Contents

4 Introduction – from James Whitehead, CEO

5 Good news – snapshots from the ITF community and the world of trees

8 ITF loves – a round-up of recommendations from the ITF team

10 Recipe – Anna Stanford from Anna’s Family Kitchen cooks up a Wild Garlic and Mushroom Risotto

12 A nature paradise in a Paris cemetery – an extract from a new book by head curator Benoît Gallot

16 Tree planting is still best – a study finds tree planting remains the best form of carbon capture

18 The many benefits of trees – illustrator Nina Chu shows just how much trees do for us

20 Growing crops in a parched landscape – how ITF's work is tranforming women's lives in Kenya

22 The Gifts of Forests – an excerpt from Levison Wood's new book, The Great Tree Story

27 Poetry competition – winning poem, The Forest by Iris Stapleton Smith

28 Tree heroes – the story of one of ITF's many tree planting superheroes

30 Crossword – test your knowledge on the theme of trees

32 A rare opportunity to plant within the M25 –when a local council chooses nature over profit

34 My favourite tree – Author Jonathan Drori writes about the tree of his childhood

Introduction

At the International Tree Foundation (ITF), our mission is rooted in creating impact where it matters most. This year’s journal celebrates the many ways we bring that vision to life - working hand in hand with local communities and supporting their ambitions to restore, protect and reimagine their landscapes for lasting change.

In East Africa, we partner with communities living on the frontline of climate change, in some of the continent’s most ecologically sensitive regions. Our partnerships with grassroots organisations ensure sustainable restoration efforts through robust monitoring, knowledge sharing and long-term support.

Here in the UK, our work continues to grow in scope and reach: from rewilding projects and community orchards to urban tree planting and community land buyouts.

At the heart of this year’s journal lies a simple but powerful truth: trees transform lives. You’ll read about the remarkable women of Kenya’s West Pokot region, where trees and training are creating new opportunities; about Daniel Misaki’s inspiring journey from poacher to conservationist; and about the many ways trees enrich our imagination from Nina Chu’s joyful illustration to excerpts from new books exploring our enduring bond with forests.

On behalf of everyone at ITF, I would like to extend our heartfelt thanks for your generous support. You’re helping to restore our planet, one tree and one community at a time.

James Whitehead CEO, International Tree Foundation

Good news

Discover the latest tree news and stories from the ITF community plus the impact your generous donations are making for people and planet. Visit internationaltreefoundation.org to read more good news

Growing endangered trees

In Meru, Kenya, an ITF project to plant and grow threatened trees, is flourishing. The local nursery team has been carefully nurturing many species, among them the Calodendrumcapense or Cape chestnut - a beautiful ornamental tree known for its shade.

From collecting seeds from the mother tree, soaking and nicking them to speed up germination, to caring for the young plants as they grow, every vital step means the seedlings are now ready to be planted in a nearby forest restoration project.

Boost to England's tree planting

The 2024-2025 planting season saw England’s tree planting rates increase by 52% from the previous year with 5,529 hectares of new woodland planted. Projects include:

An ambitious project from the National Trust and England’s Community Forests to create around 519 hectares of new woodlands and woody habitats across England.

The new LincWoods project from Lincolnshire County Council, in partnership with the Woodland Trust, aiming to plant 200,000 trees and 20,000 metres of hedgerows across the county by 2026.

The Trees Call to Action Project, a three-year initiative that has seen over 275,000 trees planted in the West Midlands, aiming to benefit the environment and local communities.

A grades for tree planting students

Schoolchildren are growing up in a climate crisis, surrounded by news of rising temperatures, droughts and disappearing wildlife. But when they plant trees, they become environmentalists, working to create a greener future.

One such school is Loglogo Girls Secondary School, in Marsabit, Kenya, where we've been planting trees with local group, Napo Organization.

These trees are not only providing shade, fruit and combating drought. They are also bolstering the school’s agriculture studies - a critical component of the syllabus.

First seeds

The Wollemi pine, a prehistoric tree first discovered in Australia in 1994, is one of the rarest trees in the world with only 100 specimens known to exist in the wild.

In August, a Wollemi pine in Pear Tree Garden, Worcestershire, produced seeds for the first time, from which more trees can be germinated and grown.

Hope for ash

Ash trees have so far been fighting a losing battle against an invasive fungus. They have been dying in their millions across the UK.

But according to a recent study in the journal Science, new generations of ash trees are evolving a resistance to dieback. Small changes in the DNA of young wild ash trees appear to protect them from dieback. This gives hope that a more resistant population of ash trees could be bred to support natural recovery.

A bamboo barrier

The river Lhubiriha is a lifeline for communities in western Uganda. It flows from the Rwenzori Mountains into Lake Edward and is a critical source of water for agriculture, drinking and hydropower for the region. But deforestation and farming close to the water's edge have weakened its banks, causing catastrophic floods which have stolen many lives.

Working with the local communities we’ve planted 20,000 bamboo trees along its banks. Bamboo may look flimsy, but it’s a strong, hardy and fast-growing plant, whose roots strengthen riverbanks, making a firm barrier against flooding.

Little trees, big boost

A biodiversity study of two ITF projects in Oxfordshire has revealed a boost in insect life compared to adjacent plots. Volunteers planted a range of native trees in 2019 which are now attracting 77 different species of insects, pollinators and other invertebrates - a density 250% higher than unplanted neighbouring fields. Modest efforts can make a big difference for local wildlife in an urban setting.

India’s Aravali Green Wall Project

Inspired by Africa’s Great Green Wall, India has launched the Aravali Green Wall project, aiming to restore 24,990 hectares of degraded forest land across five districts in Haryana over three years to prevent desertification.

Plants produce more nectar when they ‘hear’ bees buzzing

Scientists at the University of Turin have discovered that plants produce more nectar when they ‘hear’ bees buzzing, suggesting a more symbiotic relationship between plants and pollinators than previously thought. The research team behind the discovery suggest that buzzing noises could be used on farms as an environmentally friendly way of enhancing the pollination of crops.

Cleaner and healthier

Community members in Malava, Kenya are learning how to install eco-stoves. Elizabeth Mukaisi received the first one. She was overjoyed and expressed her deep gratitude, saying that she will no longer need to make daily trips to the forest for firewood. She also shared her excitement that the ecostove makes her kitchen cleaner, healthier and more welcoming for her family.

Extinct trees make a royal return

After being thought extinct for 28 years, the Wentworth Elm has been revived at the Palace of Holyroodhouse and at Highgrove Estate. Three young trees, raised from cuttings taken from two mature specimens discovered growing at Holyroodhouse in 2016, have been planted at the two royal estates.

Wildly Different: How Five Women Reclaimed Nature in a Man’s World

Historian Sarah Lonsdale traces the lives of five women across five continents who fought for the right to work in, enjoy and help to save the earth’s wild places.

Press reviews call it “spellbinding”, “fascinating” and “brilliantly dispatched”.

ITF loves READ

Recommendations from the ITF team

The Stuff that Stuff is Made Of

Did you know that there's seaweed in ice cream, cork in spacecraft and dandelion in truck tyres?

ITF’s trustee, Jon Drori has released a delightful and beautifully illustrated new book for children which shares the surprising stories of how nature is in items we use every day.

Byway is the way

This B Corp flight-free travel platform combines routing technology and local expertise to create unforgettable flight-free trips by train, bus or ferry. By using Byway, travellers will see lesser-known gems, avoid traditional tourist trails and support local communities.

Sponges that compost

Did you know that traditional washing up sponges are made from plastic? Not only is that terrible for our planet, it can leak microplastics every time you wash up. Switch to compostable sponges which last longer and can biodegrade.

Companies like Seep or Composty are worth a try.

Sheep Inc.

The first carbonnegative fashion label and a standard bearer for transparency. Sheep Inc's knitwear uses the finest Merino wool, sourced from farmers dedicated to environmental and animal welfare.

Fixing your kettle fill

The vast majority of us overfill our kettle, squandering a staggering £70 million per year in energy. A simple fix: use a Sharpie to mark your own fill lines on the kettle that correspond to your favourite cups.

Rescuing odd food

Around 25% of food waste in the UK happens on farms – more than retail, manufacturing and hospitality put together. Oddbox ‘rescues’ food that's at risk of being wasted (too big, too wonky, too many) and delivers it to customers through its fruit and veg box scheme.

A second chance for umbrellas

BBC Curious Cases

Dr Hannah Fry and Dara Ó Briain tackle listeners' conundrums with the power of science.

Expect a vast range of subject matter from the chemistry of love and the world’s fastest fly, to teenage sleep patterns, to how many lemons it takes to power a spaceship.

BBC Radio 4 Ramblings

Original Duckhead’s colourful umbrellas are made from postconsumer recycled plastic waste, helping to divert the 1 billion plus brollies discarded annually from landfill.

Sleep well, plant trees

Stay in any of Address Collective's beautiful boutique hotels and if you opt out of room cleaning, they'll plant a tree in one of ITF's projects in East Africa or Ireland.

Clare Balding walks and talks with a different guest each week in a different part of our glorious countryside. Radio gold.

In Defense of Plants

A podcast brought to you by ecologist and botanyenthusiast Matt Candeias that celebrates plants from the smallest duckweed to the tallest redwood and all the wonder of botany.

Wild Garlic & Mushroom Risotto

By Anna Stanford of Anna’sFamily Kitchen @annasfamilykitchen

Anna creates healthy, home cooked meals that are beautifully presented but don’t require hours of prep in the kitchen

Serves: 4

Prep: 5 minutes

Cooking: 30 minutes

Total: 35 minutes

Ingredients

2 onions finely chopped

2 garlic cloves crushed

Two handfuls wild garlic

30g dried porcini mushrooms soaked in 100ml boiling water

500g mixed wild mushrooms

300g Arborio risotto rice

150ml white wine

1.4 litres hot stock

40g grated Parmesan or Pecorino

15g butter

Juice of half a lemon

Fresh thyme

Method

1 Tear the leaves off the wild garlic and set them aside. Chop the wild garlic stalks.

2 Colour the onion in a pan with some oil for 10 minutes before adding the garlic and chestnut mushrooms. Stir for a minute then add the Arborio rice and the wild garlic stalks.

3 After 1 minute add the wine and let it bubble.

4 Using a fork to remove the soaked porcini from their stock. Roughly chop them. Add the liquid to the pan together with the chopped porcini.

5 Add the stock one ladleful at a time until the rice is cooked (about 25-30 minutes). The texture should be creamy.

6 Sauté the mushrooms in a hot pan with the butter and the fresh thyme for 5 minutes. Roughly chop the wild garlic stalks and add these too.

7 Stir through the sautéed mushrooms and most of the Parmesan or Pecorino into the risotto. Squeeze in the lemon, season and serve with extra grated cheese. And if you have any wild garlic flowers (they’re edible!) those too.

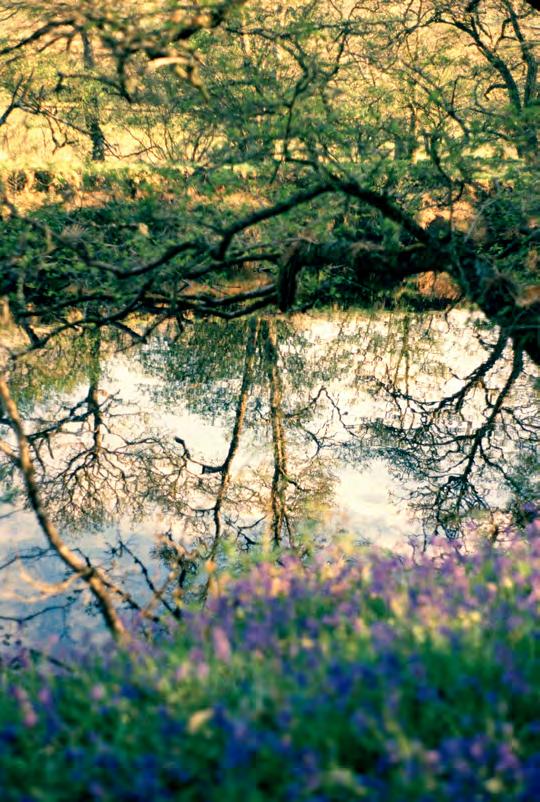

Restoring nature in the Ivry Cemetery, on the fringes of Paris

By Benoît Gallot

Benoît Gallot, now head curator at the celebrated Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, pulls back the curtains on Ivry, another of the city’s famous cemeteries where he also worked. In this extract, Gallot describes how Ivry has become a refuge for flora and fauna thanks to the transformative effect of rewilding

My first experience as a cemetery curator was at the Ivry Cemetery, just outside Paris. When I stepped into the role in 2010, I’d never been handed so much autonomy or responsibility. After taking some time to settle in, I gradually modified a number of internal procedures and set out to improve archive conservation. My team and I digitised all records and overhauled the system for organising concessions. It was nothing exciting, but I wanted to do right by my cemetery and manage it to the best of my ability.

To me, the cemetery’s natural elements were just a managerial headache. While its 1,900 trees were no doubt beautiful, all I saw were the piles of leaves the groundskeepers would have to rake and the complaints that might land on my desk as a result. And although I noticed the cemetery was home to a wide variety of birds, including what looked like parrots, I was primarily concerned with the droppings that littered the benches and tombstones. In those days, biodiversity was the least of my worries, and my environmental awareness was limited to recycling.

In 2011, Paris City Council passed a biodiversity plan calling on Parisian cemeteries to reduce their pesticide use.

For decades, maintenance crews had sprayed walkways with weed killer whose stated goal was to destroy any wild plant that had the audacity to grow between gravestones. Each spring, the weeks-long crusade required workers to show up in full-body protective gear, and the treated sections had to be temporarily closed to the public. Only after the green areas had been sprayed with chemicals would they be deemed “clean”, i.e., lifeless. The result met user expectations and matched my own understanding of cemeteries, namely that everything surrounding the deceased should be dead, like them. Any trace of life was seen as a sign of disrespect. Flowers were allowed, but only if they were in planters. Even then, most were only used once a year, on All Saints’ Day, for the traditional chrysanthemums. Flowers had their placeas long as that place was on the headstones.

Naturally, the Cemetery’s grand avenues were lined with majestic trees and shrub beds. Greenery was not, however, encouraged to flourish inside the confines of its forty-seven divisions. Only one was designated as “landscaped”, meaning that a few trees and shrubs had been planted between the graves. It represented an acceptable level of disorder within a cemetery whose rows of graves were aligned with military precision. In other words, it was the touch of whimsy that proved we were open-minded and not overly rigid.

When it came time to enforce the new pesticide-free policy, my knee-jerk reaction was “Why are we doing this? We’ll be swamped with complaints. We’re a cemetery, not a park!” But my teams and I didn’t have a say in the matter, so we played along to placate our superiors and elected representatives. At their request, no chemicals would be used in three of the cemetery’s designated pesticide-free

divisions. We didn’t realise it then, but a small revolution was taking root.

The transformation process took four years, during which time my attitude and that of my colleagues changed radically. As the years passed, more divisions were designated as pesticidefree. We received help from a consulting agency, purchased machinery and other equipment, trained groundskeepers in new maintenance techniques, seeded divisions that proved difficult to regreen, and brought in a landscaping company to gradually grass over the sidewalks.

Meanwhile, cemetery staff were so inspired that at the end of 2014, we made the decision to stop using pesticides across the entire seventy-acre site. What could explain such a radical shift? It was the green. The power of green. It goes without saying that green paths are prettier than dirt or gravel paths. Once we surrendered our chemicals, the cemetery began to change before our eyes, becoming an oasis of foliage bursting with natural beauty. The groundskeepers, whose work had always been considerably undervalued, also experienced a shift in their role. Up to that point, they had toiled thanklessly in the shadows. Nobody gave them a second thought unless there was a problem: if there were piles of leaves, dirty

toilets, or overflowing trash cans, the groundskeepers weren’t doing their jobs. The pesticide-free policy thrust these workers into the limelight by giving them a chance to play up the site’s aesthetics. They gained visibility by trading in their weed killer for lawn mowers. Visitors began to admire the grounds in the wake of their efforts, and the groundskeepers started to take pride in their work. In the end, those four years taught us a beautiful lesson: how to balance respect for the dead with respect for life.

On a personal level, I credit the zero-pesticide policy with opening my eyes to the cemetery I managed. As the paths greened over, so did my attitude. I became fascinated by the rainbow of wildflowers: the deep-blue grape hyacinths, the bright-yellow lotus, the orange marigolds, and the lizard orchids that smelled strongly of goats. The cemetery began to feel more like the countryside, and I was increasingly aware of how lucky I was to exist inside this bubble of biodiversity wedged between the high-rises of the Parisian suburbs. As wildflowers proliferated, they attracted butterflies, bees, and other insects. A new ecosystem was emerging.

And yet, I lacked the knowledge to fully appreciate

the transformation unfolding before my eyes. My field of expertise is the funeral industry; I didn’t know much about plants and animals. It was a chance encounter with Pierre, one of the cemetery’s regular birdwatchers who lived nearby, that changed my outlook forever. Our paths crossed one afternoon, and the amateur ornithologist took the time to explain his observations and what they meant for the area’s biodiversity. It dawned on me that the cemetery was home to an exceptional array of wildlife, and I wanted to learn more. From then on, whenever I walked the grounds I would look beyond the gravestones to watch titmice, starlings, blackbirds, ring-necked parakeets, woodpeckers, and other birds flitting from tree to tree.

In 2017, to my great surprise, we were joined by a new group of playmates. After six years of transformation to promote biodiversity, a family of foxes took up residence in Ivry Cemetery. You can imagine our pride! We took their arrival as the reward for our efforts to make the cemetery a place not only for the dead but also for life. Suddenly, I found myself photographing foxes and their kits, hedgehogs, squirrels, and even tawny owls in my own backyard. I could scarcely believe it; although I’d grown up in the countryside, I was seeing more wild animals in the city than I ever had before. My pictures of wildlife began to pile up, and I found it hard to keep my newfound treasures to myself. I wanted to share them with other people and shed light on this aspect of the cemetery…. On June 3, 2017, @la_vie_au_ cimetiere was born.

In early 2018, I learned that my colleague and fellow curator at the Montparnasse Cemetery had decided to retire. After spending eight years at Ivry, I felt ready

to move on. I was itching to manage a cemetery within the city limits, one that presented the additional challenges of being a heritage and tourist site. Managing Montparnasse also meant managing its satellite cemeteries, including Passy, which may have the highest ratio of famous residents per square foot in the city. I applied for the job, hoping I’d get it. Unfortunately, my boss called in early April to tell me another of my colleagues had been chosen. “It’s a shame, but...” He went on to say that the curator of Père-Lachaise was planning to retire around the same time and that he wanted me to apply for the job.

I’m frequently asked how one becomes curator of Père Lachaise. I always reply, “By accident.” And yet, deep down, I’ve often wondered if it was my destiny. I’ve never believed that our fate is written in the stars; a life without surprises would be too sad. But I have to admit that, looking back, it does seem like an invisible hand gave me a nudge - two nudges, really - in the right direction.

thanks to Greystone

Tree planting is still the best way to remove carbon

Planting for an uncertain future: a new Exeter University study argues that in conditions of extreme climate uncertainty, the rewards of tree planting outweigh the risks

Governments worldwide have pledged to expand tree cover to remove greenhouse gases, with the UK committing to plant 30,000 hectares of trees each year until 2050.

However, environmental economists point out that there are significant risks that come with converting farmland to forests in a future of climate change and economic uncertainty.

These include the risk of large-scale tree planting displacing agriculture and impacting food security, depending on where it takes place.

In a study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the researchers use the UK as an example to demonstrate that uncertainties about climate change and the economy make the difficult trade-off between carbon removal and agriculture even trickier.

Frankie Cho, a PhD graduate from the University of Exeter and lead author of the study, explains: “One problem is that, because it is unclear what countries round the world will do to tackle climate change – we don’t know how challenging the climate will be in the future. If climate change is extreme, broadleaf trees in southern UK offer the best carbon removal – but that’s prime farmland and could be really costly under certain economic futures.

“If climate change is milder, planting conifers on less productive land makes more sense, but those trees will not grow well if conditions are more extreme. The problem

is that we don’t know what the future holds and can’t be certain which type of trees we need to plant and where.”

However, using recent advances in the theory of decision-making under uncertainty, the researchers show that despite these risks tree planting can still be the most costeffective way to remove carbon.

Their study shows that a ‘portfolio’ approach to tree planting – diversifying species and planting locations – helps balance risks and moves beyond planting strategies that simply hope that everything will be okay.

This strategy minimises the danger of betting on the wrong future, ensuring treeplanting decisions remain resilient in the face of uncertain future climatic and economic conditions.

Importantly, they show that if policymakers adopt these portfolio approaches to tree-planting, it becomes a far more cost-effective strategy for carbon removal than alternatives like biomass energy with carbon capture and storage or direct air capture technologies.

Co-author of the study Professor Brett Day, from the University of Exeter, added: “We don’t have any other option that can remove carbon from the atmosphere at the scale and cost that we need to meet our Net Zero targets. While tree-planting carries risks, our study shows that, if done strategically, it remains the best solution we have.”

With thanks to the University of Exeter, authors of the study Resilienttree-plantingstrategiesfor carbon dioxide removal under compounding climate and economic uncertainties , published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

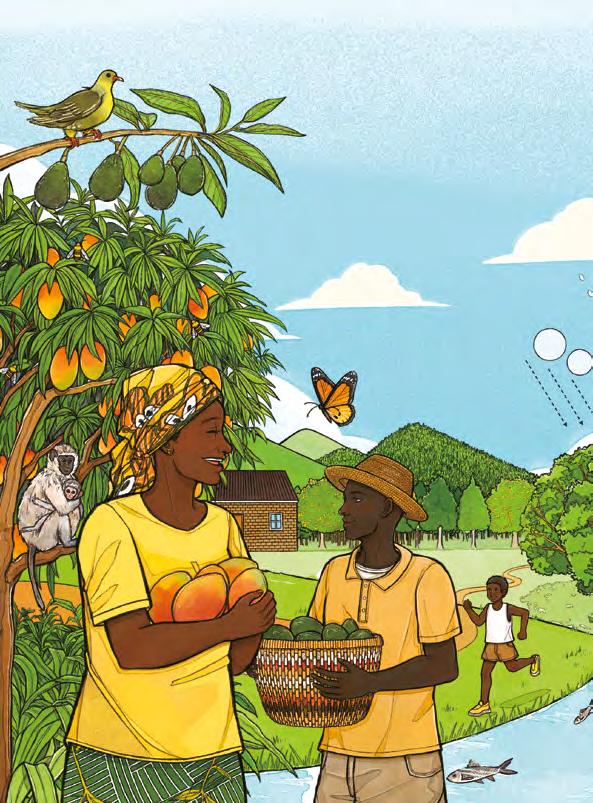

The many benefits of trees

Support biodiversity

Provide fruit and medicine

Provide natural resources

Create sustainable farms

Boost rainfall

Capture carbon

Create wildlife corridors

Block noise

Provide habitats for wildlife

Boost community connection

Regulate water temperature

Reduce surface flooding

Store water in soil

Produce life-giving oxygen

Filter air pollutants

Create cultural links to our past

Beautify

the environment

Cool the air

Improve air quality

Reduce stress

Boost property value

Improve illness recovery times

Provide cooling shade

Provide UV protection

Improve wellbeing

Learning to grow an abundance of crops in a parched landscape

West Pokot, Kenya is a region defined by its dry and harsh climate. On top of which, decades of deforestation have exacerbated the problem. Streams have dried up. Crops struggle. And natural disasters are increasing. But trees and training are changing the narrative

Vivian Chepkemoi lives in Morpus, West Pokot. Like many women in her community, she struggled to grow enough food for her family. The prolonged droughts and dry conditions meant there was never much to show for her toil.

But there are farming techniques which have proved incredibly effective in arid environments. When Vivian heard that there was going to be training on climate smart agriculture, she signed up straight away.

“I joined the training because I wanted to find a way to grow food for my family despite the dry conditions,” Vivian said. “We were taught how to use

Zai-pits and vertical bags to grow vegetables even with little water.”

"I never thought I could grow vegetables in such dry land. Now, my children eat better and I even make some money from what I sell"

matter that captures rainwater and runoff, allowing crops to grow in otherwise unproductive soils. The pits help restore soil fertility, promoting moisture retention and reducing erosion.

Vertical gardens are as they sound, layers of crops on top of each other. These multi-storey beds allow farmers to maximise space and grow a variety of crops, while conserving water.

Climate smart techniques are all about practical ways to grow fruit, vegetables and herbs in difficult conditions. But they don’t just increase harvests, they also help improve the environment.

Zai pits are small, dug-out basins filled with organic

From kale and spinach to a surplus of vegetables

Vivian took an active role during the two-day training, delighted to be upskilling herself. She and the other women in her community learnt how to construct Zaipits and manage vertical

garden systems. After the training, she received equipment to start her first vertical garden. She set it up straight away and began planting vegetables such as kale and spinach. Within a short time, she was harvesting enough for her family’s daily needs. Soon after, she started selling the surplus to neighbours.

This has not only improved her family's nutrition but has also reduced the money spent on purchasing food. “This project has changed my life,” says Vivian. “I never thought I could grow vegetables in such dry land. Now, my children eat better and I even make some money from what I sell.

“I feel proud and more confident now. I believe that even in dry areas, we can still thrive with the right knowledge and support. I now see trees and farming in a new light, this project has opened my eyes.”

Planting 22,385 seedlings

Thanks to this project in Morpus, West Pokot, there are now two community tree nurseries run by local women. These nurseries are the source of trees for the local area.

In their first year they grew 22,385 seedlings which have been planted on farms and schools. The species planted include fruit trees for nutrition and native trees which are providing shade, helping to enrich the soil, bringing back biodiversity and restoring the local landscape.

And the nurseries are providing a sustainable source of income for the women who manage them.

“When you empower a woman, you empower a community,” says Mercy, ITF's Kenya Programmes Manager. “Through training, capacity building and commitment from these wonderful women, cultural barriers are being broken. Women are buying cows from proceeds earned from the sale of tree seedlings and establishing green leafy vegetable vertical gardens that use minimal water.

“This is a first for a community where cattle are only owned by men. The women are breaking cultural barriers and moving towards attaining equality, improving their nutrition and increasing their selfworth and dignity.”

The gifts that forests bring to humanity

In his new book, TheGreatTreeStory, the British explorer, author and photographer Levison Wood explores the profound influence forests have had on our planet and civilisation from their vital role in our past to their importance for our future

Many old Japanese folk stories revolve around the kodama, a kind of spirit or deity that lives in the trees. People believed that kodama travel around the forest, retaining ancient knowledge that is passed down through the generations. If you cut down a tree that has a kodama living in it, you will be cursed.

The most ancient and revered tree in Japan is the Jōmon Sugi, a large Cryptomeria, or Japanese cedar, on the southern island of Yakushima. Thick with moss, ferns and often shrouded in mist, the forest exudes a fairy-tale-like energy. Fittingly, this place was the inspiration for Hayao Miyazaki's anime film Princess Mononoke, which features the mythical kodama and the epic struggle between mankind and nature. The Jōmon Sugi is hollow at its centre and so it is impossible to date it accurately by counting the rings, but some scientists have suggested that it might be as much as 7,000 years old, which would make it the oldest singular living tree on Earth. While its age is in dispute, what is not is the importance

"It is almost as if we are evolved to be in tune with the forest"

that trees play in Japanese culture. Both of Japan's official religions, Shinto and Buddhism, believe that the forest is the realm of the divine. For Zen Buddhists, scripture is written in the landscape. The natural world itself is the word of god. In Shinto, the spirits are in the trees, in the rocks, in the wind and in the rivers.

Nature is not separate from mankind as it is by Western definitions. The need to keep harmony between the two can be seen in every aspect of Japanese life, from the design of many homes to the affection given to gardens and bonsai trees.

Shizen, which translates as nature, is one of the seven principles of Zen aesthetics. It reminds us that we are all connected to nature spiritually and physically, and the more closely something relates to nature, the more beautiful it is. Japanese art often portrays natural scenes where trees, mountains or waves are the dominant subjects, and humans play a minor role.

The 1980s hailed an economic boom in Japan. In the opulence of the times, Tokyo businessmen were known to carry around gold flakes to sprinkle on their food and in their drinks. Money was fast and fluid. It seems apt that also at this time, a concept developed that was a counterbalance to the capitalist frenzy, a panacea to the stress, speed, overwork and anxiety of everyday life.

other plants emit when repelling insects and other predatory organisms. Why humans should be stimulated by this is still unknown. But forest bathing works.

"It would be terribly sad if we were to say we were the last generation that played in the woods"

In 1982, in a nod to traditional Shinto and Buddhist practices that revere nature, Tomohide Akiyama, the director of the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, coined the term shinrin-yoku, or 'forest bathing'. This practice of forest immersion is an invitation to heal through nature. Participants disconnect from modern devices and remove other distractions to reset within the therapeutic forest environment.

With this new field of study, the government started to test whether the forest environment had positive effects on blood pressure, heart rate, cortisol levels and immune system responses. Evidence came back supporting what was intuitively suspected. In one study, subjects were exposed to three scents commonly found in Japanese woods - cedar, hiba oil and Taiwan cypress - and all the participants experienced stimulated activity in the prefrontal cortex of their brains, which allowed for increased focus and concentration and a greater degree of relaxation.

Dr Qing Li of the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo describes forest bathing as 'simply being in nature, connecting with it through our sense of sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch...when we open up our senses, we begin to connect with the natural world."

He cites other proven benefits too, including: reduced blood pressure, increased NK cells, reduced stress hormones and a balanced autonomic nervous system, as well as reduced anxiety, improved sleep, a counter to depression and even the release of anti-cancer proteins. It is almost as if we are evolved to be in tune with the forest.

"Forests harbour a treasure trove of plant species with potent medicinal properties, offering natural remedies for a myriad of illnesses"

The source of these benefits has been traced to the volatile secondary compound phytoncide, which trees and

With nearly half the adult UK population taking one form or another of prescribed medications, and around a quarter taking more than one medication, forest therapy offers an alternative to our struggling immune systems. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, the average American spends 93 per cent of their time indoors. Europeans are not that much better. We spend between six and ten hours a day glued to our computer and phone screensaddicted to technology and the dopamine rushes that social media encourages.

With so many benefits, it seemed remiss not to try. The first trial system for the forest-bathing practice was

created in Akasawa, in Nagano prefecture. In the 1990s a series of governmentsponsored 'Shinrin-yoku Trails' were established, to support citizens actively to participate in this healing. Now there are 65 such trails in Japan, each with self-guided programmes for forest immersion, as well as forest therapy guides.

The Indian poet, writer, philosopher and social reformer Rabignath Tagore (18611941) also agreed with this vision. He held firmly to the idea that learning should be done outside, in nature, and in the schools he founded, classes were mainly conducted

under the shade of trees. It would be terribly sad if we were to say we were the last generation that played in the woods.

Forests have given humanity another great gift: phytotherapy, the use of plants for medicinal purposes, arguably the most ancient form of medicine. Forests harbour a treasure trove of plant species with potent medicinal properties, offering natural remedies for a myriad of illnesses. The bark of the Pacific yew tree, found in North American forests, yields compounds used in chemotherapy drugs to treat cancer. Similarly, the rosy periwinkle (Catharanthus

roseus), endemic to Madagascar's rainforests, is the source of vinblastine and vincristine - essential chemotherapeutic agents used in the treatment of childhood leukaemia and Hodgkin's disease.

However, out of the approximately 50,000 known medicinal plant species, which serve as the foundation for over 50 per cent of all modern medications, up to a fifth are under threat of extinction at various levels - local, national, regional, or global - due to deforestation. And yet, our knowledge about potential drugs that can be extracted from rainforests remains in its infancy.

Knowledge of these medicines is the legacy of generations of indigenous communities using the forest as their pharmacy. When we destroy forests, we run the risk of not only species endangerment and extinction, but the obliteration of medicines we have yet to identify. Possible remedies for cancer, heart disease and diabetes are growing amid the trees, just waiting for our senses to grow sharper. Not only this, but it is estimated that around 80 per cent of the world's population living in the developing world relies on traditional plant-based medicine for primary healthcare.

Humans have long relied on the vast array of botanical resources to treat ailments ranging from infections to chronic diseases. Willow bark has been used throughout the centuries in China and Europe, and continues to be used today for the treatment of pain (particularly low back pain), headache, fever, flu, muscle pain and inflammatory conditions, such as tendinitis. The property within the bark responsible for pain relief and fever reduction is a chemical called salicin, which acts like aspirin.

Moreover, forests play a crucial role in mitigating the spread of infectious diseases. Research has shown that intact forests serve as buffers against zoonotic diseases, which are illnesses transmitted between animals and humans. Deforestation disrupts these natural barriers, increasing the risk of disease transmission from wildlife to humans. The loss of forest cover has been linked to outbreaks of diseases such as Ebola and Zika virus.

Threatened with dispossession and cultural elimination, these groups have been forced to find new and innovative ways to preserve their languages, spiritual practices and traditional knowledge, having to adapt and shrink into secret or underground settings. The perseverance of these cultures is a testament to the spirit of indigenous determination to keep the wisdom of the forest alive.

"Out of the approximately 50,000 known medicinal plant species, which serve as the foundation for over 50 per cent of all modern medications, up to a fifth are under threat of extinction"

It is a story of survival against adversity that calls for acknowledgment, restitution and solidarity with indigenous peoples from across the continents, as they continue to assert their rights. Indigenous leaders and activists elevate the voices of their ancestors and communities in their quest to reclaim their fundamental right of custody over their lands and the space to nurture their cultures.

Deforesting our medical cabinet, and the home of the indigenous communities who hold much of this traditional plant knowledge, is shooting ourselves in the foot. Potential medicines are underneath the forest canopy, waiting for us to take notice. However, the commercialisation of traditional medicines can also lead to overexploitation of natural resources in the region, as big pharma attempts to take a slice of the pie.

In the face of such existential battles, indigenous communities continue to demonstrate inspirational resilience.

The goal of indigenous equity both legally and culturally has a place as an intrinsic pillar in the fight against the numerous environmental and cultural crises facing global society today. Since the dawn of modern science, indigenous knowledge has often been beaten down into second place, but it is time to realise that new is not always best. There is a lot we can learn from those who have not forgotten the old ways. The time is now, as we stand at this critical juncture in human history, to use every tool in our box to save Earth's forests, and in doing so, save ourselves.

With thanks to Octopus Books for this extract from The Great Tree Story.

ITF's Poetry competition

Every year, to celebrate World Poetry Day and the International Day of Forests, which both fall on the same day, ITF invites 5- to 11-year-olds to write an original poem on the theme of trees and nature. This year's winner is eight-year-old Iris Stapleton Smith.

The Forest

The forest is waking,

I smell someone baking.

The trees are swishing,

The world is wishing.

The birds are singing,

The children are winning.

The leaves are crunching,

The boxers are punching.

The flowers are growing,

The gardeners are mowing.

The hares are running,

The foxes are cunning.

The deer are eating,

The parents are meeting.

The sun goes down,

The king’s getting crowned.

The forest is sleeping,

The bed is greeting.

Iris Stapleton Smith

heroes Tree

Daniel Misaki

Daniel Misaki lives in Western Uganda between Queen Elizabeth National Park and the Rwenzori Mountains National Park, two beautiful but deeply degraded landscapes. Daniel shared with ITF his journey from poacher to environmentalist

Daniel is from a family of poachers in Uganda. His parents, friends and community went into the parks illegally. Some to poach animals, others to cut down wood to make charcoal. For many, poaching wasn’t a choice, it was the only way to earn a living. It’s Illegal and dangerous and some of his friend’s lost their lives to it.

But the loss to the community goes even deeper.

“With the decreasing forest cover here we are now experiencing landslides because our area is mountainous,” says Daniel. “Rainy season is now described by landslides and floods. Homes are being blown down too, including mine. Without the trees wind travels with a very high speed, clearing everything that comes across its way. Every year we are burying people.”

A generation ago, farmers could grow and sell enough food, like beans and maize, to provide for their family and pay their children’s school fees. But now, crops are failing.

“The whole water cycle depends on the trees,” Daniel says. “They help form the rain, store it in the soil and push it back to the atmosphere. We are depending totally on rain and without rain everything is failing. Then the high impact is on livelihoods. We're a farming community.

“With the deteriorating forest, we are now starving. Farmers cannot actually afford to pay fees for their children and the school dropout rate is increasing. Because some men cannot afford the daily food for their homes, they are tortured and men are taking their lives. For example, in Karambi where I live, two people die by suicide every year.”

Changing mindsets

While still a teenager, Daniel started learning about environmentalism and his whole life changed. He knew he wanted to be a conservationist. He started a wildlife club at school to mobilise other students. Then he went to a college that specialises in the wildlife and natural resource management.

Now twelve years later, at just 29 yearsold he has founded and leads Ihandiro Youth Advocates for Nature (IYAN) - an organisation dedicated to promoting the sustainable use of natural resources and turning the tide on the degradation and poaching in his community.

Daniel believes that change starts with educating the children. By teaching children about the delicate balance of our planet, not only will a new generation grow up respecting trees and promoting the environment, they will go home and tell their parents, helping to transform the mindset of the whole community.

With support from ITF, Daniel and IYAN have planted over 6,000 trees within 10 schools. Trees that provide shade for students to sit under, stop dust, clean the air, provide fruit and valuable teaching opportunities, from potting, planting, tree maintenance and helping to expand the tree nursery. “We are concentrating on changing the mindset of these children,” says Daniel. “We're creating that feeling where someone says, the environment belongs to me.”

One success story is a student called Mbusa Seiz, who was so inspired by Daniel’s work at his school he went on to get his

Bachelor of Science in Agriculture. He is now working to help mitigate the worst impacts of climate change on agriculture.

'We need trees'

Daniel is seeing the change in the wider community too. “Now with scarce rains, people can see there is rain in the national park, where there are trees. But it doesn’t touch the community land. So people have seen it practically that where there are trees there will be rain.

“We have now started to plant trees in the homes of these children because the parents said, ‘we need the trees, you're telling us not to go to the park, but we need the trees so that we can have the branches from these trees’. In the March to June planting, we planted 15,500 trees.”

Be a tree hero

Every 15 minutes around 36,000 trees are cut down worldwide. Trees that provide oxygen, store carbon, protect wildlife and sustain people’s lives.

While the problem is global, solutions must be local. In many large-scale campaigns, up to half of the trees don’t survive - poorly chosen species, planted in the wrong places left without the care and protection that they need.

That is why ITF works with local communities and local tree heroes to plant trees and restore forests in places where, together, we can make the fastest, most lasting impact for communities and the future of our planet.

Can you imagine a world without trees? Neither can we. Join the restoration movement with a donation today.

Visit internationaltreefoundation.org/donate

Clues

Cryptic clues in italics

Across

1. Best used well-seasoned to stay warm (8)

6. Long-lived Mediterranean tree known for its oil (5)

8. Cut off the top and branches to encourage new growth (7)

10. Found inside plums (6)

11. SpikySouthAmericantreeissimianmystery (6,6)

12. 'Live, love leaf' could be ITF's new one! (5)

15. Site of infamous felling (8,3)

18. Invasive bush found in Kenya and other parts of Africa (7)

19. Ideal soil for tree planting (4)

20. Nuts known as 'marrons' in France, used in cooking (9)

21. Prickly savannah tree found in our logo (6)

23. Robin's old stomping ground (8)

28. Grows vigorously (7)

29. Wetelltheageoftreeswithconfusedgrins (5)

30. Leftinsidesacredcompanionforivy (5)

31. Spreadyourbetsandarguetocreateabushyfielddivider (8)

32. Holm oak, for example (9)

33. Sits above family and below class in tree classification (5)

Down

2. Oddly,Icontainmainbarriertotacklingclimatechange (8)

3. Winnie the Pooh character who lived in 'The Chestnuts' (3)

4. SoundslikethepoliceinAmericamakingasmallwoodland (5)

5. Excitement of a bumbling pollinator (4)

7. Climbing plant whose fruit makes wine (4)

8. Main job of a leaf (14)

9. Stage when an apple is ready to pick (4)

13. Small tree coppiced for making hurdle fences (5)

14. Prehistoric tree found growing in New South Wales in 1994 (7,4)

16. In biological taxonomy this comes after phylum and before order (5)

17. Iconic tree in Constable’s landscapes (3)

22. Mythological ‘world tree’ in Norse culture (3)

24. National park famous for ponies with plans to increase woodland (6)

25. Where Beverley Pippin and Annie Elizabeth usually live (7)

26. Tree-____: a bird or other animal that lives in trees (7)

27. Yearnsintenselyforconiferoustrees (5)

28. Ihearit’sthemomentforagardenherb (5)

A rare opportunity to plant within the M25

In an age when urban expansion often takes priority over green spaces, it’s not every day a local council chooses nature over profit. Yet, in the heart of Ealing, within the boundaries of the M25, an extraordinary project is taking root – literally

Thanks to a grant from ITF, local community group Letting Grow are planting 5,000 trees on an old golf course.

“This is a really unique opportunity – to plant trees within the M25,” says Sam Pearce, UK Programmes Manager at ITF. “It’s a really cool space because it is council-owned land that was once a golf course. Amazingly, instead of selling the land, putting up houses and making loads of money, the council kept it as an open space. That’s really impressive, especially as councils are under so much pressure these days.”

A multi-year mission

This project is spearheaded by local partners Letting Grow, who we worked with last year on a much smaller community woodland. “This is a much more ambitious project. It’s a multi-year effort,” explains Sam. “These 5,000 trees are just the start. They are looking to plant 10,000 next year.”

The planting site itself is part of a chain of green space that runs through Ealing following the River Brent, linking a network of open spaces. It’s a vital wildlife corridor and when it’s all planted it will be a great for wildlife as well as people.

The golf course only closed last year, its carefully manicured fairways still bearing the marks of its former use. However, fast forward ten years, and this

landscape will be unrecognisable. When these trees have really taken root it will be a diverse area with more bird life, pollinator friendly and also wilder.

“It’s a huge green space at the moment with some nice trees, but no woodland patches. So once the trees are grown, you will also be able to walk through the woods. It will be great to see the larger areas of tree cover and blocks of trees.”

Energy and passion

Some of the ITF team joined the project for a planting day with Letting Grow. With the help of volunteers from UPS and Ealing Borough Council they planted 500 trees and discovered lots of golf balls hiding in the grass.

“Letting Grow are a brilliant partner to work with as they are really full of energy and passion for our environment,” says Sam. “It’s inspiring and exciting.

“At ITF, we often work with a lot of retired people because they have the time to dedicate to restoration and community projects. But Letting Grow is made up of people in their 20s and 30s, and it’s great to see a younger crowd getting involved in greening up their local area.”

One of the most inspiring aspects of Letting Grow’s work is their engagement with young people. They work with disadvantaged kids and schoolchildren to connect them with nature and engage them with our natural world.

“There were a couple of kids on the day who weren’t fitting in at school and Letting Grow has taken them under their wing, providing them with a space to do something constructive outside of the classroom – where they feel more at home and have something to give. They looked like they were having a great time.”

Courageous conservation

It takes courage and long-term vision to prioritise environmental restoration over immediate financial gain. This project is a testament to what can be achieved when passion meets action.

“Hats off to the council for being brave and having the long-term vision for the space, and to Letting Grow for doing the planting.”

Volunteers from UPS join the planting

My favourite tree

By Jonathan Drori

One of my earliest memories is of a spectacular cedar of Lebanon, near my childhood home in southwest London. One winter morning, we found it dead, struck by lightning. Its huge trunk and limbs were strewn haphazardly and being sawn up. That was the first time I saw my father cry. I thought about the huge, heavy tree that was hundreds of years old and that I had imagined to be invincible, and wasn't; and my father whom I had thought would always be in benign control of all that was important. I remember my mother saying that there had been a whole world in that tree.

As a child, I couldn’t decode my mother’s subtle metaphor of there being a whole world in that cedar. I thought she just meant animals and birds, fungi and insects. But I can now see that my father cried not only for that one tree but for other losses that it represented. He had fled to Britain in the late 1930s and for the rest of his life, struggled to cope with the loss of his entire family in Central Europe during the Holocaust; the obliteration of his community and everything he knew. Like a fragile ecosystem, that too had been

a thriving and intricate world of delicate interdependencies; an exuberant web of life that seemed robust, and yet succumbed to the horror of man’s inhumanity to man.

There is a saying that, for evil to triumph, all that is required is for good people to do nothing. I feel strongly that this applies equally to our treatment of nature and to our human part of it. Empathy for people and the empathy for the natural systems on which our society depends, go hand in hand. That is why I love the International Tree Foundation, which supports communities living harmoniously with nature and causes both to thrive. We know, because we see it from our work, that when communities are treated well, holistically considering humanity alongside the rest of nature, the speed with which both flourish is a breathtaking, joyful and optimistic. And that is for me, the very personal message in the cedar of Lebanon.

Jonathan Drori, ITF trustee and bestselling author of AroundtheWorld in80Trees