9 minute read

Architect to Happiness

Natalie Franzi Dougherty

Dr. Amy MacCrindle

Article

Architect to Happiness

Introduction

The pandemic has taken a toll on educators across the country, leaving many questioning the decision to walk into the classroom each day. Unhappiness leads to negative attitudes that seep under the cracks and impact the work that is going on. This leads to an environment where staff members do not feel supported enough to take risks and adapt. This is especially important in schools where student needs are constantly changing and educators must creatively adjust in order to do what is best for students.

At the root of educator happiness is a sense of efficacy. Efficacy is felt at an individual and group level. Teacher efficacy can be defined as, “The extent to which teachers believe that they have the capacity to affect student performance” (Gusky, 2021). Collective efficacy can be defined as “a group’s shared belief in its conjoint capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce at given levels of attainment” (Bandura, 1997, p.477). If we put those two ideas together, we have collective teacher efficacy which is, “the perception of a school’s faculty as a whole will have a positive effect on students” (Goddard, Hoy, & Woolfok, 2000).

Dr. John Hattie, expands the definition of collective teacher efficacy to teachers working together to a common goal (Hattie, 2018). In his study, he found that

collective teacher efficacy was 15% more influential in student success than self-reported grades, and almost 67% more influential on student success than socio-economic status. This means that an educator’s perception of their role and ability to make a positive impact on students as a whole directly correlates to student success. THIS is why HAPPINESS DOES MATTER and highlights why leaders should create an environment where happiness thrives.

This can occur by leaders focusing on three key steps:

Building Trust

“Setting a diverse workforce up for

Figure 1: John Hattie’s Visible Learning Effect Sizes

success requires a commitment to the practices of inclusion” (Heath & Wensil 2019). One way to do this is to establish norms for meetings and committee work. This helps to establish protocols that value equity by promoting every voice in the process. Below are norms that Natalie has used for meetings adapted from Student Achievement Partners:

1. Be present and prompt. Time is our most valuable asset.

2. Listen with the intent to understand.

Participate actively and ask questions for clarification.

3. Focus and take accountability for

your work and role in this project and your own learning.

4. Create a safe place to air confusion and ask questions; share your ideas and encourage others to do the same.

5. Support ideas with evidence.

Recently, Natalie tackled overhauling reading assessments with a team of teachers in her district. The work brought an array of emotions and opinions. In staying in alignment with norm number

Building a Coalition of the Willing

John Maxwell states, “Leaders become great not because of their power but because of their ability to empower others.” Student success cannot occur without the entire team working together. When a leader is willing to give up “control” over making all decisions and shift the decision making power to those who are closest to the situation, empowerment occurs. Empowered teachers are more likely to take on any situation with a “make it happen”

attitude and begin to take initiative in creating their own solutions to problems. That empowerment begins to build that coalition of the willing.

Empowered teachers are more likely to take on any situation with a “make it happen” attitude and begin to take initiative in creating their own solutions to problems.

five, participants framed their responses in a statement, evidence, and analysis format, which removed emotions and implicit biases that committee members may have by grounding the conversation in evidence. This process helped staff to think about their comments, and provided the language to ask questions that did not feel like a personal attack. This was especially helpful as committee members discussed the pros and cons of different assessments that were being investigated. Critical conversations are uncomfortable and are best tackled in an environment where every participant feels safe. Michael Watkins shares specific steps when it comes to building that coalition:

1. Gain Allies. By focusing on gaining allies who support the idea or process, you are better able to build momentum. This allows you to….

2. Recruit Others. The more people that you have supporting the initiative, the more likely you are to have success. This then….

3. Strengthen Your Resource Base.

People can be one of the most important and valuable resources. The more people you have in your corner allows you to help turn those who are on the fence into supports before they become opponents.

These three steps together help you ensure success. Amy has seen the power in a coalition of the willing in recent work with the Elementary Math Core Team in Huntley School District 158 located in Huntley, Illinois. Many would say that during a pandemic, now is not the time to make changes to key resources and teaching practices. But, this team of teachers have come together and decided that change is needed. This was accomplished through collaboratively writing a vision for math instruction, reviewing data and teaching practices, and participating in many conversations about instruction. This team was able to gain momentum to support this change, recruit others outside the team to support this as well, and now there is a strong team of teachers who are willing to make the change. This coalition of the willing know this will be a heavy lift for teachers, because it is what is best for students, there is commitment to the cause. When a coalition of the willing feels empowered, change occurs.

Building a Collaborative Decision Making Structures

In 1990 a Stanford University psychology student named Elizabeth Newton developed a study that showed the curse of knowledge. In Newton’s experiment she divided participants into two groups, one group would tap a song, while the second group guessed. The group of tapers were convinced that the songs that they tapped would be correctly identified. The study found that they were wrong with only 2.5% able to identify the song (Grant 2016). As leaders we are the tapers, but in our case we’re not only trying to perform, but we

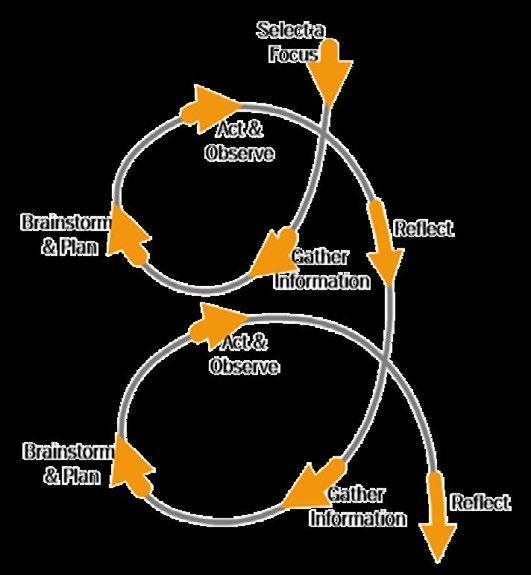

Metuchen’s Common

Inquiry-Based Research Cycle Threaded by

Metuchen Achievement Coaches and Adapted from: Action Research Processes: NJDOE Evidence-Based Conversations NYU Metropolitan Center for Urban Education Action Research Process Kemmis & McTaggart's Action Research Model Social Problem Solving Models: Dr. Maurice Elias, Rutgers University Dr. Myrna Shure, Drexel University Moss School Teachers’ Common Core Problem Solving Model SGO Processes: NJDOE SGO Process James Stronge SLO Process

COLLABORATIVE SCHOOL LEADERSHIP

PROBLEM SOLVING AND SHARED DECISION MAKING PROCESS

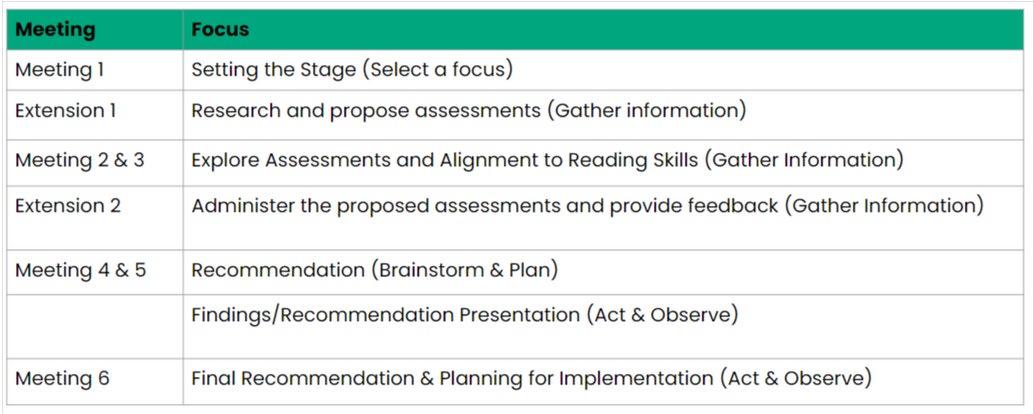

S.M.A.R.T. Goal S.M.A.R.T. Goal Figure 2: Problem Solving and Shared Decision Making model

have written the score. It is important to provide not only a clear explanation, but a structure to execute collaborative decision making.

Metuchen School District, where Natalie is a supervisor, has a deep history of collaborative decision making structures through its participation with Rutgers’ Collaborative School Leadership Initiative. Committees throughout the district follow the Problem Solving and Shared Decision Making model (See Figure 2) that contains structured selfquestioning at each stage in the process to guide the committee’s decision making. This structure provides a clear process to problem solve. As mentioned above, Natalie and a committee of teachers tackled assessments utilizing the Problem Solving and Shared Decision Making model. The below table (Figure 3) illustrates the process a recent committee took, while overhauling the reading assessment practices for kindergarten through grade four.

The process was clearly articulated at the beginning of the process allowing everyone to understand the direction the committee would proceed. In addition, it provided participants a picture of the long range plan that focused on weekly conversations.

Closure

When leaders emphasize creating environments where happiness is a priority, students are successful, staff are empowered to have critical conversations that result in improved school communities. If we want to tackle educator retention, then we need to build environments that promote teacher efficacy.

Figure 3: Committee Process

We challenge you to reflect on your leadership skills and find specific ways you can create this environment. Ask yourself: • How can I build trust through the use of norms in my setting? • What was a specific initiative, project, or goal where enabling a “coalition of the willing” would have made it more successful? • What structures are in place for collaborative decision making? • How can I ground conversations in evidence and research, proactively?

All stakeholders benefit from a leader’s intentional focus and commitment to building an environment of happiness. So, how will you begin to build happiness in your organization or school?

References

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-

Hall.

Goddard, R. D., Hoy, W. K., & Woolfolk

Hoy, A. (2000). Collective teacher efficacy: Its meaning, measure, and effect on student achieve-ment. American Education Research Journal, 37(2), 479–507. Grant, A. (2016). Originals: How nonconformists move the world.

Guskey, T. R. (2021). The Past and Future of Teacher Efficacy. Educational Leadership, 79(3).

Hattie, J. (2018). Mindframes and Maximizers. 3rd Annual Visible

Learning Conference held in

Washington, DC.

Heath & Wentzel (2019, September 6). To Build an Inclusive Culture, Start with Inclusive Meetings - Harvard ....

Retrieved January 23, 2022, from

https://hbr.org/2019/09/to-buildan-inclusive-culture-start-withinclusive-meetings

Metuchen’s Common Inquiry-Based Research Cycle [digital flow chart]. (2021). https://drive.google.com/

file/d/1vwu7z2xL_2O4kOiHqCcOD

HgKpUuP2RSQ/view

Natalie Franzi Dougherty is a districtlevel administrator in New Jersey. As an administrator, Natalie supports teachers and principals with curriculum and technology implementation. She is passionate about research-based interventions that support students academically and social-emotionally. Her teaching experience includes middle

school reading and special education in the inclusive elementary setting. Natalie was named a 2016 ASCD Emerging Leader and is the President of NJASCD. She can be found on twitter @NatalieFranzi and LinkedIn.

Amy MacCrindle, Ed.D, began her career teaching Middle School Language Arts and Social Studies, also serving as a Literacy Coach. She transitioned into administration, growing her experience as an Assistant Principal (MS), Principal (ES), Director of Literacy (PK-12), Director of Curriculum and is now the Assistant Superintendent for Elementary Learning and Innovation in Huntley District 158. Amy’s passion and expertise are in the fields of change management, curriculum and instruction, literacy, and school culture. She teaches as an adjunct professor in the fields of leadership, literacy, and EL learners. She also serves as the ILASCD board Secretary, and is a Class of 2016 ASCD Emerging Leader. Follow @Amy_MacCrindle on Twitter!