Post-Prison:

The Reality of Reentering Society

By Molly Balison

I pull off the highway to Kuna, into the parking lot of the largest prison in Idaho, where over 2,100 inmates live out their sentences. The coldness of the building stands in stark contrast with the 87-degree heat. It’s silent except for the intermittent ticking of the electric fence lining the perimeter of the facility. Double chain link gates controlled by officers slide open after a visitor presses a call button on a metal speaker box and waits just long enough to wonder if it will open. Walking along the path leading to the entrance, the quietness is interrupted by distant shouting.

I wonder if there’s just as much anxiety exiting this building after years of growing accustomed to its cement walls as there is entering it for the first time. A sense of

ing with family are some of the greatest challenges faced by those who have grown accustomed to life behind bars. After living in a world of rigid structure and constant control, stepping into a fast-paced society where every decision is suddenly your own can feel more disorienting than freeing. In prison, daily life is dictated—when to eat, sleep, use the bathroom, even how to communicate. On the outside, that structure vanishes, replaced by a flood of choices and responsibilities. Freedom doesn’t always feel like liberation at first, but it always demands accountability.

One woman who knows this struggle firsthand is Pebbles Kellum. The day Pebbles Kellum got out of prison, she had nowhere to go and no one to call. Pregnant with her son, she couldn’t be admitted into a halfway house. Her only option was to go to a

freedom mixed with fear when that day arrives. The day when you turn in your jumpsuit and hope someone will be there to pick you up, let alone want to see you again.

This may be the experience of the approximately 1,000 inmates who are released from prison annually into Ada County and 600 into Canyon County. There are currently 8,000 people in Idaho’s prison system.

Reintegrating into society and reconnect-

homeless shelter in Twin Falls. She moved to Boise with her husband at the time, but found herself homeless again when domestic violence ensued. When she wound up homeless again, CATCH housing services helped her secure the apartment she currently lives in.

“Sorry, I need to take this,” Pebbles Kellum says mid-interview. “It’s my husband.” She answers her phone and talks to her husband, who sits in a maximum security prison enduring solitary confinement for 23 hours out of the day. She hasn’t

seen him in 11 years, but she can talk to him when he calls her cell, and they text throughout the day.

Kellum became the Project Recovery Assistant at Interfaith Sanctuary alongside Terrence Sharrer, Project Recovery’s director who has also experienced the prison system. They help individuals find freedom from addictions with a realistic approach where accountability and second chances are the keys to success in the program.

In Idaho, 37% of those serving sentences— including 60% of women—are incarcerated for drug charges. In light of this, Kellum feels passionately that inmates should be given resources and tools to help them manage their addictions, so they don’t relapse once they’re released and end up incarcerated again.

“They need more than just institutionalization,” she said.

Idaho has a 35% recidivism rate, meaning more than one in three people released from prison are re-incarcerated, which is the 31st highest in the U.S. World Population Review says, “Recidivism affects everyone: the offender, their family, the victim of the crime, law enforcement, and the community overall.”

St. Vincent De Paul, an international organization that serves to prevent homelessness, has nearly cut the recidivism rate of the people that utilize their reentry services to 17%. They are a resource that helps people have a successful transition into society through prison pickup, first-day-out help, recovery coaching, and community service opportunities.

In the eight years that reentry services have functioned out of their Boise office on 5256 Fairview Ave., St. Vincent de Paul has grown from simply pickup services to career development services thanks to Stacey LaRoe’s ambition to visit Idaho State Correction Center with a reentry specialist.

The program manager at St. Vincent de Paul’s reentry services, Mark Renick, who was once incarcerated at ISCC, told LaRoe, “If their heart is ready to change, you’ll know it.”

After visiting ISCC, LaRoe realized that inmates needed access to supportive services prior to being released.

Buck Fry, a cohort facilitator, wrote the pre-release program for all the Idaho prisons. “Our program belief and mission are to serve the exiting population of ISCC using stakeholders (experts in their fields) who come to our facility and conduct whole group presentations, small group cohort presentations, one-on-one personal appointments to those enrolled,” he said in a document about the “why” behind the program.

The six-week pre-release program is broken into the following topics: life skills, education, employment, finance, supervision, and graduation.

In the visitation room, sixty men dressed in forest green uniforms sit in plastic chairs facing the St. Vincent de Paul team

with spiral-bound workbooks in hand. The dusty yellow and burnt orange walls are somewhat of a warm escape from the sterile white walls throughout the prison. These inmates have something in common besides having a felony — they have a year or less of their sentence left to serve.

Although she’s never been incarcerated, LaRoe encourages people in the pre-release program that, “Reentry starts the day you get in.”

Another key figure in the reentry effort is Dawna Loa, who brings lived experience to her work.

Reentry Career Development Manager Dawna Loa, who was incarcerated just four months before teaching at a pre-release presentation, tells her fellow felons how to talk confidently about the skills they have to offer, not selling themselves short because of their past.

Post-Prison: continued on page 2

Stacey LeRoe (left) speaks to a cohort at ISCC’s pre-release program alongside Dawna Loa (right).

ISCC partners with the University of Idaho and Lewis and Clark College to provide education to inmates.

Word on the Street

PO BOX 9334

511 S Americana Blvd

Boise, ID 83702

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Molly Balison

WOTS WRITERS/COLUMNISTS

Bo Gerri Graves

Viola Crowley

Nate Dodgson

Eric Endsley

Jodi Peterson-Stigers

Molly Balison

Nicki Vogel

WOTS Historian

Nicky MacAislin

WOTS STREET PHOTOGRAPHERS

Heather Baird

Gypsy Wind

Eric Endsley

ART COLLECTIVE DIRECTOR

Chris Alvarez

CONTACT THE EDITOR

To submit story ideas or community articles, please send request and information to molly@interfaithsanctuary.org

POETRY CORNER

Brandon Clipped Wings 1 Freedom

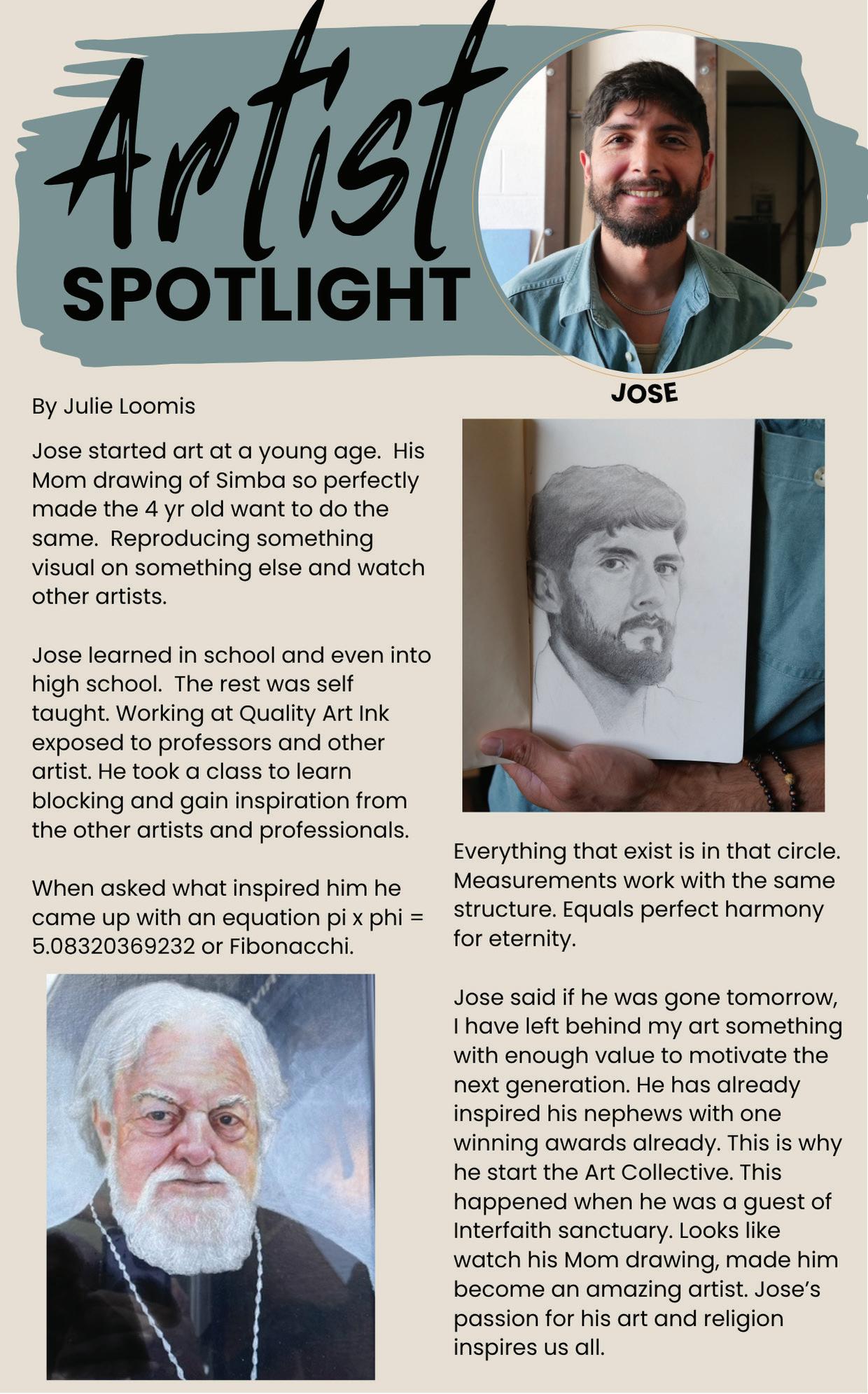

By Julie Loomis

My son is joy, bright bursting energy.

He looks at me, this is the best day it can be. He smiles, ask for a hug, Mom, I love you, thanks for everything you do.

My son is angry, he doesn’t understand why.

I am not listening?

Impatiently he explodes and whines.

I tell him no.

He starts to scream. He is out of control.

I eventually get through.

My son is sad, his life is crushed, he cries about what he could have had; heart wrenching sobs of remorse.

My son feels wrong.

He tells me to take away everything, he doesn’t belong.

He cries; I don’t deserve to be happy.

Sometimes even to live.

He lies on his bed in a ball.

He has no more tears to give.

My son wants a hug. He tells me he is sorry, his eyes ask; forgive me let it be.

Mom, I love you.

Brandon doesn’t understand why, He has all these emotions inside. Most times hardly remembers. Sometimes wants to hide.

Brandon’s like a summer’s day. Sunny and warm, then suddenly comes a cloud. A drenching rain storm.

Then it slowly stops.

The clouds drift away, out comes the rainbow.

The son’s rays only delayed. Brandon

By Shyloh Crawfurd

Why give me the courage to fly, Only to snip my wings yourself? No longer grounded by my choice, But sentenced still, without a voice. You taught me prayers before I could speak, Told me God would shelter the meek. You sealed the doors, locked out the world, Tamed the wild child, and tied the boy. No sleeveless shirts, no dancing late, No open roads, just heaven’s gate. You clipped the noise, the music, light— Told me “truth” was what felt right. You gave me courage wrapped in chains, A voice to sing, then called it vain. You said to soar, to trust the skies— Then cast me out with severed ties. Why give me the courage to fly, Only to snip my wings yourself? No longer grounded by my choice, But sentenced still, without a voice. At eighteen, I stood on sacred stone, And watched you leave me all alone. No suitcase packed with second chance, Just folded hands and backward glance. The shelter walls, the aching cold, Replaced the pews, the cross, the gold. No more “Amen,” just echoes sharp— Of love that stops when life gets hard. I found a Savior in the street, Not in the sermons, soft and sweet. I found my worth in nights unspoken, In hunger’s truth, in systems broken. I still believe in something bright, But not in those who dimmed my light. You raised me high to watch me fall— But I am rising, after all. And though the scars still sting with frost, I’ll bear them for the love you lost. For even broken wings can mend, And I will fly— just not again for them.

By Critter

Freedom is here but only for the free. Freedom is gone because of greed. Freedom Is Lost with the wrong boss. But freedom is mine until I die.

Dear Freedom

By Travis Walker

Freedom I have longed for you before. To you freedom I have ran as you before, and to you, freedom I have sought. I have fought for you! I feel free when I am able to run at a full potential in the eyes that Jesus may gaze from. To you freedom I ask for the Lord to teach me more of.

When Loa asked who hates asking for help, two-thirds of the inmates in the room raised their hands. St. Vincent de Paul teaches felons how to inform others of their needs and how to be honest about their conviction without letting it define them. Getting out provides a fresh start, even if it is more challenging for someone with a record to prove themselves to their potential employer.

“You walk out and you get this new opportunity and you can be a person that’s always wanted to be and it’s kind of beautiful,” LaRoe said.

The organization takes a holistic approach to meet individuals where they are, including helping write resumes and cover letters and practice interview skills. Even if people have an impeccable resume, employers may still toss an application if they see “yes” checked on the dreaded question: “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?”

“The beauty is we’re able to be inside the facility and get to know someone so we’re able to screen them out warmly with someone that they already know, with faces that have been there, knowing that they don’t have to explain themselves, feel shamed, or feel any kind of pressure,” LaRoe said.

Kellum visited the women’s prison with LaRoe and shared her story of overcom-

ing obstacles to give the incarcerated women hope. “We’ve made mistakes that have landed us on the path that we’re on,” Kellum said. “But that doesn’t make us bad people. That doesn’t make people that have been incarcerated—doesn’t make the people that are trying to better their lives—a bad person who needs to be looked down upon. We’re trying to get our s— together, and without that help and that support, like we’re not gonna get far.”

One inmate I spoke with noticed that after 2016, more resources and opportunities, including college courses and mentorship, started being integrated, which impacted his personal and professional growth. The inmate not only turned his life around in prison, but became a mentor to those experiencing the same struggles he once did. “Your decision is more powerful than you know,” he said.

Every week, more people are released from Idaho’s prisons with no home to go to, no job lined up, and no support waiting.

The system may call it freedom, but without enough resources, it’s a setup for return. If the cycle of recidivism is to be broken, it’s not enough to open the gates. People have to open their eyes, their doors, and their hands. The introduction of resources and the compassionate support of those who decide to meet those who have ended up behind bars makes all the difference.

ART COLLECTIVE

By Bo

What’s the difference?

Let me start with a question: What’s the equation for success? I believe it’s when practice meets motivation.

Now, let’s talk about being inspired. Most of us have been inspired by someone or something. And at the same time, we might be inspiring someone who’s watching us—even if we don’t know it.

But here’s the thing: Motivation is what happens when inspiration turns into action.

That means you see someone do something great—or beat the odds—and it moves you. That feeling is inspiration. But until you act on it, it’s just a feeling. The moment you take a step, make a change, or move forward? That’s motivation.

And eventually, when motivation meets practice, we get success. Now, success doesn’t always mean money or recognition or “having things.” Success is doing the work. It’s showing up. If something comes to you and you didn’t work for it, maybe it’s just luck. But then again… if you be-

lieve in God, do you really believe in luck? I don’t think so.

I wrote this in hopes it helps someone. It started as a conversation I had with myself, wondering: “Why am I not where I want to be in life?”

I told myself, “I’m so motivated. I’ve been motivating people my whole life.” Then it hit me—I wasn’t motivated. I was inspired, yes. But motivation only happened when I took action.

When I got my forklift license, it wasn’t because I just felt inspired. It was because I saw people making more money, and I made a move. I turned that inspiration into motivation by taking a step.

So let me ask you: Are you inspired? Have you been for a while? That’s not a question for the world. That’s a question for you to ask yourself, quietly, honestly.

Keep that inspiration alive. But don’t stop there. Put some action behind it—and watch it turn into motivation. That’s when things start to move.

God bless.

Photo by Gypsy Wind

COMMUNITY PARTNERS

Healthy Boundaries

By Kayla G. Licensed Master Social Worker

Hello! This month we’re talking about boundaries. A boundary is a clear expression of what you are comfortable with and what you are not. You often know when a boundary has been crossed if you feel a strong emotion or get an uncomfortable sensation in your body. Pay attention to those signals!

Clearly stating your boundaries helps others understand how to treat you with respect. Setting boundaries is a skill that helps protect your energy, emotions, and safety. It is okay to ask for what you need and to say no when something does not feel right.

Here are some examples of how to set clear and respectful boundaries:

• “I am not comfortable with that topic. Can we talk about something else?”

• “I need some quiet time right now. I will check in with you later.”

• “Please do not come into my space without asking first.”

• “I cannot loan money, but I care about you and hope things get better soon.”

• “When you raise your voice, I feel unsafe. I am going to step away.”

• “I appreciate the invite, but I am not up for socializing today.”

• “I need to take care of myself right now. I hope you understand.”

Boundaries can feel uncomfortable at first, especially if people are used to you always saying yes. But honoring your limits helps create stronger and more respectful relationships. Every one of us deserves to feel safe, heard, and mrespected.

DEEDS ON THE STREET WOTS

Blessing Bags

By Molly Balison

Hill City Church dedicates the month of June to serving their Boise Community and making an impact in tangible ways.

The congregation that meets on Sunday mornings at 9:15 a.m., 11 a.m and 5 p.m. is determined to spread the love they share beyond the walls of their building on the corner of 9th and Franklin. While the congregation gathers on Sundays at 9:15 a.m., 11 a.m., and 5 p.m., their mission reaches far beyond the walls of their building at 9th and Franklin.

One service project on June 18 focused on caring for neighbors experiencing homelessness. Seven couples, young and old, gathered supplies to assemble what they called “blessing bags”. The group packed

88 gallon bags with practical essentials: toiletries, snacks, bottled water, socks, towels, oral hygiene items, and sun care products.

Each bag also included a handwritten note of encouragement as a simple reminder that the person receiving it is seen, valued, and loved. The group ended the night by praying over each bag and the individuals who would receive them.

Becky White, the organizer of this 3rd annual event, said that the heart of the project is “to care for those who aren’t as well off.”

Each participant took home several bags to keep in their cars to give out when they cross paths with someone in need. “We’re trying, in just our little way, to be the hands and feet of Jesus,” White said. “This is something we can do to make a difference.”

FREEDOM AND FAIRNESS

Overcoming Adversity, Surviving and Thriving Through Incarceration

By Buck Pickens

This Idaho citizen shared his story with a WOTS staff member and wanted to express his gratitude for the heartfelt care and support the Boise community provided him, his mother and brothers while they experienced homelessness when Buck was 16 years old.

The story of Buck Pickens is not an easy one to tell, but it is an inspiration to hear. He came to prison at the age of 18 in 2006 after being sentenced to serve a lifetime. He was angry and full of pain; after serving two years in a hellscape, he joined and later commanded the Aryan Knights (AK). His destructive decisions and violent behaviors would have him serving the next 16 years at Idaho maximum Security Institution (IMSI); seven of those years in Administrative Segregation. Ultimately he would be Federally indicted for racketeering in a criminal organization. That is how his story began, but it would not be how it ends.

In 2022, disillusioned with the path his life was on, he would decide that he needed

a change. In 2023 he would join the first Prison Fellowship Academy, dedicating his life to God and to following the teachings he learned in the Bible. Even after knowing him from his past, Officer Novotny decided to give Buck a second chance in the kitchen at Idaho State Correctional Center (ISCC) as a baker. He relished his job; something about taking flour and water, combining them together to create something good and pure was soothing to his soul. After all the violence and the destruction he had caused, he found healing in serving others.

He entered into an apprenticeship through the Idaho Dept. Of Labor and became a journeyman production cook. He was given the opportunity by Michael Copenhaver, Chris Shannahan, and Bradley Heater to become a mentor for team M.O.T.I.V.A.T.E. During the partnership training, Buck felt the care and support of IDOC leadership when Deputy Chief Amanda Gentry showed her humanity by inviting her mother to share in positive moments with the mentor team, and when Chief Chad Paige shook his hand even

after knowing him from his past Buck felt his community reaching out to him and he wanted to give his heart in return.

Program Manager Valerie Walsh showed support at graduation, spoke to Buck about knowing of his past and how she has always wanted to help the youth in prison. She created the Y.W.G. Youth Mentoring Program. Buck leapt at the opportunity to help troubled youth navigate the perils of prison. It was this opportunity that inspired him to continue on the path of giving his all to his community.

In 2024, college opportunities were offered to residents at ISCC. Buck would become the public image of the college program.

He would work hand in hand with Dovie Willey, the adult education liaison from Lewis-Clark State College, to implement this program in prison. He is currently working toward a college degree bachelor in Business & Communications.

He was doing all this while keeping a fulltime job as well as being selected to the Steering Committee for the Motivate Mentor program.

Buck has such a passion for helping others that he was nicknamed “The Squirrel” because as soon as he sees a new way for him to add value to others, he drops what-

ever he is doing and darts after it — like a squirrel when he finds a nut.

He has gone from a life of causing destruction for people to shining a light at their feet so they see the traps laid bare on the path before them. His pain has been transformed into love for those around him. Former members of his prison gang, seeing the change in Buck, have decided to follow his example and dedicate their lives to being better men. It is his hope that he continues to be able to find those opportunities to serve and add value to others.

Buck contributes his change and continued growth to the genuine investment of mentors and staff. It has been the value added by staff such as Deputy Warden McKay when he helped Buck through a moment of grief, Food Service Officer Alcott when she let him touch a tree after 18 years. Officer Cerillo’s encouragement that Buck was a good man and made him see that he was. Lt Hoyt provided help when he was at his lowest. Program manager Greg Norton gave him a chance in education. Program Manager Valerie Walsh showed him that investing in his community is the greatest purpose of all. To everyone in his community that showed him what it means to truly add value.

Opportunities in prison Buck took advantage of to help change his life:

• Prison Fellowship

• Courage for My Life

• Today Matters

• M.O.T.I.V.A.T.E Mentor Program

• Apprenticeship Program

• College • Bakery

• Y.W.G.

• Resolution for Men

City Council Approves Anti-Camping Enforcement Plan

By Molly Balison

On June 24, Boise Police Chief Christopher Dennison proposed an enforcement plan for SB 1141 to the City Council. The legislation, taking effect July 1, bans prolonged camping on public property, buildings, and roadways in cities with a population of 100,000 or more in the state of Idaho—Boise, Meridian, and Nampa.

According to the Senate Affairs Committee, “‘Public camping or sleeping’ means lodging or residing in a temporary outdoor habitation used as a dwelling, lodging, or living space, which includes sitting, lying, or sleeping for a prolonged amount of time, and may be evidenced by the erection of a tent or other temporary shelter, including a motor vehicle...”

The bill states that overnight recreational or educational camping within a designated property will not be affected by this law.

Chief Dennison recommended issuing a $10 fine and letting officers use their discretion when issuing a fine to a citizen found camping in a public space. Dennison said

that in the last three years, 74 tickets have been written up for individuals occupying public space when there is room at a shelter. Now, infractions will be issued regardless of shelter availability.

Folks who are displaced don’t have to fear being arrested and doing jail time if found camping in public. Although a fine is not easy for someone who is barely scraping by to pay, it is better than obtaining a misdemeanor, which stays on an individual’s record.

“It felt so reasonable, and it was relieving to know that a fine is much different than a misdemeanor when it comes to creating more barriers for the people that we’re working with,” Jodi Peterson-Stigers, Interfaith Sanctuary’s executive director, said.

Interfaith Sanctuary’s beds are full every single night, so when an unhoused individual can’t find shelter, they are at risk of deteriorating health and well-being due to lack of rest, nutrition, and stability. The hope is that providing safe shelter will minimize survival crimes for the most vulnerable

population. Interfaith’s conditional use permit for their new 24/7 access shelter home on State Street will be heard on July 7 to determine how the nonprofit can proceed to meet the needs of the homeless community.

“My hope is that we raise up more solutions that are more permanent, that are not punitive, but supportive,” Peterson-Stigers said.

In light of this law, the question remains: When people have nowhere to go, what should they do?

“Boiseans have made it clear that there’s so

much more than ticketing that needs to be addressed and provided to ensure that we continue to not have the issues we’ve seen in other cities,” Mayor Lauren McLean said in the City Council public meeting. “I am without doubt that our residents understand that this is not the solution. The solution is to look at long-term solutions, look at housing and all the other pieces of investing in a city and a neighborhood and people—that we continue to do.”

With the approval of the new enforcement plan, the city of Boise moves toward a more resource-oriented approach to avoid criminalizing homelessness.

FREEDOM AND FAIRNESS

My Father and Liberty Road to Redemption

By Bo

I was done with the construction program and waiting to finish the food training program. My friend had left the shelter and I’ll just say he had to fight his own battle — I’ll leave it at that. My day to day routine had changed. Not only was I done with the class, but my boy left so I had lots of idle time.

To be honest I had gotten frustrated with the food program because it was taking longer than I felt it should have, I was having small issues with the guy running it and felt like I wouldn’t even get a job out of it anyway. The one thing that I did know was that I had to stay focused. Me helping people out and keeping them from messing up was a big key to me being successful. It gave me people to talk to and also made me stay more accountable. There was also another person I befriended and was trying to help out. I won’t get into his story either but I’ll just say he didn’t make it. I felt frustrated at the same time that I was at the shelter and wondered if I did it all for nothing.

I kept telling myself that my future job had to be in God’s plan while at the same time, I was telling myself that no one would want to hire a felon. After a few weeks went by, I finished the program and got an interview at Boise State University for the position of a prep cook in Dining Services. My interview actually went very well and I even negotiated for an extra dollar on my hourly wage.

I received an offer letter and was hired

contingent on passing a background check. I anxiously waited for about three weeks to get an answer. So of course, in those last two weeks, I began to complain and talk myself out of the job — self doubt set in. But really it was just me preparing myself for the let down of not getting the job. It wasn’t how much I was making at Amazon. I was told I couldn’t get free classes or a discount for working at the school.

When I reached out again, I was told that the HR lady had been sick. I figured this was a good enough reason for the delay. Within a week I got accepted and felt a great sense of joy and accomplishment. But I started to doubt myself again.

I’m a Taurus and very bull headed. I often get into it with people since I have a no nonsense personality, so, at times I can be very aggressive or assertive. I was talking to someone from the shelter and he kept reminding me that I couldn’t take that part of Bo into the job. I reflected on how many supervisors I had disagreements with. I’m the type of person who always speaks my mind even in situations where it’s probably best to just keep my mouth shut.

So I kept saying to myself “Be humble. Be humble. Be humble.” Weird that you even would have to remind yourself of something like that. I also wondered if I would like the job and if my coworkers would like me. I had a lot riding on this job. I saw it was my opportunity to get back on my feet. This was my road to redemption finally lining up.

I started my job a couple weeks later.

My Friend Mike Pratt

Julie Loomis

Life is hard at the shelter, and one thing that makes it tolerable is good friends. Mike was one of the few guys I got close to. His silvery hair, twinkling eyes and sweet grin just pulled you in. Mike was shy at first, yet once he felt comfortable around me, he had a lot to say. I miss him every day. I have kept his last voicemail just to hear his voice.

The first time I saw Mike, he was shuffling along with his walker. He reminded me of Albert Einstein. He hated that, and I am glad I never said anything.

Mike joined the YMCA, and eventually, he didn’t need the walker and was bicycling around. He was always a great example of getting back on your feet.

We really started to get to know each other when I was growing a few plants. Mike offered to help me out. I get flared up with my fibromyalgia, so he would water them when I was unable.

He let me know that during a several-day hospital stay, he would water my plants. We would sit outside and talk about anything and everything. My friend Branda also became close to Mike. He loved blue bunny ice cream.

Mike finally got his apartment, but I was in the hospital and forgot to give him my phone number. It was a rough winter, and I finally ran into him near his apartment. He was so excited about his new place and invited me and Branda to come visit.

We all had health issues, and we finally got together and hung out. I said I would

help decorate it. I still have the pictures we were going to look at. His good friend Jonathan helped him with grocery shopping and set his TV up. Mike kept his friend circle small, and I was grateful to be a part of it.

I never got to make it back over, and it broke my heart when I heard he had a massive heart attack. He was in a coma and on life support. Jonathan kept me informed when they found several strokes and took him off life support. I couldn’t bring myself to see him like that. So I will remember the sweet guy as he was riding his bike. These are my memories of Mike. I didn’t know everyone he left behind, but many friends from the Interfaith Sanctuary, including Jonathan, Branda, and I. He had a great relationship with his brother and sister-in-law, as well as their children.

I hope you have plenty of bike trails and rivers to kayak. You’re in a better place, and we all miss you so very much.

By Julie Loomis

My father was born Hachi Fujisawa on February 18, 1927, in Rexburg, Idaho. Both his father and mother came to Idaho from Hawaii but were born in Japan. Many Japanese worked the pineapple fields to save money and bring their bride over. There was a small community of Japanese who lived in Rexburg at the time, and they bought land to raise their children on. Dad grew up on a farm with his seven brothers and five sisters. Dad was close to his mother and had many fond memories of her. His mother and oldest brother caught typhoid in Japan and died. This left his Dad to raise 11 children.

Dad played basketball in Rexburg High School and had many friends. The Japanese children went to classes after school to learn about Japan so they would remember their culture. Most second-generation Japanese were proud to be Americans and showed it after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Liberty to Dad was living in America and was an American citizen. He was proud of his Japanese heritage, yet also proud of the country he lived in. This was devastating to the Japanese community, which was suddenly shunned by their neighbors and had their guns and radios taken.

Signs showed up in restaurants and other businesses saying No Japs Allowed. The brothers had to walk together in town for their own protection. His older brother volunteered to serve in the army. My Dad and the next oldest were also drafted. I asked Dad why he would serve in a country that rejected him, and he simply stated that it was “the right thing to do”. His youngest brother had joined the Mormon church and was excommunicated.

Yet they still believed in a country that didn’t believe in them.

At the same time, the place where Pearl Harbor was bombed did not round up all

the Japanese and put them in relocation camps. They did put the ones who they thought were causing trouble, but for the most part, they just surveyed them. Executive Order 9066 was to take any Japanese citizen with 1/16 or more to internment camps along the West Coast. This included California, Washington, Oregon, and some parts of Alaska. The Japanese were given 48 hours to sell all their businesses, property and assets. They were only allowed one suitcase.

Can you imagine having 48 hours to put your possessions in one suitcase? The internment camps were drafty with little food and scarce facilities. Many Japanese felt abandoned and suicides were high among the men. Their sons were drafted to fight for the same country that imprisoned them.

Dad, like many of his generation, felt it was an honor to serve in the army. About 33,000 men served in the war and 800 died for a country that dishonored them. They trained with other minorities because they kept the races segregated. Dad served as a medic in a mixed-race group in Germany. Dad never really talked about his time in the army. That is not unusual. Many Japanese came back from the war or internment camps to a different world. Many were still shunned and had to start over. That could be why my Dad’s family changed their name to the maiden name of their mother. It was more American-sounding. Dad became Herch F Bingo. That was his name until he passed away.

Dad became an example of liberty to me. That may seem odd considering how he was treated. I believe he made his own liberty because he fought for this country, because he believed in liberty, and he succeeded. He owned land and married. He had three children and instilled in us the values he had. Work hard and you can have your own freedom.

Freedom from Abuse

By Viola Crowley

I have lived in an abusive marriage for 16 years. I felt trapped for most of those years. I’ve tried leaving him many times but I kept taking him back out of love. I kept confusing being in love with him and just loving him.

When I finally accepted the difference, I

came to terms with the fact that I was no longer in love with him and that began my journey to freedom. Once I was able to explain to him that I was no longer in love with him and why, I felt more free.

I’m still in the process of trying to get him to accept the fact that I do not want to talk to him. so I feel more free now than I have in 16 years, but I see a very near future with total freedom.

A Moment of Unfairness

By Julie Loomis

Jule I lived in Blackfoot Idaho and I saw how they treated indigenous people at the fair. This was in the late seventies to early ‘80s. The security would purposely go after them and beat them up even if they didn’t resist. My friend was arrested right

in front of me. This was a group of 10 plus teenagers. He was the only one targeted. He didn’t resist yet they still tackled him. we all started to yell at them to let him go, they threatened to arrest us. he told us it was okay with the sad look in his eyes and dirt on his face.

The Value of an Individual

By Gerri Graves

My kids and I get together once or twice a week. We fix dinner, eat and discuss current topics. They each have their own subjects of interest, as well as I, and we basically update each other on articles we’ve read that week.

We’ve been on a rather worldly foodie kick lately. Pozole, Thai curry, Indian curry with homemade garlic naan, Korean Bugolgi, Lebanese Shawarma......you get the picture. Lots of great food, made from scratch. Bean’s up next with Korean vegetable pancakes with pickled radish and kimchi. Vero is working on a Japanese dish.

I was particularly excited about that last one, as I just found this $400 Hitachi Japanese rice cooker, brand new, at a yard sale.... for $4! It’s all in Japanese, which meant I had to translate all the directions. (We found it even more awesome that it WAS all in Japanese.) I was itching to play with it.

At one of these dinners, we were discussing the articles we had read that week, and we had come to a somber realization. A life, many lives, that had been taken.....were all reduced to numbers. We couldn’t find the names of the victims anywhere. Thousands of lives were extinguished, and we don’t even know their names.

Dismissed as collateral damage --- Those two words we latch onto, to excuse the innocent victims caught in the crossfire.

I mentioned, on my end, an article on a coroner in Colorado, who has been accused of secretly burying ‘homeless’ men, without a grave marker or even notifying the families. One victim was double buried with another man. Just put in a body bag, and thrown in with another burial. Had the family of the buried individual not asked for an exhumation, the second body would never have been found. What’s worse, they don’t know the identity of the victim that was double buried.....not that I could find anyway. (There’s corruption involved, but I’m not including it, because that’s not the point of this inclusion.)

We talked of current wars. Of kidnapping and forced labor.....either as sex workers, or other.

I read of where a Chinese actor was lured to Thailand for a role he was offered, and then, just disappeared. His family were relentless about finding him, however, and a private detective was hired. The PI ended up finding him in a slave compound where victims were forced to make calls for phone scams. Locked to a desk. Tortured and beaten. His kidnappers only gave him back because of the public outcry his family had managed to muster. The perpetrators had lured him to Thailand, kidnapped him and

crossed the border into Myanmar where the compound was located.

What’s worse, the recovered victim spoke of hundreds more still in captivity.

We talked of people warehousing. Especially in some Asian countries. Rooms, barely the size of a closet, in large buildings that housed thousands. Mentally and physically disabled, the elderly....even some children.

Casualties of many wars currently playing out globally. Paupers graves. Mass burials. No memoirs. No family or friends speaking on their behalf. No names. Just numbers, nothing more.

I’m going to do a mid-article change here, and look at this from a different angle.

I recently attended a four hour seminar on the Fair Housing Act’s rules/regulations hosted by at least 3 female lawyers. It was presented by Our Path Home and the Intermountain Fair Housing Council. While the info itself was rather dry..... information laden powerpoint presentation, the lawyers themselves gave us examples of how these rights were abused and how they had affected their clients. That alone made it one of the best seminars I have ever attended.

I am unable to sit for four hours without consequences...meaning, I will be in excruciating pain for the rest of the evening, but the stories that were discussed were so powerful that I stayed. That’s how important this information was to me. (And yes, there definitely were consequences.)

They related stories of how the disabled and impoverished were either taken advantage or kept out of housing altogether. For instance, an apartment building refused to rent to a person with a hearing disability. Their reason? He wouldn’t be able to hear the fire alarm. By law, he was allowed reasonable accommodation.

Another instance involved a disabled person’s service dog. They demanded a DNA sample from their service dog. Their reason? In case the service dog created damage, they would be able to keep the deposit or sue for damages.

An immigrant family (non english speakers), were being overcharged on their rent.

A family with small children, were told

there were no units available, when in fact there were. The excuse the property owner gave? They were not ground level units. He had said he thought they wouldn’t be interested, given they had children. That wasn’t his choice to make.

Did you know that assistance animals do not require a deposit or ‘pet rent’? They also cannot restrict your animal based on breed, require proof of need, call your Dr for proof, random unit inspections (based on assistance animals), charge carpet cleaning fees, DNA testing or single out a renter based on their need for an assistant. They also pointed out that many are paying 50% of their wages (or higher) just in rent alone. Stats from 2024 state that in order to afford a 2bdrm house in Ada County, you’d have to make approx. $55,520/yr or $26.69/ hr. That is if the rent is $1388/month. The current 2bdrm average in Ada County p/ Zillow last year was $1740.

What occupations can actually afford to rent in Ada County? Front line managers, registered nurses etc. Teachers were dropped from that list in 2024. A college educated teacher cannot comfortably afford the rent here in Ada County. (Comfortable meaning- 1/3 of your take-home)

Canyon county is much the same as Ada County.

One more tidbit I learned from this seminar --- The Fair Housing Act supersedes any state law. Interesting. Where am I going with all this? It does seem our worth, as an individual, is based solely on how much money we either earn, or have. Our importance within a social structure diminishes the closer we get to the poverty line. Dip below it, and our lives seem barely perceptible.

I’d be a number, even though I’ve done many good things in my life.

And yet, many of the people I admire, both living and passed, started out well below the poverty line. Their days spent in the trenches made them better people for having lived through it. Our value as a human being should be based on merit, not what car we drive, or trendy apartment we can afford. We should not be filed away as a number, simply because we cannot afford the luxuries a small percentage can. We are not a commodity. Every life counts for something......and at the risk of sounding cliche, we matter.

My son asked me, at the end of our last dinner, why I grieve so hard over people that I’ve never met. I thought about it for a second and replied, “Every life extinguished too early, is a potential voice for change. A change, now, never realized. I guess my kids will have to speak for them.”

Driven to Survive, Determined to Help

By Molly Balison

Cassidy Landry’s Ford Escape was her safe haven for nine months. In 2019, she became homeless as a result of domestic violence and the loss of her job. Coming from Texas, she knew few people and had little to no knowledge about resources in the area.

The first night she climbed into her makeshift bed in the backseat of her car, she cried more than she slept.

“The day I became homeless I was in denial,” Landry said, “I thought: I am smart, nice and good, how could this happen to me?”

When the sun rose the next day,

so did Landry’s motivation. She researched every resource and made a list that branched into a tree of services.

“You have to do things you normally wouldn’t do or never thought you would do to survive. It takes a physical and mental toll.”

When surviving out of her car, Landry lived off of food stamps and a $10 gas voucher. She said she has no idea what she would do if the Boise Police Depart-

ment fined her $10 whenever they found her lingering in a parking lot.

Idaho’s new anti-camping law — formerly known as SB 1141 — makes survival like Landry’s illegal in hopes that safety and sanitation will improve.

“This law could have destroyed my chance to rebuild. Instead of being arrested or fined, I got help. Idaho provided resources that allowed me to get stable housing and rebuild my life. That is how I know that criminalizing homelessness is not the answer,” Landry wrote on her change.org page where her petition against SB 1141 reached almost 1,000 signatures.

She created a 30 page propos-

My Journey One Step at a Time

I slowly walk with my walker, pushing myself on through the garbage-scattered streets. The heat evaporates the urine stench, and I hear a few hellos or grunts of greetings. This is part of my life. Yet when I open the door of the Phoenix, peaceful energy surrounds me as I step into the cool interior. Here are my friends from Project Well-Being, the mental health program, as we get ready to start our day. I have two worlds in one. Outside the walls are street people, some from the shelter and the rest from around. Most look tired, desperate, or are smiling. Many cultures and many different stories. We are all homeless, taking one step at a time to get to our next phase. Some will fall for alcohol and drugs, others into mental illnesses. A few will luck out to get our golden ticket, low-income housing. I keep trudging along until my golden ticket comes through.

If income doesn’t hold us back, all the fees just to apply and have good credit will. Then we need 2.5 to 3 times more income than rent, while Boise’s rental market is beyond most of our incomes. So many hoops to jump through.

So my friends help me when my steps falter and pick me up when I can’t stand. The Project Well-Being program helps keep me going by lifting my spirit and mental well-being. My art and writing also give me a voice and give me peace. Each step leads me to a better life. By my last steps, I will be home.

al full of research and ideas to launch an incentive program to help displaced individuals get back on their feet to present to the state to amend the bill in the next legislative session. Landry said that if her program was piloted for 100 individuals over 24 months. It would cost the city of Boise 1.8 million dollars which she believes the city could have the budget for.

“Regardless of how smart you are and how educated you are, when you go through homelessness and and a career gap…in reality it causes hindrance to get back on your feet.”

Landry’s lived experience fueled her motivation to start a nonprofit, Resource Link Idaho. It’s an online one stop shop for all

the resources an individual in need could ask for. She created the resource she wished she had when she hit the lowest point of her life in hopes that someone else can have a better chance at survival.

Julie Loomis