In this Issue:

• Challenges in Treatment of a Hyper-Divergent Patient with TM-dysfunction, Maxillary Prognathism, Dento-alveolar Protrusion and Gummy Smile: A Case Study

• The Safety and Efficacy of Fixed Sagittal Appliance Therapy: A Clinical Survey

• Influence of Facial Structures on the Perception of Smile Esthetics between Laypersons and Orthodontists – A Cross-sectional Analytical Study

• Orthodontic Treatment of a Geminated Maxillary Lateral Incisor: A Case Report

International Journal of

VOLUME 35 | NUMBER 1 | Spring 2024 Visit the IAO online at www.iaortho.org

Published Quarterly by the International Association for Orthodontics

Orthodontics

Editorial

Hello fellow orthodontic practitioners, I am writing this editorial thinking about where dentistry and especially Orthodontics will be in the coming years. I do not have a crystal ball I only havethe lessons taught from my past to guide and help improve our profession.

As editor of the journal, I read a lot of articles submitted for publication.The managing editor, Mrs. Allison Hester, and I attempt to produce an interesting quarterly with articles that add to the orthodontic knowledge base so members can research like problems and their treatments when encountered in their practices.

This is a valuable benefit of IAO membership as is the ability topick up the phone and call someone regarding a clinical issue you may encounter. Please know that as an IAO member, you have that opportunity and ability to learn from each other.

The IAO has valuable resources to increase your clinical abilities. CaseworX, for example, is fantastic to record and document your cases. It is used to walk you through your fellowship application and after that your Diplomate. It is valuable to have your cases evaluated by your peers you learn from, and in completing the cases, you will have a broader appreciation of what you can do as an orthodontic health care provider.

As technology improves we will be able to understand when and how treatment needs to be applied to set up the best outcome. We, as general practitioners practicing orthodontics, have a front seat at the growth and development show. Our staff must be aware of this so that they can identify and

point out easily correctable clinical issues that if ignored, may worsen over time.

The common denominator in my years of orthodontic learning has to be the application of timely intervention, so that development does not result in undesirable situations. In the future, artificial intelligence may help guide clinical choices – for the end result of facial and dental beauty starts at a very young age.

I am excited to see what the future of the profession holds; however, this future stands on the shoulders of collegiality and cooperation. My suggestion is to help each other learn and obtain accreditation in this great profession of orthodontic health care.

I am always available for comments, complaints or suggestions regarding the journaI. I thank Mrs. Allison Hester, our managing editor, for her invaluable role in getting the journal completed and looking so good.

I have a request to all who read this, and the ask is to please help each other to write and submit articles or case reports to the journal. The journal is YOUR journal and you can make it reflect what is important to you today. In doing so making the journal better for everyone, now and in the future. Also , send the journal to your friends and share the knowledge.

Yours for accredited GP orthodontic education and better patient care

I remain

Respectfully

Dr. Rob Pasch DDS MSc IBO General Practitioner.

2

Dr. Rob Pasch Editor

Editor

Rob Pasch, DDS, MSc, IBO

Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

E-mail: paschrob@rogers.com

Managing Editor

Allison Hester

8305 Pennwood Dr Sherwood, AR 72120

E-mail: allisonhijo@gmail.com

Consultants

Adrian Palencar, ON, Canada

Michel Champagne, QC, Canada

Dany Robert, QC, Canada

Scott J. Manning, USA

Mike Lowry, AB, Canada

Edmund Liem, BC, Canada

Yosh Jefferson, NJ, USA

G Dave Singh, CO, USA

Monika Tyszkowski, IL, USA

William Buckley, OH, USA

International Journal of Orthodontics, copyright 2020 (ISSN #1539-1450). Published quarterly (March, June, September, December) by International Association for Orthodontics, 750 North Lincoln Memorial Drive, #422, Milwaukee, WI 53202 as a membership benefit. All statements of opinion and of supposed fact are published on the authority of the writer under whose name they appear and are not to be regarded as views of the IAO. Printed in the USA. Periodical postage paid at Milwaukee, WI and additional mailing offices. Subscription for member $15 (dues allocation) annually; $40 U.S. non-member; $60 foreign. Postmaster: Send address changes and all correspondence to:

International Journal of Orthodontics 750 North Lincoln Memorial Drive, #422 Milwaukee, WI, USA 53202

Phone 414-272-2757 Fax 414-272-2754

E-mail: worldheadquarters@iaortho.org

Challenges in Treatment of a Hyper-Divergent Patient with TM-dysfunction, Maxillary Prognathism, Dento-alveolar Protrusion and Gummy Smile: A Case Study, by Adrian J. Palencar, MUDr, MAGD, IBO, FADI, FPFA, FICD

The Safety and Efficacy of Fixed Sagittal Appliance Therapy: A Clinical Survey, by Stephen Deal, DDS, Crispen Simmons, DDS, Soroush Zaghi, MD

Influence of Facial Structures on the Perception of Smile Esthetics between Laypersons and Orthodontists – A Cross-sectional Analytical Study, by Dr. Fizzah Ikram, Dr. Rashna Hoshang Sukhia, and Dr. Mubassar Fida

Orthodontic Treatment of a Geminated Maxillary Lateral Incisor: A Case Report, by Rami Aboujaoude, Lina Aboujaoude, Falah Aboujaoude, Carla Jabre, Jad Nasr

Editorial, by Dr. Rob Pasch, DDS MSc IBO, Editor

Growing Beautiful Teeth Chapter 7: Max the Maxilla, by Estie Bav

Practice Management Tips: How to Achieve Consistent Case Acceptance, by Scott J Manning, MBA; Founder, Dental Success Today

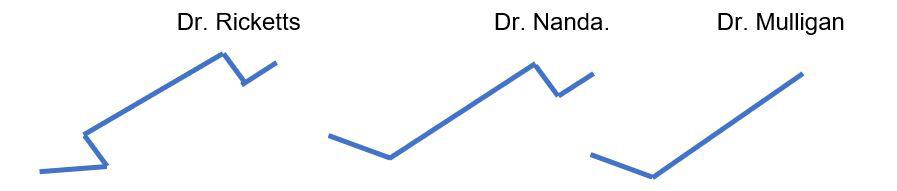

Tips from the Experienced: The Utility Arch, Part 1, by Dr. Adrian J. Palencar, MUDr, MAGD, IBO, FADI, FPFA, FICD

Author’s Guidelines

AUTHOR’S GUIDELINES FOR THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORTHODONTICS POSTED ONLINE AT www.iaortho.org. Past IAO publications (since 1961) available online in the members only section at www.iaortho.org.

SPRING 2024 VOLUME 35 NUMBER 1

Table of Contents

G&H Orthodontics 25 Highland Metals 30

International Journal of Orthodontics

Visit the IAO online at www.iaortho.org 6 16 2 12 26 14 31

Departments Advertisers

FEATURES

32 35

Challenges in Treatment of a Hyper-Divergent Patient with TM-dysfunction, Maxillary Prognathism, Dento-alveolar Protrusion and Gummy Smile:

Adrian J. Palencar, MUDr, MAGD, IBO, FADI, FPFA, FICD

A Case Study

AUTHOR

Dr. Adrian Palencar MUDr Komenski University (Stomatology), Bratislava Slovakia

Recertified 1970 Unversity of Western Ontario.

Master AGD, IBO Diplomate, Fellow Academy of Dentistry International, Fellow Pierre Fouchard Academy, Fellow International College of Dentists.

Recipient of IAO PINSKER Award (2003) IBO Examiner 2005-2014, Master Senior Instructor, IAO education Committee Examiner, IJO and Spectrum Ortho Consultant.

Assistant instructor Rondeau Seminars (21 years).

Authored 14 articles, co-authored 2 articles (with Dr David Pampena), authored 48 IAO Monthly Tips and 389 page “Case finishing and Mechanics” for Rondeau Seminars.

Abstract:

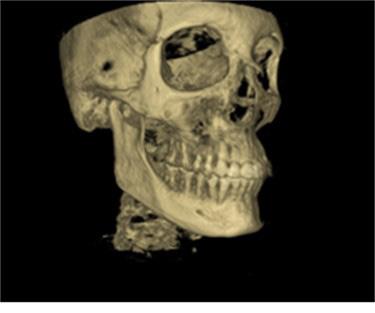

There are many challenges we face in our everyday clinical practice. Some patients have a robust set of problems, while others have few. Regardless of the number and nature of the concerns, we are obliged to diagnose and correct them so that the patient can be healthier and have better self esteem from an improved appearance. This article presents a case of a 31-year-old man with Class II skeletal and Angle Class II, Division 1 dental malocclusion, hyper-divergence, TMdysfunction, maxillary dento-alveolar protrusion, moderate crowding, and gummy smile. This complex case was treated firstly without extractions with Mandibular repositioning splint. However, later in the treatment the patient required odontectomy of two second maxillary bicuspids, and TADs. The total treatment time was 41 months.

Keywords: TAD (Temporary Anchorage Device); Power arm; Translation; Power thread; Third Newton Law; Odontectomy; Regional acceleratory phenomenon; TM disfunction; Anterior repositioning splint; Protrusive appliance; Closing coil spring; Elastomeric chain; Retainer.

Conflict of Interest: None

*This article has been peer reviewed

Introduction:

Skeletal hyper-divergence:

Traits: long lower face, dolichocephalic, high mandibular plane angle, skeletal open bite,and clockwise grower. The cause of hyper-divergence during development of the individual may have been the following:

1. Mouth breathing due to soft tissue dysfunction (enlarged adenoids, tonsils, allergies, nasal obstruction)

2. Incorrect tongue position

3. Tethered oral tissue (tongue and lip tie)

4. Poor oral positions (lips apart, tongue is not resting on the palate)

5. Adverse swallowing patterns

6. Thumb and finger sucking

7. Genetics (only 10%)

The treatment is multifactorial. The first line of action is to eliminate detrimental habits, render the airway patent, implement orofacial and myofunctional therapy, high pull head gear, occlusal bite blocks, repulsing magnets, and TADs for intrusion of maxillary molars. Finally, if there is crowding, the odontectomy of selected posterior teeth would be considered. In extreme cases, orthognathic surgery may be the only solution.1

Dental Crowding:

This is a condition where all teeth do not fit into dental arches. They may be misaligned, rotated, impacted, or ectopically erupted. Causes are narrow arches, habits, premature exfoliation of deciduous teeth, the odontectomy of deciduous teeth, supernumerary teeth, and tooth decay. Treatment depends on a careful analysis and treatment planning for the orthodontic patient. We may create space to alleviate crowding by transverse development of dental arches, distalization of posterior teeth, mesialization of anterior teeth, proclination of anterior teeth, airrotor slenderizing (IPR) and in severe cases, the odontectomy of a selected tooth or teeth.2

4

Featured*

Prognathism

Prognathism is a positional relationship of the mandible and maxilla to the skeletal base, where either jaw protrudes beyond the predetermined imaginary line in the coronal plane (frontal plane) of the skull. Prognathism in humans can be due to normal variation among phenotypes. In the human population where it is not the norm, it may be due to a malformation, the result of an injury, a disease state, or a hereditary condition. 3 In disease states, maxillary prognathism is associated with Crouzon syndrome, Down syndrome, and Cornelia de Lange syndrome.4 Treatment of the mild and moderate maxillary prognathism is orthodontics in combination with surgical plates and TADs. However, the severe true maxillary prognathism requires orthodontic therapy and orthognathic surgery.

Dento-alveolar protrusion is a positional relationship of the alveolar process and anterior teeth to the skeletal base. Not all dento-alveolar protrusions are anomalous, and significant differences can be observed between different ethnic groups. Harmful habits such as thumb sucking, tongue thrusting, and lip biting can result in or exaggerate dento-alveolar protrusion, which causes teeth to misalign. The combination of oro-facial myofunctional therapy, habit breaker, functional appliances, fixed orthodontic treatment, and lifetime retention is required for a successful outcome.

“Gummy Smile”5

It is an appearance, which frequently precipitates a visit (or referral) to an orthodontic clinician. Teenagers (mostly females) may become very concerned about the appearance of their smile. Some of them may even become shy or introverted. A recent survey suggests that 37% - 47% of people say that the first thing that they notice when meeting someone is their smile. If there is more than 2 mm of exposed gingival display during the posed (dynamic) smile, it is considered a “gummy smile.” This condition is quite common. It is found in 10.5% - 29% of the population and it is more common in females. Etiology of “gummy smile” can be multifactorial and therefore must be accurately diagnosed to render the appropriate treatment.

The factors that contribute to the “gummy smile” include:

1. Hypertrophic gingiva

2. Altered passive eruption

3. Excessive incisal wear

4. Short upper lip

5. Lip hypermobility, overactive upper lip muscles, which lift the maxillary lip upward (levator labii superioris and levator anguli oris)

6. Vertical maxillary dento-alveolar excess

7. Habitual mouth breathing

Treatment must be addressed to the etiology of “gummy smile.” The following are some of the options:2

1. Altered passive eruption and Hypertrophic gingivagingivectomy

2. Excessive incisal wear - Crown lengthening and full crown coverage

3. Short upper lip – surgical lip repositioning. This surgical procedure restricts the muscle pull of elevator lip muscles, therefore reducing the gingival display while smiling.

4. Hypermobility – Botulinum Toxin injections, Hyaluronic acid

injections, lip fillers or “gummy tuck.” This surgical procedure involves removal of a small strip of tissue from the inside of the upper lip and the lip is sutured into new lower position.

5. Vertical maxillary dento-alveolar excess – orthodontic treatment, or alternatively, orthodontic treatment with orthognathic surgery

6. Habitual mouth breathing – polysomnogram, evaluation the cause of airway obstruction and appropriate therapy

Some patients have more than one contributing factor; therefore, the treatment must be managed appropriately.

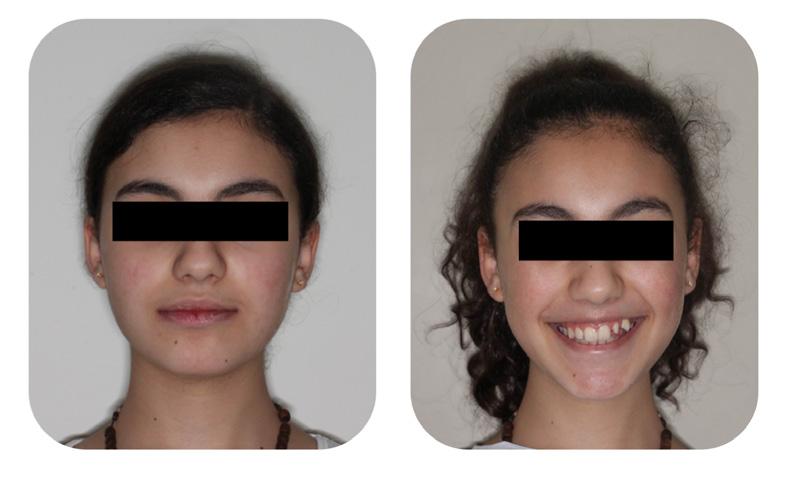

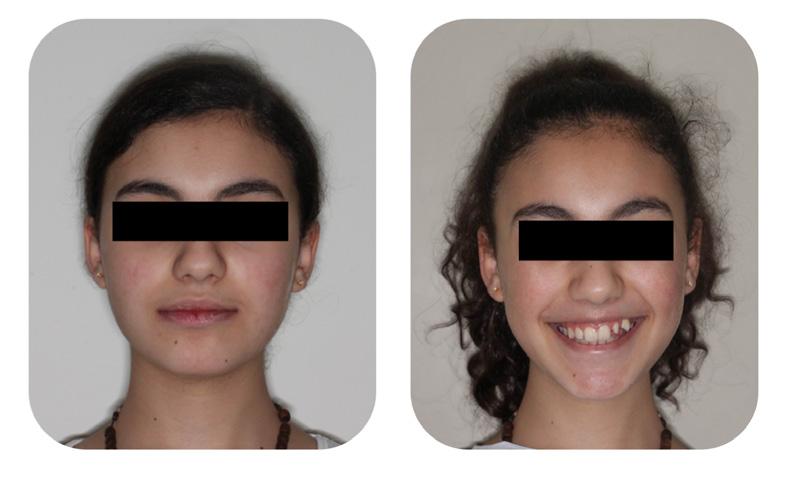

The Case

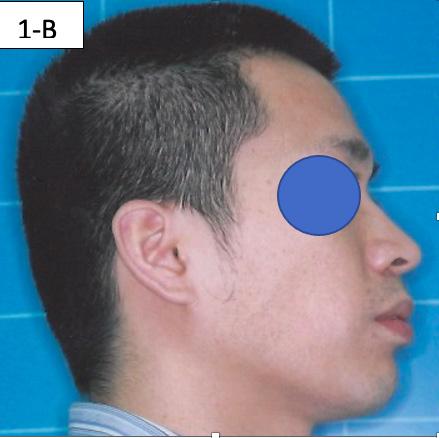

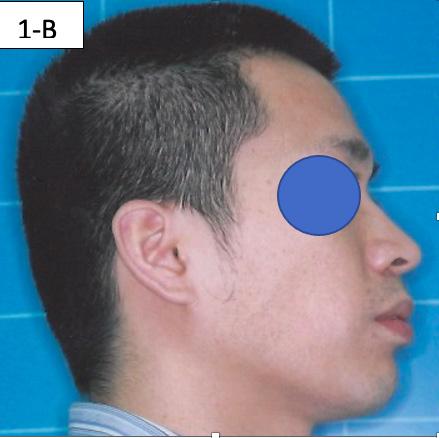

An Asian male (A. B.), aged 31 years, presented to our office with the following complaints: “I do not like my teeth. I cannot close my lips. My jaw hurts. I sleep with an open mouth. I snore at night.”

Anamnesis

The patient’s medical history reveals allergy to dust and mites, clenching, grinding, and snoring at night. The patient reported TMJ discomfort and a habitual mouth breathing. He was sucking his thumb until age six. Concerning dental history, the patient had good oral hygiene, a moderate number of restorations, generalized Tetracycline stain and failing porcelain veneers on maxillary anterior teeth.

Examination

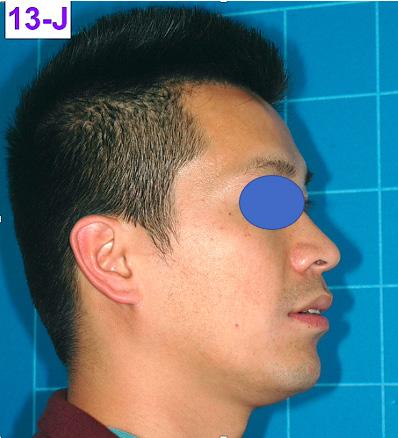

Clinical Macro-esthetic appraisal revealed normal facial symmetry, slightly longer lower face height and prognathic profile. The patient’s upper (+5.0 mm) and lower lip (+8.0 mm) were convex in relation to the “S” line (Steiner), and they were incompetent (Figure 1-A, B, C).

Clinical appraisal of patient’s posture was significant: the frontal view revealed head straight and a high right shoulder, while the lateral view revealed the head in straight position (Figure 1-D, E).

FIG 1A: Pre-treatment, frontal view

FIG 1B: Pre-treatment, lateral view

FIG 1C: Pre-treatment posed smile

FIG 1D: Pre-treatment, posture, frontal view

FIG 1E: Pre-treatment, posture, lateral view

5 5

Clinical Mini-esthetic appraisal revealed full upper and lower lips incompetent and incongruent smile arc to the lower lip. The patient’s posed smile revealed positive buccal corridors and adequate tooth display at lips in repose. (Figure 2-A, B, C).

FIG. 2A: Pre-treatment, lips together

FIG. 2B: Pre-treatment, lips in repose

FIG. 2C: Pre-treatment posed smile

Clinical appraisal of the Airway revealed a patent airway; lower airway -15/18 mm, oropharynx - Mallampati II -III, nasopharynxvery patent (Figure 3-A, B, C).

FIG. 4A: Pre-treatment, frontal view

FIG. 4B: Pre-treatment, right lateral view

FIG. 4C: Pre-treatment, left lateral view

FIG. 4D: Pre-treatment, maxilla, occlusal view

FIG. 4E: Mandible occlusal view

FIG. 4F: Pre-treatment, OB and OJ

TMJ Appraisal:

FIG.3A: Pre-treatment, lower airway

FIG. 3B: Pre-treatment, oropharynx

FIG. 3C: Pre-treatment nasopharynx

Clinical dental appraisal revealed full Angle Class II molar and cuspid relationship. The arches were wide and there was a moderate crowding. The patient had 9.0 mm overjet and 6.0 mm overbite. However, the patient reported SDB symptoms, and he also presented with symptoms and signs of TM dysfunction (Figure 4A, B, C, D, E, F))

Clinical Micro-esthetic appraisal revealed signs of attrition and abrasion. Periodontal health was good, and the patient was devoid of tooth decay. However, there was a moderate number of restorations, generalized Tetracycline stain and failing porcelain veneers on the maxillary anterior teeth.

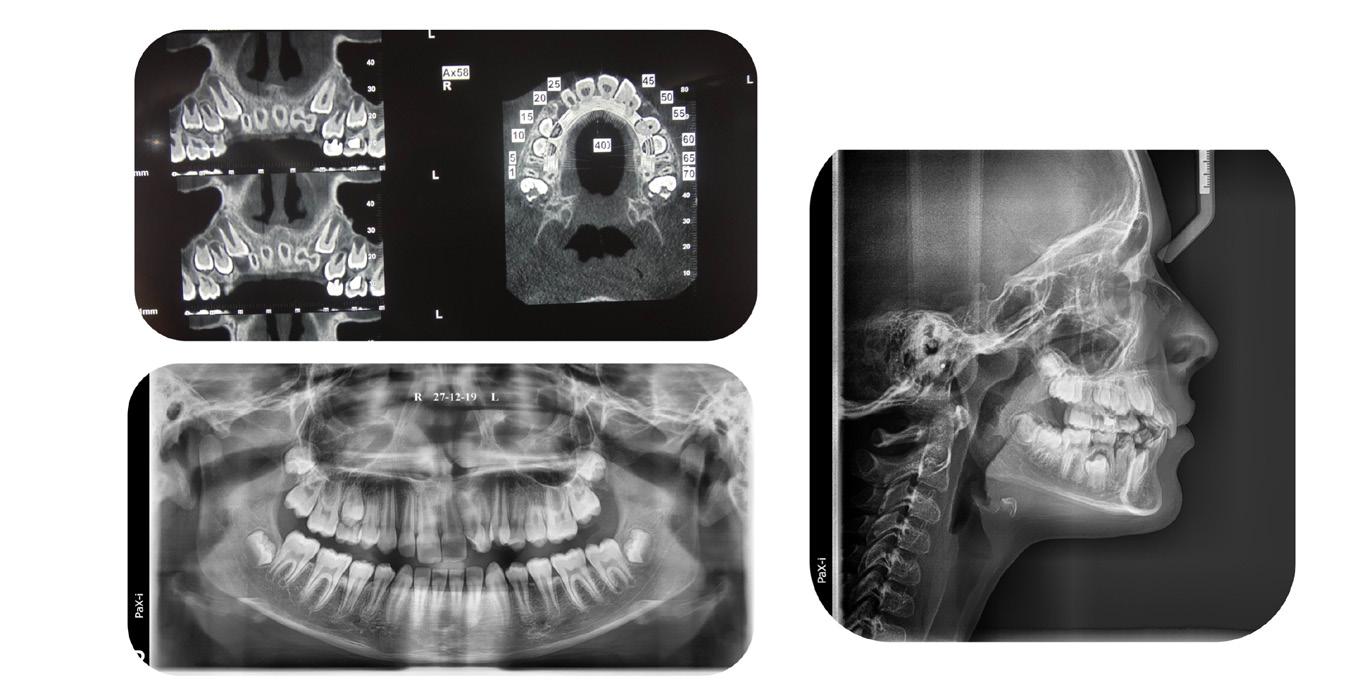

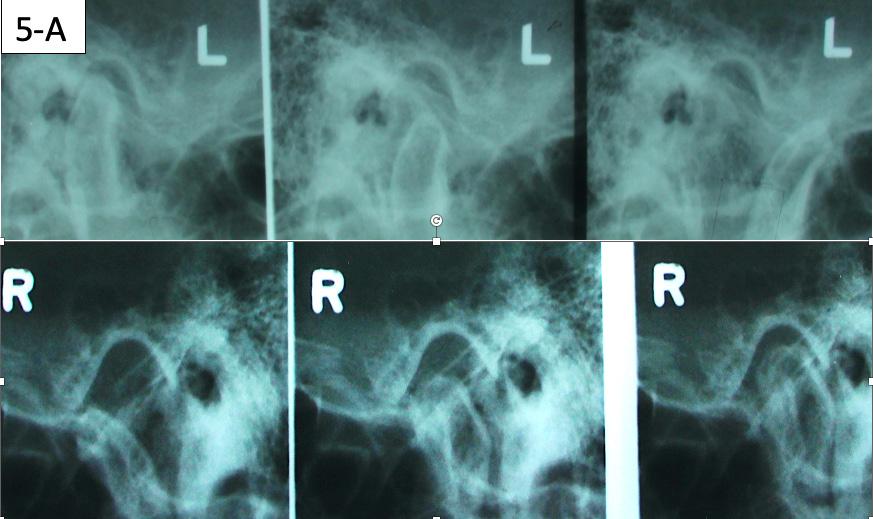

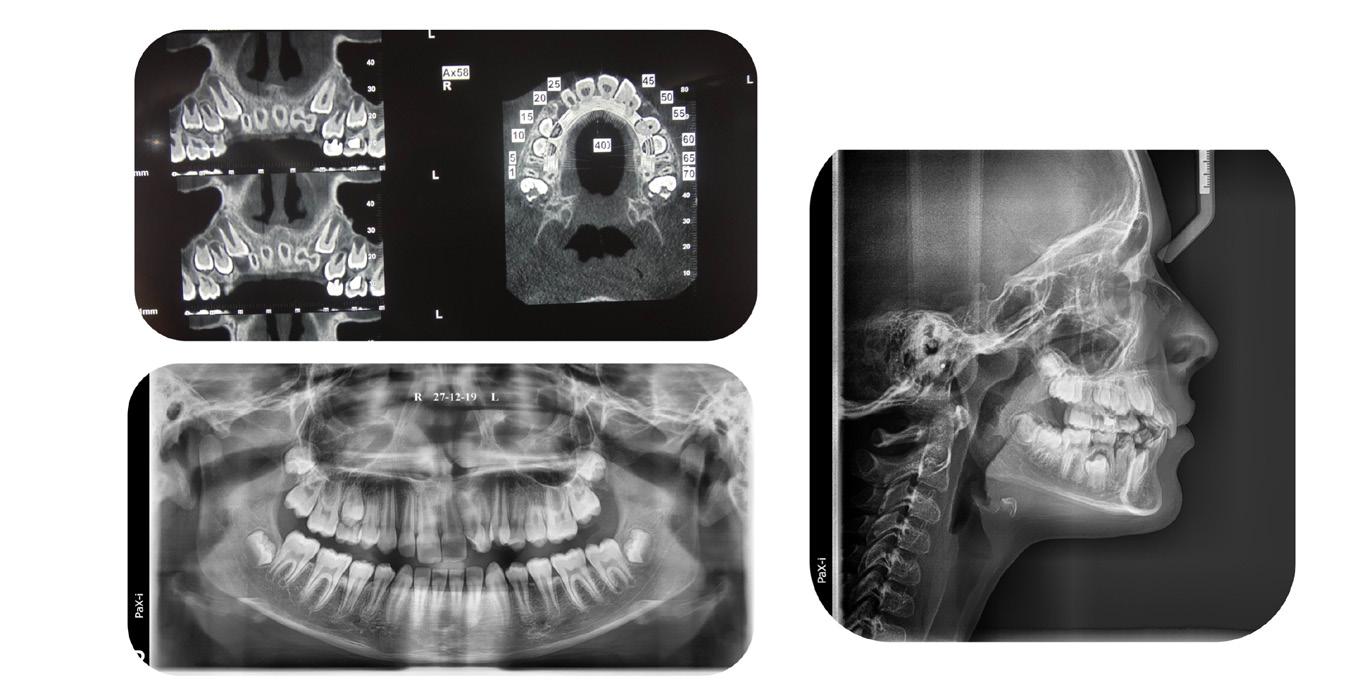

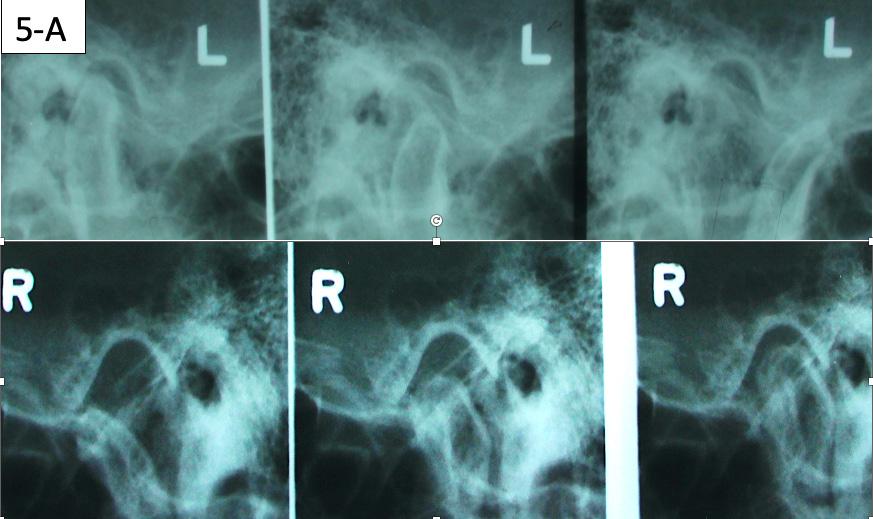

The patient had the following: migraine headaches, sore teeth upon awakening, buzzing in his ears, teeth clenching and grinding, joints locking when opened wide, popping, and clicking, pain and problems sleeping soundly. He had normal range of motion, deviation to the right on opening, clicking, The patient also had a sensitivity to palpation on the right TMJ, Posterior neck left, Trapezius left and Anterior digastric bilaterally. The transcranial TMJ radiogram reveals posteriorly displaced condyles and limited maximum opening on the right side (Figure 5-A).

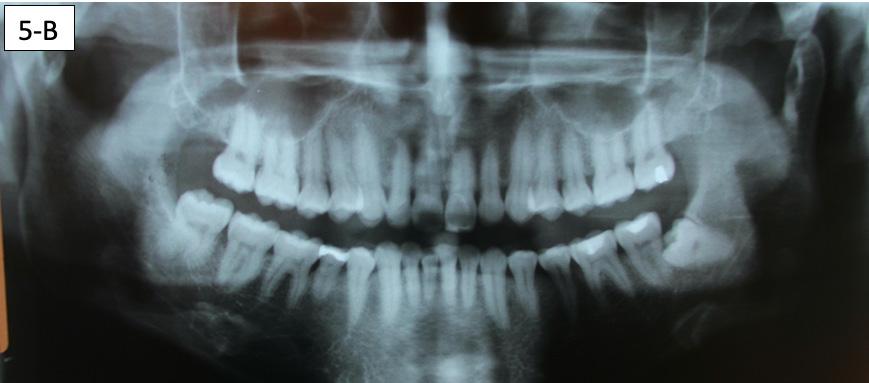

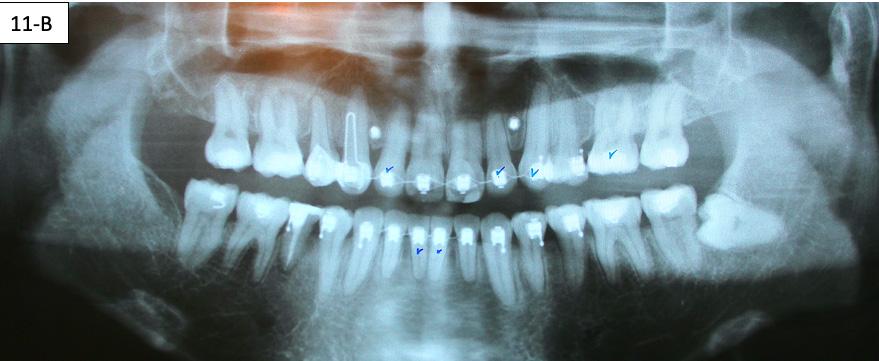

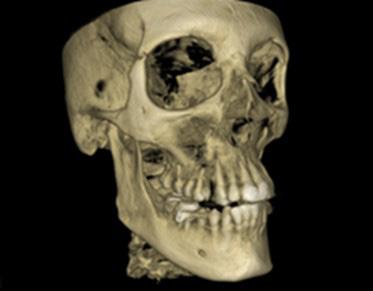

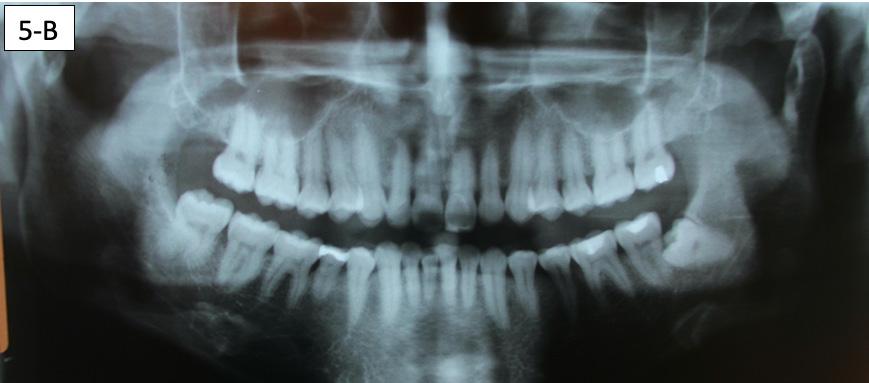

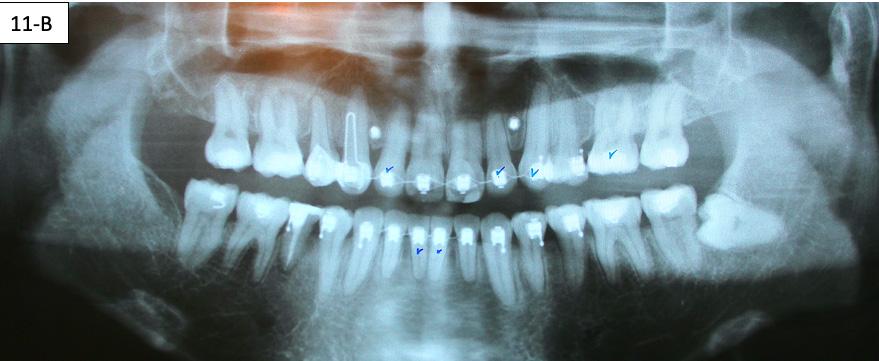

Panoramic radiogram revealed complete permanent dentition with mandibular left impacted wisdom tooth. Roots of the mandibular second bicuspids appeared to be short. There was an excellent bone support and no sign of periodontal or periapical pathology. (Figure 5-B).

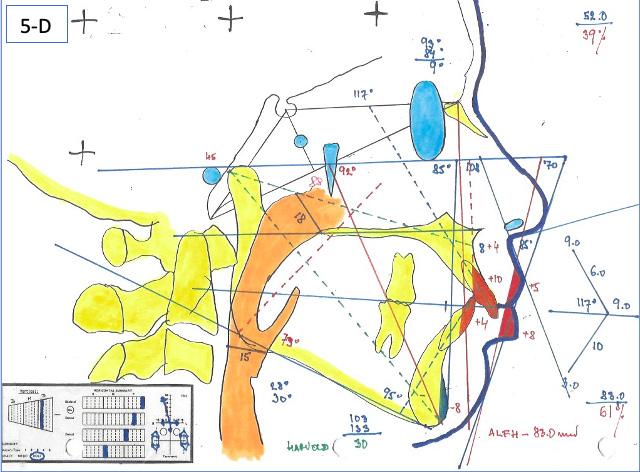

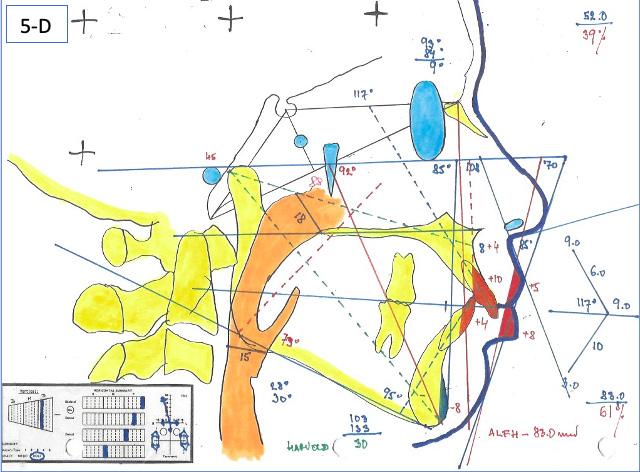

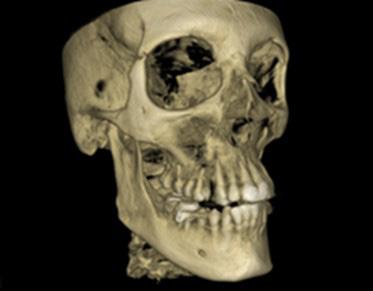

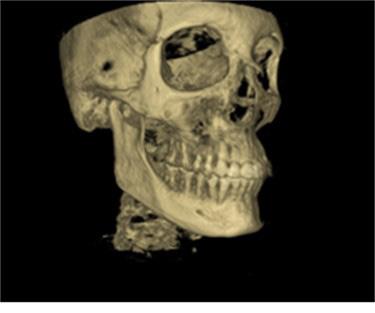

Lateral Cephalometric radiogram and tracing revealed robust lower airway (18.0/15mm), CVMS 6, maxilla and mandible are prognathic (SNA - 93° and SNB - 84°), Class II skeletal (ANB –9.0 mm, Witts – 9.0 mm). The patient was hyperdivergent (NS/ GoM – 30°, ALFH - 83 mm!!), protrusive maxillary incisors (U1/ SN – 117.0°), mandibular incisors were within the norm (L1/GoM 95.0°) and Harvold Δ was 30 mm. The soft tissue profile (lips) was convex (Figure 5-C, D).

Diagnosis

The patient exhibited skeletal Class II with mild hyperdivergent tendency, slightly prognathic profile, Angle Class II, division I, with moderately crowded maxillary and mandibular arches. The patient had 9.0 mm over-jet, 6.0 mm overbite and maxillary incisors were protrusive and mandibular incisors were within the norm. The patient exhibited slight “gummy smile” because of the combination of mouth breathing, short upper lip, and vertical maxillary dento-alveolar excess. The soft tissue profile

6

FIG. 5A: Pre-treatment, TMJ radiogram

FIG. 5B: Pre-treatment, Panoramic radiogram

FIG. 5C: Pre-treatment, Cephalometric radiogram

FIG. 5D: Pre-treatment,Cephalometric tracing

was convex. There were signs and symptoms of TM dysfunction -Internal derangement, posteriorly displaced condyles, early reciprocal click, disc displacement with reduction and limited excursion on the right condyle. The patient was a habitual mouth breather with incompetent lips.

Treatment Plan

The author proposed construction and placement of a mandibular anterior repositioning splint – in therapeutic position, where the signs and symptoms would be minimal. The time frame is 3 to 6 months. The second stage – forced eruption of the mandibular posterior teeth, followed by Straight Wire Appliance, odontectomy of #15(4) and # 25(13), placement of TADs, retraction of the maxillary anterior teeth, protraction of the maxillary molars. The third stage – placement of TADs distally to #12(7) and #22(10) and intrusion of the maxillary anterior sextant. The fourth stage – bonded and removable retainers.

Results

Maxillary and mandibular impressions were taken in irreversible hydrocolloid impression material. Both TMJ discs were recaptured in the Phonetic bite,6 which was recorded with the PVS bite recording material (Blue Bite). The therapeutic splint was fabricated, tried, inserted, and verified that the displaced discs were recaptured. This splint must be worn 24/7, except brushing the teeth, eating and sports (6-A, B, C, D, E).

FIG. 6A: Phonetic bite

FIG. 6B: Therapeutic splint

FIG. 6C: Splint in situ, frontal view

FIG. 6D: Splint in situ, right lateral view

FIG. 6E: Splint in situ, left lateral view

After the patient became accustomed wearing the splint, the acrylic was cut off distally to #46(30) and #36(19). A band was cemented on #17(2), #16(3) and #27(15), #26(14) and brackets/ tubes were bonded on #15(4), #25(13), #37(18), and #47(31). A 016 SS sectional wire was inserted in the maxilla bilaterally from the second molar to the second bicuspid and a ¼” - 4.5 oz elastics were placed for forced eruption of the mandibular second molars (Figure 7-A, B).

When the mandibular second molars became in contact with the maxillary molars, the acrylic was hollowed out from the intaglio of the splint above #46(30) and #36(19). Two ¼” –4.5 oz triangular elastics were placed for forced eruption of the mandibular first and second molars (Figure 7-C, D).

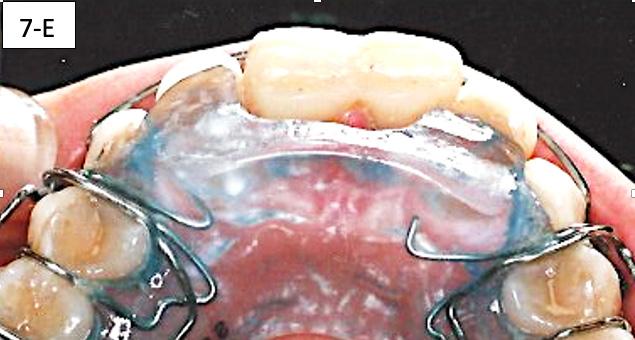

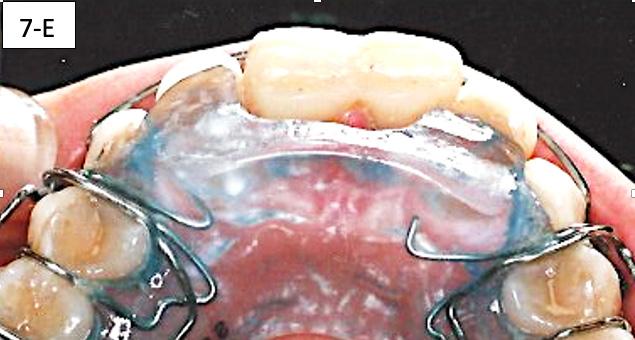

After the mandibular second molars became firmly in contact with the maxillary molars, a Maxillary removable protrusive appliance (Twin block II) with hooks was inserted to maintain the therapeutic position with the recaptured disks. Also, composite build-up was bonded to the lingual surface of #11(8) and #21(9), to maintain the mandible in the same position. Three ¼” – 4.5 oz triangular elastics were placed for forced eruption of the mandibular first molars and bicuspids. Separators were placed between the mandibular molars and bicuspids to speed up the elevation of the posterior sextants (figure 7-E, F, G).

The TMJ signs and symptoms have improved, therefore, the next step was to address the chief concerns of the patient, lip incompetence, maxillary incisor protrusion and gunny smile. The

7 7

author decided on odontectomy of #15(4) and #25(13), retraction of the maxillary anterior sextant and protraction of the maxillary molars. The intrusion of the maxillary anterior teeth would follow with the assistance of TADs.

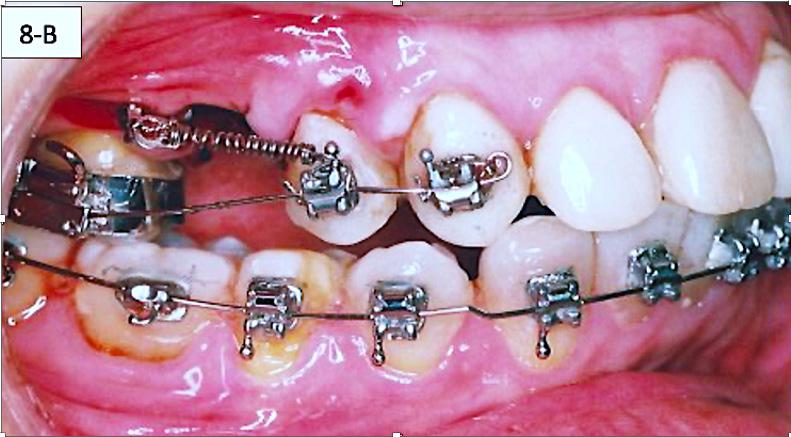

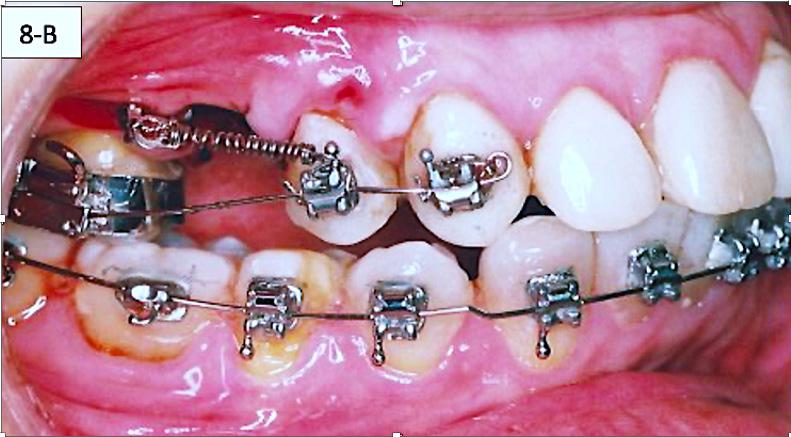

The brackets were bonded on maxillary cuspids, bicuspids and mandibular anterior teeth followed by placement of a 014 SS sectional wire in the maxilla and a .014 SS arch wire in the mandible. Maxillary second bicuspids were extracted, and a 1.6 x 8.0 mm AncorPro (OrthoOrganizers) TADs were inserted just mesially to the first molars. Closing coil springs were attached from the TADs to the first bicuspids (Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon) (Figure 8-A, B, C).7

The brackets were bonded on the maxillary incisors and there was a progression of the arch wires a .014 NiTi, a .016 SS and a .018 SS. The progression of the arch wires in the mandible was a .016 NiTi, a .016 SS, a .018 SS and a .018 x 025 SS with the step-down distally to the cuspids. A 1.6 x 8.0 mm Ancor Pro TADs were inserted on the buccal aspect distally to the maxillary lateral incisors to aid the intrusion of the maxillary anterior sextant.8 Maxillary incisors were laced back, to prevent splaying during the intrusion and two links of an elastomeric chain were attached from the TADs to the arch wire. Power arms were bent from a .016 x 022 SS wire and ligature tied to the bracket #13(6) an #24(12).

Closing coil springs were attached from TADs to the power arms. To prevent an undesirable labial moment (flaring) of the maxillary incisors, Class I (labial intra) elastics (¼” – 4.5 oz) were

FIG. 7A: Forced eruption of #47(31)

FIG. 7B: Forced eruption of #37(18)

FIG. 7C: Forced eruption of #36(19) & #37(18)

FIG. 7D: Forced eruption #46(30) & #47(31)

FIG. 7E: Protrusive appliance and composite build-ups

FIG. 7F: Forced eruption of mandibular posterior sextants

FIG. 7G: Forced eruption of mandibular posterior sextants

placed from the buccal hook of the maxillary first molar to the helical loop on the arch wire. The helical loop was fabricated just distally to the maxillary lateral incisors on a. 018 SS arch wire (Figure 8-D, E, F, G).

Posterior TADs were removed, when interdigitations of the maxillary cuspids and first bicuspids was achieved, we initiated the protraction of the first molars. Commercial laboratory soldered buccal power arms to the orthodontic bands on #16(3) and #26(14). These power arms allowed us to apply the force close to the center of resistance of the first molars. The TADs inserted distally to maxillary second incisors previously, served two purposes: intrusion of the anterior sextant and protraction of the maxillary first molars. The applied force was delivered with an Elastomeric chain. To prevent excoriation of the attached gingiva a .018 x .025 hand bent tissue shield was bonded to the buccal surface of #13(6) (Figure 9-A, B, C, D).

The side effect of protraction of the first molars is a mesiolingual moment (rotation). To neutralize this, the force must be applied, from the palatal aspect with the Power thread or the Elastomeric chain. The Power thread is attached to the lingual cleat of the molar bands, and it is stretched to the maximum, then tied to the arch wire between the cuspids and lateral incisors. A 3/16” – 4.5 oz Class III elastic was placed on the right side and a ¼”4.5 oz triangular elastic was placed on the left side to ameliorate the interdigitation (Figure 10-A, B, C).

FIG. 8A: Odontectomy of #15(4) & # 25(13)

FIG. 8B: CCS and TAD, right lateral view

FIG. 8C: CCS and TAD, left lateral view

FIG. 8D: TADs inserted, frontal view

FIG. 8E: TADs in situ, radiogram

FIG. 8F: Class I elastic, right lateral view

FIG. 8G: FClass I elastic, left lateral view

8

9A: Soldered power arms

FIG. 9B: Excoriation of the

Pre-de-bracketing appraisal

Pre-de-bracketing records comprise of the facial photographs, intra-oral photographs, panoramic radiogram, and study casts. After the prudent appraisal of the bracket position, root angulation, occlusion, lips in repose, posed smile and maxillary incisor display, numerous teeth were re-bracketed. We also evaluated the improvement of the signs and symptoms of the TM dysfunction.

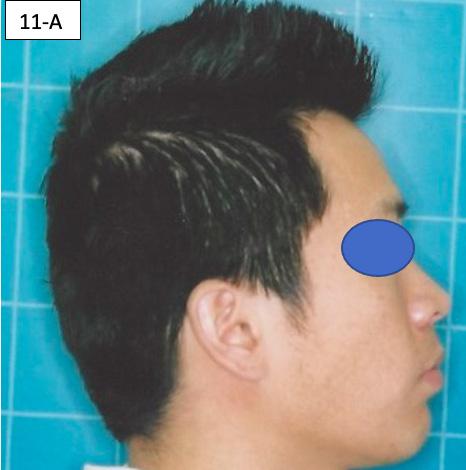

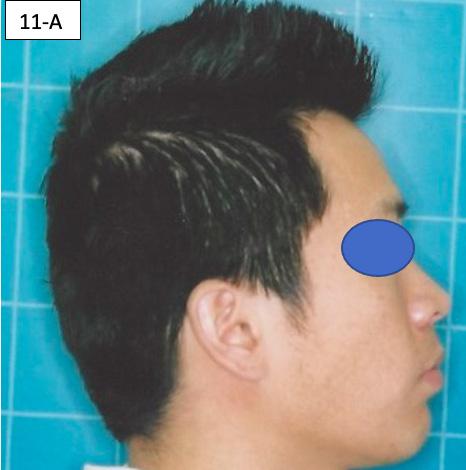

After re-bracketing, the treatment continued with the progression of the arch wires: a .014 NiTi, a .018 NiTi, a .019x025 “V” Force -3 and the final arch wire a .018x.025 SS. These final arch wires were left for three months. After this time, the esthetics, TMJ, airway, occlusion and alignment were evaluated. The patient reported that he was satisfied, and very happy with the result (Figure 11-A, B, C, D, E, F).9

Countdown on retention

One month before de-bracketing, when everyone was satisfied and the patient had a .018 x .025 SS arch wire in the maxilla and the mandible, we appointed the patient for “Countdown on retention.” The TAD’s and Tissue guard were removed and the full arch wire was left in the maxilla. However, in the mandible, it was

11A: Pre-debracketing, lateral view

11B: Pre-de-bracketing, panoramic radiogram

FIG. 11C: Pre-de-bracketing, lips in repose

FIG. 11D: Pre-debracketing, posed smile

FIG. 11E: Pre-debracketing, right lateral view

FIG. 11F: Pre-debracketing, left lateral view

cut and bent in, just distally to the cuspids. Also, two 3/8” – 2.5 oz. elastics were placed, in a letter “W” with tail configuration, for one month. They were zig-zagged from the maxillary cuspids and finished on the mandibular molars and had a slightly protrusive line of action on the mandible (Figure 12 - A, B).10

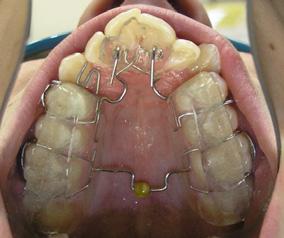

Retention

The retainers comprised of a maxillary wrap around QCM retainer with a flat pad in premaxilla to dis-occlude the posterior sextants. This also serves as an anterior deprogrammer. Also, there was inserted a bonded retainer #43(27) to #33(22). The mandibular bonded retainer was made of a .0215 flexible spiral (braided) wire, and bonded with Unitec Bond 1, and Tetric Evo (Ivoclar). The patient was instructed to wear her QCM retainer 24/7 (except sports, brushing his teeth and meals) for 12 months, and after this, only at night. The bonded mandibular retainer was recommended to stay indefinitely.

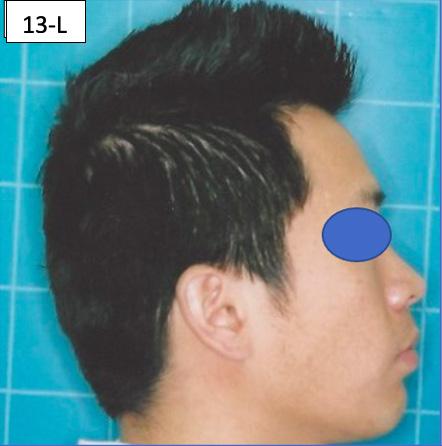

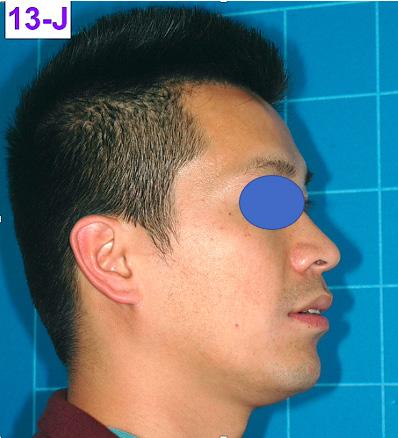

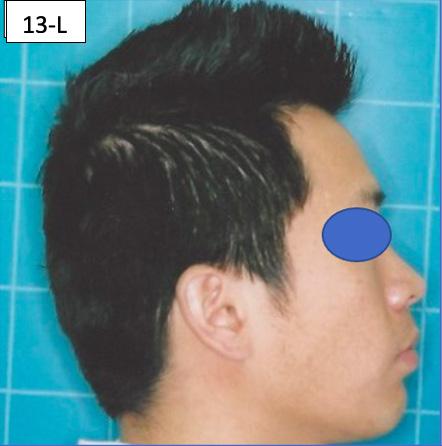

Please view the post-treatment images at the time of insertion of the retainers (Figure 13 – A, B, C. D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L).

Six months after the de-bracketing, the patient requested replacement of his eight deteriorating porcelain veneers in the maxillary arch (Figure 14 – A).

9 9

FIG.

oral mucosa

FIG. 9C: Tissue guard, right lateral view

FIG. 9D: Protraction of the first molar, left lateral view

FIG. 10A: Lingual intra – Power thread, occlusal view

FIG. 10B: Class II elastic, right lateral view

FIG. 10C: Triangular elastic, left lateral view

FIG.

FIG.

FIG. 12A: “W” with tail, right lateral view

FIG. 12B: “W” with tail, left lateral view

FIG. 13A: Post-treatment, fontal view

FIG. 13B: Post treatment, right lateral view

FIG. 13C: Post-treatment, left lateral view

FIG. 13D: Post-treatment, maxilla, occlusal view

FIG. 13E: Post-treatment, mandible, occlusal view

FIG. 13F: Maxillary QCM retainer

FIG. 13G: Post-treatment, lips in repose

Fig. 13H: Post-treatment, posed smile

Fig. 13I: Post-treatment, fontal view

Fig. 13J: Post treatment, lateral view

Fig. 13K: Post-treatment, posed smile Text

Fig 13L: Post-treatment, profile

Fig. 15A: Post-treatment, Cephalometric radiogram

Fig. 15B: Post-treatment, Panoramic radiogram

Fig. 15C: Post-treatment, Cephalometric tracing

Fig.15D: Cephalometric superimposition

Table 1: Panoramic and Cephalometric radiograms, and Midsagittal Cephalometric Analysis

10

FIG. 14A: Bonded porcelain veneers, frontal view

Discussion

This orthodontic case involved several functional and esthetic concerns. Of chief concern were:

1. Incompetent lips and protrusive maxillary incisors

2. Short upper lip, vertical maxillary excess and gummy smile

3. Prognathic maxilla

4. Class II division 1 malocclusion

In addition to these problems, the patient presented with habitual mouth breathing and several signs and symptoms of TM dysfunction. He exhibited hyperdivergence. The patient’s lips were severely convex related to the “S” line (Steiner) and incompetent.

Although the treatment was a lengthy one (41 months), our outcome was favourable. The patient was finished with a skeletal class II, and Angle Class I cuspid and a Class II molar relationship with minimal overjet and overbite. ANB improved from 9° to 7°however, Wits improved from 9.0 mm to 5.0 mm. ALFH decreased by 4.0 mm due to the odontectomy of maxillary second bicuspids, which caused favourable autorotation of the mandible. This happened despite forced eruption of mandibular posterior sextants during the TMJ therapy.

The position of the anterior teeth was less favourable, U1/SN 117° to 124°, L1/GoM 95° to 99°. The Naso-labial angle improved to the ideal value from 85° to 102°. The Facial axis (Growth axis –Ricketts) changed to a more ideal value, from 88° to 91°, due to the odontectomy of two maxillary second bicuspids. The soft tissue profile was convex (lips to S line – Steiner) and improved considerably: from +5/+8 to +3/+3.

The final panoramic radiogram reveals impacted mandibular left wisdom tooth, minimal root resorption and acceptable angulation except for #22(10), where the root remained mesially oriented. Root canal therapy was done on the tooth #45(29), because it developed purulent pulpitis during the orthodontic treatment.

Concerning the finishing and esthetics, the patient expressed great satisfaction with the outcome, and we felt the occlusion was acceptable. Therefore, we agreed to end the treatment.

To summarize, the authors presented a case encompassing numerous clinical abnormalities that required a variety of treatment techniques.

The problem list included:

1. Incompetent lips and protrusive maxillary incisors

2. Short upper lip, vertical maxillary excess and gummy smile

3. Prognathic maxilla

4. Class II division 1 malocclusion

5. TM dysfunction

6. Hyper-divergence

7. Habitual mouth breathing

The treatment involved:

1. Placement of TMJ mandibular therapeutic splint

2. Forced eruption of mandibular posterior sextants

3. Placement of maxillary protrusive appliance

4. Straight Wire Appliance

5. Odontectomy of maxillary second bicuspids

6. Placement of TADs

7. Retraction and alignment of the maxillary cuspids and first bicuspids

8. Protraction and alignment of maxillary molars

9. Finishing the case

10.Retention

In conclusion, this case, offered us several opportunities. Firstly, we were excited to be challenged by such a diverse and significant set of problems. Then, it was motivational to apply a varied and unique set of orthodontic techniques towards those clinical concerns. Thirdly, we were able to watch our plan progress towards achieving a successful result. The greatest satisfaction, however, was the gleam from this young man’s greatly enhanced smile when our treatment ended.

References

1. Rasool G, Bibi T, Hasseb ulah Khan M. Comparison of dento-alveolar heights in relation to vertical facial pattern. JKCD, December 2016, Vol.7, No. 1

2. Johal A.S., Battegel J.M., Dental Crowding: comparison of three methods of assessment. European Journal of Orthodontics, 19 (1997) 543-551

3. www.Medline Plus, Medical Encyclopedia

4. Winter R.M: “Cor nelia de Lange syndrome,” J. Med. Genet., 1986;23:188

5. Mahardawi B., Wongsirichat N., Gummy smile: A Review of Etiology, Manifestations and Treatment, Siriraj Medical Journal, 2019, 71(2):168-174

6. Olmos S., Airway Centered Dentistry: (The A, B, Cs of Treatment for Chronic Face Pain/OSA and Closing Anterior Open bite Without Ortho), Oral Health, March (2017) 44-56

7. Teng G.Y.Y., Liou E.J.W., Interdental osteotomies induce Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon and accelerate tooth movement. Journal of Oral and Maxillo-facial Surgery, January 2014, 72-1, Pages 19 -29

8. Palencar A.J., Molar distalization with the assistance of Temporary Anchorage Devices. International Journal of Orthodontics, Spring 2015, Vol. 26, No. 1

9. Palencar A.J., Treatment of Prognathic Maxilla with Dento-alveolar Protrusion in Adult with Assistance of TADs: A Case Study, International Journal of Orthodontics, Spring 2019, Vol. 30,

10. Alexander R.C., The Alexander Discipline, 1986, Batavia IL, Quintessence Publishing, Pages 431 – 432

11 11

Growing Beautiful Teeth

Chapter 7: Max the Maxilla

Estie Bav is an active member and senior instructor of IAO. She graduated BDSc from the University of Western Australia, and practises in her own private family dental surgery in Melbourne Australia. In November 2018 she published her first book titled “Growing Beautiful Teeth,” primarily targeting parents, grandparents, teachers or any child health carer to look out for early signs of dental growth issues. It informs the unaware the importance and impact of teeth and jaw on other areas of health such as breathing, sleep, posture, and even behaviour.

Currently the dental profession tends to “supervise and wait” for growth issues to become complex and expensive to correct….”

“My concern is that most parents miss out on basic and important dento-facial growth information until too late.”

The book was designed to be a helpful resource for your patient to read, and for introducing the subject to younger dentists and allied health professionals who may not be familiar with the teeth-occlusion-airway-TMJ-sleep paradigm.

Her message is to get involved with a child’s dento-facialairway development early.

Growing Beautiful Teeth is available from any major online booksellers, or at

• www.drestiebav.com

• www.growingbeautifulteeth.com

She can be reached at estie@drestiebav.com

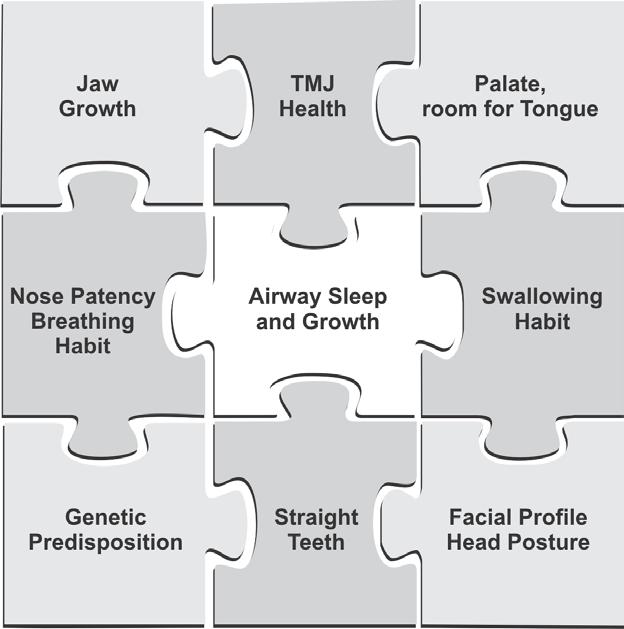

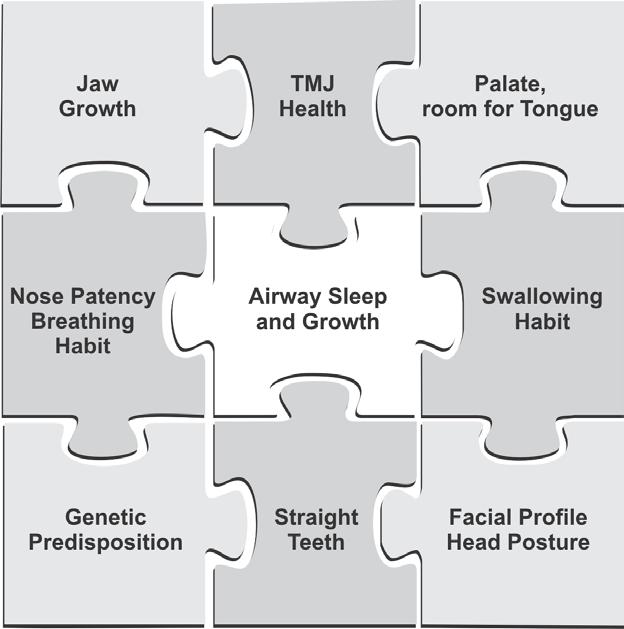

Having read through all the chapters up to here, you will by now understand how important it is to ensure that your child’s jaws develop correctly. Generally, jaw growth deficiency lies in the upper jaw, the Maxilla.

Good Reasons for Maximizing the Maxilla

1. To provide plenty of room for future permanent teeth to align and to lessen the need for any tooth extraction.

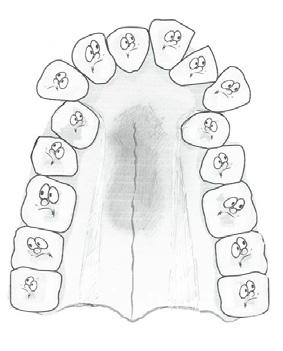

2. To have a beautiful and broad smile. When teeth are removed and/or dental arches are small, the results are often dark buccal corridors that detract from a smile. Wide dental arches will fill the smile with teeth displayed from one corner of the mouth to the other.

3. To accommodate the tongue. Often the tongue is too big for the mouth. You cannot shrink the tongue but you can develop the maxilla to accommodate it.

4. To not constrain but allow the mandible to develop forward during growth. Compression in the TMJs must be avoided to reduce the risk of TMD.

How my book can be helpful….

It takes time to educate parents on the benefits of treating dental growth issues early and explaining what signs we look for. In writing this book in simple language I hope to bring an awareness to the larger parent community, which will in turn save my dental colleagues chairside time. This book would be a helpful resource for the waiting room, and for introducing the concept to younger colleagues joining your practice.

12

EXCERPT

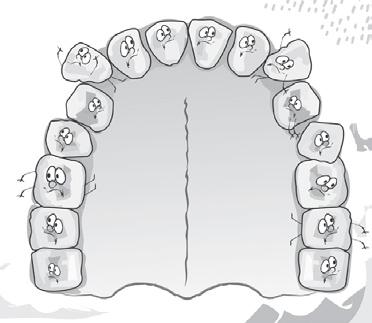

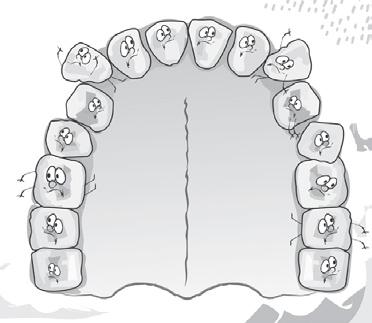

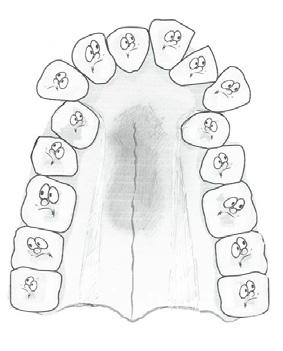

Arch too short and flattened… Arch too narrow and tapered… Happy arch….room for everyone

Buccal corridor: dark unfilled space caused by a narrow arch and typically tooth extractions Contrast with this gorgeous smile set in a broad dental arch

The mother has a broader smile. We suspect the daughter may have a narrower palate and dental arches.

small maxilla traps the mandible, like a car being trapped when the garage is not large enough (garage door over closes)

!!

A

Do not constrain

Fig 29: Undersized arch causes tooth crowding.

Fig 30: Broad and narrow smiles.

Fig 31: Do not constrain the mandible

5. To support a wide nasal cavity which facilitates airflow and nasal breathing.

6. To develop a balanced and attractive facial profile by allowing nature to put the lower jaw where it needs to go as the head and midface grow forward.

and When We Need Them

By the age of seven years or even earlier as necessary, the child can have x-rays of the head and jaw taken. Dentists use these to analyse the direction that the jaws, face and teeth are growing.

The two useful ones are the orthopantomogram (OPG) also known as panoramic x-rays of the head, and the lateral cephalogram (or ‘lat ceph’) which are both 2D imaging.

The OPG will show if any teeth may be congenitally missing or if there may be supernumerary teeth present. These are extra teeth above the number that we normally have. It also helps detect any upper canines that may be at risk of being impacted (stuck) due to an undersized maxilla and shortage of space.

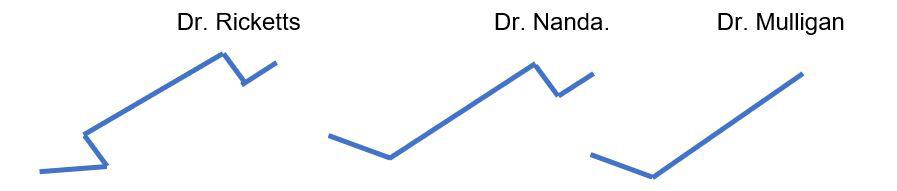

The lateral cephalogram which captures the side view of the head and facial profile can be traced, measured, and analysed to assess the direction of the child’s growth in this area. This analysis is called a cephalometric analysis. The measurements are made in relation to a frame of references and compared to a set of average values. There are many analyses taught and used. The ideal ones measure the relative position of the jaws against the base of the cranium to give us a guide to the position of the maxilla. As we have discussed it is important to know if the maxilla may be set back too far and growth guidance therapy may need to be initiated.

There is a new digital 3D imaging known as cone-beam volumetric tomographs (CBVT) which can provide 3D views of the cranium, jaw and teeth. As more of this type of x-ray equipment is developed and released on the market, they will provide improved quality images with lower exposure to x-rays as well as at a lower cost for the patients. CBVT, due to their 3D imaging capability, are particularly helpful for studying the jaw joints, the nasal cavities, sinuses and the airway at the back of the throat.

There are many methods used by dentists to help develop the maxilla, but below are some common ones.

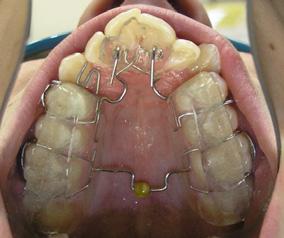

‘Expanding’ Appliances

If the maxilla needs to be expanded, or as I prefer the term ‘developed’, then the dentist will prescribe dental or oral appliances (also referred to as ‘plates’) which are customised to fit the child’s mouth.

The appliance is made to fit inside the palate of the child and this is to be worn for several months. These plates usually will have some screws or springs as components that need to be turned or ‘activated’ every few days. This activation expands the plate, which in turn will press and stimulate the maxilla to develop in the direction that we wish to gain extra growth in. For this reason, they are often known as orthopaedic appliances because they remodel or expand the bony structures to reshape the palate, and prepare and create space for the adult teeth to grow into.

There are myriads of expansion appliances designed by dentists over the years and used to achieve the orthopaedic changes required.

Broadly speaking, the appliance needs to be worn full-time (24/7) for the activation to work satisfactorily and efficiently without relapses.

Removable Appliances have the advantage of being able to be removed for hygiene. However, their correct use will require good compliance by the child and good support and supervision by the parents.

They are removed from the mouth only for cleaning purposes and for activation. As the plate is widened, so will the maxilla as it is gently nudged along. In my experience, the younger patients are usually the most cooperative or adaptive to wearing these appliances. I have made appliances for patients as young as 4 years old with great results.

13 13

Before maxilla expansion

After maxilla expansion

Fig 32: Facial profile improved after maxilla expanHead X-rays: Why

OPG or panoramic scan

Lateral Cephalogram

Ceph’ analysis

Fig 33: OPG and lateral ceph x-rays.

various appliances to max the maxilla

Fig 34: Appliances

Fixed Appliances are bonded to selected teeth and cannot be removed during the whole duration of treatment. They have the advantage of staying inside the mouth full-time for improved and controlled activation. However, mouth and teeth hygiene during the use of these appliances can be a challenge as they cannot be taken out for cleaning. Fortunately, these days new dental hygiene tools such as air or water jet spray cleaners are available and help make the task easier.

Forward-pull Face Mask

The forward-pull face mask, also referred to as a ‘reversed’ head gear, is a frame that fits around the child’s face and provides the attachments for elastic bands to protract the maxilla forward. It is used in conjunction with a palate expansion appliance and is worn mostly during the evening and night. Please be aware that this is not the usual headgear that we commonly see teenagers wear to retract their upper teeth backwards, against growth.

Forward-pull face mask are used in the very young for maximum effectiveness. Ideally, they are prescribed for those between 4–6 years old because that is when bones are very adaptable, and again to nip growth issues at the bud. Despite its appearance, I find that young kids are cooperative with wearing a forward-pull mask, especially when the parents are helpful in supervising its proper use.

Orthognathic Surgery

These are surgical techniques to treat a young adult when growth is finished (typically in the late teens), or later. Parts of the upper or lower jaw or both may be sectioned and moved to correct shape, dimension and alignment.

Again, there are pros and cons which, like all surgical treatment, need to be fully understood and taken into consideration by the patient and parents. This procedure may be avoided if growth problems are picked up and intercepted early.

Twotypesofforwardpullface mask,orreversedheadgear

Two types of forward pull face mask, or reversed headgear

We refer to the group of related issues such as mouth breathing, poor muscle tone or aberrant tongue habits that contribute to the structural deficiency as functional issues and these obviously cannot be ignored. For the best outcomes, treatment maximising the maxilla structure will need to be accompanied by various functional therapy either before, during or after the maxilla development.

There can be some confusion with the term ‘functional’ in this area of dentistry. Note that a ‘functional appliance’ can also refer to an oral appliance that is prescribed for a child with a retracted mandible that needs to grow more forward (once the maxilla has been expanded). Some common removable functional appliances include the Twin Blocks, Bionator and the Biobloc III.

Orofacial Myology

Orofacial Myology (OFM) or Oral Myofunctional Therapy (OMT) are health disciplines that are involved with training the muscles of the jaws and mouth for optimal functioning, and correcting aberrant tongue habits.

Just as orthopaedic surgery treating other parts of the body calls upon physiotherapy and exercises to promote healing, dentofacial orthopaedic changes such as maxilla development or orthodontics will be more effective when the associated muscles are retrained to function optimally as well.

OFM is a natural and essential part of guiding a child’s growth for a beautiful and healthy set of teeth, jaws, head, face and airway.

I first heard of OFM in the late 1980s when Dr John Mew, a British orthodontist (specialist) and founder of the orthotropic premise, came out from the UK to teach his techniques to a handful of general dentists here in Melbourne. He stressed that for an effective treatment outcome, there is a need for the patient to learn to keep their mouth closed and tongue properly postured.

Dr Mew wrote an amazing book titled Biobloc Therapy about his treatment philosophy and maxilla expansion technique – ‘the thoughts that initiated it, the research that founded it and the clinical work that developed it …’ – and each time I pick up the book to read, I feel enormous admiration for and inspiration from his wisdom and passion on the subject.

OFM was such an unknown subject back then and, for many years to follow, few dentists understood why or how to apply any of these exercises for the benefit of their patients.

Fortunately, this important subject has now gained wider recognition, and education in this area is gaining momentum and included in many worthwhile dental health symposium programs around the world. There are, however, too few dedicated OFM therapists in Australia currently.1

Typically, an oral myofunctional therapist (OMT) may be a speech pathologist, or a dental therapist or hygienist who has undergone further training in the subject. Dentists and osteo- or chiro-practitioners also undertake such training to learn how to detect unhelpful muscle patterns and habits that may interfere with jaw expansion treatment, and how appropriate exercises can be included as part of the therapy for their patients.

A course of dedicated OM Therapy may run for a few weeks. Ideally, they should be introduced to complement a course of dentofacial growth guidance and breathing retraining. These exercises aim to achieve the Big 3 as discussed earlier. I have noticed that some progressive ENT surgeons are also including OMT as part of their patient care. We should not be surprised because to improve breathing and airway issues, patients must use the muscles of the face and mouth correctly.

Role of Genetics

Are small maxilla and/or retruded mandible inherited? Parents often comment that the poor child takes after one of the parents

14

Fig 35: Face Mask. Functional Issues

and erroneously believe that nothing can be done to correct the situation.

Although genetic influence does play a role (especially in the Class III strong mandible pattern and the Class II Division 2 short maxilla pattern), we can see that there are many ‘environmental’ influences that are within the control of the parents to deal with, to redirect the child’s growth in the right direction.

So, one may ask what is causing this avalanche of relative underdevelopment of the upper jaw in our modern world? There are several theories offered by dentists, anthropologists, biologists and their published books are certainly well worth reading.2,3,4,5 The consensus points to mouth breathing, poor airway and sleep, poor use of orofacial muscles and making the wrong food choice. We are selecting to eat more processed foods, and this includes baby formula for infants. These types of food are often made to be eaten fast and easily without involving much chewing effort, and often with no consideration for the nutritious content.

An analogy is a child who never had to walk or to exercise the legs but was carried everywhere. The child’s leg muscles would atrophy. As we no longer eat harder and tougher foods, our orofacial muscles are not properly used and the skeletal structures they connect to do not develop as they should.

Orthodontic Teeth Alignment

Once optimal dentofacial growth has been achieved and functional issues controlled, then usually the permanent teeth will come out perfectly with no need for further treatment as nature intended.

However, sometimes it may be desirable at this stage for the young adult to have the teeth alignment idealised and this is where braces or newer techniques such as clear aligners can be used. These are treatment techniques that can fine-tune the alignment, the inclination, and/or rotation of the individual tooth. Orthodontists are especially skilled in this phase of therapy.

Adjunct Complementary Therapy

I have also found that treatment provided to my patient by osteopaths and/or chiro- practitioners who specialise in the fields of the cranium and jaw can enhance my treatment outcome for the child. These practitioners take care of the neural system to ensure good connectivity between the various parts of the body that impact on the growing dentofacial structures.

The conclusion is that your dentist and practitioners from various health disciplines must collaborate to treat the child as a whole patient, and not just the teeth, for a successful outcome.

Burnout?

Parents often ask me, ‘Is my child too young for treatment, or will my child get burnt out if we start at such a young age?’ This thought is often also used as a criticism from opponents to the philosophy of treating early. My opinion based on observation of my patients is that treating the young is a lot easier, because the problem is not so ingrained. The child is still growing and the skeletal structure is adaptable. As we all appreciate, bad habits that are well set is much harder to undo. We certainly cannot sit and watch the child suffer from poor airway, sleep, and growth.

As mentioned before, scientific studies are increasingly finding that maximising the growth of the maxilla can help treat other significant medical conditions in children such as SDB, OSA, ear

infections and nocturnal bedwetting. Indirectly, it has also been found now that poorly developed jaws and the consequences of inadequate airway, breathing and sleep, are associated with childhood obesity, childhood behavioural and social issues, and learning issues paralleling those observed in ADHD.

It is important that for a successful treatment outcome, not only must parents be enrolled in and dedicated to helping the child grow the maxilla to the max, they must also supervise the breathing and orofacial muscle retraining (daily exercises). This is an area I often find that parents, in our modern and busy world, let us down.

What Happens When the Dental Arches Shrink?

Here I want to share with the reader the case of a young oriental adult who I was sitting next to for several days at a publishing workshop. When he heard that I was a dentist, he commented that he had just been paying big sums of money for his dental treatment. He was also suffering from TMD with clicking and painful TMJs during that conference.

I noted he had a flattened midface and a long face shape, and I said to him that perhaps his mandible and tongue are constrained by an undersized and set-back maxilla. His response was interesting. He said, ‘ah ha, that makes so much sense now because ever since I had eight teeth removed with my orthodontic treatment, to have my remaining teeth straightened, my tongue has felt cramped and uncomfortable. I hate how my tongue sits nowadays. It’s like it doesn’t know where to belong.’

Beware of the collateral unwanted outcome of losing tongue space and airway when aiming for straight teeth at all costs including extractions of perfectly sound teeth.

This young man is not alone, and his experience is in fact sadly common based on what I find in my patients who attend my practice for TMD pain treatment and occlusion rehabilitation.

Your child needs more than just straight teeth treatment must seek to improve and benefit but not affect other critical areas of the body

1. For more information, visit: Academy of Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy (AOMT) at https://aomtinfo.org/ and The Australian Association of Orofacial Myology (AOMT) at http://australianassociationoforofacialmyology.org.au/

2 WA Price, Nutrition and Physical Degeneration, Price-Pottinger, 1939

3 R Cor ruccni, How Anthropology Informs the Orthodontic Diagnosis of Malocclusion’s Causes, Edwin Mellen Press, 1999

4 A Fonder, The Dental Physician (2nd Ed.), Medical-Dental Arts, 1985

5 DE Lieber man, The Story of the Human Body, Vintage Books, 2013

15 15

Fig 36:Jig-saw of the bigger picture.

The Safety and Efficacy of Fixed Sagittal Appliance Therapy: A Clinical Survey

Stephen Deal, DDS, Crispen Simmons, DDS, Soroush Zaghi, MD

AUTHORS

Dr. Stephen Deal, DDS University of Arkansas and the University of Tennessee College of Dentistry. Since 2003, his practice emphasizes proper facial growth, orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics, TMD and Sleep Dentistry. He has completed extensive post graduate training in orthodontics, craniofacial pain, TMD and sleep. Dr. Deal has lectured internationally on the biology of facial growth and incorporating the ControlledArch System into clinical practice.

Dr. Crispen Simmons, DDS

Since graduating from the University of Tennessee Center for Health Sciences in 1977, Dr. Simmons has completed over 5000 hours of continuing dental education (advanced dental instruction). His course work has included studies of craniofacial pain, temporomandibular disorders, pain management, orthodontics, myofunctional therapy and sleep dentistry. Some of the world’s leading authorities in these fields have been his mentors.

Dr. Soroush Zaghi, MD

Dr. Zaghi is a graduate of Harvard Medical School, UCLA Otolaryngology (ENT) residency, and Stanford Sleep Surgery Fellowship. He is very active in clinical research with over 90+ peer-reviewed research journal publications and is a recognized leader on advancing standards of care for sleep-disordered breathing and tongue-tie surgery.

Abstract:

Introduction: Orthodontic/jaw orthopedic appliances have been in use for over a century and have been found to be safe and effective when used correctly. The fixed OsseoRestore™ Appliance (ORA) is a recent innovative appliance that incorporates current scientific understanding of human craniofacial growth and development. This is a clinical survey to ask practicing clinicians about the safety and efficacy of the fixed ORA.

Methods: A 15-question survey was created using SurveyMonkey software and sent to known providers of the fixed Osseo-Restore orthopedic appliance. Responses were collated and these results are reported.

Results: The most common complications reported were mouth discomfort 19.92%, tooth sensitivity 11.21%, gingival inflammation 10.43% and tongue irritation 10.29%, all common orthodontic complications. Severe complications were rare with tooth loss and tooth breakage at less than 1% and 1.36% respectively.

Discussion: Complications during and following orthodontic treatments have been well documented, and no known orthodontic therapies are without risk of undesired complications or side effects. The ORA is no exception and entails risks and benefits no different from any orthodontic/orthopedic treatments that should be weighed by providers and patients prior to implementing any treatment. Pre-existing craniofacial and oral conditions that may possibly contribute to undesirable side effects during and following treatment should be identified, discussed with the patient, and documented to ensure proper informed consent. The importance of patient selection criteria cannot be overstated when considering any recommended surgical, dental, or orthodontic therapy.

Conclusions: The ORA is a safe and effective appliance when used properly and within the biologic range of force. Like all orthodontic appliances, it has risks and benefits that should be weighed prior to treatment. These risks are well within the known complication rates of other forms of maxillary expansion. Proper patient selection criteria and critical thinking skills by the practitioner throughout treatment are essential for achieving the desired treatment responses and goals.

Conflict of Interest: None

16

been peer reviewed

*This article has

FEATURED*

Introduction:

A variety of orthodontic/jaw orthopedic appliances have been in use worldwide for well over a century and a half and, when used correctly, they have been found to be safe, efficacious and often beneficial, although not without risks and limitations in success.1 Most orthodontic/jaw orthopedic appliances currently in use have been developed by a more or less trial and error process concerned with correction or improvement of orthodontic/jaw orthopedic deficiencies presenting in the transverse, vertical, or sagittal planes. The fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance (ORA) is a recent innovative appliance that reflects the several previous decades contributions of many clinicians; and it incorporates current scientific understanding of the nature of human postnatal craniofacial growth and development.

The introduction of innovative orthodontic/jaw orthopedic systems or appliances has always been met with skepticism often followed by opposition from those with an opinion to defend. Dissenting opinions are a necessary and valuable component of scientific progress. Sometimes dissenting opinions are founded upon inadequate information or they are only opinions unsupported by facts.

There are many misconceptions regarding the biologic processes of craniofacial growth and development as well as orthodontic movement of teeth. Consider that even though all elements and nuances of tooth movement have not been described, or yet even to be conceptualized, it can be definitively stated that bone remodeling occurs in every case when teeth move through bone regardless of whether the movement is natural, therapeutic, or iatrogenic.2-6 This process is accomplished through a complex system of addition and resorption of bone in response to stress and strain within biologic limits when applied to the system. The change in tooth position is a direct result force amplitude and duration and is independent of the concept and mechanisms of growth. 2-4,6

Based upon the first principles of bone growth, remodeling, and repositioning that are extensively described in the literature, we can infer that any orthodontic device or appliance applying a force that is within the biologic range of force should do no more harm nor good than normal biologic processes.7 This means that if an appliance is placed properly, utilized as designed, and delivers forces within the biologic range of about 3,000 microstrain (µE) or less during growth or 1500 µE or less in adults, then the appliance would likely be safe for the delivery of the desired response to the teeth and bone. Biological loading regimes as provided by functional appliances may subject a bone to such strains and promote size and shape change consistent with the demands of the mechanical environment.8

Achieving the desired treatment responses and goals requires not only clinical experience but knowledge and comprehension of chosen appliance biologic mechanisms, capabilities, and limitations. Essential to the entire treatment process is the application of critical thinking skills by the practitioner throughout treatment. Any orthodontic/jaw orthopedic appliance can be misused resulting in clinical challenges. It is up to clinicians to properly utilize all tools at their disposal and adjust treatment planning when necessary; this includes orthodontic appliances of all types.

Evaluating the performance of any orthodontic appliance should obviously include the best applicable scientific analyses

but should also include the clinical experiences of practitioners who routinely utilize the appliances in question. To gather information regarding clinical experiences, a survey was created to poll practitioners specifically using the Osseo-Restore TM appliance in clinical practice.

Methods:

The authors developed a questionnaire survey utilizing SurveyMonkey software. The survey consisted of 15 questions submitted to 56 clinical dentists known to be experienced in ORA indications and management. The survey was designed to assess the safety and efficacy of the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance and to allow clear, relevant, and timely responses with the intent of increasing participation rate. The complete survey questionnaire is found in Fig.1.

1. The CBS documentary was an unfair, biased, and onesided portrayal of the safety and efficacy of the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance.

2. How many years have you been practicing dentistry?

3. How many years have you been using the fixed OsseoRestoreTM appliance?

4. How many fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliances do you administer annually?

5. Would you consider yourself an expert, intermediate, advanced or beginner when administering the fixed OsseoRestoreTM appliance?

6. The fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance is safe and effective when used in appropriately selected patient candidates.

7. Complications from the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance are possible but rare and infrequent.

8. Have you ever had a patient incur tooth loss that could be directly related to effects of the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance rather than a unrelated pre-existing condition?

9. Have you ever seen permanent damage to oral structures that you could definitively attribute solely to the use of the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance and not a pre-existing condition? If yes, please elaborate.

10.Indicate the frequency of occurrence of the following complications when administering the fixed OsseoRestoreTM appliance.

11. Rank your most common indications for treatment with the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance from most common to least common.

12.Based upon your diagnosis, what is the average maxillary development indicated when using the fixed OsseoRestoreTM appliance?

13.Indicate the frequency of occurrence of the following subjective comments made by your patients following the completion of fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance therapy?

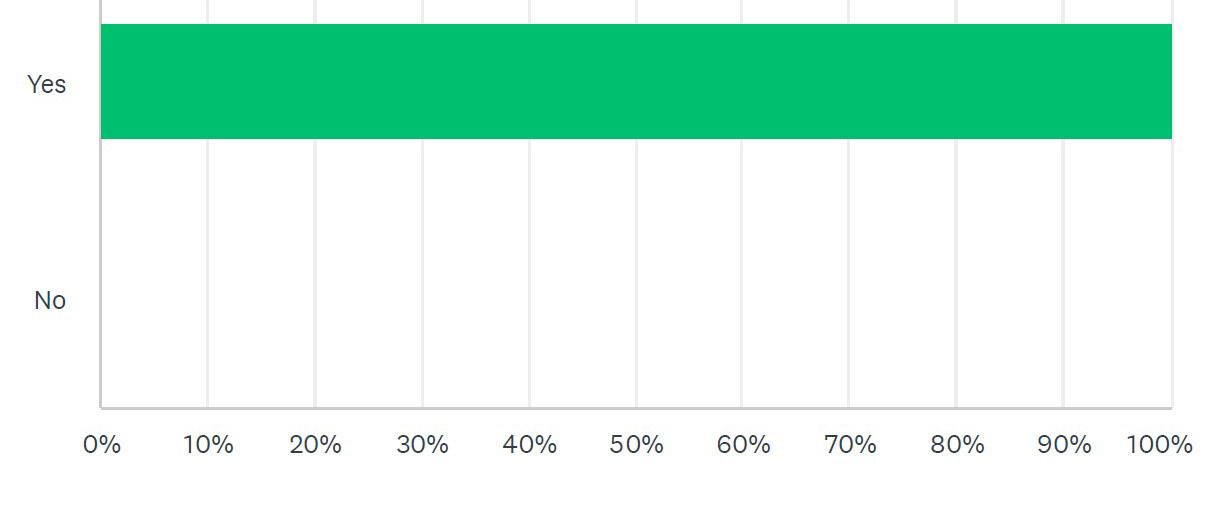

14.Do you intend to continue use of the fixed OsseoRestoreTM appliance?

15.Do you feel that the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance is safe and effective when utilizing it to treat your patients?

FIG. 1: Complete survey questionnaire

17 17

Results:

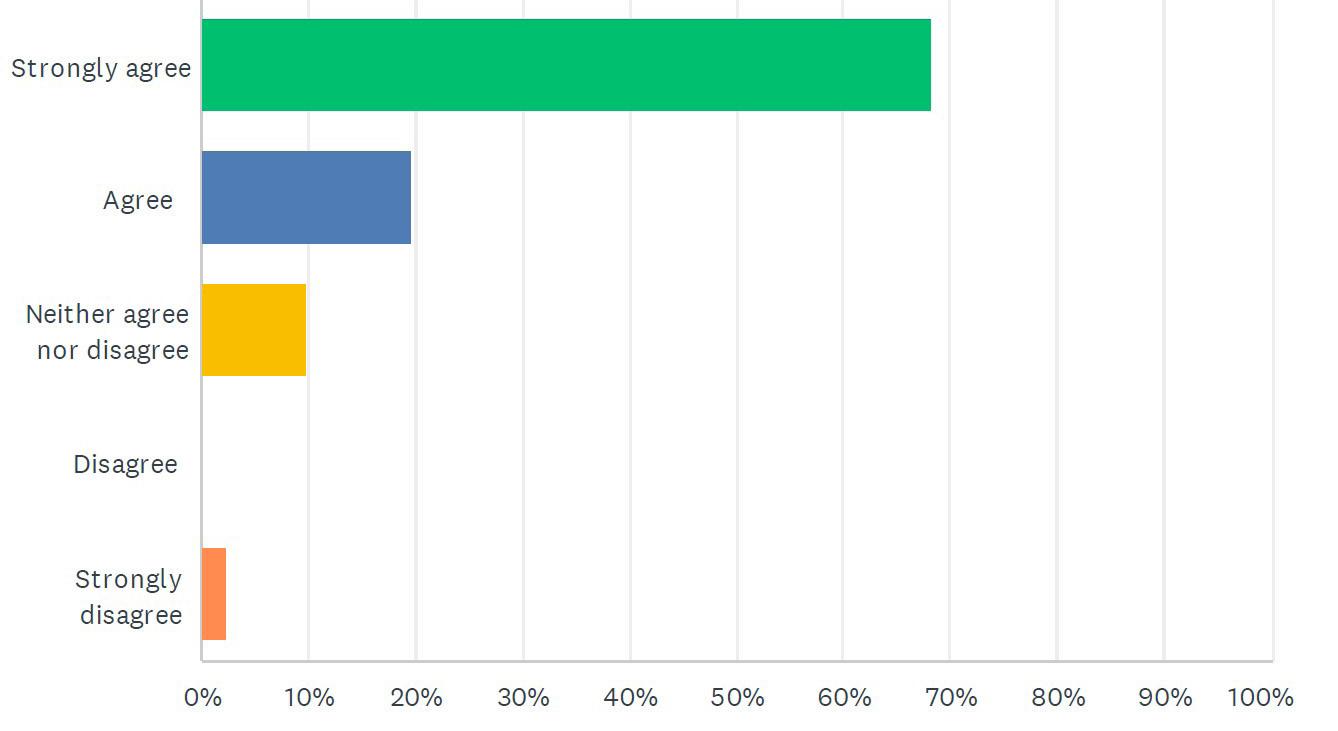

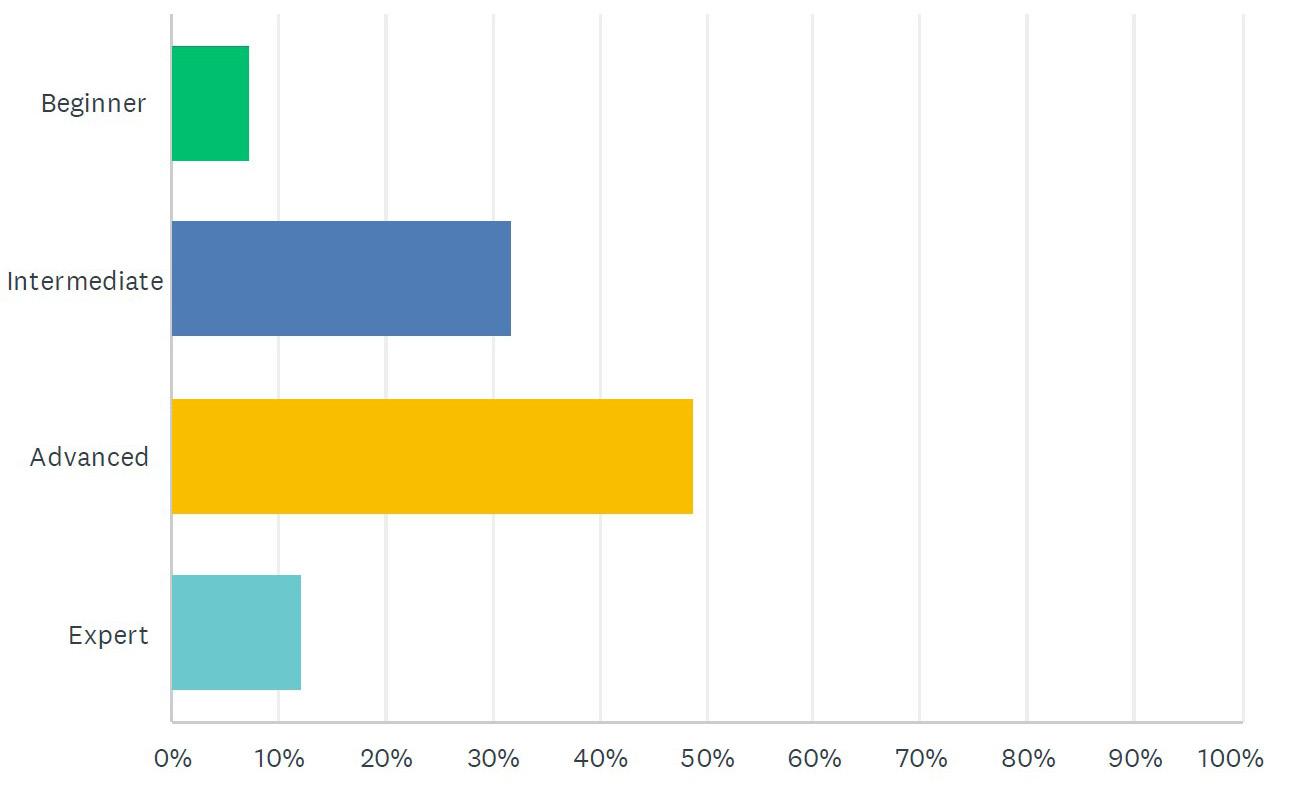

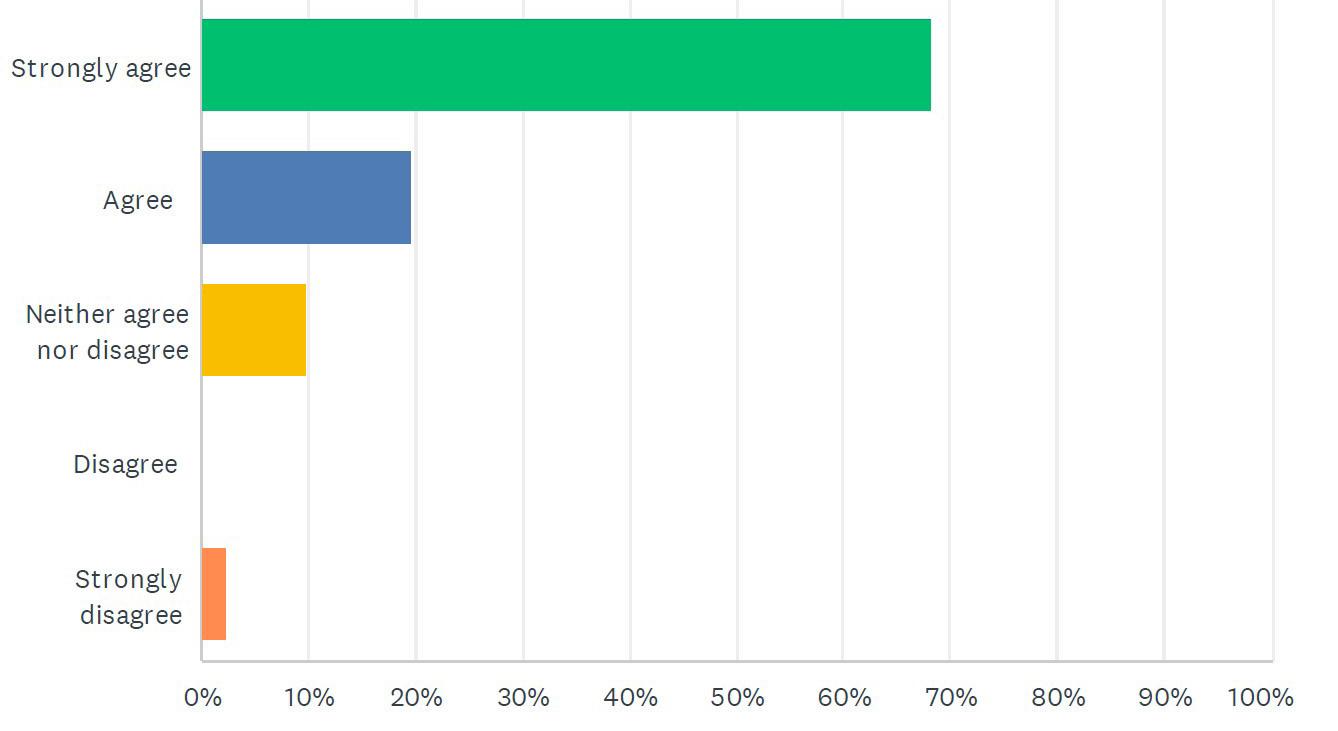

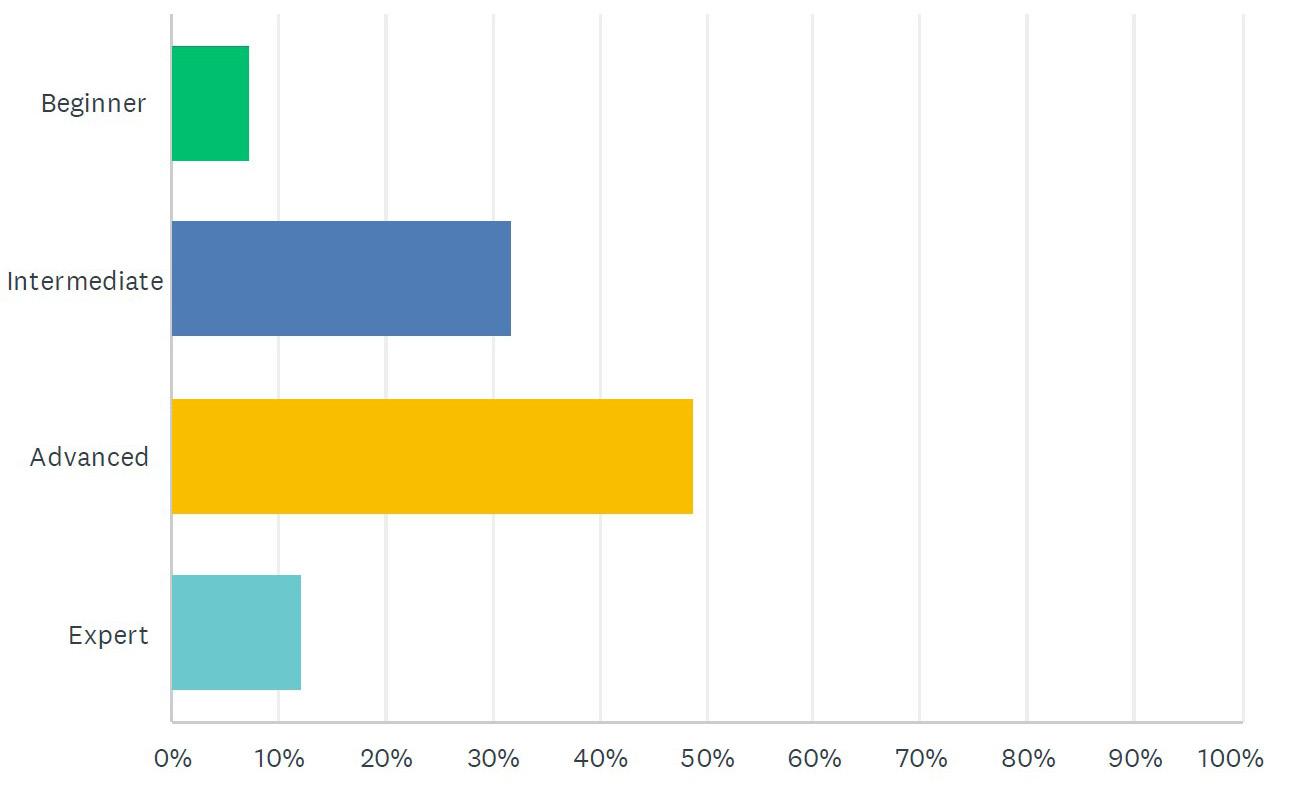

Forty-one of the 56 (41/56) practitioners surveyed responded, yielding a 73% participation rate. This is considered a good survey response rate. On average, the participants had been in practice for 25 years with a cumulative total of 1,014 years of clinical experience. Eighty-three percent of the participants prescribed between 5-80 fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliances each year. Over 60% of the respondents rated themselves as advanced/expert when administering the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance.

Questions regarding complications yielded the following responses:

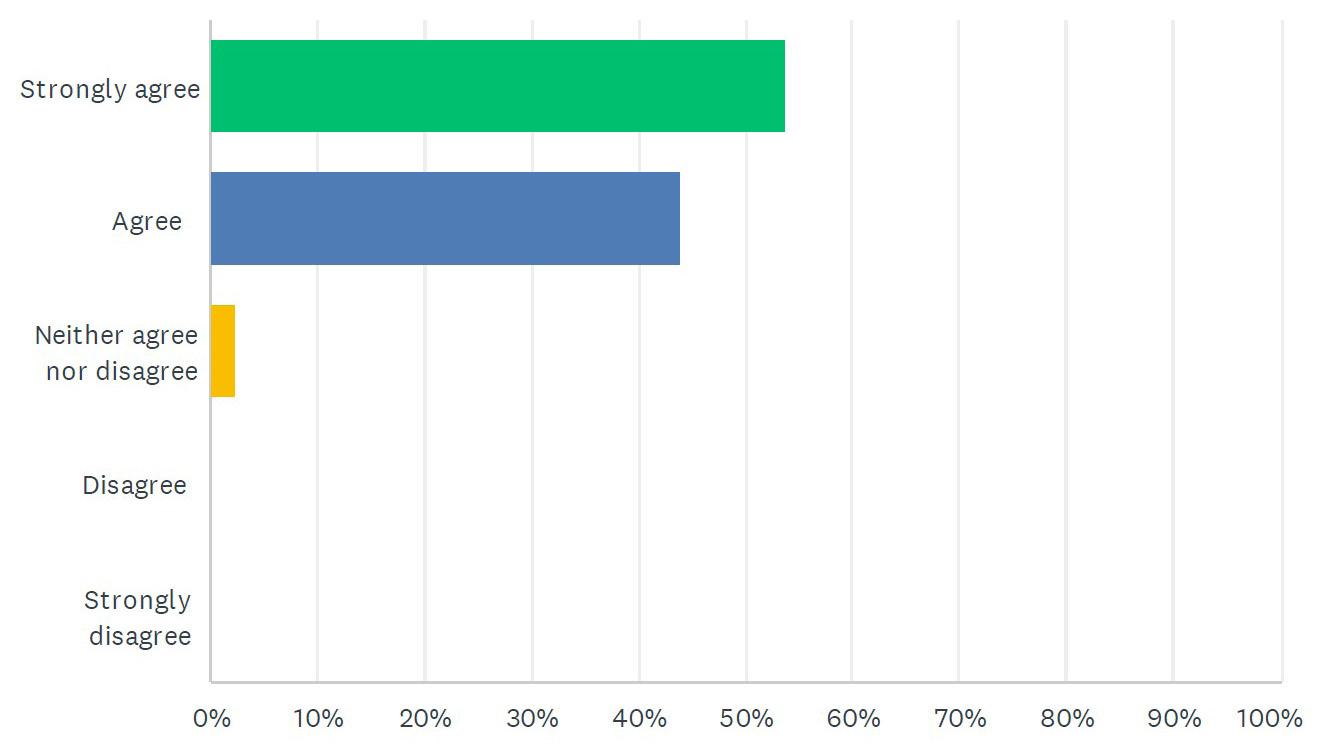

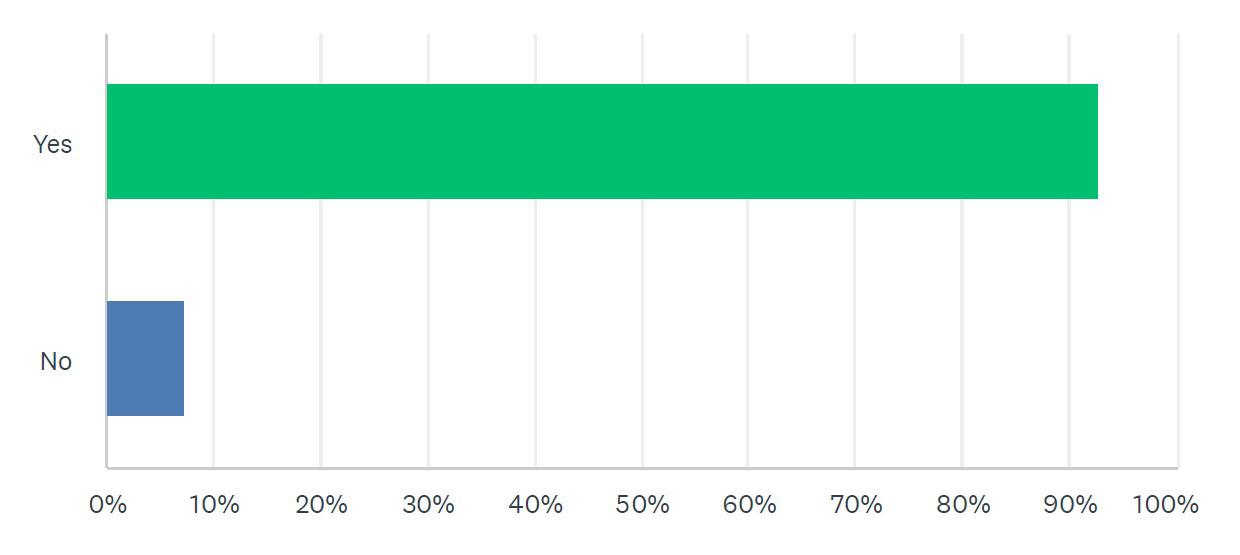

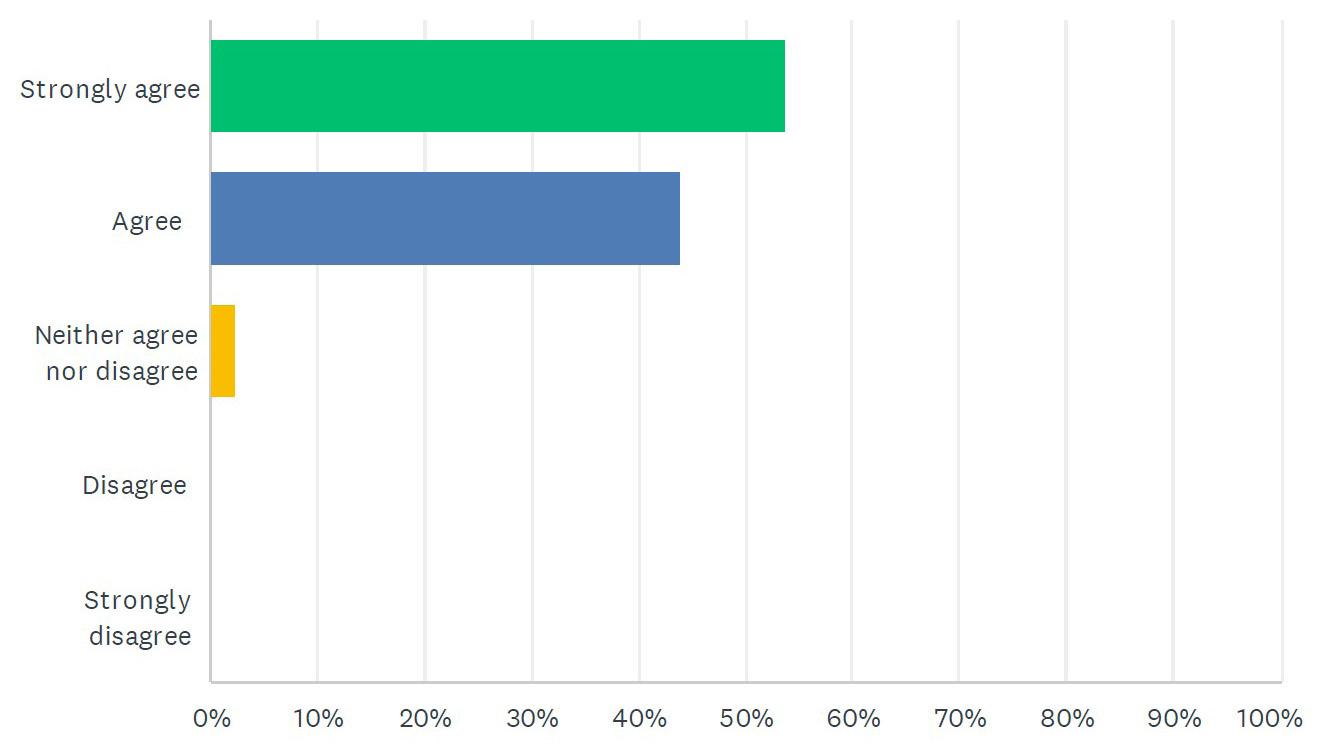

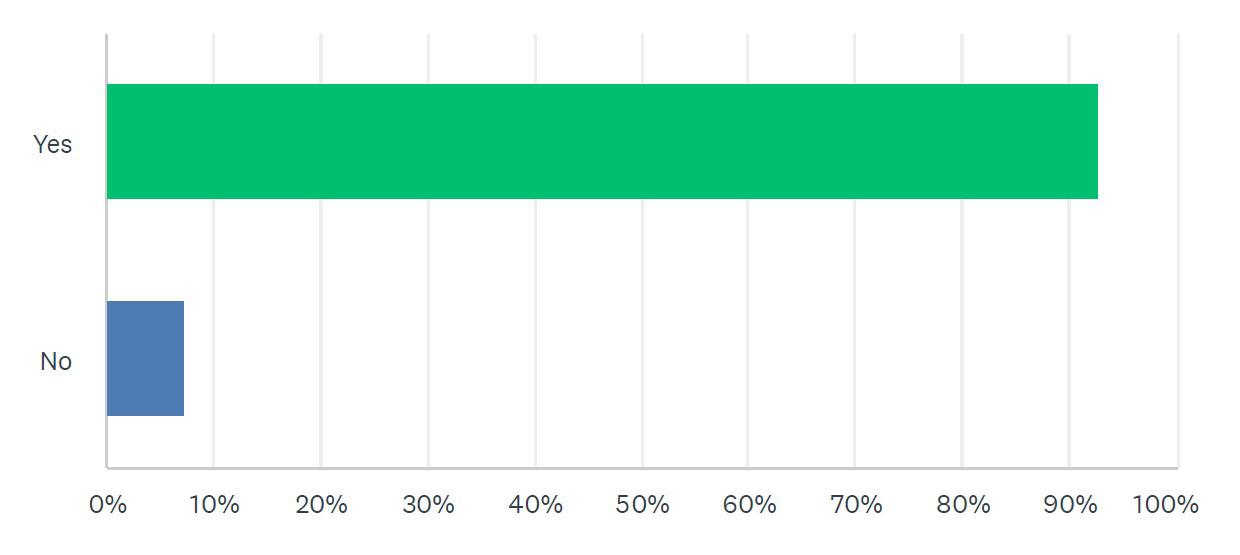

All respondents (100%) rated the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance as safe and effective when used in appropriately selected patient candidates. Most respondents (97%) stated that complications from the therapeutic use of fixed Osseo-RestoreTM are rare and infrequent.

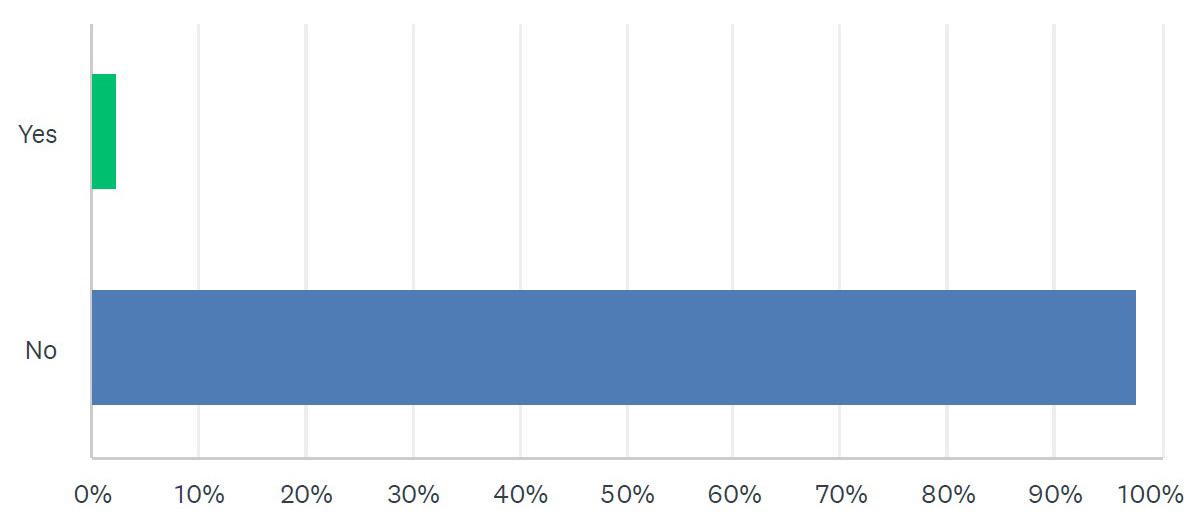

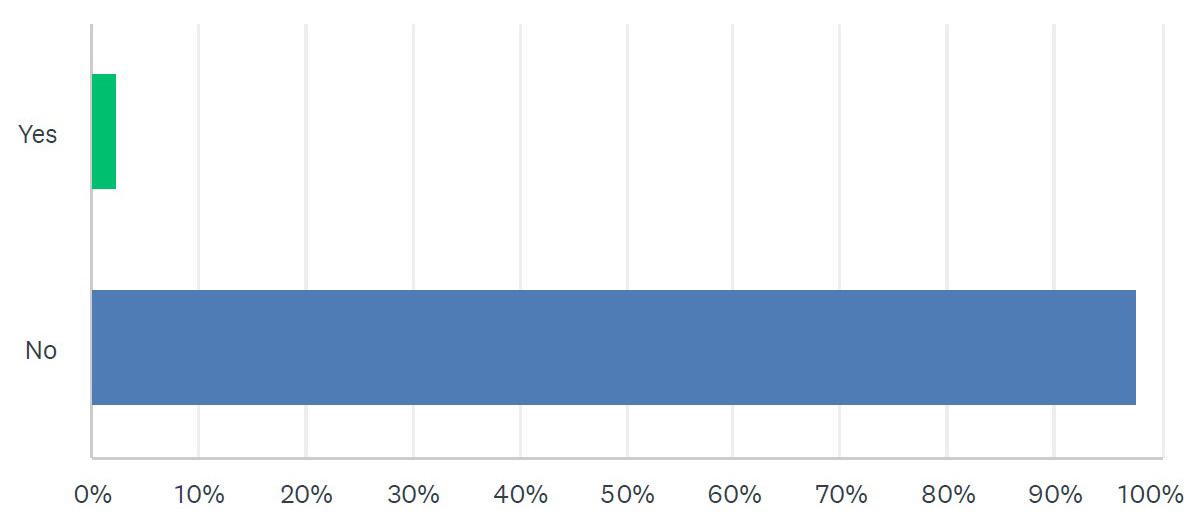

Assessing major complications, 97% stated they had never had a patient lose a tooth attributable to the effects of the fixed OsseoRestoreTM. Many (92%) stated that they had never seen permanent damage to any oral structures that could be attributed solely to the use of the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM.

When ask to access the frequency of complications noted in their clinical experience, participants responded as indicated in Table 1.

18

Fig 2A: The CBS documentary was an unfair, biased, and one-sided portrayal of the safety and efficacy of the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance.

Fig 2B: How many years have you been practicing dentistry?

Fig 2C: How many years have you been using the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance?

Table 1: Responses to frequency of complications noted

Fig 2D: How many Fixed OsseoRestore Appliances do you administer annually?

Fig 2E: Would you consider yourself an expert, advanced, intermediate, or beginner when administerin the Fixed OsseoRestory Appliance?

Fig 2F: Complications from the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance are possible but rare and infrequent.

Fig 2g: The Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance is safe and effective when used in appropriately selected patient candidates.

Fig 2H: Have you ever seen permanent damage to oral structures that you could definitively attribute solely to use of the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance and not a preexisting condition? If yes, please elaborate.

Fig 2I: Have you ever had a patient incur tooth loss, that could be directly related to effects of the OsseoRestore Appliance rather than a unrelated preexisting condition?

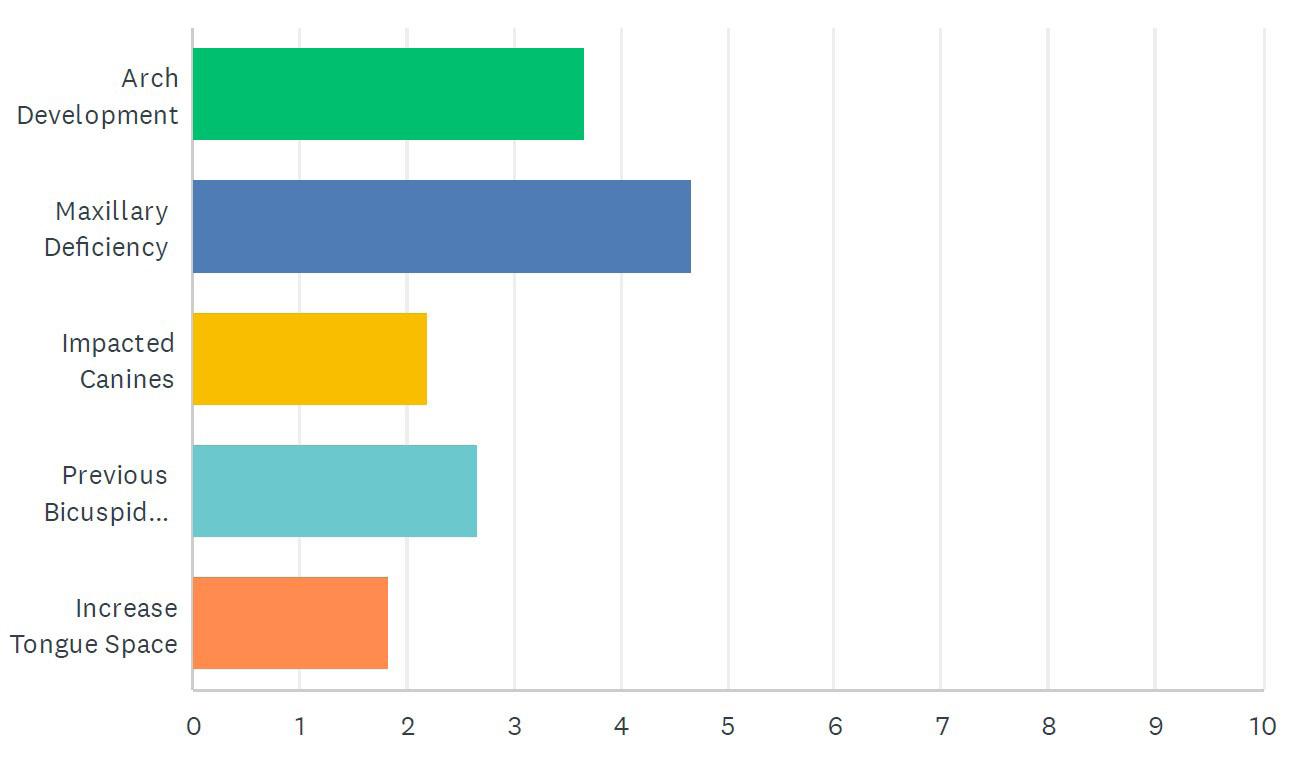

Fig 2J: Rank your most common indications for treatment with the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance from most common to least common.

19 19

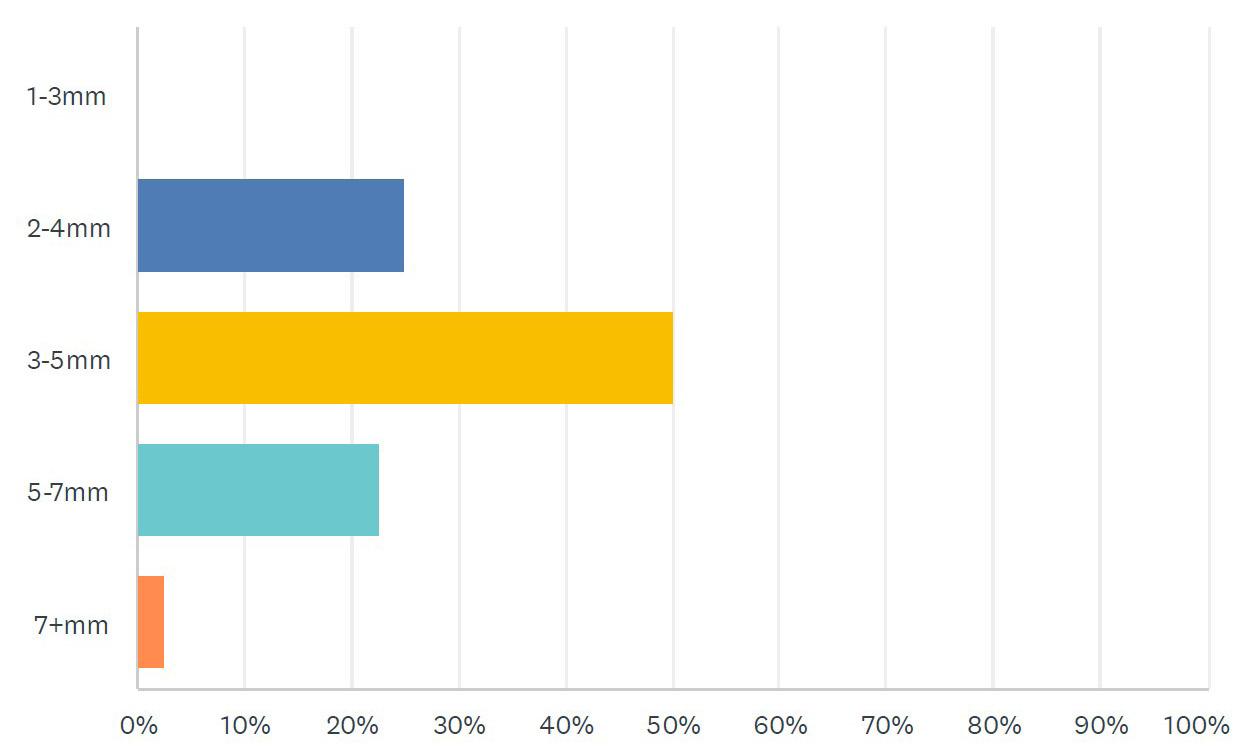

Fig 2K: Based upon your diagnosis, what is the average maxillary development indicated when using the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance?

Fig 2L: Indicate the frequency of occurrance of the following subjective comments made by your patients following the completion of Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance therapy?

Fig 2M: Rank your most common indications for treatment with the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance from most common to least common.

Fig 2N: Do you intend to continue use of the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance?

Fig 2O: Do you feel that the Fixed OsseoRestore Appliance is safe and effective when utilizing it to treat your patients?

20

The most common complications reported were mouth discomfort 19.92%, tooth sensitivity 11.21%, gingival inflammation 10.43% and tongue irritation 10.29%, all common orthodontic complications. Severe complications were rare with tooth loss and tooth breakage at less than 1% and 1.36% respectively. Overall complication rate of Osseo-RestoreTM appliances was 6.97%

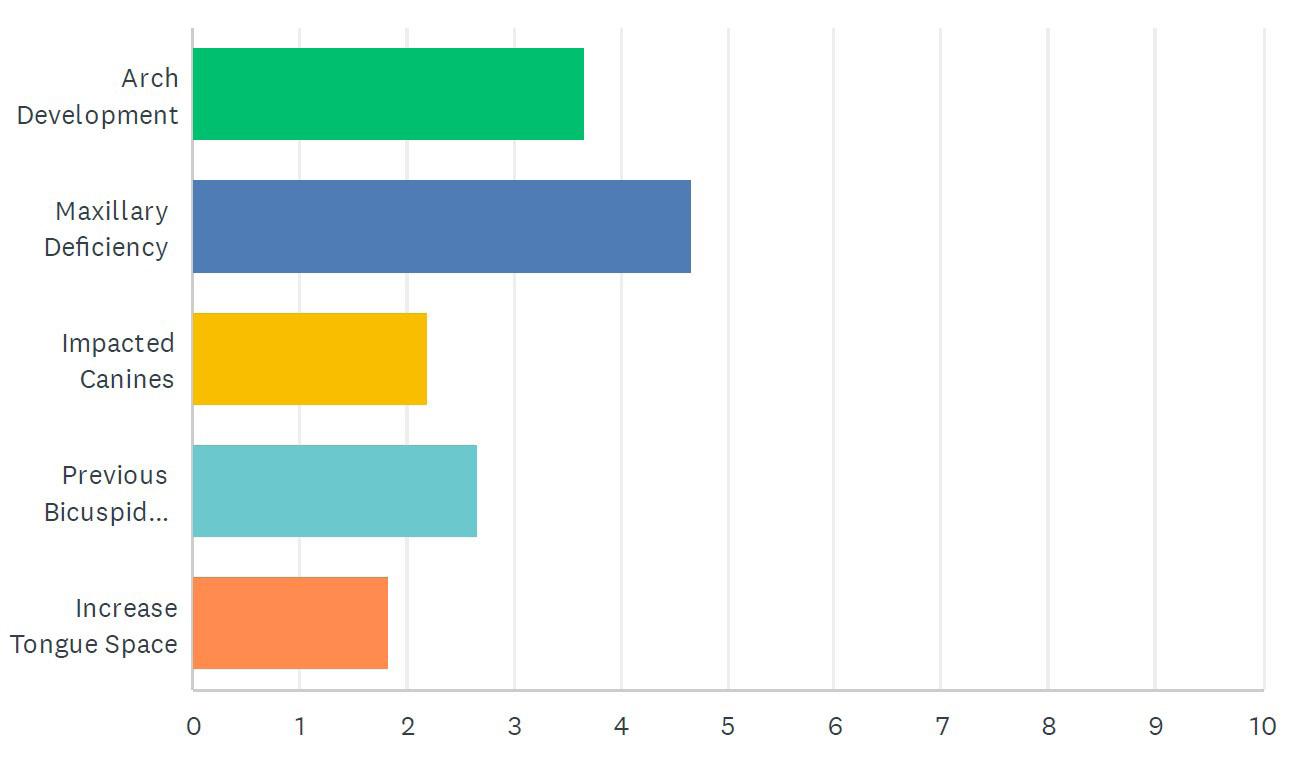

The most common indications for use of the fixed OsseoRestoreTM as prescribed by practitioners in descending order are:

1. Maxillary deficiency

2. Arch development

3. Previous bicuspid extraction

4. Impacted canine teeth

5. Increased tongue space

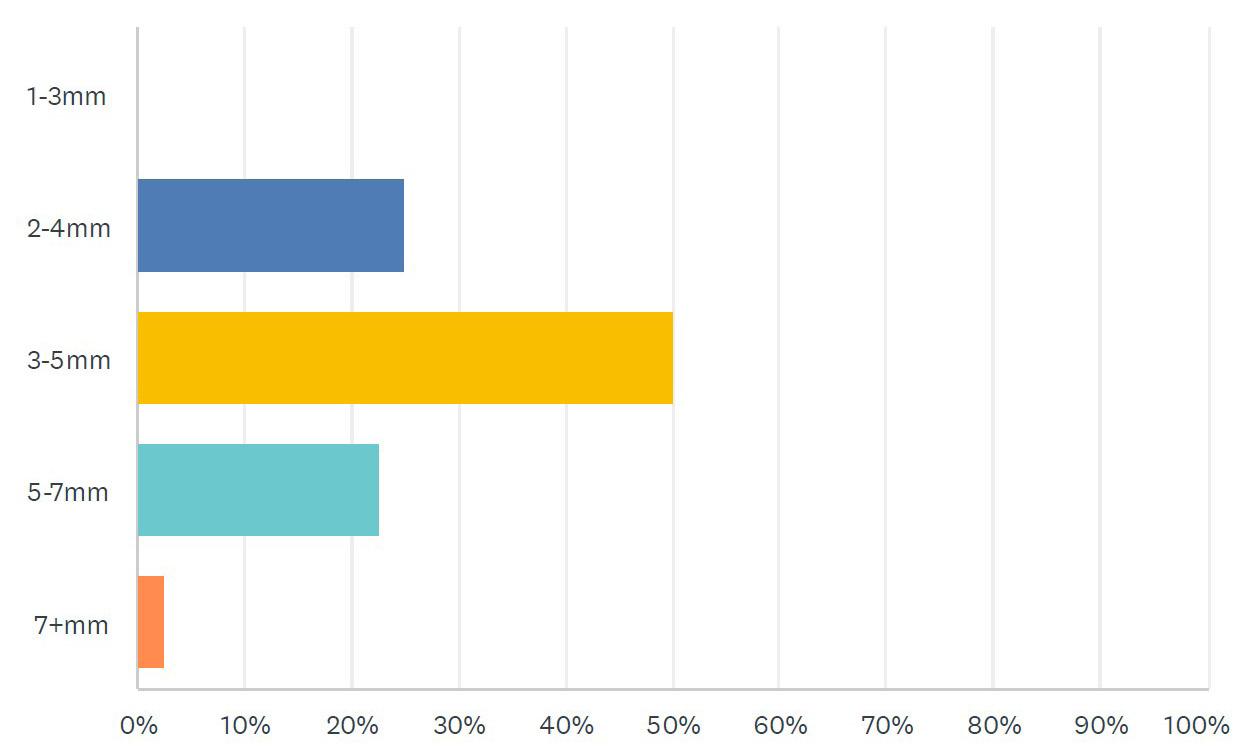

Percentages of recommended maxillary development ranges typically indicated in their treatment plans:

2-4mm: 26%

3-5mm: 53%

5-7mm 18%

Over half of the respondents stated that in their patient populations, over 80% of the patients treated experienced subjective improvement in the following categories:

Less pain/decrease in initial symptoms

More pleasing profile

Increased quality of life

More comfortable

More tongue space

Better lip support

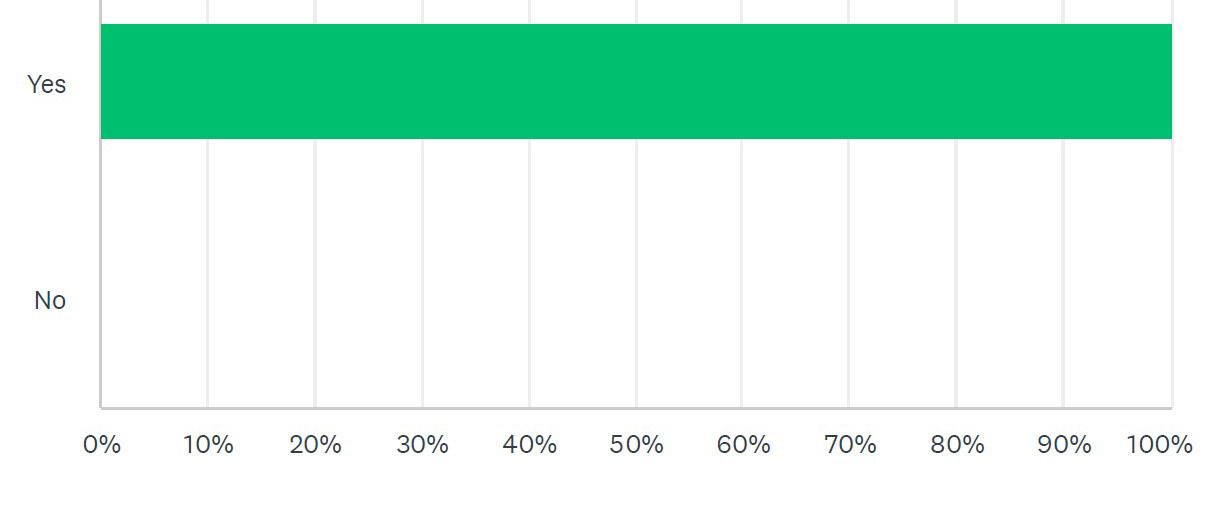

More pleasing smile

Most participants (92%) indicated that they would continue to use the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM as an option for their patients. All participants (100%) stated that in their experience, the fixed Osseo-RestoreTM appliance is both safe and effective.

Discussion:

Complications during and following orthodontic treatment are well documented. No known orthodontic therapies are without risk of undesired complications or side effects. Commonly noted examples are sensitive or painful teeth, gingival inflammation, gingival recession, root resorption, enamel decalcification, occlusal discrepancies, and tooth loss.9-19 One common criticism of sagittal expansion is that the teeth are in some way pushed or moved outside the bony housing of the maxilla. Critics have used CBCT imaging in order to validate this point. Although that line of thinking is very popular, it is misguided and is refuted by basic radiological principles. The size of the voxel elements available on all CBCT machines, that is the cubic volume of tissue that can be measured, is 2 to 3 times greater than the size of a thin lamina of alveolar bone (~100 micrometers). As stated previously, bone remodeling occurs in every orthodontic case. In addition, it should also be considered that remodeling bone is in various stages of mineralization depending on the status of bone at that point in the process of remodeling. When these realities are taken into consideration, it becomes clear that the CBCT simply cannot produce an accurate image demonstrating a thin lamina of bone due to the size of the bone cell and the mineral content of the remodeling bone. Providers relying on the visual CBCT as the benchmark for the status of remodeling are deceived. Figure (3) demonstrates pre-treatment CBCT, CBCT immediately following

3: Pre-treatment CBCT, CBCT immediately following the removal of the ORA, and CBCT 16 months later following removal of orthodontic appliances in an adult patient.

the removal of the ORA, and CBCT 16 months later following removal of orthodontic appliances in an adult patient. The bone is not absent, dehisced, or resorbed in the mid-treatment CT, it is simply beyond the current resolution capability of CBCT.

Complications occur in nearly every orthodontic treatment regimen. As examples consider the following papers on complications with routinely performed expansion therapies. A retrospective study on complications with Surgically Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (SARPE), Smeets et al, showed an overall complication rate of 52.5% with neurosensory disturbances (NSDs) making up 27.03%. A study of complications associated with MiniScrew Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion (MARPE), Bud et al reported a greater than 2mm decrease in buccal bone at the first molar in 40.7% of the cases studied and a change in the occlusal plane in 37% of patients. Williams, et al, reported 41 of 120 SARPE cases studied developed at least one complication (34.17%). In 2022, Yoon et al, reported on complication rates of MARPE. They found gingival inflammation in 83.9%, pain during or after expansion in 45% and appliance breakage in 10% of cases studied. The Osseo-RestoreTM is no more or less likely than any other orthodontic appliance currently in use to incur complications. As is the case with all orthodontic appliances, risks and benefits of Osseo-RestoreTM appliances need to be weighed prior to initiating any orthodontic treatment. Fortunately, the more severe expressions of orthodontic side effects are infrequent and often unavoidable. Nevertheless, they do exist and are therefore should be precisely included in consent for orthodontic treatment as a minimum standard of care for every orthodontic patient 20-23 Pre-existing craniofacial and oral conditions which could possibly contribute to undesirable side effects during and after treatment should be identified, discussed with the patient and documented to insure proper informed consent. The possibility of significant treatment complications exists in some patients lacking any presentation of pre-operative risk conditions should also be considered and explained.

The importance of patient selection criteria obviously cannot be overstated regarding any recommended surgical, dental or orthodontic therapy. Individual patient characteristics combine to require each case to be managed uniquely. Clinical findings such as grossly deficient jaw structure, flared teeth or functional challenges such myofascial dysfunction, chronic oral

21 21

Fig.

breathing and lip incompetence pose significant challenges to all orthodontic therapies. Practitioners who are rigorous in data collection and efficient treatment plan development addressing all identifiable patient deficiencies will be rewarded with a greater degree of clinical success. Development of clear, reasonable and individualized treatment objectives guides patient care and improves patient expectations.

Conclusions:

Historically, innovation in dentistry has been met with controversy and resistance. This is certainly true in the orthodontic realm. Over time, innovations are utilized, debated, researched, and accepted or discarded by most practitioners. The final determinates of the destiny of an innovation are its scientific foundations combined with the crucible of clinical application. This survey primarily explores the experiences and opinions of clinical dentists applying the Osseo-RestoreTM appliance for appropriate patient care. Reported patient complaints associated with the Osseo-RestoreTM appear not to differ from those reported generally in other comparable orthodontic treatments. Patient and clinician satisfaction with appliance results were overall high. It is the opinion of the authors that this clinician survey confirms our own extensive experience that the Osseo-RestoreTM appliance is both safe and effective when used as indicated by properly trained and experienced clinicians.

References:

1. Philippe J, Guédon P. L’évolution des appareils orthodontiques de 1728 à 2007. Conférence inaugurale de la 79ème réunion scientifique de la SFODF à Versailles, le 31 mai 2007 [Evolution of orthodontic appliances from 1728 to 2007. Inaugural Conference of the 79th Scientific Meeting of the SFODF at Versailles, 31 May 2007]. Orthod Fr. 2007 Dec;78(4):295-302. French. doi: 10.1051/orthodfr:2007031. Epub 2007 Dec 18. PMID: 18082119.

2. Enlow DH, Hans MG. Essentials of facial growth. Second ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Needham Press, Inc.; 2008.

3. K alina E, Grzebyta A, Zadurska M. Bone remodeling during orthodontic movement of lower incisors: Narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22):15002.

4. Janson G, Valarelli FP. Bone remodeling and orthodontic tooth movement. Journal of the World Federation of Orthodontist.2012; 1(1), e7-e11.

5. Frost HM. (1987). The biology of fracture healing. An overview for clinicians. Part I. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1987; (225), 239-253.

6. Singh S, Singh SP, Kaur G. Orthodontic tooth movement and bone remodeling: A comprehensive review. Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research. 2020; 10(1), 28-34.

7. Frost HM. (1994). Wolff’s Law and bone’s structural adaptations to mechanical usage: An overview for clinicians. Angle Orthodontist. 1994; 64, 175-188.

8. Lanyon LE. Functional strain in bone tissue as an objective, and controlling stimulus for adaptive bone remodelling. Journal of Biomechanics. 1987; 20, 1083-1093.

9. Renkema AM, Sips ET, Bronkhorst E, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Gingival labial recessions in orthodontically treated and untreated individuals: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34(8):633-638.

10. Ng an P, Kess B. Retention and stability in orthodontics. In: Graber LW, Vanarsdall RL Jr, Vig KWL, eds. Orthodontics: Current Principles and Techniques. 6th ed. Elsevier.

11. Rinchuse DJ, Miles PG, Sheridan JJ. Nonextraction orthodontic treatment using clear aligners: A case report. J Orthod. 2003;30(3):223-228.

12. Al-Moghrabi D, Pandis N, Fleming PS. Randomized clinical trials on orthodontic tooth movement techniques: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2019;156(2):153-164.

13. Ren Y, Jongsma MA, Mei L, et al. The effect of orthodontic treatment on periodontal pocket depth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(4):1589-1599.

14. Al-Moghrabi D, Pandis N, Fleming PS. The impact of orthodontic treatment on dental caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2019;22(2):145-156.

15. Chen YJ, Chang HH, Lin HY, et al. Root resorption associated with orthodontic treatment: A review of the literature. Biomed J. 2014;37(6):350-360.

16. Li J, Li Y, Li X, et al. Comparison of enamel demineralization and bacterial colonization in patients with clear aligners and fixed appliances: A meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):230.

17. González-García E, de Carlos F, Montiel-Company JM, Almerich-Silla JM. Orthodontic treatment and its impact on oral health-related quality of life in patients with fixed and removable appliances: A systematic review. Eur J Orthod. 2016;38(3):241-247.

18. Meeran NA. Iatrog enic possibilities of orthodontic treatment and modalities of prevention. J Orthod Sci. 2013;2(3):73-86.

19. Talic NF. Adverse effects of orthodontic treatment: A clinical perspective. Saudi Dent J. 2011;23(2):55-59.

20. Allareddy V, Elangovan S, Rampa S, Lee MK, Allareddy V. The importance of informed consent in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152(4):423-430.

21. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2014 May-Aug; 7(2): 105–108.Published online 2014 Aug 29. Informed consent for braces.

22. Jharwal V, Terhan M, Rathore N, Rathee P, Aggarwal D. Orthodontic consent form: lsusd.lsuhsc.edu› fdp › wp-content › uploads › 2013 › 06 › fdpconsentortho. pdf

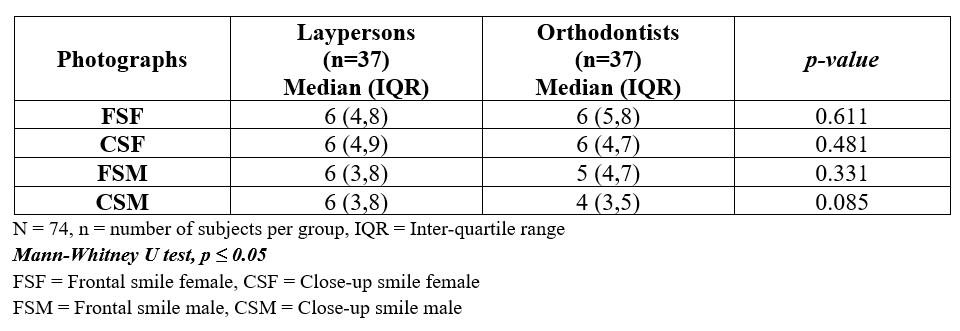

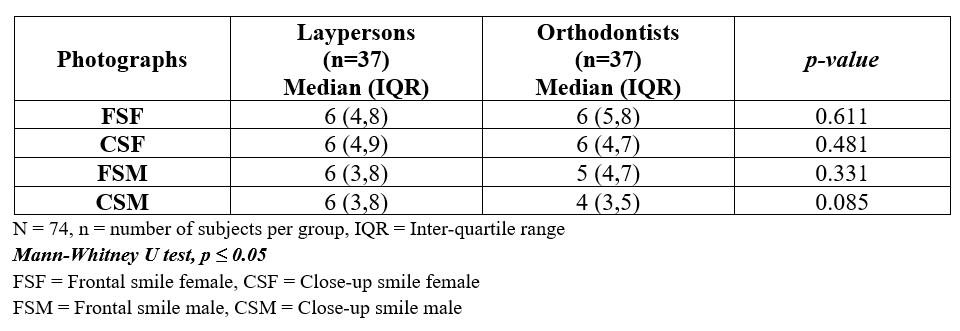

23. Rischen RJ, Breuning H, Bronkhorst EM, Kuijpers-Jagtman AN. Records needed for orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning: A systematic review, PLoS ONE 8(11): e74186. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074186