Spatial Folders

Extraction – A trans-scalar inquiry

Shonali Shetty

Shonali Shetty

Contents

Foreword: Untangling Complexities. Re-thinking future practice and extractivism from an ethical perspective

¶ Jane Rendell

Introduction: Title

¶ Golnar Abbasi and Kris Dittel

Leaking, Billowing, Shame

¶ Natasha Marie Llorens

235 ? ? ? ?

The Hidden Shadows of the Belgian Colonial Past: Deconstructing the aesthetics and materials of Belgian colonisation

¶ Elien Vermoortel

Post-Petrol Present: The emergence and decline of petro-dependent cultural spaces in Neusiedl an der Zaya

¶ Agnes Tatzber

Forest Metamorphoses: Revealing the traces of the Ips typographus epidemic in Fiemme Valley

¶ Shiila Infriccioli

The Unstable Ground

¶ Eva Garibaldi

The Block

¶ Dominique Willis

Reproductive Wilderness: Decolonising the womb from the anatomical and biocapitalistic regimes of architecture

¶ Shonali Shetty

Afterword: The Newsstand

¶ Alex Augusto Suárez

Contributors

Acknowledgments

Image Credits

Colophon

1 In the special issue of Textual Practice focused on Extractivism co-edited by Imre Szeman and Jennifer Wenzel, Justin Parks argues that “the term has emerged out of a Latin American development studies context to assume a place beside related concepts of the environmental and energy humanities such as the ‘anthropocene’ and ‘petrocultures’” (Parks, 2021, p. 353). Park refers to the in uential work of Alberto Acosta (Acosta, 2013).

Foreword:

Untangling Complexities. Re-thinking future practice and extractivism from an ethical perspective

¶ Jane Rendell“The relations between extraction as a concrete, physical practice, on the one hand, and extractivism as the cultural and ideological rationale that either motivates extraction or is the consequence of it, on the other, are necessarily complex and dif cult to untangle” (Szeman and Wenzel, 2021, p. 508).1

As a white researcher working in a highly privileged university in the Global North, the experience of extraction I want to open with here is not direct but mediated through practices of extractivism. Several years ago, when I was Vice Dean of Research at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, the university decided to accept a charitable donation of US$10 million from the Anglo-Australian multinational mining and petroleum company BHP Billiton to create an International Energy Policy Institute in Adelaide as part of UCL Australia, and the Institute for Sustainable Resources at the Bartlett in London.

2 “ESG due diligence” is a term used to assess the risks of a corporation’s policies and practices relating to environmental, social, and governance issues, (Exiger. 2023); while the term “social licence to operate” refers to how far the procedures adopted by a corporation are socially accepted by employees, shareholders, consumers, and the general public (Investopedia. 2021).

See also Jane Rendell, “Giving an Account of Oneself, Architecturally,” Journal of Visual Culture, v. 15, n. 3 (2016); and Jane Rendell “Hotspots and Touchstones: From Critical to Ethical Spatial Practice,” Lorens Holm and Cameron McEwan (eds) special issue on Architecture and Culture, Architecture and Collective Life, (2020).

Despite the role I held, I was not consulted, and only found out about the donation eighteen months later. Purchasing a report from RepRisk (RepRisk, 2023), an independent company that maps and estimates corporate exposure to reputational risk, I discovered that BHP Billiton were in danger of breaching some of the ten principles of the United Nations Global Compact (United Nations Global Compact, 2023), particularly those concerning human rights and the environment. As a result, I found I disagreed with UCL’s decision, and while remaining an employee of the university, stood down from my institutional role as Vice Dean of Research. I understood the acceptance of this donation to pose a con ict of interest, allowing BHP Billiton to buy legitimacy for the continued mining of fossil fuels and potentially in uence research into sustainability. My decision led to extended conversations with colleagues concerning institutional ethics, gift-giving, and cultural in uence, and exposed me to the language of corporate governance and critical discourse around the extractivist industries, such as “ESG due diligence”, the “social license to operate”, and “green-washing”.2

My encounter with extractivism, although several sites removed from the practice of extraction itself, began an ongoing process exploring the ethics of extractivist practices, which, following my architectural training, took me right back to the site of extraction itself. Despite the air miles this entailed, as part of month-long writer’s residency in Tasmania, I made a “pilgrimage” to Broken Hill, a city built on

stolen land and the “birth place” of BHP Billiton. In this town in the Barrier Ranges in the south of Australia, which was founded with the discovery of a mineral lode rich in silver, I started writing Silver for the series Lost Rocks, edited by A Published Event (Justy Phillips and Margaret Woodward) (Rendell, 2016 and Lost Rocks, 2016).

During my visit I found that the silver mine rst established by BHP in Broken Hill over a century earlier was being re-mined by a new company, and that the original site had become a tourist destination, complete with an abandoned café, shop, and monument to those who lost their lives in the mine. During my visit, an environmental disaster occurred in Brazil. The tailings dam of a mine operated by Samarco, a joint venture between Vale and BHP Billiton, ruptured in Minas Gerais and ore residues and mining waste ooded the surrounding area, causing Brazil’s worst environmental disaster, burying communities, leading to the death of seventeen people and displacing 725 others. Back in London, in response, the London Mining Network (London Mining Network, 2023), Diana Salazar and I co-hosted a conference – Speech (Extr)actions – in which people directly impacted by BHP Billiton mining projects not only in Brazil, but Colombia and Indonesia too, were invited to UCL to speak about their experiences (UCL, 2016). Speakers from communities, namely Luz Ángela Uriana, Letícia Oliveira Gomes de Faria, Maria do Carmo, Silva D’Angelo, Rodrigo de Castro Amédée Péret and Arie Rompas, among others, did so as part of a visit to London funded by the LMN, which allowed the delegates to attend BHP Billiton’s annual general meeting, thus making space to voice their experiences of the mining activities directly to the shareholders.

The title of our event raised the question of whether research activities, even when conducted in collaboration with participants and activists, could also be considered a practice of extraction (if not extractivism). One example could be collecting oral histories from researched subjects and including this in published papers without gaining the 7

full consent of the research participants. Working in careful participation with the LMN and the delegates, we hoped that our conference would not fall into the trap of extractivist research. Nonetheless, the title of the event worked as a warning ag, highlighting the need for all those involved to take seriously their ethical commitments to the experiences of those whose lives and livelihoods had been negatively impacted by mining.

Proposing that spoken words be considered as matter in relation to those materials extracted by BHP Billiton and corporations like them highlighted the distinctly different types of extraction at work. While those working in mines, and living next to them, face direct hazards – ranging from exposure to toxicity, to displacement and death – the dangers associated with research extraction are more indirect. One of the dangers is that when researchers, often from the global north, work with knowledge that belongs to researched subjects, often from the global south, they increase their own cultural capital, and so economic inequalities across racial and cultural divides. Making the work of Indigenous and other environmental activists visible in public, even with their consent, can also make them more vulnerable, especially in places where their lives are already under threat (Al Jazeera, 2022).

Extending the terms of extractivism away from extraction, as subject if not site, has been argued by Imre Szeman and Jennifer Wenzel in the environmental humanities to be something of a problem that can create “conceptual creep” and “ atten” important distinctions between historical, geographical, and cultural speci cities (2021). That is unless, as Szeman and Wenzel suggest, a critic looks re exively at their own practice and situation “so that possible (if problematic) homologies between, say, reading and mining loom large” (2021, p. 516).

Architectural research offers possibilities for exploring the potential of this re exivity precisely because of the discipline’s reliance on material extraction. In 2006, in Art and

Architecture, I suggested that artist Robert Smithson’s practice of relating site and non-sites, connecting the locations from which materials are extracted to those where they are rearranged in the gallery (Flam, 1996, p. 291, p. 178; Boettger, 2002, p. 67), could, transposed into architecture, help make visible the sites of material extraction on which the profession depends (Rendell, 2006). More recently, Jane Hutton has taken Smithson’s dialectic as her “structural prompt”, for “examining how the construction of a landscape in one place is related to transformation elsewhere” (2020, p. 2).

These processes of site-relating and self-re ecting are particularly important for architectural and interior designers, because their professional practice is based on material extraction. Critical discourse around extractivism points to the dangers of distances between sites of extraction and those of consumption and indeed research. This opening issue of Spatial Folders, dedicated to extractivism, addresses such distances, challenging the profession to remove the remoteness and make visible the practices of extraction on which most buildings are based. Explorations into the unstable relations between land and water at Lake Cerknica in Slovenia, the different scales of metamorphosis in the forest of the Fiemme Valley in Italy, and how a term like “block” can be considered from multiple perspectives –from slave-block to data-block – bring questions of material resource and extraction up close in ways that are both intimate and imaginative. Autobiographical approaches are also effective in drawing attention to gaps: the lived experience of a pregnancy is poignantly re ected upon to provide a tender account of the womb as a system of resource provision and delivery, while a family history produces a nuanced understanding of the tensions around resource extraction at Neusiedl in the Vienna Basin. Operating across intellectual and emotional registers, and involving immersive eldwork into speci c situations relating to extraction, this research provides a close engagement with the challenges at stake and, by untangling some of the complexities, re-thinks the place of extractivism in future practice from an

References

Acosta. A. 2013. Extractivism and Neoextractivism: Two Sides of the Same Curse. In: Lang, M. and Mokrani D. eds. Beyond Development: Alternate Visions from Latin America, Amsterdam: Transnational Institute and Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

Boettger, S.2002. Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties, Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 55–8 and p. 67.

Flam, J. ed. 1996. Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 291, p. 178, p. 244, and pp. 152–3.

Hutton, J. 2020. Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements. New York: Routledge.

Parks, J. The poetics of extractivism and the politics of visibility. Textual Practice, 35(3), pp. 353–362.

Rendell, J. 2006. Art and Architecture: A Place Between. London: IB Tauris.

Rendell, J. 2016. Giving an Account of Oneself, Architecturally, Journal of Visual Culture, 15(3). pp. 334–348.

Rendell, J. 2016. Silver. Hobart: A Published Event.

Rendell, J. 2020. Hotspots and Touchstones: From Critical to Ethical Spatial Practice.

Architecture and Culture, 8(3-4), pp. 407–419.

Szeman, I. and Wenzel, J. 2021. Afterword: What do we talk about when we talk about extractivism? Textual Practice, 35(3), pp. 505-23, p. 508.

Al Jazeera. 2022. Colombian environmental activists deluged by treats. [Online]. {accessed 4 February 2023]. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/ news/2022/5/9/colombianenvironmental-activistsdeluged-by-threats

Exiger. 2023. The ESG Due Diligence Process – Why It’s Important in 2023. [Online].

[Accessed 15 February 2023].

Available from: https://www. exiger.com/perspectives/esgdue-diligence-process/

Investopedia. 2021. Social License to Operate (SLO): De nition and Standards. [Online]. [Accessed 15 February 2023]. Available from: https:// www.investopedia.com/ terms/s/social-license-slo.asp

London Mining Network. 2023. [Online]. [Accessed 4 February 2023]. Available from: https:// londonminingnetwork.org

Lost Rocks. 2023. [Online]. [Accessed 4 February 2023]. Available from: https://www. lostrocks.net/

RepRisk. 2023. [Online]. [Accessed 4 February 2023] Available from: https://www. reprisk.com

UCL. 2016. Speech Extractions Witness, Testimony, Evidence in

response to the Mining Industry. [Online]. [Accessed 4 February 2023]. Available from: https:// www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/ development/events/2016/oct/ speech-extractions-witnesstestimony-evidence-responsemining-industry

United Nations Global Compact. 2023. [online]. [Accessed 4 February 2023] Available from: https://www.unglobalcompact. org

Editorial:

Extraction – A trans-scalar inquiry

¶This publication is the rst issue of Spatial Folders, a thematic periodical that is produced by the faculty of Master Interior Architecture: Research and Design (MIARD) program at Piet Zwart Institute, Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam. It is composed of a selection of graduation theses alongside contributions by guest authors that focus on urgent socio-cultural, socio-political, and ecological issues that affect the (built) environment and its representation regimes.

This rst issue focuses on extraction and extractivism that characterises the power structures that make our worlds and their historicities. Across time extraction processes have been making and changing the spaces of the world through displacement of bodies and matter, from within and across the earth. At the same time, these processes establish epistemologies and forms of representation that articulate extraction as natural or inevitable within the frameworks of anthropocentrism, capitalism, colonialism, racism, or hetero-reproductivism.

This collection of texts approaches the question of extraction from a variety of spatial perspectives. The contributions zoom in to speci c sites, cases, and areas of interest while providing a critical analysis of various networks of power and in uence across time and space. The close readings of selected sites point to the systemic effects of processes of extraction that remove, deplete, and uproot matter, bodies, and information simply to utilise them elsewhere. Extraction, through this process of distancing, physical or otherwise, conceals and abstracts the effects of such removal and renders them invisible. In this sense, the violence at stake here is not only in the extraction process but also the naturalising forces that erase and anaesthetise the modes of perception and experience that would allow the recognition of that violence. The eviction of matter and the erasure of its displacement from world-historical reality through modern aesthetics is what Rolando Vazquez describes to be a double erasure.1

While focusing on speci c sites of analysis, the authors also lay out systems of extraction that operate on multiple scales simultaneously. Hence their subjects require a trans-scalar understanding of the processes and sites of extraction and their residual representations, not in isolation but across spatio-temporal scales. This points to the interconnected nature and systemic understanding of the effects of extractivism.

The authors consider the roots of this economy of exploitation intrinsic to the de nition of hard borders and binaries in the colonial-capitalist project of violent exploitation – in the name of the fantasy of in nite growth; borders between nature and culture, the human and those seen as lesser-than. These works do not turn away from the material aspect of extraction but rather closely trace the spatial and material conditions and consequences of extraction in the case of oil, hormones, milk, wood, and water, among others.

Natasha Marie Llorens’ essay “Leaking, Billowing, Shame” considers the distance between the sites of extraction and

their sites of consumption, both materially and in representation. She proposes to turn to embodiment and abjection of bodies left in the wake of extraction to be the leaking sites that can help close this gap. Thinking through three distinct art works – Cooking Sections’ trilogy on salmon farming industry, Allan Sekula and Noël Burch’s lm The Forgotten Space, and Sondra Perry’s lmic work Flesh Wall – Llorens argues that to work through this gap is not only to oppose the violence of extraction itself but also to deconstruct the naturalising representation that erases this violence from the imaginary.

Shonali Shetty in “Reproductive Wilderness” considers the womb as a socio-political space by reading into its human and non-human entanglements, a view neglected by the anatomical gaze on the womb as a reproductive organ. Shetty draws a parallel between the representative historiography of the womb and that of architecture, framing them both as part of the same epistemology of control and capture. Opposing the ever-present reading of the womb as a singular, isolated entity, Shetty focuses on the material and trans-corporeal circulation of the womb and its associated matters (e.g. milk, hormones) that are, in part, a result of capitalist extraction. In Shetty’s reading, the womb becomes an expanded and networked space that accounts for difference.

In “Post-Petrol Present”, Agnes Tatzber examines the socio-political, cultural, and economic effect of oil extraction and the ways in which it structures space in the area of Neusiedl an der Zaya in Austria – both in the era of peak oil extraction and in the contemporary. The essay looks into the forms of (industrial) labour, forms of life, and the spaces created by the grammar of oil extraction and the ow of oil through the world, focusing speci cally on sites of leisure – such as a (now defunct) oil museum and a former swimming pool. At these sites Tatzber reads interconnected oil interiorities shaped by extraction from the body of the earth which then continue to shape what comes to the crust of it.

“The Hidden Shadows of the Belgian Colonial Past” investigates the coloniality of objects in Belgian domestic interior. From the living room it moves through a range of interior spaces to trace the colonial displacement of material bodies: across a world fair interior, the port of Antwerp, and the hold of a ship. Elien Vermoortel’s material encounter with the public statue of Leopold II in Ostend lands this investigation in the presence and representation of colonial inheritance in Belgian public space. The writing not only thinks about the colonial entanglements of objects and spaces, historically and in the everyday, but also stages the visibility of colonial traces that were otherwise concealed in the interior and in public space.

“Forest Metamorphoses” articulates the spatiality of the Fiemme Valley across temporalities and scales through readings of its slow ecological breakdown, which is a result of extractive community, cultivation, and forestry practices. Contextualised in climate collapse discourse in architecture, Shiila Infriccioli narrates the valley’s spatio-temporal conditions through stages of the forest’s metamorphoses: rst, deconstructing the popular capitalist imaginary of the forest, then moving on to the legal, geographical conception of it as a territory – the human-made transformation of the site into tree monocultures – and lastly zooming in to the ecological micro-agents such as beetles that are continuously reshaping the space.

In “The Unstable Ground”, Eva Garibaldi researches a uctuating water mass in Slovenia, Lake Cerknica, and the surrounding land that is constantly “built and unbuilt by water” as groundwork for the deconstruction of the idea of the land as stable and immutable. The contested and con icting cultural, political, cartographic, and visual narratives produced around this site continue the colonial and capitalist imaginary of a stable ground based on extractive paradigms of productivity and (certain forms of) cultivation of land and water. Gharibaldi’s essay destabilises this imaginary by reading into the complexities of the amphibious landscape of this lake as a paradigmatic instance.

Dominique Willis’ essay, “The Block”, articulates processes of extraction and abstraction of spatial matter, from land to the human body, to argue for an understanding of space that is abstract(ed) and in a state of constant becoming. By thinking through the notion of the block as an “informational unit”, Willis underlines this extractive abstraction of physical and other matter as becoming information. This is used to theorise the exploitative histories of land commodi cation, the plantation, slave ownership, and information capitalism. It offers a provocative, intersectional, anti-capitalist, and anti-colonial argument centred around the material consequences of extractive processes of abstraction as the marker of spatial grammar of today.

Forest Metamorphoses: Revealing the Traces of the Ips

Typographus Epidemic in Fiemme Valley

Shiila Infriccioli

Introduction

“But what happens when we are unsighted, when what extends before us – in the space and time that we most deeply inhabit – remains invisible? How, indeed, are we to act ethically toward human and biotic communities that lie beyond our sensory ken? […] Such questions have profound consequences for the apprehension of slow violence, whether on a cellular or a transnational scale.” (Nixon, 2013, p.15)

Contrary to what the static nature of alpine scenery portraits or picture postcards might suggest, mountainous landscapes are hidden, complex, and unexplored worlds, slowly but perpetually transforming over time. Organic matter is not stationary by nature: nothing remains the same, not even the mountains, the great boulders, the valleys. Neither do the forests, as places of imaginative redemption that inspire a sense of relative eternity, compressing and expanding in times far longer than human life, so that their becoming is almost imperceptible to the eyes of one single individual.

Metamorphosis is a principle embedded in forest ecosystems and the foundational aspect of their vitality. As the result of the collaboration of countless microorganisms, forests are profoundly and constantly active, revealing the in iction of ecological violence through insidious acts of contamination and manifesting themselves in their resistant aliveness, in a continuous state of becoming.

Nevertheless, since the increase of Europeans’ knowledge of materials and their properties, extractive practices have neglected ecosystems’ dynamisms, unhearing the voices of non-humans, relegating them to the category of resources for investment, with alienation, that is, the ability to stand alone, as if the entanglements of living did not matter (Tsing, 2021, p. 5).1

Understanding the violence embedded in ecological breakdowns and acknowledging the slowness of their becoming

requires considering a temporal scale that goes far beyond a singular human lifespan: to think of the forest as an active metamorphic space means to engage with a decentralised temporal paradigm. The notion of decentralised time can be explained through the concept of foresight that applies to the gure of the forestry technician. During an interview with Ilario Cavada, the forestry technician of the Fiemme Valley in Italy, I realised that forests’ metamorphoses manifest beyond what a singular human life can observe.

1 Anna Tsing stretches the term “alienation” from Marx’s denition: from the separation of the worker from the process of production (re: Karl Marx, Economic economic and philosophical manuscripts of 1844, Mineola, NY: Dover Books, 2007) to consider the separation of non-humans as well as humans from their livelihood processes.

2 By slow violence Rob Nixon means a violence that “occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all” (2013, p. 2).

“This concept of time is the concept to which our work as foresters is most closely linked, and often no one understands because by now everyone is accustomed to maximum speed, to the computer, to an immediate response, to immediate news. I am working not to see the effects myself but for my future colleagues in 100 years. We have to have a very developed concept of foresight, which is not needed in many other professions.” (Cavada, 2022)

Decentralised time adaptation happens precisely because to be in contact with the forest means to think in time with the forest, whose, as we will see, ecological metamorphoses are happening with much-delayed effects. Therefore, as the forester tries to apply foresight to see what will be beyond him, to engage with the forest’s current ecological state, we need to pay attention to what extends before us. (Nixon, 2013, p. 15) In this optic, contextualising the historical roots of exploitation practices could help unfold the multi-layered, “slow violence”2 of extractive narratives in ways that uncover ecological disturbances as single, destructive, and direct cause-effect events (Nixon, 2013, p. 2).

To question the very womb of humans’ cultural practices at the roots of ecosystem breakdowns is also to raise attention to non-human agencies. To shift the subjectivity of these stories and reveal profoundly unfamiliar perspectives is key to re ecting on the temporal anthropocentrism that characterises sustainable development narratives, where the focus is always projected into the future, to design production processes that optimise the emerging scarcity of natural resources instead of questioning the violence of the ideological seeds that were planted centuries ago. The decay of natural resources and environmental disruptions are intrinsically rooted in our past. In Nixon’s words, “we need to account for how the temporal dispersion of slow violence affects how we perceive and respond to […] environmental calamities”, by revealing the stories of ecosystems’ silent aliveness and resistance (2013, p. 3).

Following the stories engraved inside the trees of Fiemme Valley, I will unfold a rami cation of terrain events that happened over centuries, where every story has a single scale, neatly nestled in the current forest substratum. Even at this moment, the delayed effects of these happenings are branching out in a perpetual act of transformation.

Ecological Violence Through Means of Silent Representation

“Our forests are not natural. They are forests that man has managed for centuries; we have human management of the wood. Humans started using and planting the forest thousands of years ago; it is like a form of domesticated animal.”

(Bellù, 2022)

“A natural forest cannot be a forest where you walk in a very regular way because a natural forest has different vegetation development at every height.” (Cavada, 2022)

On the outskirts of northern Italy, almost at the border with

Austria, Fiemme Valley extends on an east–west axis along the waters of the Avisio river. Surrounded by the impressive Dolomites mountain ranges, where the highest peak rises to 2847 metres (Peak d’Asta), the valley is covered by villages, meadows, pastures, and forests teeming with conifers, shrubs, and undergrowth shrubs. The trees surrounding Fiemme Valley belong almost exclusively to the community named the Magni cent Community of Fiemme, which currently owns 20,000 hectares of forest.

This circumscribed woodland, where the presence of humans has been perpetual and instituted by the same social group that identi es itself through well-documented rituals, cultural practices, and traditions, is a critical case study to unfold slow eco-political metamorphoses as the result of the millennial cohabitation of humans and forest through a decentralised time paradigm. However, before entering the complexity of these becomings, I rst need to engage with the very representational aspect of this ecological space. The seemingly wild scenery of the Dolomites is a clear example of how the image of the natural world operates on multiple layers of complexity, including aesthetics, infrastructures, and politics. From a structural point of view, Fiemme Valley’s forest can be considered designed for exploitation as part of an infrastructure of the landscape, whose wild aesthetics promoted by mass-tourism narratives are attempting to bury the memory of ecological violence permeated over millennia.

To engage with this representational aspect without falling into simplistic dichotomies such as the “natural” and the “arti cial”, I will distinguish between the terms “woodland” and “forest” to uncover the complexities of the agencies that are commonly related to “tree covered” environments. While woodlands are by de nition a growth and extension of woods that are controlled, managed, and cultivated by humans, the forest is usually de ned as an area of wild land, not controlled by humans, in which the vegetation grows spontaneously and consists of herbaceous plants, bushes, and in particular tall trees. The forest, precisely because

of its wild nature and its distance from human control, has always exercised a particular fascination in the collective imagination: the word itself, in its very etymological meaning, derives from the Latin foris, which means “outside”, and forestis silva “forest outside the fence”, de ning a place “outside the built-up area” and therefore solitary and wild. In the common imagination, the forest is seen as a foreign space, mysterious, disconnected from what happens in the city, a hardly civilised space.

Human presence, control, and agency are what seem to differentiate an area considered wild and therefore natural from a domesticated and cultivated one. However, there is a liquid boundary between these de nitions, made of nuances and complexities, variously discussed but not yet solved by semantics or legislation. Moreover, the cultural perception of these environments is made blurrier by the dif culty of the human eye to perceive a cultivated forest from a seemingly wild one. This grey area and gap in perception are at the centre of the instrumentalisation of the image of the natural by the tourism industry, whereby massive attractions often describe these landscapes as places to occupy to enjoy rituals of redemption from the arti ciality of the city.

Ecological violence also operates through means of this cultural perception, where the landscape’s picturesque aesthetics and the narrative of the natural neglect stories, vicissitudes, and aliveness in the name of economic interest. Because of this successful strategy, the stories of these landscapes are not spoken, and the forests are still considered leisure spaces rather than places embedded with memories. This romanticised image, which intends to attract an external audience by portraying the mountain as a recreational space, inevitably leads to a lack of awareness and care towards the forest as a complex metamorphic space that carries the wounds of centuries of human activity, “leading to an emptying out of traditions, cultures, knowledges which are then also re ected in the maintenance of the territory from both an environmental and a management point of view” (Giacomuzzi, 2022).

Mass tourism is not directly linked to the material exploitation of the forest more than it is to the degradation of its soil, but it is certainly helpful to understand how representational leaps and extractive violence are two sides of the same coin. Making the landscape accessible to the masses is a concept that was rst established by Fascist propaganda. The imagery of the natural landscape and its wilderness narratives started to circulate as a strategy to commercialise the landscape in the name of economic development. In order to circulate images that would attract the masses to consume the landscape, the Italian tourism agency adopted “Le Vie d’Italia” as its of cial slogan, “promoting the basic approach to tourism promotion: turning places into commodities and convincing potential consumers of their beauty” (Armiero, 2011, p. 101).

“It will be necessary to clear the land of the coppices that cover it where necessary to see how many tall trees there are, layout convenient paths, and even have the courage to start abundant plantations of ornamental trees, especially conifers of the varieties favored by the villas.” (Bertarelli, 1909, cited in Armiero, 2011, p. 102)

Today, the valley’s forests are criss-crossed by more than 200 kilometres of footpaths, together with the valley- oor bike path and the ski facilities. The seasonal offer is also enriched by exceptional events such as the Marcialonga (long march), a famous international Nordic ski competition that attracts 30,000 visitors and generates an income of almost €8 million (Martellozzo, 2020, p. 45).

It is precisely when humans have access to the landscape –when its vegetation begins to be modi ed, tread on, and uprooted to adapt to the creation of infrastructures – that the forest can no longer be considered something distant from humanity. The accessibility that the human has in the space, and sometimes the violence and the magnitude with which this agency manifests itself, initiates slow, violent, and silent metamorphoses. Nevertheless, accessibility to resources is not something equal; its rede nition happened

throughout history through inclusion/exclusion processes. To become an infrastructure where power is centralised, forest resources management has undertaken a process of marginalisation of all the uses that con icted with the idea of the forest as a productive and exploitable space. Besides the folk idea of being “outside society”, the forest is precisely a constructed socio-ecological space whose characteristics are morphed by speci c societal power structures.

Metamorphosis One: Ownership and independence

The destructive effects of extractive economies are frequently discussed as the result of modern-industrial capitalist cycles, but the standardisation of the Fiemme Valley’s forest and its slow transformation into a production space goes far back in history. Fiemme Valley has always been a territory deeply marked in its culture and economic vicissitudes by the ow of raw materials, where economic ties have bound the Tyrol to other parts of Europe since at least Roman times (Cole and Wolf, 1999, p. 168). Therefore, to understand the economic importance of forest resources in the past, it is essential to start from a broader time scale. The rst metamorphosis is enacted by human agency and occurs through the de nition of the concept of privilege linked to the accessibility of forest resources. However, to think of being able to tackle the complexity of millenary ecological and social transformations that modi ed access to Fiemme Valley’s forest resources is not the aim of the theorisation of this metamorphosis. Rather it is to outline the complex and subtle establishment of societal power structures.

“Community forestry has a long tradition in Italy, dating back to the beginning of this millennium” (Morandini, 1996, p. 1). According to historical references to the alpine landscape and its resource management forms, communities based on common need and thus on collective use of the forest were

present throughout the mountain territory, characterised by agroforestry-pastoral economies. However, over time, the majority of the original collective premises of these communities have been profoundly modi ed. In Italy, “political changes made it possible for elites to redraw the legal and illegal borders in hybrid spaces such as forests and erase any alternative way to access natural resources” (Armiero, 2003, cited in Biasillo and Armiero, 2018, p. 2).

As previously stated, the Magni cent Community of Fiemme currently owns 20,000 hectares of forest in Fiemme Valley. This community is a social formation that already existed 1000 years ago, where it appeared as the owner of 12,000 hectares of forest and 60 million trees. Its autonomy was ofcially recognised as early as 1111 by the Prince-Bishop of Trent in a document called the Patti Ghebardini and was repeatedly reaf rmed in the following centuries. The so-called Enrician Privilege of 1314 gave the inhabitants of Fiemme direct common ownership of their land, forests, pastures, and all related land-use rights, including wood harvesting, grazing, hunting, and shing. One of the primary goals of the community’s foundation was to keep the pastures in question intact and, if possible, to expand it so that each member could receive sustenance from the resources it provided, even in the face of severe economic hardship (Dossi, 2021).

The Magni cent Community of Fiemme was primarily characterised by a unique system of ownership rights and the use of natural resources. The community brought to light a network of uses and access rights which, taken as a whole, constituted an alternative way of thinking about nature, whereby forests were seen as more than the algebraic sum of soil and timber: they were complex ecosystems made up of topsoil, trees, banks, woodlands, livestock, pastures, water, and wild fruits (Armiero, 2011). In fact, for the inhabitants of Fiemme Valley, the common lands didn’t only have an economic function but also played an essential role in strengthening community cohesion and consolidating the original ties between the inhabitants. All the inhabitants could obtain rewood for cooking and heating in the common woods. Wood

could also be cut for domestic use, for example, building or repairing houses or making handcrafted furniture, and for village use. Common woods also produced potash, resin, tannin, and animal bedding (Bonan, 2016).

Ecological violence is modelled on the political violence enacted on human beings, by simplifying ecologies and centralising power over resources (Ghosh, 2021). The scienti c standardisation of forests in the eighteenth century, in particular, has its roots in timber management and Venetian markets, both of which had a signi cant impact on the Fiemme Valley. An example can be traced back to the rst legislative provisions approved as early as 1527, under the name “Instrumento de li Legnami”. This legislation regulated collective access to forest resources, since collective use was the main reason for the forest’s “wear and tear”.

In reality, the Venetian merchants were responsible for the ecological damages due to excessive wood extraction. Rather than seeing it as an asset to be protected according to ancient customs, Venetian merchants saw the forest as a “green mine”, which anticipated and prepared the ground for a modern approach to forestry practices.

The transformation of the commons during the nineteenth century is a crucial moment in understanding the re-articulation of Fiemme’s community heritage. As the process of centralisation of power progressed, the ecology of the forest and its inhabitants were not considered in the vision of the forest as a productive machine. The common use of the forest has been threatened numerous times throughout history, giving rise to stories of political resistance, such as the insurgency that occurred in 1809 in Predazzo, a village in the Fiemme Valley, when peasants protested for the preservation of their autonomy in contrast to the modernisation of the state that was taking place in Europe. During this historical era, social structures based on the idea of the common property went through a metamorphosis to make room for legal forms of private ownership. In particular, after the annexation of Trentino to the Kingdom of Bavaria in 1805, by the decree of 23 January 1807, the “Regolanie Maggiori e

Minori” was abolished and the modern municipality was set up in its place. The central aspect of this process involved an organisational transformation that led to the abolition of all legal and institutional competencies of the rural communities and their replacement with modern municipal corporations (Bonan, 2016, pp. 599, 1). However, as Bonan states: “The state intervention did not cause the end of the common institutions but instead caused a general rede nition of who could use these lands and how these lands could be used ” (2016, p.1). These political processes happened slowly and silently to avoid social turmoil. On the one hand, the law prescribed the cancellation of peasants’ customs, and on the other, it provided communities with an exemption for subsistence purposes (Biasillo and Armiero, 2018, p. 5). Under these new laws, the mountain forests were considered an asset that the state should preserve to ensure long-term supplies for cities’ needs; this protection was directed against alpine communities who lived close to the forest and exploited the forests to survive (Whited, 2000, cited in Bonan, 2016, p. 591).

Increased control over the rural area, and economic and social changes affected peasant communities, leading to social differences (Bonan, 2016, p. 599). While management according to a standard policy lasted a long time in Fiemme Valley – and the community is still managed autonomously today – this did not imply equal access to shared resources. Only a small number of families had direct or indirect in uence over the functioning of local institutions, especially those who, although members of the local community, could interact with political and economic structures larger than those of the local village and thus act as intermediaries between the centre and the periphery (Bonan, 2016, p. 601). In this sense, “ownership and management can be distinguished, but when management is given so many powers, the most important of which is linked to pro t, ownership, even if ‘public’, becomes essentially private” (Farol , 2010, cited in Salis 2012, p.5) .

No matter how remote or distant a mountain village is or how different its management premises and natives’ ties

to their land are, it does not exist in isolation but maintains contact with other external actors (Cole and Wolf, 1999) and develops links with larger politics and economic interests, increasing damaging practices. When mass timber extraction linked to major external economic interests began, the commons saw their right to access resources taken away from them.

In Trentino, deforestation, caused by the increasing use of wood resources, led to an inevitable degradation of the forests, which at the beginning of the nineteenth century were at their lowest coverage. This led to the need to establish a faster infrastructure for reforestation, favouring the planting of commercially exploitable species over non-profitable ones, which profoundly in uenced the forest’s biological composition. The development of forest management in the name of economic exchange is certainly not the only threat to landscape conservation, but it is undoubtedly “the one that produces the most dramatic and irreversible effects” (Agnoletti, 2013, v).

Metamorphosis Two: From seeds to landscapes

“The nursery is like a school for trees, I am like a r tree nanny.” (Zanetti, 2022)

With the introduction of the forest nursery, the forest is translated from a space of production to a space of reproduction. Although the concept of the forest as a productive space have existed since the seventeenth century, it could not be considered fully optimised from a production standpoint until the practices of producing, propagating, and planting trees for reforestation were established. At this point, exploitation becomes supported by an infrastructure, allowing for greater and more systematic control over extractive practices. The forest nursery conceptually represents the desire to transform the forest into a proper

infrastructure of organised reproduction; this transition occurs as a result of the realisation that the natural regeneration time of trees in the forest does not correspond to those of mass consumption. The second metamorphosis happens between the agencies of the human and the forest. Starting from the scale of the forest nursery, it explains how the reproductive ritual of arti cial tree planting is at the heart of massive landscape modi cation.

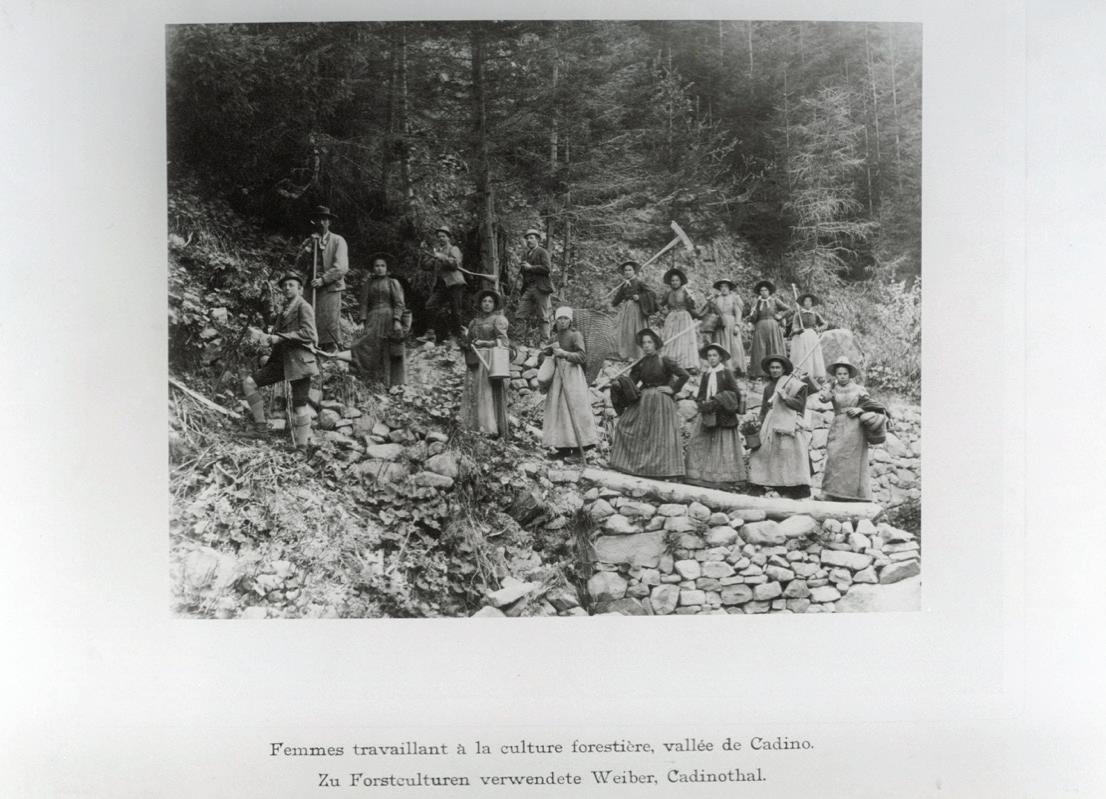

For the Fiemme Valley, Francesco Meguscher, chief inspector of the Tyrolean and Vorarlberg forests, drew up a reforestation project as early as 1831. Some sowing was done in 1832, and some plantations in 1836. From this period onwards, forest nurseries spread and increased rapidly in number (Agnoletti, 1998, p. 179). Arti cial tree planting, as a form of ecological simpli cation in which living beings are converted into resources (Tsing, 2016, cited in Martellozzo, 2021, p. 436), is a common practice in Fiemme Valley that is still observable today.

The practices performed in the forest nursery are closely linked to the passage of the seasons. While speeding up and propagating plants in numbers, humans are forced to act according to the climatic and environmental conditions favourable to the emergence of the seedling. The reproduction process begins in autumn when the seeds to be planted are collected from the cones of the trees. The cones are harvested in autumn because that is the season when they are mature. The years are not always fruitful; if pollination does not occur, the seeds are not fertile. The seeds are planted in the rst area of the nursery: the seedbed. Here they remain for two years in their rst growth phase. The second area is called the planter. In the transitional phase between these two nursery areas, a sorting process occurs: only the most “beautiful” seedlings are saved, i.e., the straightest and most robust ones. Once selected, the seedlings are placed in the planting house for four years, during which time the nursery worker will follow their growth by carrying out practices similar to the care of a vegetable garden: removing weeds, giving soil and water,

continuing the selection process. Once ready, the saplings are taken to the selected forest areas for reforestation. This process is very delicate; the saplings have to be harvested in spring before they wake up from winter when they are under “anaesthesia”. This is necessary because they are extracted bare-root, and a plant extracted bare-root is very fragile. The nursery is located at an altitude of 1400 metres in favourable climatic conditions so that the saplings can be planted in time in the forest; otherwise, they would germinate earlier. Once in the reforestation area, the young plants are placed by workers using an ancient technique: they dig a hole and place a stone next to the saplings’ roots, which keeps the soil moist in case of drought. Once placed in the forest, depending on the water, soil fertility, and deer that graze them, not all plants survive. There is a difference between a seedling grown in the nursery and one in the forest; the seeds that fall into the soil near the mother plant are much stronger. A seedling grown in the nursery tends to be weaker because it has not had to withstand competition. For this reason, even after being planted in the forest, the plants are still looked after for another two years. For example, weeds that could choke them in competition for light are removed. In the autumn, the saplings that have died are replaced. It is a time-based process, and there is only one month to do this reproductive ritual. Once the tree is eighty years old on average, it is selected and cut for old age, and the trunk is taken to the sawmill of the valley, where the logs will become semi- nished wooden boards and sold for the construction of houses, interiors, and furnishings. In Fiemme Valley nursery, 90,000 seedlings are currently produced each year.

The metamorphosis of the forest into a reproductive space happens through a web of human actors and actions: forest keepers, nursery workers, and loggers cultivate, replant, cut, and assemble the forest landscape. Through the banality of daily actions, they adapt the forest characteristics to the market’s demands, favouring the regeneration of economically more fruitful species over unproductive ones. Plant after plant, seed after seed, as a repetitive mechanism over the years, until the arboreal composition of the landscape is

completely altered. In this alienating process, the forest is not seen as an active entity, a living and complex ecosystem that lives according to delicate balances based on its diversity, but is simpli ed as a passive economic resource at the service of human economies. These rituals of reproduction reiterated over time have led to the neglect of species that do not conform to the standards of the forest as a productive space, a process of exclusion conceptually similar to the metamorphosis of the collective uses previously described. Currently, the alpine landscape of north-eastern Italy is a monoculture, which means that it is almost completely dominated by spruce trees that tend to be of the same age due to the centuries-old activities of using the forest for timber production (Agnoletti, 2020, p. 357).

In this metamorphosis, the concept of decentralised time in relation to ecological violence takes on one of its highest expressions and can be explained through the slow growth-process of the r tree. From the moment the seed germinates, the spruce tree produces a new growth ring each year, increasing the diameter of its trunk as time goes by. It is known that the (economic) maturity of this species –the moment when the trunk diameter reaches the conditions suitable for its productive use – is reached after sixty or seventy years, although the cutting rotation can vary, reaching over 120 years. Therefore, the current monoculture of r trees dates back to reforestations carried out from the end of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, when favourable market conditions accelerated the preference for this tree species. (Agnoletti, 1998, p.178)

In other words, the current monoculture results from ideological seeds planted up to 120 years ago that, with perpetual but slow growth, have led to the standardisation of the forest as a productive machine until it metamorphosizes the landscape. Fiemme’s forest is an anthropogenic territory with no secular forests, whose trunk diameters have thinned over time due to continuous logging (Agnoletti, 2020, pp. 186-87).

The production space of the forest nursery and its surrounding infrastructure is a clear example of how small-scale actions expand, generating a kind of transcendental violence to time and space, with a magnitude that goes beyond human perception, beyond the tangibility of things. In this sense, the unexpected metamorphoses generated by the scale of human actions affect spaces and times that are frighteningly extended beyond what our senses are spontaneously able to observe and acknowledge. These metamorphoses occur through a slow modi cation of the form of things due to a silent and permanent violence “that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive”, but not less striking (Nixon, 2013, p. 2).

However, a metamorphic system such as the forest could not be de ned as alive if it was not in a constant state of modi cation; its ecosystem, made up of thousands of collaborating organisms, could not be de ned as an active force if it remained passive to in icted violence. Each series of actions, no matter how distant in time, corresponds to a series of reactions, a series of delayed effects, which extend beyond the individual human being’s life. It is precisely the forest’s simpli cation and alienation and the resulting ecosystem imbalances that generate active resistance spaces.

Metamorphosis Three: Agencies of disruption

“We consider Vaia to be year zero, a watershed between what was before and what will never be the same again, never! An era has changed with Vaia. In the sense that we became aware of management, before we were more gardeners than foresters. A forest environment must be seen in a much broader way, not of the single plant, because you tend to lose the whole. The storm highlighted some of the weaknesses of Fiemme’s forests. One hundred years ago, when much of the ecological knowledge we have now was not there, the main aim was to make the most money

from the spruce, that once fed the whole of Fiemme Valley.”

(Cavada, 2022)

“Who can forget those moments when something that seems inanimate turns out to be vitally, even dangerously alive?”

(Ghosh, 2017, p. 8)

While the rst metamorphosis focuses on the historical violence embedded in the politics of access to resources, the second hints at how the landscape has been morphed into a monoculture as a result of intensive plantation practices. In the third metamorphosis, a new paradigm is established. Ecological disturbances and their slow becoming are removing the mask of extractive violence, changing the aesthetics, and morphing the forest into a space of resistance. Nevertheless, neglecting ecosystems’ dynamism does not eliminate their embedded aliveness; winds, microorganisms, and vegetation are adaptive, collaborative agencies whose acts of disruption manifest as delayed but non-less accountable effects.

Storm Vaia was an extreme weather event of Atlantic origin that affected north-eastern Italy, bringing exceptionally high winds and persistent rainfall for four days from 26 October until 30 October 2018. The wind gusts were powerful and catastrophic: the potently hot sirocco wind, blowing between 100 and 200 kilometres per hour for several hours, caused millions of trees to fall, with the consequent destruction of tens of thousands of hectares of coniferous alpine forests. In Fiemme Valley, millions of trees were blown down, revealing an apocalyptic scenario of destruction. Instead of the typical alpine landscape, where forests stand dense and dark green in swathes, an expanse of crashed, fragmented, and decomposed trees could be found.

The winds found a weakened landscape, deprived of its biodiversity. In recent studies, forestry experts found that the majority of the plants uprooted by strong winds on the night of Storm Vaia were spruce species, as forestry practices did not take into account the appropriate planting altitude conditions

for the resilience of these plants. Spruce roots are supercial and rarely penetrate the ground deeper than a meter, so they are relatively easy to uproot, especially in extreme climatic conditions. The ideological roots of extractive knowledges have not withstood the power of the winds of resistance, which generate a perfectly consistent image of destruction that was previously silent in the false beauty of an anthropic landscape. The anthropocentrism of extractive knowledges failed to acknowledge the complexity behind the vital equilibrium of the symbiotic relationships between tree roots and soil. Moreover, the monoculture cultivation created an additional imbalance in the forest’s regeneration mechanisms; as an active and regenerative entity, the forest is inhabited by in nite collaborating organisms. Following destructive events such as a storm, these entities are called upon to re-establish the balance.

A speci c “balancing” pathogen corresponds to each species, biologically designed to decompose the tree’s remains into organic substances. The spruce bark beetle (Ips typographus), together with countless other organisms, is the balancing pathogen of the spruce. Storm Vaia produced the conditions for the beetle to accomplish its biological function to transform the crushed trees into regenerative material to nourish the forest substratum. This insect is nothing more than a vector of Ceratocystis polonica, a fungus whose function is to regenerate dead matter into lively organic soil. The forest substratum, or the so-called humus, is an organic matter that supports the emergence of new organisms by sharing and providing vital substances to the roots of young trees and plants. In these processes, the agencies of fungi and beetles are indispensable, as they ensure life for successive generations of living beings through the perpetuation of the biological cycle, even after a catastrophe. This ecological reality would not correspond to damage in a condition of biodiversity. However, as seen in Fiemme Valley where entire hectares of forests are sprinkled with the same tree species, the beetles’ presence morphed from an endemic into an epidemic force that ultimately led to a second massive ecological catastrophe.

“The bark beetle is a beetle called a spruce weakling pest because it is species-speci c; it is the most famous because it does the most damage. But why does it do the most damage? Because we have too much spruce. The bark beetle has existed for as long as the spruce has existed; in a balanced ecosystem, it does not cause damage, but when there are events that disrupt the forest fabric, it is a foregone conclusion that a bark beetle epidemic will occur.”(Cavada, 2022)

What precisely turns the beetle action from an endemic silent state to an epidemic force are imbalances of forest ecosystems. The storm, bearing down on the monoculture, created the condition for this metamorphosis, as the bark beetle started to decompose dead trees and engrave into the suffering ones. This status transformation is particularly interesting as, in a sense, the insect could be seen as the biological indicator of an already damaged and threatened ecosystem.

The scienti c name Typographus refers to the characteristic pattern that the beetle engraves inside the trees. The insect’s engravings damage the phloem, a complex tissue in the vascular system of higher plants consisting mainly of sieve tubes that function in vital translocation of support and storage. Digging tunnels under the bark, the beetle leads the already suffering or damaged tree to decomposition, so its matter can nourish the soil and facilitate the birth of new plants. The process through which the beetle couples allows a spatial understanding of micro-dynamics. Under the bark, the male of the species builds a “room” and then emits pheromones, the chemical compounds through which the beetles communicate. The pheromones can attract up to four females. The females, in turn, dig corridors out of the room, in each of which about fty eggs are laid. Since the egg-laying process can take up to three weeks, some eggs hatch even before others are laid, digging further corridors. At birth, the larva feeds on the wood, digging further corridors which branch off from the initial one. The spruce bark beetle uncovers violent truths by digging invisible micro-spaces of resistance into the trees, transforming a

seemingly balanced reality into hyper-active landscapes. Reading the engravings that the bark beetle carves in the wood is similar to observing ancient cave paintings: they reveal stories rooted in the past by speaking a non-human language. As the ultimate metamorphic agent, the spruce bark beetle digs into the wood and changes the tree’s fate as a commodity, revealing stories of invisible violence perpetuated over centuries.

One of the effects that bark beetle outbreaks have on wood-commodi ed resources in the region is the blue-stain fungi. The spruce bark beetle, as the vector of the fungus Ceratocystis polonica, fungi of the genus Ophiostoma, carries microscopic fungal spores on its armour that leave blue traces on the wood, visible right down to the end products in Fiemme sawmill. The blue stain reduces the value of the wood sold for aesthetic purposes, such as interiors and furnishings. In Fiemme Valley, together with Storm Vaia in 2018, the beetle infestation damaged about 7000 hectares of r forest and about 3 million cubic metres of timber, produc-ing overall economic damage up to €350 billion (Redazione, 2021). As stains on the conscience of extractive practices, thousands of cubic metres of timber exhibit a silent but ashy change of aesthetic.

Nevertheless, the metamorphic forces of nonhuman agents in Fiemme’s forests are visible at different scales, from the damaged landscape to the spruce bark beetle engravings, to the stains on wood planks. Once again, metamorphoses are characterised by continuous, symbiotic changes, expanding beyond time and space. In this sense, the forest is a space in constant ux where the interweaving of all living elements is most vividly visible.

How to Turn a Deadly Matter into a Living Consciousness?

Exploitative ideologies creep into our present in a slow and in icting way but, inversely, nonhuman agents are manifesting a series of immediate and striking repercussions,

3 As Gosh theorises: “Recognition is famously a passage from ignorance to knowledge. To recognize, then, is not the same as an initial introduction. Nor does recognition require an exchange of words: more often than not we recognize mutely. And to recognize is by no means to understand that which meets the eye; comprehension need play no part in a moment of recognition.”

(2017, p. 11)

no longer invisible to human consciousness and perception. Looking at ecological disturbances through the past is an opportunity to recognise3 their more complex rami cations, to deepen our understanding of their roots. How do we acknowledge this aliveness so as not to fall into the mere reiteration of the violence of past practices? Nonhumans are proposing radical new scenarios and providing a groundwork to build from; they offer us an occasion to re-think responsibility through new temporal and spatial paradigms.

“Climate change involves outsourcing violence on such a vast scale – temporal outsourcing and geographical outsourcing. It is the ultimate form of incremental violence as it is shredding our planet’s life-sustaining envelope. Climate change can be mitigated only through a commitment – an ethical, political and imaginative commitment – to safeguarding people and other life forms that are remote from us in time and space. Such a commitment requires that we deeply value life thirty, fty, one hundred, one thousand years from now. Countering slow violence requires reimagining responsibility over longer time frames.” (Nixon, 2013)

Observing ecological breakdowns through dispersed temporal and spatial metamorphoses means raising awareness of unseen realities, realities that are extending beyond our lives and senses. We need to pay attention to microscopic worlds as well as larger truths to reveal how the violence of the past insinuates itself into the present in obscure ways. Only by acknowledging violence can we eradicate it, give freedom to nonhuman voices, to implement a responsibility that is conscious of the past, grounded in the present, and enduring in the future.

↑ Still from three-channel video installation Bark Beetles Weren’t a Menace Until Humans Tuned Them into One, Magni cent Community of Fiemme sawmill, Shiila Infriccioli, 2022.

↑ Still from three-channel video installation Bark Beetles Weren’t a Menace Until Humans Tuned Them into One, Magni cent Community of Fiemme sawmill, Shiila Infriccioli, 2022.

Bibliography

Agnoletti, M. 1998. Segherie e Foreste nel Trentino, dal Medioevo ai Giorni Nostri. Trento: Museo degli Usi e Costumi della Gente Trentina.

Agnoletti, M. (ed.) 2013. Italian Historical Rural Landscapes. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (Environmental History). doi:10.1007/978-94-007-53549.

Agnoletti, M. 2020. Storia del Bosco: il Paesaggio Forestale Italiano. Bari; Roma: Laterza.

Armiero, M. 2011. Le Montagne della Patria, Natura e Nazione Nella Storia d’Italia Secoli XX e XX. Torino: Einaudi.

Bellú, F. 2022. Interview with Shiila Infriccioli. 17 February, Bolzano.

Biasillo, R. and Armiero, M. 2018. “Seeing the Nation for the Trees: At the frontier of Italian nineteenth-century modernity”, Environment and History, 24(4), pp. 497-518. doi:10.3197/096734 018X15137949592025.

Bonan, G. 2016. “The Communities and the Comuni: The implementation of administrative reforms in the Fiemme Valley (Trentino, Italy) during the rst half of the 19th century”, International Journal of the Commons, 10(2), p. 589. doi:10.18352/ijc.741.

Cavada, I. 2022. Interview with Shiila Infriccioli. 14 February, Cavalese.

Cole, J. and Wolf, E. 1999. The

Hidden Frontier: Ecology and Ethnicity in an Alpine Valley. University of California Press. doi:10.1525/california/9780520216815.001.0001.

Dossi, T. 2021. “A Collective Agro-forestry-pastoral Economy in the Long Term: The case of the Magni cent Community of Fiemme’, OS. Opi cio della Storia, 2, pp. 34-43.

Ghosh, A. 2017. The Great Derangement: Climate change and the unthinkable. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press (The Randy L. and Melvin R. Berlin family lectures).

Ghosh, A. 2021. The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a planet in crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Giacomuzzi, P. 2022. Interview with Shiila Infriccioli. 15 Februry, Ziano di Fiemme.

Martellozzo, N. no date. “Condividere il Bosco, un Confronto Tra Regimi del Patrimonio in Val di Fiemme”, 2020, EtnoAntropologia, pp. 34-49.

Morandini, R. 1996. “A Modern Forest-dependent the Magni ca Comunità di Fiemme in Italy”, An International Journal of Forestry and Forest Industries, vol. 47.

Nixon, R. 2013. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. First Harvard University Press paperback edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press.

Nixon, R. 2013. “When Slow

Violence Sprints”. Available at: https://harvardpress.typepad. com/hup_publicity/2013/11/ when-slow-violence-sprintsrob-nixon.html.

Redazione, O. 2021. “Il Nord Est Minacciato dal Coleottero Bostrico: Già colpiti 7 mila ettari di foresta”, 25 November. Available at: https://www.open.online/2021/11/25/nord-est-coleottero-bostrico-foreste/.

Salis, A. 2012. The Expropriation of Collectivity for Private Interests. The Italian Debate around Commons and its Implications. Unpublished.

Tsing, A.L. 2021. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. New paperback printing. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Zanetti, E. 2022. Interview with Shiila Infriccioli. 18 February, Cavalese.