Director Journal

SMART RULES

Boards brace for AI regulations

Boards brace for AI regulations

ICD courses, developed for directors by directors, provide a personalized and interactive learning journey. Engage in live online instructor-led sessions and connect with a dynamic alumni community for continuous growth and support. For ICD.D designation holders, these courses reinforce your commitment to excellence.

ISSUES OVERSIGHT

BOARD OVERSIGHT OF SOCIAL ISSUES.

CONNECTING SOCIAL ISSUES AND STRATEGY IN THE BOARDROOM

Acquire practical insights and a greater understanding of a board’s role in oversight of social issues.

ONLINE May 30, 2024 APPLY BY: May 9, 2024

ISSUES OVERSIGHT

BOARD OVERSIGHT OF CLIMATE CHANGE.

BUILDING THE BOARD’S CLIMATE COMPETENCY

Effective climate change oversight does not involve a straight path or simple solution. Understand how to frame the risks and opportunities and embed a viable adaptation strategy.

ONLINE May 1, 2024 APPLY BY: April 11, 2024

ICD BOARD FUNDAMENTALS

BOARD OVERSIGHT OF STRATEGY.

OPTIMIZE BOARD ENGAGEMENT IN THE STRATEGIC OVERSIGHT PROCESS

Understand the importance of director engagement in oversight of strategy and asking the right questions throughout the process.

ONLINE May 23, 2024 APPLY BY: May 2, 2024

TO ELEVATE YOUR DIRECTORSHIP IN 2024, VISIT EDUCATION.ICD.CA/CALENDAR24

BOARD FUNDAMENTALS

AUDIT COMMITTEE EFFECTIVENESS.

BEYOND THE TRADITIONAL ROLE OF COMPLIANCE OVERSIGHT

Learn about the intricacies of key relationships, emerging issues and the committee’s role in enterprise risk.

ONLINE April 23, 2024 APPLY BY: April 2, 2024

Not sure which course is the right fit for you? Call 416.593.3349 or email education@icd.ca for a personal consultation.

DIRECTOR EFFECTIVENESS

CROWN DIRECTOR EFFECTIVENESS.

PRACTICAL PRINCIPLES AND STRATEGIES FOR CROWN DIRECTOR EFFECTIVENESS

Discover the unique circumstances and challenges that exist when serving on the board of government-controlled entities.

ONLINE June 18, 2024 APPLY BY: May 28, 2024

Developed with:

ICD BOARD FUNDAMENTALS

ENTERPRISE RISK OVERSIGHT FOR DIRECTORS.

NAVIGATING THE MODERN RISK LANDSCAPE

Acquire a deeper understanding of the board’s role and how to participate in the risk oversight process constructively.

ONLINE April 25, 2024 APPLY BY: April 4, 2024

Developed with:Editorial

EDITOR

Simon Avery

ART DIRECTOR

Lionel Bebbington

CONTRIBUTORS

Hugh Arnold, Richard Blackwell, Jeff Buckstein, Bernd Christmas, Martha Hall

Findlay, Serge Rivest, Barbara Smith, Prasanthi Vasanthakumar, Shirley Won

Prasanthi Vasanthakumar

Rahul Bhardwaj - President and CEO

Richard Piticco - Chief administrative officer

Jan Daly Mollenhauer - Vice-president, sales, marketing and membership

Gigi Dawe - Vice-president, policy and research

Shannon Hunt - Vice-president, education

Kathryn Wakefield - Vice-president, chapter relations

Eric Schneider - President

Abi Slone - Creative director

Dana Francoz - Advertising sales dana.francoz@finallycontent.com 416-726-2853

Building trust and confidence in Canadian organizations is imperative. At the Institute of Corporate Directors (ICD), we believe that this starts with the right leadership and good governance. Directors must lead by being informed, prepared, ethical, connected, courageous and engaged with the world. In the pages that follow, you will find thoughtful and provocative articles that explore these essential leadership qualities. Bâtir la confiance envers les organisations can- adiennes est primordial. À l’Institut des administrateurs de sociétés (IAS), nous croyons que cela commence par un bon leadership et une bonne gouvernance. Les administrateurs doivent gouverner en étant informés, préparés, intègres, connectés, courageux et ouverts sur le monde. Dans les pages qui suivent, vous trouverez des articles réfléchis et provocateurs qui explorent ces qualités de leadership essentielles.

1601 – 250 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario M5B 2L7 T: 416-593-7741 F: 416-593-0636 E: info@icd.ca ISSN 2371-5634 (Print) www.icd.ca ISSN 2371-5650 (Online)

The ICD welcomes a diversity of opinion for inclusion in Director Journal. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the ICD, its partners, its sponsors, or its advertisers. Readers are encouraged to consider seeking professional advice and other views. To request reprints of articles, please contact info@icd.ca

Good regulation works for all of us

Rahul Bhardwaj on leaving our comfort zones behind

Digitized dating, flying high, embracing ESG without the letters, bringing back babies, and walking the AI tightrope

How to avoid a fallout with your CEO

How should boards deal with increased regulation?

Recent board appointments across the country

Female leaders and the ‘glass cliff’

The complex world of artificial intelligence is about to get more complicated

It’s time to reconsider the use of classic governance models for theatre companies

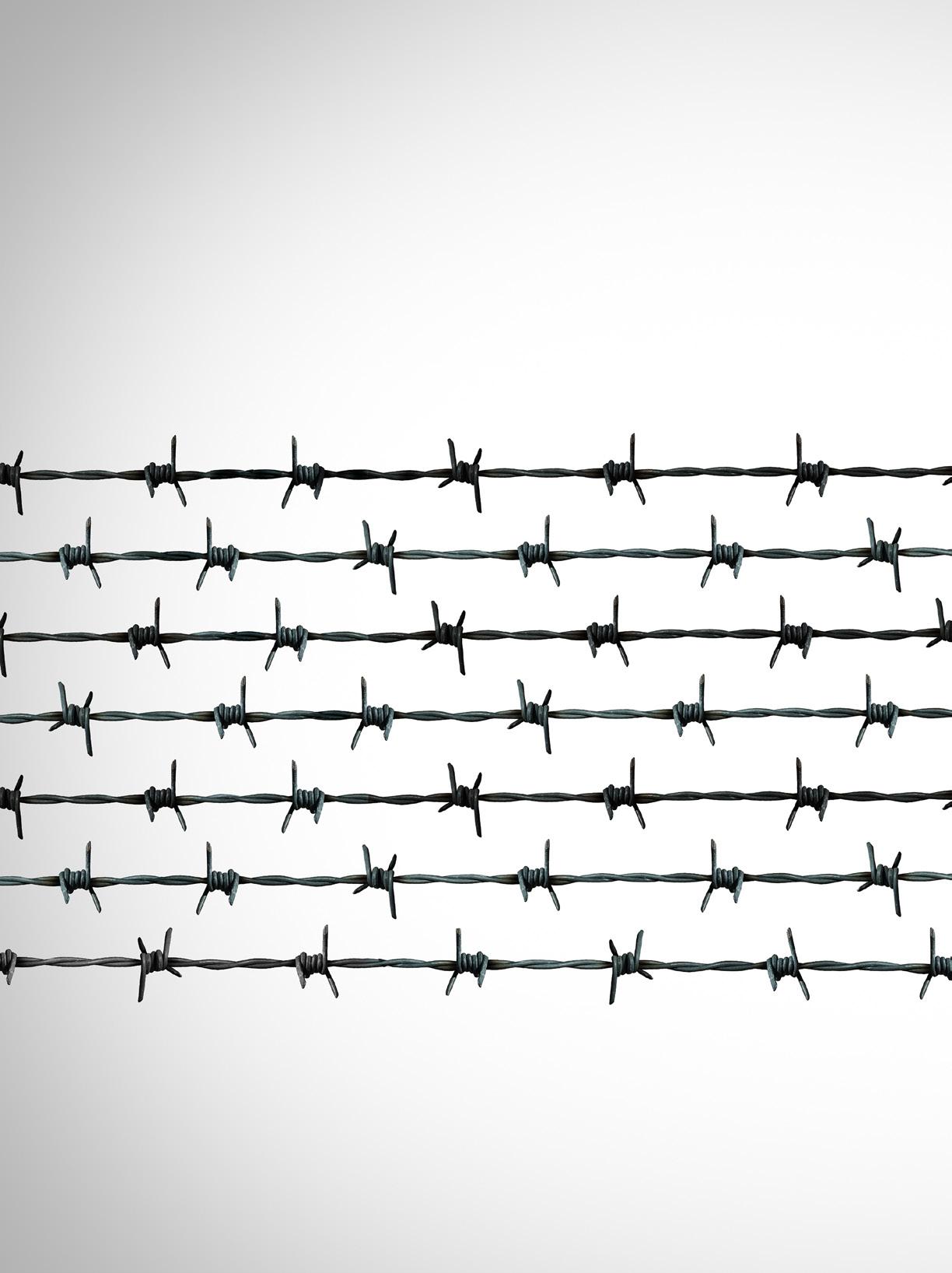

A new law requires businesses in Canada to disclose their efforts to fight modern slavery

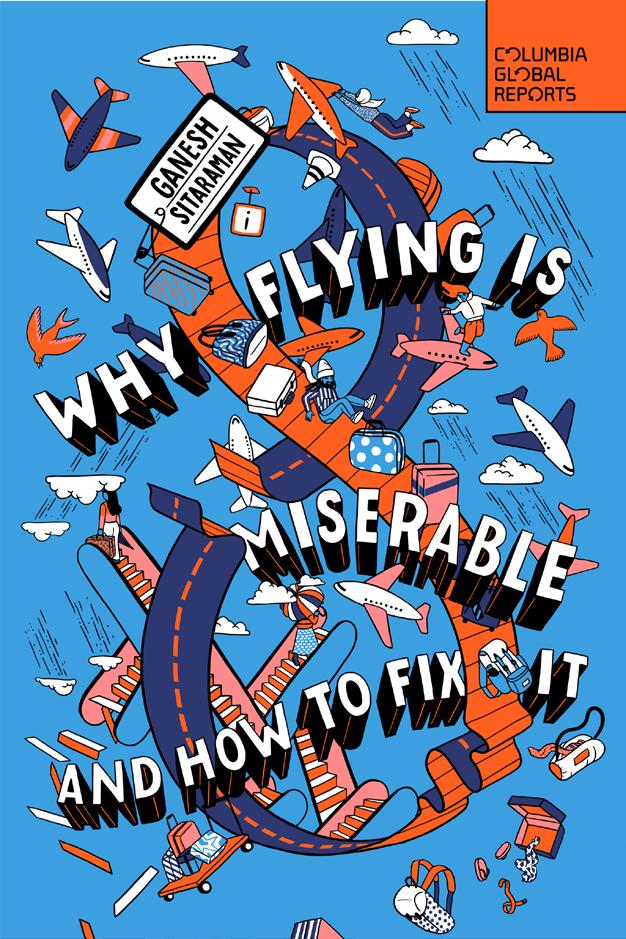

Legal expert Ganesh Sitaraman gets to the root of passengers’ frustrations in Why Flying is Miserable and How to Fix It

16 26 36 46

It may seem that way to busy directors, but new rules aim to cut risks

ASK DIRECTORS about their top challenges right now and they’re likely to name a couple of things: How to integrate new AI technologies safely and effectively, and how to secure reliable supply chains.

As boards wrestle with these issues, regulators, too, have been hard at work. The federal government has introduced new reporting rules and requirements regarding supply chain management and is developing guardrails for what it calls “responsible adoption” of artificial intelligence.

Companies in Canada that meet certain financial thresholds are now required to file an annual report that discloses their policies and processes to cut the risk of forced labour or child labour. In “Crackdown on forced labour” on page 36, Jeff Buckstein outlines what boards need to know about the new legislation.

Simon Avery Editor savery@icd.ca

Simon Avery Editor savery@icd.ca

In his article on AI regulation, Richard Blackwell talks to directors and lawyers about what’s coming down the pipeline and how boards should prepare. “Once this law comes into force, essentially every organization of any size will need to be concerned about compliance,” says Michael Fekete, a partner at Osler Hoskin and Harcourt LLP. On both these matters, the Canadian government has been criticized for failing to keep up with the pace of change.

When it comes to failed government policies, scholars often point to the deregulation of the U.S. airline industry in 1978 as one of the big ones. In his new book Why Flying is Miserable and How to Fix It, Ganesh Sitaraman blames the state of commercial flying today on U.S. deregulation and the consolidation it fostered (see page 46). Other countries, including Canada, followed with their own variations of airline deregulation with questionable long-term benefits.

Canada, however, maintains “a globally respected” regulatory environment on a broad range of issues, ranging from competition to human rights, Martha Hall Findlay says in our Directors’ dilemma (page 12). Findlay, a former oil industry executive and Member of Parliament and now the director of the school of public policy at the University of Calgary, reminds us that as frustrating as government action can be at times, “we all benefit from good regulation.” Efforts to control how generative AI is deployed are about to put that reputation to the test. DJ

DEMANDEZ À DES administrateurs quels sont leurs plus grands défis et ils évoqueront sans doute deux choses : l’intégration des technologies d’IA de façon sécuritaire et efficace et la fiabilité des chaînes d’approvisionnement.

Pendant que les conseils sont aux prises avec ces enjeux, les autorités réglementaires ne chôment pas non plus. Le gouvernement fédéral a édicté de nouvelles règles de divulgation concernant la gestion de la chaîne logistique et élabore des balises pour ce qu’il nomme « l’adoption responsable » de l’intelligence artificielle. Les entreprises canadiennes qui atteignent certains seuils financiers doivent maintenant présenter un rapport annuel sur leurs politiques et processus utilisés pour réduire les risques de travail forcé et de travail des enfants dans la production de biens qu’ils fabriquent ou importent. Dans l’article « Combattre le travail forcé, » Jeff Buckstein décrit ce que les conseils doivent savoir sur la nouvelle loi. Dans son article sur la réglementation émergente sur l’IA, Richard Blackwell s’entretient avec des administrateurs et des avocats au sujet de ce qui s’en vient et de la manière dont les conseils devraient s’y préparer. Sur ces deux questions, certains accusent le gouvernement canadien de ne pas suivre le rythme du changement. En matière de politiques gouvernementales ratées, les spécialistes évoquent souvent la déréglementation de l‘industrie aérienne américaine en 1978 comme l’une des pires. Dans son récent ouvrage Why Flying is Miserable and How to Fix it, Ganesh Sitaraman attribue une grande partie de la situation actuelle de l’aviation commerciale aux États-Unis à la déréglementation et à la consolidation qu’elle a entraînée, une condition similaire ayant cours au Canada. Mais notre pays n’en maintient pas moins un environnement réglementaire « globalement respecté », souligne Martha Hall Findlay dans la chronique « Dilemme de l’administrateur ». Mme Findlay, directrice de l’école de politique publique de l’Université de Calgary, rappelle que nous profitons tous d’une bonne réglementation. Les efforts consentis afin de contrôler le déploiement de l’IA générative sont sur le point d’éprouver cette réputation. DJ

I HEAR A COMMON sentiment these days from the director community: Many boards are keen to “get back to the basics” of governance. Their directors want to rebalance affairs as we all try to shake the Covid-19 hangover that afflicts our society. Yes, fears of contagion have fallen, but many workers remain at home, rejecting the old office routine and ushering in a permanent hybrid-work environment. And yes, inflation has come down, but its pesky presence is still casting a pall over the economy.

On top of this hangover, we face great geopolitical change and uncertainty at home and abroad. We’re also witnessing an epic struggle between the galloping technology industry and lumbering regulatory bodies that will determine how rapid and far-reaching the effects of generative artificial intelligence (AI) will be on society. In this issue of Director Journal, we look at some of the regulations in development around AI, as well as what boards need to do to prepare.

Rahul Bhardwaj LL.B, ICD.D President and CEO, The Institute of Corporate Directors

Rahul Bhardwaj LL.B, ICD.D President and CEO, The Institute of Corporate Directors

It’s a natural inclination when we have such a myriad of variables in front of us to want to simplify and avoid being distracted by new issues that compete for our attention. As we seek simple solutions, however, it’s essential that we don’t just fall back on the easy ones.

Directors face a long journey, and the challenge of creating the right agenda in unpredictable times requires varied and diverse thinking. We need to consider perspectives beyond our own comfort zones if we are going to find the best solutions; to truly be effective, a director must have the courage to seriously consider different points of view and maintain an open mind. The Institute of Corporate Directors exists to help you achieve these goals, understanding that if we took the easy road and simply became an echo chamber, we would not be serving ICD members or the country well.

For better or worse, the world is not going back to the way things were done before the pandemic. So, by all means, look for the simple solutions, but be prepared to be challenged and confronted at every turn, as we all look for better outcomes, not easy outcomes. DJ

BEAUCOUP DE CONSEILS désirent « revenir aux bases de la gouvernance », entend-on ces jours-ci dans certains cercles d’administrateurs. Ces gens souhaitent rééquilibrer les choses alors que nous essayons tous de nous débarrasser de la gueule de bois issue de la Covid-19 qui afflige notre société. La contagion est terminée, mais beaucoup de travailleurs restent à la maison, rejetant l’ancienne routine du bureau et engagés en permanence dans un environnement de travail hybride. Oui, le taux d’inflation a fléchi, mais son ombre continue de planer sur notre économie.

En plus de cette gueule de bois, nous faisons face à des changements géopolitiques et à des incertitudes considérables ici et ailleurs. Nous sommes témoins de combats épiques entre une industrie technologique en plein essor et des autorités réglementaires lourdes qui détermineront la rapidité et l’ampleur des effets de l’intelligence artificielle générative sur la société. Dans cette édition du Director Journal, nous examinons certains développements réglementaires relatifs à l’IA et aux gestes que devront poser les conseils pour s’y préparer.

Quand on est confronté à une telle myriade de variables, il est naturel de vouloir simplifier et d’éviter d’être distrait par de nouveaux enjeux qui se disputent notre attention. Tout en cherchant des solutions simples, cependant, il est essentiel de ne pas sombrer dans le simplisme.

Les administrateurs ont une longue route devant eux et le défi d’imaginer un nouvel ordre du jour en des temps incertains exige des perspectives diverses. Pour trouver les meilleures solutions, nous devons envisager des options au-delà de notre zone de confort; pour être vraiment efficace, un administrateur doit avoir le courage d’envisager différents points de vue et de garder l’esprit ouvert. L’Institut des administrateurs de sociétés existe pour vous aider à atteindre ces objectifs. Si elle n’était qu’une simple chambre d’échos des solutions les plus faciles, elle ne servirait ni ses membres ni l’ensemble du pays. Pour le meilleur ou pour le pire, le monde ne reviendra pas aux façons de faire d’avant la pandémie. Soyons donc prêts à nous remettre en question et à être confrontés à chaque détour, dans notre recherche des meilleurs résultats et non des solutions les plus faciles. DJ

FREE PERSONAL TRAVEL on the company jet is making a comeback. In 2022, S&P 500 companies spent US$65-million so CEOs could travel in style – up 50 per cent from before the pandemic. The Wall Street Journal’s analysis finds this corporate jet-setting continued last year.

Businesses say the company jet promotes executives’ health and safety, security and efficiency. It can shuttle CEOs to other companies’ board meetings or transport them from faraway homes. It also allows executives to reach remote facilities, according to PepsiCo.

But this lavish perk doesn’t fly with everyone. Critics see it as a sign of boards too eager to please CEOs. Questionable jet use, like that of Credit Suisse’s former chair, can invite investor and regulator scrutiny. And then there’s the issue of carbon emissions: Research shows private planes pollute up to 14 times more than commercial jets.

For many large corporations, the jet isn’t worth the headache. “The vast majority of S&P 500 companies do not offer this perk,” executive pay analyst Rosanna Landis Weaver says in the Journal.

SKY’S THE LIMIT

Personal use of the company jet soared between 2019 and 2022 as some CEOs blurred the lines between work and home.

US MILLION 14% 25% $6.6

Increase in number of large companies offering private planes.

Growth in number of executives flying on the company jet.

Source: The Wall Street Journal, Equilar

Spending by Meta Platforms on personal flights for its CEO and COO in 2022 – up 55 per cent from 2019.

CEOs have long blamed remote work for hurting collaboration, innovation, productivity and culture, but new research suggests they may be wrong. A University of Pittsburgh study finds that return-to-office rules at 137 S&P 500 companies did not boost financial performance when compared to firms without mandates. What these office requirements did do is erode job satisfaction and work-life balance. Still, people believe what they want to believe, and CEOs are no different. “Executive nostalgia” for an office model that worked years ago is powerful, workplace advisor Brian Elliott says in Forbes. Bosses are unlikely to backtrack on these mandates, observes Mark Ma, who co-wrote the University of Pittsburgh study. Ma’s research also found that male CEOs and negative stock prices are more likely to result in mandates. The only winner in this office push may be the slacker. Lazy employees existed long before the pandemic and a location change won’t suddenly motivate them, says leadership coach Eileen Dooley. Instead, these laggards have mastered the art of hiding in plain sight. “Being lazy seems actually easier at the office than from home, especially when all it takes is to be seen with others,” Dooley writes in The Globe and Mail.

BECAUSE REAL LIFE ISN’T A ROMANTIC COMEDY, humans have often needed help finding a partner. Matchmakers have operated for centuries, but it was only natural that computers start playing Cupid, too.

In the 1960s, pioneers like “Operation Match,” the brainchild of two Harvard students, promised other overachievers a shot at love. Using questionnaires and a giant IBM computer, the service identified a user’s top six matches on campus, reports Canadian Business.

Although this foray into digitized dating quickly fizzled out, people didn’t stop looking for romance in innovative ways. Video dating became a way for singles to mingle in the 1970s, but users eventually dumped it for the internet.

In 1994, Web Personals became the first online dating site and by 2017, nearly 40 per cent of heterosexual couples reported meeting online. But the monetized search for a soulmate hasn’t gone smoothly. A 2015 data hack at the notorious Ashley Madison exposed more than 30 million cheating spouses, breaking hearts and upending lives around the world. And six years later, newly coupled dating platforms Match and Tinder had a lover’s quarrel that ended up in court.

The modern-day landscape is littered with dating apps, swiping left and “situationships,” but Gen Z may be over it. A recent survey finds 80 per cent of university students are focusing on meeting people in real life, while more than half say they met their current or recent partner “the old-fashioned way.”

BIG BUSINESS

US$3 – Operation Match’s user fee in 1965

US$65-million – Annual revenue of the leading video-dating service in the early 1990s

US$10.5-billion – Estimated value of the global online dating market in 2023

Sources: The Evolution by Canadian Business, Vox, Grand View Research

Birth rates around the world are in freefall. In Italy, 12 people die for every seven babies born. Last year, births in France hit a postwar low. And with its aging population, high cost of living and burned-out health-care system, Canada could join the ranks of the lowest fertility countries, such as China and Japan. World leaders are working overtime to revive reproduction, with singles mixers in Taiwan, baby bonuses in Greece and crackdowns on contraception in Iran. But the bribes and threats don’t seem to be working.

For one thing, it’s expensive to have kids these days. The prospect of a grim future filled with extreme weather events, war and eroding democracy is no incentive, either. And with the growth of education and economic productivity, people have more options today, reports Vox.

“We always hear that it takes a village [to raise a child], but that village is not what it used to be,” says Alison Gemmill, a professor at John Hopkins University in Baltimore. That said, the right policies may bring babies back. Better jobs, paid leave, affordable child-care and parental supports can encourage people to have children, experts tell Vox. Creating conditions that build trust in governments and an optimistic outlook could be the solution to falling fertility – and many of the woes that ail society.

When it comes to artificial intelligence, business leaders are walking a tightrope. A PwC survey of Canadian CEOs finds that half expect generative AI to improve the quality of their products and services in 2024, while more than half said it increases the risks of data security and misinformation. As CEOs grapple with this tension between moving too fast or falling behind, all eyes are on the workforce. Most CEOs agree that workers will need significant training in the next three years, while 14 per cent think AI will reduce headcount in the next year.

RISK ANALYSIS

Percentage of Canadian CEOs who expect generative AI will raise these business risks this year.

Source: PwC Canada, 27th Annual Global CEO Survey—Canadian insights

IS ESG IN TROUBLE? The Wall Street Journal reports companies are removing the term from reports, committees and job titles. Instead, leaders are pivoting to alternatives like “responsible business” and “rational sustainability,” while remaining committed to the concept. A recent survey by the consulting firm Teneo finds that 92 per cent of global

CEOs and institutional investors plan to stay the course with ESG. This plan may be a good thing. According to an analysis by two research fellows at Claremont Graduate University, well-managed organizations integrate ESG. According to management scholar Peter Drucker, overall effectiveness is “doing the right things well.”

Overall effectiveness represents scores across customer satisfaction, employee engagement and development, innovation, social responsibility and financial strength. Among 442 companies measured by the Drucker Institute, the 50 biggest gainers in overall effectiveness between 2018 and 2023 improved in each of these categories.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

In an era of evolving governance challenges, the Conference offers unparalleled insights in governance, leadership, and innovation. Gain valuable perspectives from over 25 leaders and governance experts, connect with your director community, and contribute to governance excellence through discussions, workshops, and forums.

CONFERENCE CO-CHAIR

HON. JOHN P. MANLEY PC, O.C., F.ICD

CONFERENCE KEYNOTE

GERALD BUTTS Vice Chair and Senior Advisor, Eurasia Group

CONFERENCE CO-CHAIR

HEATHER MUNROE-BLUM O.C., OQ, F.ICD

CONFERENCE KEYNOTE

STEPHEN POLOZ

Special Advisor, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP and Former Bank of Canada Governor

CONFERENCE CO-CHAIR

POONAM PURI LSM, LL.M, ICD.D

FELLOWSHIP GALA KEYNOTE

DAVID L. COHEN U.S. Ambassador to Canada

between

WHEN A FALLING OUT OCCURS between an organization’s CEO and its board, the results are neither pretty nor healthy for the organization and its stakeholders. Witness the current conflicts at Gildan Activewear Inc., involving its former CEO, the board of directors and various shareholders regarding CEO succession and overall organizational direction. Rogers Communications Inc. is still dealing with fallout from conflicts among controlling shareholders and its former board over who should serve as CEO. And not long ago, OpenAI – the company behind ChatGPT – saw its CEO terminated, only to be reinstated less than two weeks later by the same board as a result of intense pressure from shareholders and customers, as well as threats of wholesale resignation by members of the senior management team.

These high-profile events are clear examples of governance failures that destroy value and unnecessarily disrupt organizational performance. But they are, in fact, only the tip of the iceberg. They highlight the extreme negative implications of a much more generic governance problem: the disruptions that arise from a lack of alignment between the CEO and board regarding fundamental issues of strategic direction and organizational priorities, not to mention CEO performance and tenure.

In order to ensure that such unhealthy dynamics do not get to the point of the significant disruptions reflected in the cases mentioned above, directors must ask themselves the following questions:

• Are the board and the CEO aligned on vision?

• Are the board and the CEO aligned on the key strategic priorities that must be addressed to make that vision a reality?

• Have we as a board put in place the communication and collaboration mechanisms necessary to bring conflicts to the surface and provide a process for achieving alignment between ourselves and the CEO?

The board has a responsibility to exercise oversight of the CEO on an ongoing basis. This requires the board to have in place effective processes for facilitating candid and constructive conversations with the CEO regarding shared vision, agreement on key strategic priorities required to make that vision a reality, and their expectations of the CEO as a leader.

One of the key mechanisms for encouraging this type of dialogue is a well-designed and effectively implemented CEO evaluation process. Such a process achieves a number of critical objectives. First, it reinforces who is in charge. Founder-CEOs and other long-serving

Effective governance requires that the board and the CEO agree on the organization’s vision and strategy.

CEOs sometimes need a reminder that final authority on key issues rests with the board, not the CEO. Second, such a process provides the CEO with constructive feedback on what they are doing effectively and where they have the potential to improve their performance. A curious CEO truly motivated to achieve their full potential will welcome feedback as a necessary precursor for learning and development. And finally, a robust CEO evaluation process creates a forum for regular conversations between the CEO and the board regarding long-term vision for the organization, including the longterm leadership needs of the organization beyond the term of the current CEO.

Regular, candid conversations about the mutual expectations of the board and the CEO regarding the timeframe of the CEO’s appointment, the readiness of potential successors and the importance of ensuring a smooth transition to the next generation of leadership are fundamental components of the effective governance directors are responsible for providing. DJ

HUGH ARNOLD is an adjunct professor of management at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, where he is also executive-in-residence of organizational behaviour and human resources management. His consulting practice, Hugh Arnold Associates Ltd., specializes in organizational strategy and structure, leadership development and corporate governance.

What can boards do to deal

THE SIMPLE ANSWER to this question is: “Not much!” It’s not the board’s job to decide how to deal with new or increased regulation. Nor is it the job of individual directors (no matter how knowledgeable or connected they might be) to lobby or advocate for more, less or better regulation. The job of an informed director is to provide oversight and to offer advice, if warranted, to those in the organization who will be lobbying or advocating – not to engage directly, however tempting that may be.

It is the board’s job, however, to make sure that management is on top of the regulatory environment in which the organization operates. The board must be confident that the management team understands the rules that apply to it, that senior managers are monitoring potential and impending changes, and that they understand the role of public opinion when it comes to politically driven regulatory decisions, and engage accordingly. Of course, it is management that must address new or additional regulations and ensure compliance, with the bottom line in mind. For the board, the appropriate “noses in” but “fingers out” questioning is key. Having been involved in both the public policy and corporate environments, I am struck by how many people in the corporate

world assume that public policy knowledge and expertise is only for governments, politicians and bureaucrats. The development of policy frameworks and, ultimately, regulatory decisions affect our business operating environments – often dramatically. Anticipating what might be coming in terms of regulation, and why, can allow both management and board members to be proactive. Understanding public policy – knowing how regulatory “sausages are made” – is knowledge and experience that should be more present both on boards and in management.

Finally, as a proud Canadian, I would urge caution with the notion that more regulation is always bad. We all benefit from good regulation. Yes, we have every right to be frustrated by delays to project timelines and things taking too long to build, by political overreach, by government interfering unnecessarily in decisions that should be determined by markets. But despite its imperfections, Canada has a globally respected regulatory environment on issues such as competition, the rule of law, transparency, environmental protection, human rights, diversity and inclusion, and more. Canadian businesses are correspondingly highly regarded in ESG (environment, social and governance) metrics, trust, anti-corruption and sustainability rankings. This is important to customers, employees and other stakeholders, and is something of which Canadians may be proud.

MARTHA HALL FINDLAY, ICD.D, is the director of the school of public policy at the University of Calgary. Her previous roles include serving as chief sustainability officer and chief climate officer for Suncor Energy and CEO of the Canada West Foundation. As a Member of Parliament between 2008 and 2011, she served in the Official Opposition shadow cabinet as the critic for international trade, finance, government works and public services, and transportation, infrastructure and communities.

LA RÉPONSE SIMPLE à cette question est : « Pas grand-chose! » Ce n’est pas au conseil de décider comment faire face à une réglementation nouvelle ou accrue. Ce n’est pas non plus le rôle des administrateurs d’exercer des pressions en faveur d’une réglementation moindre, plus robuste ou meilleure. La tâche d’un administrateur

informé est de fournir de la surveillance et des conseils aux gens de l’organisation qui exerceront de telles pressions et non pas de s’engager directement.

C’est la tâche du conseil, toutefois, de s’assurer que la direction est bien au fait de son environnement réglementaire. Le conseil doit avoir confiance que l’équipe de direction comprend les règles, que les hauts dirigeants surveillent les changements éventuels et imminents et qu’ils comprennent le rôle de l’opinion publique à l’égard des décisions réglementaires dictées par des considérations politiques et se gouvernent en conséquence. Bien sûr, c’est à la direction de gérer la réglementation et de s’y conformer, en gardant à l’esprit les résultats financiers

Ayant été engagée à la fois en politique publique et dans des environnements d’entreprise, je suis frappée par le nombre de gens d’affaires qui présument que les connaissances et l’expertise en matière de politiques publiques ne touchent que les gouvernements, les politiciens et les fonctionnaires. Le développement des cadres de politiques et, ultimement, les décisions réglementaires affectent nos environnements d’affaires – parfois radicalement. En prévoyant ce qui est susceptible de se produire en matière de réglementation, la direction et le conseil sont proactifs. La compréhension d’une politique publique représente la connaissance et l’expérience nécessaires au sein d’une organisation.

Enfin, à titre de fière Canadienne, j’exhorte les gens à la prudence

quant à l’idée que plus de réglementation est toujours une mauvaise chose. Nous profitons tous d’une bonne réglementation. Nous avons tout à fait le droit d’être frustrés par les délais d’exécution des projets, les exagérations de certaines politiques, les interventions inutiles du gouvernement dans des décisions qui devraient être déterminées par les marchés. Mais en dépit de ses imperfections, l’environnement réglementaire du Canada est respecté dans le monde entier sur des enjeux comme la concurrence, la règle de droit, la transparence, la protection de l’environnement, les droits de la personne, la diversité et l’inclusion, pour ne citer que ceux-là. De la même façon, les entreprises canadiennes sont hautement considérées pour leurs mesures ESG ainsi que leurs performances en matière de confiance, de mesures anti-corruption et de développement durable. Cela est important aux yeux des clients, des employés et autres parties prenantes et les Canadiens devraient en être fiers.

MARTHA HALL FINDLAY, IAS.A, est directrice de l’école de politique publique de l’Université de Calgary. Elle a précédemment été responsable du développement durable et de la stratégie climatique chez Suncor Energy et cheffe de la direction de la Fondation Canada West. Députée fédérale de 2008 à 2011, elle fut critique de l’Opposition officielle en matière de commerce international, de finances, de travaux publics et services gouvernementaux, de transport et d’infrastructures et communautés.

(With input from Robin Phillips and Shayla Praud)

IN RECENT YEARS, corporate boards have experienced a rise in the number of rules and requirements they must satisfy. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns are leading to increased government regulation as corporate governance continues to evolve. There is greater emphasis on transparency and accountability, as well as a growing number of disclosure and reporting requirements. Interestingly, the concept of stringent reporting is not unfamiliar territory for Indigenous communities. Corporate directors might look to their experience for some valuable perspective. First Nation governments have long been accustomed to regulatory limitations and rigorous reporting requirements, particularly in the context of finances and spending. For example, funding agreements that First Nations enter into with the Crown to fund important services on reserves are often accompanied with extensive financial and progress reporting requirements, as well as restrictions in how those services may be implemented.

To remove themselves from a reliance on Crown funding and government oversight, many First Nations are creating corporations to engage in independent revenue-generating activities through economic development. In the pursuit of economic growth and self-sufficiency, numerous First Nations and their business entities are proactively engaging with a diverse range of potential partners.

Simultaneously, non-Indigenous companies are increasingly looking into business and resource opportunities on First Nations’ territories. Many of these companies are attempting to work with First Nations by consulting with First Nations governments and trying to find ways to benefit First Nations communities. As a result, some boards and investors have already developed ESG-focused business practices and responsible investment practices.

ESG-type considerations have long guided decision-making for Indigenous governments, and in many ways also guide Indigenous corporate decision-making today. These elements are rooted in traditional laws and practices, and many Indigenous communities and companies are eager to see them implemented in contemporary frameworks.

To address increasing regulations related to ESG factors, boards would benefit from bringing Indigenous perspectives and voices to the table. By appointing Indigenous board members — as well as creating and fostering positive relationships with Indigenous businesses, communities, and legal orders — boards can benefit from Indigenous knowledge and governance practices while also learning to thrive within a new ESG-focused corporate world. DJ

BERND CHRISTMAS, ICD.D, is senior cousel at JFK Law LLP. His previous roles include serving as CEO of the Membertou Band of Nova Scotia and the Membertou Corporate Division, senior vice-president and national aboriginal practice leader at Hill & Knowlton Canada, and CEO of Fort McKay Oil Sands. ROBIN PHILLIPS is an associate at JFK Law and SHAYLA PRAUD is an articling student.

CES DERNIÈRES ANNÉES, les entreprises ont connu une augmentation du nombre de règlements et d’exigences auxquels elles doivent se conformer. Les préoccupations environnementales, sociales et de gouvernance (ESG) mènent à une réglementation accrue des gouvernements alors que la gouvernance d’en5treprises continue d’évoluer. La transparence et la reddition de comptes gagnent en importance ainsi que le nombre d’exigences en matière de divulgation et de rapports. Il est intéressant de noter que l’exigence stricte de rapports est familière aux communautés autochtones. Les administrateurs d’entreprises gagneraient à examiner cette expérience. Les gouvernements des Premières nations sont depuis longtemps astreints à des limites réglementaires et à de strictes exigences de rapport, particulièrement dans un contexte de finances et de dépenses. Ainsi, les ententes de financement d’importants services sur les réserves conclues entre eux et le gouvernement sont souvent assorties d’exigences très strictes en matière de rapports financiers et d’avancement de travaux et de restrictions quant à la manière dont ces services peuvent être mis en œuvre.

Pour se libérer de la surveillance et du financement du gouvernement, plusieurs Premières Nations créent des sociétés indépendantes dont les activités sont génératrices de revenus grâce au développement économique. Dans cette poursuite de croissance économique et d’auto-suffisance, beaucoup d’entre elles s’associent à toute une gamme de partenaires.

Simultanément, des entreprises non autochtones recherchent de plus en plus des occasions d’affaires sur les territoires des Premières Nations et tentent de collaborer avec celles-ci. Ainsi, certains conseils et investisseurs ont déjà développé des pratiques d’entreprises axées sur les ESG et des pratiques d’investissement responsable.

Les considérations de type ESG guident depuis longtemps le processus de décision des gouvernements autochtones. Cela est ancré dans les lois et pratiques traditionnelles et les communautés désirent mettre en œuvre ces processus dans un cadre contemporain. Pour répondre à la réglementation croissante liée aux facteurs ESG, les conseils profiteraient de points de vue autochtones à leur table. En nommant des membres autochtones, les conseils pourraient profiter de leurs connaissances et pratiques de gouvernance tout en apprenant à prospérer dans un univers axé sur les facteurs ESG. DJ

BERND CHRISTMAS, IAS.A, est avocat principal chez JFK Law LLP. Il a précédemment été chef de la direction de la Bande Membertou de Nouvelle-Écosse et de la Membertou Corporate Division, vice-président principal et leader de la pratique autochtone nationale chez Hill & Knowlton Canada ainsi que chef de la direction de Fort McKay Oil Sands. ROBIN PHILILIPS est associé chez JFK Law et SHAYLA PRAUD est stagiaire en droit.

As Ottawa finalizes its rule book governing how organizations can use artificial intelligence, boards had better get up to speed quickly, Richard Blackwell writes Alors qu’Ottawa finalise les règles d’utilisation de l’intelligence artificielle par les organisations, les conseils devraient s’y préparer, écrit Richard Blackwell

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE is a double-edged sword that has been handed to organizations and their directors: a powerful tool that can forge vast new opportunities and efficiencies, but also a technology that can do a lot of damage.

To ensure that AI will generate more benefits than harm, governments are using their own favoured tool — regulation — to try to protect individuals from AI abuses. In Canada, the federal government is in the process of developing a set of guardrails for what it calls “responsible adoption” of AI technologies. This new law will create a fresh set of concerns for managers and directors of businesses and not-for-profits. Boards, already burdened with the oversight of a wide range of risks, will have to operate within what will likely be a complex AI regulatory environment.

AI has already become a central topic in boardroom discussions, said Jo Mark Zurel, a director at Fortis Inc., Major Drilling Group International Inc. and Highland Copper Co. Inc. “There is a lot of excitement about the prospect of using generative AI to create competitive advantage and efficiency. But there is a lot more concern around the risks, including privacy, inadvertent sharing of confidential company information, and errors from misuse.”

As AI seeps into more and more operations in every industry, directors “will have [new] responsibility, with or without regulation,” Zurel said. For companies operating internationally, “there is a patchwork of regulation emerging,” and now Canada is following suit.

Canada’s AI regulation will be established by legislation called the Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, or AIDA, which is contained in the broader Digital Charter Implementation Act now wending its way through Parliament. The government says it is responding to public concerns, citing research that shows a large majority of Canadians believe AI can cause harm to society. The surveys also show that trust could be boosted if the technology is regulated by public authorities. The goal, Ottawa says, is to avoid stifling innovation, while cutting the risk of discrimination, bias and fakery in AI applications that can hurt individuals. At the same time, Ottawa is striving to ensure its rules are compatible with those being developed by other countries. The United States, for example, has already acted through an executive order that sets out principles for safe development and use of AI.

At this stage, it is difficult to determine exactly what organizations will be required to do to comply with the new legislation. The specifics on compliance will only come when detailed regulations are published some time ahead of implementation, which will not happen before 2025. So far, the description of compliance activity in the legislation is vague. The government says organizations developing AI will have to “identify and address risks with regards to harm and bias,” while those managing AI systems will have to “monitor and mitigate” risks.

The plan for AIDA is to focus regulation on “high-impact” AI systems, those where the potential harm is most severe, particularly for groups who might already be marginalized. It would create an oversight body, prohibit reckless or malicious uses of AI, and set financial penalties for anyone who breaches the law.

L’INTELLIGENCE ARTIFICIELLE est une arme à deux tranchants : un outil puissant capable d’ouvrir de vastes opportunités et sources d’efficacité nouvelles, mais aussi une technologie susceptible de causer bien des dégâts.

Pour s’assurer que l’IA génère plus d’avantages que de torts, les gouvernements s’en remettent à la réglementation. Au Canada, le gouvernement fédéral est à élaborer une série de balises en vue de d’une « adoption responsable » des technologies d’IA. La nouvelle législation suscitera un tout nouvel ensemble de préoccupations pour les administrateurs. Les conseils, qui assument déjà la surveillance d’un large éventail de risques, devront fonctionner dans un environnement réglementaire qui sera sans doute de plus en plus complexe.

L’IA est déjà une question centrale dans les discussions des conseils, souligne Jo Mark Zurel, administrateur chez Fortis, Major Drilling Group International et Highland Copper. « Il y a beaucoup d’enthousiasme face à l’IA générative. Mais il y a encore plus de préoccupations quant à ses risques, dont la confidentialité, le partage involontaire de renseignements confidentiels et les erreurs découlant d’une mauvaise utilisation. »

Alors que l’IA s’infiltre dans les activités de chaque industrie, les administrateurs « auront de plus en plus de nouvelles responsabilités, avec ou sans réglementation », explique M. Zurel.

La réglementation canadienne sur l’IA figurera dans une législation appelée Loi sur l’intelligence artificielle et les données, ou LIAD, intégrée à la plus globale Charte canadienne du numérique qui se fraie présentement un passage au Parlement. Le gouvernement affirme que celle-ci répond aux préoccupations du public, citant une étude montrant qu’une vaste majorité de Canadiens croit que l’IA peut causer du tort à la société. L’étude montre aussi que leur confiance à cet égard peut être accrue si la technologie est réglementée. L’objectif, dit Ottawa, est d’éviter de freiner l’innovation tout en réduisant le risque de discrimination, de biais et de truquage dans les applications d’IA susceptibles de causer du tort aux personnes. Du même souffle, Ottawa s’efforce de faire en sorte que ses règles soient compatibles avec celles d’autres pays. Les États-Unis, par exemple, ont déjà adopté un ordre exécutif établissant les principes d’un développement et d’un usage sécuritaire de l’IA.

À ce stade, il est difficile de déterminer exactement quelles organisations devront se conformer à la nouvelle législation. Les précisions à cet égard ne seront pas connues avant 2025. Jusqu’à maintenant, la description de conformité demeure vague dans la législation. Le gouvernement explique que les organisations développant des technologies d’IA devront « identifier et traiter les risques en matière de préjudice et de biais » tandis que celles gérant des systèmes d’IA devront « surveiller et atténuer » les risques.

L’objectif de la LIAD est de centrer la réglementation sur les systèmes d’IA à « incidence élevée », soit ceux où les dommages potentiels sont plus graves, en particulier pour les groupes qui pourraient déjà être marginalisés. Elle créerait un organisme de surveillance, interdirait l’utilisation irresponsable ou malicieuse de l’IA et imposerait des sanctions financières à quiconque contreviendrait à la loi.

The AIDA legislation was introduced in June 2022, and has come under fire from some quarters. At a committee hearing last fall, several presenters, including Jim Balsillie, former co-chair and co-CEO of Research In Motion Ltd. (now BlackBerry), called for the proposed regulations to be scrapped entirely, and for the government to go back to the drawing board. Among the numerous concerns expressed were the lack of a fully independent regulator, insufficient public consultation, and the fact that the law does not cover government institutions. Others said the law should include a registry for organizations developing AI systems.

One repeated criticism was the vague definition of what constitutes a “high-impact” AI system. The Washington-based Information Technology Industry Council, for example, said the law should be narrowed to “focus on uses ... that could have a significant negative impact on people, especially related to health, safety, freedom, discrimination, or human rights.” Some critics, including McGill University AI governance researcher Ana Brandusescu, told the committee that the bill will not properly protect workers, such as writers or designers, for example, who may be displaced by AI systems, or taxi drivers who might lose their jobs to autonomous vehicles. She, too, said Ottawa should start over again and hold public consultations with a wide range of groups, including often-marginalized workers such as truck drivers and gig workers.

La LIAD, déposée en juin 2022, a essuyé des critiques. Lors d’une audience en comité tenue l’automne dernier, certains intervenants –dont Jim Balsillie, ex-coprésident du conseil et chef de la direction de Research in Motion (aujourd’hui Blackberry) – a réclamé que le projet actuel soit entièrement abandonné et demandé au gouvernement de retourner à sa planche à dessin. Parmi les nombreuses préoccupations exprimées figuraient notamment l’absence d’une autorité réglementaire complètement indépendante, une consultation publique insuffisante et le fait que la loi ne s’applique pas aux institutions gouvernementales. D’autres ont aussi soutenu que la loi devrait inclure un registre des organisations qui élaborent des systèmes d’IA. Une critique fréquente touchait aussi la définition vague de ce qui constitue une « incidence élevée » d’un système d’IA. Ainsi, l’Information Technology Industry Council, établi à Washington, affirme que la loi devrait se limiter à « cibler les usages … qui pourraient avoir un impact négatif sur les gens, surtout en ce qui concerne la santé, la sécurité, la liberté, la discrimination ou les droits de la personne. » Certains critiques, dont la chercheuse en gouvernance de l’intelligence artificielle de l’Université McGill Ana Brandusescu, ont affirmé au comité que le projet de loi ne protège pas adéquatement les travailleurs tels que les rédacteurs ou les créateurs qui pourraient être remplacés par des systèmes d’IA ou les chauffeurs de taxi qui pourraient perdre leur emploi au profit de véhicules autonomes. Elle croit aussi

‘There is a lot of excitement about the prospect of using generative AI to create competitive advantage and efficiency. But there is a lot more concern around the risks, including privacy, inadvertent sharing of confidential company information, and errors from misuse.’

« Il y a beaucoup d’enthousiasme face à l’IA générative. Mais il y a encore plus de préoccupations quant à ses risques, dont la confidentialité, le partage involontaire de renseignements confidentiels et les erreurs découlant d’une mauvaise utilisation. »

— Jo Mark Zurel, corporate director

In response to some of these concerns, amendments were introduced in November 2022 to specify more precisely what “highimpact” AI means. The refined list includes AI systems used in employment decisions, AI that determines who qualifies to receive any kind of service, AI systems that use biometric information, and AI in search engines, social media, health care, courts and policing. The amendments also strengthened the independence of the AI data commissioner.

While there has been much negative feedback on the proposed law, there is also considerable support. A large group of Canadian AI researchers and businesses published a letter strongly backing the government’s move and urging it to act quickly. The 75 signatories — including many executives of AI startups, university researchers and policy analysts — said that the direction of the proposed legislation is “sound” and “agile enough to adapt to new capabilities and applications of AI as it continues to evolve.”

The proposed regulations are necessary to encourage responsible development of AI systems, prevent misuse and foster trust in the technology, said Humera Malik, CEO and co-founder of Toronto-based industrial AI developer Canvass AI, and one of the signatories of the letter. “Creating an environment of safe and responsible use of AI is paramount to promote wider adoption,” she said.

The legislation has been improved with the amendments, Malik added, and discussions are under way to beef it up further. Among her concerns are potential costs and barriers for AI startups, and the need for clearer definitions of risks. She would also like to see an expanded list of “high-impact” systems, a tiered structure where compliance requirements differ depending on the size and risk profile of companies, and clarity on enforcement mechanisms. Over all, she said, the jury is still out on whether the proposed AI regulation will mitigate risks by protecting privacy, security and fairness, or whether it will stifle innovation and add costs.

qu’Ottawa devrait recommencer à zéro et tenir des consultations publiques auprès d’une gamme élargie de groupes, dont les travailleurs marginalisés tels que les camionneurs et les employés du spectacle. En réponse à ces préoccupations, des amendements ont été présentés en novembre 2022 afin de préciser la signification de l’IA à « incidence élevée ». Cette liste plus détaillée comprend les systèmes d’IA utilisés dans les décisions d’emploi, soit ceux qui déterminent qui est admissible à recevoir tout type de service, qui utilisent des renseignements biométriques ainsi que l’IA dans les moteurs de recherche, les médias sociaux, les soins de santé, les tribunaux et la surveillance policière. Ces amendements renforçaient aussi l’indépendance du commissaire aux données provenant de l’IA.

Des progrès

Même s’il y a eu beaucoup de commentaires négatifs envers le projet de loi, celui-ci jouit également d’un soutien considérable. Un groupe important de chercheurs et représentants d’entreprises a publié une lettre de soutien au gouvernement en l’enjoignant à agir rapidement. Les 75 signataires – dont plusieurs dirigeants d’entreprises en démarrage, chercheurs universitaires et analystes de politiques – ont affirmé que la direction indiquée par la législation proposée est saine et « suffisamment flexible pour s’adapter aux nouvelles capacités et applications de l’IA au fur et à mesure que la technologie évolue ».

La réglementation proposée est nécessaire pour encourager le développement responsable de systèmes d’IA, prévenir la mauvaise utilisation et stimuler la confiance dans la technologie, soutient Humera Malik, cheffe de la direction et cofondatrice du promoteur d’IA industrielle Canvass AI de Toronto et l’une des signataires de la lettre. « La création d’un environnement favorisant l’utilisation sécuritaire et responsable de l’intelligence artificielle est primordiale pour en assurer une large adoption », dit-elle.

Les amendements ont amélioré la législation, ajoute Mme Malik, et les discussions en cours lui donneront encore des muscles. Parmi ses préoccupations figurent les coûts éventuels et les obstacles pour les en-

The AIDA legislation is designed to cover “high-impact” uses of AI technology, including its use in: La LIAD est conçue pour couvrir les usages à « incidence élevée » de l’IA, y compris pour :

1. Recruitment and employment, where the system might incorporate existing biases.

2. Determining who will get a service, where there could be discrimination.

3. Processing biometric information, where discrimination could be built in.

4. Social media or other online communications platforms, where biases may exist.

5. Health care or emergency services, including triage, where there could be discrimination.

6. Courts or administrative bodies, where historical data could perpetuate biases.

7. Policing, where biases can be built in.

1. Le recrutement et l’embauche, où le système pourrait intégrer des biais existants.

2. Déterminer qui obtiendra un service, où il pourrait y avoir discrimination.

3. Traiter les renseignements biométriques, où de la discrimination pourrait être intégrée au système.

4. Les médias sociaux ou autres plates-formes de communications en ligne, où un biais pourrait exister.

5. Les soins de santé ou services d’urgence, dont le triage, où il pourrait y avoir discrimination.

6. Les tribunaux ou corps administratifs, où des données historiques pourraient perpétuer des biais.

7. Les opérations policières, où des biais pourraient être intégrés au système.

While the proposed AI law is still a moving target, it is clear any new regulatory regime will create an additional set of oversight obligations for a wide range of organizations that create or use AI in their operations. Even entities that merely manage AI systems will have to monitor for possible harms, put safeguards in place, report any incidents, and work to mitigate those risks. And any company using an AI algorithm where clients might think they are interacting with a human being — but are not — will have to make sure those customers are informed they’re dealing with a machine. That rule will apply for any AI system, not just those that fall into the “high-impact” category.

Michael Fekete, a partner at Toronto law firm Osler Hoskin and Harcourt LLP who specializes in technology, said directors need to examine their management teams and assess whether they have the skills and expertise to understand the AI systems being developed and used in their organizations. “Once this law comes into force, essentially every organization of any size will need to be concerned about compliance.”

The demand for AI talent means there will likely be a huge “skills gap” he said, and companies will pay a premium to hire people who understand the technology and its regulation. Directors also need to make sure there is an AI governance framework in their organization, and create an inventory of all the AI systems in use, whether they are internally created or they come from outside suppliers, Fekete said. They also need to look into the future and get a sense of the areas where AI may be added in the years to come.

treprises d’IA en démarrage ainsi que la nécessité d’une définition plus claire des risques. Elle souhaite aussi voir une liste élargie des systèmes à « incidence élevée », une structure à plusieurs niveaux dont les exigences de conformité différeraient selon la taille et le profil de risque des entreprises et de la clarté dans les mécanismes d’application.

Même si le projet demeure une cible mouvante, il est clair que tout régime réglementaire nouveau suscitera un ensemble additionnel d’obligations de surveillance pour un large éventail d’organisations qui créent ou utilisent l’IA dans leurs activités. Même des entités qui ne font que gérer des systèmes devront en surveiller les dommages éventuels, mettre en place des balises, rapporter tout incident et s’efforcer d’atténuer les risques. Toute entreprise utilisant un algorithme d’IA là où les clients croient interagir avec un être humain – ce qui n’est pas le cas – devront s’assurer que ces clients sont informés du fait qu’ils échangent avec une machine.

Michael Fekete, associé du cabinet juridique Osler Hoskin et Harcourt LLP spécialisé en technologie, estime que les administrateurs devront examiner leurs équipes de direction et évaluer si leurs membres ont les compétences et l’expertise nécessaires pour comprendre les systèmes d’IA au sein de leurs organisations. « Une fois que la loi sera en vigueur, chaque organisation – peu importe sa taille – devra se préoccuper de conformité. »

La demande de talents en IA signifie qu’il y aura sans doute une immense pénurie de compétences, soutient-il. Les entreprises verseront une prime pour embaucher des gens qui comprennent la technologie

As boards grapple with the use of artificial intelligence in their organizations, directors must develop a clear understanding of the technology and its governance. The consultancy KPMG has recently published a document called “Preparing Your Board for Generative AI.” Among the recommendations:

• Establish a dedicated AI governance committee that reports to the board. It should include executives dealing with technology, risk, data, IT, legal, sales and marketing.

• Get up to speed on AI, its benefits and risks, and how it is already being used in your organization.

• Set and approve an AI strategy.

• Make sure employees are on side, by updating them on technological advances, and being transparent about AI plans.

• Make sure that ethical guardrails for the use of AI in your organization are clearly defined.

• Understand current and proposed AI regulation, in Canada and wherever your organization operates.

• Understand incident procedures for when things go wrong.

-RBFekete said directors who are familiar with existing European Union legislation governing AI may be surprised to find that the Canadian law, as it is now drafted, will be much broader than that in the EU. In Europe, regulation focuses tightly on AI systems where there is a significant risk of harm, whereas Canada pulls in far more activities under the “high-impact” umbrella.

“Directors can’t assume that, if they’re complying with the EU [rules], then they will be complying in Canada,” he said. “There is a much broader scope that you have to worry about in Canada.”

Fekete also notes that the penalties for breaching the law will be significant. Fines of up to 5 per cent of an organization’s worldwide revenue would come into play if, for example, an organization doesn’t properly test its system to make sure it is fair to users. Stiffer penalties that include imprisonment would be for the most serious criminal offences, such as when a creator knew an AI system would cause serious harm. However, the draft law does not hold directors accountable for the acts or omissions of employees.

Bernice Karn, a lawyer in the information technology and data privacy group at Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP in Toronto,

Alors que les conseils commencent à saisir l’usage de l’intelligence artificielle dans leurs organisations, les administrateurs doivent développer une compréhension claire de la technologie et de sa gouvernance. KPMG a récemment publié un document intitulé « Préparer votre conseil d’administration à l’IA générative ». Parmi les recommandations, citons :

• Établir un comité du conseil consacré à la gouvernance de l’IA. Il devrait comprendre des dirigeants des cadres chargés de la technologie, du risque, des données, des TI, des ventes et du marketing.

• Actualiser les connaissances sur l’IA, ses avantages et ses risques ainsi que la manière dont elle est déjà utilisée dans l’organisation.

• Concevoir et adopter une stratégie d’IA.

• S’assurer que les employés sont impliqués en actualisant leurs connaissances sur les avancées technologiques et en étant transparent quant aux projets d’IA.

• S’assurer de définir clairement des balises éthiques pour l’usage de l’IA dans l’organisation.

• Comprendre la réglementation de l’IA au Canada et partout où l’organisation est présente.

• Comprendre les procédures à observer en cas d’incident.

-RB

et sa réglementation. Les administrateurs devront aussi s’assurer qu’il y a un cadre de gouvernance de l’IA au sein de leur organisation et créer un inventaire de tous les systèmes en vigueur, qu’ils soient ou non créés à l’interne ou provenant de fournisseurs, dit M. Fekete.

Celui-ci affirme que les administrateurs familiers avec la législation de l’Union européenne pourraient être étonnés de constater que la loi canadienne, telle qu’ébauchée, aura une portée beaucoup plus large. En Europe, la réglementation est étroitement centrée sur les systèmes d’IA qui présentent un risque important, alors que celle du Canada couvre beaucoup plus d’activités sous le parapluie des « incidences élevées ».

« Les administrateurs ne peuvent pas présumer que s’ils se conforment aux règles européennes, ils observeront la loi canadienne », dit-il.

Me Fedeke souligne aussi que les sanctions encourues seront plus importantes. Des amendes pouvant aller jusqu’à 5 pour cent des revenus mondiaux d’une organisation pourraient être imposées si, par exemple, celle-ci ne teste pas convenablement ses systèmes pour s’assurer qu’ils sont équitables pour ses utilisateurs. Des pénalités encore plus sévères – y compris l’emprisonnement –seraient imposées aux infractions criminelles les plus graves, par

said companies will have to balance their obligations to monitor, document and disclose what they are doing with their efforts to maintain the privacy and confidentiality of the intellectual property in their operations. For example, a financial firm that uses AI for credit scoring might be leery of revealing details of its algorithms, which may be the “secret sauce” of their particular credit model.

Unfortunately, trying to get ahead of the game will be difficult, Karn said, since the details of the regulations are still to come. The AI industry is also changing so quickly that some aspects of the legislation could be out of date by the time it is finally passed and implemented. She recommends that companies, in the meantime, examine the voluntary code of conduct that was released by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada last September. It outlines a relatively simple set of measures organizations can take to ensure they are properly dealing with AI risks. “The government is trying to signal a road map here,” Karn said, and following the voluntary measures will help organizations comply once the mandatory regulations are in place. DJ

RICHARD BLACKWELL is a former business reporter at the Financial Post and The Globe and Mail. Over three decades, he covered many sectors, including technology, financial services, media and energy.

exemple lorsqu’un créateur sait qu’il cause des dommages importants. Toutefois, le projet de loi ne tient pas les administrateurs responsables des actes ou omissions des employés.

Bernice Karn, avocate spécialisée du groupe technologie de l’information et confidentialité des données chez Cassels Brock et Blackwell LLP de Toronto, explique que les entreprises devront équilibrer leurs obligations de surveiller, documenter et divulguer leurs gestes et leurs efforts pour maintenir le respect de la vie privée et la confidentialité de la propriété intellectuelle dans leurs opérations. Ainsi, une institution financière qui utilise l’IA pour les évaluations de crédit pourrait être méfiante à l’idée de révéler des détails de ses algorithmes.

Malheureusement, il sera difficile de se donner une longueur d’avance, prévient Mme Karn, car les détails de la réglementation sont encore à venir. L’industrie de l’IA change si rapidement que certains aspects de la législation pourraient être périmés lorsque celleci sera adoptée. Elle recommande que dans l’intervalle, les entreprises examinent le code de conduite volontaire émis en septembre dernier par Innovation, Sciences et Développement économique Canada. Ce code décrit un ensemble relativement simple de mesures que les organisations peuvent prendre pour s’assurer qu’elles gèrent convenablement les risques associés à l’IA. DJ

RICHARD BLACKWELL a été journaliste d’affaires au Financial Post et au Globe and Mail.

With board implosions and community clashes, theatre companies have had a tumultuous run in the past few years. It’s time to reimagine how we govern the arts, writes Prasanthi Vasanthakumar

Implosions de conseils et affrontements communautaires : les compagnies de théâtre ont connu des moments tumultueux ces dernières années. Il est temps de réinventer la gouvernance du monde des arts, écrit Prasanthi Vasanthakumar

BY

A still from Why Not Theatre’s production of Prince Hamlet. The company’s board has a mandate to review its governance structure as part of a larger effort to support the organization in innovative ways.

‘We don’t spend 90 per cent of our time on the financials,’ says one board member.

SOON AFTER COVID-19 made its grand debut in 2020, two wellloved theatre companies had a public meltdown. In Toronto, Buddies in Bad Times Theatre – the world’s largest and longest-running queer theatre company – was embroiled in a conflict between staff and the board over the direction of the company and its approach to equity, diversity and inclusion. Meanwhile, the Vancouver PuSh Festival was in hot water for firing two women of colour during pandemic cutbacks, which raised the ire of the artistic community at a time when systemic racism was the main topic of conversation.

After both boards eventually resigned, community insiders reflected on what went wrong. One exiting Buddies board member

PEU APRÈS L’APPARITION DE LA COVID-19 en 2020, deux compagnies de théâtre ont vécu des crises publiques. À Toronto, le théâtre Buddies in Bad Times – la plus importante et plus ancienne compagnie de théâtre queer au monde – fut entraîné dans un conflit entre le personnel et le conseil d’administration sur son orientation et son approche à l’égard de l’équité, de la diversité et de l’inclusion. Par ailleurs, le festival PuSh de Vancouver s’est placé dans l’eau chaude en congédiant deux femmes de couleur dans le cadre d’une réduction de personnel due à la pandémie, provoquant l’ire de la communauté artistique au moment où le racisme systémique était sur toutes les lèvres.

told the Toronto Star the board was “lagging behind the important changes happening on stage and behind the scenes,” while in The Globe and Mail, a playwright mused that PuSh’s problems arose from “a corporate [board] structure that has few tools at its disposal to handle complicated situations or conversations” in the arts.

Evalyn Parry had a few thoughts of her own. The former artistic director at Buddies stepped down in September 2020 to care for her sick partner, but also because it was time for change. Following the board’s resignation in 2022, she told the Toronto Star that the not-for-profit governance structure is an “antiquated, colonial structure that serves to keep the status quo in place, even and especially within the arts.”

But today, Parry is encouraged by conversations around arts governance and a perceived appetite for change.

“The pandemic shone such a light on needing to find new ways to fix a broken system,” Parry told Director Journal. “To continue to default to how things have been done was not good enough any more, and I feel like collectively we’ve opened our eyes to this not being sufficient.”

In a blog post, Yvette Nolan, a playwright, writes about four fundamental problems with governance in the arts: a corporate board structure that is incompatible with the purpose of art; board members who are not personally connected to the arts; a board that doesn’t understand its oversight role, which can lead to problems such as micromanaging or indifference; and the volunteer nature of the job, which leaves insufficient time for proper governance. After 25 years of theatre work, Nolan, who has served on arts boards and researched governance models, is convinced the board of directors is “actually a fiction.”

The root cause of the problem is scarce resources in the arts. In general, art’s worth in society is undervalued, Parry says. A Statistics Canada survey finds nearly 60 per cent of artists earned less than $40,000 annually in 2019, with a high degree of income volatility. The precarious nature of the work in a sector with few leadership positions, coupled with the assumption that artists can’t manage money, creates inequity around decision making, says Parry.

“You essentially have a structure where people who are your boss – the [board] that hires and fires and oversees and supports, or doesn’t support, the leaders of arts organizations – are not experts in the arts,” Parry says. “They’re experts in money, which fundamentally creates a tricky set of dynamics that feels very hierarchical and paternalistic.”

To incorporate, have a board of directors and be a legal entity is, in many ways, incompatible with the nature of art, theatre advocates say. “Is that what an artist aspires to?” Parry says. “It’s antithetical to so many of the impulses behind art to be ruled by a corporate structure.”

These rules also mean artists and their organizations spend valuable time and money conforming to structures and ticking boxes to satisfy governments. A better approach would be to empower theatres to design governance structures that make sense for them. But what that structure looks like, Parry says, “is the million-dollar question.”

Après la démission des deux conseils, des gens du milieu se sont penchés sur les causes de ces crises. Un membre sortant du conseil de Buddies a déclaré au Toronto Star que le conseil « avait pris du retard sur les changements importants survenus sur scène et en coulisses », alors que dans le Globe and Mail, un dramaturge s’est dit d’avis que les problèmes de PuSh provenaient « d’une structure de gouvernance qui a peu d’outils à sa disposition pour gérer des situations complexes ».

Evalyn Parry a ses idées sur la question. L’ancienne directrice artistique de Buddies a démissionné en septembre 2020 pour s’occuper de son épouse malade, mais aussi parce qu’il était temps de changer. Après la démission du conseil en 2022, elle a déclaré au Toronto Star que la structure de gouvernance des organismes à but non lucratif est « désuète et coloniale et ne sert qu’à maintenir le statu quo, particulièrement dans le domaine des arts ».

Mais aujourd’hui, Mme Parry est encouragée par ce qu’elle perçoit comme un désir de changement.

« La pandémie a jeté un éclairage sur la nécessité de trouver de nouveaux moyens de redresser un système brisé, a-t-elle dit au Director Journal. Nous avons collectivement ouvert les yeux sur les insuffisances de ce système. »

La dramaturge Yvette Nolan a décrit dans un blogue les quatre problèmes fondamentaux de la gouvernance des arts : une structure incompatible avec l’objectif de l’art; des administrateurs qui ne sont pas liés personnellement aux arts; un conseil qui ne comprend pas son rôle de surveillance, ce qui peut mener à des problèmes comme la micro-gestion ou l’indifférence; et la nature bénévole de la tâche, qui ne laisse pas suffisamment de temps pour exercer une gouvernance appropriée. Après 25 ans dans le monde du théâtre, Mme Nolan, est convaincue que le conseil d’administration est, « dans les faits, une fiction ».

La cause principale du problème est la rareté des ressources dans le domaine des arts. En général, l’art dans la société est sous-évalué, affirme Mme Parry. Une enquête de Statistique Canada indique que près de 60 pour cent des artistes gagnaient moins de 40 000 $ en 2019. Associé au préjugé selon lequel les artistes ne savent pas gérer l’argent, le travail précaire dans un secteur offrant peu de postes de leadership crée de l’iniquité dans la prise de décision.

« Essentiellement, voilà une structure où nos patrons ne sont pas des experts en art, explique Mme Parry. Ce sont des experts en argent, ce qui crée une dynamique compliquée, très hiérarchique et paternaliste. »

S’incorporer, avoir un conseil d’administration et former une entité juridique est, à bien des égards, incompatible avec la nature de l’art, soutient Mme Parry. « Est-ce qu’un artiste aspire à être gouverné par une structure organisationnelle? Au contraire. »

Ces règles signifient que les artistes et leurs organisations passent un temps précieux et dépensent de l’argent à se conformer à des structures et à cocher des cases pour satisfaire les gouvernements. Une meilleure approche consisterait à habiliter les théâtres à concevoir les structures de gouvernance qui leur conviennent.

Jane Marsland has been grappling with this question for decades. An award-winning arts advocate and administrator, Marsland served on several arts boards in the late 1990s and early 2000s, including the Harbourfront Centre, Necessary Angel Theatre Co., and the Toronto Alliance for the Performing Arts. She was also a member of the transition board for 12 Alexander Street as it became the permanent home of Buddies in Bad Times Theatre.

But today, she refuses to serve on boards. Marsland, now an arts consultant, observes that volunteers who join arts boards are not properly briefed to understand the role of individual directors or the board, the culture of the organization, and why and for whom it exists. She faults the organization’s leadership – not the board – for this lack of understanding.

Management must be clear about the organization, its purpose and why it’s courting candidates. Sometimes, cash-strapped organizations will “lure somebody unsuspecting” to the board because they want access to that individual’s connections to wealth, Marsland says. But if they aren’t honest about their motivations, it can create tension.

Other times, management entices what Marsland calls a slot board.

“So they go, ‘We need a banker, and a lawyer, and we need this and this and this’,” Marsland says. “But it’s completely divorced

Jane Marsland se penche sur cette question depuis des décennies. Promotrice et administratrice du domaine des arts et récipiendaire de plusieurs prix, elle a siégé à de nombreux conseils d’organisations artistiques, dont le Harbourfront Centre, le Necessary Angel Theatre et la Toronto Alliance for the Performing Arts. Elle a aussi siégé au conseil de transition du 12 Alexander Street lorsque cette adresse est devenue le domicile permanent du théâtre Buddies in Bad Times.

Mais aujourd’hui, elle refuse de siéger à des conseils. Maintenant consultante, Mme Marsland observe que les bénévoles qui joignent un conseil dans le secteur des arts ne sont pas convenablement formés pour comprendre leur rôle, la culture de l’organisation et les raisons de son existence. Elle attribue ce manque de compréhension au leadership de l’organisation, non au conseil.

La direction doit être claire sur la nature de l’organisation, ses objectifs et les raisons pour lesquelles elle recherche des candidats. Parfois, des organisations à court de fonds vont tenter « d’attirer des gens peu méfiants » au conseil afin d’avoir accès au réseau financier de cette personne, explique Mme Marsland.

À d’autres moments, la direction tentera de nommer un conseil strictement pour la forme.

« Ensuite, ils ont besoin d’un banquier, puis d’un avocat et de

[from] what is the work we’re doing, why are we doing it and who’s interested in the work? Because it’s an arts organization, its only purpose is the art.”

However, bankers and lawyers come from sectors with different values. They often operate within hierarchies as opposed to the collaborative processes that artists use. And they don’t necessarily visit the studio to see how artists work or identify whether abusive processes exist.

“There’s a deep disconnect and misunderstanding between the board and the volunteers, and the processes and values of the artists and the arts organization,” Marsland says. “That’s where the dysfunction sets in … [and] the time and energy that gets sucked out of the organization is dramatic.”

In Marsland’s view, the perfect board member understands “the purpose of art is to wake the public up.” But there are two types of people – those who want their beliefs confirmed and those who welcome challenge. The people who “do not want to be shook up” may not be a good fit for boards of contemporary arts companies, Marsland says.