Linking the old with the new

Summarising the first ten years of tertiary education at the Hawke’s Bay Community College, the Hawke’s Bay Herald Tribune told its readers in 1986 that the college ‘has grown from strength to strength and now caters for thousands of people…’1

To cope with this growth in 1985, John Harré’s final year as Director, the College was reorganised into six schools: Community Education, Trades Education, Business Studies, Office Skills and Systems, Nursing, and Science and Technology. The wananga had been established to coordinate Māori education; there were two learning centres in Waipukurau and Hastings. The College comprised numerous buildings. The most recent addition in 1986 was the Art and Craft Centre.

Ōtātara: People and place

By Linda BruceDuring a reunion of founding staff members at EIT in August 2012, Linda Bruce conducted five group interviews with John Harré, Para Matchitt, Jacob Scott, John Wise, Tareha O’Reilly (for his father, Denis), Nigel Hadfield, Bill Buxton, Ray Thorburn, William Boag, Dave Waugh and Jan Marie Cook.2 This section draws upon the information shared at that time.

The history of the arts at EIT demonstrates an adventure in innovation and in the role education can play in social development. Dr John Harré’s leadership enabled the visual arts to flourish at Ōtātara, a place of cultural, historic, and geographic importance. As Nigel Hadfield says: ‘It’s a beautiful place, it owns us of Ngāti Paarau and Waiohiki and Ngāti Kahungunu.’3

Art became the vehicle to enable community engagement with education in arts, and for Māori, in styles relevant to needs. John Harré was aware of the significance of cultural differences, appointing Para Matchitt as one of

What emerged from this process over a ten year period was the Ōtātara Art Centre, a complex of buildings put together by the art tutors, artists, students, work scheme workers, community art groups, and anyone who wanted to contribute to building the place.

89 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast Bana Beattie and Craft Design students in 1994the first tutors in 1975, later joined by Jacob Scott and Grey Wilde. The arts initiative set out with long term intergenerational goals and reflected the Community College philosophy of life-long learning and experiential learning, with creative expression seen as crucial to individual and community wellbeing.

A supportive administration allowed organic and intuitive development in the arts. What emerged from this process over a ten year period was the Ōtātara Art Centre, a complex of buildings put together by the art tutors, artists, students, work scheme workers, community art groups, and anyone who wanted to contribute to building the place. Ōtātara was a place for everyone, a place that creative process built.

Para Matchitt had attended training college, then studied with Gordon Tovey as a specialist Māori arts advisor. These advisors made an impact, introducing Māori arts into school curricula, and as artists developing contemporary Māori imagery. In the 1970s, art was regarded as a hobby by most people in New Zealand. Para arrived in Hawke’s Bay as a practicing professional artist, accomplished in many media. His dual talents – artistic and as facilitator of community projects – meant Para was eminently skilled to enable community engagement. In his words, ‘I was here because it was a developmental programme that people could take part in, whether they wanted to become an artist or a craftsperson or not, and to empower themselves to take more courage to cope with things.’4

The way Para Matchitt established the culture of programmes was important. Programmes were for people interested in creativity, but also provided an informal learning environment to address neglected aspects of learning experienced by many. There was freedom for people to explore creativity, while discovering important things about themselves. Tareha O’Reilly, Ngāti Paarau summarised the power of this holistic experience: ‘I see art as wairua, tinana, hinengaro, it incorporates all those facets, in connecting with it, is where you kind of ground yourself as a person.’5

Para established relationships in the community, an early and important one being with tangata whenua of Ōtātara Ngāti Paarau of Waiohiki Marae, just across the bridge. Para introduced to the community his interpretation of the Tovey vision, simply put – opening doors. This allowed people to operate with as little timetabling as possible, challenging people to follow their own creative interests. In 1976, John Wise wrote: ‘Since students arrange their own attendance times, there is no indication that they are going to attend on a regular basis and therefore no prepared structure is contemplated.’6 To some, this appeared vague and unorganised. Yet to manage it required the extraordinary skills of mastery of media, effective communication, and facilitation of individual creativity development. Of this John Harré said: ‘The doors that Para and Jacob were opening were doors that led into at least mind rooms, and it is how they furnished those mind rooms with thoughts and actions and philosophies and ethics that is equally important.’7

Para’s approach was, ‘I’m not your teacher, you know, I will facilitate something.’ 8 As an example, Don Pomana over four years built the whare nui for his marae, north of Nuhaka, because ‘members of our tribe need a place to call their own, instead of intruding on the hospitality of other tribes’.9

90 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

Girl Hawaiikirangi taaniko weaving at ŌtātaraDon explained that Para helped by providing the tools and some lessons in basic woodworking and carving. To finish the project the carving was slow, difficulty mastering the grain requiring practice and experience. At times Don wanted Para to take over completely, but he always refused. Don is now grateful in the knowledge that the job is virtually his own work.10

John Wise recalled seeing the Pakeke Lions printing triangular banners to give away, and Black Power gang members working at the other end of the on campus art room, screen printing posters for their first convention. ‘I was listening to all the banter that was going on between the two, and I thought it was a metaphor really for a lot of the work that we were trying to do. It was just human beings having a good time and enjoying each others’ company, yet I bet it was the first time those groups would ever have connected.’11

With a clear philosophy Para built community connections, holding courses on and off campus in response to community needs. The Māori art of making hinaaki was a part of the 1977 Summer School based at Kohupatiki Marae; the family course Māori Arts @ Wairoa learnt to make elegant, functional crayfish pots. Art was an effective bridging mechanism into the Māori community and Para established links with many marae. In the early days it was a struggle to break down conservative attitudes; progress was like “walking through mud”. Things started to open up with the help of flax. ‘Through Sam Rangihuna (Kohupatiki Marae) we organised a programme whereby pretty much every marae in the area brought in a flax plant and planted it up on the hill.’12 Ōtātara became a uniting place, weaving people and cultures together.

John Wise recalled seeing the Pakeke Lions printing triangular banners to give away, and Black Power gang members working at the other end of the on campus art room, screen printing posters for their first convention.

The first marae project involving the College was the Kohupatiki dining hall project. Para empowering locals to take control of their own project creating tukutuku and kowhaiwhai work. Mihiroa was a two-year marae project, completing a new dining hall that opened in 1979. Under Para’s supervision, Mihiroa whanau did all the building, carving, mural, and tukutuku work, extending tradition with input from high school and 1978 craft course students.

Jacob Scott began his involvement with part-time courses in 1976. Jacob remembered Para coming to Haumoana School as an arts advisor, in his red Jaguar. At break time Para took Jacob and some boys for a speedy drive ‘I mean it changed our lives’.13 Jacob had experience in advertising and graphic design, and was architectural assistant for his father, Māori architect John Scott. He brought a designers eye and exceptional draughtsmanship to the mix of skills of the arts team.

Major events instigated by College art tutors brought national artists and craftsmen to share knowledge and skills with the region. In conjunction with a 1978 exhibition of works by Ngā Puna Waihanga artists at the Hastings Cultural Centre, tutors organised a two-week Māori culture programme – Tirohia, rongahia, arohia (look, listen, take note) – of drama, poetry, films, lectures and crafts, providing activities for the public to participate in.

John Harré remembers Para and Jacob’s innovative use of tools and materials gaining huge respect from colleagues on campus. But with no access to Trades’ coveted tools, Para went to auctions, bringing back items they could fix up to use. New materials were regarded as a challenge. Wanting to know more about working with glass, in 1980 they instigated an Arts Council sponsored National Craft Conference at Hastings Cultural Centre, attended by 250 people. There were demonstrations of glass blowing, carving, enamel work, batik, and a crafts exhibition alongside the conference. The following week the first glass symposium was hosted at the Stables. Forty students learnt many techniques from tutors from the Auckland University of Fine Arts.14 This was community education in action.

The College maintained important strong links with Ngā Puna Waihanga, the national body of Māori Artists and Writers, an ongoing resource of people talent later providing tutors for the craft design programme. Relationships were built with the NZ Craft Council, QEII Arts Council, and the Department of Education. Cultural understanding was fostered when Para travelled to International Society for Education Through Art (INSEA) conferences, and by hosting artists in residences from around the Pacific. Ōtātara established a reputation as a dynamic, exciting, creative place.

Ōtātara established a reputation as a dynamic, exciting, creative place

In 1976, the art department began using the Stables on the hill behind the campus. Facilities were basic, but improvements and additions provided extra space for a growing number of participants and a range of media activities. Community craft groups were encouraged to use the Stables, with Community Education nurturing their establishment and growth. The potters were early enthusiasts, building kilns, and holding weekend and weeklong workshops, working together and teaching each other. Potter and art teacher Dave Waugh, was involved with Ōtātara from the beginning, initially through courses run for arts teachers. He was enthusiastic about the mana the place had: ‘It grew a kind of ethos that was paramount to the development of everything that came into the craft course later.’15

91 Linking the old with the new First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

Grey Wilde came to the College at this time from teaching art at St Joseph’s Maori Girls College. Jacob described Grey as ‘left of centre, he knew a lot about a lot of things. He was a wise man … He was clever, good with his hands, but particularly good with people, and good with students.’20 John Wise recalls Grey as a deep thinker, unafraid to speak the truth. When Grey stood up and opened his mouth everybody listened.21

The arts team worked deliberately to create a completely inclusive environment at Ōtātara, making use of people and resources on hand. So art students were working alongside work skill trainees and supervisors on building projects or digging the hill to use the clay on site to make bricks for paving, collaborating, co-operating, sharing the effort and the gains. To provide more workshop space a number of buildings were adapted or brought on site. However, it was a struggle with resources to make things happen. As Jacob said: ‘We were using everybody else’s materials that had already outlasted their usefulness for other people. We were building out of everybody else’s rubbish.’22

John Harré recalled that it was essential that before any skill training began, tutors had to work with people as individuals, to develop their self-respect and ability to cooperate. The core of many of these programmes was the beginning of selfrespect. People’s demeanour and attitude changed.

The Log Cabin began as a summer course, led by a visiting Canadian. Jacob recalls: ‘They got about four or five logs high and left us with the legacy, so we finished it off.’23 In 2015 ideaschool lecturer, Mazin Bahho, is converting the log cabin into a sustainable building for his PhD study.

As the site developed, foundation art and craft enterprises were established, including production of laminated tables, bone pendants, and flax products. The Flax Cottage was a special place at Ōtātara, made special by the weavers and their values. John Harré reflected that while the purpose was weaving and producing saleable goods, social interaction was equally important. Para said that weaving was the stable programme in the whole place.24 Jacob added that the women made terrific work, but they grounded everybody, set the tone, kept it ordered, a place that had a different type of order. 25

In 1977 the weavers formed the Ōtātara Roopu Raranga (Ōtātara weaving group). Paula Batt pioneered courses in flax weaving in response to renewed enthusiasm for using local materials, in particular harakeke (flax). Paula tutored work skills weaving courses, as well as teaching in the community, sometimes with assistance from students.26 Bana Beattie tried to resist the lure of harakeke, but was emotionally and systematically drawn into it by the women. She could see they loved it and wanted to experience that love. Eventually, Bana was hooked, finding fulfillment and a sense of self-worth in her work.27

The Flax Cottage was a special place at Ōtātara, made special by the weavers and their values.

From 1980, with support from Para and Jacob, the weavers held regular workshops, sharing skills and inviting skilled practitioners from around Aotearoa to teach. The Roopu weavers were introduced to other raranga resources, piingao and kie kie (weaving grasses), finding and gathering these materials. For flax weaving to become a realistic craft employment activity, sources had to be established. Para encouraged the best varieties of flax to be planted at Ōtātara and alongside the railway line south of Hastings to provide an ongoing resource.28

92 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast Ōtātara Stables – photo William Boagvisit as part of a cultural exchange; the trip supported by a QEII travel grant.16 In 1981, 39 students of varying abilities attended spinning, weaving, and dyeing courses; some students made their own loom at a workshop.

From 1978, Jacob worked with Para to establish the Stables and develop programmes. This led to a 20-week craft production course for 12 unemployed people, funded through the Departments of Education and Labour. The course encapsulated the Tovey values of connections to community, community projects, collaborative work, experiential learning, self-initiated projects as well as cultural understandings of Māori and Pakeha. A first of its kind, the course set the foundation for future craft training programmes.

In 1981, The Stables came under the management of the Ōtātara Trust and was renamed The Ōtātara Art and Craft Centre.

In 1981, The Stables came under the management of the Ōtātara Trust and was renamed The Ōtātara Art and Craft Centre. Serious work began to develop the Centre outside the Institution, to provide facilities for art and craft in the region. The vision was for workshops for training in a range of activities, space for displays, office space, and a kitchen and dining hall for hospitality. Recognition that tourism could expand meant the site needed to allow for this.

From 1978-1984, Bill Buxton was Community Policies Adviser at the Department of Internal Affairs. He became a roving troubleshooter to ‘identify gaps between existing (Government) policies and programmes, and emerging needs’.17 His belief in community development aligned with the College’s philosophy and the innovative approach it was taking to pressing social needs in the region, in particular the growing issue of unemployment.

Internal Affairs funded Jacob to run a Labour Department pilot scheme to develop programmes for facilities development, material preparation and prototype craft production. A successful one-year programme was extended for a further three years; Bill Buxton valued the Ōtātara programmes as they were ‘getting people into work that was going to help with their identity, their feeling of themselves, and at the same time learning a great deal’.18 John Harré recalled that it was essential that before any skill training began, tutors had to work with people as individuals, to develop their self-respect and ability to cooperate. The core of many of these programmes was the beginning of self-respect. People’s demeanour and attitude changed.19

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

93 Linking the old with the new

Chester Nealie, guest potter at the 1978 Summer School, oversaw building of a wood fired kiln. The following year 20 potters brought their wheels to a five day school with two Japanese “Living Legend” potters, Professor Yutaka Kondo and Mr Zenju Miyashita. Local potter, Bruce Martin, had invited the pair to Hawke’s Bay Potters kiln firing at The StablesBack:

Front: Greg Northe, Muffy, William Boag, Jacob Scott, Grey Wilde

By 1984, after an intense period of activity, the construction phase at Ōtātara was completed. Together Jacob and Grey, work scheme supervisors and teams of trainees had established a special place.29 The autonomy of the the Ōtātara Trust and their access to Labour Department funded work schemes had allowed the project to evolve, as John Harré recalls: ‘Not according to some sort of directed plan but as an organic process, and that created a sense of ownership for all those people involved.’30

The craft design programme was years in the making.

The craft design programme was years in the making. Among others, the Crafts Council of New Zealand had been putting pressure on the Department of Education for years and getting nowhere.31 Activities at Ōtātara identified a need in Hawke’s Bay for a full-time qualification in art/craft/design. Calling for training, Jacob said ‘professional attitude, professional skills, and standards of excellence are necessary to consolidate and develop an already growing industry. No industry can ask to be taken seriously that doesn’t take its training seriously.’32

Through the 1980s, Dr Ray Thorburn of the Department of Education had been developing guidelines for primary and secondary school art and craft education. He recognised that short courses, such as those provided at Ōtātara, did not provide enough time to build knowledge, skills, and confidence.

During 1984 there were a number of meetings to investigate tertiary craft training opportunities. Ray Thorburn led the initiative in his report Today Towards Tomorrow: Art/Craft & Design in Technical Institutes in New Zealand,33 outlining programmes to provide training for people wanting to become professional craftsmen. Ray talked about how creativity can lead to work, contributing to the economy. Approval was given for craft design qualifications to begin at ten polytechnics in 1986. Ray Thorburn valued the philosophy and culture of Ōtātara and Grey and Jacob were active participants in the formulation and writing up of the national curriculum guidelines. ‘In at ground level about what could be and how it should be organised.’34 Programme development was the design process in action, ‘the way Ray facilitated that whole development was really important, he is an artist too.’35

In 1985 the College Council had several craft course options and the future of Ōtātara to consider. It decided that a two year Craft Design Certificate programme would begin in 1986, based on campus. As new buildings would not be ready in time, the Ōtātara Art and Craft Centre was re-incorporated into the College to provide interim facilities.

Jacob Scott led implementation of the new qualifications, maintaining the cultural integrity established with Para and Grey at Ōtātara. Each institute beginning a craft design programme identified a focus; most focused on a medium. Here, the focus was people.

94 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

First intake for Craft Design Course 1986: Jan Marie Cook, Angela Sykes, Lei Tanabe, Lisa Hapi, Traecey Holder, Ngarimu, Lynette Horsefield, Kiri Tristram, Rangi KiuWith similarities to the Bauhaus School using artist educators, the course provided art and design learning in workshop based environments. Jacob became aware of Alan Neilson’s skills as a toolmaker, appointing him as Art School Technician, a pivotal role in workshop based learning. He is still Head Technician, the person who keeps everything working at ideaschool in 2015.

Initially Jacob was asked to begin the new craft design course with two pre-fabs. Winning the argument of values, he involved his father who maximised the building budget, designing four, multi-use, learning spaces that embodied the culture and community core of the programme. In a letter to College Council, Jacob stated: ‘It is important that any building developments for the art/craft and design course be given the same design and planning considerations that the art/craft and design course has as a basis for its core content.’36

Jan Marie Cook was one of the first intake of 14 full time students. She said: ‘This was the first time that I had anything to do with Maori and what a lovely introduction and a soft introduction, so people like me who come from a normal Pakeha family, it just became instilled in you and the values and thoughts and ways of thinking are just part of me now.’37

Jacob stated: ‘It is important that any building developments for the art/craft and design course be given the same design and planning considerations that the art/ craft and design course has as a basis for its core content.’

With the new art complex on campus in 1986 the renamed Ōtātara Arts Centre became a community based arts facility with studio spaces available to be rented. A development committee chaired by Grey Wilde managed the Centre which remaining an invaluable extension of the Art Department, offering workshop space to artists, craftspeople, present and past students, artists in residence, and community groups.

In 1990 the Kohia Ko Taikaka Anake exhibition opened at the Dominion Museum, Wellington. The exhibition comprised contemporary Māori art and featured work by Para Matchitt as a founder of the movement, with work by Jacob Scott included in the Continuation section. The Takitumu Hawke’s Bay Elaboration section demonstrated the philosophy of bi-culturalism fostered here. ‘The artists were Māori and Pakeha, most of whom have strong ties with the art department of the Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic.38 Exhibiting artists were: Julie Amoto, Anna Bowen, Juliet Bowen, Jan Marie Cook, Clare Coyle, David Evans, Dave Goodin, Dave Guerin, Joanne Kirikiri, Rangi Kiu, Alan Neilson, Wendy Nightingale, Bana Beattie, Ray Pomare, Rangi Robin, Tanya Robinson, Wi Smith, Jody Stent, Sam Te Tau, Riks Terstappen, Mahea Tomoana, and Dave Waugh.

In 1991, Julia van Helden and David Trubridge received Craft Council grants for artist residencies at Otatara. The art school hosted The Pine Symposium in 1993 with funding from Creative New Zealand. This major event hosted international, national, and local artists to work on campus and at Ōtātara in a weeklong event investigating the abundant local resource of pine as a potential creative material. A book, Pinus Radiata,39 documents the event. In 2004 the Ōtātara buildings were demolished. At the reunion hui Nigel Hadfield said:

The Ōtātara Craft Centre sort of brought Ōtātara to life and in some ways started the work. The trees were planted, that’s people warming the site, ‘cause it was cold…. Joe Northover lifted the mauri, saying you can only take a part of it, because it is rooted in this place. Spiritually it was taken; physically some of the building materials were merged and integrated into some homes, and into the Waiohiki Creative Arts Village. The Centre was not necessarily built for permanence, but it is important to think about permanence and sustainability for the people.40 Ōtātara was a special place created by an amazing community of people. Perceived by some as radical, John Wise says of Ōtātara ‘the difference grew out of the process and so what eventuated wasn’t different for the people who were there, it was only different for people looking from the outside.’41

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

95 Linking the old with the new

Fred Graham visiting artist workshop, Craft Design students installing collaborative sculpture in 1989?ideaschool – Visual Arts and Design

ideaschool has its origins in the Otatara Arts & Crafts Centre, its development and mode of operation, providing a template nationally for creativity as a vocation.

The initial two year Craft Design Certificate course begun in 1986 was extended to become a three year Level 7 Diploma in Visual Arts & Design in 1993. This was further developed into the degree programme, the Bachelor in Visual Arts & Design that began in 1999. These programmes continued the philosophy of selfdirected learning embedded within a bicultural context.

From the beginning the arts courses here developed in response to community needs, embracing the concept that “anything is possible”. Forty years later in 2015 this philosophy of student centred learning drives the current project based learning in the Bachelor of Visual Arts & Design. The three year programme, rewritten to begin in 2013, empowers students to develop their ideas and individual creative practice with tuition and guidance across both visual arts and design disciplines. Access to extensive workshops and technologies, choice to work individually or in collaborative and community projects, prepare students with personal and professional skills to be creatively adaptable in this fast changing world. From 14 full-

The Otatara Arts & Crafts Centre, its development and mode of operation, provided a template nationally for creativity as a vocation.

time students in 1986 ideaschool has grown to have 250 students in 2015. They study Visual Arts & Design, Screen Production, Fashion and a new programme, Contemporary Music, that began in 2012 under the leadership of Tom Pierard.42 Alan Neilson, technician since 1987, has witnessed first-hand the development of creative progammes at the Eastern Institute of Technology. The

initial course developed design and technical skills to apply to media, with graduating students becoming self-employed artists and craftspeople. He observes that students still follow their individual creativity into professional careers, are industry ready and able to tackle most design related jobs. The community feeling remains in ideaschool where students and tutors gather in the courtyard for meals, to socialize and share ideas. The course emphasis it still to let the individual develop and express themselves in their own way. ideaschool graduates have achieved national recognition as practicing self-employed artists, art teachers, design creatives, curators, community arts workers, and digital media creatives. Graduates have also been accepted for art residencies nationally and internationally, have work in public gallery collections, are winners of international and national design awards, and are actively participating in the creative culture of our community.

96 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast Jacob Scott (1996) Ceramic tiles guiding visitors to the EIT Reception. Foundation Arts Tutor and Head of School. Ōtātara: people & place hui forum, August 2012 From left to right: John Wise as facilitator, seated Para Matchitt, John Harré, Jacob Scott, Ray Thorburn.Hayden Maunsell

Years of study: 2010-13

Study & Work history: Bachelor of Visual Arts & Design

Hayden Maunsell, with his lamp, titled Dark, selected for the 2013 International Trade Fair for Skilled Trades, Munich.

In 2013 EIT ideaschool student Hayden Maunsell was awarded Creative New Zealand funding to travel to Munich for Talente – a five-day exhibition held annually as part of the International Trade Fair for Skilled Trades.

The 27-year-old was one of four young New Zealand artists specialising in design, technology and craft/object art who accompanied work selected for the five-day expo. Of 600 entries from young designers and artisans worldwide, just 100 were chosen for Talente.

Hayden’s successful concepts were for two table lamps. Titled Dawn and Dusk, they combined traditional and contemporary materials – timber and coloured perspex – in their bases, while the distinctive bulb in each lamp created different mood lighting.

Both designs were Level 6 projects for the EIT degree and one sold at the expo. Then in his final year of his Bachelor of Visual Arts and Design, Hayden said of his study at EIT ‘I’ve made friends and it’s like a family, the arts and design section.’

Stretching out his travel to visit exhibitions and galleries in Dresden, Prague and Berlin as well as in Munich, Hayden was able to get back to Hawke’s Bay to see his sister Louise graduate from EIT with her Bachelor of Visual Arts and Design.1

In 2015 Hayden is employed at EIT ideaschool as a design technician and has recently completed a masters degree. 43

Amanda O’Donnell

Raewyn Paterson (right)

Years of study: 2006-2010

Study & Work history: Bacholar of Visual Arts & Design

In 2009, First-year Bachelor of Visual Arts & Design students majoring in 3D-design recently took part in a competition organised by Keirunga Gardens Heritage Action Society to design gates for the main entrance to the Havelock North reserve. The Keirunga Gardens Heritage Action Society wanted gates for the main entrance to the park in Pufflett Road. However, the society, liking both Amanda and Raewyn’s concepts, agreed a second set of gates could also be installed at the Tanner Street approach. ‘As you can imagine, it was hard for us to decide among the assortment submitted to our group by the students and others.’ The society wrote to class lecturer Mazin Bahho. ‘We finally decided on two designs to present to the Hastings District Council – Raewyn’s tui gates and Amanda’s oak tree gates.’44

Amanda says her concept was inspired by oak trees in Arthur’s Path, a secluded and scenic gully in the gardens. She envisages her gates in Cor-ten steel, a durable and naturally rusted material that is also very weather proof. Drawing on the meaning of keirunga, a Maori word meaning “a place on high”, Raewyn looked to the birdlife in the tree canopy for her concept. Her design features two tuis – one worked onto each leaf of the gate.

The designs have been ratified by the council’s Landmarks Consultation Group and the society is fundraising for their construction. ‘It’s been inspiring to have our work acknowledged in this way,’ they say. ‘It’s an honour to know our designs will feature in the gardens and help preserve their beauty for others to appreciate.’

Amanda’s current practice still revolves around her bi-cultural identity and relationships with natural environments. She enjoys collaborative projects and work that develops community as well as organising exhibitions. Raewyn is a temporary member of staff within the ideaschool. What I do as a painter is create paintings and try and sell them, try and get exposure for them. I’m living off my art work.45

Graduates have also been accepted for art residencies nationally and internationally, have work in public gallery collections, winners of international and national design awards, and are actively participating in the creative culture of our community.

Ecodeviant, Paula Taaffe.

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

97 Linking the old with the new

(left) Designer gates Havelock North’s Keirunga Gardens.ideaschool prepares students for a real world career in the creative fields where individual talent and collaborative projects converge.

98 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

Jekyll & Hyde, Jill Webster

Tip of the Tongue, Nigel Roberts

The Talisman Project, Roger Kelly

The Labours: Time With The Rabbits, Wellesley Binding

Schools Out, Peter Baker

98 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

Jekyll & Hyde, Jill Webster

Tip of the Tongue, Nigel Roberts

The Talisman Project, Roger Kelly

The Labours: Time With The Rabbits, Wellesley Binding

Schools Out, Peter Baker

Screen Production

The screen production programme got off to a humble start on 15 July 1995, operating from a chemistry lab and a room next to it at Karamu High School in Hastings. Back then the qualification was the Certificate in Video Production but as film technologies underwent rapid change so did the qualification, becoming the Certificate in Video and Electronic Media in 1998 and the Diploma in Screen Production in 2012.46

The staff member who wrote and re-wrote the curriculum and who led the programme for 19 years is Chris Verburg. His appointment to EIT was reported like this:

Chris is a find for EIT Hawke’s Bay as he has many years’ experience in the industry. He has worked for the DSIR audio-visual unit making scientific documentaries. He was a sound operator at the National Film Unit for 10 years, where he was sound-mixer on many New Zealand feature films such as Footrot Flats. After moving to Hawke’s Bay from Wellington, Chris joined Video East for two years and then began his own sound recording business here.47

Chris Verburg recalls that the programme was introduced as a result of local woman, Deborah Petrowski, encouraging the Dean of Arts and Social Sciences, Lester Finch, to offer such programme. Once the programme became available, Deborah enrolled and graduated, and then by 2005 her son Ed was enrolled in the programme.

Since its inception, the programme has been full every year, with enrolments closing three to four months prior to the programme commencing each year.

99 Linking the old with the new First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast Jose Auras Lobos and Deborah Petrowski with Chris Verburg (1995)Film Studio at the Hastings campus in the 1990s.

At the start, it was a good thing that Chris Verburg was not only innovative but also relaxed about his work environment. He takes up the story:

Back when I started there were no facilities for video…. and we only had one computer in the first year. It was the time of video on tape….In those days video was relatively new and it was a growing market. When I started Lester Finch was the Dean and Mandy Pentecost was the Section Manager.

Dedicated solely to students, the screen production centre is deemed to be one of the best-equipped screen production teaching facilities in a New Zealand tertiary institution.

I was brought on board to write the programme and shunted into unit standards. I ignored that and with the input and help of local industry, adopted a project based learning system. We wanted the programme to imitate real life and we based the lessons around it. I was in the right place at the right time. Hawke’s Bay was a nice place to live and I had many years in the film industry.

Thrown in to develop the academic programme, I got help from Grey Wilde to shape and develop ideas. he was a real personality who ran staff training. In the early days we had 14-15 students in each intake and that has now increased to 18 (although we start with 20). It means we have 16-17 students in the second year. Since its inception, the programme has been full every year, with enrolments closing three to four months prior to the programme commencing each year.

I helped produce film for the fashion students, the drama students and the music students as well. I would tape their performances to train these students how to work with the film/tv production.

In 1999/2000 I became the Section Manager, first for the Hastings programmes, then at Taradale and became responsible for Visual Arts & Design for a year.

Fashion was run out of prefabs in Hastings; Drama ran out of the Assembly Room at the Hastings Opera House and the room next door was the editing room for Drama and Music. The other rooms down the corridor on the first floor were Music practice studios. Music also occupied a big front room on the lower floor. (1995 – 2002)

We were based in Hastings for eight years with the central point, administrative part at the Hastings Campus Centre where Business Studies were housed as well. We were quite independent with three staff (two part-time and one full-time); with Camera & Production Tutor, Jeff Drabble; Script Writing Tutor, John Holmes and Sound, Editing and all theory, myself. Over time we have grown to two to three part-time and two permanent staff at any given time. For example: Jeff

100 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

Drabble (who left after 12 years), Wayne Dobson became technician/editing tutor; Dr. Bridget Sutherland was the script writing tutor for four years; after that Chris Bennett (Coordinator in 2000) and Claire McCormick (present Coordinator) tutored in script writing. We still have the tripods and lights etc. from those early days because we are careful and frugal. We have very fancy equipment now but still make it lasts a long time.

Although we were very independent we sometimes felt quite cut off from Taradale. Although it did not hinder programme delivery it had some funny results, for five years we carried on teaching on Easter Tuesday not realising that the main campus had an extra day off. When we tried to contact people on the main campus we found no one was there!

For 3-4 years we were based at the old National secondary school library distribution building, across the road from the Hastings Central School. Two grey buildings with high ceilings which were good for studios and we stayed there until the John Harré Building opened on the Taradale campus in 2005.48

Centred around two large studios, the new facility included three editing suites, TV-computer editing stations for class teaching, a small sound studio, and a surround-sound theatre, which also doubles as a screening/classroom.

All 153 graduates of the programme along with film personalities were invited to the opening of the purpose built studios named after inaugural Director, Dr John Harré. Gaylene Preston (now Screen Production’s patron) presided over the opening. She and Chris Verburg had earlier worked on films together; Chris also knew of her family and schooling links to Napier. At the opening it was noted that in the period 1995 to 2005 EIT had become renowned for producing leading graduates with the Diploma in Video and Electronic Media. These included Peter Smith, Grip, who was part of the model-shoot team for 6foot2, a company owned by Peter Jackson. Another graduate, Robert Rowe, had become a producer. His second feature film Luella Millar was released in 2005. Two other known graduates were Paul Tomlinson, Director of Photography, and Wiremu Te Kani, Video Editor at Māori Television.49

Looking back, Chris Verburg notes that:

Of our students/graduates, we have people in top positions in Māori Television; Weta workshops and the manager of the TV station ‘Trackside’. I am very pleased with the success of students and how we are considered to be one of the better training schools for screen production; we have a solid reputation.

This reputation meant that industry colleagues often referred students to the EIT programme. This was the case in 2005 when a past colleague who works with Peter Jackson, sent Stephanie Ng to EIT for training.

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

101 Linking the old with the new

John Harré with film producer Gaylene Preston at the opening of the new film studio, named in John’s honour.Stefanie Ng

Years of study 2006-2007

Study & Work history: Diploma in Video and Electronic Media 2007-2014: First credit was on The Lovely Bones, District Nine, The Adventures of Tin-Tin, Hobbit 1 and 2., 2014: First assistant sound editor for Hobbit 3.

Quote: Park Road Post Production Supervising Sound Editor, Brent Burge, says Stefanie worked hard and deserved her place in the industry. ‘Stef has blasted through the roof and is now an integral part of the team. On The Hobbit, she will carry the load of first assistant sound editor.’

Stefanie: In high school, I had no idea that sound editing was a job; that everything you hear in every movie has been painstakingly recorded and placed to help tell the story. I didn’t realise until I saw the sound guys whirling a cheese grater around on a string on a Lord of the Rings DVD – it looked like heaps of fun!

John Neill (Head of Sound at Park Road Post in Miramar, Wellington) recommended that I complete the Diploma in Video and Electronic Media at the Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT). The course was very hands-on, and had an emphasis on practical skills in the screen industry – something that wasn’t included in other tertiary courses I had looked at. The tutors were great and very generous with their time – they had all been working in the screen industry for many years themselves.

After completing the two year course, I got a job as a trainee on Peter Jackson’s “The Lovely Bones”. It was an introduction to the real deal, and the life of a self-employed contractor. I also realised it wasn’t as glamorous as I had first thought as you work very long hours, and it can be quite stressful.

At the same time, it has been so satisfying to hear your work on the big screen. The skills and programs I had learnt at EIT were a great foundation, and I was able to learn a great deal more in the next few years (and still learning today!).

My training wasn’t limited to just sound - I also learnt about scriptwriting, lighting, camera and crew. This is a huge asset, as all of these departments work together to create the final product – the movie!

I have had a good run in the last five years. I am now first assistant sound editor on the Hobbit, and helping teach trainees myself. I have learn so much working with our post-production sound crew – they’re all so sharp, and I hope to keep learning from them for a long time yet. Last year our sound team was nominated for an Oscar for Best Sound Editing in a Feature Film for the second Hobbit film – a very proud moment!

I feel I have been quite lucky in the last few years. But I do believe that luck only gets you so far. When an opportunity arises, it is up to you what you do with it. The last few years have been a lot of hard work and commitment. I really enjoy working in film, and I am grateful that I have the opportunity to work in this industry in New Zealand.50

Fashion

Students were first able to study fashion as a short Training Opportunity Programme (TOPs) in the School of Community Education in 1991. Christina (Tina) Rhodes was recruited as Fashion Tutor by Jacob Scott, who was Head of Arts at the time. In 1992 Tina approached Cheryl Downie, then Manager of the Arthur Toye fabric retail shop in Napier, to teach pattern drafting. The fashion programme proved to be popular and was repeated. Students sewed on industrial machines and each intake ended with a parade of clothes the students had made.51

These early years are recalled by Ross Munro, then Facilities Officer. He observed that:

Tina [Christine Rhodes] in Fashion did not have much resourcing and would take me when sewing places closed down and we would pick up second-hand machines and borrow equipment. They got

102 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

Student Tessa Paaymans models her own design, 2012.the courses started from nothing. I recall John, the carpentry technician and I had untold fun setting up fashion shows and carting all the gear to places such as the top floor of the Cosmopolitan building on the Marine Parade, to the War Memorial, setting up outside Scholars Restaurant on the lawn. It was really brilliant being able to help, they were always grateful and the students pitched in also.52

The annual fashion event evolved into a celebration of talent: the fashion students’ designs; performances by the music and drama students; hair and make-up by the hairdressing and beauty therapy students, and food prepared and served by the food and beverage students. In 1993 the programme moved to the Hastings campus for two years and during this time it was also taught in Waipukurau. By 1995, the programme was back at Taradale and the student response was such that it went from being six months long to a full year basic introduction to the fashion industry in 1995.

By this time, students such as Clinton de Har of Hastings, and from the 1993 course, had gone on to graduate with a Diploma in Fashion Design from the Whanganui Polytechnic and had already been highly commended in the lifestyle section of the National Smokefree Fashion Awards.53 The relationship between the fashion staff in Hawke’s Bay and Whanganui has always been strong. For example, in 1997, English fashion designer Iain Archer, who developed the Whanganui Polytechnic fashion design degree, delivered week long workshops to the Hawkes Bay students. He was impressed with the calibre of their work and having completed the Hawke’s Bay introductory programme, many went on to study with him at Whanganui.

From the early days a field trip was organised for each group of students. Students were very involved in the planning of the trip, especially managing their budget. Accompanied by Christina Rhodes and Cheryl Downie, they went to such places as the Nelson Wearable Arts Awards, visited Massey University Wellington Fashion programme, as well as a number of fashion manufacturers. Students had an opportunity to be introduced to many aspects of the industry.

The level 3 one year full-time Fashion Apparel programme remained popular and in 2004 there was a decision to enrol two intakes of students. This required an additional tutor and Cheryl Downie was offered a limited tenure position. Cheryl and Christina Rhodes made plans about future possibilities for the programme. They made contact with other providers who would take graduates from EIT’s programme and proceeded to position their programme to lead to a degree qualification as offered at Massey University (Wellington) or the Whanganui Polytechnic.54

As the level 3 Fashion programme became more successful, EIT developed it further. In 2009 it was re-written to become NZQA unit standards based. Approval was also given to have a second year full-time level 4 fashion apparel qualification which provides advanced skills and knowledge to enter the fashion industry, including the running of a business. After years of limited tenure and proportional contracts, Cheryl Downie finally became a permanent, full-time staff member in 2010. At the beginning of 2013 she became the Fashion Programme Coordinator, freeing up Christina Rhodes to teach fulltime. In addition to Cheryl and Christina, the programme has a part-time design illustrator tutor.55

The staff are very proud of their many graduates who have won national and international fashion award sections and who have been able to use their skills as dressmakers and designers.

103 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast First of the annual Fashion Shows held on the Māori Studies ‘verandah catwalk’ March, 1992. (Daily Telegraph, 28 March, 1992). Student Misty Ratima (right) with her winning design in the 2014 Hokonui Fashion Awards, modelled by her daughther Ocean Ratima. Student Tory Tiopira designs 2012.The staff are very proud of their many graduates who have won national and international fashion award sections and who have been able to use their skills as dressmakers and designers. These include Andrea Lambert (1994) who now works for the renowned johji yamamoto label in London; Leigh Finlayson (1994) who is overseas buyer (women’s wear) for The Warehouse Ltd; Kirsha Whitcher (1995) who went to Whanganui and completed a Bachelor of Fashion and now has her own label called Salasai; Toni Mitchell (1996) who having completed her degree at Massey went on to work with Trelise Cooper; and Andrea Yee (formerly Potts) (1997) who now runs her own bridal business, RSVP, and own label Silverlily, in Hastings.

John Rose (MA., Dip.Tch.) Director 1986-1991.

John Rose succeeded John Harré as the Director of the Hawke’s Bay Community College. His stewardship was relatively brief but occurred in a period associated with turbulent political and economic change. John Rose inherited the College at one of the most difficult times in its history. One of his major challenges therefore was to advocate for greater, fairer, and sustained funding, realising that the rapidly growing institution required a longer term development strategy.

John Rose had a background in secondary education, including Head of the Social Studies Department at Central Hawke’s Bay College, Lecturer at Auckland’s Secondary Teachers’ College, and at the time of his appointment in 1986 was the principal of Penrose High School in South Auckland. Like his predecessor, John Harré, he had worked overseas, having spent three years in Sarawak advising on curriculum development and serving as Inspector of Schools.

John Rose was selected from a large pool of applicants by the Hawke’s Bay Community College Council, who held a social occasion for the staff to meet those short-listed (and their partners) the evening before he was interviewed. There were 17 questions identified by Council including ‘What is your policy on affirmative action? What are three current issues being discussed by Māori people?’ While these questions reflected the legacy of John Harré, Council Minutes make clear that members were also looking for a point of difference from the Harré public image, which was usually casually and colourfully dressed. Hence, another question was prefaced with `Just how a director of the college who “is the college” in the eyes of the community might present himself?’ With the clean shaven, suited school principal John Rose sitting before them it was clear they liked what they saw and his answer to the question `What image would you wish to project and how would you go about it?’56

But appearance was the least of John Rose’s worries when he took up the Director’s role. As he commented later, ‘The college was under-resourced and under-funded, in comparison with similar tertiary institutions.’57 Coming from the secondary school environment with an established funding stream and accountability systems, John Rose could see what needed to be done. He set about implementing planning, administrative, accountability, and reporting pathways. This policy driven culture shift would later lead to him being described by staff as “a systems man”. In his first year, for example, he introduced a teaching evaluation process; had all new staff members undertake an induction programme and extended this to the six new council members.58 What John Rose realised was that there was a huge job ahead and to achieve it he needed a shared vision. By September 1986, John Rose, his management team, and Council were able to present this for the institution going forward.

Central to this newly stated philosophy was a commitment to respond to the social and economic climate, including providing adult retraining programmes.

104 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

Andrea Yee, RSVP Bridal, Hastings. Leigh Finlayson, International women’s wear buyer for The Warehouse Ltd. John Rose (1986)Philosophy and organisation

Philosophy

The college promotes the concepts of lifelong learning and social equity by providing access to educational resources. The college aims to enhance the quality of life of individuals and groups by serving their educational needs and interest and thus contributing to the welfare of the people of Hawke’s Bay.

Objectives:

l To create a learning environment which reflects the heritage and culture of New Zealand.

l To provide vocational education to help meet local and national needs.

l To provide opportunities for individual growth and development.

l To assist the community to identify its educational needs and ensure access for all members of the community to re-engage in continuing education.

l To facilitate community discussion and decision-making of public issues.

Functions

of Council

l Accepts responsibility for, and works in terms of, the stated College philosophy and objectives.

l Supports the Director and staff in the implementation of College policy.

l Has a public relations function to promote public awareness of the College and its resources.

l Council members represent a range of community interests and have a role in monitoring College activity. Staff are finally accountable to the council.

l Council provides a vehicle for bringing the community or lay persons view into the College and may initiate discussion on matters of public interest.59

John Rose also wanted a mandate from Council to move the institution forward in line with a comprehensive education and building plan. He realised that both were essential to his arguments for increased government funding and that a name change would also likely assist that cause. At the end of 1986 Council agreed to an institutional name change, adding the word ‘polytechnic’. Importantly, the word ‘community’ was retained by the Council to reflect the unique community and vocational programmes offered. Most believed that the name Hawke’s Bay Community Polytechnic was the most appropriate for the institution and this was sent to Wellington to be gazetted. Just how or why this name was changed in Wellington remains unclear, but someone at the Department of Education in Wellington decided to remove the word ‘community’, which was not in line with typical nomenclature. In any event the name of the institution was gazetted as the Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. In and of itself this might not seem a big deal but locally the name change was met with vociferous protest.

Central to this newly stated philosophy was a commitment to respond to the social and economic climate, including providing adult retraining programmes.

Pat Magill, a former Council member, and others sought to retain the community emphasis and the institutional response as sought by individuals and community groups. These were courses and programmes not available elsewhere in the region and the College had provided expertise to deliver them across ten years. As the proponents argued, whilst life-learning was important in its own right, adults completing a parenting, art and craft, literacy, youth worker’s, or creative writing workshop, for example, also discovered the range of other educational opportunities available at the College. It was common for community education to provide the staircasing leading to formal qualifications.

Admirable as this was, John Rose and the Council were also mindful of their political masters, on whom they were dependent for funding. In Wellington, the view was increasingly that community education belonged in the secondary school night classes, rather than in tertiary continuing education programmes and although government subsidised them, the ideology of “user-pays” was taking hold. That is, adults wanting hobbies classes should pay for them and high schools, which were easily accessible throughout the country, had the facilities to provide them. Just as importantly, the secondary school sector knew just how important night classes were for meeting their own budgetary needs. They were also a powerful lobby group.

A petition was got up by Pat Magill in March 1987 and with feelings running high more than 2000 signatures were collected and presented to Council, asking it to go back to Wellington and have the title overturned. Council voted against doing this but, like the community from where it came, was divided on the issue. Council member Tom Johnson, a supporter of retaining Community in the title, cut to the chase saying that `he was concerned that word may have been dropped in an attempt to receive more funding through name uniformity’, explaining that ‘the new title is used by many tertiary institutes which receive more fund allocations from the government’.60

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

105 Linking the old with the new

As a formally constituted polytechnic in Hawke’s Bay, John Rose and the Council were receiving strong messages from Wellington, which was essentially to move away from community programmes and focus on programmes directly linked to vocational education and training. This view was reinforced at the local level by Hastings Mayor, Jeremy Dwyer. Knowing full well the impact of the Whakatu meat works closure and high unemployment rates in his community, Dwyer endorsed the name change as an `interesting, timely, and thoughtful move, particularly in the present climate of ‘employment challenge for the province’, before going on to signal ‘we will now see the emphasis placed squarely on skills training that is relevant to Hawke’s Bay’.61

While John Rose had good programmes and high calibre staff, he had too many students for the inadequate building spaces in which to teach them and at the point of having to turn students away. He did the sums and took to Council the comparative figures as evidence that Hawke’s Bay, as a region, was severely under-funded when it came to tertiary education. Having compared the local Hawke’s Bay population of

106 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coastover 100,000 with that of Waikato and the Manawatu, he argued that Hawke’s Bay was severely deprived of funding, given that these other provinces had teachers’ training colleges, universities, and polytechnics. Local Labour MP, Dr Bill Sutton, was called in to help promote the case for increased funding in Wellington and the Minister of Education, Russell Marshall, visited the campus in June 1987 to see the situation first-hand. At this time there was a village of 21 prefabs being used as classrooms, so John Rose took the opportunity to argue for permanent teaching blocks for Nursing, Health Studies, Science and Technology, a new library, and a student amenities building.

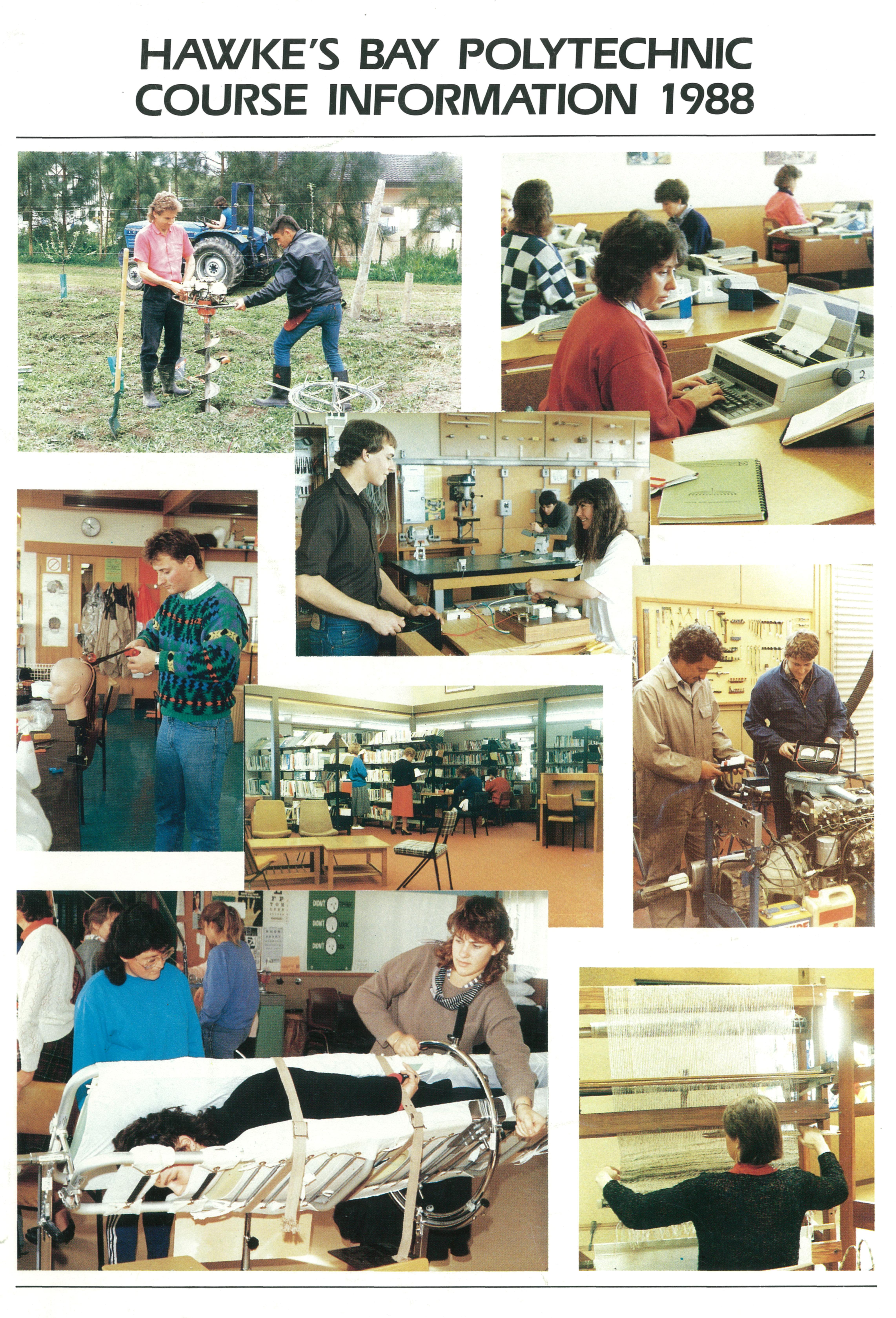

All the while, and despite the poor facilities, staff introduced innovative new courses to meet the needs of both local industry and students; courses for which they previously would have had to leave the region to study. This included the first viticulture course in New Zealand, a pre-entry course for mechanical engineers, a Māori journalism course, and a tourism course. By the time Phil Goff, the Assistant Minister of Education, visited in March 1988, there was a further body of evidence to indicate the Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic was working hard and delivering vocational programmes with successful outcomes for students. A short time later, government approval was forthcoming for the building programme John Rose sought.

However, just when progress seemed assured, the tertiary sector as a whole was turned upsidedown. Not only were all capital works put on hold, but the whole way institutions were to be administered, monitored, and funded was to undergo dramatic change. The tertiary reforms as they became known, meant that from the end of 1989, tertiary institutions would become the legal owners of their assets once they had paid these off at ten percent a year, the overall liability. As Hawke’s Bay argued, it was already on the backfoot and ten million dollars behind other institutions. What happened next was tantamount to farcical as the government offered $12.4 million dollars of funding, buildings were started only to have the government funding withdrawn again. This happened twice which meant that half-completed buildings were stranded. This nightmare situation was no doubt part of John Rose’s decision to resign at the end of 1990. In his last week as Director he spoke out expressing concern that government `has to invest in education’, stressing that: ‘If there is no investment in education long-term, the country doesn’t have a future.’ 62 Frustrated by funding battles and disappointed that despite his best efforts and those of the Council, he could make little headway in the current climate. It was no doubt a bitter sweet irony that in May 1991, the newly completed multi-classroom block, the John Rose Building, was officially opened and named in his honour. It is generally agreed by staff that John Rose led the institution through a very difficult period.

John Rose realised we were lagging in buildings infrastructure. He had good connections in Wellington and worked hard to establish facilities and did a good job with that. (Kerry Marshall, then HOS, Business Studies)63

However, there were the annual Christmas garden parties he hosted on the lawn of the Director’s house (the Hetley Homestead) where it was sunny, the food was posh, there were friendly people, and everyone went as part of a half a day off. (Sian Forlong-Ford, Lecturer, Applied Science)64

107 Linking the old with the new First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

The John Rose Building, home to Business Studies.growing regional tertiary institutions in the country with a corresponding committed building programme. Under the implementation of the 1990 Education Amendment Act, EIT was allocated $1 million dollars per year and expected to cover $10 million dollars of buildings already under construction. Tim Twist came out saying ‘he would fight for the money’ and he did. Aware of the impossible pressures on staff of having to teach in temporary buildings while introducing the new Bachelor of Nursing degree, a deal was negotiated with the Ministry of Education to pay for the Nursing block. However, in 1991 when the government threatened to withdraw capital works funding for two years, the Council raised funds itself in order that the Nursing building could be completed. Whilst this is only one example of the type of issue Tim Twist dealt with during his 17 year term as Council Chair, it nevertheless highlights his commitment and determination to provide quality higher education and related facilities for the region.

Reflecting on his 25 years association with EIT, Tim Twist wrote in his final report that ‘the job of Council is to govern, of course, and to support the management, the staff and the students. The harmony of our Council has made it not only possible, but greatly pleasurable for me to serve as a member and then as Chairman. I haven’t regretted a moment of my time and I will miss very much being an active part of the governance of EIT’ 174 At the chairing of his final meeting of Council on 2 December 2002, Ron Hall expressed on behalf of the Council, ‘appreciation of the tremendous service and wisdom brought to the Council by Mr Twist over the last 25 years’.175 The Twist Library remains a tribute to this legacy of governance.

Tim Twist died in 2014.

Notes

1 The Herald Tribune, 31 July 1986.

2 Interviews were conducted during the reunion on 17 & 18 August 2012.

The interviews are referred to by number and transcript page number in the references that follow.

3 Interview 1, Nigel Hadfield, 17 August 2012, p.8.

4 Interview 2, Para Matchitt, p.9.

5 Interview 4, Tareha O’Reilly, p.15.

6 Ōtātara Archives: D444.

7 Interview 5, John Harré, p.7.

8 Interview 2, Para Matchitt, p.13.

9 Ōtātara Archives: D550.

10 Ibid

11 Interview 3, John Wise, p.36.

12 Interview 2, Para Matchitt, p.13.

13 Interview 4, Jacob Scott, p.22.

14 Ōtātara Archives, D547.

15 Interview 5, Dave Waugh, p.4.

16 Ōtātara Archives: D527.

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

131 Linking the old with the new

17 Ibid D 432.

18 Interview 3, Bill Buxton, p.1.

19 Interview 3, John Harré, p.1.

20 Interview 1, Jacob Scott, pp.1-2.

21 Ibid John Wise, p.2.

22 Interview 3, Jacob Scott, p. 11.

23 Ibid p.6.

24 Ibid Para Matchitt, p.22. 25 Ibid Jacob Scott.

26 Ōtātara Archives: D477 Jody Stent 27 Ibid D:478 Bana Beattie CV.

28 Ibid D:481, Jody Stent 29 Interview 3, p.8-10.

30 Ibid,p.9 31 Interview 1, p.12.

32 Ōtātara Archives: D257. 33 Ibid D434. 34 Interview 1, p.3. 35 Ibid p.14. 36 Ōtātara Archives: D256. 37 Interview 5, Jan Marie Cook. 38 Ōtātara Archives: D339. 39 Ōtātara Archives, Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic (1993). Pinus Radiata: Sculpture Symposium, January 1993.

40 Interview 1, Nigel Hadfield, pp.9-10.

41 Interview 3, John Wise, p.10.

42 ideaschool history, Ōtātara Archive.

43 EIT Newsbrief, June 2013, p.2. 44 EIT News (January, 2011), p.3. 45 Ibid

46 Interview with Chris Verburg, 30 March 2015. 47 Polygram April 1996, p.17. 48 Interview with Chris Verburg, 30 March 2015. 49 Polygram April 1996, p.17.

50 Interview with Stefanie Ng, 26 June 2014. 51 Interview with Cheryl Downie, 25 July 2014.

52 Interview with Ross Munro, 21 August 2014. 53 Christina Rhodes, Scrapbook, March 27 1996. 54 Ibid 55 Ibid

56 Minutes of the Hawke’s Bay Communty College Council, 9 December 1985. 57 Moss, M. (1996). Coming of Age: A History of the Hawkes’s Bay Polytechnic 1975-1996. Waipukurau: CHB Print.

58 Minutes of the HBCC September 1986. 59 Ibid.

60 Daily Telegraph 17 March 1987, ‘2000 sign petition to restore word to title’.

61 Hawke’s Bay Herald Tribune, 4 April 1987, ‘Polytech idea palatable’.

62 Polygram, June (1991).

63 Interview with Kerry Marshall, 22 October 2013.

64 Interview with Sian Forlong-Ford, 27 May 2014.

65 Hawke’s Bay Community College Prospectus 1977 pp.20-29.

66 Ibid. (1981). p.21.

67 Ibid.

68 Interview with Judy McKelvie, 29 August 2014.

69 Hawke’s Bay Community Collect Prospectus 1985.

70 Press Release, 30 January 1986.

71 Daily Telegraph, 30 January 1986; Hawke’s Bay Herald Tribune, 8 May 1986.

72 Interview with Paul Hursthouse, 30 September 2014. 73 Ibid.

74 Applied Management 1993 Planner (back cover).

132 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

75 Interview with John Nelson, 4 April 2014.

76 Interview with Kerry Marshall, 22 October 2013.

77 Interview with Sally Woods, 27 March 2014.

78 Ibid.

79 Interview with John Nelson, 4 April 2014.

80 Ibid.

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid.

83 Hawkes Bay Herald Tribune, 7 August 2004.

84 Interview with Dr David Skelton, 10 April 2014.

85 Ibid.

86 Ibid.

87 Ibid.

88 Press Release by Mary Shanahan, 19 March 2012.

89 Ibid.

90 Interview with Ben Greville, 2 May 2014.

91 Ibid.

92 Interview with Amanda Price, 4 July 2014.

93 Interview with Rosemary Reeve, 20 May 2014.

94 Interview with Michael Verhaart, 20 May 2014.

95 Interview with Rosemary Reeve.

96 Interview with Steve Corich, 20 May 2014.

97 Hawke’s Bay Community College, Nursing Studies Department. 3 year full-time comprehensive nursing course.

98 Interview with Susan Jacobs, 18 May 2015.

99 Ibid.

100 Hawke’s Bay Community College. 3 year comprehensive nursing course.

101 Ibid.

102 Hawke’s Bay Community College, Nursing Studies Department. Student handbook 1985.

103 Hawke’s Bay Community College. Nursing Studies Department. Staff Nursing Rag.

104 Interview with Margaret Richardson, 15 October 2014.

105 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

106 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. Course information 1989.

107 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

108 Ibid.

109 Eastern Institute of Technology. Annual Report 2012.

110 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

111 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. Course information 1989 p.19.

112 Cultural safety components of the Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic Nursing Programme [Media Release]. (29 June 1995).

113 Eastern Institute of Technology. Annual Report 2012.

114 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. Student handbook 1989.

115 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

116 Hawke’s Bay Community College. Prospectus 1983. p.55.

117 State Services Commission. (1998). Management of the state – the state sector act 1988. Retrieved from http://www.ssc.govt.nz/node/1395

118 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. School of Nursing and Health Studies: Nursing tutor handbook

119 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. Corporate plan 1992-1994.

120 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. Strategic plan 1993-2000.

121 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

122 Moss, (1996).

123 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic Faculty of Health Studies. Handbook for comprehensive nursing students diploma/degree

124 Ibid

125 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

126 Daily Telegraph, 14 July 1995. First polytechnic degree on track’.

127 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

128 Ibid

129 Ibid

130 Personal communication, Susan Jacobs to Kay Morris Matthews, 11 May 2015.

131 Interview with Tia Mark, 11 February 2015.

132 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast

133 Linking the old with the new

133 Ibid.

134 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic. Strategic plan 1993-2000.

135 Personal communication, Marietta Foote to Kay Morris Matthews, 15 June 2015.

136 Eastern Institute of Technology. Prospectus 2003.

137 Personal communication, Marietta Foote to Kay Morris Matthews.

138 EIT awards its first Master’s degrees [Media Release]. 16 March 2005.

139 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

140 EIT awards its first master’s degrees [Media Release].

141 With thanks to Mary Shanahan, EIT News, October, 2010, p.15.

142 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

143 Personal communication, Susan Jacobs to Kay Morris Matthews.

144 Hawke’s Bay Polytechnic Strategic plan 1993-2000 p.7.

145 Ibid.

146 Interview with Judie Gardiner, 29 October 2014.

147 Interview with Susan Jacobs.

148 This section draws upon a round-table interview with the following colleagues from Hospitality and Tourism, Friday 16 May 2014, Scholars Restaurant: Chris Toomey (1993), Celia Kurta (1996), Mark Caves (1999), Sue McCarthy (1999), Nikki Lloyd (2005), and Jenny Robertson (current HOS).

149 Moss, (1996). p.90.

150 Interview with Mark Caves, 16 May 2014.

151 Interview with Sue McCarthy and Nikki Lloyd, 16 May 2014.

152 With thanks to Mary Shanahan, Our EIT, November 2013, p.2.

153 Interview with Mark Caves and Celia Kurta, 16 May 2014.

154 Hawke’s Bay Community College Prospectus, 1977. p.7; Nursing Studies Department. Student handbook 1984.

155 Ibid (1977) p.7.

156 Pollock, K. (2012). Tertiary education – tertiary reform from the 1980s. Te Ara: The encyclopedia of New Zealand Retrieved from http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/tertiary-education/page-4

157 Moss, (1996).

158 Ibid.

159 Pollock, K. (2012).

160 Moss, (1996). 161 Ibid.

162 Tertiary Education Union. History. Retrieved from http://teu.ac.nz/about/history/ 163 Tertiary Institutes Allied Staff Association. About TIASA. Retrieved from http://tiasa.org.nz/about.html

164 Olsen, E. (2013). Unions and employee organisations – unions after 1960. In Te ara: The encyclopedia of New Zealand Retrieved from http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/unions-and-employee-organisations/page-7 165 Pollock, K. (2012). Tertiary education – polytechnics before 1990. In Te Ara: The encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/tertiary-education/page-2

166 Education Act 1989 s 206. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1989/0080/latest/DLM184646.html

167 Pollock, K. (2012). Tertiary education – tertiary sector reform from the 1980s. In Te Ara: The encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/tertiary-education/page-4

168 Prebble, M. (2015). State services and the State Services Commission – role of central agencies. In Te Ara: The encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/diagram/33063/state-sector-state-services-and-public-service

169 Interview with Evan Jones and Gordon Reid, 19 June 2015.

170 Dobbie, A. (1977). Libraries in continuing education. Unpublished article.

171 With thanks to Mary Shanahan, EIT News June 2011.

172 Eastern Institute of Technology Annual Report 2002. p.13.

173 Moss, M. (1996). p.92.

174 Eastern Institute of Technology Annual Report 2002. pp.8-9

175 EIT Council Minutes, 2 December 2002.

134 Linking the old with the new

First to see the Light: 40 years of Higher Education on the East Coast