Liminal Spaces

Reimagining Schoolyards

Data on “great”

Playgrounds Nature vs. Anything Adventure Play & Climate Change

OFFICERS

President Robyn Monro-Miller

Australia

Vice President Kathy Wong Kin-ho

Hong Kong

Membership Tam Baillie

Scotland

Development Sudeshna Chatterjee

India

Communications Cynthia Gentry USA

Treasurer Mike Greenaway Wales

UN REPRESENTATIVE

Roger Hart

IPA COUNCIL MEMBERS (MAY 2023)

Argentina Beatriz Caba

Australia Robyn Monro Miller

Brazil Janine Dodge

Canada Marjorie Cole

England Meynell Walter

Germany Gerhardt Knecht

Hong Kong China Dr. Maggie Koong

India Sruthi Atmakur Javdekar, PhD

Israel Sheana Braizblatt

Japan Hitoshi Shimamura

New Zealand Shyrel Burt

Nigeria Abimola Nwozuru

Northern Ireland Jacqueline O’Loughlin

Portugal Frederico Duarte Lopes

Scotland Anne-Marie Mackin

Sweden Nik Dee Dahlstrom

Taiwan Shih-Tsung Chang

USA Deb Lawrence

Wales Marianne Manello

EDITOR: Cynthia Gentry (USA)

Magazine feedback: We welcome your comments and suggestions at communications@ipaworld.org. All inquiries regarding the reproduction of any material which appears in PlayRights for any purpose whatsoever should be directed in writing to the editor. The views expressed in articles within PlayRights are those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPA. The publishers, authors and printers cannot accept liability for errors or omissions. © 2023 IPA

Cover Photo: © Laird Williams

What the International Play Association is and how you can join

IPA is a dynamic international organisation with members in five continents and more than 40 countries. It has active groups throughout the world and enthusiastically welcomes new members and new energy!

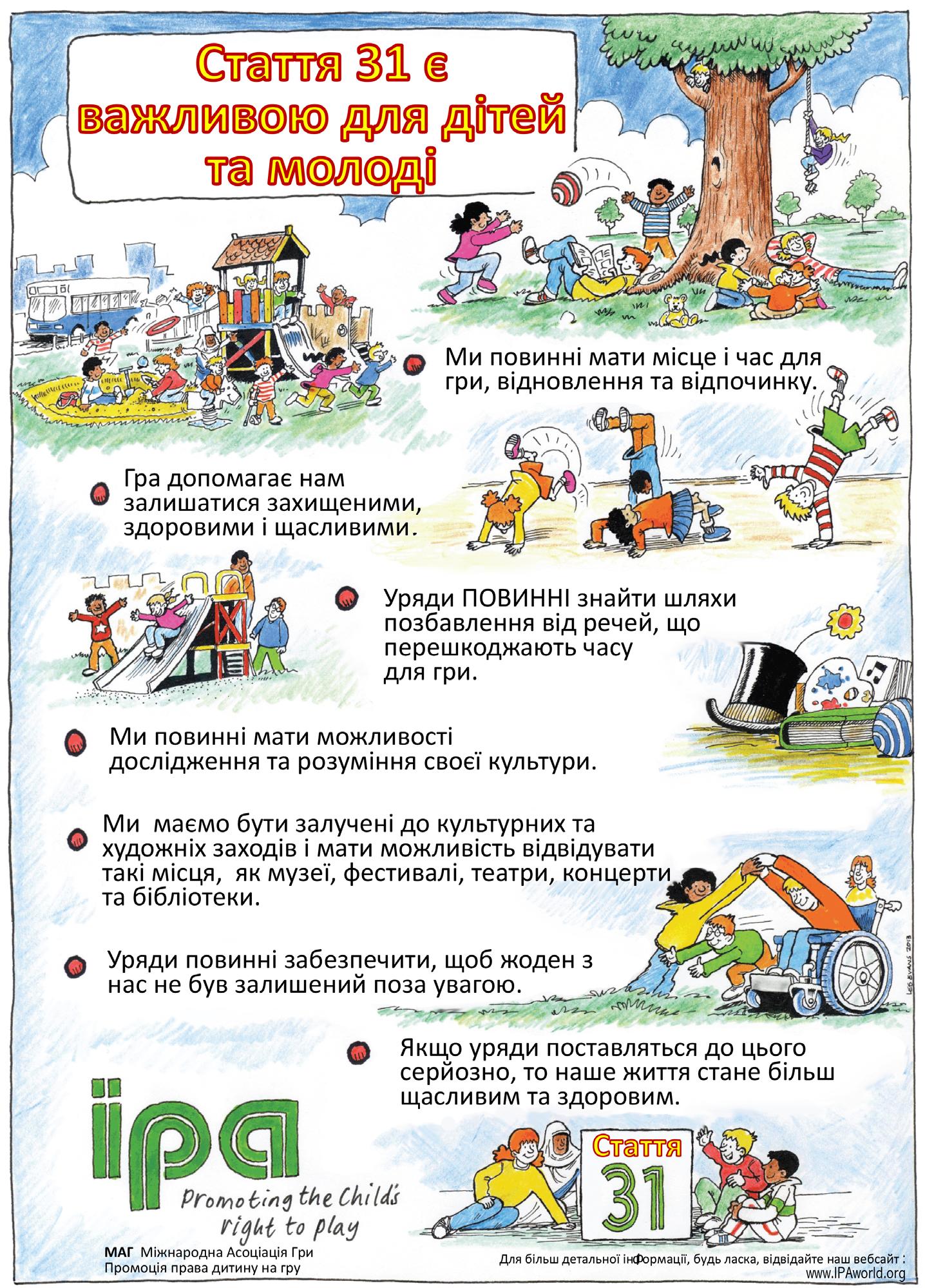

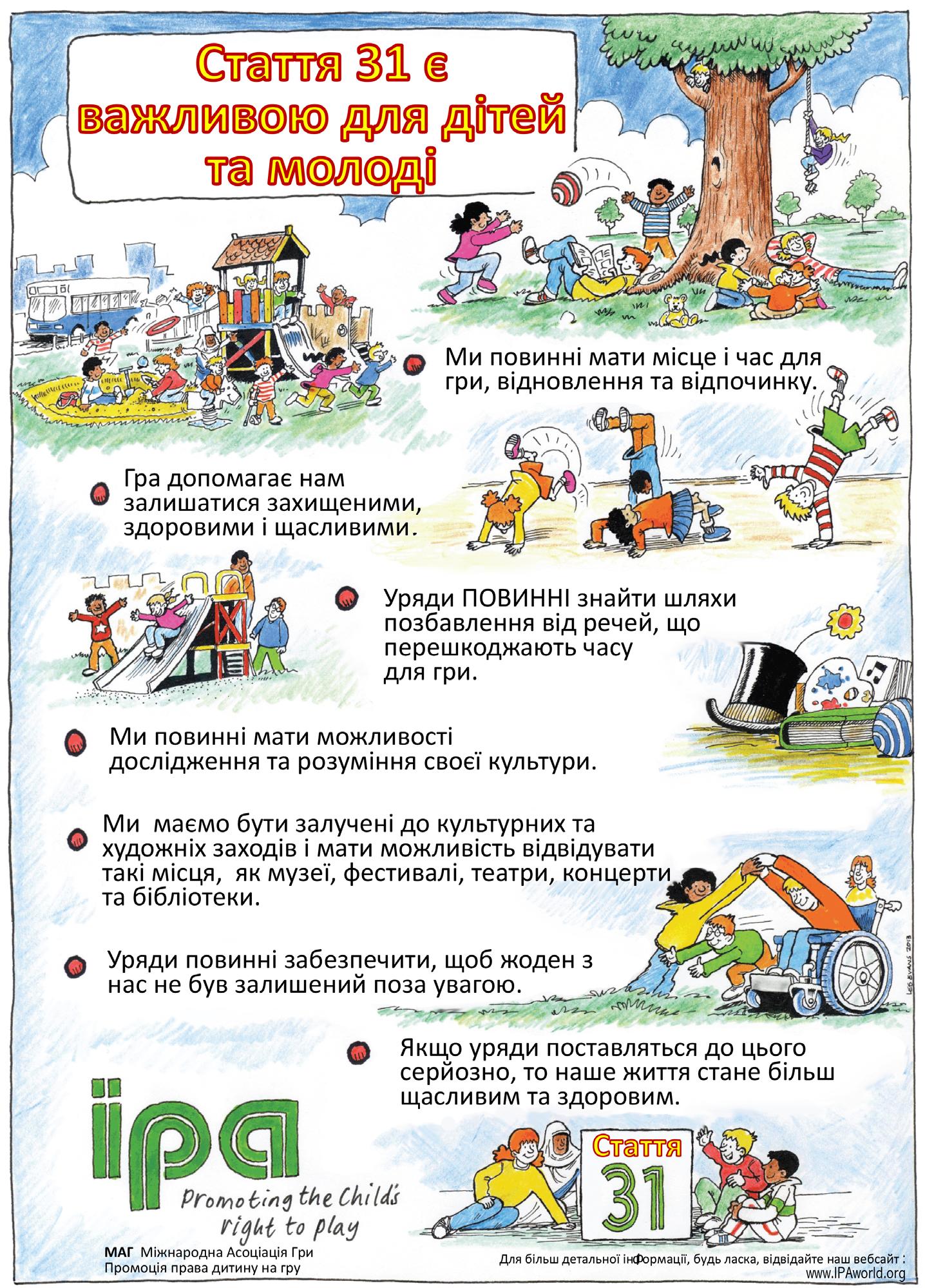

IPA’s purpose is to protect, preserve and promote the child’s right to play as a fundamental human right. The organisation was instrumental in establishing “play” (article 31) in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and in developing the general comment (General Comment No. 17) on article 31 for the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child.

IPA recognises that the well-being of children is a global issue, and that opportunity for play is an important element of well-being. Play is children’s natural behaviour and their healthy development is dependent upon sufficient time and opportunity to play.

IPA is an interdisciplinary organisation bringing together people from all professions working for and with children. For over sixty years national groups have initiated a wide variety of projects that promote the child’s right to play.

IPA’s worldwide network promotes the importance of play in child development, provides a vehicle for interdisciplinary exchange and action and brings a child’s perspective to policy development throughout the world.

IPA welcomes you, or your organisation, to join its international network and participate in its campaign to promote the value of play around the world.

You can contact IPA through your national representative listed on our website. Visit ipaworld.org , or email the IPA Membership Officer at membership@ipaworld.org. You can join IPA through the website at IPAworld. org/join

2 PLAYRIGHTS • IPAWORLD.ORG

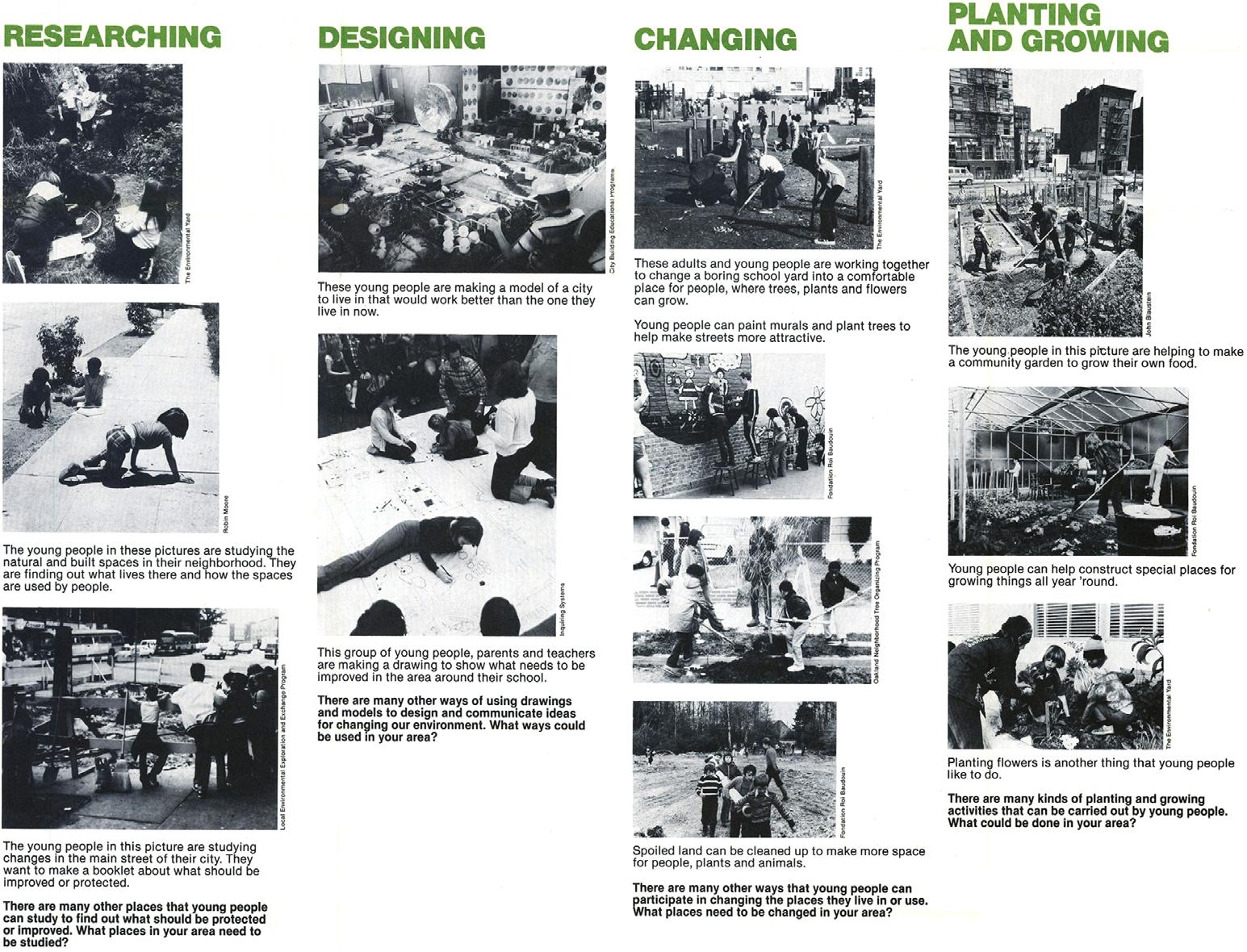

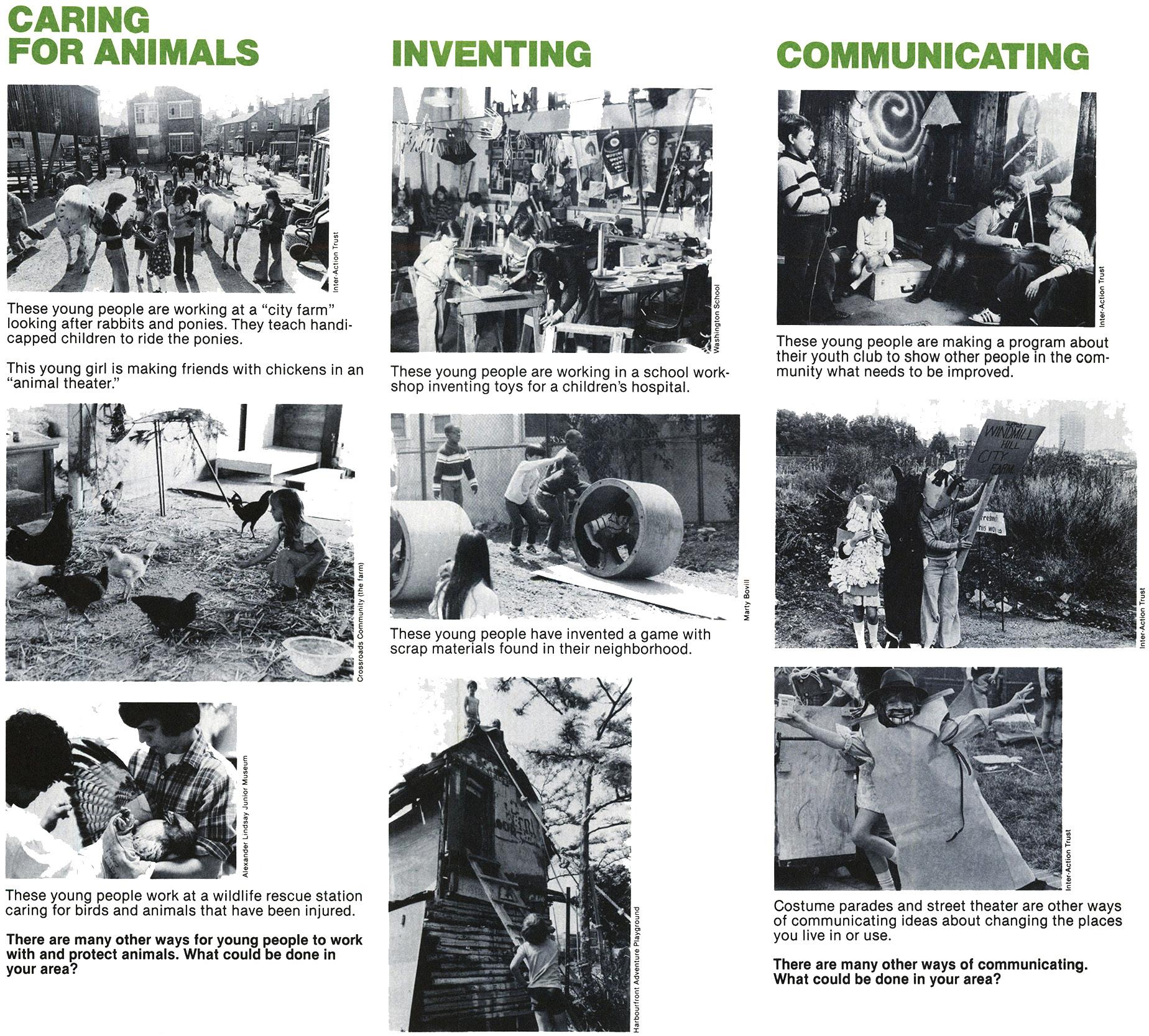

4 PRESIDENT’S LETTER 5 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 6 LIMINAL SPACES: INTERSECTING CHILDREN’S RIGHT TO THE ENVIRONMENT AND RIGHT TO PLAY 14 REIMAGINING SCHOOLYARDS TO IMPROVE HEALTH AND LEARNING 22 WHAT MAKES A PLAYGROUND GREAT? 26 NATURE VS. ANYTHING: PLAYING WITH MATERIALS 32 FRESH AIR, FUN PLAY: AIR POLLUTION INITIATIVES TO RESTORE PLAY IN CHILDHOOD 36 ADVENTURE PLAY FIGHTS CLIMATE CHANGE 38 CHILDREN CAN TOO 42 CHILDREN’S LOVE OF NATURE JUNE 2023 3 6 14 32 22 36 38 26 42

Photo: Steve McCurry

Letter

Outdoor play was the foundation of my early years spent building unsafe structures in the bushland of Sydney, Australia. The long, complex games that lasted days, or even a Summer, were an integral part of my childhood. This play was undertaken oblivious to the fact I was fulfilling a basic and evolutionary function for my development and for my survival.

Play is not optional for healthy development nor is it unique to humans. Play is a biological imperative and the primary mechanism through which the young, both human and animals, explore their physical environments.

A critical element to play is also the innate need to connect with nature. Children play instinctively with natural elements: water, fire, mud. Nature is one of the most beautiful environments for loose parts play, a ready-made play space offering diversity, flexibility, creativity, challenge, risk, symbolism and my personal favourite, the ability to experience awe and wonder through the unexpected discoveries that nature provides.

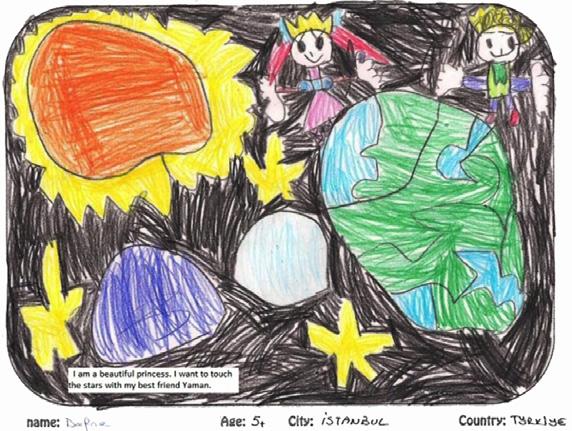

The release of this edition of PlayRights coincides with the adoption, on 26 May, of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comment on “Children’s Rights to a healthy environment with a special focus on climate change”. The UN Committee responded to the call from children and young people around the world to promote climate change as one of the most crucial concerns facing the world today and impacting on all children’s rights.

Due to be launched in September the guidance of the General Comment will be critical to ensure that children’s rights – many of them undermined by the impact of climate change, are upheld and duty bearers held to account. Children’s rights in the UNCRC are indivisible, each one of equal importance. So General Comment No. 26 will inform each of the rights including, the right to play.

There is an ever-increasing evidence base that supports the benefits of the outdoor play in nature for healthy development, including Danish research concluding that children who grow

up with greener surroundings have up to 55% less risk of developing various mental disorders later in life1. (Ref. on p.43.)

However, more than just the health benefits provided by outdoor play, there is the reality that to be able to protect the environment we must have an understanding and appreciation of it.

The connections to nature, based upon our early play experiences, set the foundation for the rest of life. Research on biophilia among children and youth in varying contexts, concluded that experiences with nature may turn into a “life-affirming orientation” (Kahn 1997) and that children who are exposed to, and engaged with nature show an awareness and appreciation which resulted in a stronger long term relationship with the natural environment (Louv, 2005, Cheng and Monroe, 2010).

I recently visited the children from St Mirin’s in Glasgow, during the lead up to the IPA Conference. As I wandered through their natural place space known as “Woody Woodland”, filled with huts, mud kitchens and canopies of green cover, my heart skipped a beat and the dopamine rush kicked in. I was transported, back to the days of adventure, risk, and experimentation. It was truly joyful.

This edition is a dedication to those of us who seek to create environments that inspire that same feeling of joy for all children. It may not be in a school playground, play spaces can be everywhere, spaces that engage brains, bodies, imaginations, and hearts. I believe that the mosaic of play spaces we create for children and the time for children to engage with them, will be the greatest contribution we can make to the global environment movement.

Play is not just important for today; it is critical to ensuring there is a tomorrow.

Robyn Monro Miller AM President

4 PLAYRIGHTS • IPAWORLD.ORG

from the president

Photo: David Yearley

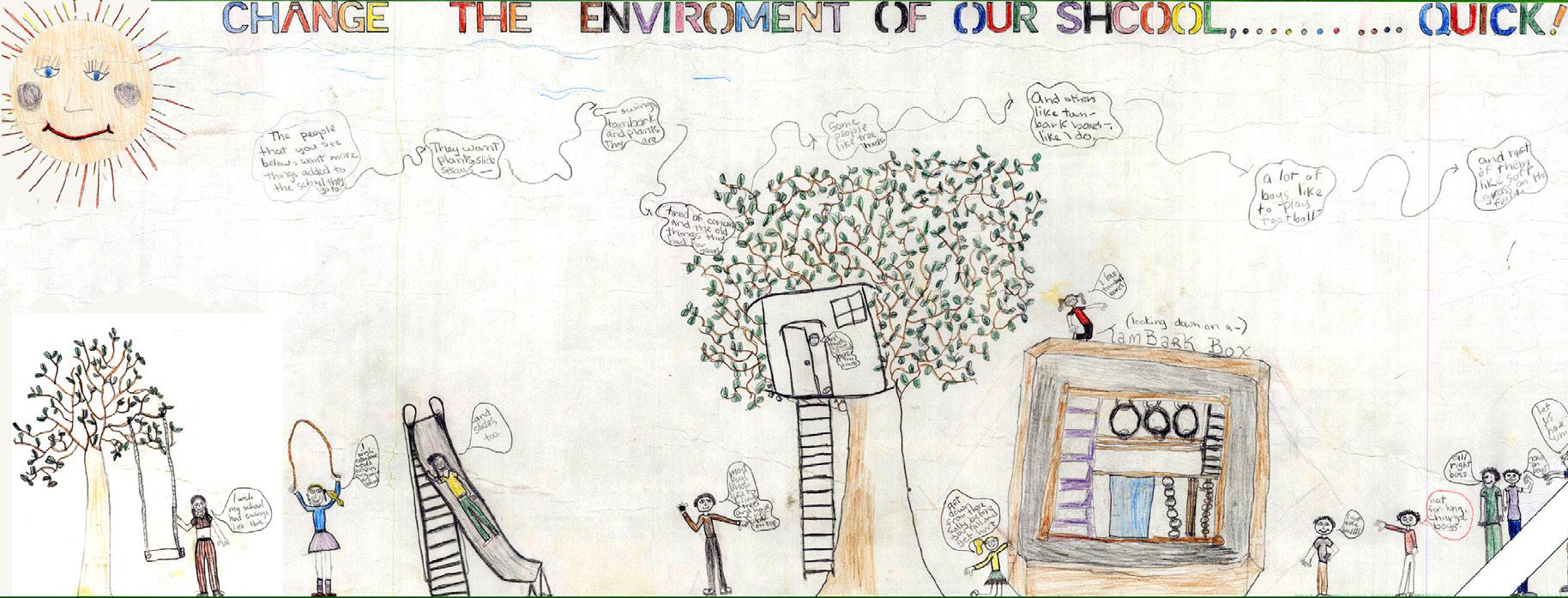

This issue of PlayRights Magazine dips its toe in the vast oceanic topics of climate-change, nature, environment, children and play. It is so clear that the world around us is battered, poisoned, burned, and shaken within an inch (or degree) of its life. As it falters, my personal need for inner peace has grown significantly. When I was a child that need could be met by climbing into the reassuring branches of a tree. There was no separation between nature, the environment, and play in those days. The outdoors welcomed us each day and supplied us with limitless loose parts, adventures, dangers real and imagined, curiosities, breathtaking vistas, fresh clean air and water, challenges… and so very much more. It was as welcoming as home. In many ways it was home. Now, I find myself quite near to obsessed with helping today’s children make such a connection, too.

The term biophilia, first coined by Eric Fromm and then popularized by the great Edward O. Wilson, refers to the “innate affinity people have for the natural world” (Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design by Stephen R. Kellert). It’s in our DNA to love the planet and all the beauty upon her. But, you’d have to be sleep walking through life not to know about the fate that lies before this planet if humans do nothing to change the liberties we take each day. Where has innate affinity gone?

In a recent conversation with Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children From Nature-Deficit Disorder (for an article to appear here, but which remains on my computer), he stressed that though “we certainly have made progress in awareness of spending time outdoors and its impact on health…. (we) also found...that the barriers have not gone down, awareness of this issue and knowledge about it does not necessarily translate into action.”

So, my parting words as Editor of PlayRIghts Magazine are let those of us who care so deeply for the wellbeing and rights of all children appoint ourselves as the ones who will take up the challenge to preserve this majestic round playspace for our children. We are already battle worn and experienced. Certainly, there is not a single playworker who has not watched an audience’s eyes glaze over while we excitedly tabulate the benefits of play for a child. It is virtually the exact same reaction one gets when discussing what we must do to save the planet. We can take this on. (Just don’t bring up bacon. It appears the thought of giving up bacon is the one thing that drives a thinking man over the edge. Save that for later.)

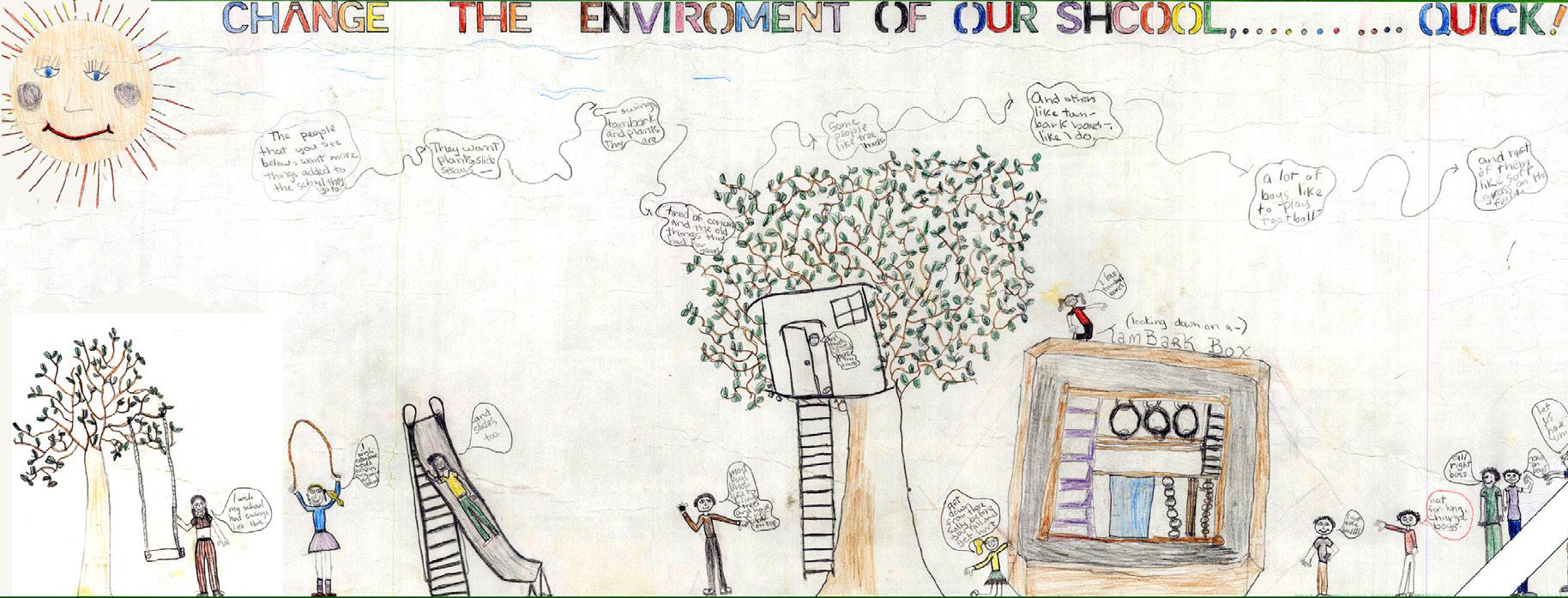

The only thing I know to do to “change the world” is to start where I am. I build playgrounds and the playgrounds I build have flowers, rolling hills, big trees, grasses, loose parts that fall from trees, treehouses and beauty. It’s also all I know how to do to help children fall in love with nature… and it works.

So, start where you are. There is no difference between saving the world for children and play and saving the world. Do what you do with all of your heart and then link arms with the person sitting next to you. What better place than in IPA to find kindred spirits who know how to make every day better?

Cynthia Gentry Communications Officer and Editor, PlayRights Magazine

JUNE 2023 5 letter from

the editor

Photo: David Yearley

Liminal Spaces:

by Sudeshna Chatterjee

Platform of Hope, Dhaka, Bangladesh Archnet

by Sudeshna Chatterjee

Platform of Hope, Dhaka, Bangladesh Archnet

Intersecting children’s right to the environment and right to play

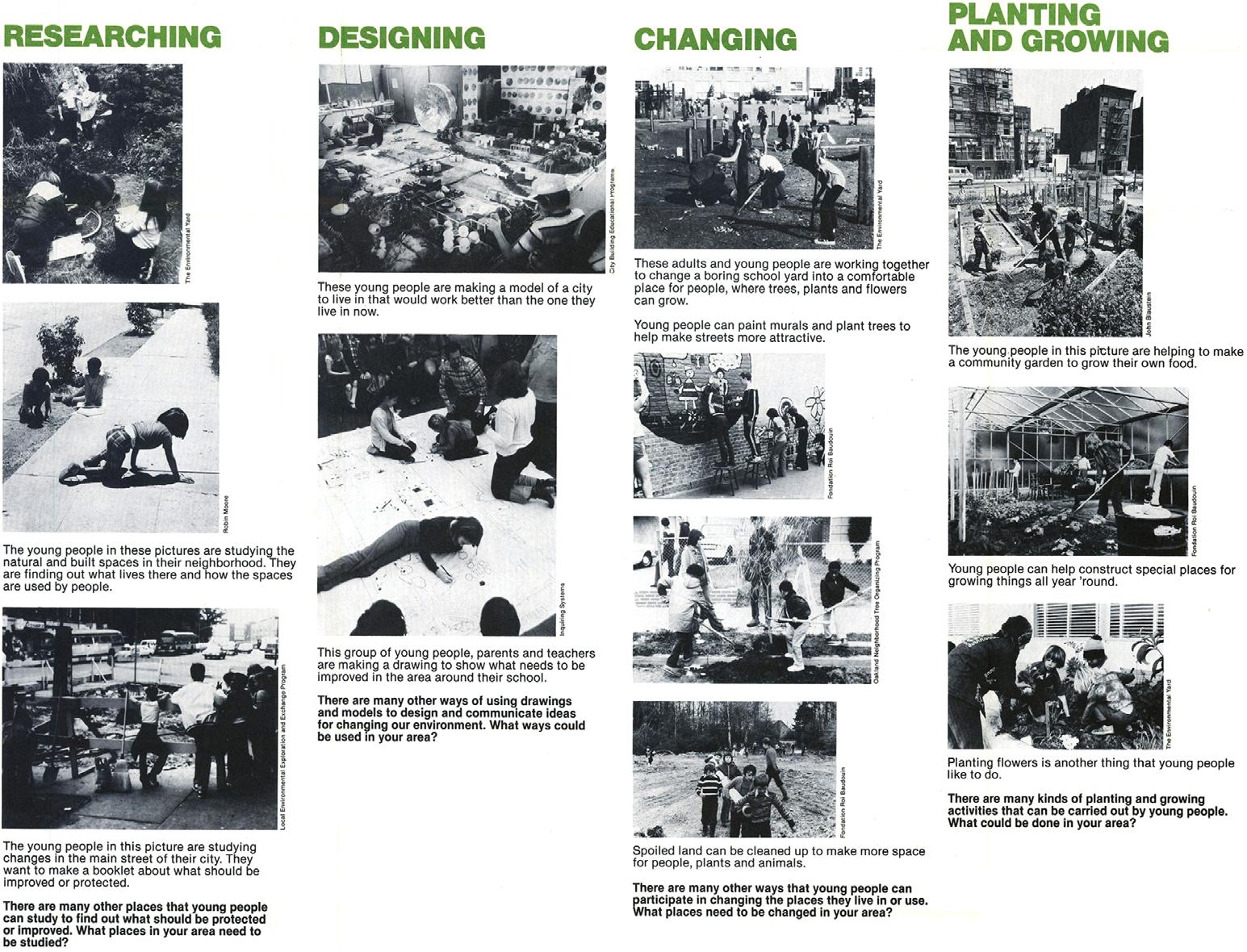

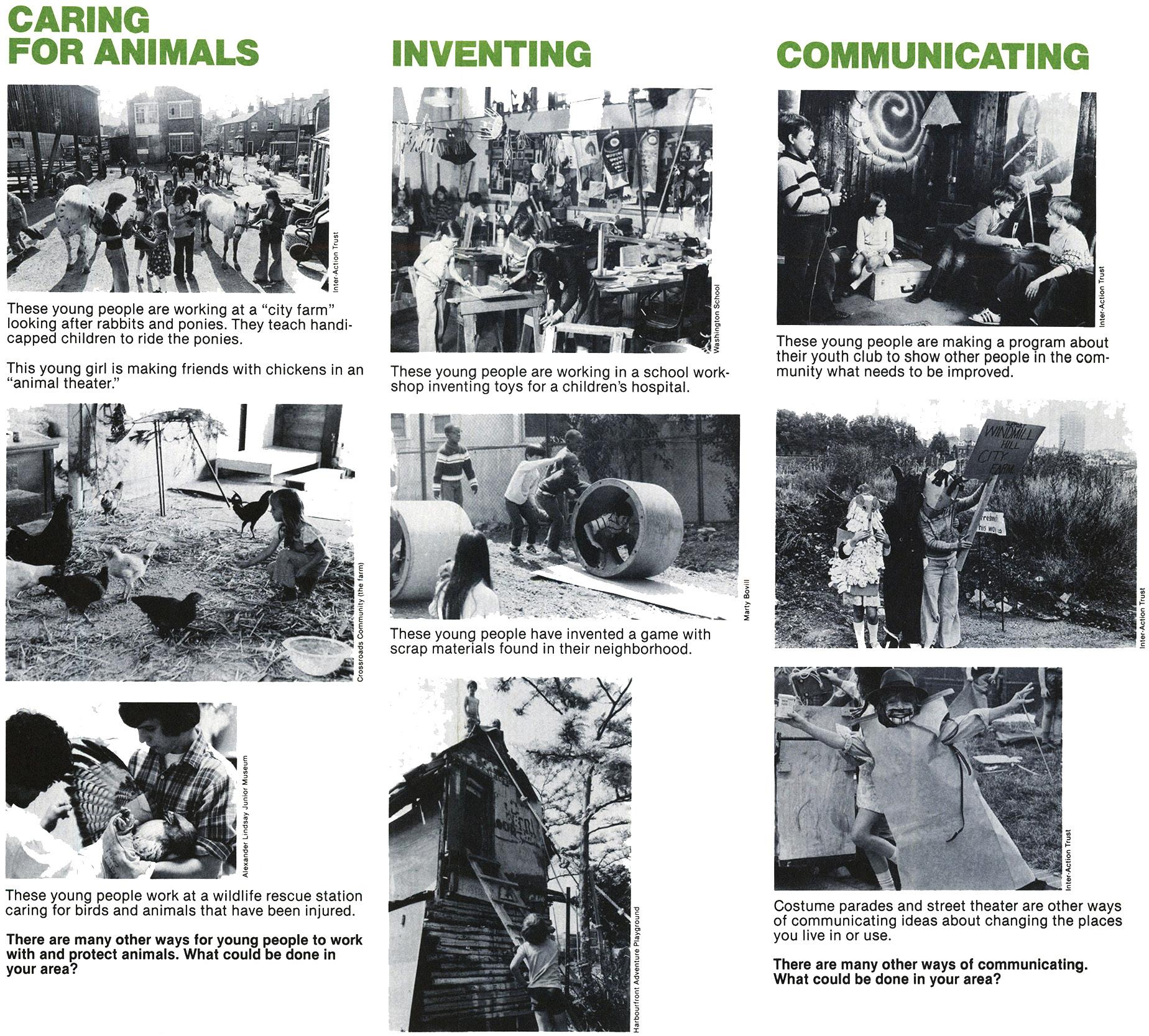

Cities across the world vary greatly in terms of the availability and accessibility of play spaces for children. With rapid urbanization, growing inequality, environmental degradation, and the impacts of climate change affecting urban children everywhere, children’s opportunities to play outdoors are shrinking. Further, the built-up area expansion of many cities encroaches upon vacant open spaces and natural green and blue spaces due to the pressures of urbanization. These environmental losses have lasting impacts on children’s access to everyday play spaces. Irrespective of these challenges, children seek out and claim a diverse range of outdoor places as their own. However, these children’s places often do not fall into neat categories but exist only as liminal or incidental or accidental spaces within the built and natural environments of cities. But the imagination of planned environments for children mostly continues to be conceived as protective and regulated play environments such as parks and playgrounds.

Such a narrow conception of play spaces limits children’s right to play. When coupled with a lack of permission and time for play, children have diminished opportunities to explore and engage with the local environment in ways that are meaningful to them. This robs children of their right to the environment and the right to play. For disadvantaged children in particular, playing in liminal spaces is one of the only ways to claim the right to play and the environment on their own terms. For children, liminal spaces are any leftover, informal, or accidental spaces that they can seek out for free play close to home or far away, especially when formally planned and designed play spaces are not available to them in their local area. Within neighbourhoods, these spaces could range across unused sidewalks, empty parking spaces, wild and planted spaces, unkempt waterfronts, vacant lots, spaces between buildings, accessible roofs, and terraces among others. Some of the richest free play occur in liminal spaces, especially for children living in informal settlements, in street situations, and in temporary housing after a disaster. In the forthcoming Principles and Guidance for Public Spaces for Children by UNICEF, UN-Habitat and WHO such liminal spaces have been recognized as an important category of public spaces for children.

In this short article, I will show that to foster cities that are respecting of children’s rights we need to reconceptualize public spaces for children to include spaces of liminality by working with children and drawing upon their experiences and also by engaging with diverse stakeholders for claiming/shaping liminal spaces in urban areas. I will draw on the work that I had the opportunity to lead for the development of the Principles and

Guidance for Public Spaces for Children (forthcoming) for the United Nations. This is accompanied by a compendium of 50 case studies based on about 118 cases from around the world that were collected and developed for the project. The eight case studies chosen for this article are drawn from Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, Egypt, India, Kenya, Lebanon, and Mexico. They are organized into three categories related to the pathways through which they were created: 1) government policies and programmes, 2) civil society organization led initiatives, and 3) volunteer community architect led creation of local play spaces.

Government policies and programmes

The policies, programmes and processes by different levels of government enable the creation of public spaces for children in different contexts. In this section, I discuss three case studies that resulted in the transformation of liminal spaces into public spaces for children with play at their heart triggered by national government programmes (the first two cases) and local government action (the third case).

Reclaiming a dry drainage canal for play within social housing, Fresnillo, Mexico

Mexico’s Social Housing Renewal and Revitalization Programme that was active between 2014 and 2018, commissioned lowcost, easily maintainable, durable, practical, and flexible solutions for upgrading public areas in run-down and crime-ridden social housing developments. The program led to the creation

JUNE 2023 7

Fresnillo, Mexico: A dry drainage canal enhanced for play, dance, and more – Before Sandra Pereznieto/ Rozana Mondial Studio

of dozens of public and communal spaces within social housing. A notable example that understood the essence of liminal spaces for children’s play and designed play affordances within the space can be found in the city of Fresnillo, home to 40,000 residents that were once beset by crime and drugs. A key feature of the social housing was a half-kilometre-long dry drainage canal that bifurcated the housing. The architects observed the spontaneous ways that children played in the drainage run – such as sliding down on the sides on garbage can lids – and decided to retain and enhance the form of the canal with slide-able and sitable spaces to overlook a resurfaced area at the bottom of the canal. The slopes of the canal were repaved with concrete lattice which allowed for vegetation to grow in the gaps and different blocks were used to create, sideways steps, stepping stones, and climbing walls. Additionally, a perforated steel bridge was added to connect the two sides of the canal with several play and socializing elements incorporated at the top and lower levels of the bridge. The intervention is overlooked by housing blocks on either side enabling caregivers to keep an eye on their children. It provides the community with much-needed public space that is actively used for children’s play, celebrations, social gatherings, and programs such as samba classes.

Wayside playspaces, Kohima, Nagaland, India

The national Smart Cities Mission (SCM) by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India collaborated with Bernard van Leer Foundation to host a national

challenge called Nurturing Neighbourhoods Challenge (NNC) with the technical support of WRI India. It aimed for neighbourhood-level improvements to promote healthy early childhood development (0-5-year-olds) through this national city development/improvement programme. The challenge occurred in a phased manner, first through pilot projects in 25 cities, and then scaling up interventions in 10 cities selected by an expert jury based on the quality of the pilot projects.

https://easternmirrornagaland.com/kohima-wins-real-playchallenge-2022-und/

8 PLAYRIGHTS • IPAWORLD.ORG

Fresnillo, Mexico: A dry drainage canal enhanced for play, dance, and more – After Sandra Pereznieto/ Rozana Mondial Studio

Playful parklets created from space claimed from the road in Kohima, Nagaland, India

One of the successful participating cities is the land-starved hilly city of Kohima, the capital of one of India’s neglected northeastern states, Nagaland. Here the local government worked with citizens to find out the play needs of children. The pilot project under NNC claimed space from the right of way of a main road that was typically undefined and waste-laden and developed it into terraced parklets for young children and their caregivers. Safer access to the stepped space is ensured by introducing speed-calming measures, pedestrian crossings, and waiting spaces on the road. This safe space has provided play opportunities for around 200 young children in the community.

Park under a flyover, Calgary, Canada

Calgary’s first tactical intervention became a permanent public space for children by reclaiming a derelict liminal space under a complicated interchange of roads and bridges. The City of Calgary had no plans to activate the empty space under the 4th Avenue flyover until a community-led tactical urbanism project installed a pop-up park revealing the potential of the space. The 4th Avenue Flyover underpass was a redundant liminal space –perceived by residents as an unsafe area that frequently hosted antisocial behaviour. At night, especially, the underpass was dark and unwelcoming, and it had become commonplace for children, families, and women to avoid the space altogether. Parks Foundation Calgary worked with stakeholders including

The City of Calgary, Bridgeland-Riverside Community Association, students of Riverside School, and students from the University of Calgary, to oversee the planning, design, and implementation of the park. Students from Riverside School took part in a series of activities related to designing and planning the park. Through the process, students discussed challenges, solved them through design thinking, and eventually saw the park developed and activated. Students learned about the importance of creating public spaces to positively impact the community. In 2020, following four years of collaborative work between children and adults, civil society, the community, and public agencies, the Flyover Park transformed a derelict liminal space into a bright and welcoming park at a major Calgary commuter corridor. It is now used for events, student field trips, markets, and festivals, in addition to being a community hub where kids and community members of all ages and backgrounds can gather, play, and learn.

Civil society organizations led initiatives

Around the world, multi-stakeholder partnerships comprising different civil society organizations such as NGOs, universities, citizen groups, and international agencies are playing an important role in reimagining ways in which liminal urban spaces can be shaped and transformed so they are respecting children’s rights. In our work, we found that the civil society organization led pathway is one of the biggest producers of local and community-level public spaces for children and witnesses greater involvement of children through participatory design.

The Changing Faces Competition, Nairobi, Kenya

The citywide Changing Faces Competition in Nairobi is run by the Public Space Network (PSN), which is a collective of civil society, public and private stakeholders, and urban experts interested in creating a cleaner, greener, safer, and inclusive Nairobi through the transformation of its public spaces. Nairobi, over the years, has witnessed many youth-led public space improvement and development projects within different neighbourhoods where art or sports-led initiatives catalysed many projects. However, these localised social movements have failed to scale or connect with each other for greater impact. Given the limited resources of the Nairobi City County Government, the civil society-led pathway is crucial to developing public spaces at scale. PSN created the Changing Faces Competition (CFC) to offer a common platform to the different placemaking groups across Nairobi to work on public space improvements and development. Any formally registered

JUNE 2023 9

Calgary, Ontario, Canada: The Flyover Park under the 4th Avenue Flyover on memorial Drive and Edmonton Trail City of Calgary

civil society group, such as self-help groups, communitybased organizations, and resident associations can participate. The competition requires groups to identify a neglected space in their neighbourhood, and crowdsource resources for the transformation using locally available and donated materials and equipment. A jury of urban experts chooses the best projects and the winning teams receive a monetary award. The idea of the competition came from the Dandora Transformation League (DTL), a founding member of PSN, that since 2014 had run three competitions in the Dandora neighborhood, mobilizing over 3,000 youths that transformed 120 public spaces. The Changing Faces Competition has run four editions since 2014, transformed 200 plus public spaces involving 4000 plus participants, provided clean, green play spaces for children, reduced crime, and improved community safety. The teams are encouraged to identify new incomegenerating activities related to the maintenance and activation of the transformed spaces to ensure their sustainability.

‘Makani’ – My Place/Street in Karantina neighbourhood, Beirut, Lebanon

Karantina is a low-income multi-ethnic neighbourhood located in the Medawar district in close proximity to Beirut’s city centre. In 2020, the Beirut port blast, which occurred just 600m from the Karantina neighbourhood, resulted in significant damage to houses, streets as well as the only public park. This park was renovated into a play garden in 2016 by Catalytic Action (CA), a UK-based charity with extensive experience in co-creating play spaces with children and communities in situations of

10 PLAYRIGHTS • IPAWORLD.ORG

The Changing Faces Competition, Nairobi, Kenya Public Space Network https://www.publicspacenetwork.org/ about-cfc

Public Space Network

Beirut, Lebanon: Children and community co-create a vibrant public space CatalyticAction

crisis across Lebanon. In December 2021, CA returned to the Karantina neighbourhood to embark on a neighbourhood spatial intervention to support the rehabilitation efforts after the blast. The outcome was the creation of ‘Makani’ – My Place/Street that claimed a liminal space owned by the city and officially registered as a sidewalk for developing a vibrant public space for children. This site was chosen by children and community members as it was close to where many children lived. Participatory design workshops with local community groups, including children, revealed the community wanted a place that nurtured children’s play, offered a safe shaded place for resting, and provided an aesthetically pleasing space within the neighbourhood. The intervention included a long, wide, and colourful bench that cuts across the space and is used for seating, changing diapers, running along, sliding down, cycling, and skating. The affordances of the bicycle racks provided in the space include sitting, resting, climbing, using as a higher vantage point, and a launch pad for jumping. The colourful mural, painted by children, lends the space a strong visual identity.

Mind the Step: transforming degraded public staircases, Jardim Nakamura, São Paulo, Brazil

Mind the Step initiative in São Paulo, Brazil was developed by a social organization founded mainly by young Brazilian architects and urban designers called Cidade Ativa. They focused on improving the abandoned and degraded public staircases across the city. Through their design interventions, they reactivated the staircases as important pedestrian mobility networks, linking inaccessible hill-side neighbourhoods, and providing vital public spaces enabling people, including children, to gather, play and engage in leisure activities. The first pilot project was in 2014-15 transforming the steps of Rua Alves Guimaraes in Pinheiros, São Paulo, Brazil. Jardim Nakamura, a southern neighbourhood of São Paulo, was the fifth project under the initiative and the renovation took place in 2018. Cidade Ativa, received support from Healthbridge Foundation, Canada, and UN-Habitat, under the Global Public Space Programme to develop this fifth project under Mind the Step. Students, parents, staff of a local school, neighbourhood associations, local artists, and the local government authority were involved in diagnosing the problems of the staircase and its surrounding areas. For the first time, Cidade Ativa used the Minecraft gaming software used by UN-Habitat as a tool for the participatory design of public spaces and engaged the local community, especially young children to participate in the design process. The Local Government Authority took charge of the maintenance of the staircase. They replaced old

São Paulo, Brazil: A community uses Minecraft to help transform and reactivate local staircases

Cidade Ativa

energy poles, installed LED lights, renovated the staircase floor and walls in selected spots, installed trash cans and traffic signage, and regularly cleaned the transformed staircases. Through community engagement, infrastructure change, and capacity building, especially of the local level stakeholders, the transformed staircases offered many multi-functional spaces and affordances through seating arrangements, green breaks, wooden slides for children, a community library, and colourful walls. The improved staircase was found to be especially attractive to women and children.

Volunteer community architect led creation of local play spaces for children

Built environment experts have often offered their skills to engage with urban poor communities to develop vital community spaces. Many of these spaces benefit the children and young people in the community. These projects typically develop through an incremental approach to placemaking where trust is built over time through engagement with the community, and many informal conversations reveal community needs and lead to the creation of small places for children and in some cases larger spaces for the community.

JUNE 2023 11

Inclusive playspace within “Garbage City” in Cairo, Egypt

Manshiyat Naser is a large informal settlement situated around Mokattam Hill on the outskirts of Cairo. Its lower part is commonly known as Zabaleen or Garbage City, as Cairo’s trash collectors live here. Dutch architect, Renet Korthals Altes, the founder of the social organization Space for Play, was living in Cairo for three years. She worked as a volunteer community

architect to design and construct an inclusive play space in the heart of this informal settlement. In consultation with the community, she chose a garbage-filled liminal space next to a school for children with disabilities—the ‘Markaz el Mahaba’ (or the Centre of Love)—that did not have any safe outdoor play space. In order to create a playground, the garbage-filled pocket of incidental open space had to be first cleared of tons of garbage, and only after solving the sewage problem any placemaking activities could take place. Renet designed a wide range of multi-use play elements to accommodate different types of play. Physically challenging play elements were also included to make sure that each child regardless of her disability had an opportunity to take manageable risks and engage in a thrilling play experience. The architect wanted to make the play space environmentally sustainable and integrated many upcycled elements such as sewage pipes as planters and a water tank as a ball basket. She engaged with a local factory to produce nest swings, which had never been used in play spaces in Cairo before. But with her input, these are now part of the manufacturer’s collection. The play space is also open to the siblings of the schoolchildren and to the local elderly for celebrations within the neighbourhood.

Platform of Hope, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Cairo, Egypt: Tons of garbage were removed and replaced with a safe outdoor play space next to a school for children with disabilities

Rene Kolthas, Space for Play

Khondaker Hasibul Kabir is a trained landscape architect and in 2007 started his journey as a community architect in the slum settlement called Korail in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He used his professional skills and training to facilitate and co-create places within the slum. One of his early design interventions happened when he began engaging regularly with children in the slum settlement. In his conversations with them, he discovered what children missed most in their community was a play space they could claim and call their own. Kabir as an avid gardener had started to grow his own vegetables and greens near his rented home in the slum. He began helping children grow their own garden in a liminal space they claimed for themselves. The garden led to children exploring and thinking about other kinds of places they wanted that afforded more diverse play opportunities as well as gathering spaces for their community. This resulted in the co-creation of a raised bamboo platform over the lake abutting their settlement. Children were the main protagonists, designers, and negotiators according to Kabir. While the children managed to largely grow and tend to the garden, they reached out to relatives, parents, and grandparents – anyone who would listen to them in the community – to help construct their bamboo platform. The platform called Ashar

12 PLAYRIGHTS • IPAWORLD.ORG

Before After

Dhaka, Bangladesh: Ashar Macha (The Platform of Hope). Archnet

Macha (Platform of Hope) was built by the community and became a central community node much valued by children and women in particular for play, socializing, and resting. The project was nominated for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

Conclusion

The eight case studies discussed above used different strategies to develop community public spaces, and social and recreational facilities for urban children by claiming liminal spaces. These initiatives not only improved the quality of degraded environments but greatly expanded opportunities for children to explore and engage with their local environment. All of them promoted genuine engagement with a broad and diverse range of stakeholders, in particular the local community, children and young people, and those suffering from social exclusion. The cases also highlight there is no single right solution and the best examples are co-created community public spaces prioritizing local knowledge and children’s direct experience, needs, and aspirations for play, safe mobility, and everyday freedoms.

Bibliography:

Chatterjee S (2018) Children’s Coping, Adaptation and Resilience through Play in Situations of Crisis. Children, Youth and Environments 28(2). University of Cincinnati: 119–145. DOI: 10.7721/chilyoutenvi.28.2.0119.

Chatterjee, S. & Nallari, A. (forthcoming). Reimagining Urban Liminal Spaces as Children’s Places And Why They Are Important To Securing Children’s Right To The City. In K. Bishop and K. (Eds.). The Routledge Handbook of the Built Environments of Diverse Childhoods. New York: Taylor & Francis/Routledge.

Chatterjee, S. & Nallari, A. (forthcoming). Right policies, processes, and solutions for community public spaces, social and recreational facilities for urban children in poverty. In E. Delamonica and A. Minujin (Eds.). Child Poverty and Inequality. Practical Guide on Concepts, Measures, and Policies. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing

Chatterjee, S., Nallari, A., & Dutta, C. Public Spaces for Children: A Compendium of Global Case Studies (p. 217). WHO, UNICEF, UN-Habitat. Forthcoming.

Tehlova, A. (2019). Changing Faces Competition. Mobilizing Citizens to Reclaim Public Spaces in Nairobi, The Journal of Public Space, 4(3), 61-86, DOI 10.32891/jps.v4i3.1221

Woolley H (2021) Beyond the Fence: Constructed and Found spaces for children’s outdoor play in natural and humaninduced disaster contexts – Lessons from north-east Japan, and Za’atari refugee camp in Jordan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 56: 102155. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102155.

Continued on Page 43

JUNE 2023 13

After

Before

Reimagining Schoolyards to Improve Health and Learning

A schoolyard in Concord, Calif. More than 4.2 million of the students in California public schools are on campuses with less than 10 percent tree canopy, half with less than 5 percent.

–Sharon Danks

–Sharon Danks

A heat map from September 6, 2022, showing many areas with temperatures between 104 an 110 degrees F. Record temperatures were a feature of the fifth-warmest September on record. –NASA

by Carl Smith

by Carl Smith

On an 81 degree day last September, environmental city planner Sharon Danks went onto the playground at a California elementary school with an infrared camera. Grassy areas in full sun measured 83 degrees, but unshaded asphalt was 107 and rubber surfaces under an exposed play structure came in at 135. Asphalt shaded by tree canopy was more than 30 degrees cooler.

Danks, the author of Asphalt to Ecosystems, a book published more than a decade ago to guide the transformation of schoolyards, wasn’t surprised at what she found. She and her colleagues had made similar measurements many times over.

But shade itself had gained heat that September with the announcement that $150 million had been set aside in the California state budget for a two-year program to fund school forests and green schoolyards at K-12 schools. The decision was driven by the need to protect the health of students as average temperatures in the state continue to rise.

The September 2022 heat wave in the West was the worst on record; temperatures soared above 110 degrees in multiple cities in California. In announcing the funding for schoolyards, Wade Crowfoot, secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency, noted that average temperatures across the state were projected to rise 6 degrees by mid-century.

As bad as things might look for Californians, warming trends are projected to be even more dramatic in other parts of the country. According to a peer-reviewed model published last year, by 2053 more than 100 million Americans will live in an “extreme heat belt” extending from Northern Texas and Louisiana borders to Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin, with temperatures exceeding 125 degrees.

Most of the daylight hours that children spend outside are on school grounds. The simple act of planting trees on campuses is a powerful way to shield them from heat-related health problems.

“Twenty-two percent of the population of California is under

18,” Danks observes. “I’m not saying they need 22 percent of the budget for climate mitigation, but a substantial portion needs to go to those who are too young to vote to make sure they are protected from the effects.”

A Network of Forest Makers

Last summer, the nonprofit that Danks founded, Green Schoolyards America, announced the launch of the California Schoolyard Forest SystemSM, a partnership with the California Department of Education, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) and Ten Strands, a nonprofit devoted to improving environmental literacy.

During the pandemic, Ten Strands and Green Schoolyards helped develop a National COVID-19 Outdoor Learning Initiative to build a community of practice around outdoor learning and to create an extensive learning library encompassing case histories, design ideas, curriculum, policy and funding guidance and more.

The schoolyard forest work will be a multi-decade effort, Danks says, and will have its own community of practice and online library. It got off the ground with a state grant to evaluate the need on campuses and the best strategies to move things forward.

Preliminary research suggests that more than 4.2 million of the students in California public schools are on campuses with less than 10 percent tree canopy. More than half of the campuses have less than five percent canopy coverage.

“The question we’re asking is how do you get 10,000 schools on 8,600 campuses with 6 million children to have shade,” Danks says. The immediate goal is to plant enough trees by 2030 to cover at least 30 percent of the areas of school property that children use during the day.

California will be the first state in a National Schoolyard Forest SystemSM. Green Schoolyards America will use the coalitionbuilding experience from the COVID-19 initiative to seed a network of forest makers throughout the country.

Shade and Health

Children are more susceptible to heat-related illnesses than adults. Their bodies don’t produce sweat as rapidly, and because water is a larger percentage of their body weight, they are more prone to dehydration. Younger children are less likely to recognize that they need to remove clothing or hydrate.

JUNE 2023 15

Hardscaped schoolyards present health risks in a warming world. A school forest initiative in California reflects a potential national trend to change the character and function of outdoor spaces.

According to research by the U.S. Forest Service, increasing urban tree cover by even 10 percent can have a significant impact on heat-related mortality. California school campuses have much lower tree canopy than the communities that surround them, says Walter Passmore, the California state urban forester. As a result, students can be exposed to both extreme heat and pollution.

Passmore works for CAL FIRE, which is administering the $150 million grant program. Application guidelines were released this month. The bulk of the funding, $117 million, will be awarded in the first year. Passmore expects about half of the grants to be planning grants and half to be grants for project implementation; funds come with a 75/25 matching requirement.

Schools in disadvantaged communities will be grant priorities. It’s not unusual for applicants from these sectors to lack the resources to put a competitive proposal together. The CAL FIRE finance department has provided funding for timelimited staff to help guide schools through the process of compiling a proposal that meets its guidelines.

The idea, Passmore says, is for those who submit planning grants to engage with parents, teachers, adjacent communities and design professionals in preparing their proposals. “That way, they have a project that is ready for implementation if funding becomes available.”

California has 10,000 K-12 campuses, and Passmore expects CAL FIRE’s $150 million will be enough for 50 planning grants and 50 implementation grants. “We’re not getting there with grants alone,” he says. “Grants will start the process, and we hope that a lot of our partners are going to be as excited about this initiative as we are.”

There are already signs it’s happening. In September the board of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the second-largest in the nation, passed a resolution adopting a standard with a minimum of 30 percent green space on campuses, directing the superintendent to find funding that will make it possible to achieve this goal by 2035.

The Berkeley Unified School District is the first in the U.S. to use a planting method developed to create dense, fast-growing forests in spaces as small as 30 square feet.

The Miyawaki Method

The school forest on the campus of Washington Elementary School in Berkeley, Calif., planted by children in the 1970s, is believed to be the oldest of its kind. It was the work of landscape architect Robin Moore, whose Washington Environmental Yard involved tearing out asphalt to make room not just for woods, but for meadows, streams and fishing ponds.

Fifteen years later, the district reclaimed about half of that space for blacktop, says Stephen Collins, manager of buildings, grounds and sustainability for the Berkeley Unified School District. About a third of the original forest remains, populated by redwoods, oaks and other species.

Surprisingly, not everyone in the district is aware of the existence of the forest and its role in outdoor play and teaching at the school. Visitors leave inspired, wanting to replicate what they have seen in some way, says Sofia Peltz, the district’s sustainability program coordinator.

One of the science teachers in the district introduced Collins and Peltz to the Miyawaki method of urban forest planting, an approach that combines dense planting and high biodiver-

A forest planted by children in the 1970s on the campus of Washington Elementary School in Berkeley, Calif., is believed to the oldest of its kind. –Sharon Danks

Thermal images reveal significant heat retention in hardscaped surfaces even on a relatively mild day. –Green Schoolyards America

sity in spaces as small as 30 square feet. According to the nonprofit SUGi, which plants these pocket forests in communities around the world, Miyawaki forests grow 10 times faster and are 100 times more biodiverse.

The Miyawaki approach is well suited to foresting at Berkeley schools, which are on small sites in tightly packed urban neighborhoods. Four have been planted in the district already, Collins says.

Pushback from facility managers who say they don’t have staff to maintain newly planted trees is not uncommon. At some schools, parents have stepped up to help with green schoolyards, strengthening the school community.

Collins and Danks both stress that if a tree is well cared for in its first few years, it is largely maintenance-free from that point forward. “One of the solutions we’ve talked about is when you apply for the grant for these kinds of projects, you include the first three years of maintenance by the contractor,” says Collins.

A controlled study conducted on elementary school campuses of the Los Angeles Unified School District found that the introduction of green spaces on school grounds was associated with more moderate to vigorous physical activity during recess and lunch periods. The increase was especially notable among girls, who are less likely to be drawn to competitive activities offered on hardscaped surfaces.

Golestan Education

Golestan Education

elementary schools with lower-income student populations.

The schools were in similar neighborhoods, with similar demographics. But one had an asphalt schoolyard and the other, LAUSD’s Eagle Rock Elementary, had a newly renovated green schoolyard.

Raney was particularly interested in finding out whether outdoor spaces had benefits for younger school children. Students tend to establish lifetime physical activity behaviors by about the fourth grade, she says. “If we don’t make sure that they have an opportunity to engage in physical activity that they find fulfilling and fun, they’re probably going to end up being sedentary adults with increased risk for chronic disease.”

The findings were striking. The introduction of a schoolyard forest was associated with more moderate to vigorous physical activity during recess and lunch periods. Standing inactively against a building to hug its shade is detrimental to both cognitive development and brain function, Raney says.

“When we introduce trees, logs, stumps, nature, we see students engaging in creative, collaborative, moderate to vigorous physical activity play,” says Raney. Moreover, she found, the gap between the physical activity levels of boys and girls decreases. Girls likely to be intimidated by, or not interested in, ball games or competitive sports on asphalt surfaces were seen balancing on or hopping between stumps, rocks or other features in outdoor classrooms.

Social and Behavioral Benefits

Marci Raney’s research focuses on health and well-being in urban environments, specifically low-income neighborhoods. From her position as a member of the kinesiology faculty at Occidental College in Los Angeles, she conducted a long-term observational study of differences in recess behavior at two

Anti-social behavior was less frequent in the schoolyard in which green features were interspersed with asphalt areas. “The amount of bullying that happens in these asphalt schoolyards from boredom is quite phenomenal,” Raney says. Pro-social verbal and physical behavior became more common in outdoor

JUNE 2023 17

June 2017: An outdoor classroom at Eagle Rock Elementary School just after hardscape removal and planting.

–Sharon Danks

January 2023: A second view of the outdoor classroom, now a refuge for students and teachers.

Before After

–Carl Smith

spaces with trees, stumps and plants, which present opportunities to work together to build things or solve tasks.

Benefits were observed immediately post-renovation (in 2016) and have been sustained since then. In subsequent work involving five Title I LAUSD elementary schools, Raney concluded that adding green space alone is not enough to achieve the greatest benefits from schoolyard renovation, highlighting the importance of incorporating unique, diverse and distinct play areas.

Raney left her faculty position at Occidental and is now serving as senior manager in the office of well-being at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. She’s bringing her experience to adults who care for children, hoping to incorporate rejuvenation spaces with views of nature and to optimize use of the hospital’s healing garden.

Changing a System

For more than a decade, Ten Strands has been helping develop environmental literacy standards and curriculum in California. The organization was founded by a science educator to support environment-based teaching and learning. School grounds weren’t a main feature of its work before it became a co-founder of the outdoor learning initiative, says Andra Yeghoian, chief innovation officer for Ten Strands.

As more and more teachers moved their classrooms outdoors as a last-resort measure to preserve in-person connection to their students, more and more realized there were good reasons to continue the practice. For Ten Strands, it prompted a deeper appreciation of the ways school grounds and buildings are part of the educational system it is working to transform, according to Yeghoian.

Using outdoor learning spaces to create unique opportunities for teaching about the environment is not a new idea, but California’s infusion of tens of millions of dollars to bring green features and trees to schools in disadvantaged communities is significant, as is the alignment of educational and public health missions in school forest projects.

“What this is really about is how we can be resilient enough to maintain our health and safety through climate change,” says Yeghoian.

There’s no reason environmental education can’t be effective in the absence of school ground features designed to support it. But if the current movement results in more opportunities to make lessons stick, that’s only to the good.

School, Yeghoian observes, is the only required cultural element in our society, the only chance to at least try to give every citizen analytical tools that help them keep their bearings in the face of environmental challenges.

Tipping Point

Sharon Danks has used design, research, teaching and writing to raise awareness of the ways green schoolyards can benefit students, teachers and communities for more than two decades. The combination of COVID-19 forcing education into the outdoors and a relentless series of climate and weather-induced disasters brought things to a tipping point, she says.

“The questions we’re getting from districts are no longer, ‘Why should we do this, but how do we do this?’”

Sharon Danks: “If we want children to be able to have PE outside in 20 or 40 years, they’ll need a place that’s shaded to do it.”

Los Angeles Unified School District green spaces on school grounds. associated with more moderate to vigorous physical activity. –Golestan Education

It may be safe for educators to return to their indoor spaces, but many resolved to double down, if not “triple down” on the things they gained from being outdoors with their students, Yeghoian says.

Access to green space is a component of health equity, and it’s not uncommon for schools to allow the public to use school grounds after school hours. According to analysis by American Forests, tree canopy is 25 percent less in communities where low-income residents are in the majority than in communities where the poor are in the minority. Passmore says that the CAL FIRE grant guidelines encourage joint use agreements.

Danks paints the situation simply. “If we want children to be able to have PE outside in 20 or 40 years, they’ll need a place that’s shaded to do it.”

Sharon Danks: “If we want children to be able to have PE outside in 20 or 40 years, they’ll need a place that’s shaded to do it.” info@greenschoolyards.org

–Paige Green Photography

This article originally appeared in Governing.com https://www.governing.com/community/reimaginingschoolyards-to-improve-health-and-learning

JUNE 2023 19

The Sense of Wonder

by Rachel Carson 1956

by Rachel Carson 1956

“A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood…”

“If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children, I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength.”

Photo: Steve McCurry

Photo: Steve McCurry

What Makes a Playground Great?

by Meghan Talarowski

by Meghan Talarowski

Play can happen anywhere, from your home, to your stoop, to your garden, or on your street, but when designing playgrounds, we often ask what makes a “great” space to play? As public space becomes an ever more finite resource, with pressures from urbanization, gentrification, and climate change, it is essential that we understand how to design play spaces so they support as many people as possible, as effectively as possible.

In recent years, playgrounds in the US have undergone a design renaissance. Significant investment, as well as experimentation in play features and site elements, have created ideal laboratories to explore what makes a “great” space to play. However, to date, there has been no research on the impact of these innovations on use, play behavior, and physical activity.

In 2019, our team of researchers and designers, from Kaiser Permanente, RAND Corporation, and Studio Ludo, received funding from the National Institutes of Health to embark on the National Study of Playgrounds. We chose 60 playgrounds in 10 major US cities, including Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, Memphis, New York, San Francisco, and Seattle, to study. Urban areas were selected as the playgrounds were larger, more plentiful, and had a wider diversity of play experiences to analyze. Half of the playgrounds chosen were considered to be “innovative” design and half were more “traditional” post and platform environments. Despite delays from the COVID-19 pandemic, in the summer of 2021 we collected data on over 33,000 users in the 60 playgrounds, which included demographics, physical activity levels, social interactions, length

Barbara Fish Daniel Nature Play Area, Houston, TX

All photos for this article: Studio Ludo

“The most important design feature in a playground is trees. Playgrounds with mature trees have two times more visitors than playgrounds with no trees.”

of stay, and location, using direct observation tools and trained data collectors.

After a year of analysis, we found that the design of playgrounds has a huge impact on use. Innovative playgrounds attract 2.5 times more users, generate almost 3 times more physical activity, and have 31% more users per square foot than traditional playgrounds. The innovative playgrounds in the study are almost twice as large as traditional playgrounds, and nearly half are in high traffic tourist locations. But even after controlling for size, population density, and tourist location, innovative playgrounds still attract 43% more visitors and physical activity than traditional playgrounds!

We now know that better designed playgrounds attract more people and encourage them to be more active. But what exactly is in the innovative environments that support this additional use? Is it certain types of play equipment? Is it benches, restrooms, good maintenance, or shade? It is even simpler than that. The most important design feature in a playground is trees. Playgrounds with mature trees have 2 times more visitors than playgrounds with no trees. Mature trees also increased the likelihood of longer playground stay time by 19%.

We also found that half of playground users (49%) are not children, but rather teens, adults, and seniors. This is a finding that we have seen in all of our studies. Between the National Study of Playgrounds (2019-2023), the New York City Study of Play Features and Value (2018), and the London Study of Playgrounds (2015), we have collected data on over 60,000

people in 100 different play environments in the US and UK, and consistently half of the users are over the age of 12. Despite perceptions that playgrounds are just for kids, they are clearly a public resource for all. However, they are not designed to support teens, adults, and seniors to be more physically active or to foster social connection.

When looked at as separate user groups, there are distinct preferences by age. Adults and seniors are most attracted to picnic tables, benches, berms, and boulders, all places where they can sit or perch, with clear lines of sight to children playing. Teens are found most on benches and swings, spaces where they can be social and connect with friends.

An essential finding was that adults are most physically active when playing with children and also with loose parts, from blocks and toys, to sticks and flowers, to site surfaces that invite interaction, like sand and wood chips. The play features they utilize the most together are swings, climbers, and spinners, particularly if they are larger scaled and more open-ended structures, to support adults to move and play with their children rather than stand on the sidelines. Water play is also a favorite of all ages to engage together.

Children are most attracted to opportunities that activate all eight of their senses. We know about our five senses. But what about the three “hidden” senses - proprioception, interoception, and vestibular? Proprioception is the sense of where our body is in space. Interoception is the sense of our internal organs and feeling of our emotions. Vestibular is the spatial

JUNE 2023 23

Levy Park Playground, Houston, TX

Shelby Farms Woodland Discovery Playground, Memphis, TN

awareness of movement and how we balance. Children are literally hard wired to swing, spin, and flip upside down. It helps develop their inner ear, sense of balance, and sense of self. Some of us grow out of the compulsion to spin, but everyone is attracted to swinging. Linear motion is calming to the vestibular system, helping to lower stress and increase endorphins. In our study, we found that for every swing, there is 6% more use and an 8% increase in stay time. Considering that some playgrounds have up to 12 swings and the average was 6, this is a potential increase in use of 72% and almost double the stay time, from 34 minutes in innovative playgrounds and 31 minutes in traditional playgrounds, to more than an hour on average. Swings are the perfect way to meet recommended physical activity levels of 60 minutes per day for children and 150 minutes per week for adults.

People, regardless of age, are attracted to similar play experiences that activate their vestibular and proprioceptive systems. Swings are the most used, but climbing, particularly larger scaled, flexible climbers that invite older users and provide dynamic physical and social interactions with others, add 4% more visitors and 6% longer stay time for each additional climbing structure.

Spinning is hugely popular and encourages up to 31% more stay time for each additional spinner. When looked at as a family of high-speed elements, spinners, ziplines, and very tall slides (greater than 6’) contribute to 18% more users for each added feature. Additionally, people like to change their perspective and get off the ground. Playgrounds with tall towers (greater

than 6’) have 17% more users for each additional, and berms, from small bumps to giant embankments than encourage scrambling and sliding, add 9% more users for each additional. And for the ultimate in full body sensory experiences, water play, from ponds, to streams, to splash pads, to manipulative pumps and dams, increase physical activity for kids by 80%!

We now know what visitors are looking for from a play perspective, but are there other features that encourage use? Playground design is so focused on the play of children that we forget about their bladders. Or their stomachs. Or their tired feet. One of the worst things a grownup can hear when they enter a playground is a small voice saying “I have to pee”. Playgrounds with nearby restrooms have 44% more users and increase the likelihood of staying longer by 48%. Areas that support eating saw 9% increase in use for each additional table.

Caregivers need places to sit or perch, with clear lines of sight to play areas. Backs and arms are essential for those less physically able, with adjacent spaces for wheelchairs, mobility devices, and strollers. Perches such as boulders, logs, or leaning bars help adults get closer to the play, fostering social interaction. Breastfeeding parents often prefer more secluded spaces to sit within sight of the play, and children benefit from these areas as well, during times they are overstimulated or emotionally overwhelmed.

Setting the stage for play requires more than just choosing equipment. It means understanding the needs of all users, from the youngest to the oldest. Including supportive site features ensures people feel welcome to stay and play for as long as they want to (not for when their bladder tells them its time to go).

24 PLAYRIGHTS • IPAWORLD.ORG

Rainbow Lake Playground, Memphis, TN

Smale Riverfront Park Adventure Playground, Cincinnati, OH

“People who live within a half-mile of a playground have a six-fold increase in walking or cycling than those that live further away.”

“Play is the one of the best investments in community health that we can make.”

Our single biggest finding was that compared to the impact of playground features and design, location is the most important determinant of use. Playgrounds located within a half-mile of residents increase use by five times and visitors are four times more likely to visit more than once a week. Additionally, people who live within a half-mile of a playground have a six-fold increase in walking or cycling than those that live further away.

Destination playgrounds in high tourist areas are more frequently visited via car, while local playgrounds are visited most by active transport. Users that walk or bike visit more often, although their visits are shorter than those going by car, possibly due to their closer location and convenience factor of repeat visits.

Choosing where to build and invest in playgrounds is crucial to public health. We found that for every additional 10,000 people in the half-mile radius of a playground, there are 60% more visitors and 47.7% more physical activity. Currently only 20% of homes in the US are located within a half-mile of a park. City planners, urban designers, and parks departments should consider the importance of playground locations, as well as active transport networks, safe sidewalks, and bike lanes when creating new or reconfiguring existing neighborhoods. Siting playgrounds within one-quarter to one-half mile of every resident should be a goal for all major cities. Children do not get to choose where they grow up. Everyone deserves access to a great place to play, and a healthy, active childhood.

Our study shows that everyone, regardless of age, loves to play, and they are most active and socially engaged when playing with others. People like to visit spaces that feel good to them, where they are welcome and cared for. Well-designed spaces

attract the most people, but building playgrounds close to home encourages repeat visits and active transport, like walking or cycling.

Why is creating better designed public playgrounds close to home so important? Because play is the one of the best investments in community health that we can make. Our studies show that playgrounds serve more people of all ages, abilities, genders, and demographics than almost any other public space amenity. Play gets people to move more, connect more, and spend more time outdoors, laying the foundation for a lifetime of health and happiness for all.

And building more playgrounds within a half mile of residents, particularly in cities, can positively impact climate change. Urban areas currently account for 70% of human carbon dioxide emissions. A recent study in New York City, the United States number one emitter, and third largest in the world, found that local green space offsets up to 40% of the city’s total emissions, absorbing all those produced by cars, trucks, and buses.

Our checklist for a great place to play, that is also great for the environment:

• Is close to home (within ½ mile)

• Is filled with trees and surrounded by plants

• Has supports, like restrooms, picnic tables, and benches

• Has opportunities for physical play, like swings, climbers, and great heights

• Has moments for sensory play, at high speeds, with water, and with loose parts

• Is designed for the comfort and enjoyment of all ages!

Continued on Page 43

JUNE 2023 25

Shelby Farms Woodland Discovery Playground, Memphis, TN

Pier Six Playground, New York City, NY

“Local green space offsets up to 40% of the city’s total emissions”

Nature vs. Anything: Playing with Materials

by Michael Laris

by Michael Laris

In the dialogue and debate concerning which materials are best suited to use in a playground, I have found in my 25 years of designing for play, like with most issues, there is a spectrum of opinions. To the one end, I’ve met the position, “Nature alone is best”. On the other end, “Anything is good as long as it’s safe”. Most people seem to fall somewhere between the end points on this Nature vs. Anything material spectrum. At any rate, I am ‘somewhere in between’ and in this article I will share my viewpoint concerning which materials I suggest be used for a play space, what questions one might ask of the company supplying these materials, and how I came to my thinking on this issue. There are three life experiences that have formed my viewpoint on this subject: my own childhood, my education and work experience, and witnessing my own and many other children at play.

I grew up in a town that is wedged between the Pacific Ocean and the Coastal Mountains of California. My family lived out of town, up the hill, at the edge of Los Padres National Forest. My local ‘playground’ was either acres of chaparral, oak trees, and sandstone boulders, or miles of beach, tide pools, and driftwood. This was all my best friend Kevin, my dog Curly, and I needed. We didn’t know how fortunate we were. That said, there are several valuable interactions that these environments did not allow for, at least not very safely.

For example, the only ‘slide’ we had was a great load of gravel that had been dumped off the side of a mountain road. It was great going down but took us an hour and brutal encounters with poison oak to get back up. The only swings we had were at our nursery school. They were always occupied but when it was our turn, we loved swinging high enough to see the big cat on the other side of the fence. Otherwise, sliding, swinging, and also spinning, were not really available in our mountain and beach playgrounds.

These activities: sliding, swinging, and spinning are fantastic experiences for children. Joyful and engaging, these activities help to further develop a child’s sense of balance, depth of vision, proprioception, and movement planning, as well as helping to form the understanding of momentum, displacement of mass, and centrifugal force. Children might not understand these forces, but they feel them and learn to work with them.

Growing up like this, you might think that once I became a designer of play that I would be far over on the Nature side of Nature vs. Anything. However, when I left the mountains and shoreline to attend architectural school, I was exposed to a larger world of materials and the processes of designing buildings and creating environments with them.

My architectural education at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo was all about Learning By Doing and the doing is all about transforming materials. In my mind, Architecture is a collection of materials of different qualities, strengths, elasticities, textures, shapes, and sizes put together to create a new space, at a specific location, to be experienced with one’s whole body in time and space. (Like a playground by the way.) Architecture shapes space, allows light, manages sound, provides shelter, builds intrigue, shares surprise, delights and expresses beauty. I thought I was headed in the direction of architecture, of designing buildings for people, and honestly, I thought of people as adult people. However, life twists and turns and the buildings I would end up designing were for children rather than adults.

In the early 90ies I moved to Denmark and couldn’t find work as an architect. Eventually I landed a job with one of the world’s most influential play equipment companies and I was transformed into an Architect of Play. What a wonderful twist of fate that was. In this environment I began thinking more and more about my own childhood play experiences. I visited many play spaces throughout Europe and North America and in doing so, I saw many ‘nature playgrounds’. I met people who claimed these playgrounds made the best solutions as they were more natural.

JUNE 2023 27

In my eyes, these spaces were nothing like a natural environment, at least nothing like what I grew up playing in. In trying to recreate nature, what was created was not ‘natural’ at all. It was perhaps a managed forest-like area, a large well planted park, a play structure built of wood, or even some up turned trees. But this did not make these spaces more ‘natural’ in my mind. They were still human created environments with human constructed playarchitecture in them. So, even though I grew up playing in nature, I was not settled as to where I was on the Nature vs. Anything material spectrum.

The Danish company I was working for was founded by an artist who brought together color, sculpture, and play value in his works of beauty and function. When I began designing play sculptures in 1997, many materials were used – wood, steel, plastics, fiberglass, rubber, concrete. The company promoted, “Wood is Good” and the play designers I learned from didn’t favor large amounts of plastic. The plastic we saw in play spaces was often large, poorly formed, lumps of bright colors. Colors that faded. We worked with some wood and steel for structural parts, beautifully painted plywood for walls and roofs, and rope for climbing. When no

other material would suffice, we used high quality plastic for fine details.

But as the years passed, I began to think more about these materials. The wooden posts were timber, processed, cut smooth, and treated. The steel was painted or galvanized. And the plywood was made of very special layers of veneer and glue, and then painted with a thick coat to resist wear. Wasn’t the paint basically plastic? Could you really say that the plywood was wood? Was it more natural than plastic? Where did these veneer layers come from? How were they produced? How much waste was there? How environmentally friendly was the glue?

During this time, wood was heavily scrutinized. The chemical process used at the time for treating wood was criticized. There were also complaints about maintenance issues, and others were concerned about the grave danger of splinters (I was told that an ambulance was called once because the playground supervisor didn’t dare remove a splinter in fear of liability – urban myth?) True or not, at that time, wood was almost eradicated from the playground. Fiberglass was also removed. And most of the time, concrete was thought to be too harsh, heavy, and brutal.

Eventually, complaints about wear of the plywood led the company to switch from making walls and roofs out of plywood to using sheets of plastic instead. Wood had been Good, now Plastic became Fantastic. I was thinking, “next is Concrete can’t be Beat”. At first, we designers did not take this well. But after some time, we discovered new benefits the material offered, attributes that we could utilize to create new play experiences. I could see that each material has its good points and bad. Could one really say that a certain material was somehow better for children? I had many questions and one in particular was, “why must a human-made space

28 PLAYRIGHTS • IPAWORLD.ORG

for children be limited to using ‘natural’ materials when it’s not a naturally made space? And, on the flip side, why must it be made entirely of plastic and steel just because it is thought to be the easiest to mass produce and maintain? (Side note: people expect play equipment to last and not age for over 20 years in all weather conditions, heavy use, and no maintenance. What other product is expected to live up to these expectations?)

After 20 years in Denmark, I returned to the US and joined another play equipment manufacturer. It was not visible to me at first, but soon I learned how much time, effort, and money this company had invested to understand its material use and its ‘greenness’. This was in 2012 and the company had already taken extraordinary steps to change the way it looked at everything it did. They had worked with the foremost authority in sustainable thinking to obtain a total overview of the company’s carbon footprint from as far out in the supply chain as possible.

The 3rd party’s evaluation considered the processing of raw materials, the shipping required, and the energy to produce standard materials like pipe steel and sheet plastic. Also included was the shipping of these materials to the play equipment manufacturing site, all energy used at this site, shipping of the finished play product to its final location, installation and maintenance needs, the cost to eventually recycle or eliminate the product, and more. It identified types of materials and processes that were deemed too unsustainable or unhealthy to produce, and any such material was removed from the company’s assortment and ‘greener’ substitutions were developed. The company received the second highest status for sustainability, Silver. No other companies that I am aware of have gone through this kind of rigorous process and have achieved such a high level of sustainability from an

internationally recognized 3rd party. Being involved in this process made me aware of a much larger picture, and a bigger question. Is it less about whether wood or plastic is better for children and more about which materials, with their processing and shipping needs included, are more sustainable, and better for the earth that our children will experience? Thinking about that question, let’s take a look at wood. I think most of us have a good feeling about wood and consider it a natural, sustainable, living material, that can be replenished. However, perhaps equally important is to understand where it comes from, how it is harvested, how it is replenished, how and how far is it transported, how is it processed to become a workable material for play? Basically, what does it take to get it from the forest to the playground, how long does it last, and then how is it disposed of?

Answering these questions for any material can be complex and daunting. For example, tons of sheets of ¾” plastic are used in play equipment. Most of these

specific shapes for the walls and roofs of play equipment.

Question: in order to do this, is the material shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe? Then once cut, is it shipped back to the US to a playground site? A site in the same town as where it was extruded, or where the raw material was processed? That might sound crazy, but this can be the same situation for steel or even wood. We know the heavy burden shipping brings to our environment. Can we avoid all this shipping? What is the total carbon foot impact to get the raw material processed, manufactured, and delivered to the final playground?

And there is more to consider: what happens once the play equipment is loved to death and no longer functions? Aside from how materials are made, processed, and shipped, it is important to understand if and how they can be recycled. Can the materials be re-used for something else? Can they be recycled as they are? What is the likelihood of this? Do they contain hazardous chemicals? Are parts made of different types of materials that have been molded together, like aluminum and rubber? Can they be easily separated from each other? If not, most likely, they will not be recycled.

Considering all this can be overwhelming to a designer and anyone choosing materials to make a play space. So, are we back to using only natural materials like rocks and fallen trees?

sheets are manufactured in the US. The making of sheet plastic starts with a petroleum-based raw material that is processed and made into plastic beads. The beads are then shipped across the US where they are extruded into flat wide sheets. Then the plastic sheets are shipped to a manufacturer so they can be cut into

The third set of meaningful experiences that have shaped my viewpoint on this subject comes from all the time I have spent observing children at play, both my own three, and so many others. I have been very fortunate to have had the opportunity to travel to many countries, across five continents, to specifically learn from children. This has been the most rewarding part of my work, seeing my

JUNE 2023 29

own and many other children at play: seeing what they look for, what they do, what they need, desire, get by with, and make use of. How they investigate, interact with things, challenge themselves, manage risk.

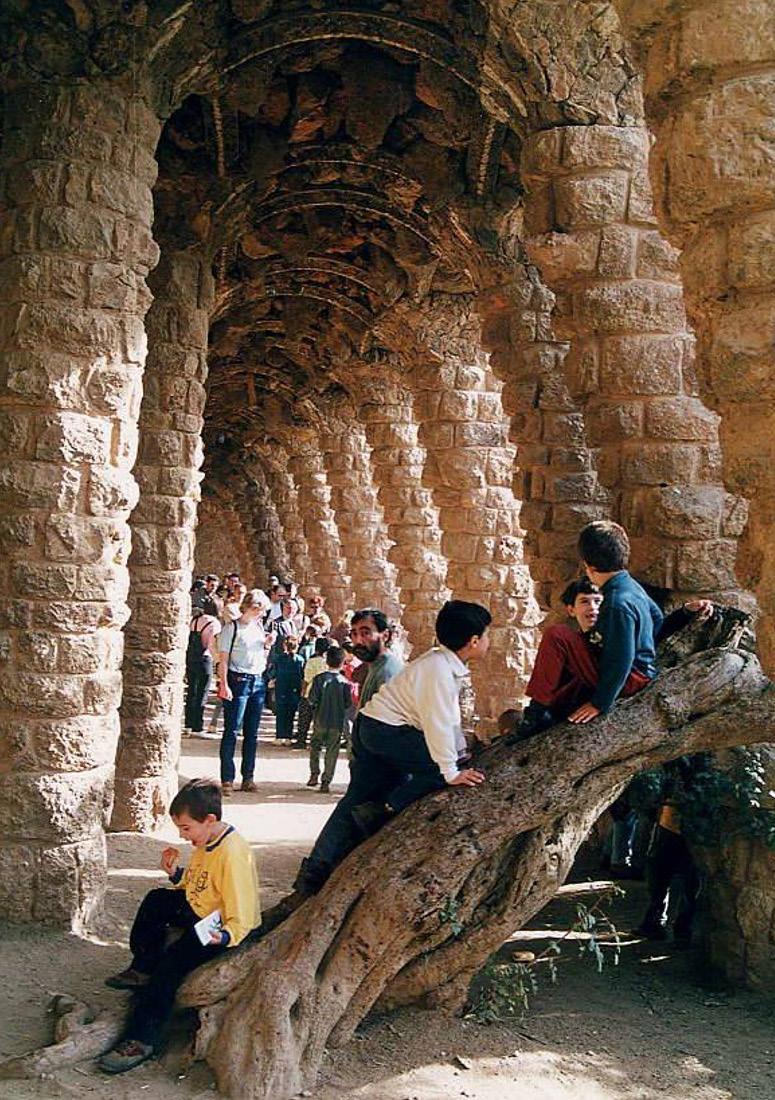

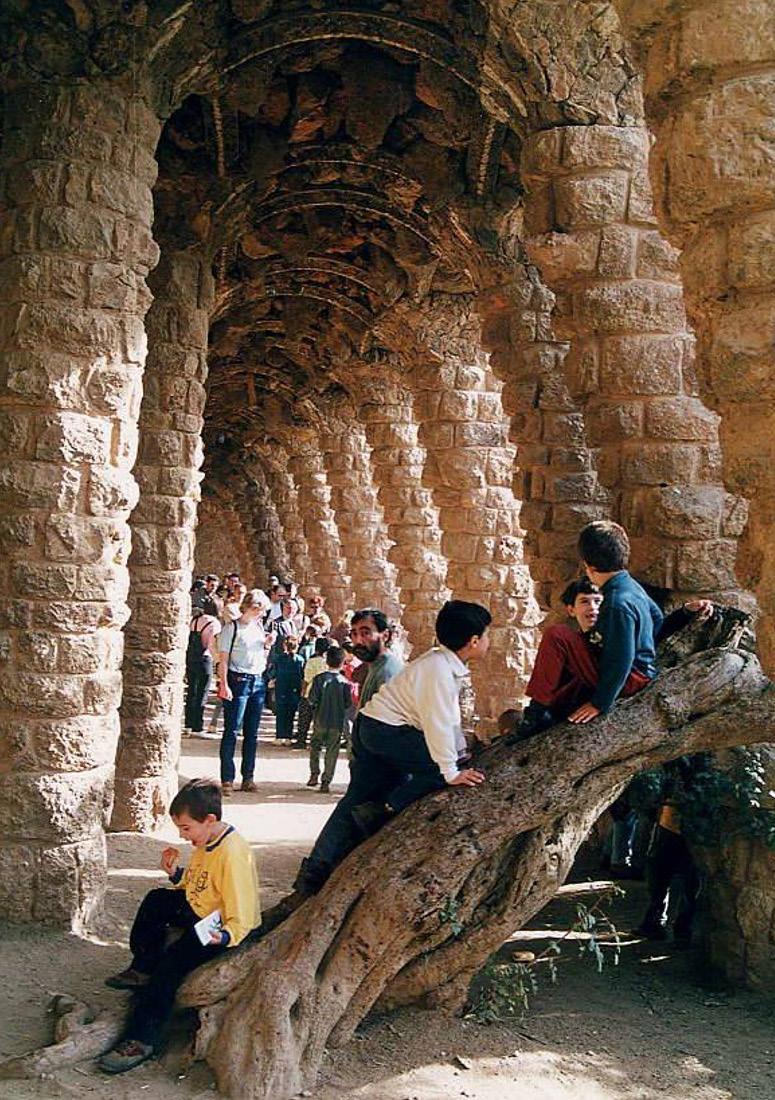

Once in Barcelona, I saw a group of eightyear-olds visiting Parc Guell. What they seemed to enjoy most was an old, sloped, curving tree trunk that they could climb, sit up on, and slide down.

(See opening photo.) It was a great piece of playground “equipment.” The challenge was good, the play enjoyable, the function diverse. However, it’s not possible for children everywhere to access such a tree. On the other hand, the most enjoyable features of such a tree could be replicated in a manufactured product. And in addition, other features and details could be added, like a section that is easier to grip for a small hand, or an area made smoother for sliding, or flatter for sitting. And the best material for this fantastic thing might just be plastic. That thing was made, and it has challenged and been enjoyed by 1,000s of children in many places where they don’t have access to wilderness, nature, or an open park. This piece of play equipment, though plastic, has brought about a tremendous amount of joy and growth.

An amazing thing about children is that they all find ways to challenge themselves and grow. A hill, a tree, some rocks, some sticks, and they can do just about anything, create any narrative, and activate all senses and parts of the body they can, and in extraordinary ways. They don’t need a themed playground to free their imagi-