International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Tatva Kabat¹

1The Academy for Math, Science, and Engineering, Rockaway, New Jersey, USA

Abstract - Incurrentmaterialsscienceresearch,graphene remains at the forefront of current studies due to its potential applications in future healthcare, electronics, and construction industries. This study aims to utilize energy minimization in order to determine stable configurations of monolayer and bilayer graphene, showing that altering atomic properties such as bond length and bilayer gap distance would generate more stable configuration of graphene structures, indicated with minimizing the inner potential energy of each graphene structure. By conducting simulations using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular MassivelyParallelSimulator(LAMMPS),atomicinteractions were modeled within graphene structures (all under the AIREBO potential). Graphene structures were visualized using OVITO and plot data extracted from simulation log files via Python. Simulations were tested with varying bond lengths from 1.20-1.70 Å and bilayer gap distances 2.00 Å and 4.00 Å to observe convergence behavior of the structures as they evolved in our simulations. The results confirmed that the optimal bond length for monolayer graphene is approximately 1.42 Å, while bilayer systems consistently minimizedto an interlayer spacing near 3.48 Å, with those values aligning with existing theoretical and experimental literature. This study aims to show how changes on the atomic level can greatly enhance the stability of graphene structures and its results can be used to optimize graphene for future applications in nanotechnologyandadvancedmaterialsscience.

Key Words: Materials Science, Graphene, Molecular Dynamics, LAMMPS, Energy Minimization

1.INTRODUCTION

Graphene is a single-atom thick sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice, and its physical characteristics such as exceptional electrical and thermalconductivity,mechanicalandtensilestrength,and optical transmittance make it one of the most researched materials in modern materials science [1,2]. The study of theseindividualpropertieshavebeenwidelystudiedsince graphene’sisolationin2004.

Due to graphene’s strong in-plane σ-bonds and delocalized π-electrons, formed as a result of the material’s sp² hybridized carbon atoms, it has broad structuralandelectronicbehavior[1,3].Furthermore,due

to graphene’s high aspect ratio and two-dimensionality, it can also be used as a building block for other carbonbased nanostructures like fullerenes or carbon nanotubes [4]. Graphene’s wide range of applications like highperformance composites and flexible electronics are all rootedinitsatomicconfiguration,whichhasledtovarious research efforts trying to understand graphene’s structuralstabilityundervariousconditions.

As previously mentioned, each carbon atom in a graphene sheet is sp² hybridized, forming three rigid σbonds with adjacent carbon atoms and one π-bond contributing to delocalized electron mobility across the sheet [1,2]. This configuration of atoms creates a symmetricalhexagonallatticecharacterizedbyanidealC–C bond length of 1.42 Å, a value confirmed through both experimental methods and computational simulations [1,5]. The C-C bond length directly affects both the energetic stability of a graphene system and also its mechanical performance, making it a primary target in energyminimizationstudieslikeours[6,7].

Minor deviations from this ideal bond length of 1.42 Å increasesystemenergyduetobondstrain.Defectssuchas Stone–Wales transformations or vacancies in a graphene sheetfurtherelevatesystempotentialenergyanddegrade material properties, often by 4.8–7 eV depending on the defect [4,8]. Edge terminations such as hydrogensaturated edges in graphene nanoflakes help reduce total energy and suppress unwanted mid-gap states, since unsaturated or disordered edges destabilize the structure [6].

These previous research findings show the importance ofatomic-scalefactorssuchasbondlength,hybridization, edge termination, and defects in graphene’s stability. These basic properties establish the energetic foundation for larger graphene systems, like bilayer graphene, where interlayer spacing and sheet orientation create more complexenergeticchallenges.

Bilayer graphene (BLG) introduces more complexity through interlayer van der Waals (vdW) forces, weak attractive forces between atoms close together, and stacking orientation (how layers are stacked on top of each other). Experimental and computational tests have determined the ideal BLG gap to be around 3.35 Å, found

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

in graphite and supported by molecular dynamics (MD) studies using AIREBO and similar force fields [7,9,10]. Precisely controlling this BLG gap in MD studies is necessaryinordertomaximizegraphene’shighelectronic andthermalperformanceduringstudies[11].

Aside from its hexagonal lattice structure, graphene’s properties are also a result of its delocalized π-electron system and the two-dimensional arrangement of its carbon atoms. These characteristics, particularly the delocalized π-electron system, allow for efficient charge transport, thermal conductivity, and mechanical performance in graphene, making it a versatile candidate for next-gen materials [1,2]. One such use comes in graphene’s flexibility and conductivity, fueling its applications in sensors, transparent electrodes, and other optoelectronic technology [2]. Another comes in graphene’s high specific surface area and structural stability under various conditions, making it useful for future supercapacitor and battery electrode development [12,13]

Tofullyunderstandgraphene’senergeticstabilityatthe atomiclevel,especiallywithinBLGsystems,computational molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide both an accurate and alternative approach to experimental trials. Unlike purely analytical models, MD simulations for the tracking of atomic trajectories over time and the analysis of the energy minimization process, lattice changes, and intermolecularinteractionsundervariousmechanicaland thermal conditions. The Adaptive Intermolecular Reactive Empirical Bond Order (AIREBO) potential has become popularinmodelingcarbon-basedmaterialsin particular, as it not only captures covalent bonding, but also nonbonded interactions like vdW forces [5,14]. The AIREBO potential’s ability to simulate both intra and interlayer carbon interactions make it ideal for investigating both monolayer and bilayer graphene systems.

Our study aims to identify energy-minimized configurations of mono- and bilayer graphene by testing varying bond lengths and interlayer spacing configurations in MD simulations. We hypothesized that each graphene system would converge toward a specific structural configuration corresponding to the lowest potential energy, adjusting its atomic characteristics in ordertoreachitsmoststablestate.Ourresultsconfirmed theatomicpropertiesofgraphenesuchasanapproximate 1.42 Å C-C bond length and a 3.48 Å BLG gap distance, demonstrating that graphene's stability can be computationally verified and optimized. Along with its discoveries, the results of our study could provide important insights for the continued development of graphene-based materials in nanotechnology and advancedengineeringapplications.

AllMDsimulationsforourtrialswereperformedusingthe LAMMPS software package. Input script files, atomic data files,andtheAIREBOpotentialfileswereprovidedbyNJIT researchers.ForThesimulationsmodeledbothmonolayer and bilayer graphene and data files were generated/modified using MATLAB. All simulations utilizedthe“metal”functionforunitsinLAMMPStoreport energy in eV, distance in Å, and time in picoseconds with the function being common for MD simulations involving carbon-basedmaterials.The boundarywassettothe“p p p”functionandwasusedtocreateperiodicboundaries in all directions (x,y,z). Finally, the atom style was set as “atomic” to specify that each atom had no charge or intrinsic attributes aside, ensuring normal carbon atoms wereusedforeachtrial.

Forthemonolayertrials,sheetsof400carbonatomswere generated each with varying x and y positions based on thebondlengthofthetrial.Zpositionswerekeptconstant to maintain two-dimensionality. Each simulation was run for 10,000 timesteps, and atomic positions as well as thermodynamic properties for the sheet were updated every100stepsinthelogfile.

For the bilayer trials, two sheets with 100 carbon atoms each were generated with x and y positions of two atoms being identical for the stacking of the sheets in an AA format. The z positions of each sheet were varied depending on the initial BLG gap distance. The AIREBO potential was applied using the “pair_style airebo” and “pair_coeff” commands to model the interatomic forces and weak van der Waals interactions accurately. For the simulations, the simulation box was made flexible using the“box/relax”fixtoallowforout-of-planerelaxationand to minimize internal stress without applying external pressure. A variable was defined to track the minimum and maximum z-positions of all carbon atoms, and a custom “thermo_style” output was used to monitor the system’s potential energy, temperature, and vertical (zdirection)gapduringeachrun.

To visualize both the monolayer and bilayer structures, the .cfg files from each simulation were input into the OpenVisualizationToolsoftware(OVITO).OVITOallowed for the visualization of the dump data from the LAMMPS trials, and playing through the .cfg files showed the expansion/compression of bond lengths and BLG gap distanceinthestructures.

Graphs for each trial were generated by extracting the data from the .log files generated by each LAMMPS trial.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET)

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net

Python scripts were run on VS Code with the OS, NumPy, and Matplotlib libraries in order to graph trends.For the monolayer trials, data extracted from the .log files from the energy minimization and dynamic bond length relaxation trials was plotted to generate potential energy (eV) vs bond length (Å) and bond length (Å) vs. step graphs.Similarly,forthebilayertrials,dataextractedfrom the .log files from the energy minimization and convergence analysis trials were plotted to generate potential energy (eV) vs. bilayer gap distance (Å) and bilayergapdistance(Å)vs.stepgraphs.

All scriptsandsimulationfilesusedforourresearchhave been uploaded to GitHub and are accessible to replicate ourresultsat:

https://github.com/tatvakabat/A-Molecular-DynamicsStudy-of-Energy-Minimization-in-Mono and-BilayerGraphene-Structures

2.3

To test our hypothesis, we conducted various energy minimization trials of both monolayer and bilayer graphene systems, setting initial characteristics such as bond length and BLG gap distance and allowing each system to relax towards its most stable configuration, minimizingthepotentialenergyofthesystem.

Toidentifythemostenergeticallyfavorablebondlengthin a monolayer graphene sheet, a series of energy minimization trials were conducted in LAMMPS. The Adaptive Intermolecular Reactive Empirical Bond Order (AIREBO) potential was selected to model covalent C–C bonding and nonbonded interactionswithin the graphene lattice. Structures were initialized with varying bond lengths, with a fixed z-coordinate for two-dimensionality, between 1.20 Å to 1.70 Å, and the system was allowed to relax under a convergence tolerance of 1e-8 for energy and1e-9forforce.

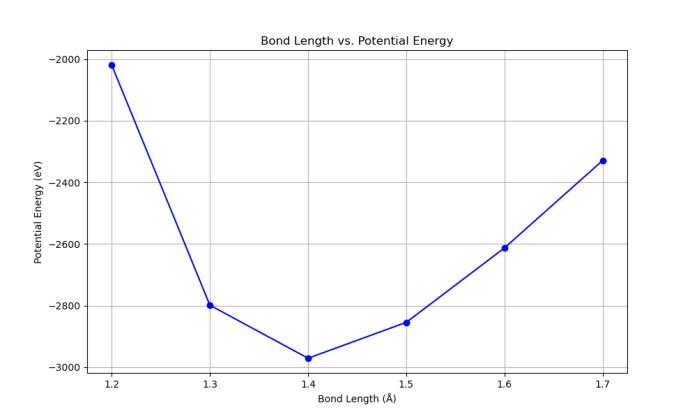

The resulting potential energy values from each structure after every trial was plotted as a function of bond length, with the potential energy steeply decreasing from 1.20 Å, reaching a minimum near 1.40–1.42 Å before increasing again at longer bond lengths (Chart 1). This parabolic energy profile reflects the balance between repulsive interactions at short distances and weakened bonding at extendeddistanceswiththeminimumindicatingthebond length at which the system reaches its most energetically favorableandstableconfiguration.

e-ISSN:2395-0056

p-ISSN:2395-0072

1: Potentialenergyvs.bondlengthinmonolayer graphene

Toverifytheexperimentalbondlengthof1.42Åidentified in the static energy minimization trials, we performed dynamic bond length relaxation simulations using LAMMPS. Starting once again from initial bond lengths of 1.20-1.70 Å (in 0.1 Å increments), each graphene sheet was put into a molecular dynamics relaxation simulation over time. The AIREBO force field was once again used to model for realistic C–C bonding behavior, while interatomic interactions were updated dynamically as the systemevolvedtowardequilibrium.

During each simulation, the system was allowed to relax under the NVE ensemble (constant number of particles, volume,andenergy),within-planeboxrelaxationenabled in the x and y directions, allowing the lattice itself to contract or expand in response to internal stress from non-equilibriumbondlengths.Atomicpositionsandother properties (pressure, potential energy, bond distances) weretrackedineachsystematregularintervals.

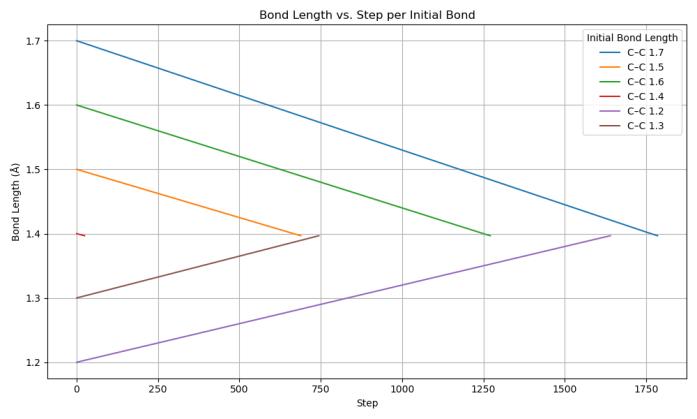

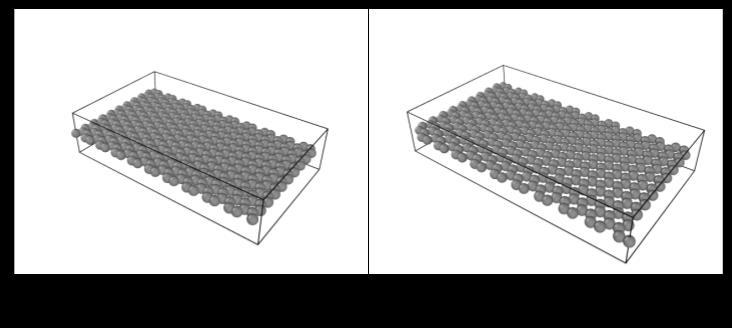

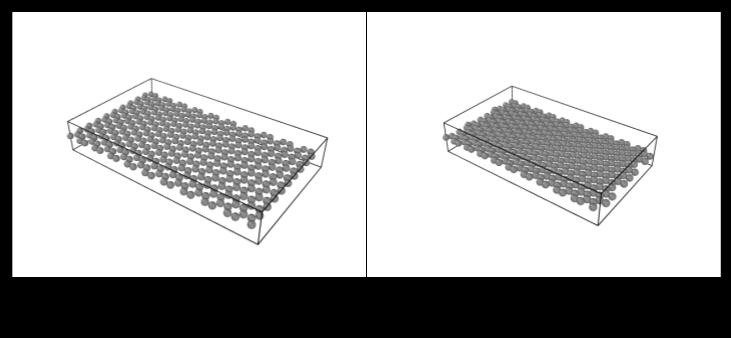

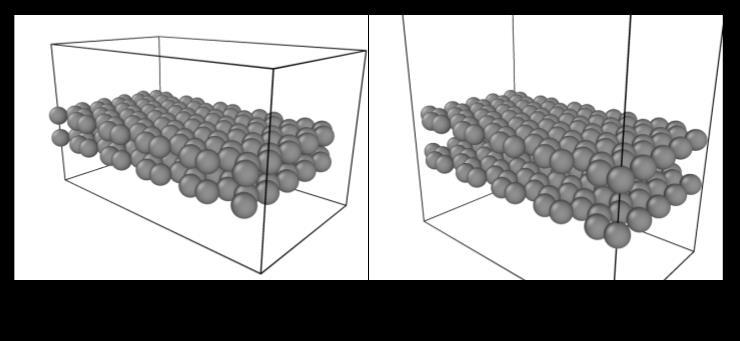

The changing of bond lengths over simulation steps demonstrates clear convergent behavior across all initial configurations towards graphene’s ideal bond length of 1.42Å(Chart2).WhenvisualizedinOVITO,thesheetwith a starting bond length of 1.20 Å expanded towards the ideal bond length of 1.42 Å (Figure 1). Similarly, for the starting bond length of 1.7 Å, we saw the compression of carbon atoms in the graphene sheet to reach the ideal bond length of 1.42 Å (Figure 2). This behavior in both sheets confirms that graphene’s bonding energetics favor this equilibrium spacing, where internal stress is minimizedforastablestructure.

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Chart 2: Bondlengthrelaxationduringenergy minimization

Figure 1: Expansionofmonolayergraphenefroma compressedstate(1.2Å)

Figure 2: Compressionofmonolayergraphenefroman extendedstate(1.7Å)

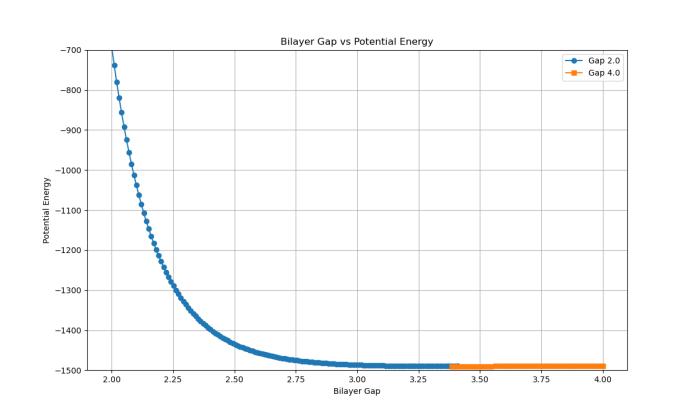

To find the BLG gap distance that corresponded to the most energetically favorable state, similar energy minimization simulations were once again conducted using LAMMPS, this time using BLG structures. Two graphene bilayer systems were initialized with gaps of 2.00Åand4.00Åbetweenthegraphenesheets,chosento evaluate convergence from both compressed and extended starting geometries. The AIREBO potential was usedto account for covalent intralayer bondingand weak interlayervanderWaalsinteractions.

During our energy minimization trials, both systems converged to similar final potential energies of

© 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 |

approximately –1490 eV, despite beginning at different energy states (Chart 3). The system initialized at 4.00 Å began at a lower potential energy (–1488 eV), while the 2.00Åsystemstartedata muchhigherenergy(–700 eV), due to interlayer compression and increased repulsion, and by the end of the simulation, both structures approached an interlayer spacing near 3.40–3.50 Å, confirming this range as the energetically minimized configuration(Chart3).

Chart 3: Potentialenergyconvergenceinbilayergraphene withdifferentinitialgaps=

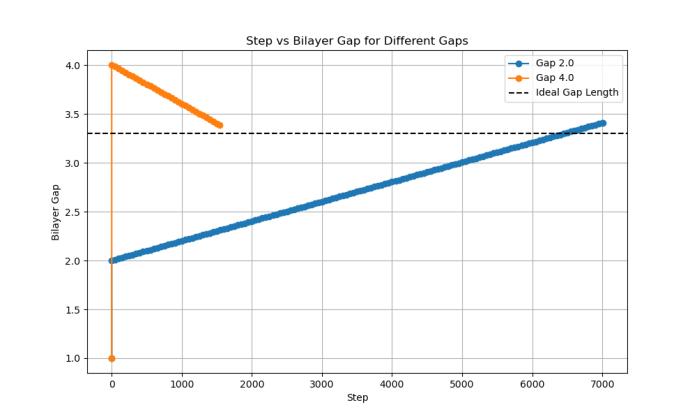

Similar to the monolayer trials, a convergence analysis was used to confirm the ideal bilayer spacing observed in the energy minimization trials, tracking the BLG gap over thecourseofthesimulation steps.TwoBLGsystems with initialverticalgapsof2.00Åand4.00Åweresimulatedto determine how each structure changed as it approached equilibriumspacingundertheAIREBOpotential.

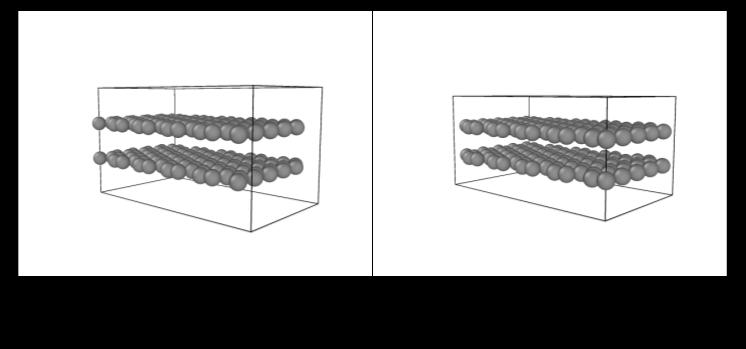

Both systems dynamically adjusted their interlayer spacingandultimatelyconvergedtowardacommonvalue of approximately 3.40 Å, consistent with the energy minimizationresults(Chart4).Thestructureinitializedat 4.00Åbegan closer tothis equilibriumvalueandreached it significantly faster. In contrast, the 2.00 Å system required ~5,000 additional steps to reach the same final spacing, due to its initially compressed configuration and higher potential energy (Chart 4). This was once again consistentwiththeenergyminimizationtrial,astheinitial 4.00Ågapwasmuchclosertotheequilibriumgapof3.40 Å (0.60 Å off equilibrium) compared to the initial 2.00 Å gap(1.6Åoffequilibrium).

OVITO was used again to visualize these simulations, and forthetrial witha starting BLGgapof2.00Å,wesawthe expansion of the gap between the graphene sheets due to interlayer compression which caused repulsive forces to pushthesheetsapartfora morefavorableenergeticstate (Figure 3). For the simulation with a starting BLG gap of 4.00Å,wesawthecompressionofthesheetsviaattractive forces to reach the most energetically favorable state in thestructure(Figure4). International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

4: Bilayergaprelaxationoversimulationsteps

Figure 3: Expansionofbilayergraphenefromaninitial 2.0 Ågap

Figure 4: Compressionofbilayergraphenefromaninitial 4.0 Ågap

3. CONCLUSIONS

Our study’s goal was to determine the most stable atomic configurationsofmonolayerandbilayergraphenethrough energy minimization in MD simulations. We hypothesized thatforeachstructure,therewouldbeaspecificC-Cbond lengthandBLGgapthatminimizedthepotentialenergyof the systems, and that simulations would naturally reach these values to stabilize the structure. The data from our monolayer trials confirmed that a bond length of 1.42 Å was consistently reached regardless of initial configuration, supporting our hypothesis and aligning with previous studies. Similarly, our bilayer graphene systemsinitializedatboth2.00Åand4.00Ågapsrelaxed

toward an interlayer spacing of approximately 3.40- 3.50 Å, once again validating our assumption that structural stabilitycorrespondstoenergyminimizationandfallingin linewithexistingliterature.

The results of our study show the direct relationship between graphene’s structural stability and its internal energy,dependentonthestructure’satomicproperties.In the monolayer trials, energy minimization simulations resulted in a parabolic trend in potential energy, with a minimum occurring at a bond length of approximately 1.42 Å. This value aligns closely with established theoreticalandexperimentalstudies,confirmingthateven small deviations from the equilibrium bond length (indicated by the 0.10 Å incremental changes) result in substantial increases in system energy due to internal bond strain [1,5]. These findings also reflect the observationsofstrongσ-bonddominanceanddelocalized π-electron behavior that stabilize graphene’s hexagonal lattice[2].

Our BLG simulations similarly demonstrated that interlayergapdistanceplaysacriticalroleindetermining total system energy. Structures initialized at 2.00 Å and 4.00 Åbothrelaxedtowardanequilibriumgapof~3.40 Å, avaluesupportedbypriorliterature[9].Interestingly,the system initialized at 4.00 Å not only started closer to this valuebutalsoreachedconvergencefasterthanthesystem initializedat2.00 Å,suggestingthatasmalldeviationfrom equilibrium in either direction influences both initial energetic favorability and the speed of structural relaxation. These trends once again prove the importance of atomic arrangement in maintaining low-energy, stable graphene configurations. Furthermore, the importance of the initial gap distance on how the structure evolved is supported by high-velocity impact simulations, where even small changes in stacking geometry significantly impact dynamic response and energy absorption [8]. These similarities reinforce the understanding that atomic-scale arrangement in both in-plane and interlayer geometry is necessary in creating energetically favorable graphenesystems.

Although ourstudysuccessfully identifiedideal structural configurations in monolayer and bilayer graphene, our results were limited in some regards. All of our simulationswereperformedusingideal,puregrapheneat 0 K, without incorporating temperature fluctuations, external forces, or defects in modified structures that can occur in the real world. Additionally, all simulations were carried out using the AIREBO potential, which while widely used, has known limitations in modeling longrange London dispersion forces and can oversimplify certain external interactions in bilayer systems. Future research in the field may benefit from hybrid or alternate force fields for more accurate results, especially in BLG systems. Another limitation was the scope of BLG

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

configurations tested. Our study also only utilized AAstacked bilayer configurations, whereas AB or twisted bilayers can display different energetic behavior. Finally, although our research examined structural relaxation under energy minimization, it did not explore timedependent changes or deformation under strain, which are essential in many engineering applications for graphene.

Despite these limitations, the findings of our research contribute valuable data to the growing understanding of graphene's structural energetics. The results of our study provideanunderstandingintothebehaviorofgrapheneat the atomic level and its stability under various atomic conditions. By computationally verifying the bond length of ~1.42 Å and bilayer gap of ~3.40 Å as energetically favorable configurations, our results reinforce discoveries for the development of future graphene-based materials. These figures not only align with experimental data and prior literature but also provide tested parameters for future trials in materials design and MD simulations, particularly for applications requiring structural stability such as sensors, nanoelectronics, or composite reinforcement.

In BLG systems, the importance of initial configurations forefficientconvergencetowardminimum-energyspacing could prove important in future studies of BLG, where layerdepositionorintercalationplaysacrucialrole.These insights strengthen the foundation for applying graphene inadvancedtechnologiesandcontributetoongoingefforts to implement its unique properties into future technologiesinaerospace,medicine,andelectronics.

Through the findings of our study, we were able to demonstrate that energy minimization is an effective method for identifying optimal bond lengths and interlayer spacings in graphene systems. This research supports the continued use of MD simulations in atomicscale materials design and encourages further investigations that include defects and alternative structures to more accurately represent real-world materials.

I would like to acknowledge my mentors, Professor Dibakar Datta and PhD candidate Rumana Hasan at NJIT for guiding me through the research process and providing support whenever I encountered hardship. Their support and guidance was vital in my research process,andIthankthemforalltheirhelp.

[1] S.K. Tiwari, S. Sahoo,N. Wang,A.Huczko,“Graphene research and their outputs: Status and prospect,”

Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, vol. 5, March 2020, pp. 10-29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsamd.2020.01.006.

[2] A. R. Urade, I. Lahiri, K. S. Suresh, “Graphene Properties, Synthesis and Applications: A Review,” JOM, vol. 75, October 2022, pp. 614-630, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-022-05505-8

[3] T. Luo, Q. Wang, “Effects of Graphite on Electrically Conductive Cementitious Composite Properties: A Review,” Materials, vol. 14, August 2021, pp. 4798, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14174798

[4] R. Soave, F. Cargoni, M. I. Trioni, “Thermodynamic Stability and Electronic Properties of Graphene Nanoflakes,” C, vol. 10, January 2024, pp. 5, https://doi.org/10.3390/c10010005

[5] G. Yang, L. Li, W. B. Lee, M. C. Ng, “Structure of graphene and its disorders: a review,” Science and technology of advanced materials, vol. 19, Aug. 2018, pp. 613-648, https://doi.org/10.1080/14686996.2018.1494493

[6] T. Yusaf, A. S. F. Mahamude, K. Farhana, W. S. W. Harun, K. Kadirgama, D. Ramasamy, M. K. Kamarulzaman, S. Subramonian, S. Hall, H. A. Dhahad, “A Comprehensive Review on Graphene Nanoparticles: Preparation, Properties, and Applications,”Sustainability, vol.14,September2022, pp.12336,https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912336

[7] A. E. Galashev, O. R. Rakhmanova, “Mechanical and thermal stability of graphene and graphene-based materials,”Physics-Uspekhi,vol.57,October2014,pp. 970-989

https://doi.org/10.3367/ufnr.0184.201410c.1045

[8] Y. Qiu, Y. Zhang, A. S. Ademiloye, Z. Wu, “Molecular dynamics simulations of single-layer and rotated double-layer graphene sheets under a high velocity impactbyfullerene,”ComputationalMaterialsScience, vol. 182, September 2020, pp. 109798, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.109798

[9] Y. Huang, X. Li, H. Cui, Z. Zhou, “Bi-layer Graphene: Structure, Properties, Preparation and Prospects,” Current Graphene Science, vol. 2, 2018, pp. 97-105, https://doi.org/10.2174/2452273202666181031120 115.

[10] P.He,Y.Zhang,Z.Wang,P.Min,Z.Deng,L.Li,L.Ye,Z. Yu, H. Zhang, “An energy-saving structural optimization strategy for high-performance multifunctionalgraphenefilms,”vol.222,March2024, pp. 118932, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2024.118932

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

[11] N. R Abdullah, H. O. Rashid, C. Tang, A. Manolescu, V. Gudmundsson, “Role of interlayer spacing on electronic, thermal and optical properties of BNcodoped bilayer graphene: Influence of the interlayer andtheinduceddipole-dipoleinteractions,”Journalof Physics and Chemistry of Solids, vol. 155, August 2021, pp. 110095, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110095

[12] P.K.Sahoo,N.Kumar,A.Jena,S.Mishra,C.Lee,S.Lee, S. Park, “Recent progress in graphene and its derived hybridmaterialsforhigh-performancesupercapacitor electrodeapplications,”RSCAdvances,vol.14,January 2024, pp. 1284-1303, https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RA06904D.

[13] N.Mushahary,A.Sarkar, F. Basumatary,S.Brahma,B. Das, S. Basumatary, “Recent developments on graphene oxide and its composite materials: From fundamentals to applications in biodiesel synthesis, adsorption, photocatalysis, supercapacitors, sensors and antimicrobial activity,” Results in Surfaces and Interfaces, vol. 15, May 2024, pp. 100225, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rsurfi.2024.100225

[14] C. P Herrero, R. Ramírez, “Elastic properties and mechanical stability of bilayer graphene: molecular dynamicssimulations,”TheEuropeanPhysicalJournal B, vol. 96, November 2023, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/s10051-023-00616-w.

[15] Z.Wang,H.Zhang,X.Sun,Y.Huo,“Moleculardynamics studyonthemechanicalbehaviorofverticallyaligned γ-graphdiyne-graphene heterostructures under tension,” Materials Today Communications, vol. 37, December 2023, pp. 107465, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107465

[16] Y. Zhang, Y. Qiu, F. Niu, A. S. Ademiloye, “Molecular dynamicssimulationofperforationofgrapheneunder impact by fullerene projectiles,” Materials Today Communications, vol. 31, June 2022, pp. 103642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103642.