'I AM NOT A MATH PERSON"

'I AM NOT A MATH PERSON"

Amy Warke

ILASCD President

How often do we still hear someone say, “I’m not a math person!” or “I just don’t do math!”? Those words echo in classrooms and conversations alike, and they remind us how deeply our early experiences with math can shape our lifelong relationship with it.

As I reflect on my own journey, I’m reminded of the years I spent practicing math facts through drills and timed tests throughout my elementary years. Despite all that repetition, those facts didn’t truly become automatic for me until my first year of teaching, when I was teaching my own students to learn them. It was then that I began to see math differently: not as something to memorize, but as something to make sense of, to question, and to explore.

Amy Warke, President awarke2008@gmail.com

Scott England, Past President esengland@umes.edu

Amy MacCrindle, President-elect amaccrindle@district158.org

Sarah Cacciatore, Treasurer scacciatore@d75.org

Andrew Lobdell, Secretary lobdella@le-win.net

Debbie Poffinbarger, Media Director debkpoff@gmail.com

Ryan Nevius, Executive Director rcneviu@me.com

Bill Dodds, Associate Director dwdodds1@me.com

Task Force Leaders:

Membership & Partnerships

Denise Makowski, Amie Corso Reed

Communications & Publications

Belinda Veillon, Jacquie Duginske

Advocacy & Influence

Richard Lange, Brenda Mendoza Program Development

Jamie Bajer, Heather Bowman, Scott England, Amy MacCrindle, Terry Mootz, Amie Reed, Dee Ann Schnautz, Belinda Veillon, Amy Warke, Doug Wood

As you read through this Winter Journal edition, you’ll encounter ideas that feel familiar yet offer refreshing new perspectives on math teaching and learning. Math instruction has its base in the Eight Mathematical Principles, yet continues to evolve. Today, it’s about fostering critical and creative thinking, encouraging students to learn from mistakes, building conceptual understanding, and connecting mathematics to meaningful, real-world problem-solving.

We’re also reimagining what it means to build strong mathematical foundations. Play, storytelling, inquiry, and consistent integration into daily routines all play vital roles in making math engaging and accessible for every student. Still, we recognize that challenges—such as instructional time and structural constraints—can make implementation complex.

Our Illinois Numeracy Plan provides a strong vision for moving forward, and it

invites us to reflect together on how we can deepen our collective understanding. How can we best support teacher leaders, school teams, and district leaders as they bring this vision to life? What additional resources, professional learning, or collaborative opportunities might further strengthen that work?

Within the pages of this edition, you’ll find thought-provoking articles that challenge us to think deeply about what

math learning can be. I hope these voices inspire you—to reflect, to reimagine, and to continue your own journey of growth as a math educator and leader.

Amy Warke, Ed.D. President, IL ASCD -

Ryan Nevius

ILASCD Executive Director

rcneviu@me.com

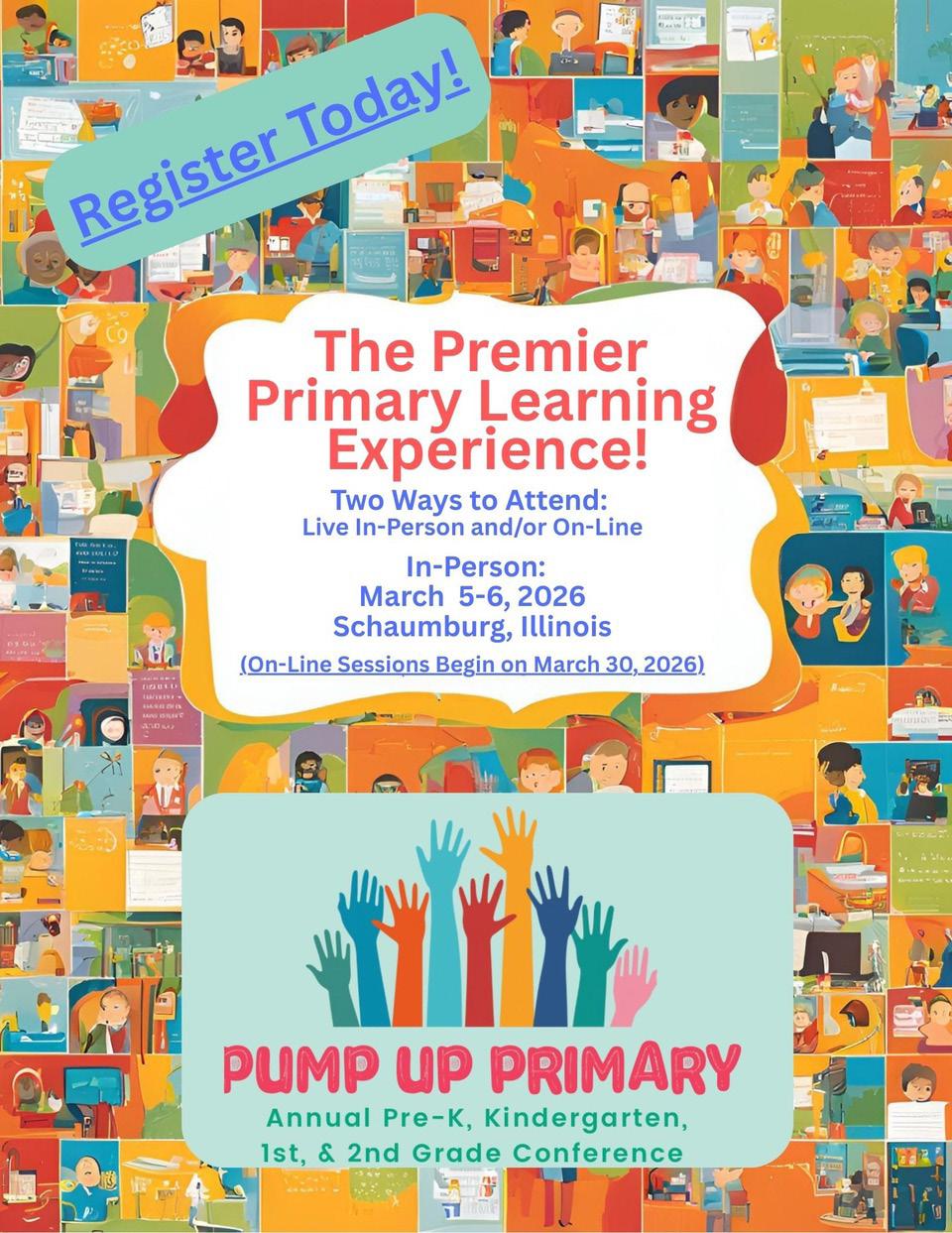

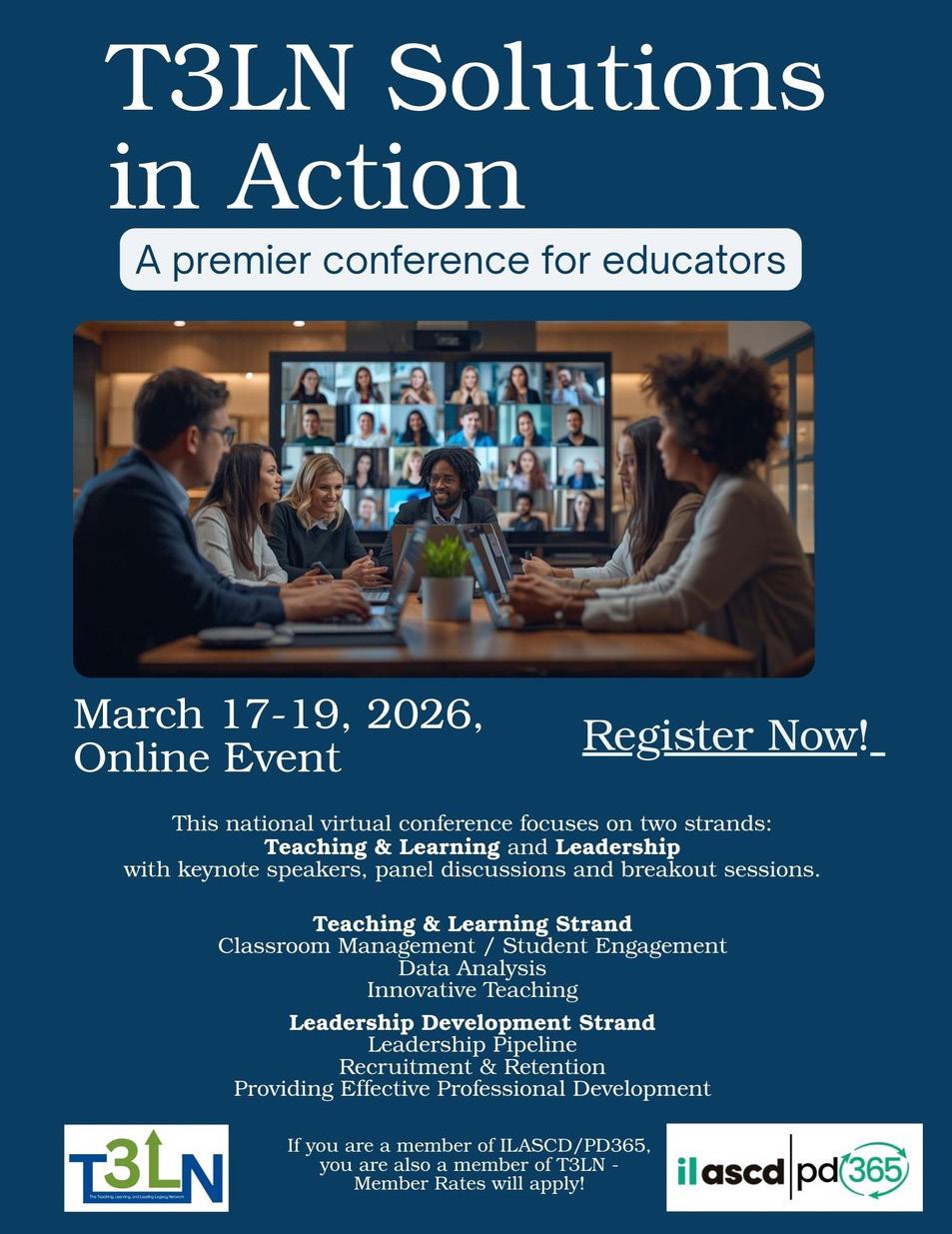

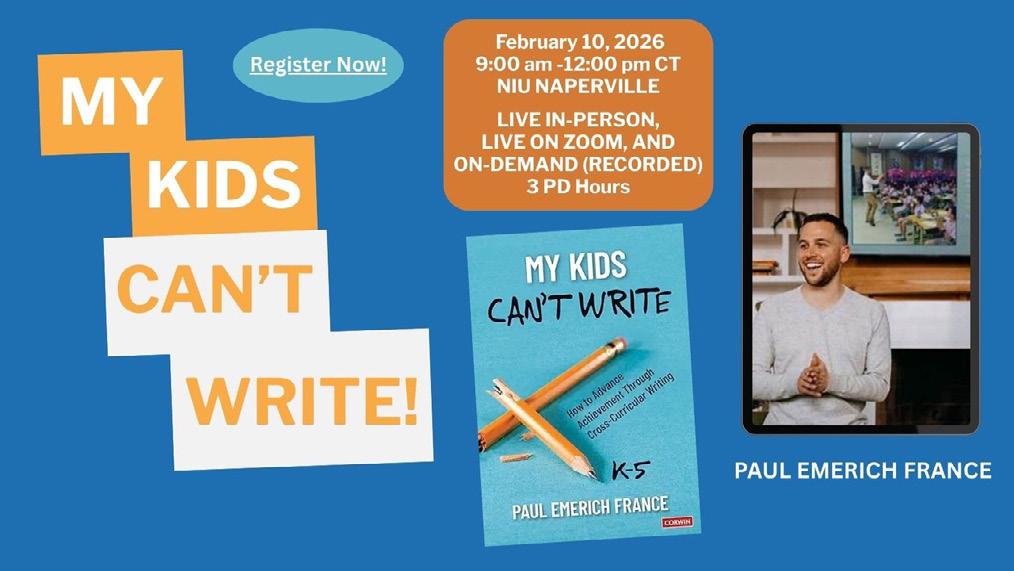

As we welcome a new year, I hope the holiday season offered you moments of rest, reflection, and connection. January always brings a renewed sense of purpose in our work as educators—and with it, excitement for one of the most energizing professional learning experiences in the Midwest: Pump Up Primary Conference, The 45th Annual Pre-K, Kindergarten, 1st, and 2nd Grade Conference, proudly hosted by Illinois ASCD/PD365.

Each spring, thousands of educators gather to celebrate and elevate the art of teaching our youngest learners. As we enter our 45th year, this event remains a practitioner-driven celebration of all things Pre-K through 2nd grade.

With uncertain budgets, ongoing teacher shortages, and the increasing challenge of finding substitute coverage, prioritizing professional development can feel more difficult than ever. Yet these challenges make time for renewal even more essential. Pump Up Primary provides a purposeful opportunity to step back, recharge, and reinvest in your professional craft.

Attendees leave with:

• Practical, classroom-ready strategies

• Reenergized purpose and a strong sense of community connection

• Access to national experts bringing cutting-edge research and inspiration

• Tools, resources, and solutions tailored for the unique needs of early childhood and primary educators

The 2026 conference—held March 5–6 at the Renaissance Schaumburg Convention Center—promises another unforgettable two-day experience. This year’s features include:

• Dynamic national keynote speakers who bring unmatched energy and expertise to early childhood and primary education

• Over 120 National and Local Speakers

• More than 225 breakout sessions designed specifically for Pre-K, Kindergarten, 1st, and 2nd grade teachers

• A high-energy Expo Hall filled with classroom resources, manipulatives, literacy and math tools, tech solutions, and hands-on demonstrations

• Dedicated transition times that ensure meaningful engagement between attendees and exhibitors

• A fantastic hotel experience with incredible food included in your registration costs.

What makes Pump Up Primary truly exceptional is its loyal, ever-growing community. Many districts send entire early learning teams to the conference, using it as a shared professional learning experience that strengthens collective practice. During the general session, we often ask participants how many years they have attended. It is not uncommon to see hands raised for 20, 25, and even 30 years—a testament to the conference’s impact and longevity. It’s no surprise that new educators often describe attending Pump Up Primary as the moment they “found their people.”

As we prepare for another record-setting year, we invite you to join us—and to encourage colleagues across Illinois to take part. Together, we can continue shaping joyful and developmentally rich classrooms for our youngest learners.

Registration is now open. We can’t wait to celebrate with you this March! Registration Details • Hotel Block Information • Vendor Applications

Ryan Nevius Illinois ASCD/PD365 Executive Director

If you ask a wide range of students how they feel about math, you are likely to hear some of these answers:

“I’m just not a math person.”

“I get so nervous, I can’t even think.”

“I used to like math…until the problems started getting harder. I’m just not that good at it.”

For years, math has been framed as a race to the rightor-wrong answer. The students who were good at memorizing the procedures and could then successfully apply them to quickly arrive at the correct answer were praised as “good at math,” while others were quietly deciding that math just wasn’t for them. As the Illinois Comprehensive Numeracy Plan notes, math anxiety and negative perceptions of mathematics now “compound the challenge for learners to succeed,” especially when math is seen as “an exclusive subject reserved for a few, rather than a right for all” (Illinois State Board of Education [ISBE], 2025).

We also know something about the brain: it doesn’t invest deeply in tasks that are of low interest and have a perceived low probability of success (Fitz &

Price, 2025). When students come to math already convinced they will fail, they naturally protect themselves by disengaging. Recent research continues to confirm that math anxiety undermines achievement, often by interfering with working memory and problem-solving (Ma & Sun, 2025; Finell et al., 2022).

The new Illinois Comprehensive Numeracy Plan gives us a powerful opportunity to change that story. It redefines numeracy as far more than getting to the right answers quickly. True “numeracy” extends beyond procedural fluency to encompass reasoning, problem-solving, and the ability to communicate and apply mathematical ideas and it is grounded in equity and the belief that all students can develop the skills and confidence to thrive mathematically (ISBE, 2025, p. 4).

The question becomes: How do we bring that vision to life in everyday classrooms?

My work with the four domains of connection: Connections to Self, Others,

Learning, and Community, offers one way forward (Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025). When we align these domains with the ASCD Whole Child tenets and the Illinois Numeracy Plan, we get a roadmap for rebuilding mathematical identity for every student, as we shift away from the concept that math is only for an elite few who are “naturally” good at it (ASCD, 2013; ISBE, 2025).

True “numeracy” extends beyond procedural fluency to encompass reasoning, problemsolving, and the ability to communicate and apply mathematical ideas...

The Numeracy Plan acknowledges that achievement gaps in Illinois remain “significant and longstanding,” especially for students from historically marginalized groups, due in part to inequitable access to high-quality, culturally relevant math instruction (ISBE, 2025). It calls for math to become a pathway of opportunity, not a barrier, by creating conditions where students see mathematics as useful, achievable, and deeply connected to their lives (ISBE, 2025).

That vision aligns closely with emerging research on mathematical identity

and belonging. A 2024 student using international assessment data found that students’ sense of school belonging significantly predicted their math achievement, even after controlling for prior performance (Allen et al., 2018). A 2025 dissertation examining high school students’ math sense of belonging showed that students who felt they “fit” in math class reported higher confidence and more persistence with challenging tasks (Stevenson, 2025). Work on “mathematical life stories” underscores how experiences of exclusion or affirmation shape students’ long-term relationships with math (Gweshe & Brodie, 2024).

Jo Boaler’s mathematical mindset work reinforces this: students who encounter math as a creative, sense-making subject, and who see mistakes as a valuable learning opportunity, develop stronger confidence and have higher math achievement than those who treat math as a subject that they are “naturally” good or bad at (Boaler, 2022). The Illinois plan clearly leans in this direction. It emphasizes that mathematics is not culture-neutral and that communities can help students feel that mathematics belongs to them, that it is meaningful, and that these instructional shifts “align with the vision of numeracy for all” (ISBE, 2025, p. 11).

To me, that is the heart of rebuilding mathematical identity, helping each student think, “Math is a part of my world, and I belong here.” The four domains of connection offer a practical way to do exactly that (Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025).

The Four Domains of Connection in a Numeracy

Whole Child Tenet Lens: Healthy, Supported, Challenged

Connections to Self are centered on how students see themselves as mathematicians. Do they see themselves as capable problem solvers, or as people who just try to “get through” math? The Numeracy Plan calls for instruction where “students see themselves as capable, persistent, and confident problem solvers,” not just accurate test takers, and highlights the importance of habits of mind such as perseverance, reasoning, and reflection (ISBE, 2025, p. 2).

When we design math experiences that explicitly build on Connections to Self, we:

• Normalize and value mistakes as data for learning. Boaler’s work shows that when students see mistakes as evidence of brain growth rather than failure, they engage more deeply and persist longer (Boaler, 2022;

Sengupta-Irving, 2016).

• Give students chances to choose strategies and explain why a method makes sense to them, not just which method the teacher prefers. The Numeracy Summit and draft Numeracy Plan frame fluency as efficiency, flexibility, and accuracy, including selecting and adapting strategies, not just recalling procedures (ISBE, 2025).

• Help students name their own math strengths through reflective pauses. For example, “I’m good at visualizing fractions” or “I’m good at explaining my thinking to others,” connecting this to growth over time (Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025).

From a student’s perspective, Connections to Self sounds like: “I used to be afraid to speak up in math. Now we actually talk about mistakes in class. I can say, 'Here’s what I tried and what I learned from it,' and that feels different. I get stuck sometimes, but that doesn’t mean I’m bad at math. It just means that I’m learning.”

This directly supports the Whole Child tenets of Healthy (reducing anxiety), Supported (explicit scaffolds), and Challenged (expecting all students to engage in rich thinking) (ASCD, 2013).

Whole Child Tenet Lens: Safe, Engaged

Connections to Others focuses on the social side of mathematics. The Numeracy Plan calls for discourse-rich classrooms where students justify reasoning, compare strategies, and engage in the Standards of Mathematical Practice (SMPs), especially constructing arguments and critiquing the reasoning of others (ISBE, 2025). Research continues to affirm that belonging and relationships are powerful predictors of math outcomes; a 2025 brief on positive conditions for math learning concluded that students achieve more when they experience strong relationships with teachers, feel a sense of belonging in the math community, and engage in highquality instruction that invites their ideas (Fitz & Price, 2025).

Connections to Others show up when:

• Design structures make thinking visible and shared. Peter Liljedahl’s Building Thinking Classrooms (2020) demonstrates that when students work in visibly random groups at vertical, non-permanent surfaces (whiteboards, windows, chart paper), more students think, talk, and revise their ideas, and they also take more intellectual risks.

• Normalize mathematical discourse as part of learning, not performance. Students regularly explain their reasoning, ask questions of peers, and build on one another’s ideas, reinforcing the Numeracy Plan’s emphasis on communication and justification (ISBE, 2025).

This domain aligns strongly with the Whole Child tenets of Safe (psychological safety to share ideas) and Engaged (active, social problem-solving) (ASCD, 2013).

...students learn best when classrooms are designed for interaction, where thinking is visible, talk is purposeful, and understanding is coconstructed rather than delivered...

Whole Child Tenet Lens: Engaged, Challenged

• In Essential Connection Skills, we emphasize that students learn best when classrooms are designed for interaction, where thinking is visible, talk is purposeful, and understanding is co-constructed rather than delivered (Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025).

From a student’s perspective, Connection to Others might sound like: “We don’t just sit alone doing problem sets anymore. Most days, we’re standing at the whiteboards in groups, trying to figure out a puzzle. I get to see how other people think, and sometimes my idea helps someone else. It feels like being a part of a team, and I end up understanding the math better.”

Connections to Learning is about meaningmaking, helping students understand why procedures work, when they are useful, and whether an answer is reasonable. The Numeracy Summit presentation and the Numeracy Plan offer a clear conception of fluency as the combination of efficiency, flexibility, and accuracy, including selecting appropriate strategies, adapting them, and evaluating reasonableness (ISBE, 2025). The plan calls for instruction that “blends understanding concepts (why), practicing skills (how), and applying knowledge to solve real-world problems (when and where)” (ISBE, 2025, p. 7).

Connections to Learning show up when we:

• Routinely ask students, “Does this answer make sense?” and build quick

estimation and over/under routines that make “reasonableness” a habit (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2023).

• Use low-floor, high-ceiling tasks that invite multiple solution paths instead of one narrow algorithm (Boaler, 2022).

• Give students opportunities to reflect on their own learning: “What strategy did you use today? How did your thinking change?” (Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025). Current research on motivation and interest in math suggests that when students see purpose and coherence in what they are learning, they are more likely to sustain effort and develop deeper understanding (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020; National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2023).

From a student’s perspective, Connections to Learning might sound like: “We don’t just learn a trick and then move on. My teacher always asks us to show another way or to explain why a method works. Sometimes that’s harder, but I actually remember it now, and it’s satisfying when math actually makes sense.”

This domain clearly supports the Whole Child tenets of Engaged and Challenged, as students grapple with meaningful, coherent mathematics (ASCD, 2013).

Whole Child Tenet Lens: Engaged, Supported

Finally, Connections to Community recognizes that math is not just a subject in school, it is a tool for understanding and shaping the world. The Numeracy Plan explicitly states that mathematics is “an important component of cultures throughout the world” and notes that ways of doing mathematics are culturally situated; communities that honor these connections help students feel that mathematics “belongs to them and is a meaningful part of their world” (ISBE, 2025, p.6).

Connections to Community show up when we:

• Use local data, such as attendance, neighborhood resources, school lunch waste, or community issues, as the context for math investigations (Turner et al., 2023; Yeh & Otis, 2019).

• Invite families and community members to share how they use math in their work and lives, affirming diverse mathematical practices (Turner et al., 2023).

• Connect projects to service-learning or real audiences, so that students experience math as civic and relational, not isolated, individual

performance (Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025).

Studies on identity and belonging in mathematics emphasize that when students see their cultures, languages, and communities reflected in math tasks, their sense of belonging and confidence grows (Burke, 2017; Gweshe & Brodie, 2024).

From a student’s perspective: “This year, we used data from our own school to make graphs and suggest changes to our bus routes. It felt like math actually mattered, not just for a test but for something real.”

This domain supports the Whole Child tenets of Engaged (real-world relevance) and Supported (acknowledging students’ full lives and identities) (ASCD, 2013).

It Together: The Whole Child, the Four Domains of Connection, and Illinois’ Numeracy Vision

Prior IL ASCD Whole Child articles have emphasized the importance of keeping schools human-centered, particularly as instructional demands, accountability pressures, and technology continue to evolve. This body of work reinforces the need to look beyond data points alone and to intentionally design learning environments that attend to the whole child. The ASCD Framework calls on schools to ensure that each

student is Healthy, Safe, Supported, and Challenged, not as a slogan, but in daily practice (ASCD, 2013). For this to take place, we need to collaboratively plan and deliver connection- driven instruction which will positively shape our students’ learning experiences.

The Illinois Comprehensive Numeracy Plan gives us a similar invitation in mathematics. It calls on us to:

• Address math anxiety and negative perceptions that keep students from engaging (ISBE, 2025; Ma & Sun, 2025).

• Build conditions where math becomes a pathway of opportunity, particularly for students from historically marginalized groups (ISBE, 2025).

• Ensure teaching blends conceptual understanding, skill practice, and realworld application (ISBE, 2025).

• Center equity, identity, and belonging in professional learning for educators (Allen et al., 2018; Fitz & Price, 2025; ISBE, 2025).

When we see these commitments through the four domains of connection, the “how” becomes clearer:

• Connections to Self help students rebuild a sense of themselves as

capable mathematicians (Boaler, 2022; Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025)

• Connections to Others create classrooms where thinking is visible, social, and safe, aligned with Liljedahl’s thinking classrooms and the SMPs (Liljedahl, 2020; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010).

• Connections to Learning ensure instruction is coherent, sense-making, and grounded in flexible fluency (ISBE, 2025; National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, 2023).

• Connections to Community anchor math in students’ cultures, futures, and civic lives (Turner et al., 2023; Yeh & Otis, 2019).

Together, these domains serve the Whole Child: Healthy, Safe, Engaged, Supported, and Challenged, not as shown in posters on a wall, but in the lived experience of a numeracy-based math class (ASCD, 2013; ISBE, 2025).

Rebuilding mathematical identity is not an “extra” on top of the Numeracy Plan; it is the work (Allen et al., 2018; Stevenson, 2025). As we design classrooms grounded in connection, we’re not just improving test scores; we’re prioritizing something students needed all along: a

sense that they belong in mathematics and that mathematics can help them to better navigate their world (Boaler, 2022; ISBE, 2025; Paonessa & Zwiers, 2025).

Allen, K.A., Kern, M.L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10648-016-9389-8

ASCD. (2013). Whole child tenets. https:// www.ascd.org/whole-child

Boaler, J. (2022). Mathematical mindsets: Unleashing students’ potential through creative mathematics, inspiring messages and innovative teaching. (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. https://eric. ed.gov/?id=ED620466

Burke, R. (2017). Language and culture in the mathematics classroom: Scaffolding learner engagement. In: Sellars, M. (Ed.), Numeracy in Authentic Contexts (pp. 91-109). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-98110-5736-6_6

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive,

and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cedpsych.2020.101859

Finell, J., Sammallahti, E., Korhonen, J., Eklöf, H., & Jonsson, B. (2022). Working memory and its mediating role on the relationship of math anxiety and math performance: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 798090. https:// www.frontiersin.org/journals/ psychology/articles/10.3389/ fpsyg.2021.798090/full

Fitz, J., & Price, H. (2025, June). Positive conditions for math learning: An overview of the research [Brief]. Learning Policy Institute. https:// learningpolicyinstitute.org/ product/positive-conditions-mathlearning-brief

Gweshe, L. C., & Brodie, K. (2024). Learners’ mathematical identities: Exploring relationships between high school learners and significant others. Mathematics Education Research Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394023-00479-5

Illinois State Board of Education. (2025). Illinois Comprehensive Numeracy Plan

(Draft 1). Authors. https://www.isbe. net/numeracyplan

Liljedahl, P. (2020). Building thinking classrooms in mathematics, grades K-12: 14 teaching practices for enhancing learning. Corwin. https:// www.corwin.com/books/buildingthinking-classrooms-268862

Ma, H., & Sun, C. (2025). The relationship between mathematics anxiety and mathematics achievement of middle school students: The moderating effect of working memory. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1566. https://doi. org/10.3390/bs15111566

National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2023, January). Procedural fluency in mathematics [Position statement]. https://www. nctm.org/Standards-and-Positions/ Position-Statements/ProceduralFluency-in-Mathematics/

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices, & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common Core State Standards for Mathematics. https://www.isbe. net/Documents/core_standards_ release.pdf

Paonessa, A., & Zwiers, J. (2025). Essential connection skills: Strategies for integrating social connections into

core content. Corwin. https://www. corwin.com/books/connectionskills-289436

Sengupta-Irving, T. (2016). Doing things: Organizing for agency in mathematical learning. Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 41, 210218. https://www.sciencedirect. com/journal/the-journal-ofmathematical-behavior/vol/41/ suppl/C

Stevenson, M. L. (2025). High school students’ sense of belonging in math (Doctoral dissertation, California State University, San Bernadino). https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/ etd/2211/

Turner, E., Ester Mariñoso, P., Civil, M., Quintos, B., Salazar, F., & Varley Gutiérrez, M. (2023). Parents and teachers doing math together. In Lamberg, T. & Moss, D., (Eds.), Proceedings of the forty-fifth annual meeting of the North American Chapter of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (Vol. 2, pp. 499–507). University of Nevada, Reno. https://files.eric. ed.gov/fulltext/ED658451.pdf

Yeh, C., & Otis, B. M. (2019). Mathematics for whom: Reframing and humanizing mathematics. Occasional Paper

Series, 2019 (41). DOI: https://doi. org/10.58295/2375-3668.1276

Anne Paonessa, Ph.D., is a the coauthor of Essential Connection Skills: Strategies for Integrating Social Connections into Core Content (Corwin, 2025) with Dr. Jeff Zwiers, and she is the founder of ConnectED Classrooms, an organization focused on helping schools embed connection-driven practices into core instruction.

She serves as an adjunct professor at National Louis University, is a mentor for new principals, and is currently working as a School Improvement Specialist supporting CPS schools. With more than 20 years of experience as a teacher, principal, and district administrator, Anne partners with schools and districts to strengthen student engagement, belonging, and learning through inclusive, Whole Child-aligned instructional practices.

by Aaron Montgomery

For most of the history of education, educators have used games in the classroom. Whether for physical education, as ways to break the monotony of routine instruction, or to allow students to take a break, games have long been integral to any classroom. For the last several decades, these games have included what may casually be called “board games” but are more accurately described as “tabletop games.” Tabletop games, which include games that use cards, dies, boards, pawns, spinners, tiles, miniatures, and any assortment of accessories that do not

easily fit into any category, are generally used in one of three ways:

• Engagement

• Exploration

• Experiences

Educators may use tabletop games for engagement when they want to provide students a break from traditional instruction, as a reward at the end of the week or, as I look out the window and see the 12 inches of snow from a recent early winter storm that is showing no signs of melting due to extreme cold, as a way to keep students occupied when

the weather prevents them from going outdoors for recess. It is not unusual to find a classroom, regardless of the gradelevel or content area, that has a ready supply of traditional board games such as Monopoly, Scrabble, Sorry, Clue, or chess/checkers, along with card games like Uno, Go Fish, or just a deck of playing cards that can be used for a wide variety of games.

Some educators, wanting to use games for more instructional purposes, may choose to incorporate them into the curriculum as a way of exploring concepts and skills. This may include “educational games” that teach academic vocabulary or math facts through flashcards or simple board games that require students to roll dice, move pawns, and then answer questions related to specific content areas. Teachers may also use traditional games to support academic concepts, such as using Monopoly to teach the basics of finances, Scrabble to practice letter-word recognition and spelling, and counting as students add up scores, or short-term simulations that have students imagine they are in a historical or non-school situation and, through prompts, challenges, and other tasks, have to reach a goal. (Consider here the classic computer game Oregon Trail, the source of deep consternation for school children throughout the 1980s and 1990s.)

A third way teachers may use games in the classroom is through experiential learning, such as full-blown classroom transformations, long-term simulations or role-playing games, or by converting the classroom itself into a game, known as a transformation or “gamification,” where students are in teams that are completing tasks, earning “experience points,” participating in “real-world” situations (such as designing a business or running a restaurant), and competing for a top position on a leaderboard.

All of these are common enough methods of incorporating tabletop games into the classroom that we hardly need to seek out citations to support this claim. Simply visit any classroom anywhere in the state, country, or even the world, and you are almost guaranteed to find evidence of games being used in at least one of these three ways.

However, there is another way that tabletop games can be used in the classroom, which is the focus of Aaron Montgomery’s Mathematics of Tabletop Games (2025), part of the AK Peters/ CRC Recreational Mathematics Series, published by CRC Press, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. Dr. Montgomery presents tabletop games not just as a way to supplement the learning experience for students but also as a source for teaching students about a variety of mathematical

concepts, including combinatorics, geometry, group theory, graph theory, probability, game theory, auctions, logic, and number theory.

The purpose of this book is to link mathematics and tabletop gaming in such a way that the reader can explore ways to answer mathematical questions through games. For example, many games use a combination of cards for players. Thus the game becomes a demonstration, rather than simply discussing a concept such as the

the second collection”) can be used to determine the number of possible combinations for an opening hand in the game. The answer, incidentally, is worked out as follows: P(11,2)/2! x P212, 8)/8! = 4,869,460,249,861,350 possible opening hands (p. 8-12). And since the average game time for Ark Nova is 90150 minutes, it would take four players approximately 15,430,388 years to go through every possible opening hand combination–thus all but ensuring the impossibility of ever experiencing the same game twice!

...use games as a way of exploring and understanding mathematical vocabulary...

Combination Rule, which states that “if k selections are made from a collection of size n without replacement, and the order of selection does not matter, then there are C(n, k) ways to make those selections, where C(n, k) = P(n, k)/k! or n!/k!(n-k)!”

Dr. Montgomery shows how an instructor could use the game Ark Nova to demonstrate how this rule, combined with the Product Rule (”if there are m objects in one collection and n objects in a second collection, then there are m x n pairs of objects where the first object comes from the first collection and the second object comes from

Another way to teach mathematics through tabletop games, rather than using games as an extension of instruction, is to use games as a way of exploring and understanding mathematical vocabulary, which often has specific uses different from colloquial usage. For example, in the chapter on Group Theory, Dr. Montgomery demonstrates how games that involve placing tiles that are constrained by adjacency rules, such as Carcassone, Galaxy Truckers, and Railroad Ink, to define the following mathematical terms: group, which is defined by three properties: identity, inversion, and closure; and equivalence, which is

defined by the properties of reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity (p. 49-50). Likewise, in chapter 9, which focuses on Number Theory, the game Codenames is used to explore the Fundamental Theory of Arithmetic, and the game Hanabi is used to demonstrate the principles of modular arithmetic.

Whether you are a fellow tabletop gaming enthusiast or just a math educator looking to teach mathematics through a non-traditional format, or are simply looking for a way to change up your traditional curriculum, Mathematics of Tabletop Games provides questions and prompts that can be used to teach mathematical concepts through gaming.

Alex T. Valencic is an educator, former small business owner, bibliophile, and geek of all things. As the Professional Learning Coordinator for Freeport SD 145, he supports the development and implementation of innovative educational practices in the classroom and leads the district mentoring leadership team. He served as FSD’s Elementary Summer Learning Administrator from 2021 to 2024, where they offered academic and enrichment classes that included robotics, 3-D art, and tabletop gaming.

“Why,” Su asks then, “don’t we approach mathematics the way that we approach art?” READ MORE...

Game-based learning isn’t about replacing rigor. It’s about sparking curiosity, reducing fear and fostering a genuine love of learning. READ MORE...

Using puzzles, both at home and in classrooms, can restore the often-forgotten truth that learning happens in conversation. READ MORE...

Vertical learning encourages students to get out of their seats and work collaboratively with their classmates to solve equations and story problems. READ MORE...

EMPOWERING EDUCATORS, FAMILIES, AND STUDENTS THROUGH MATHEMATICS Twana Young is a visionary leader deeply committed to empowering educators, families, and students through mathematics. READ THE INTERVIEW...

MATHEMATICS IS THE SENSE YOU NEVER KNEW YOU HAD | EDDIE WOO | TEDXSYDNEY High school mathematics teacher and YouTube star Eddie Woo shares his passion for mathematics, declaring that "mathematics is a sense, just like sight and touch" and one we can all embrace. WATCH THE VIDEO... Browse His

Using words like ‘factors,’ ‘denominators’ and ‘multiples’ may be part of a constellation of good math teaching practices. READ MORE...

Mentioning numbers during everyday activities could be more beneficial than workbooks and exercises. READ MORE...

Students get to share their favorite family recipes and practice their problemsolving strategies in this engaging math project. READ MORE...

The kitchen is one of the easiest and most enjoyable places to see math in action. READ MORE...

I’d love to say it was intentional but it’s really more of a happy accident that this has come to play a big role in decreasing the math anxiety in my students. READ MORE... Did You Know? Read

n this playful, inspiring talk, the founder of Math for Love offers teachers and parents alike a five-step guide to sharing the beauty and playfulness of mathematical thinking with children. WATCH NOW...

James Burnett

For more than a century, helping students learn basic number facts such as 9 + 6 = 15 has been a goal of elementary mathematics. Yet despite generations of effort, many students beyond Grades 3 and 4 still lack automatic recall.

We simply cannot continue relying on the same outdated pattern — a brief flurry of activities to “introduce” strategies, followed by months of repetitive practice in the hope that facts will somehow be committed to memory.

Nowhere is this issue more evident than in the United States, where structural realities make this traditional model almost certain to fail. Why do I make this claim? Because U.S. schools operate on an unusually short academic calendar, about 180 school days a year. That’s 20 days (one month) fewer than in Australia, and 40 days fewer than in Singapore. Add to that a long summer break — the perfect opportunity for students to forget what they learned — and it’s no surprise that fact fluency erodes rather than deepens over time.

And let’s not mention the number of minutes dedicated to teaching math each day and the instructional time lost to maintaining two measurement systems!

So while extending the school year may be beyond the control of most districts (and certainly teachers), there is something that can be done right now: adopt a different approach to fact fluency — one that works even when we’re short on time, because it builds long-term understanding.

In this article, I’ll share a five-stage model for teaching fact fluency. To illustrate the model, I’ll use the Make-10 addition strategy, as it is one of the most widely recognized and explicitly cited strategies in contemporary state and national mathematics standards both in the U.S. and abroad.

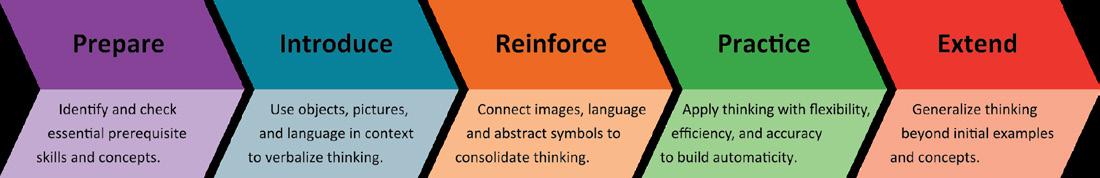

The visual model below illustrates the five sequential stages of fluency development: Prepare, Introduce, Reinforce, Practice, and Extend.

teachers must ensure that students possess the prerequisite knowledge and skills needed for success. For the Make10 strategy, students should:

• Have a deep conceptual understanding of addition

• Be able to read, write, and count numbers to at least 20

• Be able to subitize quantities and recognize visual number patterns

• Have had experience using fiveframes and ten-frames

While the first three are non-negotiable, the fourth is strongly recommended. A well-structured core program gives kindergarten students opportunities to fill five-frames, helping them see that five is the sub-base of ten. Over time, they use ten-frames to represent numbers greater than five.

The Five-Stage Model for Building Fact Fluency

Each stage has a purpose and aligns with how children move from concrete experiences to abstract reasoning.

1. Prepare

The visual model below illustrates the five sequential stages of fluency development: Prepare, Introduce, Reinforce, Practice, and Extend.

Before introducing any new strategy,

Once readiness has been established, we move to introducing the strategy. At this stage, students use hands-on counters to physically make a ten. A meaningful context helps anchor the idea to something familiar — connecting new learning to prior experience.

For example, suppose we want to find the total cost of these two items.

teachers wish to capture students’ reasoning, the vertical alignment of the ten-frames naturally aligns with the horizontal equation that includes the equivalence symbol.

At this point, the link between action, language, and symbol begins to take shape.

ouble ten-frames and counters to represent the value of each item, as shown

uble ten-frames and counters to represent the value of each item, as shown

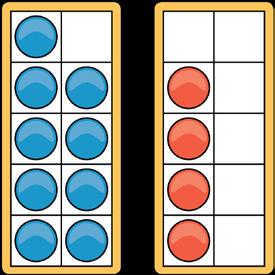

Students use double ten-frames and counters to represent the value of each item, as shown below.

[CAPTION: 9 + 4 = 13]

[CAPTION: 9 + 4 = 13]

To see this process in action, you can view a short demonstration on my YouTube the Number from Down Under, which models how to teach the Make-10 strategy u double ten-frames and counters (watch here)

ation intentionally leverages the prior understanding that nine is five and most importantly, that nine is one less than ten. Through careful questioning, ompted to move counters to find the total value

tion intentionally leverages the prior understanding that nine is five and most importantly, that nine is one less than ten Through careful questioning, ompted to move counters to find the total value.

y As students move the counters, we wan t them to verbalize their thinking, and four is the same value as ten and three.”

nd four is the same value as ten and three ”

To see this process in action, you can view a short demonstration on my YouTube channel, the Number from Down Under, which models how to teach the Make-10 strategy using double tenframes and counters.

This stage allows students to assimilate and internalize the strategy It serves as a connecting the concrete and pictorial models of the int roductory phase with the a symbols used during practice

. As students move the counters, we want them to verbalize their thinking,

rk is required, but if teachers wish to capture students’ reasoning, the vertical

This representation intentionally leverages the prior understanding that nine is five and four more, and most importantly, that nine is one less than ten. Through careful questioning, students are prompted to move counters to find the total value.

e ten-frames naturally aligns with the horizontal equation that includes the mbol.

k is required, but if teachers wish to capture students’ reasoning, the vertical e ten-frames naturally aligns with the horizontal equation that includes the mbol

Because classroom time is precious, this stage often moves to pictorial models Th teachers from constantly distributing manipulatives while keeping the learning vi interactive

he link between action, language, and symbol begins to take shape.

e link between action, language, and symbol begins to take shape

Language is key. As students move the counters, we want them to verbalize their thinking, such as: “Nine and four is the same value as ten and three.”

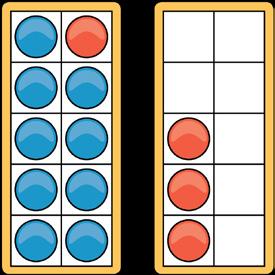

This stage allows students to assimilate and internalize the strategy. It serves as a bridge — connecting the concrete and pictorial models of the introductory phase with the abstract symbols used during practice.

A simple folding card can help remind students of the thinking they developed ear counters and frames. When the card is opened, they see both parts (for example, n four). When folded, they see the ten and the remaining three visually reinforcin relationship they discovered

No written work is required, but if

Because classroom time is precious, this stage often moves to pictorial models.

These free teachers from constantly distributing manipulatives while keeping the learning visual and interactive.

A simple folding card can help remind students of the thinking they developed earlier with counters and frames. When the card is opened, they see both parts (for example, nine and four). When folded, they see the ten and the remaining three — visually reinforcing the relationship they discovered.

[CAPTION: “Nine

add four is the same as ten add three.”]

But it isn’t enough to use this folding card on its own. To truly reinforce the strategy, students need an activity that bridges the concrete and the abstract, like the one shown on the following page.

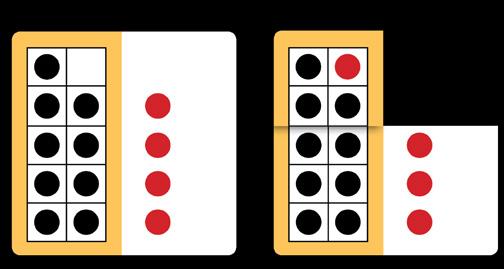

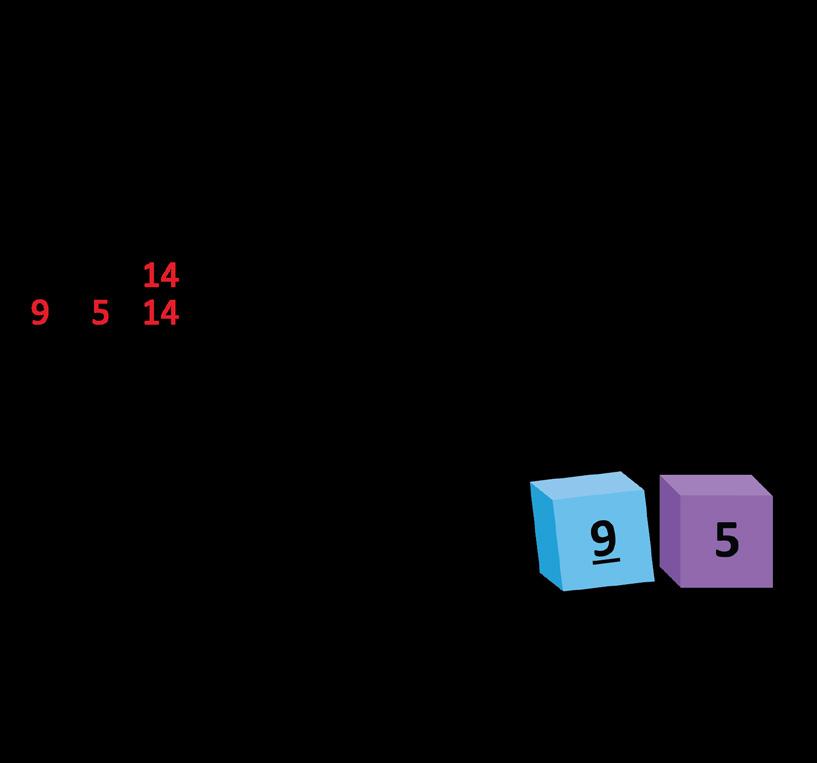

In this task, students write the numerals shown on the right on the six faces of two blank cubes. They roll the cubes and search their activity sheet for

the matching equation that will help them find the sum. They then record the answer for both related facts. For example, rolling a 9 and a 5 reinforces that 10 + 4 has the same value as 9 + 5.

Activities like this are not conceptual, so they cannot be part of the “Introducing” stage — but they are not yet practice either. They deliberately bridge the visual model and the symbolic representation.

We don’t provide enough of these transitional experiences, yet it’s here that students truly begin to own the strategy — moving from manipulation to mental imagery, and from guided reasoning to independent recall.

Only after students have grasped the underlying idea do we focus on automating recall. Practice develops accuracy and speed, but it must remain meaningful. I encourage teachers to select or design games that focus specifically on the target facts while gradually incorporating previously learned facts from the Count On and Use Doubles number fact clusters for addition.

Remember that time is critical, so practice sessions should be frequent (daily) and short (up to 5 minutes). It is better to do five 5-minute sessions a week than one 20-30 minute session on one day.

In this task, students write the numerals shown below on the six faces of two blank cubes

They roll the cubes and search their activity sheet for the matching equation that will help them find the sum They then record the answer for both related facts

The final stage—and perhaps the most overlooked—is extension: applying the same strategies to greater numbers, fractions, and decimals.

For example, rolling a 9 and a 5 reinforces that 10 + 4 has the same value as 9 + 5

Activities like this are not conceptual, so they cannot be p art of the “Introducing” stage but they are not yet practice either They deliberately bridge the visual model and the symbolic representation

If students can successfully use a strategy to calculate 9 + 4 = 13, why not encourage them to use that same thinking later to solve 29 + 15 = 44? When students view numbers as quantities, not symbols, they know they can decompose and recompose values just as they did with counters on a double ten-frame.

We don’t provide enough of these transitional experiences, yet it’s here that students truly begin to own the strategy moving from manipulation to mental imagery, and from guided reasoning to independent recall.

6 5. Extend

For instance, they can see that 15 can be broken into 14 and 1, and that moving one unit to the other addend creates 30 + 14, an easier calculation. Similarly, with 398 + 56, students who think strategically recognize that this is equivalent to 400 + 54. This is a mental adjustment that simplifies what would otherwise require a written algorithm.

The same reasoning applies as students progress into fractions and decimals. In 1 5/7 + 4/7, the strategy becomes one of making a whole rather than making ten.

Likewise, 1.95 m + 2.45 m can be seen as 2.00 m + 2.40 m, again simplifying the calculation through compensation.

In both cases, students generalize a strategy first learned in the early grades. The skill is no longer about “making ten” — it’s about making sense. When students internalize strategies this way, they build a lifelong understanding of how numbers work.

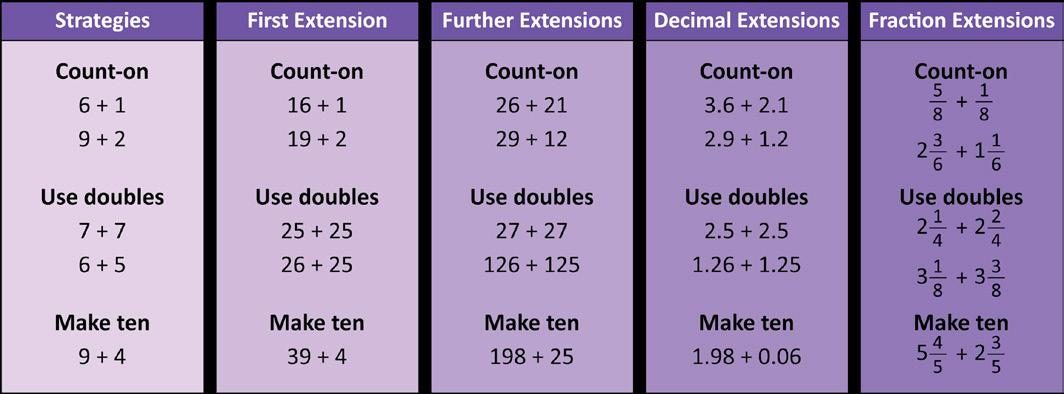

The image below shows how the basic addition strategies can be extended across the grades. Strong core programs will have these progressions naturally embedded in their developmental sequence, and effective curriculum leaders will understand why they are there.

forget their facts; it’s that we too often stop teaching for understanding too soon. When fluency is taught this way, it doesn’t fade over the summer. It endures—because it’s built on understanding.

Fact fluency is not a topic to be covered and tested — it’s a foundation to be expanded, even in classrooms short on time. The problem isn’t that students

The image below shows how the basic addition strategies can be extended across the grades. Strong core programs will have these progressions naturally embedded in their developmental sequence, and effective curriculum leaders will understand why they are there.

James Burnett is the co-founder of ORIGO Education, an award-winning mathematics education company serving schools across Australia, North America, and beyond. With more than 30 years’ experience as an educator, author, and curriculum designer, he has written and co-authored over 300 mathematics resources, including Stepping Stones, a comprehensive K–6 program. A frequent keynote presenter throughout the United States, James is recognised for helping educators make mathematics meaningful, enjoyable, and accessible for every learner. He also shares practical classroom insights through his YouTube channel, the Number from Down Under, which showcases contemporary ideas for teaching mathematics.

When we think about mathematics instruction, it’s easy to picture problem sets, formulas, and step-by-step procedures. Yet, math classrooms that cultivate critical thinking look and sound different. In these spaces,

In these spaces, students don’t just do math; they think mathematically.

students don’t just do math; they think mathematically. It isn’t about the knowledge, but the understanding, which makes it critical thinking.

Critical thinking in math isn’t about harder problems; it’s about deeper reasoning. It’s when students move beyond the “how” to explore the “why” and the “what if.” The goal is not merely procedural fluency, but the development of flexible thinkers who can analyze, justify, and apply mathematical ideas across contexts.

Students engaged in critical thinking don’t take formulas at face value. They explore where mathematical rules come from and test their limits.

“Why does this formula for area always work?”

“What happens if we double one dimension but not the other?”

This kind of inquiry transforms math from memorization to meaning-making. When students are encouraged to question, they start to see patterns, make conjectures, and build their own understanding of mathematical relationships.

Critical thinkers can explain their process clearly — in words, numbers, and

math is a language for reasoning, not just computation.

Critical thinking thrives when students compare and evaluate strategies.

“Would factoring or the quadratic formula be more efficient here?”

“Can we solve this geometrically instead of algebraically?”

When students see there is more than one valid path to a solution, they begin to appreciate the creativity inherent in

When students are encouraged to question, they start to see patterns, make conjectures, and build their own understanding of mathematical relationships.

visuals. They justify how they reached an answer and can defend it to others. Ask students, “Why do you know your answer is correct?” Hopefully, you start to get responses like, “I know my answer works because when I substitute it back, both sides of the equation balance.”

By requiring students to articulate their reasoning, teachers help them internalize mathematical structure and logic. It also allows peers to learn from multiple approaches — reinforcing that

mathematics. This comparison builds adaptability and deepens conceptual understanding.

Students who think critically connect math ideas across topics and to realworld contexts.

“This slope formula reminds me of the unit rate in proportions.”

“This geometry problem uses the same reasoning as a scale model in science.”

Connections make math stick. They help students recognize that mathematical thinking is a coherent system, not a collection of isolated rules.

Critical thinking also means treating errors as opportunities. Students reflect on missteps, identify misconceptions, and adjust their reasoning.

“Where did my thinking break down?”

“What assumption did I make that wasn’t true?”

When classrooms normalize this kind of reflection, they build resilience and foster a growth mindset that extends far beyond math.

True mathematical understanding shows when students transfer knowledge to unfamiliar contexts.

“This problem is new, but it reminds me of how we used systems of equations in the budgeting project.”

Whether through modeling, projectbased learning, or real-world applications, these experiences ask students to synthesize what they know — the essence of critical thinking.

Finally, critical thinking in math is

inherently social. When students discuss, defend, and critique reasoning respectfully, they sharpen their own thinking.

“I understand your process, but does that always work?”

“Can we prove your conclusion is true for all numbers?”

Collaborative dialogue turns classrooms into communities of reasoning — places where thinking is visible and valued.

In an Algebra I classroom, students were working on solving systems of equations. Initially, most students followed a substitution procedure without much discussion. I paused the class and asked, “Can anyone explain why substitution works?” Silence filled the room until one student replied, “Because we’re replacing one variable with what it equals.”

Pressing further, “What if we replaced it with something *not* equal what would happen?” This sparked a discussion about equivalence, balance, and maintaining equality.

By shifting from procedure to reasoning, we moved the class from doing math to thinking mathematically. Students began to see the connection between

equations, graphs, and real-world systems — the heart of critical thinking.

Critical thinking in math is not a new initiative or an add-on to instruction. It’s the heartbeat of meaningful learning. When we create classrooms where students question, justify, and connect ideas, we prepare them for more than exams. We prepare them for life’s complex problems that don’t come with answer keys.

Travis Mackey, a former math teacher and administrator, has 36 years of experience in education. He is passionate about integrating real-world problem-solving into math instruction. He has led district-level innovation around instructional leadership and student engagement across Illinois.

Mathematical literacy is an essential life skill to guide our understanding of economics, finance, science, and engineering. Mathematics influences the development of new algorithms that support the advancement of innovative fields such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and quantum science and engineering. As educators, we should strive to motivate students to continue their mathematics journey so they may be well informed, advance in these fields, and ultimately use their skills to improve the welfare of others.

As students learn mathematics throughout their education, however, they develop varying levels of confidence in whether they are a "math person" or not (Dresel et al., 2024). This happens, in part, due to the manner in which they are assessed. When they make numerous errors, students begin to believe they are not capable of understanding or performing well, and unfortunately, they perceive that they've reached a threshold for how math may be applied in their future. We believe all students are mathematical thinkers, and we need to find pathways to build efficacy.

One approach to building efficacy is to acknowledge that students learn and show readiness at different rates. In this article, we promote a progression approach to assessment that gives students choice in the problems they

(Hemmings et al., 2011). In early grades, high performance often provides opportunities to be placed in accelerated or gifted programs. Low performance sets the stage for students to feel frustrated and doubt their potential to

The net result has been greater self-awareness, willingness to learn from mistakes and tackle new challenges, and improved efficacy, helping them believe they are capable of continuing their mathematics journey.

believe they can solve. This is an evolution of a standards-based report card where students demonstrate performance against designated standards. As an added element, we are using assessment tools with varied difficulty-levels where students respond to questions at their readiness level, and then grow at different rates to achieve different levels of progress. The net result has been greater self-awareness, willingness to learn from mistakes and tackle new challenges, and improved efficacy, helping them believe they are capable of continuing their mathematics journey.

Past performance in mathematics paired with positive attitudes towards mathematics is a strong indicator of continued success in the subject

develop as mathematical thinkers. Ability groups intend to provide environments where students can engage in learning at their readiness level. However, even in advanced math classes, students' sense of efficacy is influenced by how well they are performing on their course assessments (Sakellariou, 2022). In essence, students’ sense of whether they are good at math is, in part, attributed to their perceived success.

The manner in which students are assessed influences students’ understanding of their success, and that can be problematic with traditional approaches to grading (Brookhart, 2017; Guskey, 2013; Willam, 2011). For example, by calculating the grade by averaging, early mistakes permanently lower a student’s course grade regardless

of whether they later mastered the same material. This often results in a lack of motivation, especially when it becomes impossible to earn an A or B, no matter how much the student improves. This can lead to test anxiety, since once points are lost, they cannot be recovered. For the same reason, there is not much motivation to learn from mistakes on a test. The points become the primary concern, as evidenced by the majority of student questions in office hours taking the form “will I get counted off if I write XYZ on a test?” or “can I get a point back on this problem?”, rather than serious questions about the content. Assessment shouldn’t be a motivation killer, but rather a feedback loop for students to want and feel like they could do better.

We believe, then, that systems of assessment should be designed so that students are showing signs of success through questions they are ready to solve rather than being measured with the same set of questions for all students. Varying the assessments is not a new phenomenon in education. Elementary educators, for example, provide different reading levels to students so they can all be engaged with their text at the appropriate challenge level (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). We argue the same should be true for mathematics. If students can be given problems where they are successful

independently, then they should be gradually challenged further in the classroom as well as on their assessments.

We endorse a progression assessment approach based on the learners’ readiness. The benefit of this approach is that it provides students the opportunity to build on their previous success rather than experiencing an unproductive struggle with content they do not fully understand. Knowing their level of success provides a fruitful opportunity for both students and educators to identify the next challenge level. The shift in thinking creates an environment where students realize they are on a learning journey of growth rather than learning trials of acceptance. Rather than feeling anxious about whether they can and cannot do math, students are rewarded by working at it until they understand. The goal is to build students' mindset of more self-confidence and to become more resilient when working through their mistakes. The following section describes Dr. Trimm’s transformation in assessment practices and the impact on student learning.

Starting in the Fall of 2022, I switched to a progression assessment approach, desiring an attitudinal shift towards greater self-awareness, motivation, and a

Progression-Based Assessment (cont.)

more positive view of mathematics. I also wanted to make sure that students were better-prepared for their future courses. In traditional grading, deficiencies in core areas can be made up for by doing well in others, so the grade averages out to a successful outcome. For instance, a student might have a failing assessment average, but earn enough points in categories for homework and participation so that they ultimately pass the course, despite serious deficiencies in their understanding. This approach does not set them up for success in future courses.

As advocated by Clark (2022) and Talbert (2022), grading should be based on

expectations by acknowledging that students can achieve different levels of success (e.g., sometimes described as “meets” or “exceeds”). There is no partial credit if the standard is not yet met – 70% is no longer “good enough.” Additionally, students have multiple opportunities to challenge themselves to their potential.

I have now used this progressionbased assessment system in a variety of mathematics courses ranging from Geometry to AP Calculus to post-calculus electives such as Linear Algebra and

All that matters is that a student eventually meets clearly-defined learning targets by the end of the course, and provides flexibility for how and when they get there.

abundance, rather than scarcity, where students have many opportunities to demonstrate learning and improve over time, without penalty for earlier mistakes. This acknowledges that students do not all start from the same place and do not all learn at the same rate. All that matters is that a student eventually meets clearly-defined learning targets by the end of the course, and provides flexibility for how and when they get there. Further, it also sets high

Differential Equations. My original approach was heavily influenced by that of Talbert (2022). In each of these courses, 15-20 clear learning standards are assessed multiple times throughout the semester. Each standard assessed is scored on a 4-point scale: (1) Beginning, (2) Proficient, (3) Advancing, (4) Distinguished, based on a holistic review of the student’s solution, rather than on points and partial credit.

Most assessments provide students with a choice of problems at different levels, differentiated by depth of knowledge (see Trimm, 2025, for an example). It is assumed that students will not finish the full set of questions, but rather choose the set of problems that they feel confident in solving. Students must be able to solve the more challenging questions for their solution to receive a 3 or 4. After each assessment, students are given feedback, have the opportunity to make corrections, complete targeted additional practice, and are offered an opportunity to be reassessed with a different set of questions to demonstrate understanding at a new level of proficiency. The new performance is the final score, which is different from my past practice of averaging scores, because students have demonstrated a new level of progress.

In each of these courses, I also assigned a weekly project or problem set on which students worked in pairs, mostly outside of class. These assignments synthesized different learning standards, applied them in a novel context, and/or guided an exploration deeper into the underlying theory. These assignments went into their own grading category as a separate requirement of the course, and could not be used to directly bring up progress levels as determined by solutions on timed, in-class assessments.

As advocated by French et al. (2024), I have also reframed the purpose of my final exam. Rather than think of it as solely a summative assessment of what students recall over the course, it is also one final attempt to level up on any standards on which they may have still needed more time and practice to master.

In sum, letter grades were determined at the end of the semester according to the level of success they achieved, rather than by a weighted average. All requirements for a given letter grade must be met to earn that grade; it is not possible to make up deficiencies in one area by doing well in another, which aims to avoid gaps in understanding. The threshold for passing the course was set so that the instructor could be confident that a student who passed the course would be prepared for success in the following course. Earning an A in the course required students to meet high expectations. The requirements for different letter grades were communicated to the students in the syllabus at the beginning of the semester, to make this as transparent as possible. Students know their progress on each learning standard throughout the semester, which tells them what they need to improve upon to earn the desired letter grade.

While the switch to progression-based assessment has reaped a lot of rewards,

I have had to endure some lessons along the way. I initially thought that grading would be more work through a progression-based approach to assessment. As with trying anything new, there was additional work involved, but by now the grading workload has turned out to be about the same for me, and I find it much more meaningful. Second, my first iteration of this grading system utilized

in the allotted time. To mitigate this problem, I now split my final exam into a required part and an optional part, taken on different days, with the required part covering a subset of core learning standards, and the remaining ones covered on the optional part.

I have learned this system encourages students to take academic risks. If they

In progression-based assessment, students often ask for more assessments because they don’t think of the assessment as a test, but rather a desire to demonstrate they are getting better. Test-anxiety seems to have almost completely disappeared...

binary scoring, according to whether or not the standard had been met. While this worked well enough initially, over time, I realized that the 4-level system better communicated growth to students. Third, I have learned that some students who have historically relied on partial credit or homework participation are initially challenged to meet course standards. However, that was ok, because they ultimately became more self-aware of the progressions they need to make in order to be successful. Finally, I initially found it difficult to meet my goal of using the final exam to reassess all standards at the same level as previous assessments

make mistakes along the way, they know they will be supported and have the opportunity to improve without penalty.

In traditional grading, students are incentivized to figure out what’s on the test so they may earn their desired level of points. What’s more important is what they are learning and what they are able to demonstrate. In progression-based assessment, students often ask for more assessments because they don’t think of the assessment as a test, but rather a desire to demonstrate they are getting better. Test-anxiety seems to have almost completely disappeared, which is consistent with Emeka et al.’s findings Progression-Based

(2023) findings on the effects of secondchance assessments on anxiety levels.

I also feel like I have a better relationship with students now compared to when I used traditional grading. With traditional grading, as noted in (Clark, 2022), the teacher can at times have an adversarial relationship with students as the keeper of the points. With progression-based assessment, the relationship feels more supportive as a coach. There are transparent expectations that students can work toward throughout the semester, and I am just here to help them reach their goals. My interactions with students after handing back tests and in office hours have been completely transformed, as the discussions are now focused on the content and how to improve.

I have received overwhelmingly positive feedback from students. In my course surveys, students frequently comment on having reduced stress and anxiety, increased motivation, and better retention of what they have learned. For example, one student from first-semester BC Calculus noted,

“I put in more work than I had in almost any other math class. I did this because I knew it was going to pay off. BC1 was my second-highest math grade at IMSA because of this. It was critical for my understanding in BC2, as I was able to

remember and apply almost all of the topics from the semester before.”

Students have also frequently commented on equity. For instance, one student noted,

“I learn calculus more slowly than others, and progression-based grading allowed my grade to reflect what I understood by the end of the semester.”

Another noted,

“As a student from an underserved school, I find that, as I continue through math, the concepts IMSA expects me to know I have never been taught… Although I have grown a lot, there is no doubt that I am at a disadvantage compared to my peers. For me, progression-based grading allows me time to catch up on concepts I have never learned.”

Finally, students also describe an increased enjoyment of mathematics. As one student reflected,

“I was able to understand and apply almost every topic. I was MUCH less stressed with math and really enjoyed the class. The class that I liked the most was math… I felt more capable of understanding the work that I received instead of just finishing it to get it out of the way… I put in an insane amount of

work, and it paid off. I put in that work because the class was fun and I was able to understand.”

Perhaps most strikingly, I have been told on more than one occasion that the tests were actually “fun”!

Changing to a progression-based assessment approach to assessment requires extra work, but the impact on students’ disposition and success has been worth it. We recognize that changing practices is not easy; however, as educators, we should constantly find ways to improve learning systems for the welfare of our students’ success and enjoyment of learning mathematics. They are more mindful of how they understand mathematics than ever before. Keeping this in mind, we encourage you to sample with progression-based assessment in ways that support your workload, and then build your practice as you see success.

Here are a few ways to get started:

1. Allow student choice on homework on an extended problem set

Provide a set of problems with varied difficulty, and ask students to tackle the most challenging problems they are able to do within a given time

period. Every problem should not be completed. Don’t spend time on the problems you automatically know how to do, but rather the ones you think you know how to get started and feel you can get through with some thought.

2. Customize quiz questions

When a student hasn’t developed proficiency in an important skill area necessary for the next course, provide them with additional opportunities on future assessments. If a student desires to excel in that skill, then provide them the chance to level up with a more challenging problem. The goal is to provide students with continued opportunities to demonstrate that they understand.

3. Offer chances for revision after minimal feedback

When students take an assessment, circle the location where they make an error. Hand back the paper and ask them to make a revision. Often, they can reconcile the mistake, and that will propel them to offer a better solution.

Naturally, a teacher has to identify how much they want to vary their assessment based on their capacity, resources, and the impact they see on learning. Our intention is to challenge students at their level of understanding and help them

grow through the assessment process. We feel it is necessary to keep students engaged in learning mathematics, especially when they face setbacks, so they realize assessment is a necessary tool to support their continued learning. We desire a sense that all students belong in mathematics, and through these assessment approaches, have built a sense of efficacy for students to embrace new challenges rather than worry about what’s on the test or whether or not they are good at math.

Brookhart, S. M. (2017). How to use grading to improve learning. ASCD.

Clark, D. (2022). Abundance and scarcity: Spicy takes from Benjamin Bloom. Grading for Growth. https:// gradingforgrowth.com/p/ abundance-and-scarcity

Dresel, M., Daumiller, M., Spear, J., Janke, S., Dickhäuser, O., & Steuer, G. (2024). Learning from errors in mathematics classrooms: Development over 2 years in dependence of perceived error climate. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/ bjep.12697

Emeka, C., Zilles, C., West, M., Herman, G., & Bretl, T. (2023). Second-chance testing as a means of reducing students’ test anxiety and improving outcomes. In Proceedings of the ASEE (American Society for Engineering Education) Conference. https://peer. asee.org/second-chance-testingas-a-means-of-reducing-studentstest-anxiety-and-improvingoutcomes.pdf

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2017). The Importance of Guided Reading Within a Multi-Text Approach. Fountas & Pinnell Literacy™.

French, S., Dickerson, A. & Mulder, R.A. A review of the benefits and drawbacks of high-stakes final examinations in higher education. High Educ 88, 893–918 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10734-023-01148-z

Guskey, T. R. (2013). The case against percentage grades. Educational Leadership, 71(1), 68–72.

Hemmings, B., Grootenboer, P., & Kay, R. (2011). Predicting mathematics achievement: The influence of prior achievement and attitudes. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 9(3), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763010-9224-5

Progression-Based Assessment (cont.)

Sakellariou, C. (2022). The reciprocal relationship between mathematics self-efficacy and mathematics performance in U.S. high school students: Instrumental variables estimates and gender differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 941253. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fpsyg.2022.941253

Talbert, R. (2023). Grading for Growth: A Guide to Alternative Grading Practices that Promote Authentic Learning and Student Engagement in Higher Education (with D. Clark). Routledge.

Talbert, R. (2022). How specifications grading changed. Grading for Growth. https://gradingforgrowth.com/p/ how-specifications-grading-changed

Talbert, R. (2020). Building calculus learning objectives. RTalbert.org. https://www.rtalbert.org/blogarchive/index.php/2020/07/09/ building-calculus-learning-objectives

Trimm, A. (2025). Sample progressive assessment: Squeeze Theorem [Unpublished Instructional Document] Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy https://drive.google.com/ file/d/1rQ1BvlysX96NkorSdR2WO VijyLDhm1pD/view?usp=sharing

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press.

Dr. Anderson Trimm, a mathematics faculty member at the Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy (atrimm@imsa. edu), has a variety of experience teaching mathematics and physics and is particularly interested in assessment practices that support student growth, confidence, and long-term engagement in mathematics.

Dr. Evan Glazer, President, Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy (eglazer@imsa.edu), is a lifelong mathematics educator who has written books about mathematics, including RealLife Math: Everyday Use of Mathematical Concepts and Using Internet Primary Sources to Teach Critical Thinking in Mathematics. He is deeply interested in the role assessment plays to support students’ learning and their continued interest in mathematics.

Aljobori is an educator and instructional leader with experience in early childhood, multilingual and curriculum design. He works across classroom, policy, and leadership settings, serving Childhood Educator Policy Fellow with Teach Plus Illinois and a Director-at-Large with Mindfully. His work focuses on integrating language development, equity, and whole-child and he contributes to professional communities through national conference presentations for Edutopia. He holds an MBA, an MEd in Elementary Education, and ESL/Bilingual endorsements, with ongoing work supporting multilingual learners and district-level program improvement.

Early math instruction in preK through grade 3 shapes how students approach problem solving, number relationships, and reasoning for years to come. Strong instruction in the early grades builds confidence, supports cognitive development, and lays the foundation for later success in higher-level mathematics. The Illinois Comprehensive Numeracy Plan emphasizes the importance of early learning environments that promote meaningful math experiences. These experiences help students form ideas through exploration, discussion, and reflection. Daily routines, intentional language, and play can strengthen early math thinking. Here are several practical examples that educators can use in any program model, including classrooms with multilingual learners and students with diverse needs.

Young children learn best when math is embedded in tasks they already understand. Daily routines give students repeated opportunities to use math in context. These routines help children develop operational fluency, comparison skills, and logical reasoning.

Teachers often begin the day with attendance. This

simple activity offers several math opportunities. Students count how many children are present, how many are absent, and how the totals change throughout the week. Students compare numbers, identify more or less, and describe what they notice.

• Transitions

Transitions between activities also support math growth. Teachers can measure walking time, compare the number of steps between classroom areas, or use timers to show the duration of each task.

• Classroom Jobs

Classroom jobs introduce grouping, estimation, and problem-solving.

Students determine how many items are needed, check their count, and adjust if the number changes.

2. Building Math Language Through Discussion

Math understanding grows when students explain their thinking.

Discussion supports conceptual development, clarity, and reasoning.

• Structured Math Talk

Teachers use short prompts that guide discussion: How do you know? What changed? What stays the same?

• Supporting Multilingual Learners

Students can explain ideas in their home language during small-group conversations while still using English vocabulary during whole-group sharing.

• Using Everyday Language First

Teachers begin with familiar terms such as bigger or smaller before introducing greater than or less than.

Play supports repetition, creativity, and collaboration.

• Block Building Students compare lengths, create symmetrical designs, and explore balance.

• Sorting and Classifying Sorting builds the foundation for data analysis.

• Dramatic Play

In pretend stores, students count items, compare prices, and distribute money.

• Outdoor Play

Students compare distances, collect natural items, and group them.

4. Linking Math Across Languages and Experiences

Teachers build on what students know from home. Connecting math to family practices increases relevance and engagement.