ISAAC TANG

CHRISTOPHER CHUNG

A VISUAL ANALYSIS OF PUBLIC SPACE INHABITATION IN TOKYO AND HONG KONG

CHUNG KWAN CHAK CHRISTOPHER and TANG CHUN HEI ISAAC are incoming final-year architecture students at the University of Hong Kong. This research stems from an interest in how street-scale architecture and design shape the use of public urban spaces by daily users, developing through an architectural exercise of drawing and photography.

Summer 2024 Hong Kong

Inhabiting the Street-Scale: A Visual Analysis of Public Space Inhabitation in Tokyo and Hong Kong © 2024 by Kwan Chak Christopher Chung and Chun Hei Isaac Tang is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

2 Hong Kong: Tsuen Wan

3 Tokyo: Shimokitazawa

Senrogai

Kōshindō

4 Tokyo: Nakano

In some ways, Hong Kong and Tokyo are similar in their post-war urban developments. Their recent histories of urban planning date back to post-WWII recovery, with Tokyo starting reconstruction after intense bombing, and Hong Kong considering its first urban planning schemes after Japanese occupation. [1] Both cities have had a period of post-war population boom and rapid development into Asia’s leading metropolises, which are characterised by the development of modernist mass housing blocks, for example in Shek Kip Mei of Hong Kong and Tatsumi district of Tokyo. [2] Both cities have also been described to be the densest in the world, with pockets of green spaces in between the urban areas. These parks, called “country parks” in Hong Kong, manifest themselves as breathing spaces between the vertically-dense urban areas that characterise it as a city with a 100% urbanisation rate. [3] On the contrary, Tokyo is more horizontal in its density, with extreme verticality restricted to certain areas within and around the Yamanote metro line loop such as Shinjuku, Marunouchi, Shibuya, and recently Shiodome and Roppongi, and large green parks dotted around and within. [4]

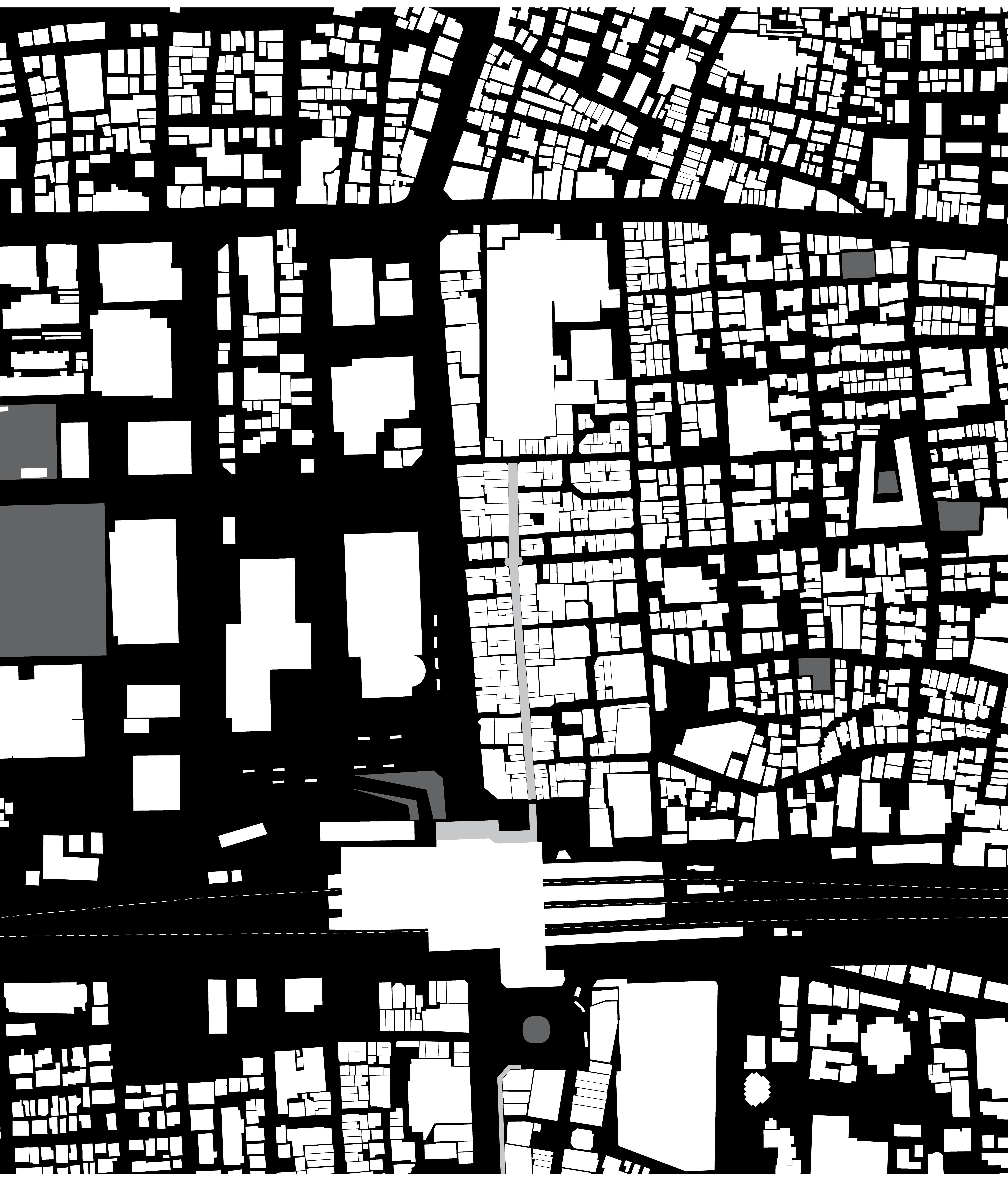

With such a dense urban environment in mind, we wanted to analyse the use of public space in local urban areas of Hong Kong and Tokyo, and examine three sites with similar zoning, lying outside the central business district of both cities, primarily developed for residential and commercial use. In Hong Kong, our cases are within one or two city blocks of each other, while in Japan our cases are in the same chomē near the main railway station of the site. A chomē is a small district within a ward or city in Japan, and is primarily used in addresses instead of street names. Our cases are all within close proximity of each other in the site, helping us piece together an idea of the site’s urban fabric.

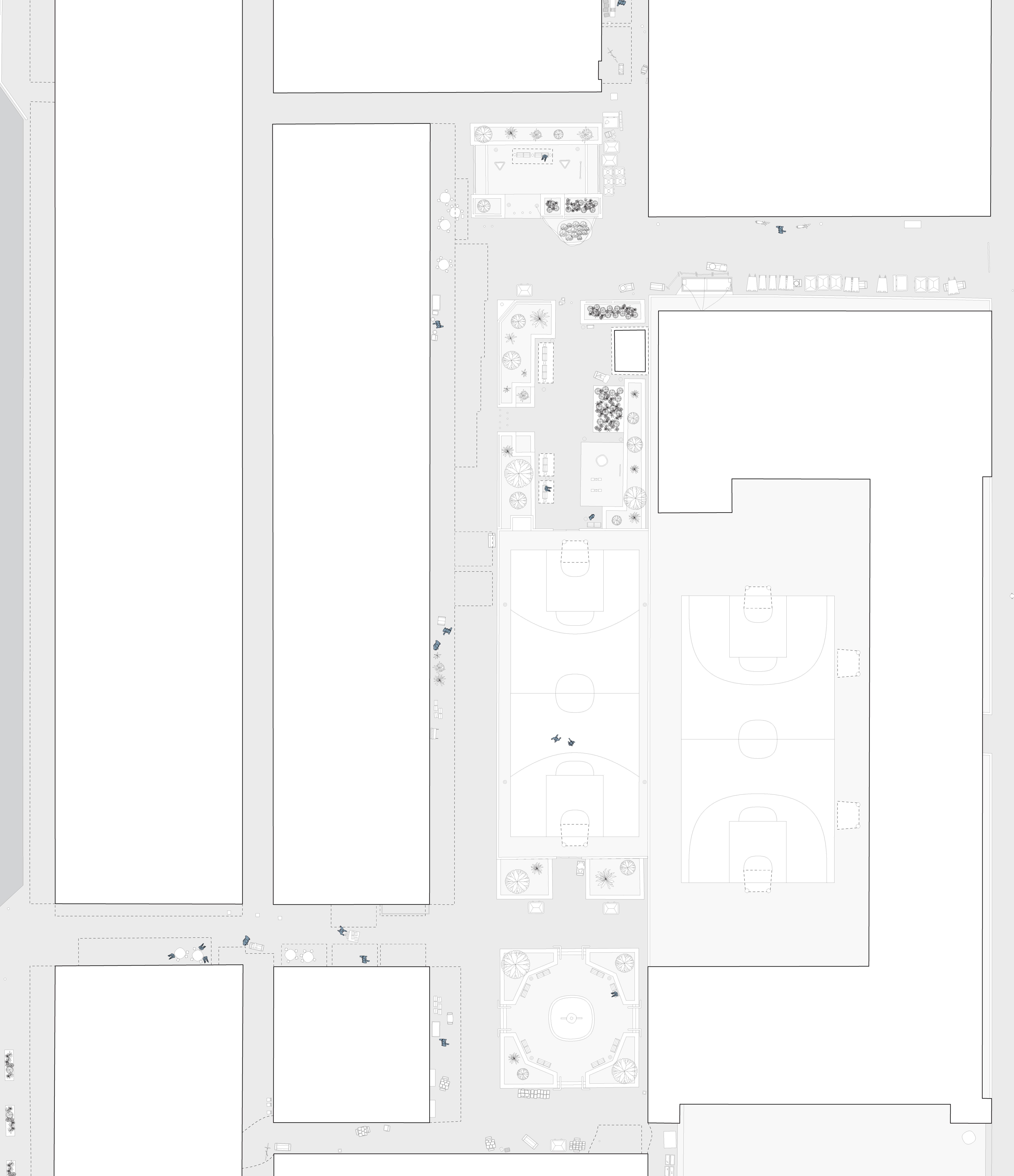

In Hong Kong, within one of the earliest satellite new towns in the New Territories, we chose four squares surrounded by tenement residential buildings in Tsuen Wan as our Hong Kong sites. Located in a crowded area with a sizable population, as well as ground-floor restaurants and shops, the squares become a microcosm of activities around dense mixed-use areas all around the city, including anticipated activities as well as unexpected ones. On a daily basis, urban inhabitation involves residents relaxing, restaurant deliveries being made, and grocery shopping happening in close proximity to each other.

In Tokyo, Shimokitazawa is a notable example of areas with commercial activities lining the main streets, surrounding the quiet residential neighbourhoods that lie within. While residential land use is mostly separate from commercial, inhabitants and visitors move to and from the commercial streets as corridors of traffic on a daily basis. These streets therefore not only act as vehicular access, but pedestrian pathways, storefront space, storage, and even as a congregation space.

Nakano’s shopping streets and commercial districts are located immediately outside Nakano Station along a north-south axis, and its sizable post-war low-rise commercial district, a type known as yokochō , is frequented by locals and tourists alike for its great variety of shops and restaurants. Given the popularity of the district, the alleyways transform from a commercial and shopping setting in the day to one of catering at night, when tables and chairs occupy the streets to create a boisterous dining scene. The inhabitation of space by objects and people are therefore in constant flux depending on time of day.

Japan has always been said to lack examples of plazas — wide, grand open spaces of the Western sense. [5] Hong Kong also lacks largescale plazas or open spaces for social congregation, with only three major parks (Kowloon Park, Victoria Park, Hong Kong Park) in the city and all developed after 1945. [6] Some studies note that these two East Asian cities may have a lot in common, especially in the treatment of streets as urban public space, the culture of public space use, as well as the scale at which urban interaction occurs. Jinnai notes that Japanese urban spaces “are experienced mostly by pedestrians”, when “a pocket park of moderate size [...] is more fitting than the large and empty European plaza”. [7] The boundaries of such urban spaces also shift based on events happening around the year, with most public religious festivals involving parades around streets. Similarly, Xue and Manuel argue that it is the lack of public park culture in Hong Kong (possibly of a sweeping Western sense again) that has contributed to a lack of adequate provision of recreational public space in the city, while Kinoshita’s analysis suggests it is a lack of housing space and privacy. [8] This is further echoed by Hidaka and Tanaka in their perspective on a lack of the concept of “publicness” in Japan. [9] On the other hand, this has indicated that what both cities lack in large-scale urban public spaces, they make up with ground-up initiated development of small-scale urban spaces, facilitating interactions in alleyways, small city squares, and recreational parks.

However, the continued rapid commercialisation of both cities has put these spaces and the improvised inhabitation that happen within them at risk. Recent urban studies of Tokyo have identified large-scale laissez-faire developments causing the city to lose a degree of spontaneity and flexibility found in post-war urban developments. [10] These new developments take form in Asian cities as tall residential buildings sitting on top of large multi-storey platform-malls in a medium or large

plot, sometimes a whole block in length and width, and possibly spatially extended with footbridges and suspended corridors to link malls when multiple plots are acquired. In fact, most metropolises have been building these developments, including Hong Kong. [11] This is not surprising considering a constant demand for housing in both metropolises, but the laissez-faire nature of such developments puts at risk the accessibility and public nature of privately-developed open spaces such as platform gardens and gated terraces, if they are ever developed.

With a severe land shortage and housing crisis, Hong Kong stands out with its laissez-faire land policy and the rise of an oligopoly of property developers. It has been noted that throughout Hong Kong’s rise and boom in the later half of the 20th century as a business hub, there has been little urban development policy dictation from the colonial or SAR governments, especially ones that guarantee sufficient public space for the use of its residents. Xue and Manuel note the significance of government policy dictating an allowance of just 1.5 square metres of recreational public space per resident, combined with a lack of interference with density zoning, to have caused a failure in the provision of public space. [12] Instead, most developments are given to commercial private developers, resulting in extreme speculation alongside smaller and smaller flat sizes. Plots of minuscule low-rise residential buildings are combined into mall-housing developments that stretch for blocks, as mentioned above, frequently occurring throughout the different districts within Hong Kong. Examples include, but are not limited to, areas designated for urban renewal, such as Kowloon City and Sham Shui Po, as well as select sites in Yau Tsim Mong district. These developments have ensured a steady disappearance of low-rise mixed use tenement buildings, as well as the improvised urban spaces in the streets in front and behind them, which used to be common all over Hong Kong. [13]

Tokyo has also had its issues in land development, having been most rampant in the 1990s before the housing bubble burst. Harassment from local real estate agents aiming to conglomerate smaller plots into one large plot prompted land owners to sell their land, reducing the amount of low-rise commercial and residential buildings within the city, and clearing out districts with yokochō for property development. [14] One of the most notable examples of this type of urban redevelopment is Azabudai, but also Roppongi and Toranomon in recent years. This has led to a decline of bustling “third spaces” between workplaces and residential spaces, in which human interaction and the use of public space are impromptu and organic. Described by Oldenburg as an informal public gathering space, “third places” can be attributed by distinct characteristics such as levellers that encourage social and cultural diversity, low profile places, and places that are easy to access and accommodate various sedentary activities. [15] In this case, yokochō allows for a diverse mix of small businesses, with flexible arrangements of space within and in front of bars, massage parlours, and restaurants. The removal and replacement of these spaces by large-scale regulated commercial development can arguably disincentivise human interaction and personalisation of space, instead catering to masses with a standardised experience.

Our aim is to document and understand these local developments from a ground-up perspective. We want to understand how these urban spaces are built and used, and how similar and different they can be while retaining East Asian public space characteristics. The thin commercial corridors of Shimokitazawa and full commercial blocks of Nakano contrast greatly in urban design, but the common recurrence of these two Japanese urban forms throughout Tokyo is comparable to mixed-use tenement squares in Tsuen Wan. The commonness of their urban design and inhabitation throughout their cities is what links them together as typical urban spaces.

When discussing methodology, it is necessary to acknowledge that understanding an urban environment through architectural drawing is reductionist most of the time, representing what is deemed important and abstracting distractions. Yet, the study of urban inhabitation is fuzzy — the boundary lines of the territory each individual and entity claim for themselves is blurred and overlapped, influencing each other in various social contexts and utilisation of space over time. With this reductionist architectural perspective and fuzzy urban environment acting contradictorily, we analyse two of the most “chaotic” cities in East Asia — Hong Kong and Tokyo. Although both are rigorously regulated to a certain extent, there exists in practice a lot of grassroot urban developments, such as parks, hawker areas, and sitting spaces created and initiated from the ground up by local residents.

In the book Emergent Tokyo: Designing the Spontaneous City , Almazán and McReynolds note that “micro-scale choices and actions of its residents” shape urban cityscapes. [16] A documentation of street corners, crossroads, and open spaces can be a method to study how human-scale choices and interactions become typical and essential in the way people use the space. We have adapted our knowledge of architectural drawing to hopefully portray the messiness and informality of people utilising these spaces. By mapping out the physical objects in the spaces we investigate, we understand more than the rules and regulations that govern that space, but also the different possibilities that inhabitants can use the space for, whether rule-conforming or not. Through understanding these small to medium-scale spaces, we strive to understand the current “urban norm” within these cities.

To examine the urban spaces in both cities rigorously, it is necessary for one to remove themselves from a tourist’s point of view. Especially for

us, by removing ourselves from the perspective of a Hong Kong resident, we minimise our biases and reconfigure ourselves in both cities based on local developments and daily occurrences. We therefore identify and categorise our sites based on criteria such as land zoning, building height, as well as our observations on site. Either way, we acknowledge the advantage of analysing both East Asian cities from an East Asian perspective, with a better grasp of urban norms and local cultu res.

Given the limited time and budget we have for this research, we have been able to choose four specific cases from each site, bringing the total to 12 cases. On-site analysis is crucial, with our trips in May and June of 2024 to the three sites contributing to our updated drawings and photographs. Alongside online resources, these trips provided us with valuable insights about how the urban cityscape has changed around those areas recently. Further research comes from literature and online resources, framing a wider perspective of both cities and three sites, helping us further define what the local status quo is in regards to urban space use.

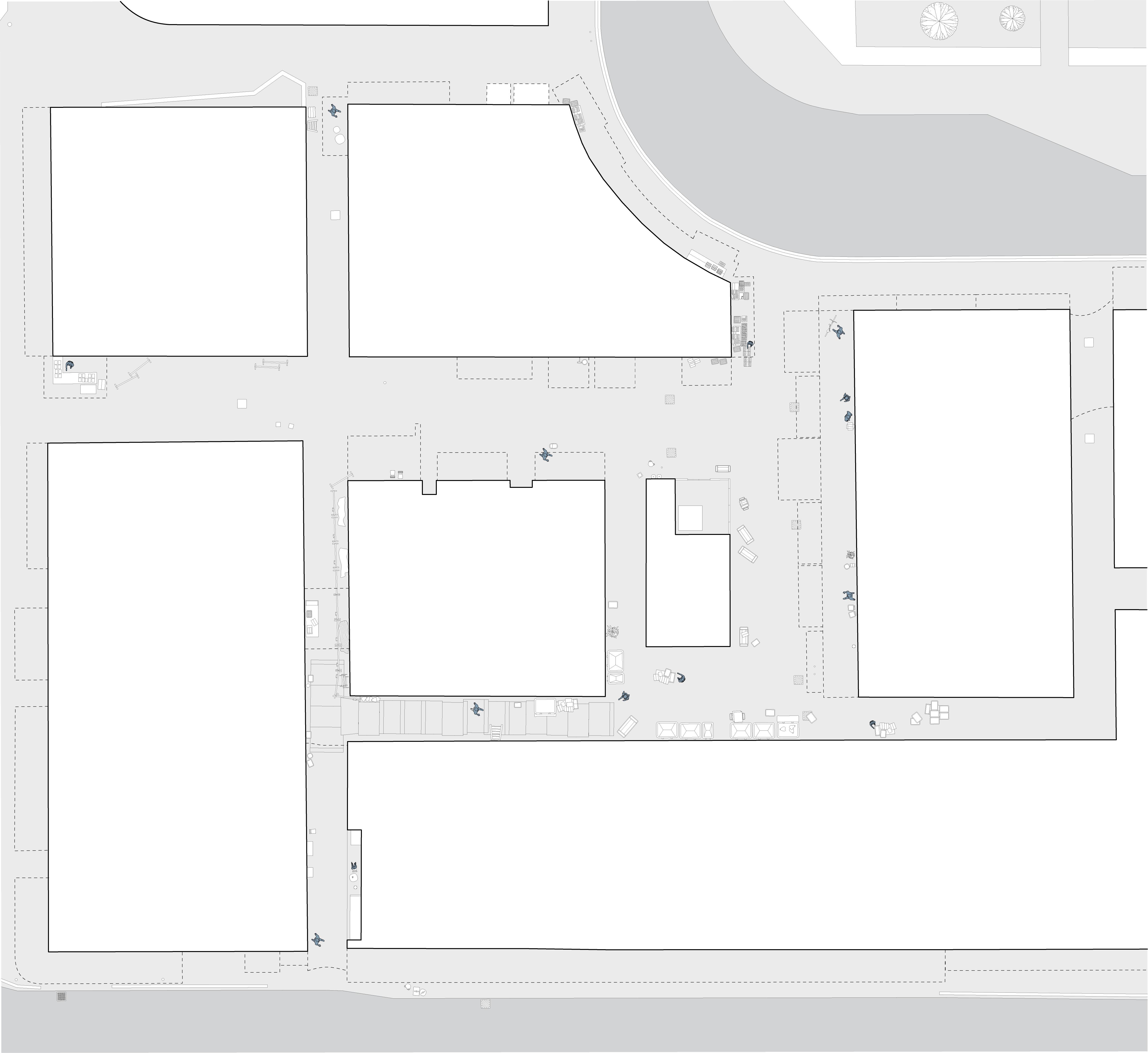

Tsuen Wan is an urban area developed as one of the first new satellite towns in the 1950s. Located within western New Territories along the coast northwest of the Kowloon Peninsula, and northeast of the island of Tsing Yi, it has a distinct industrial history that is still visible in its cityscape today. With a significant portion of its land reclaimed by the government into the Rambler Channel from the 1960s onwards, and a reconstruction of the squatters and fields of Hoi Pa, Yeung Uk and Ho Pui, a regular grid of streets and tenement buildings gave rise to the four pei -squares that exist today. The larger mid-rise block sizes and industrial background surrounding tenement buildings are common throughout new towns in Hong Kong.

In the early 1960s, with more buildings constructed around the growing Chung On Street and Sha Tsui Road, whole city blocks and squares started to form. [17] The first square to be constructed was Yi Pei Square around 1960, taking its name from Yi Pei Chun, a small hillside village one kilometre away that may have appeared as early as 1902. [18] Pei in Cantonese can mean waterside but also slope, and it is very possible that Yi Pei Chun meant “village on two slopes”, “village near two ponds”, or even “village between two riversides”, referencing its location between the rivers Tai Lek Ho and Kwu Hang. Further land reclamation to the east of Yi Pei Square created Sam Pei Square (literal translation: third waterside square) in 1963, when the construction of the neighbouring Saint Francis Xavier’s School started. [19] Meanwhile, although there were buildings approximately where Tai Pei Square and Sze Pei Square are today, they were lone-standing structures facing open fields, squatter houses, or sandy ditches. It was not until 1970 that most buildings around Sze Pei Square (lit.: fourth waterside square, a chronological nature of naming is established) were finalised, and the name appears in a 1975 map. [20] At roughly the same time, the car park and buildings around Tai Pei Square (lit.: large waterside square) began construction, and were well established by 1982. [21]

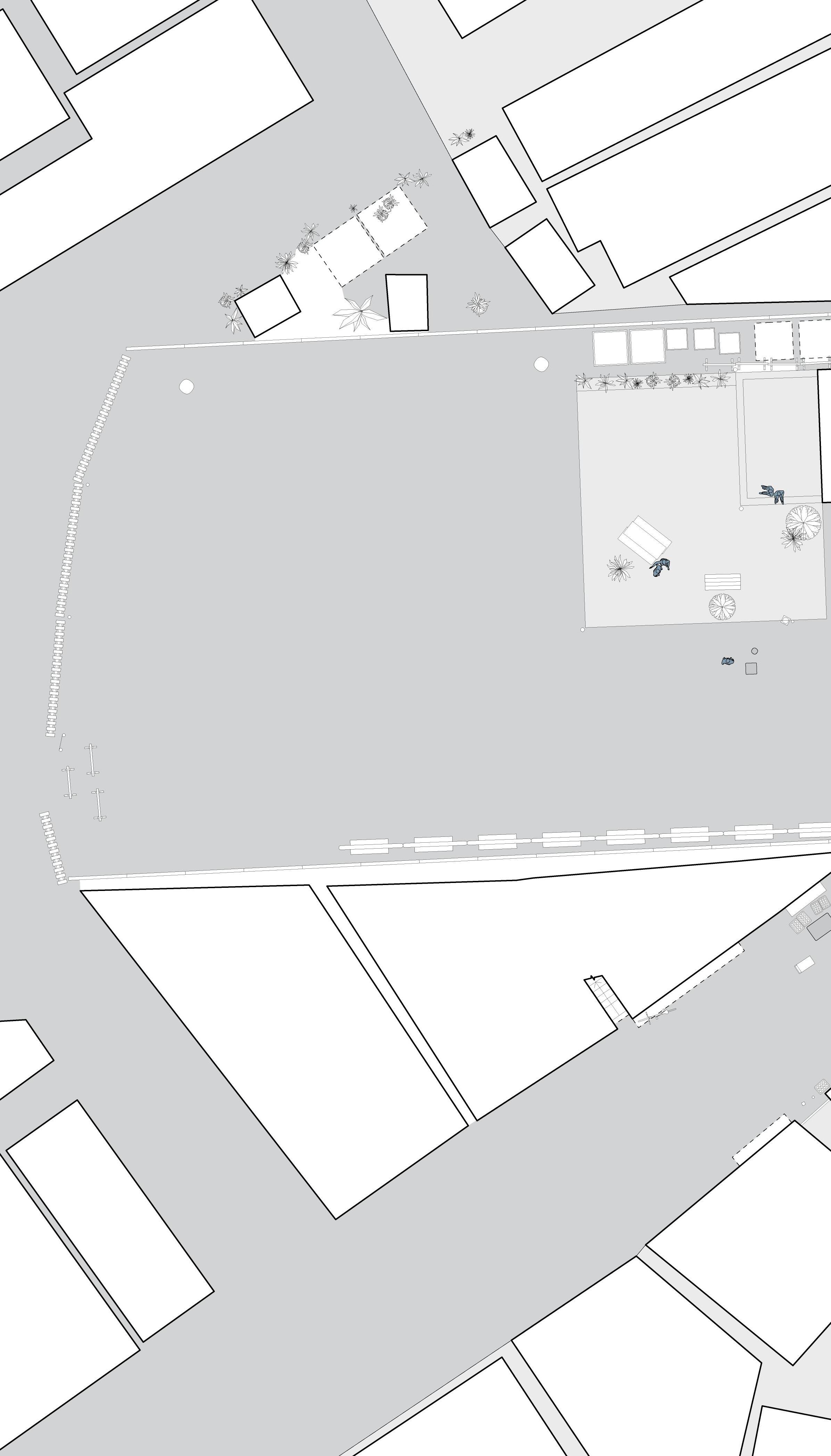

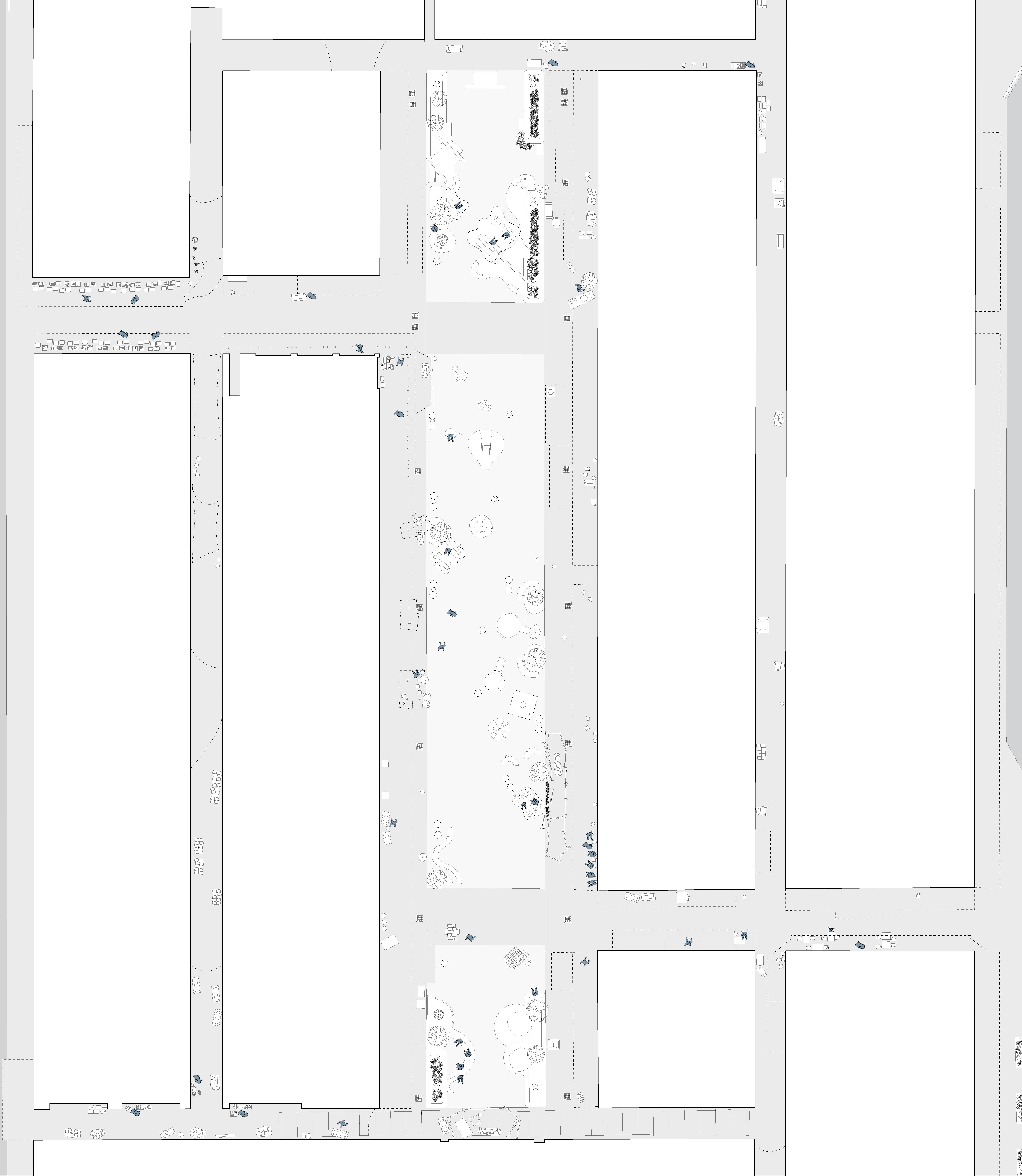

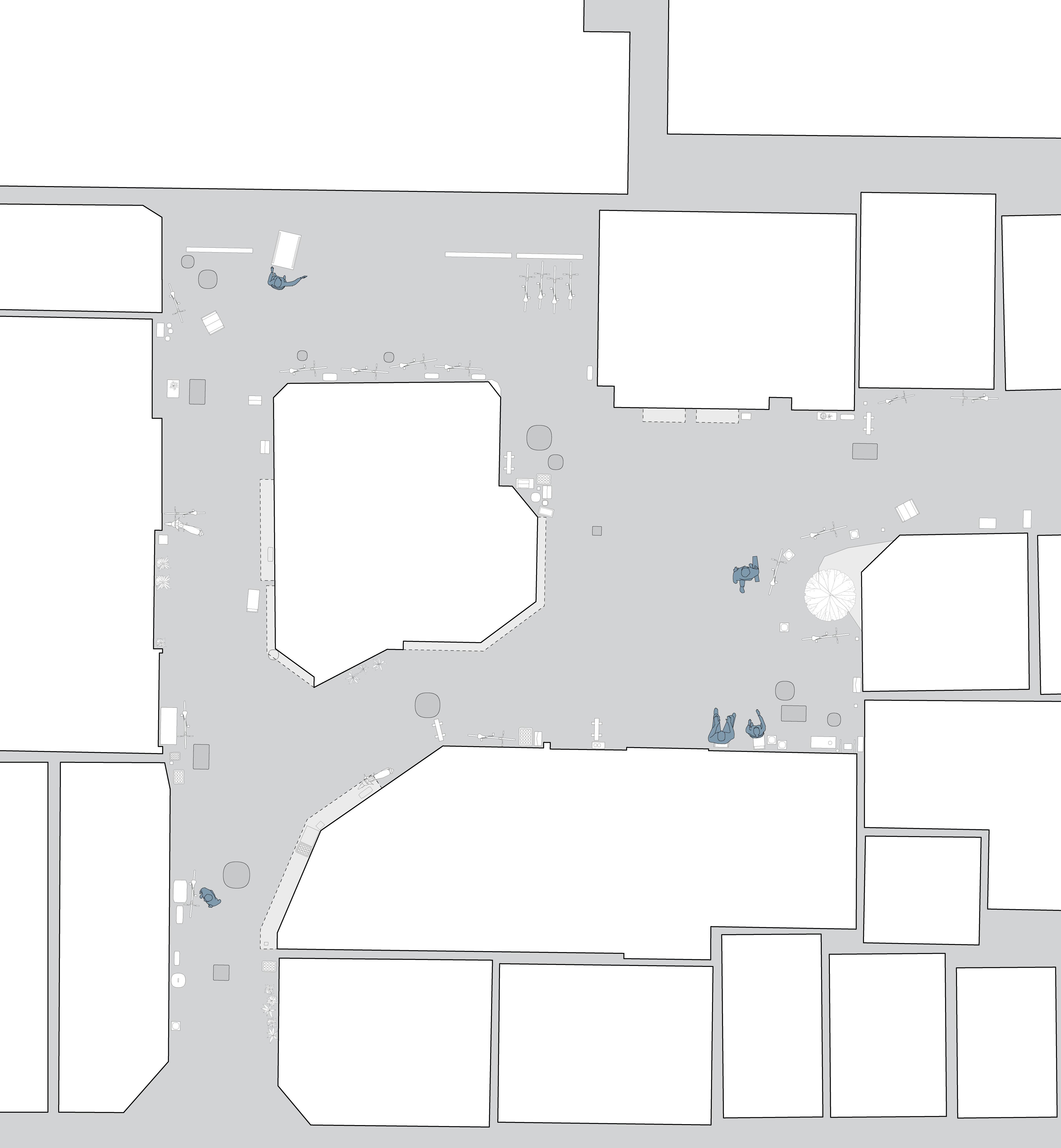

It should be noted the shifting functions of the squares over the years respond to actions by inhabitants and the government. Tai Pei Square and Sam Pei Square later had a park and a basketball court installed respectively, while Yi Pei Square’s current playground was only created in 2021. [22] Sze Pei Square used to be a carpark, until an electricity substation and a rubbish depot were created. [23] The current states of Tai Pei Square and Yi Pei Square are evolved from existing architecture with clear design intents, featuring parks, playgrounds, and resting areas, but also a flexibility to use the open space as temporary

storage. For instance, Tai Pei Square includes a small playground and integrates with an adjacent carpark, serving local residents, store owners transporting goods, and commercial workers seeking rest. Yi Pei Square offers resting benches and a large open playground, particularly used by local children, elderly, and store owners. On the other hand, Sam Pei Square and Sze Pei Square exhibit a more program-specific approach, with little to no designs allowing for informal gatherings. This is evidenced by the fenced-off recreational equipment in Sam Pei Square, separate from the largely vacant corridor of space facing shops. Both Sam Pei Square and Sze Pei Square are often utilised by surrounding businesses for storage and product display, sometimes at the expense of improvised human interaction. Aside from the trash depot in Sze Pei Square, the presence of polystyrene box waste and products from surrounding restaurants and shops spill onto the sides of these squares, creating an even more undesirable social space.

Frequent loading and unloading occur outside valid parking spaces in the car park, servicing shops within the square. Workers sit on the steps in front of shops to the east, while chefs and street cleaners can be seen sitting and napping on benches.The playground to the south is frequented by children, domestic helpers, and the elderly alike. The back alleys are relatively clean, even with construction scaffolding to the wes t.

Section 1:250

Children play sports and games in the redesigned central playground, while adults and elderly sit in the pavilions or on the covered sides of the square. Shops and restaurants line the wider alleyways, while fruit vendors, chefs, and street cleaners mingle in the back alleys, where trash is moved to and from. Roadworks continue in the south.

Park spaces to the north and south of the square are used by the elderly, while covered spaces along the businesses have tables and chairs set up. Styrofoam boxes and dumpster bins can be seen lining wider paths to the east and south. The basketball court is often used from afterschool hours to nighttime.

There are no official recreational spaces within the square, and no seating exists. An electricity substation takes up half the existing space, and dumpster bins, trash bags, and trolleys can be seen everywhere on the south side of the square. The alleyways house few shops, making any occupation of the space by businesses rare, save a newspaper stall to the west. Roadworks occur to the south where backdoors of kitchens are often open.

Plan 1:650

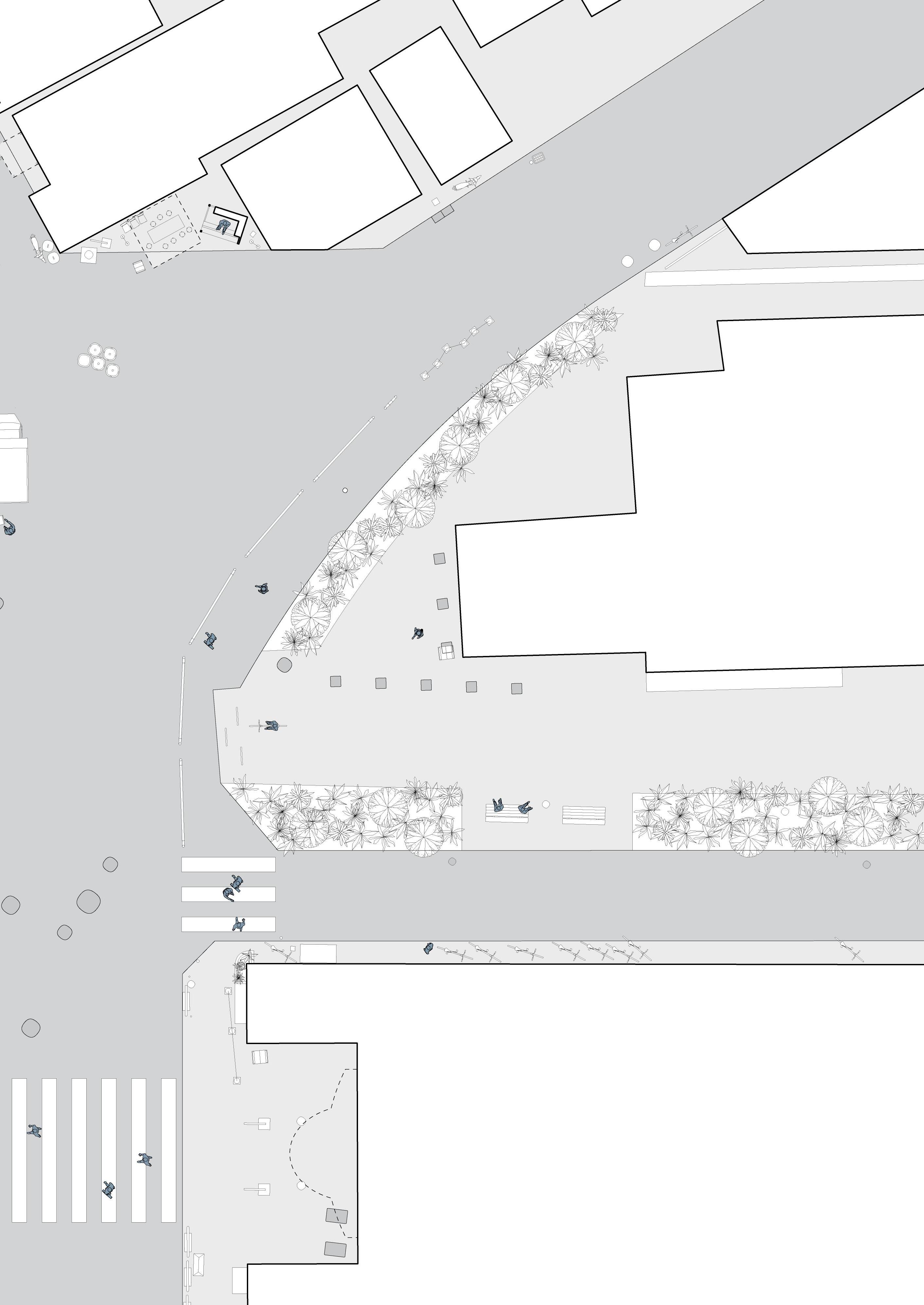

Shimokitazawa, located in the southwest of Tokyo and bounded by Meguro and Shibuya City on the east, is an area of mixed use and residential buildings, with commercial buildings lining the main roads, and residential low-rises one to two blocks away. With a few larger concourses running north-south, and smaller commercial lanes connecting to and complementing them, a tight network of clothing stores, diners, live music venues, and small offices bring local inhabitants and visitors together. The commercial corridors can be seen as harder “egg whites” with a concrete “shell” protecting the lesser-trafficked residential “egg yolks”, a comparison also seen in Popham’s analysis in his book Tokyo: The City at the End of the World . [24] This reduces the separation of residential and commercial land use, allowing local residents to mingle with visitors in public spaces.

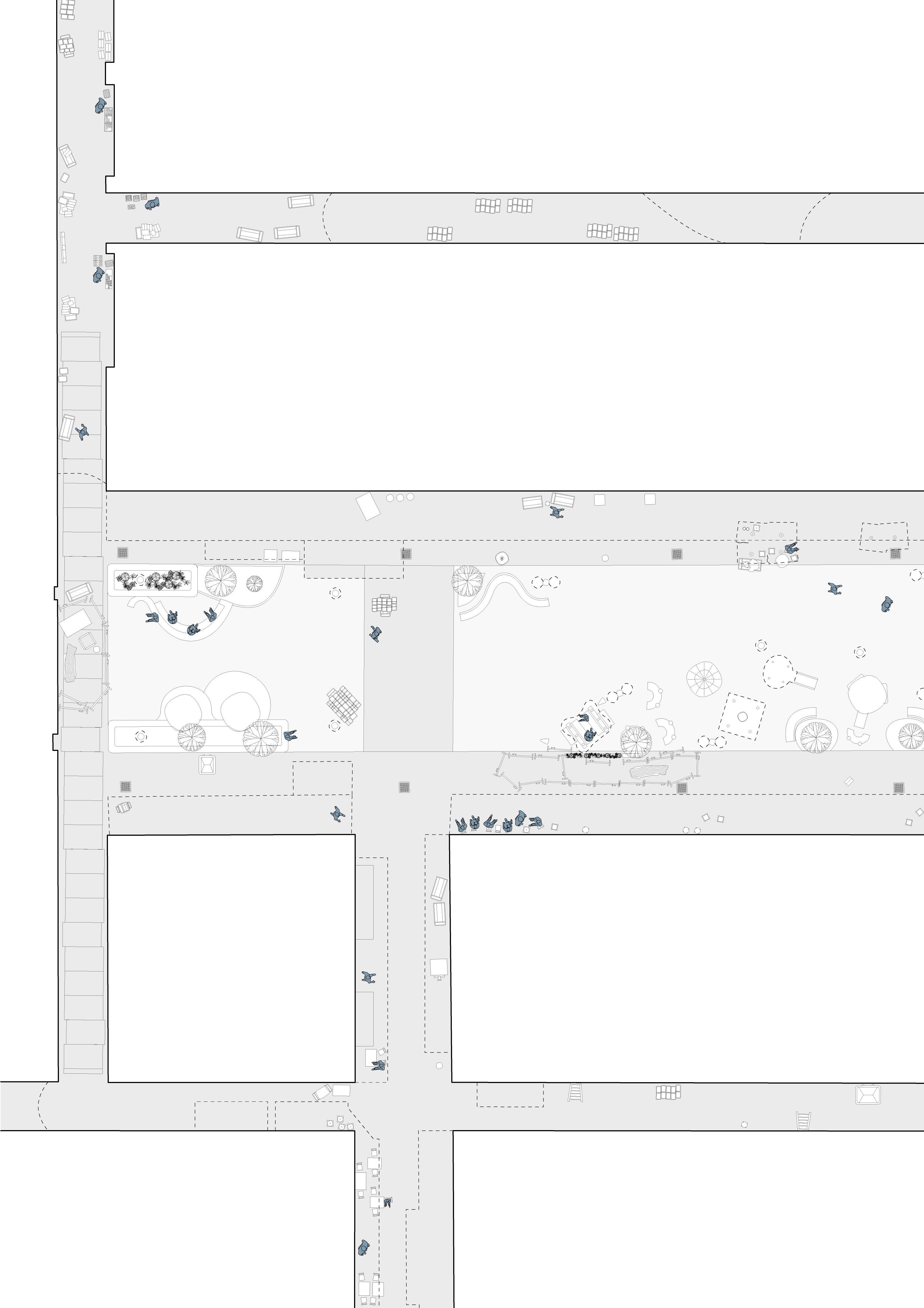

Is it a Pedestrian Zone?

Shimokitazawa takes its name from Shimokitazawa Village, located in the south of the district of Kitazawa, hence the prefix shimo- , which means “lower”. While the village no longer exists, it used to be a rural area with rice paddies, until small shops began to congregate around the railway station when it opened in 1927. [25] The post-war economic recovery of Japan only encouraged more people to move in, and development of residential blocks started as early as 1948, alongside the development of tin-roofed businesses as well. [26] With a lack of high-rise commercial development, residential and commercial expansion continued, but the plot sizes stayed relatively small with low rent, appealing to independent businesses. However, public spaces and road networks were rarely renovated or widened to keep up with development, so the narrow streets of

Shimokitazawa today limit vehicular traffic and have no curbs, encouraging pedestrians to spill onto the roads themselves and reclaim public access.

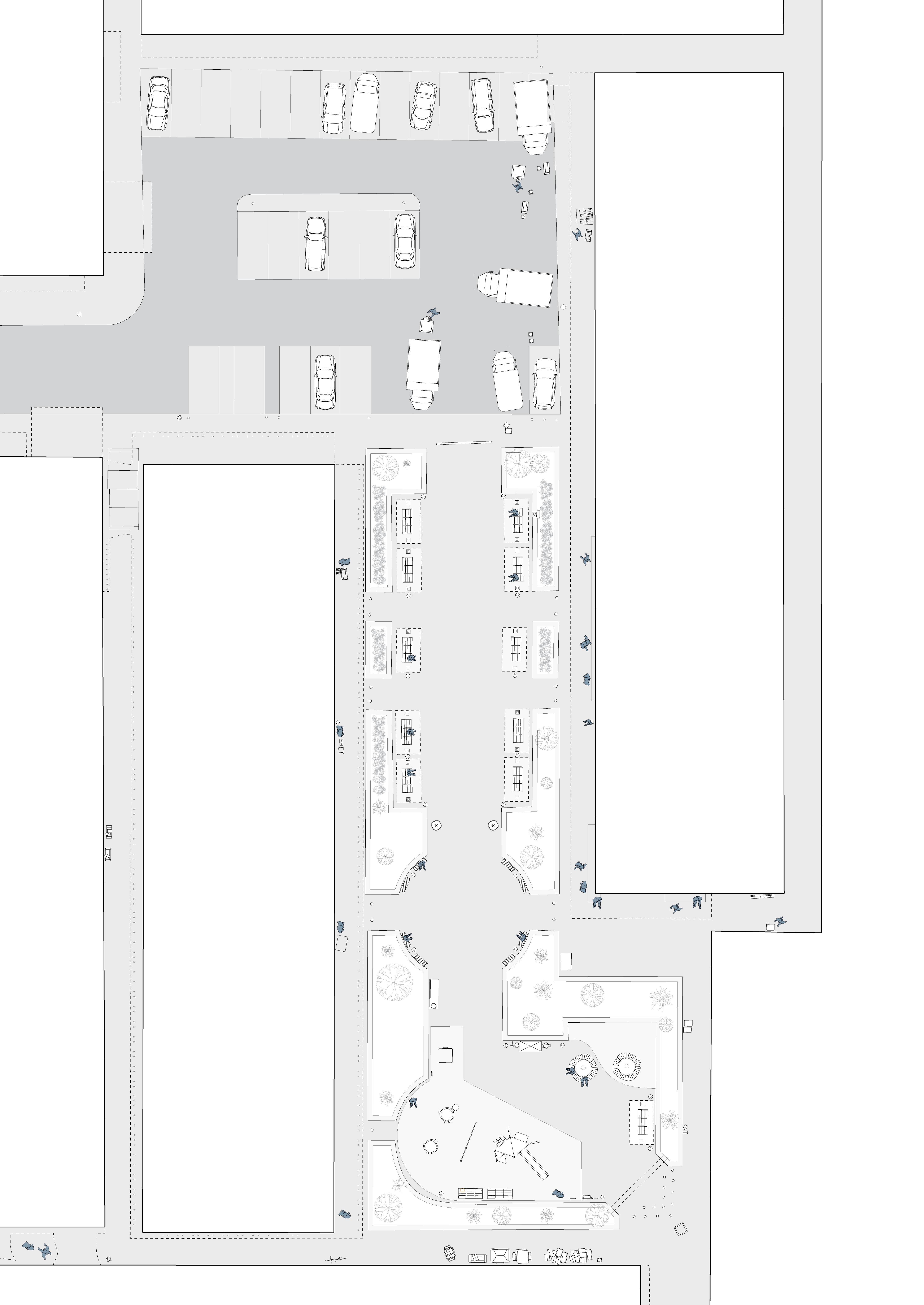

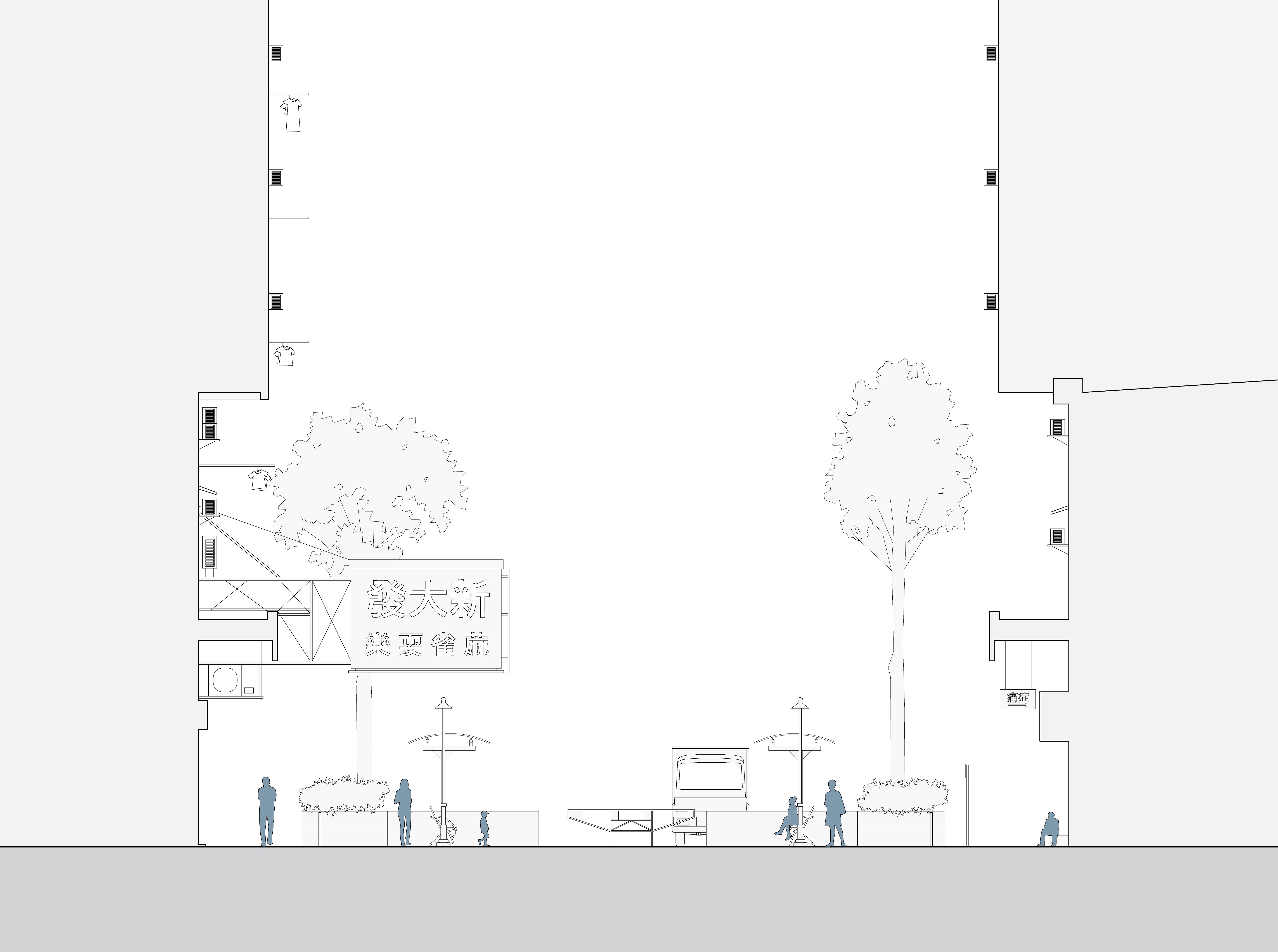

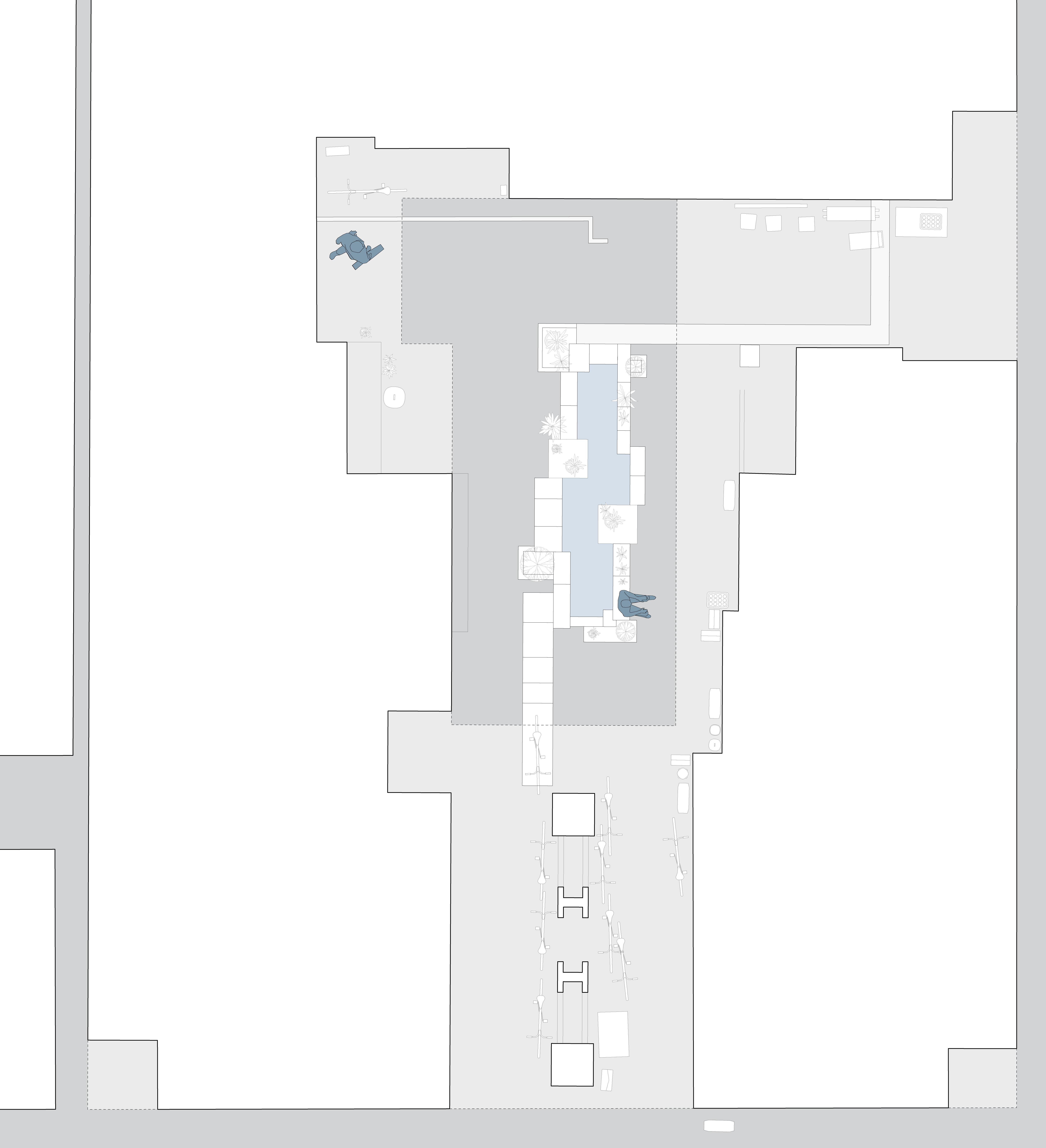

The public inhabitation of spaces in Shimokitazawa showcase a diverse interplay between formal design and informal usage, creating multifaceted urban spaces that serve various functions. The large Senrogai Open Space exemplifies intentional design elements, such as benches at crossings and a loosely-defined open event space with seating and food trucks, catering to students, visitors, and locals for rest and gatherings. In contrast, the Kōshindō Shrine Intersection demonstrates a more organic development, where minimal pedestrian infrastructure leads to people spilling into vehicular traffic, and surrounding shops extend their products onto the streets, creating informal sitting and shopping spaces. This intersection also uniquely houses a shrine, adding a sacred element to the famous bustling urban environment. The Sazan Ishii Building Intersection is further up the shopping street, and represents a transition zone between commercial and residential areas, with store products encroaching on the junction while residential houses are fully in view. Lastly, the cafe seating area in front of 2 chomē -33-6 illustrates how private businesses contribute to public space, with tables and chairs extending al fresco onto the sidewalk on both sides of the road in a T-shaped junction. These examples highlight how daily activities shape these spaces, from shopping and dining to commuting and socialising, often blurring the lines between designated uses and creating multifunctional urban environments that adapt to the needs of their users.

The central open space has seating for those who buy from the cafe and food trucks, but is also open to the public, with makeshift gates acting as barriers to its north and south. Vehicular entrance to the shopping streets in the west are blocked from 16:00 to 18:00 on weekdays, and even longer on holidays. Deliveries by truck happen spontaneously on the side of the road in the junction.

Pedestrians heading north leave the ending sidewalk and spill onto the street after this junction. Shoppers frequent the clothing stores on both sides of the north-south shopping street, while salarymen walk to and from the station quickly. Cyclists and motorcyclists park their vehicles to the side alleys. The shrine in the centre is usually undisturbed unless there is a religious event.

Shoppers frequent the clothing shops in and around the acute corner condition of this intersection. More eateries line the road in this portion of the shopping street, which pedestrians take up completely unless there is a slow passing vehicle. A house with a front yard is located immediately to the west of this intersection, marking the start of the residential area with little to no shops.

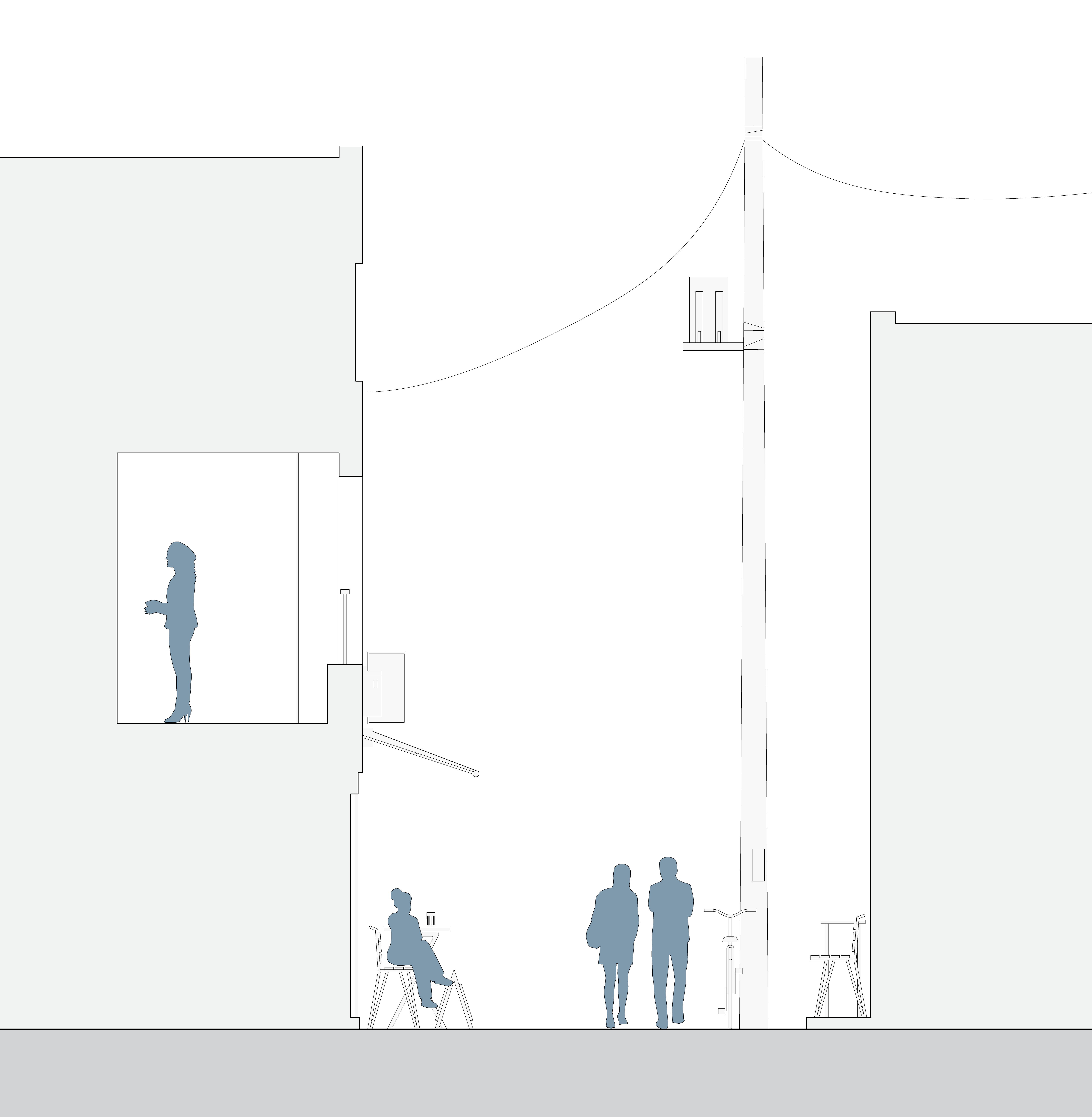

The seating of the smoking cafe at the centre of this junction takes up both sides of the alleyway. 6-8 tables are set up, some under canvas coverage and some not, but mostly filled. The pathway is frequented by shoppers and commuters alike as a shortcut. Bicycle parking occurs further away from the junction on all sides, and an empty lot is overgrown with plants. The main road continuing north of this junction is also closed to vehicles from 16:00 to 18:00 on weekdays.

Section 1:75

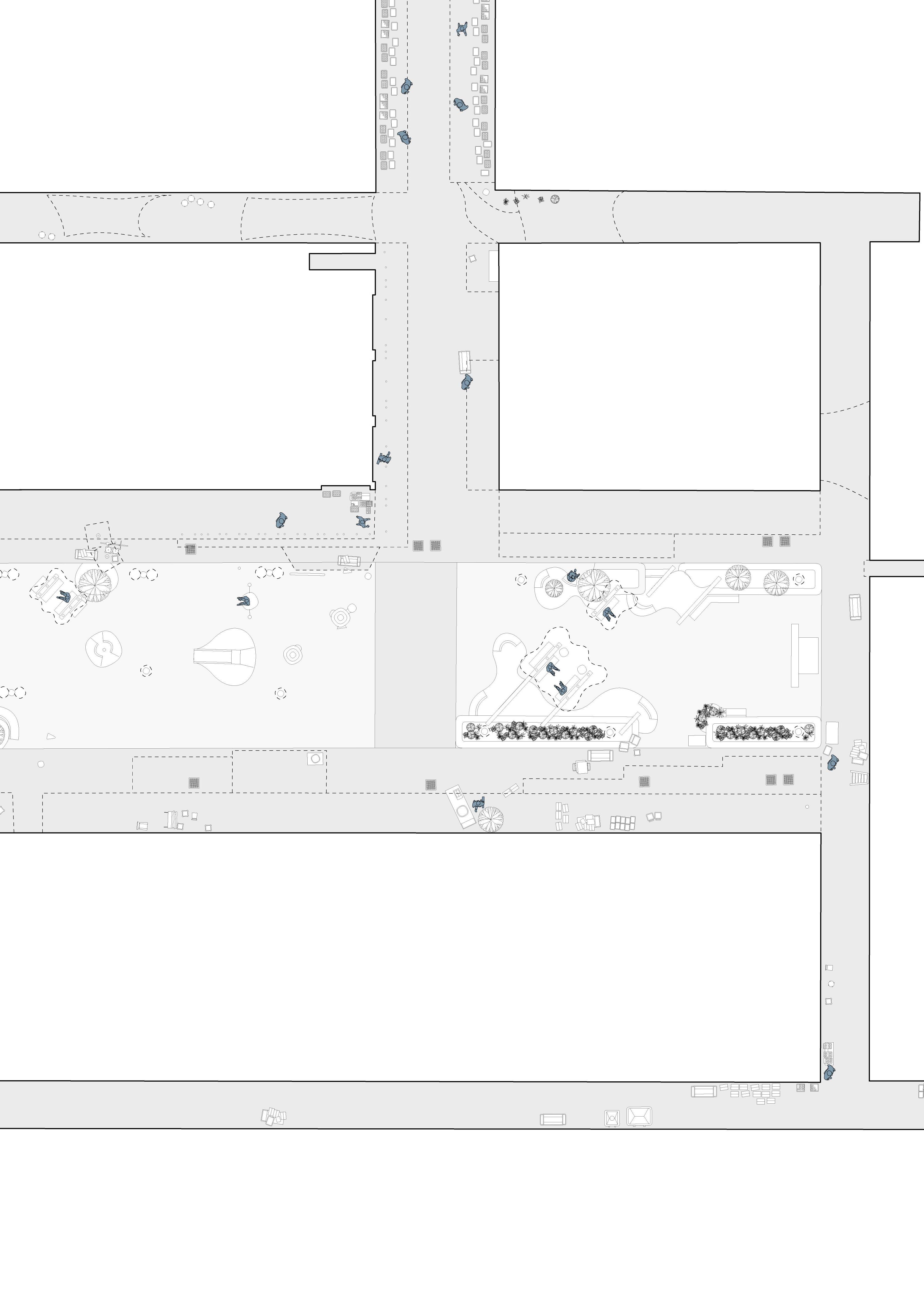

Crossroads of the Yokochō

Nakano is the central neighbourhood of the second-most densely populated city in Japan, Nakano Ward. [27] The area of interest is the commercialised district around the north side of the main railway station, and contains small businesses within a network of narrow commercial alleys, or yokochō , in its 5th chomē . Unlike the short boundary between residential and commercial buildings just one to two blocks away from the main road in Shimokitazawa, residential areas in Nakano are further dispersed away from the main roads, while buildings within the commercialised premises predominantly function as business spaces. Although all the cases chosen from both sites are low to mid-rise, Nakano is more developed with multiple cases of commercial and civic high-rises, with a focus along the main commercial corridor, Fureai Road.

With an agricultural history, Nakano started development during the postwar period, with a rather large area of squatters settling to the northeast of the main railway station. With some industrial development and a relatively weak road network, the area started to reorganise and redevelop itself from the 1960s into regulated small shopping streets with bars, cafes, and restaurants, also known as shotengai , forming the yokochō we know today. Notably, a long shopping street and a small scale mall complex, both landmarks to the north of the railway station, were completed in 1958 and 1966 respectively. [28] Up till today, a lot of residential buildings three to four blocks away from the commercial districts are low-rise, and are still constructed with wood. Alongside the late arrival of medium to high-rise commercial development, the low rent and cultural diversity of Nakano has attracted younger inhabitants to and around the yokochō , enhancing the liveliness of public spaces. [29]

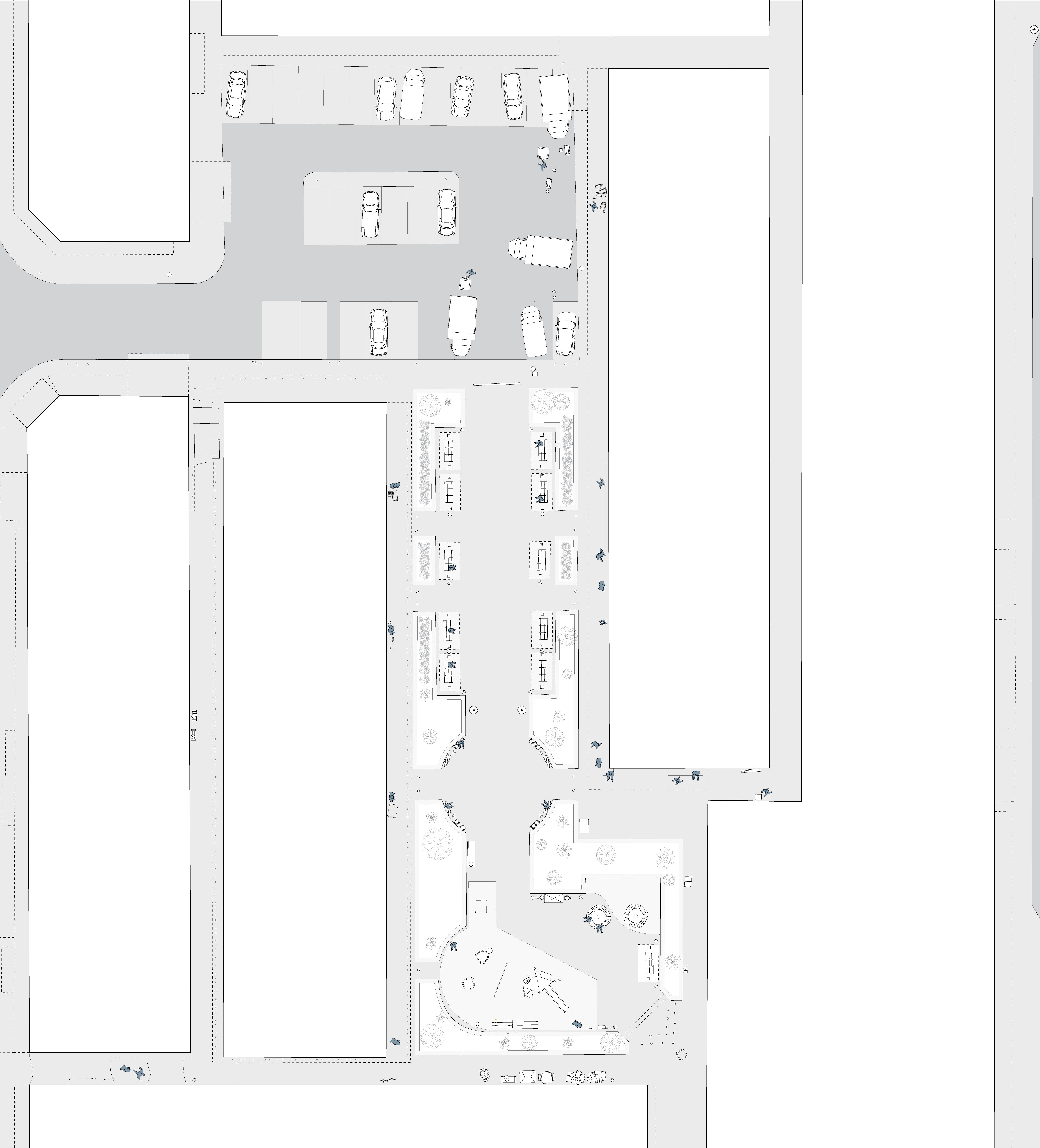

The adaptability and multifunctionality of small and narrow intersections show how yokochō can accommodate a variety of daily activities and informal uses. The two intersections on Fureai Road exemplify how narrow junctions become extensions of surrounding businesses, with eatery seating spilling out onto the streets. They also separately serve as an impromptu public smoking area and an informal bicycle parking space within a non-parking zone, highlighting the rulebending use of limited space. The Shin-Nakamise Shotengai alleys further illustrate this versatility, featuring a central block with multiple eatery stalls, surrounded by cafes and restaurants. This space not only serves as a dining area but also provides both legal and improvised parking for bicycles and a resting space for renovation workers, demonstrating its adaptability to various needs. In contrast, the courtyard of Lions Court, while designed as a formal semi-public space with a pond and benches, sees less public use due to its secluded nature. However, it still finds purpose as a storage area for shop owners, scattered bicycle parking throughout afternoons and evenings, and even as a photoshoot booth for products, showcasing how even intentionally designed spaces can be repurposed to meet practical needs. These examples highlight how daily activities, from dining and smoking to bicycle parking and informal storage, shape and redefine urban spaces, carrying the informality of squatter areas into a formalised setting.

Intersection on Fureai Road of 5 chomē -56-15

This intersection in the north faces a supermarket on Fureai Road with frequent deliveries of goods, while the side alley is filled with eateries occupying the street space with tables and chairs for al fresco dining and smoking. Bicycles come and go, while the number of tables and chairs increases as the night progresses.

Intersection of Go-ban Gai and Fureai Road 5 chomē -56-16

The side alley of Go-ban Gai is less busy than the one to its north, but around 10 bicycles are parked in an area with clear "no parking" signs. Traffic cones attempt and fail to prevent parking along the north side of the alley. Some tables and chairs are set up along the south.

This shotengai is a courtyard condition with access to the main alleys through paths to its northeast and southeast. Bicycle parking occurs along fenced off areas that do not allow parking, notably around the tree in the east. Shop owners arrive in the day by bicycle and on foot and set up their shops by nighttime. Construction workers sit on trolleys to rest around the area, with construction in the west and east.

A courtyard open to public under a private apartment, featuring a few shops, and a pond with plants in the centre. Bicycles are parked in the tunnel to the south where multiple "no parking" notices have been put up. Storage containers, shelves, and chairs line the walls to the north and east, while residents and shop owners come and go by bicycle. A man comes in from the outside and takes photos of his products by t he pond.

Tranquility in the evening with illegally-parked bicycles

[1] Charlie Q. L. Xue and Kevin K. K. Manuel, “The Quest for Better Public Space: A Critical Review of Urban Hong Kong,” essay, in Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001), 173–85, 173.

[2] Jorge Almazán and Joe McReynolds, Emergent Tokyo: Designing the Spontaneous City (Novato, CA: ORO, 2021), 13.

[3] “Urban Population (% of Total Population) - Hong Kong SAR, China,” World Bank Open Data, accessed June 26, 2024, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL. IN.ZS?locations=HK.

[4] Almazán and McReynolds, Emergent Tokyo , 12.

[5] 都市デザイン研究体 [Urban Design Research Collective], 日本の都市空間 [Japanese Urban Space] (Tokyo: Shokokusha, 1968).

[6] Xue and Manuel, “Better Public Space,” 173.

[7] Hidenobu Jinnai, “The Waterfront as a Public Space in Tokyo,” essay, in Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001), 49–64, 51.

[8] Xue and Manuel, “Better Public Space,” 175; Hikaru Kinoshita, “The Street Market as an Urban Facility in Hong Kong,” essay, in Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001), 78–86, 82-86.

[9] Tanya Hidaka and Mamoru Tanaka, “Japanese Public Space as Defined by Event,” essay, in Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001), 107–18.

[10] Almazán and McReynolds, Emergent Tokyo , 206-17.

[11] Almazán and McReynolds, Emergent Tokyo , 206-17.

[12] Xue and Manuel, “Better Public Space,” 181-85.

[13] Kinoshita, “The Street Market,” 82-86.

[14] Almazán and McReynolds, Emergent Tokyo , 25.

[15] Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Publishing Group LLC, 2023).

[16] Almazán and McReynolds, Emergent Tokyo , 5.

[17] Old Survey Sheets 1:1200 , map (Hong Kong: Land and Survey Office, 1960).

[18] China: Kowloon and Part of New Territory, Surveyed in 1902-1903, 8 Inch to One Mile , map (Hong Kong: Public Records Office HK Library HK Survey and Mapping Office, 1924); Christopher Dewolf, “A Colourful Cure for What Ails Hong Kong’s Grey Public Spaces,” Zolima City Magazine, June 3, 2021, https://zolimacitymag.com/colourfulcure-hong-kong-public-spaces-playground-square-yi-peisquare/.

[19] Orthophoto 3900 Ft. , photograph, Hunting Surveys (Hong Kong: Government of Hong Kong, 1963).

[20] Old Survey Sheets 1:1200 , map (Hong Kong: Land and Survey Office, 1975).

[21] DOP1000 Digital Orthophoto , photograph (Hong Kong: Lands Department, 1982).

[22] Dewolf, “A Colourful Cure.”

[23] Old Survey Sheets 1:1200 , map (Hong Kong: Land and Survey Office, 1975).

[24] Peter Popham, Tokyo: The City at the End of the World (La Vergne: Camphor Press Ltd, 2021), 48.

[25] Southwest Tokyo 1929 Railway Supplement 1:50,000 , 1929, map, 1929.

[26] “【東京の記憶】 下北沢駅前食品市場 / トタン屋根 街 の台所 / 路地に70店 再開発で解体 [[Tokyo Memories] Shimokitazawa Station Food Market / Tin Roof, City Kitchen / 70 Stores in the Alley, Demolished for Redevelopment],” 読売新聞 [Yomiuri Shimbun] , December 25, 2017.

[27] “ 全国の区(特別区・政令区)[Wards Nationwide (Special Wards and Designated Wards)],” 【全国の区(特別区・政令 区)】 人口ランキング・面積ランキング ・ 人口密度ランキング [Wards nationwide (special wards and designated wards) Ranking by population, area and population density], January 1, 2024, https://uub.jp/rnk/k_j.html.

[28] “ 中野区 商店街 中野サンモール商店街振興組合 のことな ら中野区商店街ナビ [Nakano Ward Shopping District Nakano Sun Mall Shopping District Promotion Association],” 中野 区商店街ナビ [Nakano Ward Shopping District Navigator], accessed June 26, 2024, https://www.heart-beat-nakano. com/street/48.html.

[29] “ 中野ブロードウェイ公式サイト [Nakano Broadway Official Website],” 中野ブロードウェイ [Nakano Broadway Official Site], accessed June 26, 2024, https://nakanobroadway.com/.

Almazán, Jorge, and Joe McReynolds. Emergent Tokyo: Designing the spontaneous city . Novato, CA: ORO, 2021.

“China: Kowloon and Part of New Territory, Surveyed in 1902-1903, 8 Inch to One Mile.” Map. Hong Kong: Public Records Office HK Library HK Survey and Mapping Office, 1924.

Dewolf, Christopher. “A Colourful Cure for What Ails Hong Kong’s Grey Public Spaces.” Zolima City Magazine, June 3, 2021. https://zolimacitymag.com/colourful-cure-hongkong-public-spaces-playground-square-yi-pei-square/.

DOP1000 Digital Orthophoto . Photograph. Hong Kong: Lands Department, 1982.

Hidaka, Tanya, and Mamoru Tanaka. “Japanese Public Space as Defined by Event.” Essay. In Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies , 107–18. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001.

Jinnai, Hidenobu. “The Waterfront as a Public Space in Tokyo.” Essay. In Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies , 49–64. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001.

Kinoshita, Hikaru. “The Street Market as an Urban Facility in Hong Kong.” Essay. In Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies , 78–86. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001.

“Old Survey Sheets 1:1200.” Map. Hong Kong: Land and Survey Office, 1960.

“Old Survey Sheets 1:1200.” Map. Hong Kong: Land and Survey Office, 1975.

Oldenburg, Ray. The Great Good Place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a Community . Great Barrington, MA: Berkshire Publishing Group LLC, 2023.

Orthophoto 3900 ft . Photograph. Hunting Surveys. Hong Kong: Government of Hong Kong, 1963.

Popham, Peter. Tokyo: the city at the end of the world . La Vergne: Camphor Press Ltd, 2021.

“Southwest Tokyo 1929 Railway Supplement 1:50,000.” 1929. Map.

“Urban Population (% of Total Population) - Hong Kong SAR, China.” World Bank Open Data. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL. IN.ZS?locations=HK.

Xue, Charlie Q. L., and Kevin K. K. Manuel. “The Quest for Better Public Space: A Critical Review of Urban Hong Kong.” Essay. In Public Places in Asia Pacific Cities: Current Issues and Strategies , 173–85. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001.

“【東京の記憶】下北沢駅前食品市場/トタン屋根 街の台所/ 路地に70店 再開発で解体 [[Tokyo Memories] Shimokitazawa Station Food Market / Tin Roof, City Kitchen / 70 Stores in the Alley, Demolished for Redevelopment].” 読売新聞 [Yomiuri Shimbun] , December 25, 2017.

“ 中野ブロードウェイ公式サイト [Nakano Broadway Official Website].” 中野ブロードウェイ [Nakano Broadway Official Site]. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://nakano-broadway. com/.

“ 中野区 商店街 中野サンモール商店街振興組合 のことなら 中野区商店街ナビ [Nakano Ward Shopping District Nakano Sun Mall Shopping District Promotion Association].” 中野 区商店街ナビ [Nakano Ward Shopping District Navigator]. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.heart-beat-nakano. com/street/48.html.

“ 全国の区(特別区・政令区)[Wards Nationwide (Special Wards and Designated Wards)].”【全国の区(特別区・政令区) 】人口ランキング・面積ランキング・人口密度ランキング [Wards nationwide (special wards and designated wards) Ranking by population, area and population density], January 1, 2024. https://uub.jp/rnk/k_j.html.

都市デザイン研究体 [Urban Design Research Collective]. 日 本の都市空間 [Japanese Urban Space]. Tokyo: Shokokusha, 1968.