11 minute read

Nouhad Dammous

Zeina Dammous Nahas, Joumana Dammous Salamé, Nouhad Dammous, Randa Dammous Pharaon

The Guru of Hospitality: Nouhad Dammous

If his father had his way, Nouhad Dammous ‘51 would be a physician right now. But fortunately, Providence interfered, and Dammous’s name became synonymous with hospitality. He is no other than the country’s first hotel school founder – a pioneer in the Arab region. Today, at 87, his ideas continue to flow enthusiastically, perhaps in a slightly different direction, but still in the realm of the hospitality world he had created in his youth.

It was his eldest daughter, Joumana, who had opened the door to the exciting domain of event management. The father-daughter duo made waves when they launched HORECA in 1993. It became the largest annual meeting place for the hospitality and food services industries – heralding in an era of highly successful events, including the Garden Show, Beirut Cooking Festival, Wine Lab, Hospitality Salon Culinaire, and Salon Du Chocolat. Over 18,000 trade visitors attended every year. So successful was HORECA that the brand name was franchised-out to KSA, Kuwait, and Jordan and more in the pipeline and three online - magazine platforms serving the industry: Hospitality News ME, Taste & Flavors, and Lebanon Traveler

His wife, Claude (who passed away three years ago), and two other daughters joined in. And so it was that the Dammous clan continued to preside over the kingdom of hospitality – slowly building up a highly competent team who would serve them for the next 20 years (and ongoing).

As he sat in his Dekwane office, once a humble paternal home quickly expanded into three floors back in the 1990s, Dammous proudly gestured towards his daughter.

Ironically, it was she who hounded him into allowing her to enter the hospitality sector.

“It’s not for you,” replied her father. “It’s a day and night job.” But she was relentless. Finally, the LAU business graduate was sent off to the US to train in management in the Hyatt Regency hotel. She returned with enthusiastic ideas on event management. And not on a small scale either.

She had long put together two plus two: a guru of hospitality with a wide range of contacts and a young graduate with novel ideas can only lead to triumph. She was right.

“Hospitality always gets back up on its feet,” said Joumana. “The best way was to have a series of conferences. Let’s get the heads of institutions together, network, and discuss their products.” Dammous looked warmly at his

daughter.

Perhaps Dammous had recognized his own zeal for the hospitality world in her. For didn’t he, too, at a young age, get captivated with a world that he would eventually revolutionize?

He can still vividly remember his first employer telling him to “think of a job in which you will invest 18 hours a day but which will make you happy.” He was then in Saudi Arabia working for the Trans Arabian Pipeline Company and thinking of continuing his studies in finance. “Are you happy working in the business world then?” had asked his boss.

The young Dammous was quick to shrug his shoulders. “No,” he replied. He reflected. His current job at the company was to organize housing and meals for hundreds of Tapline employees. No, it wasn’t the finance world that he liked. He suddenly knew what he wanted.

His boss’s advice would be a turning point in his life. He wanted to become a hotelier.

He searched for a top hotel school and found one in the US. The Lewis Hotel Training School in Washington, DC. It was a prestigious, highly popular school, the only one of its kind boasting a Hotel Training Course, a Hotel Accountancy course, and a Cookery course. Most important, it offered a correspondence program. For the next three years, he studied by correspondence. Today, the Lewis training books (considered historically rare) are proudly displayed in his office. To improve his English skills, he also took English lessons by correspondence with a school in London. When Saudi officials got wind of it, they immediately recruited him to teach the Company’s Saudi employees English. It was then that Dammous discovered his second passion: teaching.

After graduating from the Lewis Hotel Training School in 1954, Dammous was offered a scholarship to study hospitality in Germany. It was the chance he had been waiting for. Bidding his Saudi friends goodbye, he settled in Heidelberg.

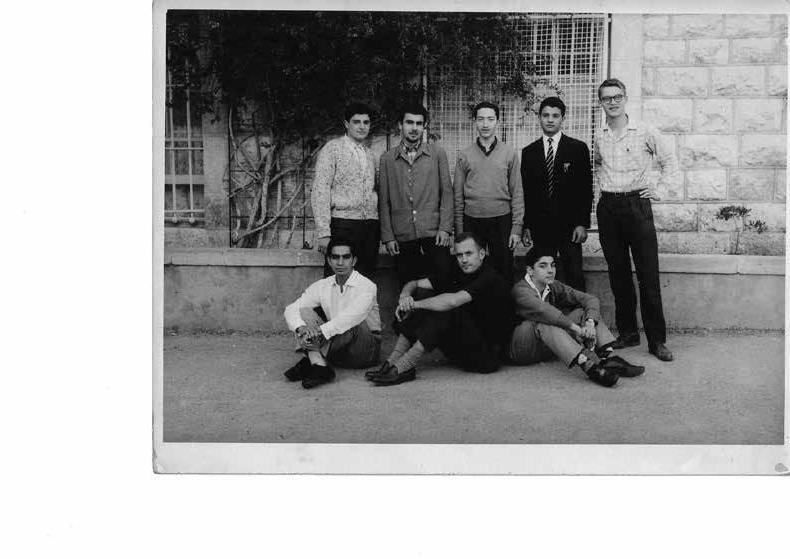

But in 1955, the most devastating news reached him: his beloved father suddenly died from a stroke. Dammous rushed back to Beirut. At the age of 22, he was now responsible for his mother and sister. He ached for his father, terribly. Did he do wrong by not following his father’s heed and studying medicine? But a medical degree would have taken years to complete, and Dammous had not the patience. He wanted to earn a living as soon as possible and help his father with their living expenses. A lawyer at the Lebanese Customs, his father was barely making ends meet – especially after he insisted that his only son study at IC. At the memory of his alma mater, Dammous smiled fondly. “Ah, IC,” he recalled. “The best days of my life. I would catch the tramway every day from Ashrafieh to the Bourj (Martyr’s Square). Then catch another tramway to the school. IC gave me my character.”

But now, what was he to do? His father’s voice resonated in his head. “Succeed, everything you do, do it with success. Never accept anything less.”

Determined to continue what he started, Dammous spent the next two years interning at various top hotels in Switzerland, France, and Istanbul. He simultaneously completed his Diploma in Hospitality Management from Heilderberg – effectively making him the first Lebanese to graduate from an international hotel management institute. His thoughts, however, remained in Lebanon so much so that one sunny day while in Switzerland, he and a fellow Lebanese friend went around sticking small stickers on unsuspecting parked cars stating “Lebanon: Land of Sunshine and Beauty.”

In 1957, he returned to Lebanon, where upon arrival, the Ministry of National Education contacted him. It seems the Swiss national who ran the governmentowned hotel school – established only a

few years earlier in 1951 - had left. Would Dammous take over as director?

Excited, the 24-year old Dammous rushed to inform his grandfather of the offer. “That’s it?” said his grandfather angrily. “This is what you want to become? A ‘ashi’ (cook)?”

But Dammous saw a great future ahead and accepted the ministry’s offer. On the first day of work, he quickly grasped the less-than-desirable situation: 40 students and almost all had chosen to study the hotel business simply because it offered room and board. That’s it. No passion. There were no programs either. The building itself was square and austere. Still, Dammous was raptured. With a magnanimous vision that only the very young can muster, he set to work. First on his list was a new building. And so he marched into the government’s Construction Department and stood squarely in front of its manager, Mohamad Raad. “What is this hospitality school that you want me to run?” he said. “It is merely a room, a kitchen, and not more. It doesn’t have any of the requirements needed for students even to gain the very basic knowledge of the industry.” Raad must have been impressed with this outspoken young man, for he promptly sent him to inspect a building site in Dekwaneh. “The government is erecting a building there,” he said. “Go see if it is suitable for a hotel school.” Dammous immediately went over and saw the beginnings of a square unimaginative cement building. He promptly returned to Raad.

“This will not do,” he said. “What we need is a building purposely built as a hotel, with various departments with classes to learn the theory and labs to apply them.”

Raad sent after the well-known architect Assem Salam. “This is Mr. Dammous,” said Raad. “Kindly work with him to change the blueprint of the building. It is now to be a hotel school.”

A year later, the École Hôtelière in Dekwaneh was completed – except for electricity and water networks. Those came six months later – after the students moved to their new school. Many of those first students Dammous had recruited personally as he went from school to school in various villages meeting students. Still, the campus looked barren to Dammous. And then it came to him: what he loved most about arriving at IC during his boyhood was the greenery that welcomed him to the campus. The next day, Dammous showed up with dozens of tree shoots and planted them together with students and faculty.

Meanwhile, Dammous had immersed himself into creating a new curriculum - widely based on his education and experiences abroad. Foremost on his list was the establishment of a student-run restaurant. His idea was straightforward and, in those days, considered Avantguard: allowing students to apply their newly acquired theories on real customers.

He went on to establish the Lebanese Brevet Hotelier, Lebanese Baccalaureate Hotelier, Technician Superior Hotelier, and the Hotel training modules. The Ministry of Education frowned. “You want to give ‘ashes’ (cooks) baccalaureate degrees?”

He explained in vain that the business of hospitality was not about ‘ashes.’ The ministry finally acquiesced.

The École Hôtelière made waves in the Arab world. It was the first school of its kind. Hospitality managers worldwide arrived to convene and exchange ideas in the school’s huge conference room. The school’s students served all. In a few short years, 800 students – all handpicked by Dammous – entered the school’s doors.

The hotel and restaurant’s reputation was so successful that the Ministry of Tourism asked him to organize, furnish and manage the resthouses of Saida, Tyre, Jeita with the students and prepare the opening of the resthouse of Tripoli and Arida.

At the request of the Ministry of Education, he also assisted in opening hotel schools in Jordan, Cyprus, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia

By now, the golden days of Lebanon had begun.

Dubbed as “The Paris of the Middle East,” Beirut became known as a glamourous and cosmopolitan city. The city flourished as an intellectual and financial hub and a favorite tourist destination. Luxury five-star hotels dotted the beaches. A variety of nightclubs and fancy restaurants catered to the wealthy and were often frequented by foreign celebrities. Local cafes became hubs of debates and good-natured arguments. The St. George Hotel opened in 1934, hosted many celebrities, including Brigitte Bardot, Omar Sheriff, Peter O’Toole, Elizabeth Taylor, and Richard Burton. British double agent Kim Philby often drank at its bar. The best international and local stars performed at the Casino du Liban, a short drive up the coast. By the mid-1960s, Beirut had become known as a glamourous playground for the rich and famous. It was the pinnacle of hospitality.

The École Hôtelière could barely keep up with the local demand, and moreover, Arab countries were sending their youngsters to the school. The École even attracted a visit from Cornell University officials, a US institution renowned for its hospitality program.

In 1972, to guarantee the Hotel School’s continued success, Dammous convinced the Minister of Education to grant a scholarship to two graduating students to replace him at his eventual retirement. (The students went off to study at Cornell University and came back to Lebanon, but unfortunately, because of the civil war, they were not hired by the ministry. After a year, they went back to the US and became well known in the hotel industry).

In 1975, the country’s golden years ended abruptly. The École Hôtelière was attacked and raided. Dammous, now married with three daughters, moved to France.

A year later, he returned. His zeal for hospitality in Lebanon rejuvenated. In 1980, he established the Hospitality Institute to consult and assist hotels and restaurants in Lebanon and Arab Countries. In 1982, he was appointed as advisor of the Lebanese Ministry of Tourism. Meanwhile, he continued running a semblance of the École Hôtelière under the dire circumstances and the few salvaged equipment.

At the end of the war, the YMCA donated enough money to rehabilitate the École, and Dammous added a higher degree.

Soon after, however, Dammous retired but continued to climb and indeed reign over the hospitality world, earning him a series of prestigious awards, most notably the National Order of the Cedar and the Doctorat Honoris Cosa.

Until this day, Dammous often thinks back to the words of his first boss. The one who inadvertently started him on this exciting journey. “Think of a job in which you will invest 18 hours a day, but which will make you happy,” he had said.

Yes, thought Dammous smiling. It’s been a great job. And the best part is that the job is ongoing. He believes the future can only get better, despite an economic crisis, a pandemic, and a destructive blast that killed almost 200 and injured thousands.

“Hospitality is everywhere now,” he said. “This difficult period will pass. We have to be patient. There are many good changes ahead.”