14 minute read

l Where contemporary art and histories can meet

from Museum Ireland, Vol 24. Lynskey, M. (Ed.). Irish Museums Association, Dublin (2014).

by irishmuseums

Where contemporary art and histories can meet

HELEN CAREY

Advertisement

1. This article is based on a talk presented at the Irish Museums Association Annual Conference, Museums & Memory: Challenging Histories on 22nd February 2014, Waterford 2. Gillis, J. (1994) Commemorations: Memory and Identity: The History of a Relationship, Princeton 3. Letter, Gustave Flaubert to Ernest Feydeau, 1859, Few will suspect how sad one had to be to undertake the resuscitation of Carthage. In Benjamin, W. Selected Writings Volume 4 19381940 Eiland, H and Jennings, M.W. (eds) Harvard University Press, Harvard 4. Binyon, L. (2014) Ode to Remembrance. The Times September 2014.

Introduction1

In commemorations and historical enquiry, the politics of national identity are centre stage. In de-coding what the Act of Remembrance is really about, what the relationship between Memory and Truth is, and that between Truth and Identity, as well as the power relations matrix lying behind the choices made of what to commemorate, are dizzyingly complex. However, the need that society has to remember from the early 20th century seems to be in direct proportion with the complexity of current identity. As john Gillis points out ‘memory work is like any other kind of physical or mental labour, embedded in complex class, gender and power relations that determine what is remembered (or forgotten) by whom and for what end’2. That we need to remember in order to know who we are is a trope that has been accepted recently.

During a 20th century marked for its wars, Walter Benjamin cited Flaubert when in Theses on the Philosophy of History (1930s) he says: ‘Peu de gens devineront combien il a fallu être triste pour ressusciter Carthage’3 drawing the energy from grief and melancholy, which are often subverted for the ends of the power but historically strong and essential facets of being human. It was in the dawn of World War 1 that the imperative ‘at the going down of the sun/ and in the morning/we will remember them4 which marked the sacrifice of the dead, it was also a rallying cry for more men to join up, in order that the sacrifice of the dead be not wasted – and Britain could win the war. That in Europe, Britain and its allies won the WW1 – The Great War – and that we do remember them, spending much time rehabilitating memories as society demands, shows that truth is often with the triumphant; since then, there is an awareness of remembering, even though each year since the first Armistice, the century of War rampaged on, although it was too late, the fabric of society was changed forever in 1918. So why remember?

5. Gillis, J. (1994) Commemorations: Memory and Identity: The History of a Relationship, Princeton 6. Ireland in turmoil: the 1641 Deposition – Witness Testimonies of 1641 Irish Rebellion curated by Professor Jane Ohlmeyer, Trinity College Dublin, October 2009 Society has become increasingly complex – in the 21st century, these complexities include a technological, spiritual, national and cultural identity to name a few, all of which can be conflicting with each other. The act of remembrance can serve to consolidate and at least reduce the psychologically debilitating multiplying of identities, which leads to a chaotic society. Thus the management tools that enable relations within society to be, at the very least, contained, include the rituals and orchestrated acts of remembrance, where aspects of national identity are stabilised. So within all the ideas of how these remembrances are framed, it must be acknowledged that the final framework can represent the victory of a set of identities over another, that ‘while the results may appear consensual, they are in fact the product of processes of intense contest and in some cases annihilation’5

Another aspect of remembering is who does the remembering. In the past, the social structures were such that extended family living together and organised institutions meant remembering and the idea of a past, present and future ran side by side, that no special effort was required, that time was not so linear. Records were kept by the keepers of social order like organised religion or community groups. However, in the 21st century, the individual is often the arbiter of their own truth, sometimes even the creator. The ensuing constructed view of the past can often depend on unstable characteristics yet very real aspects, such as the emotional. How to measure and codify a dependable methodology for truth that comes from myriad individuals is a challenge for the public arena where remembrance happens. All is fluid, all is in flux even that which we see in contemporaneous time cannot be trusted as stable. Can we trust the Artist, are we at the point that the potential for Contemporary Art may be signalled. Perhaps this field can be a divining rod for a relevant approach to remembering for our age.

Contested remembrances

Stakes are high in contested territories. The Depositions of 1641, curated in public exhibition by Professor jane Ohlmeyer most recently6, outlined events so traumatic and devastating that the contemporary witness accounts seem too shocking to even accept. The rebellion of the Irish at that time of their Protestant planted overlords entailed massacre, unsurpassed in brutality and yet in the general public, this occurrence is not widely known or understood

7. Higgins, R. (2007) ‘Sites of Memory and Memorial’ In M.E. Daly and M O’Callaghan (eds.), 1916 in 1966: commemorating the Easter Rising Royal Irish Academy, Dublin 272-302 , Whelan, Y. (2003) Reinventing Modern Dublin, 2003, UCD Press, Dublin today. The accounts are witness accounts, preserved on cloth, and their very materiality distracts us from the content. This materiality becomes the object in itself, appearing to defy time and decay.

Equally the Famines of the mid-19th century are only recently admissible and the Famine Commemorations have the tendency to be low key and subtle, although rising in profile year on year. The existence of a recently commissioned memorial site for the Irish Famine in New york City, in an area where real estate is at premium price, serves to complicate the home response even further. Both of these events are not part of the accepted current identity and the remembrance or remembering is managed: couched in references to contemporaneous historic accounts in the case of the Depositions or in the Famine populist props and staging, the emotional aspects of these highly traumatic events are managed. It is almost as if the public cannot be trusted to re-enter these arenas and connect emotionally. In this, the memory is repressed.

For the 1966 Commemorations of the Easter Rising 1916, after 50 years of independent statehood, there were significant official attempts to introduce a sense of the contemporary culture, within already highly contested territory. As both historian Róisín Higgins and social geographer yvonne Whelan outline7, the commissioning of a sculpture by Oisín kelly for the Garden of Remembrance, which finally resulted in the Children of Lir, of the development of the Gardens themselves and their symbolism, as well as the context of the modernising Agenda of Seán Lemass, revealed the hotly contested territories that 1916, Art and the public arena involves. In terms of its site, the discordant character of the north inner city area surrounded on all sides by varying functions, and the overloading of the Garden plan with symbolism, as well as the length of time over which the project unfolded (1965-71, when Oisín kelly’s final sculpture) the project became an articulation of the difficulties of reconciling histories with futures.

The role of the state’s Office of Public Works who managed the official public realm, brought issues about identity and what the Rising represented, directly into discussions about the Future of Ireland. This was real energy behind the commemorative activities. So the involvement of commissioning permanent works involved pitting emotionally-held, contested truths against each other. In plain sight, what was represented in the public domain became an embodiment of a

8. Three Forum curated by Helen Carey, 2009-10, 1) The State we are in 2) Have we been here before? 3) What is to be done, funded by the Arts Council of Ireland and Dublin City Council, Mockingbird Arts, SIPTU 9. Major exhibition of Eileen Gray’s work took place in the Irish Museum of Modern Art in 2012, curated by Chloe Petiot and the Centre Georges Pompidou, provided this insight into an Artist living firmly and unapologetically in her time 10. Lockout & Labour (Limerick City Gallery August 2013), The Market by Mark Curran, Gallery of Photography, Dublin (August 2013), Belfast Exposed, Belfast (September 2013), Centre Culturel Irlandais Paris, (January 2014), A Letter to Lucy, Pallas Projects/Studios, Dublin (August 2013) – these exhibitions were curated by Helen Carey. Other partnerships with CCA Derry, Temple Bar Studios & Galleries, Dublin, Dublin City Gallery the Hugh Lane took place concurrently. power struggle, where the modernization of Ireland was confronted by a narrow historic nationalism. The truth or even the actual events of the 1916 Rising were not substantially a subject of their own remembrance platform.

So what can the content of a Commemoration or Remembrance be, if we are to bear in mind that the materiality of the historical artefact such as in the 1641 depositions allow us to bypass the content, or the trauma of the subject is incompatible with the received ‘image’ of the future identity such as the Famine, or if the content of any truth is so hotly contested, that the form cannot be agreed. If the imperative remains ‘We shall remember them’, is there a form that can help to articulate all and yet remain future-looking? Can Contemporary Art be this form?

Contemporary art and remembering: three artists and their art

The methodology arising out of 2009s Three Forums8, concerned reconciling the interest of the Citizen, the narrative in the Public Domain and the involvement of the Artist in the Act of Commemoration. What emerged was the possibility that perhaps the best platform for commemoration, is to live really in the present and ask Artists to consider this present time. The Artist Eileen Gray9 puts it well when she said ‘We must ask nothing of Artists but to be of their time’. This does not mean that they cannot consider the past, but most particularly with regard to remembering, the portal that the Artist opens for the public is the heightened present, and within this lies the potential for being emotionally present. At that point, the subject and notions around humanity and the challenges of living in the world are communicated – this is a function of that most contemporary visual art form, socially engaged Art. As part of the commemorative activities for marking the centenary of the Dublin Lockout 1913, a series of exhibitions took place10 that were a field work exercise of what Contemporary Art can represent within commemorative public events. Below are discussions of three of the artists’ work addressing materiality, contemporary context and the role of the artist, functioning in the field of socially engaged Art.

In Deirdre O’Mahony’s ‘T.u.R.F.’ (Transitional understandings of Rural Futures), the materiality of what the Artist presented brought the current struggle of the Turf Cutters’ dilemma in Ireland into context

Fig. 1. Deirdre O’Mahony. Transitional Understandings of Urban Futures (TURF) 2013. Installation shot, Limerick City Gallery of Art. Courtesy of the Artist and Limerick City Gallery of Art

Fig. 2. Mark Curran. Installation shot, The Market, Gallery of Photography, 2013 courtesy of the Artist and focus. Working with Turf Cutters from kildare, O’Mahony brought a stack of Turf into the Limerick City Gallery of Art, presented traditionally (fig. 1) Putting this stack centrally in the gallery, she surrounded the physical object with selections from the permanent collection which drew on historical notions of rural work, which can be seen in the background of the image. She presented the current debates and media coverage in print form that condemned the turf cutting alongside interviews with turf cutters. The source of the presented turf was subversive and while Art is a protected space, what O’Mahony did was render the gallery and the audience complicit and, with a moving speech by turf cutters present, the moment of synchronicity with those locked out in 1913 was entered. The materiality alongside the emotional allowed a full recognition of the value, place and stakes around Work to be felt, not just regarded.

With the backdrop to the marking of the Lockout centenary being the financial crisis in Ireland and globally, Mark Curran’s ‘The Market’ (fig. 2) took place in the site of the crisis – the international Stock Market. Looking at the stock markets of Frankfurt, Dublin, London and Addis Ababa in this ongoing project, Curran presented portraits of workers, soundscapes of the algorithms of trading and artefacts and transcripts from field research in four different places – Paris, Belfast, Limerick and Dublin. In this gesture, he showed, among other complexities, that the public arena or the place where the parameters of citizens’ lives are decided in the contemporary world, are both everywhere and abstracted. That the

same information arises in changing formats or guises depends on the culture of the place, with different conditions of display. However, Curran’s work elaborated that the underlying notion of moving towards a new era of late and determined capitalism, influenced by market forces that are beyond and out of control, served to connect the past and present into the future as a continuum; the swell and fall of the soundscape which charted the use of the term Market in official speeches by ministers from France, Britain and Ireland, put the viewer into the constantly mutating noise of the Market. While Curran’s ethnographic practice puts people at the centre of his work, with portraits and dialogue, the absence of the human hand in the soundscape hubris was palpable.

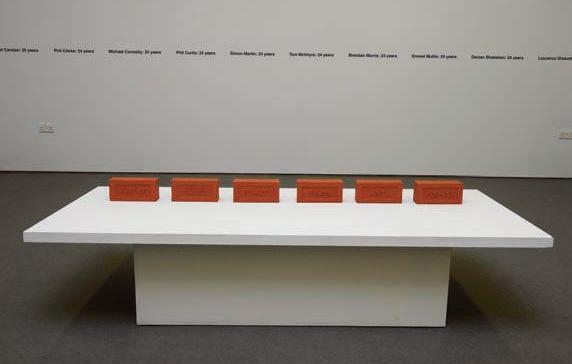

Anthony Haughey’s ‘Dispute’ (fig. 3) is a study of a strike and lockout of kingscourt’s Lagan Brick Factory, which marked the end of manufacture with loss of jobs in 2013. This dispute was as bitter as any of the past. What Haughey did was record images and to create objects, of the workers in discussion, in protest and in organisation. He was gifted some of the last of the bricks, transforming them into sculptural objects, incising their surfaces with words such as uNITy, justice, Equality, displaying them in the gallery alongside the names of the workers and their lengths of service In presenting the work, the artist positioned himself as the agent of the message to the public arena. He also occupied the role of the artist as witness or recorder in this dispute. This has resonance with the role played by William Orpen’s highly charged drawings of the soup kitchens of the time of the original Lockout which the artist sketched. Through time, the role of the Artist has varied. From the Artist being an activist, such as the artists of New york City in the 90s, such as Gregory Sholette’s ‘REPOhistory’11 or Graciela Carnevale’s activism and performance in Buenos Aires of the Grupo d Arte de Vanguardia de Rosario12 from 1965-69, the role Haughey plays in 2013 is that of witness, of committing the actuality to film, photography, video and object, and crucially, the installation can be re-created to present the dispute again: whether this allows the emotion or the understanding of the dispute to be felt again, the quality of the

Fig. 3. Anthony Haughey. DISPUTE. Installation shot, Limerick City Gallery of Art courtesy of the Artist and Limerick City Gallery of Art

11. Sholette, G. REPOhistory (1989-2000) www.gregorysholette.com 12. Graciela Carnevale, www.latingart.com

work and the context of its display as well as what the future holds will determine but importantly, the dispute is contemporaneously recorded at a time of its greatest intensity.

Time changing

Alongside the imagery and the material culture of a time, what these artworks attempt is an infusion of the emotional, alongside the visual or sculptural, and the sentient within the subjects, to enable the viewer to access what it felt like to be present. This methodology can be part of a challenging, high stakes curatorial strategy often accused of crossing fields into the psycho-analytic; an example of work that moves in these fields is that of the Denmark-based kuratorisk Aktion curators, which looks at the post-colonial condition, combines the artefact admitting the emotional as a means of addressing the past.13 Commissioning Artists to capture a moment like Orpen did in 1913, may be the best means of re-visiting a moment at a future date. In connecting to the Lockout of 1913 in terms of subject – work, dispute, context and future – what these artists among others, have done is allow the continuum to continue from the past through the present and into the future. In this presentation, there may be the best means to overcome the constrictions of time, to achieve what, T.S. Eliot suggests in Burnt Norton14

Time present and time past are both perhaps present in time future and time future contained in time past

Perhaps in doing this we manage to return to a time when there was no need to remember, when memory is safeguarded and living well in the present is the business at hand.

Helen Carey is currently Director of Fire Station Artists’ Studios in Dublin.

13. Kuratorisk Aktion www.kuratorisk-aktion.org 14. T.S. Eliot, Burnt Norton, Four Quartets, 1936