IN/BETWEEN JOURNAL

Editors: Annika Cleland-Hura

LAURA OSORIO S.

Design and layout:

LAURA OSORIO S.

Annika Cleland-Hura

journal.inbetween@gmail.com @journal.inbetween

Editors: Annika Cleland-Hura

LAURA OSORIO S.

Design and layout:

LAURA OSORIO S.

Annika Cleland-Hura

journal.inbetween@gmail.com @journal.inbetween

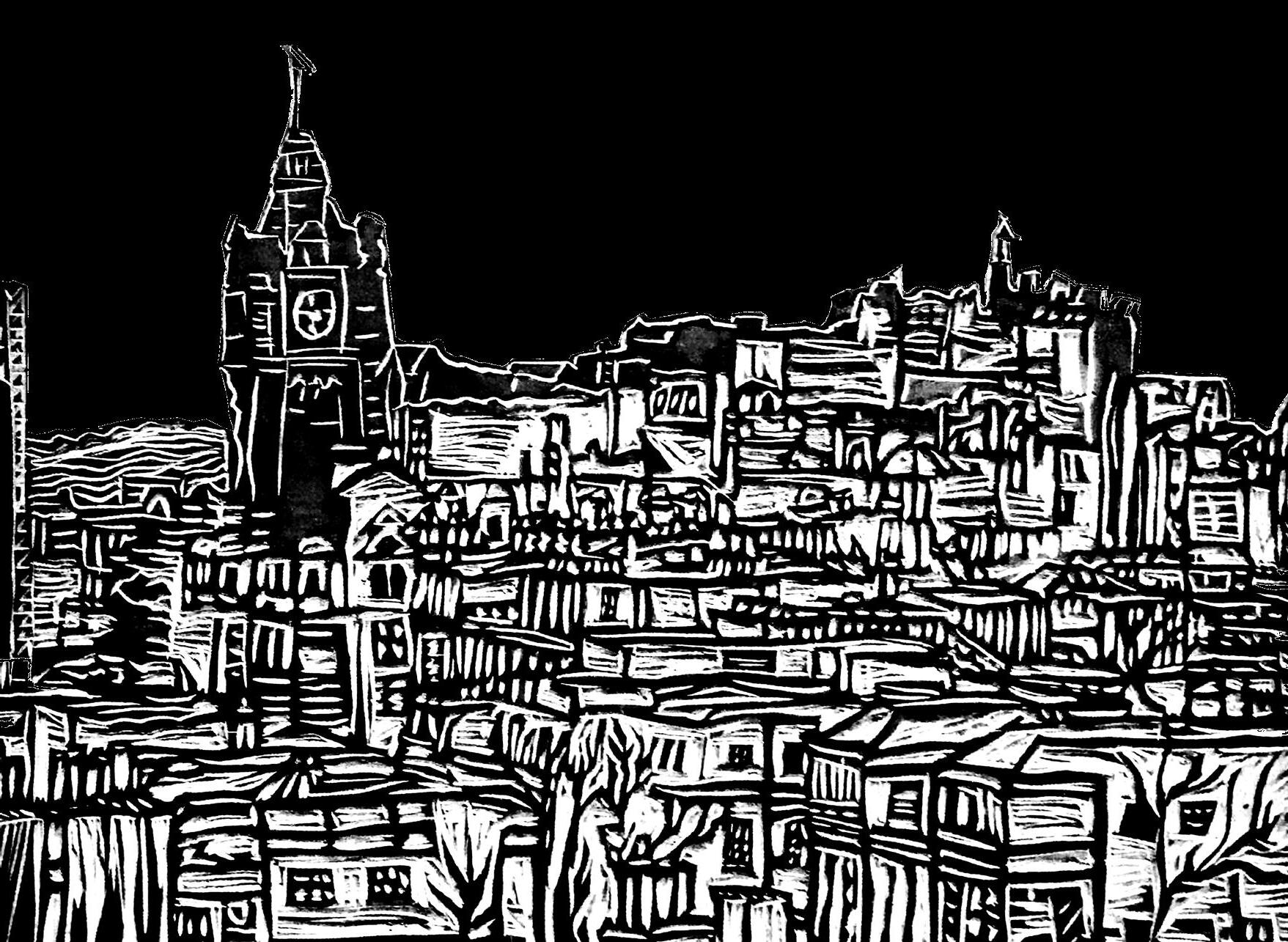

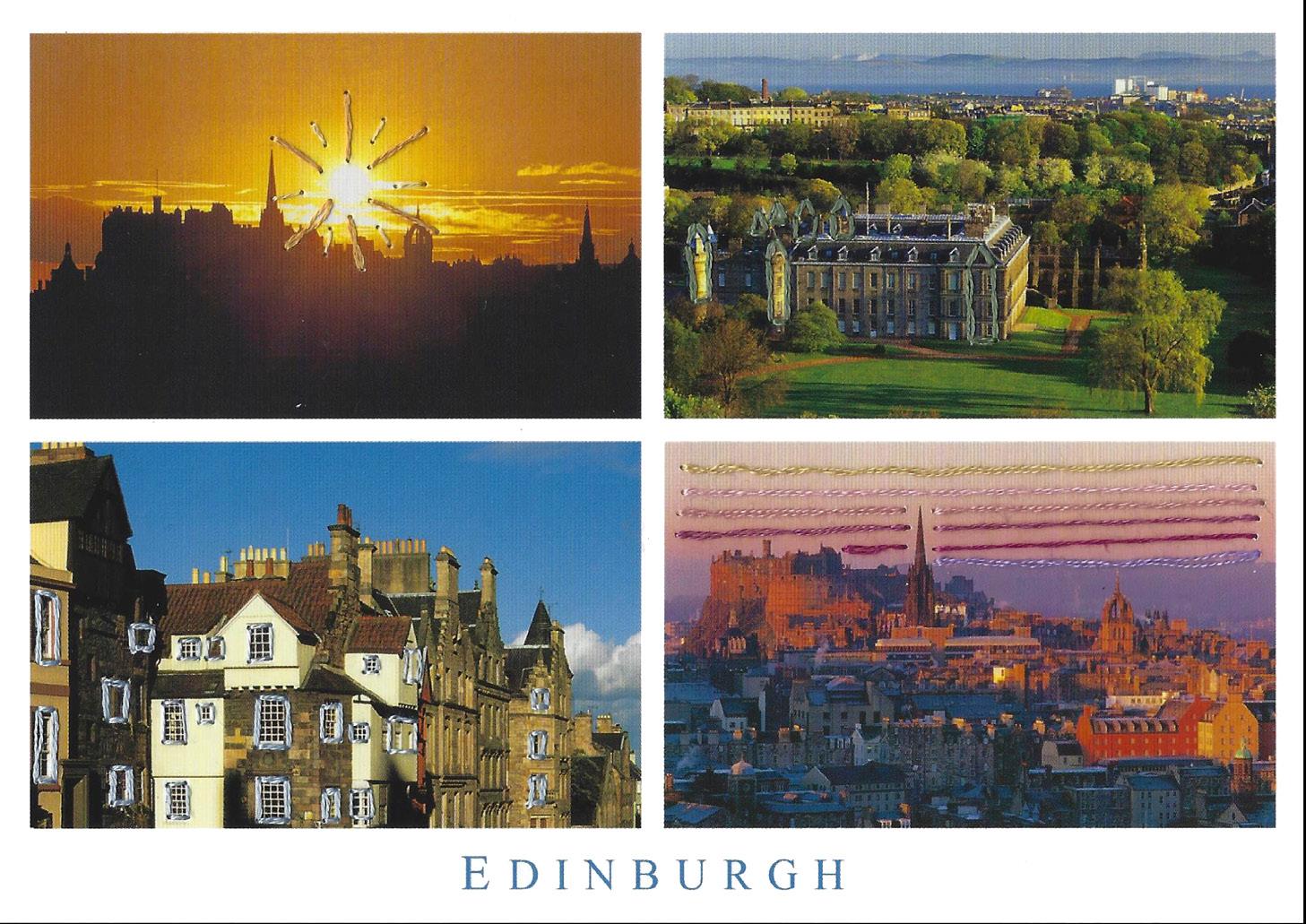

This issue explores relationships with the city of Edinburgh, which are as varied as the people who live in the city. We want to consider the city as a site of intermediality, where all kinds of media collide, collaborate, and exist in harmony and in tension. Some starting points for exploring this theme included the city’s museums, galleries, theatres, and music venues; the city’s cultural & artistic festivals; the relationships between architecture; and nature. We are especially interested in transnational and transcultural themes, engagement with history, and the evolution & fluctuation of relationships to and within the city.

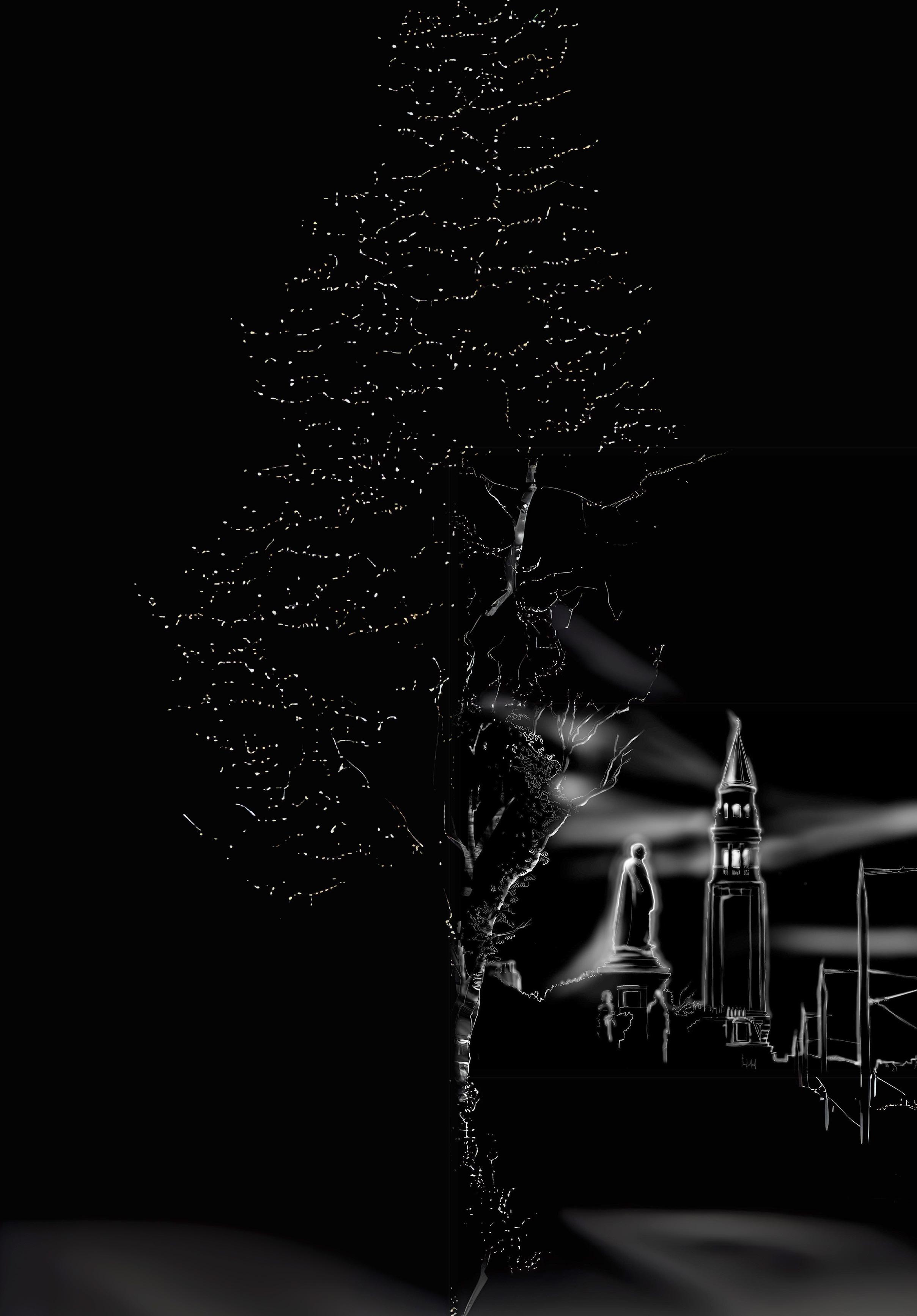

Giuliana Bruno writes in Atlas of Emotion that ‘Cities in film do not have strict walls or borders’,1 and this holds true for the cities in imagination or memories. From time to time, they take on an endless, flowing form – streaming across physical and geographic boundaries while reclaiming the ebb and tide of fresh emotions. In Bruno’s reflective journey back to her home city of Naples, the writer, as neither a local nor an immigrant but a traveler inbetween, detours and constructs new borders of identities. Bruno’s cultural meditation on “situatedness” invokes a particular emotion tied to the “traveling lens”, which interrogates cultural boundaries and ‘enables one to envision a knowledge that is situated in lived space’.2

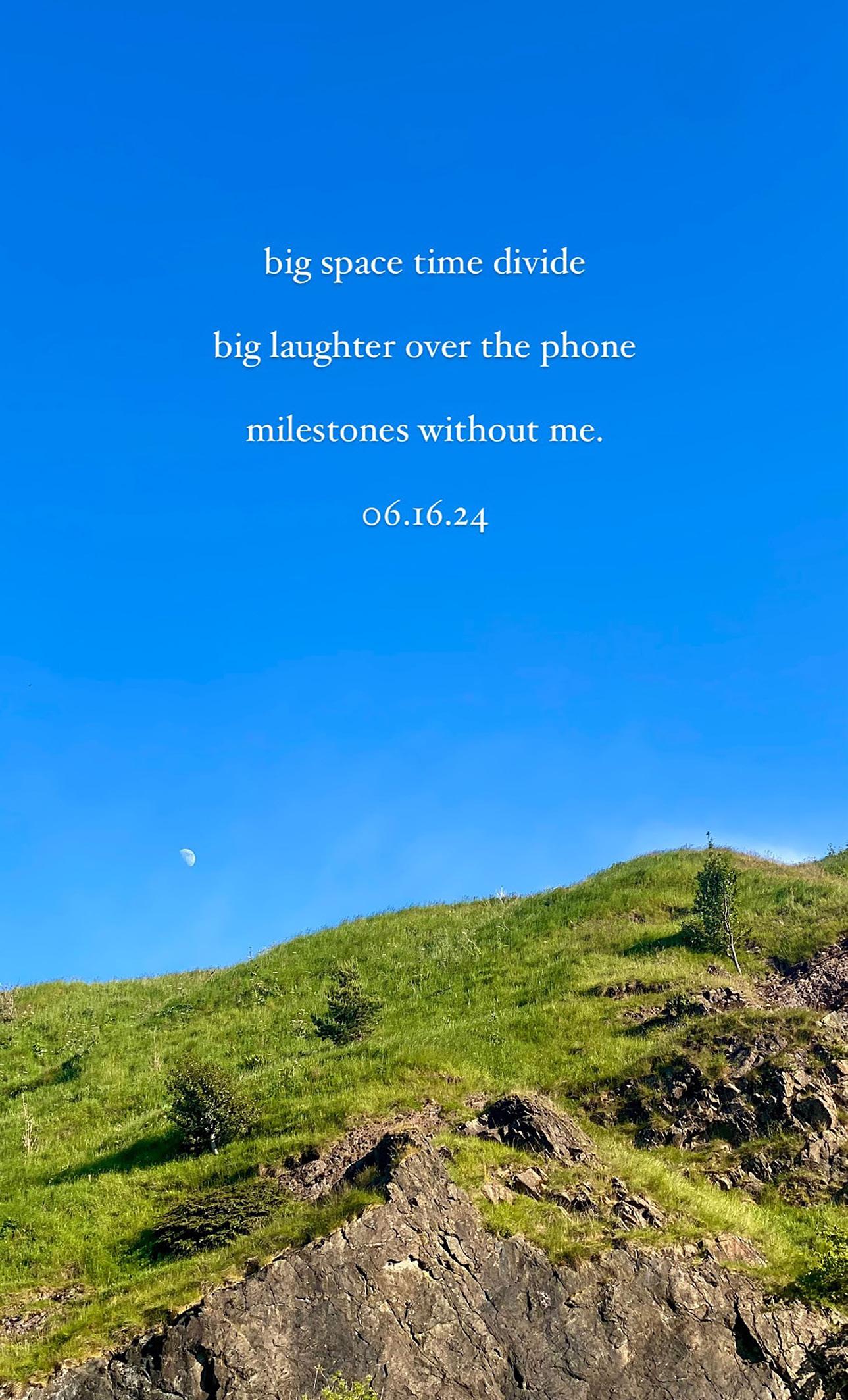

out of a certain distance, the lack of situatedness. The remoteness evokes another kind of imagination that activates my palimpsestic writing of emotions on images when I returned to my home city, Shanghai, while rediscovering my fluid identities in Edinburgh. Through this reflective creativity, a transcultural journey unfolds, leading us back to ourselves, which recalls Frantz Fanon’s words: ‘In the world in which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself’.3 This palimpsestic layering of identity and experience onto the city connects with the the “situatedness” of cinema, as Bruno points out: ‘film is a tender mapping of intimate space, Bruno tender mapping of intimate space […] that incorporates the world of affects, sexuality and the subjectivity of subjects’.4

In contrast to Bruno’s retrospective voyage with all the emotions grounded in the concrete earth and streets of her long-abandoned homeland, my own experience is

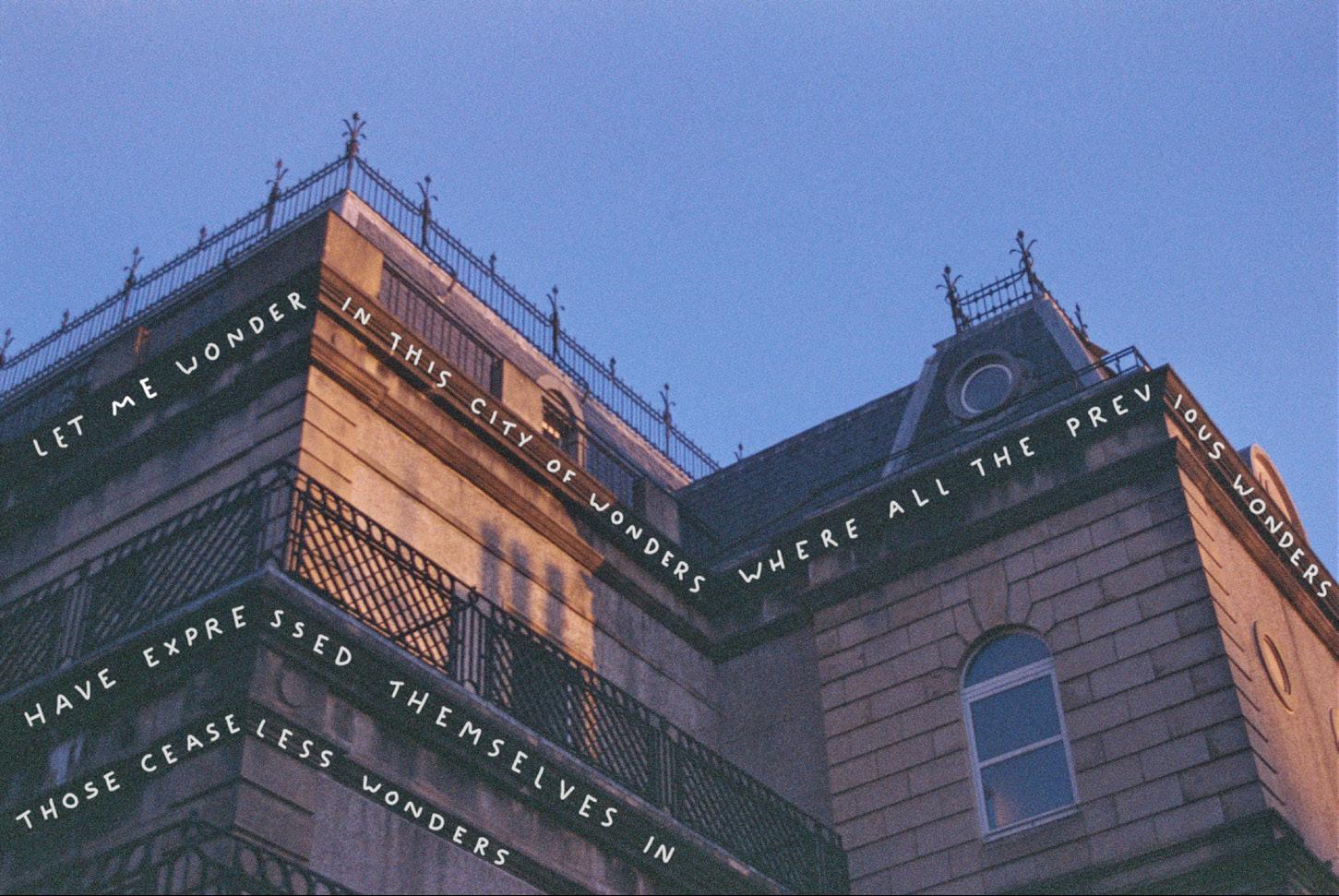

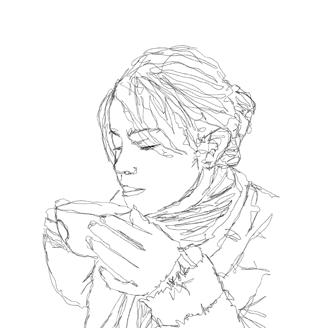

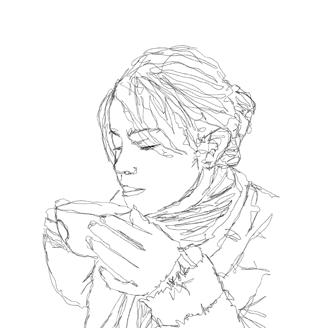

To blur the boundary between dream and reality is one reason I make my photographs into cinematic screenshots – to evoke an immediate sense of “situatedness”, allowing viewers to feel, experience, and imagine at

Deep breath, the sun-drenched scent of woods lingers along the path.

Wrapping distant mountains and soft silhouettes in my letter’s envelops.

Summer is a sleeping pill for gentle dreams, a lullaby for sweet fantasies.

the same time. Furthermore, my city wandering itself resembles an embodied cinematic experience. This traces back to the concept of the flâneur, portrayed as a rambler who maps the city through the act of looking by Charles Baudelaire. Scholar Ágnes Pethő expands this idea, depicting the flâneur as not only ‘an optical hunter’ but also as a ‘sensual stroller and observer whose physical impressions mingle with a sensitivity generated by a dreamlike state of reverie’.5 This physical walk, thus, becomes filmic, as the eyes substitute the camera lens to capture images while the

senses and consciousness infuse subjective emotions, with the legs bringing all of them in motion. Therefore, I aspire for my photos to reveal what Bruno defines as “the physical affect of (e)motion” (encompassing both one’s motion and emotion), inviting viewers to engage in the intimate experience activated by cultural travel, in which one’s fluid identities are remapped.

1. Giuliana

2.

3.

of

Journeys in Art, Architecture, and Film (New York: Verso, 2002), 361.

4.

5. Ágnes Pethö, Cinema and Intermediality: The Passion for the In- Between (Newcastleupon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 102.

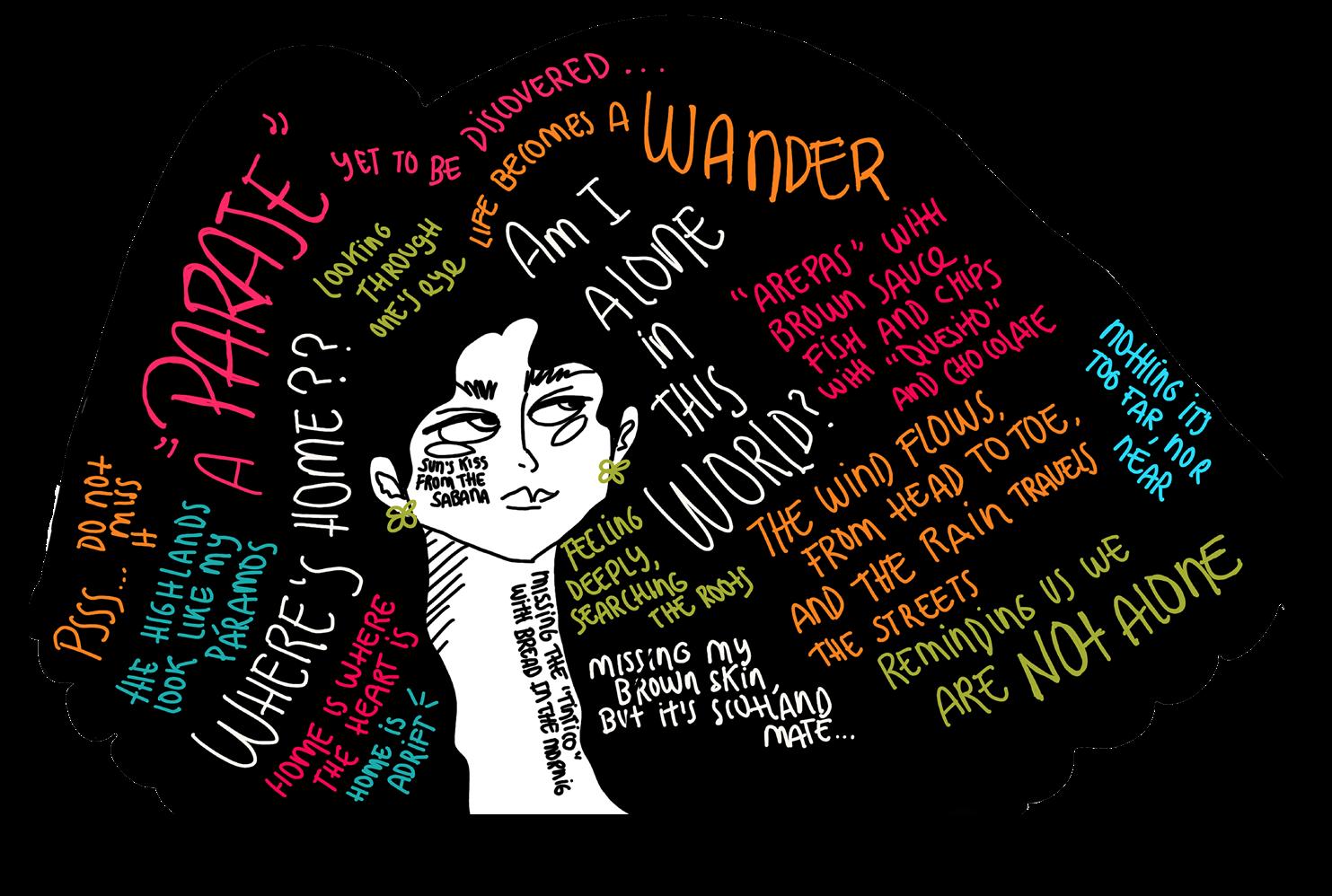

Laura Osorio S.

Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, is a city of contrasts: rooted in history yet brimming with modernity, local yet cosmopolitan, intimate yet vast and interconnected. Its cobbled streets, skyline, and diverse communities make it a metropolis of multiple meanings. As Georg Simmel observed in The Metropolis and the Mental Life (1903),1 the metropolis is not only a physical place but also a mental and social space. After all, it is there, amidst the heightened stimuli and modern life’s cacophony, that the individual’s response becomes more intellectual and less emotional. Simmel’s perspective aligns with

Marshall McLuhan’s assertion that “the medium is the message”,2 where the environment of the city –its streets, buildings, and rhythms – acts as a medium that shapes human perception and interaction. Following this idea, Simmel notes that while rural life fosters deep emotional connections through ongoing relationships, the metropolis forces the individual to confront intense and immediate stimuli, requiring responses that are

more calculated and less visceral. Films such as Trainspotting (1996), Hallam Foe (2007), One Day (2011), and Limbo (2021) explore this dynamic, capturing the city’s unique interplay of identity, belonging, and reinvention.

metropolitan life, where, as Simmel described, the individual mind must adapt to an overload of stimuli. The film captures the chaotic inner world of Renton as he runs down Princes Street, a sequence that becomes a “hot medium,” demanding the

In Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996), Edinburgh emerges as a site of existential rebellion, where the protagonists, struggling with addiction and disillusionment, embody Simmel’s concept of the “stranger” or “wanderer” – neither fully belonging to their surroundings nor themselves. Through McLuhan’s lens, Edinburgh acts as an “extension” of the protagonists, amplifying their disconnection and inner turmoil. The gritty urban landscapes of Leith, juxtaposed with the historic grandeur of the city, reflect the psychological tension of

audience’s active engagement as the visual and emotional intensity mirrors McLuhan’s idea that media environments shape human experience. The grandeur of the city and his inner turmoil collide, echoing Simmel’s assertion that the urban environment demands that the intellect dominate the raw emotions.

A further example of Edinburgh’s multi-layered identity can be found in Hallam Foe (2007), directed by David Mackenzie. This psychological drama portrays the city through the

eyes of the troubled Hallam, a young man who becomes increasingly detached from reality and struggles with emotional numbness in his search for truth and belonging. Set against Edinburgh’s iconic urban landscapes, the film explores the tension between Hallam’s inner world and the outer world he attempts to navigate. Through McLuhan’s framework, Edinburgh is not just a backdrop but an active participant in shaping Hallam’s fragmented identity. The city functions as a sensory environment – a “cool medium” in its nuanced, multifaceted portrayal – encouraging introspection and ambiguity. Echoing Simmel’s idea

of the metropolis as a space where stimuli overwhelm the individual’s capacity for emotional response, Hallam Foe explores how the vastness and complexity of the city contribute to Hallam’s feelings of alienation. His obsessive voyeurism embody Simmel’s notion of the blasé or indifferent attitude, where the overload of sensory information leads to a desensitized emotional response. Edinburgh’s contrast between intimacy and alienation provides the perfect backdrop for Hallam’s journey, illustrating McLuhan’s idea that environments act as dynamic forces shaping behavior and perception.

On the other hand, One Day (2011), based on the novel by David Nicholls, depicts Edinburgh as a city in constant flux and transience. The presence of Arthur’s Seat serves as a symbol of endurance through change, reflecting Simmel’s view of the metropolis as a place where individuals, though constantly exposed to new experiences, struggle to form lasting emotional connections. From McLuhan’s perspective, the film reflects the tactile interplay of “hot” and “cool” media. The cobbled streets and sweeping landscapes are “hot,” rich with historical density and emotional resonance. At the same time, the transient relationships and fleeting encounters are “cool,” requiring the audience to fill in gaps and engage actively. Edinburgh’s duality of

permanence and transience speaks to the complex rhythm of modern life, where relationships unfold against a backdrop of ever-changing landscapes. As Simmel argues, this dynamic provides both meaning and distance for those who navigate its streets, underscoring McLuhan’s view of the medium — the city — as shaping not only the stories told but also how they are experienced.

Similarly, Ben Sharrock’s Limbo (2020) offers a quieter, introspective view of Scotland’s multicultural identity, exploring the experiences of migrants who find themselves in liminal spaces. Although the film is set on a remote Scottish island, its themes of belonging and displacement resonate strongly with the diverse realities of the city. As Simmel suggests, individuals in the modern metropolis are exposed to a constant flow of change that dulls their emotional sensitivity, leading to a blasé attitude. For McLuhan, the city and its transient spaces –train stations, cultural festivals, and public venues – are “extensions” of human interaction, simultaneously connecting and alienating its inhabitants. This emotional numbness, a product of the constant bombardment of stimuli, mirrors the migrant’s experience of navigating Edinburgh’s ‘nonplaces’,3 spaces that, like McLuhan’s electric media, dissolve boundaries while creating new forms of disconnection and engagement.

What links these filmic representations is Edinburgh’s role as a city of edges. As a place where the boundaries between past and present, local and global, self and other are blurred, it creates dynamic environments for exploration and change. For instance, the narrow streets and dark alleys of the Old Town evoke a sense of historical weight and mystery, while the wideopen spaces of Arthur’s Seat offer a counterpoint to freedom and possibility. This duality reflects the lives of those who in habit the city –residents and tourists alike – navigating its contrasts to find their place. Through Simmel’s and McLuhan’s lenses, Edinburgh emerges as a city where the intellect and sensory systems are in constant negotiation, where the individual must adapt to the relentless stimuli of urban life, and where emotional depth is often sacrificed for calculated survival in the face of modernity’s challenges.

In this sense, the city is more than a setting for human stories – it becomes a living, breathing entity that shapes the experiences of its inhabitants. Edinburgh’s multilayered identity, shaped by history, migration, and cultural exchange, reflects both Simmel’s vision of the

metropolis as a space of constant reinvention and McLuhan’s assertion that the environment – the medium – profoundly shapes human perception and interaction. Perhaps this vibrant, complex city, where the sensory overload

of modern life meets the timeless beauty of its landscape, embodies the contradictions of metropolitan existence, offering both wonder and challenge to those who enter its folds.

1. Georg Simmel. “The Metropolis and the Mental Life.” 1903. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel, edited and translated by Kurt H. Wolff, 409–424. Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1950.

2. Marshall McLuhan. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964, p 7-8.

3. As noted by Sandra Ponzanesi (2012), this is a space “[...] where individuals function as passengers or customers or both at the same time [...] as if trapped and frozen in a time unmarked by events in the present” (p. 677). See: Sandra Ponzanesi. “The Non-

Places of Migrant Cinema in Europe.” Third Text, vol. 26, no. 6, 2012, pp. 675–90. Taylor & Francis, https://doi.org/10.10 80/09528822.2012.734565.

4. Les Roberts. “Welcome to Dreamland: From Place to Non-Place and Back Again in Pawel Pawlikowski’s Last Resort”. New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film 1, no. 2 (2002): 78–90. https://doi. org/10.1386/ncin.1.2.78.

5. Sandra Ponzanesi and Bolette Blaagaard, ‘In the Name of Europe’, Social Identities. Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture, vol 17, no 1, 2011, pp 1–10.

Hi Karl!

What are you doing on Adam Smith’s head?

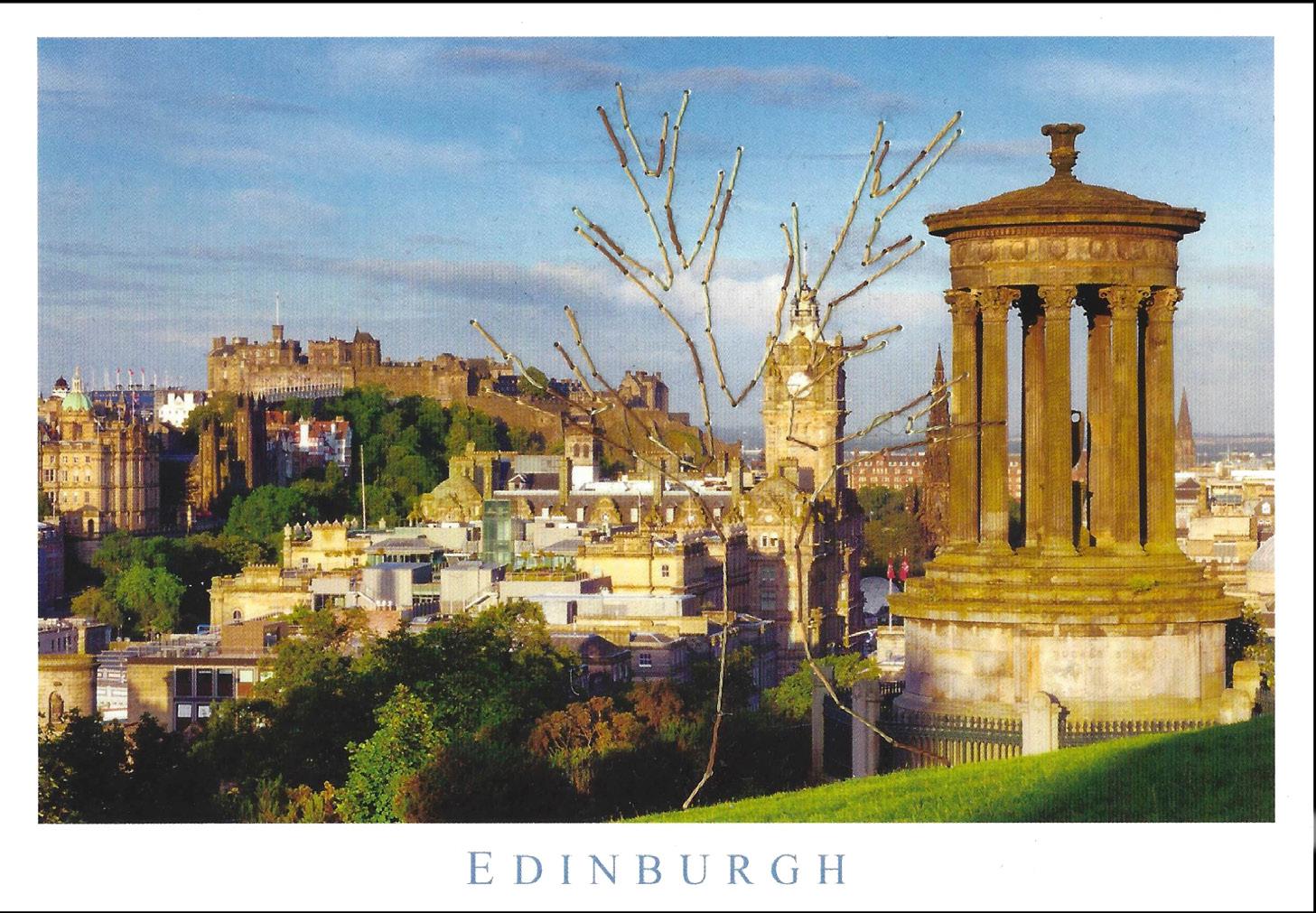

There is a kinship between Orhan Pamuk’s meditation on his home city of Istanbul and the way many Edinburgh residents talk about the city. Both places thrive on melancholy, a kind of comforting communal melancholy which Pamuk calls hüzün. In both, one can ‘“discover” the city’s soul in its ruins’ and its ‘historical accidents’.1 Perhaps the greatest similarity is the accumulation of history, folktales, national legend, and cultural heritage over centuries which both weigh down a city and its people and instil in them a sense of collective pride and identity.

Pamuk writes in Istanbul that, ‘for natives of a city, the connection [between self and city] is always mediated by memories’.2 For Pamuk, who has rarely left his home city, this mediation is relatively

uncomplicated; these memories are both individual and cultural, but they originate from the place itself. For non-natives of a city, a similar kind of mediation between self and city occurs, but the memories of the place are overlaid and coloured with memories and selves from other places.

In Edinburgh, a city much-storied and much-romanticised, the myths, expectations, and dreams of the people who visit (and often stay) also contribute to the layered mediation between the city and its inhabitants. These various impressions, visions, and memories become, to borrow a phrase from H.D., ‘superimposed on to one another like a stack of photographic negatives’ (Bid Me to Live).3 In some ways, our memories of places are like photographs, capturing

idiosyncratic angles that convey specific feelings which may or may not correspond to reality (if such a thing exists). Hervé Guibert calls photography ‘the rift, the schism between the world and its representation’ (Ghost Image).4 Memory also occupies that rift between the physical city and our imagination of it, mediating the way photography does between the world and the self.

Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that Pamuk and so many others turn to photography to help them reflect on and communicate their relationship to their urban environments; Georges Rodenbach’s photonovella Bruges-la-Morte (1892) is another such text that relies on photography and melancholy to come to terms with a city. For Susan Sontag, photography is an

epistemic tool, a way to capture and understand the world and thus relate to it. But photographs also allow us to present (and invent) perspectives that feel like truth. Photography, Sontag says, facilitates ‘instant romanticism about the present’ (On Photography).5 While tourists collect snapshots as evidence of their travels, residents of a place – especially transplants – photograph their city in an act of scaffolding, constructing support for the stories they tell about the place, their lives, and themselves. The rare photogenicity of Edinburgh cannot be accounted for through Gothic architecture, dramatic landscapes, and moody weather alone. To photograph Edinburgh is to try to understand oneself, and one another, through our relationships to the city.

1. Orhan Pamuk, Istanbul: Memories and the City (London: Faber and Faber, 2005), 231.

2. Pamuk, Istanbul, 216.

3. H.D., Bid Me to Live (London: Black Swan Books, 1983), 89.

4. Hervé Guibert, Ghost Image, trans. Robert Bononno (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 38.

5. Susan Sontag, On Photography (UK: Penguin Books, 1979), 72.

Jianing (Charlotte) Liu is a recent graduate in Intermediality Studies from the University of Edinburgh, with a research focus on cinematic intermediality, affectivity and phenomenology. She aspires to capture the interplay of imagery and emotion through writing and photography, turning fleeting moments into poetic expressions.

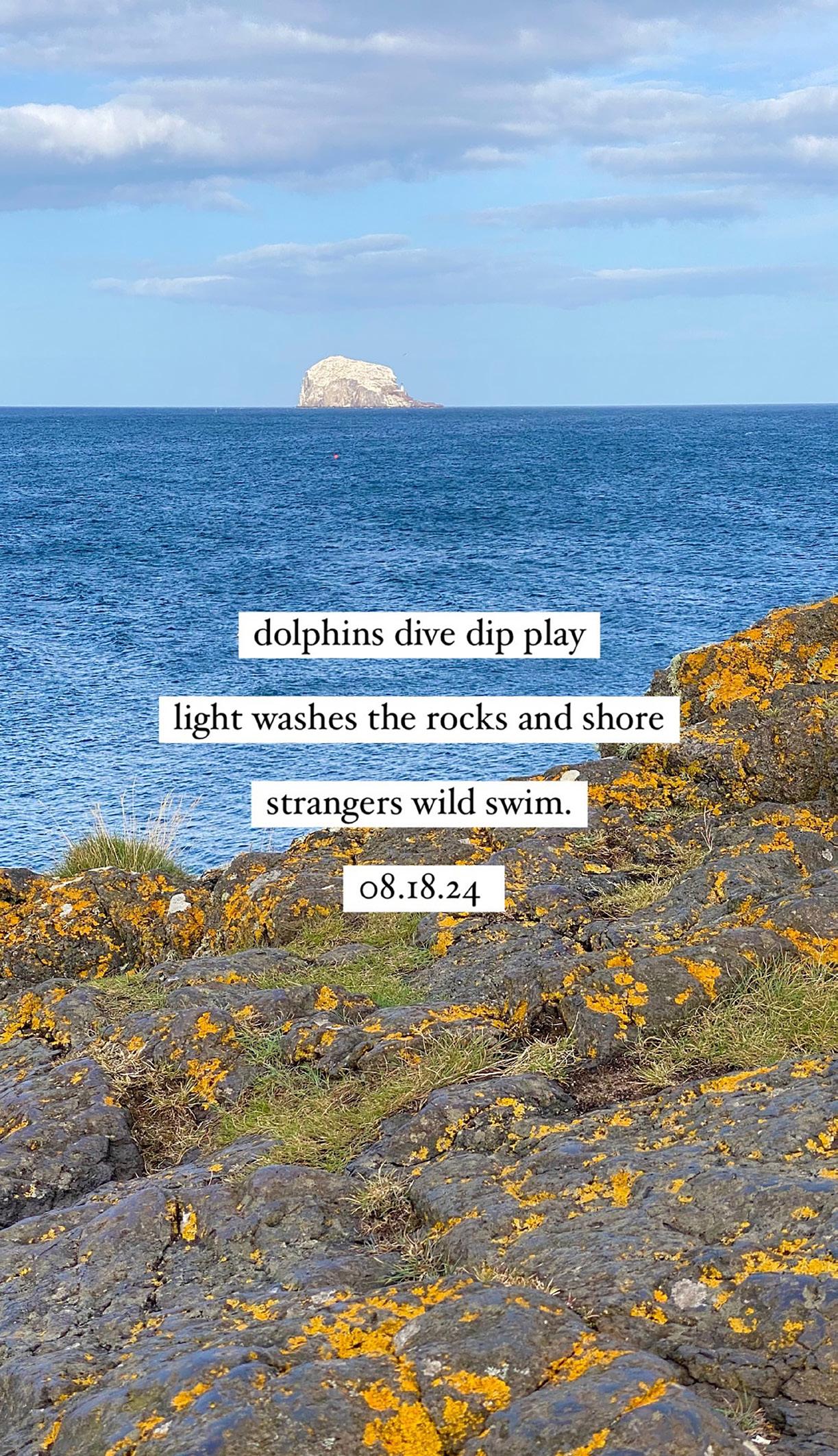

Kylie Corwin, from Long Island, is a photographer, designer, and poet based between Edinburgh, Scotland and New York, USA. Her intermedial art practice shifts between photography, poetry, drawing, graphic design, film, and printmaking, centering on environmental awareness of the body with recurring motifs of animals and plants.

Yu-Hung Tien is a Taiwanese poet doing a PhD in English and American literature at the University of Edinburgh, UK. His most recent poems, ‘My Letters to Emily Dickinson’, have appeared in the British Association for Romantic Studies: ‘Romantic Poets in the Wild’ blog post series.

Yufeng (Lincoln) Li is a PhD candidate in Film Studies at the University of Edinburgh and he is also an independent filmmaker and CG artist. With experience as a film practitioner, Li aims to integrate theory and creative practice in the study of posthumanism and contemporary cinema.

Harold Zhou holds an MSc in Intermediality from the University of Edinburgh. Interested in raccoons, TTRPGs, sarcasm, and horror stuff. Unemployed now and trying to figure out what to do next. Something exciting for sure!

Annika Cleland-Hura is a writer, poet, and intermedial artist, experimenting with a variety of analogue and tactile media to explore the intersections of philosophy, literature, and the visual arts. Their varied creative background, including classical music training, dance, and costume design, underpins their writing and visual work.

Laura Osorio Salazar is a writer and artist from Colombia who experiments with different media such as drawing and printmaking. She is interested in postcolonial studies, particularly creolisation, concerning embodiment, discursive and performative voices, and ways of being in the world beyond official narratives.

Lucy McMillan is a Scottish PhD student in Intermediality in Edinburgh. Her research focuses on how the femme fatale trope is evolving through contemporary adaptation on-screen, with a focus on intermedial theory and current cultural influences around gender and feminism.

Julia Larsen is a current PhD student in Intermediality at the University of Edinburgh. Her research examines representations of monsters in post-millennial American screen media, analyzing the relationships between monstrous bodies, sociocultural context, and the intermedial processes that influence representation.

Sirui Xu is a PhD student in Intermediality at the University of Edinburgh. Her research critically examines the biopics of artists across global cinema from 1968 onwards, analyzing how these films construct and mediate the relationship between artistic works and lived experience through the frameworks of adaptation, intermediality, and life writing theories.

Although we have articulated our general approach to intermediality in our manifesto, we would like to state more explicitly the purpose of this journal and the choices we made in bringing it into existence.

We have three aims in publishing this journal:

1. To open a free dialogue between disciplines to allow new and wide-ranging understandings of and approaches to intermediality.

2. To bring together artists and scholars of different disciplines to create a uniquely intermedial work of art and scholarship.

3. To explore alternative methods of disseminating knowledge in academia, including practice-based work and other innovative forms of scholarship.

In addition to the works it contains, the journal itself is a work of intermediality. Our hope is for each issue to be an ongoing conversation that responds to, questions, expands, and builds upon what has come before. We are interested in any and all forms of intermediality, which we think of as an exploration of “in-betweenness”, a blurring, questioning, and crossing of boundaries, and a rejection of rigid or immutable categories of medium, genre, and discipline. As such, we have chosen to place the works in this issue together in such a way that they cannot be read separately from one another. We hope that a conversation can freely flow throughout this issue and beyond, and we thank you for your part in it as readers and interpreters.

* - Jørgen Bruhn, The Intermediality of Narrative Literature: Medialities Matter (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 27.

- Rahel Jaeggi, Alienation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), 78.

- W.J.T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 94-95.

- Ágnes Pethő, Cinema and Intermediality: The Passion for the In-Between (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 1-19.

- Xanti Schawinsky, Xanti Schawinsky: Play Life Illusion. A Retrospective in Texts, Letters and Images, edited by Daniel Schawinsky and Torsten Blume (Munich: Hirmer Publishers, 2024), 132.

- Irina O. Rajewsky, ‘Intermediality, Intertextuality, and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality’, Intermédialités 6 (2005), 60.