17 minute read

l Terror and hunger, disease and death: Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum

from Museum Ireland, Vol 24. Lynskey, M. (Ed.). Irish Museums Association, Dublin (2014).

by irishmuseums

Terror and hunger, disease and death: Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum

NIAMH O’SULLIVAN

Advertisement

1. This article is based on a talk presented at the Irish Museums Association Annual Conference, Museums &Memory: Challenging Histories on 22nd February 2014, Waterford 2. Southern Reporter 1 May 1847 3. O’Sullivan, N. (2012) ‘Lines of Sorrow: Representing Ireland’s Great Hunger.’ Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum Inaugural Catalogue, Quinnipiac University, Hamden, CT

Introduction1

“We are overwhelmed with distress; we are crushed with taxation; we are scourged by famine; and visited by pestilence. Our jails are full; our poor houses choked; our public edifices turned into lazar houses; our cities mendicities; our streets morgues; our churchyards fields of carnage.... Society itself is breaking up; selfishness seizes upon all; class repudiates class; the very ties of closest kindred are snapt asunder. Sire and son, landlord and occupier, town and country repudiate each other…. Terror and hunger, disease and death afflict us… (Southern Reporter, 1 May 1847)”2

Almost ten times the population of Ireland today that is over 40 million Americans declare Irish ancestry, large numbers of whom descend from the Great Hunger. However, it took almost a century-and-a-half for historians to focus on the political, social and economic causes, and consider its consequences in Ireland, and around the world. Certainly, the loss of life, the leeching of the land, the guilt of survivors, and the erosions of language and culture remained unaddressed in the visual arts until the 1990s. Around the 150th anniversary, Quinnipiac university in Connecticut determined to commemorate the tragedy through the formation of an art museum. This article considers the rationale for the foundation of the museum, and explores aspects of its inaugural collection.3

Visual interpretation of the Great Famine

The story of the Famine had been told in words but, prior to the establishment of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, no institution had interpreted visually the greatest demographic catastrophe of nineteenth-century Europe – remembering that those who experienced the devastation, and suffered its terrible fallout, did so, at least initially, with their eyes. They saw their food rot in the soil; they saw the food grown for others exported, while they starved; they saw their homes

4. O’Sullivan, N. (2014). The Tombs of a Departed Race: Illustrations of Ireland’s Great Hunger, Quinnipiac University, Hamden, CT 5. Smyth, W J. (2012) “Mapping the People: The Growth and Distribution of the Population”, Famine Atlas, Cork, Cork University Press, 3-22. razed to the ground; they saw their mothers and fathers and children die terrible deaths; they saw their country recede as, dispossessed and desolate, they fled – sights that were etched in memory, but seldom found visual expression.

In making conditional the calibre of the work and the standing of the artist (in addition to the subject matter), the challenge was to give exemplary visual form to the Famine and its memory. And this remains an ongoing challenge. While much is made of the muting of the Irish language, and the consequent difficulty in speaking about the Great Hunger, even more notable is the paucity of images contemporaneous with it, and of it, after. If the Famine haunts fine art by its absence, it did, nonetheless, find its voice through other media, hence the collection and exhibition of images in non fine art media in the museum.4

In 1790, the population of Ireland was approximately four million. Fifty years later, it had exploded to over eight million. Between 1841 and 1891, it dropped to 4.7 million. A million died, during, and in the immediate aftermath of the Great Hunger, 1.25 million emigrated, followed by up to 2 million further emigrations to the end of the nineteenth century.5 Over a fifty-year period, almost half of the population of an entire country disappeared. Famine remains, almost until the end, reversible – its continuation over a seven-year period can only be seen as political.

Written accounts of the Great Famine

Given the scale of the horror, much is made of the inexpressibility of the Famine, yet much is written. In 1847, the social activist and humanitarian from Connecticut, Elihu Burritt, spent four months in Skibbereen. ‘I can find no language nor illustration sufficiently impressive to portray the spectacle to an American reader’, he said. But he did find the words, and his accounts of the starvation, disease and death are harrowing. He described soup houses engulfed by “famine spectres, half naked, and standing or sitting in the mud … young and old of both sexes struggling forward with their rusty tin and iron vessels for soup, some of them upon all fours, like famished beasts.” When Burritt came across “breathing skeletons”, he declared that had their bones “been divested of the skin that held them together, and been covered with a veil of thin muslin, they would not have been more visible … an appearance … seldom paralleled this side of the grave.”

Elsewhere, he found a small shed:

“The aperture of this horrible den of death would scarcely admit ... the entrance of a common-sized person. And into this noisome sepulcher living men, women and children went down to die; to pillow upon the rotten straw, the grave clothes vacated by preceding victims and festering with their fever. Here they lay as closely to each other as if crowded side by side on the bottom of one grave.”6

Fig 1. Irish Peasant Children. 1847. by Daniel MacDonald © Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipiac University One account was more terrible than the other” “little boys and girls presented a hideous sight…. their heads had become bald and their faces wrinkled like old men and women of seventy or eighty-years-ofage.”7 A local Skibbereen doctor, Daniel Donovan, described how “the face and limbs become frightfully emaciated; the eyes acquired a most peculiar stare; the skin exhaled a peculiar and offensive fetor, and was covered with a brownish filthy-looking coating, almost as indelible as varnish.”8 And in his study of “homicidal starvation”, Alfred Swaine Taylor concluded: “life is commonly terminated by a fit of maniacal delirium.”9

Such descriptions contributed to the view that the Famine could not be represented.10 And indeed there are few paintings to match the shocking words. Simply, the visual language to paint the lived nightmare did not exist – the few attempts to do so, such as Daniel MacDonald’s’ Discovery of the Potato Blight’ (c.1847, Folklore Department, university College Dublin), tilted into melodrama.

6. Burritt, E. (1847) Four Months in Skibbereen, A Journal of a Visit of Three Days to Skibbereen, and its Neighbourhood. Charles Gilpin, London. Reprinted in Southern Star, 4 and 11 October 1869. 7. Armstrong, T. (1906) My Life in Connaught, Elliot Stock, London, 13. 8. Dublin Medical Press, 2 February 1848. 9. Taylor, A.S. (1853) Medical Jurisprudence, Blanchard & Lea, Philadelphia, 549 10. Gibbons, L. (2014) Limits of the Visible: Representing the Great Hunger, Quinnipiac University, Hamden, CT

Art and the Great Famine

Historically, violence or distress in art was softened for the sensibilities of the rich – distanced in time, or cloaked in mythology or allegory. Artists were trained to paint in a classical manner, their skills honed in the antique class, before studying the life model, by which time they were tuned to see the human body in an idealized way.

While the devastation defied the skills of the artists, the artistic careers of Irish artists, especially, would not have survived the attempt. The few British artists who addressed the Famine muted or masked the horror. George Frederic Watts’ ‘The Irish Famine’ (c.1849, Watts

Gallery), shows healthy-looking peasants, distressed but far from starving, Francis Topham’s renditions were sentimentalized, and Alfred Downing Fripp’s sweetened. Erskine Nicol’s attempts at stereotypical humor, evident in the museum’s ‘A knotty Point’ (1853), ooze condescension, demonstrating the insidious power of art in the service of propaganda.

The standard presentation in pictorial newspapers of warmly clad, but lazy and stupid peasants, speaks volumes of British Famine denial, while the cartoons in Punch demonstrate just how entrenched were attitudes towards Ireland. Still, the question as to why so many Irish artists recoiled is worth asking? Most did not live in Ireland, but in London, where many were quick to suppress their Irishness. Exceptionally, Daniel MacDonald returned to paint the horror, hence the importance of his ‘Irish Famine Children’ (1847) in the collection. In London, the art market was centered on the annual exhibitions, where wealthy patrons would not countenance unacceptable subject matter – pictures of rotting potatoes, emaciated bodies or diseased corpses.

Art was intended to be pleasurable and morally edifying, sentiments and virtues irrelevant, it was believed, to the working classes or the poor. When it came to representing real-life events, painters struggled with fundamental concepts of contemporaneity and veracity. Even the emerging style of Realism, depicting the hard lot of peasants or urban workers, à la Millet or Daumier, could not transform the worst cataclysm of the nineteenth century – an epic of starvation, disease and death – into ‘art’.

It was only in 1847, coincidentally during the Famine period, that édouard Manet called on painters to be of their own time and paint what they see. Traditionally, artists filtered commentary on contemporary events through distancing mechanisms that were historicising or metaphorical. Most artists, therefore, addressed the Famine tangentially, allegorically or symbolically, culturally encoding their images to indirectly reflect events, behaviours and ideologies, rather than addressing them head on. Even if the will existed to paint such subject matter, there were deeply-rooted cultural obstacles to overcome.

So, if hunger was difficult to represent, how did people around the world learn of what was happening in Ireland during the Famine years?

11. Mitchell, WJT. (1986) Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology University of Chicago Press, Chicago, and Barthes, R (1961) ‘The Photographic Message’ and ‘The Rhetoric of the Image’ (1964), in Image, Music, Text, Hammersmith, London, 1977, 15–31; 32–51. No known photographs exist (although Sean Sexton’s collection picks up on the aftermath) but the Famine coincided with the birth of massproduced, illustrated newspapers, and by this means the world learnt of conditions in Ireland. Strikingly, some of the iconic Illustrated London News images, such as ‘Bridget O’Donnel and Children’ (22 December 1849) continue to act as the starting point for many contemporary works in the museum, such as john Behan’s ‘Famine Mother and Children’ and Rowan Gillespie’s ‘Statistic I’ (2010).

The new illustrated weeklies featured a symbiotic relationship between image and text that shifted in relation to different issues and from one illustrator to another. From sympathetic descriptions of poverty, the pendulum swung to the condemnation of a peasantry seen as in the grip of savagery and primitivism. In this respect, the power of the images was either confirmatory or corrective, often depending on the nationality of the illustrator. This has important implications for how we look at images, for it suggests that even the most realistic images can be read in accordance with the interests of its different consumers.11

In the late nineteenth century, artists confronted further challenges. With the lapse of time – creating perhaps the distance from the Famine to look at it anew – the vocabulary of art was shaken by Impressionism, a style that neither politically nor artistically could absorb historical subject matter. In Ireland, the response of the more advanced artists was to combine the dual impulses to work in the new idiom of landscape painting, influenced by avant-garde techniques in art, but stiffened with an underlying political message, that included making ordinary people the subject of important art. In certain hands, landscape painting became a politicized genre, with the unspoilt landscape of the West of Ireland becoming identified with the precolonial, unsullied Gaelic world that embodied the promise of a resurgent nation, and here Irish identity was seen to reside. This view of an authentic culture was promulgated by artists in an evolutionary line, from George Petrie to Frederick William Burton to Aloysius O’kelly.

Of course the seven deadly years of the Famine did not grow out of nothing, and nor did its consequences end when it did, for that reason it is the long story that is told in the museum. In james Brenan’s ‘The Finishing Touch’ (1876) and Howard Helmick’s ‘Mending the Nets’ (1886), the focus on the everyday aspects of the lives of those who survived, the ongoing sadness associated with emigration, and the burden of remembering is palpable.

In America this legacy took on a life of its own. Margaret Allen’s ‘Bad News in Troubled Times’ (1886) addresses the dynamiting campaign in the 1880s, fuelled by memories of landlordism and British misgovernment, amid fresh fears of famine in the late 1870s. A new wave of immigration in the uS consolidated a determination to retribution. Consequently, in january 1885, London was subjected to a barrage of ‘outrages’, executed by Irish-American Clan-na-Gael.

When Independence was won in the twentieth century, the struggle to build the nation rather than dwell on the past took precedence. As generations succeeded each other, the memories of the Famine burrowed deeper, and while occasionally surfacing in works, such as Lilian Davidson’s harrowing child burial, ‘Gorta’ (1946), landscape paintings by other artists, such as Paul Henry, sought to establish repose rather than stir up the past. In 1945, the anniversary was scantly acknowledged – the one exhibition was not held until 1946, and then conceived as in memoriam of Thomas Davis, suggesting a lingering shame. The onus to confront the Great Hunger, to mark it, and make sense of it, if such is ever possible, passed thus from one generation to the next. The view that the Famine could not be expiated until Ireland mourned its dead and came to terms with the presence of the past in our lives today is a relatively recent concept, as is the idea that art has a role in that endeavour. From relative silence, an unprecedented eruption of memorials around Ireland and the uS followed. This movement generated many maquettes, by john Behan, Glenna Goodacre, éamonn O’Doherty, Margaret Chamberlain and others, now in the museum, providing transnational maps of memory on both sides of the Atlantic.12

In addition to the profusion of bronze memorialization, two other dominant strands in art can be identified, each represented in the museum. An attempt to face history, and mourn the suffering and loss endured during the Famine years, through pushing the limits of visual

Fig 2. Gorta. 1946. by Lilian Lucy Davidson © Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipiac University

12. Mark-Fitzgerald, E. (2013) Commemorating the Irish Famine: Memory and the Monument, Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, and Marshall, C (2014) Monuments, Memorials and Visualizations of the Great Famine in Ireland, Quinnipiac University, Hamden, CT

form. Alanna O’kelly’s ‘A kind of Quietism’ (1990) draws on contemporary accounts of the Famine, and combines photography and text to produce landscapes that are both ‘garden’ and ‘grave’. Deep compassion is also evident in kieran Tuohy’s ‘Thank you to the Choctaw’ (2005). Famine commemorations are redolent in both giving and receiving. The beleaguered Choctaw took on the sufferings of the Irish, sending money for the relief of the Famine. Only 16 years before, more than half their own tribe died on the Trail of Tears, from exposure, hunger and disease. Tuohy interweaves a totem-pole style of storytelling with a Celtic way with narrative. In his apocalyptic ‘Departure’, Pádraic Reany depicts a human procession crossing a bloodied potato field, the uncoffined dead lying in shallow graves beneath the feet of the living, the living on the long march towards a famine ship, and exile. And john Coll’s hollowed figures, carrying the dead within, are also powerful metaphors of death by starvation.

If facing the sorrow, anger and suppression is necessary – so that we can begin to acknowledge, understand and let go – it may be that ‘indirection’ allows the image to go below the surface to what lies below, revealing deeper truths through disfiguration’. Hughie O’Donoghue explores the significance of memory in his evocative work, and reminds us that while the past may be over, the work of memory remains to trace its long shadow on the present. A third strand addresses causes, consequences and apportionment, resulting in some strikingly polemical works. The unsuppressed rage deep in Brian Maguire’s ‘The World is Full of Murder’ is shown in the splayed, foreshortened and fragmented body parts. Death from hunger, in a world with excess food supplies is nothing short of murder, argues Maguire. This painting emanates violence, the pigment is visceral, the gesturing aggressive. The artist insists on the power of art to express political, social and humanitarian views.

Works of ‘record’, intent on doing justice to the truth, include Rowan Gillespie’s ‘Statistic I’ and ‘Statistic II’ (2010) that commemorates the discovery under a parking lot on Staten Island of some 650 human bodies, the remains of immigrants who, having fled the famine, survived the horrors of the ‘coffin ships’ and arrived in the New World. Here they died in quarantine from the diseases they carried with them. Amazingly it has been possible to identify the name, age, date, and cause of death of most of those who were so unceremoniously disposed of in this mass grave. But the gut wrenching painting that assaults

Fig 4. Statistic I & Statistic II. 2010. by Rowan Gillespie © Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipac University audiences most forcibly – visually and psychologically – is Davidson’s ‘Gorta’ (1946). All narrative is eliminated, they have come from nothing, lost everything, and now traumatised, they look past one another into nothingness.

Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum

A number of things make this museum notable. It is founded on interdisciplinary principles, informed not just by art history, but by contemporary history, cultural theory, philosophy, political economy, literature and music, and complimented by a rich cultural and educational programme, underpinned by scholarly publications, breaking new ground in Famine research.

In the build up, unusually, as new work was acquired, the space was adapted to the art, rather than the art to the space, creating internal vistas that lend themselves to telling the story in unexpected ways. The ground floor gallery is low, sombre and cavern-like – a setting for a seanchaí. The strong narrative vein continues in the upper gallery where Robert Ballagh’s stained glass hangs high in a glass atrium, performing much the same didactic function as stained glass in a medieval

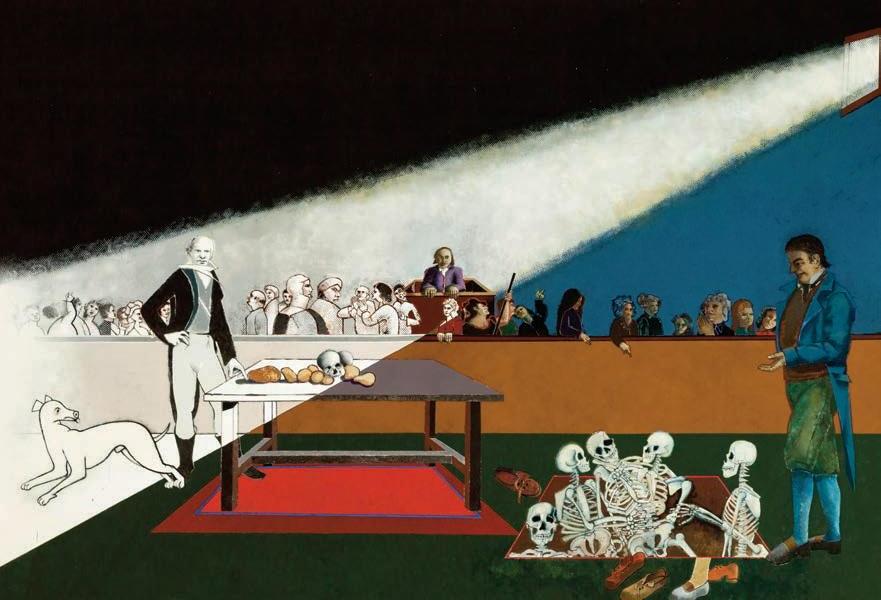

Fig 3. Black ‘47. 2013. by Michael Farrell © Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, Quinnipiac University Cathedral, as if to comment on the biblical proportions of the Famine. Here too the massive 14 ft Michael Farrell ‘Black ‘47’ is placed at an angle to a window, creating what appears to be a seamless continuum from the natural light outside to the raking light in the painting that illuminates Charles Trevelyan –standing in the dock before a jury of the dead, testified against by bodies who spout up from the grave – finally arraigned for his management of the Famine on behalf of the British establishment.

The collection works top down and bottom up resulting in an interaction of art and wider visual culture. But as a largely invisible trauma, finding appropriate expressions of both the gaps and interconnections in Irish and Diasporic history was, and is, a challenge, to the extent that some images are more tellingly expressed by their absence, as it were. Through the development of interactive programmes, important themes of poverty, dispossession, displacement, alienation, violence, loss of language, as well as issues of class, gender and identity will be explored.

Conclusion

As an all-shaping event, it is worth asking why so little attention has been given to the Famine in Irish cultural institutions? Before independence, many were fearful of drawing attention to themselves by antagonizing the colonizer, or of giving offence to an Anglo-Irish ascendancy that dominated cultural as well as political and economic life. Even in post-colonial times, there appears to be some nervousness about exploring intellectual ideas related to a politics of representation. Indeed a lingering nostalgia for the Great House with its carefully sanitized art and artefacts, rather than the more troubling habitus of the dispossessed and disenfranchised, whether in the country or the city, remains a consideration.

How can we, in the twenty-first century, find ways to remember a terrible past that shapes our world as it is today? As we grow more distant in time, we can face it better, but perhaps understand it less. The impossibility of giving voice to those who experienced the Famine, the paucity of material traces, the scarcity of contemporary visual images, and the subsequent oral and written histories, create both challenges and interpretative opportunities that few institutions address. Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum seeks to provide a space where, to borrow Seamus Heaney’s words, “hope and history rhyme”.13 Indeed the difficult subject prompts myriad responses – sadness, guilt, anger and discomfort – from often emotional visitors, who feel they are confronting their history for the first time.

Professor Emeritus Niamh O’Sullivan is consultant curator to Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum

13. Heaney, S. (1991) The Cure at Troy: A Version of Sophocles’ Philoctetes Faber, London