10 minute read

Tales of Survival

IC Always Moves On: Tales of Survival*

Tale #1: World War I, 1914-1918

As WWI raged on, Rev. Alexander MacLachlan realized that he couldn’t possibly keep his staff and boarding students fed. Foreseeing an inevitable famine, he ordered a large supply of greatly overpriced food staples – creating a huge deficit in the school’s meager budget, so much so that IC was on the brink of shutting down.

Then a miracle. A telegram came from long-time donor, Emma Kennedy, and a wealthy Protestant philanthropist Cleveland Dodge, announcing a gift of $13,000 for the current expenses of the College. It was enough to keep the school going for another year.

But then came another blow: Turkish authorities forbade all staff who were citizens of countries at war with Turkey to teach and called on all Turkish male citizens of the Ottoman Empire – regardless of age – to arms. Only three faculty members now remained. If IC were to shut down, the Turkish authorities would immediately requisition the campus. And so despite epidemics of typhus and Asiatic cholera (IC’s own physician died of typhus) and an unrelenting threat of famine, MacLachlan continued conducting the semblance of a school to the accompaniment of artillery and hum of aircraft overhead.

In November 1918, WWI ended. Foreign faculty began returning, and MacLachlan welcomed back the rest of the student body.

Tale #2 SepTember 1922

With the Turkish army now 25 miles east of Smyrna and getting ready to fight the Greek troops that had occupied

the city, Rev. Alexander MacLachlan was informed that a special train would evacuate foreign nationals working at IC. When the train arrived, all but MacLachlan and his son-in-law, Cass Arthur Reed (IC’s vice president), boarded the train. They refused to leave IC.

As the train was about to leave, several people stepped off.

If you stay, we stay, they said. They, too, will not leave IC. Shortly after, MacLachlan was severely attacked by a group of Turkish Chettes. As he lay convalescing on his bed, he saw spiraling smoke from the city. Smyrna was on fire!

Again, foreigners were given orders to evacuate. Finally, after much cajoling, the bed-bound Maclachlan agreed to leave the campus but on the condition that American guards remain behind at IC.

When he finally returned to IC at the start of what should have been a school year, MacLachlan found IC’s beautiful campus completely overrun with cats and dogs and plagued with flies. Not only had the school lost the entire Greek and Armenian student body, but IC had lost its curriculum. A new Turkish curriculum was in place. It would have been easier just to shut down the school. But that was out of the question. Instead, IC faculty and staff set to work rewriting the curriculum, and a few months later, IC reopened its doors to the now mostly Turkish students.

But the school practically had no money. And so Maclachlan set off on a fundraising drive to the US. By the end of the year, and except for a $5,000 gift via the American Board, practically all donations were ones solicited by MacLachlan himself. It was just enough to keep the school ticking along.

Tale #3 Smyrna, 1929

In 1929, the US stock market crashed, and the Great Depression spread across the nations. Millions of people lost their jobs. Enrollment at IC dropped drastically as many parents could no longer pay the tuition. Foreign teachers left the College. By all accounts, IC should have shut its doors. But against all odds, it remained open. Its saving grace was a $1 million endowment fund – established a few years back when IC joined the Near East College Association. Little did it know

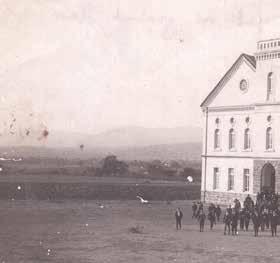

The Meshref campus

back then the role that the Fund would play in the coming few years.

Tale #4 Smyrna – beIruT, 1936

The board had decided to close down the College in the face of Turkish nationalism that gripped the new nation. IC needed a new home. AUB President, Bayard Dodge, invited IC to merge with AUB’s faltering preparatory school. The merge would benefit both. Not only would IC bring its rather large library book collection, but most importantly, it would bring its $1m Endowment Fund. While AUB had its own Endowment Fund, its prep school had none. If the university were to shut down the Prep, AUB would lose its main feeder. If the Prep keeps going, AUB’s funds would be severely affected. When Dodge heard about IC’s problems in Smyrna, he quickly invited the school to merge with the university. IC’s $1m endowment fund was more than enough to save the Prep School. And there was a bonus: IC’s good reputation would greatly expedite AUB’s reaccreditation by the New York State – a necessary step in keeping it alive. The school could even keep the name “IC” for sentimental reasons.

And so in 1936, IC moved to Beirut, bringing with it the very much prized and needed $1m endowment fund.

IC not only survived but had found a permanent home.

Tale #5 meShref, 1976

IC president, Thomas Schuller, knew he had found the perfect location for IC’s new campus in the picturesque hills of Meshref, in the Chouf district about 25 kilometers to the south of Beirut, overlooking the sparkling Mediterranean Sea. A famous American architect, Edward Durell Stone, was hired. Stone was making waves in the architectural world using the “International Style” in his designs. In 1971, IC Meshref was ready to open its doors. The campus was breathtaking: a $6 million complex of arched and arcaded buildings covering an area of almost 700,000 square meters, hailed as the largest and most modern high school in the region. The new campus boasted six classroom buildings, a student center building and one dormitory building for both boys and girls. In addition, there were three green football fields, three asphalted volleyball courts, three basketball courts, and three tennis courts. And this was only phase I of the construction plan. By 1980, the campus would be ready to welcome IC’s entire student body, and the Ras Beirut campus would be returned to AUB as the university requested. The eruption of the civil war in 1975 still had not deterred IC from its plans to move to Meshref.

But in 1976 and with a heavy heart, IC administration shut down the Meshref campus and brought the students back to Ras Beirut and rented a few classrooms from ACS. Moreover, there was a sudden drop in student enrollment as many families fled the country, putting the school under immense financial strain.

The loss of the Meshref campus and the extra expense of renting facilities in ACS drove IC to the brink of financial disaster. While not yet in the red, it was teetering on edge. To survive the year and indeed the next few years, IC needed the tuition fees of at least 1,600 students – it had nowhere near that number at present.

Amid this grim situation, a small miracle occurred. Sultan Qaboos of Oman contacted IC. The Sultan would like to establish a coeducational boarding school of the highest quality in Oman. One very similar to IC. Was IC willing to help? The Sultan was willing to pay dearly for this service.

It was an answer to a prayer. It so happened that IC President Tom Schuller earlier had the brainwave to establish a department at the school to teach the latest methodologies to teachers inside and outside IC – to generate extra income for IC. And thus was born the Educational Resources Center or ERC. The department personnel were already trained and rearing to go and, in fact, had had their first experience in opening a school in Nigeria in the 60s. ERC was quick to send off a team. The Sultan sent in the payment. IC continued.

Tale #6 bShamoun, 1982

The golden dome covering IC’s pool in the hills of Bshamoun was one of Israel’s first targets. It was supposed to be inaugurated that very day. Many families had returned to the country, thinking the war over, and enrollment at IC increased once again. But enrollment at ACS had equally increased, and the American school would naturally like its classrooms back.

And so IC president Alton Reynolds set his eyes on another campus: the British Community School in the hills of Bshamoun between 400 and 580 meters above sea level and only eight kilometers from the city center.

The campus was duly purchased, and elementary school students were bussed to Bshamoun. If all goes as planned, the Ras Beirut campus will be vacated, and as requested, returned to AUB.

But Bshamoun received a direct hit during the Israeli invasion, and once again, students were brought back to the Ras Beirut campus. Somehow, the campus, which usually takes 1,200 students, had to accommodate 2,600 students – requiring still more rental space from ACS.

It wasn’t ideal, and they were undoubtedly cramped, but IC kept going.

Tale #7 beIruT, 1986 -1988

Once again, IC found itself in trouble. This time, it didn’t have the ERC to turn to. Ever since the ERC stepped in with the Oman project in 1975 and provided IC with a considerable income, the Center had been working on similar projects all over the Arab world and even beyond.

But by January 1986, the projects had dwindled significantly. Many ERC consultants, desperate to flee the war, had resigned from IC and taken on new posts in affiliated schools. Moreover, economic recessions hitting Gulf countries had ended any new projects. The ERC was increasingly turning its attention to local projects that, while worthwhile, were not lucrative.

It was a big blow to the school’s finances. Again, there was a continuous exodus of families from west Beirut. The loss of tuition was seriously jeopardizing the school’s future. Also, the sudden collapse of the Lebanese pound – a 480 percent drop – was catastrophic for all. Tuition fees had effectively become unaffordable for many parents. Another downfall for the school was its inability to find qualified teachers. A brain drain and decreasing salaries – thanks to the continued depreciation of the Lebanese pound – had practically emptied the market of qualified teachers. In addition, AUB was not graduating teachers, and, of course, it was impossible to bring in foreign hires.

It was then that IC president, Alton Reynolds, came out with an idea: What if the west Beirut campus doesn’t survive? Should IC not have an alternative campus – on the east side? The board approved, and after an exhaustive search, the perfect spot was found in the picturesque hills of Ain Aar. Construction began, and in 1988, IC Ain Aar welcomed its first students.

Tale #8 1988, neW york

Once again, IC was on the brink of financial disaster. Inflation and dwindling student enrolment had put an enormous strain on the school. “We will launch a fundraising campaign,” announced Chairman of the Board, Bill Turner, at a New York board meeting. “We are going to raise almost $6 million.”

Three million dollars would replenish the IC Endowment Fund, and $2.6 million would be used to execute various projects identified by the administration as essential for the improvement of both the Beirut and Ain Aar campuses.

The Trustees stared at him. The war is ongoing. Bullets and shells were flying all over the city. People were being kidnapped. Who will give us money at a time like this?

Nevertheless, said Turner decisively, the board is launching a fundraising campaign.

True to his word, Turner and the Board raised over $6m and replenished the endowment funds.

IC stayed open.

MORALE: IC ALWAYS moves on.

* Tales adapted from I am IC: A School’s Journey from Symrna to Beirut by Reem Haddad

The Bshamoun campus