JOURNAL Issue 78 — Winter 2021 For Nature

internationaltreefoundation.org

International Tree Foundation works every day to plant and grow trees, restore and conserve forests and strengthen community and ecosystem resilience.

© International Tree Foundation 2021 Charity number 1106269

The Old Music Hall, 106-108 Cowley Road, Oxford. OX4 1JE, United Kingdom

Artwork: Jim Whitty – jimwhitty.com | @jimwhitty_artist

Design: Kate Lehane – katelehane.com Ben Cave – bencavedesign.com

This journal has been printed on 100% recycled material at a factory powered by 100% renewable energy, using zero water or chemicals and generating no waste to landfill, Seacourt is a Net Positive printer that makes a positive contribution to the environment and society.

1 CONTENTS FORWARD FROM HRH PRINCE OF WALES 2 AN INTRODUCTION FROM THE INTERNATIONAL TREE FOUNDATION 4 NATURAL WORLD 5 WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE? 6 IN THE COMPANY OF THE FOREST 10 UNSUNG HEROES 12 ST. BARBE’S PRESCIENT LEGACY 13 HEDGEROW TREES 15 THE PRAYER OF THE TREE 18 THE BUSINESS OF RESTORATION 19 ENSURING THE SURVIVAL OF THREATENED TREES IN KENYA 20 TREES THAT EMPOWER 22 BAKER COLLECTION AT UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN 24

[Type here]

It is nearly a hundred years after Richard St. Barbe Baker, serving as a young forestry officer in Kenya, worked with the local Kikuyu clan to found ‘Watu Wa Miti’ (Men of the Trees). He correctly observed that the removal of trees without sufficient reforestation can have devastating consequences.

Forests are, of course, amongst the richest biological resources on Earth; tropical or temperate, they offer a magnificent variety of habitats for plants, animals and micro-organisms. Yet, nearly a century after St. Barbe’s salient observation, deforestation is one of the greatest challenges faced by humanity today. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization has estimated that about 13 million hectares of the world’s forests are lost due to deforestation each year. Despite growing awareness and appreciation of forests as a carbon sink, the loss of the world’s natural forests has accelerated in recent years, with disastrous consequences for climate change, rural communities and global biodiversity.

Despite these distressing figures, the International Tree Foundation (I.T.F.) has worked tirelessly, supporting small scale forest restoration projects in the United Kingdom and Africa, planting many millions of trees and growing into a global organization. Its programmes now support a wide range of community-based organizations which are working with local people to ensure community-led, grassroots projects that engage in forest restoration, agroforestry, livelihood diversification, regenerative farming, food sovereignty and water security, soil fertility management and local climate stabilisation, thereby making a direct difference to people’s lives.

As the world belatedly wakes up to the supreme urgency of the planetary crises we face, many in business and government are beginning to work together to promote sustainable supply chains, reducing the threat to natural forest ecosystems. However, we must remember it is not just about planting millions of trees. We must keep in mind that we need the right kinds of trees in the right places, mixed with agroforestry and with a long-term maintenance plan.

While the shift in business practices towards Circular Economy principles and, incr easingly, ‘Circular Bioeconomy Principles’, in recent years has been quite encouraging, there is so much more to be done. This is why I launched my Sustainable Markets Initiative in January 2020, and the ‘Terra Carta’ road-map earlier this year as a way of seizing what is now, I fear, a very narrow window of opportunity to mobilize the world to accelerate our transition to a sustainable future.

Over the past year, I have been convening global industry C.E.O.s across different industrial sectors, engaging with investors and speaking with world leaders to identify ways we can work together to accelerate our progress on climate change, biodiversity loss and a just transition. Within the tenpoint plan of my Terra Carta, investing in Nature as the true engi ne of our economy is of particular relevance to safeguarding and restoring the world’s forests. After all, Nature’s contribution to the global economy is estimated to be worth more than $125 trillion annually – greater than the entire world’s annual G.D.P., estimated at $87.79 trillion in 2019.

JOURNAL

TREES

2

Encouragingly, the One Planet Summit that I joined with President Macron in January saw the announcement of ‘The Great Green Wall Accelerator’, which is a revival of , and investment in, an idea originally developed and promoted by Richard St Barbe Baker and the I.T.F. At the Seventh World Forestry Charter Gathering in 1951, representatives of thirty-two nations signed up to the ‘Green Front Against the Desert’. The vision was to unite the world’s governments in a s ingle purpose – and a single project – to direct the world’s armies to plant millions of trees along the Southern Saharan border to stop desertification and restore millions of acres of agricultural and forest land, providing resources and food for millions of people. Today, this project is known as the Great Green Wall and is part of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. Progress has been achieved into the second decade of the initiative, with almost 18 million hectares of degraded lands restored and 350,000 jobs created across the Sahel and the twelve Great Green Wall countries.

In support of these efforts, my Circular Bioeconomy Alliance (C.B.A.) is working to accelerate investment in forest restoration agroforestry and regenerative agriculture on the ground. Such restoration projects could be implemented through a network of ‘T erra Carta Labs for Nature, People and Planet’ that aim to use a holistic approach to create resilient landscapes as a basis for sustainable products, markets, and livelihoods.

These Terra Carta Labs, which are being seeded in India, Nigeria and Ghana, d emonstrate how Harmony with Nature can be achieved by integrating traditional knowledge, capitalizing on new research and innovation and focu ssing on creating opportunities for local communities, especially young people and women.

Though the scale of new investment in the green economy gives me hope, it is the unsung heroes and heroines around the world who inspire me most, such as those who plant trees in the wind and rain on Dartmoor year after year; the community restoring Kenya’s Imenti forest; and the people teaching small-holder farmers how to embrace agroforestry to improve their farms’ productivity and build soil health. There are countless local examples of the changes we all need to make so that we can each, in our own way, become Nature’s stewards. Indeed, I am particularly pleased that my Charitable Fund enabled seventeen new community projects across Commonwealth nations in Sub -Saharan Africa in 2019 to start operations in 2020. Each and every project is an example of a community that has come to recognise, as we all must, that Nature is indeed the true engine of our local economy, our health, and of all our livelihoods.

As the I.T.F. approaches its centenary in 2022, the world is counting on your success.

FORWARD 3

AN INTRODUCTION FROM THE INTERNATIONAL TREE FOUNDATION

When it comes to tree planting, there is a phrase that many readers will have heard before, “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.” It may be a well-worn phrase but, in light of the increasing urgency of the climate crisis and planetary destruction, it is a phrase that bears repetition. Some people are only now waking up to the centrality of trees to life on earth and the need for us to play an active role in planting them, tending them and protecting them. For others it has been a lifelong passion.

When Richard St Barbe Baker and Chief Josiah Njonjo founded what was to become the International Tree Foundation nearly 100 years ago, they believed deeply in the importance of trees to sustaining life on earth. They were ahead of their time in perceiving that reforestation efforts should be led by local communities across the world. Now those founding ideas and actions are more important than ever.

When the global climate summit, COP26, took place in Glasgow, we witnessed a growing consensus from world leaders, environmentalists, businesses and charities, including the International Tree Foundation, about the need for a reforested future. A future that will help restore our delicate planetary balance and support vulnerable communities. One thing was

very clear from the conference, there is still a long way to go. We need to build a stronger movement of people – young and old alike – who love trees, who understand their value and who are determined to live in a world that is greener and fairer. In this issue of the Trees Journal we hear from some of those people; Hugh Locke celebrates Richard St Barbe Baker’s lasting legacy and its relevance for today while Jonathan Drori asks where we can go from here. Sam Pearce celebrates the resurgence of the hedge and Tabitha Njoki Githinji writes about the Wamiti women’s group in Kenya and her childhood love of trees.

At the International Tree Foundation, we are part of a global community, a movement, that is passionate about trees and all the beauty and benefits they bring to life on earth and to sustaining communities across the world – from the women running tree nurseries in Kenya to the school groups that planted trees with us in Glasgow. We want to celebrate and acknowledge everyone who plays a role, however small, in this restoration movement to secure the future of our planet.

James Whitehead is CEO at the International Tree Foundation

TREES JOURNAL

4

Part 1 NATURAL WORLD

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

One of my earliest memories is of a spectacular Cedar of Lebanon, near our home in southwest London. One winter morning, we found it dead, struck by lightning. Its huge trunk and limbs were strewn haphazardly and being sawn up. That was the first time I saw my father cry. I thought about the huge, heavy tree that was hundreds of years old that I had thought was invincible, and wasn’t, and my father who I had thought would always be in benign control of everything, and wasn’t.

How can we humans migrate urgently to a lowerconsumption, lower-carbon world, while remaining happy and fulfilled?

I remember my mother saying that there had been a whole world in that tree. As a child, I puzzled over that, only realising much later that the loss of a single cedar represented something far bigger.

Trees and other plants, fungi, animals and every little insect depend on each other in complex webs of life that are diverse and astounding. But, as in the parlour game where players take turns to remove components of a tower until it finally teeters and falls, as individual species are threatened, our ecosystems become less resilient; until, unseen, they are so fragile

that one extra nudge can make a whole system collapse. Our futures depend on these ecosystems and the relationships between them.

Although I profoundly disagree with people who see themselves separate from and superior to nature, I can understand their dangerous point of view. After all, to thrive, humankind has depended on nature but also needed to control it. Remnants of our need to bend nature to our will are seen in the illogical desire for ‘neat and tidy’ roadside verges devoid of flowers and life, and the green deserts we cultivate as lawns. But surely, all but the most short-sighted person, perhaps the city-dweller divorced from all that is natural, or those who are blinded by short-term greed, can understand that the balance now needs urgently to be redressed? Biodiversity is being obliterated by rampant over-consumption, by myopic agricultural practices and by climate change. They are all related.

The way we grow our food has a colossal effect on the wider environment. We use gargantuan quantities of fossil fuels in the production of fertilizer, yet we feed the lion’s share of our vast, forest-gobbling harvest of maize and soybean to billions upon billions of farmed animals, which we eventually eat. This is ludicrously and stupidly inefficient.

How much our species consumes and its effect on the environment are linked to our growing numbers, but also to the choices we make about the quantity

TREES JOURNAL

6

of goods we buy and how their materials are mined and produced, the energy that individuals or industries use, our modes of travel, the techniques we use for construction, and so on. Unfortunately, once the effects of climate change and biodiversity loss are painfully obvious to all, it will be too late to avert calamity. Given sufficient incentives, the adaptations we must make are within our grasp, and many of the solutions are either known or could be ingeniously developed. But those incentives require resolute governments that are willing to implement carbon taxes, subsidize new technologies and, if we continue to dither, probably ration some products and activities. We will need gutsy, far-sighted leaders, resistant to

the lobbying of those who stand to make short-term gain by obfuscating the issue; thoughtful decision-makers, with the grit to deliver messages that the public don’t want to hear, but with the charisma and mandate to be heeded.

If people feel they are making sacrifices that others are not, they will resist change. Each country, each community, each person, must believe that we’re all in this together, a coalition against a common climate enemy, rather than an unfair arrangement where some suffer and others blithely do business as usual, or a zero-sum game in which your win means my loss. Moving swiftly and decisively to a more sustainable, low-carbon world will be difficult. True, some business will

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

7

be curtailed, or fail altogether. But others will flourish in new niches, just as plants evolve with their habitats. Some fun will stop; other amusement will take its place. We should demand that our leaders, and our media, rather than being distracted by whether groups like Extinction Rebellion are a force for good, an irritation or worse, address the big question of our age: How can we humans migrate urgently to a lower-consumption, lower-carbon world, while remaining happy and fulfilled?

What do we need in order to be happy? ‘Developed’ nations might learn a great deal from indigenous knowledge and ways of life that celebrate the interconnectedness of communities and the land, rather than the acquisition of material wealth as an end in itself. When I immersed myself in plant science, history, culture and folklore for my book, Around the World in 80 Trees, I was struck by the contrast between the care and diligence and long-term outlook based on intimate local knowledge and expertise of those who live in and among the plants on which they depend, and those people (previously colonists, now in businesses) for whom plants are simply commodities to be traded. The need by companies or individuals for short-term profit has frequently been driven by insecurity in societies with inadequate safety-nets, as much as by greed.

The jarrah trees shipped from southwest Australia to make the sheds and rolling stock of Empire and even to pave London’s roads; the magnificent kauri forests of New Zealand laid low by an army of prospectors, first benignly collecting fallen resin, then blindly hacking trees to feed the varnish industry; the old growth forests of North America cleared for… Again and again, it was the same story; outsiders taking more than could possibly be

sustainable until the source was destroyed. And sadly today, the way that companies are valued by their profits and the speed of their growth and even the nonsensical drive for higher per-capita GDP of entire countries – optimising for short term profit at the expense of environmental sustainability – this is what most of the world’s present economic system is designed to do. It is only regulation that keeps this in check, regulation that is often ineffective or corrupted by bribery or lobbying.

As I write, Botanic Gardens Conservation International has just published its State of the World’s Trees report. Of the 60,000 or so tree species, about a third of them are at risk of extinction. We surely need leadership, of our companies and our governments and institutions that is both more environmentally aware, but also has genuine empathy for nature.

I know now that my father cried not only for one tree but for other losses that it represented, beyond even the natural world. He had fled to Britain in the late 1930s and mourned the loss of his entire family in Eastern Europe. As a child, I couldn’t decode my mother’s subtle metaphor of there being a whole world in that cedar. I thought she just meant the insects and birds. Those webs of life woven around our trees are vital of course, but I do wonder whether empathy for people and the empathy for nature which we so desperately need, might go hand in hand.

Prof. Jonathan Drori CBE is author of the bestseller Around the World in 80 Trees and Around the World in 80 Plants. He is a Trustee of The Eden Project, Cambridge University Botanic Garden, Ambassador for the WWF and Honorary Professor at the Institute of Forest Research at Birmingham University.

TREES JOURNAL

8

9

Where the Waters Meet, Jim Whitty

IN THE COMPANY OF THE FOREST

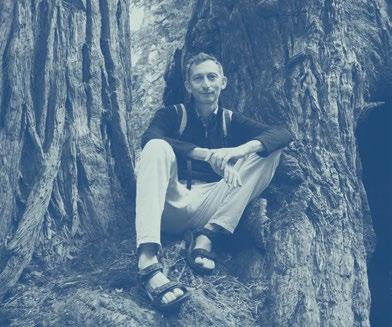

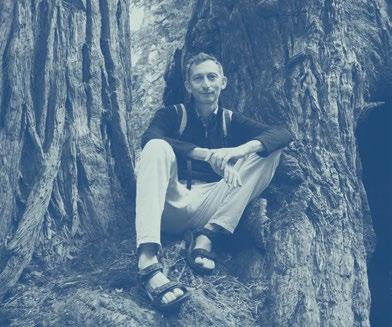

As I walk through my local forest parkland in the late-summer Northern California air, my eyes rest momentarily on trees I have seen many times on my rounds. Here, the fuzzy bark of redwoods mingles with the sturdy flush of live oak leaves, bay laurels sit heavy not too far from soaring newcomer blue gum eucalyptus, sharing space with pines, firs, and cypress. The forest is a busy place - buzzing, chirping, growing, swaying, popping. Much activity is happening both above and below ground. The trees, seemingly still in their places, are active in their crowns with the rustle of leaves. Entangled in the boughs are other plants, animals, insects, all going about their day, creating nests and homes, looking for breakfast before taking up a post in the canopy or in the hummus. Creatures are working in tandem within the forest to produce livelihoods. Synergies are created among the workforce of the forest, collaborations built, and competitions engaged.

The forest evades easy definition, and the English word comes from the Latin foresta, which either derives from a

term for exclusion or a term for a closed space. Forest, a legal term in old European languages, was distinguished from the earlier term wood. While the wood was a common place, royal families set aside forest areas for their own pleasure and recreation, and royal forests also served as a sanctuary for animals. The term forest has come to mean land that is at least in part covered by trees reaching into the sky, excluding agricultural or urban areas. The forest is an association of trees, plants, fungi, animals, and human beings. The day moves along with me through the forest. Stalwart trees are working heartily to organize our atmosphere, manage our carbon, and direct the flows of nutrients and water to keep our planetary systems moving. Trees store carbon in their bodies as they grow, sequestering it away. They change the light that filters to the ground and shift the local climate. An individual tree is moving water up and down the trunk and creating new cells both for the wood and bark from the cambium, a small layer of living cells. Stomata, tiny pores like mouths, on the

TREES JOURNAL

10

leaves are opening for the exchange of gasses as the tree turns sunlight into energy. The tree must also know when to pull back, cut losses, and minimize damage. There are a number of management problems a tree needs to address. What is the return from the leaves on this westerly branch? Maybe pivot to the southerly one instead this season. Is this a good year for acorns or seeds? What are the other trees doing for their succession planning? How many little ones are they fostering? Each

Thinking about trees as persons could dynamically shift the way humans interact with forests globally towards protection and restoration.

challenge requires a strategy in response to changing conditions in the forest. There exists a non-human or morethan-human world both obvious and at the edges of what I see and experience. Insects and birds flit through the air, laboring at their tasks for the day and occupied by their affairs unknown to me. Here on this well-trod path, larger animals are all but gone, though occasional footprints and scat are the handiwork of deer, coyotes, or mountain lions.

In the invisible underground, fungi are forming partnerships with tree roots in mycorrhizal networks throughout the forest. Communication moves between root and root, and nutrients make their way eventually from limb to limb. These alliances, discovered and researched by forest ecologist Suzanne Simard, connect tree to tree and are critical to arboreal and forest success.

Forests require human work as well. As those who know the most about the trees, indigenous and local peoples provide leadership in forest relationships. Human beings at our best in the forest can be supervisors, overseeing the flourishing of trees, plants, and animals and restoring the forest. Human beings at our worst in the forest can be unrelenting taskmasters, going so far as to fell every last tree for our own purposes. Protecting trees and the non-human beings that depend on them requires an engagement with the forest that goes beyond an investment only for human needs.

Corporations are considered legal persons in several countries, including in the United States since 1886, but non-human beings lack any such definition. Scholars and jurisdictions are reconsidering animals, rivers, lakes, and even nature as non-human persons. With research pointing towards arboreal intelligence, relationality, and agency, trees can also be considered for a type of vegetal personhood. Thinking about trees as persons could dynamically shift the way humans interact with forests globally towards protection and restoration. I have walked long in the hills, visiting redwoods, oaks, and bay laurels and observing their slow, imperceptible progress. They make their living in this parkland. I emerge into the clearing as I start on my way towards home. After a day of activity, the forest quiets while the evening creatures begin their shifts. Some of the trees are counting the night before awakening the next morning to return to the business of being in the forest.

Laura Pustarfi is a plant studies scholar and writer living in the San Francisco Bay Area in California, USA.

IN THE COMPANY OF THE FOREST

11

Part 2 UNSUNG HEROES

ST. BARBE’S PRESCIENT LEGACY

When the leaders of more than 100 countries gathered recently in Glasgow, their pledge to end deforestation by 2030 echoed Richard St. Barbe Baker’s vision of world forestry as the beating heart of a global enterprise to restore the earth.

The legacy of St. Barbe, as he was known to friends and colleagues, is more relevant now than ever. His life’s work is replete with remarkably prescient insights and practical examples that, while ending four decades ago, still read like the trouble shooting chapter in the owner’s manual for our planet.

The United Nations summit on climate change in Glasgow is a case in point. In 1943, St. Barbe held the first of what he called the World Forestry Charter Gatherings. Meeting regularly over 15 years, the London-based diplomatic representatives of as many as 45 governments from around the world came together to discuss the key role of forests in global ecology.

The World Forestry Charter Gathering in 1951 passed a resolution proclaiming a Green Front Against the Desert. Thus was born one of St. Barbe’s boldest initiatives. It began when he led the first ecological survey of the Sahara desert the following year. Then in early 1953 he announced plans to stop the desert’s southern spread and reclaim large portions by planting a belt of trees the breadth of the continent. While this concept found only sporadic support at the time, it anticipated the epic Great Green Wall movement

now underway to plant trees and restore landscapes along the southern edge of the Sahara and spanning the entire width of Africa.

St. Barbe was a lone voice for much of his life as he spoke of trees as being key for human survival. He described forests as, “a community of living things, the greatest of which is the tree.” Thought as quaint at the time, this idea is mainstream

ST. BARBE’S PRESCIENT LEGACY

13

now that science has confirmed forests are in fact home to most of earth’s terrestrial biodiversity.

St. Barbe was a lone voice for much of his life as he spoke of trees as being key for human survival.

To anyone who would listen, St. Barbe warned that if forest cover ever went below one-third of global land area, the earth would lose the capacity to heal itself from humanity’s destructive impact. Deforestation has brought us to the point where forests now cover just 31 percent of land on the planet, and indeed climate change has become an existential crisis. As the governments of the world

finally take up the rallying call of the first World Forestry Charter Gathering, may they also heed the example of St. Barbe and engage the full spectrum of human society in this undertaking. When he launched the Men of the Trees in 1922, now the International Tree Foundation, it was with Kikuyu farmers in Kenya. For the remainder of his life St. Barbe was able to enlist people from all walks of life and all corners of the globe to the cause of trees. This must also be the hallmark of one of the world’s greatest collective undertakings as we set out to save ourselves by saving our forests.

Hugh Locke was an assistant to Richard St. Barbe Baker for the last six years of his life, and was appointed by him as literary trustee for his estate. Hugh is President of the Smallholder Farmers Alliance in Haiti, and writes and lectures extensively on smallholders and agroforestry.

TREES JOURNAL

14

HEDGEROW TREES

The humble hedge is the face of much of Britain. Not surprising, when this small island boasts 500,000 miles of it. This makes the collective UK hedge our biggest nature reserve - it gives shelter to countless wildlife species while acting as a matrix of wildlife corridors across the country. However, its ubiquity has led to the hedge being overlooked and taken for granted, allowing for the decline of our heritage to happen almost unnoticed.

After decades of neglect, the hedge is finding favour once more as enthusiasts come to the defense of this once-loved asset.

All shapes and sizes

When we speak of hedging, there is no uniform definition. There are low

bushy ones, clipped box hedging in rose gardens, ancient mazes of yew or the sculpted topiary of the aficionado. There are the tall, spectacular hedges that tower above country house gardens, trimmed by uniformed tree surgeons in cherrypickers. And then there are the garden hedges, proudly pruned specimens, of all shapes and sizes that give suburbia its painstakingly green and tidy aura. For the most part however, this mainstay of British greenery is a small, squat, thorny, scraggly, much-underappreciated bush. They get a moment of attention every autumn when they burst forth with colourful berries, haws, and hips. But otherwise, they are forgotten in plain sight, taken for granted and, too often, obliterated from our minds.

HEDGEROW TREES

15

TREES JOURNAL

For years, even tree planting champions regarded hedges as second-rate – not equal to that of ‘full grown’ trees – an unfortunate misconception that continues to this day by those looking to trees to absorb their carbon footprint.

But hedges don’t have to be compared to towering beech trees. While they rarely attain the grandeur of mature trees, they can be teeming with life, many species co-existing and making a living in its scrubby, scratchy, interior.

Recent campaigns are calling us back to recognise hedgerows as vital to our landscapes. After we have lost so much, we are now looking for places to put them back, to bring back the habitats they provide and to learn to love again the humble hedge we have taken for granted.

In this vein, the Tree Council launched, in 2021, the first ever National Hedgerow Week. Over seven days we were invited to ‘talk to the hedge’, not only to compliment a hedge on its ‘underbush’ or ‘fine wattle’, but to revive the nation’s interest in this quintessential feature of the landscape.

Changing Face of Britain

Anyone who is a fan of the game Geoguesser will understand that Britain is full of hedges. Geoguesser is an online game where you are given a picture of somewhere in the UK and you must try to pinpoint on a map where you are. Unless you are particularly lucky to be landed on Tower Bridge, the algorithm means you’re normally plonked out on a countryside B-road looking squarely into a hedge. Be it Kent, Cornwall, or Powys, small hedgy sideroads happen just about everywhere and tend to look all rather similar: wizen trunks of hawthorn being overtaken by rangy field maples clawing upwards in straight pencil-thick shoots, dog roses

16

HEDGEROW TREES

curving outwards in parabolas of thorns. These hedges largely came out of the Enclosures Movement in the 17th century onwards and the subsequent division of land into fields and private farms. Over the course of the following 400 years, these hedgerows became the boundaries for estates, parishes, and even counties, changing the face of Britain.

The subsequent post-war loss of farmland hedging during the 20th century has been, in a small part, compensated by the rise of the garden hedge. Far from just being a boundary between property, here they went on to become a mainstay of middle-classdom, an outward expression of one’s orderly and reputable life. Many a petty neighbourly heckle has been raised over a hedge – the playful perpetual bickering that keeps middle England on its toes. Such exchanges have in turn fuelled stereotypes about the ‘hedge-trimming classes’, the small-mindedness of suburbia characterised by Privet Drive in the Harry Potter novels.

Hedgerow Mechanics

So to dispel any ongoing misconceptions let’s state the obvious: hedges are trees, only planted in rows and usually trimmed. Many contain other flowering plants, such as dog roses, sea buckthorn, honeysuckle, and bramble (all very useful), but 90% of the hedge will be true tree species, such as hornbean, holly, hawthorn, beech.

What this means is that in many hedgerows you’re likely to find far more tree diversity than in an average woodland. In fact, the hedge creates diversity, by protecting species and allowing them to grow.

In her recent book, Wilding, Isabella Tree writes of the importance of brambles and spiky plants in protecting sapling oaks, pointing out that these rough

scrubby clusters are in fact essential for woodland succession. Baby oaks that would normally be browsed by deer and other grazing animals are left to grow tall, protected by the hedge.

What’s more, the intertwining of all these species make for very useful habitats. All those tiny spiky branches looping through each other like a giant bird’s nest is in fact excellent habitat for birds to nest. If the hedge has good diversity, this can mean food all year round – the differing timings of flowers and fruit can mean there is a continuous supply.

Hedgerow Champions

As the UK looks for ways to up its tree coverage, there is pressure on local councils and landowners to find space for this. In the arable areas of the country, this is no easy feat, as planting traditional woodlands will directly take away from food production. Farmers are quite rightly loath to do this on prime soils. Re-growing hedgerows, however, has been seen as a way of enhancing the landscape without detracting from the business of farming. Even in pastoral upland areas, hedgerows are becoming once again appreciated for their role in sheltering livestock from adverse weather.

With this mindset, suddenly the UK has a huge potential for tree planting. Even in areas of Grade 1 agricultural land, there is potential for miles upon mile of new trees to be planted.

The humble hedge is fast becoming the focal point of a conversation about what we want our country – both rural and urban – to look like. It’s encouraging to find at last some hedgerow champions.

Sam Pearce is the International Tree Foundation’s UK & Ireland Programme Manager

17

THE PRAYER OF THE TREE

You who pass by and would raise your hand against me, hearken ere you harm me;

I am the heat of your hearth on the cold winter night, the friendly shade screening you from summer sun,

And my fruits are refreshing draughts quenching your thirst as you journey on.

I am the beam that holds your house, the hoard of your table, the bed on which you lie, the timber that builds your boat.

I am the handle of your hoe, the door of your homestead, the wood of your cradle, the shell of your last resting place.

I am the bread of kindness and the flower of beauty, You who pass by, listen to my prayer: Harm me not!

ST BARBE BAKER

TREES JOURNAL

18

THE BUSINESS OF RESTORATION

Part

3

ENSURING THE SURVIVAL OF THREATENED TREES IN KENYA

Ensuring the Survival of Threatened Trees in Kenya

Creating a Global Tree Assessment (GTA), to understand and quantify the conservation status of every known tree species is no mean feat.

This ambitious task, coordinated by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BCGI), took a little bit more than five years and the effort of specialists around the world. Indeed this global network spanned over 60 institutional partners and over 500 experts.

The assessment quantified 58,497 tree species worldwide. Shockingly, 30% of these tree species are threatened with extinction.

Arboreta and Botanic Gardens around the world are undertaking major efforts to conserve these trees. However, in situ conservation is also vital. That’s why BGCI and International Tree Foundation are spearheading an effort to plant more threatened species in all the 10 counties in Kenya where ITF and partners are active.

Protecting Kenya’s Native Trees

In Kenya, there are 1,100 native tree species. One hundred and forty of these tree species are threatened with extinction. International Tree Foundation is working with the communities and many other partners to ensure that none of Kenya’s tree species become extinct.

TREES JOURNAL

20

Effective conservation of threatened trees depends on accurate information on their distribution, population size and threats. That is why, for the past two years, BGCI and Kenya Forest Service have held a series of workshops to plan conservation and action for Kenya’s threatened tree species. The workshops had participants from government, non-government organizations, corporates, farmers’ groups, researchers and many others.

By using already available conservation assessment data, International Tree Foundation, BGCI and other partners came together and developed a project, Mainstreaming Threatened Tree Species, which has begun in four counties in Kenya.

National Pride to Protect Trees

It is vital that we avoid species going extinct, while also responding to the Sustainable Development Goals, the emerging Convention on Biological Diversity Targets and Kenya’s Vision 2030.

The Mainstreaming Threatened Tree Species project’s long-term vision is that by 2030, it will be a matter of national pride to be conserving Kenya’s threatened trees, reflected in government policy, protection of trees, restoration of forests, provision of nature-based benefits to communities and resilience to climate change.

BGCI and ITF have been delivering surveys and workshops since June 2021 on identification and monitoring of threatened trees, seed collection, propagation and planting. The project will bring 20 threatened tree species into longterm monitoring, propagation and planting programmes. These species are being incorporated into ongoing restoration, enrichment planting, river rehabilitation, agroforestry and school projects led by

ITF’s partners, and funded through ITF. The workshops help local communities to identify and monitor threatened species, collect seeds and include them in nurseries and reforestation projects to ensure their continued survival. Through this work the future of Kenya’s native trees is being secured while increasing tree cover and forests.

The communities have already started seed collection and sowing. The project has an ambitious goal of growing 50,000 trees across five counties, Marsabit, Meru, Tharaka Nithi, Kiambu and Embuto. We are happy to report that seedlings from the threatened tree species are already growing in the nurseries. And we are pushing the project forward to bring these workshops into all 10 of the proposed project areas.

Kirsty Shaw leads BGCI programme of work on tree conservation and ecological restoration. Teresa Gitonga is International Tree Foundation’s Kenya Programme Manager.

ENSURING THE SURVIVAL OF THREATENED TREES IN KENYA 21

TREES THAT EMPOWER

My name is Tabitha Njoki Githinji, an empowered woman. I was born in Gathareri village in Embu County, Kenya. I am currently the secretary of the Wamiti Kambefo women group. It’s one of the oldest self-help groups in Embu. Wamiti women group was started in 2002. There are 75 members in total, women being 65 and men are 10 in number respectively.

My interest in tree planting started when I was a very small girl, I used to go to the forest to fetch firewood with my grandmother. While still young my mother could go with me to a women’s group meeting which was very interesting for me.

My grandmother contributed heavily to my knowledge of specific trees and their value, especially medicinal trees in the forest. My passion for trees grew, shamba system (cultivation in the forest while planting trees) had just been introduced in Kenya in the 1980s.

I grew up knowing that being a member of a women’s group is important.

I loved podocarpus tree species because of its usefulness in cooking, energy and construction. I used to accompany my mother to the forest to cultivate. As a young girl I was always attracted by the beauty of Columbus monkeys jumping from one tree to another and eating fruits that were readily available in the forest. Orange forest also had huge families of elephants.

I grew up knowing that being a member of a women’s group is important. Together with other women, we started the Wamiti women group. To date we have planted over 150,000 trees in the forest. We have also planted trees on our farms and I

don’t need to go to the forest to get firewood. Most women in the Wamiti women group do not need to go to the protected gazetted forest for firewood. Table banking and the benefit from tree seedling raising and planting have economic perks for me and Wamiti women.

My grandmother contributed heavily to my knowledge of specific trees and their value, especially medicinal trees in the forest.

My work as a group leader is to empower more women, I have known International Tree Foundation since the launch of tree planting project in Irangi Mount Kenya forest in 2016. Since then I have been a major beneficiary of ITF projects.

ITF supported us with agroforestry seeds such as calliandra, lucerne and grevilia. They have also trained us on the use of efficient energy technologies. In addition, ITF has been purchasing tree seedlings from our nursery thus earning money which we use to pay school fees for children and to improve our livelihoods. We also participate in tree planting in the forest which helps us to earn more money.

I would urge International Tree Foundation to continue with the good work of supporting communities because it has made us improve our livelihoods, empowered us as women and contributed towards restoration of degraded areas in Irangi forest.

Tabitha Njoki Githinji, Embu County, Kenya.

23

TREES THAT EMPOWER

BAKER COLLECTION

AT UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN

International Tree Foundation’s founder, Richard St. Barbe Baker arrived in the Canadian prairie city of Saskatoon in 1909, and the following year enrolled in the second class of the newly-established University of Saskatchewan.

After his passing in 1982, the University agreed to host St. Barbe’s extensive archives. Already one of the four most requested archival collections at the University, a new Baker Collection website has been launched to coincide with ITF’s centenary in 2022.

This venture is part of a project to digitise a major portion of the contents. The first phase, now being completed, includes photographs, audio, film, St. Barbe’s books and footage from Academy Awardwinning Christopher Chapman’s unfinished documentary.

To access the Baker Collection you can visit: stbarbe.library.usask.ca

Many may recognise the photo of the first Dance of the Trees from the Baker Collection, few will have seen St Barbe’s typed note attached to the back.

TREES JOURNAL

25

St Barbe Baker with children at a tree planting ceremony.