International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Mohd Faizal Ansari1 , Shiv Kumar2

1M.Tech. (ME) Scholar, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Goel Institute of Technology and Management Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

2Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Goel Institute of Technology and Management Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

Abstract: This study investigates a parallel flow configuration in a three-channel, single-pass corrugated plateheatexchanger. Heatexchangersareengineeredto transmitenergyeffectivelyfromahotfluidtoacoldfluid whilereducingexpenses.

In the experiment, the heated fluid traverses the middle channelwithinlettemperaturesbetween40°Cand70°C, whilecoldwatercirculatesthroughtheupperandlower channels at varying temperatures. Al2O3 nanoparticles areincorporatedintothecoldfluidinvarious quantities to improve performance. The findings demonstrate a 68% enhancement in heat exchanger performance attributable to the use of Al2O3 nanoparticles. The maximal heat transfer rate rises with an increase in the weightpercentageofAl2O3 nanoparticlesinthecoldfluid andtheinlettemperatureofthehotwater.

The research illustrates the capability of Al2O3 nanoparticles to improve the efficacy of a corrugated plate heat exchanger configured in a parallel flow arrangement. The incorporation of these nanoparticles into the cold fluid enhances both the efficiency of the heat exchanger and the peak heat transfer rate. Moreover, the exergy loss is markedly diminished, leading to a more effective heat exchange mechanism. These findings indicate that the incorporation of nanoparticles in heat exchangers may result in significant energy savings and cost reductions across multipleapplications.

Keywords: Corrugatedplateheatexchanger,aluminum oxide nanoparticles, parallel flow, heat transfer enhancement, exergy loss reduction, nanofluid optimization

It is well established that solids generally possess greater thermal conductivity than fluids at standard temperatures. At normal temperature, aluminum's thermal conductivity is 400 times superior to that of water. Consequently, it is anticipated that the

incorporation of solid particles into a fluid may substantially enhance its thermal conductivity. Numerous experimental studies have been conducted in recent decades to examine the potential effects and mechanisms underlying the enhanced thermal conductivity in heat transfer resulting from the incorporationofsolidparticlesintovariousbasefluids.

The resulting fluids demonstrate enhanced heat transfer properties, including elevated convective heat transfer coefficients and thermal conductivity, without significantly altering their physical and chemical features when solid particles are suspended inside them. This significant improvement in heat transmission may result in lower energy and material input, smaller equipment, lower prices, and increased systemefficiencyunderidealoperatingconditions.

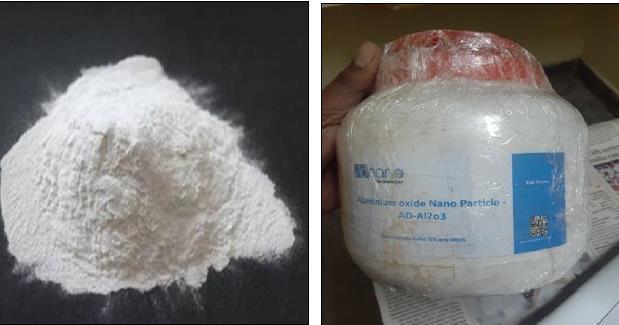

Because of its strong ionic interatomic connections, alumina,sometimescalledaluminumoxide,isamineral with many beneficial qualities. It can exist in severa l crystalline phases at high temperatures, all of which return to the stable hexagonal alpha phase. Being the hardest and most rigid oxide ceramic, this phase is extremelybeneficialforawiderangeofapplications. It is also renowned for having outstanding thermal, refractory, and dielectric qualities. Furthermore, up to 19–25°C, alumina provides protection in oxidizing and reducing conditions. At temperatures between 1700°C and 2000°C, it can also maintain its integrity in a vacuum, with a weight loss range of 10-7 to 10-6 cm2/sec. With the exception of wet fluorine and hydrofluoric acid, it is resistant to all common chemicals and gases. However, especially at lower purity levels, alkali metal vapors might result in hightemperatureattack.Itisfeasibletoimproveavarietyof desiredmaterialqualitiesbyalteringthecompositionof the ceramic body. Solid particles like alumina have demonstrated promise in enhancing heat transfer characteristics in fluids, which could lead to higher efficiency and lower costs in a variety of applications. Additional study and advancement in this area may result in creative approaches to energy conservation andimprovedheattransmissionmechanisms

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

An apparatus that transfers thermal energy (enthalpy) between fluids, between solid surfaces and fluids, or between solid particles and fluids when they come into contactatvarioustemperaturesiscalledaheatexchanger. These gadgets don't need any outside power or labor. They can be used for sterilization, pasteurization, fractionation, distillation, concentration, and crystallization, as well as for heating or cooling fluid streams, evaporating or condensing single or multicomponent fluid streams, and more, depending on the application.

Fluidsinmanyheatexchangersaredividedby a wall ora heat transfer surface rather than coming into direct contact. Indirect transfer type exchangers, also called regenerators,employastorageandreleasemechanismfor sporadic heat exchange, whereas direct transfer type exchangers, also called recuperators, permit direct heat exchangebetweenfluids.

There are several kinds of heat exchangers that can be used in different applications. Shell and tube exchangers are frequently used in commercial and industrial settings totransferheatfromonefluidtoanother.Thermalenergy istransferredfromanenginetotheexternalenvironment by automobile radiators and condensers. Heat is transferred from one medium to another via cooling towers, air preheaters, and evaporators. In applications wherethereisnophasechangeinthefluids,sensibleheat exchangers are employed. Furthermore, certain exchangers might make use of internal thermal energy sources like electric heaters or nuclear fuel components. Lastly, certain exchangers may also use mechanical components such as scraped surface exchangers, agitated vessels,andstirredtankreactors.

Conduction is the main way that heat is transferred through the dividing wall in many heat exchangers. However, with a heat pipe heat exchanger, the heat pipe serves as both a barrier and a conduit for heat transmission, allowing the working fluid to pass through the pipe, evaporate, and condense. Furthermore, the interface between two immiscible fluids can serve as the surface for heat transfer when the separating wall is removedfromdirect-contactheatexchangers.

A thorough examination of heat exchanger performance is necessary to determine the best design and operating parameters.Therefore,developingareliableandaccurate assessment technique is essential. Entropy evaluation techniquesandexergyevaluationtechniquesarethetwo categories into which heat exchanger performance assessmentcriterianowfall.Theratiooftheheattransfer fromonestreamtothemaximumheattransferwithinthe heat exchanger is known as heat transfer effectiveness, and it is another often used statistic for evaluating the

efficiency of two-fluid heat exchangers. However, the efficiencyofheattransferinaheatexchangeronlyshows the relative size of the heat transfer load; it does not reflect the energy transfer burden. The efficiency of heat transfer has nothing to do with the process's energy efficiency. It is commonly acknowledged that a second law analysis is essential to a process's success. To determine the maximum temperature differential betweenthetwofluidstreamsandthegreatestpotential heat transfer from a stream in an ideal two-fluid heat exchanger, a thorough analytical method based on the first and second laws of thermodynamics has been used. Additionally, Srivastava and Ameel presented a new formula for determining the efficacy of ideal two-fluid heatexchangers.

Theamountofenergythat,intheory,candothegreatest amount of work. How much work can be done with a specific amount of energy (converted in a well-defined system), under perfect conditions (using reversible processes), and with just the environment acting as a reservoir of heat and matter. Exergy: The capacity to evaluate energy losses of quality. Although entropy is a very useful metric for assessing and enhancing energy conversion systems, it is not a direct indicator of the quality of the energy. In a language that engineers can comprehend, the quality of energy can be stated as the amount of work that can be produced from a given amount of energy under ideal conversion conditions (using reversible processes). "Exergy" describes this ability to generate work. It's crucial to avoid thinking of energy as a quantity from classical thermodynamics becauseitcomesfromtheapplicationofthermodynamics toenergyconversionsystems.

The fluid flow and temperature distribution in a corrugated plate heat exchanger have been examined using experiments in the present study. The local port temperatureexperimentdescribedherewascarriedoutin an area rather than an idealized plate heat exchanger, in contrast to previous studies. The flow rate in each channel, channel temperature, and pressure drop are computed by keeping an eye on the temperature within the intake and exit ports for the same pipe dimensions at different points. These experiments assess the temperature without affecting the fluid flow in the port. By using this technique, port size and form can also be changed without affecting the plate's characteristics. It is also possible to eliminate other elements from the portto channel flow distribution impact, such as fluid flow, end losses, or improper channel wetting, by using direct experimental measurement. The measurements' findings indicate that the flow distribution is not uniform, fluctuating with flow rate and decreasing with pipe

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

diameter. The resultsclearlyshowhowimportant itis to take flow distribution into account when designing corrugated plate heat exchangers. It is widely used in a wide range of industries, such as the manufacturing of power,food,drink,anddairyproducts;petrochemicaland chemical plants; and automobile radiators. An air conditioning system, for instance, may increase output whileloweringoverheating.

i. To investigate the corrugated plate heat exchanger's performance in a parallel and counterflowconfiguration.

ii. To determine how adding nanofluids to a cold fluidaffectstherateofheattransfer

According toYip etal.(2013),thethermal conductivity of nanofluids is mostly determined by whether the nanoparticles remain distributed throughout the base fluidorformalinearchain.Ithasbeendemonstratedthat the thermal conductivity of nanofluids is significantly impacted by whether the nanoparticles stay scattered throughoutthebasefluid,formlinearchains,ortakeonan intermediate configuration. Strong support for the classical nature of heat conduction in nanofluids is provided by the experimental data, which remarkably resembles that observed in the majority of solid compositesandliquidmixtures.

According to Rao et al. (2014), heat transfer tests are conducted in three distinct kinds of corrugated plate heat exchangers, each of which is 30 cm long and 10 cm wide. Thedistancebetweenthecorrugatedchannelsis5mm.In this experiment, three distinct corrugation angles 300, 400, and 500 are used. The test fluid and the heating medium are both thought to be composed of water. Thermocouples are used to measure the wall temperatures seven times along the heat exchanger's length. Four more thermocouples are used at their intake and exit to measure the temperatures of the hot fluid and testfluid.Thetestfluidisusedforthetestingatflowrates between 0.5 and 6 lpm. The film heat transfer coefficient and Nusselt number are computed using experimental data. Different Reynolds numbers and corrugation angles are used to compare these values. It is described how the corrugationangleaffectstheratesofheattransfer.

The results of an experimental study of the combined energy and performance parameters of the water-using corrugated plate heat exchanger are described by Tiwari et al. (2014). Numerous energetic and exergetic performance parameters have been assessed and their interrelationships have been discussed based on experimental data and accounting for heat exchange with theenvironment.Efficiencyandenergyeffectivenesshave

a general relationship. The outcome demonstrates that while cold side Reynolds number and inlet temperature drop, hot side Reynolds number and intake temperature increase energetic efficiency. The dimensionless energy loss increases as the friction factor and the number of transferunitsgrow.Thestudy'sfindingsdemonstratethat irreversibility is greatly impacted by heat loss and that both the heat effectiveness and the heat capacity ratio have an impact on exergetic efficiency. Numerous links between energy-energy relationships have also been discoveredbasedonexperimentalevidence.

Mohammedetal.(2014)designedagalvanizedironmetal sheet plate type heat exchanger. Three-channel, one-pass plate heat exchangers were used for experiments. The Reynoldsnumberforbothmilkandthecoolingwaterwas setat1666.5.Milk,asa hotfluid,wasmadetoflowinthe central channel to be cooled by water in the peripheral channelsinparallelandcounterflowconfigurations.Inthe counterflow configuration, the average heat transfer coefficient of the milk-water system is 17% greater than thatofthewater-watersystem.

The impacts of chevron angles were examined in a study by Asadi et al. (2014). Here, the pressure drop, friction factor, and heat transfer coefficient are used to assess the thermal-hydraulic capabilities. The results indicate that thefrictionfactorwouldincreaseasthechevronangledid. However, they also show that, for both the laminar and turbulent regimes, the friction factor has an inverse relationship with mass flow rate when the chevron angle is at its optimal value. Lastly, it is demonstrated that 60 degreesistheidealangleforachevron.

Theperformanceofa3channel1-1passcorrugatedplate heat exchanger was examined by Khan et al. (2015). The plates'corrugationanglewas450andtheirsurfaceswere sinusoidally wavy. Water in the outside channels cooled thehotwaterthatflowedinthecentralchannelatvarious inlet temperatures between 400 and 600 degrees Celsius. The Reynolds numbers for both hot and cold fluids fell between 900 and 1300. Parallel and counterflow arrangements were used to measure performance. After calculating the energy loss, it is discovered that the parallel flow arrangement results in a greater energy loss thanthecounterflowdesign.

A three channel one-one pass corrugated plate heat exchangerinparallelflowconfigurationwasthesubjectof anexperimentbyNaseerandRaietal.(2016).Inorderfor the cold fluid in the upper and lower channels to cool the hot fluid, it was created to flow in the center channel at various inlet temperatures between 400 and 600 degrees Celsius.Toimprovesystemperformance,variousamounts ofAl2O3 microparticles wereadded totheheatedfluid. It has been noted that adding Al2O3 microparticles to the heated fluid can increase the heat exchanger's efficiency by50%.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

3.1. Experimental Setup and Procedure

Figure3.1.

A hot water loop, a coolant loop, and a measurement system are all part of the experiment setup, which was built to examine the heat transfer properties of the corrugatedplateheatexchangerchannelforthesameflow condition as illustrated in (figure 3.1). The experiment setup,whichdevelopedathree-ductcorrugatedplateheat exchanger, was constructed from galvanized iron sheet. Both hot water and cold fluid, albeit in different temperature ranges, were employed in the experiment. Cold fluid was used in the first channel, hot water in the middle, and cold fluid in the last. In every case, the temperature (hot and cold water) is installed together with a change in flow direction (parallel flow). The apparatus is made up of two pumps, two tanks that can hold 100 litters of hot water and 50 litters of cold fluid each, an immersion rod that heats the water to different temperatures, rubber pipes that carry the hot and cold water, and thermocouples that measure the temperature at the inlet and outlet of the corrugated plate heat exchanger extremely susceptible to changes in the environment and extremely sensitive to even slight temperature fluctuations. They are made up of two separatemetalwiresjoinedatoneend.Dependingonhow largethetemperaturedifferentialbetweentheendsis,the metal pairproducesa netthermoelectricvoltage between theiropeningand.Aknown-temperaturematerial,suchas ice, is placed on one of the metal connections, while the otherisplacedontheobjectwhosetemperaturehastobe measured following the device's calibration with known temperatures. Using the calibration formula, the voltage provided might be used to determine the item's temperature. Among the many benefits that thermocouples offer are exceptional accuracy and steady performanceoverawidetemperaturerange.Theyarealso helpful for automating precise and affordable measurements. Components of thermocouples are susceptible to corrosion, which could lower the

thermoelectric voltage. Each of the several types of thermocouples has a specific temperature range in which it operates at its peak efficiency. Figure 3.1 displays the experimental setup used to examine the heat transfer properties in the corrugated channel under various flow conditions.

The use of manganese oxide or chrome oxide to change color or harden objects is one example. More changes should be made to enhance the uniformity and simplicity of metal films burned on ceramic for later brazing and soleding. Properties of Al2O3 as an aluminum oxide ceramic One of the most extensively utilized and costeffectivematerialsintheengineeringceramicscategoryis alumina. Using easily accessible and moderately priced raw materials, this high-performance technical grade ceramic is created, yielding fabricated alumina forms that offer outstanding value for the money. It is not surprising thatfinegraintechnicalgradealuminahasawiderangeof fuses given its exceptional mix of qualities and affordable price.Al2O3 isthechemicalformulaforaluminumoxide,an alloyofaluminumandoxygen.Itisthemostcommontype of aluminum oxide and is particularly referred to as aluminumoxide.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net

3.2.1. General information of Aluminium oxide(Al2O3) Nanoparticles

Table 2: General information of Aluminiumoxide(Al2O3) Nanoparticles

DensityNanoparticle

0.1-0.3gm/cm^3

Frompurity 99.98%

Molecularweight 102.96gm/mol

Sizeparticle 30-49.99nm

Meltingpoint 2055oc

CASno 1335-23-.99

Morphology Nearspherical

Colour White

Phase Solid

PowderCrystallographicStructure Rhombohedral

Specificheatcapacity 880J/(Kg-K)

Heatoffusion 10.71kJ/mol

Heatofvaporization 284kJ/mol

3.3. Corrugated Plate Heat Exchanger

Because the corrugated plate heat exchanger performs better and transfers more energy than the parallel plate heat exchanger, it is used in this experiment. When the nanoparticle is added, the hot fluid flows in the midst of these ups, while the cold fluid flows in the higher and lower parts. Through an inlet valve, cold and hot fluid withvaryingtemperatures(40°Cto70°C) wasintroduced into the experiment. The temperature at the outlet was measuredeveryhalfhour. Theoperatingfluidsarewater, both hot and cold. Parallel and counterflow are the two flow topologies that are utilized. Experiments are conductedusing bothconstantmass flow ratesofhotand cold water. The procedure is repeated for more precise results.

p-ISSN:2395-0072

Method of experimentation Both single and hybrid nanofluids have been tested for performance using corrugatedPHE.Thethermalbehaviorofthenanofluidsin corrugated PHE has been described using several test settings. In order to keep the temperature of the channel surfaces somewhat constant, hot water was produced to flowdownthemiddlecorrugatedchannel.Thepurposeof theupperandlowerchannelsistotransportcoldwater.A digital thermometer wire was inserted into the entry and exitsitesofthehotandcoldstreams,respectively,inorder to record the pertinent fluid temperatures. Digital thermometerwirewascalibratedusinganinfrareddigital thermometer and a ZEAL mercury thermometer. Experiments were conducted using hot water in parallel and counterflow configurations with input temperatures of40,45,50,55,60,65,and700C.Thehotandcoldwater flow rates are maintained and the variable differential temperature is consistent for all intake hot water temperaturesinbothparallelandcounterflowsetups.The performance tests have been conducted at three different flow rates between 0.3 and 1.6 LPM, with the mass flow rates of the hot fluid (water) maintained at 0.05 kg/s and 0.16kg/s,respectively. Water,Al2O3/water, beenused in research to determine the effects of using single and hybrid nano fluids on efficiency. To guarantee accuracy, each experiment was also conducted three times. and wereintroducedindifferentweight-basedamountstothe cold fluid, such as 70 g, details of the experimental setup. The test section's length is 100 cm. The test section's widthis10cm.

A flow channel's height, or the space between two successive corrugated plates, is 5 cm. The plate's chevron angleis30°.

Theplate'smaterialisGIof22gauges.

3.4.1. Numerical Methodology-

The experimental data was used to calculate the heat transferrate,

Q=mhCh(Thi-Tho)

Each channel has equal flow area and wetted perimeter givenby,

Ao=H.W,andp=2(W+H)

SpecificHeatcapacityCh=mhcph. Cc=mccpc

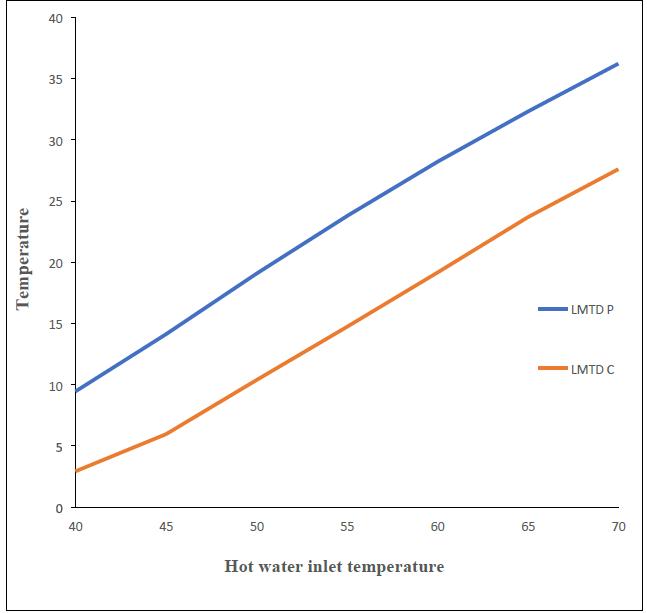

Logarithmicmeantemperaturedifference.

LMTD=[(Tho–Tci)–(Thi-Tco)]]/ln[(Tho–Tci)/(Thi-Tco)]

Effectivenessofheatexchanger,

ε=[Cc(Tco–Tci)]/[Cminln(Thi–Tci)].

International Research Journal of

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net

The exergy changes for the two fluids are obtained as givenbelow,Forhotfluid(i.e.,water),

Eh=Te[Chln(Tho/Thi)]Andforcoldfluid

Ec=Te[Ccln(Tco/Tci)

Exergylossforsteadystateopensystemcanbefoundasa sumofindividualfluidexergy, E=Eh+Ec

3.4.2.

Thehotwatertemperatureismeasuredcarefullybasedon the temperatures of the hot and cold fluids (nano fluid/cold water) at the exit. The technique of heat transfersand energy loss,aswell asthe efficiency of both nano fluids, are estimated. The power supply for water pumping is adequately inspected. Heat transfers in cold andhotfluidsareaccuratelyestimated.

Ithasbeennotedthatpumpingpowersignificantlyrosein accordance with the volume flow rate of nano fluid of water in correctly verified the change in power circumstances.Viscosityhasgrownasaresultofthis.

A three-channel, one-one-pass corrugated plate heat exchanger with a 45-degree corrugation angle is used in the current experiment. In contrast to the center channel's hot fluid flow, the two adjacent side channels weredesignedtoflowcoldfluid. Water isthecomponent of both hot and cold fluids. Aluminum oxide particles are introducedtothecoldwaterfluidtoenhanceheattransfer from the heated fluid to the cold fluid. A temperature reduction in the heated fluid is observed when different concentrations of aluminum oxide particles are added to cold water. shows, in tabular form, the variation in hot fluid outlet temperature at different volume percents of Al2O3 inaparallelflowsystem.

Table4.1 Thermo physical Properties of Aluminium Oxide Water(Al2O3) Fluid

Table4.4Parallel flow (aluminium oxide70gm)

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Table4.5 Counter flow (aluminiumoxide70 gm)

Figure4.1Mass flow rate 0.5 LPM v/s 0.5% volume concentration

Massflowratein0.5lpmtheatdifferentinlettemperature in varies in 550C to 70oC for minimal amount of heat lose and better heat transfer rates in lower temperature difference.

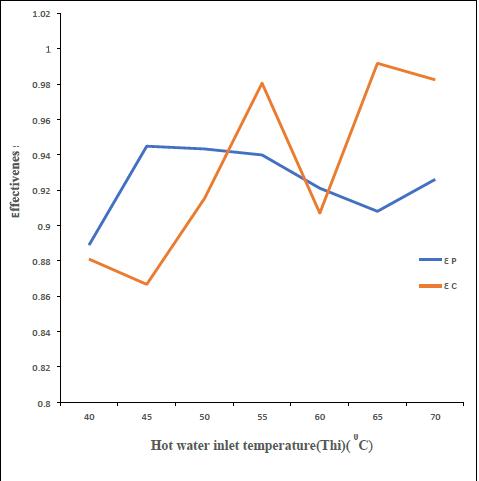

Figure4.2Effectivenessv/s Temperature of hot water inlet

Effectiveness will rise maximum in 500C- 550C in figure 1 the effectiveness will increase in increase temperature. The exergy will be increased in different inlet temperature,forparallelandcounterflowarrangement.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE SCOPE

5.1. CONCLUSIONS

According to the results of the experimental study, aluminum oxide nanofluids have a higher rate of heat transfer than base fluids or coolants. When compared to base fluids from 400C to 700C, the heat transfer rate increases by 36% at a volume concentration of 0.35. The current study's findings about a heat exchanger's performanceareasfollows:

1. The Effect of temp Th1 from 400C to700 C is more significantonthewhenplaincoldwaterisadded.

2. As the volume percentage of Al2O3 increases in cold water at different in let temperature of hot fluid (400C to700C).

3. In the effectiveness are more significant compare to paralleltocounterflowarrangement.

4.Inenergylossarefoundin1lpm.

5.ItobservedthatLMTDofthesystemin83%higherin parallelflowarrangementtocounterflowarrangement.

6. The temperature ranges in 400C -700C. in better performancecorrugatedPHEin550 C–600C.

7. Mixing of nanoparticle in cold fluid increase heat transferratecapability

8.Energyloss increaseswithincreasesinletcold water temperatureforthesameinhotwatertemperature.

9. In the variation of maximum heat transfer rate in corrugated PHE in parallel and counter flow arrangement.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

10. The addition of nanoparticle in the cold fluid reduced the non- dimensional flow energy losses. With increaseinvolumepercentageofnanoparticle.

11. At a nano fluid volume concentration in the use of Al2O3 water nano fluid gives significantly higher heat transfercharacteristics.

12. It is observed that maximum heat transfer rate increases with increase in weight percentage of the nanoparticle in the cold fluid. It is also observed that with rise in inlet hot water temperature, the maximum heat transfer rate increases in counter flow arrangement.

5.2.

Theuseofnanofluidsinthestudyofcorrugatedplateheat exchangers(CPHEs)offersanumberofexcitingdirections for further investigation. Moreover, nanofluids' long-term stability and compatibility with CPHE materials are still crucial for industrial use and demand more research. Efficiency may also be greatly increased by optimizing corrugation geometry and flow configurations using CFD and machine learning techniques. Furthermore, there is a lotofpromiseinapplyinglabresultstoreal-worldsettings in industries like HVAC, chemical processing, and renewable energy systems. For sustainable deployment and commercial viability, cost-benefit analyses and environmental impact assessments of nanofluid-based CPHEs are crucial. The technologies for thermal management in various industries will be improved by theseupcominginvestigations.

1. A Joardar, A.M. Jacobi, (2005). ―Impactofleading edge delta-wing vortex generators on the thermal performance of a flat tube, louvered-fin compact heat exchanger‖, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer,Vol.48,pp.1480–1493.

2. Alvaro Valencia and Marcela Cid, (2002). ―Turbulent Unsteady Flow and Heat Transfer in Channels with Periodically Mounted Square Bars‖, International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, Vol.45,pp.1661-1673.

3. Anema S. G. & McKenna A. B (1996) Reaction kinetics of thermal denaturation of when proteins in heater constituted whole milk. Journal of Agricultural andFoodChemistry44422-428.

4. Arnebrant T., Barton K. & Nylander T (1987) Adsorption of α-lactalbumin and β-lacto globulin on metal surfaces versus temperature. Journal of Colloid andInterfaceScience119(2)383-390.

5. Ashish Kumar Pandey and Basudebmunshi (2011)"A Computational Fluid Dynamics Study of Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer in a Micro channel" national institute of technology, Rourkela Rourkela (Orissa) –769008,India

6. ASME,(1998), ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code, Sec. VIII, Div. 1, Rules for Construction of Pressure Vessels, American Society of Mechanical Engineers,NewYork.

7. Beck, D. S., and D. G. Wilson,(1996). Gas Turbine Regenerators, Chapman & Hall, New York. classification according to heat transfer mechanisms 73

8. Bott T. R.(1993). Aspects of biofilm formation and destruction,CorrosionReviews11(1-2)1-24.

9. Bradley S. E. & Fryer P. J.(1992). Comparison of two fouling-resistant heat exchangers. Biofouling 5 295-314.

10. Britten M., Green M. L., Boulet M. &Paquin P.(1988). Depositformationonheatedsurfaces:effect of interface energetics. Journal of Dairy Research 55 551-562.

11. Burton H. (1967) Seasonal variation in deposit formation from whole milk on a heated surface. JournalofDairyResearch34137-143.

12. Burton H (1968). Deposits from whole milk in heattreatmentplant-areviewanddiscussion.Journal ofDairyResearch35317-330.

13. Butterworth, D., (1996). Developments in shelland-tube heat exchangers, in New developments in Heat Exchangers, N. Afgan, M. Carvalho, A. Bar-Cohen, D.Butterworth,andW.Roetzel,eds.Gordon&Breach, NewYork,pp.437–447.

14. Bylund G. (1995). Dairy Processing Handbook, TetraPakProcessingSystemsAB,Sweden.

15. C. M. B. Russell, T. V. Jones and G. H. Lee (1982).― Heat Transfer Enhancement Using Vortex Generators‖, Heat Transfer Proceedings Of The SeventhInternationalHeatTransferConference,FC50, pp.283-288.

16. Chi-Chuan Wang, Jerry Lo, Yur-Tsai Lin, ChungSzu Wei, (2002). ―Flow visualization of annular and delta winglet vortex generators in fin-and-tube heat exchanger application‖, International Journal of Heat andMassTransfer,Vol.45,pp.3803–3815.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 06 | Jun 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

17. Chien-Nan Lin,Jiin-Yuh Jang, (2002). ―conjugate Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow Analysis in Fin-Tube Heat Exchangers with Wave-Type Vortex Generators ‖,JournalofEnhancedHeatTransfer,Vol.9,PP.123-136.

18. Durmus Aydin, Hasan Gul (2009), ―Investigation of heat transfer and pressure drop in plate heat exchangers having different surface profiles‖ Int JournalHeatMassTransfer2009;52:1451e7.

19. Faisal Naseer and Dr. Ajeet Kumar Rai (2016), ―Study of heat transfer in a corrugated plate heat exchanger using Al2O3 micro particles‖. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology IJMET)Volume7,Issue4,July–Aug2016,pp.189–195, ArticleID:IJMET_07_04_019

20. Fiebig, M. Brocmeire, U Mitra, N. K. and Guntremann, T. (1989). ―Structure of velocity and temperaturefieldwithlongitudinalvortex‖Numerical heattransferpartsa,Vol.15,PP.281-302.

21. Fluent Users Services Center(2006). ―http://www.Fluentusers.com‖.

22. Frithjof Engel, David Meyer and Dr. Susan Krumdieck (2013). "Experimentalcharacterizationof the thermal performance of a Finned-tube heat exchanger "PrivateBag4800,Christchurch8140,New Zealand

23. Fuijta, H. and Yokosava, H., (1984).―The numericalpredictionoffullydevelopedturbulentflow andheattransferinasquareductwithtworoughened facingwalls‖,NagoyaUniversity,Nagoya,Japan.