Director Journal

EXECUTIVE DECISION

It’s always the right time to plan for a new CEO

It’s always the right time to plan for a new CEO

EDITOR

Simon Avery

ART DIRECTOR

Lionel Bebbington

CONTRIBUTORS

Jeff Buckstein, Louise Taylor Green, Zabeen Hirji, Benjamin Nycum, Gordon Pitts, Serge Rivest, Barbara Smith, Prasanthi Vasanthakumar, Shirley Won

Prasanthi Vasanthakumar

Rahul Bhardwaj - President and CEO

Richard Piticco - Chief administrative officer

Jan Daly Mollenhauer - Vice-president, sales, marketing and membership

Gigi Dawe - Vice-president, policy and research

Kathryn Wakefield - Vice-president, chapter relations

Eric Schneider - President

Abi Slone - Creative director

Dana Francoz - Advertising sales dana.francoz@finallycontent.com

416-726-2853

The board’s most important job

Rahul Bhardwaj on developing Canada’s competitive advantage

Futurist Tom Cruise, cancelled meetings, Threads vs Twitter, the high cost of heat waves, and executive unease

It’s now or never on climate change

How can organizations build corporate culture in a hybrid-work world?

Recent board appointments across the country

Island of interest

Building trust and confidence in Canadian organizations is imperative. At the Institute of Corporate Directors (ICD), we believe that this starts with the right leadership and good governance. Directors must lead by being informed, prepared, ethical, connected, courageous and engaged with the world. In the pages that follow, you will find thoughtful and provocative articles that explore these essential leadership qualities. Bâtir la confiance envers les organisations can- adiennes est primordial. À l’Institut des administrateurs de sociétés (IAS), nous croyons que cela commence par un bon leadership et une bonne gouvernance. Les administrateurs doivent gouverner en étant informés, préparés, intègres, connectés, courageux et ouverts sur le monde. Dans les pages qui suivent, vous trouverez des articles réfléchis et provocateurs qui explorent ces qualités de leadership essentielles.

2701 – 250 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario M5B 2L7

T: 416-593-7741 F: 416-593-0636 E: info@icd.ca

ISSN 2371-5634 (Print)

www.icd.ca

ISSN 2371-5650 (Online)

The ICD welcomes a diversity of opinion for inclusion in Director Journal. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the ICD, its partners, its sponsors, or its advertisers. Readers are encouraged to consider seeking professional advice and other views. To request reprints of articles, please contact info@icd.ca

In his wholesale restructuring of Economical Insurance, chair John Bowey showed that the board can lead change and challenge management

Rooting out racism and other forms of oppression requires boards to take a hard look at themselves, a soul-searching director has learned

Love or hate your CEO, you need a succession plan

High interest rates make it harder to decide how to spend capital

In Canada and Climate Change, academic William Leiss takes the country to task for not meeting its commitments and offers a small-scale solution

WHETHER THE ISSUE is CEO succession, reputational risk or capital allocation, boards today are finding they need to give greater attention to a wider range of subjects.

One of those is leadership. CEO turnover is occurring at the fastest pace in years, driven in part by the effects of the pandemic, fears of a recession, and technological change. It’s not enough for boards to be aware of the trend –they need to have a succession plan in place, regardless of the quality and age of the current CEO. In our cover story “Executive decision,” Prasanthi Vasanthakumar talks to directors and talent and recruitment experts about the do’s and don’ts of succession planning, which include being crystal clear about the essential skills a candidate must have, and not limiting your search to those who are already CEOs.

Simon Avery Editor savery@icd.caOne of the most surprising reputational crises in Canada occurred three years ago at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights when former employees went public with complaints about racism and homophobia. Management and the board were caught completely off guard – this was an organization after all that was founded to champion justice and equity. Today, the crisis may have been handled, but for director Benjamin Nycum, the journey continues. In his article “The right to be heard” on page 22, he talks about shortcomings in the way boards govern and how they added to the museum’s troubles.

“We learned that typical, robust and even exemplary governance can create blinders,” he writes. “Insightful leaders need to understand that signs of trouble may present themselves in a subtle manner and may not be issues typically discussed at a board meeting. As board members, we need to be probing for these signs.”

With the runup in interest rates over the past year, companies are paying more to raise capital. In “Rising to the interest rate challenge” (page 40), Jeff Buckstein looks at some of the factors boards should consider before signing off on the allocation of capital, including the possibility that rates will keep going up.

All three of these stories, as well as Gordon Pitts’ profile of ICD Fellow John Bowey (page 16), illustrate how important it is for the board to be leading change to help the organization thrive. DJ

QU’IL S’AGISSE de succession du chef de la direction, de risque réputationnel ou d’affectation de capitaux, les conseils doivent aujour d’hui accorder plus d’attention à tout un éventail de questions. L’une d’entre elles est le leadership. Le roulement des chefs de la direction se produit à un rythme plus effréné que jamais, sous les effets de la pandémie, de la crainte d’une récession et des changements technologiques. Il ne suffit pas pour les conseils d’être au fait de cette tendance; ils doivent aussi avoir un plan de succession, sans égard à la qualité et à l’âge du chef de la direction actuel. Dans notre article principal, Prasanthi Vasanthakumar s’entretient avec des administrateurs et des experts du recrutement au sujet des choses à faire et à ne pas faire en matière de planification de la succession.

L’une des plus étonnantes crises réputationnelles au Canada s’est produite il y a trois ans au Musée canadien pour les droits de la personne, lorsque d’anciens employés ont formulé publiquement des plaintes de racisme et d’homophobie. La direction et le conseil ont été pris complètement au dépourvu. Aujourd’hui, la crise paraît résolue, mais pour l’administrateur Benjamin Nycum, le parcours se poursuit. Dans son article « Le droit d’être entendu », en page 22, il évoque les obstacles qui se dressent devant la gouvernance et explique comment ceux-ci se sont ajoutés aux difficultés du musée.

« Nous avons appris qu’une gouvernance représentative, robuste et exemplaire peut créer des œillères, écrit-il. »

Avec la hausse des taux d’intérêts au cours de la dernière année, les entreprises paient davantage pour obtenir des capitaux. Dans l’article « Rising to the interest rate challenge » (en anglais seulement, page 40), Jeff Buckstein examine certains facteurs que les conseils devraient considérer avant d’autoriser une affectation de capitaux.

Ces trois articles – tout comme le portrait du Fellow de l’IAS John Bowey par Gordon Pitts (page 16) – montrent à quel point il est important pour les conseils de mener le changement pour aider leurs organisations à prospérer. DJ

WITH THE PANDEMIC still fresh in our minds, it’s worth drawing attention to the huge success of our national conference in Montreal, which brought together almost 1,000 attendees, renewing a sense of community among directors right across the country.

Held in mid-June, the event included insightful keynotes and breakout sessions featuring internationally acclaimed speakers and governance experts. These included Rana Foroohar, CNN’s global economic analyst; Gillian Tett, chair of the editorial board at the Financial Times; and Geneviève Fortier, CEO of Promutuel Insurance.

Noubar Afeyan, the Canadian co-founder and chair of Moderna Inc., headlined the stellar Fellowship Awards Gala. He drew numerous standing ovations as he mesmerized the audience with his tale of corporate leadership during the darkest days of Covid-19, when world governments lined up for the company’s breakthrough vaccine.

Rahul Bhardwaj LL.B, ICD.D President and CEO, The Institute of Corporate DirectorsThe event provided a chance to reflect on the strong foundation of Canadian corporate leadership and governance, and the community’s commitment to continuous improvement – themes that this issue of Director Journal expands upon.

For me, personally, the conference reinforced how the calibre of leadership and strength of culture in this country has the potential to make corporate governance Canada’s global competitive advantage. With so much uncertainty today, there is no better time to promote this edge as an essential part of Canada’s brand. These are highly valuable characteristics that build trust in many ways, helping to support Canadian businesses and institutions around the world.

This competitive advantage also underpins the ICD’s mission to support better boards, making better decisions to build a better Canada. We are committed to expanding the capability of all our members and the corporate governance ecosystem through our chapter events, courses and other projects. They are current, innovative and, at times, they push the boundaries. So, as we ramp up for a busy fall season, I encourage you to come out to some of our events, sign up for a webinar, or take a course – and get ready to be challenged. DJ

AVEC LA PANDÉMIE toujours présente à notre esprit, il vaut la peine d’attirer l’attention sur l’immense succès de notre congrès national tenu à Montréal, lequel a réuni presque 1 000 participants, suscitant un sens renouvelé de la communauté chez nos administrateurs.

Tenu à la mi-juin, l’événement a comporté des allocutions inspirées et des séances de groupe réunissant des conférenciers et spécialistes de la gouvernance mondialement reconnus. Pensons à Rana Foroohar, l’analyste de l’économie mondiale de CNN, Gillian Tett, présidente du conseil éditorial du Financial Times, et enfin à Geneviève Fortier, cheffe de la direction de Promutuel Assurance.

Noubar Afeyan, le cofondateur canadien et président du conseil de Moderna Inc., a été la vedette du Gala des Fellows, suscitant plusieurs ovations debout en médusant l’auditoire avec ses histoires de leadership corporatif durant les jours les plus sombres de la Covid-19, alors que les gouvernements faisaient la file pour obtenir le vaccin révolutionnaire de l’entreprise.

Le congrès a permis de constater le solide fondement du leadership et de la gouvernance des organisations canadiennes et l’engagement de la communauté envers l’amélioration continue.

Il a renforcé mon sentiment que le calibre de leadership et la force de la culture en ce pays offrent un avantage concurrentiel mondial à la gouvernance canadienne. En ces temps incertains, c’est le moment de promouvoir cet avantage comme élément essentiel de la marque canadienne.

Cela s’appuie sur la mission de l’IAS de soutenir les meilleurs conseils, de les aider à prendre les meilleures décisions afin de bâtir un Canada meilleur. Nous sommes engagés à élargir les capacités de nos membres au moyen des événements de nos sections régionales, de nos formations et d’autres projets. Nos contenus –comme les idées et perspectives de nos membres au sein de nos forums – sont constamment actualisés. Ils sont modernes, innovants et parfois repoussent les limites. Au moment où nous amorçons un automne chargé, je vous invite à fréquenter nos événements, à participer à nos webinaires ou à suivre nos cours. Soyez prêts à relever les défis. DJ

ALTHOUGH HIS DEATH-DEFYING antics in Mission: Impossible –Dead Reckoning Part One don’t translate to our everyday reality, Tom Cruise is warning us about the very real threats of technology. In his latest instalment of the spyaction franchise, Cruise predictably jumps off a cliff and fights villains atop a moving train, but he’s also battling “The Entity,” a supersmart AI that’s out to eradicate humanity.

Indeed, artificial intelligence is the threat and opportunity of the day. A new report from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) finds that our digital doppelgangers could replace 27 per cent of jobs in the world’s wealthiest countries. Even Hollywood is worried: A-listers are on strike partly because AIgenerated images could foreseeably replace actors.

For now, however, fans can take heart that Cruise’s elaborate plot twists haven’t yet materialized. But there are some eerie similarities between earlier films from the franchise and real life, reports Quartz. For example, the first film in the series, “Mission: Impossible,” came out in 1996 and centred on a cyberattack that exposed the CIA’s list of undercover agents. Today, cybercrime is expected to cost the world US$10.5-trillion annually by 2025.

Shopify wants employees to think long and hard before they schedule their next meeting. This is why the Ottawa-based tech giant embedded a calculator in staff calendars this summer. Using average compensation data, event duration and participant count, the calculator puts a price tag on any meeting with three or more attendees, reports Bloomberg.

For some employees, a day without meetings may raise disturbing questions: How do I look like I’m working? Where can I show off? Or talk about my feelings?

But for most workers, meetings are a drag. And for Shopify, they are a drag on productivity. Earlier this year, the company launched a full-on assault on unnecessary meetings to improve efficiency: It nixed all recurring meetings with more than two people and discouraged meetings on Wednesdays.

“No one joined Shopify to sit in meetings,” a company spokesperson told CBC. True, but is the no-meet policy working?

Not according to one former Shopify employee who spoke to CBC. Instead of running fewer meetings, people just learned how to be sneaky about them.

Organizational psychologist Steven Rogelberg agrees the Shopify calculator alone won’t change behaviour. Getting better at meetings isn’t a quick fix, he tells CBC’s Cost of Living show.

Kaz Nejatian would likely concur. The Shopify executive and builder of the meeting calculator thinks most of the modern work environment is broken. “It’s not just any one change that matters,” he says in Bloomberg.

It all began with some social media smack talk. Earlier this summer, Elon Musk tweeted that he would be “up for a cage match” with long-time rival Mark Zuckerberg. The Meta chief responded, “Send me the location.” The billionaires are yet to brawl, but the feud between Twitter [now named X] and Threads is on.

Zuckerberg’s Threads is the latest copycat app looking to capitalize on Twitter’s bad behaviour. Within hours of its launch in July, 10 million users signed up. Threads is the fastest-growing app in history, but does it have staying power?

Rebecca Jennings at Vox doesn’t think so. While Threads allows users to automatically transfer their Instagram following, many of these accounts are brands and influencers who won’t make you laugh. And that’s the beauty of Twitter: Users just want to read random and hilarious musings from anonymous people interspersed with serious news and views.

As Threads works out its kinks and Twitter continues to self-destruct, a clear victor may emerge by the time of publication. But are we looking at this the wrong way? As professor Angela Misri writes in The Walrus, these tech tycoons are not in the business of friendship. What they want is your data so they can sell you stuff. So instead of chasing our next digital hit, maybe we should quit social media and just meet friends in real life.

Earlier this year, consulting firm McKinsey asked the world’s top CEOs what trends will most affect how they lead in 2023. Here’s what they said:

The “Russian Davos” is the party no one wants to attend. In fact, an invitation to the annual St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) is “totally toxic,” one former attendee tells The Guardian.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Western companies have shunned the Davos wannabe, headlined by Russian President Vladimir Putin. With the event’s prestige taking a hit and networking opportunities vanishing, even Russians haven’t been keen to attend. The country’s largest tech company and other prominent businesspeople were reportedly noshows at the forum held in June.

“They think it’s useless and expensive,” Alexandra Prokopenko said in The Guardian. The former central bank official said the skyrocketing admission fees and travel to St. Petersburg aren’t worth it for many companies.

The forum wasn’t always this uncool. Before 2014 – and Russia’s annexation of Crimea – multinationals and Russian companies jockeyed for expensive partnerships and threw glitzy parties with pop stars such as Sting. There was a time when people cared about pleasing Putin.

To make up for the lack of Western interest this year, Russia courted delegations from the Middle East, India and China. One state financial official admitted things are different, but called the atmosphere “normal, not very depressing.”

Despite organizers’ best efforts, many believe the forum has become an exercise in selfdelusion, reports The Guardian. Indeed, the Kremlin’s official website claims “SPIEF has gained the status of the world’s leading platform for discussing key issues on the global economic agenda.”

It was another scorching and smoky summer in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere. Canada had its worst wildfire season on record. Tourist meccas like Spain, Greece and Italy urged travellers to stay indoors, imperilling the future of summer sightseeing. And in Northwest China, temperatures hit 52 C. The economic fallout of this extreme heat will increase with time, reports The New York Times. According to analysts at Barclays, the cost of each climate-related disaster has jumped by nearly 77 per cent in the past five decades.

THE TEMPERATURE TOLL

Extreme heat is getting expensive. Here’s how it’s costing the economy:

The ICD-Rotman Directors Education Program is the leading educational program for experienced board directors seeking to advance their contributions to Canada’s boardrooms and beyond.

A joint initiative of ICD and Rotman, this comprehensive program offers both a national and local perspective, through leading business schools across Canada. With the goal of building competencies deemed necessary to be an effective director in today’s challenging world, the DEP provides insight from both an academic and real-world, director lens perspective. Course participants benefit from the rich experience of their peers in navigating their role within complex board dynamics. Completion of the DEP and success in the ICD led examination process, leads to the highly recognized ICD.D designation, within a one-year timeframe.

Interested experienced directors are encouraged to submit their application to the ICD, along with references, for consideration into the program.

APPLY ONLINE EDUCATION.ICD.CA/DEP24

Call 416.593.3325 or email education@icd.ca for a personal consultation.

UPCOMING DEP START DATES

TORONTO October 2, 2023

WINNIPEG October 12, 2023

ONLINE October 16, 2023

CALGARY October 26, 2023

HALIFAX November 16, 2023

VANCOUVER January 15, 2024

MONTREAL April 19, 2024

Application process is now open and is subject to availability. Application deadlines are 4-6 weeks before the class start date.

BY Simon Avery‘EARTH JUST HAD ITS HOTTEST MONTH EVER,’ The Wall Street Journal reported in August. In fact, it’s been a year of records – the worst kind.

The past eight years have been the warmest ever recorded, ocean surface temperatures hit a new high last spring, the pace of rising sea levels is the fastest we’ve known, and the volume of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere continues to scale new heights. The list of noteworthy data points is long, but one in particular stands out: World oil demand is reaching record highs.

This year demand will increase by 2.2 million barrels a day to 102.2 million barrels daily, spurred by air travel, greater use of oil in power generation and surging Chinese petrochemical activity, says the International Energy Agency. Next year will see demand rise by a further million barrels a day, the IEA forecasts. The extra combustion will spew even greater amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Last year, carbon dioxide emissions from oil rose 2.5 per cent and overall energy-related emissions grew by 0.9 per cent, reaching a record of more than 36.8 billion tonnes, the IEA reports.

Without green sources of power such as hydro, solar and wind, last year’s increase in CO2 emissions would have been nearly three times as high, the IEA says. The European Union, where the sale of gas and diesel cars has been banned from 2035, is a leading force when it comes to clean energy. Last year, for the first time in the EU, combined electricity generation from wind and solar exceeded that of gas or nuclear, and the bloc’s emissions decreased by 2.5 per cent – a trend that continued in the first quarter of this year.

But IEA data show that other regions of the world aren’t doing their part. China’s emissions were relatively flat through the year (at a time when most of the country was still constrained by Covid-19), but U.S. emissions increased by 0.8 per cent, and developing economies in Asia emitted 4.2 per cent more.

With demand so strong, some major oil and gas companies have reversed course on plans to reduce output. Dividends, not clean energy, are the new focus. In 2012, the industry allocated 90 per cent of its cash for capital expenditures and 10 per cent for dividends and share buybacks. In 2022, the breakdown was 48 per cent for capex, 39 per cent for shareholders, 13 per cent on debt repayments and 1 per cent for investing in low-carbon projects, according to IEA data.

“We still see emissions growing from fossil fuels, hindering efforts to meet the world’s climate targets,” says Fatih Birol, the executive director of the IEA. “International and national fossil fuel

companies are making record revenues and need to take their share of responsibility, in line with their public pledges to meet climate goals. It’s critical that they review their strategies to make sure they’re aligned with meaningful emissions reductions.”

In November, governments meet in Dubai for the COP28 climate talks, likely their last chance to get on track to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. There’s a lot of work to be done by all of us. DJ

Based on their spending patterns, major oil companies appear much more interested in paying shareholders than investing in clean energy.

• What communication tactics are working or need to change to sustain organizational alignment and leader visibility?

• What evidence do we have that those at the top are role models of ethics, values and behaviour? Is there evidence of misalignment at any level?

HYBRID WORK IS HERE TO STAY and, like it or not, that means boards and leadership teams need to reflect on the culture required to thrive in this new reality. It simply won’t do to “lift and shift” the in-office cultural norms to hybrid. Now, with the benefit of three years of new knowledge following the pandemic and a clear view that hybrid is a modern workplace standard, organizations have a spectacular opportunity to reimagine culture.

For many senior leaders and directors, there is a prevailing sense of loss, some may even say grieving, over the forfeiture of fully in-person workplaces. Despite the complexities and normal resistance to change, intentional culture redesign is an unparalleled opportunity to elevate leadership practices and behaviours, social norms and work design.

Boards need to co-create governance practices for culture with management to ensure clarity over reporting and monitoring. Board committee mandates should be examined to determine which elements of the culture are monitored by each committee.

Before building a new hybrid culture, boards and management need to fully understand the current culture by asking:

• What is it and how is it being objectively measured?

• How are in-office, remote and hybrid employees experiencing the culture – what are the similarities and differences?

• Do leaders have accountabilities and rewards specifically related to their behaviour?

Boards and management teams are continuously examining the sources of value creation, such as strategy, brand, innovation and intellectual property, but culture and talent are important intangible assets that foster a competitive advantage. The ideal culture should be co-created with the board and management, considering the organization’s purpose, vision and values. Employees should have a say too, through surveys, focus groups and direct dialogue with leaders. Some points to focus on include:

• What kind of culture do we need to meet our business objectives?

• What new types of behaviour need to be learned?

• What must be done to embrace hybrid fundamentals (for instance, collaboration tools, workload management, access to leadership, decision making, problem solving)?

• What managerial practices need to change to maintain or increase productivity?

• What capabilities do supervisors and leaders need to lead, coach and manage performance?

Once the ideal culture has been defined, focus on changing behaviour first; mindsets will eventually follow. One of the most effective ways to reduce risks associated with talent and an organization’s culture is to ensure intentional design and continuous monitoring and dialogue, making it a top priority for progressive boards.

LOUISE TAYLOR GREEN, ICD.D., serves on the boards of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Toronto Metropolitan University, Blu Ivy Group, and the Institute of Certified Management Consultants of Ontario. She is also a director and past chair of the Hamilton Health Sciences Volunteer Association and has led numerous culture transformations, most recently as CEO of the Human Resources Professionals Association and chief human resources officer of Economical Insurance.

LE TRAVAIL HYBRIDE est là pour rester, que ça nous plaise ou non. Les conseils et les équipes de direction doivent donc réfléchir à la culture requise pour prospérer dans cette nouvelle réalité. Il ne suffira pas de simplement transférer en mode hybride les normes culturelles applicables au travail de bureau. Misant sur trois années de nouveau savoir à la suite de la pandémie et sur une vision claire de ce que représente le travail hybride, les organisations ont une occasion en or de repenser leur culture.

Beaucoup de leaders et d’administrateurs d’expérience en éprouvent du chagrin. Certains peuvent même évoquer un sentiment de deuil. Malgré les complexités et une résistance normale au changement, cette nouvelle culture représente une occasion sans précédent d’élever les pratiques et comportements liés au leadership, aux normes sociales et à la conception du travail.

Les conseils doivent créer avec leurs équipes de direction de nouvelles pratiques de gouvernance afin d’assurer la clarté de leurs rapports financiers et de leur mandat de surveillance. Les mandats des comités du conseil devraient faire l’objet d’examens afin de déterminer quels éléments de la culture d’entreprise sont pris en main par chacun d’entre eux.

Avant de bâtir une nouvelle culture hybride, les conseils et leurs directions doivent comprendre à fond la culture en cours en posant les questions suivantes.

• Quelle est cette culture et comment la mesure-t-on objectivement?

• Comment les employés en présentiel, en télétravail et en mode hybride vivent-ils cette culture? Quelles en sont les similarités et les différences?

• Les leaders ont-ils des comptes à rendre et des rétributions spécifiquement reliés à leur comportement?

• Quelles tactiques de communication fonctionnent et lesquelles doivent changer pour soutenir l’alignement organisationnel et la visibilité du leader?

• Quelles preuves avons-nous que les gens au sommet sont des modèles en matière d’éthique, de valeurs et de comportement?

Y a-t-il des preuves de désalignement à quelque niveau?

Les conseils et les équipes de direction examinent continuellement les sources de création de valeur telles que la stratégie, la marque, l’innovation et la propriété intellectuelle. Mais la culture et le talent sont des actifs intangibles importants qui offrent un avantage concurrentiel. La culture idéale devrait être créée par le conseil et la direction, en tenant compte des objectifs, de la vision et des valeurs de l’organisation. Les employés devraient aussi avoir leur mot à dire. Voici certains éléments à considérer.

• Quel type de culture faut-il pour atteindre nos objectifs?

• Quels nouveaux types de comportement devons-nous adopter?

• Que faut-il faire pour intégrer les éléments fondamentaux d’une culture hybride (outils de collaboration, gestion de la charge de travail, accès au leadership, prise de décision, résolution de problèmes)?

• Quelles pratiques de gestion doivent changer pour maintenir ou accroître la productivité?

• Quelles compétences doivent posséder les leaders pour gérer la performance?

Une fois définie la culture idéale, concentrez-vous d’abord sur le changement de comportement. L’une des façons les plus efficaces de réduire les risques associés au talent et à la culture d’une organisation consiste à adopter un modèle intentionnel ainsi qu’un suivi et un dialogue continus.

LOUISE TAYLOR GREEN, IAS.A, siège aux conseils de l’Agence des médicaments et des technologies de la santé au Canada, de l’Université métropolitaine de Toronto, du Groupe Blue Ivy et de l’Institut des conseillers certifiés en management de l’Ontario.

PROVIDING OVERSIGHT for culture is an iterative and integrative process for boards, and with more people now working partly from home and partly from the office, it’s important that directors consider new issues arising from the hybrid model.

In the big picture, culture is a set of values, mindsets and sorts of behaviour that shape how work gets done and decisions are made. It is how employees act when no one is looking. Providing oversight of culture starts with a clear understanding of the organization’s current culture as well as the target culture. In larger organizations, one size doesn’t fit all and there are often various subcultures at play.

As today’s boards find themselves responsible for overseeing both culture and the hybrid workspace, they should be asking themselves three important questions:

• What culture themes are most important in their hybrid environment? Examples include collaboration, creativity and innovation, learning, and values and ethics.

• What is the leadership team doing to manage this culture?

• How are they measuring it, making adjustments, and sharing their findings with the board?

To help answer these questions, it’s helpful for directors to learn from what other organizations are doing. Examples of good practices include:

• Creating onboarding programs for new employees with culture infused, including periodic touchpoints, ideally occurring in person. This is a critical step in helping new employees engage, be productive and adhere to the organization’s values.

• Listening to and learning from the multigenerational workforce. Organizations should understand the realities and aspirations of their new workers, and test and refine ideas before driving change. This builds trust and avoids making choices based on leaders’ biases and assumptions.

• Mentoring and coaching younger employees to accelerate their learning and increase retention. The process should include meaningful in-person social connections and collaboration.

Some of the most promising practices bridge the new environment with the traditional. Find ways, for instance, to leverage the effect of “culture carriers,” who are both leaders and employees with a strong presence in the office and online. They connect and influence colleagues through online channels, by talking on the phone, sharing stories on social media, and modelling the desired behaviours of the organization.

Keep in mind that creativity and innovation are sparked both within

and across teams, and the process cannot always be planned. Serendipitous interactions are critical, as good ideas come from everywhere, and organizations need to create the environments to allow them to happen. And ensure that productivity is a shared goal and mutual effort, as this will build trust and the foundation for a strong culture.

ZABEEN HIRJI, ICD.D, serves on the board of Sleep Country Canada, where she chairs the human resources committee. She also serves as a director on the board of the Public Policy Forum and on the Junior Achievement Worldwide board of governors. She is executive advisor on the future of work at Deloitte and was formerly the chief human resources officer at Royal Bank of Canada. DJ

LA SUPERVISION de la culture est un processus axé sur la répétition et l’intégration. De plus en plus de gens travaillent en mode hybride et il est important pour les administrateurs d’examiner les nouveaux enjeux issus de ce modèle.

La culture est un ensemble de valeurs, de façons de penser et de comportements qui déterminent la manière de travailler et la prise de décision. C’est la façon dont les employés agissent quand personne ne regarde. La supervision de la culture commence avec une compréhension claire de la culture actuelle et de celle qu’on entend créer. Chez les grandes organisations, il n’y a pas d’approche uniforme alors que diverses sous-cultures sont en jeu.

À cet égard, les conseils doivent se poser trois questions importantes.

• Quels sont les thèmes culturels les plus importants dans un environnement hybride?

• Que fait l’équipe de direction pour gérer cette culture?

• Comment la mesure-t-elle, opère-t-elle les ajustements et partage-t-elle ses observations avec le conseil?

Pour répondre à ces questions, les administrateurs peuvent apprendre d’autres organisations. Voici quelques exemples de bonnes pratiques.

• Créer des programmes d’intégration pour les nouveaux employés afin qu’ils s’imprègnent de la culture de l’organisation.

• Le mentorat et le coaching des jeunes employés accélèrent leur apprentissage et accroissent leur fidélité.

Certaines des pratiques les plus prometteuses relient le nouvel environnement à l’ancien. Trouvez des moyens de miser sur l’effet des « porteurs de culture » qui sont à la fois des cadres et des employés avec une forte présence au bureau et en ligne. Ils créent des liens et influencent leurs collègues, favorisant des comportements qui profitent à l’organisation.

Gardez à l’esprit que la créativité et l’innovation sont stimulées à la fois au sein des équipes et entre elles et ce processus ne peut pas toujours être planifié. DJ

ZABEEN HIRJI, IAS.A, siège au conseil de Sleep Country Canada, dont elle préside le comité des ressources humaines. Elle siège aussi au conseil du Forum des politiques publiques et au conseil des gouverneurs du Junior Achievement Award. Elle est conseillère exécutive sur l’avenir du travail chez Deloitte et fut aussi cheffe des ressources humaines à la Banque Royale du Canada.

Sponsored by:

BOARD FUNDAMENTALS

HUMAN RESOURCE & COMPENSATION COMMITTEE EFFECTIVENESS.

OPTIMIZE THE BOARD’S UNDERSTANDING OF HUMAN CAPITAL OVERSIGHT

Understand the considerations of talent management, CEO, succession planning and executive compensation, as well as increased scrutiny of these issues by stakeholders.

ONLINE December 13, 2023

APPLY BY: November 22, 2023

As a director, your learning journey is never over. ICD courses are developed for directors, by directors and offer a personalized and interactive learning experience through engaged live instructor-led sessions, and a dynamic alumni portal to stay connected with your director peers for continued learning and support. Those that have taken the ICD-Rotman Directors Education Program keep their skills sharp and up-to-date by earning continuing education units (CEUs) with each developed course they take.

ISSUES OVERSIGHT

OVERSIGHT OF CYBERSECURITY IN AN ERA OF DIGITAL ACCELERATION.

THE ROLE OF THE BOARD IN CYBER RESILIENCE

Develop greater insight and understanding of cybersecurity risks in an age of rapid technological advancements.

ONLINE October 31, 2023

APPLY BY: October 10, 2023

ISSUES OVERSIGHT

BOARD OVERSIGHT OF CLIMATE CHANGE.

BUILDING THE BOARD’S CLIMATE COMPETENCY

Effective climate change oversight does not involve a straight path or simple solution. Understand how to frame the risks and opportunities and embed a viable adaptation strategy.

ONLINE November 1, 2023

APPLY BY: October 11, 2023

ISSUES OVERSIGHT

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION FROM THE BOARDROOM.

ADD STRATEGIC VALUE TO THE DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION PROCESS WHILE FULFILLING THE BOARD’S OVERSIGHT DUTIES

Understand the board’s role in establishing the digital transformation vision, ambition and roadmap.

ONLINE November 22, 2023

APPLY BY: November 1, 2023

TO ELEVATE YOUR DIRECTORSHIP IN 2023, VISIT EDUCATION.ICD.CA/CALENDAR24

ISSUES OVERSIGHT

BOARD OVERSIGHT OF SOCIAL ISSUES.

CONNECTING SOCIAL ISSUES AND STRATEGY IN THE BOARDROOM

Acquire practical insights and a greater understanding of a board’s role in oversight of social issues.

ONLINE November 28, 2023

APPLY BY: November 7, 2023

Not sure which course is the right fit for you? Call 416.593.3349 or email education@icd.ca for a personal consultation.

DIRECTOR EFFECTIVENESS

CROWN DIRECTOR EFFECTIVENESS.

PRACTICAL PRINCIPLES AND STRATEGIES FOR CROWN DIRECTOR EFFECTIVENESS

Discover the unique circumstances and challenges that exist when serving on the board of government-controlled entities.

ONLINE November 7, 2023

APPLY BY: October 17, 2023

If JOHN BOWEY is feeling any fatigue in the third period of his career, it’s not apparent to his teammates. The ICD Fellow and chair of a major insurance company tells business writer Gordon Pitts that an effective boardroom requires high aspirations and the tenacity to win Si JOHN BOWEY ressent de la fatigue à la troisième étape de sa carrière, personne dans son équipe ne s’en aperçoit. Le Fellow de l’IAS et président du conseil d’une grande compagnie d’assurance explique au journaliste Gordon Pitts qu’un conseil efficace exige de ses administrateurs des aspirations élevées et la ténacité nécessaire pour gagner.

IN HIS YOUTH, John Bowey was a pretty good hockey player – so good that a U.S. college recruited him. In collegiate hockey, he played the centre position, which typically requires a lot of stickhandling.

More than five decades later, Bowey still plays recreational hockey, but most of his stickhandling takes place in the boardroom. Most notably, he has guided one of the most dramatic transitions in the form and structure of a Canadian business.

For more than a decade, as a director and chair of Economical Insurance and its successor, he has led the evolution of a comfortable, laid-back mutual insurer with rural Southwestern Ontario roots to an industry innovator, and the subject of one of the largest public offerings in Canadian history. With a new name, Definity Financial Corp., it has changed what it is and, to a large extent, what it stands for.

Bowey’s leadership at Economical, and on the boards of several for-profit and non-profit organizations, underpins his induction this year as a Fellow of the Institute of Corporate Directors.

DANS SA JEUNESSE, John Bowey fut un très bon joueur de hockeyeur – au point d’être recruté par une université américaine. Au hockey universitaire, il jouait au centre, ce qui requiert généralement un excellent maniement de bâton.

Plus de cinq décennies plus tard, M. Bowey joue toujours au hockey pour s’amuser, mais son maniement du bâton se déploie surtout à la table du conseil. En particulier, il a inspiré l’une des transitions les plus importantes dans la forme et la structure d’une entreprise canadienne.

Pendant plus d’une décennie, comme administrateur et président du conseil d’Assurance Economical et de l’entreprise qui lui a succédé, il a assuré le passage d’une compagnie d’assurance douillette et discrète ayant des racines rurales dans le Sud de l’Ontario à un statut d’innovatrice de l’industrie, qui a fait l’objet de l’une des plus importantes offres publiques d’achat de l’histoire canadienne. Avec une nouvelle raison sociale, Société financière Definity, l’entreprise a changé son identité et, dans une large mesure, sa raison d’être.

Le leadership de John Bowey chez Economical – et aux conseils

'Boards can be a competitive weapon in the organizations they serve,' says John Bowey, who led the demutualization of Economical Insurance.

The Economical story, in particular, contains broader lessons about how a board can lead change, how it can stand in the vanguard of transition in the company’s culture, and foster a relationship with management that is both challenging and supportive.

“I think boards make a difference,” says Bowey, now the chair of publicly traded Definity Financial, the holding company for Economical and other insurance assets. “You often think of boards as providing oversight – they make sure you don’t take on unnecessary risk; they hold things together.”

All that is true and appropriate, but, also, “boards can be a competitive weapon in the organizations they serve.” That happens by combining deep thought with high aspiration – to “think about the future and the path forward and what it takes to compete and succeed.”

That means forging a balanced relationship with management that might be called respectful rapport. “It’s not like we are in each other’s pockets,” he says, speaking of his own experience at Economical, “but we have built a healthy challenge to each other and, in the process, we have changed the culture in a significant way.”

The path of Economical/Definity has unique twists, but Bowey says that in a changing insurance industry, “any board [would have] had to come to grips with [the question of] ‘how we compete and win.’”

His Economical tenure marks one of several times when Bowey has found himself on the cusp of change. In a long career at Deloitte Canada, he rose to leadership positions in the firm, occupying a front-row seat to the Enron-Arthur-Andersen debacle that shook the professional services industry in 2001-2002, and the global financial crisis of 2007-2008.

When he retired from Deloitte in 2010, he took on other director roles. Approached to join the board at mutual insurer Economical, he assumed it would be an interesting mission, not an adventure in revolutionary change. However, the landscape at the 140-year-old property and casualty insurer – a 19th-century collective founded by farmers to cover fire hazards – was already shifting below the board’s feet.

Change was bubbling up from competitive forces in a changing industry – exacerbated by a mutual company’s inability to raise outside capital – and from its base of mutual policyholders who voted in the board.

It forced the board to take up the idea of “demutualization,” and new director John Bowey found himself immersed in a decade of corporate reinvention.

That process could take up an entire book. Economical’s own definition of demutualization is: “A complex, regulated process to transition from a mutual, policyholder controlled insurance company to a publicly listed company with corporate shareholders.” It all culminated in late 2021 with an initial public offering of $2.1-billion.

A change this big, in altering the corporate form of an organization, had to be board-led. But first, there was the stickhandling.

The makeover of Economical required a dance among several entities, including the federal government, which set the rules of this

de nombreuses organisations à buts lucratif et non lucratif – lui vaut son intronisation cette année à titre de Fellow de l’Institut des administrateurs de sociétés.

L’histoire d’Economical, en particulier, offre de grandes leçons sur la manière dont un conseil peut inspirer le changement, comment il peut demeurer à l’avant-garde d’une transition dans la culture d’une entreprise et favoriser un rapport avec la direction à la fois stimulant et coopératif.

« Je crois que les conseils font une différence, affirme M. Bowey, aujourd’hui président du conseil de l’entreprise inscrite en bourse Definity Financial, la société de portefeuille qui regroupe Economical et d’autres actifs d’assurance. On considère souvent les conseils comme des groupes qui exercent une surveillance, s’assurent que leurs organisations ne prennent pas de risques inutiles et maintiennent l’équilibre. »

Tout cela est vrai, mais « les conseils peuvent aussi s’avérer une arme concurrentielle. » Cela se produit en combinant une réflexion profonde et des aspirations élevées, ce qui consiste à « penser à l’avenir de l’organisation et à ce qu’il faut pour livrer concurrence et réussir. »

Cela implique d’établir une relation équilibrée et respectueuse avec la direction. « Ce n’est pas comme être dans les souliers de l’autre, dit-il en évoquant son expérience chez Economical. Mais nous nous sommes lancés de sains défis et, au fil du processus, nous avons changé la culture de manière importante. »

Le parcours d’Economical/Definity a connu des rebondissements uniques, mais M. Bowey soutient que dans une industrie aussi changeante que l’assurance, « n’importe quel conseil aurait dû résoudre la question de savoir « comment compétitionner et gagner. »

Son mandat chez Economical a été l’une des nombreuses occasions où il s’est trouvé au cœur du changement. Au cours d’une longue carrière chez Deloitte Canada, il s’est hissé à des postes de leadership, occupant les premières loges lors de la débâcle Enron-Arthur Andersen, qui a secoué l’industrie des services professionnels en 2001-2002, et pendant la crise financière mondiale de 2007-2008. Quand il a quitté Deloitte en 2010, il a accepté d’autres postes d’administrateur. Invité à siéger au conseil de l’assureur mutuel Economical, il a présumé que ce serait une mission intéressante et pas l’aventure d’un changement révolutionnaire. Cependant, le sol de cette compagnie d’assurance vieille de 140 ans commençait déjà à se dérober sous les pieds du conseil.

Le changement émergeait, poussé par les forces concurrentielles d’une industrie en mutation – exacerbé par une incapacité de l’entreprise à lever des capitaux extérieurs – et par ses sociétaires d’assurance mutuelle qui élisaient le conseil d’administration.

La situation a forcé le conseil à souscrire à l’idée d’une « démutualisation » et le nouvel administrateur John Bowey s’est trouvé plongé dans une décennie de réinvention corporative.

Ce processus pourrait faire l’objet d’un livre. La propre définition de la démutualisation, selon Economical, est : « Un processus complexe et réglementé en vue d’assurer la transition entre une société d’assurance mutuelle contrôlée par les sociétaires et une société inscrite en bourse appartenant à des actionnaires. » Le tout a

unprecedented demutualization of a property and casualty company in Canada. (A number of life insurers had already been through the process.) Trips to Ottawa became part of the chair’s routine.

Then there was balancing the interests of mutual policyholders – fewer than 1,000 people, who elected the board – and more than 600,000 cash policyholders (of whom this writer was one). The two groups conducted protracted negotiations on the process of dividing the monetary rewards of changing to a public company, as Ottawa had mandated.

But who represented the company in all this wrangling? That was a role that Bowey and his colleagues took very seriously. “It was not just about monetizing policyholders – we wanted the company to survive and compete and do well,” Bowey says.

Former technology CEO Daniel Fortin, who joined the board in the fall of 2014, credits the chair’s willingness to stop the process at any point, if necessary, and ask: “Is this action in the interests of the company?”

“John would always bring us back to our responsibility for the best interests of Economical and not be swayed by other elements.”

The board kept reminding the policyholder representatives that their job was to come to an answer, and if they didn’t, the process would come to a halt. Directors made a crucial proposal that helped break the logjam of negotiations: the idea of a foundation to be funded by some of the dollars from the proceeds of going public.

Thus, the company would retain a vestige of the community-focused, neighbour-helping-neighbour culture that had given birth to Economical in the 1870s. Once embraced, it eased the sense that the process was simply a windfall generator for policyholders.

But to survive in its new form – unprotected by the mutual status – it would have to be a much different culture than the quietly effective Economical of the past.

culminé à la fin de 2021 avec une offre publique d’achat initiale de 2,1 milliards de dollars.

Un changement aussi important, qui altérait la forme de l’organisation, devait être mené par le conseil. Mais d’abord, il y avait le maniement du bâton.

La transformation d’Economical exigeait de danser avec beaucoup de partenaires, dont le gouvernement fédéral, qui établissait les règles de cette démutualisation sans précédent d’une société d’assurance de dommages au Canada.

Il y avait ensuite l’équilibrage des intérêts des sociétaires – moins de 1 000 personnes, qui élisaient le conseil – et plus de 600 000 détenteurs de polices en espèces. Les deux groupes menèrent de longues négociations sur la répartition des avantages monétaires résultant de la transformation en société publique, comme Ottawa l’exigeait.

Mais qui représentait l’entreprise dans tout ce processus? C’est un rôle que M. Bowey et ses collègues prenaient très au sérieux. « Il ne s’agissait pas seulement de distribuer de l’argent aux détenteurs de polices. Nous voulions aussi que l’entreprise survive, puisse livrer concurrence et prospérer », affirme M. Bowey.

L’ancien chef de la direction d’une entreprise technologique Daniel Fortin, qui s’est joint au conseil à l’automne 2014, salue la volonté du président du conseil de stopper alors le processus à n’importe quel moment, si nécessaire, et de demander si tel ou tel geste était dans l’intérêt de la compagnie.

« John nous ramenait toujours à nos responsabilités envers les meilleurs intérêts d’Economical et l’importance de ne pas être distraits par d’autres éléments. »

Le conseil rappelait constamment aux représentants des détenteurs de polices que leur travail consistait à offrir des réponses et que s’ils en étaient incapables, le processus allait s’interrompre. Les administrateurs ont alors émis une proposition cruciale qui a contribué à dénouer l’impasse : l’idée d’une fondation qui serait financée par une partie des dollars issus du produit de l’émission d’actions.

‘JOHN WOULD ALWAYS BRING US BACK TO OUR RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE BEST INTERESTS OF ECONOMICAL AND NOT BE SWAYED BY OTHER ELEMENTS.’

« JOHN NOUS RAMENAIT TOUJOURS À NOS RESPONSABILITÉS ENVERS LES MEILLEURS INTÉRÊTS D’ECONOMICAL ET L’IMPORTANCE DE NE PAS ÊTRE DISTRAITS PAR D’AUTRES ÉLÉMENTS. »

—DANIEL FORTIN, BOARD MEMBER OF DEFINITY FINANCIAL

For Bowey, “the board sets the tone at the top.” He adds that “we wanted to survive and remain an independently owned Canadian company; we wanted to be there for our communities and people.”

But if the company went public and continued its steady-as-itgoes pace, and failed to perform at a level the markets expected, it would have “a short life,” he knew. “We decided if we do it, we do it to be a leader: Lead change, [don’t] follow change.”

The culture had to shift “from slow-to-move and comfortable in not doing things too quickly, to being bold and ambitious, taking some chances and aspiring to lead, not just caught in the middle of the pack.”

One of the key moves was the choice of the next CEO, as someone who could lead the charge. The board found Rowan Saunders, a veteran Canadian insurance executive, who both knew the industry and was keen to take the reins of a new public company.

When he joined in late 2016, Saunders discovered the Economical board to be different in its approach from what he had expected. “I do think the board is extremely ambitious and, particularly John, had a vision of what a domestic champion could look like.”

Indeed, “sometimes we have had management hold the board back, as opposed to the reverse. That gives you an indication of the boldness and aspiration that the board has.”

The most profound, and often wrenching, part of this transformation has been the personnel changes. A number of employees did not buy into the new culture of a public company with quarterly performance demands, Saunders says. The board supported senior management as the team was substantially overhauled. In the employee ranks, at least a third of staff has been replaced, the CEO says.

Bowey says in the mutual era, “they did good work and gave back, wrote good policies and served the community.” But in the transformation, “some people said they couldn’t take the pace – too much change, too quickly.” The lesson is that change can be uncomfortable.

However difficult, the overhaul has generated some positive results. Employment engagement surveys, which Bowey describes as mediocre several years ago, have moved into the 80-per-cent-engaged category – a strong showing, he feels, in an era of Covid-19 and huge company change.

Daniel Fortin, a former president of IBM Canada, was impressed when he joined the board that it had embraced the imperative of technology change. Specifically, the board led the move toward the introduction of a digital sales channel, which would complement its mainstream broker network. The result was the 2016 launch of its Sonnet direct-to-consumer subsidiary.

As it made this investment, the company had to reassure insurance brokers who were at the heart of its business. “If we offended our brokers, we were in big trouble” Bowey said. The board and management worked through how to address this tension. The next big investment in technology was aimed at supporting the brokers’ channel.

But isn’t Definity still vulnerable in its long-term future as a public company? “We have to perform,” Bowey says simply. “We have

Ainsi, l’entreprise allait conserver une empreinte de sa vocation communautaire et de la culture d’entraide entre voisins qui avaient donné naissance à Economical dans les années 1870. Une fois cette proposition adoptée, elle a atténué l’impression que le processus était simplement une façon d’enrichir les détenteurs de police.

Mais pour survivre dans sa nouvelle forme – sans la protection du statut de mutualité – il fallait instaurer une culture très différente de l’entreprise discrètement efficace qu’avait été Economical jusqu’alors.

D’après M. Bowey, « le conseil a donné le ton. Nous voulions survivre et demeurer une entreprise canadienne indépendante; nous voulions être là pour nos communautés et pour les gens ».

Mais une fois inscrite en bourse, si la compagnie maintenait son rythme de stabilité peinarde et échouait à répondre aux attentes des marchés, il savait que son existence serait brève.

La culture devait donc passer « de cette manière de faire les choses sans se presser à une approche audacieuse et ambitieuse. Il fallait prendre quelques risques et viser haut, pas seulement se contenter du milieu du peloton. »

L’une des premières mesures en ce sens fut le choix du prochain chef de la direction. Le conseil jeta son dévolu sur Rowan Saunders, un cadre chevronné du secteur de l’assurance, qui connaissait l’industrie et était désireux de prendre les rênes d’une société ouverte.

Quand il a entrepris son mandat fin 2016, M. Saunders découvrit que l’approche du conseil d’Economical était différente de ce à quoi il s’attendait. « Le conseil est extrêmement ambitieux, en particulier John qui avait une vision de ce qu’un champion national pouvait être. Alors que parfois, c’est la direction qui retient le conseil. »

L’aspect le plus profond – et souvent déchirant – de cette transformation se situait sur le plan personnel. Plusieurs employés n’ont pas adhéré à la nouvelle culture d’une société ouverte forcée de rendre des comptes chaque trimestre, explique M. Saunders. On a dû remplacer au moins le tiers du personnel.

M. Bowey reconnaît qu’à l’époque de la mutuelle, « ils ont fait du bon travail, établi de bonnes polices et redonné à la communauté. Mais certains ont dit qu’ils ne pouvaient pas tenir le rythme; trop de changement trop vite. »

Malgré les difficultés, la réorganisation a donné des résultats positifs. Les résultats des sondages sur l’engagement des employés, médiocres il y a quelques années, atteignent maintenant 80 pour cent.

Quand il s’est joint au conseil, Daniel Fortin, ancien chef de la direction d’IBM Canada, fut impressionné par son adhésion à l’impératif de changements technologiques. Le conseil a notamment inspiré l’instauration d’un canal de ventes numériques pour compléter son réseau de courtiers. C’est ainsi que fut lancée en 2016 la filiale Sonnet de vente directe au consommateur.

En menant cet investissement, l’entreprise devait rassurer les courtiers qui étaient au cœur de ses activités. L’investissement technologique visait précisément à soutenir son réseau de courtiers.

Mais en tant que société publique, Definity ne demeure-t-elle pas vulnérable à long terme? « Nous devons offrir de bonnes performances, dit simplement M. Bowey. Servir les intérêts des

to look out for the best interests of shareholders and that is to create long-term value” to keep the shares rising.

Fortunately, the board learned a lot about change. Among other things, “you do learn to listen,” and be respectful of the various legitimate interests, he says. The old hockey player agrees that stickhandling is a pretty good description for what he does, on and off the ice. DJ

GORDON PITTS is a Toronto journalist whose latest book, Unicorn in the Woods: How East Coast Geeks and Dreamers Are Changing the Game, was longlisted for a National Business Book award.

Chair of Definity Financial Corp.

Président du conseil de Definity Financial Corp.

75 years old.

Born in Galt, Ont., now part of Cambridge. Based today in Kitchener-Waterloo.

Bachelor’s degree from Colby College, Maine, 1971.

MBA from the Ivey School of Business, Western University, 1973.

Joined Deloitte right out of MBA school, and stayed for 37 years.

Rose to head the tax practice in Southwestern Ontario, then appointed managing partner for the region, and elected to the national board. Served as chair of Deloitte Canada until his retirement.

Chair of the Deloitte Canada board from 2006 to 2010.

Joined the board of Economical Insurance in 2011. Later appointed chair of Economical and its successor, Definity Financial. Also continues to serve as a director of the Definity Insurance Foundation.

Board member and chair of the audit committee at Kognitiv Corp., 2010 to present.

Chair of the special committee on Economical’s demutualization, from July 2011 to January 2016.

Board member and chair of the audit committee for Waterloo Brewing, from 2010 until 2023. A pioneer in craft brewing, the company was sold this year to Carlsberg of Denmark.

Chair of the board of the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation from 2010 to 2012.

Served on board of governors of Wilfrid Laurier University from July 2011 to June 2019. Chair of the board from 2015 to 2017.

actionnaires en créant de la valeur à long terme. »

Heureusement, le conseil en a appris beaucoup sur le changement. « On apprend à écouter », conclut-il, et à respecter les divers intérêts légitimes. À cet égard, l’ancien joueur de hockey admet que le maniement du bâton décrit bien son rôle, sur la glace et ailleurs. DJ

GORDON PITTS est un journaliste de Toronto dont le plus récent ouvrage, Unicorn in the Woods: How East Coast Geeks and Dreamers Are Changing the Game, a été sélectionné pour le National Business Book Award.

75 ans.

Né à Galt, Ont., aujourd’hui Cambridge. Demeure à Kitchener-Waterloo.

Baccalauréat de Colby College, Maine, 1971.

MBA de l’Ivey School of Business, Université Western, 1973.

Dès son MBA complété, il entre à l’emploi de Deloitte, où il demeurera pendant 37 ans.

Occupe le poste de chef de la pratique fiscale du Sud de l’Ontario, puis associé directeur pour la région, élu ensuite au conseil d’administration national de Deloitte. Président du conseil de Deloitte Canada jusqu’à sa retraite.

Président du conseil de Deloitte Canada de 2006 à 2010.

Administrateur d’Assurance Economical en 2011. Nommé plus tard chef de la direction d’Economical et ensuite de la Société financière Definity. Aussi administrateur de la Fondation Definity.

Administrateur et président du comité d’audit de Kognitiv Corp. depuis 2010. Président du comité spécial de démutualisation d’Economical de juillet 2011 à janvier 2016.

Administrateur et président du comité d’audit de Waterloo Brewing de 2010 à 2023. Pionnière de la brasserie artisanale, l’entreprise fut vendue cette année à Carlsberg du Danemark.

Président du conseil de la Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation de 2010 à 2012.

A siégé au conseil des gouverneurs de l’Université Wilfrid Laurier de juillet 2011 à juin 2019. Président du conseil de 2015 à 2017.

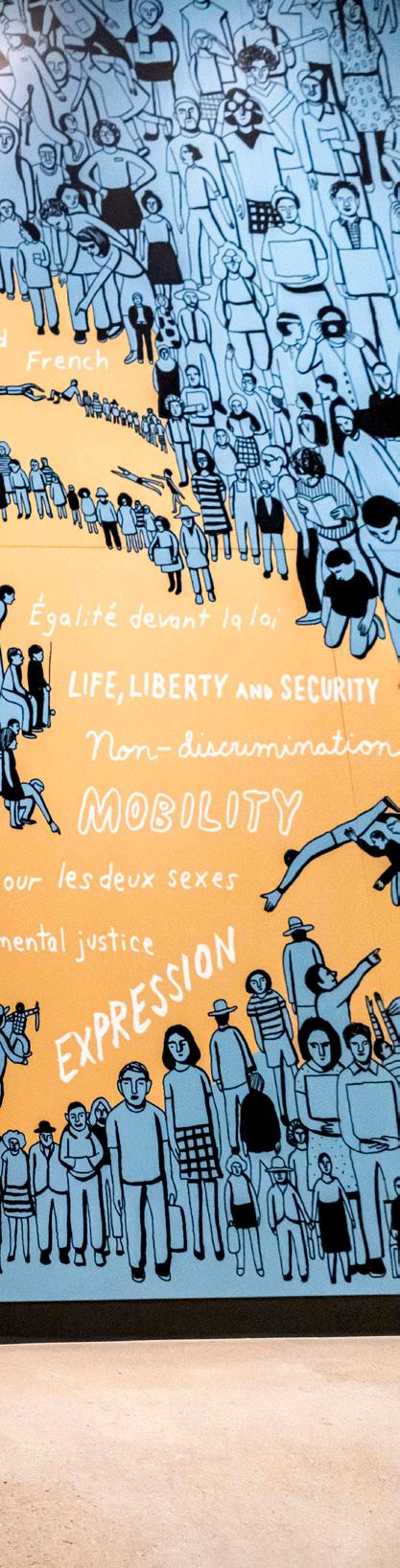

As the Canadian Museum for Human Rights continues to enact reforms that followed systemic racism charges three years ago, board member Benjamin Nycum details some of the lessons learned and encourages other directors to begin the personal journey necessary to dismantle harmful and oppressive systems Alors que le Musée canadien pour les droits de la personne continue de mettre en œuvre des réformes à la suite des accusations de racisme systémique portées il y a trois ans, l’un de ses administrateurs, Benjamin Nycum, précise certaines leçons qu’il en a tirées et invite les autres membres du conseil à entreprendre le parcours personnel nécessaire pour mettre fin à ces systèmes pernicieux et oppressants.

THE MORNING SUN WARMED MY FACE. Summer at home in Nova Scotia was hitting its stride. We had reached and passed the “Wow, this is serious!” phase of Covid-19 and were in the “surrender, accept and hope stage.”

On a personal level, I was processing events that were consuming my board and the organization I love. In June of 2020, three months into the pandemic, allegations of systemic racism surfaced at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR), a Crown corporation where I am a member of the board of trustees. The allegations and revelations made national news, created upheaval at the museum and forced me to confront some rough and damning things about my participation in harmful and oppressive systems. I was also making a promise to myself and others to change.

The Covid-19 pandemic exposed and disrupted systems that have been in place for centuries. These systems rely on and reinforce social, economic and power structures. On May 25, 2020, video

LE SOLEIL MATINAL RÉCHAUFFAIT MON VISAGE. La saison d’été en Nouvelle-Écosse atteignait son point culminant. Nous avions dépassé le stade du « Wow, c’est sérieux! » de la Covid-19 pour entrer dans celui de l’abandon, de l’acceptation et de l’espoir. Personnellement, j’assimilais les événements qui consumaient mon conseil et l’organisation que je chéris. En juin 2020, trois mois après le début de la pandémie, des allégations de racisme systémique ont émergé au Musée canadien pour les droits de la personne (MCDP), une société d’État dont je suis l’un des administrateurs. Ces révélations ont fait les manchettes à l’échelle nationale, plongé le Musée dans la tourmente et m’ont forcé à faire face à des constats difficiles et accablants sur ma participation à des systèmes pernicieux et oppressants. J’ai aussi promis – à moi-même et aux autres – de changer.

La pandémie de Covid-19 a exposé et perturbé des systèmes en vigueur depuis des siècles. Ces systèmes s’appuyaient sur des struc-

footage of police in Minneapolis killing George Floyd – along with Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the murder – made the injustice of the status quo undeniable.

On June 1, the CMHR responded with a social media post stating: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” This was a standard type of response by the museum to an event that illuminated the perilous state of human rights around the world – but there was nothing standard about the event.

While it is not unusual for social media posts to receive negative comments, the museum’s subdued reaction to the murder generated an unusual level of anger, demanding more than words, with some employees accusing the CMHR of lying about its own internal issues.

In response, on June 8, the museum posted a message from the CEO saying, “I acknowledge it is not enough for the Museum to make statements opposing racism. We must identify shortcomings and blind spots, both within ourselves as individuals and within the Museum, and take concrete steps to improve.”

The post drew significant criticism in the comments, among them former employees using the hashtag “#CMHRstoplying” to report that they had experienced racism while working at the museum. The museum continued to operate as if things were normal, viewing the comments as par for the course.

All that changed on June 10, when the CBC posted an article on its website entitled “Former Employees of CMHR Say They Faced Racism, Mistreatment.”

tures sociales, économiques et de pouvoir et les renforçaient. Le 25 mai 2020, des images d’un policier de Minneapolis en train de tuer George Floyd – et des protestations de Black Lives Matter provoquées par le meurtre – ont rendu incontestable l’injustice du statu quo.

Le 1er juin, le MCDP a réagi dans les médias sociaux en déclarant : « Tous les êtres humains sont nés libres et égaux en dignité et en droits. » C’était un type de réaction standard à un événement qui a mis en lumière l’état périlleux des droits de la personne à travers le monde. Mais il n’y avait rien de standard dans l’événement.

Même s’il n’est pas rare que des publications sur les médias sociaux soient l’objet de commentaires négatifs, la réaction timide du musée à ce meurtre a suscité un degré de colère inhabituel. Ce meurtre exigeait plus que des mots et certains employés ont accusé le MCDP de mentir à propos de ses propres problèmes internes.

Dans la foulée, le 8 juin, le musée publiait un message de la directrice affirmant : « Je reconnais qu’il ne suffit pas pour le Musée de faire des déclarations contre le racisme. Nous devons identifier les lacunes et les angles morts, en nous-mêmes et au sein du Musée, et adopter des mesures concrètes pour nous améliorer. »

La publication a suscité beaucoup de critiques, notamment de la part d’anciens employés qui ont utilisé l’hashtag « #CMHRstoplying » (#MCDPcessezdementir) pour expliquer qu’ils avaient vécu du racisme durant leur emploi au musée. Celui-ci continuait de mener ses activités comme si de rien n’était, considérant ces commentaires comme normaux.

In June, 2020, when accusations were made online accusing the Canadian Museum for Human Rights of racism, the organization continued to operate as if things were normal — until coverage of the charges by the CBC sent the board into crisis mode.

‘When it comes to interrogating the underlying systems of oppression that caused our crisis, ... there is also a personal journey that must be undertaken,’ says CMHR board member Benjamin Nycum.

Things were now spinning out of control. The museum quickly learned that an important message it had discounted or ignored was being heard.

The board was now immersed in a bewildering crisis. Little did we know this was just the beginning. One week later, on June 18, the CBC posted a second story: “Canadian Museum for Human Rights Employees Say They Were Told to Censor Gay Content for Certain Guests.”

The next day, the museum formally issued an apology stating: “For breaking the trust that was extended to us by the LGBT2Q+ community … we apologize.”

This was an existential crisis for a museum focused on human rights. It demanded the board’s absolute attention.

Our executive team, board and staff entered crisis mode, meeting virtually across four time zones for a few hours every day. Our board chair, Pauline Rafferty, temporarily relocated from Victoria to the museum’s home of Winnipeg for the summer to take up the role of interim CEO, following the departure of the museum’s CEO, John Young. We formed a diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) committee overnight and populated it with external experts with lived experience. The committee met weekly, and its responsibilities included overseeing a review into the allegations of systemic racism and oppression at the museum. The review was prepared by Laurelle Harris, a lawyer engaged by the board.

It has been three years since that summer. The questions we ask ourselves and are asked the most are: Why did you not you see this? What could the board have done to see the signs? What metrics are you tracking now?

At face value, the answers to these questions are simple enough. But when it comes to interrogating the underlying systems of oppression that caused our crisis (and have caused crises in many other organizations since), there is also a personal journey that must be undertaken.

Our board has always wanted to do the right thing, follow the proper procedure, enact the best governance. We want to manage and lead with authenticity, with an eye to making the world and the organization a bit better than when we started. But we have discovered it is not that simple. The crisis showed that we were not ready. Systemic inequity and injustice aren’t the usual topics a board considers. They go far beyond regular governance issues, such as finance, sustainability and strategy – they are about people, contemporary society and history.

We learned that typical, robust and even exemplary governance can create blinders. Our institutions are governed by systems designed to sustain an organization as well as the systems’ own prevalence. They are built to prevent disruptive issues from surfacing. But occasionally, a major event such as a pandemic or international protest will bring suppressed issues boiling to the surface.

Tout a changé le 10 juin, quand CBC a publié sur son site Web un article intitulé « D’anciens employés du MCDP affirment avoir vécu du racisme et de la maltraitance ».

Les choses échappaient maintenant à tout contrôle. Le musée a rapidement compris qu’un message important qu’il avait écarté ou ignoré était entendu.

Le conseil était désormais plongé dans une crise embarrassante. Mais nous ne nous doutions pas que ce n’était que le début. Une semaine plus tard, le 18 juin, CBC publiait un deuxième article : « Des employés du Musée canadien pour les droits de la personne affirment qu’on leur a ordonné de censurer du contenu gai pour certains invités. »

Le lendemain, le musée s’excusait formellement : « Pour avoir brisé la confiance placée en nous par la communauté LGBT2Q+… nous nous excusons. »

Ce fut une crise existentielle pour un musée consacré aux droits de la personne. Elle exigeait une attention absolue de la part du conseil.

Le conseil et l’équipe de direction sont entrés en mode de crise, chacun participant chaque jour pendant quelques heures à des rencontres virtuelles touchant quatre fuseaux horaires. La présidente du conseil, Pauline Rafferty, a momentanément quitté Victoria pour s’établir à Winnipeg – où est situé le Musée – durant l’été afin d’occuper le poste de cheffe de la direction à titre intérimaire à la suite du départ de John Young. Nous avons aussitôt créé un comité sur la diversité, l’équité et l’inclusion et l’avons doté de spécialistes de l’extérieur. Le comité se réunissait chaque semaine et ses responsabilités comprenaient notamment la surveillance de l’analyse des allégations de racisme systémique et d’oppression au musée. L’analyse fut préparée par Laurelle Harris, une avocate embauchée par le conseil.

Trois années se sont écoulées depuis. Les questions les plus souvent posées demeurent : « Comment cela vous a-t-il échappé? Qu’aurait pu faire le conseil pour reconnaître les signes? Quels paramètres vous guident aujourd’hui? »

À première vue, les réponses sont simples. Mais quand vient le temps d’interroger les systèmes d’oppression sous-jacents qui ont causé la crise (et en ont causé depuis dans bien d’autres organisations), il faut entreprendre un parcours personnel.

Notre conseil a toujours voulu bien faire, suivre la procédure appropriée, pratiquer la meilleure gouvernance. Nous voulons gérer avec authenticité, rendre le monde et notre organisation meilleurs. Mais ce n’est pas si simple. La crise a montré que nous n’étions pas prêts. L’inégalité et l’injustice systémiques ne font pas partie des enjeux habituels d’un conseil. Cela va bien au-delà des questions de gouvernance. Il s’agit des gens, de la société contemporaine et de l’Histoire.

Nous avons appris qu’une gouvernance représentative, robuste et exemplaire peut créer des œillères. Nos institutions sont gouvernées par des systèmes conçus pour soutenir une organisation

Covid-19 disrupted almost every organization’s basic systems and cast a spotlight on parts of society that don’t work for everyone. Insightful leaders need to understand that signs of trouble may present themselves in a subtle manner and may not be issues typically discussed at a board meeting. As board members, we need to be probing for these signs.

In our boardrooms, we should create the space and time to talk in a meaningful way about the things that are relegated to the periphery or left to simmer beneath the surface. This requires courage and commitment. As directors, we need to be open to making a safe space for questions that are partly formed, that don’t fit the agenda framework, that need a bit of time to form. At the museum, we have learned that we must make space to ask and listen to the quiet voices, and unpack matters that arise from the least powerful in and outside our organization. It can be helpful to look for trends, such as a pattern of resignations.

For a board to be critical of systems that oppress, there are two key steps. The first is a personal journey to recognize that we each see the world in our own specific way, one that is not always fair or just. The more you deconstruct your own power, the more you will see the signs. This process includes becoming informed about systems of oppression; learning more diverse perspectives; analyzing your own role in upholding systems of privilege; and challenging language and nomenclature by asking “What do we mean when we say this?”

The second is to allow discussion of these issues in the boardroom outside of the prescribed agenda. Your board may be executing typical governance, like us. But that framework is not suited for these conversations. In fact, the opposite is true: It insulates us from them.

The report by Laurelle Harris made recommendations “to begin the process of remediating harmful practices that contribute to systemic oppression and inequality” at the museum. We have implemented, or are in the process of implementing, all of them. We are also questioning and challenging the metrics we need to ensure that we continue to develop a culture that eliminates systemic oppression and bias.

When our board chair took up the position of interim CEO at the peak of the crisis, she met with more than 60 staff groups and stakeholders, listening carefully to their concerns. Although having direct discussions with staff isn’t a part of traditional governance, we continue to have them on an annual basis. We have also restructured our committees, including eliminating our new DEI committee and incorporating a DEI mandate into each committee’s terms of reference.

Is deconstructing and dismantling systems of oppression, and questioning the role of governance, the work of a director? Is a personal journey to investigate one’s own role in privilege and power a fundamental asset akin to the ability to read a financial statement? I think so. It’s not just about trying to become a better person – there is basic corporate sustainability and survival at stake. Today’s workforce has more choice and flexibility than ever

et la prévalence de ces systèmes. Ceux-ci sont construits pour empêcher d’émerger des enjeux qui dérangent. Mais à l’occasion, un événement majeur – pandémie ou protestations internationales – amène à la surface des enjeux jusqu’alors ignorés.

La Covid-19 a perturbé les systèmes de presque toutes les organisations et jeté les réflecteurs sur des éléments qui ne fonctionnent pas pour tout le monde. Des leaders perspicaces doivent comprendre que les signes avant-coureurs de crise peuvent se présenter de façon subtile sans avoir fait l’objet de discussions au conseil. Comme administrateurs, nous devons identifier ces signes.

Au sein de nos conseils, nous devrions créer l’espace et le temps nécessaires pour discuter de ce qui a été relégué à la périphérie ou dort sous la surface. Cela exige du courage et de l’engagement. Comme administrateur, il faut être ouvert à des questions nouvelles et difficiles. Au musée, nous avons appris qu’il faut prendre le temps d’écouter les voix plus discrètes et décortiquer ces questions qui sont soulevées par les éléments les moins puissants de l’intérieur et de l’extérieur de notre organisation.

Qu’aurait pu faire le conseil pour reconnaître ces signes?