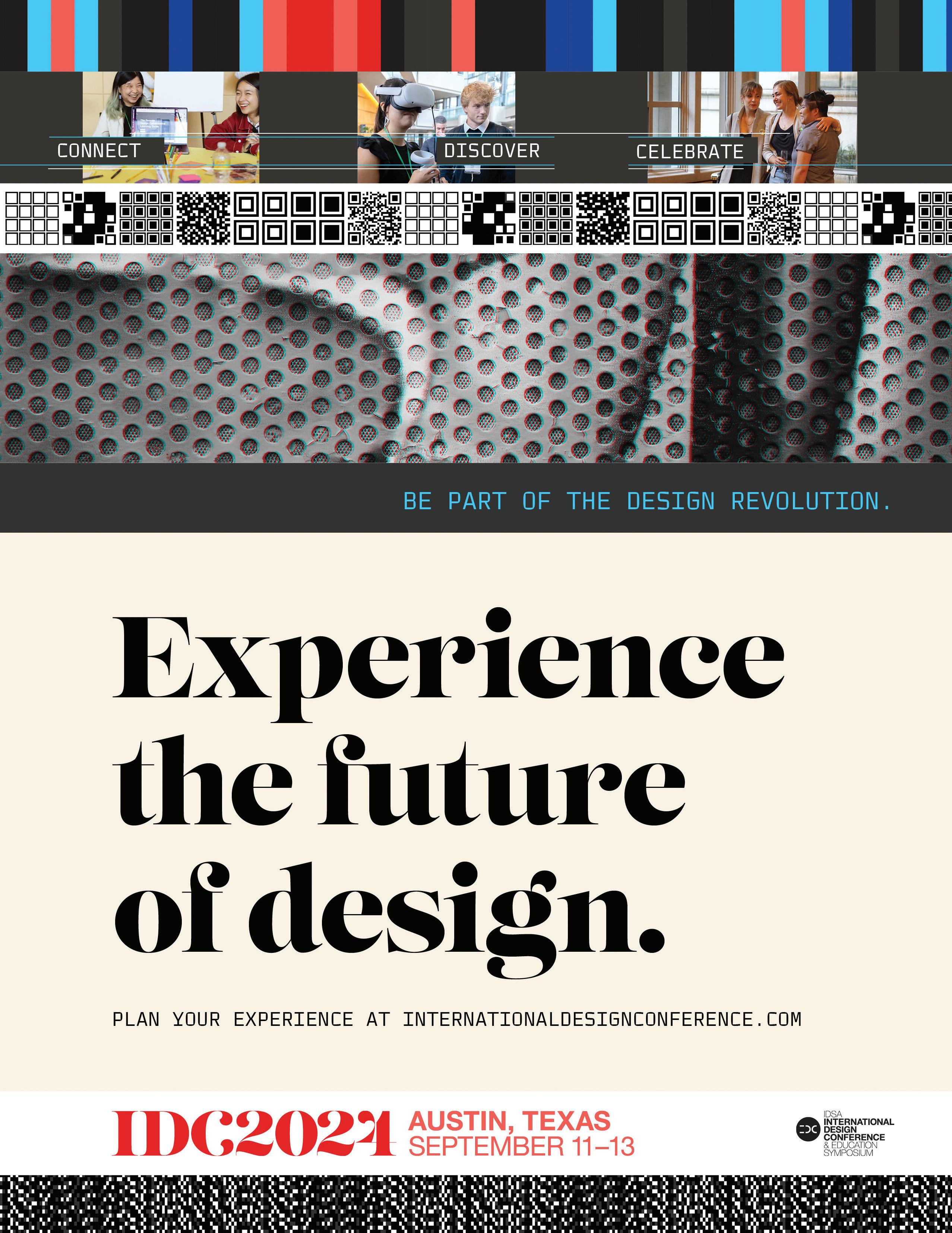

Design, disrupted. BE PART OF THE DESIGN REVOLUTION. PLAN YOUR EXPERIENCE AT INTERNATIONALDESIGNCONFERENCE.COM CONNECT DISCOVER CELEBRATE

Publisher IDSA

1110 Herndon Pkwy. Suite 307

Herndon, VA 20170

P: 703.707.6000 idsa.org/innovation

Publications Committee

Aziza Cyamani, IDSA

Paul Diehl, IDSA

Peter Haythornthwaite, FIDSA

Tucker Viemeister, FIDSA

Contributing Editor

Jennifer Evans Yankopolus jennifer@wordcollaborative.com

Graphic Designers

Nicholas Komor 0001@nicholaskomor.com

Sarah Collins spcollins@gmail.com

Sherri Copeland sherric@idsa.org

Advertising IDSA

703.707.6000 sales@idsa.org

Subscriptions/Copies IDSA 703.707.6000 idsa@idsa.org

IDSA .ORG 2 ® QUARTERLY OF THE INDUSTRIAL DESIGNERS SOCIETY OF AMERICA SPRING 2024 Annual Subscriptions Students $50 Professionals / Organizations Within the US $125 Canada & Mexico $150 International $175 Single Copies Fall $75+ S&H All others $45+ S&H

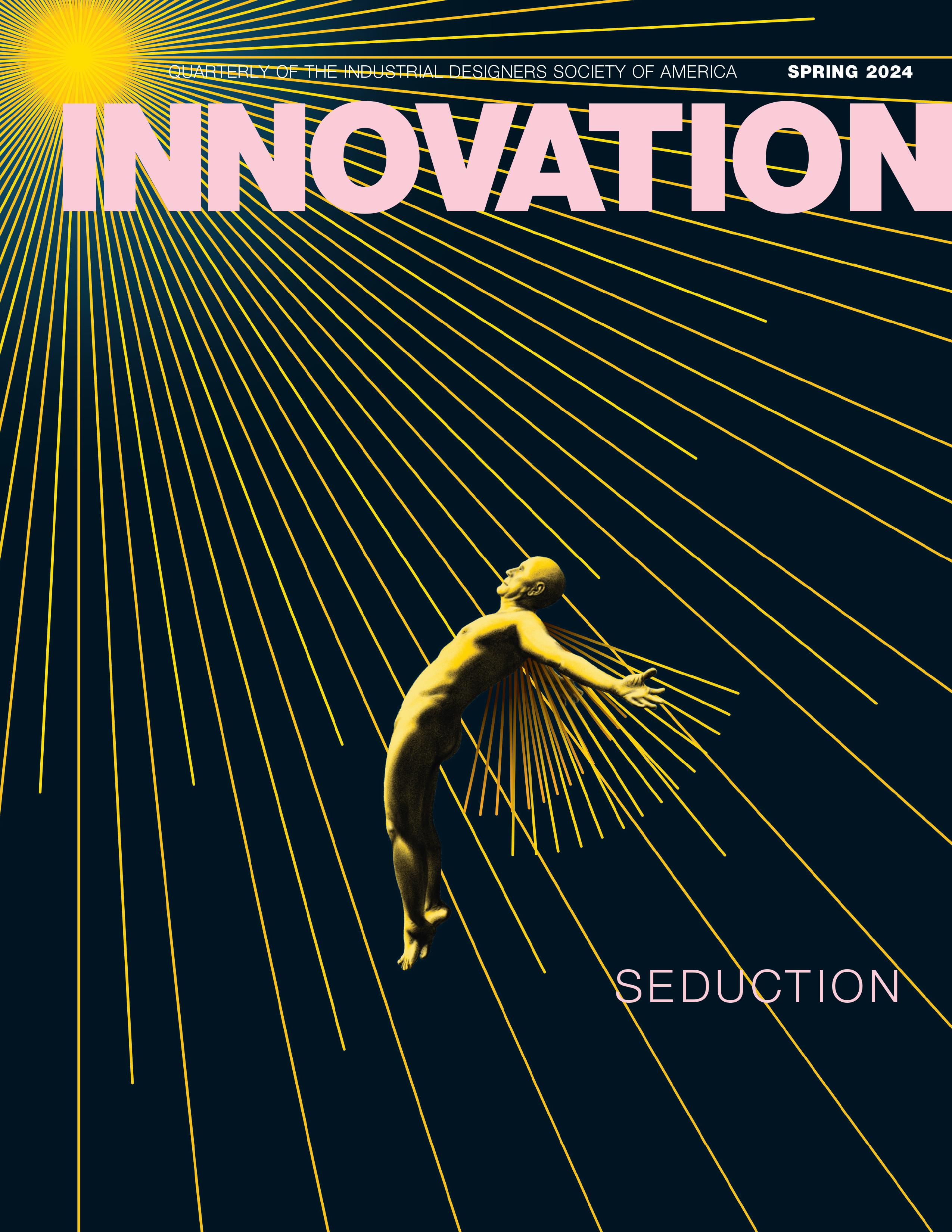

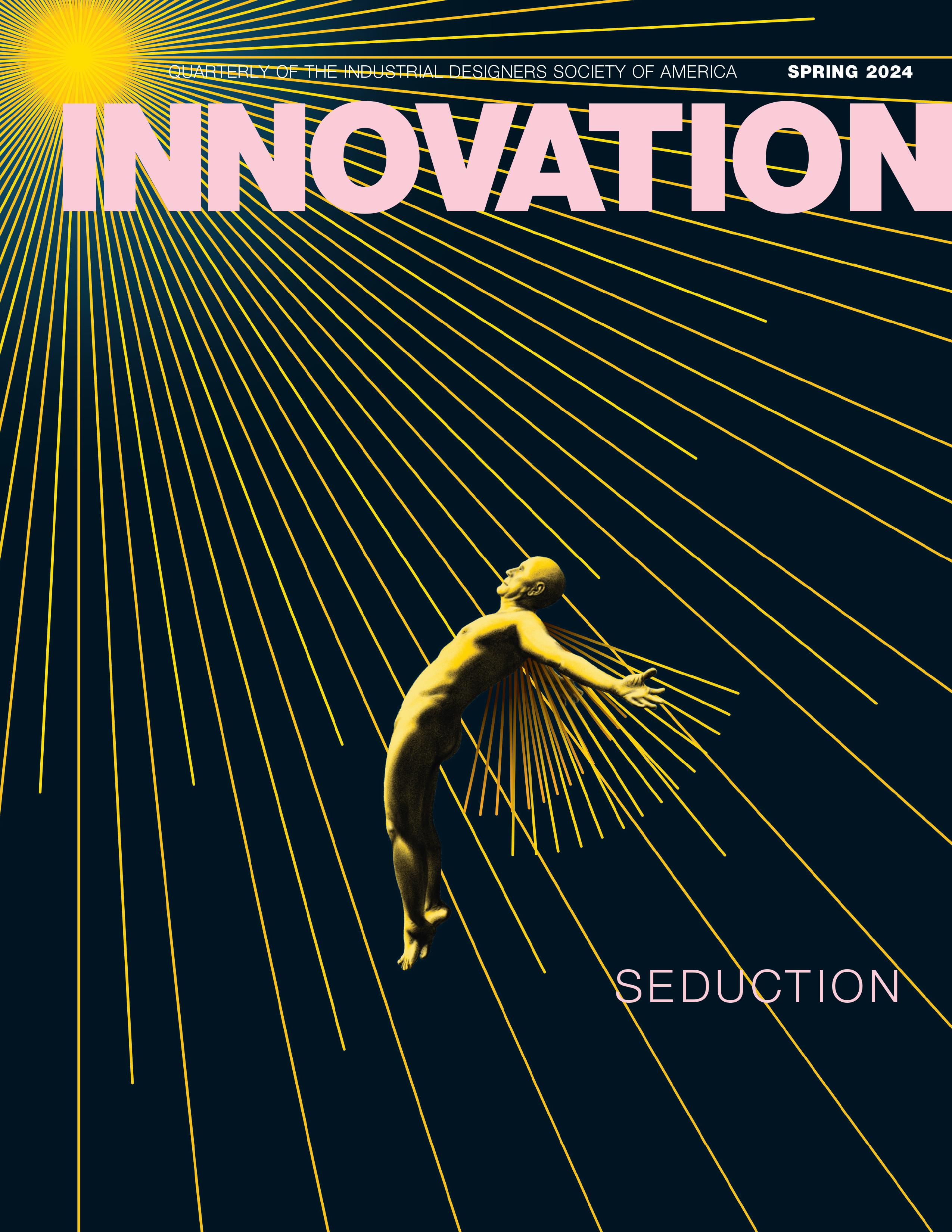

Cover: Is Icarus being seduced by the golden beams of innovation? Or are the beams radiating from a black hole melting the symbolic wings of industrial design? Cover design by Mirko Ilic, https://www.behance.net/MirkoIlic

Above: A water glass that encourages people to drink more water, by Erdem Selek, IDSA, and Hale Selek, IDSA. See page 16. Opposite: A 1950s-style art collage on the theme of seduction, created using Midjourney.

organization serving the needs of US industrial designers. Reproduction in whole or in part—in any form—without the written permission of the publisher is prohibited. The opinions expressed in the bylined articles are those of the writers and not necessarily those of IDSA. IDSA reserves the right to decline any advertisement that is contrary to the mission, goals and guiding principles of the Society. The appearance of an ad does not constitute an endorsement by IDSA. All design and photo credits are listed as provided by the submitter. Innovation is printed on recycled paper with soy-based inks. The use of IDSA and FIDSA after a name is a registered collective membership mark. Innovation (ISSN No. 0731-2334 and USPS No. 0016-067) is published quarterly by the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA)/Innovation, 1110 Herndon Pkwy, Suite 307 | Herndon, VA 20170. Periodical postage at Sterling, VA 20164 and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to IDSA/Innovation, 1110 Herndon Pkwy, Suite 307 | Herndon, VA 20170, USA. ©2023 Industrial Designers Society of America. Vol. 43, No. 1, 2024; Library of Congress Catalog No. 82-640971; ISSN No. 0731-2334; USPS 0016-067.

3 INNOVATION SPRING 2024 SEDUCTION 16 Shiny Objects by Erdem Selek, IDSA, and Hale Selek, IDSA 18 The Art of Temptation by Jayati Sinha, IDSA 22 Touch: The Allure of Tangible Design by Sheng-Hung Lee, IDSA 26 CMF: Designed to Seduce by Daniela García García 30 A Consumer’s Guide to Rationalization by Chelsea Kostek, IDSA 33 Seduction: A Poem by Bruce Hannah 34 How Beautiful Design Can Break the Cycle of Overconsumption by Tiziana d’Agostino 38 Learning from Brewing: The Seductiveness of Espresso Makers by Yong-Gyun Ghim 42 Amplifying Design Through Sustainability by Zach Manuel 46 Striking a Balance: Sustainability With a Dose of Practical Optimism by Isis Shiffer, IDSA, and Divya Chaurasia, I/IDSA IN EVERY ISSUE 4 In This Issue by Peter Haythornthwaite, FIDSA 6 From HQ by Donté Shannon, FASAE, CAE 8 Beautility by Tucker Viemeister, FIDSA 12 Women on Design by Rebeccah

IDSA Innovation is the quarterly journal of the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA), the professional

Pailes-Friedman,

EXAMINING THE PSYCHOLOGY OF DESIRE

Words. Without them, we’re fundamentally mute. Yes, a picture is worth a thousand words, but words are the way we, unless we’re Marcel Marceau, express who we are, what we believe, our motives and convictions, and our soul. We use words to engage with audiences to provoke, inspire, educate, and espouse our thoughts.

In the manifold realm of design, words are fundamental to processing and exchanging information. They serve to translate and compress a complex and lengthy project brief into a powerful, motivating essence. A few telltale words become what guide and provoke us to design virtuous, delightful, and purposeful outcomes.

This issue of INNOVATION has been mustered around the word “seduction.” If ever there was a seductive word, it’s “seduction.” What comes to mind? Is it Delilah’s seduction of Samson, or the seductive excesses of Casanova? Maybe the Mafia’s seductive means of bribing politicians, police, and public officials?

Seduction comes from the Latin “seduco,” meaning to lead astray. The IDSA Publications Committee’s call for articles sought to determine, if that’s possible, what constitutes a seductive design intent and outcome. What makes a product more irresistible? Is it because, for example, it’s more green, sustainable, and ethical, or more likely through “the intertwining of aesthetics, functionality, and psychological allure,” as our announcement described? Does the word, nonetheless, leave us with a twinge of hesitancy as we endeavor to design solutions that are valued and lasting?

The world’s multiple complexities demand that designers pay heed to key issues like carbon curtailment and circular design. Such issues are our natural responsibility as we seek to create better design solutions with the prime focus of attending to humankind’s essential needs and those of our remarkable planet.

In that context, is seductive design merely a descriptor of a design approach? Certainly it is not a philosophy like Louis Sullivan’s “form follows function” or Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more”? Maybe it’s something to do with function following form? Is it an ambrosian combination of tangibles and intangibles? Historically, was it the Chanel No. 5 factor because it came from Chanel and was so

Chanel in its memorable bottle, restrained black-and-white packaging with the beguiling fragrance? Or is it the red Ferrari Roma with its throaty roar? Does seductive design acquire a label because it is unique and panders to a user’s taste or a titan’s demand?

Whether we seduce customers (end users) considerately or unabashedly, are we not being manipulative? Are we being exploited for someone else’s advantage?

Sally Montgomery, an interaction designer writing in Medium, suggests that “design has unfortunately lent itself to the manufacturing of addictive behaviors in the name of convenience, user-friendliness, and revenue generation. Design has also lent itself to seduction, to overpowering human reticence, and casual disinformation.” In the article, “Seizing the Means of Seduction,” she goes on to say that “the power of design is, among other things, in its ability to seduce. But Design can also liberate. We can take responsibility for the world in which we design. To do so we must rethink the way we think about design’s place in the world.”

While we are free to interpret seduction in our own way, it does raise the matter of ethics. It is our role to help humankind navigate manifold uncertainties by creating what is beautifully trustworthy, functional, and beneficial. Being part of the bandwagon of more must be taboo. Rapid technology evolution, both hardware and software, constantly calls for more snazzy design and more consumer voice in the market. Product and brand as conjoint twins (a phrase coined by my colleague Ray Labone) are often seen as tools to deliver on the more-ismore clamor. Yes, there are instances where more is better, including providing clean water and better food. Otherwise, this attitude is resoundingly defunct. We must be the good conscience of the future.

The articles and poem in this issue represent thoughtprovoking perspectives on seduction—from the personal to the pragmatic. Is there a need for more debate? Have you been seduced to write a letter to the editor?!

—Peter Haythornthwaite, FIDSA, Member of the Publications Committee peter@peterhaythornthwaite.com

IDSA .ORG 4

IN THIS ISSUE

POSITIONING IDSA TO BE AT THE FOREFRONT OF INDUSTRIAL DESIGN

The Industrial Design Society of America stands at a pivotal moment in its evolution, representing a transition not just in operational or strategic terms but also in its very essence and value proposition to its members, stakeholders, and the broader world of design. This transformation is emblematic of a maturity process that eventually all societies and associations must go through—a journey from being a vital player in the design community to becoming a leading authority in the domain of design. However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that this profound evolution takes time, dedication, and a clear vision for the future. It’s about laying down a roadmap that will steer IDSA toward becoming a more influential, more inclusive, and more innovative organization, thereby enhancing its impact on the world of design.

Recognizing the need for a deliberate and thoughtful approach to change, the Board of IDSA is committed to building a comprehensive strategic plan this year. This plan will not just be a document or a set of objectives; it will be a blueprint for the future—a future where IDSA stands at the forefront of design leadership, education, practice, and advocacy. The core of this strategic plan revolves around several key initiatives designed to elevate the organization’s stature and relevance in the rapidly evolving design landscape.

One of the primary areas of focus will be expanding IDSA’s learning content. In a world where design principles and practices are constantly evolving, there’s a pressing

need for continuous education and upskilling. By offering a broader, more dynamic range of learning materials and opportunities, IDSA aims to empower its members to stay at the cutting edge of design innovation. This includes keeping in mind how our constituency learns so that we are not just offering traditional formats like workshops and seminars but also leveraging partnerships with organizations and companies that can offer digital platforms to reach a wider audience and cater to the diverse learning preferences of the membership base.

Furthermore, the organization is exploring the feasibility, need, and demand for significant initiatives like industry certification and program accreditation. These efforts are aimed at setting a benchmark for design excellence and professionalism, which I believe should be established by IDSA. Certification can serve as a powerful tool for designers to showcase their competency and expertise, thereby enhancing their credibility and long-term career prospects. Meanwhile, exploring accreditation possibilities underscores IDSA’s commitment to maintaining high educational standards within the design community. These steps are essential in a world where design is increasingly recognized as a critical driver of innovation and business success.

Another critical element of the vision for IDSA is the progressive evolution of its annual International Design Conference (IDC) & Education Symposium. This flagship event has long been a cornerstone of IDSA’s offerings, providing a unique platform for learning, networking, and

IDSA .ORG 6

FROM HQ

inspiration. As I talk to stakeholders, they are consistently asking for us to make the conference more relevant, more engaging, and more reflective of the diverse spectrum of design practice today and provide a window into what design practice looks like tomorrow. By curating a richer experience, IDSA intends to create an event that not only celebrates the power of design but also challenges and expands the horizons of those who attend.

Strengthening relationships with the chapters is another critical initiative that I’m passionate about. IDSA’s chapters and volunteers are the lifeblood of the organization, serving as vital touchpoints for local members across the country. By fostering closer, more collaborative relationships with these chapters, we can ensure that initiatives and benefits are more effectively tailored and successfully delivered to our member base. This includes supporting chapter-led events, facilitating knowledge sharing and collaboration among chapters, and ensuring that stakeholders, regardless of their location, feel a connection to IDSA HQ and the broader IDSA community.

I’ve led this type of change, especially of the magnitude I’m envisioning for IDSA, enough times to know that it requires more than just strategic initiatives; it also demands a cultural shift within the organization. This means embracing innovation, inclusivity, and collaboration at all levels. I believe it’s about building a community where everyone feels empowered and has a place to contribute to creating the future of design through IDSA. It’s also about being open to new ideas, new ways of working, and new partnerships that can enhance IDSA’s impact and relevance. However, change also does not happen overnight. It will require patience, commitment, testing and retrying, attempting and refining, abandoning and innovating.

IDSA is on the brink of a new era, characterized by new leadership, methods, structures, and innovation to enhance its value and impact on the world of design. For me, it’s a pivotal opportunity that requires courageous leadership and the bold audacity to seize this moment of tremendous potential and promise for the design community.

—Donté Shannon, FASAE, CAE, Executive Director dontes@idsa.org

Introducing the IDSA Publications Committee

The Publications Committee is a diverse team of IDSA members, supported by IDSA staff, responsible for overseeing IDSA’s INNOVATION magazine. The responsibilities of the committee include developing, curating, and editing content for INNOVATION in preparation for a quarterly release cadence to subscribers and stakeholders. The committee may often collaborate with members, stakeholders, and sponsors to ensure the accuracy, relevance, and quality of the published content. The committee will also advise on future publication strategies, schedules, and the enforcement of editorial standards and facilitate communication between authors, editors, publishers, and other partner publications. The Publications Committee contributes to building and maintaining IDSA’s brand and reputation through well-crafted, cutting-edge, and impactful INNOVATION issues.

7 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

Paul Diehl, IDSA Creative Director Teague

Aziza Cyamani, IDSA Assistant Professor of Product Design University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Peter Haythornthwaite, FIDSA Design Director

Peterhaythornthwaite/ creativelab

Tucker Viemeister, FIDSA Head of Industrial Design Athlon Studio

INDUSTRIAL DESIGN IS HOT

Aesthetics usually play a subservient role when form follows function, but desire is the driver. Seduction is the hidden superpower of design. “Seduction is always more singular and sublime than sex,” says hyperreality philosopher Jean Baudrillard. Sweat forms, sensual textures, ripe materials, and sugarcoating breed emotional attraction. According to Robert Greene, author of The Art of Seduction, “When raised to the level of art, seduction, an indirect and subtle form of power, has toppled empires, won elections and enslaved great minds.” The industrial design complex has transformed the economy, and now we need to use seduction to repair the damaged climate like Janus, the two-faced Roman god of beginnings and endings.

What’s the Real Definition?

“Seen positively,” Wikipedia says, “seduction is a synonym for the act of charming someone—male or female—by an appeal to the senses, often with the goal of reducing

unfounded fears and leading to their ‘sexual emancipation’.” Allen Samuels, IDSA, emeritus professor and dean at the University of Michigan, asks in his 2016 TEDx talk, “Why is designing the oldest profession?” Subliminal seduction, like smiling, is nonverbal communication. Like Cleopatra and Casanova, designers seduce the users, but we may be more like pimps. Either way, we help products connect to buyers. It’s a courtship with products. “Beautiful objects facilitate connections,” CRAVE’s co-founder and vice president of design Ti Chang told Core77. “I created pleasure jewelry [luxury sex toys] to support people’s desire to express themselves, connect with others, and experience pleasure.” Like mass media stars Elvis and Taylor Swift, designers multiply their impact with mass production.

Physical attraction is natural—the birds and the bees, bells and whistles, juicy burgers, sensuous forms, and shiny objects. Attraction to chrome trim is hardwired into our DNA. Irrationality is baked into humans’ reptilian brains. Designers’ work encompasses all kinds of complex

IDSA .ORG 8

BEAUTILITY

social and biological manipulations. Adrian Forty, emeritus professor of architectural history in London, wrote a whole book about it in 1992: Objects of Desire: Design and Society Since 1750. Eve’s seduction of Adam set up the cultural clash of myth versus knowledge. Both camps are armed with seduction: myth with emotional narratives and knowledge with rational arguments. Business or art, either way, the word “seduction” stems from the Latin meaning “leading astray.”

Satan is always tricking us into something bad, naughty, spicy, or dangerous. Hartmut Eslinger says, “Form follows emotion!” For instance, in her 2017 Fast Company article “A Secret History of Selling Out: How Designers Reluctantly Embraced the Corporate World,” design writer Diana Budds explains, “From planned obsolescence to focus groups, designers and corporations haven’t always seen eye to eye.” Design and business are co-dependent; together we exploit commerce to produce and distribute our good work. For many business people, making things attractive is only a byproduct, maybe even a waste product, of making money!

Boon

It’s hard to imagine, even after the Industrial Revolution, that business was not the main force of life. Most of the world was agrarian. Even after the Civil War, Americans went back to the farm. In the 1930s, when industrial design was developing, most Americans were still saving for their first refrigerator or car. “Many think of industrial design as just styling. Industrial Design runs much deeper; it is essential to the American economy,” wrote Donald Dohner in the 1940s (check out his description of industrial design: http:// bit.ly/3JjtSTY). After World War II, factories pivoted from making ammunition to making blockbusters. Society shifted to a consumer one. The machine was humming. Soon middle-class families had all the televisions, cars, and home appliances they needed—and they wanted more!

In the 1920s when the founders of the industrial design profession staged theatrical shows and arranged department store window displays, they created three-dimensional images prototyping their keen sense of presentation and drama. It was only a short step from decorating windows and designing sets to designing products with seductive lines and tints, context, packaging, and branding and then envisioning the whole user experience. The self-proclaimed “first industrial designer,” Joseph C. Sinel, FIDSA, opened

his office in New York City in 1923, where he designed everything from “ads to andirons and automobiles, from beer bottles to book covers, from hammers to hearing aids, from labels and letterheads to packages and pickle jars, from textiles and telephone books to toasters, typewriters and trucks.” (After 1936 he continued his alphabetical work in the San Francisco Bay Area).

Let’s face it! Selling out wasn’t a dilemma for the first industrial designers, who were not compromising personal integrity or principles—they were trying to sell out. In his 1947 book Design for Business J. Gordon Lippincott wrote, “Any method that can motivate the flow of merchandise to new buyers will create jobs and work for industry, and hence national prosperity. Our custom of trading in our automobiles every year, of having a new refrigerator, vacuum cleaner or electric iron every three or four years is economically sound.” Industrial designer Brooks Stevens, FIDSA, championed the strategy of continually “stimulating the urge to buy.” Planned obsolescence was another facet of the midcentury modern era.

Industrial designers fueled the 20th-century explosion of knowledge and wealth. In 1900, the gross domestic product was $590 billion (in today’s dollars). The small industrial design profession amplified and multiplied all the factors measured by GDP for 100 years; in 2000, the GDP was $14.3 trillion—24 times bigger. IDSA promotes the IDEA awards on its website as “a reflection of the magnitude of modern human need and a designer’s remarkable ability to respond to challenges.” Each person touches thousands of products every day. Design furnished the American Dream. Industrial design powered the process of mass consumption with mass production and mass marketing, which equals mass progress. Today, most Americans have more comfortable recliners, bigger TVs and pickup trucks, and smarter electronic devices, adding up to a median net worth of $192,900 per person in 2022, according to the Federal Reserve. There are 283.4 million vehicles registered in America; that’s 2.28 for each household and works out to 0.88 cars per person.

Bust?

Is it a fatal flaw that people always want more and better things? After all, technology makes old things obsolete. Designers don’t force, torture, lie, or coerce people into wanting better things. Our designs convince people by

IDSA .ORG 10

attracting attention and delivering comfort, convenience, and beauty. We seduce users. But Merriam-Webster’s definition is a little more evil: (1) to persuade to disobedience or disloyalty, (2) to lead astray usually by persuasion or false promises, and of course, (3) to entice to sexual intercourse.

Turns out, maybe the dictionary is right. Design is an evil tool of big business’s drive for profit: cutting down the forests, mining the mountains, extracting fossil fuels, paving the land, and mass polluting the waste stream, addicting consumers to products and services. The devil is in those details (small and large).

Almost everyone knows that greenhouse gases are a product of the Industrial Revolution. And we know that industrial design eagerly drove 20th-century consumer craving. Back in 1971, before we kicked him out of IDSA, Victor Papanek, in Design for the Real World, declared, “There are professions more harmful than industrial design, but only a few.” Now, when it’s almost too late, we welcome Papanek back as a prophet of sustainable common sense.

Today, industrial designers face our biggest challenge: the climate crisis. Rebalancing the ecosphere. People say it requires geoengineering (but that sounds like a dentist). We need geodesign! Mass production got us into this mess, and we must use the powerful tools of mass production to get us out. Just as we seduced consumers to buy disposable everything and big cars with chrome fins, now we can seduce consumers to use products that reverse the problems we created. We can make spinach into candy— things that remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere before it’s too late.

Doomsday is not new. In 1961, faced with a similar threat of annihilation from A-bombs, Harold Taylor, an innovative educator and president of Sarah Lawrence College, told the “Man/Problem Solver”-themed Aspen Design Conference: “The world’s problem is now ours, and unless we take the lead in solving it creatively, there will be no more problems solve.”

Now we have to amp up our skills to solve the climate crisis and seduce everyone with things that remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Or else help transition to the warmer posthuman ecology.

—Tucker Viemeister, FIDSA tv@tuckerviemeister.com

WOMEN ON DESIGN

The IDSA Women in Design Committee’s vision is to have gender parity in our industry. One way we work toward this goal is to amplify voices. In this article, we hear viewpoints from women and nonbinary designers who are emerging into the profession and established in their career. The WID Committee welcomes thought, support, and feedback at wid@idsa.org.

APPEAL VS. RESPONSIBILITY

In today’s design landscape, creators have moved beyond crafting products to shaping immersive product experiences. In this expanded field, narratives unfold through each curve and contour, blending aesthetics and emotions, and transforming designs into compelling and immersive stories designed to entice consumers. Welcome to the world of seductive design.

Seduction Redefined: A Deeper Dive

As important as functionality is, consumers today expect products to deliver more than function alone. They want products that they can connect to emotionally and that bring them joy. This is the definition of emotional design. We see designers trying to meet this demand across product categories. Take, for example, outdoor and sports products that exude a sense of speed and power, highlighting the sensations your body will experience during product use. The sleek design of a high-performance bicycle features an aerodynamic frame and vibrant colors not only to convey speed and power but also to emphasize the exhilarating feeling cyclists can expect when riding the bike.

Storytelling is a key component in creating a connection between a consumer and the product. The story connects the physical object to the consumer’s emotions. These emotional responses can be powerful, creating a bond between the consumer and the product as well as, crucially, cultivating brand loyalty. Packaging, in particular, has evolved to become part of the product experience, as demonstrated

by the plethora of unboxing videos on TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram.

Both technology and the beauty businesses use packaging to define their brands. It is not just a container but an integral part of the overall seductive experience. Think of the similarities between your iPhone and a bottle of perfume; both promise the consumer an experience and are purchased as a part of a lifestyle the consumer desires as much as they are purchased for function. Consider the iPhone’s sleek, minimalist packaging, which resonates with the product’s promise of sophistication and innovation. Similarly, a bottle of perfume, adorned with carefully chosen materials and design elements, becomes a tangible embodiment of the sensorial journey it offers. Both purchases transcend functionality, entangling the consumer’s lifestyle aspirations with the allure of a unique experience.

The Role of Emotional Design

As consumer expectations evolve, emotional design emerges as the driving force behind product desirability, transcending the fulfillment of needs to nurture a profound connection. This shift toward emotional resonance elevates the functionality of products and establishes a deeper bond, transforming them into vessels that embody and reflect the users’ aspirations and sentiments.

Users perceive more aesthetically pleasing designs as easier to use and more effective. Beauty and usability

IDSA .ORG 12

are intertwined. Clean lines, intuitive interfaces, and straightforward user journeys contribute to the overall appeal of a product. The aesthetics of a product influence consumers’ expectations, fostering the perception that it will be easy to use and that it is superior to its competitors.

Two key questions about the significance of emotional design arise. The first is methodological: How does one effectively infuse products with emotional resonance? The second question is ethical: Given the potential extremes of emotional design, what is the designer’s responsibility to balance allure with transparent and conscientious design and manufacturing practices?

Engaging More Than the Eyes

How do designers go beyond surface-level aesthetics to create meaningful and captivating interactions? Designers can appeal to multiple senses to create an immersive and engaging experience. This might include tactile elements, sound design, or even scent. Material, color, and form are part of the overall product narrative and can be used to create an immersive and emotionally resonant experience. Designing with an empathetic approach can also increase the emotional resonance of products. Products for new parents can connect emotionally to their ethos on child rearing. Lea Stewart, IDSA, senior manager of design at

Newell Brands, uses these emotional drivers to differentiate between brands like Graco and Baby Jogger, which she oversees. Stewart notes that “a product like a stroller can convey that you are the type of parent who believes the best thing for a child is for the adult to keep their adult life and bring the child along. That way, they get to experience more and see good modeling. The aesthetics then cater to that by appealing more to an adult sensibility: looking easy to take on the go and not impeding life. On the other hand, a different parent may believe that the family should center on the child and togetherness, so you, therefore, embed that in the product aesthetics to evoke security, comfort, and parent-child connection. This is all subconscious to the user when they purchase the product, which is the seduction.”

Another path to creating a connection is to infuse products with nature-inspired elements that evoke emotional connections. For instance, a packaging designer for a skincare brand might incorporate botanical illustrations, earthy textures, or eco-friendly materials to align the product with natural goodness and trigger a sense of tranquility and well-being in the consumer.

Customization is one tried-and-true way to connect the consumer to a product. Products that allow consumers to personalize or customize elements based on their preferences, experiences, or memories create an emotional

13 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

Packaging design for an organic beauty line that connects with consumers by evoking nature, created using Midjourney.

bond. A furniture designer, for example, may offer customizable fabrics, colors, or engraved details, enabling customers to imbue the product with personal meaning and emotional significance.

Inclusivity is a particularly powerful catalyst in emotional design, transcending visual appeal to provide aesthetics and thoughtful, universal functionality. By embracing diverse perspectives and considering the needs of a broad audience, designers not only create universally appealing product experiences but also weave a narrative of allure that resonates on a profound and inclusive level, captivating users from all walks of life.

If you’re interested in going deeper, consider Don Norman’s Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things and Designing Design by Kenya Hara. Norman explores the emotional impact of design on user experiences, delving into how aesthetics, usability, and emotional connections shape our perceptions of products, a perspective directly relevant to the nuanced realm of seductive design. Hara’s book is relevant to the broader topic of design, including elements of seductive design. While the book is more philosophical, exploring the mindset and principles of design, it provides valuable insights into the foundational aspects of creating compelling and aesthetically pleasing designs.

The Ethics of Seduction

While strategies for creating seductive products abound, the ethical question of the designer’s responsibility hovers over all of them. Given the impact of technology and evolving consumer expectations on the field of industrial design, it is only natural to question how the use of multiple senses in crafting seductive product experiences might lead to unwanted outcomes—think doomscrolling on any social media platform.

As designers, we need to examine the potential unintended consequences of crafting seductive product experiences. It raises a fundamental question: In whose best interest is it really to design an experience that immerses the consumer to an extreme, and possibly addictive, extent? Awareness of potential pitfalls is essential to creating products that enhance well-being and, at the very least, do no harm.

The shadow of ethical concern looms large over the art of crafting seductive products. The relentless pursuit of engagement and immersion may inadvertently lead to the exploitation of human vulnerabilities and the perpetuation of unhealthy behaviors. As designers, we must navigate the delicate balance between captivating our audience and respecting their autonomy and well-being. In an era dominated by evolving consumer expectations and

technological advancements, the use of multiple senses to create captivating experiences raises profound questions about responsibility and accountability. This calls for a nuanced approach that acknowledges the power dynamics inherent in design and prioritizes the ethical imperative of fostering positive and empowering experiences.

We must confront the potential ramifications of immersing users in seductive experiences by considering the fine line between engagement and exploitation. Only by conscientiously weighing the ethical implications of our design decisions can we ensure that seductive products enrich the lives of users without compromising their dignity or agency. It is incumbent upon designers to adopt a proactive stance, diligently examining the unintended consequences of their creations and prioritizing the well-being and autonomy of users above all else. This heightened awareness of ethical considerations underscores the imperative to design products that not only captivate but also uplift and enrich the lives of individuals in a responsible and sustainable manner.

Advocate and Enabler

In the dynamic field of design, the shift from crafting products to shaping immersive experiences marks a transformative moment wherein aesthetics and emotions are consciously intertwined. As we navigate this seductive landscape, emotional design emerges as the linchpin, propelling product desirability beyond functional utility. The narrative unfolds through sleek packaging and glossy campaigns, transforming purchases into sensorial journeys that resonate with consumers’ aspirations.

The increasingly savvy incorporation of multiple senses in product design—the intersection of allure and functionality— beckons an ethical inquiry, prompting designers to balance the immersive experience with transparency and conscientious practices. Methodologies such as empathetic design, nature-inspired elements, and customization serve as tools for creating emotionally connected products. Inclusivity becomes the heartbeat, ensuring universal appeal, while heightened awareness becomes the compass, guiding designers to navigate the potential extremes of seductive experiences and prioritize the well-being of consumers. The world of design evolves, inviting creators to transcend boundaries and shape not just products but profound and inclusive narratives that captivate the diverse tapestry of human experience.

—Rebeccah Pailes-Friedman, IDSA rpf@getinterwoven.com

IDSA .ORG 14

SEDUCTION

SHINY OBJECTS

Why are people irresistibly attracted to shiny objects?

As designers, we have long been captivated by the allure of shiny objects and the magnetic pull they exert on people. Transcending geographical and cultural boundaries, this behavior prompted us to delve deeper into its underlying causes. Our curiosity led us to a fascinating intersection of psychology, physiology, and design, which uncovered the allure of shiny objects.

Uncovering Hidden Behaviors

Over the years, we have visited and exhibited at numerous design shows and exhibitions. These events are opportunities to capture people’s impressions when they encounter a new product. Some of the featured products were more seductive and attracted more people than others. Especially in recent years, a few things caught our attention: how

many visitors were drawn to shiny products and the increase in the number of shiny objects being showcased. This phenomenon wasn’t limited to a specific location or culture; we observed it in different parts of the world. We hypothesized that perhaps the decline in living standards of the middle class in higher-income countries has led designers to focus more on designing shiny products that look expensive. Although these objects were designed using low-cost and low-value materials, they continue to attract people.

When we looked deeper and conducted a literature review, we found that researchers in the field of psychology and marketing have explored this question in recent decades. These studies suggest that people are attracted to shiny objects because of their association with highervalue materials like gold and silver. To investigate whether

IDSA .ORG 16

Above: Optical cues in the glass silently entice people to drink more.

the preference for shiny objects is culturally inherited, researchers turned their attention to groups that have not been exposed to conventional cultural standards of beauty, such as children who have not yet been influenced by cultural norms and societies that are culturally isolated. Katherina Danko-McGhee’s research at the University of Toledo in 2006 showed that children favor artwork that contains shiny objects and surfaces as well as gold and silver objects. Another study by Mary Stokrocki in 1984 at Cleveland State University reveals that preschool children prefer to use shiny materials, such as foil, to make their art more attractive.

To test these ideas further, in 2003 scholars Richard G. Coss, Saralyn Ruff, and Tara Simms conducted experiments involving infants between seven and 12 months old who lack the concept that shiny objects inherently hold more value. Researchers observed the behaviors of infants and toddlers who were served food on shiny metal plates and white plastic plates. Those who were served meals on mirror-finish metal plates not only finished all the food but also licked the plates. When this experiment was repeated with plates identical in material and color but with different finishes, those who used plates with a glossy finish displayed more mouthing activity (e.g., licking the objects, biting them, putting them in their mouth) compared to those who used plates with a matte finish. Furthermore, researchers observed that these mouthing activities closely resembled drinking behavior, leading to another question: Does the shininess of the plates remind them of water, something they likely desire after finishing their meal?

In 2013, Katrien Meert, Mario Pandelaere, and Venessa M. Patrick from Ghent University conducted a parallel experiment involving adults. The 126 test participants were divided into three groups. The first group consumed salty crackers without any beverages; the second group ate the crackers while also drinking water; and the third, serving as a control group, did neither. Subsequently, each group viewed eight photographs, with half presented on glossy paper and half on matte. Results indicated a preference for glossy pictures across all three groups. However, the two groups that had consumed crackers rated the glossy pictures as significantly more attractive. In other words, as their desire for water increased, their preference for glossy surfaces became more evident. Due to the importance of fresh water on our health, human beings are wired to seek water and look for optical cues as to its source.

Silent Design

These findings can help us, as product designers, understand human physiology and enable us to design better products that truly satisfy people’s needs. Designers can take

advantage of this innate human instinct for water and design shiny products to enhance their attractiveness and boost sales. However, we believe that designers should use knowledge of this instinct to design products that promote harmony between humans and the environment.

Building upon these findings, we explored ways to use glossiness in product design to improve people’s quality of life. We applied this research to a context where it holds particular relevance: water-drinking habits. Especially as people age, the body’s thirst signal decreases due to physiological changes associated with aging. We designed a water glass that would encourage people to drink water.

Water in nature is dynamic; it flows, moves, reflects, and refracts. We perceive these characteristics as signs of clean water. To evoke these same feelings in our water glass, we used the material properties of glass to stimulate the effects of water. By varying cross-section curves on the inner and outer surfaces, we created reflections and refractions that replicate the dynamism of water. These optical cues entice people to drink more without having to think about it. We used silent design features to make the familiar form of a water glass more attractive while encouraging healthier behaviors. The use of a familiar form for the product demonstrates that design can elevate people’s quality of life without incurring additional costs or using extra materials.

Further application of this research could involve designing and improving the safety of objects that are used in day-care facilities. For example, to lessen the transmission of pathogens by saliva, designers could use a dull surface finish to make children less prone to putting objects in their mouths. Some animals are also innately drawn to water. Designers could apply this knowledge to pet products that would control pets’ appetites or prevent them from chewing potentially hazardous objects. Another area for exploration might involve investigating how matte or glossy finishes on faucets affect water consumption.

Although humans may be attracted to objects because of their semantics, the meanings and feelings associated with a product, our research suggests that attraction could be rooted in physiological factors rather than culturally inherited ones. Understanding the underlying reasons behind human behaviors is essential for designing products that not only enhance attractiveness but also foster harmony between humans and their environment.

—Erdem Selek, IDSA, and Hale Selek, IDSA eselek@uoregon.edu; hselek@uoregon.edu

Erdem Selek and Hale Selek are associate professors of product design at the University of Oregon and founders of Selek Design.

17 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

SEDUCTION

THE ART OF TEMPTATION

In the fascinating world of seductive design, functionality meets an irresistible charm that captures people’s hearts and minds. Picture it as a symphony of elements carefully orchestrated to create a sensual experience that goes beyond the practical and ventures into the realm of the enchanting.

IDSA .ORG 18

Odyssey is a double-sided magnetic rug collection created using the principles of seductive design and human psychology.

Seductive design is like creating a magic potion that combines emotional connection, user-centered design, sensory appeal, simplicity, scarcity, storytelling, instant gratification, personalization, gamification, and social proof. When designers follow the principles of seductive design, they aren’t just making products; they’re crafting experiences that linger in hearts and minds.

The Principles of Seductive Design

The emotional connection is the secret sauce that makes a product more than just a thing. When deliberately chosen, colors, visuals, and the overall aesthetics will make you feel something. Warm and vibrant shades might fill you with joy, while cool tones bring a sense of calm. Seductive design isn’t just about utility; it’s about crafting an experience that people connect with on a personal level.

User-centered design makes things that seamlessly fit into our lives. It’s about understanding how we behave, what we like, and what we need. The closer a product aligns with our expectations, the more irresistible it becomes. It’s not just about looking good; it’s about making our lives easier and more enjoyable.

Sensory appeal tickles our senses. Imagine a product that not only looks fantastic but also feels amazing to touch or produces delightful sounds. That’s the kind of holistic experience that leaves a lasting impression. It’s not just about looking good; it’s about feeling good too.

Simplicity and intuitiveness are the friendly neighbors of seductive design. We’re naturally drawn to things that are easy to understand and navigate. Seductive design eliminates mental gymnastics, making interactions smooth and enjoyable. It’s not just about making a product user-

friendly; it’s about making it effortless.

Scarcity and exclusivity are seductive. It’s the rush of wanting something because it’s rare or exclusive. Limited editions, special features, and time-limited offers create a sense of urgency. They make products instantly coveted by appealing to our desire for uniqueness. It’s not just about making a well-considered product; it’s about making it unique.

Storytelling isn’t just for bedtime; it’s a powerful tool of seduction. Whether it’s the story of how a product came to be, its purpose, or the impact it can have, a compelling narrative adds depth and meaning. It’s not just about the product; it becomes part of a personal story, sparking imaginations and creating connections that last.

Quick feedback and instant gratification encourage engagement. It’s like having a cheerleader who encourages you to keep engaging. Features that give you a pat on the back right away satisfy our need for immediate gratification. It’s not just about making the product enjoyable; it’s about making it downright habit-forming.

Personalization is like having a product that understands you. Tailoring the experience to your preferences makes you feel seen and appreciated. It’s not just one-size-fits-all; it’s a product that understands you, adding a layer of connection that goes beyond the surface.

Gamification turns your interaction with a product into a game. Challenges, rewards, and a bit of healthy competition tap into that inner desire for achievement and progression. It’s not just a tool; it’s an interactive journey that keeps you hooked.

Lastly, social proof—because we’re all influenced by what others think—is a powerful element of seduction.

19 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

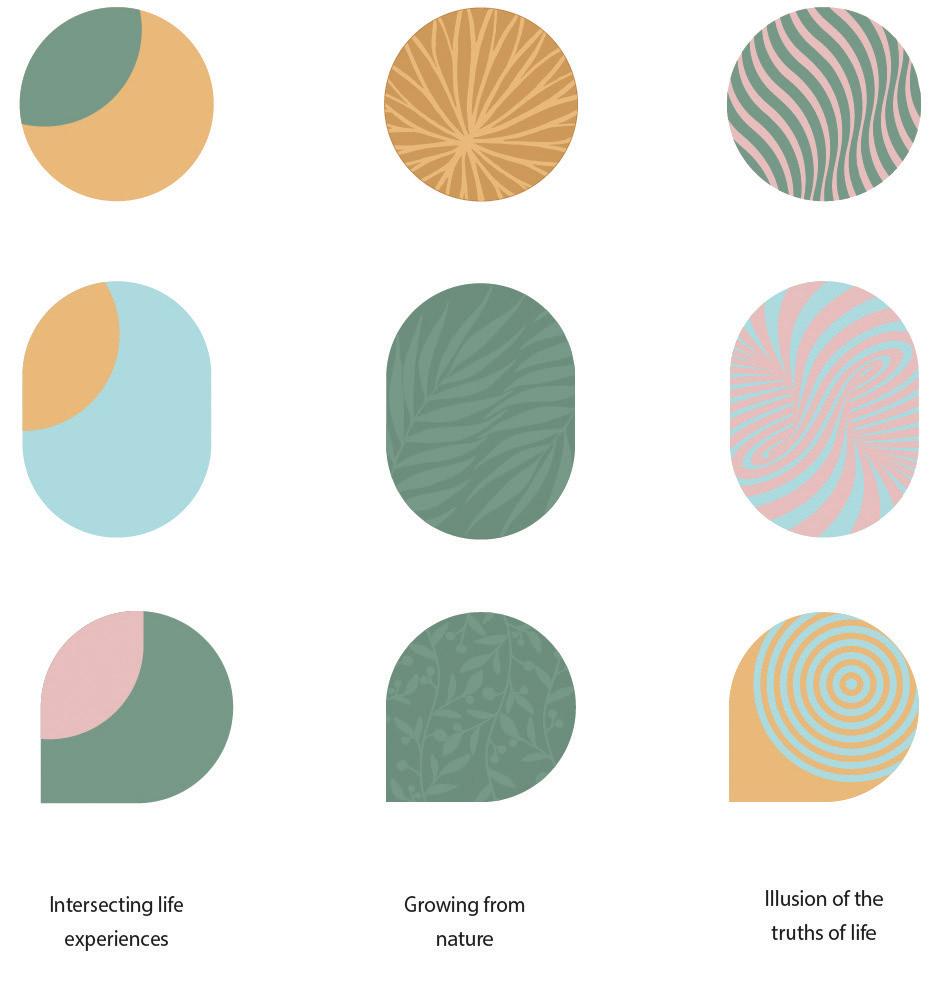

As they go through life, people collect objects that bring meaning. They don’t always want to replace their old things with new objects. The magnetic and modular rug tiles thread through their old belongings, preserving them. The circle symbolizes the cycle of life, while the oblong shape signifies growth stemming from this cycle, and the pointed circle represents unforeseen junctures in our lives.

Positive reviews, testimonials, and endorsements build credibility and make a product more appealing. Knowing that others had a good experience creates trust, enhancing the seductive nature of a product. It’s not just about making it fun; it’s about making it even more fun.

Creating Irresistible Products

As we plunge deeper into a world where technology and design evolve hand-in-hand, the importance of seductive design will keep growing. In a sea of choices, it becomes a guiding light that helps people navigate and gravitate toward products that truly speak to their desires.

Seductive design is a beautiful dance between creativity and psychological principles that taps into the very essence of what makes us human. From emotional connection to user-centered design, sensory appeal, simplicity, scarcity, storytelling, instant gratification, personalization, gamification, and social proof, each element contributes to the irresistible

nature of well-designed products, transcending the tangible and venturing into the sublime. Armed with an understanding of these principles, designers have the power to create not just products but also experiences that become a part of people’s stories.

As our world becomes more connected and technology becomes even more integral in our lives, the role of seductive design will increase, shaping the way we interact with and perceive the world around us.

—Jayati Sinha, IDSA jayati.design@gmail.com

Jayati Sinha is a design lead at Fjord, part of Accenture Song, helping Fortune 500 companies create products and experiences.

IDSA .ORG 20

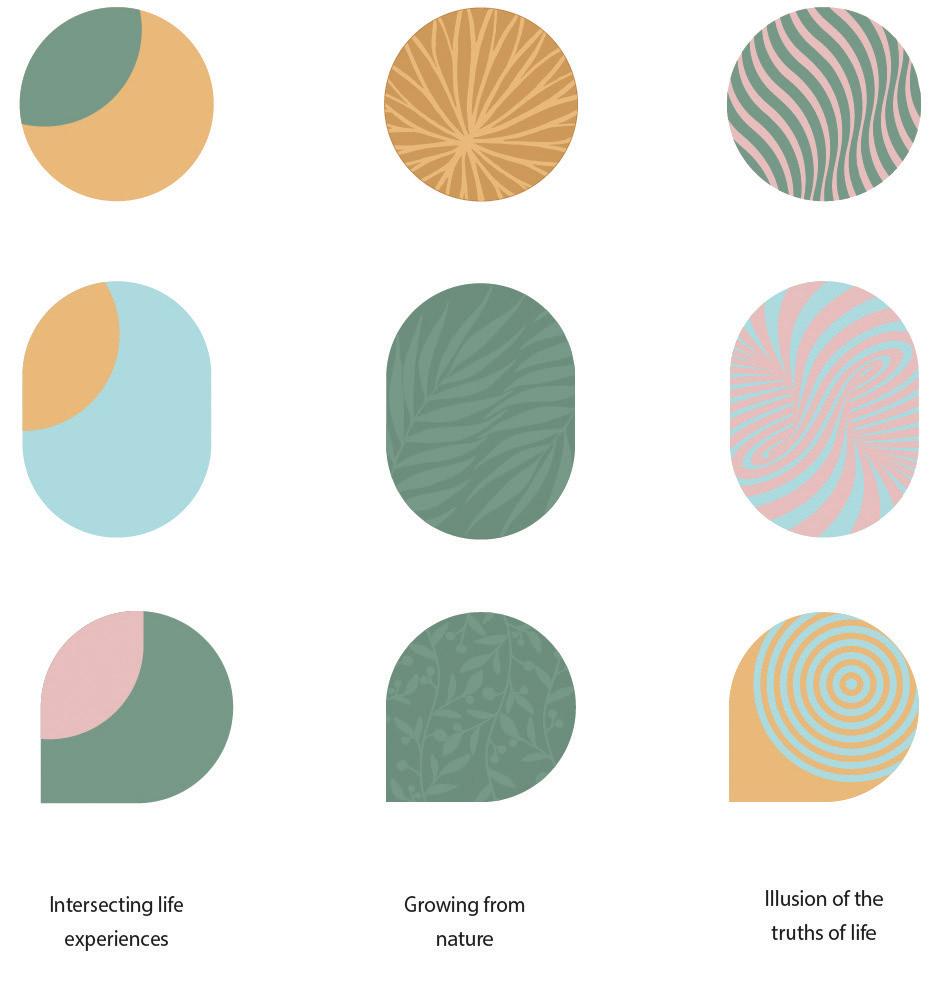

The intersecting pattern (left column) is about how everything that happens in our lives is interconnected. The nature pattern (center column) is a reminder of how we learn and grow from nature. The illusion pattern (right column) signifies how we get caught up in believing stereotypes that in reality are not true but are illusions a society creates.

21 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

TOUCH: THE ALLURE OF TANGIBLE DESIGN

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “seduction” as “the qualities or features of something that make it seem attractive.” What does seduction signify in the context of industrial design? What makes industrialdesigned products, services, and user experiences so alluring that customers want to come back repeatedly?

Facets of Seduction

Stephen Anderson explored seduction in interaction design in his book Seductive Interaction Design: Creating Playful, Fun, and Effective User Experiences. In service and experience design, the 5E experience model—entice, enter, engage, exit, and extend—begins with entice (or excitement) to explain why customers are incentivized by different types of services.

When I think of service design, I’m inspired by the field of industrial design. How can we use product design to its full capacity? How can we leverage meaningful tangible artifacts to connect touchpoints within the user journey to create more incentives for both service recipients and providers?

I interpret the phrase “seduction in design” as an expression of the designer’s empathy toward service

providers and service recipients (the users). By satisfying individual needs, empathetic design solutions create external incentives and internal motivations that capture attention and drive action. This approach epitomizes the allure of human-centered and life-centered design.

Empathetic design ideas create positive and lasting impressions through engaging service encounters with tangible, cultural, and societal artifacts. The concept of embedded empathy can refer to Jane Fulton Suri’s Thoughtless Acts?: Observations On Intuitive Design, which discusses how people’s behaviors are influenced by the built environment to form new habits or user experiences. Suri uses the term “thoughtless acts” to describe how our actions and behaviors are determined by the affordance (the potential actions that an artifact or space enables or offers to an individual, connecting to the physical capabilities of the individual and the characteristics of the artifact or space), life rituals, and interactions these artifacts facilitate.

The concept of seduction in design also brings to mind the term “stickiness.” We can understand that through the lens of affordance, a concept defined by Don Norman, the author of The Design of Everyday Things. Affordance represents the possibilities in the world for how agents—

IDSA .ORG 22

SEDUCTION

whether they are people, animals, or machines—can interact with something as intended or not by the service providers (e.g., makers), whether in a visible or hidden way.

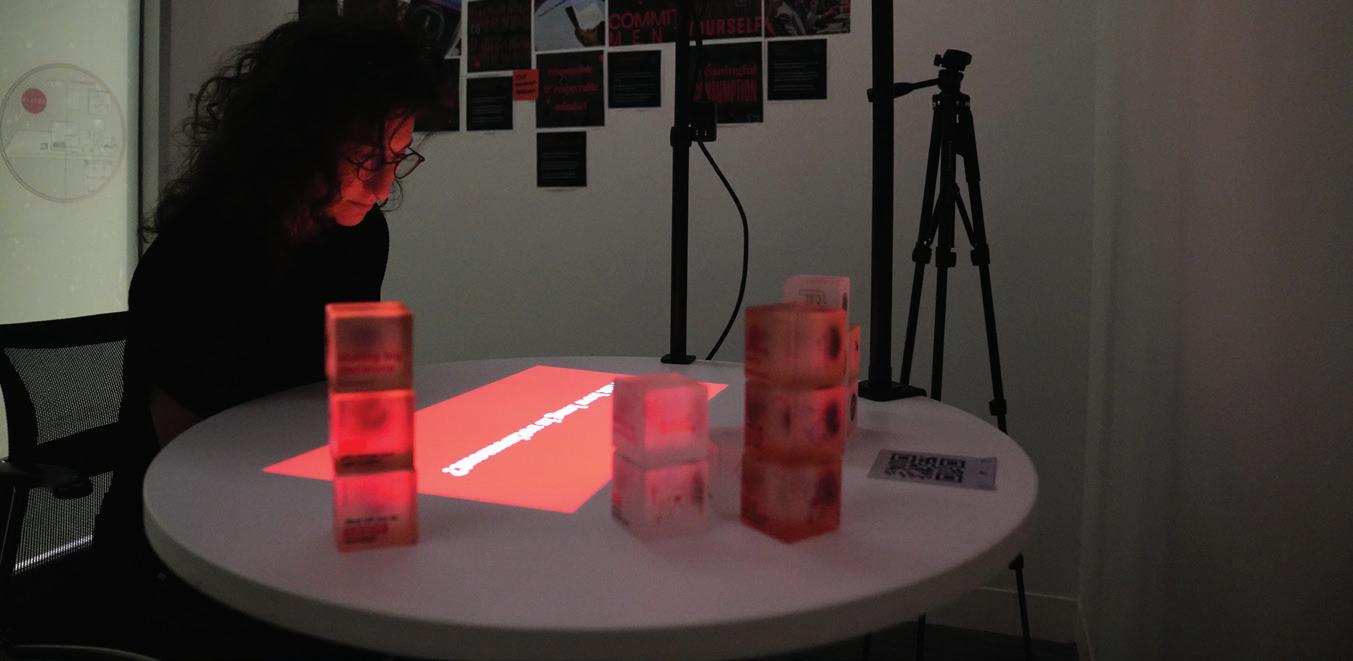

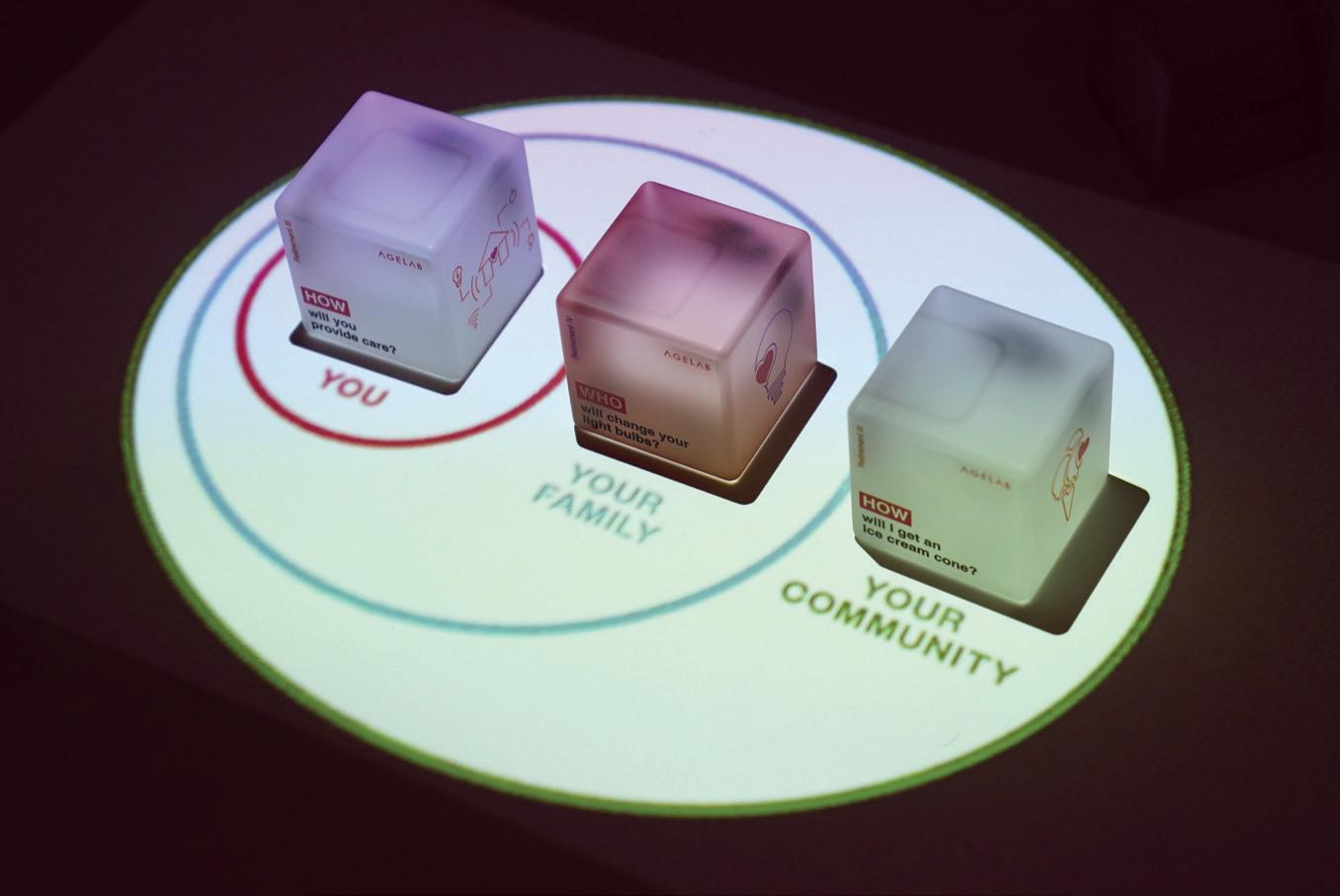

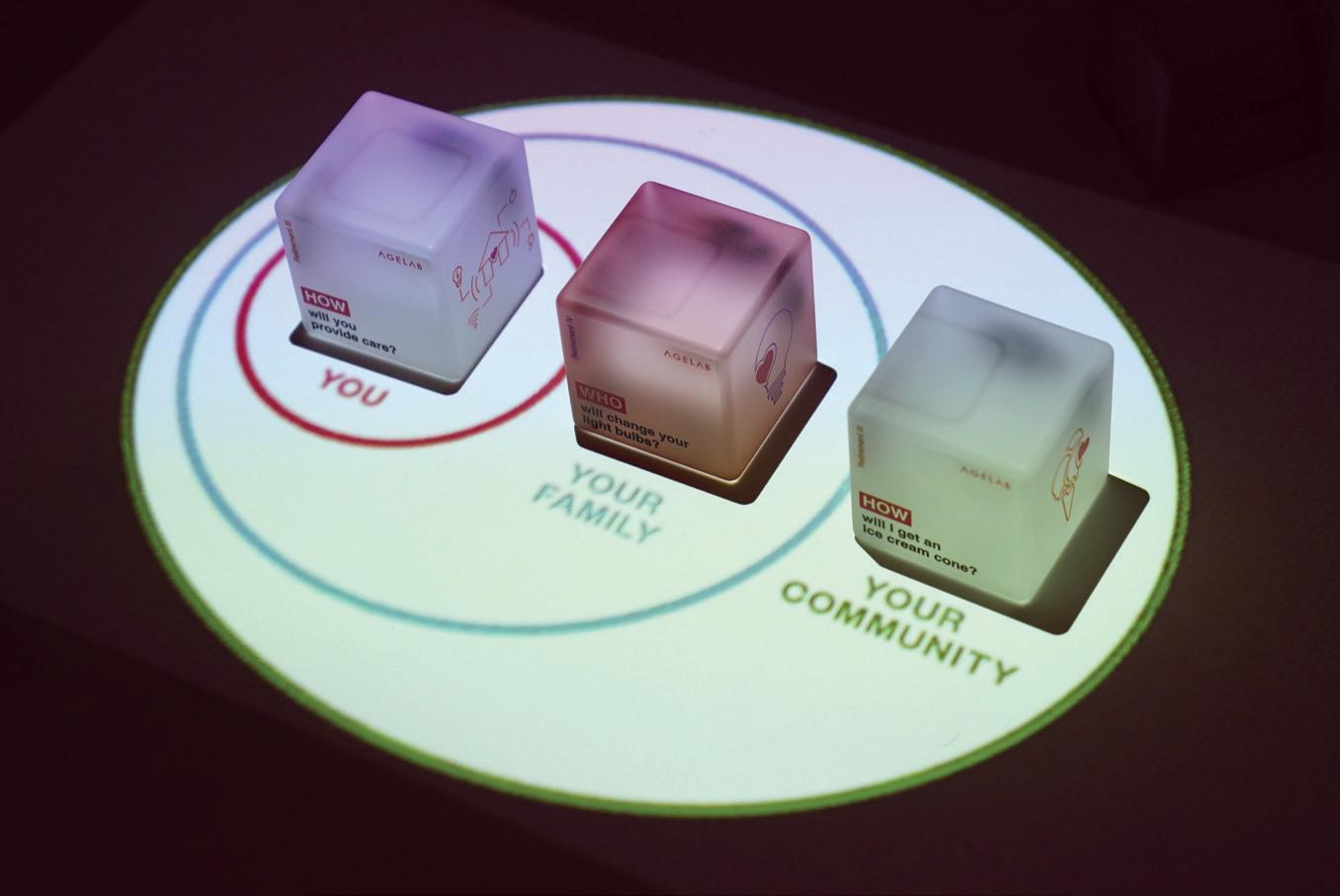

This article explores a case study that exemplifies how designed affordances and their resulting thoughtless acts demonstrate the power of seductive design. It examines how we can create a set of tangible artifacts (e.g., Longevity Planning Blocks, or LPBs) and interactive service encounters (e.g., tech- or touch-based services) to increase people’s desire for longevity services to improve their awareness, knowledge, and longevity. The case study is based on redesigned longevity services that were the focus of a doctoral research project I developed at the MIT AgeLab with Dr. Joseph Coughlin.

Leveraging Attraction

People are living longer and aspire to have a better quality of life. Longevity coaching services emerged out of the need to help people cope with these disruptive demographic transformations. With their roots in traditional financial planning, they include topics such as education, community, family, home, risk, mobility, and health. Longevity coaching empowers and encourages individuals and families to

better prepare for the complicated systemic socioeconomic challenges that define the era of longevity economics. Longevity economics refers to research on how changes in human longevity affect economic factors, including labor markets, productivity, healthcare costs, pension systems, and economic growth. It encompasses a range of challenges that arise from increased life expectancy and an aging population.

LPBs were designed to help people recognize the need to transition from the traditional three-stage model of life (birth, education, and retirement) to a more adaptable and fluid multistage lifestyle approach. This aligns with Susan Wilner Golden’s assertion that life is characterized by different stages rather than simply age as a number. She summarized her 18 life stages into a proposed five-quarter (5Q) life framework: starting, growing, renaissance, legacy, and extra. The framework emphasizes the new concept of furtherhood in the new stages of longevity from the third quarter, renaissance, to the fifth quarter, extra.

Based on the idea that age is not merely a numerical number, the MIT AgeLab has conducted a continuous experiment for the past two years. The experiment is designed to examine the implementation of longevity

23 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

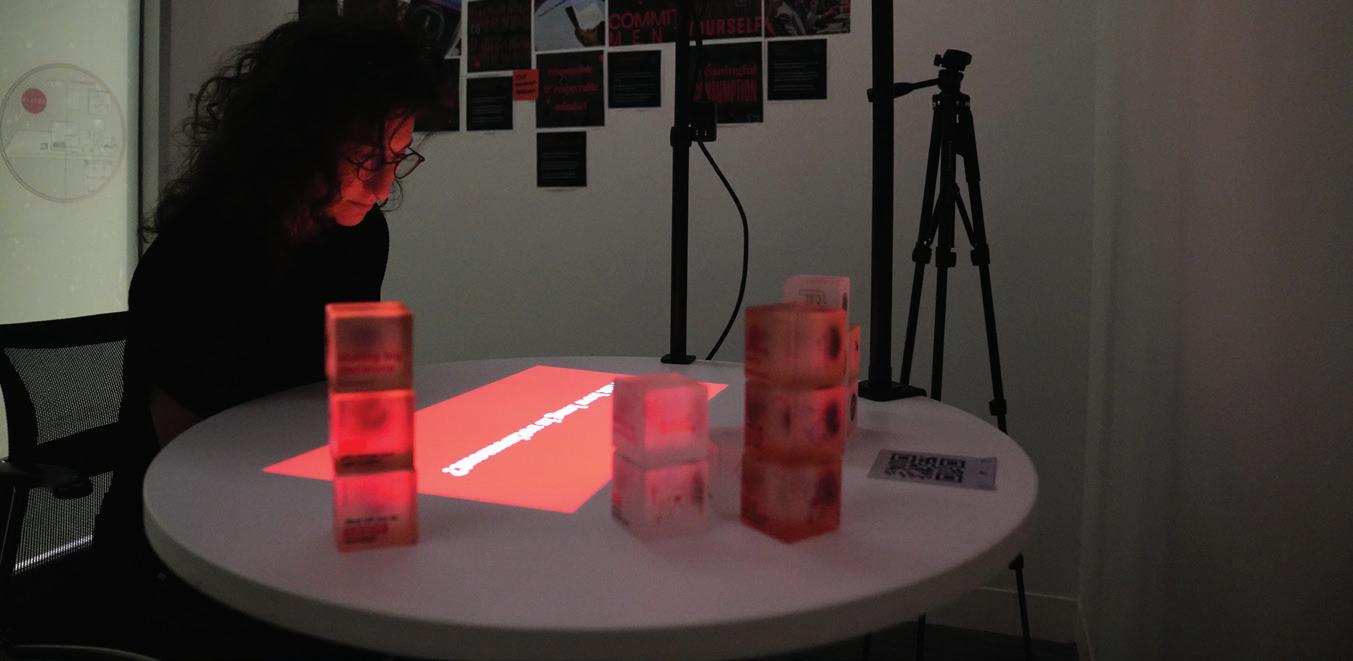

A study conducted at the MIT AgeLab sought to understand how to seduce people into wanting longevity services by using tangible artifacts in the form of Longevity Planning Blocks. (Photo: Sheng-Hung Lee)

planning at the individual and societal levels. It comprised a series of qualitative studies, including semistructured expert and user interviews, surveys, controlled experiments, and co-creation workshops. The goal was to assess the participants’ level of engagement through the seductive design of two critical factors: tangible artifacts (the LPBs) and an engaging service encounter.

A service encounter is the direct interaction between a customer (user) and a service provider. This interaction can occur across various scenarios in different communication formats from in-person to digitally mediated. Additionally, service encounters are key moments in service delivery because they offer the customer a tangible experience of the service quality and significantly influence customer satisfaction and perception of the service brand.

The ability of an object to elicit people’s emotions and stimulate their thoughts is highlighted in Sherry Turkle’s concept of evocative objects. Turkle defines evocative

objects as an intellectual element capable of anchoring memories, nurturing connections, and inspiring innovative ideas. Bringing tangibility to the assessment process can facilitate more constructive and meaningful dialogue among designers, clients, and other essential stakeholders. For example, touch is an intricate sense that enables us to explore the complex world by interacting with different materials, textures, and temperatures and can provide a means of communication.

In this context, LPBs were intentionally built as provocative artifacts to enable participants to express their emotions, articulate their ideas, and engage in discussions about sensitive, personal, and private longevity-planning topics.

The blocks were designed to be alluring. They are sized to fit perfectly in one’s palm. The material, a frosted acrylic, combined with rounded corners almost demands to be touched. As soon as participants sit down in front of the

IDSA .ORG 24

The Longevity Planning Blocks invite people to reflect on the situations they may find themselves in as they age to help them plan for the future. (Photo: ShengHung Lee)

blocks, they intuitively reach out to start stacking them. It’s a familiar and “thoughtless act,” adapted and elevated from the children’s playroom.

The proposed longevity service aims to enhance users’ understanding of longevity literacy through interacting with LPBs across different service encounters. We used six design attributes to gauge the quality of the longevity service: learnability (ease of comprehension), efficiency (effectiveness in learning), intimacy (provision of personal space), trustworthiness (establishing trust), confidence (leaving a positive impression), and satisfaction (perceived quality). Participants rated the service quality on these six design attributes. Their insights gave us fresh and creative perspectives to understand the connection between how attractive the design is, the design intent, and the effectiveness of using a tangible artifact in longevity services.

The seductivity of the LPBs is integral to building trust between service providers, longevity coaches, or financial advisors and their clients. Particularly in longevity-planning scenarios, where individuals discuss sensitive topics related to their financial future and challenges, the service encounter introduces additional layers of sophistication that must consider various scripts, environmental factors, team dynamics, and touchpoints within the system.

Seduction in design plays a crucial role in creating not just a seamless and successful user experience between two parties but also one that is comfortable, safe, and enjoyable. The preliminary findings from the experiments in longevity services transcend simple evaluations of efficiency and effectiveness in service encounters involving tangible elements (LPBs). They further highlight the importance of empathy both toward and with individuals. This insight serves as a powerful reminder of the evolving roles and responsibilities of designers. It underscores the need to consider not only the design of physical products and services but also to embrace wider perspectives that include political, communal, cultural, and social dimensions. This holistic approach is essential for generating a meaningful and positive impact.

Impacts for the Future

Seductive artifacts associated with service encounters

can culturally, socially, and globally shape meanings within the context of building an equitable, sustainable, and inclusive longevity ecosystem. However, we must consider the political dimensions of seduction in design. Do we aim to captivate users to be addicted to the novel services and experiences we have crafted? Do we wish to achieve altruistic commercial success by considering the environmental and social impact? Can we seduce citizens to use more public transportation and share resources to reduce carbon emissions?

In this article, we explored the notion of seduction in design through the creation of tangible artifacts (LPBs) coupled with interactive service encounters. The aim of this study was to learn how to stimulate people’s attraction to longevity services to improve their awareness, knowledge, and strategies for living a long and healthy life. In the era of longevity economics, with the significant influence of service and experience industries, seduction in design has become a context-sensitive term that can be interpreted and applied in various ways. Incorporating seduction into the design process will create deeper, more meaningful, more respectful, and more effective engagement for people and with people.

—Sheng-Hung Lee, IDSA shdesign@mit.edu

Sheng-Hung Lee is a designer and PhD researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology AgeLab and Ideation Lab and a member of the IDSA Board of Directors.

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to extend heartfelt gratitude to the dedicated team that played a pivotal role in the success of the longevity service experiments. Special thanks go to Professor Maria C. Yang, Dr. Joseph F. Coughlin, Professor Olivier de Weck, Professor Eric Klopfer, Professor John Ochsendorf, Gianfranco Zaccai, Michael Peng, Professor Sofie Hodara, Dr. Lisa D’Ambrosio, Dr. Chaiwoo Lee, and Alexa Balmuth, as well as the generous sponsorship provided by the MIT AgeLab and the MIT Ideation Lab.

25 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

SEDUCTION

CMF: DESIGNED TO SEDUCE

Choosing color is commonly left as the final step of product development. Even in design school, it was probably introduced in your last semester, when you first realized this step existed—or at least that is how it was for me. But CMF has intrinsic power. It adds significant value to the form and function of the product, it affects the perception of a product by creating an irresistible emotional pull, and it improves consumer experiences while driving purchase intent—because perception is reality.

IDSA .ORG 26

27 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

The traditional black-and-gold design of Revlon’s lipstick (above), and the pastel-infused design of the industry newcomer Fenty Beauty (below).

When we think about captivating users, most of the time we think about how our product will function and how it will respond in multiple scenarios and use cases. Rarely do we consider how much colors and materials seduce users. The sooner in the design process we consider these elements, the stronger the effect on the user and life cycle.

Unleashing Product Potential

One place we can see the psychological impact of CMF is in the beauty industry. Millions of products serve almost the same function, and it is difficult to differentiate between the brands. Their sameness fails to stop customers as they are walking through the store or scrolling on their phones. When new brands like Glossier and Fenty Beauty entered this overpopulated market, competing with brands that had led the industry for decades, they became popular and were easily distinguished from mainstream brands. Their packaging takes a different approach to color and material selection, staying away from the common clear plastic, black, silver, and gold and focusing on an aspirational image of luxury and glamour. They introduced pastel pinks, violets, white, and frosted plastics, lending a simpler and more youthful feel, an approach this industry hasn’t seen before. Seducing audiences by pushing boundaries and challenging norms created a new image for these products that resonates with younger generations.

Well-thought-out CMF plays an important role in sustainability when designed for reuse and disassembly. Part lines and color amounts matter for rebranding opportunities, among other benefits. Considering what part of the product is the most visible and what perception that color or material has on the users can be a strategy to express the brand attributes, making the brand as recognizable as possible.

One of the best tactics I have seen to seduce consumers is to create the perception of quality by making the touchpoints with high-quality materials; in the store, the consumer will assume that the entire product shares the same quality as its touchpoints. For example, when walking down an aisle in a big-box store, you can compare coffee makers that are next to each other. When you grab one carafe with a plastic handle that feels light and flimsy,

automatically you think that it feels cheap and is poorly made, even if the rest of the product is metallic. But if you grab a carafe with a metallic handle that feels heavier and more sturdy, you perceive the product to be of higher quality, even if the rest of it is made from cheap plastic.

Perception begins before the first interaction with a product, however. Now that e-commerce has grown, consumers shopping online will form their first impressions of a product when scrolling through a website. It must grab their attention through something other than touch. CMF is valuable here too with good color combinations and powerful imagery. We have to imagine how our consumers will evolve and what other products they are surrounded by because those materials and color combinations will affect how a product is perceived as it will share the same space. For example, after a kitchen remodel, a user might want to match their pan set with their appliances or their new kitchen look. Understanding what is in their kitchen can help us design a product that the user will connect with emotionally because it matches their surroundings perfectly.

CMF can be subtle and yet have a strong impact. One interesting example is the popularity of the color green after the pandemic. Being quarantined for so long disconnected people from nature. As a result, they added nature to their homes by, for instance, buying indoor plants. We are attracted to what is familiar and form connections based on visual impressions. We also assign lasting symbols to different color combinations. Because of green’s familiarity and association with nature, it can redefine consumers’ surroundings. This palette has expanded into several categories, such as kitchens, decor, and even tech. In 2023, the National Kitchen & Bath Association predicted that green was going to be one of the top colors for kitchens in upcoming years. Swarovski, which has primarily used a deep blue for its packaging and branding, redesigned its stores with completely green interiors. Understanding these consumer evolutions and noticing how familiarity affects decision-making will help us satisfy and bring value to customer desires.

CMF is an important part of a greater whole when conveying a brand’s experience and goals. Have you ever noticed how in an airport, where there are multiple coffee

IDSA .ORG 28

shops and coffee options, Starbucks always has the longest line? Standing in a queue feels good when you’re surrounded by beautifully designed merchandise in a cozy, inviting store, which is part of Starbucks’ brand. The environment created through the strategic use of color, texture, and materials can transform a mundane waiting period into a pleasant experience. The visual appeal of the surroundings diverts your attention, making the wait time seem shorter and more enjoyable. On the contrary, waiting in a queue where the surroundings offer nothing of interest might even stop you from wanting that coffee because of the negative feelings you have about waiting in line. Analyzing consumer behaviors reveals that CMF significantly enhances a product’s value. Companies like Starbucks succeed by creating a memorable environment through careful attention to CMF.

Making an Impact Beyond Color

CMF does more than just make a product or space look good. It influences how consumers perceive a brand, their willingness to wait for a product, their emotional connection to it, and their decision to choose one brand over another. It is a powerful tool for creating brand differentiation and a lasting impression on consumers, and for developing brand loyalty due to the consumer’s familiarity and satisfaction with it.

Understanding our target user’s environment and lifestyle is key to making the correct CMF decisions. As industrial designers, we can take inspiration from how interior designers create multisensorial experiences by thoughtfully

selecting CMF. By thinking deeply about the contrast between hues, the use of patterns, and the juxtaposition of textures and materials, we can unleash an infinite number of visual experiences that can’t be missed.

Finally, look at consumer behaviors and understand how they are essential to making decisions in your design process. Start noticing how best-selling brands use CMF as a resource. Compare those successful CMF strategies with brands that are not selling as well and observe the gap. Ask yourselves how you would feel with one versus the other, as well as what factors are causing that feeling. By understanding and leveraging these consumer behaviors, we can create products that not only captivate users visually but also resonate with their emotions and experiences. Let these insights guide your design process and decisions, enabling you to create products that truly connect with your consumers and stand out in the marketplace. Now sit back and ask yourself, when have you been seduced by CMF?

Hint: Look at the color of your phone.

—Daniela García García danielag.create@gmail.com

29 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

Daniela García García is a Colombian industrial designer and CMF specialist at Sprout Studios. She is driven by the desire for improvement and change.

The green-infused interior of the Swarovski store in Barcelona, Spain.

A CONSUMER’S GUIDE TO RATIONALIZATION SEDUCTION

Aesthetic beauty, style, or streamlined functionality that makes products tempting or irresistible—is that seductive product design? Should we trust that desire?

This is a meditation on seductive design and the acquisition of designed objects. The purpose is to provoke thought around the subject without defining the objects or products. There are no images so that readers will rely on their product knowledge base and desire for designed products.

Desire

How does it feel to desire a product or object? Think of one thing you wish to acquire right now. Does acquisition conquer desire? The concept of ownership should lead to a feeling of wholeness, but once acquired, we often realize that the void is never truly filled. There is always something else to be acquired, created, desired, or conquered. The old can become new with a new skin, an admirer, or adoration of some kind. The admiration might be for the form, content, or perceived worth of an object. We chase our desire through the acquisition of seductive things. We fill spaces, holes, and gaps with newer and better or older and more sentimental

objects. The new attempts to trump the old by replacing it with improved function and refined visual appearance and characteristics that make it unique.

The cycle becomes redefined by loss, replacement, and the hope of curing all sense of need. The cost of the cycle can be high at times; some things cannot be so easily replaced. Often, after the seduction of the new wears off, we are left to analyze and compare the new with the old. The seduction of the new may dissipate once flaws are discovered through use. The seduction fades and the object now becomes the old and known, which may give us a sense of comfort in sentiment, repetition, and reliability because once the old was new and seductive too.

Can one ever be satiated for long?

Considerations

Acquisition for acquisition’s sake, or to acquire that which we lack? Does the seduction of a design drive you to acquire based on need or superfluous wants? How do you measure the desire created by a seductive design? What emotions drive our purchasing decisions?

In The Laws of Simplicity, John Maeda states, “More emotions are better than less.” If this is true, then we might

IDSA .ORG 30

[insert your mental product image here]

be easily seduced by any product that creates strong emotions in us.

Questions to ask yourself when deciding what products to add to your daily life:

• What will it add to my life? Why do I need it? Will it save time? Is it intuitive? Is it beautiful?

• What value does it have emotionally? Mentally? Monetarily?

• Can I replace it, or will technology demand that I replace it once a new, more advanced solution or seductive aesthetic arrives to market (planned obsolescence)?

Products might command a consumer’s attention for any number of reasons. They may evoke emotions, such

as comfort, pride of ownership, exclusivity, ease of use, consistency, tactile appeal, aesthetic delight, proportional conformity, and many others. In Why We Buy, Paco Underhill says, “The products you buy turn you into that other, idealized version of yourself.”

We feel empowered by the acquisition of what we consider to be the best or the cheapest or the most useful or intuitive. Each consumer has their own criteria when considering a purchase: Will it coexist well in my designed life, or will it send me in a new direction, on a new path, demanding that I change or update all other aspects of my life to adapt? Will it quench my longing for beauty or function, or does it require additions to be complete as a collection might or a product that demands more products

31 INNOVATION SPRING 2024

[insert your second mental product image here]

to function optimally (for example, a smartphone requires a case, earbuds, a screen protector, a power cable, etc.)?

One product may replace three or more (for example, a smartphone takes the place of a phone, camera, and speaker). But do you spend more or less money to acquire these separately or as one product, and does it actually eliminate the need to have these separately for another purpose or scenario?

Quality and size may dictate the need for multiples. While seduced by a small, portable speaker, you might own other speaker sets that serve different purposes. Is less more in this case? Many of us want more under the guise of wanting less in a smaller, more precise product.

We are seduced by the newest, most advanced, and most pleasing aesthetic design. We might also be seduced by a brand name. We may buy to compete with our peers.

For all of this we pay a premium. The perceived value of these attributes goes up in a shoe just as it does for the newest technology. Is there a limit to what we will spend to have what we desire?

Trust and Expectations

Is seduction a feeling of trust? Do we place our trust in the newest and most advanced technologies until proven otherwise? If we are not the creators of the seductive product or technology, then we may come to our own conclusions as early adopters while others wait for reviews to help parcel out any skepticism. At times, we wait until we have no choice, and the obsolescence of our previous seductive product forces the cycle of seduction to begin again. We must then choose a newer product with new attributes and design to replace our now obsolete product.

We are often left with no choice but to trust in the new as the old dissipates.

What do we expect the new seductive product to offer us? What promises does it make or what problems do we expect it to solve for us? Can it solve problems or streamline our lives in such a way that its acquisition and excitement remain foremost in our minds? Is it promising us a new way of existing or functioning? How long can the meeting of our expectations remain additive enough to keep the product seductive to us? When does that promise and our expectations wear off? Is it when the next seduction arrives, shiny or matte, smooth or textured, black, white or multicolored, large or small?

The Cycle

The cycle of creation depends on acquisition, acquisition depends on the promise of new and better, and aesthetic beauty or temptation encourages acquisition. The new and novel becomes the old and trusted or the old and abandoned, spurring the need for creation and acquisition to repeat. This cycle lives in the hope and expectation of product design and in the dark corners of our closets and landfills. I would ask that as designers and consumers we ruminate on these questions before creating and acquiring.

—Chelsea Kostek, IDSA corporealdesignllc@gmail.com

Chelsea Kostek is the chair of industrial design at Paier College and is involved in wearable medical design and softgoods design through Corporeal Design.

IDSA .ORG 32

The curves flow

From bumper to bumper

Undulating, alluring

The color pulses

Vibrating beneath

The power of

A throbbing motor

Breezes blow

Whispering gently

As flowers sway

Quietly brushing

The edges of the body

Encourages speed

And danger

Sweeping away All cares

Flies us

To a greener space

Imagined, designed

Conceived, created

Caressed by design

—Bruce Hannah hannahdesign@icloud.com

Bruce Hannah is a professor emeritus at Pratt Institute and designer of the Knoll Hannah Desk System, chosen as an IDSA Design of the Decade by IDSA in 1990.

SEDUCTION

SEDUCTION

SEDUCTION

HOW BEAUTIFUL DESIGN CAN BREAK THE CYCLE OF OVERCONSUMPTION

Our world is overdesigned. This is good news for the multitude of designers in the field and for the everincreasing number of students being seduced into the profession. It may also be good news for consumers since most mundane products are now beautifully and thoughtfully (over)designed. In fact, there is such a glut of gorgeous products that people have difficulty analyzing the available alternatives.

How can companies stand out in this cluttered marketplace? Seductive design appears to be the perfect answer: By using psychology, companies attract, entice, and engage customers, persuading them to perform a specific behavior, which often means purchasing a product, regardless of their actual needs.

In the past 10 years, an ever-growing number of companies and organizations have realized that while technology moves extremely fast, the human brain does not change as quickly. Since people reason in a way that is remarkably similar to how our ancient ancestors did,

the expansion of digital technology has brought about the explosion of behavioral design and along with it many ethical questions and conundrums. The late-stage capitalism prevalent in the Western world has created an onslaught of deceptive situations, often with the complicity of psychology, that push an endless stream of products to satisfy artificial needs that companies themselves have implanted into our brains.

Why Does It Work?

How does seductive design make a product irresistible? It involves understanding the human brain with its many biases and exploiting them. Humans have limited cognitive resources and, therefore, resort to helpful heuristics and shortcuts to allocate those resources efficiently. For example, people have an aversion to loss. Social media has leveraged our fear of missing out to increase engagement to the point of addiction. As social animals, we want to be accepted by our peers and follow what others do. This is why reviews

Opposite: Isolation, loneliness, and depression affect too many seniors. Yet many are hesitant to ask for help, or do not know how to. With a modern look that is miles away from a medical device, the Elli Q AI-powered assistant provides companionship, engages users with lively conversations, and helps them connect with family and friends. Best of all, its intuitive design requires no tech skills at all.

IDSA .ORG 34