November 12, 2025

Danish artist Thomas Damboʼs five recycled troll sculptures now sprawl throughout Dix Park. Theyʼre here to protect the trees.

November 12, 2025

Danish artist Thomas Damboʼs five recycled troll sculptures now sprawl throughout Dix Park. Theyʼre here to protect the trees.

By Janine Latus,

4 For a decade, the Cary Town Council has barely changed. After Democrats swept last week's municipal elections, that's over. BY CHLOE COURTNEY BOHL

6 With challengers ousting two incumbents, it's the end of an era for the Durham City Council. BY JUSTIN LAIDLAW

9 A Walltown homeowner's foundation is being destroyed by a pipe dumping water from a nine-acre area into her yard. Who’s responsible? BY LENA GELLER

14 Emails show the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary urged Wake Forest's mayor not to recognize Pride or LGBTQ History Month. BY JANE PORTER

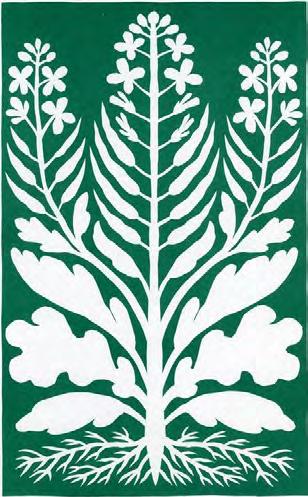

16 Built out of donated barn wood and fencing, former pallets, and 15 tons of used bourbon barrel staves, Thomas Dambo's recycled trolls are ready for visitors at Dix Park BY JANINE LATUS

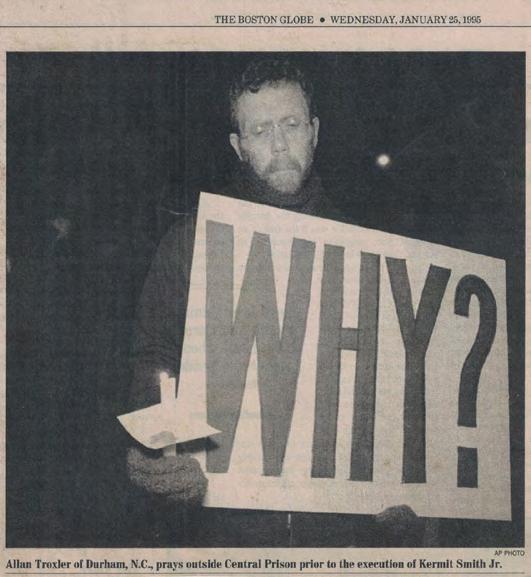

18 “We couldn’t have run the Left in Durham these many decades without Allan’s creative stamp,” artist Pamela George says of the activist Allan Troxler, who died on October 26 at age 78. BY SARAH EDWARDS

22 He may be an introvert and "spiritually Bilbo Baggins," but Raleigh author Christopher Ruocchio is celebrating the final installment of his Sun Eater series in style. BY SHELBI POLK

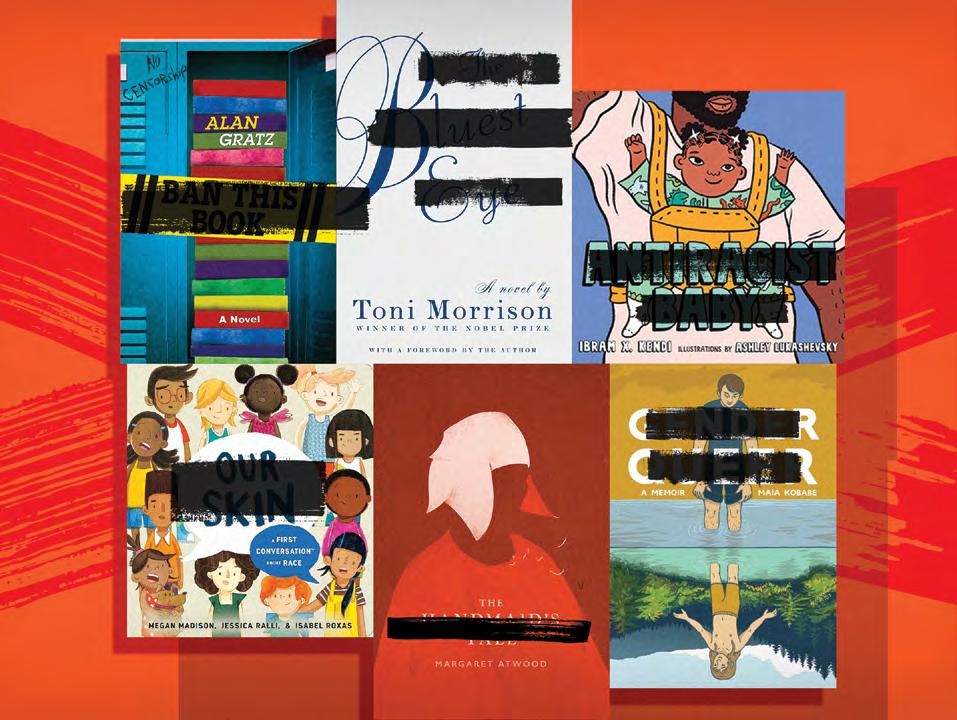

24 New policies are helping protect Wake County public libraries in the face of attempts to ban books, but the threats haven't gone away. BY JASMINE GALLUP News

3 Backtalk 26 Calendar

One of artist Thomas Dambo's trolls now inhabiting Dix Park in Raleigh. IMAGE COURTESY OF DIX PARK CONSERVANCY

Publisher John Hurld

Editorial

Editor-in-Chief

Sarah Willets

Wake County

Jane Porter

Culture Editor

Sarah Edwards

Lena Geller Justin Laidlaw

Chase Pellegrini de Paur Report For America Corps Reporter

Chloe Courtney Bohl

Contributors

Mariana Fabian, Jasmine Gallup, Desmera Gatewood, Tasso Hartzog, Elliott Harrell, Brian Howe, Jordan Lawrence, Elim Lee, Glenn McDonald, Nick McGregor, Gabi Mendick, Cy Neff, Andrea Richards, Barry Yeoman

Editor Iza Wojciechowska

Editorial Interns Eva Flowe Kennedy Thomason

Creative

Creative Director Nicole Pajor Moore

Graphic Designer Annette Winter

In September, Jane Porter wrote about the Wake Forest mayor’s decision to introduce, then walk back, a Pride Month proclamation. Recently, Jane reported (online and on page 14 of this edition) on public records that showed the mayor changed course after Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary leadership urged her to do so. Readers shared their reactions.

From reader JENNIFER HINTON by email:

Just read your piece about the Wake Forest Seminary president convincing Wake Forest Mayor Vivian Jones not to make a town proclamation re: Pride Week.

Like all citizens, religious leaders have the right to speak up and make requests of our government. But it’s clear that [seminary president Daniel] Akin is not concerned about the greater good. He’s speaking for his demographic.

The mayor’s quick capitulation feels like a further erosion of our country’s foundational separation of church and state.

I’m pretty sure that Akin is A-OK with the government sponsored “celebration” of sexual identity that rolled back Roe v Wade.

I’d like my town to be a haven from the right wing enforced anti DEI, kidnappings, abandonment of financial support for our most vulnerable.

Does the seminary president support the worth and dignity of the people who are being brutalized, dragged from their homes, the families being torn apart? How about the worth and dignity of those who are denied Medicare and SNAP?

If he does, how about he takes on these life and death situations.

From my corner of the world it looks like the Christian right is just fine with the government sponsored celebration of sexual identity, as long as it’s white men.

Last month, Chloe Courtney Bohl reported that GoRaleigh bus drivers were again raising concerns about their safety and working conditions. Readers shared their own concerns, and ideas.

From reader LORI MORRIS by email:

This is shameful that we are allowing this crime in our state capital. What is happening to the people who are threatening, spitting etc on the drivers? Are they being arrested? Sent for mental treatment? Banned from taking the bus?? More follow-up and pressure is needed. How do we ever expect to get rapid transit when our buses are unsafe? What is the ACORNS [Addressing Crises through Outreach, Referrals, Networking, and Service program] you mentioned doing in the city as a whole? I never hear about them. How much is that costing taxpayers? Why is it that when I go to certain areas like around New Bern Ave and Trawick area, I can notice the crime going on and nothing is done about it? Please keep investigating! Thank you!

From reader ANNE AVERA:

I rode the public bus system in Brighton, England, every day for two weeks back in 2022. The drivers sit in a metal and plexiglass “booth” where they drive. They use a key from the outside to get in, and also when they change driver shifts.

How party politics, strategy, and money factored into last week’s results, and what it means for the next town council.

BY CHLOE COURTNEY BOHL chloe@indyweek.com

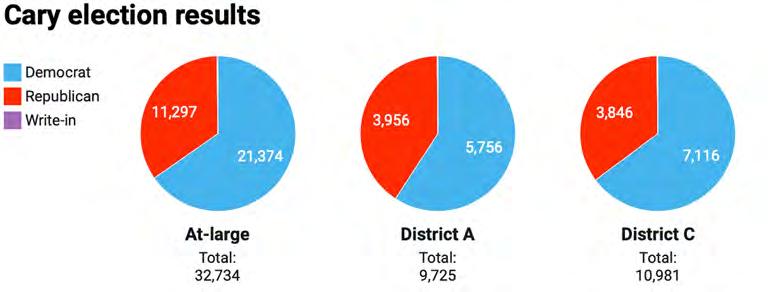

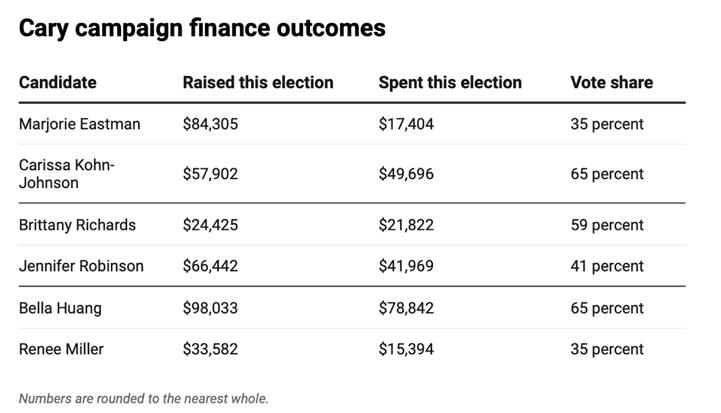

Last week, Cary voters elected three Democrats to the town council over their Republican opponents. Carissa Kohn-Johnson will continue as an at-large council member, and Brittany Richards and Bella Huang will take office in Districts A and C.

It was a lively, expensive election cycle that clarified what Caryites are looking for in their local leaders. Here are our takeaways from last Tuesday’s results.

1 Democrats swept the board in these officially nonpartisan races.

None of the three Cary Republicans even came close to besting their Democratic counterparts. Kohn-Johnson defeated Marjorie Eastman by a 30-point margin in the at-large race. Huang also beat Renee Miller by 30 points

in District C. And in District A, Richards defeated Jennifer Robinson, the incumbent, by 18 points.

It makes sense that the most competitive race of the night was between Richards and Robinson, who held office for 26 years and is the most moderate of the Republicans who ran. It’s possible that her association with two more vocally conservative, less-experienced candidates dragged her down: her loss stands out as particularly brutal considering she coasted to reelection in 2022 and 2017. Robinson didn’t adopt Eastman’s and Miller’s MAGA-tinged talking points, but the three candidates campaigned together and appeared side by side on the Wake GOP-endorsed slate.

“I had many people telling me that they had supported me in the past but would not vote for me this year for one reason: I am a registered Republican,” Robinson wrote in an Instagram post last week.

ILLUSTRATION BY NICOLE PAJOR MOORE

On a more granular level, the Cary Democrats look just as dominant as their top-line victories suggest: Huang beat Miller in every precinct, while Kohn-Johnson and Richards both won in all but two of their precincts.

Taken together, these unambiguous victories point to a successful organizing push by the Wake County Democratic Party (WCDP), which was very active in Cary this fall. At an Election Night watch party in downtown Cary, Richards told a room full of WCDP volunteers that they collectively knocked on 4,000 doors ahead of the election. Kohn-Johnson also credited the Wake Dems for her win.

“This worked because we have really committed volunteers, but we also have paid staff. We need more paid staff,” she said. “So I’m going to work really hard …. What I’m going to start doing is raising money for Wake Dems. I just wanted to make a very public commitment to Wake Dems.”

The Democrats’ clean sweep fits into a trend that’s been unfolding in Cary for a few years now. In fact, once the newly elected council members are sworn in this December, the town council will be composed of all Democrats. That’s a major shift from just a few years ago, when the town council had a couple Republicans and a couple unaffiliated members who leaned to the right.

The sweep also fits into a broader pattern of Democratic victories across the county: WCDP-endorsed candidates defeated conservative or Republican incumbents in Holly Springs, Fuquay-Varina, and Wake Forest this year.

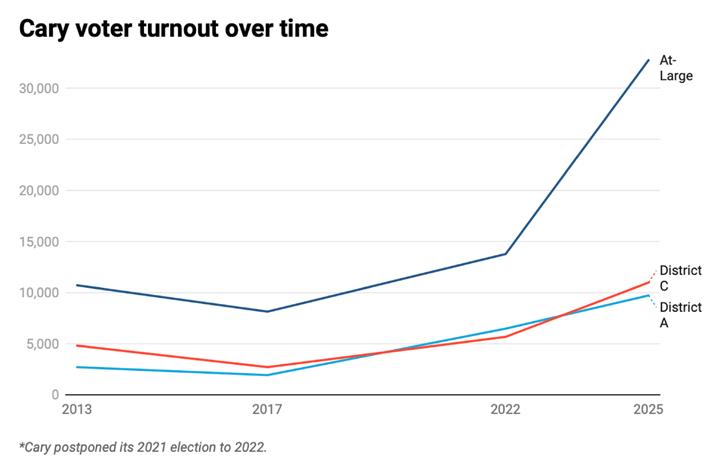

1.5 More voters showed up for these elections than usual.

Voter turnout exceeded past election cycles in all three Cary Town Council races. The at-large race saw the most dramatic jump, with about 32,700 people casting ballots this year compared to about 13,700 in 2022.

The high turnout could have something to do with the partisan nature of these contests—every candidate on the ballot was backed by the Wake Dems or Wake GOP, which provided resources and get-out-the-vote support. Back in May, WCDP chair Wesley Knott told the INDY he would be mobilizing volunteers across the county to knock on as many doors as humanly possible between Labor Day and Election Day.

SOURCE:

2Money mattered, but it wasn’t the best predictor of victory.

There wasn’t a clear correlation between candidates’ fundraising or spending and their final vote share. Huang and Kohn-Johnson outspent their opponents by wide margins, but Richards trailed behind Robinson on both fundraising and spending, and she still won her race with 59 percent of the vote.

Richards raised most of her money in small increments from local donors. Robinson also had a long donor list, but a big chunk of her cash came in the form of large donations from people in the real estate/ development industry.

Huang, who cofounded a political action committee that raises money for local Asian American candidates, fundraised the most: 187 mostly local donors gave her about $524 each on average.

Eastman was the second-highest fundraiser out of the Cary candidates this elec-

tion cycle, though she didn’t spend much of her haul. Her average donation was about $760. Real estate–adjacent people donated to her campaign, but her top contributors were former council member Ken George ($6,000), his wife Karen George ($6,000), and Cary residents Charles Eastman ($6,800) and Colleen Baker ($6,800).

3For a decade, the Cary Town Council barely changed. That’s over now.

Before the 2022 municipal elections, six of the Cary Town Council’s seven members had been in office for at least 10 years. Kohn-Johnson defeated an incumbent that year, and in 2023, two more new members (Michelle Craig and Sarika Bansal) joined.

Now that Huang is replacing Jack Smith and Richards has defeated Robinson, relative newcomers will soon outnumber council veterans five to two.

SOURCE:

Come December, mayor Harold Weinbrecht and at-large council member Lori Bush will be the longest-serving active town council members, with about 18 and 14 years under their respective belts. Kohn-Johsnon will be the next-most-experienced member as she begins her second term.

“New voices” was a theme of this campaign cycle, particularly for Richards, who believes hers is what gave her an edge over Robinson.

“The biggest dimension of my race was people craving a fresh voice after having had a longtime incumbent in office,” Richards told the INDY on Tuesday once she learned she’d won. “The results show that … there were folks in the community that appreciated my opponent’s service, as I have as well. But I had told people from the beginning that I was running not because she was ready to step down but because I was ready to step up.”

Huang also campaigned as a newcomer with a fresh perspective to bring to the town council. She joins a small but growing number of Chinese American elected officials around the Triangle. Her opponent, Miller, may not have been an incumbent, but she was a known quantity as a returning candidate (she also ran in 2022), Greenway Committee member, and frequent public commenter.

One fresh voice Caryites didn’t seem to have an appetite for was Eastman’s. She was the most MAGA-aligned candidate in this race with the most overtly negative campaign. Kohn-Johnson told the INDY she strategically avoided slinging mud with Eastman.

“This is a referendum on negativity in pol-

itics,” Kohn-Johnson said. “I never said my opponent’s name—didn’t talk about her— and it worked.”

4The next Cary Town Council has a mandate to preserve town services, make strides on housing affordability … and raise taxes, if they must.

The Republicans in this race tried (to varying degrees) to make it about the budget being too big and taxes being too high.

The Democrats talked about how great Cary’s town services are, how beautiful its parks, how innovative its development projects—justifying the cost of living in town rather than arguing about the bottom line. Voters embraced that message, granting the town council their implicit blessing to keep doing what it’s doing.

One area where this year’s candidates seemed to be out ahead of the current town council was on affordable housing. Huang, Kohn-Johnson, and Richards all spoke about the need for more diverse, affordable housing types that are accessible for Cary’s service and public sector workers. All three of them told the INDY they want Cary to work with private and nonprofit partners to build more affordable housing, something the current council has only just begun to explore. Richards also told us she’d be open to implementing “more creative zoning decisions” to add smaller housing types in Cary that are inherently more affordable. All three of the newly elected candidates also seem open to another affordable housing bond referendum, provided it’s specific and engages the community.

SOURCE: NC STATE BOARD OF

Durham’s municipal elections were expensive and at times ugly, with firm lines drawn between candidates. Here’s what the results mean for the Durham City Council and its work ahead.

BY JUSTIN LAIDLAW jlaidlaw@indyweek.com

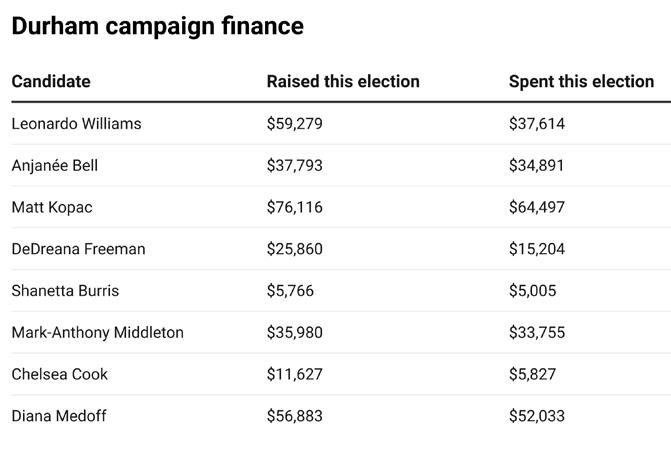

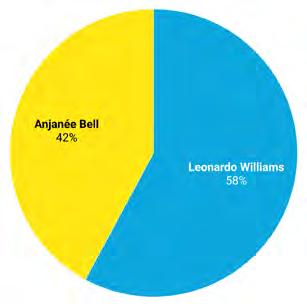

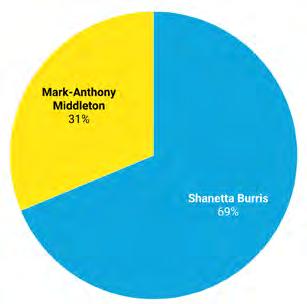

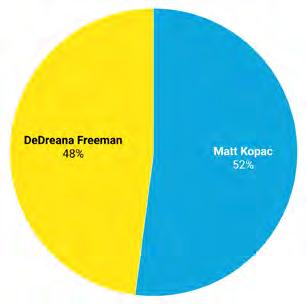

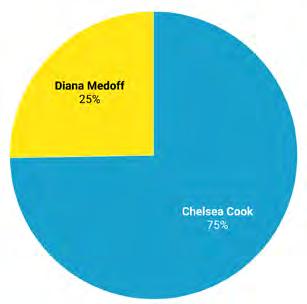

Durham elections crossed the finish line on November 4, resulting in the return of some familiar faces, and the introduction of new leadership in city hall. Mayor Leonardo Williams won his bid for reelection over challenger Anjanée Bell, and incumbent Ward 3 representative Chelsea Cook won decisively over Diana Medoff to earn their first full term on council.

Two other sitting councilors, DeDreana Freeman and Mark-Anthony Middleton, were ejected from their seats. Freeman lost a close contest against Matt Kopac in Ward 1, and Shanetta Burris won handily in Ward 2 against Middleton.

The knock down, drag out competition was expensive and, at times, ugly. Now that the dust has settled, the seven-member body must turn campaign stump speeches

into substantive policy decisions. The battle may be won, but the war for Durham’s future wages on.

Here are five takeaways from Durham’s municipal election.

1 It’s the end of an era.

After a productive, albeit contentious, eight years, Freeman and Middleton’s watch has ended. Durham voters welcomed new voices to Ward 1 and Ward 2, electing Kopac and Burris to those respective seats, held by the incumbents since 2017.

Middleton, a pastor and podcast host, brought an orator’s verve to city hall. The mayor pro tem is frequently the coun-

cilor who will go deep on explaining the nuances of city policy and the limitations the council faces. But his willingness to be matter-of-fact in the face of deeply emotional discussions about Durham development, crime, and other issues often made him the “bad cop” during meetings, and he started to lose efficacy with a growing faction of Durham residents.

On Tuesday, Middleton told the INDY he felt his “brand took some hits” that soured his relationship with some residents, even though he continued to have the support of other leaders and electeds in the community, past and present.

Freeman, often positioned as Middleton’s foil, has a loyal fan base and has kept equity at the forefront since she was elected in 2017. But her brand also suffered a few setbacks over the years, including frequent tit-for-tats with Middleton on the dais. Their candidacies became avatars for the disagreements about Durham’s future prospects. In some ways, it felt as though their fates were intertwined. One could not survive without the other.

2 In line with national trends, turnout was high.

Turnout was unusually high, especially for an odd-year election cycle. About 46,000 voters cast ballots (a bit over 21 percent), which followed an encouraging trend of civic engagement nationwide on Tuesday. In more recent Durham elections, that number was almost 19 percent in November 2023 and about 15 percent in November 2021.

In Ward 1, the most contested race, Kopac and Freeman were only separated by 1,841 votes. Kopac did well in southwest Durham neighborhoods like Hope Valley and Old West Durham that make up Ward 3, whereas Freeman locked up most of east and southeast Durham

INDY calculated the totals above by adding up candidates’ detailed receipts and expenditures reported during the election cycle. Source for campaign finance and vote data: North Carolina and Durham County boards of elections.

which is a majority of Ward 2 and covers Hayti and the neighborhood around North Carolina Central University.

For ballots cast on Election Day by Ward 1 voters specifically, Kopac received just 741 more votes than Freeman out of 10,247 cast (which does not include write-in or early votes).

According to the city website, the ward system was created to “provide representation for different areas of the city.” Even though the candidates must live in the ward they seek to represent, all voters can select candidates in all three ward races.

3

How the new council will vote on development isn’t clear cut.

Development was the defining issue this election cycle. Not only did candidates have to stake out a position on how to manage Durham’s accelerating growth, but whether candidates took funding from the real estate or development fields was a crucial litmus test for many voters who believed it suggested how candidates would approach zoning and development.

The current council often agrees on rezoning cases, but when they split, it tends to be four in favor and three against, with Middleton firmly in the majority and Freeman firmly in the minority. Both Burris and Kopac have talked about bringing a balanced approach to the rezoning cases that come before the city council.

Even with Kopac’s record on the Durham Planning Commission to pull from, it’s unclear whether the new electeds will drastically change the vote split, even if they vote differently from their respective predecessors. Still, now that Kopac and Burris are officially headed to city hall, nuance is precisely what will be required to form effective policies that satisfy Durham’s growing needs.

An important tool for how city council manages growth is the Unified Development Ordinance (UDO), a legal document that sets the laws for development in Durham. Kopac, Burris, and the rest of council will oversee the adoption of the new UDO early next year, which could significantly impact the types of cases brought before them. How will the incoming council roster put their stamp on the UDO, and what outcomes might it yield for present and future Durham residents?

4Less money didn’t mean more problems.

In season 1 of The Wire, Detective Lester Freamon tells his colleagues, “You follow

drugs, you get drug addicts and drug dealers. But you start to follow the money, and you don’t know where the f*ck it’s gonna take you.”

In Durham, the paper trail led to small donors, other elected officials, people in real estate and development, and a handful of whales making a splash.

Money raised did not directly correlate with success, mimicking outcomes in nearby Cary. Kopac raised the most of any candidate and three times Freeman’s haul, yet won by only a slim margin. Burris raised the least of any candidate and one-sixth of Middleton’s total, yet won with nearly twice as many votes, and greatly increased her victory margin between the primary and general election.

In Ward 3, Diana Medoff raised nearly four times as much as incumbent Chelsea Cook, and the second most of any candidate in the race, yet she lost by the widest margin of any contestant in the general election.

Fundraising transparency is sorely needed at all levels of government. This election season saw the emergence of a mysterious new 501(c)(4) called Yes for Durham, causing a firestorm of speculation about how “dark money” had infiltrated Bull City politics. Candidates distanced themselves from the PAC, but conspiracies had already seeped into the atmosphere.

During her victory speech on Tuesday night, Burris decried the amount of money flowing through local elections and said she would work to “fight back and push against big money.”

5The new council will be fresh, but not unqualified.

With the ousting of Middleton and Freeman, Durham City Council lost a combined 16 years of experience, leaving Javiera Caballero as the longest-tenured member and the only with more than a full term under their belt other than Williams. Williams will likely tap Caballero to replace Middleton, his friend and close confidant, as mayor pro tem, giving her the responsibility of presiding over meetings and acting as mayor in his absence. As the veteran member, Caballero could also inherit the role of “explainer” during public hearings.

The council roster is relatively young compared to past eras led by elder statesmen and stateswomen like Bill Bell, Steve Schewel, Cora Cole-McFadden, and Eddie Davis, who had years of public service. But youth and inexperience shouldn’t be mistaken for an inability to perform the job. This incoming city council brings a plethora of skills—in sustainability, eviction law, urban planning, economic development, community organizing, and more—that they can leverage to tackle the city’s most consequential issues.

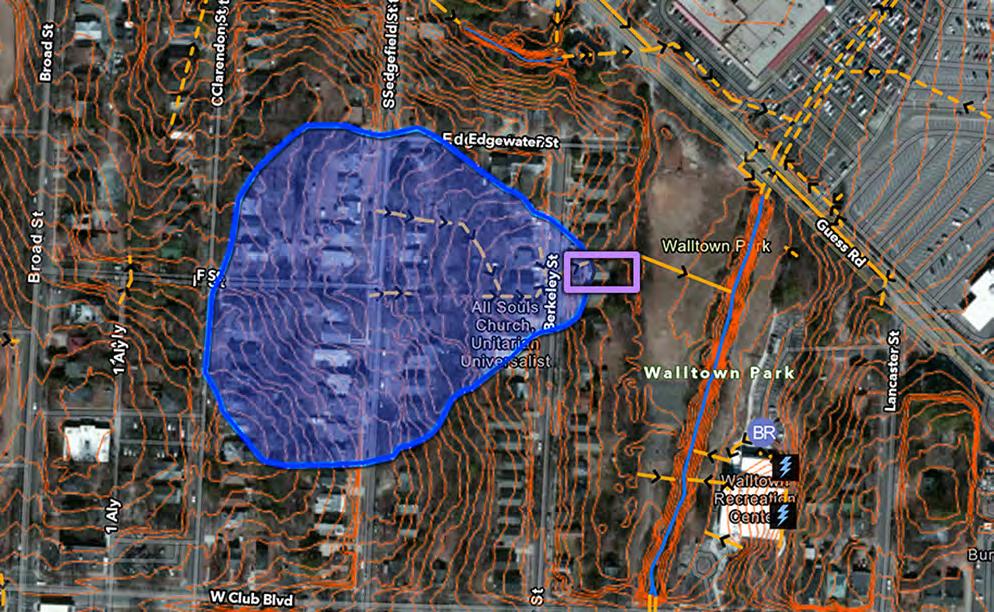

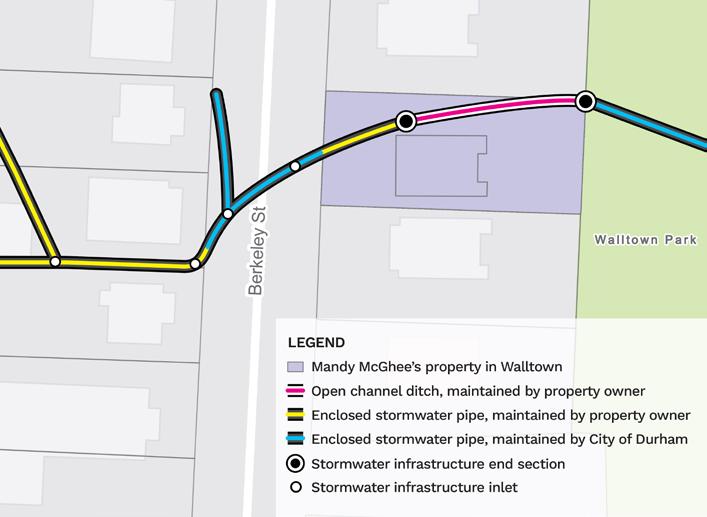

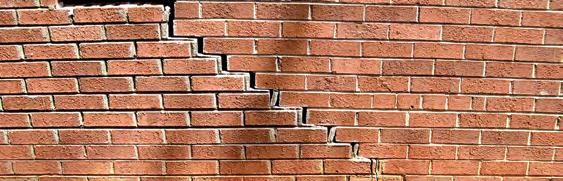

Mandy McGhee bought her Walltown home through a program designed to help low-income buyers build generational wealth. But a stormwater pipe that’s been eroding her foundation for years is putting that goal—and her ability to stay in her home—at risk.

BY LENA GELLER lgeller@indyweek.com

Mandy McGhee’s cousin had come to pick her up for a trip to the grocery store. But first, there was something he needed to show her. He led her around the side of her feather-gray house on Berkeley Street in Durham’s Walltown neighborhood. There, a section of her home’s foundation had collapsed, leaving a wide cavity that exposed the dark interior of her crawl space.

“Did you know about this?” McGhee’s cousin asked. She hadn’t. But she wasn’t surprised.

A few paces from the site of the collapse, a stormwater pipe opens onto McGhee’s property. It’s been dumping water there ever since McGhee moved into her home 28 years ago—and probably for years before that. What McGhee’s cousin discovered that day this spring was the culmination of decades of erosion.

The mouth of the concrete pipe, two and a half feet wide, is half-hidden in an overgrown tangle of vegetation. Its steady flow long ago turned McGhee’s side yard into a permanent wetland teeming with tadpoles.

The pipe collects runoff from an approximately nineacre drainage area, according to Michele Eddy, a Durhambased environmental engineer who spoke in her personal capacity. Eddy calculated the drainage area using publicly available data.

It’s an unusual setup, Eddy says—runoff from an area roughly the size of seven football fields, bearing down on one homeowner’s 0.19-acre yard. And the flow has no doubt intensified over the past decade. As climate change has brought heavier rainfall, and as development has intensified in the area between Duke University’s East Campus and the defunct Northgate Mall, the volume of

water coming from the pipe has grown, putting pressure on aging infrastructure. During a single storm in August, Eddy calculated, 700,000 gallons of water flowed onto McGhee’s property.

McGhee bought her home from Self-Help in 1997 through the community development organization’s Walltown Homeownership Project—a program designed to help low-income, first-time buyers purchase renovated homes in the historically Black Walltown neighborhood and build generational wealth.

Nearly three decades later, the pipe is threatening to destroy what the program was meant to create.

Earlier this year, Durham County valued McGhee’s property, which she bought for $70,500, at $336,971 based on rising values across gentrifying Walltown. In September, after an appraiser came to the site in person and documented the damage to the foundation—attributing the damage to a “city drainage pipe along side of dwelling”—the county reduced the property valuation by nearly 40 percent to $211,439. The house itself is now worth just $21,783.

McGhee’s property sits in a flood zone, and she carries both regular homeowners insurance and flood insurance. She filed a claim to see if the foundation damage would be covered, but it was denied. Now McGhee says her insurance company may drop her coverage entirely due to the damage. That could leave her in breach of her mortgage and facing potential foreclosure.

The pipe is attached to city stormwater infrastructure, and its ownership is listed as “shared” in the city’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) database. So in July,

with help from her neighbor Rafael Mazer, McGhee reached out to the city requesting help. The ask seemed straightforward: there’s another open stormwater outlet behind McGhee’s backyard, right down the hill from the one that dumps on her land. In an email, Mazer asked that the city simply connect them.

The city’s response: the drainage system is on private property, so it’s McGhee’s responsibility to address.

Over several exchanges, Mazer pushed for clarity. How could the city require McGhee to maintain a pipe carrying runoff from multiple blocks? And hadn’t the city installed the pipe in the first place? The city reiterated to Mazer that property owners are responsible for drainage systems on their land, and stated that the city has no records showing when the pipe was installed or by whom—though the city believes it did not install it.

Eventually, Mazer asked if McGhee could just seal off the pipe. The city said no, citing an ordinance. McGhee cannot modify the pipe without obtaining a permit, and regardless, any modifications cannot impede the flow of water.

“It feels like there’s a Catch-22 they’ve put us in, where they’ve said that what falls on Mandy’s property is her responsibility, but also that she needs their approval to do any adjustments or remedies,” Mazer says.

In a statement to the INDY, a spokesperson for the City of Durham wrote that “There is no indication that the City ever accepted or controlled this private system, which means the City is not responsible for it.”

McGhee grew up in Person County, the middle child in a family of six girls and two boys. Her father was a

tobacco farmer—the first one in the area to get $1 a pound for the crop, she says.

She’s never been one to stay quiet when she sees injustice. During her senior year of high school in 1975, after school administrators announced they were updating the dress code to ban halter tops and miniskirts, McGhee led walkouts every day for a month.

In 1984, after graduating from Piedmont Community College, McGhee moved to Durham, looking for work opportunities she couldn’t find in Person County. She got a job washing dishes and eventually became a certified nursing assistant while raising twin sons by herself.

McGhee heard about Self-Help’s Walltown Homeownership Project in the mid-1990s. At the time, she and her sons were living in a rented apartment two streets away from where she lives now. She decided to apply.

The Homeownership Project required McGhee to attend classes on first-time home buying and home maintenance. After McGhee completed them, she was able to receive down payment assistance and buy a home renovated by Self-Help.

During her final walkthrough before closing, McGhee says she asked Self-Help representatives about the stormwater pipe.

“I was standing right here in this room,” McGhee says, gesturing around her kitchen, which is tidy and filled with plants, decorative china mounted on the walls. “I said, what are they gonna do about that?”

McGhee says Self-Help representatives told her that the city was aware of the pipe and would take care of it once she moved in; she just needed to call and ask.

So McGhee called the city, she says—numerous times in the months after she settled into her new home. McGhee says each call involved being transferred in a loop. After her third attempt, she gave up.

“If I had known that the city was not gonna take care of that problem, I never would have signed that [purchase] agreement,” McGhee says.

The city told the INDY it has no records of McGhee’s inquiries from the late 1990s.

Jenny Shields, a spokesperson for Self-Help, wrote in a statement that the organization “can’t speculate on what transpired” regarding McGhee’s recollection that Self-Help representatives told her the city would fix the drainage issue.

“What I can say is that we’re very interested in working with Ms. McGhee and the City to see if we can find a resolution to this situation,” Shields wrote, adding that McGhee reached out to Self-Help in October and the organization offered to meet with her to “determine what, if anything, we can do to help.”

“I think the City ordinance is clear and describes whether the property owner or the City is responsible for maintenance, depending on where the infrastructure is located,” Shields continued. “In spite of this, we want to find the best solution possible, and we’re working with Ms. McGhee and the City to see how we can best assist with this.”

The city ordinance Shields referenced states that “maintenance of drainage systems, both surface and underground, located on private property, is the responsibility of the property owner.”

This is what makes it permissible for a sizable stormwater system—starting with city-owned inlets and extending through hundreds of feet of shared infrastructure across multiple properties—to culminate in a single 60-foot-long pipe that dumps onto McGhee’s property.

The pipe’s “shared” ownership designation in the GIS database reflects a division of responsibility, a spokesperson for the city told the INDY: The city is in charge of the 20 feet that run up to McGhee’s property line. McGhee is responsible for the remaining 40 feet of pipe on her land and everything that pours out of it.

“The drainage channel at this property does not appear to have had adequate erosion protection, which has allowed it to migrate closer to the home’s foundation,” the spokesperson wrote.

McGhee contends that she has maintained the drainage system as best a person could. In the first decade she owned the house, she personally cleared trash and debris and hauled away a tree trunk to try to keep the water flowing. After she developed congestive heart failure in 2011 and couldn’t do the labor anymore, she started hiring people to clear the pipe, she says.

Also in 2011, McGhee fell behind on her mortgage payments as medical bills mounted, and her mortgage company threatened foreclosure. To avoid losing her home, she agreed to extend her loan by 20 years. A mortgage that was supposed to be paid off in 2022 now won’t be satisfied until 2042, when McGhee will be 85.

Watching her home’s foundation fall apart while dealing with the bureaucracy around the pipe has triggered memories of that near foreclosure. Without Mazer, whom

McGhee met at a community association meeting, she doesn’t know how she’d manage, she says. She lovingly calls him her secretary.

Mazer sees helping McGhee as putting into practice what he’s learned from longtime Walltown residents about the work required to sustain their community.

“I moved here recently,” says Mazer, who grew up in Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. “My presence, or the presence of people like me in this neighborhood, is at best complicated, at worst harmful.”

McGhee has quite a few health problems. Beyond congestive heart failure, she has stage 3 kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and severe allergies to everything from pollen and contrast dye to watermelon.

“Can you imagine, a Southern girl who can’t eat watermelon?” she says. “I’m in my own little private hell.”

Her kitchen table is stacked with after-visit summaries from Duke Health. Midconversation about the pipe, she reaches for one of the summaries and flips it over. She draws a diagram—several lines converging at a single point, which she circles over and over.

When it storms, the water from the network of pipes that feed into the one on her property “comes through as a jet,” she says, tracing the lines with her finger.

Danielle Spurlock, a professor of land use and environmental planning at UNC-Chapel Hill, says for a pipe that’s draining water from such a large area, you would expect McGhee’s property records to include an agreement establishing who’s responsible for it.

The INDY went to the Durham County Register of Deeds office to review McGhee’s property records. Her deed con-

tains no mention of a drainage easement or any agreement about who is responsible for the stormwater pipe. The plat map on file dates to 1945 and contains no information about drainage infrastructure. The INDY reviewed over a dozen additional deeds and maps linked to the property, none of which have information about the pipe.

Self-Help directed the INDY to the city for records that might clarify responsibility for the infrastructure, and the city told the INDY it has “found no records or evidence in its inventory of historical as-built drawings or GIS data showing installation, approval, or maintenance of the drainage system.”

The city added that before 1994, property owners could install drainage systems without city oversight or approval. That means there may be no official record of who installed the Berkeley Street pipe or when it was connected to city infrastructure.

McGhee’s home was built in 1920. The property passed through the estate of James B. Warren—a bank vice president and city councilman—and subsequently belonged to a U.S. postmaster, a Golden Belt factory foreman, and a general contractor before Robert Rosenstein, an optometrist who owned dozens of homes in Walltown, acquired it in 1953.

In 1994, Rosenstein decided to sell. Self-Help, which had experience financing affordable housing but had never actually developed it, saw an opportunity to expand its work. The organization wanted to increase homeownership rates among underserved communities, and Walltown seemed like a good place to start.

Walltown was founded around the turn of the 20th century by George Wall, Duke University’s first custodian

after gaining his freedom from slavery, and became home to generations of Black working-class families, many of whom worked at Duke. By the 1990s, the neighborhood faced challenges common to communities that had experienced disinvestment and discriminatory lending practices: Only 20 percent of housing was owner-occupied, and many families were at risk of displacement by gentrification.

Self-Help negotiated to buy all 30 of Rosenstein’s Walltown properties for $11,000 each. The properties were “low cost rental houses” that “had been poorly maintained,” a 2008 report Self-Help produced to assess the Homeownership Project notes.

With funding assistance from the City of Durham and Duke University, among other partners, Self-Help renovated and sold those homes, plus more than 40 others, over the next decade.

Self-Help Director of Real Estate Dan Levine told the INDY renovations were “done by qualified general contractors and (of course) inspected and certified for occupancy by the City.”

Yet the pipe on McGhee’s property was seemingly never addressed during the renovation or inspection processes.

In the 2008 report, which Shields shared with the INDY, Self-Help’s “lessons learned” acknowledge struggles with preparing homeowners for routine upkeep: maintaining central air conditioning systems, cleaning gutters, setting aside money for eventual repairs. There is little reflection in the report on how developers should assess pre-existing environmental and infrastructure risks when selecting properties to renovate.

Spurlock says it’s crucial to assess site conditions before selling homes to first-time buyers who would have limited

resources to address such issues.

“When we place affordable housing in places at risk,” she says, “we’re also placing individual homeowners at risk of having to do even more maintenance than the average homeowner in the same area.”

McGhee isn’t the only person who bought a home through the Walltown Homeownership Project who is facing serious water problems.

Trudie Watson purchased her home on Lancaster Street from Self-Help in 1999. Like McGhee’s, the home is a former Rosenstein property built in 1920. After several years of flooding issues, Watson went to the Register of Deeds and discovered that at some point before she moved in, a creek behind her house had been buried. Self-Help never told her about the buried creek, she says. When heavy rains come, the contours of Watson’s yard funnel water down toward her house, pooling around her foundation. Sinkholes have opened up across her property.

Half a block up the street, Carline Jules, who bought a home on Lancaster Street from Self-Help in 2007, has similar, though less severe, issues. When it storms, water collects under her porch and sits for extended periods, saturating the wood and creating conditions for mold. Over time, this has caused her porch to shift, and Jules worries it may eventually collapse.

In September, Watson appealed her property valuation of $373,675. After an appraiser came to the property and documented the water damage, the county

reduced it by $28,000.

Jules also tried to appeal her property valuation this year but was unsuccessful. Now she’s focusing on what she can personally do to manage the water, like digging trenches filled with gravel and planting a “rain garden” to aid absorption.

Levine told the INDY Self-Help is reaching out to Watson and Jules.

“We totally understand the nature of global warming means flooding has become more of an issue, not only in Walltown, but across the city and beyond in ways that were unheard of 30 years ago,”

Levine wrote, adding that the work SelfHelp did throughout the Homeownership Project decades ago “doesn’t address the broader issue of extreme weather events, problems with public infrastructure, and topographic challenges.”

For McGhee, the clock is ticking. She says her insurance company has given her until March to repair the damage to her foundation. She wants the city or SelfHelp to address the pipe first—it wouldn’t make sense to repair the foundation if the pipe is still eroding it, she says.

Her immediate priority is getting her property valuation lowered even further than it was already reduced earlier this year. She has a hearing to appeal her most recent valuation on November 12. She’s hoping to get the value of her house reduced to zero.

The goal isn’t building generational wealth anymore, she says. It’s simply to stay in her home. W

Public records show Wake Forest mayor Vivian Jones retracted a proclamation recognizing the LGBTQ community after the president of the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary asked her to. Last week, Jones lost reelection to her seat.

BY JANE PORTER jporter@indyweek.com

When Wake Forest mayor Vivian Jones walked back her Pride Month proclamation in September, she did so at the request of leaders of what’s arguably the town’s most powerful institution: the Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, which owns hundreds of acres of land in the northern Wake County municipality and occasionally partners with the town on development projects. It was a decision that may have cost Jones her reelection. Public records from the Town of Wake Forest, initially reported by Wake Forest resident Tom Baker IV in a local Substack called Wake Forest Matters, show the seminary’s president emailing Jones on September 5—three days after Jones announced her intention during a town board of commissioners work session to make the proclamation in

October—urging against the move.

“While I fully affirm the dignity and worth of every individual, including those in the LGBTQ+ community who are made in the image of God and deserving of love and respect, I must respectfully express my opposition to a government-sponsored celebration of sexual identity,” wrote Daniel L. Akin in an email with the subject line “Reaching out on a Concern” and addressed to “Vivian.”

“Government has the difficult task of serving all its constituents, and sometimes that means refraining from actions that elevate one perspective over another,” Akin continued. “Not issuing a proclamation does not diminish anyone’s humanity or rights. It simply acknowledges the diversity of our town.”

Akin signed off on the email, “Danny.”

In a Facebook post to the Town of Wake Forest’s page on the evening of September 9, a message attributed to Jones stated that she had mixed up Pride Month, which traditionally happens in June, with LGBTQ History Month, which “is observed in October in cities and towns throughout the United States.” Jones added that she had come to the decision that Wake Forest will not recognize Pride or LGBTQ History Month at all. Some of the language in Jones’s statement echoes language in Akin’s email.

“A government-endorsed PRIDE month, while intended to support one group, may unintentionally alienate another,” Akin wrote. “It risks sending a message that the town officially supports one set of beliefs while disregarding another deeply held by many in our community.”

“I now realize that by expressing support for our LGBTQ community I may have unintentionally suggested the Town’s official support for one set of deeply held beliefs over another set just as deeply rooted,” Jones wrote in her statement. “Therefore, after careful consideration and as an acknowledgement of the diversity of convictions throughout our community, I have decided not to proceed with issuing any proclamation related to LGBTQ History Month.”

According to the public records, which were shared with the INDY, and which Town of Wake Forest staff provided copies of last week, Ryan Hutchinson, the seminary’s executive vice president for operations, forwarded Akin’s message to Wake Forest town manager Kip Padgett with the brief note “FYI,” just one minute after Akin sent his message to Jones.

On the afternoon of September 9, Hutchinson emailed Padgett again referencing Akin’s original message.

“Our desire is not for the town to act in a discriminatory manner, but to represent all the people of Wake Forest,” Hutchinson wrote. “We hope that the mayor changes her position on this matter. However, the seminary does need to consider its partnerships and whether they can continue to exist in situations when parameters change. This does not mean our values have to align perfectly in those partnerships. However, some issues mean that we cannot partner.”

That evening, records show, Bill Crabtree, the town’s communications and public affairs director, emailed town staff about a draft of Jones’s social media post that he was planning to publish on the town’s Facebook page.

“Please let it marinate and—unelss absolutely necessary—hold off on posting anything else on the Town page until tomorrow,” Crabtree wrote. “We are aware that it will provoke a firestorm, but it must be done.” He posted the message after eight p.m., and by the next morning, it had racked up nearly a thousand comments.

According to the records, a call between Jones and Hutchinson also took place on September 9. The call is referenced in a September 12 email from Akin to Jones, thanking her for making contact regarding “[her] decision to remove the proclamation from the [October town council] agenda,” which would have made the town’s proclamation of October as Pride Month, or LGBTQ History Month, official.

“I know this was not an easy decision, but I appreciate your willingness to listen,” Akin wrote. He added that he had seen the responses to Jones’s Facebook post and lamented “that social media is so often a seedbed for unhelpful interactions that mischaracterize and spread false information.”

Jones responded to Akin on September 16. She said the proposed Pride proclamation “became political immediately,” unlike others in the past marking Arbor Day or Building Safety Month, for instance.

“This proclamation was different; it created division and discord,” Jones wrote. “It was not what was best for the Town.”

Akin and Hutchinson did not respond to requests for comment for this story. Jones sent along a brief response to a request for comment on the September emails.

The group’s messages provided prewritten language for members to send to Wake Forest commissioners to oppose the proclamation, asking town leaders not to promote a “second Pride Month,” a confusing request as Wake Forest Pride has, for the past two years, been celebrated only in October.

Hundreds of people from across North Carolina emailed the commissioners and mayor with the subject lines “Do Not Proclaim October Pride Month,” “Stand With Commissioner Faith Cross,” and “Respect Community Values in Wake Forest,” the public records show.

The subject line of the group’s initial email referenced the municipal election. Jones went on to lose reelection to the mayor’s seat to sitting town commissioner Ben Clapsaddle by more than 40 percentage points.

The Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary is affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention and has operated in Wake Forest since 1951, when it was a part of the original Wake Forest University’s campus. The seminary owns about 600 acres of land in Wake Forest, including its central campus, student housing, a golf course, and undeveloped land. The town and the seminary have partnered on various projects in the past, including a 200-acre mixed-use technology park and an 18-hole disc golf course. Last year, UNC Health Rex announced it was seeking approval to build a $462 million hospital in Wake Forest on a 50-acre parcel of land the seminary owns. But in February, state regulators turned down the proposal.

“We hope that the mayor changes her position on this matter. However, the seminary does need to consider its partnerships and whether they can continue to exist in situations when parameters change.”

“As I have stated, I always try to make decisions based on what is best for Wake Forest,” the mayor wrote in an email to the INDY. “I realized very quickly that this was causing deep divisions in our community and that was not in the best interest of our community. This did not stop the Pride Fest; it was held as scheduled. I attended and enjoyed it.”

While town and seminary leaders exchanged correspondence over the proposed proclamation, the North Carolina Values Coalition—a socially conservative Christian group that has lobbied for book bans and anti-LGBTQ legislation, including House Bill 2—was email-blasting its members about the issue, urging them “to stand with” Wake Forest town commissioner Faith Cross, who had said she opposed the Pride Month proclamation during the September 2 work session.

In his email to Jones, seminary president Akin referenced the long-standing “partnership” between the town and the seminary and praised Jones’s leadership of the town for more than two decades. The two are apparently personal friends; Akin mentions his “earliest days [in Wake Forest] when I was a regular at your beloved restaurant, Jovi’s” in the 1990s, and Jones wrote that she considers herself “blessed to have known you for so many years.”

“I want to express my sincere appreciation for the way the Town of Wake Forest and the Seminary have worked together over the years,” Akin, who announced this month that he will retire in July of next year, wrote in his initial email. “This partnership has flourished in large part because of the tone you’ve set as Mayor, one of mutual respect, shared heritage, and a commitment to the good of all who call Wake Forest home.”

After more than 20 years of service in the mayor’s office, Jones will be retiring from her role, too.

Danish artist Thomas Dambo’s five recycled troll sculptures now cavort throughout Dix Park. They’re here to protect the trees.

BY JANINE LATUS arts@indyweek.com

The artist Thomas Dambo sat under the oak tree at Dix Park for easily half an hour, gazing at the Raleigh skyline. The father troll, Daddy Bird Eye, would go here, he decided, where he could keep watch over the family. Mother Strong Tail would lie on her side in the forest about three-quarters of a mile away, her 620-foot tail trailing through the trees, its tip held by Dix, the baby troll, who now stands at the edge of the woods gazing across Flowers Field. The tail would serve as a curving boardwalk for adventurous visitors to explore deeper into the woods.

Dambo, 46, a Danish artist who works almost entirely with recycled materials, brought his team to North Carolina in October to build the largest collection of his trolls anywhere in the United States, with five at Dix Park and

one each in High Point and Charlotte. There is also a traveling exhibit opening in November at the North Carolina Arboretum in Asheville, part of the region’s push to revive tourism in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene. There are currently 139 trolls across 19 states.

Before Dambo became world renowned for his troll sculptures, during his years working as a hip-hop performer and street artist he also worked in a factory in Denmark that had a mountain of scrap wood out back.

“Always, a garbage truck would come and drive away— and I was like, this could become something beautiful!” he says. “This mountain represents trees in forests standing all around the world, where these products that sat on those pallets were produced, and I got the thought that it could be cool if I could create an army of trolls with the

message to protect those forests and place them in those forests around the world.”

Dambo’s captivation with trolls began as a child, when he’d check out library cassette tapes about Den Søde Lille Trold, or the Cute Little Troll. That troll, which lived in the forest protecting all of the animals, lived on in his head and eventually evolved into 171 giant troll sculptures in 23 countries around the globe, each with its own story of saving the world. Dambo’s trolls are cuter and friendlier than the malevolent trolls of Scandinavian mythology, but the Norse tradition of trolls protecting the forest goes back centuries.

Dambo’s motto for life and work: Waste No More. Thus, the food on-site during the three-week build is vegetarian, served on compostable plates. As he speaks, he interrupts his stride across the field to scoop up a random piece of litter. Then another. For the Dix Park event introducing the trolls, he eschews chairs set up in a field and insists instead on the gathered standing in the forest, the sound of power tools and children’s laughter in the background. Each troll installation is a meld of topography and recycled construction materials, and a story. The Dix Park trolls are a family—a mother and father and three mischievous younglings—all intent on protecting the symbolic Grandmother Tree from destructive humans. As Dambo says in a poem he wrote to introduce the trolls, “One species all trolls have learned to fear through evolution / invasive, a pollution, you must never trust a human.” The trolls’ neck-

laces provide clues to Dambo’s story of how they have cast a spell on the Grandmother Tree to make it look no different from all of the others, since “a human seeks the oldest trees, to kill and cut them down / and chop it into tiny pieces, haul it, burn it in their town.”

When Dix Park Conservatory put out a request for volunteers to help build the trolls, the website crashed—so many were eager to help build the magic. Many of their shifts begin with Dambo reciting one of his poems, stories told in iambic pentameter, before he leads his workers back into the woods.

Dambo and his team craft the trolls’ faces back at their workshop in Denmark, somehow projecting compassion, kindness, and impishness with flat planes and sharp angles. The irises are left out of the eyes until the trolls are complete. Installing them is the final touch that brings each troll to life. At Dix, their bodies are built of donated barn wood and fencing, former pallets, and 15 tons of used bourbon barrel staves, black with char and redolent of whiskey. Over three weeks, 336 volunteers swarm the site, sawing and screwing the barrel bits to create the mama troll’s tail, each bite of the jigsaw releasing the rich bouquet of Kentucky bourbon. Other workers gather twigs and branches that turn into troll hair, while Dambo’s team of “professional troll builders”—he says this with a twist of humor—craft the structures that sit behind the volunteer-built cladding, turning disparate scraps into the image in Dambo’s mind.

The works are not precise; most of the builders are not professionals. Dambo is comfortable with this asymmetry.

“For me, perfect detail weighs less heavy than mass inclusion,” he says, “and I try to design my sculpture to welcome all skills.”

The tail, he thought, would be a perfect way to invite community involvement. It’s low to the ground and forgiving of mistakes. No need to put volunteers in danger on scaffolding while still giving them the magical experience of building a troll and knowing that children and families will feel glee and delight discovering something they helped bring to life.

Dambo and his trolls were invited to Dix Park by Kate Pearce, executive director of Dix Park, and Nick Smith, chief of staff of Dix Park Conservancy, a nonprofit dedicated to developing the park. Dambo was drawn not just by the rolling hills and patches of forest, but by the history of the land. “I love the story of how this used to be a hospital and now it has been revitalized to be something else,” he says, “and I like to be part of this mission.”

It is all of a piece: recycled materials on recycled land.

Pearce follows up: “This land is a place of reinvention, of restoration, a transition from Native American hunting ground, to a plantation with an enslaved workforce, to the state’s first mental health hospital, to now what we hope will be the most amazing urban park in America. So this idea of transition and transformation and reuse of material—that vision and ethos plays into everything Dix Park is.”

The trolls are spread around the 308-acre park. Walking among them takes about an hour, and that hike is part of Dambo’s goal. “My art is about getting people off of their screens and getting children out to experience all that magic that I experienced growing up, like searching in the forest,” he says. “I’m always imagining my own kids going on that hike. It’s easy to be motivated if you’re going to see trolls!”

Dix Park Conservancy won’t reveal how much it cost to bring the trolls to Raleigh. Other communities have seen

a huge return on their investment, though. The Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens got its five trolls in 2021, and visitation to the gardens has since jumped by two-thirds, from just over 204,000 people in 2020 to more than 331,000 in 2025. Membership in the gardens rose from 5,970 families in 2020 to 7,645 in 2025.

“Families were saying, ‘Because the trolls are here and our kids are obsessed, let’s get memberships,’” says Katie Hey, the garden’s marketing and communications director. With memberships running at $125 per family per year, that increase means real money. Plus, many of the visitors come from far away, paying $25 for a day’s admission.

“Troll tourism is a real thing,” says Hey. “People are traveling around the country to see these.”

In tiny Detroit Lakes, Minnesota—population 10,000— five trolls have brought in 75,000 to 100,000 visitors a year since they were unveiled in June 2024, says Amy Stearns, executive director of Project 412, the local nonprofit that spearheaded efforts to bring the trolls to town. And while lodging was down throughout the state last year, hotels in tiny Detroit Lakes have stayed full, with bus tours coming up from Minneapolis and visitors trickling in from around the world.

She describes Dambo as “just a giant fabulous kid, full of energy and delight.” He’d run to a tree and strike a pose, saying, “What if there were a troll right here peeking around it?”

At Dix, the trolls are now in place, guarding the grandmother tree, delighting families, and enticing more andmore people to explore. You can find the winsome trolls frolicking throughout the park, wielding their magic both to protect their beloved forest and to delight visitors with their magical whimsy. W

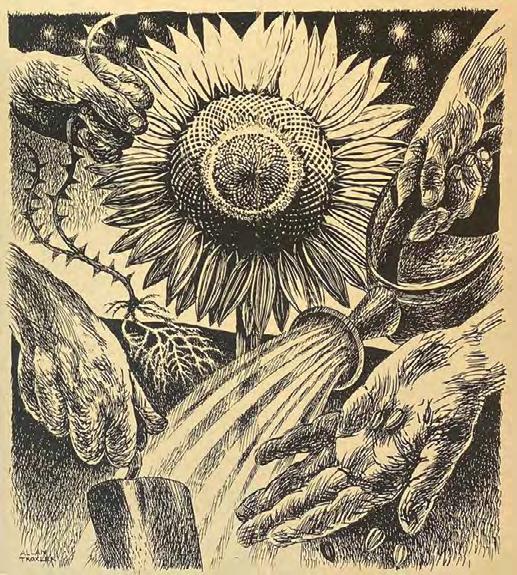

On October 26, the Durham artist Allan Troxler died at age 78. A trailblazer in the fight for gay rights, the legacy he leaves behind is imaginative and indelible.

BY SARAH EDWARDS sedwards@indyweek.com

Over the past two years, Pamela George and Richard Ward spent hours in a small apartment off Broad Street sorting through boxes.

The material belonged to the artist and activist Allan Troxler, and it seemed endless. There were hundreds of Easter baskets and 50 pounds of birch bark. There was a hornet’s nest. Mostly, there was art: poems and political posters, textured sketches, and intricate paper cuts. As they sorted, George and Ward—close friends of Troxler’s— slipped materials into clear plastic sleeves for submission to Duke’s Rubenstein Library.

Troxler died in Chapel Hill on October 26, 2025. He was 78.

“We couldn’t have run the Left in Durham these many decades without Allan’s creative stamp,” says George, a Durham artist. “It was ubiquitous and also understated. He never promoted himself—there’s no website, no Instagram postings, no authorship. He worked in the quiet way, behind the scenes, in the most magnificent way.”

As Troxler’s friends tell it, the longtime Durham resident was a brilliant and undersung artist, a generous iconoclast who made and gave so freely that it is only in his death that the creative dust, flung widely around the region, has begun to settle. Troxler’s work braided the personal and political, touching on his experience of being a gay man in the South while illuminating the cost of war, the urgency of protecting the environment, and the monumental pleasures of dance.

“Allan [was] just an incredible person—one of the most incredible artists and activists, I think, that Durham has had in the last 50 years,” says Hooper Schultz, a community historian and doctoral candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill. Troxler was born in 1947 in Greensboro to Eulyss and Catherine Kirkpatrick Troxler. When he was a child, the Klan left a burning cross on his family’s land outside Greensboro. His parents, who were Quaker and Methodist, were dedicated activists, and Troxler spent his early years posted up at antiwar vigils with his mother—a path he later

“Seems to me that one big difference between the revolutionary and the fascist is that one tries to understand his own heart and one doesn’t.”

followed as a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. In the early 1970s, Troxler moved to a communal farm in Wolf Creek, Oregon, and became partners with Carl Wittman, an activist known for publishing the seminal document “A Gay Manifesto.” In Wolf Creek, the couple tended the land, engaged in environmental activism, and helped launch the publication RFD—an acronym that represented, depending on the issue, Rustic Fairy Dreams, Resist Fascist Demagogues, or similar variations on a theme. It is still in circulation.

In 1979, Troxler moved back to North Carolina because he missed his family and the “longer garden seasons” of the South, as he told the author and activist Mab Segrest, a close friend. He and Wittman settled in two dilapidated houses in East Durham, with Segrest and her partner joining Troxler in his home. They took to renovating Troxler’s home, and Segrest recalls turning sledgehammers to the walls—an act that was “therapeutic, in the early Reagan years.”

Beyond blunt instruments, there was beauty, which Segrest describes as Troxler’s “main medium.” He was passionate about gardening and English and Scottish country dance. Over the years, his friends came to know him as E. Bunny, a name drawn from his long-standing tradition of buying dozens of eggs, dying them wild shades, and then making elaborate midnight deliveries of Easter baskets across the Triangle.

Whimsy, talent, beauty—all these were elements in the drive from Troxler’s friends and family to preserve his materials, but it was about more than that.

In February, the National Park Service removed references to transgender people (including Durham’s Pauli Murray) from federal websites at the directive of the Trump administration; since then, a volley of executive orders challenging cultural institutions has followed, including efforts to censor museum exhibits, challenge school curricula, and revoke library funding. Entering things into the record has always been a political act, but these days, there is an electric urgency to it.

“People my age—we understand that a generation is dying,” Segrest says. “It’s a generation that got us through all of these hard times to substantial victories that this MAGA group of folks is in the process of very effectively dismantling.”

During 2024’s Pride Month, Governor Roy Cooper hosted a reception honoring Troxler alongside fellow activist Mandy Carter. Hooper Schultz helped recommend the pair to the governor’s office.

“Although Allan and Mandy are queer people who have organized around queer rights and against homophobia, they’re also people who are deeply concerned with all kinds of human rights and environmental issues and making the world a better place for all people. It’s really important for everyday North Carolinians to see the governor’s office recognize these people,” Schultz says. “It reminds them that they are here and have been here.”

In Durham, Troxler began working for the Institute of Southern Studies and, alongside Wittman, dove back into organizing around environmental issues and gay rights. The pair were early members of the North Carolina Gay and Lesbian Health Project and helped found Our Day Out, a protest precursor to today’s Pride March that was organized, at the time, as a response to the 1981 murder of Ron Antonevich in Durham by two men who took Antonevich to be gay.

One file, in Troxler’s archives, is full of letters—typewritten on paper eggshell-thin with age—from people around the country, written in response to an LGBTQ history proposal Troxler and Segrest spearheaded.

“I encourage your efforts to discover and present our previously invisible history,” one letter from Arkansas goes. “That invisibility here in the South is a particularly strong part of our oppression.”

In late 1985, Wittman was diagnosed with AIDS. The decline was rapid; he died a month later, by way of assisted suicide. A talented writer, Wittman might have been one of the ones to chronicle the wrenching story of a decade and keep it in public memory; instead, AIDS took his life,

alongside the more than 700,000 people in the United States who have died from AIDS and HIV since 1980 and the 33 million who have died from the disease globally. Troxler became the keeper of Wittman’s archives, now also housed at Duke.

Some things changed in the years after Wittman died. Troxler saw the Durham Pride parade become annual, then mainstream; gay sex was nationally legalized in 2003 and gay marriage in 2015—events not far in the rearview mirror. He went on to have more romances; tended the gardens outside Blevins House, a group HIV and AIDS hospice home; and wrote long letters, in characteristic sloping handwriting, to friends dying from AIDS. By this past year, as Trump took office for the second time and a dangerous new wave of bigotry swept the nation, his dementia was advanced.

Kate Mitchell, Troxler’s niece, now lives in Durham but grew up in rural Western North Carolina. She remembers the reprieve, as a young queer person, of coming to visit her uncle in the Triangle. She also remembers stories her uncle told her of the early days, like one about a Duke professor marching in an early Pride parade with a bag over her head, fearing exposure.

“We may be entering an era where we’re required to take the kinds of risks that Allan was taking in the early ’80s,” Mitchell says. “It wasn’t the novelty of the celebration or the fun—it was fear, and it was making statements when you really didn’t know if that would affect your livelihood, your family. And we’re in a risky environment that’s increasingly similar.”

“People my age—we understand that a generation is dying. It’s a generation that got us through all of these hard times to substantial victories that this MAGA group of folks is in the process of very effectively dismantling.”

There’s a scene in Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding in which three characters sit in a kitchen, exchanging ideas for a better world.

In the 1946 novel—the third from McCullers, a queer Southern writer—Frankie, a restless adolescent, feels like an outsider in her small town. The two people she is closest to are John Henry, her six-year-old cousin, and Berenice Sadie Brown, a Black woman employed by the white family. John Henry’s imagined world is a “mixture of delicious and freak” with rain made of lemonade, while in Frankie’s, people can “change back and forth from boys to girls.” Berenice wants a world without wars or lynching.

Segrest often had dinner with George and Troxler—the latter perpetually late, usually with an elaborate dish in need of assembling—and one night, as they sat on the floor, Troxler cracked open McCullers’s novel.

“It’s a gorgeous book that I hadn’t really been aware of, although as soon as Allan was reading it, I just felt like, ‘I’m Frankie. I remember, this is my life,’” says Segrest. Of

the kitchen table scene, she continues: “It was this beautifully visionary sense of what the world could be if there weren’t Nazis and Klansmen in it, you know. I felt like I really connected with Allan in that way—throughout Southern literature, there’s Frankie Addams and John Henry West, there’s Scout and Dill. I felt like we were a little bit in tandem like that.”

At its best, creative work challenges what the artist David Wojnarowicz called “the preinvented world”—the restrictive blueprint of roles and rules we’re born into—and makes visible what has been hidden, allowing someone to read a passage and say, “I remember, this is my life.”

In one of the boxes at the Rubenstein, there is a folder of materials on an antiwar parade float, designed by Troxler, that was barred from a 1969 Greensboro holiday parade. The folder mostly contains newspaper clippings and photos, but there’s one sheet of notes from Troxler. He sounds frustrated: “Doing posters and handbills—reaching everyone without reaching anyone,” goes one line.

But the scribbling continues, working out a thought: “Seems to me that one big difference between the revolutionary and the fascist is that one tries to understand his own heart and one doesn’t. I’m beginning to understand now that until you can love one person unselfishly, you can’t rightly act out of some generalized love you assume you have for your fellow man.”

Thanks to the alchemy of preservation, in all its forms, there can be no doubt about whether Allan Troxler tried to understand his own heart or love others unselfishly. The archive tells the story.

“He is part of the legacy of North Carolina, part of the queer legacy, part of the artistic legacy, and part of a spiritual determination not to be mowed down by the brutal forces that we grew up in and pushed back,” says Segrest. “And now they’re coming back again. So I think he is both rich anecdotally, but he is also rich as an antidote to all the things in this culture that could destroy us.”

To celebrate the final release from his bestselling Sun Eater series, Raleigh author Christoper Ruocchio and his wife, Jenna, are holding a gala for fans all across the world.

BY SHELBI POLK arts@indyweek.com

Nearly a decade ago, Jenna was on a first date with a fellow NC State University student. Over dinner, her date shared that he’d just sold his first manuscript. Later, Jenna told her family about the date. Her brother brushed the writing news off: “Men will really say anything on their dating profiles!”

Fair enough, but this time, that suspicion wasn’t merited. Jenna’s date, Christopher Ruocchio, had indeed just sold a science fiction novel, Empire of Silence, to DAW Books. It was the first installment of what would become the Sun Eater series, the seventh and final volume of which is set to release this month. The series has since been a constant presence in the couple’s lives. As they fell in love, got married, and started a family, the series grew from a side project that sold a few dozen copies a week to the main source of the family’s income and the foundation of a new business venture, Highmatter Books.

As for Jenna’s brother? He’s now a dedicated Sun Eater reader.

The series follows Hadrian Marlowe, a young aristocrat with a penchant for melodrama and a singular relationship to time who comes of age in a far-future human society. Marlowe joins the empire’s endless war with the Cielcin, a human-eating alien race whose language has no word for “yes”—no way to agree to anything on equal footing.

Finishing Shadows upon Time, the last

book of the series, came with plenty of anticipatory grief for Christopher.

“There’s a Colosseum scene in the third book that I thought about every single day until I wrote it, and then it was gone,” Christopher says over a video call from his office. “And now, the whole story is gone, and there’s a whole bunch of emptiness in my head, which sounds sad, right?”

The completion of Shadows upon Time came at a chaotic enough time that it was nearly eclipsed by daily life. Christopher finished the book right after the Ruocchios’ second daughter was born, a month ahead of her due date. Jenna had also just broken her foot, and the couple was beginning to scale Highmatter Books, a small press dedicated to Sun Eater special editions and merch.

Jenna remembers getting the call that the last book in the series was finally done. She was sitting in a Bojangles parking lot, in one of her first postpartum outings. “It was like, OK, cool.” Jenna says. “It was really anticlimactic in a way I was not wanting it to be for him.”

Once things settled, she began scheming. What if they did something really big? Something Sun Eater fans had been specifically asking for?

The Sun Eater series has a tight-knit community of fans, who mostly connect online, and the Ruocchios say the community has been trying to get them to do something like the writer Brandon Sand-

erson’s Dragonsteel Nexus, an annual convention based on his work.

“It really is Jenna’s doing,” Christopher says, “But the idea came from my readers. They were sort of harassing us into doing a convention.”

The Ruocchios shot for a gathering somewhere in between an old-school scifi convention and a standard book signing, landing upon the Shadows upon Time Release Gala, slated for November 15 at the Union Hall in downtown Raleigh. Up to 350 people will gather for entertainment from prominent “BookTubers” (YouTubers who dedicate their channels to talking about books), food and themed drinks, a book signing, and a talk from Christopher. Tickets run from the Plus One level ($140) to standard ($200) and VIP-tier tickets ($325).

The Ruocchios know of fans flying in from all over the United States. (Christopher can name the bookseller in Texas whose passionate advocacy for the series has made the bookstore the best-performing bookstore in the country for the Sun Eater book—shout-out to Patrick!) Some fans are even traveling from Portugal.

The Sun Eater gala is a fantastical affair, but it’s not entirely unprecedented. Events like it occupy an interesting space in the science fiction world. Conventions have been enticing genre fans to travel long distances for decades, offering a sense of

community to fans of historically niche media. Worldcon, one of the longest-running conventions, has been held every year since 1939 (excepting 1942–45). Christopher himself has plenty of experience hand-selling early volumes of Sun Eater from behind a convention booth.

The increasingly mainstream appeal of genre media and the proliferation of online fan communities have made events like this more popular. Today, fans of niches within niche genres—anything from dark romance to specific gaming studios—can meet like-minded people in convention centers across the country. Authors like Brandon Sanderson and Colleen Hoover have started entire conventions for their genres.

Christopher is of two minds about the popularization of fan culture.

“It’s gotten so big, which is great for all of the creators,” he says. People can find nearly endless offerings in whatever media they like to interact with. He offers one of his favorite genres, heavy metal music, as an example of something that has become popularized and thus more accessible: “So if there’s more heavy metal, there’s a chance that there’s more of the kind that you like. It’s true to every art form, right? So for readers, for listeners, this is the best time to be alive, to have what you love in more or less infinite supply.”

Of course, there are downsides to explosions in fan culture: The more people enter Sun Eater Discord and Reddit communities, the more the Ruocchios see the kind of nasty, depersonalized comments the internet is so perfect for facilitating. And then, just because there are more books in a given subgenre doesn’t mean they’re all worth reading—“quality level might be pitchy,” he acknowledges—but even in that, there is opportunity: “You can always keep trying. And that’s cool.”

The internet was a vital part of Sun Eater’s move from passion project to family business. Christopher, an introvert who describes himself as “spiritually Bilbo Baggins,” used to regularly take time from his job at the Wake Forest office of Baen Books, a sci-fi publisher, to attend conventions. When roughly 30 Sun Eater books began selling a week, he knew he could double that at the convention.

The real change came during the pandemic, when the pair started getting more involved in their online fandom. Christopher got on YouTube to promote his work and talk about writing. He went on as many channels as he could.

“I had the sense, if I just never said no to an interview, I would start to look bigger than I was,” Christopher says. This effort paid off in a 1,000 percent boost in sales, which pushed the first Sun Eater book back into hardcover, years after it was out of print in that format—a first for the publisher.

The Ruocchios can move fluently from discussing the writing process as a vocation and art form to talking about the books as a product and experience. It’s clearly a tension they think about a lot.

There are the metaphysical and sociological questions Christopher explores in his work: issues of consciousness and continuity, a negotiation between the great man and people’s theories of history, and engagement with the shifting reading of culture and history as described in

sci-fi across time. But then there are the mechanics of making a career as a writer in the age of the internet. How do you sell a product that is, in essence, a seven-part meditation on the potential of the human condition projected over 20,000 years of materialism and technological progress? And how does an artist stay relevant and consistent enough to keep providing for their family without descending into eternal fan service?

One of those answers is to continue to cultivate a dedicated community that actually brings people together. Christopher, himself a Catholic, understands deeply the bonds formed by a shared sort of dedication, and he thinks that, while scifi conventions aren’t exactly new, events like this gala forge important connections in an increasingly atomized society.

“I think fandom fills a religion-shaped hole,” Christopher says. “There’s a real ritual element to the science fiction convention. There’s costume, and ceremony. People make pilgrimages. They come to this place, they buy these icons that they put up in their house the way the Romans would put up the house gods. Only, instead of Concordia and Ceres, it’s Harry Potter.”

He loves to see his books create a shared culture for people who might not otherwise have anything in common.

“The president of my fan club is a punk rocker, and one of the moderators is a Dominican friar,” he says. “I think that’s really cool.”

Both the friar and the punk will be special guests at the gala, and Christopher looks forward to meeting them in person.

“What do they have to talk about? At the very least, my books,” he says. “But the answer, in a deeper sense, is a lot, actually, because I don’t believe that people really, ultimately, are that different. That’s my Christianity talking, right? And it’s fun to be able to bring people together for all this stuff.”

That’s one other reason Christopher welcomes the expansion of fan culture. Having a relationship to a beloved piece of media pushes people into doing or being something—participating in the narrative and, in that sense, growing the story itself.