VOL LXXV | ISSUE III | MMXXV © Trinity Publications 2025

Icarus was founded in 1950 by Alec Reid, who described its mythic title as “at once a prophecy of disaster and an insurance against it,”1 a symbol of both !ight and falter. As indicated by its title, the !edgling publication — initially sold for a shilling at the college gates — was not expected to last. And yet today, Icarus holds the distinction of being the oldest continuously published arts journal in Britain and Ireland.

Icarus has shaped, and was shaped by, some of Ireland’s foremost poets and playwrights. "e 1960s saw the rise of what Derek Mahon later coined “the Icarus crowd” — a group that included Michael Longley, Edna Broderick, Brendan Kennelly, Eavan Boland, and Mahon himself. Icarus soon garnered a reputation for intercepting writers at the beginnings of their illustrious careers. By 1998, the pressure of handling the publication’s reputation was keenly felt by the editors: “too much time and e ort has gone into this publication for it to be a rattlebag of random work and respect.”2

Icarus rests on these shoulders; on our shoulders; and on your shoulders, too.

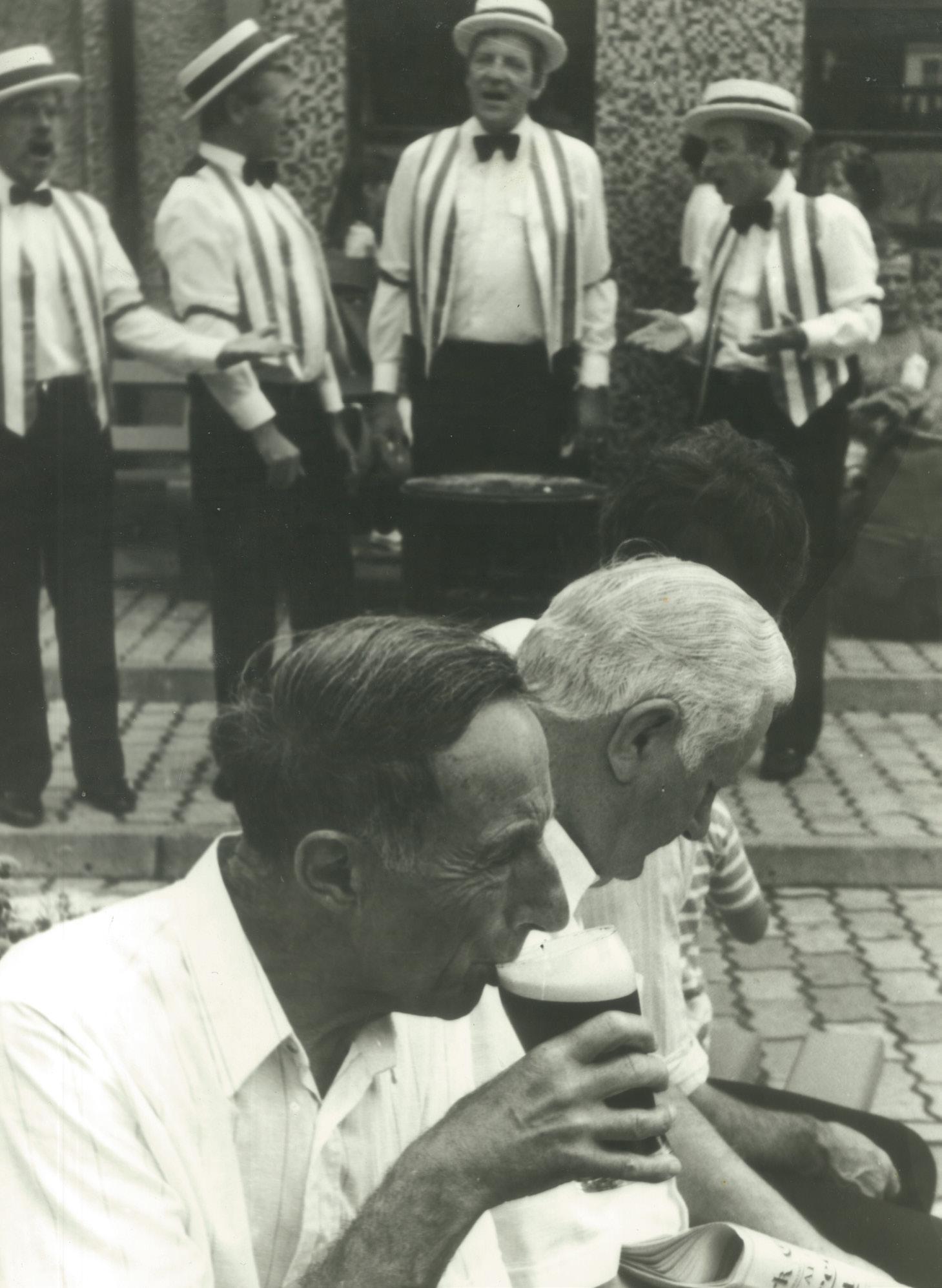

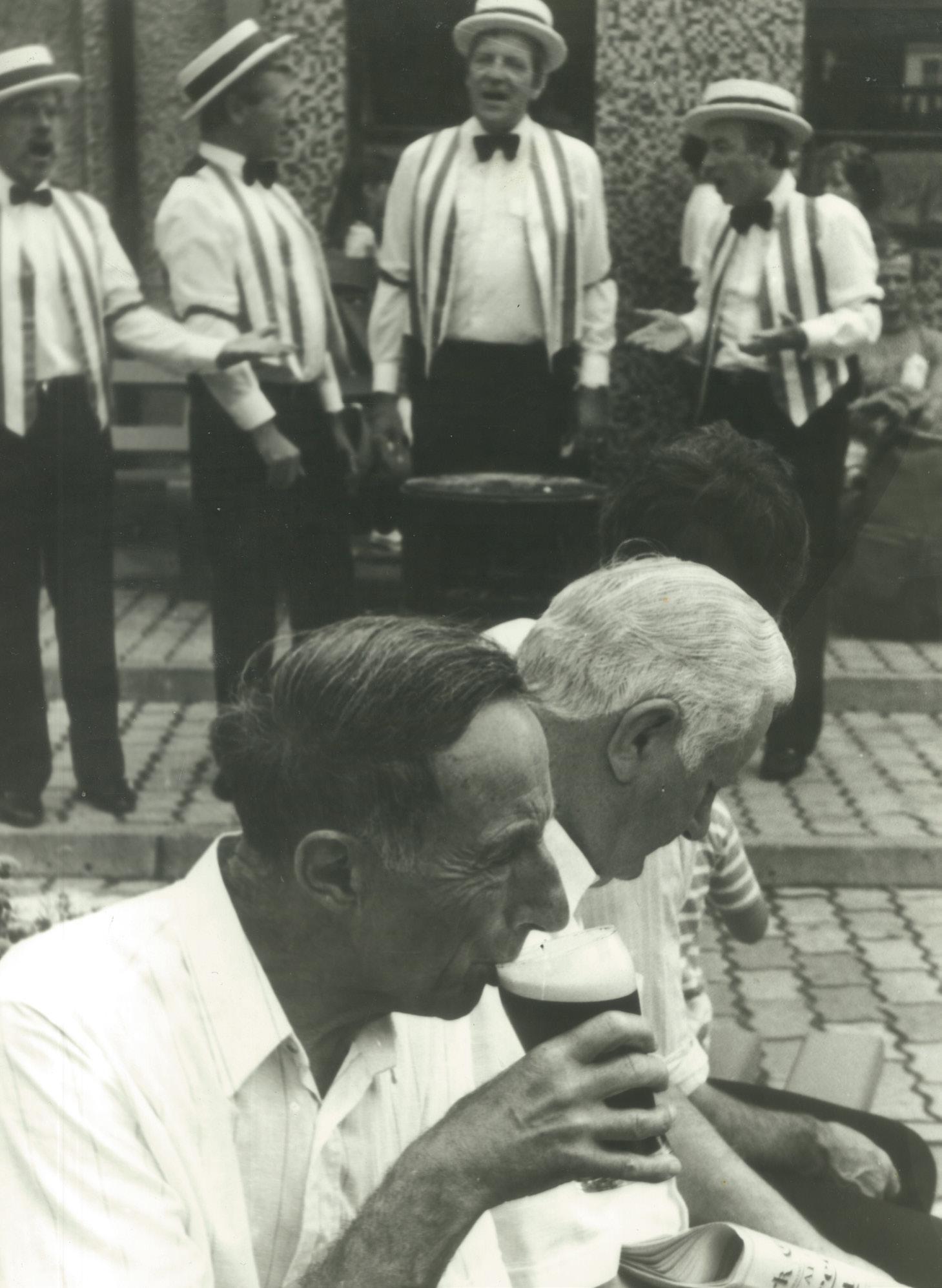

For this Anniversary Issue we have trawled through archives of Icarus past, revealing a copious number of advertisements for Guinness incongruously published alongside the work of the writers we grew up on. A selection of this work, ‘From "e Archives’, closes this issue.

And then there was ‘ "e Drawer.’ ‘ "e Drawer’ was a big, bad scary drawer in the publications o ce on campus that was big, bad and scary because of how disorganised it was. "is disorganisation rendered its depths impenetrable for a time (paper was jammed in the door).

1 Alec Reid quoted in ‘On the wings of Icarus,’ !e Irish Times (2010).

2 Icarus, (1998).

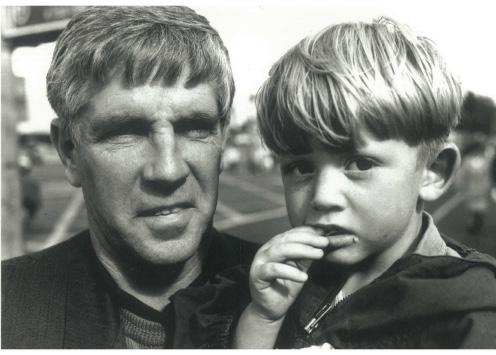

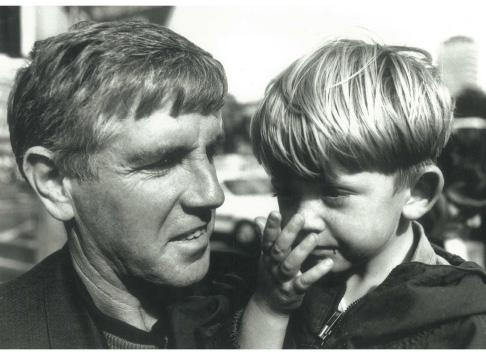

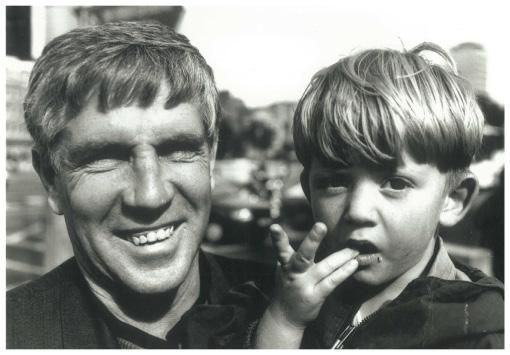

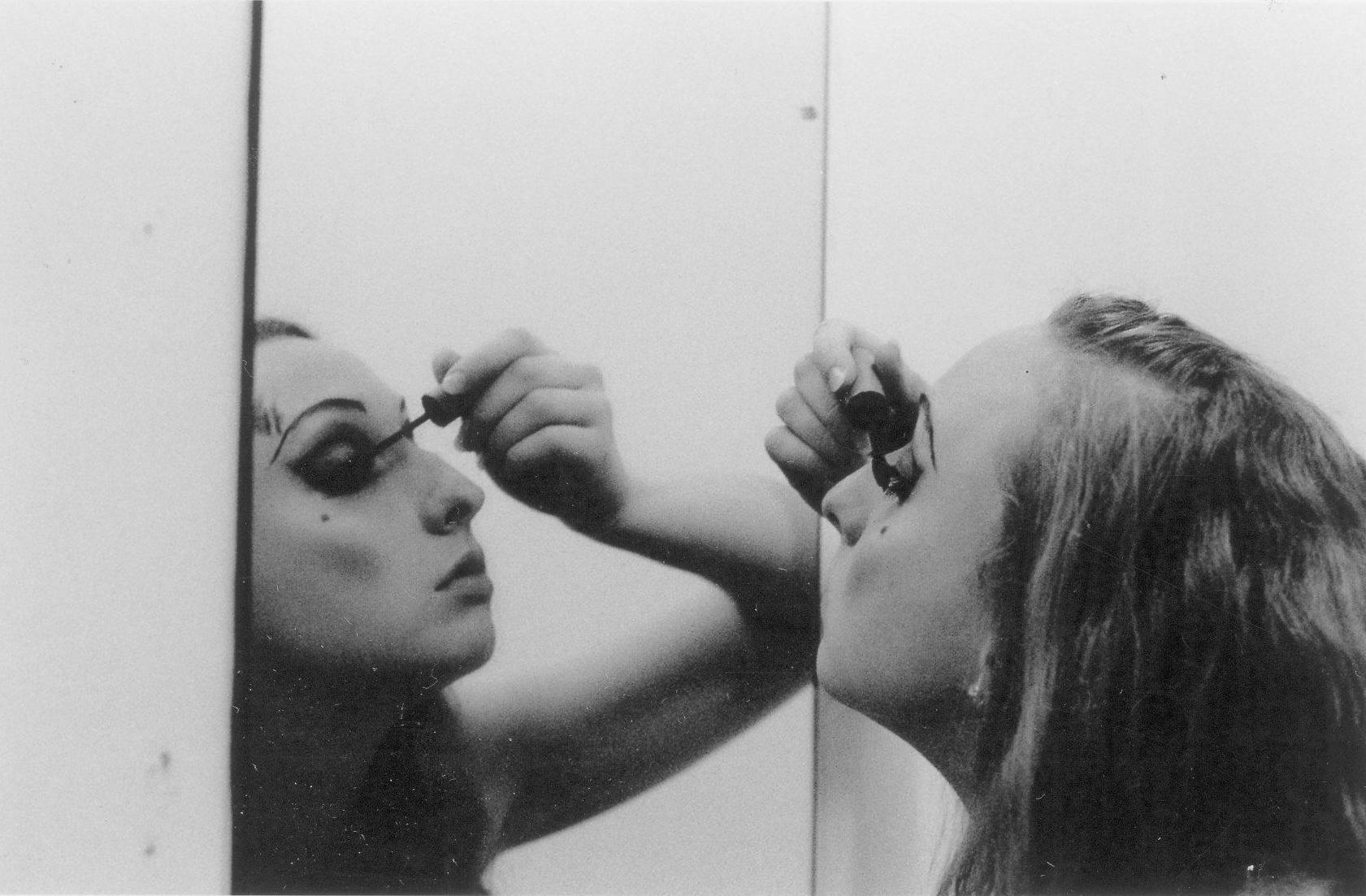

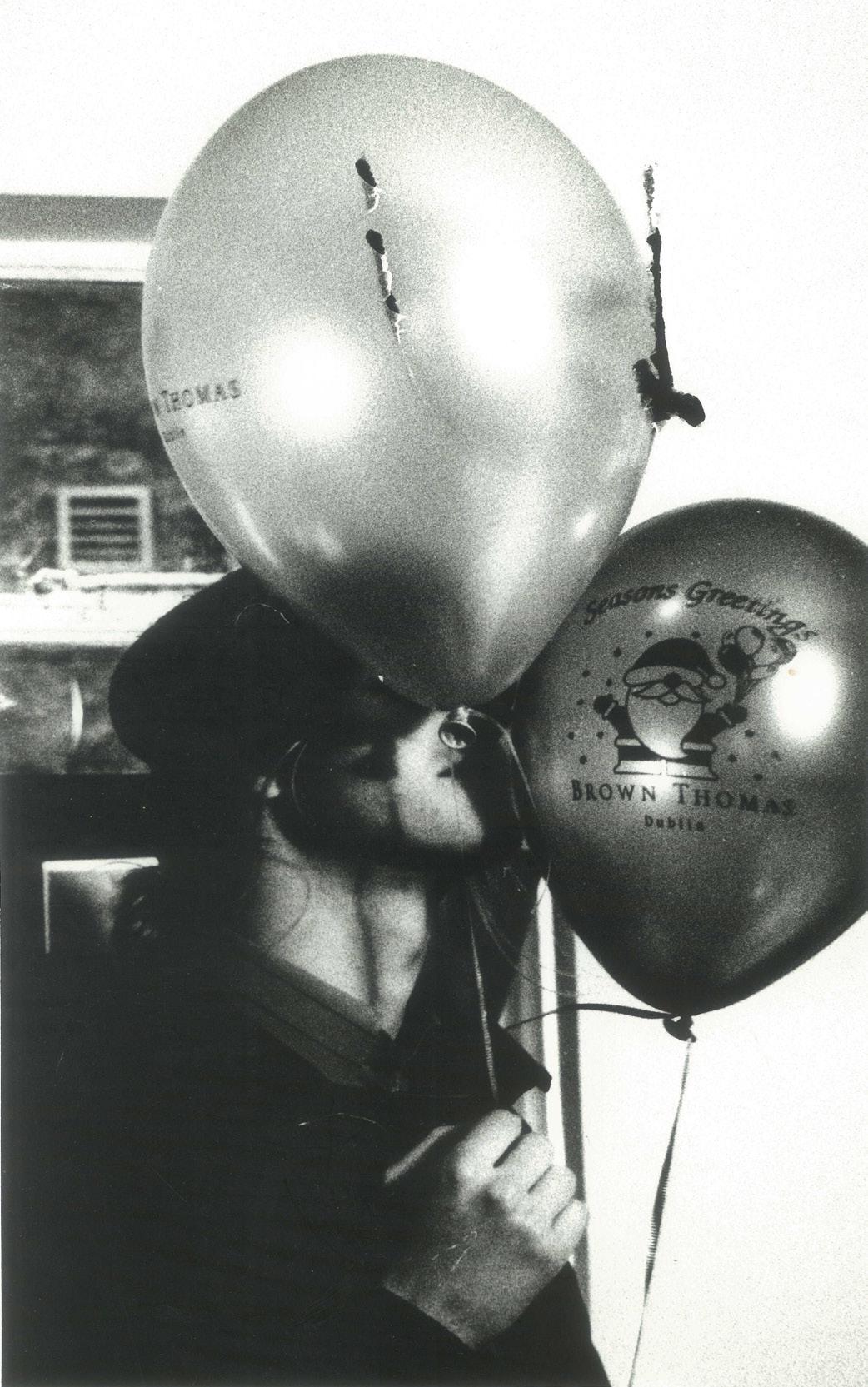

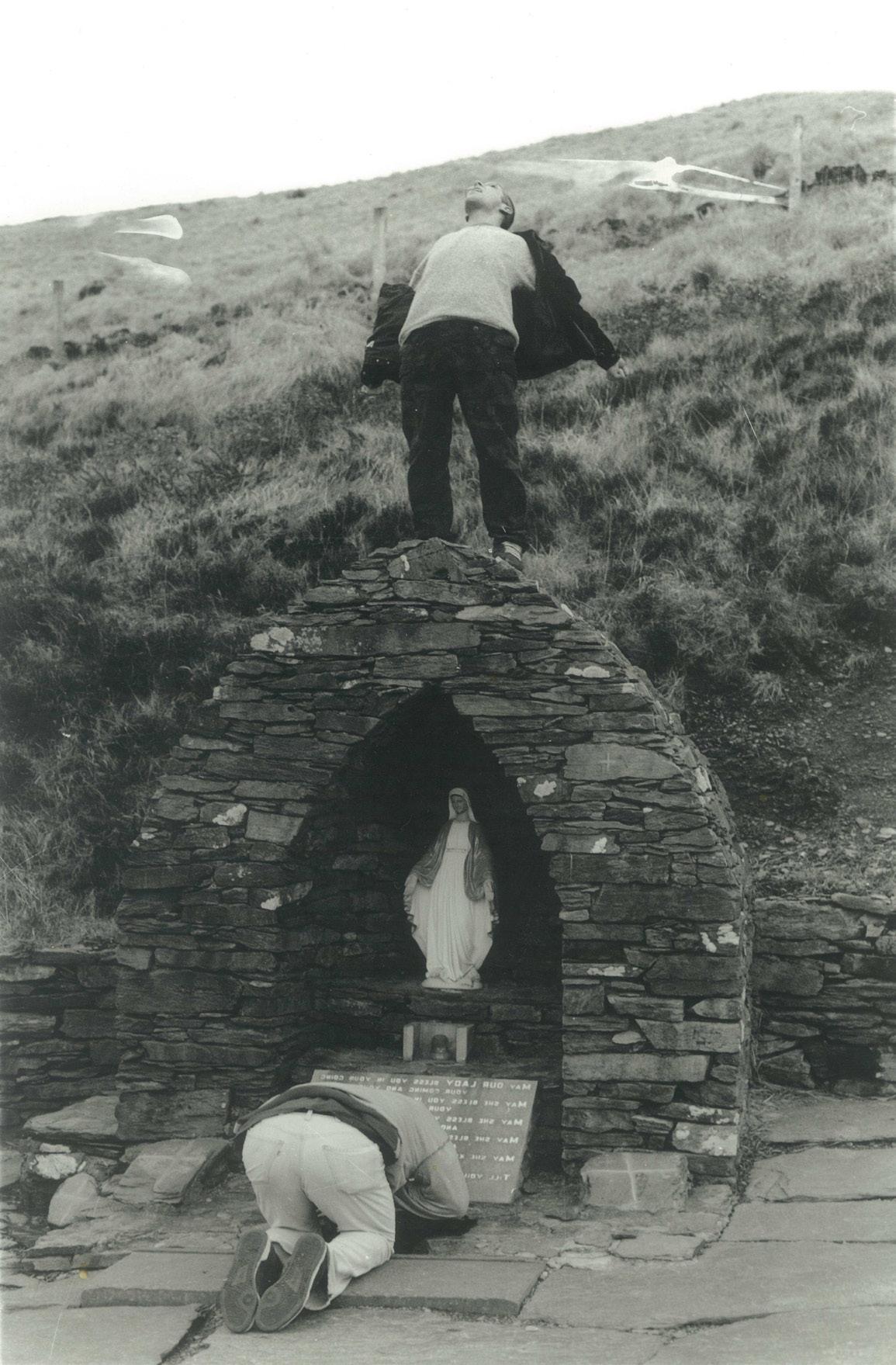

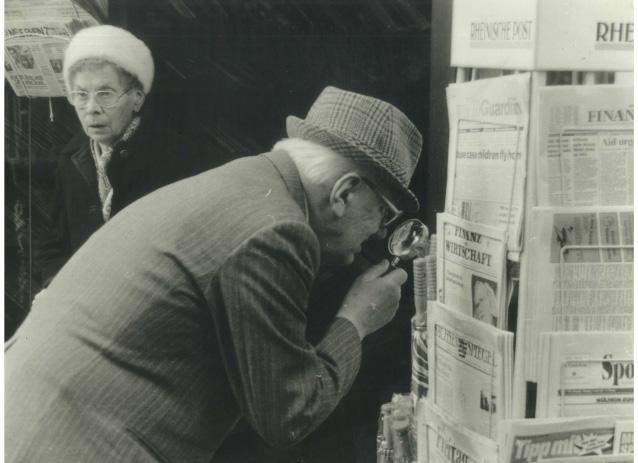

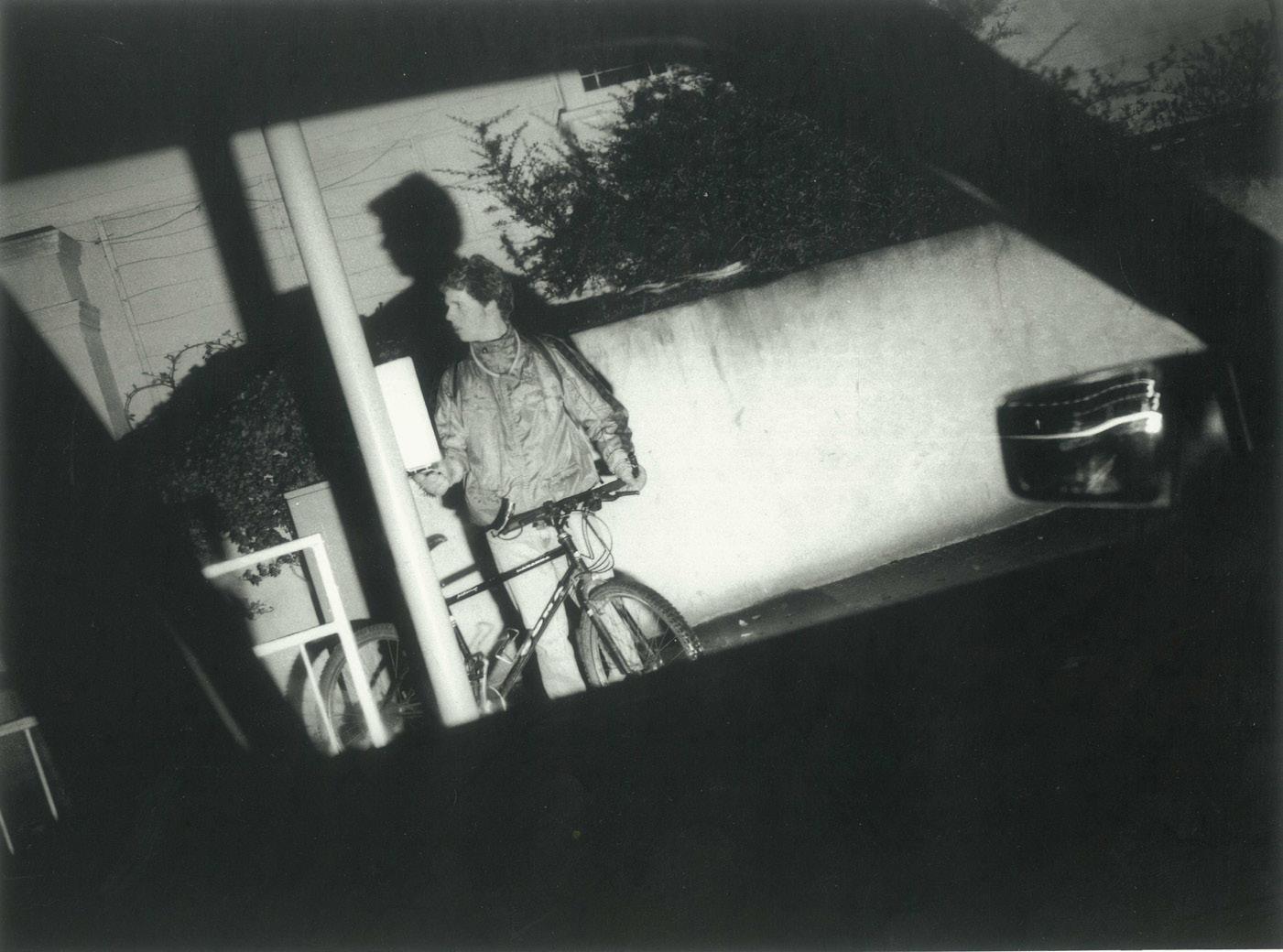

Eventually, when the drawer was busted open and we could parse through its contents, we found that it contained some rare gems — black-and-white photographs of unknown origin, some of which had been previously published in Icarus, some of which had not. Whilst we have done our best to attribute credit to the photographer in instances where possible, it remains that some of these photos were captured by eyes unknown. In this instance, you will see the photos labelled as ‘From "e Drawer.’ We hope not to have done any artists a discredit in taking this liberty; the art was too strong and the history too vivid for us to forego publication.

For us, this past year has involved a lot of time sitting in the dreary publications o ce, watching the sun spin away and talking till the cows come home. We are, undeniably, rather di erent people who have somewhat di erent tastes. Lou writes poems that rhyme; Cat does not like poems that rhyme. Sometimes we agree and sometimes we don’t; oftentimes we can anticipate how the other will react before they have even reacted. "ere are few greater intimacies than this.

Editing Icarus has demanded more of us than we expected, but it has also given us far more in return.

In your hands is our very best attempt at recording the past whilst allowing it to soften into the future. "e present is somewhere in there too – no wait, it is here, it was there, it is here once more.

Slán, le grá ó,

Cat & Lou.

A note from David Norris, civil rights activist, former senator in Seanad Éireann, and scholar.

"I was honoured to have been invited to take over the Editorship of Icarus in — I think — 1967. It was a remarkable journal and published the works of various writers including my friend, the late Brendan Kennelly. I send my congratulations on the 75th anniversary of Icarus."

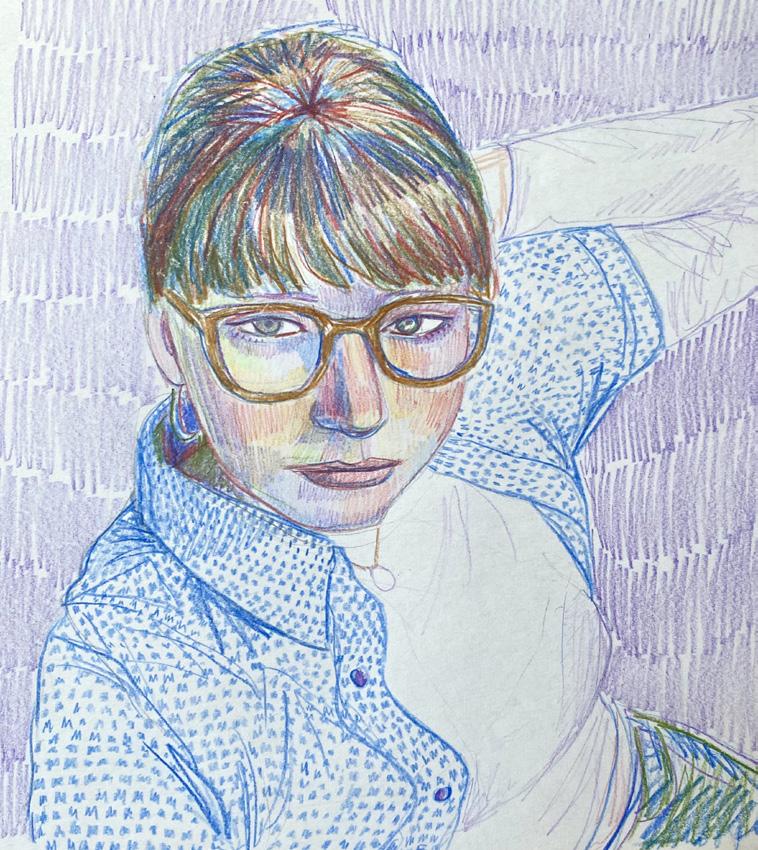

from e Drawer

Do you see it Jo?

O'Leary

"ere's something down there, it's getting closer to us now, you'll see it in a minute.

No, no, don't be afraid, Be curious be excited

Feel the wind gaining speed now as we hurtle against it. It's hitting o the dust, bounding up to the stage, "e hum grows louder, it hums, huMS, HUMS.

Allow the vibration to fuzz your ears and whet your wits.

Do you feel it Jo?

Take my hand and we can go together if you'd like?

Soon we'll be running but don't worry, You've built up enough strength in your bearing. "e sweat under our arms and sticky in our palms. We've pushed and pulled and yearned and reached. Take in an early-morning bird-song breath. You've earned it.

Do you remember Jo?

Sing the songs that you sang in the depths and think of how far you have come.

Tomorrow in the change of it, we ride until dawn

Until dawn I say and straight on 'til morning.

Listen to the leaves bustling and remember that they have always done that.

e Trough by Éabha Calnan

Little wasps held

In foetal position

More buoyant, now

My hands want to trap "e water — keep it in their hopeful cusp,

Sliver-gaps 'tween ngers

Like light spilling "rough shed-panels

Cradling cow-breath

As hair bleeds brown And deeper we lean

Let me hold you as you laugh

Feel the rumble of your chest

It will almost be the same

Still, sing sweetly to me

Soft vibrato in the mornings

Let me see you say my name

Whisper to me, in a crowded room

Bury me in platitudes — Odes to all I stand to lose

Katie Carrig

You're petri ed of spring — "e way it arrives uninvited, clothed in light that feels like exposure. Pollen collects like secrets on windowsills. Peonies bloom too violently to be innocent.

It's Good Friday, but the calendar is just a mirror, And you can't stop looking. You wear guilt like a second skin, thin and blistering in warm weather. St. Patrick's Day lives in the marrow. A green too bright, a hallway that folded inward, And something broke in the hinge of the season.

You were found, but not gathered. In the recurring dream, you are the wind, but the wind remembers being a body.

You ghost through locked doors, speak in a dialect of drafts and trembling shutters. Sometimes, they shiver in reply. You carry the world across itself, folding it like paper, creased and worn, Always on the edge of tearing.

You are somewhere else entirely — You are somewhere between. A soundscape lives in your lungs: Radio static, bells underwater. Not language. Not quite music. But something like unraveling.

from e Drawer

Jules Nati

Your crooked, baby-toothed smile "ought he’d seen his re!ection In my braced, pimple-ravaged face. You made me captain Wendy Of our duvet-sheets ship Because I knew, I was older.

You really were convinced (You told everybody who’d ask) "at I had been eighteen my whole life, Ever since you were born. But I don’t remember it as a lie: I was a child only until you came to life.

So if you’ll want to splinter your st Against the glass you made of me, I in a million pieces at your feet Will look back at you and apologize I made you bleed all over me:

Ontologically, all I know is How to watch over you.

He watches Mom comb our hair into grids, sweeping each one for nits, eggs, mothers, pulling parasites down long, anointed strands with her thin blue teeth. We do this again and again, wet and dry, Mom unable to win the battle on two fronts at once, so we go nuclear — chopping our thick manes to our two chins, shared haircut cute in kindergarten, social suicide in 3rd.

Long after the lice have died, he continues to creep over to Mom and ask for a lice check. She humours him, running her long ngers along his itch-free scalp, and listens to him hum, mmm.

Yer people sit when they read to us yis are not fazed by the pace of the !ames that glass can’t smash slow when sitting, ye wait, further living, time is a tted sheet only yer Ma can put on the bed. And you (she gestures) are the child, in the next room keep your ear against the wall and listen (she says) aithníonn ciaróg ciaróg eile1 (she says) bíonn an fhírinne searbh2 my mother can’t speak irish but I’m her little beetle far far away from here your city is in waiting (says not my mother) your city disagrees about messiahs your city is a puddle and the Messiah is a beetle.

After every show you listen for the river stared down and saw your beetle city; centre: liquid, crunchy shell, beaten, peeled, and clattered fast left to sit like scum on quays; re!ections of tenements with chitin strained from growth spurts,

1 ‘ "e beetle recognises the other beetle’, like recognises like 2 ‘ "e truth is often bitter’

lamplight! quiet! (must be home from damp) landline’s ringing far away culls the dripping tap and —

you walk too fast; can’t get jumped at my big age.

I recognise you, Beetle — is ciaróg mé, ciaróg eile3, listen, Beetle, for the world in the next room, Beetle needs nostalgia. Beetle needs noise. Beetle wants it brand spanking new.

I am afraid that after all this waiting the Messiah will be too tired after all this sleep, exhausted after all these words with nothing left to say it’s not really freedom if you’ve colonised yourself —

and Beetle says be happy but what will we do then?

3 'I am a beetle, another beetle'

Alannah McElligott Ryan

I learnt how she ts the plates, bowls and mugs in the su ocated cupboard over two hundred and fty two moons. I love when I notice something out of place, because you’ve tried, and maybe thought you’d got it right, but I know whose kind hands put away her ceramic blues.

Lluís Cuesta

the boy commences the rite — he takes the bread and peels its crust, revealing the heart of wheat. it rests in his lap, wrapped in a handkerchief, and he pauses, murmurs to it solemnly: "idle thing, more than idle: wayward, poor warm perfume baked clay, orange tulip, he presses it gently. "forgive me, snow-rag, !ame-rag, scent of my mornings lord of loaves, at last, my hunger nds comfort.

from e Drawer

by Charlie Swan

"e church is a spire

Splitting the sun in two.

My mother is a well of worry, Balancing the duties of cleaning

Our khakis and drawing permissible Amounts of grief to the surface.

"e priest is a stranger.

"e wafers are bland.

"e man on the cross is a tribute, A man who beat death — For a boy who chose it.

His sister reads a poem Of a spritely bird Carrying the moon.

And his mother — His mother is a slackjaw heart Swallowing in nity. Managing the memories she can.

Bodies by Fay Santillo

"e bath was so big because your dad was meant to t in there, And you found a beetle once by the sink, You thought it would crawl into the water pipes, His long legs contorted into the brink of the tub.

Water pouring wayward, you made yourself Small as the water rushed out of the house, "e branches soaked and cloying,

Ground engulfed and every creature taken out of the earth Floating haplessly in the murk, A raging Noah’s Ark scene, Ceaseless marine storm.

I thought about taking the train across to Cork, Great expanding whales Shifting the weight of their blighted sea, "eir bodies, their colossal blue tears.

Beetle glare of night incessant shining, In pain I learn not to betray myself again.

School by Maike Bergfeld

"e guys are laughing at me. I’m drunk, and 15, so I laugh too. Her cross is hitting my face: it’s the same sound of Feet shu&ing against the !oor, Heavy breathing in the dark room.

‘We are all God’s children’ But then he looks at me and I feel the exception breathing down my neck.

‘God is forgiving’ But then he cries at me and I have to comfort.

Years will pass.

‘Do you want to speak today?’, he’ll ask. I try, and it is drowned by "e people singing in the square.

Gráinne Condron

Closers yanked night down and a buncha femmes in long white skirts with girlfriends' nice-suit-ties 'round their noses grip, mottled tetanus edge of trough and conjure memories of dance class, summer camp, and running from the guards.

Some just smoke a fag / crack their knuckles / take a long inhale then are lowered into vast vats to retrieve a garden worth of sunshine squash, sweet and battered apples, reams of kale so dark it could’ve come from the underworld; seasoned with the wisened ngers of Kurt Cobain himself.

When the plague comes: wasps or rats / the manager; they !ee, and play hyperpop on the march home rummaging instead through skips,

no leader — but no pockets full of can tabs for the tattooed barista, raspy tulip of an intern, or the sly-eyed, middle-aged dental hygienist, instead,

crowding ‘round a mouthy bleached-blonde tomcat with singin’ bells and safety pins hangin’ outta ears perched against litter trays! pillow case! stacks on stacks! and being adorned with mildew curtains, lampshade headdress;

pelting bouncy balls at passing tra c.

Who in the morning, dresses for work with grubby eyes and phantom ring of chocolate ‘round her mouth (kid after a midnight feast) and dons a !eece with unpicked hem, lanyard, black socks only.

Who all through the day, listens to the traphouse beat of barcode bleating.

Which if she listens closely at shift’s end, starts to sound a little like whispers from the alley.

Niagara University, 1964 by Violet

Flanagan

"eir crimes were Irish, Irish, and polio.

"ey all pled guilty, then bought a few cans. "ey rolled Brady down the hill to the creek, Beer dripping down their backs, sweat beading on the soil.

Of course, nothing went as planned. John went to trade school, Rian joined the service, But Brady went all four years.

A womaniser with no use of his legs, Looking up waitresses' skirts, Graduated with honours in ‘68.

His father went down to the dorms one day, Asked to see Brady’s roommate and ‘the other fella’ Who turned his son into an alcoholic.

"ank you was all that he said.

"e day Brady died, Rian was !ying over Taiwan in an A-4 Skyhawk. He made it home with a good fty more years in him. "e day Rian died, John looked up and up into that great blue eye We all play under.

With time they had changed at the centre. God gave them wives, children, some sense. But looking back on it all, who could say what was lost?

"e days bled into each other and made memory a pipe. When John met God it was a drunken reunion. "ank you was all that he said.

Paula Meehan

Paul Lynch

Catherine Prasifka

Makris

Eoin McNamee

Louise Nealon

Paul Durcan

Gustav Parker Hibbett

"is spring and last, in a bright room in a small village near where the boy fell out of the sky, I had a good spell of making poems. I o er some of the work below, as my contribution to celebrating the longevity and the survival into the digital age of an ambitious literary magazine named for a boy who fell from the sky.

— Paula Meehan, Baldoyle, Dublin, 12th July 2025.

I want to grow old in an island village. A small house, the cli top road, where the sound of the night sea climbs up from the rocks below until my dreaming breath is in sequence with the rise and the fall of the swell; where the sun in the morning early will already have warmed the terrazzo !oor. "ere on a súgán chair sits

Rainer Maria’s angel at his new elegies, wrought of woodsmoke, thyme, honey of the almond. "eir blossoms are drifting to the terrace like snow and all of them rhyming in the future tense. He’ll preen his blue feathers as soon as he’s done, stash his new work in his boxes of charms, labelled Hopes, Hymns, Wings, Tools, Anything Else "at Fits.

Rosarium by Paula Meehan

"e scent of the wild dog rose brings her back, my grandmother Mary in her rose garden, her rosary of bone an in nity loop on her lap. Her life no bed of roses, she tended her soul garden as ercely as she dug and mulched and pruned, as she cut the earliest blooms for her May altar.

‘I’ll keep you on my beads’, she’d tell her daughters as one cruel decade they took the cattle boat to far o nineteen fties England, set free from the elemental shadows of the house. She was all intercession and sober truths and dead the year I reached the age of reason, heir to her cups, her coins, her swords, her wands, her cards.

— erma, Ikaria, 29th of May 2025.

from e Drawer

Last night in a dream I was skinned, stu ed, posed, my pelt mounted on an armature of willow in a workshop down by the Li ey’s green water. "e skilled taxidermist, patient and thorough, let slip I’d be shown in a museum cabinet: myself and a corn bunting, the last of its birdkind who sang in its day from treetops and hedgerows

over lowland stubble though heaven above knows, little wingèd one, why our fates are so entwined. What you mirror of me here my migrant nestmate — what is angelic, my plumage, my dialect — is borrowed from my dream. Let us be mother or daughter to each other in this dream vitrine. "ey must allow one word, one word only, to catalogue, to name us — lost.

Paula Meehan

Enshrined

by

Paula Meehan

‘Get those kids out from under my feet or I’ll swing for them’. My mother at the end of her tether those long-stretched rainy Sundays of our childhood and I am following my father’s footsteps again through the city streets to the Galleries, the Museums. I track him now in memory, my lonely father as he makes his own way through the new Republic.

"e stories he made up, whether comic or tragic, fanciful or true, would spellbind my sisters, my brother. "rough the high ceremonial doorways, room after room until the youngest, worn out, cranky, his little hen, was hoisted up on his shoulders, ice-creams promised, for the long trudge home to my beautiful mother, to her empty mirrors, to her far-o dreaming.

— erma, Ikaria, 28th of April 2025

We sat in the sun — My brother and I channeling tide into moat, My mother with a book by the windbreaker, My father parting sea, a slab-chested colossus, My sister yet to complete us.

"at beach is now gone — "e dunes scoured into retreat, "e strand a rubble of piping, "e carpark e aced to a headless road, With nowhere to turn.

from e Drawer

Catherine Prasifka

She has a weight in her chest, one that makes it impossible to breathe. You could call it being 21 and unsure, struggling with the same things all 21 year olds struggle with. "ings that are left behind and forgotten once your frontal cortex nally decides to turn on. A boy she won't remember, the un!attering folds of her body in a photo posted online, if she will ever amount to anything, if she is deserving of love.

She messages her friend, not knowing he won’t be her friend for much longer: I feel like crying. All the time. I imagine the reply: same haha. "e kind of self-centred post-ironic fatalism that was funny at the time. But the reply has been tossed out as well: the cry for help is the only thing that has stuck in my mind. It is lodged in there, deeply, and I am constantly poking at it, wondering at the damage it is hiding.

"e girl is being crushed by the weight of constant communication, but it will take her a long time to realise it. I grew up with the internet as a near-constant companion. First, with a desktop computer, then my iPod touch (gone but not forgotten), then nally a smart phone.

Something unique happened when unlimited data became the norm, something that came to a head that spring. It seemed amazing at the time: no longer tethered to a location, or at risk of running out of credit. She could have the internet whenever she wanted it. And she wanted it.

"is is the moment the internet stopped being a place I could visit and became something that inhabited me at all times, like a parasite. "e girl is the last version I have of myself before I became remoulded by my new reality.

"e girl is unhappy, but she doesn't know why. When she receives a message, she must reply. Everyone knows that her phone is always in her hand. She does not want to risk them thinking she is ignoring them. Her phone has opened her up to a constant stream of emotions coming from

everyone around her. "ere are so many people pulling at all sides of her, there is no room left for her.

"is may seem dramatic. But what you have to understand is that that girl was the subject of an experiment, as we all currently are.

Suddenly, opening up before her are thousands of micro-interactions containing data points she can map into constellations. "ings she may never have noticed are laid bare in screenshots and the length of time it takes someone to reply. Her private space is evaporating before her eyes. And she is still learning how to be a person, how to interact with the world, how to follow and digest social cues.

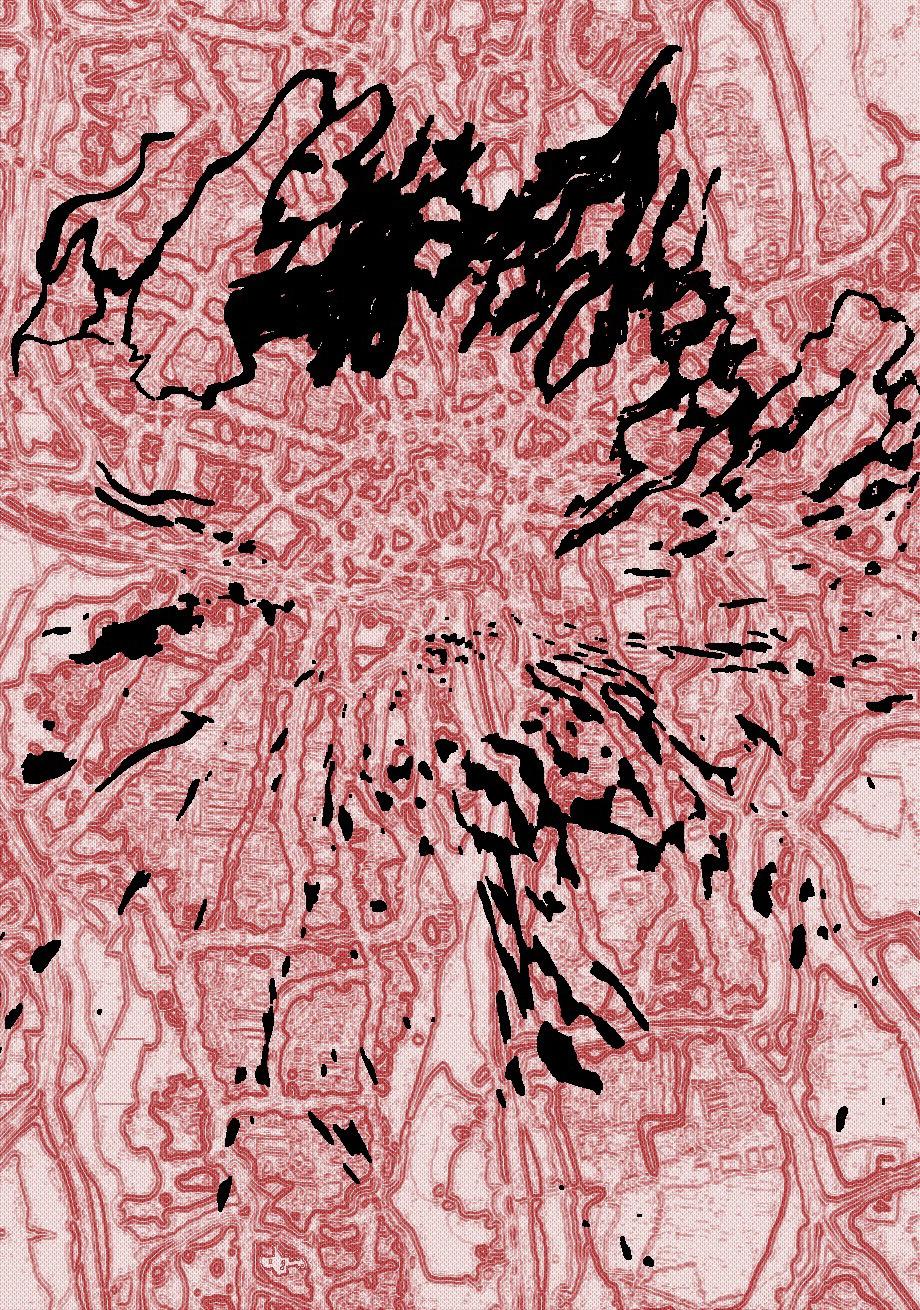

Excerpts from nobody is going to be unique by Christodoulos

Makris

what's the language of travel focus on this fragment ltered through codi cation meaning the world to me

the totality of truth suddenly dissolving into Latinate nights in foreign forms & sounds

young meat banging next door lming a porno keeping me up to date Alice would you like to partake in elongated forms

besmirched now awake someone drawing your face in extreme simpli cation co ee cake amphetamines

terminal experience something to hang your gaze on

cancel puritanical curated poems spilling out of their forms out of what came and gone beyond pink

and into the red data cation lets me visit scans my retina

& here comes dada a Diário de Notícias rainbow hip hop connotations much obliged

I nearly revealed myself an incandescent t a letter of complaint hope to god it won’t surface any time soon unless a cloud bursts a key malfunctions trust breaks memory unravels

hallucinate stranger on the motorway as hip hop shows sampling an atmosphere corrupted in !at terms beyond braggadocious or broken re!ective observation

wonder why his playlist is all men except a glimmer appears now a voice a thread now operatically beautiful old skool nineties house oh the cream elds

it’s not that I don’t sense humanity but if I don’t nip it in the bud as shown in predictable commotions within groups of the hormonally charged perhaps it’s the age gap

it’s not that I can’t go into a reverie piloting subtly ignoring relayed information from !ightradar pretend I can hear a way forward that’s clear it’s the aircraft we’ve captured the geography the sports science

perhaps it’s right at that hyper moment perhaps I carry it right here in my heart and across from and to my everywhere devices even while unconnected I, bring it I, can I replicate the moment of course I can watch me

Excerpt from e Bureau by

Eoin McNamee

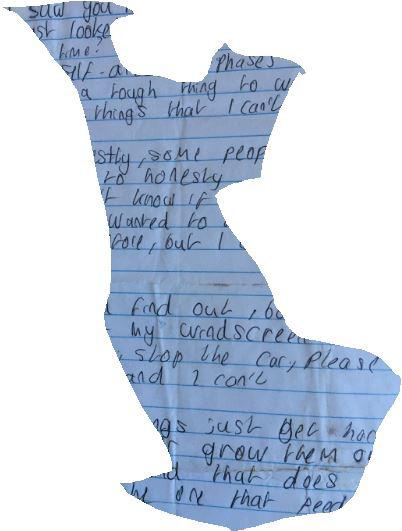

Fragment of letter from Paddy Farrell to my father, Brendan McNamee, May 1983:

CORK PRISON CENSORED

Patrick Farrell

Cork Prison

Rathmore Road

10 NLG 1983

2 NLG 1983

Dear Brendan how are things out there. I just thought Id drop you a few lines as its sunday here and we have plenty of time on our hands. Well rst of all I want to thank sweeney for coming up tell larry also. he can drop me a line if there’s any queries regarding anything. You need not show him this letter. I wonder how they got on with that business that I had arranged with your wee man. Any word from him? Did he come to see you. What do you think of this business Brendan that I’m supposed to be involved in. I think it might be a good idea to try and get proof of where I was between those dates that were mentioned. What did you think of that barrister. I suppose he’d be good enough for the trial I meant too have a chat with you the last

End of letter fragment.

"e letter is the only evidence that these things had indeed happened and they happened in the way I describe them. Some stories seem to tell themselves and other stories wish to remain untold. It is uncertain which this is.

"ey were in an upstairs bedroom. Paddy was naked on the bed. Lorraine was on the !oor on top of the shotgun. "e room becoming its own forensics. Blood spatter. Spread pattern. "e room arranging itself into false settings, looking faked up, tired, frayed at the edges. It’s a girl’s bedroom in a suburban house, shabby, the slippers under the wardrobe, concert tickets Blu-tacked to the wall, the loved spaces. "e things a girl kept on her dressing table, yellow puckers in the varnish, someone has lit a cigarette and left it poised on the edge. You can see Paddy lying on the bed watching her do her make-up, the little inner gestures, the pursing, the dabbing with tissue. Working your way towards the inner self. "at was what all the mirrored cases were about, the brushes and pencils, the clasps and trinketry.

Come quickly. Paddy is shot.

Boyle O’Reilly Terrace faces the back of the Lourdes hospital. "e incinerators and morgues. Two-storey red-brick houses with small gardens to the front. A t-up for a suburban sex crime, for back garden prowlers. "ere are few people walking. An elderly woman, a man with a sports bag, a lone, misdirected look in his eyes. "e houses are red-brick, semi-detached. "e doors PVC with diamond pane inset. "ese are long vistas, you can picture it after dark, the stalked-through night-time streets. "e man with the sports bag looked as if he had packed for this.

At the rear of the terrace is the Lourdes stadium where track and eld events were held. It had fallen into decay, grass growing through the asphalt of the running track, the handrails bent, tarnished. It had been built for those who would be ardent in the everyday, the spike marks still visible on the starting blocks, a rotted singlet on a crush barrier memorial to their strivings.

Beyond the Lourdes stadium is St Peter’s graveyard and St Peter’s church where the mummi ed head of the seventeenth-century martyr Blessed Oliver Plunkett is preserved in a catafalque. Beside the catafalque is the door of the cell where Plunkett was held in Newgate prison before being hanged, drawn and quartered. "e road that runs along the back of these buildings is known as the Twenties.

Paddy is shot. Lorraine is shot.

"ey were found by Lorraine’s stepfather Dessie Wilton. He had returned home for work with Peggy Farrell, his common-law wife and Lorraine’s mother, at teatime. "ey saw Paddy Farrell’s burgundy Mercedes 320SL parked outside. Wilton said they watched a football match on television in the living room downstairs, although the Irish Independent reported he had earlier looked into the darkened room when they entered the house and saw what he thought was Paddy asleep on the bed. "ey could hear Paddy and Lorraine’s mobile phones ringing upstairs.

from e Drawer

Excerpt from Everything at is Beautiful by

Louise Nealon

It happened, along with the rest of her childhood, on the Foleys’ farm. Ten years old, trying to impress Peter, who had two years and four inches on her. "ey were both running for a ball and Niamh knew that they were going to swing at the same time, the way she saw the men do on the telly. She heard her father’s voice in her head telling her not to hold back. As her feet left the ground, it felt like !ying, even as her temple collided with Peter’s shoulder and everything went black.

It was the kiss of Tayto, the border collie, that brought her back to life. She batted the dog away and got up from the ground, cradling her hand and moaning in pain. Peter shushed her. "ey weren’t supposed to be pucking around together. Peter’s mother, Helen, tended to turn a blind eye to their antics as long as they were careful, but they’d sent a sliotar through the window of her downstairs toilet the week before and she was still raging with them.

Niamh got up from the ground and reached for her hurley. It seemed a lot lighter until she realised the stick had snapped in two during the clash. She turned around to see where the bottom half had landed on the other side of the lawn, then took a wild swing at Peter. ‘You b-broke my good hurley!”

She dropped to her knees and started crying. He looked over his shoulder to see if one of his sisters was around. Maria was studying in her room and the other two, Kate and Bláithín, were where they were supposed to be, doing their homework at the kitchen table.

‘It was going to break eventually,’ he o ered. He wiped bits of muck o his runners in the grass while he waited for her to get over it.

‘D-do you think your dad could x it?’ she asked.

"ey were able to hear Liam before they saw him — the gnaw of the bandsaw against the wood got louder when they opened the door of the

workshop. Niamh watched as Peter made tentative attempts to approach his father. Liam Foley was a kind and charismatic man who sometimes seemed to forget that he had children. He was cutting the outline of a hurley from a plank of timber. It was a long couple of minutes before he eventually looked up from his work and turned o the bandsaw.

‘Dad, Niamh broke her hurley,’ Peter said.

‘P-p-p-peter broke my hurley,’ Niamh corrected him.

Liam straightened himself and put his hands on his hips. ‘You’re in the market for a new one so?’

‘M-maybe you could x it?’

‘Let me have a look at it, Niamh.’

She liked the way Liam pronounced her name — nee-av — as opposed to the nasally, monosyllabic neev that most people used, including herself. One syllable was less risky than the two: nuh-nuh-nuh-nuh-neev.

"e hurley had snapped in the middle where she had written her name in black marker. She presented the stick to him in two pieces.

Liam shook his head and let out a low whistle. ‘I’m afraid there’s nothing I can do with that now, pet.’

She concentrated on the wood-shavings on the !oor as her eyes lled up. Liam hunkered down beside her, his hand leaning on the new hurley he was working on. ‘It’s hard to let go of a good one, isn’t it?’

"e tears tripped out of her eyes as she nodded.

‘I can glue it together all right, but you won’t be able to play with it. How about we stick it up there?’ He pointed up at the slanted roof of the shed and the display of hurleys nailed to it — hurleys that Liam and her dad had won county championships with.

‘Hey!’ Peter cried. ‘ "at’s not fair! She didn’t even win anything!’

Liam winked at her and spoke so quietly that Niamh had to lean in to hear him. ‘How about you promise me that the next time you come to me with a broken hurley, it’s one that belongs to that lad over there. We could do with putting some manners on him.’

Niamh beamed at him.

Liam turned to his son. ‘Well, are you going to help me make a new hurley for Niamh or are you too busy sulking? You might even get a new one of your own out of it.’

Peter’s face brightened. Liam Foley was famous for making hurleys.

Only a select few were invited into the inner sanctum of the workshop. Part of the reason why Peter and Niamh played in the back garden was for a chance to run into their heroes — men who played on the county team walked through on their way to pick up hurleys from Liam and sometimes joined in on their puck around. When no one else was there, the two of them spent hours sneaking into the workshop and sifting through hurleys, trying to nd the right weight and balance to suit their game. "ey scarpered whenever they heard anyone coming, only taking one hurley at a time so that it wouldn’t be missed.

One of the nicknames Liam picked up throughout his years on the hurling pitch was Father Foley because everyone thought he would make a good priest. "ere was something monastic about the way he moved through the world. "e workshop was his sanctuary, so even the thought of sneaking in to rob hurleys was sacrilegious. It felt like stealing from God.

Niamh was sure Liam knew what they were doing, but it was more fun to pretend to be thieves — the rush of adrenaline they got when they made their getaway made them giddy and red them up for another round of tearing into each other on the lawn with their new weapons.

‘You’re about to have your rst lesson in where hurleys come from,’ Liam said, rolling out the base of tree he used for when the television people came to lm him for a documentary.

‘ "is,’ he said, leaning it into the crook of his arm, ‘Is the bottom of an ash tree. Not all ash trees are made equal, and so not all of them are suitable for making hurleys. Only the chosen few that have a bit about them make the cut: they have to have these lovely toes.’ He twirled the stump around to display the knobbly bits protruding from the trunk. ‘ "ese fellas are what give you the natural curve of the hurley when we saw into them…’

Niamh and Peter knew that they had to su er through the sermon in order to get to the action. ‘It’s important to keep track of the mammy and daddy trees,’ Liam continued. ‘You can even take the shoots of an ash tree from Tipperary and breed it with one from Clare, like an arranged marriage. And from those good roots, you can make even better ones.’

Niamh felt her nger throbbing. She hadn’t noticed that she had hurt it earlier. She tried to bend it and she !inched.

‘Show us your broken hurley there Niamh, like a good girl,’ Liam

called to her, and she gave him the two pieces of wood. ‘Now the reason I can’t x this is because of where the break is, in the very centre — it’s for the graveyard. But if you broke it down the bottom here at the bas, we could work with that. You see, the grain goes all the way up the stick — straight the whole way up the handle, but when you get to the bottom of the hurley, it curves. "at’s what gives the hurl its strength — the bend in it.’

Niamh followed Liam’s nger as he traced the wood grain.

‘Nothing and nobody can exist on the straight and narrow,’ he said, smoothing his hand on the hurl like he was petting an animal. ‘Try to live a straightforward life and watch as it splinters into smithereens.’

Peter kicked the sawdust at his feet and waited until Liam clapped his hands together to signal that it was time to work. Liam brought them to the back of the workshop where stacks of planks were drying like giant towers of Jenga.

Peter was quick to obey Liam’s commands, handing him the requested tools with the reverence of an altar server at mass. He wasn’t often allowed to help Liam in the workshop. His older brother John was sixteen and had done four years of woodwork in secondary school before he started to learn the trade.

"e outside world felt far away. All that mattered was the grind of the machines and the scratching of the tools they used to bring their sticks to life. "e metal was still warm from Liam’s hands when he passed Niamh the spokeshave. She hesitated, conscious that Liam was watching her.

‘Always go with the grain,’ he said, eventually, clasping his hands over hers and pushing down on the handle of the hurley in one swooping motion. A long strip of timber fell to the ground in a gentle curl. ‘Never against it.’

He let go of her hands. Niamh was surprised that she could keep going on her own, shaving strips of wood away. She was about to give the hurley back to Liam when he caught a hold of her nger. A dart of pain !ew up her arm. He examined her swollen knuckle, and turned the palm of her hand over in his. "e back of her nger was mottled purple and black.

‘Where does it hurt?’ he asked.

She shrugged. He asked her to bend it. She took a sharp inhale of breath and found that she couldn’t move it at all.

Liam left the workshop with them, leading them up to the house.

He ushered them into the kitchen to wait for Helen to assess the situation. Peter handed her a bag of frozen peas wrapped in a tea towel. ‘ "anks,’ she said.

Niamh felt a pang of panic as she realised that she was going to have to explain what happened to her mother. Mary didn’t like hurling, or the Foleys for that matter. Niamh didn’t stutter as much when she was around the Foleys. She only felt her throat tighten when her mother came to collect her. She had developed a habit of smiling instead of talking, which Mary encouraged. ‘You don’t have to speak if you don’t want to,’ she said. ‘And you don’t have to tell them every last thing that you’re thinking, either. Sometimes, it’s best to say nothing at all.’

Niamh heard Helen’s footsteps coming downstairs. She came into the kitchen with a basket of laundry on her hip, blowing her fringe out of her eyes.

‘What is it now?’ she asked Liam, before spotting Niamh sitting down on the chair. ‘Oh Niamh, lovey,’ she said, crouching down on her hunkers. ‘ "at’ll need an Xray.’

She sighed and went to get her car keys. ‘Liam, will you let Mary know where we’ve gone? It’s probably a fracture.’

Niamh skipped into the car with Peter, relieved that she wouldn’t be there when her mother heard the news. "ey waited for hours in A&E. Peter sat beside her in the waiting room and gave her one of his earphones so that they could listen to Eminem together.

After watching 8 Mile, they had learned the lines to Lose Yourself and had rap battles during puck arounds, using their hurleys as microphones. Niamh was as surprised as Peter when she turned out to be good at rapping — better than him. "e rhythm of it allowed her to break through the invisible force eld that halted her every time she went to speak. It helped that it was someone else’s words that she was saying. Learning lines o by heart was a revelation. She didn’t have to worry about what was or wasn’t happening inside her head.

"e nger was broken. "e nurse gave Niamh a splint and spoke to Helen like she was her mother. "ey stopped in McDonalds drive-thru on the way home. As she tucked into her chips in the back seat of the car, all that Niamh could think about was seeing her hurley on display in Liam’s workshop alongside past legends of the game.

Liam forgot all about the promise he made. Weeks passed and her nger healed without mention of the broken hurley. Niamh tried to ask her dad to remind Liam, but that turned out to be a mistake. Her stutter was always worse when she tried to talk to her father. Vincent couldn’t ignore his one and only child’s stammer the way his wife did. He was so intent on focusing on what she was trying to say, he had forgotten the beginning of the sentence by the time she got to the end.

‘I’m sorry love, can you start again?’

Niamh felt the tears coming.

‘Hey, hey, hey!’ Vincent said, pulling her in for a hug.

She told him that it didn’t matter.

He placed his hands on her shoulders and looked her in the eye. ‘Of course it matters. Everything that goes on inside that curly head of yours matters.’

She ended up having to write the words down. She listened to her dad read them out – he wasn’t good at reading. He left school when he was fourteen to work on the Foley’s farm. His voice was slow and robotic as he made out her handwriting. ‘Peter broke my good hurley – the one you made for me. Liam promised he would put it up in the workshop, but I think he forgot.’

‘D-d-do you think he’ll d-d-d-do it?’ she asked. Vincent squinted like he was able to see into the future. ‘I’ll say it to him, but he’s a busy man, and that workshop has a habit of swallowing things.’ He shook his head. ‘It’s better to forget all about it, pet,’ he said, patting her leg.

But Niamh couldn’t forget about it.

I"at was that Sunday afternoon in May

When a hot sun pushed through the clouds And you were born!

I was driving the two hundred miles from west to east, "e sky blue-and-white china in the elds

In impromptu picnics of tartan rugs;

When neither words nor I Could have known that you had been named already And that your name was Rosie —

Rosie Joyce! May you some day in May

Fifty-six years from today be as lucky As I was when you were born that Sunday:

To drive such side-roads, such main roads, such ramps, such roundabouts,

To cross such bridges, to by-pass such villages, such towns As I did on your Incarnation Day.

By-passing Swinford — Croagh Patrick in my rear-view mirror — My cell phone rang and, stopping on the hard edge of P. Flynn’s highway, I heard Mark your father say:

'A baby girl was born at 3.33 p.m. Weighing 7 and a I/2 Ibs in Holles Street. Tough work, all well.'

"at Sunday in May before daybreak Night had pushed up through the slopes of Achill Yellow fore ngers of Arum Lily — the rst of the year;

Down at the Sound the rst rhododendrons

Purpling the golden camps of whins; "e rst hawthorns powdering white the mainland;

"e rst yellow irises !agging roadside streams; Quills of bog-cotton skimming the bogs; Burrishoole cemetery shin-deep in forget-me-nots;

"e rst sea pinks speckling the seashore; Cli s of London Pride, groves of bluebell, First fuchsia, Queen Anne’s Lace, primrose.

I drove the Old Turlough Road, past Walter Durcan’s Farm, Umbrella’d in the joined handwriting of its ash trees; I drove Tulsk, Kilmainham, the Grand Canal.

Never before had I felt so fortunate. To be driving back into Dublin city; Each canal bridge an old pewter brooch.

I rode the waters and the roads of Ireland, Rosie, to be with you, seashell at my ear! How I laughed when I cradled you in my hand.

Only at Tarmonbarry did I slow down, As in my father’s Ford Anglia half a century ago He slowed down also, as across the River Shannon

We crashed, rattled and bounced on a Bailey bridge; Daddy relishing his role as Moses,

Enunciating the name of the Great Divide

Between the East and the West! We are the people of the West, Our fate to go East.

No such thing, Rosie, as a Uniform Ireland And please God there never will be; "ere is only the River Shannon and all her sister rivers

And all her brother mountains and their family prospects. "ere are higher powers than politics And these we call wild!owers or, geologically, people.

Rosie Joyce –— that Sunday in May Not alone did you make my day, my week, my year To the prescription of Jonathan Philbin Bowman — Daymaker! Daymaker! Daymaker!

Popping out of my daughter, your mother — Changing the expressions on the faces all around you — All of them looking like blue hills in a heat haze —

But you saved my life. For three years I had been subsisting in the slums of despair, Unable to distinguish one day from the next.

On the return journey from Dublin to Mayo In Charlestown on Main Street I meet John Normanly, organic farmer from Curry.

He is driving home to his wife Caroline From a Mountbellew meeting of the Western Development Commission Of Dillon House in Ballaghadereen.

He crouches in his car, I waver in the street, As we exchange lullabies of expectancy; We wet our foreheads in John Moriarty’s autobiography.

"e following Sunday is the Feast of the Ascension Of Our Lord into Heaven: "ank You, O Lord, for the Descent of Rosie onto Earth.

I was told once about erupting volcanoes, how sometimes the steam from their cones melts the wings o birds, how you can stand at a safe distance and watch their skeletons fall.

I was told that it’s beautiful— sad, alarming, of course—but beautiful to watch them almost evaporate.

What goes through a bird’s mind in that last instant before the steam, before its mind and body split?

Does it see the steam, the shimmer in the air ahead, and choose, still, to keep !ying?

And when the steam keeps rising, as you know it does, without the bird, does it take the wings with it?

Just inside the track’s concentric circus rings, at the football eld’s head, is where I learned to wear the gaze of other people like a queen wears feathers. Meets, with everybody watching, were the only times I over-performed, always sharper than in practice, always stronger, faster, higher. I took this as a sign from heaven: every step in service of my !ight was blessed. I was going to leave this self someday, construct myself a new one in a world where I wasn’t so constricted. "e Gods were mine to challenge, mine to rearrange. Picture me vain with self-mythology, sweeping, like the all-commanding breath of spring, across red polyurethane, about to do what humans shouldn’t. When I started moving, everything would fall away behind me; nowhere else was this true. I choked on sax solos in band, in math competitions, in soccer when I had my chance to shoot. Yet here, somehow, pressure was a drug I could metabolise. In this updraft, I was !oral, inches from the height my dream school wanted. I’d frayed my hamstring and it wasn’t healing, but surely my ascent was fated. It had been this way a while, and the doctor said he couldn’t understand how I’d been running, much less

!inging myself more than six feet in the air, so surely I would nd a way again. Even at my last meet, when I felt my magic leave me — 3rd place, out at 6’4” — I never saw my failure coming.

Michael Longley

W. B. Yeats

Eavan Boland

Derek Mahon

W. H. Auden

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

John Montague

Paul Durcan

Sebastian Barry

Seamus Heaney

Brendan Kennelly

Éilís Ní Dhuibhne

Kevin Barry

Seán Hewitt

Originally published in 2010

tar nished buttons all have lil anchors — Rudi Holzapfel

Bruce Arnold included two of my poems in the March 1960 Icarus. "e thrill of that reverberates to this day. When I was home for Easter my father read one of them, ‘Marigolds’, and told me it wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. Brendan Kennelly encouraged Tony Hickey, the editor of the next issue, to publish six more of my poems. (In my latest collection Snow Water I have rescued from oblivion the best of these, ‘Tra-na-rossan’, by incorporating all of it into a new poem.) Edna Broderick gave me my rst favourable review in Trinity News. In June of that year I held her hand at the Astor Cinema: Les Enfants du Paradis. We parted as soon as we had come together, she to study a course in Italy, I to a holiday job to a pea-canning factory in England. My father died in July of a terrible cancer. Edna didn’t come back to Ireland until the beginning of October, not many days before my Senior Freshman examinations. Mourning my father and terri ed of losing my new love I had driven myself demented, and went on to fail my exams. I was allowed to re-sit in the New Year. Edna and I picked up the pieces and embarked, without knowing it, on our lifetime together.

Brendan Kennelly and Rudi Holzapfel were the best-known ‘College poets’ (‘sounds like “village idiot”’, my friend Victor Blease said). I was jostling to lay claim to the title when Derek Mahon breezed in from Belfast, fully-!edged, brilliant, self-con dent. I was !ummoxed: one of the best things ever to happen to me. We became (and remain) close friends. As I’ve said elsewhere, we inhaled poetry with our untipped Sweet Afton cigarettes. We smoked and drank like troopers. We read our poems in public for the rst time towards the end of a performance by Kennelly and Holzapfel at the Laurentian Society (a Catholic out t). So intense was my involvement with Mahon that I missed out on getting to know Kennelly better. I now regret this. He seemed to encompass everything that I had been missing. He was culturally astonishing. In my poem ‘ "e Factory’ I pay tribute to his genius: ‘Already the tubby, rollicking, broken Christ? Talking too much,

drowning me in his Hurlygush.’

Joining the editorial board of Icarus felt like a promotion to the o cer ranks. I remember a board meeting where the American poet Cheli Duran criticised obscurities in a poem by Michael Leahy (‘balloons have habits of points’). He was a dapper philosophy student and the most self-assured of us. I can still quote the opening lines of his ‘ "is Particular Cat’. He was really smart and paid his way through college with poker winnings. We took ourselves very seriously, with Rudi Holzapfel, the only poet who was any fun. His lower case whimsy could occasionally be beautiful: ‘tar nished buttons/ all have lil anchors.’ When I became editor I included ‘lullablues’, along with four startling poems by Mahon, and a precocious essay by Edna about e.e. cummings. In ‘Interpreter of Roses’ she wrote: ‘Renew the lost connection between man and the poetry of earth, and a moral universe seems possible.’ I loved the whole editorial process, corresponding with Turner’s Printing Company in Longford, the folds of galley proofs, red ink and blue pencil, hustling for advertisements, !ogging the magazine at Front Gate. Alec Reid gave my issue the thumbs-up but criticised the blank pages at the very end (‘If you can’t get ads, then ll them with info about past issues’) and for over-punctuating quotations in the review section.

I hung on his every word. We all did. An inspirational lecturer in the English Department, Alec Reid was fat and untidy, albino and nearly blind. As he walked he swayed and rolled his head and boomed and laughed. Like adoring little Boswells we shadowed him to O’Neill’s or Flynn’s where he would squat on a stool with his legs apart, his pudgy ngers round a pint, and quote poetry by heart or a monologue about Beckett and cricket. He had been one of the founding editors of Icarus. We craved his approval. Some of us felt anxious when we learned that he was going to review the magazine in Trinity News. Mahon told me ahead of the publication that Alec had singled out, for praise, my poem ‘Konzentrationslager’. For us such news was worth leaking and, now, forty- ve years later, worth remembering. Trinity treated Alec ungenerously. We su ered the slights on his behalf. We were devastated when his young son Michael died in America after undergoing open-heart surgery. Alec and Beatrice had scrimped and saved to take Michael across the Atlantic where the odds were supposed to be

better. We all grew up a bit. Alec’s passions included Edward "omas and Louis MacNeice. Edna’s and my subsequent work on the poets owes much to him. In the tenth anniversary of Icarus (March 1960) Alec wrote: ‘It could well be that it owes its survival in part to the fact that it has so little to o er the ambitious. Claiming little it has achieved much. In its modesty, its empirical approach and its balance, it is very typical of Trinity’.

W. B. Stanford was a world gure, a Homeric scholar, a startlingly handsome man, reserved and grave. His Macmillan edition of !e Odyssey had been part of my mental furniture since schooldays. I was selling Icarus at Front Gate when he approached the table and bought a copy.

‘You weren’t at my lecture this morning.’

‘I slept in, sir.’

‘My lecture was at eleven. Don’t you live in college? Come and see me rst thing Monday morning.’

Lectures were compulsory and I had missed so many he could, with justi cation, have failed me my year. A nail-biting weekend. He scolded me, then smiled: ‘I suppose you think that because you’re a poet I’m going to let you o ?’

‘Of course not, sir.’

‘Well, I am. I very much liked those new poems in the magazine.’

Many years later at his retirement dinner he came and sat beside me after the speeches. ‘If I had my life over again, I would choose to be a poet rather than a scholar,’ he said. I now wish that I had been a little bit more of a scholar. I enjoyed those lectures of his that I did attend. Occasionally he would take !ight. ‘ "e Golden Mean, Ladies and Gentlemen, is a tension and not a dead level.’ He believed that Homer’s poetry had been sung and bravely showed us how he thought it might have sounded. He gave me my one and only distinguished academic moment. In a class on Aristotle’s Poetics he asked me to compose for the following week our own de nitions of poetry. Mine was: ‘If prose is a river, then poetry’s a fountain.’

(To Major Robert Gregory)

Some nineteen German planes, they say, You had brought down before you died. We called it a good death. Today Can ghost or man be satis ed? Although your last exciting year Outweighed all other years, you said, "ough battle joy may be so dear A memory, even to the dead, It chases other thought away, Yet rise from your Italian tomb, Flit to Kiltartan Cross and stay Till certain second thoughts have come Upon the cause you served, that we Imagined such a ne a air: Half-drunk or whole-mad soldiery Are murdering your tenants there. Men that revere your father yet Are shot at on the open plain. Where may new-married women sit And suckle children now? Armed men May murder them in passing by Nor law nor parliament take heed. "en close your ears with dust and lie Among the other cheated dead.

Reprisals by W. B. Yeats

Published in Icarus in 1956

from e Drawer

by Eavan Boland

Published in Icarus in 1964

(To Michael Longley)

From August they embark on every wind Managing with grace "is new necessity, widely determined On a landing place. Daredevil swallows, coloured swifts go forth Like some great festival removing South.

Cuckoo and operatic nightingale Meeting like trains of thought Concluding summer, in complete agreement, le Towards the sea at night, And nd at last their bright geometry, (Triumphant overland) is not seaworthy.

Sandpiper, nch and wren and golden-crest, Whose ba&ed Movements start or nish summer, now at last Return, single and ru&ed, And lift up their voices in a world of light, And choose their loves as though determined to forget,

As though upon their travels as each bird Fell down to die, the sea Had opened, showing those above, a graveyard With sanctity — Birds and their masters, many beautiful, Tumbled together without name or burial.

Derek Mahon

Published in Icarus in 1964

(on his comeback)

Better to scrabble in the dust For radium lings than trust "at little man down Starlight Street Leaning against his hardboard lamp-post, Uttering innocent fantasy In a voice ‘full of money.’

He will still be there, no doubt, When we are all dead, Singing ‘ "e Same Old Dream’ to the shocked daylight With his hat on the back of his head And his shirt open — Immortality, they call it.

from e Drawer

W. H. Auden

Published in Icarus in 1966

About su ering they were never wrong, "e Old Masters: how well they understood Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting For the miraculous birth, there always must be Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating On a pond at the edge of the wood: "ey never forgot "at even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course; Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry, But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky, Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

Published in Icarus in 1969

My onions have all sprouted, "eir sti skins loosening; the smell Soaks up into the linen press.

"ings do grow, if not stopped in time.

"e day after the fair You said “Twenty years ago Just you were having your happy childhood I sat beside the one-bar re Guessing the wind’s angle, hoping "e same rain swept through the valley Church and school where I grew As pleased as it with my own choice Till I was ten years old.”

Although I know that from 1971 No more mistakes will be made in the rearing of children I failed to reply, realising At that stage no recipe Warmth or ice could make you sound.

by Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

Published in Icarus in 1975

Scanning the close grains of the hillside

"at rises above seapinks and a dark cli

For foothold, I nd the long green leaves of sorrel Crouched at my heel where I ascend In a stirrup of rock, reaching at stems of weeds, Bite the bitter leaf.

A sidling sheep’s track and into stony ground:

Heads of new fern less than knee high

Tight coiled like snails: to reach deep grass

At the eld’s edge: trefoil and daisy.

Fresh wheat combs the slope, it rises until Now I can see the shifting !oor "e Atlantic on both sides of the Head. "e wind shakes the crop

Blows through the coastguard station blackened by !ames.

Troops of grey birds in a ploughed eld

All face out to sea, and beyond them

Notched with storms, the breeches buoy.

Views by John Montague

Published in Icarus in 1975

Oh, the wet melancholy of morning elds! We wake to a silence more heavy than twilight where an old car nds its last life as a henhouse then falls apart slowly before our eyes, dwindling to a rust-gnawed fender where a moulting hen sits, one eye unlidding; a mystic of vacancy.

Shapes of pine and cypress shade the hollow where on thundery nights facing uphill, the cattle sleep. Blossoms of fuchsia and yellow whin drift slowly down upon their fragrant, cumbersome backs. Saga queens, they sigh, knees hidden in a carpet of gold, !ecked with blue and scarlet.

e Drawer

Lines Written ree Miles From Watershed Island by

Paul Durcan

Published in Icarus in 1975

Sand martins helicoptering into the upper air

Are like the Nerves of Lovers

Hovering over them as Advertisements of Awkwardness; O writer, do not turn them into god and goddess; Humanity is bottomless if the truth be loved.

She is unity of being — "e re in her his new hands now may kindle And she builds her limbs around him, making a sea-grove Inside of which he kneels a grown boy out-grown by a mountain tree And upon her roots he pours all the water.

"e tree sinks down into the climbing earth; Now he may lay his head upon the roots he died for. She moves her branches, secreting shadows that in long lengths fall through his head; Her face is her soul — Inside the outside like a tree.

Sand martins drop down through the lower air

As over sand hills through dusk under starlight A young pair tramp homeward to parent and child.

Sebastian Barry

Published in Icarus in 1976

Walk trembling roads, your eye’s dry song; sing crows for drabness, gulls' talk godless, sti -winged herons troubled by your stare; drink in their streams near rough-barked trees; in lanes cobbled with warm beach-stone eat on thin chairs for !uted bone; with full-mooned elds or some town’s dawn a stumbling forest or a hill of twigs make dulled words as elegant again; settle the riddle of fat high swans that marked a sky of weakened red as dark you turned to Greece; then fresh-tongued in terraced island towns sing for the women you think beautiful.

Published in Icarus in 1988

Note: On Tuesday the 18th of November, Seamus Heaney delivered a T. S. Eliot centenary lecture to the Philosophical Society, in which he discussed his long apprenticeship as a reader of Eliot’s poetry and his continuing response to it more than thirty years after sending away to Derry for ‘the rst and probably the only copy’ of his collected poems to appear in his native village of Mossbawn. Icarus was lucky enough to be able to share some of his insights since then in a conversation we partly reproduce here.

Icarus: You spoke of awe as a childhood reaction to Eliot. I was wondering whether this is almost a wilful response — taking the poems as music and postponing the meaning until a later reading?

Seamus Heaney: Well, I wished I had known at the time not to be anxious about the meaning. In fact Eliot himself gives that advice somewhere: to read a thing rst for the general impression. What my resentment would be is that we were forcemarched towards meaning immediately, before having the time to laze around in front of the poem. A. N. Whitehead says there is a rhythm of learning and he describes the three main stages as romance, precision, generalisation. What happened with me and, I think, my generation of undergraduates was that face-to-face with poetry, we were forced into precision without having the romance. I suppose I’m getting round to romancing about it now.

Icarus: It would be important to let it germinate before you begin to analyse it analytically then.

Seamus Heaney: I think that is so with Eliot. With other poets who don't present the same resistance of surface — I mentioned "omas Hardy for being lucid and clear — the meaning need not be a problem. Eliot, I suppose, gestates, or infuses his meaning into you; you can take him like a tealeaf.

Icarus: "is is where the ‘auditory imagination’ you emphasised comes into

play. But one of the quotes you gave from Four Quartets mentioned ‘the deception of the thrush’. What could this be if it isn’t a sort of hostility to poetry as a spoken medium? Is Eliot’s song a purely intellectual one?

Seamus Heaney: Yes. "e self-denial, which is a part of his whole mental habit underneath an essay like Tradition and the Individual Talent, applies most rigorously in the realm of composition. He was one of the most sparing of writers unless there was something driving him to write, unless there was enormous pressure of a lyrical and religious nature. "ose Choruses from the Rock are an attempt to unify the disciplines of lyric and religion — it doesn’t work, so he stops it, but there is a purity of motive behind them.

Icarus: A conscious attitude before the poetry begins, which permits the reader to use the ‘auditory imagination’ because it has already so carefully prepared the impression it hopes to create?

Seamus Heaney: Exactly.

Icarus: Seamus Heaney, thank you very much.

from e Drawer

Herself and Himself by Brendan Kennelly

Published in Icarus in 1994

"ey’re driving in From the cricketing elds of Dublin past the Five Lamps, Empress Lane And the Corner of the Talkers where you’ll still get wind of the bombing of the North Strand in a war we were no part of or so we thought. It isn’t always we know what wars we’re in.

"ere’s shopping to be done young males waiting for baker’s bread. She knows the shops, the men and women behind the counters. She knows himself too. On a tough journey, a few words will do to ensure the futures will be fed. She does the shops, gets what she wants, they have two creamy pints together then hit for home between the worked elds and the sea, herself and himself words and silence peace and war you and me.

Blue Table by Éilís Ní Dhuibhne

Published in Icarus in 2005

Before I got the phone call

I planned to paint the garden table blue.

I dragged it out from behind the shed today

Because the sun was shining for the rst time

Since Christmas and the air was warm as summer.

"e parliament of birds debated all the morning

In voices low and high.

"e da odils were at their best

"e sea was milky.

I watched a diver plunge for sh ten times

In half an hour, marvelling at the way

It disappeared beneath the wave

For minutes at a time

Came up and dived again.

"en I remembered the table.

I dragged it down the garden to the place

Where you can eat your lunch.

Its wood was worn, its boards warped, Its surface dull and shabby.

I saw it blue, the lovely blue of Sweden, With a snowy linen runner on it

Us sitting there, eating a simple meal

All smiling, I saw us there

All smiling

Around the deep blue table

In the garden.

"en the call came.

I have !own the Atlantic

To reach you in your chair. Cuddling up, we talk about Flowers, important things, And hold hands to celebrate Spring gentian’s heavenly (Strictly speaking) blue. You grow anemones, You say, wind’s daughters. I say the world should name A !ower after you, Stanley. We read each other poems. You who’ll be a hundred soon Take forever to sign My copy of Passing "rough. What !ower can I o er you From Ireland? Bog asphodel Is the colour of your shirt. Grass of Parnassus? Mountain Everlasting in New York? Your zimmer-gavotte suggests Madder with its goose-grassy Tenacity, your age spots Winter-!owering mudwort. But no, no. Let it be Spring gentian, summer sky At sunset, Athene’s eyes, Five petals, earthbound star.

Visiting Stanley Kunitz by Michael Longley

Published in Icarus in 2006

Roma Kid by Kevin Barry

Published in Icarus in 2014

She watched her brothers sleeping but not for long and left them in the grey dimness of a February morning that was not yet half to life. She did not speak the language but understood plainly the knotted gestures and the dull faces of the people that worked here. Her mother had told her nothing but the girl knew that soon the family would be sent home again and she would not go back there. She was nine years old and chose for her leaving the red pattern dress and zipped her anorak over it.

She went quietly among the chalets of the asylum park. She held the zipper of the anorak between her lips and its cold metal stuck fast to her lips. It was a ritual of safe passage to hold it there until she was clear of the park. She did not look back at all and no voices rose to call her back. She walked out to the foreignness of the morning. She climbed the embankment. She had none of the words that appeared on the advertising boards by the motorway as she walked in her squeaking trainers along its verges. She did not have the words on the side of the bus that passed by lit against the morning and she had none of the pitying words that formed on the mouths of the passengers who stared out at the thin child in a dress of red paisley, an anorak —

Poor knacker child.

Poor pavee kid.

Poor latchiko.

She walked for an hour or more. She was hungry. She knew where to cross for the station by the image of a train on the road sign and by the arrow’s direction. "ere were people at the station waiting in a yellow heated room. She did not ask them for money because if she did not speak there was a good chance she would not be spoken to. Her stomach hissed and the morning sent up its rst cuts of lonesomeness and fear. She would not see her brothers again.

Slight as a ghost she went about the station as its haunting. She knew by the one journey the family had taken that the trains aiming left must be headed back to the city of Dublin again, and to its trouble, and those that aimed contrary must go to the countryside beyond. "ere was no ticket checker at the station — it was a man on the train that checked the

tickets and on the outward journey he had been a kind man and on the fact of this kindness she had built her plan and laid her fate.

She crossed the rails by the metal bridge. A light rain began to fall and it spoke more than anything else of the place through which she moved. "ere were just a couple of passengers waiting on the far platform. Her trust also was that the countryside would be kinder.

She sat on a bench and again she felt for the zipper of her anorak and got it between her teeth and bit down hard on it. When she had played with her brothers the evening before, it was for the last time, and they had fallen one by one to sleep then, and she counted o in her mind once again, and as she would for many years, the four black buttons of their tiny bopping heads: Andrzej, Luca, Tobar, Bo, the way there was a tune to it almost.

"e minutes passed and the platform became busier. Tired-looking men and women took their morning places on the platform and let down their slow ropes of words. She listened intently for the tone that might signal danger but the people were too tired to notice her, or at least they did not notice her for long: she was among them but as an image, as a type, and she registered for half a second’s pity or distrust — poor Roma kid — and was erased again.

"e train’s noise came up as a rumble of promise. "e word on the bulb of the train’s nose was ‘Sligo’. "e morning came alive around her as the train pulled in and she watched herself as though from above as she climbed on board. She stayed in the space between two carriages. "e train took o again and she rocked on her heels as she crouched there. "ere were many empty seats but she did not enter a carraige to take one. As she crouched and rocked on her heels she began to sound a low groaning beneath her breath, and she let it sustain, and it slowed the beating of her heart, and it made her feel stronger. She blinked her eyes also, rapidly, and in a rhythm counter to the low, held groaning — she made in this way a shield of hummed noise and !ickered movement against the world and its grey morning.

"e train pulled back the morning and the countryside and she was alert to the grey elds passing, to the sheds and outbuildings, the sidings and high, the distant towns, and as she went by she checked for possible hiding places and lairs. She was reassured. She was very hungry.

Drawn by her hunger a cart came trundling along the passage laden with sandwiches and cakes and crisps and cans of soft drinks. "e cart was pushed by a young woman and the girl knew at a glance she was not from this country either. "e woman searched her out quickly with a look, and said —

Okay?

"e girl was frightened at the day’s rst contact but smiled and something in the smile was read by the woman.

Are you alone? she said. You speak English?

She knew the word ‘English’ and shook her head against it.

"e woman spoke in another language then and it was closer but not known and again the girl shook her head and with her large eyes she pleaded.

Don’t be frightened, the woman said.

She passed the girl a mu n and moved on again and as the girl held in her hand the mu n she held her breath also.

She waited, and then she took o the plastic wrapper, and the doughy smell came up like heat and there was the smeared blue of the berries, and she broke o precisely a quarter piece, and wrapped the rest again carefully, and placed it in the pocket of her anorak. Even as she savoured the rst bite she was already patting her pocket to be sure the rest of the mu n was in place. "e creatures in her stomach were soothed and they quietened as she chewed.

She kept watch along the carriages for the ticket collector. After a couple of stops the train was almost empty. "e wind moved in slow waves across the winter greys of the elds; there was the iron beat of movement along the line. She was lulled, and she closed her eyes for a half minute, and then more — she tried not to go deep — but she drifted, and almost dreaming she felt the soft pads of ngertips on the back of her hand. She opened her eyes to the ticket collector —

Now, he said.

By the word she could not yet tell if he was kind or not. She shook her head, and pleaded.

Uh-oh, he said.

She knew what that meant.

Are you not with somebody? he said.

No mother? he said. No father?

She bit down hard on her bottom lip.

Okay, he said.

"e nine years of her life was written on the bres of her skin and she could be plainly read, all the alleys and doorways and pleading years could be read, and the longing for the four tiny brothers who had been her comfort and, guiltily, her burden — their black buttons of heads, bopping — and the cold tile !oors of railway stations, the detention chalets, the home place that would not be seen again, the cherry brandy on her grandmother’s sour breath, the softness of her father’s touch.

Do you know where you are even?

Silently, she pleaded.

We’re past Longford now, he said. Have you people waiting on you? I’m not even going to ask about a ticket.

He made the gesture of scratching his head and she smiled as he played at being puzzled.

What’ll we do with you at all? Hah?

"e food cart at that moment came by again. She was the subject now of a consultation. "e ticket man conferred with the woman who pushed the cart. After a moment, both of their heads moved sadly from side to side. A phone call was made.

"e train pulled into a country station. "e doors opened, gasping, and the treetops outside were eerie with the voices of birds. She hummed a low groaning and !icked rapidly her eyelids.

Ah go handy now, the ticket man said.

She was made to leave the train. She was placed in the station master’s care. He brought her to a room of the station house that was made up as a home.

What in Jesus’ name are we going to do with you? he said, as the colour rose and then faded in his face again.

He gave her a banana and some biscuits. He went to the o ce adjoining his home room to make a phone call — she knew it would be the police next. She heard him speak and understood the note of his anxiety and confusion. She pocketed the banana and the biscuits and opened the station house window and climbed outside and landed in a !ower pot. She put her feet to the ground and quickly she was across the car park and over

a fence and into the sidings and into the elds.

February.

"e elds were cold and grey and wet as she crossed them and open to the skies and the wetness came through her trainers and a sharp wind cut across the elds and through the fabric of the anorak and of the dress to her bones. She kept to the edges of the elds and moved in quick darts. She kept down when cars went past. She beat away the briars of the ditches that swayed with the wind and the branches were bare but with swollen buds that told soon a cold spring would come. "e birds were everywhere garrulous. She was at home again in the country — the rough lanes were home, and the ditches were home, and now she could walk for miles and her heart lightened. After a time the country rose de nitely into hills. She knew that she was strong. She went for another hour, and then longer, and ate the banana — she ate it under a tree of early blossom by a rough stone wall and as she sat there motionless in the wind but for her chewing a sweet black mouse crawled from beneath a crack in the rocks of the wall and lowered itself to the ground on a strand of yellowed grass that leaned and bent with its weight and always in the future she would think of this place as the place of the mouse blossom tree. She moved on again. After a while she saw a small town rise to the north and knew to keep clear of it. She walked along a country lane by its old stone walls. She saw nobody. Sometimes a dog’s bark came from far o — hoarsely, plaintive — and it was always the same dog. Another town stood up to announce itself coldly, and she kept clear of it, and there was a great swathe of woodland ahead, rising, and she knew at once that she would climb to this wood — she was drawn to it strongly. She climbed a lane made dark by trembling hedges on either side and the chill in this laneway was intense and made of more than the air — it was malevolent, a badness — and it hurried her step, and soon she was in the late-winter of the woods, at the quick fade of the February day, and it was strange but familiar, the path that led through and became rougher, and there was the scent of the needles of the pines that she trampled and the wind was distant as she became lost in the woods, it was such as the wind at the edges of a dream, and now she knew that there was a presence among the trees.

She hurried to get through the woods but it was everywhere around her, as gripping as a cold sea, and a terror built and would not relent — she

knew that she was being watched. She hummed against the fear and !icked her eyelids rapidly but she was in disarray now as she felt the watchful presence and she began to run and the root of a tree took her ankle — she went down. She reeled inside and vaulted on a high white screech of pain — she was wretchedly in pain. She lay there crying and in great pain as his shadow moved across her. "e broken hatched light of the woods was impoverished as the day ended and his face was made of haze and shadow.

Hush, he said.

He leaned down close to her and her heart popped clear of its box and clear of the trees and she clenched her teeth and prayed hard that she might wake from the bad dream — she did not wake.

Ah look it, he said. No-one’s dead.

He placed lightly a hand on the broken ankle and she lurched again in pain.

No-one’s dead, he said. As we always say at times of abject fucken disaster.

He was old and had the look of the woods — he was a ferny, mossy, twisted old thing, and all of his roots and bres spoke of years long and deep in the shadows and out of the light. He was a small bony creature but limbre, and he lifted her from the ground, and she felt his odd energies and strength, and now she was not afraid at all.

Best thing to do with pain, he said, is ignore the ignorant fucker.

As he carried her through the woods the e ort of the carrying caused his breath to labour but only slightly even though she was almost as big as he was. "ey came to a sudden clearing in the woods — a trailer was kept neatly there on blocks.

Do you have the English? he said.

No, she said.

No is a good start, he said.

He set her down on the plastic crate that worked as a step to the trailer. He pointed at her ankle. "e tops of the trees were wind-swayed, and sang.

Is the pain bad, missy?

He winced to explain the pain he meant. Yes, she said.

We are making progress, he said, in leaps and bounds.

She smiled to show the perfect white of her teeth. He laughed at the smile. He considered her. He displayed with a sweep of the hand and a formal bow the bleakness of the woods surrounding.

Fine spot you picked, he said. "ere being no place known to man nor beast of grimmer fucken aspect.

He opened the trailer door with a poke of the foot and reached for her and carried her inside.

"e Ox mountains you decided to land in? he said. Christ on a bike. "e pain came again in a nauseous swooping and he saw it in her and spoke quietly against it and it fell away. About her was a solitary man’s cabin. It had a great neatness. "ere were stacks upon stacks of old books. "ere must have been thousands of them that lined the walls and made of the trailer a cave of books.

Did you come through the town? he said.

He set her down on a low armchair and stoked a re of sticks in a pot belly stove.

Town? he said, and he made steeples of his knuckles for rooftops.

"e re took again and its glow lled the small trailer’s room.

No, she said.

As well not to have, he said. "at place is gone maniacal.

He fetched some bandaging from a high shelf and wrapped tightly her ankle.

"e vulgarity of people, he said.

He placed a pot of water to boil on the hot plate of the stove.