salvia spathacea

This guide concerns the horticultural, ecological, and scientific value of a handful of the plants in Arlington Garden. It also tells part of the story of these species from an earlier age — before global industrialization or, at any rate, before its effects had been fully felt. Some of this story is about evolutionary history: that part of the tale is very old! But some of the history is more recent and concerns human relationships with these species a mere hundred or thousand years out.

Why tell these stories, which are usually stories of loss? Humans tend to live in the present and the past fades; this is not so terrible — living is not easy — the problem is that we tend to treat the present as special. It has that special inertia that comes with being the status quo. One reason to tell the stories in this guide is to unmoor the present by adopting a very long or very wide point of view. Things weren’t always the way they are now. That future (our present) was open. The world changed radically. Our future is similar.

—AJ Jewell (2023)Arlington Garden is located on a layered landscape. We stand on the lands of the Gabrieleño Kizh Band of Mission Indians/Gabrielino Tongva, on what would have been a freeway, and on a community refuge for people, plants, and fauna. We invite you to care for this land and its history.

While you are here, you might find yourself relaxing under the Torrey pine. You might find yourself walking in the fragrant shade of a “Californian” pepper tree. Or you might find yourself sitting happily with some yarrow. One place where you will not find yourself is in the middle of the 710 freeway, which is remarkable, because a freeway is what this CalTrans land was destined to be.

This garden is the creation of community members who transformed a CalTrans staging site into an urban oasis. Arlington Garden is a 501 (c)(3) non-profit organization. We are a free community-forward, mediterranean-climate, habitat garden that uses regenerative gardening techniques. Caring for our local ecosystems and reconnecting people with their environment is our top priority! The majority of our revenue comes from individual donations, grants, and the sale of marmalade, which is produced from oranges grown in our citrus grove. Our revenue is supplemented with essential volunteering. Were it not for our dedicated volunteer community, this site might be another groaning, grayscale thoroughfare, instead of the kaleidoscopic microcosm it is!

Arlington prohibits visitors from collecting plants found in the garden without prior arrangement or permission. The garden’s 2.5 acres cannot support large-scale foraging, and — more importantly — munching on plants, even in a cultivated setting, can be hazardous to human health. Foraging should be done under the guidance of experts who know how to prepare plants for consumption and distinguish edible species from toxic doppelgangers. Even some edible plants, if prepared the wrong way, can cause life threatening illness. Although this guide discusses human uses of plants, it does not provide guidance of the right sort to eat them!

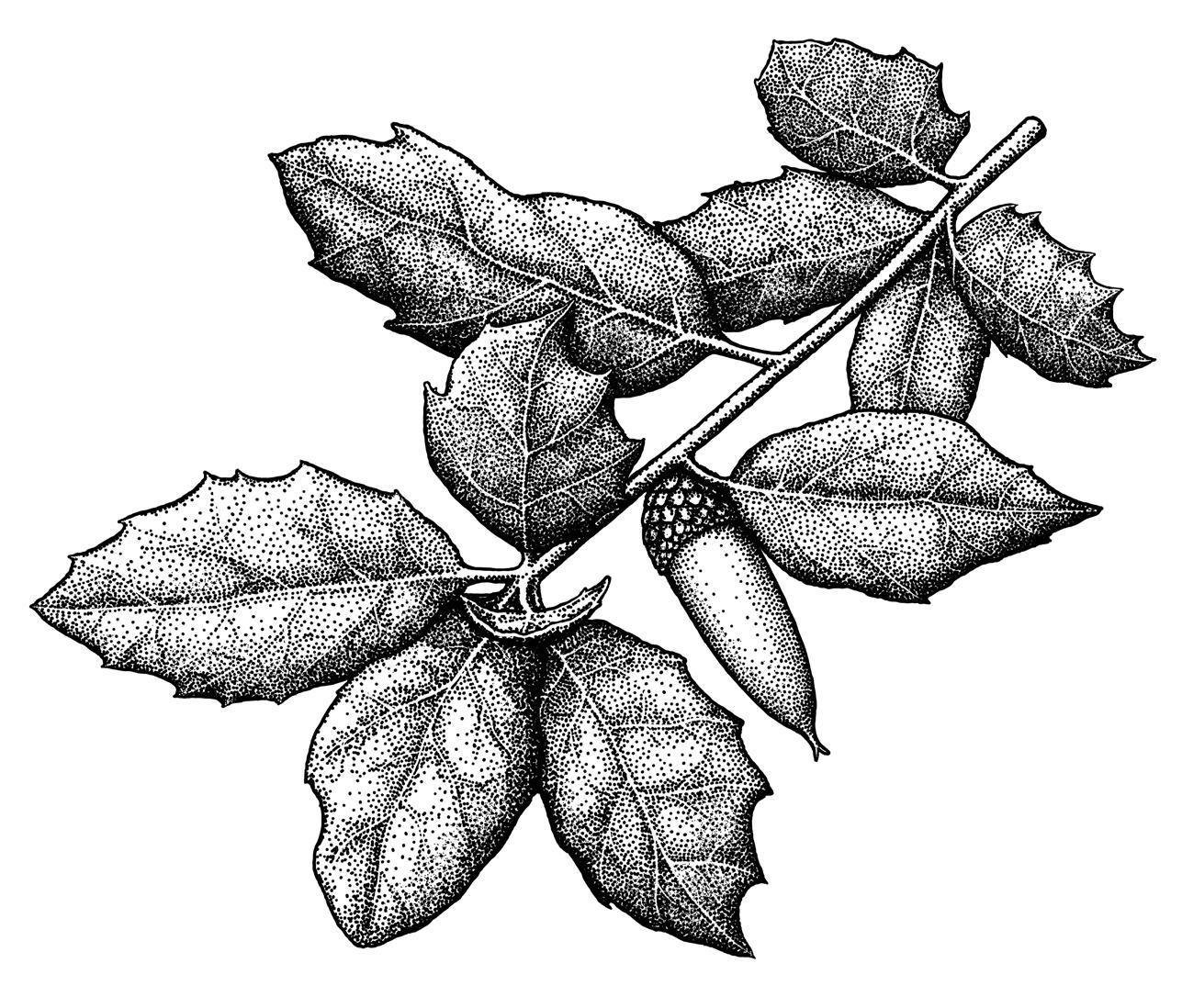

COAST LIVE OAK: Quercus agrifolia, encina/encino (Spanish), weť (Tongva)

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province, coastal regions up to Mendocino

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: trees often wider than tall: 30-60 ft. tall, 40-70 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: evergreen, cupped, holly-shaped leaves; develops multiple trunks with space and time; trees live for 250+ years with older specimens recorded; keystone species in oak woodlands and hence a beneficial habitat plant; avoid changing grade under the tree canopy.

100 YEARS OLD. It was one of 8 trees already on this site when the garden was founded in 2005, and it looks largely unchanged since that time. Of course, if you had been a rock or a mountainside during the tree’s early years, your mineral eyes would have seen branches fork across the sky and trunks explode upwards. Coast live oaks like this one undergo relatively rapid growth during maturation, growing up to 40 ft in a measly 20 years.

Older coast live oaks produce acorns in abundance, providing a dietary staple for Native American communities throughout California. These communities maximized production of acorns by using small, frequent fires to clear the brush under oaks, which made it easier to harvest acorns, keep other plants from encroaching, and prevent pests and diseases. Indigenous communities harnessed, and continue to harness, these small fires in sophisticated ways. Burning was timed to exploit weaknesses in the life cycle of detrimental insects: the filbertworm, Cydia latiferreana, is an acorn pest that spends part of its life pupating in the leaf-litter beneath oaks before remarkably transforming into an unremarkable-looking moth. Indigenous burning of undergrowth in the Fall killed filbertworms in their pupal stage, protecting the acorn harvest.

Beginning at the southern border and ending on the North Coast, the Spanish mission system in California followed the range of the coast live oak. This is probably not an accident, since the gnarled oaks — called “encinas” by the Spanish, using their name for the European holm oak Quercus ilex — frequently grow in deep soils along the coasts. Franciscan missionaries were aware that coast live oaks were indicators of arable soil, which was a requirement for their European agricultural practices.

As the friars crept up the coast, they encountered open woodlands and savannas dominated by gigantic oaks. In 1769, the Franciscan missionary Fray Juan Crespí described “large tablelands” with an open understory of “fine grasses” and “big tall liveoaks” — so big that he had never seen larger — around present-day Santa Barbara. These landscapes were the result of centuries of continuous care, incorporating frequent burning by the Indigenous people who lived there: Fray Juan Crespi was praising the work of the Chumash, intentionally or not, when he marveled at the great trees. The missions needed farmland. They also sought Indigenous people to work, very often against their will, to convert, and to indoctrinate. Terrible and ironic as it may be, the presence of a coast live oak savanna, with a “parklike” understory and ample acorn harvest, would have been an indicator of both farmland and an Indigenous community to convert.

cont. p.36 »

SYCAMORE TREES ARE APPARITIONS of riparian and seasonally wet habitats across Central and Southern California extending into Mexico. The white and grey trunks of mature specimens can reach several yards in circumference, growing at odd angles from the ground with branches bent and leaves muttering in the wind. The local El Cajon author and postal worker W.S. Head fancifully but correctly called this species “the Queen of the elfin forest” and cites “someone” as calling it “the ghost that stands with its feet in the water.”

Arlington’s western sycamores grow towards the bottom of the slope running the length of the garden. When it rains, this section of the garden becomes a temporary wetland: ideal habitat for this species.

Some of the water in this seasonally flooded area is absorbed by plants; some of it evaporates; a bit may trickle deep down into the aquifer. The rest of the water ends up in the Los Angeles River drainage basin, which is just to say that we are in the Los Angeles River watershed. The garden borders the Arroyo Seco Watershed to the west, itself a part of the larger Los Angeles Watershed, once home to many western sycamores.

The Arroyo Seco is the prominent

river of the Pasadena area. Although it contains relatively little water for much of the year, for millennia it has been the site of cataclysmic floods carrying sediment and uprooted forests down the mountains. The flood of 1861, for example, was described 29 years later in biblical terms: it was as if “the windows of heaven were opened, and the waters prevailed exceedingly on the face of the earth.” According to reports, the effects of the flood were multiplied by a raft of “driftwood,” no doubt containing many sycamores, pulled down the arroyo, forming small dams that channeled floodwater toand-fro. In another large flood five decades later, 43 people lost their lives. In response, large portions of the river below Devil’s Gate Gorge were straightjacketed in concrete.

Western sycamores require large flood events to reproduce in quantity, since flooding deposits the clean silt, cobble, and gravel conducive to seed germination. Likely because the Arroyo floods are now gone with the channelization complete, the sycamore forest surrounding the river is much reduced.

Observe the thin dappled bark and twisted boughs of Planatus racemosa trees in the garden. Touch the trunk. Can you feel the slightly raised edge between the lighter patches of bark and the darker patches? The outer bark does not expand at the same rate as the interior bark, so the outside layer sloughs off, forming a mottled pattern. This distinctive pattern, combined with the trees’ angled branches and trunks, suggests that sycamores have some sort of attrac-

tive illness. Mostly, they aren’t sick: nonetheless, the impression is a good mnemonic device, since “sycamore” is pronounced “sick-amore.”

For reasons unknown to the author of this guide, the Spanish word “aliso,” which means “alder,” is used to refer to western sycamores. The most famous aliso probably ever was called “El Aliso”— “The Sycamore”— its name a bit literal in one sense and confusing in the other, since “aliso” means alder, but the definite article showing, at any rate, that it was peerless, the only real Aliso in a vast countryside of mere alisos.

El Aliso once stood in Yangna (or Yaangna), an Native American village once located where the present-day 101 freeway runs through downtown Los Angeles. The tree was enormous. It stood over 60 feet tall. Its trunk cont. p.37 »

WESTERN SYCAMORE: Platanus racemosa, aliso (Spanish), sā-vār or shă-var’ (Tongva)

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province, riparian areas near the coast and some inland areas

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 40-80 ft. tall, 30-50 ft. wide.

GARDENING NOTES: winter deciduous; thrives with significant amounts of water in well-draining soils; best planted near swales, streams, or seeps; otherwise supplemental moisture is required; drops large leaves on anything planted underneath.

IN EARLY SUMMER, before the dry heat hits and the broiling sidewalks become truly empty, you will see the intricate shuttlecock-shaped blooms of this species. Look for extravagant umbels of pink-and-white flowers at the terminus of tall slender stems.

You may also see, if the timing is right, a lot of colorful living things clinging, crawling, eating, mating, killing, and fluttering about on these plants. Inspect the stems, particularly right below the umbels of white-pink flowers: you might find clusters of bright yellow aphids with thin black legs. These are oleander aphids, Aphis nerii, herbivores originally from the Mediterranean and, since gone global or “cosmopolitan” — now flamboyant citizens of the world.

NARROWLEAF MILKWEED: Asclepias fascicularis, to-hah’-ce-aŕ (Tongva)

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province, throughout California except high mountain ranges

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 1.7 ft. to over 3 ft., individual plants 1 ft wide, forming colonies

GARDENING NOTES: winter deciduous; blooms in the summer at Arlington; do not use any pesticides because it is a food source for many insects including monarch butterfly caterpillars; all parts of this plant are toxic when consumed, but A. fascicularis poses special risks to horses.

Oleander aphids reproduce in the wild almost entirely through parthenogenesis, which is reproduction via unfertilized eggs. The process of parthenogenesis doesn’t require males. Hence, in the wild, there are at most very few males: in fact, only a few naturally occurring males of the species had ever been observed as of 1993, although they have been shown to exist in potentia in the laboratory.

Along with aphids, you may observe a number of other gaudy citizens of the early 21st Century milkweed civilization. The small milkweed bug, for instance, is a black and reddish-orange true bug that eats milkweed seeds. The western milkweed longhorn is a similar-looking beetle whose red carapace is decorated with black dots. You can distinguish the latter from small milkweed bugs by the patterns on its back: milkweed bugs have aggressive crossed bars, and milkweed longhorns have stylish spots! True bugs such as small milkweed bugs also always have a sharp beak, which they use to pierce plants or prey and suck out their insides.

If you are very lucky, you will also spot a caterpillar of the monarch butterfly. Much has been written about this species, so this guide won’t expand on the subject. Suffice it to say that striped monarch caterpillars, like the insects mentioned above, are brightly colored as a form of deterrence. Their costumes signal to predators that they are this kind of insect, a kind of insect (hopefully the predator remembers) that is very, very unpleasant to eat. And they are unpleasant, because their bodies are laced with toxic compounds from their food, Asclepias fascicularis.

These brightly colored warnings also apply to humans for different reasons: please do not touch!

HUMMINGBIRD SAGE is a shade-loving groundcover with whorls of flowers so colorful that the illustrator of this guide has remarked they look like showy garden cultivars — escapees from secret underground labs at the Royal Horticultural Society. They are, however, native to California’s oak woodlands and chaparral. If you are at the garden in the winter and spring, the flowers and leaves will be visible. Otherwise, you may need to hunt a bit to discover the sprawling stalks. If in doubt about identity, squeeze a quilted leaf and check for a “fruity” cheerful odor.

The flowers of hummingbird sage form a whorl (a ring) around the peduncle (the main stem) of the plant’s flower spike. The reddish-to-purple

HUMMINGBIRD SAGE: Salvia spathacea, diosita (Spanish), qimsh or pakh (Chumash)

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province, southern California up to Solano County near Sacramento

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: slowly spreading rhizomatous groundcover 1-3 ft. tall

GARDENING NOTES: grows well in dry shade under oaks; unusual purple-red flowers attract hummingbirds; appropriate for pot culture; a perfect landscaping plant in Pasadena.

scale structures the flowers grow out of are not petals, but modified leaves called “bracts.”

These flowers evolved in tandem with bird pollination, which has the occult-sounding name “ornithophilous” or bird-loving. Nectar is stored deep inside the tubular flower while the flower’s pollen-bearing stamens extend past its lip (see them poking out in the illustration). In fact, the nectar and stamens are separated just enough that foraging hummingbirds, sipping nectar, dunk their heads in pollen. Some biologists hypothesize that these are fine-tuned adaptations specific to bird pollinators, since pollen is less likely to fall off birds’ feathers than their smooth beaks, and thus more likely to make it to the next flower.

Look around you. Hummingbird sages grow in dry, open understories of coastal oak and mixed woodlands. These dappled worlds are surprisingly dense with plant, animal, and fungi species. Take just the animals: oaks provide shelter, food, or are indirectly “associated” (e.g. as hosts for prey species) with thousands of animal species including woodrats and mule deer, owls, skinks, arboreal salamanders — they climb trees — and many crawling and gnawing nameless things.

Oaks are also the main engine of so-called “nutrient cycling” in their kingdoms. They add carbon and other nutrients to the forest floor via leaf litter. And they use their extensive roots to capture the nutrients again (aka “cycling”) before they wash away.

THIS FLOWERING SHRUB SUPPORTS A COLOSSAL number of animals as shelter, farm, and pantry. It blooms for a long period in the late spring and summer with dry umbels darkening to rust-coloured poms, adding texture to hillsides. California buckwheat is a caterpillar host plant for Plebejus butterflies like the modern-looking Acmon blue plebejus, which wears the subtle colors of an expensive scarf, as well as many others.

California buckwheat is a keystone species. It holds up the arches of some quintessential California plant communities including coastal sage scrub. Keystone species are important enough to an ecosystem that their removal would be highly disruptive to species diversity and abundance. Remove a keystone and the arch comes crashing down — that’s the metaphor.

California buckwheat is a plant, but the keystone concept was first introduced to describe animal predators by Robert Paine, a biologist who studied the small and hardy things living in tidepools. Although he worked with small creatures, Paine was a large man, reportedly 6’6”, and, in photos, he glows with a ruddy countenance and happy demeanor, with extra-large waders pulled up to his chest.

In “Food Web Complexity and Species Diversity,” he describes an experiment establishing that the predatory starfish Pisaster ochraceus is a keystone species. Pisaster is a purple and orange starfish from the

Washington coast that eats barnacles, mussels, chitons, and other molluscs in the tidal zone. In the experiment, Paine compared two sets of tidepools, one in which he had removed the starfish — by literally tearing them from the rocks and throwing them out to sea — and another which he left undisturbed. The species composition of the undisturbed tidepools remained unchanged during the experiment. But the tidepools without starfish were quickly altered and for the worse : within a year, a species of mussel had almost completely dominated the area, pushing out other molluscs and decreasing the total number of species in the local food web from 15 to 8 — a decrease in local species richness of nearly half!

This experiment showed Paine that, although the starfish doesn’t care a whit about it, Pisaster ochraceus is a biodiversity promoter and hence a keystone species: it keeps mussels and barnacles, both of which are effective at dominating the real estate of this liminal habitat, at levels low enough for other species to compete.

CALIFORNIA BUCKWHEAT: Eriogonum fasciculatum, valeriana (Spanish), jm’ilh (Kumeyaay), tswana’atl ‘ishup (Chumash), wilakal (Tongva)

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province and other parts of the Southwestern United States and Northern Baja into the Great Basin, found in chaparral and coastal sage scrub

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 2-6 ft. high, 2-3 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: makes a long-lasting cut flower; provides year-round interest in mediterranean gardens due to its summer blooms and beautiful seed clusters; ideal for habitat gardens in Southern California where it is ubiquitous on nearby mountain slopes and hillsides.

PODS dangling from the tips of criss-crossed stems help identify this striking shrub. In addition to the pods, you can recognize it by its yellow firework flowers and pungent odor. Bladderpod supplies food to a great many pollinators including hummingbirds, and it can produce blooms in summer when other California natives enter dormancy.

Bladderpod, with the sobriquet “stinkweed,’’ produces a distinctive odor when its leaves are damaged. The Los Angeles native plant organization, Theodore Payne Foundation, describes it as “smelling like bell peppers,” but others say it smells similar to burnt tires. (Bell peppers are, in any case, divisive.) One present

BLADDERPOD: Peritoma arborea (Cleomella arborea), ejotillo (Spanish), peshaash (Kumeyaay)

ORIGIN: southern California Floristic Province down into Baja California

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 1.5-6 ft. high, up to 6 ft. wide, although seldom this large in gardens

GARDENING NOTES: flowers for a long period, reblooming throughout the year with extra water; bright yellow flowers; regarded by some as one of the easiest Southern California natives to grow; an excellent choice for habitat gardens.

staff member at Arlington finds the odor repugnant, but the author of this guide would describe it merely as “savory.” The source of the smell are compounds (glucosinolates) that the plant likely produces to defend against insect pests and other enemies such as fungi. These compounds are also produced by members of the mustard family, such as collard and brussel sprouts, to which bladderpod is related. Pinch a leaf to smell it for yourself!

The flowers of bladderpods are eaten by the Kumeyaay, who are the Indigenous people of southernmost California and northern Baja California. The anthropologist Michael Wilken-Robertson reports that the Kumeyaay eat the flowers and buds by “nipping them off with thumb and forefinger” before a long boiling process during which the bitter water is replaced several times. The cooked flowers are rolled into a ball and can be eaten plain or with a tortilla.

Bladderpod is an endurer. Granted, this doesn’t distinguish it from other perennials that also live through less-than-ideal conditions. What sets it apart from lavender (a doughty barbarian compared to a cultivated rose) or vain hibiscus are the conditions that it’s adapted to endure: extreme environments in which water is absent and heat and sunlight present a constant threat. As an adaptation, it has developed a waxy, pale leaf and stem, which reduce evaporation and cont. p.38 »

THE HEAVIEST CONES of any pine species, with some sources reporting specimens weighing a staggering 10 pounds and measuring 7-13 inches long. The cones have prominent talons on their “umbos,” the adorable name for the ominously pointed tip of the cone scales. Along with the name “big-cone pine,” the species is called the much more exciting “widowmaker,” presumably because of husbands felled by monster cones. Evidence of the trees’ grim reputation crops up in unexpected places. In the dry reference tome Flora of North America, a paragraph of botanical information is followed by this incongruous aphorism: “One who seeks its shade should wear a hardhat.”

freeway. Around 5-7 million years ago, in Los Angeles County, the pressure instead uplifted massive blocks of ancient granite and even more ancient Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rock. This Precambrian rock is, at youngest, 544 million years old, which makes the bones of the San Gabriel Mountains older than animals with spines.

As the mountains rose, the wind and rain tried to beat them down, without success. As a result, large amounts of mineral earth in the Los Angeles basin was birthed from these mountains. Despite the erosion (around .5 mm a year above Los Angeles), the mountains remain a steep climb.

You can find Pinus coulteri in the San Gabriel Mountains north of Pasadena, where it joins with other conifers in fragrant bands wrapped around elevations up to 2100 meters. The San Gabriel Mountains are part of the Transverse Ranges, which are a confluence of smaller mountain ranges flowing east from the sea, eventually petering out in the dry deserts. They were created when a piece of the Earth’s crust rotated 90 degrees, distorted by the enormous, shearing energy of the Pacific tectonic plate scraping along the edge of North America. Activity at the edge of the North American plate elsewhere created volcanos — the Cascades that truckers pass along stretches of the 5

COULTER PINE: Pinus coulteri, big cone pine, widowmaker

ORIGIN: Coastal mountains in southern California Floristic Province extending up to San Francisco

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 30-80 ft. high, trunk up to 3 ft. wide, canopy to 40 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: for larger yards or parks; grows in dry rocky soil in the mountains near the coast but away from the ocean.

WERE FORGED in the astonishing species-factory of the western Cape of South Africa. They form an important part of fynbos — a woody shrub community similar to chaparral. Arlington features several species of this genus including Leucadendron discolor (also called “Piketberg conebush” and “rooi-tolbos” in Afrikaans) and cultivars such as “Jester” and “Safari Sunset.”

Arlington Garden is a mediterranean climate garden with mild, wet winters and warm, dry summers. There are 5 mediterranean climate regions on the planet: California and parts of Baja California (together called the “California Floristic Province”), the Mediterranean Basin, the western Cape of South Africa, parts of southern Australia, and central Chile. In all of these regions except, historically, central Chile (which had few naturally-occurring fires), wet winters create growth, which burns over the dry period.

CONEBUSH SPECIES: Leucadendron sp. (“Safari Sunset” is pictured)

ORIGIN: Cape Floristic Province, South Africa

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: ranging in height and size, Leucadendron discolor is 6+ ft. tall and 5 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: requirements differ across species but Leucadendron discolor and many others require a full sun exposure with well-draining soil and limited summer water; many species of Leucadendron are susceptible to fungal disease when their roots are kept too wet or disturbed, hence, care should be taken when placing irrigation systems and weeding or planting in the root zone.

It is a general rule that an ecosystem’s biodiversity decreases the farther it is from the equator. All mediterranean climate regions are exceptions to this rule, however, because they are very biodiverse and far away from the lush, equatorial centre. Such regions cover approximately 2.2% of the globe yet are home to roughly 17% of all plant species. South Africa’s Cape Floristic Province has a particularly outsized impact on global plant diversity: although it is less than ⅓ the size of the California Floristic Province, it hosts twice the number of plant species with 70% found only there!

Why do these fluctuating, dusty spots along the edge of continents have such a rich diversity of species? Robert Cowling, Philip Rundel, and others have argued that there is no single explanation. In South Africa and Australia, historically stable geological and climatic conditions reduced extinctions, contributing to diversity. Such places are sometimes called “museums.” In California and the

Mediterranean Basin, the existence of many geological, climate, and soil types also contributed to diversity.

A 2018 paper by Philip Rundel and others argues that predictable, frequent fires are a contributing factor to species richness in all mediterranean regions except central Chile. Over blind stretches of evolutionary time, some plant families in these regions diversified to create new, more fire-adapted lineages. These lineages evolved to store more water in their limbs and trunks, thicken bark, and resprout and germinate in response to heat and smoke.

In fynbos, the cyclic churn caused by fire may also allow for the coexistence of similar species with no group able to dominate before the ecosystem burns again. Fire creates predictable flux, and flux can lead to diversity.

Some fire-adapted species, such as coast live oak in California, survive fires. Survivors have thick bark that resists flames or resprout from burls or roots. Leucadendron discolor on the other hand, is a strategic perisher. This conebush dies in fire, but it has evolved a cone that survives and opens in response to the blaze (the term for this is “serotiny”). Following fire, the cone reseeds without competition from adult plants.

A PALE FOG OF A PLANT in the sunflower family (Asteraceae), this species has fine, frond-like leaves that spill out like rolling clouds. Despite its foliage, this plant tends to fade into the background in its coastal sage scrub environment. In garden settings, it attracts more attention. Like many Artemisia species, it has an attractive, powerful scent when its leaves are crushed. Fire adapted, it is a survivor. After burning, it resprouts from its root crown around 25% of the time and produces seed. In parts of its range, California sagebrush is a habitat plant for the Coastal California Gnatcatcher, which is a federally recognized endangered species. Dusky-footed and desert woodrats also use California sagebrush as a food source.

California sagebrush is an iconic plant in coastal sage scrub ecosystems. Humans traveling through these ecosystems usually discover its intoxicating scent. A hiker who brushes up against sagebrush adds one note to the heady aroma; trodding on black or purple sage adds another. Beware, if you are out hiking, that the perfume doesn’t lure you into stands of poison oak!

Coast sage scrub is often called “soft chaparral.” Chaparral is the characteristic vegetation of the California

Floristic Province. If you’ve seen the hillsides of the nearby San Gabriel Mountains, then you know what it looks like, since it is the dominant type in this and many other areas around Los Angeles County.

Chaparral is composed of many woody shrubs with tightly-clustered, evergreen leaves in standardized “mediterranean” hues. The leaves are often hard and waxy. Coastal sage scrub, on the other hand, tends to have more soft-leaved species than chaparral. Its shrubs are somewhat smaller, and (unlike chaparral plants) they tend to lose their foliage over the dry summers.

CALIFORNIA SAGEBRUSH: Artemisia californica, romerillo (Spanish), powats (Tongva)

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province coastal regions from San Francisco to Baja California

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 3-5 ft. tall and 5-7 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: fast growing, shallow-rooted shrub with extremely low water requirements; many cultivars are available in a variety of sizes and shapes; good selection for a habitat garden; can be kept trimmed for shape; leaves should be harvested right after new growth, following rain.

THE ANCIENT PHILOSOPHER Zeno sought to show that motion is impossible, because any movement through space can be divided into infinite sub-parts, each of which would take some amount of time to traverse. This so-called “paradox of motion” is that if you could move, you would never arrive! So, Zeno concluded, movement is an illusion. Manzanitas can look paradoxical in this way: their branches ramify and divide seemingly infinitely before arriving — through illusion — at large, smooth leaves. In reality, the species’ ramified branching is created simply by flowering: when a manzanita flowers at the tip of a branch, that branch terminates and new growth splits out behind the flower cluster. After years of repeated flowering and splitting, the mature plant becomes a cage of complex branches.

Most manzanita species, like the flammable whiteleaf manzanita, have shallow roots and thin bark and die even in low-intensity fires. Similar to conebushes in South Africa, manzanitas require fire to germinate, so flammability may confer an evolutionary advantage. Arctostaphylos glandulosa (Eastwood’s manzanita), on the other hand, resprouts following fire from burls, which are woody, thickened roots that protect dormant leaf buds from flames.

The name manzanita means “little apple” in Spanish, and the fruits — their scientific name is “drupes” — look like miniature manzanas (apples). The drupes of certain manzanita species are used by the Kumeyaay, the Indigenous people from around San Diego, to make a drink sweetened with sugar or honey. Soaking the fruits prior to grinding makes it easier to remove the seeds.

Bears and coyotes also consume the fruits of this genus, the origin of the name “Arctostaphylos,” which is a compound of two Greek words

meaning bear (“arktos”) and grapes (“staphylos”).

A plant that is exclusively native to an area or growing conditions is called “endemic” to that area or conditions. San Gabriel manzanita (a subspecies of Arctostaphylos glandulosa) is a native and endemic plant in Southern California. Western sycamore, in contrast, is native but not locally endemic, since it is not restricted to Southern California.

Many manzanita species and subspecies are endemic to little zones within the mutable terrain of California: they can so dominate their tiny, infertile kingdoms that these areas are called “manzanita barrens.” Despite their hyper-local abundance, approximately 50% of manzanitas are rare or uncommon in California.

MANZANITA SPECIES: Arctostaphylos sp., soo-boó-chech or sobochesh (a Tongva general term for manzanitas)

ORIGIN: most species are from the California Floristic Province.

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: species and cultivars range in height from tall shrubs up to several meters to low-growing groundcovers.

GARDENING NOTES: there are 40+ California manzanita species adapted to a variety of conditions, with the California Native Plant society recognizing 117 native species and subspecies as of 2023.

THREE GRASS-LIKE SPECIES: Muhlenbergia rigens (deer grass) (“su-ul” in Tongva), Elymus condensatus “Canyon Prince” (Canyon Prince wild rye) (“carrizo” in Spanish), Juncus acutus (spiny rush) (“psilj” in Kumeyaay)

ORIGIN: deer grass: southwestern US and Mexico growing north up to Redding in the California Floristic Province; Canyon Prince: western North America to the Great Lakes south into Mexico; spiny rush: native to western North America and scattered temperate and subtropical regions throughout the world.

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: deer grass: up to 5 ft. tall and 3-6 ft. wide; Canyon Prince: up to 5 ft. tall and spreading; spiny rush: 3-6 ft. tall and colony forming

GARDENING NOTES: all of these species perform best in full sun; they can also all be cut back periodically in order to maintain their shape and color; as its name does not suggest, deer mostly avoid deer grass in garden settings; rushes do best with riparian areas with plenty of water.

SHAPERS OF OUR SEASONAL WETLAND AREA, these “grasslike” species provide cover underneath trees and riparian shrubs. Although all three look like grasses, only deer grass and Canyon Prince wild rye are scientifically grasses. Spiny rush is, unsurprisingly, a rush. Although some grasses can be pests in the garden and surrounding ecosystems, these plants spread slowly and present no threats to garden integrity at Arlington.

Grasses, rushes, and the very similar looking sedges are each in a different plant family — we won’t go into the taxonomic details here — and their similarity can give gardeners headaches. They can be distinguished through close inspection and use of this rhyme:

Sedges have edges,

Rushes are round, Grasses have nodes from the top to the ground. The visible parts of grasses include stems, leaves, and often a flower spike. However, we tend to think of them as only leaves, possibly because it is so difficult to identify the mangled parts in a mowed lawn.

Grass stems are generally hollow with solid joints (“nodes”) where the leaves attach. You can feel the nodes by gently running your hand along the stalk. Rushes have dense, round stems with leaves wrapped around; they do not have nodes. They are usually hard and smooth to the touch, although there are exceptions. Sedges,

on the other hand, usually have solid, triangular stems. When feeling along the stalk, see if you can detect the vertex of a triangle — that’s probably a sedge!

Gardeners have an interest in distinguishing these plants because they have different growing requirements. And it’s always useful to be able to distinguish invasive terrors like Bermuda grass — an unwanted and vigorous “guest” in Southern California — from bunch grasses or sedges.

The Kumeyaay and other Native Californians use spiny rush, along with basket rush (Juncus textilis), to weave functional and beautiful baskets. Spiny rush is first harvested by coppicing — cutting the plant to just above the ground — which promotes the growth of tall, straight shoots. These shoots are split and bundled together to form a foundation layer, around which stems of the more flexible basket rush are stitched in a spiral. Baskets made by the Kumeyaay using these traditional techniques are widely admired and the craft has experienced a recent revival.

SCATTERED THROUGHOUT the garden, this large native buckwheat grows well in our hot summer climate even though it is native to the cool Channel Islands. Its felted leaves are much larger than those of other native Eriogonum species.

As you might have inferred from the name “Eriogonum giganteum,” it grows to gigantic stature in the right conditions. Its flowers are held in umbels, which are umbrella-shaped flower heads with many white flowers arranged in a flat circle. These umbels look a bit like a Catherine’s Wheel, a circular spinning firework named for St. Catherine of Alexandria, although the resemblance may be coincidence.

St. Catherine’s lace and other members of the native buckwheat genus Eriogonum are not closely related to “common buckwheat,” the source of the buckwheat flour you’ve eaten in baked goods or noodles. That flour is made using a cousin species (Fagopyrum esculentum) from Asia. There are nonetheless many Eriogonum species that are consumed by humans. Some Kumeyaay people use the roots of California buckwheat, for example, in a tea to treat stomach and heart ailments.

ST. CATHERINE’S LACE: Eriogonum giganteum

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province, an iconic plant of the Channel Islands

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 8-10 ft. tall and 8-10 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: appropriate for a focal-point planting; easy to grow in Pasadena and self-propagates at the garden; despite being vigorous and prone to volunteerism, it isn’t invasive here; plants with umbels like this one and Eriogonum fasciculatum make excellent habitat garden plants, since they attract a wide variety of insect pollinators; full sun, low-water needs.

OLIVE TREES ARE A FAMILIAR SIGHT in the Mediterranean Basin and throughout Southern California where they are common components of residential landscaping and restaurant decor. The trunks of older specimens look like taffy twisted up into curtains of gray-green foliage. Fruiting trees produce olives and also a gooey mess of fruits beneath their canopy. The cultivar we grow in the olive allée — “Wilsonii” — is a “fruitless” olive and is popular in landscapes where gardeners do not want a mess.

The author imagines that the sky was very blue and the wind was very fierce that day, since it was near the beginning of the world and nothing had faded. Poseidon struck the earth with his trident, marking the stone, and birthing a horse and saltwater well. The people of the city marveled because the gift of horses (represented by that single horse) was a great gift. Athena stepped forward and stretched her spear to the ground. No mark was left in the stone. Yet from that spot grew an “olive-tree with pale trunk, thick with fruit” writes Ovid in Metamorphoses, which left “the gods marveling.”

According to old tales of the Mediterranean Basin, the ocean god Poseidon and the parthenogenetic goddess of knowledge Athena once competed to be the patron of a famous city in Greece. In some tellings of this story, each god offered the city a token.

According to legend, the paletrunked tree was the first olive tree or at least the first domesticated one. What Athena offered the city was a source of oil and nutrient rich fruits: the foundation of the Mediterranean diet and a valuable trade commodity. As the inventor of early tree agriculture, Athena was crowned the victor, and the city of Athens became her namesake. The location of the olive tree became the site of an acropolis: a small city of temples set above the human city.

The tree was said to still be alive in the 5th century BCE by the ancient historian and travel-writer Herodotus, who writes:

In that acropolis is a shrine of Erechtheus, called the “Earthborn,” and in the shrine are an olive tree and a pool of salt water. The story among the Athenians is that they were set there by Poseidon and Athena as tokens when they contended for the land. It happened that the olive tree was burnt by the barbarians with the rest of the sacred precinct, but on the day after its burning, when the Athenians ordered by the king to sacrifice went up to the sacred precinct, they saw a shoot of about a cubit’s length sprung from the stump... (Herodotus, Histories, 8.55)

Popular travel websites attest that there is still an olive tree in the Acropolis today, and — in particular — a tree still growing next to the temple of Erechtheus. Some say that this tree is a clone of the original gift from Athena. According to this tale, over the centuries, as the tree was damaged or grew feeble, a branch or cutting was always saved and rerooted. This preserved the genetic line through a sequence of clones, each tree dying, but the gift living on.

The trees in the olive allee are a so-called “fruitless” variety of Olea europaea , but they are not entirely barren. If you are in the garden in the Fall, you will find a few olives amongst the branches.

Although it does produce occasional fruits, horticultural inventions (cultivars) like “Wilsonii’’ are usually not propagated by seed. Non-hybrid cultivars are usually created when a grower identifies a desirable genetic mutation — in this case, extremely reduced fruit production — and preserves the mutation by cutting off branches or shoots from the original plant. The cuttings are then rooted or grafted onto another plant, which effectively clones the original.

The resulting plants eventually mature into normal-looking trees that contain the same genetic material as the original. Eventually, in turn, they are propagated by the same “low-tech” cloning techniques—similar, in fact, to the legendary tree of Athena and even to parthenogenetic Athena herself, who, like all offspring of parthenogenesis, is partly a clone of her parent Zeus.

FRUITLESS OLIVE: Olea europaea

‘Wilsonii’, ἐλαία (Greek), shajarat zaytun شجرة زيتون (Arabic)

ORIGIN: Mediterranean Basin

Mature height and width: 25-35 ft. tall with canopy up to 30 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: this iconic and lovely tree requires supplemental water when young; although olives are listed as an invasive species by the California Invasive Plant Council, they are not likely to be eradicated from our landscapes given their important role in agriculture; nonetheless, homeowners should take care that their landscape olives do not have easy access to surrounding ecosystems.

pepper tree is one of 8 trees that were on this site when the garden broke ground in 2005. The common name is a misnomer, since the species is endemic to Peru and parts of Chile.

Schinus molle trees produce pink fruit “peppercorns” that are eaten by humans and birds—but be cautious! The tree is a member of the cashew family and presents a potential danger to people with nut allergies. In fact, there was a widely-publicized dust-up between the FDA and France about the health effects of pink peppercorns in the 1980s.

Authorities continue to disagree about the risks associated with eating the fruits even for non-allergic people: an official Queensland Australia government website lists them as toxic to humans as of the publication of this guide (2023) and others continue to caution about dangers specifically to children, pigs, and poultry. That said, they continue to be widely sold and eaten in the United States, and they have been fermented and consumed in Peru for over a thousand years.

This tree was once part of the gardens of the strange and fabulous Durand House, a 50-room mansion home to John Durand, a wealthy wholesaler from Chicago. The mansion was designed in the style of a baronial French chateau and included intricate wood carvings, a red sandstone exterior, and gardens with high-maintenance plantings: roses, orange trees, and palms.

It was so extravagant that the Los Angeles Times heralded it as “the most peculiar and at the same time the most lavishly finished residence not only in Southern California but in the whole country.” It was peculiar both for its sheer extravagance — the interior “locks, hinges, doorknobs, drawer handles, etc.” were made of expensive gold alloy — but also for such strange amenities as a light switch next to Mrs. Durand’s bed that turned on “every light in the house from cellar to roof,” more than 600 lights, apparently as a form of burglar deterrence.

The Durand property and its furnishings were sold at auction in the 1960s and then razed to the ground. The only traces left of the mansion are a small walkway and a fragment

of the original sandstone facade built into Arlington’s Pomegranate Amphitheater.

Caltrans later set aside the property as a staging ground for the 710 freeway expansion, but local opposition to the freeway halted construction. The lot remained empty for 40 years until the creation of the garden in 2005 by a group of dedicated Pasadena residents. In the decades since, the original trees — such as this California pepper tree — have ended up in the middle of a swiftly growing forest. What do they think of the new arrivals?

The Wari (Huari) empire in the Andes flourished between 650 to 1000 CE and was an agricultural civilization predating the Inca. Archeological evidence shows that “elites” among the Wari drank copious amounts of alcohol made from Schinus molle berries. This alcohol was probably similar to a beverage that Spanish later called chicha, which continues to be made from ingredients including corn and quinoa and — now very infrequently — Schinus molle. The Spanish Jesuit cont. p.38 »

CALIFORNIA PEPPER TREE: Schinus molle, Peruvian pepper tree, molle del Peru (Spanish), mulli (Quechua)

ORIGIN: Peruvian Andes, central Chile, and parts of Argentina

Mature height and width: 35-45 ft. tall and 50-75 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: an evergreen tree often wider than tall with drooping branches; female trees have panicles of pink fruits (peppercorns); classified as invasive by the California Invasive Plant Council, Arlington does not recommend planting new specimens of this species.

CRAPE MYRTLE HAS A STRANGE, SMOOTH TRUNK AND BLOSSOMS that last for a long time over the summer. All members of the genus Lagerstroemia are called “crape myrtles” in the United States, but the most common species are Lagerstroemia indica, Lagerstroemia fauriei, and their mutual hybrid.

The genus is not native to North America; it originates in Asia and parts of Oceania. Crape myrtles were first introduced in the 18th century in South Carolina at the vast gardens of the botanist André Michaux. Over the next 200 years, they increased in popularity as landscape plants in the American South, with some cities becoming synonymous with the plants, such as Paris, Texas, which still crowns an annual Crape Myrtle Queen.

Among other bloody tales about the crape myrtle, there is this one: According to a Korean folktale, there was once a serpent (imugi) who threatened a city by the sea. To protect themselves, or out of custom, the people of the city offered up young women as sacrifices to the monster. One year, it happened that the chosen woman inspired the pity of a young man. In order to save her, he set out on a boat to kill the imugi, telling her that if he succeeded, he would fly a white flag from the ship when it returned. If he failed, the flag would be red.

The young man sailed over the horizon, and 100 days passed. Each day, the woman walked down to the shore to look for his ship. On the 100th day, she saw it come over the horizon. As it drew closer, she perceived that its flag was red, and in a fit

of terrible despair she took her own life. The ship arrived back at the city. The young man disembarked only to learn of the woman’s suicide. Distraught, he saw at once that the white flag on his ship had been stained with the dead serpent’s blood. After the woman was memorialized, her tomb sprouted strange red flowers that bloomed for 100 days. According to the tale, they are the source of the name “baegilhong,” which means “red for a hundred days.”

Our crape myrtles were once part of the artist Yoko Ono’s (2008) “Wish Tree for Pasadena” project at One Colorado in Pasadena. Over the three-month duration of the project, visitors attached more than 80,000 wishes to 21 trees.

Ono was inspired by wishes she had seen tied to trees in Japanese temple courtyards. In Japan, such wishes are a traditional part of Tanabata festival held on July 7th. For the festival, wishes are written on slips of paper called “tanzaku” and attached to bamboo “trees” in honor of the celestial lovers Orihime, the weaver princess, and Hikoboshi, the oxherd. According to the tale, the King of Heaven separated the lovers with the Milky Way, the “Heavenly River,” and allowed them to meet only on the Seventh Day of the Seventh Month. An ancient poem in the Manyoshu describes this reunion:

To-night he makes his one journey of the year

Over the Heavenly River, passing Yasu Beach —

He, the love-lorn Oxherd longing for his maid,

Whom he can never see but once a year, Though from the beginning of heaven and earth

They have stood face to face across the Heavenly River.

After Tanabata, it was once the custom in some places to place the tanzaku wishes in an earthly river to wash away. At the end of Ono’s project, the wishes were collected — removing them reportedly took over a week — and buried at the Imagine Peace Tower off the coast of Iceland.

Following the exhibit, the trees were donated to Arlington and, although no longer part of Ono’s project, continue to be used by our visitors for wishing.

CRAPE MYRTLE: Lagerstroemia sp., crepe myrtle, baegilhong 백일홍 (Korean), zǐwēi 紫薇 (Chinese)

ORIGIN: parts of Asia and Oceania

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: highly variable; size depends on species; popular Lagerstroemia fauriei x indica cultivars range from 8 to 30 ft. high and 8 to 30 ft. wide depending on the cultivar

GARDENING NOTES: relatively well-behaved near sidewalks; cultivars include trees with white, lilac, and blood red blossoms; although not native, it provides ecosystem services in novel urban landscapes as a food source for native American Goldfinches and House Finches, at least in parts of the United States; leaves of Lagerstroemia indica in particular turn festive colors in the fall; prefers sunny exposures but can grow in partial shade.

A DESERT DWELLER, Encelia farinosa has a wide range covering dry parts of Southern California, Mexico, and the southwestern USA. Driving through the desert at night, x-ray brittlebush shrubs flicker by like stop-motion animation. During the day, their white stems resemble huge lichens. The Spanish name “incienso” refers to the plants’ sap, which is used as an incense.

“Within the lifetime of children living today,” write scientists Matthew Fitzpatrick and Robert Dunn in the journal Nature Communications, “the climate of many regions is projected to change from the familiar to conditions unlike those experienced in the same place by their parents, grandparents, or perhaps any generation in millenia.”

Of course, we are already experiencing a different climate than previous generations. And under current carbon accumulation rates, in 60 years, summer temperatures in the

Los Angeles region are expected to be nearly 6F degrees warmer on average. This means that the current North American climate we would most resemble in 2080 is Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.

The match is not perfect: Cabo San Lucas does not have Los Angeles’ wet winters and dry summers. But droughts are expected to become more frequent in Southern California, soil moisture will evaporate more quickly, and most of our water will come in fewer, larger, storms.

Whatever happens over the next 6 decades, Southern California’s ecosystems are certain to be under extreme stress. It is likely that some plants will cease to exist in parts of their current range. As a public garden, we are planning for this future landscape by growing species, such as brittlebush, that thrive in warmer, drier regions of the California Floristic Province.

BRITTLEBUSH: Encelia farinosa, incienso (Spanish)

ORIGIN: California Floristic Province including Baja California and desert regions of the southwestern USA

MATURE HEIGHT AND WIDTH: 1-5 ft. high and 4 ft. wide

GARDENING NOTES: yellow daisy-like flowers appear in the spring; very low water needs, can survive on rainfall once established in their “natural” range, although as discussed below, the changing climate will change the contours of this range; looks best in full sun away from the coast with limited water in quick-draining rocky or sandy soil; loses foliage in drought.

Scrub jays, squirrels, and other animals are an essential part of the regeneration and proliferation of coast live oaks. In fact, the mutually beneficial relationship between corvids, like scrub jays, and oaks is literally world-changing, as it is one of the main engines of grove creation worldwide. A study conducted near Carmel along the California coast found that individual jays cached — that is, stored for future consumption — an average of 5,000 acorns in a year! Each of these acorns was hammered in the ground, one at a time, repeated over-and-over-and-over-again.

With an impressive recall ability, scrub jays return to around 95% of their cached acorns. The 5% of acorns that they don’t recover often germinate in the ground, safe from herbivores. Some of these acorns grow into new oaks outside their mother groves and make forests.

Some scientists theorize that the high carbohydrate content of acorns functions to increase animal hoarding. Carbohydrate-rich acorns quickly sate the hunger of animal foragers

like jays. Once full, many foragers will collect and store additional acorns in the ground, increasing their chances of germination. The thick shells of acorns are thought to reinforce this behavior: the longer it takes to gnaw or peck through a shell, the more vulnerable the animal is to predators. Hence, rather than eat an acorn on the spot with all of the attendant risk, hoarders are more likely to store their meals for later.

California’s live oaks live so long and are so prominent in the landscape that they take on mythological significance. The dramatically-named “Oak of the Golden Dream” near Santa Clarita is associated with the first documented non-Indigenous discovery of gold in California. The “Lang Oak” in Encino was a famous 1,000 year old tree with a 24 ft. circumference trunk. Orange Grove Blvd, west of Arlington Garden, is out of alignment with other major north-south streets in Pasadena. The street was built to connect two large, well-known oaks, one of which stood near the garden at the intersection at California Blvd. and Orange Grove Blvd. Pasadena residents loved the oak so much that they raised funds to build a long circular bench around it in 1884. A local newspaper optimistically predicted, “We presume this spot will someday be like unto the ancient forum at Rome, where the philosophers and orators of Pasadena may come to discuss the questions of the day.” Unfortunately, this admiration for the tree is what killed it. Construction of the road around the oak’s understory was likely the cause of its demise in 1911.

measured 20 feet in circumference. Its canopy stretched 200 feet across. A drawing of the tree by the artist Edward Vischer in the 1800s shows a smooth trunk terminating abruptly in a bundle of muscular arms resembling a giant squid.

The tree was a sacred site to the native people of Los Angeles County — the Tongva, Kizh, or Gabrieleño — who gathered under its branches and used the surrounding area as a burial site. In the 1830s, a French immigrant constructed a winery near the tree — did he know that people were buried there? — and over the decades, it expanded until the tree was cut back and fenced in on three sides. This was not a healthy habitat for the tree, and it succumbed to industry, convenience, and disregard for the older world that was becoming Los Angeles.

In 2019, the City of Los Angeles installed a historical marker for the tree in an unwalked strip of pavement between a strip club and the freeway. Invasive weeds grow along one side and razor wire on the other, but it is near the original site. Chief Ernie P. Tautimez-Salas, who wrote the inscription, ends it with this promise: “while its physical presence is gone, the oral history handed down through the generations has kept its beauty and story alive in the Kizh people.”

Although there is disagreement about the exact nature of the relationship, oaks have an important connection with “mycorrhizae” — subterranean fungi that associate with plant roots. Many scientists believe these fungi coat or infiltrate the roots of oaks and surrounding plants, providing them with water and hard-to-access nutrients from the soil. In return, partner plants share (or the fungi take) energy in the form of sugars and other essential elements of life.

Bernabé Cobo described chicha de molle thus:

It produces a little red fruit in racemes like the willow of which the Indians make chicha, and it is so strong that it makes one drunk more than that which is made of maize and other seeds, and the Indians consider it more valuable and a delicacy. (Bernabé Cobo, Historia del nuevo mundo , 1653; translated by Sophie Coe; quoted in Sayre et. al. “A marked preference.”)

desiccation. Similarly, the leaves of bladderpod fold together along their center in times of drought — slender hands folded — reducing the leaf area exposed to the elements and increasing water retention.

In a study published in 2019, Dylan Stover reports that bladderpods create “islands of fertility” around themselves by increasing nutrients like phosphorus in the soil. These nutrient-rich islands may also help buffer the plants from the effects of drought.

According to some sources, traditional knowledge of this drink is disappearing. A 2004 study of the beverage in Peru found only one person who still knew how to make it, and he had not made any since he was a child. Other sources claim the beverage continues to be widely consumed in certain regions of Peru. The process is labor-intensive: 20 liters of chicha require over 4,000 ripe berries, each of which must have its tiny papery sheath and stem removed before boiling! The Spanish, for their part, were responsible for transporting Schinus molle throughout their sphere of influence including California. They were interested in the tree primarily as a spice, rather than an alcohol, and apparently hoped to use it to challenge the East India Company’s black pepper trade.

bladderpod

brittlebush

• p.12

• p.34

buckwheat, california • p.10

conebush species

crape myrtle

grass-like species

live oak, coast

manzanita species

• p.16

• p.32

• p.24

• p.2

• p.22

milkweed, narrowleaf • p.6

olive, fruitless

• p.28

pepper tree, california • p.30

pine, coulter

• p.14

sage, hummingbird • p.8

sagebrush, california • p.18

st. catherine’s lace

sycamore, western

• p.26

• p.4

Author

AJ Jewell, PhD

Illustrator

Emma Rose Fryer

Introduction capri kasai

Design designSimple

Editor

AJ Jewell, PhD

Copy Editor

Scott Oshima

Advisors

Paloma Avila, Levi Brewster, Mayita Dinos, Sybil Grant, Heisue Chung Matheu, Michelle Matthews, Tahereh Sheerazie

Executive Director

Michelle Matthews

Funding

Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust

LA Breakfast Club

All text ©2023 Arlington Garden

Emma Rose Fryer is a botanist and self-taught artist who primarily illustrates California native plants, fungi, and lichens. Born and raised in California, she works mainly in gouache and ink, pulling inspiration from the geometry and form of plant morphology, and from her botanical education. She earned her Bachelor of Science in Botany at Humboldt State University, her master’s at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo working with desert annual wildflowers of the San Joaquin Desert, and will soon begin a Ph.D. working on forest regeneration ecology. While a professional botanist, she has worked as an artist throughout her career to try to inspire people to appreciate and see plants in a new light. Through her work, she hopes to help others appreciate the exquisite form and remarkable diversity of plant life around them.

Learn more about her work at: emmarosefryer.com

Funded by a grant from the Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust with additional support by LA Breakfast Club

Thank you to John Ripley for his research on the Durand Mansion for Pasadena Heritage. Thank you to the Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust and the LA Breakfast Club for their financial support, which made this publication possible.

Local retail nurseries that sell native and mediterranean plants:

Armstrong Nursery in Pasadena armstronggarden.com/armstrong -garden-centers-pasadena

Artemisia Nursery* artemisianursery.com

California Botanic Garden — Grow Native Nursery* calbg.org/grow-native-nursery/gnn

Fig Earth Supply figearthsupply.com

*specializes in CA native plants

Hahamongna Native Plant Nursery* arroyoseco.org/nursery.htm

Moosa Creek Nursery* moosacreeknursery.com

Plant Material* plant-material.com

San Gabriel Nursery sgnursery.com

Theodore Payne Foundation* theodorepayne.org

Tree of Life Nursery* californianativeplants.com