Grade 10 • Facilitator’s Guide

English Home Language: Literature

Owned and published by Optimi, a division of Optimi Central Services (Pty) Ltd.

7 Impala Avenue, Doringkloof, Centurion, 0157 info@optimi.co.za www.optimi.co.za

© Optimi

Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of research, criticism or review as permitted in terms of the Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without prior written permission from the publisher.

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

There are instances where we have been unable to trace or contact the copyright holder. If notified, the publisher will be pleased to rectify any errors or omissions at the earliest opportunity.

Reg. No.: 2011/011959/07

English Home Language

Facilitator’s guide: Literature

Grade 10

CAPS aligned

L du Plooy A Mills W Pepler D Slabbert

PREFACE

PRESCRIBED BOOKS

Novel: The Mark by Edyth Bulbring.

Drama: Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare. (The prescribed text and study guide are complete and additional questions to test knowledge and understanding will be available online on the Optimi Learning Portal.)

Poetry: Poems from all over published by Oxford University Press.

INTRODUCTION

This is the facilitator’s guide that complements the English (Home Language) literature study guide, providing the memoranda of answers to all the exercises in the study guide. Learners must understand that to pass this section of the English curriculum it is necessary to KNOW and UNDERSTAND each of the texts so they have to study them carefully. The notes provide insights into the poet and their time, diction, imagery, themes, structure/versification, and rhetorical devices.

The exercises provide a way for you to check your knowledge and understanding. Bear in mind that, although these questions will not count towards your SBA mark, those learners who diligently complete their extension exercises are much better prepared for the tasks and tests as well as for the final examinations.

You must read the poems as many times as possible. The notes and summaries are not a substitute for reading the poems. Read poems aloud. Poets use sound devices, pace, and rhythm, and if you do not hear the poems, you cannot appreciate these techniques which enrich the experience and enhance meaning.

All literature notes are included in the readers you received as well as the study guide. These notes provide detailed analyses of the novel and poetry. Questions are set for each poem and sections of the novel. These are not only to test your understanding but are sometimes aimed at helping you to extend your insight. You will benefit from doing all the questions and motivating your answers. This develops your ability to clearly express your thoughts and opinions. Use the memoranda in the facilitator’s guide as examples of how you are expected to argue your point.

Study the Glossary of Literary Terms at the front of the book and make sure you know what they mean and how they are applied in the study of literature.

During the July and November examinations, you will write Paper 2, which covers literature.

June examination

Section A: Poetry

• Prescribed (20)

• Unseen (10)

Section B: Novel (The Mark)

• Contextual questions (25)

• Literary essay (25)

TOTAL: 80

November examination

Section A: Poetry

• Prescribed (20)

• Unseen (10)

Section B: Novel (The Mark)

• Contextual questions (25)

OR

• Literary essay (25)

Section C: Drama (Romeo and Juliet)

• Contextual question (25)

OR

• Literary essay (25)

TOTAL: 80

Week 1

YEAR PLAN

Lesson 1: ‘They flee from me’

Lesson 2: ‘The Indian burying ground’

Lesson 3: ‘London, 1802’

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 6

Week 7

Week 8

Week 9

Week 10

Lesson 4: ‘Amagoduka at Glencoe Station’

Lesson 5: The Mark: Chapter 1

Lesson 6: The Mark: Chapter 2

Lesson 7: The Mark: Chapter 3

Lesson 8: The Mark: Chapter 4

Lesson 9: The Mark: Chapter 5

Lesson 10: The Mark: Chapter 6

Lesson 11: The Mark: Chapter 7

Lesson 12: The Mark: Chapter 8

Lesson 13: The Mark: Chapter 9

Lesson 14: The Mark: Chapter 10

Lesson 15: Romeo and Juliet (Prologue/Chorus – Act 1, Scenes 1 – 2)

Lesson 16: Romeo and Juliet (Act 1, Scenes 3 – 5)

Lesson 17: Romeo and Juliet (Chorus – Act 2, Scenes 1 – 2)

Lesson 18: Romeo and Juliet (Act 2, Scenes 3 – 4)

Lesson 19: Romeo and Juliet (Act 2, Scenes 5 – 6)

TERM 2

Week 1

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 6

Lesson 20: ‘A Martian sends a postcard home’

Lesson 21: ‘Making our clowns martyrs’

Lesson 22: The Mark: Chapter 11

Lesson 23: The Mark: Chapter 12

Lesson 24: The Mark: Chapter 13

Lesson 25: The Mark: Chapter 14

Lesson 26: Romeo and Juliet (Act 3, Scenes 1 – 2)

Lesson 27: Romeo and Juliet (Act 3, Scenes 3 – 5)

Weeks 7 – 10 Revision – June examination

3

Week 1

Lesson 28: ‘Small passing’

Lesson 29: ‘What will they eat?’

Lesson 30: ‘Sedition’

Week 2

Sample

Lesson 31: ‘Sonnet 130’

Lesson 32: The Mark: Chapter 15

Week 3

Week 4

Lesson 33: The Mark: Chapter 16

Lesson 34: The Mark: Chapter 17

Lesson 35: The Mark: Chapter 18

Week 5

Week 6

Week 7

Week 8

Week 9

Week 10

Lesson 36: The Mark: Chapter 19

Lesson 37: The Mark: Chapter 20

Lesson 38: The Mark: Chapter 21

Lesson 39: The literary essay – novel

Lesson 40: The literary essay – novel (complete)

Lesson 41: Romeo and Juliet (Act 4, Scenes 1 – 2)

Lesson 42: Romeo and Juliet (Act 4, Scenes 3 – 4)

Lesson 43: Romeo and Juliet (Act 4, Scene 5)

Lesson 44: Romeo and Juliet (Act 5, Scenes 1 – 2)

Lesson 45: Romeo and Juliet (Act 5, Scene 3)

Lesson 46: Revision

Weeks 1 – 10 Revision – November examination

*Additional notes and updated lesson plans are available online on the Optimi Learning Portal (OLP). Refer to OLP for all other lesson content.

Sample

LESSON ELEMENTS

Vocabulary

The meaning of new words to fully understand the text/content.

For the curious Encouragement to do in-depth research about the content. Expand the activity and exercise to such an extent that learners are encouraged to explore.

Activity

Core content and questions to test the learner’s knowledge.

Core content

Emphasise the core content; in-depth explanation of a specific section of the lesson and must be understood.

Study/Revision

Time spent studying the content in conclusion of the unit and preparation for the test or examination.

Poetry

Sample

Alliteration The repetition of identical consonant sounds, most often at the beginning of words: ‘the flying furry fox’ or ‘steaming soup’ Alliteration is used to reinforce the meaning, to link related words or to provide tone and colour.

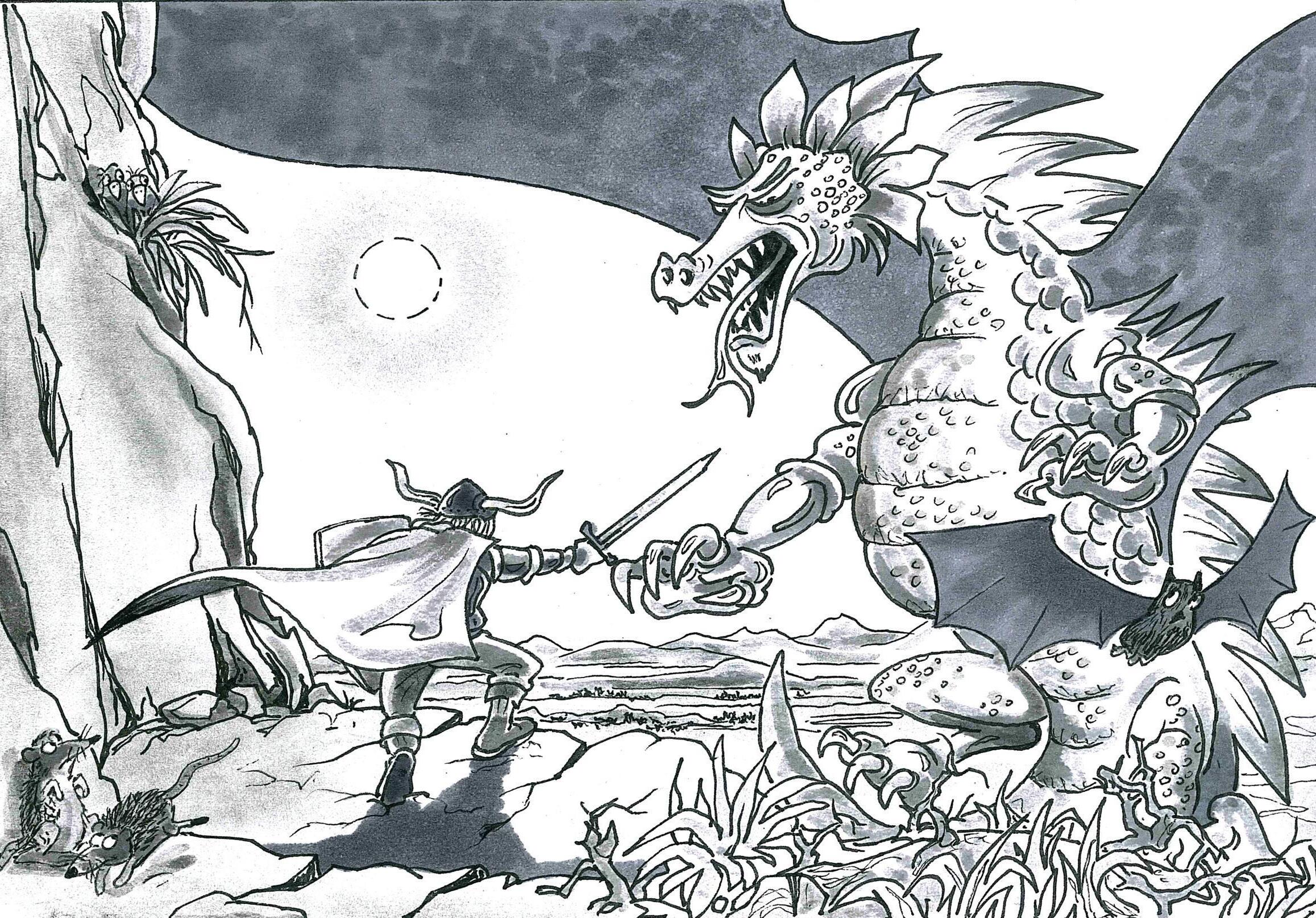

Allusion A passing reference to a person, place, thing, or event. Typically, writers allude to something they suppose the reader will already know about. The concept may be real or imaginary, referring to anything from fiction, to folklore, to historical events.

His nose gets longer whenever he talks.

Anaphora

Antithesis

Apostrophe

Assonance

Ballad

Words repeat at the beginning of successive clauses, phrases, or sentences. This is done for emphasis and typically adds rhythm to a passage.

In William Blake’s ‘London’, he uses anaphora: ‘In every cry of every Man, In every infant’s cry of fear, In every voice, in every ban, The mind-forg’d manacles I hear’

Sample

Two terms, phrases or ideas that contrast or have opposite meanings:

‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness …’

A speaker directly addresses someone (or something) that is not present or cannot respond. The entity being addressed can be absent, dead, or imaginary, but it can also be an inanimate object (stars or the ocean), an abstract idea (love or fate), or a being (such as a muse or god).

For example, John Keats begins his ‘Ode to a Grecian Urn’ by addressing the Urn: ‘Thou still unravished bride of quietness’ and directs the whole poem to the Urn and the figures represented on it.

The repetition of identical vowel sounds in different words close to one another.

The example is from Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘The Raven’:

‘Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore — While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.’

The ballad is typically arranged in quatrains and usually the second- and fourth lines rhyme (although this is not a rule). Ballads tell a story and began as folk songs and continue to be used today in modern music.

Blank verse

Cliché

‘A ballad of John Silver’ (John Masefield)

‘We were schooner-rigged and rakish, with a long and lissome hull, And we flew the pretty colours of the cross-bones and the skull; We’d a big black Jolly Roger flapping grimly at the fore, And we sailed the Spanish Water in the happy days of yore.

We’d a long brass gun amidships, like a well-conducted ship, We had each a brace of pistols and a cutlass at the hip; It’s a point which tells against us, and a fact to be deplored, But we chased the goodly merchant-men and laid their ships aboard.’

SampleDid you notice the allusion?

John Silver, the crossbones and the skull, the Jolly Roger – all these elements allude to the story of Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. You will get better at allusion the more you read. This will help you to recognise subtle details and references to other works.

Iambic pentameter that doesn’t rhyme. Blank verse is like normal speech but creates a musical effect. It tends to capture the attention of the readers and the listeners, which is its aim.

‘Tintern Abbey’ (William Wordsworth)

‘Five years have past; five summers, with the length Of five long winters! and again I hear These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs With a soft inland murmur. —Once again Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs, That on a wild secluded scene impress Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect The landscape with the quiet of the sky.’

Refers to an expression that has been overused to the extent that it loses its original meaning or novelty: abandon ship, the grass is always greener, silence is golden.

Couplet

Diction

Enjambment

Foot

Consists of two lines with the same metre or rhyme that are equal in length. In the case of the latter, you would refer to it as a rhyming/heroic couplet, which is very common in poetry and has the rhyme scheme: aa, bb, cc and so on.

Diction refers to the poet’s choice of words, phrases, sentence structures and the order of the words in a poem.

Poetic diction usually refers to the poet not adhering to the rules and conventions of standard written and spoken language when it comes to sentence structure, word order, the use of very old or newly coined words.

Sample

When reading a poem, consider the different meanings the words may have and how their arrangement in the poem adds to or changes those meanings. Diction reflects the writer’s vision and steers the reader’s thoughts. Poets choose words for a specific effect, e.g. a coat isn’t torn; it is tattered. Remember that each word in a poem, play or novel has a purpose.

A line with no end punctuation but running over to the next line.

Four of the first eight lines of Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 116’ are enjambed:

‘Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love That alters when it alteration finds Or bends with the remover to remove: O no! It is an ever-fixed mark That looks on tempests and is never shaken …’

A group of two or more syllables, one of which is stressed. The most common feet in poetry contain either a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable (trochee) or an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (iamb):

Thĕ cúr | fĕw tólls | thĕ knéll | ŏf pár | tĭng dáy. |

The iambic pentameter is the most natural and common type of metre in English and elevates speech to poetry.

Hyperbole

Idiom

Overstatement/exaggeration for serious, ironic or comic effect:

‘I’ll love you, dear, I’ll love you Till China and Africa meet, And the river jumps over the mountain And the salmon sing in the street .’

The tall tale of the American West is a form used mainly for comic effect. For example, Paul Bunyan, the huge lumberjack who eats 50 pancakes in one minute and dug the Grand Canyon with his axe.

SampleInternal rhyme (middle rhyme)

An idiom is a saying, phrase, or fixed expression that has a figurative meaning different from its literal meaning:

‘Fog’ (Carl Sandburg) The fog comes on little cat feet. It sits looking over harbor and city on silent haunches and then moves on.

The idiom referred to in this poem is ‘nothing ever lasts’. In the poem, the city appears to be normal as usual activities are taking place. However fog comes silently like a cat and everything changes. There is no visibility and most of the work comes to a halt. Even the poet has to sit and wait for the fog to go away.

Finally after waiting for sometime, it moves on. Again change happens and so the poem depicts that nothing lasts forever.

Rhyme within a line of poetry, i.e. the middle words and the end words rhyme with one another:

‘Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping …’

Irony

Surprising, interesting, or amusing contradictions or contrasts. Verbal irony: words are used to suggest the opposite of their usual meaning.

‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.’ Animal Farm (George Orwell)

Irony of situation: an event occurs that directly contradicts expectations.

From The Crucible (Arthur Miller)

SampleDANFORTH [reaches out and holds her face, then]: Look at me! To your own knowledge, has John Proctor ever committed the crime of lechery? [In a crisis of indecision, she cannot speak.] Answer my question! Is your husband a lecher?

ELIZABETH [faintly]: No, sir.

DANFORTH: Remove her!

PROCTOR: Elizabeth, tell the truth!

DANFORTH: She has spoken. Remove her!

PROCTOR [crying out]: Elizabeth, I have confessed it!

ELIZABETH: Oh, God! [The door closes behind her.]

REMEMBER

There is a difference between irony and sarcasm. Do not confuse the two when you analyse a poem or write an essay. Verbal irony communicates the opposite of what is said, while sarcasm is a form of irony that is directed at a person, with the intent to criticise or mock

It compares two things that are not alike but do have something in common.

Unlike a simile, where two things are compared directly using like or as, a metaphor’s comparison is more indirect, usually made by stating something is something else.

Metaphor

Metre

Metonymy

‘Dreams’ (Langston Hughes)

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die Life is a broken-winged bird That cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams

For when dreams go Life is a barren field

Frozen with snow.

Sample

The number of feet in a line of verse, e.g. iambic pentameter. The metre is determined by the pattern of stronger and weaker stresses on the syllables in the words in a line of verse.

Metonymy replaces the name of a thing with the name of something else with which it is closely associated.

Do not confuse metonymy with synecdoche!

Although they may seem the same, they are not. Synecdoche refers to a thing by the name of one of its parts/a part of something represents the whole, e.g. ‘new wheels’ refers to a new car and is a synecdoche, as a part of a car – the ‘wheel’ – represents the whole car.

In metonymy, the word we use to describe another thing is closely linked to that thing but is not a part of it, e.g. ‘the crown’ is used to refer to a king and his authority and ‘Hollywood’ can be used for the film industry. It is not a part of the thing it represents.

From Robert Frost’s ‘Out, Out–’

‘The boy’s first outcry was a rueful laugh, As he swung toward them holding up the hand Half in appeal, but half as if to keep The life from spilling. Then the boy saw all—’

Frost uses metonymy to describe blood spilling. Blood can spill, life cannot, but we know that blood is associated with life.

Octave

The first eight lines of an Italian or Petrarchan sonnet. It can be any stanza in a poem that has eight lines and follows a rhymed or unrhymed metre. The most common rhyme scheme for an octave is abbaabba

‘How do I love thee? Let me count the ways’ (Elizabeth Barrett Browning)

‘How do I love thee? Let me count the ways. (a) I love thee to the depth and breadth and height (b) My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight (b) For the ends of being and ideal grace. (a) I love thee to the level of every day’s (a) Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light. (b) I love thee freely, as men strive for right; (b) I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.’ (a)

Onomatopoeia

Oxymoron

Sample

A word that imitates the sound of a thing: buzz, hiss, chirp, rattle, bang, etc. For example, ‘slushy sand’, ‘quick, sharp scratch’, ‘tap at the pane’.

‘The Pied Piper of Hamelin’ (Robert Browning)

‘There was a rustling, that seem’d like a bustling Of merry crowds justling at pitching and hustling, Small feet were pattering, wooden shoes clattering, Little hands clapping, and little tongues chattering, And, like fowls in a farm-yard when barley is scattering …’

Two opposite ideas are joined to create an effect, e.g. bittersweet, civil war, deafening silence.

‘I Find no Peace’ (Sir Thomas Wyatt)

‘I find no peace, and all my war is done. I fear and hope. I burn and freeze like ice. I fly above the wind, yet can I not arise …’

Paradox A statement which may seem absurd or contradictory, but turns out to be interpretable in a way that makes sense or sheds light on the truth.

Personification

This is the beginning of the end.

‘What a pity that youth must be wasted on the young.’ –George Bernard Shaw

‘I can resist anything but temptation.’ – Oscar Wilde

In John Donne’s sonnet ‘Death, Be Not Proud’: One short sleep past, we wake eternally And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

do not confuse a paradox with an oxymoron!

Sample• A paradox is a statement/group of sentences/entire phrases/ quotes that contradict what we know while delivering an inherent truth.

• An oxymoron is a combination of two words that contradict each other (a contradiction in terms). It’s a dramatic figure of speech.

Giving human characteristics to nonhuman things or abstractions.

‘The Whole Mess ... Almost’ (Gregory Corso)

I ran up six flights of stairs to my small furnished room opened the window and began throwing out those things most important in life

First to go, Truth, squealing like a fink: ‘Don’t! I’ll tell awful things about you!’

‘Oh yeah? Well, I’ve nothing to hide ... OUT!’

I picked up Faith Hope Charity all three clinging together: ‘Without us you’ll surely die!’

‘With you I’m going nuts! Goodbye!’

The only thing left in the room was Death hiding beneath the kitchen sink: ‘I’m not real!’ It cried ‘I’m just a rumor spread by life ...’

Laughing I threw it out, kitchen sink and all and suddenly realized Humor was all that was left—

All I could do with Humor was to say: ‘Out the window with the window!’

Petrarchan sonnet

Pun

Refrain

A sonnet with 14 lines of rhyming iambic pentameter that divides into an octave (8) and a sestet (6). There is a ‘volta’ or ‘turning’ of the subject matter/thought/ argument between the octave and the sestet.

A pun is a play on words for humorous effect. It uses a word that suggests two or more meanings, or similar sounding words (homophones) that have different meanings. Puns can also make you think differently about a subject, particularly if it introduces ambiguity or changes the original meaning of the text.

SampleCalvin: Hey Hobbes, want to see an antelope?

Hobbes: An antelope?

Calvin: Come on! [goes to an anthill] See, she’s climbing down the ladder to her boyfriend’s car. [beat] You’re not laughing.

Hobbes: It’s not funny.

A phrase/line/part of a line/group of lines repeated at intervals within a poem, especially at the end of a stanza. Refrains are used in many ballads to make a point, establish central themes and create structure. You also remember repeated words more easily.

‘Do not go gentle into that good night’ (Dylan Thomas) ‘Do not go gentle into that good night, (1) Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. (2)

Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. (1)

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light.’ (2)