Includem’s ADAPT project - funded through the Scottish Government’s Whole Family Wellbeing Fund - launched in 2023. The ADAPT Project focusses on young people who are in conflict with the law, and young people who are at risk of being in conflict with the law. Within this area the project has a broad scope, from early intervention to young people who have committed high-tier offences. Includem’s ADAPT project is currently carrying out a scoping exercise across Scotland in order to understand the reality of young people who are in conflict with the law. A significant part of ADAPT is the funding and creation of pilot projects across the country. These projects are co-designed with third parties and are focussed on ‘filling the gaps’ in current provisions. The project has established pilots in a range of areas, from Restorative justice to Structured Deferred Sentencing with more pilot projects planned for 2024 in education, detached youth work, peer mentoring, and more.

Dr. David Gould completed his PhD in 2022 from the University of Leeds. After previously volunteering for children’s charities and with lived experience of many of the issues facing children and young people, Dr. Gould joined includem as Research Associate for the ADAPT projet in 2023. Dr. Gould is currently researching projects relating to education, justice, detached youth work, child poverty, and children’s rights.

Our Mission

To provide the support children and young people need to make positive changes in their lives, and inspire a more hopeful future for children, young people, their families and communities.

Our Vision

A world where every child and young person is respected, valued, and has the opportunity to actively participate in all aspects of life and society.

We work closely with children, young people, and their families, who are facing difficult challenges in their lives. Our trust-based, inclusive model of support is centred on the needs of each young person. We help children and young people make positive life choices and empower them to transform their lives, creating better outcomes for young people and their communities.

• includem conducted a series of interviews with Local Authorities across Scotland. Of the 18 contacted, 11 offered to participate.

• Only one Local Authority does not use Movement Restriction Conditions (MRCs). This is because they refer young people to a wraparound support service that includes Intensive Family Support Services, Functional Family Therapy, and access to a forensic psychologist.

• All of the remining Local Authorities make use of MRCs.

• No Local Authority has MRC-specific support available to young people: Support for young people on an MRC depends on the availability of current support services. This can range from a 9-5 service to 24/7 intensive support. No Local Authority has a dedicated phoneline or response service for MRC non-compliance.

• MRCs alone are ineffective: Over half [6/11] of Local Authorities reported that MRCs alone are ineffective. MRCs need to be accompanied with an intensive support service.

• Mixed response to the use of tags: Some Local Authorities reported that the use of a tag can have a positive effect for the young person, but equally some Local Authorities reported that an MRC violates a young person’s rights and can inhibit a young person’s rehabilitation.

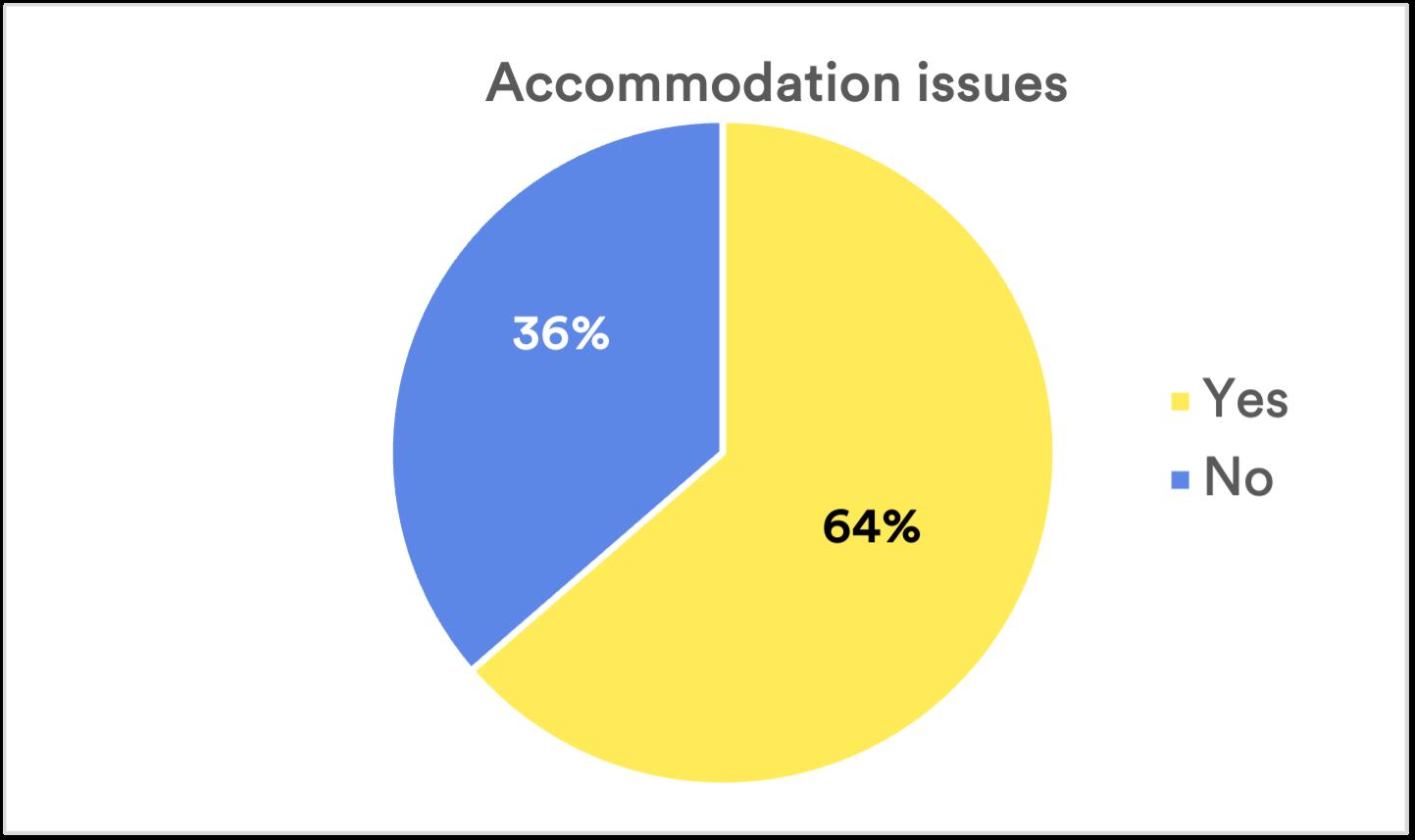

• Accommodation: Several [7/11] Local Authorities reported issues with finding accommodation. These issues include a shortage of availability in residential care, problems in the family home, residential policies that exclude young people with certain offences, and a lack of tenancy support.

• Technology: Over a third [5/11] of Local Authorities reported that technological issues also effect the use of MRCs. The radio frequency technology of tags is often incompatible with certain types of accommodation. Also, access to a consistent power supply is not always possible for families living in poverty.

• Rural specific issues: Rural Local Authorities face many challenges relating to access and transport. This not only impacts the young person’s ability to comply with an MRC but adds a lot of extra cost to support services.

• Children’s Panel, social work, and risk: The Children’s Panel and social work vary in their aversion to risk. Some Local Authorities reported that the Children’s Panel are very risk averse and prefer to use secure care. The reasons for this range from the Children’s Panel’s unfamiliarity with the MRC process to the availability of resources.

• New bill adding pressure: All Local Authorities expect to see an increase in pressure on support services with the implementation of the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill. Only one Local Authority is not expecting to see an increase in the number of MRCs issued/ recommended.

• Increase in use of secure care: Over a third [4/11] of Local Authorities reported that they expect to see an increase in the use of secure care. This is because of the lack of familiarity that the Children’s Panel will have with the new bill, and the lack of resources and services to effectively implement MRCs.

• Public Perception: Over a third [4/11] of Local Authorities noted their concern for the public perception of the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill. They noted that work needs to be done to raise awareness about the content of the bill and what the bill means for young people in Scotland.

• Children’s human rights: The above findings need to be understood in the context of children’s human rights, especially in light of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Act 2024 being given royal assent. The patch-work nature of MRC support in Scotland means that there are young people being deprived of their liberty for no other reason than a lack of resourcing.

As part of the survey, we asked Local Authorities what an effective MRC-specific support service looks like. Below is a summary overview of what they said:

• MRC-support needs to be comprehensive and holistic. It needs to consider a young person’s health, relationships, and well-being. It also needs to be flexible with 24/7, 365 availability.

• The support needs to be trauma-informed, person-centred, and accommodating to a diverse range of needs. This includes making sure that support staff are given specific training that relates to trauma, neurodiversity, offending behaviour, and so on.

• Effective MRC support is focussed on long-term solutions and sustainability. A young person’s life extends beyond their MRC.

• The family needs to be involved in the support service. Engaging the family is crucial for the success of the young person.

• The support should connect young people with partner agencies, and with the wider community. This can enable improved relationship building and provide positive, rehabilitative experiences.

• There needs to be a 24/7 phone line dedicated to MRC related calls.

• Support staff need to be located in an area that makes an in-person response reliable.

Intensive Support and Monitoring Services (ISMS) were first introduced in Scotland in April 2005. Seven Local Authorities took part in phase 1 of the introduction. During phase 1, includem commissioned a two-year evaluation of its Intensive Support Services (ISS) in five out of the seven Local Authorities. Some young people referred to includem had a Movement Restriction Condition (MRC), and some did not. John Boyle’s 2008 report on the evaluation argued that there are several major factors that need to be in place for ISMS to be successful. These factors are as follows:

1. A Programme Manager needs to be in place quickly to drive the programme forward. [They] should assemble and be supported by a core ISMS Team.

2. There needs to be high level management support for the programme within the Local Authority (LA).

3. Effective partnership arrangements need to be built early on, especially involving Education, Social Work, external providers and others as appropriate. The different agencies and workers need to be aware of their and other’s roles and responsibilities.

4. There needs to be a supply of suitable accommodation for young people in an area. The lack of this in some areas has been a significant problem.

5. The programme needs to be marketed effectively, especially to the Police, the Courts and the Children’s Hearings System so that the disposals will actually be used. Its profile also needs raised in the wider community so that people are aware of it and what it is intended to do.

6. There needs to be an effective link-up with secure care providers to ensure that those young people in secure care are assessed for ISMS and that work (such as assessment work) is not being duplicated.

7. The case conference approach to assessment seems to be the best way in which to gather all of the opinions of the professional staff involved in a case and discuss and debate the issues surrounding a young person and their needs.

8. There needs to be flexibility in programme construction and delivery so that the needs of different types of young people are met.1

Boyle’s assessment of the ISMS evaluation also makes clear that the most effective element of an ISMS is not the MRC, but the intensive support.2 There were no significant differences in outcomes for young people on ISMS and young people on ISS, except for anger management which showed worse outcomes for young people on ISMS. Young people’s attitudes towards offending also showed no significant differences between ISMS and ISS. These findings were echoed in a smaller Glasgow focussed evaluation conducted by Nina Vaswani in 2009.3

In 2013, David Orr revisited the question of MRCs for young people in Scotland.4 Like the previously mentioned studies, Orr found that the most effective element of ISMS is the intensive support. Drawing from several other studies, Orr shows that electronic monitoring alone has little to no impact on improving pro-social behaviours and diverting individuals away from offending behaviour. According to Orr, “in the absence of such support the case for EM [electronic monitoring] becomes weak (if not indefensible) from the perspective of those committed to the principle of rehabilitation.”

With this in mind, Orr’s research also found that access to support services varied across the county. Some Local Authorities used solely inhouse support services, while others had partnership arrangements with third sector organisations. The range and intensiveness of support also varied between Local Authorities. For example, very few Local Authorities offered support for accommodation. The lack of available support for accommodation conflicts with Boyles original list of major factors for the success of ISMS. The reasons for this lack of support could relate to Orr’s findings “that intensive services for young people have recently been subject to significant financial cuts” across several Local Authorities. Orr also found that MRC usage was unexpectedly low in Scotland. The main reasons for this included infrequent recommendations for MRC imposition by lead professionals, decreased awareness among practitioners about the MRC option, a small number of young people meeting ‘secure criteria’, and ethical/ideological reservations among practitioners.

In line with the findings of all the previous research, Stewart Simpson and Fiona Dyer’s 2016 paper also shows that the intensive support element of ISMS is crucial for its success.5 While there were practitioners who could see some benefit to the use of electronic monitoring, the intensive support was found to be the most important element of ISMS. Echoing Orr’s research, Simpson and Dyer’s paper also showed a low usage of MRCs in Scotland. Local Authorities noted that MRCs were not recommended enough by lead professionals in their areas, attributing the limited use to a lack of knowledge and understanding of such orders. These respondents emphasised the contentious nature of MRCs among practitioners, managers, and Children’s Panel members. Some highlighted the importance of practitioner and manager ‘buy-in’ to enhance MRC usage, while others mentioned ongoing efforts within their Local Authorities to promote MRCs through in-house initiatives or the development of local guidance.

Simpson and Dyer’s papers also showed the need for both “step up” supports to prevent young people from entering secure care and ‘step down’ resources for those transitioning out. However, concerns were raised about the inadequate availability of these resources, leading to young people being placed in secure care, staying there, and facing challenging transitions due to the geographical positioning of secure care services in Scotland.

Claire Lightowler considered the question of MRCs from a rights respecting approach in 2020. Agreeing with a 2019 paper by Donna McEwan, Lightowler argues that an MRC is a tool, not a solution or punishment.6 An MRC should aim to engage and involve those supporting the child and parents in a risk reduction plan. The plan’s wider interventions should support parents and enable them to manage concerning behaviours. However, Lightowler’s argues that “the use of MRCs by the Children’s Hearing System appears to be lower than we would expect given concerns about

depriving children of their liberty, the policy preference for intensive community supports and the legal requirement that an MRC must be part of the assessment when children are being considered for secure care.” Agreeing with Simpson and Dyer, Lightowler states that “children are being deprived of their liberty when intensive community-based support, such as MRCs, are more appropriate for supporting and controlling children.”

Previous studies place a consistent emphasis on the importance of the intensive support element of ISMS in Scotland. The research consistently indicates that while MRCs can be used as part of a toolkit, their efficacy is limited compared to the positive impact of intensive support. Challenges such as low MRC usage, insufficient availability of support resources, and variations in support services across regions highlight the need for a comprehensive and rights-respecting approach. The current paper uses previous research as a foundation to return to the question of MRCs in Scotland.

Eighteen Local Authorities across Scotland were asked to participate in the research for this report. Out of the eighteen, eleven agreed to a semi-structured interview with includem between December 2023 and January 2024. The interview consisted of five core questions that were asked to every participant. Discussion was allowed to occur between each question, which often happened when more than one participant represented a Local Authority. The interviews were not recorded using an audio device as time constraints prevented a thorough transcription process after data collection had been completed. Extensive notes were taken during each interview with key details relating to the core questions being prioritised. Each interview was then coded through a thematic analysis. This analysis found 14 themes relating to MRCs in Scotland.

Over half [6/11] of Local Authorities reported that MRCs alone are ineffective. It was generally agreed that MRCs need to be accompanied with an intensive support service in order to be of value. When Local Authorities reported an MRC not working due to persistent non-compliance, the reasons for those failures were attributed to the lack of support rather than the lack of restrictions. There were a mix of responses regarding the benefits of using electronic monitoring. Some Local Authorities reported that the use of a tag can benefit the young person. For example, an electronic monitoring device can give the young person a legitimate reason to avoid potentially harmful peer pressure. Equally, some Local Authorities reported that the use of electronic monitoring violates a young person’s rights and can inhibit a young person’s rehabilitation. This inhibition arises when the restrictions imposed on the young person prevent them from pro-social activities, gaining employment, and restricting them to potentially unstable and inappropriate accommodation.

On a national scale, support for young people on MRCs in Scotland exists via a patchwork of services and resources. The availability of support can vary dramatically between Local Authorities. One Local Authority explained that they offer a robust, multiagency support service with 24/7 access to their out of hours phone line. Another reported that they only offer the standard inhouse social work support supplemented by a third-party organisation. This thirdparty organisation only covers part of the Local Authority area and only operates during business hours. What did come to light from this research is that no Local Authority offers MRC-specific support. The details of what an MRC-specific support service could look like will be detailed later in this report. Currently, even the most robust support services offered by Local Authorities in Scotland are not designed to meet the specific needs of a young person on an MRC.

MRCs require a young person to have an address to which their electronic monitoring device is attached to. The conditions imposed by an MRC will expect the young person to be at this address during their curfew hours. However, several [7/11] Local Authorities reported issues with finding accommodation. One such issue is the dynamic in the family home. For a range of reasons, the family home is sometimes not the best place for a young person to be, especially if they are confined by the conditions imposed by their MRC. It can be the case that a young person is engaging in offending behaviour because of the dynamic of their family home. Equally, parents can struggle to manage the behaviour of their child on their own. One Local Authority described an MRC that on paper seemed to be working, but after speaking with the family it transpired that the young person was exhibiting aggressive and violent behaviour within the home during their curfew. Sometimes alternatives to the family home are in the young person’s and the family’s best interests, but Local Authorities also reported issues here.

One issue was the availability of spaces in residential care. One participant reported that there were only five residential care beds across the entire Local Authority. The lack of available spaces can prevent an MRC from being considered. Another issue relating to residential care is the way that policies can exclude young people with certain offences. For example, one Local Authority reported that a residential unit refused to accept anyone with an offence relating to sexual behaviour. Finally, one Local Authority reported that there was a lack of tenancy support for young people. They found that they could sometimes find private accommodation for a young person, but they could not offer tenancy support to help with rent payments, setting up utilities, council tax, etc. This meant that the young person was given even more stress to deal with while also trying to conform to the conditions of the MRC.

G4S are currently contracted to supply the electronic monitoring of MRCs in Scotland. The tags provided by G4S use radio frequency technology. While this technology can be used successfully and without issues for many MRCs, over a third [5/11] of Local Authorities reported that they experienced consistent technological issues. Radio frequency tags are often incompatible with

certain types of accommodation, such as large town houses and residential care units. It is standard procedure to use a single monitoring unit per property. With larger properties, a single unit cannot cover the entire building. One Local Authority reported that the only workaround for this issue confines a young person to a single room during their curfew hours. It was speculated that the use of two monitoring units could solve this issue, but so far G4S maintains that their policy is to install one unit per property. With young people living in residential care or in town houses, technological limits can make the use of an MRC impossible.

Another issue relating to technology is a household’s access to a consistent power supply. Families living in poverty can struggle to keep on top of their prepaid electric meters leading to temporary power outages. The radio frequency technology of the tags relies on a constant power supply, and outages are registered as a breach of MRC conditions. In a similar vein, Local Authorities reported frequent glitches and false alarms being raised. Examples of situations that set off false alarms range from walking into the garden for a cigarette to sitting in a bathtub. These examples show that even mundane activities can cause a lot of unnecessary stress for a young person who is doing their best to comply with an MRC.

Rural Local Authorities face many challenges relating to access and transport. One rural Local Authority told includem that they have a partnership agreement with a third sector organisation who provides part of the support package. However, this third sector organisation only offer support in two more urban areas, which leaves the majority of the Local Authority without support. Even if the third sector organisation covered the entire area, this rural Local Authority faces many challenges with the reliability of transport links. During the winter, roads are at risk of closure and train services can face severe disruption. The unreliability of transport links and the size of rural Local Authority areas makes it difficult to sufficiently support a young person on an MRC.

There are ways of offering a more reliable service in rural areas. One Local Authority described an on-call ambulance service that operates from a staff member’s home address. Having a service that is available locally increases the service coverage and provides local residents with a high level of confidence that they can receive help when they need it. Another Local Authority talked about how local young people are very comfortable with using digital technologies, such as video calls, to receive support. It was mentioned that since the pandemic young people have embraced these new technologies.

The situation described above not only impacts the young person’s rehabilitation and their ability to comply with an MRC, but it also adds a lot of extra cost to support services. One Local Authority described transporting young people from secure care to a court hearing. The process was extremely labour intensive and expensive. It was estimated that it costs £6,000 to transport two young people to and from their court hearing. Additional costs such as transport and rearranging hearings due to road closures need to be factored into the cost of using secure care.

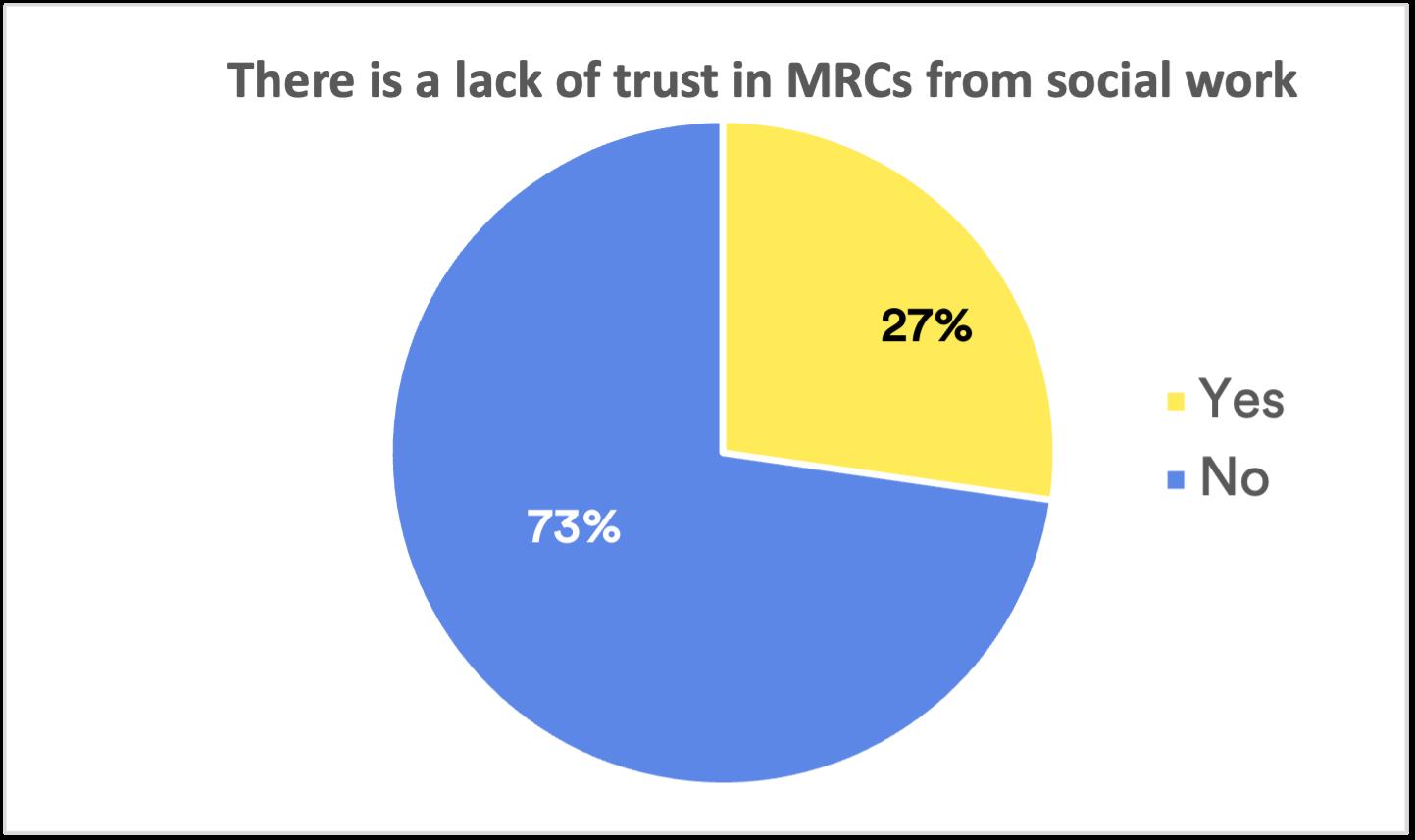

Local Authorities reported that the Children’s Panel and social workers vary in their aversion to risk. It should be noted that the Children’s Panel were not contacted for this report, and what follows only considers the perspective of the Local Authorities that spoke to includem. Some Local Authorities reported that the Children’s Panel are very risk averse and prefer to use secure care. The reasons for this range from the Children’s Panel’s unfamiliarity with the MRC process to the availability of resources. Some Local Authorities reported that the Children’s Panel seemed not to understand the criteria for an MRC, how an MRC works, and the purpose of an MRC. The movement toward professionalising the Children’s Panel was spoken about with mixed opinions. Some Local Authorities welcomed the idea of having a professional Children’s Panel, while others were sceptical about how long such a process would take. For the Local Authorities who attributed low MRC uptake to a lack of understanding from the Children’s Panel, a common theme was that more training was needed to improve understanding.

In a similar vein, it was reported that the Children’s Panel sometimes do not recommend an MRC due to a lack of available resources. An MRC always comes with a question of how well a young person can be managed and supported in the community. If the resources are not clearly available, or if the Children’s Panel are unfamiliar with the MRC process, they will often prefer to use secure care. Some Local Authorities reported that social work professionals also share this attitude. A lack of familiarity and a lack of available resources will see the use of secure care recommended over the use of an MRC. Again, this section did not account for the perspective of the Children’s Panel. Future reports should consider speaking with Children’s Panels across different regions to gain their insights into the youth justice system in Scotland.

While all Local Authorities expressed their approval and enthusiasm for the Children (Care and Justice)(Scotland) Bill, they also reported that they expect to see an increase in pressure on support services. This increase in pressure is expected to be felt across all aspects of children’s services. Only one Local Authority is not expecting to see an increase in the number of MRCs issued/recommended, but they are expecting an increase in services in general. As it stands, no Local Authority has an MRC-specific support service, and so any increase in MRC recommendations will need to draw from the services that are currently available. There is a risk of a feedback loop where services are being stretched beyond capacity, which leads to young people going on to be in conflict with the law, which could then lead to an increase in MRC recommendations, which then adds further pressure services that are already beyond capacity. One Local Authority made explicit that young people on MRCs were already known to children’s services and being supported using the same services that they were using before the MRC. This rise in demand needs to be considered in the context of unprecedented budget cuts to Local Authorities which will contribute to the depletion of support services.

Over a third [4/11] of Local Authorities reported that they expect to see an increase in the use of secure care. This relates to the lack of familiarity that the Children’s Panel will have with the new bill, and the lack of resources and services to effectively implement MRCs. There was an expectation that because a recommendation to secure care might be easier to make, the Children’s Panel and social work might lean on secure care as a failsafe if an MRC appears too risky. One Local Authority pointed out that one undesirable outcome of this is that young people in their late teens could be housed with young people who are as young as thirteen years old. While in theory the interactions between young people could be managed in secure care, the reality of bed availability, staffing, cost, and resource demand should raise serious concerns. The increased use of secure care not only has an effect on young people, but also impacts Local Authorities. Every bed in secure care costs over £6,000 per week in Scotland, which is significant for Local Authorities who are currently undergoing budget cuts. Not only is cost a factor, but so is bed availability. Currently there are 84 beds in secure accommodation available across Scotland. With over a third of Local Authorities reporting that they expect to see an increase in the use of secure care, the availability of beds was also mentioned as a serious concern.

Some [4/11] Local Authorities noted their concern for the public perception of the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill. They noted that work needs to be done to raise awareness about the content of the bill and what the bill means for young people in Scotland. The concerns were two-fold. The first part related to public perceptions of justice. Local Authorities reported that from the perspective of the individual who had been harmed by a young person’s actions, it could be difficult to feel vindicated when, outwardly, that young person appears to receive no consequences. There was a worry that the public might see young people who engage in violent, damaging behaviour as ‘getting away with it’. The other side of participant’s concern about public image relates to situations where an MRC fails, and a young person reoffends. The people who are seen as being the decision makers are at risk of serious public scrutiny in a time where national and local papers already promote the idea that Scotland is ‘going soft’ on crime.

The above findings need to be understood in the context of children’s human rights, especially in light of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Act 2024 being given Royal Assent. The patch-work nature of MRC support in Scotland should not simply be looked at as a question of resourcing. There is a risk of sterilising the findings of this report by framing the issues raised by Local Authorities as a resourcing problem. What should be clear from this report is that the current situation in Scotland means that some young people have more rights than others. The Scottish Government make clear in their legislation and in their guidance that MRCs should always be considered as an alternative to secure care. Under s.83(6) of The Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011, a young person may be deemed to meet the criteria for secure care when one or more of the following conditions have been met:

(a) … the child has previously absconded and is likely to abscond again and, if the child were to abscond, it is likely that the child’s physical, mental or moral welfare would be at risk … (b) … the child is likely to engage in self-harming conduct

(c) … the child is likely to cause injury to another person

A young person who meets these criteria is also eligible to be considered for an MRC. The question of whether to use secure care or an MRC is a complex question, but essentially comes down to whether a young person can be safely supported in the community.

No young person lives in a vacuum, removed from all contexts. The question of whether a young person is likely to abscond; whether their physical, mental, or moral welfare is at risk; whether a young person is likely to engage in self-harming conduct; or whether a child is likely to cause injury to another person, is a question of what support is available for that young person. A young person living in a poorly resourced rural area with unreliable transport links is much more likely to be deprived of their liberty by the state for exhibiting the exact same behaviour as a young person living in a well-resourced urban area. Equally as serious as the postcode lottery faced by young people is the inconsistency of the Children’s Panel across Scotland. The deprivation of a young person’s liberty can depend on which panel decides their fate rather than what is in the best interest for that young person. This deprivation of liberty is not a last resort for the benefit of the young person, but is something that is imposed onto the young person because they happen to be born in an area that has not been given the same resources as another area.

What we are seeing with MRCs in Scotland in not an unequal distribution of resources, but an unequal distribution of rights. Without a reliable infrastructure and a robust support system the Care and Justice Bill risks exacerbating the problems facing young people in Scotland. If we learn from what local authorities, social workers, parents, young people, researchers, the Police, and third sector organisations have been saying for over 15-years, we can do things differently.. The new Care and Justice Bill gives us a chance to fully realise the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Incorporation) (Scotland) Act 2024 for all young people in conflict with the law in Scotland.

As part of the survey, we asked Local Authorities what an effective MRC-specific support service looks like. According to their feedback, MRC-support should be not only comprehensive but also holistic. This involves consideration of various facets of a young person’s life, including their physical health, emotional well-being, and the dynamics of their relationships. Moreover, the need for flexibility was underscored, with an insistence on 24/7, 365 availability to cater to the unpredictable nature of crises that may arise.

A key aspect highlighted by the Local Authorities was the trauma-informed and person-centred nature of the support. They emphasised the importance of support staff receiving specialised training, particularly in areas such as trauma, neurodiversity, and understanding offending behaviour. This commitment to addressing diverse needs reflects a conscientious effort to ensure

that the support provided is both empathetic and effective. Furthermore, the concept of effective MRC-specific support extends beyond immediate crisis management. Local Authorities stressed the importance of focussing on long-term solutions and sustainability. Recognising that a young person’s life continues beyond the MRC, the support service should equip them with tools for ongoing success and personal development.

Family involvement emerged as a critical factor for success in the eyes of Local Authorities. They emphasised the need to actively engage families in the support process, acknowledging the familial context as a crucial component of a young person’s overall well-being and rehabilitation. Additionally, participants spoke of the significance of connectivity in MRC support. Effective support should not operate in isolation but should connect young people with partner agencies and the wider community. This connectivity was seen by participants as a means to foster improved relationships and provide positive, rehabilitative experiences outside the immediate MRC context.

Practical considerations were also addressed, with the suggestion of establishing a dedicated 24/7 phone line for MRC-related calls. This communication channel is deemed essential for immediate access to assistance during critical moments. Moreover, the strategic placement of support staff in locations that ensure reliable in-person responses underscores the importance of a prompt and physically present support system. Local Authorities also mentioned that they would welcome support in the initial stages of setting up an MRC. Working with the young person to explain the process, connecting them with partner agencies, and establishing a working relationship early on would enable social work and the Children’s Panel to have more trust in the MRC process.

The findings of this report shed light on the complexities surrounding the implementation of MRCs in Scotland. While acknowledging the potential benefits of MRCs when coupled with intensive support services, the study highlights a myriad of challenges that Local Authorities encounter in effectively executing this approach.

One fundamental issue identified is the limited effectiveness of MRCs as standalone interventions. Over half of Local Authorities expressed reservations about the efficacy of MRCs alone, emphasising the need for concurrent intensive support services to maximise their impact. This resonates with the literature review, which consistently emphasised the pivotal role of intensive support in the success of ISMS. John Boyle’s 2008 evaluation, echoed by subsequent research, underscores that the crux of ISMS lies in the intensive support element rather than the specific conditions imposed by MRCs.

The availability and diversity of support services for young people on MRCs vary significantly across Local Authorities, creating a patchwork system. This aligns with David Orr’s 2016 findings that access to support services fluctuates across the country, with some Local Authorities relying solely on inhouse services and others forming partnerships with third-sector organisations. The lack of MRC-specific support services further emphasizes the need for a tailored approach, as highlighted in the literature review. Effective MRC support, as suggested by Local Authorities, should not only be comprehensive but also holistic, taking into account the diverse needs of young individuals.

Accommodation emerges as a critical challenge in MRC implementation, with issues ranging from family dynamics to limited spaces in residential care. This aligns with previous research, which emphasises the importance of suitable accommodation in the success of MRCs. The practical challenges of finding appropriate living arrangements for young individuals on MRCs, as highlighted in this report, reinforce the recommendations made by Boyle in 2008. Technological issues, such as the incompatibility of radio frequency tags with certain types of accommodation, further underscore the practical hurdles in MRC implementation. The rural-specific issues, including transport challenges and geographic isolation, echo concerns raised in the literature about the need for flexible program construction and delivery to meet the needs of different types of young people.

As Local Authorities anticipate increased pressure due to the Children (Care and Justice) (Scotland) Bill, this report underscores the importance of addressing these challenges promptly. The potential rise in the use of secure care and concerns about public perception necessitate a nuanced approach. Integrating the recommendations for MRC-specific support services, as outlined by Local Authorities, becomes crucial in navigating these challenges effectively. The report concludes that a holistic, trauma-informed, and person-centred approach, coupled with strategic support service enhancements, is essential to ensuring the success of MRCs in Scotland.

1. Boyle, J., Zuleeg, F., Patterson, K. and Quigley, S. with Tisdall, K. and Penman, M. (2008). Evaluation of Intensive Support and Monitoring Services (ISMS) within the Children’s Hearings System. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

2. Khan, F. and Hill, M. (2007). Evaluation of Includem’s Intensive Support Services. includem. Glasgow: includem.

3. Vaswani, N. (2009). Intensive Support and Monitoring Service (ISMS): ISMS and beyond….Youth Justice. Glasgow City Council: Glasgow.

4. Orr, D. (2013). Movement Restriction Conditions (MRCs) and youth justice: Learning fromthe past, challenges in the present and possibilities for the future. CYCJ. University of Strathclyde: Glasgow.

5. Dyer, F., & Simpson, S. (2016). Movement Restriction Conditions (MRCs) and Youth Justice in Scotland: Are We There Yet?. CYCJ. University of Strathclyde: Glasgow.

6. Lightowler, C. (2020). Rights Respecting? Scotland’s approach to children in conflict with the law. CYCJ. University of Strathclyde: Glasgow.

7. McEwan D. (2019). Flexibility is key - Movement Restriction Conditions. Information sheet. Glasgow: Centre for Youth and Criminal Justice.

Appendix 1: Charts Showing Data from Thematic Analysis of Interviews

If you would like to find out more about our research or our work you can contact: Unit 6000, Academy Office Park, Gower Street, Glasgow, G51 1PR 0141 427 0523