a lmmaker or work in the industry, IDA has a membership that ts your needs and budget. Join 3500+ members from 85+ countries today to support IDA’s advocacy e orts, access special events, screenings, workshops, discounts Documentary magazine subscription,

| On July 1, 2025, we introduced a new scaled Doc Maker membership level that accounts for ent parts of the world, ensuring rs everywhere can access our resources

DOCUMENTARY MAGAZINE

(ISSN # 1559-1034) is the publication of the International Documentary Association, a nonprofit organization established in 1982 to promote nonfiction film and video and to support the efforts of documentary makers around the world.

Magazine Staff

Abby Sun / Editor

Marlene Head / Copy Editor

Maria Hinds / Art Direction & Design

Janki Patel / Advertising Manager

Zaferhan Yumru / Production Manager

magazine@documentary.org

Dominic Asmall Willsdon / Publisher L.A. Publishing / Printer

3600 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1810

Los Angeles, CA 90010

TEL: + 1 (213) 232-1660

FAX: + 1 (213) 232-1669

info@documentary.org documentary.org

IDA Staff

Colin Arp / Office & Administrative Coordinator

Catalina Combs / Marketing & Communications Manager

Melissa D’Lando / Grants Manager

Mary Garbesi / Director of Finance & Administration

Grace Gordon / Publication Intern

Anisa Hosseinezhad / Membership & Individual Giving Program Manager

Katy Hurley / Funds Coordinator

Janki Patel / Advertising & Sponsorship Manager

Gabriella Ortega Ricketts / Communication & Events Manager

Maria Santos / Artist Support Manager

Lilla Sparks / Fiscal Sponsorship Program Coordinator

Abby Sun / Director of Programs

Bethany Weardon / Fiscal Sponsorship Program Manager

Dominic Asmall Willsdon / Executive Director

Zaferhan Yumru / Director of Marketing, Communications & Events

Armando Zamudio / Events & Content Program Officer

IDA Board

Ina Fichman / Co-President

Michael A. Turner / Co-President

Chris Albert / Secretary

Maria Agui Carter / Treasurer

Bob Berney

Paula Ossandón Cabrera

Inti Cordera

Toni Kamau

Grace Lee

Orwa Nyrabia

Chris L. Perez

Alfred Clinton Perry

Nathalie Seaver

Amir Shahkhalili

Joel Simon

Luis González Zaffaroni

David Osit discusses how Predators stealthily reflects both true crime and documentary commodification of human suffering Abby Sun

Mstyslav Chernov transforms war reporting into immersive cinema in 2000 Meters to Andriivka

Sonya Vseliubska

Brent and Craig Renaud risked their lives to make vérité documentary journalism—after Brent’s death, Craig honored his life with a new film

Lauren Wissot

Heaven Meets Earth

Petra Costa’s new documentary Apocalypse in the Tropics explores the “fatal marriage” between Christian nationalism and authoritarian politics

Bernardo Ruiz

Price of Recognition

Two award-winning incarcerated filmmakers discovered that their success at the first San Quentin Film Festival came with strings attached, when the nonprofit that provided their equipment demanded they sign away all ownership rights

Steve Brooks

Amid the festival’s commercial wrappings, three docs from rising filmmakers plumb the depths of American inequity

Natalia Keogan

Philadelphia’s beloved festival for Black, Brown, and Indigenous filmmakers explores themes of inheritance and artistic lineage

Tayler Montague

Producer’s Diary: In Waves and War

Robin Berghaus

Screen Time: Checkpoint Zoo

2+2=5 Paris Calligrammes Riefenstahl

Dear Readers,

The risks documented in this issue’s thematic strand of “Dangerous Territory”—physical danger, political pressure, institutional exploitation—are not aberrations of our current moment. They have persisted since the earliest days of documentary practice. When the Lumière company sent camera operators to French colonies to record travelogues, they worked in a world with an established visual economy of organized conflict, from war photography to muckraking. Robert Flaherty risked hypothermia to protect his cameras while filming Nanook of the North. Before they made King Kong, Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack trekked hundreds of miles for Grass, and faced a stampeding elephant in Chang Joris Ivens dodged fascist forces to make The Spanish Earth during the Spanish Civil War. In fact, the success of these early documentaries benefited from the danger the filmmakers experienced while making them.

Our editorial line does not attempt to glorify the threats that filmmakers face today; rather, it seeks to explain them. This issue’s cover feature on Petra Costa’s Apocalypse in the Tropics places her in conversation with Bernardo Ruiz, another filmmaker who has also deeply investigated the evolution of an electorate across multiple election cycles. Costa was publicly denounced by Brazil’s then-President Jair Bolsonaro for “slandering” her country. In this interview, she describes why she nonetheless chose to make a film on the religious forces that brought Bolsonaro to power.

The three other articles in the “Dangerous Territory” strand feature other filmmakers under fire. Mstyslav Chernov’s transformation from war reporter to filmmaker is chronicled by Sonya Vseliubska, who is interested in how 2000 Meters to Andriivka employs cutting-edge camera and sound technology. Lauren Wissot’s profile of the Renaud brothers, Brent and Craig, illuminates the price of their vérité approach to conflict journalism, which is also covered in Craig’s recent mid-length film, Armed Only With a Camera: The Life and Death of Brent Renaud Journalist Steve Brooks investigates how even nonprofits designed to nurture mediamaking can become sites of exploitation. Brooks, the former editor-in-chief of the San Quentin News, also details how the appropriation of two incarcerated filmmakers’ creative labor echoes decades of similar struggles inside California’s prisons.

While the methods of censorship, financial exploitation, and violence might differ now, the entanglement between vulnerability and profitability remains. Outside of the thematic strand, I interviewed David Osit on Predators, his slippery exposé of the crime sting journalism of To Catch a Predator, after finding the film to be a compelling, unexpected critique of true crime— and the limits of personal documentaries.

Our recurring segments include two festival dispatches. Natalia Keogan considers independent documentaries amid Tribeca’s rampant commercialization, while Tayler Montague returns to BlackStar, which has become a vital U.S. stop for BIPOC filmmakers. For “Producer’s Diary,” Robin Berghaus gathers the ups and downs of Bonnie Cohen and Jon Shenk’s In Waves and War, a Participant-funded film caught in the middle of the company’s shutdown, from Cohen, Shenk, and producer Jessica Anthony. And “Screen Time” continues with capsule-length reviews on notable new releases.

Until the next issue,

Editor, Documentary

The pieces in this issue on filmmakers under fire continue a conversation this magazine has been having for decades. Many years ago, for example, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, Laura Almo wrote:

Danger comes in many forms. There is the geopolitical danger of a country in the middle of a war, or that has been ravaged by war and is politically destabilized. There is also the sociopolitical danger of filming in a totalitarian state, where subjects address the camera at their own peril—and that of their family and friends. And there is the danger of repercussions to the filmmaker once the film is out in the world. (“Documenting in the Face of Danger,” Documentary, February 2002)

Today, the dangers are as great as ever, and they take many forms. Our field is under attack. Filmmakers face rising censorship, funding cuts, and political threats designed to silence dissent. Through this magazine and our wider communications, IDA will continue to share insights and perspectives on the escalating threats.

More than that, we will defend filmmakers from these threats. As an advocate for documentary practice, IDA is committed to defending the rights and safety of nonfiction filmmakers across the United States and around the world.

IDA has been involved in advocacy work for many years. We have had success with such issues as public records access, fair use, and legal protections for sources. We have worked with longtime partners such as the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and the Knight First Amendment Institute to bring legal actions in the interests of documentarians. But we need to do more. We are doing more.

This month, IDA is announcing a broader, deeper commitment to advocacy. This includes a more powerful and sustained practice of strategic litigation—we are currently exploring options for our third legal action against the Trump administration’s visa rules. We will provide fast and accurate interventions on behalf of filmmakers and film organizations at risk from harmful government and business dealings. We are creating emergency funds and pro bono legal support for filmmakers in danger, and developing education and resources related to legal affairs, safety, and security. And we want to do even more.

We are not alone in this work. There are great organizations advocating for documentarians in other countries. As a field, we need to be globally connected and work with many partners because the issues are shared across borders. Given that many technology and business interests are based in the U.S., it is important that there is a U.S.–based advocacy entity that is globally connected. IDA is positioned to be that.

Other fields of cultural practice have long-standing and effective advocacy organizations: the Authors Guild, the Society of Professional Journalists, the Artistic Freedom Initiative, and many others. Documentary filmmaking has IDA. We who work at IDA and you as IDA members need to make sure we can provide the advocacy that documentary needs and deserves.

We need your help. By being an IDA member, you support this critical work.

Executive Director

By Robin Berghaus

In Waves and War opens with a scene at Stanford University’s Brain Stimulation Lab, where combat veterans tell a research scientist why they’re leaving the U.S. to try a controversial therapy. They’ve endured depression, PTSD, and traumatic brain injuries. After exhausting medical treatments in the U.S. that weren’t effective, some considered suicide.

Marcus Capone had been in their shoes. Feeling desperate, the Navy SEAL veteran traveled to Mexico to undergo a regimen of psychedelic medicines, including 5-MeODMT and ibogaine—the latter is what the veterans in the Stanford study would try. These naturally occurring psychedelics are illegal in the U.S. but have been used abroad for centuries by Indigenous communities.

Capone described in an interview how psychedelic therapy helped him alleviate stress and anxiety. “The medicine cracks you open and gives you a new white canvas to paint whatever you want on there. It changed my life forever,” Capone said. But, he said, it’s a misconception that simply taking a pill makes everything better. The most difficult work, Capone stressed, follows the treatment. “You have to put a plan in place and conduct consistent integration sessions with an experienced coach/therapist to help process your psychedelic experience. Otherwise, you potentially can go back to the way things used to be.”

Capone’s years-long struggle is common among veterans but not often voiced in a military culture that stigmatizes asking for help. Buried trauma and insufficient treatments have fueled an epidemic in which members of the military are more likely to die by suicide than in combat.

So, when Capone finally experienced relief, he and his wife, Amber, founded Veterans Exploring Treatment Solutions (VETS) to help veterans access psychedelic therapy. In Waves and War tells the Capones’ story and that of two Navy SEALs who welcome

cameras to document their psychedelic experiences. They share past traumas and hallucinations, which are illustrated by their personal archives and animation. Psychedelic therapy, they say, gave them hope and a capacity to heal.

When Diane Weyermann met the Capones in 2019, she knew she had found her next project. As Participant Media’s chief content officer, Weyermann cultivated

documentaries to inspire positive change in the world. But she needed the right filmmakers. So she tapped Bonni Cohen and Jon Shenk, founders of Actual Films, who for more than two decades have communicated how trauma, from sexual abuse (Athlete A, 2020) to genocide (Lost Boys of Sudan, 2003), affects the human experience.

Cohen, Shenk, and producer Jessica Anthony opened up about their challenges making In Waves and War, including how, after Weyermann died and Participant Media closed, they pivoted to carry out the impact campaign that Participant had promised. Now they’re building partnerships and events to destigmatize seeking mental health treatments and influence legislation that supports veterans unserved by America’s healthcare system.

Bonni Cohen (Producer/Director): Diane Weyermann brought Marcus and Amber Capone to meet us at our San Francisco office. They described how Marcus’s PTSD and traumatic brain injuries had affected their family. Psychedelic therapy in Mexico was the last stop for Marcus after trying several other interventions. Because many Navy SEALs and their families had suffered similar traumas, the Capones founded VETS. Their nonprofit helps veterans afford psychedelic therapy abroad. But it felt like an injustice. Why should veterans who defended the U.S. have to leave it for medical care? This film, they hoped, would help inform the public about the crisis underway and convince lawmakers to support research on psychedelic medicines that could become FDAapproved treatments for trauma and other mental health conditions.

Jon Shenk (Producer/Director): Participant contracted us to flesh out access and scope in a development deal, including funding for initial shooting.

Cohen: Marcus and Amber opened doors to members of the SEAL community who are taught a code of ethics and to remain private. We were asking the SEALs to share some of their darkest secrets, so they had to trust us. Our relationship with the Capones was our only way in.

Shenk: We interviewed several retired SEALs who helped us understand what they endured during combat deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq. Among them was Greg Hake, whose best friend had died by suicide. Greg also considered suicide

before he tried ibogaine therapy. During his psychedelic journey, Greg recalls telling his deceased friend, “This experience is about you.” But Greg’s friend said, “No brother, it’s you.” Then Greg fell through a green tunnel that, to him, resembled a sequence in the science fiction film Stargate. Eventually, he got spit out in a basement, where, in real life, Greg had experienced abuse. A voice pointed out that the basement was now empty, so he could move on: “See, there’s nothing here anymore. There’s no one here.”

We had an epiphany that this was not just a film about soldiers getting over PTSD but that it would also get into the psychology of who they are and what led them to join the military to become “protectors.” We were stepping into intimate details of their lives that, in some cases, remained hidden even to themselves. We realized we would have to be mindful because these guys were doing deep psychological work. Greg’s story is not in the final movie, but

his vivid memories inspired our process, including an ambitious animation plan.

Spring 2020

Shenk: By the time we submitted the development materials, we had done some shooting. But we paused at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic when the world got turned upside down.

June 2021

Jessica Anthony (Producer): We brought on Marcus and Amber as consulting producers to acknowledge their contributions. They added legitimacy to our work and continued introducing us to film participants and collaborators.

October 2021

Anthony: At the Capones’ house, we met Matty Roberts, a Navy SEAL veteran who was not yet considering psychedelic therapy. It was his first introduction to the film. Building our relationship with Matty would take a while.

Anthony: Marcus and Amber introduced us to Patsy and DJ Shipley after we heard DJ’s story on a podcast. DJ is a Navy SEAL veteran who had been to Mexico for psychedelic therapy. He saw the film as a way to help his community and jumped in. Patsy hesitated.

Anthony: Jon, Bonni, and I flew to Virginia Beach. We had dinner with Patsy and DJ to get to know each other and talk about our film plans.

Cohen: Patsy had a lot to add but wasn’t sure that going public with her story would be the right thing for her family long-term. So we did something we’ve never done. We said, “Why don’t we film this interview, and then you can decide whether you want to sign the release. But at least tell your side because it’s as important as DJ’s.” We knew that any piece of Patsy’s story would be better than none. Both DJ and Patsy let us interview them on that trip.

Cohen: We shared with Patsy her interview transcript. She struck a few lines that she felt were not totally accurate, and agreed to have her story included. We felt that collaboration was important—after all, it’s their life story.

Shenk: We realized that her freedom to speak openly, without that interview being final, allowed her to say things she might never have otherwise.

Anthony: We sat down for our first embargoed interview with Matty. He was still unsure about participating. He didn’t want this to be about him, but rather thought of it as a way to help his military brothers and prevent suicides.

We also began filming with several veterans enrolled in Stanford’s ibogaine research study before they traveled to Mexico for treatments.

Anthony: Blake Mycoskie, founder of TOMS Shoes, came on board as an executive producer. He was drawn to the stories in our film and saw its impact potential. Psychedelics helped Blake process difficult things in his life, and he has pledged to donate millions of dollars to support research into psychedelics as medical treatments as well as other initiatives, including a psychedelic documentary fellowship.

Anthony: We began working with Studio AKA on the animation. We went back and forth with our guys, asking granular details about battles and their psychedelic journeys. At one point, DJ sent videos of himself sketching on a whiteboard to block out a battle sequence, which the animation team referenced for the re-creation. I was constantly texting our guys to verify the right kind of night goggles, the proper aircraft carrier, and the exact visualization and feelings they had when under the influence of ibogaine and the 5-MeO-DMT. It had to be accurate.

Shenk: After Matty’s military brothers gave him their blessing, he began to feel more comfortable, and we filmed Matty going through psychedelic therapy treatment in Mexico. Two weeks later, we did an interview with him. We thought we had what we needed to finish the film.

Shenk: Matty called and said, “I don’t think my story is done.” When we interviewed Matty shortly after his treatment, he was still recovering. But several months later, he began making tremendous breakthroughs, including a better understanding of his survivor’s guilt, childhood trauma, and lack of spiritual belief. He wanted this part of his experience to be documented for people who may not view ibogaine as an option. Because, he said, “I was that guy, too.”

July 2023

Shenk: So we filmed with Matty and his therapist. I just love that scene. It became the ending of the film. Matty was right!

January 2024

Anthony: Stanford’s research findings were published in Nature Medicine, a highly selective scientific journal. Most veterans in the study, and some we filmed with, said that a single ibogaine therapy treatment significantly improved their mental and physical health.

February 2024

Anthony: One of our executive producers, Geralyn Dreyfous, introduced us to Peter Palandjian and Eliza Dushku Palandjian, who joined our team of executive producers to support the production and impact campaign. They are very

involved in Boston’s mental health space, funding and advocating for psychedelic therapy research. Eliza herself underwent psychedelic therapy to help process and overcome PTSD.

April 2024

Shenk: Participant announced publicly that it would close, which seemed out of the blue. I think it took the employees at Participant by as much surprise as it did us.

Cohen: Participant financed the bulk of the production budget, along with funders brought in by Actual Films and Chicago Media Project. But Participant would no longer be producing the impact campaign. So, we took it upon ourselves to raise additional funds and build an impact team to do this work.

June 2024

Anthony: We completed the sound mix and color to finish the film.

July 2024

Anthony: Amber and Marcus introduced us to Waco Hoover, a Marine Corps veteran, who has advised our impact strategy. Waco chairs the American Legion’s “Be the One” campaign, which is focused on ending veteran suicide.

Cohen: Participant, which still exists as a business entity, chose Josh Braun at Submarine as the sales agent and made all the business decisions around how the film would go out into the world.

August 2024

Shenk: We premiered In Waves and War at Telluride. Several distributors saw it there, which got the conversation started. But we didn’t walk away with a sales offer that weekend. It has been twisty-turny with the distribution world imploding on us. We’re living in a period where business decisions seem to be taking precedence over art or social issues.

January 2025

Anthony: Netflix approached us to offer a hybrid licensing deal as part of an effort to acquire six documentaries that performed well at festivals.

February 2025

Anthony: We collaborated with the Capones’ nonprofit VETS to organize an In Waves and War screening for Texas lawmakers who would vote on a US$50 million bill to help bring ibogaine through clinical trials. Sherri Reuland, a Texas Ibogaine Initiative consultant, saw our film and wanted to use it to push the conversation forward. Her organization paid for the reception and our team’s travel expenses. That synergy was possible because everyone was after the same thing.

March 2025

Anthony: Amber, Marcus, Matty, Nolan Williams (who led the Stanford study), Jon, and I attended an In Waves and War screening with Texas lawmakers.

April 2025

Anthony: The Palandjians hosted a screening in Boston that raised over US$900,000 for Home Base, a nonprofit that provides healthcare for veterans at no cost.

May 2025

Anthony: Two months after our screening, the Texas Senate and House of Representatives voted to pass the ibogaine bill.

We hired Jamie Shor, president of PR Collaborative, to garner press around the issues of our impact campaign.

June 2025

Cohen: The Netflix deal was announced. In Waves and War will begin streaming in November. We are grateful, because the

bottom line is that we hope our films get to be seen by the biggest audience possible.

Anthony: For more audience building, we screened In Waves and War at Psychedelic Science, a conference that attracts thousands of researchers and advocates in the psychedelic space.

Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed the US$50 million ibogaine bill into law, which, according to advocates, is the largest state-funded psychedelic research initiative in history.

With philanthropic donations from about a half dozen individuals, we hired impact producer Chris Albert [current board secretary of IDA, which publishes Documentary Magazine] of Albert Media Group to build out an ambitious plan. Chris will remain on through the wide release.

July 2025

Anthony: We are planning educational screenings centered around World Mental

Health Day and Veterans Day. We are also collaborating with the American Legion and other veterans service organizations that will encourage their constituents to turn out.

We are organizing an educational screening on Capitol Hill in October before our Netflix release. Members from both parties—including Rep. Dan Crenshaw (TX) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (NY)—have been uniting around these issues, so we feel it’s the right time.

We’re also planning educational screenings at state capitols, including in California, North Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia, where lawmakers are considering legislation that would help fund and advance psychedelic therapy research leading to FDA approval. The Capones and VETS are helping us identify legislators who are interested in the topic, including members of the Armed Services and Veterans’ Affairs committees. We’ll

ask these lawmakers if they would co-host screenings and if insiders could spearhead the events.

It used to be that we would finish a film and get on to making the next one. But it’s hard to replace yourself when you’ve been the constant inside this journey and care deeply about both the subject and the participants who put so much on the line..

Sun is IDA’s director of programs and the editor of Documentary

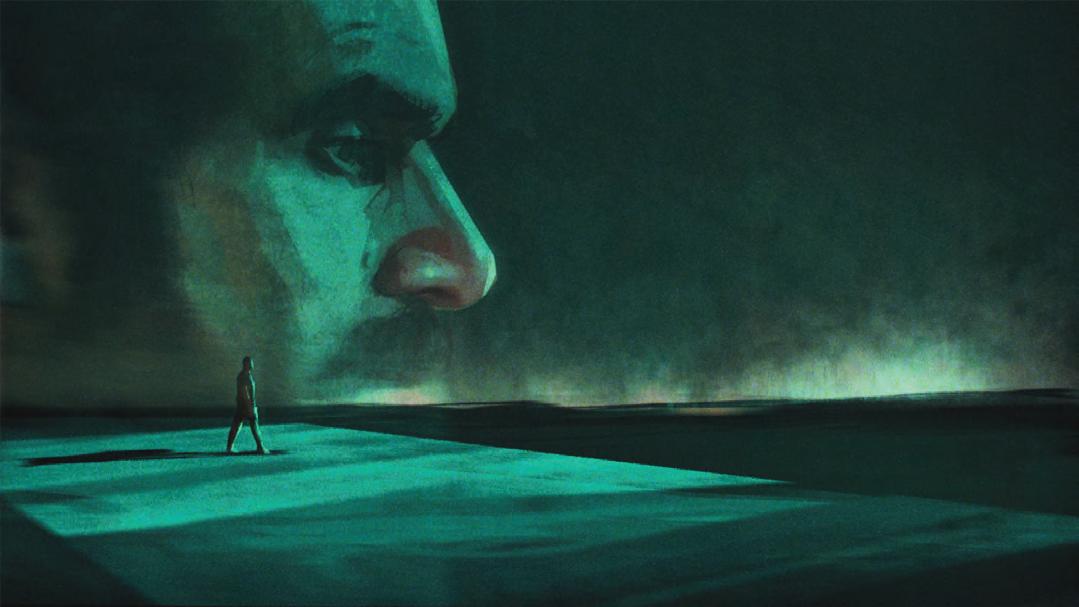

David

Osit discusses how

Predators stealthily reflects both true crime and documentary commodification

By Abby Sun

David Osit has built his filmography by asking uncomfortable questions about the stories we tell ourselves about progress. As a director-cinematographer-editor, Osit has consistently turned his lens toward subjects that resist easy moral categorization. His 2020 feature Mayor followed Musa Hadid, the Christian mayor of Ramallah, as he navigated the absurdities of governing under Israeli occupation—a film that found dark comedy in bureaucratic dysfunction while highlighting the human cost of political subjugation. Earlier, in Thank You for Playing (2015, directed, produced, and edited by Osit and Malika Zouhali-Worrall), he chronicled a family’s decision to create a hit indie video game about their dying child, exploring how digital media mediates our most profound experiences of grief.

But Osit’s editing resume also includes work that directly connects his livelihood to the ver y phenomena his newest feature, Predators (2025), critiques. As one of the editors on HBO’s series The Vow (2020), he helped craft one of the streaming era’s most successful cult documentaries, turning the NXIVM scandal into television that attracted millions of viewers hungry for true crime content. His editing work on Hostages (2022, which won IDA’s award for Best Limited Series) further ensconced him within true crime media production, even as that series approached its subject of international kidnapping with more nuance than typical genre entries.

P redators emerges at the intersection of two dominant trends in different sectors of contemporary nonfiction: the explosion of true crime content and the rise of personal documentaries that prioritize the filmmaker’s own story and self-revelation. Here, Osit deliberately commingles the two. One effect is that Predators capably examines his own complicity and that of his peers in the documentary entanglement of exploitation and entertainment. Predators is not the first—this development has been noted by film critics in the rise of “prestige true crime”—but it is a uniquely fine-tuned and insightful example. The film takes as its starting point To Catch a Predator, the Dateline NBC series that ran from 2004 to 2007, hosted by Chris Hansen. The show’s format involved adult decoys posing as minors in online chat rooms to lure potential predators to staged meetings, where Hansen would confront them on

camera before the arrival of local police. The series became a cultural phenomenon in the U.S., spawning countless imitators and expanding the ethical borders of mainstream entertainment.

The film begins by examining Hansen’s journalism and the show’s influence, combining raw footage from To Catch a Predator with polished talking heads of police chiefs, an academic who provides a sociological reading, and two former decoys. Their testimonies reveal the psychological toll of participating in vigilante justice, including the show’s final case, where the suspect died by suicide after being exposed. Next, Predators follows, in observational style, current YouTuber Skeet Hansen (whose legal name is Ken Chambers), who has named himself after Chris Hansen and extended his confrontational style for internet videos. In the final act, Chris Hansen is given a chance to directly respond through a pivotal sit-down interview. Throughout the chapter structure, the documentary’s form fractures. What starts as recognizable reportage evolves into something more experimental and personal.

Central to the film’s compelling appraisal is Osit’s recognition that documentary filmmaking—including his own intimate portraiture and for-hire work—exists on a spectrum with true crime docutainment. Both practices involve pointing cameras at vulnerable people, promise to reveal hidden truths, and depend on the audience’s appetite for watching human struggle.

Predators’ final moments crystallize this central argument about complicity and choice. After examining TruBlu Entertainment’s corporate machinery’s ruthless packaging of Chris Hansen’s current To Catch a Predator spinoff and other true crime content, Predators concludes

by following Chris Hansen as he awkwardly exits the interview’s film stage and walks out the door—exercising the very choice his sting operations denied the men he caught. But the film then cuts back inside the studio to rest on Osit’s own face, surrounded by his film crew, teetering between confession and reckoning. It’s a moment that refuses easy absolution and risks aesthetic posturing.

Acquired by MTV Documentar y Films, Predators receives a limited theatrical release in New York and Los Angeles this month before expanding in October. In the following interview, Osit discusses the ethical challenges of making a film that critiques the medium in which it operates, the metatextual editing that serves his thematic investigation, and his enduring belief in documentary cinema’s power. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: You spend the entire film making an argument that society is a little bit sick for liking the undercover sting shows and true crime documentaries. Into the continuum of Chris Hansen and Skeet Hansen, you also place yourself as a documentary filmmaker. How much are documentary filmmakers aggressors or predators in our pursuit of stories?

DAVID OSIT: I think it’s disingenuous to suggest that documentary filmmakers aren’t part of the primordial ooze of finding stories and sharing them to advance certain ideas or mythologies. I believe that I’m doing good. I think most of us believe that we’re doing good work for a living—that’s true of everyone, really.

There are differences between me and Chris Hansen, Skeet Hansen, Joseph Pulitzer, and the yellow journalists at the turn of the 20th century, and there are similarities. Chris and I both make a living doing what we do. We are both incentivized to make what we do appealing to audiences. We also both feel confident that our opinion is one that we want to share and amplify. It’s not a judgment on other people. It’s just a basic fact of life in the modern media landscape, where you are inside a capitalist fight for eyeballs.

D: In the same way that there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, there’s no ethical production either?

DO: I can’t really see how, if I am producing something in the context of it being bought and sold, that it could be ethical. It doesn’t mean that we can’t be good. We can care about what happens to the people around us, and we can have a code of conduct for how we operate.

There are certain rules that I would never intentionally break. I would never want someone to be harmed by a film that I’ve made. That feels like a line that I wouldn’t want to cross, and it’s one of the reasons why filming with some of the predator hunters in my film made me feel uncomfortable and call into question where I actually stood in terms of my moral ground.

D: During the Skeet Hansen sting, we see you start filming while hidden in the bathroom of a motel room, and you come out when a man is caught and reveal yourself as filming. Later in that same scene, there’s also a second reveal, when one of the producers of Predators, Jamie Gonçalves, also comes out of the bathroom and very gently explains to this man that the two of you are not part of the sting. Jamie presents this man with the choice to sign a release form—to decide to show his face or not, in your film.

DO: This particular moment wouldn’t have been a scene I included if it wasn’t standing in contrast to the people that I was filming, who were also making their own documentary and who weren’t asking for consent. As the film proceeds, it becomes increasingly personal, not just for me but for the human beings involved in these productions. In that moment, I really experienced what young people call cringe, which is that you see yourself through the eyes of somebody else, and you don’t like what you see. I don’t know who that man is; I don’t know his name. As far as I was concerned, in that moment through his eyes, there was no difference between me and Skeet. We were the same. We both had cameras pointed at him, and I felt this need to try to say that there was some sort of difference between us.

D: How did you cast Skeet Hansen? In this popular subgenre of internet crime sting videos, why was Skeet chosen as the representative?

DO: Quite simply, I cast Skeet because he’s the scion of Chris Hansen. He named himself after Chris Hansen, imitates him, and uses the folklore of To Catch a Predator as part of his routine. There are other predator hunters who don’t directly mimic Chris Hansen. But once I started filming with Skeet, I felt like I had gotten what I needed.

D: Another distinction we can draw is between an unscripted show’s host and a first-person perspective in a personal documentary. Near the end of Predators, you disclose your own personal connection to this type of material. Internationally, within the documentary industry right now, there is a lot of focus on making sure filmmakers are proximate to the subject matter, authentic in their voices, and representative of the community being filmed, which correlates to a rise in personal documentaries. This conversation isn’t reflected in general audience concerns. Do you think the personal aspect makes your film stronger, and why did you decide to include it?

DO: I’m not sure how much I want to talk about my personal connection for people to read before they see the film. I feel like it’s important to preserve how people come to that organically in the film.

There’s this explosion of true crime designed to propagate entertainment through nonfiction stories, and that’s really not what I fell in love with when I first got into documentary filmmaking in the early 2000s, at the dawn of the DV revolution. These films get made by anonymous filmmakers for anonymous reasons. There’s no motivating factor behind some of the nonfiction series on the major streaming networks except that they are profitable. We all understand people watch crappy TV; we all accept that.

And then there are documentaries that are designed to use all the catchphrases of “shine a light onto societal ills” and “hold a mirror up to our society.” I’m not trying to say that one is valuable and the other is not. But between the two, one of those types of documentary films is allowed to become personal, and one is actively discouraged from being anything but a commodity. I wanted to make a film that maybe jumped between the two, and to see what that did to an audience. In many ways, this film was trying to make a radical act of messing with your expectations.

I do wish more documentaries came with thought bubbles above them: Why does this exist? Why did the filmmaker want to make this? What’s interesting about it to them?

D: Are you trying to Trojan horse your way into an audience that might actually just want to watch a recap of To Catch a Predator?

DO: After I made Mayor, I got some emails and calls about true crime ideas, and I just wasn’t terribly interested in a lot of these approaches. And then I was like, “Why don’t I make a film about how much true crime bothers me?” That’s where Predators came from.

Ever since I started making P redators, this phrase you just used, “Trojan horse,” has become some sort of magic phrase that every network uses about what kind of true crime entertainment they want to make: “We really want to find a film that can be a Trojan horse and start as one thing and become something else.”

I do wish more documentaries came with thought bubbles above them: Why does this exist? Why did the filmmaker want to make this? What’s interesting about it to them?

I’ve never felt to this degree the way in which our world seems to be informed by how entertained we are. The people that I interact with will get their news from the most entertaining source, not the best source. And I think that the line really started to become blurr y from shows like To Catch a Predator—when entertainment became an outcropping of something that purported to be journalism.

This idea of this film being about how all of us, all filmmakers, audiences, journalists, are all part of this cycle of hurt, whether we want to be or not? I couldn’t go on that journey unless I built the house correctly, and the house had to look right. I don’t think a film can change your mind, but I think it can change something deeper inside of you than your mind.

D: You specifically address how journalism can shift in the structure of Predators. I’m referring to how the edit starts from a very straight broadcast journalism approach and later incorporates more vérité, plus a staged interview with Chris Hansen. You conducted an interesting exercise where you split the film into four parts and gave each to a different editor—Erin Casper, Robert Greene, Charlie Shackleton, and Nicolás Staffolani. It seems that the final film still keeps a lot of this form. What did you learn from this exercise?

DO: I intrinsically understood that the way the film would work is if you, as an audience, could feel like you were on the journey with me. The thing that first compelled me was watching footage from To Catch a Predator and feeling this discord between the edited show, which has a dark comedy and reportage, and the raw footage, which is at times devastating, humanistic, and horrifying all at once. I knew that I couldn’t give you that experience without showing you both. Sometimes, the experience would have to mirror the experience I had watching all this raw footage—the same experience that any editor has when they’re sitting and watching rushes and they’re like, “What am I looking at? I can’t believe this.”

I gave certain chunks of footage to certain editors and didn’t tell them what the others were working on. For example, the first thing that got edited was a big chunk of the middle of the film, which is entirely archival footage, that I gave to Erin Casper. I said, “Make me a 20-minute true crime movie out of this. Cut it as though you would be watching any sort of true crime film.” What I got back was completely different tonally from what the rest of the film would be, but that’s what I liked about it. It helped me access a different rhythm of what the story could look and feel like.

The throughline ended up being me as the director and acting more like a supervising editor, hearing ideas from these four brilliant editors, who are all extraordinarily different from one another in their sensibilities but all with good taste and good passion.

Robert Greene, coming from this vein of films that are really about the construction of a film and the miseen- scène that goes into filmmaking [Procession, 2021; Kate Plays Christine, 2016]; Charlie Shackleton, having simultaneously been embroiled in his own true crime pastiche [Zodiac Killer Project, 2025]; Erin Casper, a brilliant editor [Fire of Love, 2022] who I just knew would be able to have an ability to make a true crime thing, which was the last thing I wanted to try to do on my own; and Nicolás Staffolani, a filmmaker [and editor of Cold Case Hammarskjöld, 2019] based in Copenhagen, who was able to look at the nuances of this show with fresh eyes and not see it as something American, but something truly alien. Having those four voices was vital for me because I couldn’t be on my own for this one.

D: This film is bigger than any of the other films that you’ve directed. You also worked with a team of producers, other cinematographers, and camera assistants on various shoots. What did this increased scale bring to this production?

DO: My next film is back to the way I made Mayor. It’ll be me, and I’m sure I’ll show cuts to a couple of friends down the road again.

Predators has to feel like a true crime movie, or else the illusion won’t work. So I genuinely just felt that I had to cosplay as a true crime film director. I guess that means I need to have a bigger team, have a DP shooting it instead of me, or rent lights.

This idea of this film being about how all of us, all filmmakers, audiences, journalists, are all part of this cycle of hurt, whether we want to be or not? I couldn’t go on that journey unless I built the house correctly, and the house had to look right. I don’t think a film can change your mind, but I think it can change something deeper inside of you than your mind.

D: Your film addresses why shows like To Catch a Predator are bad at helping viewers think differently. But for the really, really hard questions, documentaries are also bad at addressing the why. They don’t quite seem to be living up to the current moment. There are more documentaries being made than ever, and suffering persists. What exactly is the utility of the feature-length documentary form to you?

DO: Imagine if you swapped out the word documentary for the word art. What is the utility of art? What I mean is, what’s the utility of asking questions of the world we live in, of deciding that we’re not necessarily happy with how we treat each other, or questioning the idea that there’s not one moral stance about what is good and evil or right and wrong?

This film came from a place of deep disaffection with what the commodification of media has done. But it also comes from feeling a deep sadness at our society’s inability to find empathy for people and its desire to shun those who try to. Nothing is more indefensible than being a child predator. It’s not about whether we care about what happens to these people. How do we live in a society that can find a way to make someone into an evil entity? We’re doing that on massive scales all the time. There’s a genocide happening. We’re in a situation where all it takes is the side with power to be able to construct an identity of the people being killed and say that it’s justified.

I have to believe that we would be a better society if we saw people with nuance, and I think our media would be better if it did the same. I want to make more films that do that. The utility is that I’m just trying to make the world I believe in..

These documentary filmmakers work in conditions where the act of bearing witness carries profound personal risk—from Mstyslav Chernov’s frontline transformation to Brent Renaud’s death in Ukraine to Petra Costa facing threats for documenting Brazilian authoritarianism. In California’s San Quentin prison, the power to document becomes contested terrain where institutional forces seek to control or exploit the stories being told. The four pieces in this section examine how documentarians navigate physical danger, political pressure, and systemic exploitation while maintaining their commitment to truth-telling, and how these extreme conditions are reshaping documentary practice itself.

Sonya Vseliubska is a Ukrainian film journalist and scholar based in the UK. She is a staff writer for Ukrainska Pravda , the country’s leading online newspaper. Her writings on film have also been featured in Modern Times Review, e-flux, Filmmaker Magazine, and Talking Shorts, among others. Her academic focus lies in Ukrainian war documentaries.

By Sonya Vseliubska

Mstyslav Chernov always dreamed of becoming a filmmaker—but its realization came through time and tragedy. After he had spent years in fine art and documentary photography, the 2013–14 Revolution of Dignity redirected Chernov’s focus to conflict reporting, leading him to work as a freelance multiformat journalist for the Associated Press. In 2014, on just the third day of his assignment, Chernov captured the first images of the Russia-downed Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17. Over the next eight years, he worked across continents documenting wars, genocides, political and migration crises, and epidemics— narrowly surviving, even when, in Mosul, a sniper’s bullet pierced his camera and lodged in his gear. But as he would later say in interviews, nothing was comparable to the siege of Mariupol.

In 2022, as Russian forces targeted residential neighborhoods with airstrikes and used starvation as a weapon, Chernov remained in Mariupol with AP colleagues Evgeniy Maloletka and Vasilisa Stepanenko filming the living and the dead. Their work not only became the sole professionally documented visual record of Russian war crimes in the city but also brought Chernov international prominence and ultimate recognition with a Pulitzer Prize.

This footage also gave him the bitter opportunity to tr y filmmaking. The film that resulted from cutting together their onthe-ground reporting, 20 Days in Mariupol, premiered at Sundance in 2023. Basing the film on the most dramatic excerpts from the news, Chernov structures it as a 20-day diary, overwhelmed with footage of children’s deaths, makeshift graves, hunger, and shelling—all intensified by dramatic music and his lyrical reflections, both as a war reporter and as a Ukrainian. Its mission was to evoke deep empathy and force attention on Ukraine, which it did with exceptional success, crystalized by copious festival screenings and a number of awards, and eventually bringing the first Oscar for Ukraine. Yet there was a price for

The film is a triumph of digital-age documentary—a convergence of full-scale warfare and the full force of contemporary audiovisual technology, echoing the evolution of the tools used in modern war.

that attention. The film’s deliberate crossing of conventional boundaries in its depiction of human suffering and intentional blurring between journalism and documentary raised concerns among Ukrainian documentarians and some emotional fatigue among the international audience.

If one assumes Chernov simply found himself with unique footage in the right place at the right time—using documentar y as a convenient political vehicle, his new film, 2000 Meters to Andriivka, proves otherwise. When Chernov accepted his Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, he was already developing this new project, which was made with different methods and, unlike 20 Days in Mariupol, was conceived as a film from the very beginning.

Chernov’s second feature covers Ukraine’s 2023 summer counteroffensive, following a platoon whose mission is to cross a heavily fortified forest and liberate a strategic village. The protagonists are Ukrainian soldiers, whose perspective Chernov centers as the viewer is plunged into the trenches. The film is divided into chapters with titles that count down, by hundreds of meters, the soldiers’ advancement toward Andriivka. Using multiple types of cameras and perspectives, a haunting score composed from the sonic debris of war, and a seamless montage that fuses multiple temporalities, Chernov constructs a highly immersive and unsettling cinematic excursion into the harrowing spatial dimension of war in the heart of Europe.

The film is a triumph of digital-age documentary—a convergence of full-scale warfare and the full force of contemporary audiovisual technology, echoing the evolution

of the tools used in modern war. It also marks the transformation of a war reporter into a film director, whose talent and vision had long awaited their moment. Documentary spoke to Mstyslav Chernov about the incredible craft and personal importance of 2000 Meters to Andriivka. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: You started making 2000 Meters to Andriivka in the summer of 2023, when 20 Days in Mariupol was screening at many festivals and you were giving an enormous number of interviews and panels, followed by an Oscar campaign. Can you guide me through the timeline and how you managed to focus separately on the life of one film and the creation of another?

MSTYSLAV CHERNOV: The trajectory between these two films was strange, sometimes even absurd, as I existed simultaneously in two different worlds: the world of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the world of elegant venues where we premiered and screened 20 Days in Mariupol. The collision of these two worlds brought me to the necessity to make 2000 Meters to Andriivka. In the summer of 2023, people in the U.S. and Europe were discussing the Ukrainian counteroffensive—its scale, the kilometers gained, the names of cities, and the number of casualties Ukraine reported sustaining—but it was all so abstract and detached. I felt almost angry talking to them, as I couldn’t adequately explain how real the situation was. In those days, I would fly from the U.S. back to Poland, and from Poland drive to Kyiv. From Kyiv, I would take a train to Donbas, then a car to the frontline. All of this would happen within 24 hours. So you practically travel back to the other side of the

planet, almost 100 years back in time. Visually, it felt like the First World War, and the soldiers’ experience also felt like that. Sometimes it felt like another planet.

I decided to focus my next film on the experience of soldiers. 20 Days in Mariupol was a film about the destruction of Mariupol and the impact of war on the civilian population. 2000 Meters to Andriivka is a film about the experience of those civilians who took up arms to protect my homeland. But it is very personal too, as Andriivka is a two-hour drive from my hometown, Kharkiv. Those fields and forests are also where my grandfather fought during the Second World War. It’s located near Bakhmut. Kharkiv Region and Donbas are places where my parents and I used to visit my grandmothers. So there’s a very personal connection to this native land, which has now been mutilated by bombs. It’s no wonder the film is about distance—not only the meters soldiers have to walk in the film, but also my own attempt to shorten the distance between the West and Ukraine.

D: You entered Andriivka fully aware of your role as a director—and that shift is palpable in the stark contrast of methods between your two films. In 20 Days in Mariupol, you demanded an overwhelming emotional response from the viewer, and it was hard to watch. In 2000 Meters to Andriivka, the subject matter remains just as harrowing, yet I found it more watchable—not because it’s any less urgent, but because you skillfully employ cinematic language to create an almost hypnotic effect. How did you develop the specific form of storytelling and the clear mediation with the viewer?

MC: Indeed, 20 Days in Mariupol began as a series of news dispatches that later became a film. This worked well because one of the themes of this film is journalism and its impact—or sometimes lack of it. In the case of 2000 Meters to Andriivka, it was conceived as a film and shot with filmmaking in mind, so it possesses a more cinematic quality.

If we are working with the medium of cinema, and we are aiming to show the film in theaters and targeting a wide audience, which is a very natural goal for a film director, it is

essential to make sure that people will not turn away. Fortunately, reality provided us with a clear dramatic structure, almost like in scripted cinema: there are protagonists who have a clear goal and there is time pressure and life danger. We just had to make sure that those elements are preserved. Our main goal was to engage the audience, to bring them into the trenches, to let them walk with the soldiers and with me, and to not let them go.

D: I’d like to unpack this immersive quality further by focusing on the use of video formats. Can you tell me how many types of cameras or recording devices you used in the film, and how you worked with that variety of footage during editing?

MC: The war is changing, weaponry is developing, and the tools available to documentary filmmakers attempting to adequately portray war are also expanding. Today, we can realistically portray the actual experience of the soldier on the front line. In the past, the way to portray the experience of a soldier going through, let’s say, the Battle of Verdun in the First World War, was through the paintings of Paul Nash or the writings of Remarque. But now we have tools that are pushing the boundaries of documentary cinema. But you can’t just drop the audience into the chaos of the battle, so we build up to it.

Together with Michelle Mizner, brilliant editor and producer, who has worked with me since 20 Days in Mariupol, we start the film from a very simple, single perspective, and as we go further, we add more and more cameras. By doing so, we are acclimating the audience to multiperception scenes. You can see that the third of “1,000 meters” has two different perspectives—we add the drone footage. The battle of “600 meters” has six different cameras. Two of them are on the battlefield: a bodycam and a 360-degree camera, allowing you to reframe the perspective of the shot in post. There are also two drones, one of which is a suicide drone; two cameras at the headquarters; and a camera on the injured arriving at the hospital. That’s actually seven cameras.

Drones, infrared, Sony mirrorless, 360 bodycam, GoPro, the occasional smartphone—all of these are in different formats and of different quality, but if introduced gradually, by the middle of the film the audience forgets there is a big visual difference between them.

D: Those camera qualities, combined with an almost fictional dramatic arc, bring us into the territory of the film theory term war spectacle. It can create the sense that we’re spectating a sort of video game. In addition, the use of inhuman, mechanical camera gazes risks dehumanizing the material. You seem aware of that risk and include personal perspectives of the soldiers and yourself. How did you practically deal with the risks of dehumanization and derealization during editing—and were there any ethical boundaries you set in postproduction?

MC: We searched for that thin line of engaging the audience while remaining respectful of all the pain. That’s why the film took so long to edit. War may seem thrilling, but it is a tragedy that should not be romanticized or made to look beautiful. The biggest crime a documentary filmmaker or war reporter can probably commit is to make the audience walk out of the cinema and say, “Ah, that was a beautiful film.” For me, that means they didn’t do a good job.

In that sense, the most difficult parts were, surprisingly, the bodycam footage scenes and its combination with GoPro footage. Initially, we thought that it would be the easiest part for the audience to connect with because you are literally “in the boots” of the soldiers, seeing the world through their eyes. But during the editing, we figured that was not the case. We struggled to find the right length and pace for those scenes. When they were too long, the audience became disengaged and bored. When we cut them too quickly, the audience detached from the experience and felt like they were watching a computer game.

The placement of the scenes within the film was very dependent on that feeling of detachment or attachment to the protagonist. The problem with bodycam footage is that you rarely see faces. There isn’t much talk on the

battlefield. We knew that if we don’t show the faces through whose eyes we later see the battle, the audience will not connect to them. That’s a problem. Especially for audiences who, unlike Ukrainians, have no stakes in this war. Add the fact that, to the untrained eye, soldiers in uniforms all kind of look the same.

The solution was to find those conversations that would reflect normal civilian life, something that is natural for us as humans to talk about, rather than big ideas or patriotic views. When you do that, then the rest of the film becomes more relatable, human. The audience sees a civilian who’s thinking about his cigarettes, about fixing the toilet at home, or the university that he has enrolled in and couldn’t finish because of the war. Small things to the world, but huge to us, and then everything else around just falls into the right place.

D: The music in the film clearly supports the audiovisual, never allowing the viewer to relax, since any kind of synchrony or catharsis only happens at the end. How did you work on the audio layer of the film in relation to the editing process?

MC: The original score was written by Sam Slater, an amazing composer, who is now a good friend. One of the first questions Sam asked me was, “What is the genre of this film?” I explained that for me, 20 Days in Mariupol is a horror film, so we searched for a composer who specializes in horror films, and Jordan Dykstra did amazing

work on it. In 2000 Meters to Andriivka’s case, I was searching for someone who could create an action thriller, but a highly realistic one. A music that would correspond to the auditory experience of being on the battlefield.

I love Sam’s work on Chernobyl (2019) and how he created music from the sounds of a nuclear reactor. I wanted 2000 Meters to Andriivka to have music that reflects what the war feels and sounds like. You don’t hear an orchestra on a battlefield. You hear the whizz of bullets, explosions, the buzzing of drones, and the radio crackling. We decided to incorporate all of those sounds into the score. Sam used the sounds of the battlefield as musical instruments; machine gun bursts became drum sequences, distorted radio transmissions replaced strings. For a while, Sam was looking for a signature sound that appears at the title card and then repeats throughout the film. He and Jakob Vasak, music producer of the film, created an entirely new musical instrument, the Kobophone [a DIY

feedback module that amplifies the percussive elements of the score and distorts sounds, turning them into chaotic growls].

Lastly, to preser ve a feeling of “rawness” of the material, I decided not to use a sound designer on this film. Everything you hear is recorded by the cameras on the battlefield, which means the music takes on the weight of creating the sound landscape of this reality.

D: Speaking broadly about the whole experience of the post and production process—can you now trace your transformation from war reporter to film director?

MC: Before becoming a journalist, I always wanted to be a film director. Journalism felt like the right path when the Revolution of Dignity and then Russian invasion in Ukraine began. But my experience in Mariupol marked a turning point. It was just the right moment

to transition from journalism to filmmaking. It wasn’t just about fulfilling a long-held dream; I feel that films in general are more impactful nowadays. Political, emotional, historical impact and the way we preserve memory. Journalism was attacked and keeps being discredited, and I see that people don’t trust facts anymore. But I see that people are still able to emotionally connect to the films. I guess that’s the medium I want to work with, and this is what I will continue to do.

D: I wanted to touch on the political comment you personally convey via voiceover about the exhaustion and even hopelessness of this war. Back in 2023, that would have been called pessimistic, but now I would rather call it realistic. How did this rhetoric build up, and does the condition on the frontline shape it?

MC: I believe this is a natural progression of what I felt about war and humans at war even before 20 Days. I have been through six wars—Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Gaza, NagornoKarabakh, and Ukraine—and I hate war with every fiber of my being. Yet I find it important to talk about it, though I have no illusions about what we can or cannot achieve with a camera. The only thing we can do is ensure that reality is recorded and reflected back to people. And this is not just a personal work but also the work of a collective. All the Ukrainian film directors we see this year at festivals are now engaged in this collective effort of preserving the country’s struggle and the transformation its society is undergoing. Everyone is bringing their brick to build this building.

Personally, I do not find 2000 Meters to Andriivka pessimistic; it reflects my dark view of the nature of war I experienced. I tried to balance my personal view of war with the very

different, much more hopeful and stronger vision of Ukrainian soldiers fighting on the front line. Fortunately, they don’t see war as I see it. And if they did, there would be no Ukraine. Even though we know this is a war for our survival and Ukrainian soldiers are heroes, when we show war to the world, we have to walk on thin ice and maintain that balance between glorifying the war and honoring the experiences of Ukrainian soldiers.

D: And if we talk about the realistic state of the contemporary Ukrainian documentary and its collective work, as you describe it, what, in your opinion, is its strength today, and what challenges is it time for it to face?

MC: Fortunately or not—the discussion about the direction of Ukrainian cinema falls on academics and critics. But I think the world’s best art wasn’t created by attempting to be part of a movement, but rather by navigating in the dark, trying to figure out the way to express what artists lived through. Ukrainian cinema is now facing a difficult time for many reasons. Many filmmakers and members of their teams went to fight the invasion. Some were killed. Some left the country.

Another reason is our conscious rejection of the Soviet Union’s legacy. No cultural movement, especially cinema that so heavily relies on tradition, can exist in a vacuum. It exists as a flow. I feel that most of the Ukrainian documentary and fiction filmmakers are rejecting the Soviet Union’s legacy. We found ourselves in this strange position of starting everything from scratch. The demand is high, resources are available. However, we still need to develop our unique language. How do we speak about war? How do we speak about the transformation of society? Our traumas? And also, how do we speak about topics unrelated to war? How do we talk about love, friendship, identity, beauty? There are so many important things besides our fight for survival. And we need to learn how to talk about them when this war is finally over..

Lauren Wissot is a film critic and journalist, filmmaker and programmer, and a contributing editor at both Filmmaker magazine and Documentary magazine. She also writes regularly for Modern Times Review and has served as the director of programming at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival and the Santa Fe Independent Film Festival.

By Lauren Wissot

Sacrificing one’s life for a higher cause is not a lone pursuit. Heroes are shaped and buoyed by supportive families who share the risks—emotionally if not always physically—alongside their loved ones. It’s a painful truth that resonates throughout Armed Only With a Camera: The Life and Death of Brent Renaud, a brutal and beautiful 37-minute tribute from Craig Renaud to his elder sibling and lifelong filmmaking partner, who was gunned down by Russian soldiers at the start of the fullscale invasion of Ukraine.

The film itself embodies the vérité principles the brothers championed throughout their career. Built from footage from the veteran filmmakers’ standouts, such as 2005’s 10-part Discovery series Off to War, it’s also heavily reliant on outtakes from projects like the Chicago-set 2015 Last Chance High and their reporting trips from Central America and Haiti. Due to their vérité commitment, outtakes were often the only way Craig could locate moments with Brent’s voice.

Unsurprisingly, Armed Only With a Camera unfolds without narration or much explanatory text, letting Brent’s work and words speak for themselves. The HBO documentary opens with Brent’s footage from their Central America reporting, as they followed desperate young migrants crossing the river from Guatemala into Mexico, alternating seamlessly between scenes captured by Craig’s lens and Brent’s GoPro. From there it’s on to Honduras, where Brent has a probing conversation with a backpackcarrying teenager, parentless and on his own since the age of 10, who’s fleeing north with the dream of starting “a new family.” As the boy leaves to scale a barbed-wire fence, Brent calls to him, “Be careful. We hope to see you again.”

Cut to a title card reading “Seven years later.” We’re now thrust shaky cam–headlong into “Ukraine 2022,” the sounds of bombs, barking dogs, and air raid sirens portending the tragedy to come. And yet, beyond such

heart-pounding moments, the film is likewise a treasure trove of intimate glimpses, photos, Super 8 movies of their shared boyhood in the South, and Brent’s touching Nieman Fellowship speech, in which he speaks candidly about his autism. What becomes clear is that the Renauds’ collaboration is an intertwining of the personal and the professional, a partnership in which the two siblings became one, which makes the film’s most devastating sequence all the more heart-wrenching. Bravely, Craig has chosen to actually show Brent’s final moments through the lens of his brother’s own camera (which included speaking gently with shell-shocked civilians as they sifted through the rubble of their homes), followed by the aftermath: Brent’s body covered by a blue tarp on a Ukrainian street. Juan Arredondo, an American photojournalist, was also gravely injured during the same attack.

As Craig explained on a panel at SXSW 2025, where the film premiered, “it’s important to show what violence and war do to people. […] Why should it be any different for journalists?” He also discussed how the documentary traces Brent’s evolution from a quiet sociology graduate student to a fearless chronicler of human suffering. Their mother Georgann, a mental health professional, revealed how Brent’s autism allowed him to remain calm in war zones while finding Brooklyn dinner parties absolutely terrifying.

The spot- on title comes from DCTV co-founder Jon Alpert’s eulogy for Brent at his funeral (attended by family, friends, dogs, and documentary participants), which appears in the film along with footage of Alpert and Brent in Afghanistan for 2002’s Afghanistan: From Ground Zero to Ground Zero. Alpert, no stranger to losing beloved colleagues in the field, also served as the film’s hands-on EP—watching every cut through to final assembly, and helping Craig to “stay on message,” as the grieving sibling puts it. It was necessary to strike the right balance between the brothers’ work together as a team, and Craig’s journey to bring Brent home and continue on alone.

Even so, the documentar y expands beyond personal tribute into a meditation on all conflict zone journalists and victims of war; it becomes both a mirror of the brothers’ working methodology and a final collaboration between them, one that asks whether vérité work can survive in an era of increasingly dangerous and underfunded documentary work. Armed Only With a Camera airs on October 21, 2025. It’s a powerful end to the Renaud brothers’ award-winning oeuvre—recipients of Peabody, duPont-Columbia, and Edward R. Murrow awards—though thankfully for the world, Craig and Brent’s ripple effect carries on.

The mission ThaT would define both their careers began decades ago when the Little Rock–raised siblings discovered DCTV in New York, after Brent received his master’s in sociology from Columbia. They were drawn to what Alpert calls “the sort of everyday work” the center was doing within the community—a grassroots approach to storytelling that prioritized access and intimacy over production value and celebrity subjects.

“They struck me as ver y smart, very hardworking, and compassionate in an extraordinary way,” Alpert recalls, when Documentary caught up with him by phone after SXSW. “People could feel their compassion, which enabled them to do things others normally wouldn’t get to do.” This emotional intelligence became the brothers’ secret weapon, allowing them to gain the trust of subjects others couldn’t reach—from meth-addicted families in rural Arkansas to soldiers preparing for deployment in Iraq.

The brothers stood out among other reporters, who would “parachute in and be more concerned about themselves, their own face time, than the people who were really suffering,” Alpert notes. The Renauds’ approach was the opposite. They embedded themselves completely in their subjects’ lives.

Their compassion didn’t eliminate sibling rivalry, however. Alpert recalls the two bickering about who would accompany him to the most dangerous places around the world. While preparing for Afghanistan: From Ground Zero to Ground Zero, Brent “pulled rank” on Craig with the declaration, “I’m the older brother, so I get to go.”

Under Alpert’s mentorship, the brothers learned that true vérité filmmaking required more than just rolling cameras. “It’s not like, ‘add water and you’re a documentary filmmaker,’” Alpert continues. “You have to make lots of mistakes and paint yourself into corners and figure out how to get out of them.” The learning curve was steep, but the brothers proved themselves willing students, absorbing not just technical skills but the ethical framework that would guide their approach to filming people in crisis.

The turning point came with 2005’s Dope Sick Love, the Renauds’ gut-punch feature debut following drug-addicted couples on NYC streets. “That’s a really, really hard film to make,” Alpert stresses. “The main characters were fullthrottle drug addicts in the throes of their addiction. Their lives were filled with their own personal challenges, and that presents challenges when you’re following them.” The film required the brothers to navigate the unpredictable world of severe addiction while maintaining their subjects’ dignity and humanity.

Initially pitched to Alpert, who declined after the emotional toll of his own Life of Crime trilogy (the first two parts were finished in 1989 and 1998), he recommended the untested brothers to HBO’s Sheila Nevins instead. It was a gamble that paid off spectacularly, launching the Renauds’ career and establishing their signature style. As Alpert observes, the film has “no music, no narration, and no cards,” which was unusual for an HBO documentary. “Sheila was forcing us to write books at the beginning of these shows! I told them, ‘Guys, nothing. Nothing except what’s in front of the camera. You’ve got to figure it out.’ And they did. I thought that was amazing.”

This vérité approach defined the brothers’ methodology throughout their career, creating both their greatest successes and their most harrowing experiences. From Off to War—which Craig calls their most challenging project “second to the film about Brent”—to their duPont-Columbia Award–winning Surviving Haiti’s Earthquake: Children (2011) for the New York Times, the brothers consistently chose the most dangerous stories to tell.

Off to War exemplifies their immersive style and showcases the advantages of their Arkansas roots. The project was a nonstop two-year commitment: a full year embedded with the Arkansas National Guard in Iraq, six months of pre-deployment training, and six months documenting soldiers’ reintegration into civilian life. The hometown connection proved crucial for access. Despite the troops having Army-issued talking points for media encounters, “they would turn around and come up to us and talk like we were close friends,” Craig recalls, laughing at the memory.

The series captured not just the obvious drama of combat but the quieter moments that revealed character: soldiers calling home, struggling with equipment, forming bonds that would sustain them through trauma. It was the kind of long-form storytelling that required the subjects to forget the cameras were there, a trust the brothers earned through their consistent presence and genuine concern for the soldiers’ welfare.

Haiti proved even more emotionally and physically demanding. The brothers had been in the countr y covering upcoming elections for the New York Times when the earthquake struck. They were in the Times office putting final touches on a documentary about the country’s “turning a corner,” when the paper’s Dave Rummel, who was then the senior producer of news and documentary, asked them to return immediately for a vastly different story. This juxtaposition—from hope to catastrophe—would become emblematic of their career.

Craig found himself crossing the Dominican border into Haiti within 24 hours after the earthquake, before any

This vérité approach defined the brothers’ methodology throughout their career, creating both their greatest successes and their most harrowing experiences.

Western help had arrived. “There were bodies piled in the streets, and people with open wounds and amputations walking around, having no idea where to go,” he says, his voice still carrying the shock of that initial encounter. Meanwhile, Brent embedded with the Navy hospital ship Comfort, documenting the medical response from a different angle. The brothers’ ability to coordinate coverage while working separately demonstrated their mature partnership and shared editorial vision.

While other journalists focused on death tolls and political implications, the Renauds zeroed in on individual survival stories, specifically on two injured Haitian children who had remarkably lived through the disaster. These young survivors became flesh-and-blood embodiments of the nation’s resilience, their personal struggles illuminating larger truths about human endurance. “We always tried to find stories that took you much deeper,” Craig explains, a philosophy that required an emotional investment that took its toll on the filmmakers.

The Haiti assignment also revealed how the brothers’ compassionate approach sometimes led them into ethically complex territory. When Craig’s fixer asked if they might search for his family first, the line between journalism and

humanitarian aid blurred. These moments—captured in their footage but rarely discussed publicly—demonstrated the impossible choices facing conflict journalists who care deeply about their subjects.

The broThers’ meThodology raises urgent questions about the future of conflict zone vérité journalism in America. Their approach required resources and commitment that seem increasingly impossible in today’s media landscape. Were any other American directors following in their “immersive narrative nonfiction” footsteps, as Craig has always categorized their work?

“I don’t know of anyone who’s done it as consistently and for as long as we were up until the point Brent was killed,” Craig admits, though he notes Sebastian Junger (Restrepo, 2010) had taken a similar approach to conflict journalism.

The scarcity of practitioners reflects the method’s demands. True immersive journalism requires serious time commitment, dramatically increasing both physical risk and financial cost—luxuries few independent filmmakers can afford in an era of shrinking budgets and shortened attention spans. “It only cost us a plane ticket

and our time,” Craig stresses, but that simplicity belies the enormous personal investment required.

What set the Renauds apart was their complete selfsufficiency. “The ability to do everything ourselves” made their approach financially viable, Craig explains. From initial development and field production to postproduction and final edit, the siblings functioned as a two-person crew that never needed to hire additional staff. While this type of small production still exists, it’s become a far less common way of working in commercial documentaries slated for broadcast and cable. Though born of necessity, this efficiency became their competitive advantage, allowing them to stay in the field longer than crews dependent on larger budgets.

“Brent always said the edit is what makes the difference,” Craig highlights as another crucial aspect of their process. While many directors still choose to shoot their own footage, few also handle the complex work of story assembly. The brothers understood that their raw material—often hundreds of hours of footage from months

or years in the field—only gained meaning through careful editorial choices. “We don’t follow a schedule, we follow the story,” was another Brent mantra, according to Arredondo, emphasizing their commitment to organic narrative development.

Their mentor’s influence remained constant throughout their evolution. With Alpert as their guide, the goal was to be “as pure vérité filmmakers as we could possibly be.” This uncompromising technique extended all the way to 2017’s Meth Storm, their final major collaboration, in which the brothers maintained their immersive approach while adapting to new realities. The project found them deeply embedded with two sides of the drug crisis in rural Arkansas—from intergenerational users and dealers to the local DEA agents who knew them all by name. But this time the story was in their “backyard,” allowing Craig to go home at night, given his growing responsibility to his young family and a recognition that the physical and emotional toll of their work had accumulated over two decades.