How Design Reflects Cultural Identities and Why Our Understanding Creates

More Thoughtfully Designed Spaces

Isabel Dingus | ANTH 490 Anthropology Senior Capstone

Virginia Commonwealth University, College of Humanities and Sciences

POSTER ABSTRACT

The built environment serves as a physical reflection of a society’s ethos, values, and socio-political narratives. This Interaction between space and cultural principles emphasizes the intricate relationship design, cultural identities, and how we occupy the spaces we use have on each other; Highlighting how each element both influences and is influenced by the broader context of human experience and expression. By first recognizing how space is used within different cultural contexts, we then can begin to create design solutions that connect with its user, ensuring both functionality and cultural relevance. As societies change and grow, so do their spatial needs and aesthetic preferences, creating a foundation for design to continually adapt with it. Recognizing these shifts is important for architects and designers to remain responsive to the changing cultural fabric. This paper begins to explore how design principles are influenced by socio-cultural nuances, examining the symbiotic relationship between aesthetics, and the fundamental values different societies hold.

WHAT IS CULTURAL IDENTITY?

IN THE CONTEXT OF DESIGN...

Cultural identity in design refers to the incorporation of distinctive cultural elements, symbols, and traditions into the visual and functional aspects of a creative work, aiming to authentically represent and resonate with a specific community or group. It involves a thoughtful integration of aesthetics, materials, and spatial considerations that reflect the shared values and unique characteristics of a particular cultural identity. (Williams & Rieger 2015, pages 15-21)

ROLE OF ANTHROPOLOGY

IN THE CONTEXT OF DESIGN...

Anthropology contributes to design by revealing the intricacies of human behavior and cultural norms through methods like ethnographic research. This deep understanding allows designers to create environments that align with diverse cultural perspectives and user needs. By integrating anthropological insights, design becomes more culturally sensitive, fostering inclusivity and enhancing the user experience across various social and cultural contexts. (Ibelings 2011, pages 123-126)

PHENOMENOLOGY, PLACE, AND ARCHITECTURE

ARCHITECTURE AS LIFEWORLD:

Buildings aren’t just static structures; they are the sum total of actions, experiences, and events that are intrinsically tied to the individuals and groups that inhabit and utilize them.

(Seamon 2017, page 124 -264)

CONCLUSION AND CONTINUING RESEARCH

ARCHITECTURE AS ATMOSPHERE:

Building’s have character. Every building exudes a unique “aura or ambience,” making it distinct and contributing to its identity as a “place” Evoking specific feelings and reactions from those who interact with it.

(Seamon 2017, page 124 -264)

CROSS CULTURAL THEORY

IN THE CONTEXT OF DESIGN...

Cross-cultural theories in architecture recognize the significance of cultural diversity in shaping the built environment. They advocate for an inclusive approach that considers the socio-cultural contexts, traditions, and values of various communities. By incorporating insights from different cultures, architects can create spaces that foster a sense of belonging and address the diverse needs of their users.

(Memmott 2008, pages 51-68)

ARCHITECTURE AS PLACE WHOLENESS:

Buildings have a symbiotic relationship between its users. A building’s design either bolsters or detracts from a cohesive, integrated experience between the architecture and its inhabitants.

(Seamon 2017, page 124 -264)

Recognizing and understanding cultural identities in design is a fundamental catalyst for creating spaces that are not only aesthetically pleasing but also deeply resonant with the communities they serve. By embracing the diverse traditions, values, and perspectives embedded within cultural identities, designers can begin to integrate these profound cultural nuances into the growing built environment. In doing so, spaces become more than structures; they evolve into physical embodiments of shared values, histories, and identities. In an era of ever-evolving cultural landscapes, designers are compelled to make a continuous commitment to educate themselves on diverse cultural contexts. Through ongoing learning, designers not only create spaces that resonate authentically and respectfully with a global audience, but also shapes a built environment that continues to tell the narrative of our collective stories. (Chambers 2020, pages 193-197)

Figure 1: Abandoned Printing and Publishing office in Lebanon Source: (James Kerwin, 2018)

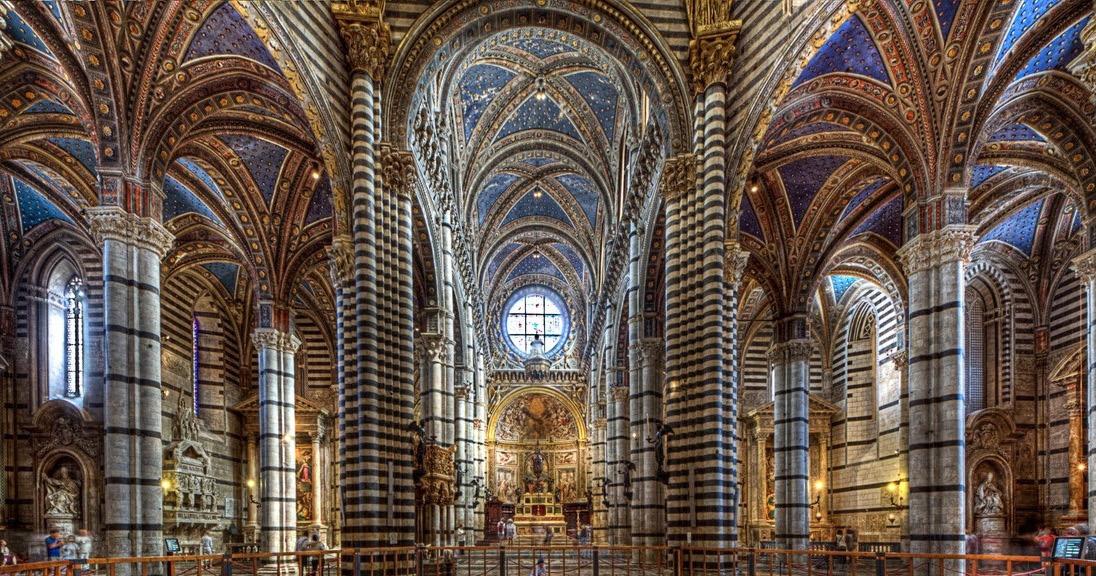

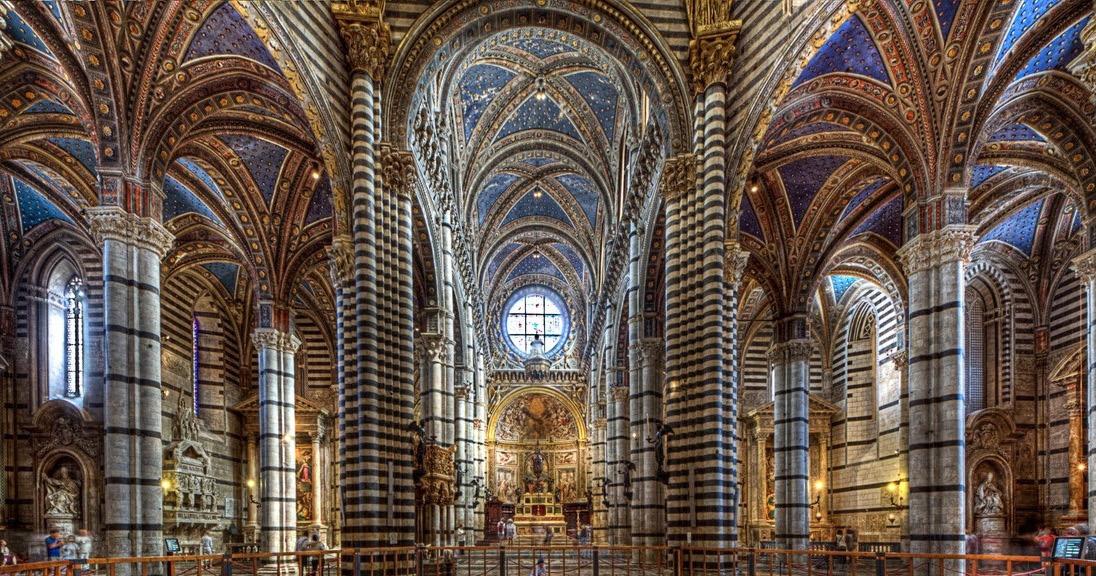

Figure 2: The Siena Cathedral Source: (Lulis, 2017)

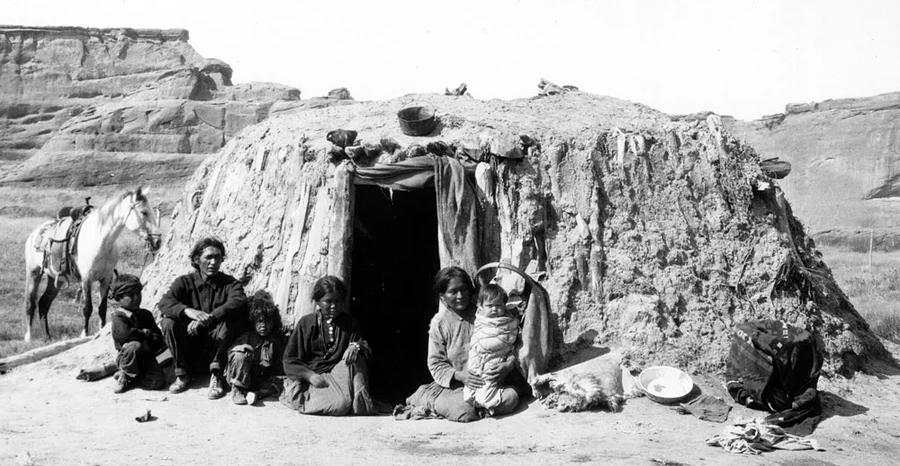

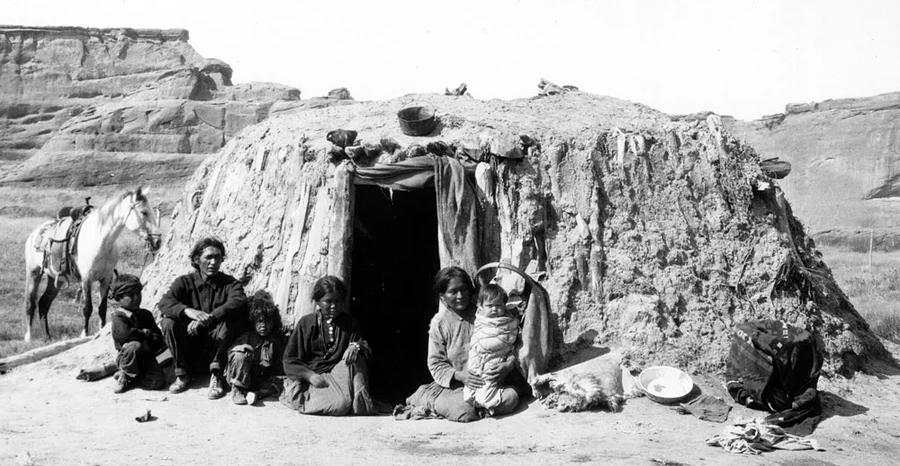

Figure 3: A Navajo family in front of a hogan, a traditional Navajo home, in Canyon de Chelly in 1927. Source: (Northern Arizona University Cline Library)

REFERENCES: Askland, H. H., Awad, R., Chambers, J., & Chapman, M. (2014). Anthropological quests in architecture: pursuing the human subject. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, 8(3), 284. Ibelings, H. (2011). False Friends: Architectural History and Anthropology. Etnofoor, 23(2), 123–126. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23217864 Maudlin, D., & Vellinga, M. (Eds.). (2014). Consuming Architecture: On the occupation, appropriation and interpretation of buildings. Routledge. 109-203 Memmott, P., & Davidson, J. (2008). Exploring a Cross-Cultural Theory of Architecture. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, 19(2), 51–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41758527 Seamon, D. (2017). Architecture, place, and phenomenology: Lifeworlds, atmospheres, and environmental wholes. Place and phenomenology, 247-264. Williams, W. A., & Rieger, J. (2015). A Design History of Design: Complexity, Criticality, and Cultural Competence. RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne Canadian Art Review, 40(2), 15–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43632228

HowDesignReflectsCulturalIdentitiesandWhyOurUnderstanding CreatesMoreThoughtfullyDesignedSpaces

IsabelDingus

VirginiaCommonwealthUniversity

November30,2023

1

Abstract

Thebuiltenvironmentservesasaphysicalreflectionofasociety'sethos,values,and socio-politicalnarratives.ThisInteractionbetweenspaceandculturalprinciplesemphasizesthe intricaterelationshipdesign,culturalidentities,andhowweoccupythespacesweusehaveon eachother;Highlightinghoweachelementbothinfluencesandisinfluencedbythebroader contextofhumanexperienceandexpression.Byfirstrecognizinghowspaceisusedwithin differentculturalcontexts,wethencanbegintocreatedesignsolutionsthatconnectwithitsuser, ensuringbothfunctionalityandculturalrelevance.Associetieschangeandgrow,sodotheir spatialneedsandaestheticpreferences,creatingafoundationfordesigntocontinuallyadaptwith it.Recognizingtheseshiftsisimportantforarchitectsanddesignerstoremainresponsivetothe changingculturalfabric.Thispaperbeginstoexplorehowdesignprinciplesareinfluencedby socio-culturalnuances,examiningthesymbioticrelationshipbetweenaesthetics,andthe fundamentalvaluesdifferentsocietieshold.

2

HowDesignReflectsCulturalIdentitiesandWhyOurUnderstandingCreatesMore ThoughtfullyDesignedSpaces Introduction.

Culturalidentityinthecontextofdesignreferstotheuniqueandmultifacetedexpression ofacommunity'svalues,traditions,andheritagethroughvariousartisticandfunctionalelements.

Indesign,whetheritbearchitectural,graphic,orproductdesign,culturalidentityisreflectedin thechoiceofmaterials,forms,colors,andsymbolsthatresonatewithaspecificcommunity's historyandbeliefs.Understandingtheseculturalinfluencesiscrucialinarchitecturaldesignasit ensuresthatstructuresnotonlyservefunctionalpurposesbutalsocontributetothepreservation andcelebrationofacommunity'sidentity.Recognizingandincorporatingtheseculturalnuances intoarchitecturaldesignfostersasenseofbelonging,promotesculturalsustainability,and enrichesthebuiltenvironmentwithcreatingspacesthatresonateauthenticallywiththepeople theyserveandnarratingoursharedstories.

HistoricalContextofDesignandCulture.

Inrecentdecades,thehistoricalinterplaybetweendesignandculturehasgivenrisetoa narrativethathasnotonlyinfluencedthephysicalmanifestationsofdesign,buthasalsoplayeda pivotalroleinapersistentdebateregardingitsdefinitionandacademicmethodologies.Scholars suchasAdrianFortyandCliveDilnothavebeencreditedinexploringtheshiftinthinkingabout discipline-specificmethodsandapproachestoteachingdesignhistory,highlightingtheinherent distinctionsbetweendesignandartpractices.Designhistoryhastransitionedfromanart historicalapproachtoamaterialcultureperspective,characterizedbyamultidisciplinary orientationthatplacesemphasisonthecontextualaspectsofproduction,consumption,and mediation.Thisdeparturefromrigiddefinitionsandnarrowvaluesintroducesnewwaysfor

3

comprehendingthehistoricalintegrationofculturalelementsindesign.Thematerialcultural perspectivenotonlyenhancesthestudyofdesignprinciplesovertime,butalso“providesa fertilegroundforcriticalengagement,encouragingdiscourseonbothdesignhistoryandthe dynamicevolutionofdesignpractice”(Williams&Rieger2015,pages15-21).

TheRoleofAnthropologyinUnderstandingArchitecturalNeeds.

Thefieldofanthropologyhasalsoplayedacrucialroleinenhancingourunderstanding ofculturalnormsandhumanbehavior,offeringinsightsintohowsocietiesinteractwiththeir builtenvironments.Throughanthropologicalmethodologieslikeethnography,anthropologists observeandanalyzehowindividualsinteractwiththeirbuiltenvironments.Studyingrituals, customs,andeverydaypractices,theyuncoverpatternsthatinfluencetheuseandperceptionof architecturalspaces(Asklandetal.2014,pages286-287).Bystudyinghowdifferentcultures perceiveandutilizespace,architectsgainamorecomprehensiveunderstandingofthediverse waysinwhichpeopleengagewiththeirsurroundings,enablingarchitectstodesignspacesthat alignwithculturalvaluesanduserneeds.Despitethis,thereexistsadisconnectionbetween anthropologyandarchitecture,ashighlightedbyarchitecturalhistorianHansIbelings.He emphasizestheimportanceofinterdisciplinarydialogue,urgingarchitectstointegrate anthropologicalinsightsintothedesignprocess,movingbeyondafocusonaesthetics(Ibelings 2011,pages123-126).Thiscollaborativeapproachensuresthatarchitecturalendeavorsarenot onlyvisuallyappealingbutalsoculturallyresonantanduser-centric,addressingtheevolving natureofspacesandglobalperspectives.

4

ExploringCulturalIdealsandDomesticSpaces.

Whendiscussingculturalideals,domesticspacesemergeaspivotalagentsthatshapeand influencevariousaspects,rangingfromarchitecturaldesigns,interiorlayouts,andeventhe symbolicsignificanceattachedtoelementswithinadwelling.Embeddedwithineveryhomeare deeplyrootedvalues,beliefs,andsocietalnormsspecifictoagivenculture.Forexample, culturesprioritizingcommunallivingtendtodesigndomesticspacesthatfacilitateshared activities,fosteringasenseoftogethernessthroughopenfloorplansandcommonareas.In contrast,culturesvaluingindividualprivacymaystructurehomeswithseparate,privatespaces foreachfamilymember.However,DeborahChamberscriticallyscrutinizesprevailingnotionsof domesticitythatpredominantlyportrayhomesasspacesforheterosexual,nuclearfamilies.These ideologies,ingrainedinpolicies,housingdesigns,andmediarepresentations,notonlyhetero normalizedomesticspacesbutconfinewomenpredominantlytothedomesticsphere,associating themwithtaskssuchasdomesticlaborandchildcare(Chambers2020,pages146-147).

Chambersarguesthatthesedominantparadigmsofhomelifefacepersistentchallengesand reshaping.Thistransformationisevidentininnovativehomemakingpracticesthataccommodate alternativedomesticities,therebyalteringthewayculturalidentitymoldstheconceptofhome (Chambers2020,pages162-163).

CaseStudy:AboriginalIdentitiesinArchitecture.

InacasestudypresentedbyShaneenFantin,theexplorationofAboriginalidentitiesin architecturehighlightstherelationshipbetweenbuiltenvironmentsandculturalidentity, particularlyfocusingontherepresentationofculturalelementsinpublicbuildingssuchas culturalcenters,museums,andartspaces.TheJulyuruNgaanyatjarraCentreinWarburton, WesternAustraliawasdesignedtopurposefullyalignwiththegoalofsupportingandfostering

5

existingAboriginalpractices,contributingtothepreservationandcontinuationofAboriginal heritage.ThecenteralsoemphasizesacommitmenttomaintainingAboriginaletiquette, showcasingadeeprespectforthelayeringofAboriginalknowledgesystems(Fantin2003,pages 84-87).Thisdesignapproachgoesbeyondthephysicalstructurebyembodyingculture acknowledgingtheimportanceoftraditionalpracticesandknowledgewithinthearchitectural space.Thestudyfurtherillustratesthechallengesencounteredandthesuccessesachievedinthe processofintegratingAboriginalidentitiesintoarchitecturaldesign.Byaddressingboththe obstaclesfacedandthepositiveoutcomes,thiscasestudycontributestotheunderstandingofthe complexitiesinvolvedinauthenticallyincorporatingculturalidentitiesintoarchitectural frameworks.

Phenomenology,Place,andArchitecture.

Phenomenology,aphilosophicalapproachemphasizingthestudyofindividual experiencesandconsciousness,beginstoexploredynamicsbetweenhumanperceptionand architecturalspaces.Inarchitecture,phenomenologyservesasalensthroughwhichdesigners andinhabitantscancomprehendtheprofoundimpactofspatialexperiences.Bystudyingthe subjectivenatureofperception,phenomenologyenablesanexplorationofhowindividuals engagewiththeirsurroundings,focusingonsensorystimuli,emotions,andmemories.(Seamon 2017,page124)Thisintrospectiveanalysisfostersadeeperunderstandingofthenuanced relationshipsbetweenpeopleandthebuiltenvironment.

ProfessorofEnvironment-BehaviorandPlaceStudiesDavidSeamonbreaksdownthe relationshipofbuildingswiththeirsurroundingsandusersintothreeprimarycategories.

ArchitectureasLifeworld:Buildingsaren'tjuststaticstructures;theyarethesumtotalofactions, experiences,andeventsthatareintrinsicallytiedtotheindividualsandgroupsthatinhabitand

6

utilizethem.Thisapproachchallengestraditionalarchitecturalperceptions,suggestingthat buildings,inessence,arelivingtestimoniesofsocietalinteractionsandengagements.

ArchitectureasAtmosphere:Building'shavecharacter Hesuggeststhateverybuildingexudesa unique“auraorambience,”makingitdistinctandcontributingtoitsidentityasa"place".

ArchitectureasEnvironmentalandPlaceWholeness:Buildingshaveasymbioticrelationship betweenitsusers.Abuilding'sdesigneitherbolstersordetractsfromacohesive,integrated experiencebetweenthearchitectureanditsinhabitants(Seamon2017,pages247-264).His researchactsasabenchmarkforarchitects,urbandesigners,andacademicstoreconsiderthe interplayofhumanexperiences,activities,andinterpretationswithinthebuiltlandscape.

TheInteractionBetweenSymbolismandArchitecture.

Whetherit'sthechoiceofmaterials,theformofabuilding,orthearrangementofspaces, eachdecisionbythearchitectcancarrylayersofsymbolism.Thesearchitecturalelementsoften carryvaluesthatconveymeaningandevokeemotions.Beyondthestructuralpurposeofarches ingothiccathedrals,theysymbolizeaspiration,reachingtowardsthedivine.Similarly,the incorporationofspecificmaterialsintraditionalJapaneseteahouses,suchasbambooandtatami mats,reflectsaprofoundconnectiontonatureandsimplicity.Eachcarriessymbolismthat communicatescultural,social,andhistoricalmessages.Formsofbuildingscanalsobea powerfulsymbolthatreflectsaculturalheritage.ThearchitecturalcomplexityoftheGreatWall ofChina,spanningoverthirteenthousandmiles,notonlyreflectsatimeofwarbutalsocenturies ofdynastichistory,unity,andadvancedengineering.Theartistryofarchitecturegoesbeyondthe functionalityofstructures,becomingalanguagethatcommunicatesthevaluesandnarrativesof societiesacrosstimeandspace.Inthisway,architectsbecomestorytellers,craftingstories throughthedeliberatechoicesembeddedintheveryfabricofthebuiltenvironment.Leavinga

7

lastingimprintonthecollectiveconsciousnessofthosewhoinhabitorencounterthesespaces (Smith,&Bugni2006,pages123–155).

Cross-CulturalTheoriesinArchitecture.

RatherthanprioritizingWestern"capital-Aarchitecture,"cross-culturaltheoriesin architectureinvolvetheexplorationandintegrationofdesignprinciplesacrossvariouscultural contexts.Thesetheoriesadvocateforamoreinclusiveapproachthatacknowledgesandrespects theintrinsicvalueofallbuildingformswithintheirrespectiveculturalenvironments.This perspectivechallengesthedominantEuro-Americanarchitecturalnarrative,whichhas historicallymarginalizednon-Westernbuildingtraditions(Memmott2008,pages51-68).By exploringandintegratingdesignelementsfromvariousculturalcontexts,architectscontributeto amorecomprehensiveandholisticarchitecturetheory.Thisapproachrecognizestherichnessof architecturaltraditionsgloballyandseekstounderstandhowcultural,social,andenvironmental factorsshapethebuiltenvironment.Theemphasisisoncreatingspacesthatauthenticallyreflect theidentitiesofdiversecommunities,movingawayfromaone-size-fits-allmentalitythatoften characterizesmainstreamarchitecture.

Innavigatingthecomplexitiesofdesigningformulticulturalsocieties,architectsmust exerciseculturalsensitivitytoavoidappropriationwhileincorporatingauthenticelements.The challengeliesinnegotiatingconflictingpreferencesandvaluesrootedindiversecultural backgrounds.Strikingadelicatebalancethatsatisfiesvariedexpectationsrequiresnotonlyan understandingofdifferentarchitecturalidentities,butakeenawarenessofsocialdynamics.This holisticapproachtoarchitecturegoesbeyondaestheticconsiderations,addressingthefunctional andenvironmentalaspectsofthebuiltenvironment.Itrecognizesthatauthenticityindesign

8

involvesmorethansuperficialculturalreferencesandrequiresadeepunderstandingofthe historical,social,andenvironmentalcontextsinwhicharchitectureexists.

Culturalappropriationinarchitectureisacomplexandcontroversialissuethatarises whendesignersdrawinspirationfromaspecificculturewithoutfullyunderstandingor respectingitshistorical,social,andsymbolicsignificance.Thispracticeoftenresultsinthe incorporationofelementssuchasmotifs,styles,ormaterialsfromaparticularcultureinto structuresthatmaylackthecontextualunderstandingnecessaryforarespectfulinterpretation.

Criticsarguethatthiscanleadtothecommodificationanddilutionofculturalidentities, perpetuatingstereotypesanddiminishingthevalueoftheoriginalculturalexpressions.Onthe otherhand,proponentsofcross-culturalarchitecturalinfluencessuggestthatborrowingfrom diversetraditionscanleadtoinnovationandthecreationofhybridstylesthatenrichthe architecturallandscape(Maudlin2014,pages133-154).

BuildingIdentitiesThroughArchitecture.

Architectureplaysapivotalroleinshapingandexpressingculturalandindividual identities,servingasatangiblemanifestationofacommunity'svalues,history,andaspirations.

Thedesignandconstructionofbuildingscanbeapowerfultoolforfosteringasenseof belongingandprideamongindividuals,aswellasconveyingadistinctiveidentityforanentire community.Forinstance,theiconicTajMahalinIndianotonlystandsasatestamenttoMughal architecturebutalsosymbolizesloveandeternalbeauty,reflectingtheculturalidentityofthe region.Similarly,theSydneyOperaHouseinAustralia,withitsuniqueandavant-gardedesign, isasymbolofmodernityandthecountry'scommitmenttothearts.Inbothcases,these architecturalmarvelsnotonlyserveasfunctionalpurposes,butactassymbolsdeeply intertwinedwiththeidentityofthecommunitiestheyrepresent.Beyondiconiclandmarks,local

9

architecture,includinghouses,publicspaces,andcommunitystructures,canalsocontributeto buildingacollectiveidentity.FromthevibrantcolorsofthebuildingsinBurano,Italy,reflecting theisland'slivelyspirit,totheintricatecarvingsontraditionalMaorimeetinghousesinNew Zealand,architecturebecomesalanguagethatcommunicatestheessenceofacommunity

Architecturenotonlyshapesbroaderculturalidentities,butplaysacrucialroleincrafting andreinforcingindividualidentities.Considerpersonallivingspacesthatserveasacanvasfor self-expressionandidentityformation.Fromthecarefulselectionofmaterialsandcolorstothe thoughtfularrangementofspaces,individualsinfusetheirlivingenvironmentswithelementsthat mirrortheirdistinctpersonalitiesandpreferences.Thiscapacityforcustomizationallowsfora personalizedexpressionofone'sidentity,throughtheinclusionofsentimentalobjectsand integrationofpersonalinterestsintotheoveralldesign(Chambers2020,pages193-197).The processofpersonalizationgoesbeyondresidentialspaces;itextendstoworkplaces,where individualsactivelyseekenvironmentsthatresonatewiththeirprofessionalidentityand aspirations.

Thispersonalizedapproachtoarchitectureisfoundintheexaminationofa17th-century Icelandicpassagewayhouse,asexploredbyMímisson'swork.Thisstudydivergesfromthe conventionalarchitecturaldiscourse,whichoftenrevolvesaroundformandfunction.Instead,it looksintothediverseinterpretivepossibilitiesinherentinarchaeologicalconstructs.Mímisson's analysisencompassesascrutinyofbuildingmaterials,constructionprocesses,andtheintricate interplayofcomponentsthatconstitutethearchitecturalentity.Byshiftingthefocusfroma homogenizedviewofarchitecturetoonethatembracespersonalizedpracticesandnarratives, thisresearchemphasizesthatarchitectureisnotjustastaticbackdropbutadynamicreflectionof individualizedchoicesandculturalstories(Mímisson2016,pages207-227).

10

Conclusion.

Recognizingandunderstandingculturalidentitiesindesignisafundamentalcatalystfor creatingspacesthatarenotonlyaestheticallypleasingbutalsodeeplyresonantwiththe communitiestheyserve.Byembracingthediversetraditions,values,andperspectivesembedded withinculturalidentities,designerscanbegintointegratetheseprofoundculturalnuancesinto thegrowingbuiltenvironment.Indoingso,spacesbecomemorethanstructures;theyevolve intophysicalembodimentsofsharedvalues,histories,andidentities.Inaneraofever-evolving culturallandscapes,designersarecompelledtomakeacontinuouscommitmenttoeducate themselvesondiverseculturalcontexts.Throughongoinglearning,designersnotonlycreate spacesthatresonateauthenticallyandrespectfullywithaglobalaudience,butalsoshapesabuilt environmentthatcontinuestotellthenarrativeofourcollectivestories.

11

References

Askland,H H,Awad,R,Chambers,J,&Chapman,M (2014) Anthropologicalquestsin architecture:pursuingthehumansubject Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research,8(3),284

Chambers,D (2020) Cultural Ideals of Home: The Social Dynamics of Domestic Space (1st ed) Routledge https://doiorg/104324/9781315205311

Fantin,S (2003) Aboriginalidentitiesinarchitecture:howmightarchitectureinterpretcultural identity? Architecture Australia,92(5),84-87

Ibelings,H.(2011).FalseFriends:ArchitecturalHistoryandAnthropology. Etnofoor,23(2), 123–126.http://www.jstor.org/stable/23217864

Maudlin,D.,&Vellinga,M.(Eds.).(2014).ConsumingArchitecture:Ontheoccupation,appropriation andinterpretationofbuildings.Routledge.109-203

Memmott,P.,&Davidson,J.(2008).ExploringaCross-CulturalTheoryofArchitecture. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review,19(2),51–68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41758527

Mímisson,K.(2016).BuildingIdentities:TheArchitectureofthePersona. International Journal of Historical Archaeology,20(1),207–227.http://www.jstor.org/stable/26174198

Pelt,&Westfall,C.W.(1991).Architecturalprinciplesintheageofhistoricism.YaleUniversity Press.

Seamon,D (2017) Architecture,place,andphenomenology:Lifeworlds,atmospheres,and environmentalwholes Place and phenomenology,247-264

Smith,&Bugni,V (2006) SymbolicInteractionTheoryandArchitecture Symbolic Interaction, 29(2),123–155 https://doiorg/101525/si2006292123

Williams,W A,&Rieger,J (2015) ADesignHistoryofDesign:Complexity,Criticality,and CulturalCompetence RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review,40(2), 15–21 http://wwwjstororg/stable/43632228

12