23 minute read

l Presenting the past: evaluating archaeological exhibitions in museums in the Republic of Ireland

from Museum Ireland, Vol 24. Lynskey, M. (Ed.). Irish Museums Association, Dublin (2014).

by irishmuseums

Presenting the past: evaluating archaeological exhibitions in museums in the Republic of Ireland

DONNA GILLIGAN

Advertisement

1.This research was undertaken as part of a Master’s thesis in Museum Practice & Management completed at the University of Ulster in 2013. Thanks are due to my supervisor, Dr Elizabeth Crooke, for her guidance and support throughout my studies.

Introduction1

Museum exhibitions are one of the primary and most effective forms of communicating archaeological information to the public. Exhibitions have slowly evolved from their traditional style of object-led, curatorially biased formats towards a reconsideration of the way in which artefacts are displayed and interpreted, and the audiences for whom this is carried out. The display of archaeology in museums presents a number of challenges, as prehistory is a complex, heavily layered subject, which ideally requires careful and well deliberated means of display and interpretation in order to fully present its value, interest and importance to the public audience.

New and exciting exhibition styles which maintain intellectual integrity while banishing the stereotypical stigma of elitist academic museum institutions are important in order to serve the needs and interests of the public and maintain a sustainable position in modern society. This research article is the outcome of an evaluation of the range, methods and diversity of current Irish archaeological exhibitions. using the archaeological exhibitions on display in the Republic of Ireland, this research examined the presence of innovative, creative and well developed exhibit formats which have replaced the traditional archaeological display style of cases, labels and chronology. Research explored and assessed a number of exhibition components and techniques which have been subject to change, development and debate within the wider museum archaeology sector throughout the uk and Europe.

Research has uncovered a need for re-assessment and revitalisation of the ways in which archaeological collections are exhibited in the Republic of Ireland. Archaeological exhibitions which present clear aspects of innovation and development within their formats are unfortunately limited, and a number of institutions would benefit from

2. Stone, P.G. (1994) The redisplay of the Alexander Keiller Museum, Avebury, and the National Curriculum in England. In Stone, P.G. and Molyneaux, B.L. (eds) The Presented Past: Heritage, Museums and Education Routledge Press, London, 190205. 3. Cotton, J. (1995) Illuminating the twilight zone? The new prehistoric gallery at The Museum of London. In Denford, G.T. (1995) (ed.) Representing Archaeology in Museums. Society of Museum Archaeologists Conference Proceedings. Museum Archaeologist, Volume 22, pp. 612. a form of exhibition evaluation and an assessment of their communication methods. The exhibition examples discussed here are not intended to highlight instances of best practice, but instead act as samples of institutions engaging with the concepts of innovation and development in their exhibitions.

Museum archaeological exhibitions

It is an unfortunate common issue that archaeology is often poorly communicated by its practitioners to a misunderstood public audience, resulting in incomprehension and boredom. Archaeology has previously tended to be quite traditional in its display style, focusing on the conventional pattern of artefacts in glass cases accompanied by text-heavy labels. It has been demonstrated that archaeological exhibitions in museums have often failed to improve public knowledge and awareness of the ancient past.

Visitor surveys carried out at the Alexander keiller Museum in Avebury, Wiltshire2, and at The Museum of London3 found that the public held little detailed understanding of chronological periods, and that their knowledge was skewed by generalisations and misconceptions. Research into visitor attendance in this sector has also found that the public had a poor expectation of enjoyment from archaeological exhibitions, and that visiting museum exhibitions did not feature in a high position on a list of ways in which people preferred to engage with the past3. Innovation, progress and development of archaeological exhibition styles and methods are crucial in order to create effective public learning, interest and engagement. Archaeological museums have previously suffered for their traditional exhibition methods and curatorial, academic-centred approach to interpretation and display.

Theorists have demonstrated that the potential for learning in museums is abundant. Advancements in the understanding and application of learning theory have hugely influenced and developed exhibition styles in the museum sector over the past twenty years. While traditional exhibition styles focused mainly on the basic transference model of learning through labels and display panels, the museum sector today embraces advanced active, constructivist and participatory models of learning within their exhibition methods.

Archaeological exhibitions are a common feature of the majority of museum galleries in the Republic of Ireland. For the purposes of this research, attention was focused on institutions with larger permanent display collections, as they would have more opportunity and potential to display aspects of creativity and development within their exhibitions. Research visits were carried out during a period between October 2012 and May 2013. Visits were carried out to all of the museums with designated status, with the exception of Limerick City Museum, closed during this research period. The research criteria also highlighted a need for inclusion of the Hunt Museum in Limerick city, Carlow County Museum, and The National Museum of Ireland –Archaelogy. An additional research visit was carried out to the ‘Dublinia’ institution in Dublin city, based on its inclusion of a permanent gallery of archaeological finds, and its year-round accessibility in contrast with the traditions of national heritage centres.

Evaluating archaeological exhibitions

For the purposes of this paper, evaluation of innovation and development has focused on a number of common exhibition constituents which have undergone notable change and development within the wider museum archaeology and exhibition sectors over the past twenty years. These include the aspects of chronology and the presentation of time, text and labels, interpretation, multisensory exhibition elements, the use of models, replicas and reconstructions, and the use of wider contextual explanation – in this case, the presentation of the work of the archaeologist. One of the recommended effective ways for an exhibition to establish the links between objects and their contexts is to present public discussion of the work of the archaeologist. This serves to present the full background of the displayed objects, as well as the validity and emerging results of the living archaeological profession.

Evaluation was grounded in a framework guided by critical discussion by three prominent museum archaeologists – Susan Pearce, Graham Black and Hedley Swain – as well as through current exhibition best practice standards and appraisal of the application of effective learning theory. Appraisal of exhibition developments in the wider u.k. and European museum archaeology sector provided comparative references

which demonstrated former and ongoing experimentation and advancements with the highlighted exhibition constituents, as well as discussion on their effectiveness and suitability. Overall, evaluation involved the assessment of any significant aspects of change which deviated from traditional archaeological display patterns of cases, labels and chronology, as well as from an emphasis on didactic academic interpretation.

Research results and discussion: chronology and the presentation of time

Fig 1. ‘Power’ colour-coded themed gallery in Clare County Museum. Author’s images. With the exception of a small number of institutions, research has shown that Irish archaeological exhibitions mainly still adhere to the traditional chronological format of display. Museums have habitually presented archaeological displays within the format of a chronological timeline or gallery pattern, beginning with prehistory and ending in the late medieval or post-medieval period. A small minority of the research examples use a thematic style in replacement of a chronological one, which evaluates artefacts from differing periods through discussion of a common topic. As an example, Clare County Museum presents its varied collections through dialogue relating to four overall themes –Faith, Power, Earth and Water.

The traditional chronological display format has recently been challenged, with some archaeological exhibitions abandoning these restraints, and instead engaging with a thematic display format. The use of a thematic style has proven to be a successful and innovative method, as studies have shown that comprehension of the distant past for the visitor requires a link to their own lives in order for it to be fully understood. Combination of this non-traditional format with the limited inclusion of a chronological display can provide a touchstone for detailed understanding of the thematic displays, without presenting an overwhelming style which removes the human aspects represented in the themes and resorts to unimaginative classification and order. Experimentation with the presentation of time could potentially lead to a greater public appreciation and understanding of the past through themes, ideas and stories.

4. Lack, G. (2008) A meaningful connection to the past demands active engagement: an interpreter’s thoughts on the display of archaeology. In Swain, H. (ed.) (2008) Presenting the Past. Museum Archaeologist, Volume 31.

Text and labels

Research has shown that the majority of Irish archaeological exhibitions maintain traditional label styles and formats. Artefact labels tend to deal simply with basic object identification, and display panels present didactic text-heavy summations of chronological periods. Many text examples also still rely on the use of specialist terms and artefact classifications, which largely do not translate well to a general nonspecialist audience. A small selection of the research group showed experimentation with the provision of different levels of information for different ranges of visitor type – such as the flip label trail specifically for children used by kerry County Museum.

The importance of engaging, understandable labels and effective communication methods remains an important issue within exhibition comprehension and enjoyment4. Labels accompanying archaeological displays have previously been written by curators, but it is now widely recognised that text and labels should ideally be composed by a professional with advanced knowledge of communication styles, who can produce engaging, understandable and non-specialist text. Experimentation in the use of theoretical discussion, contextual images and discursive engagement with the visitor through text and labels may further serve to revitalise this component of Irish archaeological exhibitions.

Interpretation

Interpretation remains an issue of high importance and ongoing debate within archaeological exhibitions. Research visits have revealed an overall lack of engagement with academic discussion and theory within the interpretation of prehistoric material displayed in Irish archaeological exhibits. In the majority, interpretation is of a didactic, reserved nature which informs the visitor rather than actively engaging them in thought and debate. With the exception of a small number of examples, examination has also revealed that the role of human involvement in the display of prehistoric artefacts is still a muted and poorly referenced subject. The isolation of displayed objects from their human origins results in object-led displays, with a lack of public connection and appreciation of the artefacts as examples of human craft and ability. The avoidance of discussion and refusal to deal with the subjects of the unknown stalls the development of these exhibitions and help to propagate the preconceptions and stereotypes of the prehistoric

5. Serrell, B. (1996) Exhibit Labels: An Interpretative Approach, Altamira Press. period as one devoid of life, humanity and progress. Research suggests that the ongoing need for museum professionals to talk with visitors rather than at them still appears to be a contentious issue in current archaeological exhibitions in the Republic of Ireland.

The ongoing need for museums to develop from the image of hallowed temples of didactic knowledge into public forums for debate and discussion has been well recorded5. The exhibition of prehistory presents an ongoing challenge for curators and museums. Due to the absence of interpretative certainty and a limited range of material remains, prehistoric exhibitions have often suffered in their display and interpretation. This has resulted in prehistoric material culture becoming unimaginatively displayed and showing traditional chronological and artefact classification presentations that are static and limited in their approach. They often exclude the interpretation of intangible and unknowable elements such as societal norms, gender roles and religious beliefs due to a reluctance to participate in theoretical engagement, and a hesitancy to expose the gaps in archaeological knowledge. Museum visitors hold an inherent interest in the presentation of people, particularly in that of individuals like themselves, with a specific interest in accessible similarities such as social constructs and daily life. With the absence of additional research resources such as a written record, it is the duty of the archaeologist to suggest theories which fit the evidence of the extant material remains.

Curatorial staff have previously been reluctant to engage with the process of open interpretation, preferring to maintain a safer, conservative and traditional method. Museums are also slow to surrender their traditional image as places of academic authority and didactic learning in return for their admittance of curatorial doubt and presentation of views which challenge their established knowledge. Their attitudes may reflect a fear of a descent towards relativism through engagement with this form of interpretation. This reluctance for exhibit development and innovation can be said to have contributed to poor public preconceptions of prehistory and a general disinterest within this chronological period, compared to those with better surviving material remains and more engaging and informative interpretation.

However, the uncertainty and theoretical possibilities of the prehistoric past actually provides the opportunity for the museum to actively

engage the visitor in ongoing academic discussion and theory regarding several aspects of prehistoric life, transforming their role as a passive consumer into an active participant. It is important to maintain that the prehistoric exhibitions displayed by museums are only interpretations of this chronological period rather than an accurate representation of the past. Thus, there always remains a gap in our archaeological knowledge, and a need for the use of creative theory to explain our material evidence. One of the main ways that the visitor can be engaged and intellectually provoked is through the discussion of academic theory in exhibition interpretation. The use of open-ended possibilities and the admission of ignorance or conflicting theories have previously been found to be a popular approach with visitors, giving a sense of validity to their own opinions.

Multisensory exhibition elements

Very few Irish archaeological exhibitions engage the use of multisensory components. A small number experiment with tactile, auditory and olfactory senses, but these institutions are very much a rarity. kerry County Museum and Dublinia both use a combination of these multisensory styles to provide an immersive medieval life experience within their galleries, experimenting with sound, smell and touch in their exhibits.

The aspect of multisensory stimulation in Irish archaeological displays remains underutilised and provides wide-ranging potential for exhibition innovation. Research and practice related to the addition of multisensory experiences within exhibitions have proven to heighten visitor accessibility, improve experience and understanding, and enhance learning possibilities6. The engagement of additional senses such as touch, smell and sound provide a multi-layered exhibition experience for the visitor, and offers a more engaging and understandable context for learning.

Fig 2. Multisensory immersive reconstruction in ‘The Medieval Experience’ in Kerry County Museum. Author’s images.

6. Merriman, N. (2000) The crisis of representation in archaeological museums. In McManamon, F.P. and Hatton, A. (2000) Cultural Resource Management in Contemporary Society – Perspectives on managing and presenting the past, Routledge Press, London and New York, pp. 301-309.

Contextual exhibition elements – presenting the work of the archaeologist

Only a small number of permanent archaeological exhibitions in the Republic of Ireland give prominence to presentation of the work of the archaeologist in their galleries. Despite the excellent potential of archaeological practice for use in effective hand-on media, this is also not an element commonly employed within current Irish museum displays, and is used within only three permanent archaeological galleries in the author’s research group of museums.

For several years the role and work of the archaeologist have remained absent from the museum exhibition. Artefacts were displayed with the presumed assumption that the museum visitor would possess an already implicit knowledge that they had been uncovered by the work of an archaeologist. This approach conceals the full story behind the origins and journey of the displayed artefact, removes the importance of the role of the archaeologist in the retrieval of artefacts and information, and further widens the gulf between the archaeological practice and the public.

Museums have slowly begun to improve communication between archaeological work and the public, lifting the veil from a profession and process from which the public may previously have felt excluded. Swain7 comments on the common public misconception that ‘much current archaeology is undertaken by a small closed profession, by itself, for itself’, and the need for social inclusion in order to communicate the importance of cultural heritage and foster a sense of public interest, ownership and value within it. Over the past two decades, the temporary archaeological exhibitions curated by the National Roads Authority have brought recognition of the associated work of archaeologists to the fore of the Irish museum sector. While the artefact displays of the NRA exhibitions remained in a traditional style, the detailed presentation of the stages of the archaeological process, combined with expanded archaeological site and artefact interpretation, provided a complete and detailed contextual presentation style for comprehension of the displayed objects.

Fig 3. Reconstruction of an archaeological excavation in Louth County Museum. Author’s image

7. Davidson, B., Heald, C.L. and Hein, G.E. (1999) Increased exhibit accessibility through multisensory interaction. In Hooper-Greenhill, E. (1999) (ed.) The Educational Role of the Museum (Second Edition), Routledge Press, London and New York.

With consideration of our current economic climate, it is an important responsibility of the museum as a heritage institution to demonstrate to the public the validity of the role of the archaeologist, whose work and research serve to constantly provide us with new information and artefacts which reveal further detail about our rich past. The support and interest of the public in archaeological work helps to ensure the continuation of the profession. An effective and well developed archaeological exhibition should include and recognise the value of archaeological practice, and thus provide the full story and background in the life of its displayed artefacts.

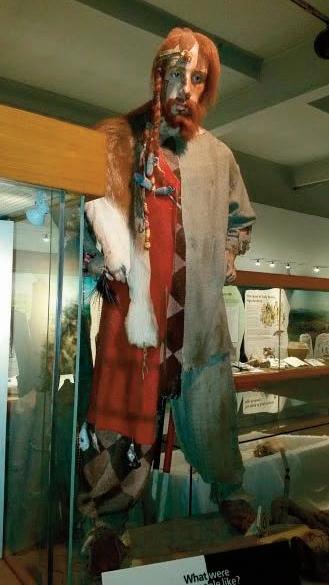

The use of models, replicas and reconstructions

Replicas are frequently used in Irish archaeological exhibitions in order to provide representations of artefacts which are in permanent display in the National Museum of Ireland. However, research has shown a significant degree of curatorial reluctance to engage in the use of threedimensional and pictorial reconstructions, possibly due to a fear of peer criticism and the reluctance to delve further into interpretation beyond didactic classification and identification. A small number of the institutions researched explored the aspects of interpretation through scale physical reconstructions or visualisations. unfortunately the majority of these examples do not discuss any other potential possibilities or alternatives to the theorised representations presented, which, in the absence of challenge, appears to provide a defined archaeological fact. The inclusion of additional text discussing a number of other options, or a number of illustrations displaying the latter, would contribute significantly to the potential learning and advanced levels of interpretation which could be conveyed by these depictions.

While often subject to limitations and professional criticism, reconstructions and dioramas serve to create a visual context for comprehension of object interpretations. Objects simply displayed in isolation on a modern background often remove an understanding of the original role and function of the artefact. While authenticity and accuracy are a contentious issue with the use of models and reconstructions, and is one which should be acknowledged in the exhibition, their use as a supportive role in exhibitions often serves to heighten visitor interest, stimulate thought and engage them in debate and discussion.

While the quality and authenticity of human models or dioramas in archaeological exhibitions can be debated, it can also be argued that

Fig 4. Use of a divided image of a Neolithic man to represent the difficulties in prehistoric interpretation from the Alexander Keiller Museum, Avebury, England. Image courtesy of English Heritage. their inclusion serves to keep human representation at the forefront of the interpretation, and provides a human connection and more understandable context for the public. The diorama can also be argued to represent a creative development in archaeological exhibition, aiming to provide a representation of a directly relatable context for the artefacts displayed, as well as presenting a clear human presence and significance within the exhibition, an issue which has often been lacking within previous object-centred prehistoric exhibitions.

Comparison with UK and European archaeological exhibitions

Throughout the united kingdom and Europe, several museums have experimented with a range of learning methods and display formats when exhibiting archaeological material in an attempt to heighten public understanding and better present the complexities of the archaeological past. These examples include exhibition approaches such as polyvocalism8, dioramas and illustrations representing opposing theoretical possibilities for our prehistoric ancestors9 and the use of empty exhibition cases to symbolise the lack of material evidence which tells us about the role and actions of prehistoric women10 .

Certain exhibitions have also experimented with replacing the use of a chronological layout with a thematic style, actively humanising the past of an artefact11 and overall immersive multi-sensory exhibition experiences. Exhibitions have also presented open admittance of curatorial uncertainty and theoretical discussion regarding prehistory12 . The innovations, experimentation and progression seen within these examples serve as comparative studies and inspiration for advancements within the archaeological exhibition sector in Ireland.

8. Swain, H. (2007) An Introduction to Museum Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 284. 9. Bender, B. (1995) Multivocalism in practice: Alternative views of Stonehenge. In Denford, G.T. (ed.) Representing Archaeology in Museums, The Museum Archaeologist Volume 22, pp. 55-58.

With consideration of current budgetary and staffing restrictions imposed upon the museums in the Republic of Ireland, there are a

10. Stone, P. G. (1994) The redisplay of the Alexander Keiller Museum, Avebury, and the National Curriculum in England. In Stone, P. G. and Molyneaux, B. L. (eds.) (1994) The Presented Past: Heritage, Museums and Education Routledge Press, London, 190205. 11. Swain, H. (2007) An Introduction to Museum Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 215 12. Van der Donckt, M. and Callebaut, D. (2001) Case Study 7.2: The Feast of a Thousand Years at the Ename Provincial Museum, Belgium. In Lord, B. and Dexter Lord, G. (2001) The Manual of Museum Exhibitions, Altamira Press, 247-258. number of ways in which static exhibitions could be revitalised through the use of low-cost additions.

Sensory experiences

Research has shown that the use of the sensory experience of touch is particularly underused as an archaeological exhibition element. Ideally, each museum should have a handling collection which should be accessible to all of the visiting public, rather than just selected school and education groups. These collections, comprising of robust, conservationally stable artefacts from the museum archive, could potentially be firmly affixed to a parallel display panel and within scope of a security camera, allowing tactile, hands-on visitor interaction in an exhibition setting. As an alternative means of display, the collection could potentially be placed for handling on a volunteer-manned desk within the gallery. Evaluation has shown that as well as providing an enjoyable and unique experience, handling authentic artefacts creates memorable and potent experiences, which are unequalled and which greatly enhance the learning experience. The sensory experience of sound within static archaeological exhibitions could potentially be utilised by the addition of a noise or music soundtrack to a gallery. Olfactory experiences through smell are frequently excluded from exhibitions, and often create issues in their use separate to a contextual diorama, but these could be used sparingly by museums with a number of galleries which separate their collections by chronological periods or themes. Sensory additions serve to enhance disabled access, as well as visitor entertainment, learning and memory retention.

Text and labels

The addition of flip labels to a static text panel provides an inexpensive and popular medium with which to layer information and provide heightened interaction with the visitor. In the case of text-heavy panels, the layering of information through flip labels encourages engagement with a wide range of audiences, particularly children. The simple yet effective inclusion of a clear, unambiguous image illustrating the original appearance or use of the displayed archaeological object can also result in the significant enhancement of visitor comprehension and appreciation. This provision of visual context and examples of use produces a form of reconstruction which presents an immediacy of communication for the visitor.

Archaeological interpretation

The presentation of archaeological artefacts in unusual, non-traditional styles has previously been successfully explored by a number of museums, most notably through the juxtaposition of contemporary and ancient objects in order to present a modern equivalent of the artefacts and archaeological sites. These techniques could potentially be used to enhance public comprehension of the role and use of the objects through the use of familiar symbols and themes. Research has shown a notable lack of engagement with the possibilities of archaeological theory in exhibitions in the Republic of Ireland. Active engagement with a range of archaeological theories in exhibition would present the museum with the opportunity to involve the museum visitor in ongoing discussion, sparking their imagination and provoking further thought and contemplation. In cases where budget limitations hinder the revitalisation of new interpretative panels, the addition of a number of laminated factsheets or flip labels would provide an inexpensive and easily altered format which would add an additional layer of information to the display.

Presentation of the archaeological process

The presentation of the archaeological profession and its work is a necessary and important development in archaeological exhibitions. The discussion of this subject matter should hold a place within the permanent exhibition gallery, providing an explanatory context for the displayed artefacts, and imparting a representation of a living, continuous profession, whose ongoing work provides the constant potential for further discoveries and information. An honest presentation of the dynamic archaeological process, which often deals with the interpretation of limited and uncertain material remains and conflicting academic theory, would help to demystify archaeology for the public.

Conclusion

Overall, the author’s research has uncovered a need for regeneration and development of the ways in which archaeological collections are exhibited in the Republic of Ireland. It can be argued that only approximately half of the fifteen research museums exhibited an overall adherence and commitment to the subjects of innovation and development, with only three offering a consistent and combined range of examples. Research revealed a common continuation of the

traditional style of archaeological exhibition within a large percentage of the museums. This consisted of simple chronological displays of artefacts labelled according to specialist classification, and a reliance on text-heavy labels or an overuse of technical terms and academic language. A number of museums lacked the inclusion of multi-sensory experience, and the majority excluded the use of active engagement with archaeological theory and discussion within their interpretations. Discussion of the work of the archaeologist was overlooked in several of the permanent archaeological exhibitions of the institutions, with discussion of this subject mainly dealt with through the means of former temporary exhibitions.

Museum exhibitions are undoubtedly one of the best mediums through which to communicate the research, findings and discoveries of archaeology to an eager and interested public. Archaeology is a fascinating, absorbing subject and a living, stimulating profession, which requires considered and appropriate interpretation, communication and display in order to fully capture its value and potential for the public. The museum exhibition provides an excellent forum for the presentation and discussion of these aspects, and an opportunity to inform the visitor of the importance of the preservation and research of their cultural heritage for future generations. It is imperative that museums embrace the importance of continual innovation and development within their exhibitions, and work to exhibit their archaeological collections to the highest and most effective standard possible. It is hoped that the outcome of this study may contribute to a better understanding of the current interpretative capabilities, standards and needs of Irish archaeological exhibitions, as well as prompt debate and consideration of possible future requirements and changes within the wider museum archaeology sector.

Donna Gilligan is a Documentation Assistant at the National Museum of Ireland.