37 minute read

Feature: Glucocorticoid Induced Osteoporosis

Management of Glucocorticoid Induced Osteoporosis

Introduction

Glucocorticoids are currently an indispensable part of the treatment approach to a wide variety of medical conditions. While generally extremely effective, at least temporarily, the multitude of attendant adverse events associated with glucocorticoid use should see them viewed as “our best of drugs, our worst of drugs”. These adverse events included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, infection, weight gain, muscle weakness, and of particular relevance to the current conversation, osteoporosis and increased fracture risk.1

Glucocorticoid effect on bone

Glucocorticoids are an essential part of the physiology of the normally functioning human body. Conceptually many glucocorticoid induced adverse events can be thought of as an amplification of the normal physiologic roles of glucocorticoids. Glucocorticoids induce an early high bone turnover state. The consequences of this can be rapid and profound with increased fracture risk evident within three months of glucocorticoid initiation. If glucocorticoids are continued over a prolonged timeframe this switches to a low bone turnover state with a net loss of bone strength due to a more marked effect on synthesis than resorption. The highest rate of bone loss occurs within the first 3-6 months of glucocorticoid use however bone density continues to progressively decline at a slower rate with ongoing treatment.2 Both higher daily glucocorticoid dose and higher cumulative glucocorticoid dose are associated with a progressive increase in fracture risk.

Written by Dr Richard Conway, Consultant Physician & Rheumatologist, St James's Hospital

DXA

While glucocorticoids will reduce bone mineral density as measured by DXA, they also increase fracture risk independent of bone mineral density. Therefore, at any given bone mineral density, the fracture risk is increased in individuals receiving glucocorticoids. This is reflected in the incorporation of glucocorticoids in the FRAX fracture risk prediction model. While the majority of individuals receiving long-term glucocorticoids should have a DXA scan performed, it is of greater importance to perform a clinical fracture risk assessment, using a formalised tool such as FRAX or using clinician gestalt. Those identified as being at moderate or high risk of fracture should be treated as osteoporosis irrespective of DXA results.

Minimising Fracture Risk

A key concept that must not be forgotten is that the clinical end point we care about in osteoporosis care is fracture. Osteoporosis does not cause symptoms in the absence of fracture and while it may be slightly disingenuous to suggest, the perfect osteoporosis treatment would reduce fracture risk to zero and its effect on bone mineral density would be irrelevant. The management of osteoporosis frequently focuses on medication strategies to increase bone mineral density, while these are important, they are only one component of the approach to minimising fracture risk. While osteoporotic fragility fractures can occur with minimal or no trauma, falls remain an important and neglected aetiologic factor in many fractures, particularly non-vertebral fractures. Strategies to reduce falls in terms of muscle and balance strengthening exercise as well as minimisation of environmental and other risk factors for falls have the most immediate impact in terms of fracture reduction. Smoking cessation, alcohol moderation, and the appropriate management of other active contributory medical conditions are all important elements to osteoporosis management.

Improving Bone Mineral Density Getting the Building Blocks Right

Bone is a complex biomechanical structure, and as with the construction of any structure, it is necessary to have the correct building materials for the job. The importance of calcium and vitamin D to bone health has long been appreciated. What is less well recognised is that the importance is in having adequate amounts of these, and that more is not necessarily better and may even be harmful. Excess calcium has been associated with increased cardiovascular disease and excess vitamin D with ureteric stones.3 This leads to the fundamental concept that calcium supplementation is for individuals with calcium deficiency and that vitamin D supplementation is for individuals with vitamin D deficiency. Thankfully we have a reliable method of measuring vitamin D sufficiency, using serum vitamin D levels. Calcium is more complex, in that serum calcium does not reflect total body calcium. Our physiology requires serum calcium to be tightly regulated, and therefore the body will sacrifice all other reserves of calcium, particularly the bones, in order to maintain serum calcium in the normal range. Adequate calcium intake is best assessed by performing a calcium intake questionnaire with patients. If dietary calcium intake is insufficient it requires supplementation. By far the best source of supplementation is by increasing dietary intake through increased calcium rich foods. If this is not possible or practical then calcium supplements can be utilised. Vitamin D insufficiency is slightly trickier as the best source is from sunlight, something which is both conspicuously absent in Ireland and which carries risks with increased exposure, namely skin cancer. Therefore, serum vitamin D deficiency is usually best managed by supplements. There are two approaches to this, one is to start a standard dose supplement and increase the vitamin D slowly to sufficiency. Another approach is a loading dose approach, with an initial high dose for the first 6 weeks and then a standard dose. There is little evidence that either approach is superior, and aside from the setting of severe deficiency, the standard dose approach is usually more practical. Whichever approach is used, a subsequent recheck of serum vitamin D to ensure the success of supplementation leading to repletion is essential. Adequate dietary protein intake is also crucial in maintaining bone health, with recent data emphasising the importance of sufficient protein consumption in preventing falls and fractures.4

Affecting Bone Remodelling

A basic tenet of the approach to glucocorticoid use is that it is far easier to prevent bone loss than to reverse it. While not every patient on glucocorticoids requires pharmacologic treatment, many do, Figure 1. This is particularly true for those who have other risk factors for fracture including increasing age. This risk stratification is complex and individualised. In terms of treatment choices there is one important consideration in terms of which medication to choose when selecting a preventative treatment for glucocorticoid induced osteoporosis. This resolves around the anticipated duration of glucocorticoid exposure. There are three main groups of pharmacologic treatments used in this setting, the anti-resorptive agents of bisphosphonates and denosumab, and the bone formation stimulating teriparatide. Bisphosphonates are favoured in the setting of expected temporary use for a number of reasons, especially due to their prolonged beneficial effects after stopping the agent due to their incorporation in bone. Essentially this means, that in individuals who do not have co-existent osteoporosis for other reasons, that the majority of the time, the bisphosphonate can be stopped when the glucocorticoids are. Similarly, as the duration of steroid use will often be 1 year or less, an oral bisphosphonate rather than an annual intravenous infusion is more pragmatic. Denosumab, which inhibits RANKligand has a particular concern with its use, in that it has a rapid off effect once ceased with an associated precipitous drop in bone mineral density. This is the reason that drug holidays are not appropriate in individuals receiving denosumab, and is also a concern around the potential short term prophylactic use in the setting of glucocorticoids. Teriparatide, is a daily injection for 2 years, and

Figure 1

Long-term glucocorticoids

Ensure calcium and vitamin D sufficiency Address other fracture risk factors

Low risk Moderate/High Risk

Monitor BMD Age < 40 Age ≥ 40

History of Fragility fracture OR Z-score <-3 OR >10% year BMD drop OR High dose glucocorticoid and ≥ 30 Fragility fracture OR Age ≥ 50/Post-menopausal and Tscore ≤ -2.5 OR FRAX ≥ 10% major fracture or ≥ 1% hip fracture OR high dose glucocorticoids

Bisphosphonate (or alternative) Bisphosphonate (or alternative)

must be followed by an antiresorptive, again in the setting of non-permanent glucocorticoid use, this is a less attractive option.

Determining the Need for Continuing Treatment

As a general rule, most individuals need to continue their bone prophylaxis as long as they remain on glucocorticoids, and certainly as long as they are >5mg/ day prednisolone equivalent dose. Osteoporosis is incredibly common with half of women and one quarter of men suffering an osteoporotic fracture during their lifetime. Osteoporosis is also very much a hidden disease with the majority of individuals undiagnosed until they suffer the end consequence of a fracture. Many individuals undergoing glucocorticoid treatment meet screening criteria for DXA, but even in the absence of this should undergo bone density assessment prior to consideration of cessation of bone prophylaxis.

Guidelines

Excellent guidelines exist for the prevention and management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, for example the American College of Rheumatology guidelines.5 However, glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis is a variable and complicated condition and every patient requires individualised assessment and management. It is also a condition where we are operating with very significant limitations in data. Due to this the existing guidelines can be difficult to interpret with large amounts of information and discussion. In clinical practice we see vastly more patients undertreated than overtreated. The default position should be that each individual on long-term glucocorticoids aged 40 years or older requires treatment, including a bisphosphonate, and reasons should be found to justify not doing this. As this is a complex area, if there is any doubt, specialised referral to a bone health service is encouraged.

Summary

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis is a significant health problem with high rates of the negative consequence of fracture. Many of these fractures are preventable with appropriate management. All individuals receiving long-term glucocorticoids require fracture risk assessment and nonmedication strategies to improve bone health. The majority of those aged 40 years or older receiving long-term glucocorticoids will also require a bisphosphonate.

References

1. Proven A, Gabriel SE, Orces

C, O'Fallon WM, Hunder GG.

Glucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: duration and adverse outcomes. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2003;49(5):703-8. 2. Laan RF, van Riel PL, van de Putte

LB, van Erning LJ, van't Hof MA,

Lemmens JA. Low-dose prednisone induces rapid reversible axial bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled study. Annals of internal medicine. 1993;119(10):963-8. 3. Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA,

Grey A, MacLennan GS, Gamble GD, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: metaanalysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2010;341:c3691. 4. Iuliano S, Poon S, Robbins J, Bui

M, Wang X, De Groot L, et al. Effect of dietary sources of calcium and protein on hip fractures and falls in older adults in residential care: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2021;375:n2364. 5. Buckley L, Guyatt G, Fink HA,

Cannon M, Grossman J, Hansen

KE, et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced

Osteoporosis. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ). 2017;69(8):1521-37.

Persistence with oral bisphosphonates and denosumab among older adults in primary care in Ireland

Authors: Mary E. Walsh1 http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8920-7419 | Tom Fahey1 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5896-5783 Frank Moriarty1,2 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9838-3625 Affiliations: 1HRB Centre for Primary Care Research, Department of General Practice, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland | 2School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland

Osteoporosis and associated fragility fractures can result in significant disability, morbidity and mortality with 20% of individuals who experience a hip fracture dying in the first year.1, 2 It is estimated that one in five women and one in twenty men over the age of 60 have osteoporosis and 3% of older adults are expected to experience fragility fractures annually.3, 4 Adults at high fracture risk, including those with osteoporosis, previous fractures or those who take medication that reduces bone quality, should be offered pharmacological treatment where no contraindication exists.5-8 Oral bisphosphonates have been shown to prevent fractures in men and women and they are the most cost-effective initial therapy for osteoporosis.6, 8, 9 Denosumab, a newer antiresorptive treatment, involves six-monthly administration by subcutaneous injection, usually administered by a healthcare professional. It is recommended in patients with high fracture-risk where they are unable to take oral bisphosphonates due to difficulties with administration or intolerance caused by upper gastrointestinal symptoms.6-8 Denosumab has been shown to prevent fractures in women.7 While research in men remains limited, it improves bone mineral density (BMD) and has shown an effect on fracture incidence in particular cohorts.7, 9, 10 To be cost-effective and result in optimal fracture reduction, it is important that oral bisphosphonates and denosumab are prescribed and taken/administered correctly, at the appropriate time intervals, without unwarranted gaps in treatment or early cessation.11, 12 Adherence (the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose regimen) and persistence (the accumulation of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy) have both been found to be suboptimal in oral bisphosphonate and denosumab use.13, 14 Clinical guidelines recommend that bisphosphonates are continued without a break for a period of at least three years and for up to ten years in those deemed to be at high risk of fracture.6,15-17 However, a large recently published systematic review found that 2-year persistence for oral bisphosphonates was less than 30% in most studies and that only 35% to 48% of patients are adherent at 2 years [13]. Persistence in denosumab treatment is particularly important, as the suppression of bone resorption rapidly reverses where treatment is delayed by as little as three months.18, 19 There is some evidence that this could result in rebound vertebral fractures.20 A recent systematic review including 16 studies of denosumab showed that average 2-year persistence was only 55%.14 Treatment with oral bisphosphonates after stopping denosumab is protective against negative effects in most patients after one year of treatment, however stronger replacement treatments may be required for patients taking denosumab for longer periods.21, 22 Internationally, General Practitioners (GPs) have reported uncertainty about prescription breaks in bisphosphonate treatment and cessation of denosumab.23 Recent estimates of persistence for these medications are not available in primary care in Ireland and so the extent of the problem in the Irish setting is unknown. Furthermore, identification of factors associated with early discontinuation of these medications in a large representative primary care database could reveal circumstances in which education or input from specialists would be warranted.

Study objectives

The aim of this study is to estimate persistence rates for oral bisphosphonates and denosumab in a cohort of older primary care patients in Ireland who are newly prescribed these medications and to identify factors associated with time to discontinuation.

METHODS

Study Design

The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement was used in the conduct and reporting of this retrospective cohort study.24

Setting and data source

Data were collected as part of a larger study from 44 general practices in the Republic of Ireland in the areas of Dublin (n=30), Galway (n=11), and Cork (n=3) using the patient management software Socrates (www.socrates. ie) between January 2011 and 2017 [25, 26]. Data, anonymised at the time of extraction, included demographic, clinical, prescribing and hospitalisation records of patients who were 65 years and older at the date of data extraction (2017). Ethical approval was

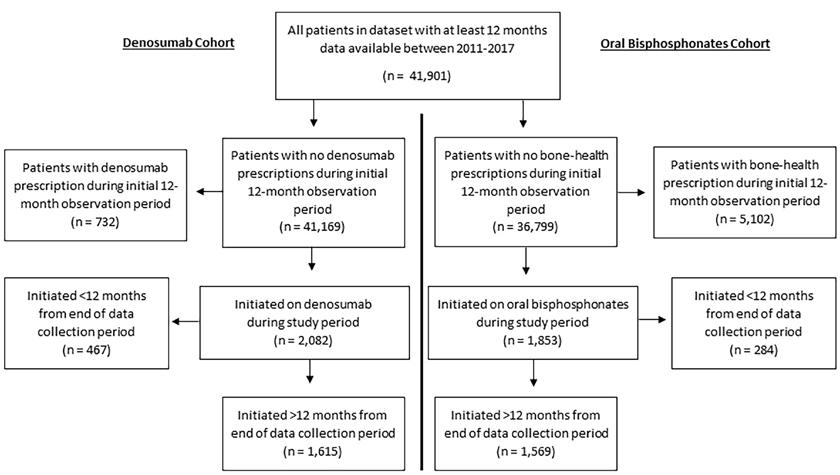

Figure 1. Flow-diagram of patient selection

DON’T WAIT UNTIL OSTEOPOROSIS STRIKES AGAIN

Rebuild bone before it breaks again—with Movymia®1

MOVYMIA®: THE NEW TERIPARATIDE BIOSIMILAR FROM CLONMEL HEALTHCARE

RELIABLE: Movymia®’s quality, safety and efficacy is highly similar to its reference product1,2,* EFFECTIVE: Anabolic MoA effectively rebuilds bone through the stimulation of osteoblasts1,3 AFFORDABLE: Allows more eligible patients to benefit due to its cost advantage4,5 RE-USABLE: One high quality reuseable pen for the entire treatment period1

MOVYMIA 20 MICROGRAMS/80 MICROLITERS SOLUTION FOR INJECTION

Each dose of 80 microliters contains 20 micrograms of teriparatide. One cartridge of 2.4 ml of solution contains 600 micrograms of teriparatide (corresponding to 250 micrograms per ml). Presentation: Glass cartridge. Indications: Movymia is indicated in adults. Treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and men at increased risk of fracture. In postmenopausal women, a significant reduction in the incidence of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures but not hip fractures has been demonstrated. Treatment of osteoporosis associated with sustained systemic glucocorticoid therapy in women and men at increased risk for fracture. Dosage: The recommended dose is 20 micrograms administered once daily. Patients should receive calcium and vitamin D supplements if dietary intake is inadequate. The maximum total duration of treatment is 24 months. The 24 month course should not be repeated over a patient’s lifetime. Following cessation of teriparatide therapy, patients may be continued on other osteoporosis therapies. Teriparatide must not be used in severe renal impairment. Use with caution in moderate renal impairment and impaired hepatic function. Teriparatide should not be used in paediatric patients (less than 18 years), or young adults with open epiphyses. Method of administration: Movymia should be administered once daily by subcutaneous injection in the thigh or abdomen. It should be administered exclusively with the Movymia Pen reusable, multidose medicine delivery system and the injection needles which are listed as compatible in the instructions provided with the pen. The pen and injection needles are not included with Movymia. However, for treatment initiation a cartridge and pen pack should be used. Movymia must not be used with any other pen. Patients must be trained to use the proper injection techniques. Contraindications: Hypersensitivity to the active substance or excipients. Pregnancy and Breast-feeding. Pre-existing hypercalcaemia, severe renal impairment, metabolic bone diseases other than primary osteoporosis or glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, unexplained elevations of alkaline phosphatase, prior external beam or implant radiation therapy to the skeleton, patients with skeletal malignancies or bone metastases. Warnings and precautions: In normocalcaemic patients, slight and transient elevations of serum calcium concentrations have been observed following teriparatide injection. Serum calcium concentrations reach a maximum between 4 and 6 hours and return to baseline by 16 to 24 hours after each dose of teriparatide. Therefore, if blood samples for serum calcium measurements are taken, this should be done at least 16 hours after the most recent teriparatide injection. Routine calcium monitoring during therapy is not required. Teriparatide may cause small increases in urinary calcium excretion, but the incidence of hypercalciuria did not differ from that in the placebo-treated patients in clinical trials. Teriparatide should be used with caution in patients with active or recent urolithiasis because of the potential to exacerbate this condition. In short-term clinical studies with teriparatide, isolated episodes of transient orthostatic hypotension were observed. Typically, an event began within 4 hours of dosing and spontaneously resolved within a few minutes to a few hours. When transient orthostatic hypotension occurred, it happened within the first several doses, was relieved by placing subjects in a reclining position, and did not preclude continued treatment. Caution should be exercised in patients with moderate renal impairment. Experience in the younger adult population, including premenopausal women, is limited. Treatment should only be initiated if the benefit clearly outweighs risks in this population. Women of childbearing potential should use effective methods of contraception during use of teriparatide. If pregnancy occurs, teriparatide should be discontinued. The recommended treatment time of 24 months should not be exceeded. Contains sodium. Interactions: Digoxin, digitalis. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: Women of childbearing potential should use effective methods of contraception during use of teriparatide. If pregnancy occurs, Movymia should be discontinued. Movymia is contraindicated for use during pregnancy and breast-feeding. The effect of teriparatide on human foetal development has not been studied. The potential risk for humans is unknown. Driving and operation of machinery: Teriparatide has no or negligible influence on the ability to drive and use machines. Transient, orthostatic hypotension or dizziness was observed in some patients. These patients should refrain from driving or the use of machines until symptoms have subsided. Undesirable effects: Nausea, pain in limb, headache, dizziness. Refer to Summary of Product Characteristics for other adverse effects. Pack size: 1. Reporting of suspected adverse reactions: Reporting suspected adverse reactions after authorisation of the medicinal product is important. It allows continued monitoring of the benefit/risk balance of the medicinal product. Healthcare professionals are asked to report any suspected adverse reactions via HPRA Pharmacovigilance, Earlsfort Terrace, IRL - Dublin 2; Tel: +353 1 6764971; Fax: +353 1 6762517. Website: www.hpra.ie; E-mail: medsafety@hpra.ie. Marketing authorisation holder: STADA Arzneimittel AG, Stadastrasse 2-18, 61118 Bad Vilbel, German. Marketing authorisation number: EU/1/16/1161/001-003. Medicinal product subject to medical prescription. Date last revised: July 2019.

obtained from the Irish College of General Practitioners.

Participants

Patients were eligible for inclusion in analysis if they were newly prescribed oral bisphosphonates or denosumab during the study period (see Figure 1). Cohorts of patients initiated on oral bisphosphonates and denosumab were defined and analysed separately, resulting in potential overlap between these groups. Prescriptions for bone-health medications were identified from two sources: GP prescription records (WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification codes) and discharge summaries of hospitalisation records (based on free-text trade and generic names). See Online Resource 1 for detailed search terms and codes.

The start of the observation period for each individual was defined as their first recorded GP consultation, prescription or hospitalisation within the dataset. For the oral bisphosphonate cohort, as it is a first-line treatment, they were defined as “newly prescribed” if they received a first prescription for a bisphosphonate and had at least 12 months of observation before this without receiving any bonehealth medication prescription (see Online Resource 1 for definition and codes). For the denosumab cohort, they were defined as “newly prescribed” if they received a first denosumab prescription and had at least 12 months of observation before this without a denosumab prescription.

Estimate of persistence

Persistence was defined as the time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy.13 Discontinuation was considered to have occurred if there was a gap in coverage of prescriptions of more than 90 days. This grace period ensured patients with short periods of discontinuation (e.g. due to dental procedures) or delaying in obtaining a new prescription were not classified as having discontinued. The coverage of prescriptions for oral bisphosphonates was calculated based on specified duration and number of issues detailed in GP prescription records, while each prescription of denosumab covered a six-month period (168 days). For the small proportion of prescriptions that were based on hospital discharge summaries, a six-month prescription (168 days) was assumed. All patients were observed for as long as data allowed after initiation of medication. For calculation of two-year persistence, patients were excluded if the initiation of medication occurred less than two-years before the end of the data-collection period. The number of patients who switched to an alternative bone-health medication within 90 days of the end of coverage period of the initial medication was calculated. These patients were subsequently excluded from the estimate of 2-year persistence. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to include those who switched in estimating 2-year persistence, adding persistence to their new medication to persistence to their initial medication.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical variables were described for bisphosphonate and denosumab cohorts. Two-year persistence for bisphosphonates and denosumab was calculated with 95% confidence intervals.

Factors associated with time to discontinuation

Time to discontinuation of medication was calculated in days for oral bisphosphonates and for denosumab for each patient who had at least 12 months of data after medication initiation. Patients who were found to switch to an alternative bone-health medication were excluded from time to discontinuation analysis.

Exposures

Exposures were defined during the time-period prior to medication initiation. These included age at the point of medication initiation, a record of osteoporosis, fragility fracture or calcium/ vitamin prescription in GP or hospitalisation records (Online Resource 1), number of unique prescribed medications in the 12 months prior to initiation and health cover type. Number of medications was analysed categorically (0-5, 6-10, 11-15 and >15 medications). Health cover type was grouped into three categories relevant to the Irish healthcare system based on whether patients are required to pay at the point of care: “General Medical Services scheme” (GMS, covering GP care, hospital care and medications), Doctor Visit Card (DVC, covering GP care only), and Private.27 For oral bisphosphonates, dosing frequency of medication (weekly or monthly) was also included as an exposure. For the denosumab cohort, whether the patient had been on previous bone-health medication was included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Separate Kaplan Meier curves were generated to explore time to discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates (by dosing frequency) and denosumab. Factors associated with time to discontinuation were explored using univariable and multivariable Cox regression for oral bisphosphonates and denosumab. Unadjusted and adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Confidence intervals were adjusted for clustering of patients within GP practices. Stata 16 (StataCorp. 2019) was used for analyses and statistical significance was assumed at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Participants

Figure 1 shows a flow-diagram of selected patients. From 41,901 patients, n=1,569 newly initiated on oral bisphosphonates and n=1,615 on denosumab. The majority of prescriptions were identified from GP records rather than hospital discharge summaries. In the bisphosphonate cohort, 89% (n=1,391) were prescribed a medication with a weekly regimen, while 11% (n=178) were prescribed monthly dosing frequencies. In the denosumab cohort, n=689 individuals (43% of those who initiated) had been prescribed a different bone-health medication previously, while n=926 (57%)

Figure 2. Kaplan Meier graph of time to discontinuation of bisphosphonates by dosing frequency

Lead your patients to

stronger bones with Prolia®1-4

10 YEARS DATA5

Osteoporosis is a serious ongoing condition and ongoing treatment is required.6,7,8,9*

* Prolia® should not be stopped without considering alternative treatment in order to prevent rapid bone mineral density loss and a potential rebound in vertebral fracture risk.6

PROLIA® (denosumab) Brief Prescribing Information

Please refer to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) before prescribing Prolia. Pharmaceutical Form: Pre-filled syringe with automatic needle guard containing 60 mg of denosumab in 1 ml solution for injection for single use only. Contains sorbitol (E420). Indication: Treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased risk of fractures. Dosage and Administration: 60 mg Prolia administered as a subcutaneous injection once every 6 months. Patients must be supplemented with calcium and vitamin D. No dosage adjustment required in patients with renal impairment. Not recommended in paediatric patients under 18 years of age. Give Prolia patients the package leaflet and patient reminder card. Re-evaluate the need for continued treatment periodically based on the benefits and potential risks of denosumab on an individual patient basis, particularly after 5 or more years of use. Contraindications: Hypocalcaemia or hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the product excipients. Special Warnings and Precautions: Traceability: Clearly record the name and batch number of administered product to improve traceability of biological products. Hypocalcaemia: Identify patients at risk for hypocalcaemia. Hypocalcaemia must be corrected by adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D before initiation of therapy. Clinical monitoring of calcium levels is recommended before each dose and, in patients predisposed to hypocalcaemia, within 2 weeks after the initial dose. Measure calcium levels if suspected symptoms of hypocalcaemia occur. Renal Impairment: Patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 30 ml/ min) or receiving dialysis are at greater risk of developing hypocalcaemia. Skin infections: Patients receiving Prolia may develop skin infections (predominantly cellulitis) requiring hospitalisation and if symptoms develop then they should contact a health care professional immediately. Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ): ONJ has been reported rarely with Prolia 60 mg every 6 months. Delay treatment in patients with unhealed open soft tissue lesions in the mouth. A dental examination with preventative dentistry and an individual benefit:risk assessment is recommended prior to treatment with Prolia in patients with concomitant risk factors. Refer to the SmPC for risk factors for ONJ. Patients should be encouraged to maintain good oral hygiene, receive routine dental check-ups and immediately report oral symptoms during treatment with Prolia. While on treatment, invasive dental procedures should be performed only after careful consideration and avoided in close proximity to Prolia administration. The management plan of patients who develop ONJ should be set up in close collaboration between the treating physician and a dentist or oral surgeon with expertise in ONJ. Osteonecrosis of the external auditory canal: Osteonecrosis of the external auditory canal has been reported with Prolia. Refer to the SmPC for risk factors. Atypical femoral fracture (AFF): AFF has been reported in patients receiving Prolia. Discontinuation of Prolia therapy in patients suspected to have AFF should be considered pending evaluation of the patient based on an individual benefit risk assessment. Longterm antiresorptive treatment: Long-term antiresorptive treatment may contribute to an increased risk for adverse outcomes such as ONJ and AFF due to significant suppression of bone remodelling. Concomitant medication: Patients being treated with Prolia should not be treated concomitantly with other denosumab containing medicinal products. Warnings for Excipients: Patients with rare hereditary problems of fructose intolerance should not use Prolia. Interactions: Prolia did not affect the pharmacokinetics of midazolam, which is metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4). There are no clinical data on the co-administration of denosumab and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), however the potential for pharmacodynamic interactions would be considered low. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Prolia were not altered by previous alendronate therapy. Fertility, pregnancy and lactation: There are no adequate data on the use of Prolia in pregnant women and it is not recommended for use in these patients. It is unknown whether denosumab is excreted in human milk. A risk/benefit decision should be made in patients who are breast feeding. Animal studies have indicated that the absence of RANKL during pregnancy may interfere with maturation of the mammary gland leading to impaired lactation post-partum. No data are available on the effect of Prolia on human fertility. Undesirable Effects: The following adverse reactions have been reported: Very common (≥ 1/10) pain in extremity, musculoskeletal pain (including severe cases). Common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10) urinary tract infection, upper respiratory tract infection, sciatica, constipation, abdominal discomfort, rash, alopecia and eczema. Uncommon (≥ 1/1000 to < 1/100): Cellulitis, ear infection and lichenoid drug eruptions. Rare (≥ 1/10,000 to < 1/1,000): Osteonecrosis of the jaw, hypocalcaemia (including severe symptomatic hypocalcaemia and fatal cases), atypical femoral fractures, and hypersensitivity (including rash, urticaria, facial swelling, erythema and anaphylactic reactions). Very rare (< 1/10,000): Hypersensitivity vasculitis. Please consult the Summary of Product Characteristics for a full description of undesirable effects. Pharmaceutical Precautions: Prolia must not be mixed with other medicinal products. Store at 2°C to 8°C (in a refrigerator). Prolia may be exposed to room temperature (up to 25°C) for a maximum single period of up to 30 days in its original container. Once removed from the refrigerator Prolia must be used within this 30 day period. Do not freeze. Keep in outer carton to protect from light. Legal Category: POM. Presentation and Marketing Authorisation Number: Prolia 60 mg: Pack of 1 pre-filled syringe with automatic needle guard; EU/1/10/618/003. Price in Republic of Ireland is available on request. Marketing Authorisation Holder: Amgen Europe B.V., Minervum 7061, NL-4817 ZK Breda, The Netherlands. Further information is available from Amgen Ireland Limited, 21 Northwood Court, Santry, Dublin DO9 TX31. Prolia is a registered trademark of Amgen Inc. Date of PI preparation: July 2021 (Ref: IE-PRO-0721-00001)

Adverse reactions/events should be reported to the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) using the available methods via www.hpra.ie. Adverse reactions/events should also be reported to Amgen Limited on +44 (0)1223 436441 or Freephone 1800 535 160.

References:

1. Prolia® [denosumab], Summary of Product Characteristics. 2. Cummings SR et al, N. Eng. J Med 2009;361:756-765. 3. Holzer G et al, J Bone Miner Res 2009;24(3):468-74. 4. Poole K et al; J Bone Miner Res 012; 27 (suppl1):S44 abstract 1122. 5. Bone HG, et al; Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:513-23;3-23. 6. Tsourdi E, et al. Bone. 2017;105:11–7. 7. Hernlund E, et al. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:136; 8. Kanis JA, et al. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:3–44; 9. Brown JBMR 2013 Vol28 pp746-752.

were observed to initiate directly onto denosumab. In total, 56% and 51% of the bisphosphonate and denosumab cohorts were observed to discontinue the medication. Only 9% and 6% of those who discontinued bisphosphonates and denosumab respectively were switched to a different bone-health medication within 90 days of the end of the coverage period.

Estimate of persistence

For oral bisphosphonates and denosumab, n=1,212 and n=1,146 patients respectively had at least 2 years between medication initiation and the end of data collection and did not switch to an alternative bone-health medication. Among these groups, two-year persistence was 49.4% (95% CI 46.5% to 52.2%) for bisphosphonates, and 53.8% (95% CI 50.9% to 56.8%) for denosumab. Sensitivity analysis including those who switched to an alternative medication resulted in estimates of 50.9% (95% CI 48.2% to 53.7%) for bisphosphonates and 53.6% (95% CI 50.7% to 56.4%) for denosumab.

Factors associated with time to discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates

A total of n=1,487 patients were included in the time to discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates analysis. In the n=801 patients who discontinued bisphosphonates without switching onto another bone-health medication, mean time to discontinuation was 295 days (SD=332 days). Figure 2 shows a Kaplan Meier graph of time to discontinuation of bisphosphonates by dosing frequency. Those on monthly regimens had a higher risk of discontinuation (log-rank test, p=0.02). On multivariable analysis, being 80 years or older (HR=1.26, 95% CI=1.04 to 1.52, p=0.02) was associated with a higher hazard of discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates. GMS health cover (HR=0.49, 95% CI=0.36 to 0.66, p<0.01), prescription of calcium or vitamin D (HR= 0.79 95% CI= 0.66 to 0.93, p<0.01) and being on 6-10 medications rather than 0-5 medications (HR= 0.82 95% CI= 0.69 to 0.98, p=0.03) was associated with a lower hazard of discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates. The relationship between time to discontinuation and oral bisphosphonate dosing frequency did not remain statistically significant on multivariable analysis.

Factors associated with time to discontinuation of denosumab

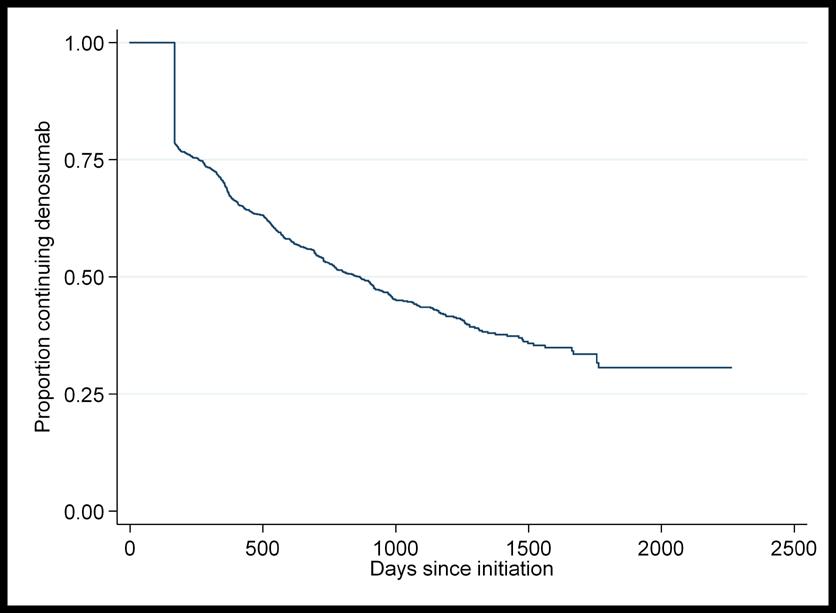

A total of n=1,568 patients were included in the time to discontinuation of denosumab analysis. In the n=782 patients who discontinued denosumab without switching onto another bonehealth medication, mean time to discontinuation was 401 days (SD=321 days). Figure 3 shows a Kaplan Meier graph of time to discontinuation of denosumab.

On multivariable analysis, no factors were found to be associated with a higher hazard of discontinuation of denosumab. GMS health cover (HR=0.71 95% CI= 0.57 to 0.89, p<0.01), and having a diagnosis of osteoporosis (HR= 0.76 95% CI= 0.69 to 0.84, p<0.01) were associated with a lower hazard of discontinuation of denosumab.

DISCUSSION

Summary of findings

This study includes a large and representative cohort of older adults in the primary care setting with a long period of follow-up between 2012 and 2017. To our knowledge, it is the first estimate of persistence in bone-health medication in a general older population in the Republic of Ireland since 2009 and the wide-spread introduction of denosumab.11, 28 Findings of suboptimal two-year persistence (49% for oral bisphosphonates and 54% for denosumab) in the current study are in line with previous research.13, 14 Having state-funded health cover was the only factor found to be protective against discontinuation of both medications. Figure 3. Kaplan Meier graph of time to discontinuation of denosumab

Findings in the context of previous research

For over half of patients in this study who were started on denosumab, it was the first bone-health medication they were observed to take, despite it not being recommended as a first-line treatment in most cases.6-8, 21 This recommendation is due in part to the cost of the medication but also due to the need to pre-screen for hypocalcaemia and co-morbidities and due to complications that arise with cessation of the drug.7, 21, 29 This pattern of prescribing reflects findings from a large primary care study in Australia where denosumab went from making up a small percentage of bone-health prescriptions in 2012 to being the most frequently prescribed in 2017.23 The denosumab cohort in this study included a higher proportion of female patients and more patients with a diagnosis of osteoporosis in comparison to the bisphosphonate cohort. This aligns with the strength of evidence for denosumab among women at highest risk of fracture.5, 7, 9 The rate of contraindication to oral bisphosphonates among this group is not known, however it is unlikely to explain the rate of denosumab prescribing as firstline therapy. Due the increased popularity of the medication among GPs in recent years, further investigation of the reasoning behind these treatment decisions is warranted.

A particularly concerning finding is that only 6% of those who discontinued on denosumab were switched to an alternative bone-health medication despite this being strongly recommended by current evidence.22 For those not switched to another medication, only 55% continued taking denosumab without a gap in treatment for two-years, which is similar to findings of a recent systematic review including 16 studies from the USA, Canada and sixteen European countries.14 Where denosumab injections are received 9-12 months apart as opposed to 6-monthly, bone turnover markers increase significantly while increases in BMD drop by over half.18, 19 A post-hoc analysis of a randomised controlled trial of 1,001

participants, also found the rate of vertebral fractures increases five-fold on discontinuation of denosumab, quickly approaching the fracture rate observed on placebo.20 While switching to oral bisphosphonates can protect against these changes in most patients, recently published results of a randomised controlled trial of 61 patients on longerterm therapy found that a single dose of zoledronate infusion was not sufficient to maintain benefits.21, 22 GPs in Australia have expressed an awareness of the quick reversal of BMD gains after stopping denosumab but also uncertainty about how and when to stop denosumab or the risks of doing so.23 It is likely that GPs in Ireland have similar concerns and education and support in this area appears to be urgently required. Poor persistence on oral bisphosphonates is also a concern. A 2011 meta-analysis of five studies and over 100,000 patients indicated that fracture risk increased by up to 40% with nonpersistence of bisphosphonates.12 In the oral bisphosphonate cohort in the current study, two-year persistence was estimated at 49% between 2012 and 2017, showing no improvement on older work.11, 28 Two previous Irish studies of bisphosphonate persistence between 2005 and 2009 showed a 1-year rate of less than 50% in patients hospitalised with a fragility fracture28 and a 2-year rate of 50% in the general older population.11 In five studies from the USA, Canada, Hungary and Sweden that were included in a recent systematic review and that measured two-year persistence using similar treatment gaps as the current analysis, estimates ranged from 19% to 46%.13, 30-34 While there is some clinical uncertainty about whether particular patients should be given a break or “bisphosphonate holiday” after 3-5 years to avoid increasing the risk of adverse events, this should not influence persistence after only two years on medication.15-17, 23 Furthermore, this cohort would be considered at relatively higher risk of fragility fracture as they have an average age of 77, a fracture history prevalence of 10% and a diagnosis of osteoporosis in 30% of the group. Guidelines suggest that among patients at high fracture risk, alendronic acid may be safely continued for up to 10 years and risedronate for up to seven years.6 It should be noted that our estimate of persistence could be optimistic as we used a conservative acceptable treatment gap of 90 days and excluded switchers onto alternative medications.13, 35 In addition, in contrast to previous research, our study did not find more frequent dosing regimens of oral bisphosphonates to be associated with discontinuation.28, 31-33, 36 In fact, on univariable analysis, monthly regimens had a higher Hazard Ratio than weekly formulations. This may reflect monthly formulations being targeted towards patients likely to have challenges persisting to the prescribed regimen. Having state-funded health cover (GMS) was the only factor found to be protective against discontinuation of both oral bisphosphonates and denosumab in this study. This relationship remained strong even after adjusting for age. This is important, as the GMS scheme in Ireland is means-tested but a higher income threshold applies to those aged 70 and over.27 For this reason, 50-55% patients in this study aged under 70 years were covered by DVC/GMS in comparison to 90% of patients 70 years and older. Such patients who have free access to GPs, practice nurses and medications may be more likely to return for repeat prescriptions, support and administration of medication (in the case of denosumab). Older age group (80 years and older) showed some association with discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates on multivariable analysis, independent of health cover, but this was not observed in the denosumab cohort. In previous literature, age has shown an inconsistent relationship with persistence of these medications with both the oldest (>75 years) and youngest (<65 years) most likely to discontinue.13, 35, 37, 38 This may be related to an increased likelihood of adverse effects at older ages or patients or physicians not prioritising treatment of fracture risk in younger patients.35 As this study included only patients who were aged over 65 by 2017, this could have resulted in higher persistence overall. In our study, prescription of calcium or vitamin D was associated with a lower hazard of discontinuation of oral bisphosphonates and having a recorded diagnosis of osteoporosis was associated with a lower hazard of discontinuation of denosumab. This could potentially be explained by ongoing osteoporosis management being reflective of the patient and physician prioritising the need for therapy, which is suggested to be an important determinant of adherence to these medications.35 Prior BMD testing, using other drugs for osteoporosis and calcium or vitamin D supplementation have been associated with better persistence in previous research.13, 36, 39 In contrast to several other studies however, a history of fragility fracture was not found to be associated with improved persistence in our analysis.13, 39 This is surprising, as one would expect a fracture experience to highlight the need for treatment and improve the management pathway. Studies in Australia and Canada have found that for secondary fracture prevention, while specialist-led programmes can facilitate better initiation of therapy, primary care physician follow-up is as effective at improving persistence.40, 41 This suggests that GPs could be supported to provide long-term management of osteoporosis in patients with fragility fracture but that once-off reviews with geriatricians could be beneficial. This requires further investigation in the Irish setting.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that we ascertained prescribing from multiple sources (i.e. GP prescription records and hospitalisation discharge summaries). We included a washout period to look at those newly initiated on medication as patients have been found to be more persistent if evaluated from their first exposure to osteoporosis therapy.42 Using routinely collected data, we were unable to assess reasons for discontinuation of medication that may have been clinically appropriate and do not know if it resulted from a risk-benefit discussion with patients. Therefore some cases of non-persistence may have been discontinuations for a clinically appropriate reason. We were also unable to determine if patients received prescriptions/ treatment (including denosumab or bisphosphonate infusion) solely from outpatient appointments with hospital-based specialists or during hospital admissions. Regardless, the very high rate of non-persistence to denosumab without observed replacement by bisphosphonates or other therapies within the primary care setting is a major concern, due to risk of rebound vertebral fractures.20 As data related to prescribing, it is not possible to determine whether prescriptions were dispensed, or if patients took their medication as prescribed. This may have resulted in an optimistic persistence rate. Finally, it is unknown, whether those “initiated” could have been finishing a “bisphosphonate holiday” or those discontinuing could have re-initiated later on. Discontinuing denosumab however has significant risks in the short-term and so looking for delayed re-initiations was not an objective of our analysis.

Clinical implications

Non-persistence/ adherence to osteoporosis medications is wasteful and can pose significant patient risks, especially in the case of denosumab treatment. Further research is required in the Irish primary care setting, given the mixed public-private health system, to explore the reasons for prescribing choices and patterns and to evaluate interventions targeted at both patients and physicians. A recent systematic review found that multi-component education programmes that included patients in the decision-making process around osteoporosis treatment and specific regimens improved medication persistence.43 A 2012 Irish analysis suggested that investing ¤120 annually per patient into interventions would remain cost-effective if they improved adherence and persistence to osteoporosis medication by just 10%.11 This warrants further testing.

CONCLUSION

This study has identified a number of areas where fracture preventive prescribing among older adults in primary care could be improved. This includes the common use of denosumab as a first-line treatment, sub-optimal rates of persistence with bisphosphonates and denosumab at two years and low rates of switching to other preventative treatments among those stopping denosumab. Free access to primary care services and medications may facilitate persistence, however other interventions targeting patients and prescribing in primary care to optimise prescribing warrant evaluation.

References available on request

Originally published in Archives of Osteoporosis 2021, doi: 10.1007/ s11657-021-00932-7.