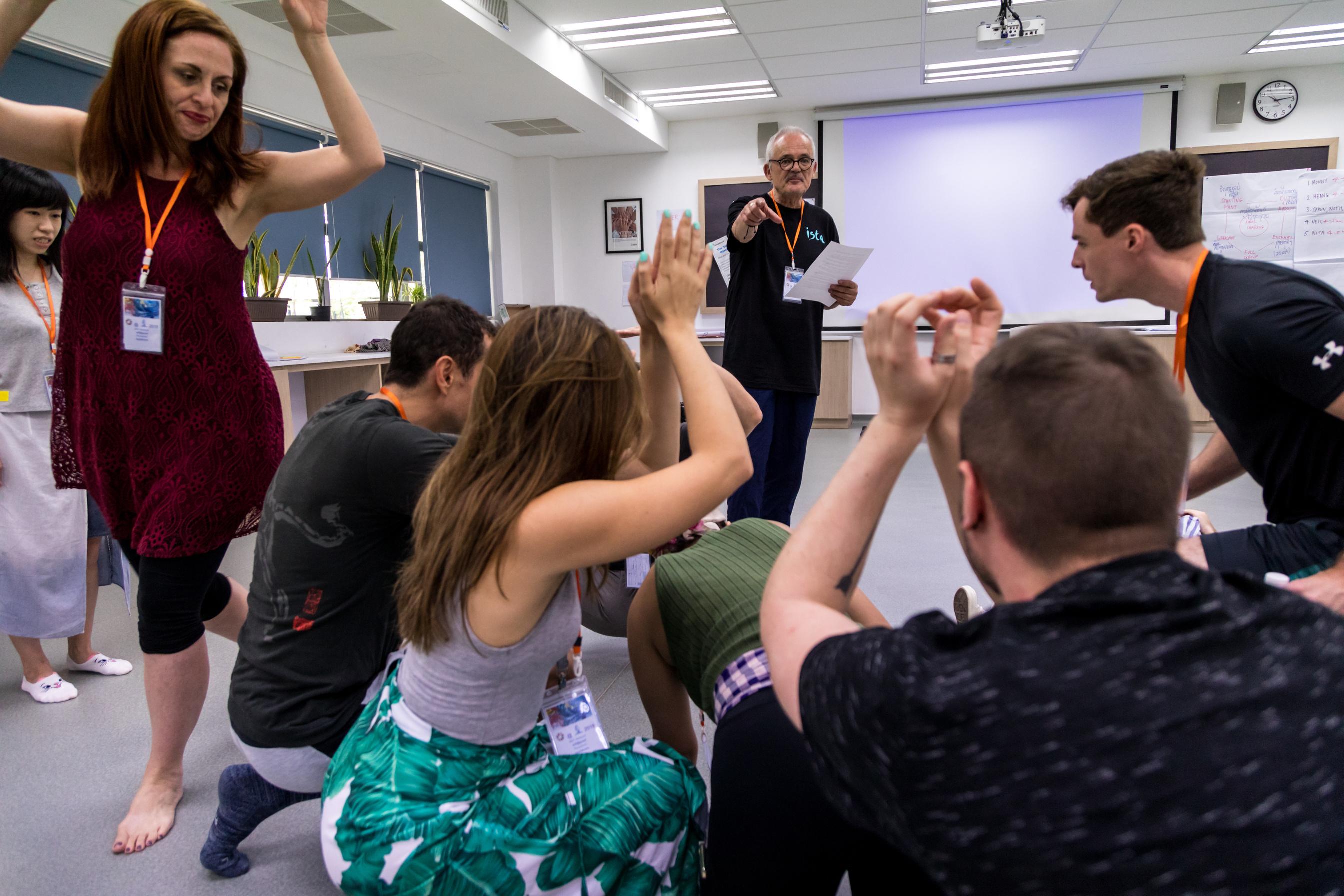

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT &LEARNING (PD&L)

ARTISTIN RESIDENCY (AIR)

ISTA is an organisation that prides itself on being current, relevant and a provider of high-quality learning experiences. Its focus and one constant over the years has been to work in an international context with a commitment to the role theatre plays in developing internationally minded, responsible young people who will contribute actively to the creation of a better world. Until relatively recently, ISTA considered itself primarily as a producer of high-quality events which engaged international students and educators with learning through and about theatre. The nature and make-up of these events have developed over time, as has ISTA, in response to the dramatic events that have shaped the world over the past two years. As well as this, ISTA has taken into consideration the new thinking regarding international education, new developments in theatre because of the digital and the impact the pandemic has had on young people.

As well as events, ISTA has now classified the range of its learning experiences under the following categories:

Events – These are experiences which are time-limited and with a particular focus (Festivals, TAPS, Professional Development and Learning, IB DP Theatre Teacher Training)

Services - These are bespoke experiences and developed with educational settings and cultural organisations based on their needs (Artist in Residencies, Mentoring, Consultancies)

Programmes and projects - These are long-term initiatives as well as time-limited projects involving more than one encounter (ISTA ACADEMY, Global Digital production)

Resources – These are designed to support global teaching and learning through theatre and the related arts (the ISTA journal Scene, free teaching and learning resources, publications, and instructional guides)

Partnerships – These are initiatives developed with organisations and often engaging with communities beyond international schools: (working with Amala on a project with refugee and displaced young people, sites of learning such as Terezin and the 9/11 Memorial and Museum, working with disabled young people with UCAN Productions)

TheISTA™EnsembleMethod underpinsallISTAworkandis designedtobringpeople togetherthroughtheatreand therelatedartstoform communitiesoflearningthat leadtocollaboration, connection,andempowerment.

ISTA prides itself on being one of the main providers of international artist-educators who are experts in particular theatre traditions and practices Global learning through theatre means offering young people and teachers the opportunity to engage with unfamiliar theatre practices that will broaden their understanding of theatre as well as build international mindedness. This is achieved by bringing together practising artists who have a specialism in a particular practice with learners and educators in different settings as well as offering virtual opportunities for young people or educators who are unable to travel Global learning through theatre also encourages learners to consider the role that theatre plays in different cultures, its origins and roots and the way theatre develops and changes in response to cultural, social, and economic factors. This area of ISTA’s work is also a celebration of the diversity not only of theatre in the world but also of artists. Creating opportunities for cross-border working and interconnection, ISTA also encourages dialogue and collaboration, building networks of artists who bring their own particular skill sets and cultural perspectives together to create theatre experiences that are international and rich.

This strand of ISTA’s work relates to everything we do regarding theatre as an art form and theatre-making. Working with an international pool of theatre practitioners and artist educators who inform the development of all ISTA strands, this area is about developing understandings and skills associated with performing, devising, directing, designing and other related arts such as film, music and dance. This also encourages us to work with international arts organisations that are current and relevant. ISTA’s partnership with the International Baccalaureate as the exclusive trainer of Diploma theatre teachers means that we have contributed and continue to be involved in the shaping and the development of international theatre education; providing training, experiences and resources for young people and educators in schools around the world. This brings together contemporary practice in the world of theatre with up-to-date international educational pedagogy and, of course, the ISTA™ Ensemble Method in all things related to theatre as an art form and theatre practice.

All ISTA’s work is guided by and categorised by the followingstrands.Thesehavehelpedtheorganisation to redefine and focus its work, helping the creation, designandenhancementofitsexperiences:

This area of ISTA’s work focuses on using theatre as a tool for exploring the world. This includes inquiring into social and global issues, examining ISTA’s own communities and those of others as well as the interconnected nature of our world. The purpose of this work is to use the ISTA™ Ensemble Method to give young people a deep understanding of concepts that are key to them as global citizens and the capacity and skills to present their understandings and ideas through theatre. Intercultural awareness and the building of compassionate communities of learning are also key to this area of the work. Central to the exploration of the world through theatre, through ISTA™ Ensemble Method, are pathways to empowerment and action, where learners consider how their ISTA experiences will inform their future development and relationship to their local and to global worlds.

Festivals are the main area where we deliver this area of ISTA work. Each year ISTA selects a global challenge which becomes the focus for the year. This global challenge is designed to be an area of global significance which offers a range of possibilities for exploration. ISTA’s global challenge for 2022-23 A world of difference provides a lens which engages young people with opportunities to explore the world through theatre.

This ISTA challenge offers host schools and artists an imaginative and meaningful inspiration which; can be interpreted broadly, is accessible and has relevance to both the host community and to the world.

The possible areas of learning for festivals and events this year, for example, are:

The post-pandemic world and its challenges for young people

The changes in our communities

Diversity, equity, and inclusion

Social justice

The environment

Making a difference/ changing the world

What it means to be or feel different

A celebration of difference and identities

The arts and how they make a difference

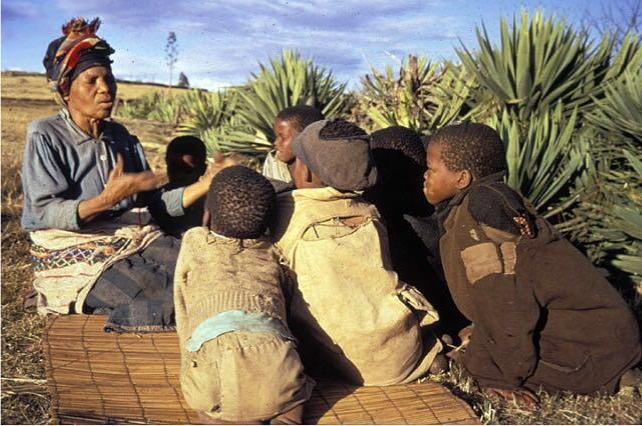

A story-based inquiry approach to ISTA’s global learning through theatre and the related arts approach engages young people with stories from around the world and allows them to connect with different cultures, concepts, and narratives.

‘Thefourstrands,thoughindividualandrelatedto particularendeavoursandinitiatives,alsocome together,theoneaddingdepthtotheother.’

Fundamental to ISTA’s mission is the use of the ISTA™ Ensemble Method to bring people from different places together to collaborate, create communities of learning and celebrate our differences as well as our shared humanity. Using theatre and the related arts, learners also explore the interconnected nature of the world, our communities, ourselves and both the benefits and challenges of this interconnection. Fundamental to these experiences and one of their key features is that learners develop new connections, and friendships and become part of the international creative networks we create. The characteristics of the global learner which ISTA aims to develop, relate not only to learning but also to the learner’s growth and flourishing as human beings and as citizens of the world. The development of the global learner is central to all ISTA’s work and every experience is designed carefully with this in mind.

The four strands, though individual and related to particular endeavours and initiatives, also come together, the one adding depth to the other. They provide focus as well as provide ways to enrich ISTA experiences, ensuring that ISTA brings together theatre, deep learning, and responsible citizenship, making it a leading provider of global learning through theatre and the related arts. ◾

In this section ISTA profiles one of its partners, their work and the nature of the partnership.

ISTA is proud to be partnering with Amala education; an organisation established in 2017 with a bold aim to provide alternative upper secondary education to young refugees and crisisaffected young people aged 16-25 who often face insurmountable obstacles to accessing education. By providing highquality education, Amala wants to enable refugee and conflict-affected youth to improve their own lives, participate in society and drive wider societal change.

Access to education is vital for the full development of human and societal potential; yet for millions of adolescent and young refugees amongst the world’s growing refugee population, education remains a distant dream.

Globally, there are now more than 80 million people who are displaced, and crises are increasingly protracted, leading many people to spend years if not decades in displacement.

Furthermore, ongoing conflicts and the impact of climate change mean that the number of people who are forcibly displaced is predicted to rise to hundreds of millions by 2050.

34%

One-third of refugees are enrolled in secondary education, compared to the global rate of 84 per cent.

Only five percent of refugees reach higher education compared to the thirty-seven percent global higher education access rate.

Amala (formerly known as Sky School) was conceived in 2017 in response to the gap in quality education provision for displaced youth. The name is inspired by the Arabic word for hope, which their education embodies. Amala believes that young refugees - like all people - have a right to quality education. Their mission is to use the power of education to transform the lives of refugees, their communities and the world...

In 2016, Amala co-founders Mia and Polly were working on a prestigious scholarship; the programme admitted refugees to schools around the world to complete their upper secondary education. They found that for every scholarship place available, hundreds of promising applicants were turned away.

Images: Sourced from Amala website www.amalaeducation.org

Their subsequent research showed that there were few educational opportunities available for refugee youth aged 16-25, many of whom are forced to drop out of educational systems due to the barriers they face. The idea for Amala was born: to provide transformational learning programmes for displaced youth and their host communities to improve their lives today and open up opportunities for the future.

Amala has two main programmes: the Amala High School Diploma, the first high school diploma designed for and with refugee youth and the 10-week Changemaker Courses in areas such as Peace-building, Ethical Leadership and Social Entrepreneurship.

Amala supports students to access further opportunities for education, training and work beyond their studies. Amala learning focuses on the development of learner agency as well as competencies that enable learners to make changes in their lives and communities. Amala learning is delivered through a blended learning model and in light of Covid-19, many courses have been adapted to an online model Amala programmes are delivered both directly by Amala and in collaboration with partners whose missions are aligned with their own. Through collaborating with partners they have been able to bring transformational education to

refugees in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Europe and Latin America.

This programme is the first international high school diploma designed with and for refugee youth. The High School Diploma is an alternative pathway to completing upper secondary education (high school) for youth aged 16-25 who are out of school and who wish to access a holistic opportunity that focuses on the development of competencies to improve their communities and the world. The Amala High School Diploma has been launched in Amman, Jordan and Kakuma, Kenya. This year Amala is launching its third cohort of the programme in Kakuma and the fourth cohort in Amman.

Amala Changemaker Courses enable refugee and crisis-affected youth to develop their sense of agency for positive change in specific areas including “Peacebuilding”, “Social Entrepreneurship” and “Ethical Leadership.” Changemaker Courses develop life skills and can support integration and participation in communities, economies, and societies.

Amala's target demographic is young refugees and crisis-affected youth aged 16 - 25. The Amala High School Diploma is particularly targeted at youth who are unable or not eligible or able to access the national education systems of the countries where they are living due to

language barriers, age limitations or family and work commitments. The programme is free of charge for students. Through the power of education, Amala enables refugee and crisis-affected youth to unleash their potential and improve their lives and communities and to drive systemic change through participation and influence.

85% of Amala short course alumni are enrolled in education six months after finishing an Amala programme including higher education, vocational training, language classes and informal education programmes.

An Amala education not only supports individual growth but also on students developing their capacity to create new value in their communities. 44% of alumni are leading, working or volunteering on entrepreneurial initiatives and social projects six months after graduating.

Some continue to work on social impact projects they have started during their studies, others are volunteering to teach others English and Arabic, while others are contributing to peace-building initiatives in the community.

Increasingly, Amala students and alumni are influencing wider systems on youth and education matters, impacting the lives of many other young people around the world. Alumni are serving as representatives on bodies and forums that inform policy around refugee education, as well as advocating for refugees and disadvantaged youth to access high-quality education, entrepreneurial, and job opportunities. Current students are also taking part in forums to shape global education policy. Read more about Amala’s students and what they have gone on to do after completing an Amala programme here

‘Globally,therearenowmore than80millionpeoplewhoare displaced,andcrisesare increasinglyprotracted,leading manypeopletospendyearsif notdecadesindisplacement.’

ISTA is partnering with Amala to run a two-day workshop with current Amala High School Diploma students and alumni (18-25) in Amala’s Amman centre in Jordan. The workshop, Staging our stories, changing the world, will focus on using the ISTA Ensemble Method as an approach to community building and the staging of personal stories as a form of advocacy and as a catalyst for change.

Working with young refugees and displaced young people is an exciting new departure for ISTA; providing the organisation with the opportunity to develop its work and extend the reach of the ISTA Ensemble Method beyond its current communities. Telling your own story as well as sharing stories across cultures using theatre and the arts is a key feature of ISTA’s global learning methodology and mission.

Engaging young people with the process of selecting, structuring and finding ways of communicating their own individual stories and experiences, though sometimes difficult, is empowering and affirming. Sometimes words alone are not enough Theatre and the arts provide us with many more possibilities to express our experiences and share our stories. The collective sharing of stories has, through the ages, been an effective tool for community building and celebration. In our current times, ISTA believes that stories can also be a tool for intercultural connection, understanding and change.

Listening to and connecting with the stories of others, experiences beyond our own, builds compassion and is an effective advocacy tool.

Together with this workshop, ISTA is also offering this unique professional development and learning experience for educators and artists interested in theatre as a tool for change Working alongside ISTA trainers and Amala facilitators, a three-day training, working with young people, will provide artist-educators with new skills and approaches to apply to their own work both in and beyond their own context.

Through values-led partnerships, ISTA works in collaboration with other organisations that share its mission and philosophy, to bring about change and make the world a better place through global learning.

‘Throughvalues-led partnerships,ISTAworks incollaborationwith otherorganisationsthat shareitsmissionand philosophy,tobring aboutchangeandmake theworldabetterplace throughgloballearning.’

Helen: You are Patron of ISTA and Professor of Creative Education at the University of Warwick. Can you explain what is meant by ‘creative education’?

Jonothan: Before I was Professor of Creative Education at the University of Warwick, I was Professor of Drama and Theatre Education. For a number of reasons we moved into the business school and the move to become Professor of Creative Education broadened out from the theatre and drama work. Theatre and drama still remained, however, very much at its core.

I still take a theatre and drama view of what we mean by ‘creative’ and what we mean by creative education. It's all the things that this issue of Scene is about. It's giving young people of whatever age the means to look at, question, challenge

and reimagine the way the world might be. It’s a way of feeding the imagination, which is the core of creativity. Unless you imagine and have ideas for how things might be, you're not going to make anything that is different or anything that makes a contribution. In the business education context, that's obviously very important. We have young leaders going out there into a world that can't carry on the way it is, whether in business or in any other sphere of life. We urgently need to rethink. We urgently need new ideas to make sure that we protect the planet, that we find a more fair and equal distribution of the resources that we have.

And crucially, this comes from theatre. Theatre develops a high sense of empathic understanding of others and the way that others see the world differently from ourselves. In the context of a business school it's critical that future business leaders are not making decisions that don't take into account the consequences of those decisions on people's lives, whether they're employees or whether they're beneficiaries from the business. It's absolutely essential.

Having your imagination nourished, stimulated and encouraged. Having confidence in it. What does that become? What does that mean? What might that produce that would help make a difference to people's lives or to the world? It's the very broad view of creative education I have. And creative education doesn't belong to the arts. It belongs in all disciplines. It belongs in all walks of life, it belongs in every field.

Helen: In the business world are the benefits of creative education and creative learning happily accepted or do you come across resistance?

It's to do with moving students away from passively receiving knowledge to actively engaging with knowledge, which is what we're able to do through drama and theatre. In drama and theatre, the world is not an abstract. It's not a curriculum on a board. It's something that we experience and live through and take roles in and reimagine. So for all of those reasons, that's why I'm Professor of Creative Education but it's deliberately broad. One of the interesting things about creativity is that it's a very slippery concept. Nobody can define it exactly and say what it is and I think it’s quite useful for it to be slippery in that way. But at its heart is imagining and turning those imaginings into ideas that can be turned into something, whether it's a product, a service or a piece of art.

Jonothan: Yes, I think so. But in universities or schools, the pressures on a curriculum that can be measured easily, that can be consistently applied across every classroom - that is increasingly about acquiring knowledge rather than making knowledge, are huge. So to persuade people, not so much students but other faculty as to why you would spend time doing work which is not that precise or clear in its objectives, that is probably not going to be that precise or clear in how you measure it, can be difficult. But the big major businesses absolutely understand that we can't just carry on as we have done. We do need to find new ways of doing things, new ways of working, new ways of using resources. So in that sense there’s a very open mind about it. The struggle though, is to find curriculum time and navigate the pressures on students, like student loans for example.

Ourdramaand theatreexperiences connectusto peopleinwaysthat areunique.’

If you want to become an accountant you're going to choose an accountancy course. Persuading a student why they might put a creative course into that mix can sometimes be difficult. But it will tend to attract a certain kind of student who's maybe got more of a social responsibility, more of a questioning mind, who may have benefited in the past from a strong arts education.

Many of the students in the business school do come from independent schools, which sadly, tend to have more opportunities than some of our state schools. It's difficult. Drama and theatre are never going to be completely embraced, that's what you buy into when you come into this field. Knowing that you're always likely to be on the margins but that’s the core of everything that we do and everything that we learn. It's always going to be a resistance movement. It's not always going to persuade everyone about its benefits. But that's what we do. That's what we're used to.

Helen: Staying with education, we hear and use the term ‘global learner’ a lot. What is global learning though and how can theatre contribute to it?

Jonothan: I think global learning is that we understand that we are not alone, that we share a planet with others who are from a multitude of different cultures, different backgrounds, different levels of deprivation and prosperity, different ideas about what the future looks like, different ideologies. And you can isolate

yourself from all of that or you can engage with it. One of the powerful ways of engaging with others is through stories because what any story will do is engage you at a feeling level as well as at a thinking level. The importance of theatre and drama is that those stories are not read off the page or listened to in the classroom, they're active, they're made real. So we can feel and think what it might be like to be in a story that's from an entirely different culture. We can think and feel what it might be like to be in a situation of need that's not one that we've actually experienced but is one which we can connect to through empathy and emotion. The core reason for drama and theatre is to show us how we live and how we might live better together. And that's got to be in a global sense. It's got to be for the world rather than just how does that affect me? How does that affect my classroom? How does that affect my friends? It's got to be a broader, more universal view.

Our drama and theatre experiences connect us to people in ways that are unique. They allow us to explore and feel and imagine. That's why as children, we love picture storybooks, why we love to be taken out of ourselves, to be taken out of our immediate environment, to be taken into other lands, to be taken back in history, to look forward to what the future might look like. That's something we know instinctively as children that we need and want to engage with. So drama and theatre is a way of continuing that fascination with a deep desire to know more on a personal human level, not just in terms of facts and figures such as how many people live here and how many people live there and what's the birth/death rate. But what does it actually feel like to be somebody who's in a different place or a different time?

Helen: In this issue of Scene we're talking specifically about how theatre can be used to explore the world. You've touched upon this already but can you talk a little bit more about how theatre, beyond the study of theatre traditions and styles, can impact the world and its potential to bring about real change?

Jonothan: One of the really great things about ISTA is that it encourages students to look at theatre traditions and cultures from across the world.

But underneath all of that there is the western tradition of theatre and that western tradition of theatre, we generally agree, started in fifth century BCE Athens

and was the first invention of democracy. Before the arts, before anything else.

We know from archaeological digs there were small theatres in the communities around Athens before the Acropolis or anything else. It was, from the earliest time, not seen as entertainment but seen as a way of people coming together to see how they live and to think about how they might live better together. There's a political coming together, a political way of being critical of how we are and being critical about how we might change and how we might become different. So I think that’s theatre’s chief role - to nourish and encourage democratic values and a democratic mindset. I think the ‘doing’ of theatre and the watching of theatre does that.

What we've not talked about is the coming together to make theatre and the

‘Havingyour imagination nourished,stimulated andencouraged. Havingconfidencein it.Whatdoesthat become?Whatdoes thatmean?What mightthatproduce thatwouldhelpmake adifferencetopeople's livesortotheworld?’

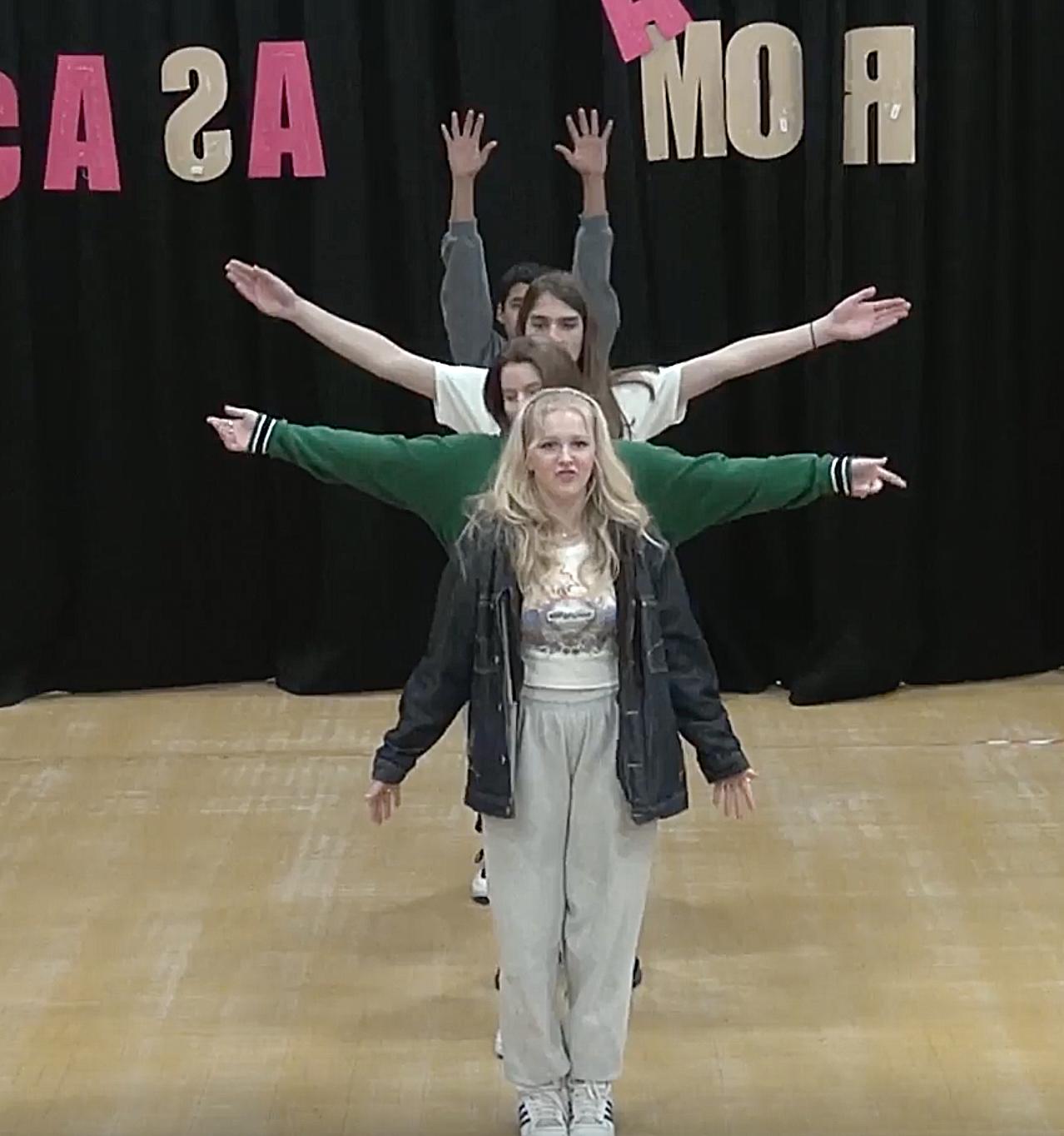

creation of ensemble, which is an essentially democratic process It's about people coming together, it's about putting the common interest above one's self interest. And all of these things, young people learn through becoming a theatre ensemble. To be themselves but be themselves mindful of others and to be themselves working towards some common good which only a group of people can achieve together. And that sums up what democracy is. So any coming together of young people to form an ensemble to make a piece of work together is essentially a politically democratic process. In helping young people to become dramatic actors, we're also helping them to become effective social actors, gaining confidence, losing your selfconsciousness, finding your voice

These are not just restricted to the drama studio or the theatre. It's about taking that out into the world and looking at how you can be an activist in the world, looking at how you can use your skills to support other movements, other ideas of the group, other projects that will better the environment, better people's lives, better the world. So that's what really makes it different from any other art form, I think,

‘Beingpartofthat process,ofensemble building,isformea coredemocratic processwhichis absolutelyvitaland increasinglyneeded.‘

because it uses human beings in space and time to tell its stories.

Being part of that process, of ensemble building, is for me a core democratic process which is absolutely vital and increasingly needed And at the heart of that is empathy.

Not sympathy, not giving everybody a hug but empathy - understanding that people have different points of view which you may not agree with but you must work with and understand In that commitment we minimise the weaknesses and maximise the strengths of who we are. We recognise that some of us are better at this than they are there and vice versa. And instead of criticising and complaining we will work together as a team When we come forward as an ensemble there's not a sense of weaker or stronger players. There’s a sense that this is a strong ensemble that has all the skills, all the aptitudes, all the capabilities that it needsthat's what makes it successful People have worked through those difficult interpersonal relationships and interpersonal differences in order to achieve strength together. We become the fist, the fist of change.

Helen: You mentioned ISTA there and talked about the power of the ensemble. Can you expand on what role ISTA plays in exploring the world through theatre?

Jonothan: I think it's becoming essential I think it's really important that ISTA’s broadening its appeal, welcoming a wider community of teachers and young people. It’s important because the world in which

we live, in many countries, drama and theatre, particularly in education, are not as strong as they might once have been. But everywhere there are pockets of people who understand. They may feel largely unsupported now because they might not have a national or even international association anymore. And ISTA has an offering to fill that gap because it's strong and it's stable and it's got a clear sense of what its future should be. So I think it's really important to become the international voice of a particular model of drama and theatre education, which is absolutely rooted in the ensemble but also absolutely rooted in internationalism. One thing that ISTA offers which is very difficult for teachers outside of the independent sector, is to get that knowledge and understanding of other theatre forms, that knowledge and understanding of other theatre forms, that knowledge and understanding of how you build and make Ensemble. Once we get back to festivals and live work and we grow that locally and nationally, as well as internationally, we're offering students a unique opportunity to come together with people who are from different places, from different backgrounds, to work together again, democratically To understand and be enriched by having been with people who are different or see the world differently or have different abilities. I think there's an exciting opportunity for us to gather together theatre and drama educators who may be feeling a bit isolated now and to give them a strong voice and to give them guidance and to give them help and to give them support. ◾

I grew up at the end of the Cold War in the US, meaning I grew up with only what I was told about the USSR. In the mid1990s, I was on a night train from Kyiv to Donetsk. I met a charming couple, Oleg and Masha. We stayed up all night, playing cards and drinking tea. It was my own first personal ‘glasnost’ as the pictures they painted of their lives growing up in Ukraine were vastly different from the ideas I had adopted. I needed to hear their story and their truth to begin to understand a life different from mine. Looking back, I can see how that was my first experience into the beginning stages of Verbatim Theatre.

WithintwentyminutesIwas transformedinaroomof strangersaswecollected storiesfromeachotherand builtmeaningfultheatrebased uponeachother’struths.

My journey into Verbatim or Documentary Theatre started with the role of spectator. I was captivated by Anna Deveare Smith’s Fires in the Mirror and Little Revolution by Alecky Blythe. Some years later during an ISTA Connect Festival, I met Dinos

Aristidou and was intrigued by what could be done with students and verbatim. Dinos taught a workshop for teachers using his ‘Reflection Pack’. Within twenty minutes I was transformed in a room of strangers as we collected stories from each other and built meaningful theatre based upon each other’s truths.

Skip ahead a few more years as I kept rethinking and reinventing how to be a better guide to a new generation of theatre makers in a post pandemic world. I had taken another workshop with Dinos specific to the ‘Hear Us Out’” Verbatim method. (This was highlighted in ISTA’s 2021 global production, Diary of an Extraordinary Year). After this workshop, I knew this was an experience that I wanted to give my students.

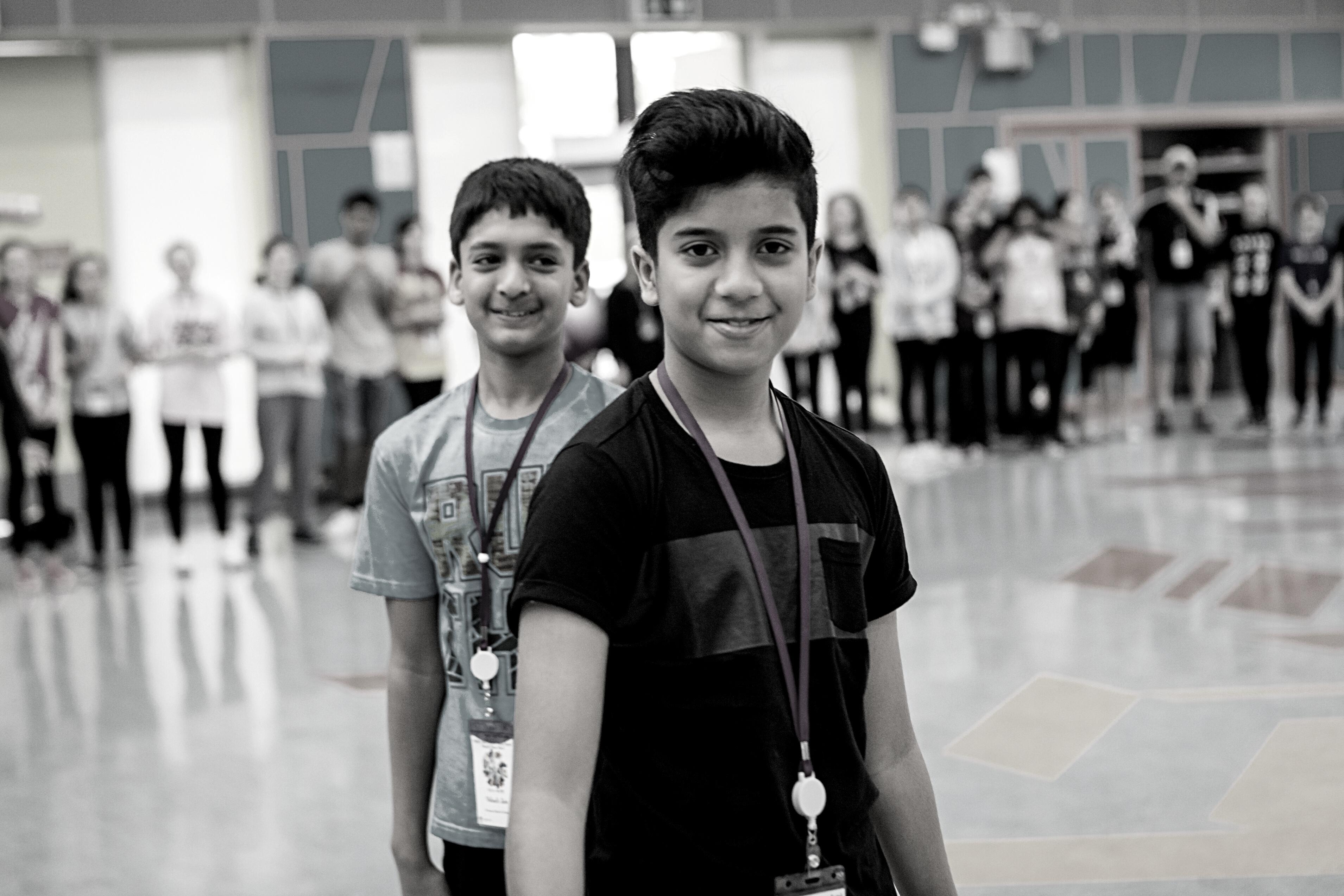

I applied for and received a grant, coordinated with ISTA and decided that my MYP Drama 5 class was ideal as it would set them up for IBDP and allow them time to create, collaborate and process. What did I actually want my students to accomplish? I wanted to introduce them to a new way of creating theatre that would allow them to engage in the world around them with a different perspective.

The overall concept for our project/production was 9/11. 2021 was the 20 year anniversary of September 11 and this event was something that this group of students could all access stories about from people they knew.

My students prioritised the concept of INTENTION of dignity and respect. This included that they were sure to get written permission from the storytellers.

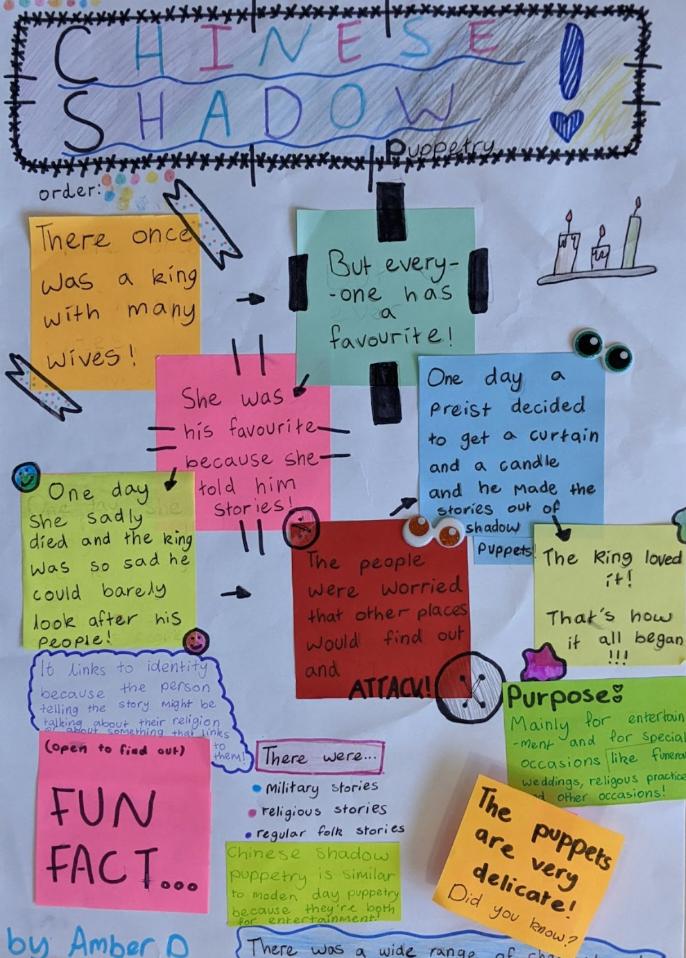

In October of 2021 my students began their online workshop. Dinos Aristidou guided my students through the process of creating Verbatim Theatre This process was beautifully scaffolded. One of their favourite starting points was an exercise that involved students working with partners. They were to choose a special picture from their phone and tell the story. Dinos guided them through the ideas of story collecting versus merely conducting interviews

Below: Photo from the production‘NowthatIhave manyofthese samestudents asGrade11s,I seethegrowth theyhavemade asperformers, designersand overall,growth ashumans.’

and to work through the prompts of open ended statements rather than questions.

Dinos worked the students through creating prompts so they could begin to collect their stories. We settled on six prompts. The fairest way to assign prompts for story collecting was just to draw from a hat.

Once we had prompts and a loose plan, every student chose 2 people to talk to and get their 9/11 story. To prepare students for this experience I provided basic dramaturgy into September 11, 2001. We watched old newscasts together and I laid out original newspapers and magazines from that week, gallery style, for students to be able to read. We gained the appropriate permissions from the storytellers and then practised focused listening without judgement and showing respect.

The students had a week to record their stories. We listened to every single recording in class as a group with students taking notes. Personally, this was my favourite part. We discussed every story one at a time.

My theatre makers came up with ideas for imagery specially tailored to performance and production. They were also able to make connections that were not always obvious, such as ways to overlap stories and add characters that were mentioned while retaining full integrity of the storyteller’s truth by not changing any of the original wording.

The interviewers transcribed all the interviews and were instructed to find a 1 to 2 minute cut that they found the most poignant The students chose to memorise the written transcripts and not use the headphones, as we would be performing live and in an intimate space.

Once I had all the monologues I randomly assigned a student to work with a piece that was not their own. Students worked in groups according to their given prompts.

This production was almost entirely student designed. I served mostly as a consultant. Some stories were straight out monologues, some stories were combined to create dialogue or a round-robin type story. Students chose staging, physical blocking, costumes, lighting and sound. By the time of the opening this ensemble had created a stunning and poignant piece of theatre.

We started with a small audience in order to get some feedback. This was written feedback (Google Forms). We went through the notes and the students made adjustments to be more clear. Most of theadjustments had to do with timing and spacing, making sure to take pauses and

Iseethegrowth theyhavemade asperformers.

keeping with transition music. The transition soundtrack focused on 90s music including ‘Carry On’ by Fun. It was unanimous and almost unspoken that this would be the title of the piece, Carry On.

The intention of this ensemble was to remind their audience of the daily humanity behind a life altering event that went beyond what the news reported. Their intent was quietly powerful and effective. This was evident on the day of the show, as many of the storytellers came, as well as audience members who were of the age to have their own firsthand memories of 9/11. There were many tears and the audience lingered for a long time after the house lights came on to talk to the actors, to talk to each other. To talk and to listen. For after all, that is the point.

This particular project finished in May of 2022. This entire process took place on and off over a year and honestly off and on, as we worked through different production pieces and units. I didn’t plan it to last from August to May but looking back, I think a year is a perfect time to work on a piece. One packs for a long trip by taking breaks and not all at once or one tends to forget things; much in the same way, we took breaks from this production to work on other things, including a one act play and other curriculum. Having the breaks from the piece and being able to come back to it heightened the students’ own process of evolving through the work.

I still have the students who were a part of the production and they’re still talking. I also use the Reflection Packs with all levels of theatre students and discussions around those have shown me where some students would like to continue practising Verbatim Theatre. This is one student’s answer to the post production reflection, to the question: ‘What would you like to work on should we do another Verbatim project?’ ‘Possibly a reverse generation piece. Have older people recall their teen years and current teenagers responding to prompts about their “now”.’ In spite of the digital age, both groups would definitely find similarities and it might help parents/teachers/coaches etc understand more about what is happening internally with teenagers during this time.

I’m an American Theatre teacher who was fortunate enough to teach overseas for a few years. Now I’m back in America working with only American students.

Short of being able to put them on a plane and take them out in the world, I find great satisfaction in being able to guide students through World Theatre practices.

Now that I have many of these same students as Grade 11s, I see the growth they have made as performers, designers and overall, growth as humans. ◾

BY JESS THORPE

BY JESS THORPE

For the last twenty years I have introduced myself as a theatre maker. In much of my previous writing about my practice I have talked about the value of live experiences and the importance for human beings to be in the room together in order to create connection and make meaning. But what if you can’t? What if the tools you have always used just don’t work anymore? Is it possible to work in a new way?

Alongside making performance work within a mainstream theatre context, for the last fifteen years I have also had a research practice into the arts in criminal justice. During this time I have worked in ten of Scotland’s prisons (there are fifteen in total) as well as in prisons across the UK and the USA I have led projects lasting from one day to seven years in length and have worked in female, male and young people’s estates.

In 2019 my own company Glass Performance set up the first ever youth theatre in a prison based HMP YOI Polmont which is Scotland’s national facility for young men in custody.

The project was soon thriving and we had a waiting list of young people waiting to join. Then in March 2020 Covid19 hit and everything came to halt. The young men in our group were locked in their cells for twenty three hours a day with no activities, no visits and no sense of what would happen next

As an arts organisation we were mid-funding cycle. We had the financial resources in place and we had the time. We also felt we had an ethical and social responsibility not to abandon our connection with the young people in Polmont during this time, many of whom are among the most vulnerable and traumatised in Scotland.

Theatre was not going to work anymore but was there something else that could? How else might we use our skills to engage with the community behind the wall?

‘Iwasnolonger the‘expert’in theform–itwas somethingwe werefiguring outtogether andthe possibilities wereendless.’

In April 2020 the delivery team for Glass Performance, which was comprised of Louise Allan, Ricky Williamson and Gudrun Soley Sigurdottir with support from Tashi Gore set about developing a brand new project called The Jukebox. This took the form of a radio show which Gudrun and Ricky (and later Jack Tully) produced at home using the editing software Garage Band. They wrote to all the young people who had previously engaged with Polmont Youth Theatre using emailaprisoner com, a service that enables families and communities to send emails to contacts in prison (for a small fee). They collected song requests and ideas for sections of the show and each week they sent a two hour radio to the Media Centre Officer, Willie Mulholland who made sure it was played three times a day.

The project grew as more and more young people subscribed to receive emails and be part of creating the show. At the time of writing this article the group meets inside the prison each week and the show is produced by over thirty five young people who write and present the content and choose all the songs themselves. The show has won several Koestler Awards and a section ‘Time Piece’ was featured in the overall exhibition at the Southbank Centre in London in 2021 and has since been shared with a wider public audience

In August 2020 I was visiting Polmont to check on The Jukebox and Willie Mullholland relayed some feedback the project had received from a group of women also housed at the prison He told me: ‘They listen to the Jukebox every week but they say it’s not for them. They are wondering why can’t they have a show for women?’ It was a clear provocation. A call to action.

So in September 2020 I seconded myself in my role as lecturer in Arts in Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland to the task of creating a radio show for women. I was incredibly grateful to be joined at this time by Gudrun Schmidinger who was a third year BA student of the Contemporary Performance Practice programme at the RCS and had chosen to come on placement with the project. She took on the task of editing the show. Together we created ‘Women Talk’ and using the same process piloted by the Juke Box we began emailing women inside the prison in order to generate content for a fortnightly radio show.

In the beginning I found the prospect of making radio incredibly daunting. I had no idea how to work in this way and had not yet met the population of women who we were trying to engage. And yet in those initial weeks sitting in my bedroom staring at a blank computer screen I was reminded of a quote I had once read in an interview with the visual artist Judy Chicago. She was being asked about the tools she used to create her feminist art works and whether there was a specific one (drawing, painting, needlework etc) that she preferred to use. Her reflection was this:

‘For me it’s a content based pedagogical method: find your content and then best select the media which best expresses this content. Then if you need to develop the skills to mistress that medium. It is the content that motivates.’

www.cassoneart.com (August 2011)

This idea really resonated with me and it helped me to see that I had to be motivated by the situation in Polmont and the current need and not the limitations of my previous approach. My reasons for facilitating the arts in prisons were the same as they had always been - to provide human connection and creativity in spaces with increased isolation and deprivation of experience. But due to the pandemic the tools I would need to use to do this work had changed. I would now have to ‘mistress a new medium’ in order to best serve the challenges of the context and I would need to revise my thinking about the approach to my practice.

The first few episodes we created were tentative. They involved me talking about anything and everything that I found interesting and hoped that others might too. This included long extended sections on the inauguration of Kamala Harris and a huge exposition about Amelia Earhart, the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic. Looking back at these episodes makes me laugh at myself and also cringe a little. At best these attempts were clunky and at worst self-indulgent –but it was a start Soon more women started signing up to receive emails and began to send in song requests and things began to get easier. We experimented with new styles of presentation, created shorter snappy sections and invited different guests to talk on the show A quick poll of the women’s residential hall told us that around 70% of the population were listening to each show and so we continued. By August 2021 we had created 18 episodes.

In September 2021 we secured funding from Inspiring Scotland and were able to move the project into the prison. Artists Mona Keeling and Indra Wilson came on board to lead the weekly sessions based in the Media Centre and I stepped into the role of researcher. A group of twelve women came to meet us every week and took on the task of making the show themselves. As they grew in confidence and our relationship developed they began to tell me about their previous experiences of listening to the show I had made from my bedroom. They told me how boring they found some of it and the point that they felt it had started to get better.

How occasionally I had made them laugh and sometimes they had switched it off because they had had enough of my voice. They said they felt they had gotten to know me a little bit more with each episode and had enjoyed it when I shared things about my own life. They said they liked the music the best and it had been important to them when we had played their song requests and given shout outs to the people they loved.

In turn I shared with them my fear at not knowing how to make radio and how it had been an exploration in working in a new way. I confessed to my relief that they had now taken over the project and my feeling that the show was now much better. In many ways this felt like more of a level playing field. I was no longer the ‘expert’ in the form – it was something we were figuring out together and the possibilities

As I look back on the many things that this project has taught me, I realise that I no longer want to introduce myself solely as a theatre maker. Live performance will probably always be my first love but I now know that is not the only way to make real meaning with others. The inability to use my tried and tested tools in a moment where I really wanted to communicate has helped me to understand that the ‘why’ of my work should come before the ‘what’ I’m going to do and the ‘how’ I’m going to do it. Going forward I feel that I want always to be open to mistress a set of new skills and find alternative solutions as I try to make a genuine connection with others through the Arts. ◾

BY SOFIA MARTYN

BY SOFIA MARTYN

The term ‘wellbeing’ has gained prominence in our lives recently yet it is a broad concept that struggles to be defined. It is often used synonymously with mental health which may mislead people or stigmatise the concept Furthermore, wellbeing has many related concepts which are sometimes used interchangeably, such as: emotional intelligence, flow, growth mindset, happiness, mindfulness, positive psychology and wellness to mention a few. This discussion will explore the context of wellbeing from a socioemotional perspective and identify some of the ways

that theatre education contributes to the wellbeing of students.

The origins of wellbeing can be traced back to the Nicomachean Ethics where Aristotle referred to the notion of Eudaimonia; a Greek term that is often translated to signify ‘happiness’. Aristotle believed that eudaimonia was the ultimate goal in life or the summum bonum, as it was known in Latin. It could not be realised through fortuna or chance but through a conscious effort to live a successful life.

1 Debbie Watson, Carl Emery, and Phillip Bayliss Children’s Social and Emotional Wellbeing in Schools a Critical Perspective (Bristol Policy, 2012), 2 2 Aristotle, Jonathan Barnes, and Anthony Kenny Aristotle’s Ethics : Writings from the Complete Works (Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014), 17.Scholar, such as Otfried Höffe, Jonathan Barnes and Anthony Kenny have argued that eudaimonia does not translate as happiness but rather as ‘living or doing well. In fact, modern psychologists such as Dr Ilona Boniwell, contend that contemporary literature on the approaches to wellbeing ignore contributions from the humanistic and existential thinker, such as Maslow, Rogers, Jung and Allport and fail to consider the complexity of the ancient philosophical notions of happiness. Boniwell also highlights that there are two conceptions to happiness: Hedonic and Eudaimonic.

Emotional Intelligence and Positive Psychology; which have combined scientific and psychological research to propound the idea that individuals can learn how to a live happier and more fulfilling life.

In his book Flow, Csikszentmihalyi suggested that a person could achieve a state of ‘flow’ when they made a conscious effort to pursue something that they found difficult but worthwhile. He believed that ‘the best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort’ and that ‘optimal

Hedonic happiness refers to pleasurable moments or having a good time whereas Eudaimonic happiness refers to striving to achieve a goal or overcome a challenge either for personal growth or for the good of others.

Since the 1990s psychologists such as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990), Daniel Goleman (1995) and Martin Seligman (2000) have published their theories on Flow,

4 Höffe Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics ” , 35

experience is ... something we make happen.’

In Goleman’s book Emotional Intelligence, he believed that if people developed an understanding of their emotions and those of others, they could learn to regulate them.

Through self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and relationship management, Goleman believed that people could develop skills such as self control, zeal, empathy, persistence and self

5 Aristotle, Jonathan Barnes, and Anthony Kenny Aristotle’s Ethics : Writings from the Complete Works (Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014), 17

6 Ilona Boniwell Positive Psychology in a Nutshell : The Science of Happiness (Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press, 2012), 49

7 Ilona Boniwell 2 Types of Happiness: Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being PositivePsychology org uk, (2017),

http://positivepsychology org uk/happiness-hedonic-eudaimonic/

8 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper and Row, 1990), 3

‘apersoncouldachieveastateof'flow'whenthey madeaconciousefforttopursuesomethingthat theyfoundtobedifficultbutworthwhile.’

EmotionalIntelligence skillsplayakeyrolein theatreasstudents developanawarenessof themselvesandothers.

motivation, which would help them excel in their personal and professional lives.

In the year 2000, Seligman formalised the concept of positive psychology In his book, Authentic Happiness he proposed that people could be trained into living more positively if they learned to focus on ‘happiness, wellbeing, exceptionalism, strengths and flourishing’. All of these theories have gone on to influence the ‘positive education’ movement of the last twenty years which has impacted schools across the world. In the last decade or so schools have introduced wellbeing initiatives aimed at improving student happiness and increasing academic attainment.

Many of the values that psychologists suggest lead to a more fulfilling life are embedded in a well taught theatre programme, not to mention the benefits that extracurricular productions also promote. Surely many teachers can recall seeing students ‘in their flow’, buzzing with energy, elated with eudaimonic happiness after a performance or assessment Moreover, many will have encountered moments where their students have needed support to resolve an argument, bounce back after a failure or adopt a eudaimonic approach in order to meet deadlines.

To explore social emotional wellbeing from an IB DP Theatre perspective, a group of previous students were asked to recount why

they chose to study DP Theatre. It was surprising that their responses aligned more to a desire or priority for wellbeing, rather than for academic achievement. They cited: collaboration, autonomy over what to study, freedom of expression and freedom of creativity as the main reasons for their choice.

So, how does theatre contribute to wellbeing?

Drama and theatre have a longstanding tradition of teaching and upholding social values In western culture, theatre’s social function can be attributed to the Athenian tragedies from the 5th Century BCE.

9

Professor Jonathan Neelands references the philosopher Castoriadis to explain that tragedy served to reveal to the polis both the limitations and possibilities; ‘to show the world as changeable, but also to show through the concept of ‘hubris’ the limits of personal and collective action when these overstep or

9. Jonothan Neelands, “The Art of Togetherness: Reflections on Some Essential Artistic and Pedagogic Qualities of Drama Curricula,” NJ 33, no. 1 (2009), 14, https://doi.org/10.1080/14452294.2009.12089351.

‘Dramaandtheatre havealongstanding traditionofteaching andupholdingsocial values.’

ignore the principles of democratic life.’ Neelands goes on to suggest that ensemble work has a transformative power both personally and socially, quoting John McGrath who said:

knowledge together as relative equals.’

The theatre space is an environment where democracy and education come together. In Philip Taylor’s book The Drama Classroom he wrote: ‘Drama is a collaborative group artform where people transform, act, and reflect upon the human condition.’ As students engage their creative and critical thinking skills, the theatre lesson provides a forum to respond to what they discover. In IB assessments, students are constantly articulating their ideas from their initial intentions, developmental process to the post performance talkbacks. A dialogue is constantly present where the students depend on the teacher and peer feedback in order to improve.

The connection between democracy and education can be traced back over one hundred years to the writings of John Dewey. Neil Hopkins writes that Dewey envisioned the classroom as a shared enterprise ‘where people discovered and constructed

Emotional Intelligence skills play a key role in theatre as students develop an awareness of themselves and others. Peter J. Orange remarked that in researching and theatricalising an issue they examine and reflect both objectively and subjectively in an attempt to make sense of something that would otherwise be alien to them. Through practical explorations, students can step outside of their own world to explore the diversity that exists in other worlds. As Patsy Koch Johns explains:

10. Jonothan Neelands, “Acting Together: Ensemble as a Democratic Process in Art and Life,” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance 14, no. 2 (2009),185, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569780902868713.

11. John McGrath. “Theatre and Democracy.” New Theatre Quarterly 18, no. 2 (2002), 133. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266464x02000222.

12. Neil Hopkins, “Dewey, Democracy and Education, and the School Curriculum,” Education 3-13 46, no. 4 (2018), 434, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2018.1445477.

13. Philip Taylor, Drama in Practice: Action, Reflection, Transformation (London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2000), 1.

14. Peter J. Orange, “Educating International School Students for Global Citizenship through Theatre Arts Literacy” (dissertation, University of Surrey, 1994)

‘One of the great services theatre can perform for the people of any country or region or town or village is to be the instrument of authentic democracy, or at the very least to push the community as near to authentic democracy as has yet been achieved.’

‘Theatre[…]givesus anopportunityto mindtravel,and then[…]become betterhuman beings,more responsiblehuman beingsbecause we’reresponsible, notjusttoourlittle microcosmbuttothe wholeentireworld.’ PatsyKochJohns

When we imagine and try to comprehend the complexities of life, human behaviour and reason, we learn to empathise with others. Goleman asserts that ‘empathy is the ability to feel another person’s emotional state; it is not to be confused with sympathy which is just the ability to put yourself in another person’s shoes without a sharing of feelings.’ Empathy is a collective experience. Therefore, when students work together to contemplate issues and situations that are relevant to them, they pose questions, examine multiple perspectives and challenge orthodoxes. However, it can be a sensitive process that leaves them feeling vulnerable to their emotions and preconceptions. In Ian Morris’ book: Teaching happiness and well-being in schools: Learning to ride elephants, he reminds us that: ‘emotions are not facts rather they are reactions to our perception of the world ’ Students need to acknowledge and manage their emotions and be given time to pause and reflect.

Sometimes it is necessary to diverge from a lesson plan to allow for moments of contemplation or discussion in order to reach a collective consciousness. ‘Teachable moments’ are not planned but when they occur they allow us to embed

wellbeing into our lessons and focus on broader skills such as mindfulness and reflection. Morris advocates that:

‘Reflection leads to the skill of metacognition: thinking about thinking. Many of the advances that a person makes in their life come from reflecting on who they are and how they can change that for the better in light of learning something about how humans function.’

Dewey’s notion of reflective thinking was to suspend judgement and inquire further before making a conclusion. In his book, How We Think, he wrote:

‘To turn the thing over in mind, to reflect, means to hunt for additional evidence, for new data, that will develop the suggestion, and will either, as we say, bear it out or else make obvious its absurdity and irrelevance.’

Reflection is about exploring and testing our past and present beliefs and knowledge in order to forge our way forward. It is an attribute of the IB Learner Profile that encourages students to ‘give thoughtful consideration to their own learning and experience; to assess and understand

their strengths and limitations in order to support their learning and personal development’. Furthermore, reflection is a key component of the IB syllabus and it is formally assessed in each of the written assessments. Students are required to explain the impact that projects have had upon them, how they have shaped their responses to the work and evaluate their outcomes Reflection enables students to analyse their work objectively and subjectively before, during and after their projects in order to celebrate their accomplishments along with considering opportunities for improvement and growth. If teachers encourage them to be constructive in their criticism they take their best lessons forward.

It is with both previous experience and learned experience that students create some of their best work. Sir Ken Robinson wrote in the introduction to his book, Out of our Minds that ‘human intelligence is profoundly and uniquely creative. We live in a world that’s shaped by the ideas, beliefs and values of human imagination and culture.’ Robinson believed that there were three ideas related to creativity: imagination, creativity and innovation. When students conceive an idea, they engage their imaginations; through practical explorations they experiment to develop those ideas further and when innovate they apply new ideas. Theatre has a discursive power, according to Moisés Kaufman

because each element of the stage has its own way of communicating. When students are creating original work they draw on their imaginations to form narratives. They are conscious that meaning can be interpreted through the scenic and technical aspects such as costume, props, set, lighting and sound. Typically students have a heightened awareness that the way they use their face, voice, body, movement and gesture can convey meaning for the audience, they can become immersed in a state of flow as they consciously strive to realise their creative potential. In doing so students take steps towards fulfilling their creative potential as individuals. As Jonathan Neelands articulated in his speech, In the Hands of Living People:

‘We recognise that these students do not come to us as ”human beings” but rather as ”human becomings” - we believe that what we do is planned to help them in this journey of becoming. We try, by all manner of means, deriving from art and deriving from other sources, to put living reality into the hands of living people. The curriculum is the necessary map, it is not the journey itself.’

So perhaps we, as passionate theatre educators, can stock up on our provisions of wellbeing and accompany them on their way.

21 Ken Robinson, Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative (Chichester, West Sussex: Capstone, 2001), xvi

22 Robinson, Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative, 2

23. Moisés Kaufman et al., Moment Work: Tectonic Theater Project's Process of Devising Theater (New York: Vintage Books, 2018) 61.

24. “In the Hands of Living People - Theatroedu.gr,” accessed August 3, 2021, http://www theatroedu gr/portals/38/main/images/stories/files/Magazine/EandT e-mag

Here we spotlight and celebrate ISTA artist Megan Campisi’s Fulbright Specialist work with the Tatbikat Sahnesi company in Turkey. Megan discusses making art in challenging environments.

In a museum in Ankara sits a three thousand year old stone tablet guaranteeing a bride her ssets in case of divorce. In 2019

I travelled to Turkey through a USA Fulbright Specialist Award to give master classes in Lecoq based Tragic Chorus and Neutral Mask at Tatbikat Sahnesi, an independent theatre. My job was to offer tools for expression in a country where women’s rights are increasingly circumscribed, censorship in the arts is

'Weassume progress moves forward, butdoesit?'

routine, and creating theatre has become a precarious occupation

Standing in the museum staring at a millenia old prenup, my host from Tatbikat smiled wryly at me: ‘We assume progress moves forward, but does it?’

These days, many international artists and teachers are confronting challenging environments in which to explore theatre. As an American who started devising Lecoq based theatrein the USA and France, I took for granted my privilege to voice my social political beliefs however I chose, engaging openly with feminism, racism and ageism. But in 2012 I travelled to Shanghai to develop my play, The Subtle Body, with both Chinese and American actors through a TCG Global Connections grant. The project introduced me to a very different art making environment in which the choices we made had potentially serious consequences for my Chinese colleagues. When I was awarded a Fulbright to give master classes in Turkey, I knew I’d need to apply the lessons I’d learned in China. Full disclosure: I have no definitive answers as to how to safely make art in challenging contexts but below I’ll share how the Turkish company Tatbikat Sahnesi and I chose to collaborate in our time together.

company that performs in repertory as well as an actor training programme The theatre is committed to artistic exchange and creating art from a ‘free, positive, creative, enlightened and critical viewpoint’. Many of their plays are directed by the female co-founder, Elvin Besikçioglu and the productions are inventive, dynamic and highly physical. For example, Gogol’s Diary of a Madman (starring Besikçioglu’s husband and Tatbikat co-founder, Erdal Besikçioglu, a highly celebrated actor in Turkey) is performed entirely

First a little context Tatbikat Sahnesi is an independent theatre created in 2013 in Ankara. It has a resident acting

from the platform of a boom lift that Besikçioglu operates while acting, often moving himself directly into clown inspired face to face interactions with audience members. The production has been running weekly to sold out audiences since Tatbikat’s inception.

My master classes were intended to introduce the company actors and

"Therearethree masks:theone wethinkweare, theonewe reallyareand theonewehave incommon."

JacquesLecoq

I like to describe the Tragic Chorus as a group of individual ‘I’s that have become a ‘we’. This happens in real life: protesters, fans, revolutionaries, mobs. It sometimes helps to think of the chorus like a symphony orchestra: members each have their individual qualities, strengths and roles yet the collective is joined in a common purpose that transcends the individual. Sometimes they play together, matching pitch and tempo. Sometimes they contrast, enriching and complicating the whole (What the chorus is not: toga bedecked people droning on in unison!)

I began our work with Neutral Mask instruction, the physical training for Tragic Chorus (I taught in English and French with the help of two amazing bilingual company members who took turns translating and participating). Lecoq Neutral Mask is a very counterintuitive practice; Neutral Masks are not used in performance. Rather, they train actors how to perform without a mask. The absence of facial cues when wearing the mask (the expression of which is intended to approach ‘neutral’, expressing a calm, balanced curiosity) allows actors to focus on the stories intentional and unintentional their bodies tell. And our bodies tell stories hard won stories based on our life experiences (think: wrinkles, tight shoulders, an open smile). These are deeply important elements of our identity but in Neutral Mask we endeavour to get beneath these individual traits to find, as Jacques

Lecoq described: ‘a blank page on which any drama can be written’

Jacques Lecoq also said: ‘There are three masks: the one we think we are, the one we really are and the one we have in common’. In my view, the one thing we have in common with every human on earth is a physical body. While our experiences in our bodies differ vastly there are some common fundamentals of communication, such as breath (e.g. a held breath, a sigh), rhythm change (standing suddenly, a gentle wave) and states of tension (frozen in fear, chilled out). Neutral Mask begins by exploring how these fundamentals form the building blocks of storytelling. With the Tatbikat actors and students we started with physical exercises then moved into structured improvisations that explored near universal human situations like a person encountering the ocean for the first time, the reunion of loved ones or saying goodbye to someone forever

These improvs were silent but utterly different from mime. Rather than replacing language with gesture they existed in the moment ‘before words are needed’ or ‘after all the words have been spoken’. The actors and students discovered just how much could be conveyed in the turn of the head, an extended hand, a held breath or an acceleration into someone’s arms. It is seemingly simple but astonishingly powerful work.

Just as importantly, Neutral Mask work (tries to) exist outside of a specific social political context. In Neutral Mask we don’t play one specific person with a backstory but a Human from Anytime and Anyplace For example, in the exercise of saying goodbye to someone forever, the goal is not to communicate an individual psychological story of, for example, a Jewish refugee leaving her parents in 1939 but rather a Human Refugee leaving their Family Again it’s counterintuitive (isn’t good acting all about specificity?!) Neutral Mask is about specificity but the specificity of communicating the gravity and layers of emotion in a final goodbye through nuanced breath, rhythm and levels of tension. The idea is once you’ve grasped this fundamental physical work through the mask, you can take it off and layer on any details of setting and individual character you want. For the actors at Tatbikat, the indeterminate time/setting had a second advantage; it

wed them the freedom to explore erful experiences like division or usion in a context explicitly removed m their current social political ronment.

moved from there into Tragic rus proper, beginning with an stigation into the ‘architecture’ of ytelling, particularly how the spatial amics and tensions within a group or ween a group and an individual, vey meaning. We employed the e building blocks as in Neutral Mask breath, rhythm changes and states of tension then added action to examine how these elements can be distilled, refracted, diminished or enhanced by the collective.

Text came next. We began with ‘embodying words’ to create a deep, physical connection to the text (to feel the words in our bones and in our guts, not just our vocal apparatuses). We graduated to longer text, finding how words could integrate organically into the physical work to deepen and enrich the whole.

Choosing a text took care. We considered using an open text, which would allow for multiple interpretations but in the end chose to do the exact opposite. We used a Turkish translation of a speech by the American activist and hero Dr Martin Luther King Jr. The speech is so rooted in a distinct time, place, culture and situation (the 20th century American Civil Rights movement), we felt it a safe text with

which to explore tragic/epic themes of peaceful protest and inclusion (Please note: there is a critical line between exploring other cultures and cultural appropriation. We acknowledged this line in our workshops and strove to do the former.) The speech draws on specific sensory imagery like the swelter of summer in the American south. It speaks to the ongoing trauma of slavery experienced by American people and hopes for healing. The Turkish students could voice powerful feelings, dig deep and apply the techniques they were learning with enough distance from their own lives to feel secure in their explorations.

The strength of the women’s collective presence - owning their space and sharing their voices was stunning. I thought back to the Ankara museum and about how someone three thousand years ago took the time to engrave one woman’s rights in stone. And about how the words of an activist from more than a half century ago speaking on inclusion could become a safe proxy for a room of young Turkish actors to learn powerful ways to share their presence and voices As we applauded the pieces, it felt like everyone in the room - performers an audience - had become a ‘we’.

Reflecting on our work together, Tatbikat co-founder Elvin Besikçioglu noted that the actors and students had made visible progress both in their comfort expressing themselves physically and their ability to carry a story with epic/tragic themes. (She also coined the term ‘physical dramaturgy’ to describe some of our work, which I’ve since adopted.) Most importantly, she felt empowered to continue Tragic Chorus work in her devising and direction with Tatbikat Sahnesi.

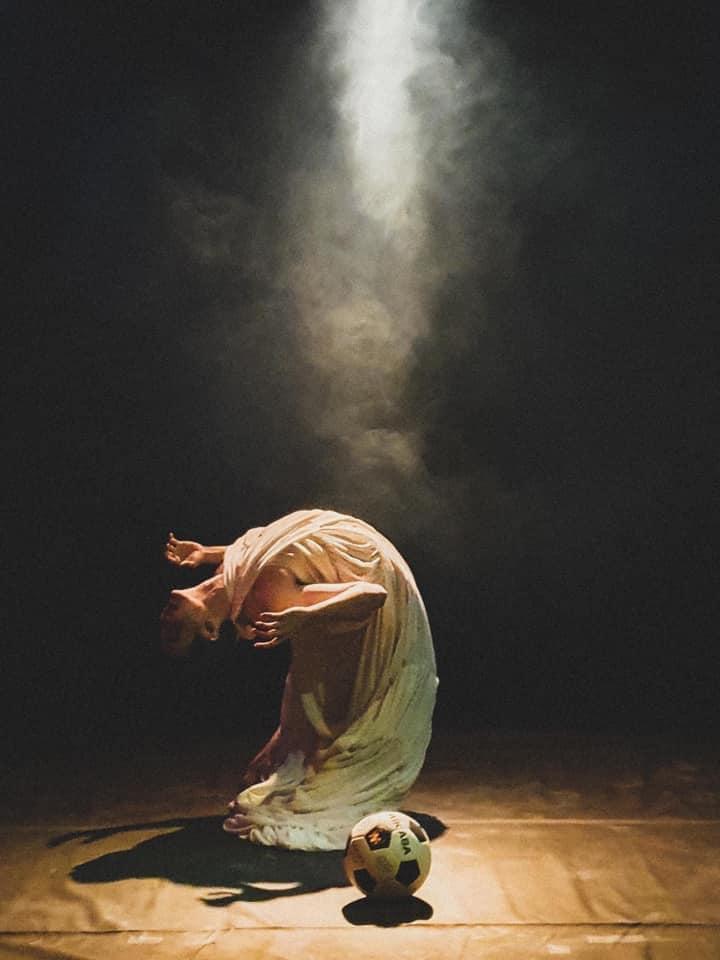

In our final days together, the acting company presented their short devised Tragic Chorus pieces to each other. One piece ended with a chorus of five women moving across the stage like stone statues grinding to life after centuries of stillness, while their voices floated, overlapping, like whispered prayers.

Again there are no easy answers to navigate the challenging environments in which many of us teach and create art these days but for us, looking to the past provided new avenues for the future

It is seemingly simple but astonishingly powerful work.

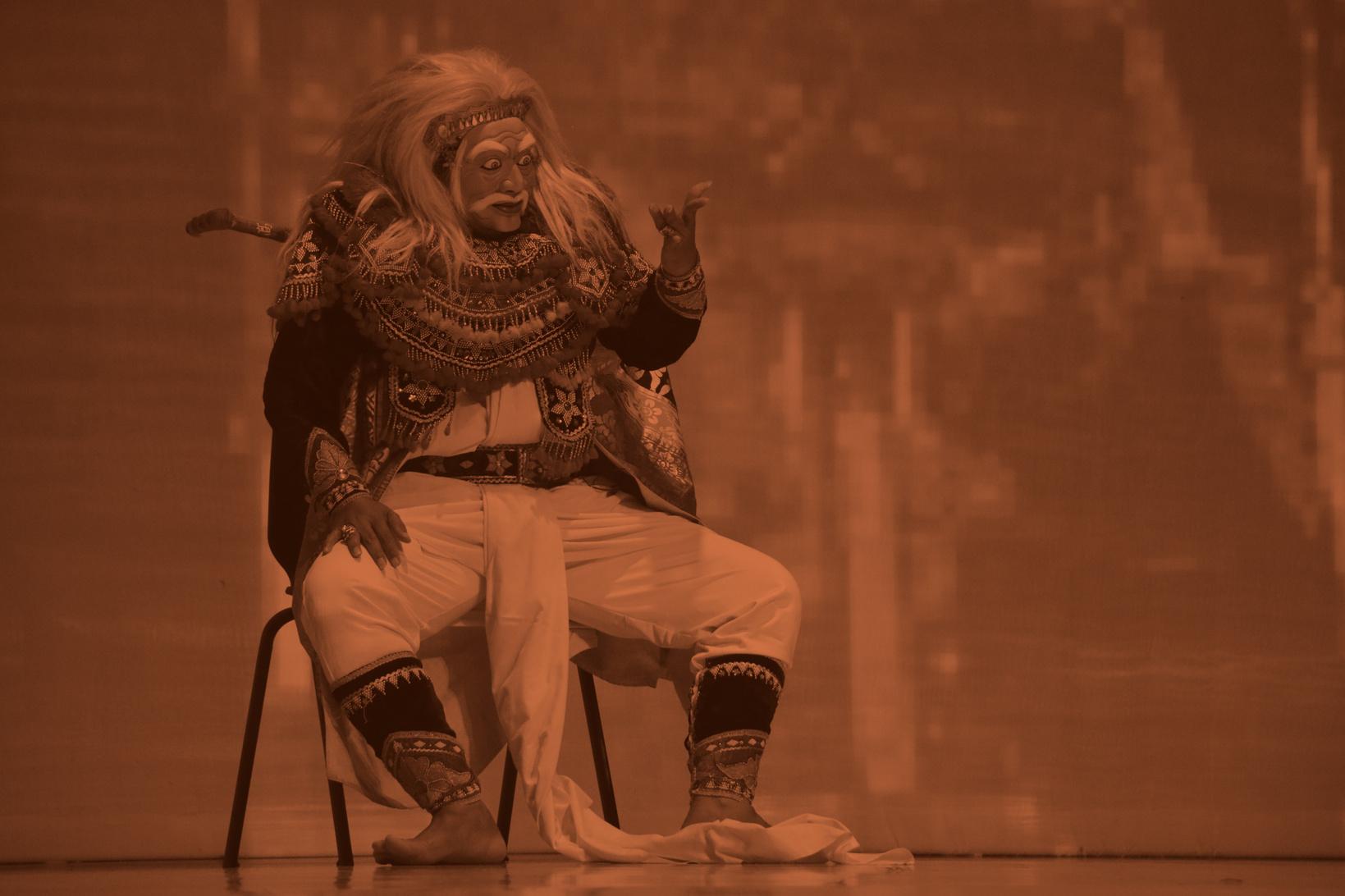

EachissueofSceneprofilesa theatrecompanyorgroupof artistsweareworkingwith. Thisgivesthemtheopportunity topresentthemselvestoour readers.HereMakhampom Theatretakescentrestage.

BY PIYASHAT SINPIMONBOON

Makhampom Theatre uses theatre, puppets, stage performances, traditional music and mime to help develop communities by encouraging local people to exchange opinions and ideas and take part in community projects. At the same time, Makhampom also trains local people and youths in the community to produce communication tools themselves

The Makhampom Theatre Group has been called a family, a kindergarten, a university, a community and a theatre troupe. In truth, we are a social organisation that works in the medium of theatre. Makhampom was born in 1980, emerging from the Thai pro-democracy movement to apply micro media for awareness-raising. Today, Makhampom wears many hats – as a performance collective, as a youth theatre umbrella organisation, as a social activist group working with communities and movements, as a creative educator, as a peacebuilding facilitator, as an international collaborator and trainer, as a social entrepreneur and as a theatre collective of over 500 members and volunteers, locally and internationally.

Starting from our 1st base in Bangkok, we expanded to our 2nd home, the Makhampom Living Theatre in Chiang Dao district, Chiang Mai province in 2004 and has become better known as the Makhampom Art Space today. This 2nd base is a place of creative community art where art can reflect beauty and truth, arousing inspiration and stimulating a feeling of humanity and justice. A community program throughout Chiang Dao is integrated with Chiang Mai and northern youth, ethnic minority and education initiatives and the hosting of national and international exchanges, collaborations and events. The place is similar to a bridge that connects people from all social classes and ethnicities, both from within and outside the community, enabling them to come together and experience art in the form of theatre, outdoor sculpture, painting exhibitions, photography and

art fairs. It is a space where people can come and have fun with creative arts themselves Visitors are welcome to exchange ideas, become inspired, be experimental and or just take a break in the natural environment of an art space amid green rice fields.

In 2005, we became the Makhampom Foundation to increase the scope and impact of our work and in 2013, the Gooseberry Arts company limited was registered as our social enterprise side of operations to bring our work to the public and partners while raising funds to sustain our group and keep our community projects running.