9 minute read

Project Brighten: A Solar Energy Initiative in the Slums of Mumbai by Anna Abramova, Sophie Gaudreau, Shaydah Ghom, and Ilsa Weinstein-Wright

Abstract

Every year, the External portfolio of the IDSSA supervises the International Development Policy Case Competition (IDPCC), McGill University’s first interdisciplinary policy-building case competition that focuses on development issues. As a journal showcasing the most compelling undergraduate research taking place at McGill, Chrysalis typically published the competition’s winning policy brief. However, due to a reconfiguring of the IDPCC timeline, the past two years have not been able to feature a collaboration with the competition. As this year’s Editor-in-Chief, I am proud to bring back the IDPCC’s winning team to our journal. The 2021 edition of the case competition was supervised by the VP External, Will Croke-Martin, in collaboration with the McGill Policy Association (MPA), on the theme of housing and standards of living. The winning team presented “Project Brighten”, a solar panel project aiming to improve access to electricity services in the slums of Mumbai.

Advertisement

Résumé

Chaque année, le portfolio externe de l’IDSSA supervise le Concours d’Études de Cas sur les Politiques de Développement International (IDPCC), le premier concours interdisciplinaire au sein de l’Université McGill axé sur les questions de développement. En tant que revue présentant les travaux de recherche les plus remarquables menés à McGill, Chrysalis publiait généralement le dossier politique gagnant du concours. Toutefois, en raison d’une reconfiguration du calendrier de l’IDPCC, les deux dernières années n’ont pas été marquées par une collaboration avec le concours. Cependant, en tant que votre rédacteur-en-chef cette année, je suis fier de ramener l’équipe gagnante de l’IDPCC dans notre journal. L’édition 2021 du concours de cas a été supervisée par le VP aux affaires externes, Will Croke-Martin, en collaboration avec la McGill Policy Association (MPA), sur le thème du logement et du niveau de vie. L’équipe gagnante a présenté “Project Brighten,” un projet de panneaux solaires visant à améliorer l’accès aux services d’électricité dans les bidonvilles de Mumbai.

The Problem Poor Electricity Services in Urban Slums in Mumbai

The lack of reliable and affordable access to electricity is a significant challenge affecting slum dwellers across Mumbai: the city’s slums are characterized by insecure residential status, poorly built housing, and overcrowding.1 In this context, slum dwellers either do not have electricity, share a meter with a neighbor, or illegally acquire electricity through cartels.2 Nonetheless, the prevalence of illegally-sourced electricity in slums has more costs than benefits. Indeed, cartels generally (1) inflate the electricity prices, (2) disregard safety protocols resulting in a higher risk for electrocution and/or fires, and (3) overload the main network.3 With the projected population growth of Mumbai in the coming years, the energy demand is likely to drastically increase.4 Therefore, finding an affordable and sustainable solution to this problem is crucial. Supply and Demand Side Challenges Supply side challenges such as lack of house ownership status, address invalidity, and precarious housing construction result in slum dwellers’ inability to access improved electricity. Demand side challenges include both tangible and intangible factors, such as the price (cost of connection and consumption fees) and fear of retaliation from local leaders, respectively. The resulting situation means low demand for improved electricity, thus the illegal provision of electricity through unlicensed electricians and local cartels. Indeed, the problem of both these challenges is that the price of electricity is inflated, there are immense safety issues, and the main network, which serves both formal and informal electricity connections, is overloaded.

The Solution

Project Brighten Project Brighten seeks to provide slum dwellers with safe, affordable, and sustainable access to electricity through the promotion of solar energy. India has an incredible capacity for solar energy production since the country receives nearly 300 days of sunshine per year.5 Additionally, there is significant potential for rooftop solar as most of the structures are of a low-height with a more horizontal spread.6 The scope of the initiative will cover the Dharavi slum of Mumbai.

Implementation Process

Project Brighten seeks to address both demand and supply-side issues related to the adoption of solar energy solutions. Phase One (1 year) Conduct an initial market assessment in Dharavi and design a business model to ensure successful adoption of the solar industry and to increase social development. Phase Two (1 year) Provide technical resources and skills training to local entrepreneurs and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) within the pre-existing solar industry. Phase Three (1 year) Develop and deliver outreach and awareness activities to highlight the health and environmental benefits of solar energy. Phase Four (2 years) Work with local entrepreneurs and SMEs to provide selected households with solar panels to stimulate the baseline market. Households who make their livelihood/income-generating activities within the home will be prioritized. Phase Five (2 years) Assist with the development of financial mechanisms to facilitate the acquisition of solar panels by slum dwellers in the future. Potential models for these include households paying an initial down payment for the product, and subsequently selling their excess solar energy to pay back money owed.

Stakeholders

The Mumbai Branch of the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) is non-profit public interest research and advocacy organization.7 The CSE will play a key role in Phase One, as it will help conduct a detailed and objective evaluation of the potential for solar energy in Dharavi.8

The National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and the Sadak Chhap (Street Children’s Federation) are large non-governmental organizations (NGOs) based in Mumbai who will play crucial roles in Phase Three, as they can help conduct awareness activities and outreach with slum dwellers. They will be able to communicate local electricity needs and ensure the intervention reflects local demands.

Sun King is a pre-existing solar energy business based in India. We seek to invest and work with them, and other similar companies, to distribute safe and affordable solar power to households, as outlined in Phase Two. This partnership will also increase local jobs significantly.

Mahila Milan is a “decentralized network of poor women’s collectives that manage credit and savings activities in their communities”.9 We will partner with them to ensure Phase Five meets local financial demands and ensures household agency.

India’s Ministry of Power will be involved throughout the entire project and will provide guidance and support. They will help us understand the obstacles and successes of past interventions to ensure a successful long-term transition towards solar energy. Inhabitants of Dharavi are the stakeholders who will be most affected by this intervention. As such, their voices must be elevated throughout each phase of the project. Their needs will be communicated to Global Affairs Canada through the numerous local stakeholders involved in the project.

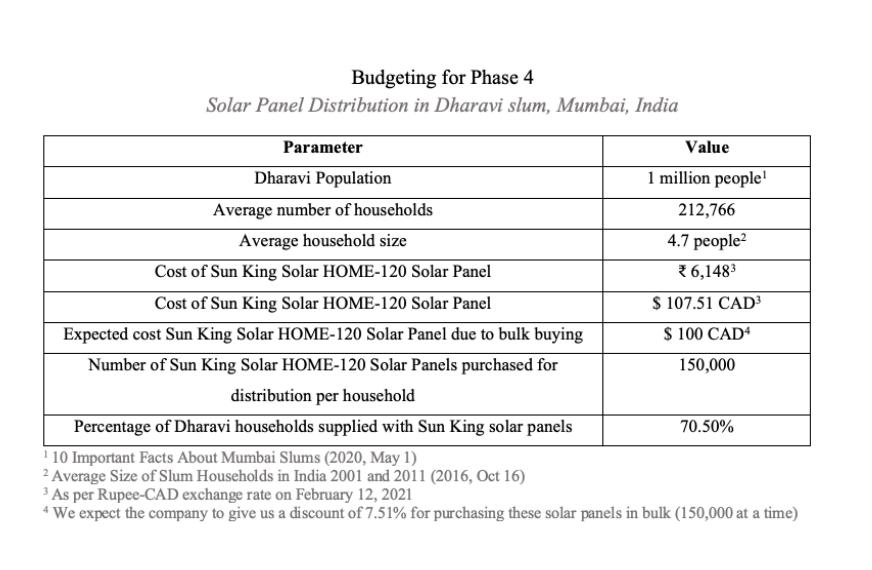

Budget

Total Budget: $25,000,000 CAD

Potential Barriers

Potential barriers to Project Brighten stem from the fact that slums are inherently atypical markets characterized by theft, informality, social exclusion, information asymmetries, and low collection rates. Firstly, to combat theft, we plan on installing the solar panels with theft-proof screws which cannot be unmounted unless special tools are used. Alternatively, panel-embedded smart electronic chips will be used, which lock the panel the moment it is dislodged. Secondly, to address informality and social exclusion, we plan on recognizing the salience of informal interactions by identifying and integrating local leaders into our solution based on trust, especially those who can influence the decision to switch to solar panels. Thirdly, information asymmetries should be prevented by Phase Three of our initiative, which focuses on outreach and awareness activities through locals’ voices and experiences. Finally, low collection rates should be prevented by Phase Five of our initiative, which focuses on micro-financial mechanisms that promote agency and growth of financial capacities.

Looking Forward

Indicators

After five years, we will use various indicators to measure Project Brighten’s success. We will conduct a variety of quantitative and qualitative studies to determine whether these variables have been met. According to UN-Energy, improved energy access should have a positive effect on development indicators, including, well-being, health, and income genertion opportunities.10 Therefore, we will use a quantitative analysis method of Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) to examine, life expectancy, school enrollment, number of respiratory illnesses, and income. Additionally, we will also use qualitative analyses to capture feedback that cannot be measured in numbers. These analyses will be in the form of surveys and interviews with households that are using solar energy.

Sample questions from this survey will include:

“On a scale of 1 to 5, how much do you feel solar energy has positively impacted your life?”

“On a scale of 1 to 5, how do you feel about the air quality in your home?”

“On a scale of 1 to 5, how likely are you to purchase another solar panel for your home?”

“On a scale of 1 to 5, how likely are you to recommend having a solar panel in your home?”

Expanding the Program

Contingent on the success of Project Brighten in Dharavi, a similar business/development model will be expanded to more slums in Mumbai.

Works Cited

Alderslade, Jamie, John Talmage, and Yusef Freeman. 2006. Measuring the Informal Economy One Neighborhood At A Time. Discussion Paper, The Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program.

Average size of slum households in India in 2001 and 2011. 2020. Statista. October 16. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/619587/average-slum-household-size-india/.

Banerjee, Rangan, and Rhythm Singh. 2015. “Estimation of rooftop solar photovoltaic potential of a city.” Solar Energy (Elsevier) 115.

Centre for Science and Environment. 2012. Center for Science and Environment India. https://www.cseindia.org/.

Global Affairs Canada. 2021. Government of Canada | Global Affairs Canada. Accessed February 2021. https:// www.international.gc.ca/global-affairs-affaires-mondiales/home-accueil.aspx?lang=eng.

Kamper, Helena. 2017. 10 FACTS ABOUT MUMBAI SLUMS. The Borgen Project. April 21. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://borgenproject.org/10-facts-mumbai-slums/.

Kay, Ethan. 2012. Saving lives through clean cookstoves. [Video] Filmed at TEDx Montreal.

Mahila Milan. 2014. Sparc India. Accessed Februrary 12, 2021. https://www.sparcindia.org/aboutmm.php.

Mimmi, Luisa M. 2014. “From informal to authorized electricity service in urban slums: Findings from a household level survey in Mumbai.” Energy for Sustainable Development.

Mumbai Population 2021 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs). 2021. World Population Review. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/mumbai-population.

Schaengold, David. 2006. Clean Distributed Generation for Slum Electrification: The Case of Mumbai. Princeton, NJ: Woodrow Wilson School Task Force on Energy for Sustainable Development.

Shukla, Akash Kumar, Sudhakar K., Prashant Baredar, and Rizalman Mamat. 2018.“Solar PV and BIPV System: Barrier, Challenges and Policy Recommendation in India.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 82(P3)https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.013.

SPARC | Home. 2014. Sparc India. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.sparcindia.org/.

Sun King. 2017. Compare Products. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.greenlightplanet.com/comparesun-king/.

The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). 2011. Improving Energy Access to the Urban Poor in Developing Countries. The Energy Sector Management Assistance Program | The World Bank.

Website of Ministry of Power | National Portal of India. 2021. Government of India. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.india.gov.in/official-website-ministry-power.

XE - The World’s Trusted Currency Authority: Money Transfers & Free Exchange Rate Tools. 2021. Currency Converter. February 12. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.xe.com/currencyconverter/convert/?Amount=1&From=INR&To=CAD.