This policy brief is an outcome of a regional advocacy effort aimed at representing adaptation voices from the Asia-Pacific (APAC). Drawing on outreach and engagements with a wide range of stakeholders, efforts were made to gather diverse, grounded perspectives on climate adaptation challenges, gaps, and priorities.1

While there are several regional inter-governmental platforms that are working in this space and support crosscountry knowledge sharing, this advocacy efforts focused on localized and grassroots voices including local governments, community based as well as non-government organizations. Engagements with these stakeholders primarily in SouthAsia offeredcritical insights onthevaluableandcritical roleoflocal adaptation efforts in informing National Adaptation Plans (and strategies). Bridging the gap between the local and the national is critical to informing global frameworks such as the Global Goal onAdaptation (GGA) and the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). These insights are especially relevant for ensuring that the voices of the climate-vulnerable communities are integrated into the global climate agenda.

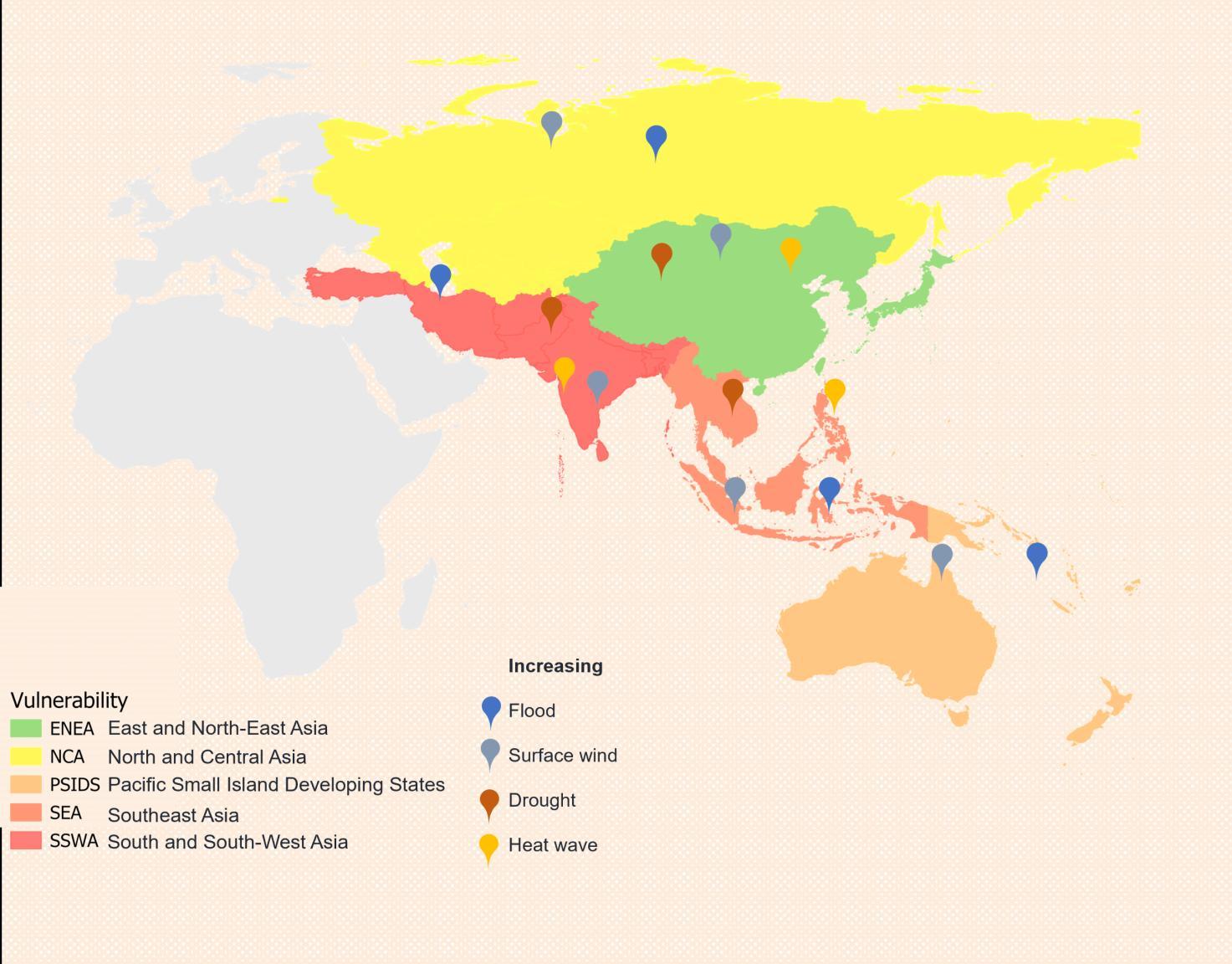

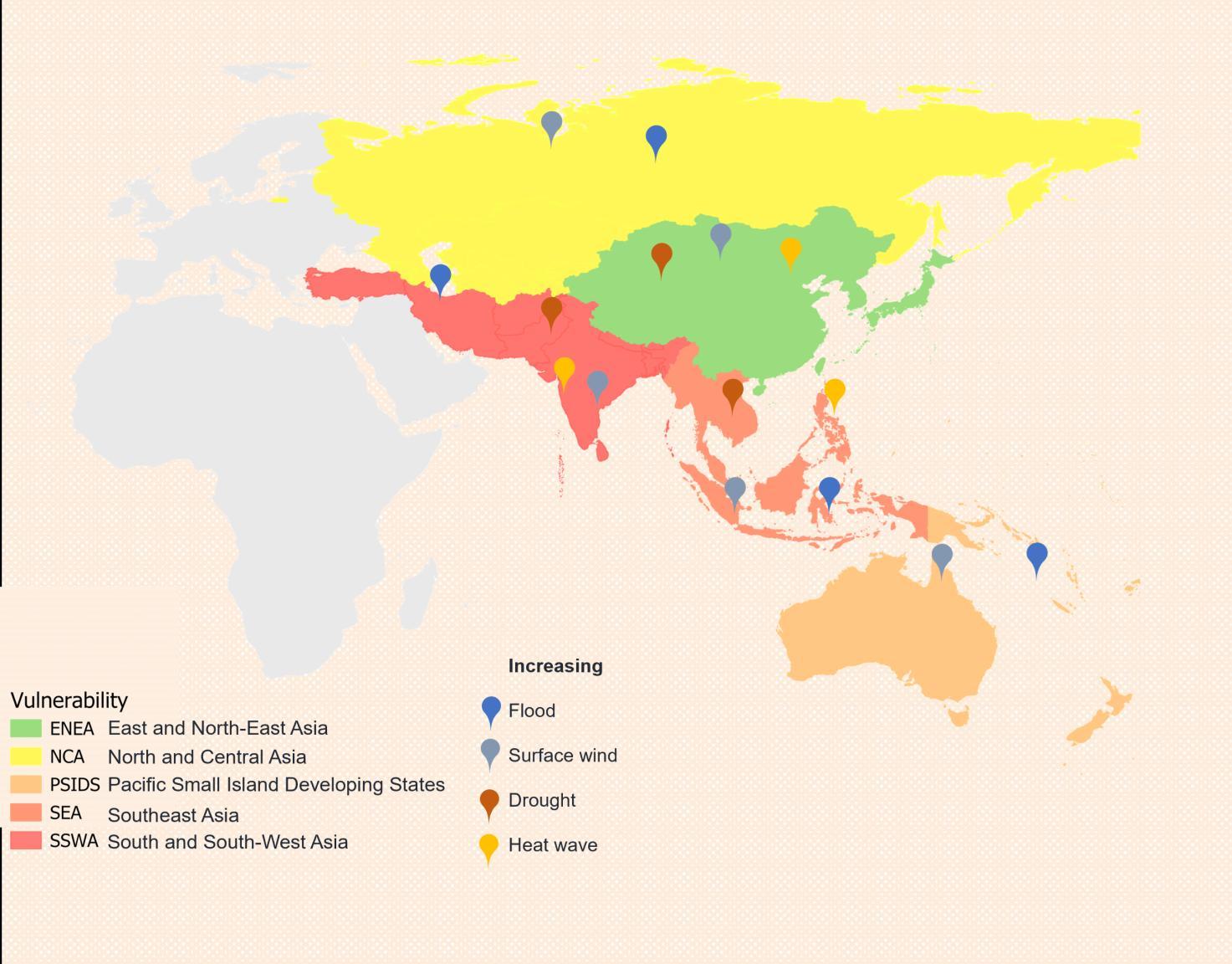

Future efforts should focus on engaging sector- and geography-specific actors, especially in vulnerable regions like SoutheastAsia and the Pacific. This requires targeted outreach and partnerships, as highlighted in the box 1.

The need for adaptation strategies targeting specific vulnerabilities and capacities of local communities were foregrounded. The disconnection between national adaptation plans (NAPs) and otherAdaptation Instruments and local needs was a recurring concern. While national frameworks provide a structure for climate action, giventhedominant top-downapproach, the planslackaccess (andby extension sensitivity)to grassroots needs, local knowledge, contextual dynamics and challenges, and local governance structures.

Stakeholders identified weak institutional linkages between national, sub-national, and local levels. Local governments and organization lack capacity, resources, and autonomy to implement adaptation strategies.This institutional vacuum restricts meaningful local participation in shaping adaptation priorities and accessing climate finance.

Local actors - especially community-based organizations and women’s groups - face major challenges in accessing climate finance. Bureaucratic procedures, lack of awareness, and insufficient documentation

1 Within theAPAC, given that the membership of theARAis largely concentrated in SouthAsia - efforts remained concentrated within this region. In contrast, the Southeast Asia & Pacific region while being highly vulnerable could not be engaged. Similarly, efforts to engage organizations working with Indigenous Communities remained limited.

capacity make it difficult for local actors to tap into funds earmarked for adaptation. Even when national finance mechanisms exist, their trickle-down to community levels remains limited.

Community-level adaptation knowledge remains largely undocumented and unrecognized in formal policy processes.There is an urgent need to develop knowledgesystems that bridge scientificdatawith local practices and experiential insights. Many countries reported a lack of local adaptation metrics and indicators aligned with global frameworks.

Inclusivity and participation-based actions emerged as critical variables shaping adaptation outcomes. Marginalized communities often remain underrepresented in climate policy dialogues. There is a demand for inclusive mechanisms to ensure these voices influence decision-making at all levels.

The advocacy revealed cross-cutting themes and challenges that varied in expression but were common across the participating countries. The disconnect between local vulnerabilities and national adaptation planning instruments were highlighted by several countries including Nepal, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The NAPs do not reflect the lived experiences of local communities and their needs. Nepal specifically emphasized the exclusion of indigenous knowledge in formal planning, while India pointed to the absence of a formal NAP and the need to harmonize state-level efforts with national frameworks. Pakistan stressed bureaucratic delays and a top-down approach that hampers implementation at local levels.

Urban vulnerability and climate-induced disasters such as flash floods and heatwaves were commonly reported. Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, for instance, flagged increasing risks from flooding, especially in urban and peri-urban areas, alongside the inadequacy of current urban infrastructure. India and Pakistan similarly raised concerns over extreme heat and water stress in rapidly urbanizing regions.

Financial challenges were widely acknowledged. Bangladesh, despite being relatively advanced in its adaptation planning, continues to face financial bottlenecks that hinder effective implementation. Pakistan and Myanmar both highlighted limited access to adaptation finance, with Myanmar’s concerns amplified by governance instability. The need for concessional, predictable, and locally accessible finance was echoed by almost all stakeholders.

Institutional and governance fragility featured prominently in feedback from Myanmar and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Myanmar suffers from outdated plans and a lack of coordinated governance, while Kurdistan stakeholders noted the absence of any substantial adaptation planning framework and called for international support and capacity-building.

Climate risks tied to geography were evident. Himalayan nations like Nepal are increasingly affected by glacier melt and related water scarcity. Coastal and deltaic countries like Bangladesh are battling sea-level rise and salinity intrusion. Island nations and vulnerable low-lying areas in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and the Pacific face multi-hazard risks including floods and cyclones.

The insights from the advocacy underscore a critical need: to recognize, institutionalize, and elevate local adaptation efforts as essential building blocks of the global climate agenda. The following recommendations aim to strengthen the linkages between local adaptation realities and national adaptation instruments (the NAP, NDC, AC) as well as global frameworks like GGA and the NCQG. These recommendations are grounded in the understanding that while climate adaptation is inherently localized, it must be supported by systems at national and international levels.

As the global climate adaptation agenda advances through the Global Goal onAdaptation (GGA) and the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), there remains a critical disconnect between international targets and the ground realities. Adaptation is inherently local - it is shaped by unique socio-ecological contexts, local knowledge, and deeply rooted practices of resilience. However, these perspectives are often overlooked in national and global policy formulations. To correct this, countries must institutionalize structured pathways for local needs and challenges to feed into national adaptation instruments such as NAPs, NDCs, andAdaptation Communications. This can be achieved by establishing continuous processes - that systematically gather local perspectives and incorporate them into national policy cycles. Furthermore, countries can demonstrate, in their UNFCCCsubmissions,theextentandnatureoflocalconsultationundertaken and adegreeofdynamism within the policy landscape

2. Reform National Adaptation Instruments and Attendant Governance Mechanisms for Local Responsiveness

National adaptation frameworks must evolve beyond top-down structures. While they provide strategic direction, they frequently fall short in addressing the diverse vulnerabilities and adaptation needs across local communities. It is essential that NAPs and NDCs are revised to integrate localized vulnerability assessments, community-prioritized sectors, and context-specific risks. This requires institutionalizing multi-level governance mechanisms that enable meaningful collaboration between national adaptation bodies and local governments. Local data, generated by municipalities and grassroots organizations, should inform national adaptation. In doing so, the instrument transforms from a static policy document to dynamic frameworks that are responsive to ground realities.

3. Bridge National, Sub-National, and Global Adaptation Efforts

Integration structure is key to achieving coherence between local action and national commitments under global frameworks. Currently, countries operate in silos, with little institutional capacity and provision to connect local-level initiatives to broader policies. Countries should therefore establish structured institutional pathways to integrate adaptation actions across governance scales. This can ensure that policy-making (specifically the national adaptation instruments) becomes inclusive, context-sensitive, and integrated - from local organization / community actions to national policies and global ambitions.

4. Strengthen Local Government Capacity

Local governments are the frontline actors in the adaptation landscape, often tasked with responding to climate impacts despite limited institutional and financial capacity. Empowering them to take the lead in adaptation planning and implementation is a vital step toward building climate resilience. By shifting from top-down

governance inclusion to genuine empowerment, local and subnational governments can become strategic partners in the national adaptation initiatives.

Access to climate finance remains amongst the most significantbarriersforlocaladaptationactors.Althoughglobal mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and Adaptation Fund exist, their structure and procedures often inhibit local access due to, on one hand, complex application processes, stringent documentation requirements, and lack of direct eligibility On the other, the capacities amongst local actors – government and non-government are limited. Specifically, around the ongoing developments on NCQG this emerges a critical concern. NCQG process should recognize finance for locally led adaptation, ensuring that those also doing the work on the ground / local level receive the necessary support.

The evolving global agenda for climate adaptationparticularly through the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) and the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) - presents a critical opportunity for countries to orient national adaptation policies in a way that is inclusive, participatory, and grounded in local realities. These global frameworks must not be seen as external compliance mechanisms but as potentials for meaningful opportunities - a chance to strengthen domestic adaptation systems and make them responsive to the local realities.

Despitebeing at theforefrontofclimateimpacts andsolutions, local governments, NGOs and community-based organizations are often overlooked in planning, policy, and financing processes associated with climate adaptation

Bridging the local-national-global gap is not only a policy imperative - it is a moral one. In a just and effective climate response, those who are first to act on adaptation must not be the last to be heard. A truly resilient and inclusive climate agenda must start from the ground up - rooted in local representations, supported by national systems, and echoed in global ambition.

Box 1: Sector- and Geography-specific partnerships for deep conversations

To integrate ground realities into climate adaptation agendas, a webinar titled “Recognizing Basic Infrastructure as a Pillar of Climate Change Adaptation” wasco-hostedwith BORDASouthAsia.Thesessionbroughttogether municipal representatives working on WaSH from Leh (India) and Sylhet (Bangladesh), highlightinghowsmallandmediumurbancentres - despite being highly exposed to climate extremes - remain marginal in national climate planningandfinancingframeworks.

Panelists and participants emphasized that municipalities are grappling with a range of challenges including flash floods, water scarcity, and damage to essential services like sanitation and waste management. Despite these risks, they remain institutionally overlooked and underfunded, with adaptation support heavily skewed toward metropolitan cities. For example, while Bengaluru received substantial attention during the 2023–2024 drought, the nearby Chintamani town of faced similar risks with far less visibility and support. The need for intergovernmental coordination - between local, subnational,andnationallevels-toaddressthese disparitiesisanemergingimperative.

The lack of targeted finance and governance mechanisms to support municipalities in addressing sector-specific risks is evident. For instance, Sylhet’s flood management efforts and Leh’s decentralized wastewater initiatives were shared as examples of context-driven adaptation requiringplace-basedsolutions.Mechanismslike City Business and Citizen Councils, and the developmentofawhitepaperdocumentingsmalltown climate vulnerabilities and needs were proposedastoolstoimprovevisibilityandpolicy influence.

This engagement format demonstrated that targeted, sector-specific dialogues can reveal locally grounded insights and proven practices, and recommendations often overlooked in broader forums. Embedding these in future advocacy can make adaptation policies more inclusiveandgroundedinrealcommunityneeds.