Table of Contents

1.Introduction

1.1. Note on terminologies

2.Space of In-betweenness

3.Methodology

3.1. Community-led Research

4.Unfolding the space of in-betweenness.

4.1. Co-creative Mapping

4.2. Co-creative Collage

5.Findings

5.1. Synthesis

5.2. Limitations

6.Conclusion

7.References

1

1.Introduction

“A theory of queers in space can first be constructed around the differences and disparities, in the extent of use and enjoyment, associated with gender, race, class, age, language and culture and secondarily around the dynamics of erotic expression, violence, and social control.” (Gordon Brent Ingram, Queers in space-1997)1

This thesis is based on intersectional and queer perspective, and it takes sexuality and migration as a critical area of scholarship in design field. Intersectionality is based on multiple intersecting identities that can have, focusing on issues within the structure of racism, homo- transphobia, ableism, class discrimination. Nina Lykke (2003) describes intersectionality as a feminist analysis of power imbalances based on gender and sexual identity, socio- economic class, occupation, age and nationality etc.2 People can be exposed to discrimination because of many different reasons. People who have multiple identities struggle in their life which is ridden with belonging, participation in Netherlands. For instance, Muslims who identify as LGBTQ+ are assumed to choose between being a ‘real Muslim’ or being a ‘real queer’ by Dutch society. They are not considered to be entirely European by the majority, but they cannot identify themselves with the generally accepted definition of migrant. This discourse of exclusion causes in-between state for this marginalized community. Mepschen, Duyvendak, Tonkens discuss about Dutch hegemonic discourses which is differentiate the migrants especially Muslims from the Dutch society. These discourses claim that this communities are incompatible with Dutch culture.3 El-Tayeb States that othering of

2

1 Gordon Brent Ingram, Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance, (Bay Press, Seattle 1997)

2 Nina Lykke, Intersektionalitet - ett användbart begrepp för genusforskningen, (Kvinnovetenskaplig tidskrift. Vol. 24 (1)), pp. 47-56

3 Paul Mepschen, Jan Willem Duyvendak, Evelien H.Tonkens, Sexual politics, orientalism and multicultural citizenship in the Netherlands ( Sociology, 44(5),2010),p.972

Muslims, including queers, is a European phenomenon. Europe, especially the Netherlands, is a place known for giving importance to values such as equality, democracy, tolerance and freedom of expression and speech.4 However, Islamophobia and the framing of immigration are seen as a main threat for these values by the majority. Cultural background of immigrants was considered as a threat due to its incompatibility with ‘emancipated liberal values’.

Even though there is tolerance of homosexuality in the Dutch policy, Jivraj & De Jong (2011) claim that homonormative model has forces because it still under the control of white, privileged, middleclass and capitalist individuals, that’s why enforcement of this model gets the rest of the LGBTQ+ individuals out of perspective. They argue that this model ignores the rest of the queer individuals and other races. Especially after the tragic event of 9/11, visibility of queer Muslims posed a threat and became risky in public spaces.5 Queer Muslims do not feel themself comfortable and safe with their multiple identities. They have options that they have to choose, and this produces a crisis. According to Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, having to make decisions which are related with habits causes a crisis.6 For instance, they can be strictly gay without the religious identity and they might be more accepted by Dutch society and integrated to the Dutch culture. On the grounds of this, they are stuck between their own ambitions and the imposed social norms.

On the other hand, Turkish Muslim community mostly in Netherlands based on patriarchal dominancy. Their approach to homosexuality is not positive and they prefer to ignore these identities.

3

4 Fatima, El-Tayeb,European Others: Queering Ethnicity in Postnational Europe,(University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis,2011)

5 Suhraiya Jivraj ,Anisa de Jong, The Dutch homo-emancipation policy and its silencing effects on queer Muslims,(Feminist Legal Studies, 19(2),2011), p.143.

6 Wendy Hui Kyong Chun , Updating to Remain the Same, Habitual New Media, (MIT Press,2016)

429 978 people of Turkish origin live in the Netherlands.7 The first male immigrants came here in the 1960s and 1970s as ‘guest workers’ and from the late 1970s their betrothed, women and children followed. Most migrants come from rural areas in central Turkey. Migration is a complex process. This displacement leads to new placement and place- making process. Because while it separates migrants from place, relationship, and context, at the same time connecting two previously separate places, home, and place of residence. It can be perceived as an opportunity to make people free from community structure in a new way of asserting their identity. The new environment may also challenge traditional community values and norms. Patriarchy dominance in this community can slowly break down, marginalized part of this community can adopt adaptive strategies to participate in a wider society. However, on that point, Aylin Akpinar pointed out that migration, on the other hand, can impose further restrictions on women as they are assigned the symbolic role of the bearer of ethnic group identities.8 Although this is a statement that specifically focuses on women, it can be said that men are culturally responsible for defining social norms related to others behavior, while ignoring their queer identities. Because in this context, traditional social norms such as honor and virtues are more influential than ever. Most of the Turkish immigrants in the Netherlands have rural origin. That’s why they have been directly imbedded into Dutch urban life without previous urban experience. This has a crucial impact on the concept and interpretation of urban life and urban space, creating a duality between the departure place and the arrival place.

Turkish-Dutch people are less integrated into Dutch society, more often see themselves as religious and have less modern views on male-female relations than Surinamese or Antillean Dutch; the differences between the first and later generations are also less. There is only a slight change in Turkish views in the direction of the

7 CBS. Bevolking; generatie, geslacht, leeftijd en herkomstgroepering [Population; Generation, Gender, Age and Ethnic background. Acceced 19 June,2022

8 Aylin,Akpinar ,The honour/shame complex revisited: Violence against women in the migration context, (Women’s Studies International Forum, vol. 26, n.5,2013) pp. 425 - 442.

4

Netherlands. The Turks in the Netherlands are strongly focused on Turkish life: they watch Turkish TV via satellite dishes, read Turkish newspapers and, unlike Moroccan Dutch, their icons are Turkish rather than Dutch-Turks. They form a fairly closed community that seeks or finds little connection with Dutch society9. They have their own organizations that function well. Social control is so strong that on the one hand anti-gay violence among Turkish-Dutch young men is less common, while on the other hand smooth access to the Dutch (gay) world is made more difficult for these young people. On December 7, 1987, js organized a study day on homosexuality for Turkish-Dutch citizens as part of her work for the Amsterdam jac, because many immigrant gay boys who had run away from home sought help there. Her colleagues wondered whether Turkish gays and lesbians really existed – homosexuality was so unknown among ethnic minorities. She received very contradictory reactions to her proposal: gays of Turkish descent who appreciated the initiative very much because they languished in loneliness and straight people who scolded gays and said that such a thing did not exist in Turkish culture and certainly did not belong there10. Briefly, their small-scale research shows that despite a great deal of effort from various sides – such as from governments – there is little progress around homosexuality among Turkish-Dutch citizens. Turks in the Netherlands form a closed community where negative judgments about gay sex and gender persist, where speaking about such topics remains a taboo and where coming out is still a risk. That's why it's not allowed to express themselves homosexually or heterosexually.

Turkish queer immigrants are stuck in a conflictual life that is considered an oxymoron. They are queer yet also Turkish and Muslim background, being of immigrant origin yet also Dutch. Having multiple identities and belongings makes them not feel belonging anywhere.

pp.289-292

10 Ibid,pp 302-303

5

9 Van Bergen, D. D., & Van Lisdonk, J. Acceptatie en negatieve ervaringen van homojongeren. (In S. Keuzenkamp (Ed.), Steeds gewoner, nooit gewoon: Acceptatie van homoseksualiteit,2010)

They inhabit an in-betweenness where they live between imperatives and various norms, expectations and desires scuffle. Their ambiguous position of queer Turkish immigrants leads my research paper to criticize the societal norms with focus on power, gender and sexual identities in public space. This research focus that how inbetweenness of Turkish immigrants' community with its complicated mix of heterogenous settings and practices of living together affect the heterosexuality of the space.

There are many different approaches and research about the concept of in- betweenness. Especially in design field, space of inbetweenness can be perceived in many ways by having a new identity, it faces with us with some roles which are gotten at the phase of human lifestyles, descriptions, interpretations and their taking shape. The Australian philosopher Elizabeth Grosz states in her book' 'Architecture From Outside' that in-between spaces are the space of the in-between that can form the basis for new relationships and many new formations to be established.11 Elizabeth Grosz defines the space of the in-between as:

“The space of the in-between is the locus for social, cultural, and natural transformations: it is not simply a convenient space for movements and realignments but in fact is the only place—the place around identities, be- tween identities where becoming, openness to futurity, outstrips the conservational impetus to retain cohesion and unity. “(Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture From Outside ,2001)12

I suggest that queerness, migration and culture represent a space of in- betweenness in which Turkish queer immigrants societally perceived paradoxical identities can be reconstructed. This research

11 Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture From Outside,(Massachusetts Institte of Technology,2001), pp 91

12 Ibid,pp 91

6

is about spatial characteristics of in- between spaces informed by three different kinds of narratives which are not easy to combine.

What are the spatial characteristics of in-between spaces that are shaped around Turkish queer immigrants’ experiences on queerness, immigration and culture in Netherlands?

This research paper used ‘queer’ specific sexual practices. It refers to the identity of people who practice nonQueer’ in this research can be read as a fluid and ambiguous term, which is distinguished by its resistance to fixed and given definitions, all kinds of identification processes. What is important here is that it would be wrong to read queerness as an identity politics specific to LGBTQ+. Queer emerges as a proposal of disidentification. It opposes any label related to gender, sexual orientation and sexual practices, and therefore any certain category on which identity and sexuality are built. While questioning the establishment and functioning of the norms that establish ‘normal’ and to the center, but to disrupt the center itself. Main questions of queerness center around the construction of sexual identity, how these identities are organized, and how identifications with these identities enable and/or constrain us. It is wrong to think of queer theory as consisting of texts dealing only with gender and sexuality issues. As a matter of fact, within this

13 Sara, Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects,Others,(Durham: Duke University Pres, 2006), pp161

7

approach, it is thought that individual (singular) experiences are shaped at the intersection of various identity categories but can only be understood through these multiple effects (as Butler meticulously reminds, being a "black woman" is not the same as being ‘white woman’)14. For this reason, class, race, ethnicity and disability were also included in these discussions, and sometimes queer (such as anarchism) was discussed together with other political lines.

In brief, what research understandings from term of “queer” is an opposition to heteronormativity. This non-normative space that stands out in the research paper doesn’t include only gay, lesbian or bisexual, but it also welcomes to multiple belongings and intersectional identities.

Migrant Background

In this research, the term of immigrant background is used in the framework of immigrants' sense of belonging in the host country and perception by the host country.

For the immigrant community, here is always a remarkable complexity of belonging by hear between the country of origin ( national identity), country of settlement (–the sense of loyalty) and many in between cultural attachments in their search for identity

Immigrant people in host country always carry their immigrant and they encounter it in every field. For example, Turkish immigrants with

14 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity,(New York: Routledge, 1999.)

15 Sylvie Fortin, Social ties and settlement processes: French and North African migrants in Montreal,(Canadian Ethnic Studies,34 (3),2002), pp76-97

8

Dutch citizenship can still consider themselves as immigrants. Christopher Caldwell, a regular contributor to the Financial Times, underlines that in his articles on Muslims in Europe, he will use the term 'European' for people of European blood and 'immigrant' for those

This term is more related with being Turkish and Muslim. While migrating, they also bring their own making with them; the habits, customs, and norms of use of spaces. In this way, social relationships and meanings related to previous experiences of spaces and places are brought into the new environment. In this new f the daily life of the house are maintained and preserved, however new practices are also constructed and new places are made, while some old customs and habits prevail, some others are abandoned or replaced that host country have less tolerance to accept this cultural integration. Being Muslim as Tayeb criticizes integration policies of Europe. Immigrants feel less belongness to host country as a result of social and political humiliation and economic marginalization. According to her, other is perceived as negative effect on European values. Immigrants who are Muslims face

16 Ilgin yorukoglu, Acts of Belonging: Perceptions of Citizenship Among Queer Turkish Women in Germany(2014)

9

to challenges in host county. Especially Queer Muslims are perceived as a threat for the European identity.17

2.Space of In-betweenness

The French philosopher Henri Bergson defines in-between spaces as spaces of development and transformation unlike fixed, constrained, determined and static relations18. And The Australian philosopher Elizabeth Grosz brought forward the term of "the space of the in-between," based on Henri Bergson's concept of in-between space, in her 2001 book 'Architecture From Outside'. Grosz says that there is an infection between one side of the border and the other side of the border where there is space in between. Due to this infection, the opposites, the boundaries that occur on the side and the other side, are interconnected. Grosz says that the in-between represents the existence of many potentials through infection and togetherness19

In-betweenness is a normless space where time and space are experienced differently from the traditional one. It is compressed by boundaries, but it also allows fluidity in between these boundaries. That’s why space of in-betweenness is not homogeneous but heterogeneous; It is the space of intersectionality, multiplicity, mobility, possibilities, formless, smooth and temporary. In-between space, which has the possibility of opening to otherness with tension and contradiction, is also a spatialization that increases diversity and embraces differences. The in-between space does not have an ideal form with a rigid frame like modern space, it is displayed with a discontinuous, fractal, curved geometry, and has no formal meaning. It is not measurable unlike modern space. While modern spaces do not allow coincidence, the in-between space is flexible and porous to

17 Fatima, El-Tayeb,European Others: Queering Ethnicity in Postnational Europe,(University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis,2011)

18 Henri Bergson, Matière et mémoire,(Les Presses universitaires de France, 1986) Henri Bergson, L'Évolution créatrice (Paris : Alcan, 1907)

19 Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture From Outside,(Massachusetts Institte of Technology,2001)

10

allow in and out. It is soft and fluid, and a space that is prone to transformation. The subject in modern space leaves one space and enters another. The relationship between subject and space is mechanical and disciplined like space itself. The time to be spent in space is also predictable. The subject experiences certain places at certain times. It has certain rules. As a result, the relations of the modern subject within the modern space are designed, predictable and rational.

In space of in-betweenness, the situation of the subject is uncertain compared to the modern subject and its relations are unpredictable. The experience of time here does not contain the rigidity of modern space, it is flexible and dispersed. Space in between is a formless but mental space which has difference, diversity and spontaneity inside. Exploring the space of in-betweenness which is the space of an idea of reality that has no identity has challenges. The unexpectedness and randomness in the space of in- betweenness make it a space of both escape and transition. Here, tension and contradiction diversify spatial experience. Tensions maintain its existence with contrasts, and these contrasts contribute to space to transform. In this space, which is neither that side nor the other side, which is between the dualities has non-grounded concepts. These concepts are flex and fluid. They intersect and every intersection creates production. Production continues here without interruption. On that point, the space of in- betweenness is full of potential. It is a space that diversifies, transforms, and redefines constantly. This intersectional space has a chaotic concept that establishes translational relationships with its surroundings. It transforms, corrupts, remakes its surroundings.

Space does not only define an order, but also contains inbetween unstable components. This is a state of instability that will evolve depending on the encounters that will take place in it. The order of space is a sign of its stability, completeness and distinctness. Order was planned to solidify and organize space. While the order expresses the end of the space, the in-betweenness defines the becoming. The emergence of space of in-betweenness prevents the space from being placed in order or being organized around an order. While it destroys boundaries, it also makes interaction between inside and outside alive and obligatory. That’s why it is not possible for any concept to cling to it. The continuity of transformation and conflict in space emerges as a

11

potential that enables thinking in other ways and allows differences to unfold.

The concepts of relationship and interaction, which are considered to be today's concepts, find a response to themselves in spatial solutions with in-betweenness. This concept is one of the issues that should be considered in the design in order to get away from some prejudices, norms and limitations. This fluidity can only be realized in in- between spaces that can provide the feeling of not being alienated in the space, the idea of belonging to that space, the provision of space-temporal continuity, relations and interactions. This thesis takes concept of in-between spaces in frame of experience of queerness, migrants and culture.

12

3.Methodology

The methodology of this research while considering inbetween space which is informed by three narratives was based on the definition of "in-between" which is developed by Elizabeth Grosz. According to Grosz, the in-between state is a descriptive thing that enables the formation of identities, allows existence, even though it lacks identity, form and quality. Grosz points out to potential of inbetweenness by emphasizing that the transition of the in-between notion to its own formation enables it to establish another relationship with different meanings. The in-between approach has also been used in architecture and has allowed the formation of new spatial relationships and approaches.

“Instead of conceiving of relations between fixed identities, between entities or things that are only externally bound, the in-between is the only space of movement, of development or becoming: the in-between defines the space of a certain virtuality, a potential that always threatens to disrupt the operations of the identities that constitute it.”

(Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture From Outside ,2001)20

This research paper develops “space of in-betweenness" in the context of Turkish queer immigrants' queerness, immigrants and cultural experiences in the Netherlands.

3.1. Community-led Research

This research is also seeking an answer that how it is possible to queering academic research, which is highly patriarchal, authoritarian, hierarchical, and has strict rules and what is queer

20 Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture From Outside,(Massachusetts Institte of Technology,2001) pp 9293

13

method and methodology in academic research. In line with queer theories, queer can be associated with actions such as disrupting identities, dualities and norms, becoming dynamic, constantly destroying, and crossing borders. Queer is a process rather than an ideal to be achieved. In this context, we can consider queer as an action rather than an adjective. That’s why "queering" may discussed as a part of our daily practices that we constantly repeat. There is a concern about queering academic research while focusing on researcher/subject and researched/topic as an identity and duality in this research paper. On that point, methodology was planned around the discussion about norms of academic production and its subversion and transgression and dynamism among the research, the researcher and the topic. These components are significant to deal with ethical part of this research.

Along with feminist criticism, the importance of subjectivity and experience in academic studies emerged. The claim that the researcher should be objective became critical. When considered together with queer theory, the destruction of researcher- researched and subject(l)-object(l) dualities and fixed identities can be significant part to think about. Is it the researcher who produces academic research? How can research exist without the knowledge of the researched? How does the relationship between the researcher and the researched affect the research? How do the identities, experiences and transformations of the researcher and the researched affect the research in the process? When these questions are considered from a queer perspective, it is seen that research is a very complex process. It is necessary to think of research as a relational, dynamic field where the components do not dominate over each other. In this direction, queerizing the components of the research and their relationality has been considered in this research paper.

While developing “space of in-betweenness", the design principles mentioned in Sasha Costanza-Chock’s book “Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need” will be applied into the process.

14

Sasha Costanza-Chock21 approaches the established dominant design paradigm from a justice lens in her book. She is questioning power in design processes while considering design justice. She brings out the relation of design, power and social justice by considering hegemonic universal design. The book presents us a way of designing which has concerns about the needs and experiences of people who are most marginalized within the matrix of domination. Designing or researching with people requires great responsibility, participatory-design discourse is not just about extracting feelings, ideas and experiences of marginalized community.

She shared Design Justice Network Principles22 that developed in workshop which was planned by Una Lee, Jenny Lee, and Melissa Moore in 2015. Main goal of Design Justice Network Principles is putting people who are normally marginalized by design to the center of design in design process. Working in collaboration is most important part of creative practices to address the deepest challenges that communities face. Design justice not only changes past injustices of the design or research process, but also erases barriers for the future while breaking the forms and dynamics of hierarchical research or design process. Design justice relationship between sociotechnical systems design and power and it's also about this growing community of designers, developers, artists, researchers, community organizers and many others who are interested in building the discourse and the theory and practice of design justice together. Design Justice inspired this research with critical analysis of the matrix of domination. The current DJN principles are listed on the main website:

“1. We use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

21 Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, (The MIT Press,2020), pp 5-9

22 Ibid, pp 6-7

15

2. We center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

3. We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

4. We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.

5. We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

6. We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to

7. We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

8. We work towards sustainable, led and controlled outcomes.

9. We work towards exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

10. Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what is already working at the munity level. We honor and uplift traditional, indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.”

16

Turkish queer immigrants in the Netherlands are a marginalized community that reconceptualize the system in which class, race and gender are interlocked mentioned in the book.23 These individuals are visible at their intersections. That's why this research fits in the frame of multi-axis analysis in which race, class, or gender is considered as an interlocking construct to support social justice and visibility of this community.

This research used participatory research method based on design justice in order to premediate ethics with the participation of queer Turkish immigrant individuals. In participatory research method, the roles of the researcher and user are blurred. Individuals participate directly in the design process and express themself. Co-creative research is a significant part of this method because the researched community is not a passive object and researcher doesn’t extract information and their experience for the research. In co-creative research, the roles are blurred, and mixed, researched community plays a role in whole process in research.

4.Unfolding the Space of In-betweenness

4.1. Co-creative Mapping

As the first part of my methodology, I met with the participants separately and discussed together the space of in-betweenness. In order to explore how in-betweenness is related to spaces, we prepared conceptual maps together based on their spatial experiences.

23 Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, (The MIT Press,2020), pp 17-18

17

18

Description of Participant A Map

Participant A is a 23-year-old queer Muslim man. He studies at university in Den Haag and lives with his family in Rotterdam. He was born and raised in Rotterdam which is one of the largest towns in Netherlands. His relatives also live in the same neighborhood. That's why he has been exposed to Turkish culture and traditions since he was child. The narrative of his family house is based on traditional Turkish gender roles. For instance, the living room mostly belongs to dad and kitchen is a space that mother dominated in that area. Participant A cannot integrate himself in this traditional narrative of the house and it causes him to make his room the most private space in the house. He uses his room to isolate himself from normativity of the house. Although he calls his room a calming and comfortable space, it is still influenced by other spaces at home. It doesn’t feel him completely free. The fact that this isolated space is still affected by other forces in the house makes the space not completely safe. This is a space where participant must limit his queer identity there. For instance, his room is not a safe place to come with his partner.

Hospitality plays an important role in Turkish culture like dinner or tea events, cooking events etc. All these cultural events gather all families, relatives or friends together. Gatherings at house temporarily change structure of the house and participant related this temporary change with intimacy. The organization of space is temporarily transformed, identity of space gets blurred, and normativity gets lost. When he imagines his future house, he wants an enclosed, non-door space where he can express himself and hosting his friend at that house is an important part to feel intimacy at house.

He also considers that some flexible spaces that do not guide some users as intimate spaces like some night clubs. These are the spaces that are activated by only bodies. He especially prefers to go to pubs specifically for the marginalized community because queer pubs are places where he can more clearly express their sexual identity and interact with other people. At this point, he compares queer pubs where he went in Rotterdam and Istanbul, even he finds both are intimate spaces, he feels more belong to space in Istanbul. Because queer pub in Istanbul is also place where he can integrate his cultural identity to the space unlike Rotterdam. The semi-open spaces connected to the main space make him relax because these spaces give him chance to choose his comfort zone. This relationship

19

is similar to the relationship of the participant's own room with the other places in the house.

The characteristics of the public space, where the participant will feel safe with their partner, are either a very isolated space where only the two of them can be, or a space so crowded that it cannot be noticed. On that point, green public areas like parks come to the forefront. Because these spaces are timeless because certain hours, forces in city center don’t influence these flexible spaces.

His own room, which is the most private place in the house, is also his spiritual space because he prefers to perform his religious rituals in an isolated space. Religious rituals, both in the public and private, are an activity he wants to hide because since he cannot relate himself to the religion imposed at home and also, he studied catholic school where he had to hide his Muslim identity when he was child.

20

21

Description of Participant B Map

Participant B is 26-year-old queer Muslim women. She was born and raised in Rotterdam. She is currently working and living in Rotterdam. She moved from her parents' house as soon as she became 18. The most important reason to make this decision is that she limits herself in space and doesn’t feel free and safe. That’s why since she was child, living away from parents is one of her plans and this caused her to feel no belonging to the family house. She especially mentions about the difference between two different houses when he lived with his family. She associates the house where neighbours are relative with coziness because of the gathering at house. She underlines hospitality at that point and it is one of the concepts that she brings this with her to the house where she lived on her own. Dinner events or tea in her own house is an important activity for her because this is a way to interact with people. The fact that the participant prefers the kitchen as a shared space also comes from her cultural background because cooking together is an important interactive activity in Turkish culture. In her current house, she is sharing her kitchen with someone, and she has personal room and doesn’t have a living room. He finds her kitchen as intimate space where she can have dinner together with her roommate. The absence of a participant's living room affects the organization of her room because she creates intimate spaces while putting huge couches in quite small space. Intimacy and hospitality are significant elements in her private space. In this way she can temporarily transform her private room to gathering, intimate space and at the end this temporal space is placed at intersect with her sexuality and cultural identity. Furthermore, there is also some object that she reflects her identity in the house like Turkish and pride flag, tea maker, Turkish football team plates etc.

The biggest difference between the participant's family house and her current house is that the house she lives in now is a space where she can make her own decisions, express herself and control the around. These all differences make her current house safer than parents' house. On the other hand, public space is not always a space where she feels safe with its sexual identity. Feeling of safety depends on time hours in public space. For Turkish queer women, public spaces make them feel under the gaze of cis-gender man. She especially mentioned about one of the coffee places where she can feel cozy and comfortable. This place is a very welcoming cafe with

22

queer staff and symbols. This place is a safe space in public where she can go with her partner, and she integrate this place with intimacy.

Pride is quite important to visibility and at that time the public spaces temporarily transform and occupied by marginalized community. She feels more powerful and visible in public space. However, this gathering in public also brings unsafety feeling. Being more visible makes her feel more threatened by homophobia.

Green open areas are separated itself from normative public spaces and give her chance to express her identity and feel freer. She describes these spaces fluid and become by intimate circles. This space can be considered as a safe space where she can interact with her partner freely because there is no specific function in the space makes it flexible and open to user expression.

23

24

Description of Participant C Map

Participant C is a 29-year-old queer Turkish man. He is an actor. He was born in Winterswijk which is one of the small towns in the Netherlands. His interaction with the outside in this city was quite limited. In his cosy memories of the city, the markets or shopping places he went with his mother stand out. Generally, in the Turkish family structure, the father, that is, the man, is the dominant character of the house. However, after the divorce of his parents, the participant was forced into a situation where he had to take control of the house as the eldest male member of the home. This situation reduces his communication with the house as his taking this role forcibly causes his to feel the normative structure in the house more.

He defines his room in the family house as the space where he is isolated and spends the most of his time at home. Limited interaction with the outside, normativity inside the house pushed him to discover a new interaction space which is digital world. This digital space is a way to escape from the identity that he has to show at home. In this digital field, the participant finds a space where he can express himself freely and without norms by creating different personas and different places every day. Due to this digital space, the person discovers that there can be fluid identities and spaces apart from the fixed identity and use of space coming from the family. Although he does not feel a sense of belonging to a physical space, a sense of belonging appears to the spaces and personas he creates and constantly changes in the digital space. That’s why he doesn’t feel himself completely belongs to any physical space and he describe himself as a nomadic person. As soon as the participant turns 18, first he moved to Utrecht, then lived in Arnhem for a while and currently is living in Amsterdam. Obviously, he does not like to live in a same place for a long time.

After moving from a small city to a big city, he had the opportunity to discover himself more, and to express his queer identity especially as his interaction with people increased. The participant often spends his time in performance spaces such as the stage, as the theatre enters his life. Because the stage is a place that accepts every persona played by the person, so it can be considered that this is a non-normative space. The stage is also a space where he can freely express his intersectionality. For instance, the stage is the first place where he came out about his queer identity to his family. The participant also both writes script and plays at theatre, and he

25

especially prefers to highlight his queer identity in the play. The fluidity in both spatial and persona is dominant in the plays but at the same time, the Turkish identity of the person generally takes a part in the plays. For instance, in the last play, we are seeing him variable personas and one of them is a female character who dances while singing a Turkish song. His use of stage is the temporal expression of his intersectional identities.

The participant specifies two places in Amsterdam while talking about the night use of public spaces; Leidseplein, which is the square, and Reguliersdwarsstraat, which is the street. When he compares between two, he describes Leidseplein as a place where he doesn't feel comfortable as he exposes it to dualities and sees it as an aggressive public space. On the other hand, in Reguliersdwarsstraat, a place welcoming to queer identities, he states that he feels safer than in other parts. At the same time, in recent years he prefers places such as open spaces and festivals to queer clubs to have fun because he thinks it is a more comfortable and free space. As an indoor space, he finds the home environment more intimate and comfortable with friends whom he feels comfortable and can freely express himself. In particular, he considers that dinner or tea activities is a way to create this atmosphere and interaction in which he can feel comfortable and safe.

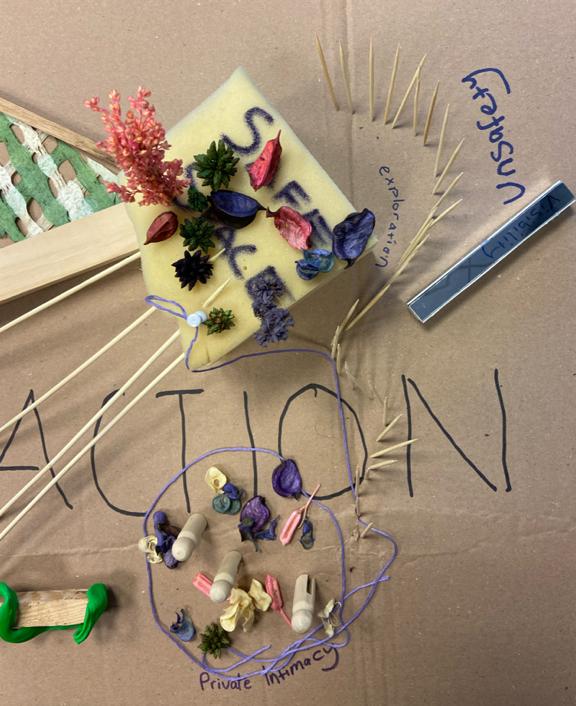

4.2. Co-creative Collage

As the second part of the methodology, we organized a workshop with the participants, where we could discuss the space of betweenness while using different materials. The purpose of our work with different materials is to better explore the spatial character of the space of in-betweenness. Participants decided the rules, materials and space of the workshop themselves. During the workshop, we were inspired by the conceptual maps we prepared together with the participants about the space of in- betweenness based on their spatial experiences. In this workshop, which we imagined as a place-making collage using different materials, we had the opportunity to think about this in-between space in more 3D way and with different layers.

26

27

At the beginning of the workshop, when we talked about the maps we prepared before, we decided that interaction is the main key word. Our discussions started on this concept. We focused on the question that how space influences interaction or how interaction influences space. Interaction is sometimes produced within the boundaries of space, and sometimes it affects existing spaces on its own. The interaction produced by the influence of physical boundaries forces the space to interact, which changes the fixed identity of the space temporarily and gives fluidity to the space. In some cases, these boundaries also cause forced interaction and make space where one cannot feel free and express themselves clearly. Especially in the experiences of each participant in the family house, we can see that the interaction limits the person as a spatially. At this point, the concept of isolation emerges. One's own room can be given as an example of an isolated space, but the relationship of this isolation with interaction is gradual. That’s why in the collage isolation consists of layers that go from transparency to opacity. Even isolated spaces within these borders are still under the influence of forced interaction.

28

A completely safe space is seen as a utopian concept by the participants. The materials used for the safe space, being natural, fragrant and soft, associate this place with the concepts of intimacy, coziness and comfort. Safe space has a relationship with the concept of interaction in many ways. First, the sticks that come out of the interaction penetrate the safe space and influence it in a bad way.

Secondly, a relationship is established in a smooth way through an intimate circle formed by interaction. The intimate circle we created on the concept of interaction is inspired by the concept of gathering on maps. Especially the cultural gathering events that take place in the house affect and transform the space through interaction, bringing a different relationship to the concept of interaction with the safe space.

29

Another relationship is the interaction that relates to the boundaries of the safe space. While the participants were thinking about some places located on the edge of the safe zone, they considered it as space of exploration. At this point, the queer pub they went to in Turkey pushes them to create this composition in collage. Although the interior of this place gives people the opportunity to be there with their sexual and cultural identities, the outside of the place also makes them feel so insecure. Visibility inside the space reveals the sense of belonging to the space, but outside the space, this visibility makes the public space dangerous.

In the public spaces of the city, the places where you can feel peaceful with intersectional identity are limited. However, although some spaces are under the influence of public streets, squares and public spaces where heteronormative power is felt, there are intimate spaces that have established a non-normative structure within themselves. In this collage, these spaces where people can express their sexual and cultural identity can be associated with parks, festivals and queer welcoming cafes. The reflective material at the intersection of the tires represents this visibility. Participants also highlight their universities in public space. They see this educational space as a structure that filters the user in the public sphere. The fact that a space accessible to everyone has a specific function and that this function is

30

based on education limits the users of the space in the public space without the need for a physical boundary. It allows people to freely express their identities in space. Performative spaces likewise promote visibility and allow for fluidity in space and person. That's why this space also represented reflective material in the collage.

When we discussed about spiritual spaces in the workshop, we realized that it actually has a very complex and layered structure. Religious rituals that take place in the mosque, which is a spiritual space, is actually a non- normative activity. In other words, we considered that the mosque was a place where you left your identity and who you are behind and only went there to find peace. In fact, it is the place where you should be able to express yourself most clearly, but the spatial forces and binary organization of the space force you to choose, that's why it makes this spiritual space into a normative space.

31

At the same time, we use the spiritual space in the part that represents the most isolated place of the collage, because the religious forces that have been applied to us since childhood cause us to be unable to relate to the ituals performed collectively, and we establish a different relationship with the itual in the private

32

5.Findings

5.1. Synthesis

First of all, when we look at both the conceptual maps and the collage, it would be a correct approach to consider the space of inbetweenness from two different perspectives, one that emerges in private spaces and the other one that emerges in public spaces.

In private spaces, there is a tense relationship between Turkish family homes and homosexuality in the Netherlands. This tension brings both a sense of belonging to home and alienation for Turkish queer individuals. The home is not a safe place for them because, according to the participants, the safe space is where you can freely express your intersectional identity. The concept that the participants highlighted most about their experience in the family house is hospitality. The concept of hospitality in Turkish culture is a value that is in the traditions of Turkish society, that is, shared by the community. That’s why hospitality takes its place in this society within the framework determined by this tradition and culture. In Turkish culture, the guest is very important, the they are a part of their daily life. Moreover, one of the first features that come to mind among the known characteristics of the Turks is their hospitable nature. Especially Turkish immigrants in the Netherlands attach great importance to gatherings at home, which is a part of hospitality, because they are a minority where they live. That's why gathering is very important for them to create a sense of belonging there and not feel alone. All the participants point out this issue while preparing concept maps together, because this is a common culture that they all experience while living in the family home. With this gathering, the normative spatial order in the house changes temporarily, and the forces exerted by the gendered spaces in the house on the person softens. The change of the spatial order enables the person to interact with the house and the participants associate this with the concept of intimacy. This characteristic feature in the family house most influenced the organization of the current queer domestic spaces of the participants. Most of the participants left their family homes as soon as they turned 18, but they brought the hospitality of Turkish culture with them to their new private spaces. In fact, this intersection is one of their ways of experiencing the space of in-betweenness.

33

In fact, food and tea events, which are a part of hospitality have an important role in Turkish culture. Especially cooking, which is a part of this event, is an activity that socializes people. Turkish food requires effort and time. Therefore, Women, in particularly, come together for this activity to both chat and cook. In fact, the culture of cooking and eating, which comes from the Turkish culture, is another way for the participants to interact with the space. In their family houses, the kitchen is the place where they spend the most time after the rooms, thus, they prefer the kitchen as a shared space in their current private spaces, or they prefer a spatial organization that kitchen interacts with the living room, because cooking is a social activity where people come together.

Another in-betweenness we perceived in private spaces is that in some cases, the limits that alienate the participants from the family home have led to fluidity in the space. As we can observe in Participant C, he spends time in his room, which he calls the most isolated place at home, since he cannot express himself either in the house or in the public space of the city and has difficulty interacting with outside of his room. However, the isolated space caused by the limits of the house pushes the person to discover a completely new place, and in this place, one is free. In this digital space, the person changes the composition of the existing static space and gives the space a new identity by creating new personas, different identities, and variable spaces.

Another feature of the most private room, which is seen as an isolated place in the house by the participants, is that it is a place where one performs spiritual rituals related to one's religion. The Muslim understanding of the Turkish immigrant community living in the Netherlands is generally not open to heterosexuality, that's why, religious rituals are not performed collectively for this community. Participants prefer their room for these rituals, which is the most isolated place. According to participants, the spiritual space should be a place where the person can express himself clearly in all aspects, since the identity of the person is not important there. Unfortunately, public religious spaces such as mosques do not allow expression because of their normative spatial organization, gendered spaces, and being a space under male control.

34

Even though the restrictions of Turkish immigrant family houses on the expression of queer Turks' identities push these people into public or semi-public spaces, people do not feel completely comfortable and safe in these spaces. The streets and squares in the city center do not allow this community to feel safe with their partners because these places are under the influence of a dominant heteronormative power. But some places separate themselves from this heteronormativity in the public and create safe and intimate spaces, such as coffee place in Rotterdam or Reguliersdwarsstraat in Amsterdam. These cafes and streets are attractive and social spaces to meet with other queer people, spend time with them and be accepted. What makes them attractive is that they use symbols of queer identity such as the rainbow flag, have queer employees and organize queer artistic and cultural events. Moreover, these places are still placed in public spaces and interact with the public.

Another place where we observe in-betweenness is performative spaces such as the stage. The stage in the theater allows fluid, temporal spaces and personas and it temporarily plays with the perception of time we experience daily. Thus, performative spaces that are seen as static and permanent transform into fluid, unstable and flexible boundaries by interacting with people's bodies and even their intersectional identities. It can be said that these places are nonnormative and where people can express themselves clearly. For example, Participant C who is an actor, came out to his family on stage in his own play, because stage is a space where he is at peace with himself and freely expresses his identities.

The universities of the participants are located at the city center and although there is no physical border to the public, the educational function of the place creates invisible boundaries in the public space. The users who experience the space consist of a community open to multiple identities, without prejudice. This helps the participants to be more secure and visible in space. Because the academic environment at the university, the communities, allows these individuals to engage in activism for their intersectional identities. The university which is the part of the public space becomes a place where this marginalized community can express themselves freely.

35

It can be said that the streets and squares in the city center are affected by the time limit because they are directly influenced by the opening and closing hours of the other places, but the parks are timeless spaces in the public space. The fact that the parks are reproduced with different actions every day, with the users changing every day, and the temporality of the spaces customized by the individuals can also be defined as a queer way of resistance. Parks could be controlled if they were designed and used for a particular user, for a specific action, to be used at a specific time. However, parks provide support to queering in general as a place that is open to all users, provides space for various actions and can be used at any time. All these activities hosted by the park are done by different people at random points of the park, in a random time period; The park has a very dynamic organization. That’s why, the act of sitting on the grass, with the contribution of the topography, allows various body positions. On the other hand, while these comfortable positions allow people to socialize more easily, it also provides more potential for physical intimacy between individuals compared to people sitting on opposite chairs in a cafe. It can be seen these potentials as a means of getting out of norms.

36

37

5.2. Limitations

Although I thought the participant research method was the most appropriate and ethical method for such a sensitive subject, the biggest limitation of this research was the dependence on the participants. I started to find my subjects with my search for organizations that brought together the queer Muslim Turkish community in the Netherlands, but while searching, I observed that these organizations were very limited and not active enough. At the same time, they couldn't response to my request about collaborative research. I tried to personally reach the subjects that I saw potential through social media. I couldn't get any response from some of them, although some people reacted in a positive way while finding my research topic important and interesting, they said that they don't have enough time to work together. If my research method had been based on an interview with the subjects, I could have had more participants because co-creation and co-research required time, effort, and labor. That’s why I could not find enough interest and motivation from the subjects. At that point, maybe if I had a budget to pay them off for their labor and effort to research together, I could reach more participants.

Even though I have a Turkish identity, I came across with limitations when I contacted potential subjects because I was perceived as a heterosexual, cisgender woman, outsider who had just moved to the Netherlands. The subjects who agreed to research together are between the ages of 23-30. If I had the opportunity to work with more diverse age groups, maybe we could have come up with different findings, because especially young Turkish immigrants living in the Netherlands had difficulty in relating the space of inbetweenness with their immigrant background, since they did not feel a sense of belonging to Turkey. However, this situation could have changed if I had worked with an older group, and it could have brought different spatial findings to the research. Finally, it was very difficult to agree with the participants on a common time slot for both co-creative mapping and co-creative collage, and it was a challenging situation that limited the research process. 6.Conclusion

38

This research aimed to unfold spatial characteristics of inbetween spaces influenced by Turkish queer immigrants’ experience on intersectionality in Netherlands. Multiple identities and belongings of Turkish queer immigrants marginalize the community. That’s why, the discussion about spatial experience of in-betweenness by this community is a crucial point for this research paper. Space of inbetweenness which is experienced by this community with their intersectionality is one of the issues that should be considered in the design in order to get away from some prejudices, norms and limitations. Because it allows fluidity, expression, heterogeneity which reproduces interactions, relations, temporality to not feeling alienated in space.

Paper revealed that how Turkish queer immigrants configurated their in-between spaces which are caused by presence of public and private pressure on this community. Space of inbetweenness has no representation with a fixed space. This space can only be read through the experiences influenced by intersectionality of this marginal community through existing spaces. On that point, research led by marginalized community was essential in this paper to social equity. Turkish queer immigrants in Netherlands are a community that are not physically represented in formal architecture. However, my enthusiasm about this topic requires ethical enforcements because of not being in this community but doing research on this community. At that point, design justice inspired me to reconsider the research process. That's why I believe that collaborative and creative research are the most outstanding methods to approach the challenges this community faces in public and private spaces. In this research, each of the participants is in the position of a researcher by participating in the process with their own experiences and the voices of those who are directly affected by the research outcomes stand at the center. Working with community is crucial to reveal spatial organizations that are not physically represented in formal architecture and emerge by intersectionality of these people and provide social equity in research. Moreover, this also leads to inclusive design.

In the research, instead of creating a new space, it is aimed to find out which features in existing spaces help us understand the inbetweenness within the framework of this community by looking at the current spatial organizations. Community of Turkish queer immigrant

39

are carriers of intersectional knowledge and experience and space of in-betweenness is a zone that they resist to exclusionary and oppressive practices that affect them. In order to understand this space, it is necessary to discover the relationship between this inbetweenness and the boundaries that create it. Although the concept maps we prepared based on the spatial experience of the participants in the first step of the methodology emerged the in-betweenness experienced by each user differently, it revealed the spatial organizations affected by common concepts such as timelessness, intimacy, hospitality, isolation. Because although each user's definition and experiences of in-between space is different, the identities of the limit they are stuck in are the same.

In co-creative collage, which is the second step of the methodology, using different materials with the participants supported the layered exploration of the in- between space which represents an abstract concept. It can be said that space of in- betweenness is a threshold which has vital features. It has the feature of separating the different sides from each other, it also carries the possibilities of bringing, merging and hybridizing them together. In this field, the separate identities reunite, and the differences become distinguishable. In this way, it blurs the boundaries and fuses the features of the sides it separates from each other.

This study made me reconsider my position as a designer. In spite of limitations of design justice that I face in the process, I perceived that community marginalized by design must be one of the co-creators of the both design and research process to social justice. As I questioned power and hierarchy in this academic research, I will continue to negotiate these relations in my future career.

40

7.References

Ahmed, Sara (2006) Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, Durham: Duke University Press.

Akpinar, A. (2003). ‘The honour/shame complex revisited: Violence against women in the migration context’, Women’s Studies International Forum, vol. 26, n. 5, pp. 425 - 442.

Avar, A. A., (2009) “Lefebvre’in Uclu -Algılanan, Tasarlanan, Yasanan Mekan- Diyalektigi”, Dosya 17, TMMOB Mimarlar Odası Ankara Subesi.

Bergson, H. (1986). ‘’Matiere et memoire’’; Traslation: Erguden, I., (2005). Madde ve Bellek, Dost Kitabevi, Ankara.

Bergson, H., (1901). ‘’L'Evolution creatrice’’; Translation: Andison. M. L., (1946). Creative Mind, New York: Philosophical Library; Ceviren: Tunc, S.M., (1947). Yaratıcı Tekamul, Dergah Yayınları, Istanbul.

Butler,J. (1999). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity,New York: Routledge.

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020), Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, The MIT Press.

El-Tayeb, F. (2012). ‘Gays who cannot properly be gay’: Queer Muslims in the neoliberal European city. European Journal of Women's Studies, 19(1)

Fortin, S. (2002). Social ties and settlement processes: French and North African migrants in Montreal.Canadian Ethnic Studies,34 (3), 76-97.

Grosz, E., (2001). Architecture From Outside, Massachusetts Institte of Technology, USA.

41

Jivraj, S., & De Jong, A. (2011). The Dutch homo-emancipation policy and its silencing effects on queer Muslims. Feminist Legal Studies, 19(2), 143.

Keuzenkamp S (ed.) (2010) Steeds gewoner, nooit gewoon. Den Haag: SCP – Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Lefebvre, H., (1974), The Production of Space, Blackwell Publishing, USA, UK, Australia.

Lykke, N. (2003). Intersektionalitet - ett anvandbart begrepp for genusforskningen. Kvinnovetenskaplig tidskrift. Vol. 24 (1), pp. 47-56

Mepschen, P., Duyvendak, J. W., & Tonkens, E. H. (2010). Sexual politics, orientalism and multicultural citizenship in the Netherlands. Sociology, 44(5), 962-979.

Retter,Y., Bouthillette A., Ingram, G.B., (1997) Queers in Space: Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance Paperback, Bay Press; First Edition.

Yucesoy, E. (2006), Everyday urban public space: Turkish Immigrant Women’s Perspective

Yorukoglu,I.(2014), Acts of Belonging: Perceptions of Citizenship Among Queer Turkish Women in Germany

42

43 .