11 minute read

Do Spine Surgery Trainees Bring Value to Integrated Hospital Systems?

In recent years, value-based care has emerged as a central principle in modern healthcare delivery, yet the concept of “value” remains multifaceted and context-dependent. In a hospital system, value is often defined as the relationship between the quality of care provided and the cost incurred—essentially, the health outcomes achieved per dollar spent. For spine surgeons, this definition takes on additional complexity due to the variable cost, technical intensity, and site-specific outcomes associated with spinal procedures. While the emphasis in value-based models has traditionally focused on patient outcomes, the contribution of trainees—residents and fellows—to the value equation remains underexplored. Programs with trainees may show variance in both cost and quality of care, directly and indirectly, through involvement in surgical procedures, patient management, and hospital workflows. The present article aims to explore and quantify that value within the context of modern spine surgery practice and hospital system economics with regard to spine surgery.

How do we define value in spine surgery?

Value in healthcare is typically quantified using patient-centered outcomes relative to expenditure. Within spine surgery, these outcomes include both clinical results and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), such as patient satisfaction, pain reduction, and functional improvement. Commonly used PROMs include the Neck Disability Index, the modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association scale for cervicothoracic disease, the Oswestry Disability Index, the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire for low back pain, and the Scoliosis Research Society-22 for spinal deformity.1 These tools provide critical insight into the effectiveness of surgical interventions, though accurate assessment requires careful risk adjustment given the heterogeneity and complexity of spine patients.

Beyond PROMs, the concept of value in spine surgery has expanded through the framework of value-based healthcare, which emphasizes outcome measurement across the full cycle of care. 2 These outcomes range include survival and functional recovery (Tier 1), time to return to daily activities and complication rates (Tier 2), and the sustainability of outcomes and long-term sequelae (Tier 3). National and international spine registries, such as the American Spine Registry, AOSpine Knowledge Forums, and SweSpine, enable benchmarking of these outcomes at scale and help standardize definitions of value.2 Additionally, the integration of specialized care through multidisciplinary teams, as seen in integrated practice units, and the growth of centers of excellence further align spine care delivery with measurable value by streamlining workflows, reducing variability, and enhancing patient outcomes across anatomical and procedural complexities.

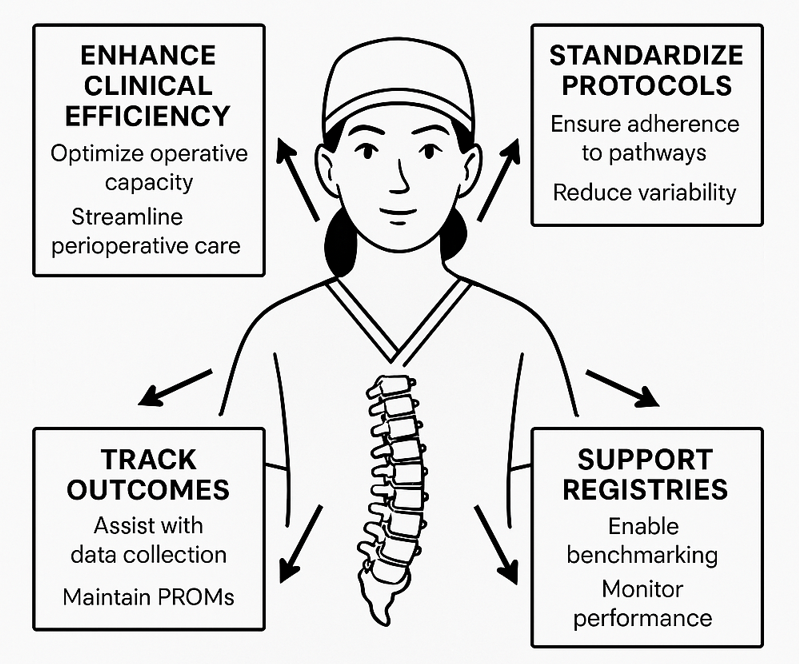

Trainees in spine surgery, such as residents and fellows, contribute meaningfully to value-based care by enhancing clinical efficiency, standardizing protocols, and supporting data-driven outcomes tracking. Their involvement in integrated spine teams helps ensure adherence to evidence-based pathways, reduces care variability, and supports coordination across the surgical episode. Trainees of ten assist in col lect ing and maintaining PROMs, which are critical for assessing functional recovery and long-term success. In academic and high-volume centers, they play a key role in sustaining registry participation and quality improvement initiatives, enabling benchmarking and real-time performance monitoring. By increasing operative capacity, streamlining perioperative care, and reinforcing protocol compliance, trainees help optimize outcomes and operational efficiency, which are core drivers of value in spine surgery.

How do we measure costs in spine surgery, and where do trainees fit into the equation?

While value in healthcare is often defined as outcomes relative to cost, the concept of cost itself warrants closer examination, particularly in the context of high-acuity, resource-intensive specialties like spine surgery. The site of service also plays a role in the valuation of trainees and the environment in which they are used. Residents may be the “opportunity cost” in academic medical centers, while fellows may provide a different role in high-throughput outpatient surgical centers. Cost can refer to a variety of expenditures, including direct financial outlays, opportunity costs, and resource utilization; it must be understood in relation to different stakeholders: patients, hospital systems, providers, and payers. For trainees, cost considerations are rarely emphasized during clinical education, yet they are central to how surgical care is financed, delivered, and optimized.

Unlike earlier healthcare models, where cost structures were relatively straightforward, modern reimbursement is shaped by third-party payers, bundled payment models, and complex billing systems. This has made accurate cost measurement increasingly challenging, especially at the individual procedure or patient level. While some hospital-related expenses—such as surgeon salaries, implants, and operating room (OR) time—are easily quantifiable, others are more difficult to allocate precisely.

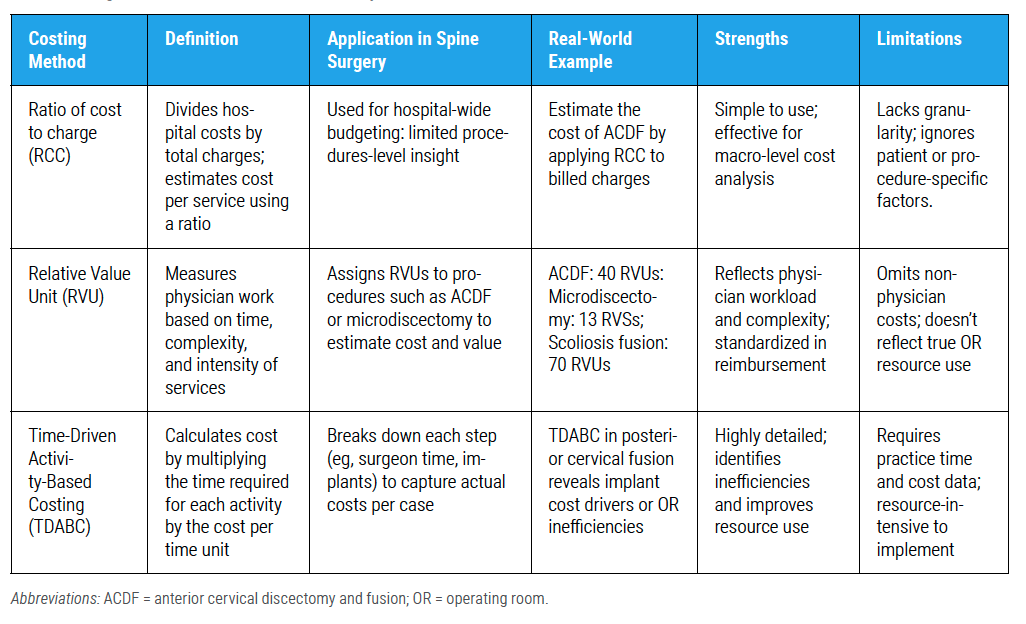

To navigate this complexity, three common methodologies are employed to estimate surgical costs: the Ratio of Cost to Charges (RCC), Relative Value Units (RVUs), and Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) (Table 1). The RCC method applies a standardized ratio across services to reflect institutional cost structures but lacks specificity and does not account for clinical outcomes. 3 RVUs, on the other hand, attempt to quantify the time, effort, and complexity involved in a procedure. For instance, a single-level microdiscectomy might generate significantly fewer RVUs compared to a multi-level scoliosis correction, highlighting the procedural variability inherent in spine surgery. TDABC, considered the most granular approach, calculates cost by multiplying the cost rate of a resource (eg, OR time, anesthesia, implants) by time. 3 This method is especially relevant in spine surgery, where prolonged operative times, specialized equipment, and intraoperative monitoring significantly impact resource utilization.

The OR serves as both a major cost center and a key revenue generator for hospitals, accounting for up to 40% of hospital expenditures and as much as two-thirds of overall revenue. 4 Spine surgery, with its high complexity and associated costs, plays a central role in this dynamic. Trainees— residents and fellows—are embedded within this economic equation. While requiring supervision and potentially increasing operative times initially, their participation in surgeries contributes to workforce efficiency, procedural throughput, and long-term sustainability of surgical services. Moreover, their presence can influence staffing models, case volumes, and downstream revenue through extended patient care contributions. Therefore, when assessing the cost in spine surgery, the inclusion of trainee-associated variables is essential to capture a more comprehensive and accurate economic picture.

How do workforce shortages and training costs affect the economic value of trainees in spine surgery?

The impending shortage of surgical specialists poses a significant challenge to the U.S. healthcare system. By 2030, it is estimated that more than 100,000 new surgeons will need to be trained to preserve adequate access to surgical care across the country. 5 Simultaneously, projections indicate a shortfall of 19,800 to 29,000 surgical specialists, underscoring an urgent need to expand training capacity. 6 Despite this, the current financial infrastructure supporting surgical education remains constrained.

On average, the annual cost of training a resident, including salary, benefits, and direct expenses, is approximately $80,000. 5 These costs are primarily subsidized by federal funding allocated through the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, which imposed a cap on Medicare-supported graduate medical education positions. While this cap was temporarily expanded in 2020 by 1,000 additional slots in response to physician shortages exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the increase remains modest relative to the projected demand.

Although some institutions have turned to alternative funding mechanisms, including state support, philanthropic donations, and internal hospital resources, these sources are limited in scale. This underinvestment is striking when considered in light of the contribution trainees make, particularly in high-revenue departments such as surgical services. In specialties like spine surgery, where operative cases often represent a hospital’s most significant income stream, residents and fellows not only contribute to clinical productivity but also enhance system capacity and surgical volume. As the healthcare landscape braces for a widening workforce gap, reevaluating the economic value of trainees beyond their educational cost is essential for informed policy and institutional planning.

How do we evaluate the operational impact of surgical trainees in spine surgery?

While the measurable economic value of surgical trainees is increasingly being recognized, much of their contribution lies in less tangible, yet equally critical, operational efficiencies. Admittedly, there are indirect costs associated with training residents, such as longer operative times and the additional teaching required in both the OR and clinic. However, these are often offset by substantial system-level and quality-of-life benefits for attending surgeons and the healthcare team. Many hospital systems use advanced practice providers (APPs) in both the outpatient and inpatient setting. APPs play a crucial role in hospital systems by assisting trainees in patient care, managing rising patient needs, and ensuring quality care. Unlike trainees, APPs can bill for their services, generating revenue and expanding clinic capacity when necessary. However, some hospitals impose patient limits and restrictive policies that may hinder their full potential in the outpatient setting.

Residents enhance workflow efficiency in numerous ways: preparing and finalizing clinic notes, streamlining documentation in electronic medical records, assisting with inpatient rounding, and facilitating admissions and discharges. These contributions reduce the administrative burden on attending physicians, enabling them to spend more time with patients or their families—benefits that, while difficult to quantify financially, significantly impact surgeon well-being and reduce burnout.

In the broader context of rising healthcare costs and increasing patient demand, understanding the full value of trainees is essential. Graduate medical education is supported by an estimated $12–$14 billion annually through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, effectively covering resident salaries and training costs. 4 With this major cost already externally subsidized, the remaining question is: what do residents and fellows bring to the system in return?

Recent studies have begun to quantify their impact, showing that surgical trainees can improve hospital performance and contribute positively to financial outcomes without compromising safety. In high-demand fields like spine surgery, where OR setup and case complexity often limit daily volume, residents and fellows help optimize block time and increase throughput. For instance, while the attending completes closure and final imaging in one room, a resident may initiate the next case, enhancing surgical flow and maximizing resource use. Additionally, their role in extending emergency coverage and crossroom support adds further operational value.

From the perspective of a surgical trainee, the ability to support efficient, high-quality care while alleviating the workload for attendings affirms their role not only as learners but also as integral members of the hospital ecosystem. Their contributions, both direct and indirect, should be recognized as essential to sustaining and advancing surgical care delivery in a system facing increasing demand and workforce shortages.

Conclusion

Understanding the economic value of trainees in spine surgery requires a comprehensive framework that accounts for their impact on operative efficiency, complication rates, educational costs, and long-term workforce sustainability. To fully tap the potential of trainees in spine surgery, future models should integrate them intentionally into value-based care initiatives through structured roles in clinical efficiency, outcomes tracking, and multidisciplinary care pathways. Institutions must also explore mechanisms to equitably recognize and compensate their contributions, ensuring that the value trainees bring to the system is reciprocated with meaningful educational, professional, and financial support. Aligning institutional goals with trainee development will be key to sustaining a high-value surgical workforce.

References

1. Beighley A, Zhang A, Huang B, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in spine surgery: a systematic review. J Craniovertebr Junct Spine . 2022;13(4):378.

2. Karhade AV, Bono CM, Makhni MC, et al. Value-based health care in spine: where do we go from here? Spine J. 2021;21(9):1409-1413.

3. Hennrikus WP, Virk SS. Inside the value revolution at Children’s Hospital Boston: time-driven activity-based costing in orthopaedic surgery. Harvard Orthop J. 2012;14:50-57.

4. Scarola S, Morrison L, Gandsas A, Cahan M, Turcotte J, Weltz A. Evaluating the impact of surgical residents on hospital quality and operational metrics. J Surg Ed. 2025;82(2):103374.

5. Williams TEJ, Satiani B, Thomas A, Ellison EC. The impending shortage and the estimated cost of training the future surgical workforce. Ann Surg. 2009;250(4):590.

6. Kirch DG, Petelle K. Addressing the physician shortage: the peril of ignoring demography. JAMA 2017;317(19):1947-1948.

7. Katz AD, Song J, Bowles D, et al. What is a better value for your time? Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion versus cervical disc arthroplasty. J Craniovertebr Junct Spine . 2022;13(3):331.

8. Lorio D, Twetten M, Golish SR, Lorio MP. Determination of Work Relative Value Units for management of lumbar spinal stenosis by open decompression and interlaminar stabilization. Int J Spine Surg. 2021;15(1):1-11.

Contributors:

Michelle Scott, MD

Hania Shahzad, MD

Safdar N. Khan, MD

Hai V. Le, MD, MPH

From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at UC Davis Health in Sacramento, California.