RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERCOMMUNITY PEACE & JUSTICE CENTER • NO. 135 • FALL 2022

Blessed Are the Peacemakers • The Promise of Restorative Justice • Something Worth Striving For We Lift as We Climb • You Have to See It to Believe It • A Vision of Mutual Transformation

From the Editor

“

Restorative justice is an approach to achieving justice that resonates deeply with Gospel values and Catholic social teaching. Our tradition upholds the sanctity and interconnectedness of all human life.

Where human dignity and relationships are violated by injustice, restorative justice upholds human dignity, builds just relationships, seeks healing, promotes accountability, and enables transformation within individuals, communities, and social systems.”

—CATHOLIC MOBILIZING NETWORK

“

Justice is properly sought solely out of love of justice itself, out of respect for the victims, as a means of preventing new crimes and protecting the common good, not as an alleged outlet for personal anger.”

—POPE FRANCIS, FRATELLI TUTTI

“Happy shall they be who take your little ones and dash them against the rock!”: This line from Psalm 137 has always stuck with me—especially since becoming a parent. What crime is worthy of this sort of retribution? What kind of person can wish such an end on children?

The psalmist’s rationale becomes a little clearer when you understand that they were writing within the context of the Babylonian exile. This probably was exactly what happened to the writer’s family, friends, and acquaintances during the overthrow of Jerusalem: Children were killed, lives were de stroyed, and an entire people were sent into slavery far from their home. Is it any wonder the psalmist wished retribution on their enemies?

As much as I can empathize and even mourn with the writer, the sentiment doesn’t seem to belong in scripture. I look to the Bible for its verses on setting the captives free, feeding the hungry, and clothing the naked—working toward justice and building the kingdom of God. Rather than fomenting dreams of revenge, in other words, scripture inspires me to work to create a better world in which they can live.

And yet, this psalm, with its desperate rage and heartfelt lament, asks the question: What does justice look like in this sit uation? When a society is annihilated and sent into slavery, can justice prevail? In a nation grappling with the forced relocation of Indigenous people, the lasting legacy of slavery and the sin of racism, and the ongoing revelations of clergy sexual abuse, this question is not one relegated to the sixth century BCE but instead continues to resonate today.

This issue of A Matter of Spirit offers a potential way forward: restorative justice. Often thought of merely as an alternative to criminal justice, restorative justice offers a way forward that relies on human relationships rather than retribution. While retribution may be tempting, there is a growing understanding that punishment doesn’t address the harms done. Restorative justice, on the other hand, honors the personhood of both victims and perpetrators and builds relationships in order to foster transformation and healing.

The articles in this issue give examples of how restorative justice is already being used successfully around the country, both within our criminal justice system and in other contexts, and imagine what our world would look like if all of our relationships were governed by these principles. They show that restorative justice is not a process limited to individual relationships, but also has the potential to heal our biggest societal wounds.

Implicit in these writers’ stories of their own encounters with transformative justice is a call to action: We are all respon sible for building a restorative community, whatever that may look like. Whether in our families, places of employment, neigh borhoods, communities of faith, or broader society, we are each called to bring about God’s justice on Earth.

I hope these articles and essays inspire you to think differently about justice and punishment. I encourage you, after reading and reflecting on this issue, to dive deeper into restorative justice and how you might be involved.

Emily Sanna

Emily Sanna

FALL 2022 • NO. 135 2

Blessed are the Peacemakers

BY MAGGIE LAUDER

I was feeling very nervous to begin this restorative process. Many of the seventh graders were still talking about the fight in gym class: There was video. Was one of the girls dragged by her hair as the kids were saying? The administration suspended one of the students who had other infractions on her record (notice the carceral language we place on students) and sent the other three to district “alternatives to suspensions.”

The four girls involved in the fight arrived in my room to participate in a restorative process after already being punished for what had happened. They sat in chairs arranged in a circle in uncomfortable silence, arms crossed, their eyes on me. It wasn’t the ideal implementation of restorative justice as an alterna tive to punishment, but at least it was something. They had all agreed to participate in hopes of preventing further conflict. All four felt bogged down and pressured for a “round two” fight. One girl’s mother was so concerned about another fight that she was reluctant to send her daughter to school. In addition, the girls were strangers to one another: Two were in the school’s magnet program and the other two were in the general educa tion program. The two student subsets minimally interacted.

Despite my anxiety, the resulting circle was one of my most successful and one that often comes to mind when I think about the power of reconciliation and restorative justice. The four girls spent close to two hours agreeing on the parameters for discussion and discussing what had happened, how they had been impacted, what they were worried about, and what they needed to do going forward to make it right. They discovered the fight had really started over nothing; because they didn’t know one another, their suspicions, assumptions, a little bit of seventh-grade rumor, and the perceived need to “save face” escalated the situation.

One of the girls, a quiet magnet student with no previous dis cipline record, acknowledged the physical harm she had done by pulling one of the other students’ hair. She apologized. All expressed a fear they would be pressured into fighting again and a desire not to be under the microscope. The lone student who was suspended expressed her frustration, and the others met her with empathy. The final shared sentiment was something along the lines of, “Hey, I didn’t know you before and thought you were [fill in the judgmental assumption], but now I know you are pretty cool.” The students didn’t fight again. They walked out of my room with specific agreements they created together,

they felt safe on campus, and they were assured the conflict was over. This is a triumph of peace when you are in seventh grade. Blessed are the peacemakers.

I was first exposed to restorative justice when studying the 1994 Rwandan genocide. I read about community meetings in which perpetrators of the genocide were held to account by their communities. I was taken aback when I considered what healing looks like after the most egregious acts of violence. Surely, if God is present at all, God is present in projects such as this.

In the United States, many cite Howard Zehr’s powerful 1990 book, Changing Lenses: A New Focus for Crime and Justice (Herald Press), as essential to popularizing and raising consciousness about restorative justice. The book articulates an alternative vision of justice that addresses a weakness in our criminal process: As it is now, criminal justice doesn’t meaningfully include the victim. Folks often walk away from our Western legal system unsatisfied that the harm they experienced is healed or that they feel any safer.1

Another practitioner of restorative justice, Ron Claassen, points to several independent movements in the United States that arose simultaneously and which the growing restorative justice movement drew from.

1. The victims’ movement in the 1970s and ’80s, which is best known by groups such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) and the National Organization for Victims Assistance (NOVA).

2. Indigenous communities around the world who “have been preserving and reclaiming some of their most constructive old ways of resolving disputes and maintaining order.” 2

3. The Alternative Dispute Resolution movement dating back to the 1970s and ’80s focuses on providing ways to resolve civil disputes that might otherwise end up in court.

4. The Community Oriented Policing movement, which “brought attention to the need for police to partner with the community and assist them in solving their problems.” 3

1 Howard Zehr, The Little Book of Restorative Justice (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2002). See also Zehr Institute for Restorative Justice, zehr-institute.org.

2 Ron Claassen, “Restorative Justice - Fundamental Principles” Presented May 1995 at NCPCR; revised May 1996 at UN Alliance of NGOs Working Party on Restorative Justice (2004): 4-6.

3 Claassen, “Restorative Justice,” 5.

3 A MATTER OF SPIRIT

5. The Victim Offender Reconciliation Program movement started in the mid-1970s to assist victims and offenders in a process in which offenders accept responsibility for wrongdoing and do something to repair harm.

The cluster of practices and evolving philosophy called restorative justice draws elements from all of these movements. Today, there are restorative justice practitioners and practices in the criminal justice system, the school system, workplaces, and within community centers. In any place where there is conflict, there is an opportunity to share power, to explore what harm has been done, to be accountable for the harm one caused, and to give space for those affected to share their story and have their needs met.

Today, restorative justice practices are expanding beyond the criminal justice system. There is a growing understanding, for example, that our school punishment system mirrors our criminal justice system and that educational code is a form of law. The 1980s and 1990s saw a focus on “zero-tolerance” policies in our schools that mirrored our sentencing. Students who are suspended and expelled are more likely to drop out and have higher instances of contact with police and eventual incarceration. Many young people experience their first contact with police at school. Additionally, data demonstrate these school punishments disproportionately affect Black students and students with disabilities.

In 2007, early adopters of restorative justice in education, such as Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth (RJOY), found success using restorative processes instead of suspensions. They used restorative processes to build community and belonging and to support students reentering school after incarceration. They included families and worked towards a wider vision of community healing.

In 2014, the Obama administration issued guidance on school discipline that pointed to racial bias in school discipline and outlined data demonstrating the school-to-prison pipeline.4 This report prompted states such as California to make adjustments to their educational codes, banning suspension for certain offenses (for example suspension for willful defiance in kindergarten) and incentivizing school districts to use alternatives to suspensions. Restorative justice was named as one possible alternative.

It was into this sea of overlap between schools and courts that I began my work in 2016 as a restorative justice trainer and practitioner in southern California. It is because of this grow ing understanding of restorative practices that I was able to help those seventh graders process a harmful conflict and move beyond punishment to reconciliation.

4 US Department of Education Office of Civil Rights, “Data Snapshot: School Discipline Issue Brief No 1.” (March 2014). https://www. ojp. gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/civil-rights-data-collectiondatasnapshot-school-discipline-issue.

As people of faith, our understanding of God commits us to work for peace. There is a clear vision of shalom in the prophets of the Hebrew scriptures that carries through to our understanding of God as love, or agape. This love-agape is centered on the other and does not expect reciprocation.

For example, in Matthew 5, Jesus says, “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, ‘Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you’” (43–44).

The church has always had a presence in prisons, living out the corporal works of mercy and bringing the dignity of all people into this work.5 Restorative justice goes beyond prisons and fosters a way of being in relationships that seeks connection, belonging, and love. Humans are hard-wired for relationship, and we experience the “necessity of the other” 6 in God’s love manifested in our love for our neighbor and their love for us.

In my limited experience, focusing on relationships is the most concrete way to teach people how to share power, how to be accountable for the harm we do to one another, and how to follow the lead of those who have been harmed in finding ways to heal. Restorative processes do not just tell young people about our values; they give us actionable ways to live them out.

I am deeply grateful for all the encounters I have had with youth when they are “in trouble,” as they have shown me the face of Christ even when they were not ready to take responsibility and participate. The youth I have worked with in my career have always done more for me than I have for them. There are pro grams, projects, and iterations of restorative justice throughout our communal systems; however, they are merely glimmers in a landscape which is primarily punitive and often biased. The deepest transformation only comes when each of us embraces the peace-making that characterizes the reign of God. Blessed are the peacemakers.

Maggie Lauder taught theology at Servite High School for 10 years and has worked with Orange County Human Relations to help design and launch a restorative justice in schools program. In 2021 she began work at Brophy College Preparatory teaching and working in social justice formation.

5

United States Catholic Conference of Bishops, Responsibility, Rehabilitation and Restoration: A Catholic Perspective on Crime and Criminal Justice. (Washington DC: United States Catholic Conference, 2000).

6 One of the four formation themes at Servite High School in Anaheim, California. servitehs.org/formation

branch images © mokoland, Freepik

FALL 2022 • NO. 135 4

“Restorative justice goes beyond prisons to a way of being when we are at home and to in all relationships where we seek connection, belonging, and love.”

The Promise of Restorative Justice

BY CRYSTAL CATALAN

During this time, she worked on repairing the broken relation ships in her life, practiced her own truth-telling, and gave voice to her trauma that had otherwise been left unsaid. She also ac knowledged the lasting trauma she caused others and commit ted to becoming better.

An element of hope underlay this entire process. And this is what keeps me going as a chaplain and restorative justice practi tioner. It is hope that gets me in the car after a long day of work visiting the local correctional facility. It is hope that gives me the energy I need to put together scripture reflections and Bible studies: hope that the Holy Spirit may transform the hearts of all whom I will encounter in that weekly hour and a half visit.

Because of this hope, I believe that it is possible for a nation or society to truly reconcile and make reparations for harm done in the past, especially for things such as Indigenous boarding schools or crimes against the environment. Is it possible? Yes. Will it take time? Yes. Will it be easy? No.

As a restorative justice practitioner, I believe in the importance of dialogue, openness, and vulnerability. These are required in order to name our truths, to be truth-tellers, and to create brave spaces so that nothing is left unsaid. When engaging in restorative justice, all the people who are impacted or affected in any way are part of the conversation. The intention and commitment to move forward and heal is there, even in the midst of the tears, anger, challenge, and potential opposition. And this happens not only on an individual level, but potentially on the societal level. Restorative justice can help heal even giant societal relational breaks.

I recently facilitated a restorative circle of educators where one person reflected, “I had no idea that my coworker experienced that form of racism when she was a young girl. It makes me more aware of things to look out for with my elementary students in class.” To me, this powerful statement serves as an example of an individual’s desire to end the trauma created by the insidious nature of racism.

If we truly desire to solve society’s biggest problems through reconciliation and the implementation of restorative justice, we need to act toward reconciliation and move towards rebuilding broken relationships. We must acknowledge that we cannot undo harms that have taken place, many caused by our ancestors, but we can address them and stare at them straight on, faithfully seeking to make right what has been wronged in the past. And we must listen. Listen to the harm that has taken place without dismissing the voices of individuals and communities. Finally, we must seek to understand and to be better.

I accompanied a young woman through the Rite of Christian Initiation while she was held in custody at the local correctional facility. She wanted to receive the sacraments before she was transferred to prison, and we were both determined to help her move forward in faith while she prepared to put in the time for the harm she had caused and the offense she had committed.

As a society, we are faced with the choice of how we want to move forward. Do we want to move forward without remember ing the past? That is impossible. Part of restorative justice is re pairing the harms that have taken place, and on a societal level, we as individuals are responsible for ensuring that the harmful parts of history do not repeat, thereby affecting generations to come.

I am often struck by Howard Zehr’s first statement in “10 ways to live restoratively,” a blog post on his website: “Take re lationships seriously, envisioning yourself in an interconnected web of people, institutions and the environment.” Restorative justice, as opposed to criminal justice, focuses on relationships. When we truly realize and recognize that each one of us is made in the image and likeness of God and that we each have inherent dignity and are worthy of respect, then things will be different. If we choose to live restoratively and see ourselves in this “inter connected web,” then things will be different.

Once we see our relationships as intertwined in this way, we realize, “If one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honored, all rejoice together with it” (1 Cor. 12:26, NRSV). But we cannot get there if we are stuck in a tangled web of blame, shame, and punishment. Instead, reconciliation is only possible if we shift our focus to repair, rebuilding, and restoring relationships that have been broken—even across de cades and generations.

Relationships are severed. Our society is divided. And yet reconciliation is possible. Restorative justice does not require forgiveness, but it does ask that we engage in the process and start taking steps towards healing. Just maybe, forgiveness will be in the faint distance and may come as part of the healing pro cess. Restorative justice believes that everyone is redeemable. It is possible once we as a society come back to the truth that we belong to one another and are interconnected in this web of life.

Crystal Catalan is the director of diversity, equity, and inclusion at Presentation High School in San Jose, California and a restorative justice practitioner.

“We can never move forward without remembering the past; we do not progress without an honest and unclouded memory.”

© Fly, Unsplash 5 A MATTER OF SPIRIT

—POPE FRANCIS, FRATELLI TUTTI

Something Worth Striving For

BY JANINE GESKE

Iam a former Milwaukee County Circuit Court judge and Wisconsin Supreme Court justice and an advocate for restorative justice. People regularly ask me whether restorative justice approaches could serve as an alternative to the criminal justice system. My usual answer is that the criminal justice system should not be entirely replaced. Criminal court proceedings serve many purposes, including the preservation of constitutional rights and the determination of guilt or innocence. But there is no question that we should be utilizing many more restorative justice approaches before, during, and after criminal charges.

However, restorative justice will generally not be appropriate when there are constitutional concerns that should be litigated or when the accused denies committing the crime. For restorative justice to be successful, the offender must admit to being involved in the alleged conduct and be willing to participate.

Some criminal defense attorneys are critical of incorporating restorative justice into the criminal justice system, because they worry that their clients will have to admit their guilt and risk neg atively impacting their cases. Generally, a restorative justice pro cess requires admission of fault and a plan that the offender must agree to follow. If the offender does not comply with the plan, the offender’s case will be sent back to court with the original charges.

Despite these misgivings, there are several examples of suc cessful restorative justice programs. For example, Dane County, Wisconsin, implemented Restorative Justice Court (RJC) modeled after the “circle justice” processes utilized by Native American tribes. In the RJC, residents, victims, and offenders work together to find a resolution that repairs the harm done to the community.1 The Dane County District Attorney’s Office or a law enforcement agency2 refers eligible offenders—those between the ages of 17 and 25 who have committed a misde meanor or a municipal ordinance violation—to the RJC. Once participating in the RJC, offenders must take accountability for their actions and be willing to participate in the restorative jus tice process. Both victims and offenders meet separately with RJC staff to discuss the incident. Trained volunteers from the community, called peacemakers, assist in the circle process by creating an agreement outlining how offenders will repair the harm. If an offender complies with the terms of this repair harm agreement, they are not charged: Ninety-two percent of offend ers successfully complete their repair harm agreement.3

Another successful example is the restorative justice court in Los Angeles. The Neighborhood Justice Program (NJP) may be used as an alternative to the criminal justice system if the offender committed a low-level misdemeanor.4 Police departments forward the police report to the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office, which considers the offender’s past criminal record and the facts of the case to determine whether it will refer the case to the NJP or file the case in court. The NJP process includes a facilitator, the offender, and two community members. The offender creates a list of harms they have caused and often writes apologies to people they may have harmed. To avoid criminal prosecution, an offender is given a list of tasks to perform within two months; if

1

For restorative justice to truly be an alternative to the crimi nal justice system, there must be a process to address the harm caused by the crime before an individual is charged. There are also many ways to integrate a restorative process (victim–offend er mediation, community conferencing, family group conferenc ing, etc.) at various points in a criminal case. The process can lead to either a dismissal of the case or reduced incarceration.

“What is the ‘Circle’ Process and the Guiding Principles of the CRC?” The Dane County Department of Human Services. Accessed November 10, 2022, https://www.dcdhs.com/Children-Youth-andFamily/Community-Restorative-Court.

2 “Frequently Asked Questions,” The Dane County Department of Human Services. Accessed November 10, 2022, https://www.dcdhs. com/faq/home

3 “What is the ‘Circle’ Process and the Guiding Principles of the CRC?”

4 “What Is the Pre-Filing Neighborhood Justice Program, or NJP?” Greg Hill & Associates. Accessed November 10, 2022, https://www. greghillassociates.com/what-is-the-pre-filing-neighborhood-justiceprogram-or-njp.html.

CCO Public Domain FALL 2022 • NO. 135 6

“For restorative justice to be successful, the offender must admit to being involved in the alleged conduct and be willing to participate.”

they comply, they avoid criminal prosecution but if they do not comply, the case returns to court. The NJP received over 5,000 referrals, and the recidivism rate for those who successfully complied with the program is 5 percent.

Likewise, Milwaukee offers the Community Conferencing Program (CCP) as an alternative to the criminal justice system.5 An offender must be referred by a prosecutor, defense attorney, victim–witness advocate, judge, law enforcement officer, probation officer, or a victim. The program does not accept offenders who have committed violent crimes or cases involving drugs or guns. It determines eligibility based on factors such as whether the offender has taken responsibility for the act and their degree of remorse, prior record, type of crime, and general attitude toward the victim. Once a case is accepted into the CCP, the victim, offender, and affected community members come together with an impartial facilitator to discuss the crime and its impacts. Then community members come up with ideas on how the offender can repair the harm they have caused. If the offender successfully complies with the guidelines the community members provided, the offender is entitled to receive reduced charges or sentences or have the charges against them dismissed.6 In 2004, the Wisconsin Legislature surveyed CCP offenders and found that 4.3 percent of offenders who participated in the program reoffended while 13.5 percent of nonparticipants reoffended. Moreover, 62.2 percent of offenders who signed conditions of agreement complied with their agreements.7 In addition, between 2000 and 2008, offenders who did not participate in CCP had a recidivism rate of 28 percent, while those who did participate in CCP had a recidivism rate of 9 percent.8

There are similar programs around the country. Minnesota’s Circle of Support and Accountability restorative justice program lowered re-arrest rates by 62 percent and lowered the return to

prison rate by 84 percent.9 In Baltimore, participants of the Community Conferencing program are 60 percent less likely to reoffend.10 Moreover, out of the 98 percent of participants who reached an agreement in this program, 97 percent complied with the terms.11 In addition, Texas and Ohio were the first states to develop a statewide program for victim–offender dialogue in serious and violent crimes. Both victims and offenders gave the program overwhelmingly positive evaluations: Most report the experience is life changing.12

All of these examples show that while restorative justice cannot completely eliminate the criminal justice system, certain cases present unique opportunities to engage in restorative justice as an alternative to the criminal justice system or as part of the criminal process. Traditional criminal justice systems are offender-focused: the arrest, charging, investigation, prosecution, conviction, sentencing, and incarceration all center around offenders. This gives victims few meaningful opportunities to have their voices heard. Restorative justice, on the other hand, is victim-focused and holds offenders accountable for the direct harm they cause. Repair of this harm is at the center.

A restorative justice model is worth striving for. It develops relationships and strengthens community ties and brings people together who would not otherwise have met. In addition, restorative justice creates a safe place for everyone—victims and offenders—while the traditional criminal justice system builds boundaries that keep people separated. Restorative justice positively impacts and transforms not only the victim and the offender but the community as a whole and has been linked to reducing recidivism rates and increasing restitution to survivors.

Justice Janine P. Geske is the director of the Andrew Center for Restorative Justice and a distinguished professor of law at Marquette University Law School in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

5 John T. Chisholm, Community Conferencing Program (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee County District Attorney's Office).

6 An Evaluation: Restorative Justice Programs Milwaukee and Outagamie Counties (Milwaukee, WI: Wisconsin Legislative Audit Bureau, June 2004).

7 Ibid.

8 Mark Umbreit, Notable Restorative Justice Programs (Minnesota: University of Minnesota School of Social Work, September 21, 2010).

9 “Restorative Justice Research Summaries: Three Meta-Analyses Show Positive Outcomes for Restorative Justice Conference Programming,” University of Minnesota Duluth, accessed October 7, 2022, https://rjp.d.umn.edu/resources/rj-research-summaries 10 Ibid.

Ibid. 12 M. S. Umbreit et. al. Executive Summary: Victim Offender Dialogue

Crimes of Severe Violence: A Multi Site Study of Programs in Texas and Ohio. (St. Paul, MN: Center for Restorative Justice & Peacemaking, 2002).

Recidivism Rate Participants Who Reoffended Non-Participants Who Reoffended Compliance with Agreement Los Angeles Restorative Justice Court 5% Wisconsin CCP 2000-08 9% 28% 62.2% in 2004 Baltimore Community Conferencing 60% less likely to reoffend 97% of 98% complied Minnesota's Circle of Support & Accountability Lowered arrests by 62% and return to prison rates by 84% 7 A MATTER OF SPIRIT

11

in

WE LIFT AS WE CLIMB: RESTORATIVE JUSTICE WITHIN THE BLACK PRISONERS’ CAUCUS

When Kimonti Carter was 18 years old, he killed another young man in a gang-related drive-by shooting. Because of Washington state’s “tough on crime laws,” he was tried as an adult and sentenced to life without parole.

Despite the fact that society turned its back on him, Carter did not give up. He got involved in the Black Prisoners’ Caucus, an organization founded by Washington prisoners to foster Black identity and strengthen Black communities. His work with BPC eventually led him to found T.E.A.C.H. (Taking Education and Creating History), a higher-education program that allows in carcerated people to take for-credit classes and work toward an associate’s degree.

In July, Carter was resentenced to 23 years in prison, includ ing time served, and released. His resentencing was a result of a new Washington State law that prevents young people who commit crimes from being sentenced to long prison times while their brains are still developing.

A Matter of Spirit talked to Carter and Dr. Gilda Sheppard, Carter’s sociology professor and director of Since I Been Down, a documentary featuring Carter that explores the effect of strict sentencing laws on a generation of Black and brown youth, about how the BPC and T.E.A.C.H. are successful examples of how restorative justice can work with the prison system.

WHAT DO YOU THINK IS THE MOST IMPORTANT PART OF RESTORATIVE JUSTICE?

Kimonti Carter: I want to highlight how important community relationships are, especially for young Black and brown boys and girls growing up in communities that don’t receive enough resources to provide them with a safe place to live.

I had examples from men in similar situations. They were able to bring me into the Black Prisoners’ Caucus (BPC) circle. They saw that I had a brain on top of my shoulders. They took the time to provide the space for me to make mistakes and help me through them. There was no judgment. They loved me re gardless. They let me know that my past didn’t define me.

Our community is lacking, because we guys are [in prison]. We need to show a better presence for our community to be strong. I have a responsibility to take care of my family and my community. Growing up in the street, that’s how it’s always shaped—it’s your hood, your community, so you protect it. But in prison, we realize that there are also larger forces at play.

Society is designed to entrap people who live outside the

norms. Black and brown folks often get caught outside of those lines, and that’s why they end up in prison. This helped me to see even more why I need to support my community and my brothers and sisters regardless of their mistakes. Everyone makes them: We can’t get so judgmental to where it prevents us from being able to build relationships. We have to be able to say, “I forgive you” and really mean it to the people who did us harm.

HOW DOES TRANSFORMATIVE JUSTICE DEPEND ON RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHER PEOPLE?

Gilda Sheppard: What I love about Kimonti is that he doesn’t start his story with what he does or who he is. He starts with where he grew up. He begins his story in community. And he uses it not as an excuse, but as a responsibility.

When I taught classes in prisons, I saw that the students were doing this critical reflection where they looked at their sto ries and saw how social forces and the historical context greatly informed their actions. This was when I first really experienced restorative justice; they were healing themselves in order to create. And they did it in communion. As Kimonti said, you cannot heal without being in community.

What I saw in my classroom wasn’t just an understanding that hurt people hurt people. It was broader than that. It was a theory of change: a practice of people not only understand ing their context, but realizing that to understand their context, they need to realize that there are some non-negotiable path ways that exist. For Kimonti Carter, he admits his crime, names the young man he killed, and talks about who that man could have become. He apologized to him and his family, and then he names his actions as part of a systemic thing—we don’t think about how we treat children.

This goes beyond restorative justice to transformative jus tice. And there is no restorative justice without transformative justice: Otherwise, you keep getting ambushed. And then you heal and get ambushed again. Over and over again.

I don’t have a magic formula for how to do this in my back pocket, but I know that I have to do things that make me uncom fortable. I have to stay close to the problem and maintain hope.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF HEALING IN TRANSFORMATIVE JUSTICE?

Sheppard: The struggle for justice comes with some punching on your spirit. So healing is a big part of it—not only for people who we’ve harmed, but for ourselves as well.

Editor’s conversation with Dr. Gilda Sheppard and Kimonti Carter, October 2022

Editor’s conversation with Dr. Gilda Sheppard and Kimonti Carter, October 2022

FALL 2022 • NO. 135 8

Bring the Fire © Jeanne Ambre, SSCM, 1996

Carter: There’s a difference between people who are passionate about the work, do it for a while, get burnt out, and then go off to do something else and those of us who have no choice but to stay in the fight. Leaving is the luxury of white supremacy. For those of us in the BPC, this isn’t something we can just run away from; it affects our life. It affects our children’s lives. We can’t give up: Our life depends on it.

Sheppard: The first time I went to a prison, I was so glad to go teach a class. I was so excited to meet all these brilliant brothers at the BPC. But I got three minutes away from my condomini um, and I had to pull over, and I cried one of those ugly cries. To this day, I don’t know what that was, but it had to do with intergenerational trauma.

My cousins used to come from Alabama to live with us in Detroit and work in a factory. They were saving money so their kids could go to college or get a better job. Three generations after that and you know where those kids are? My cousins are in prison. Mass incarceration, white supremacy, and racism are all part of this intergenerational trauma. And healing needs to be part of this.

Carter: At the Black Prisoners Caucus we do what are called healing circles. At every meeting we sit in a circle—this physically and emotionally creates that metaphor of being and staying con nected. That we are stronger together than as one. A circle bends all types of ways, but as long as we keep it tight regardless of how many people sit in the circle it can do some powerful things.

These circles give us the opportunity to really speak to people and air out some of our own issues on a personal and societal level. It ends up creating a bunch of stronger relationships: We live together, we’re going to have to deal with one another, and we can’t look at nobody outside the circle for help.

Through this circle we are able to heal through a lot of our mistakes and our traumas, because we all come from one another’s community.

WHAT DOES A WORLD THAT'S GUIDED BY TRANSFORMATIVE JUSTICE LOOK LIKE?

Sheppard: It looks like a place where we don’t need prisons anymore. It looks like a place where health care and public health come together. It looks at a world where we don’t see people living in tents—unless they want to.

That sounds like utopia. But it’s not a place we ever reach and say, “OK, we’re here. We’re done.” Those who believe in freedom cannot rest until it comes. And it just keeps coming.

Carter: I hear the word utopia and I think about those sci-fi movies where everything is peaceful. But in the future, outside of those blissful communities, there are also places where people are still living outside of the norms. I think that transformative justice has to imagine a world where all of us live inside those walls, not just some of us. We need to be willing to acknowledge one another’s humanity and share a common idea where our society should go. Where no one has opportunities denied to them based on how they live or look.

Shepherd: It’s like Kimonti said: We will see the humanity in one another. If you do so it’s very difficult to knock him on the head. To do that, you have to objectify him.

DO YOU THINK WE ARE MOVING TOWARD THIS WORLD?

Carter: My answer is definitely yes. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t going to take some work. In 2021 the Washington Supreme Court found that it was unconstitutional to sentence people under the age of 21 to life without parole. At one point we lived in a society that was willing to exterminate kids, and the Supreme Court changed their decision based on new infor mation. They—along with other states—are beginning to say that they believe compassion should be considered for people who commit crimes between the ages of 17 and 25.

The spread of the BPC shows how this has to happen in an authentic way. It wasn’t spread in a top-down way by prison authorities, but instead by men traveling from prison to prison and building relationships. Sometimes we can get tricked into thinking there’s a magic potion. Like we can just cookie-cut a whole bunch of concepts and values, beliefs and ideals, and just transplant them to a completely different part of the world and expect to have the same results. People don’t work that way.

Spreading transformative justice requires a passion burning in your soul and people who refuse to let it die out. The BPC had nothing to do except to take hold and develop in other places. It was a lifestyle for a lot of people, particularly brothers who sat amongst the circle with us. That passion ain’t ever gonna go away.

Collaborative Organizing for Racial Equity (CORE) Restorative Justice

Washington State has one of the most regressive carceral systems in the United States and, over the last three years, restorative justice has been an area of focus for IPJC. This work has been organized through the Seattle Collaborative for Racial Equity, a collaborative project of the Jesuit works in Seattle. Last year we screened Since I Been Down to share the work of the Black Prisoners’ Caucus and the story of Kimonti Carter with over 800 individuals.

Connected to this effort, folks advocated for several Wash ington State bills aimed at reforming the carceral system; their efforts resulted in the passage of House Bill 1412. This bill will expand judicial discretion on legal financial obligations, allowing judges to wave restitution payments they deem a defendant does not have a reasonable capacity to make payments due to their financial situation. This is a step forward in decriminalizing poverty.

IPJC’s work to educate the community, deepen partner relationships, and participate in the growing restorative justice multi-faith coalition deepens this year. During the 2023 Washington State legislative session, we will be advocating on a slate of bills. Visit our website and join our email list to stay up-to-date!

9 A MATTER OF SPIRIT

You Have to See It to Believe It The Promise of Restorative Justice in Schools

BY PERRY PETRICH

Think of all the ways that schools get students to do what they’re told. The classic is detention. Threaten the students with that—maybe escalate to threats of suspension or expulsion—and you can drum up some fear. Appeal to that fear, and they’ll fall in line.

There’s also affirmation. Shovel some praise on an exempla ry student or two, and you’ll encourage them to keep it up and maybe even get others to imitate them. You pick who you praise and, if you play your cards right, everyone starts to behave like they do.

If you’re John Dewey or Thomas Aquinas (or somewhere in between), you might have thought about building habits. Set some clear and detailed expectations and hold everybody to them, and students will begin to reflexively act a certain way. The students will comply without thinking about it.

If, however, you thought first of mutual respect, then I wish I had more teachers like you. Maybe all it takes is teaching students to listen to and care for one another. As they realize more and more how their actions affect other people and care more and more about how others might be doing, they’ll take responsibility for treating one another right out of sheer respect.

If you talk too much about school discipline based on mutual respect, you’ll start to hear, “I’ll believe it when I see it.”

But consider this possibility:

The boys’ bathroom at a small high school was getting vandalized. Daily.

What will stop this bathroom vandalism? The school prac tices restorative justice. There are no offenses that end auto matically with expulsion or even suspension. No zero tolerance. Everyone wondered how this is going to play out, maybe with a bit of cynicism. These are children, after all.

The principal sent a note to the whole staff on a Thursday night. The boys and male faculty were pulled from their classes on Friday morning and gathered in the wellness center at 8 a.m. for a restorative circle. Teachers had to throw out their lesson plans, but their reaction was one more of curiosity than frustra tion. What on Earth would happen?

The first thing the students and teachers noticed that morn ing was all of the chairs. They were in an improbably large circle, and they all matched. Somebody must have gone up and

down the stairs, searching out 40 matching chairs from all the classrooms.

As students trickled in, the principal asked them each to take a seat and to put their stuff under their chair. As they did, they looked through bleary morning eyes at a vase of flowers placed on a cloth at the middle of the circle.

The principal picked up a stone with the word respect painted on it. He spoke about the reason everyone had gathered (urine on the bathroom floor) and said what the group was going to do (share how it affected each of them) in order to solve this problem (without suspension or expulsion).

And then they talked and listened. Each boy took a turn holding the respect stone and, in their earnest 14-year-old-boy way, shared how scared or angry or lonely the vandalism made them feel. One staff member said that the smell of the urine made him think of the homeless shelters that he was in and out of as a child. One of his favorite parts of attending school, he continued, was escaping that smell. To walk down the hall and smell urine destroys the sense of safety and escape he treasures.

On it goes until one student asked to speak again. The kid started talking about how unwelcome he feels at the school. He was being singled out by teachers and felt like he didn’t have any friends. He hated it there and took out his anger by, well, van dalizing the boy’s bathroom. He didn’t realize how that made people feel. He apologized for hurting people in ways that he didn’t know he could. He promised he wouldn’t do it anymore.

Nobody saw that coming. What’s crazier is that there was no punishment. There was a moment of silence together, and then it was off to lunch. Problem solved. No more bathroom vandalism.

All it took was half the school missing half an instructional day. Hour-long classroom circles three times a week. A few daylong training sessions for all the adults on campus.

And then all of the time persuading teachers to abandon all the school discipline that they’ve known from their training and from their own experience as students. Keeping up hope that the school won’t fall apart even when the smell of urine lingered in the hallway for days. The conflict and mistrust that occur whenever people have to face anything new.

Not to mention lugging all those matching chairs back and forth. I think restorative justice works in schools. I also think

FALL 2022 • NO. 135 10

that people underestimate what it takes to put that into practice.

Everybody’s got to buy in. Just one person punishing children into compliance keeps the students from taking circles seriously. And the time commitment—losing days of instruction—can be a hard sell to a faculty struggling to help students learn.

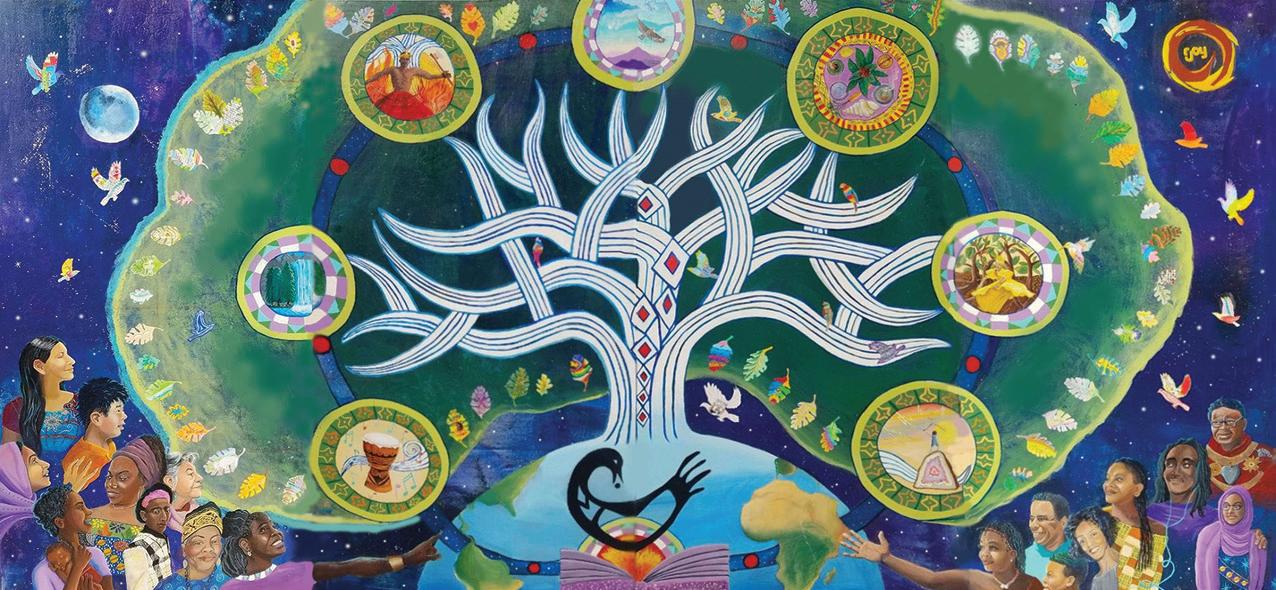

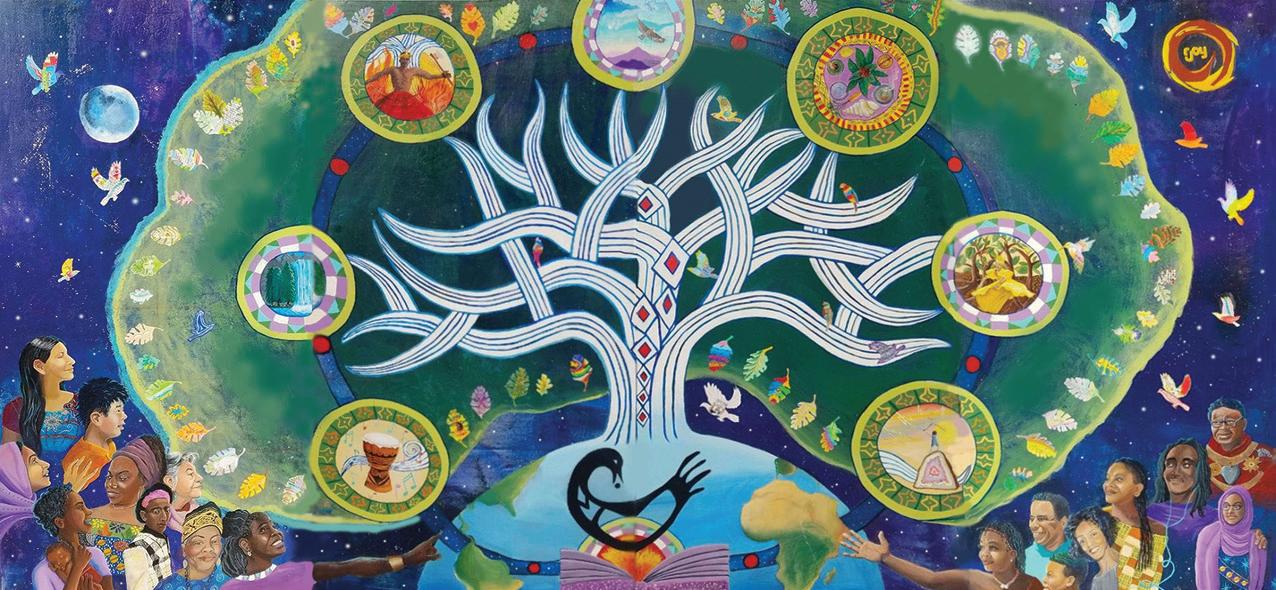

The Singing Tree Project was founded by Laurie Marshall and is an invitation for people to build connections through art. This particular Singing Tree mural was designed with students from AIMS High School in Oakland, California. You can see more about their process at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=7edHiSFSgkU. Photos below from the youtube video.

But what’s the alternative? Punish the students, and they lose class time when they’re sent to the office or suspended or ex pelled. Affirm students into compliance, and they can lose sight of the intrinsic rewards of being kind: They’re “good” for the reward, not because they care about others. And if you trust that structures and habits will keep the students in line, they might be unprepared to respond to novel moral questions on their own.

Because what makes restorative justice worth the effort—and there’s quite a bit of effort—is not just helping students treat one another well so they can learn better. It’s about giving students the power to form and maintain healthy relationships for the rest of their lives—their friends, their coworkers, their families. They practice forgiveness, mercy, and reconciliation. You train them to be healers. So, you’re not just keeping your school safe; you’re spreading seeds of peace.

Father Perry Petrich is a Jesuit priest who teaches at Seattle Nativity School. He received his training in restorative practices in schools from Catholic Charities East Bay.

“I think restorative justice works in schools. I also think that people underestimate what it takes to put that into practice.”

11 A MATTER OF SPIRIT

Transformation A Vision of Mutual

BY CHRIS HOKE

BY CHRIS HOKE

Chris Hoke is the director of Underground Ministries, a nonprofit in Washington State whose mission is to open new relationships of trust between the incarcerated and the communities to which they return for our mutual transformation and resurrection. AMOS spoke with him about his vision for a world governed by restorative justice.

What led you to prison reentry organizing?

When I graduated from University of California Berkeley 17 years ago, I volunteered doing Bible studies in a jail. I thought I would learn radical theology and leave. I didn’t expect to like the young gang members so much, and for them to like me back. They invited me to one-on-one visits as their pastor. I didn’t want to be their pastor, but they insisted. So I became a gang pastor. I visited their apartments, saw their children, and heard their stories of unspeakable trauma.

I saw how many of the guys I grew to care for were not released into the community, but instead sentenced to long sentences and sent to maximum security prisons around the state. I stayed in touch with them through letters and collect calls, and these relationships began to really affect me. I found a quality of communion that I didn’t have with my high school or college friends: a depth of sharing, self-indictment, selfexploration, and laughter that pulled me in.

When you created Underground Ministries, you began using resurrection as a vision for reentry. What do you mean by that?

Sociologist Orlando Patterson talks about American incarceration as social death, so to welcome these folks out of the tombs of incarceration is a type of resurrection. I began Underground Ministries based on the direct accompaniment of gang-affected individuals in their reentry—to help this resurrection. Then I heard that there’s the same number of churches in Washington State as there are folks who are incarcerated. This haunted me: There are churches in every town, every community, gathered in the name of forgiveness,

grace, community, and the resurrection of the dead. What if every church, large or small, rallied with embrace and reentry support around one person coming out of the prison tombs into the local community? This led to the One Parish, One Prisoner program.

Instead of funneling reentering citizens through government programs or even nonprofits, One Parish, One Prisoner tries to help people build relationships of repair and integration within their own communities. To stop throwing away the most-harmed communities. We mobilize spiritually concerned communities to practice a response to crime that acknowledges the person coming home has committed harm while also helping restore that individual and recognizing that they themselves are walking wounds and have many layers of harm in their own lives. We’re building cultures of repair rather than cultures of punishment. The relationships formed through this program and the restorative work we’ve done illustrate on a small level how the world could look if driven by restorative justice.

Your mission statement talks about how opening such new reentry relationships in the community leads to “mutual transformation.” What does that look like?

Underground Ministries partnered with was a progressive church who immediately volunteered to help. They wanted to interrupt mass incarceration. We introduced them to the person with whom they would be partnering—at this point he was still incarcerated, and the first step in the process is to start exchanging letters and building a reentry plan. We tell the team not to Google the person—would you like if someone could Google the worst things you’ve ever done?

One of the women at this parish reached out to me and said, “Chris, I did what you told us not to do. I Googled this man’s crimes. And I have some problems with what I saw.” This man had some pretty heavy domestic violence charges, and it turns out this woman was a survivor of domestic violence herself.

I offered to meet with her, and we talked for an hour over coffee. She told me all about growing up with violence in her house and how the man who abused her was a leader in the

© Coolvector,

SPRING 2022 • NO. 134 12

Freepik

church. She had a similar energy to the guys I talk with in prison—like this story was fresh and coming out hot and wasn’t something she had really talked about before. I asked her how it felt to talk about this, and she told me that it felt good, like it was probably something she needed to do more.

The only reason she could talk about the domestic violence she experienced was because someone who can’t hide their own history with domestic violence was approaching the community to be in relationship with members of the church. And rather than saying, “You evoke our fears and we need to keep you away”—which is what mass incarceration is—she and the rest of the congregation welcomed him home with a new sense of their common wounds and how they might help each other heal.

Even before this guy came home, the church began to talk about domestic violence. They didn’t avoid talking about his charges and offer some sort of fake forgiveness. They did a whole workshop. Teachers came in to talk about how to make churches safer places and how to notice the signs of domestic

This story is an example of how the justice system fails vic tims’ families. The guy in prison has been able to do a lot of growth and healing—he is a mentor and has founded restor ative justice groups. But locking him up for 30 years has not brought his victims an ounce of healing. Instead, their pain has continued through multiple generations. The woman who was murdered had two little boys. Once she died, her husband had to take on two jobs to take care of his family. The boys basically lost both their parents, because their dad was hardly ever home. Now, as adults, they are estranged. They got into some trouble as they got older. Their grief just keeps ripping forward.

Our justice system is not working. If we really wanted to help this family, we would have paid their rent for five years so that father could stay home and help his boys grieve. Instead we put all this money into throwing someone away.

So what can you do now?

violence. They talked about how to welcome people without fa cilitating repression, silence, and shame.

Father Greg Boyle from Homeboy Industries says something I love: “If we despise our own wounds, we will be tempted to despise the wounded.” That’s the core of restorative justice for me: We need one another to heal. Repression and disposal of others in the community works as well as repression and dis posal internally, in our psyches. We get more fractured, lost, violent. Churches need folks coming out of prison just as much as folks coming out of prison need churches. These returning men and women have hard histories that can help unlock the skeletons in our own closets, where our own hidden wounds, addictions, and secrets need healing as well. And that’s what members of this church realized. This is the future we imagine for our communities.

Has there been a situation that’s forced you to confront how the courts currently operate?

A few years ago, we partnered a church with a guy who ex pected to go into clemency, which is a type of legal mercy that releases people early, and who thought he would have a release date in the near future. Thirty years ago, when this man was in his early 20s, he had taken a woman’s life in a pet store stickup and had stabbed her many times. He was high on crack and traumatized, and this angry young man viciously took the woman’s life. When the victim’s family found out, their outcry was immense. They wrote furious letters opposing his early re lease. And so his lawyer eventually had to withdraw this man’s application.

I can’t do anything to help the victim’s family—I wish I could. I wish I could reach out and just be present to them as a pastor. But Underground Ministries has been able to continue work ing with the man in prison. Multiple parishes have gotten wind of his situation and formed a community around him. There is a growing community of faith that is banding around him and saying, “We aren’t minimizing his crime, but we’re not satisfied with someone just being left in a box for years. This is someone we want in our community.”

Punitive practices are based on communities saying, “We don’t want this person. Throw them in the trash.” But restorative justice instead makes the shift to saying that everyone is wanted. Despite doing bad things, they are beloved members of a community.

How did this experience affect your understanding of restorative justice?

The work of healing is hard, and the gods of punishment and retribution are always popular and renewed. The American my thology of good guys vs. bad guys is deep and will be hard to undo. But rarely are people purely monsters. There are normal ly wounded people whose wounds are hard to look at because they remind us of our own wounds. But a world run by restor ative justice is one where we do not look away.

During the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa after apartheid, they didn’t just let things slide. There was a long process of reckoning and justice. Perpetrators needed to come forward and fully own what they did. But this didn’t happen in a vacuum: They sat face-to-face with the people they had harmed. They were forced to face their brutality and rape in front of their victims.

Something happened when people are face-to-face that re pairs. People who commit these crimes lose sight of the human beings whose lives they are destroying. Listening and repenting and service won’t take back the pain or bring back those who have been killed. But I think it would repair. And that’s the kind of justice I want to invest in.

13 A MATTER OF SPIRIT

“Churches need folks coming out of prison just as much as folks coming out of prison need churches.”

Reflection Process

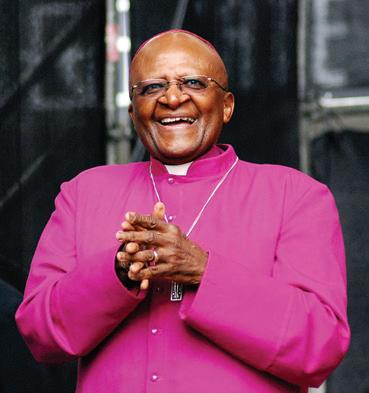

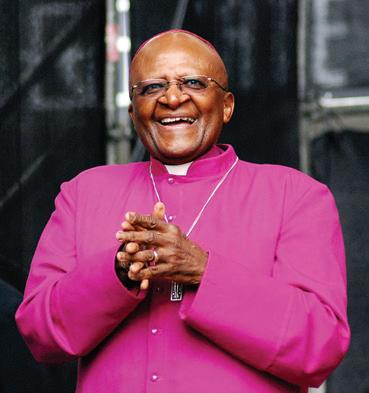

After reading this issue, we invite you to reflect on this excerpt from an interview with Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu on his experience with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa.

[We had a] hearing about an event that had happened in Bisho in Ciskei, where 28 people had been killed by soldiers of the Ciskeian Defense Force (CDF) who opened fire on an African National Congress…. The hall was packed to the rafters, and many who attended had either themselves been injured on that occasion or had lost loved ones. So you could imagine the tension in that hall.

The first person to speak was the former head of the CDF, who riled virtually everybody by talking in a tone that came across as arrogant and cynical. So the tension rose even further.

Then the next group of witnesses consisted of four officers in this defense force. Their spokesperson said, “Yes, we gave the orders for the soldiers to open fire.” You could just feel the audience become really hostile and angry.

But then this soldier turned to the audience and made an extraordinary appeal: “Please forgive us, please. The burden of the Bisho massacre will be on our shoulders for the rest of our lives.” He was white and the three other soldiers were black, and he went on to plead with the audience: “Would you please receive my colleagues back into the community?”

It was unbelievable, unexpected. You could sense the presence of grace right there, because that audience, angry as they had been, almost immediately turned around and broke out in incredible applause. Here were people who were limping, who were shot, some had lost children or other loved ones, and they could applaud.

You couldn’t have choreographed it. It was just spontaneous. The people could quite as easily have booed him.

It was the many victims whom the system had for so long consigned to

anonymity and facelessness—people who had been carrying for 10, 20, 50 years a very heavy burden of anguish—who became the heroes of this process…

We have to keep reminding people that we are the beneficiaries of a lot of praying. I think Christians are strange creatures, because it seems we pray for miracles, but then we’re surprised when the miracles do happen.

The other part is rooted in what we refer to as ubuntu, the African view that a person is a person through other persons. My humanity is caught up in your humanity, and when your humanity is enhanced—whether I like it or not— mine is enhanced as well. Likewise, when you are dehumanized, inexorably I am dehumanized as well.

So there is a deep yearning in African society for communal peace and harmony. It is for us the summum bonum, the greatest good. For in it, we find the sustenance that enables us to be truly human. Anything that erodes this central good is inimical to all, and nothing is more destructive than resentment and anger and revenge.

In a way, therefore, to forgive is the best form of self-interest, because I’m also releasing myself from the bonds

that hold me captive, and it is important that I do all I can to restore relationship. Because without relationship, I am nothing, I will shrivel.

That is also a very biblical under standing: God is community, God is relationship, God is Trinity. God can’t exist in isolation.

Excerpted from “No forgiveness, no future: An interview with Desmond Tutu,” which originally appeared in the August 2000 issue of U.S. Catholic (https://uscatholic.org/ articles/200910/no-forgiveness-no-futurean-interview-with-archbishop-desmundtutu/).

n What did you find most challenging in this issue?

n Where in your life do you see the need for reconciliation? What would restorative justice mean in this context?

n What does the Christian call to forgive your enemies look like within the context of crime and victimization?

n Are there any specific ways you can get involved in transformative justice, either as an individual or in community with others?

Tutu at the COP17 “We Have Faith: Act Now for Climate Justice Rally” in Durban, November 2011 © Kristen Opalinski - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

FALL 2022 • NO. 135 14

“My humanity is caught up in your humanity, and when your humanity is enhanced—whether I like it or not—mine is enhanced as well. Likewise, when you are dehumanized, inexorably I am dehumanized as well.”

LATE SUMMER TO EARLY FALL EVENTS Sixth Annual Immigration Summit

On August 27, Catholic folks from the Seattle area participated in the sixth Annual Immigration Summit, which was titled, “Catholics Engaging in Immigrant Justice.” The faithful lived out their commitments to honoring the sacredness and dignity of human life by engaging in sessions that honored the stories and experiences of our immigrant siblings, as well as a town hall, which called upon Congressman Adam Smith to support immigration reform. The Immigration Summit resulted in over 100 community members sending letters to representatives urging them to support immigration reform bills.

It is not too late to take action for immigration reform. Write a letter in support of the bills listed above at: tinyurl.com/5f8n7yr9

Justice for Women

Youth Action Team Internship

UPCOMING EVENTS Prophetic Communities: Organizing as an Expression of Catholic Social Thought

On September 17, the Justice for Women program, guided by their Leadership Advisory Team, organized Semillas de Cambio, a large in-person gathering in Tacoma for former facilitators and active participants of the Women’s Justice Circles. Roughly 50 Latina women from over 20 cities in Washington and Oregon joined in community for a workshop focused on networking, needs assessments related to mental health, community commitments, leadership development, and spiritual and emotional healing from patriarchy and colonization. This gathering is the foundation of many more meetings of the facilitators in the seasons and years to come!

On September 9, Youth Action Team co-facilitators Sarah Pericich-Lopez and Will Rutt held an Orientation Retreat to welcome 10 Seattle area Catholic high school junior and seniors into IPJC’s youth organizing internship program. Since mid-September, the interns have been guided through weekly workshops provided by local and national organizers pertaining to the topics of identity, storytelling, communication and listening skills. Sarah and Will have intentionally integrated faith formation and Catholic social teaching to holistically develop the interns as community organizers. On October 19, the interns participated in their first major event, which allowed them to meet with local organizers and practice their one-to-one relational skills before beginning community outreach.

Justice Rising Podcast

Season 3 of Justice Rising began in late September. We welcome Cecilia Flores as the new host and producer. Cecilia’s effervescent personality and vast justice knowledge has already produced a number of episodes with depth, vulnerability, and challenging topics. Cecilia has committed season 3 of Justice Rising to evaluating the intersection of justice and culture. You can find links to listen to Justice Rising on your preferred platforms here: ipjc.org/justice-risingpodcast/.

We are excited to co-sponsor an organizing conference with the University of San Francisco (USF) and Jesuits West in February 2023. Held at USF, this conference is a gathering is for organizers, theologians, and all committed to social justice work to explore the intersection between Catholic social teaching and community organizing.

Subscribe to our email list to receive more information about Prophetic Communities: ipjc.org/sign-up-forour-e-newsletter/

Donations

IN HONOR OF Maureen Augusciak Judy Byron, OP Stacy & Alan Klibanoff Sisters of Providence, Seattle Local Community

IN MEMORY OF Mother of Dr. Tiong-Keat Yeoh, M.D.

REMEMBERING WITH GRATITUDE Mary Brennan Kohli | 1930-2022

In addition to being a mother of nine children and a nurse, Mary gave of her time, talent, and treasure to IPJC and her community. She believed and lived, “This is my community and it’s my responsibility to make it better.”

FALL 2022

17 09 22

© Tamara Adams Art

Semillas de Cambio

—TOM M c CALL

15 A MATTER OF SPIRIT

Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center

Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center

1216 NE 65th St Seattle, WA 98115-6724

SPONSORING COMMUNITIES

Adrian Dominican Sisters

Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace Jesuits West Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, U.S.-Ontario Province

Sisters of Providence, Mother Joseph Province Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia Tacoma Dominicans

AFFILIATE COMMUNITIES

Benedictine Sisters of Cottonwood, Idaho Benedictine Sisters of Lacey Benedictine Sisters of Mt. Angel

Dominican Sisters of Mission San Jose Dominican Sisters of Racine Dominican Sisters of San Rafael Sinsinawa Dominicans

Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Sisters of St. Francis of Redwood City Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Sisters of St. Mary of Oregon Society of the Holy Child Jesus Sisters of the Holy Family Sisters of the Presentation, San Francisco Society of Helpers Society of the Sacred Heart Ursuline Sisters of the Roman Union

EDITORIAL BOARD

Gretchen Gundrum

Vince Herberholt

Kelly Hickman

Tricia Hoyt

Nick Mele

Catherine Punsalan-Manlimos

Will Rutt

Editor: Emily Sanna

Copy Editor: Gretchen Gundrum

Design: Sheila Edwards

A Matter of Spirit is a quarterly publication of the Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center, a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, Federal Tax ID# 94-3083964. All donations are tax-deductible within the guidelines of U.S. law. To make a matching corporate gift, a gift of stocks, bonds, or other securities please call (206) 223-1138. Printed on FSC® certified paper made from 30% postconsumer waste.

Cover: The Restorative Justice Singing Tree Mural co-designed with AIMS high school students focusing on repairing harm and building trust, see pg.10; detail at right ipjc@ipjc.org • ipjc.org

Prayer for Restorative Justice

God, Our Creator,

We acknowledge the ancestors and original owners of this land, a land of wealth and freedom, far horizons, mountains, forest, and shining sand.

Maker and Spirit of Earth and all creation, let your love possess our land and may we share in faith and friendship, the gifts unmeasured from your hand.

We pray for all the imprisoned, those on the inside, whose confinement is obvious as well as those on the outside, whose imprisonment is subtler.

We reach out in grace, knowing that human divisions are false, that we are not the innocent praying for the guilty or the right praying for the wrong but people praying for people, the hurt remembering the hurt, the failure reaching out in love to the failure in a single community.

We remember those who seek to change difficult life stories, midwives of hope and agents of grace.

We remember and pray for the victims of crime on the outside, knowing that we do not have the luxury of black and white, the simple answer or the easy question.

We remember and pray for the countless victims on the inside, casualties of uneven playing fields and difficult starts, dreamless futures and nightmare pasts.

We remember the whole criminal justice system and its process, those caught up in it, those on every side and in every moment of it.

We pray a blessing on all those who enter prison.

We pray a blessing on all those who wait on the outside.

We pray a blessing on the world community.

Teach us to deal with each other with compassion.

Keep all of us ever mindful of your law of love so that we may temper justice with mercy, exercise control with compassion.

May our motives and our actions conform to your will and fulfill your purposes all the days of this life so that we may share in the life to come.

Amen.

—AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC SOCIAL JUSTICE COUNCIL

ORG.

NON-PROFIT

US Postage PAID Seattle, WA Permit No. 4711

Emily Sanna

Emily Sanna

Editor’s conversation with Dr. Gilda Sheppard and Kimonti Carter, October 2022

Editor’s conversation with Dr. Gilda Sheppard and Kimonti Carter, October 2022

BY CHRIS HOKE

BY CHRIS HOKE