Ian Wieczorek - Fragments

One, perhaps the major, function of art is to train the mind in differentiation. The human eye, observes Leonardo da Vinci in his Trattato della Pittura, (da Vinci,1721) can distinguish multiple types and colours of shadow. Visual artists and philosophers have spent centuries successfully distinguishing between multiple levels of obscurity. Analysing complexity in complex and subtle ways is what artists and philosophers do. The reason is not so hard to grasp. A mind that can distinguish between two or twenty-two microtonal changes, in colour as in music, is a mind which is subtle, supple, and less likely to make crass philosophical, or other consequential errors. Kant’s Critique of Judgement famously posits wine-tasting as an example of how taste may be both irreducibly personal, but judgement is objective when based on consensual criteria. (Kant, 2007) A real connoisseur (as a result of training, expertise, memory and experience, but most of all discrimination) is able to distinguish between a particular grape, vintage, year, even hillside, and other real connoisseurs of equal training will be able to agree with him/her. So too, the trained ear can easily distinguish the one note in an orchestra which is a quarter tone, or less, ‘flatter’ than it should be.

The postmodern world of simulation and specious spectacle berates our sensibilities constantly with the clutter of ‘noise’: aural, visual, and digital. Wherever we turn, ever more crass and unsubtle obfuscations increasingly disguise and distract us from fundamental ontological and epistemological errors and misconceptions. More so than ever, we need artists and philosophers to fine tune our minds, clear out the clutter, and help us maintain or regain our mental acuity and creative apprehension.

Thus, when we look at the paintings of Ian Wieczorek we are immediately called upon to start discriminating – between the real and the mediated, between personal and vicarious experience, between edges and surfaces, between foregrounds and backgrounds, between the abject and the object, between a greyish brown and a brownish grey. Sooner or later in this process of visual discrimination, judgement and discernment, our linguistic and communicative faculties probe the image for significance. Figuration is one of the most ancient and fundamental of visual modalities. It works, as Richter makes clear, even for ‘apparently abstract’ paintings. (Richter, 1995). Even a blank grey monochrome, in the present, can ‘figure’ and thus represent, other past monochromes, and thence by inference, all other

paintings. Similarly an ‘apparently’ figurative image can ‘figure’, represent, or now, re-present any level of abstraction the artist or we care to distinguish. In this discriminative complexity lies the depth and richness, and ultimately the ‘meaning/s’ of the artwork, and the levels we can, or care to, unfold, like fractals, depend upon the intensity of focus (magnification) we bring to bear upon the artworks.

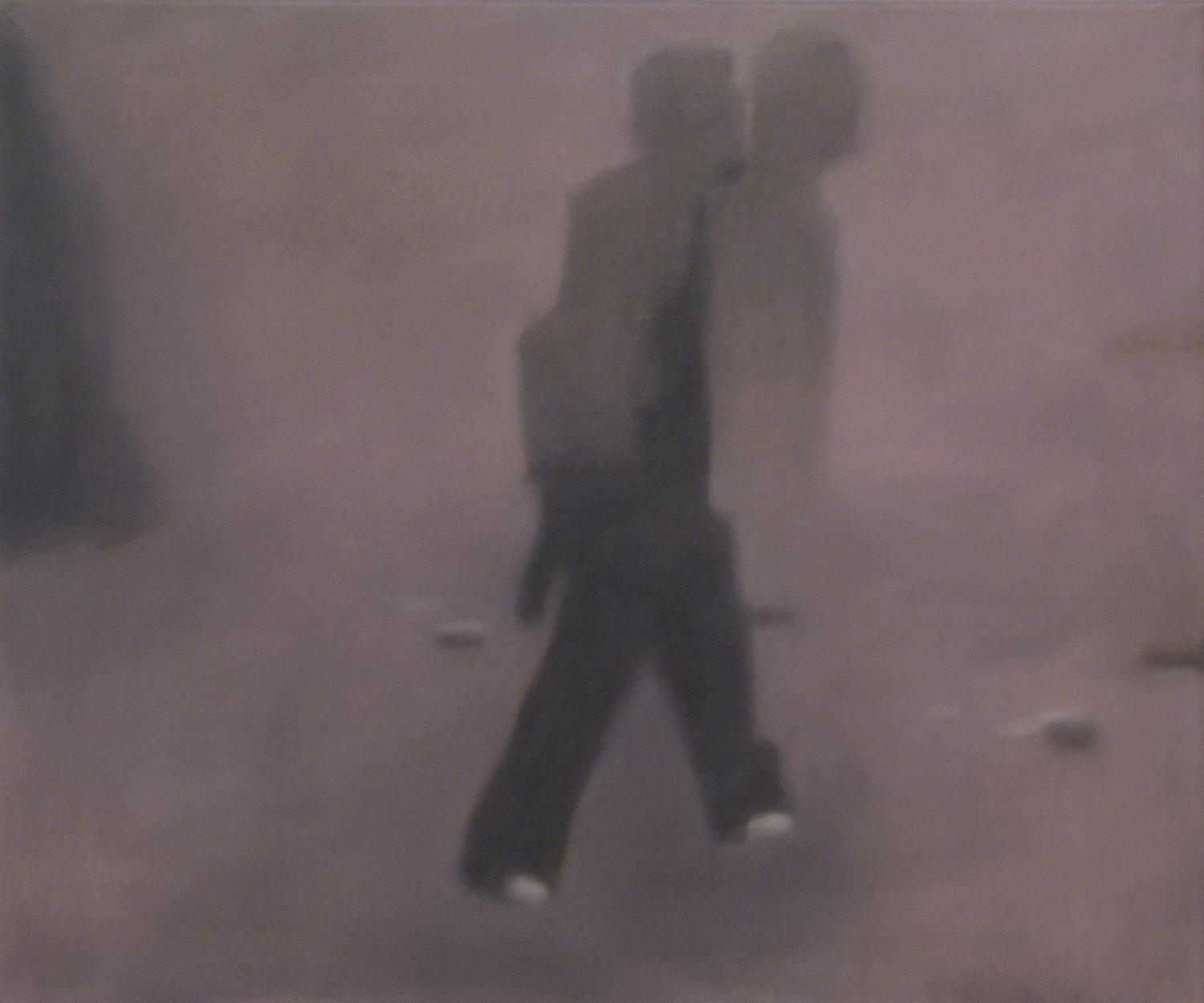

Wieczorek has been deeply affected by the simulative manipulation of the Gulf War. Baudrillard, the guru of simulation, famously wrote that “the Gulf War did not happen” (Baudrillard, 2004), by which he meant of course, not that real destruction was not meted out on real people and places, but that it was experienced by us, and indeed even by some of the combatants, ‘remotely’ like a video game. For Baudrillard, as for the Situationists, modern consumerist neo-liberalism has turned us into passive couch potatoes, spectating on our lives as they pass us by, and someone else makes a profit out of them. (Debord, 1984) As if trapped ‘inside’ the Plato’s cave of our TV sets, we look out through a ‘forest of signs’ - the random, ever-flickering pixels and symbolic orders - whereby everything we experience is encoded, compressed, mediated, and regurgitated for our catatonic observation.

The carefully crafted images in Wieczorek’s work seem unclear, but they are clearly images from the media: JPEGs downloaded from the internet or news media. Far from disguising their origins, they make evident their mediation: it is precisely the ‘overlay’ of media ‘noise’ which effects their apparent ‘blurriness’. They indicate a troubled and uneasy politics of hostages, missing persons, and surveillance footage: the world which takes place between our TVs and the media.

The fractal compression utilised in digital technologies enables the ‘lossy compression’ of ‘superfluous’ original data (Rankovic, 2006), such that the entire contents of the National Gallery in London can be made to fit onto a CD-ROM. This of course has many benefits, but it also means that the multiple levels of complexity with which the human eye and brain can operate are eventually limited by the loss, and our experience of the paintings in question is reduced and rendered less subtle. JPEGs conceal as much as they reveal, and in the end their referent slips away or is replaceable. In Wieczorek’s painting it is the mediated interference which remains to fill the loss, and become the real subject and site of fine discrimination.

Less subtlety in discrimination trains our brains to be less subtle in decision-making. A scientist who is unable to distinguish between the minutiae of complex data is not going to make subtle decisions. A banker who is not able to distinguish complexity is not going to be trusted with your pension plan.

Prof. Kenneth G. Hay, Leeds, 2012.

Ian Wieczorek is a visual artist living in Co. Mayo, Ireland. His practice is based primarily in painting, and more recently curation. Since 2003 he has exhibited widely in group and selected shows in Ireland, N. Ireland, Germany, France, Portugal, UK and China. Fragments is his 8th solo exhibition.

Wieczorek’s recent work explores the implications of contemporary visual vernacular, and how digital currency is becoming increasingly important in locating cultural identity. The works in this show are meticulously painted renderings of ‘found’ low resolution images harvested from the internet - stills from CCTV footage, missing persons photos, streamed news videos and mobile phone captures - that have been stripped of their specific contexts. The unposed images are often awkward in appearance, yet however unlikely or strange these moments appear, we recognise the embodied authenticity of everyday experience. Residual, ephemeral and ghostly, these frozen moments from random lives become more universal objects of contemplation.

“Wieczorek’s paintings represent images that are part of this currency of our everyday life, grabbed from the internet, the endless badly reproduced imagery of the virtual world. The paintings reflect the separation of appearance from its ‘truth’. In this way, the gap between the lushness of Wieczorek’s paintings and the brutality of what superficially seems to be their content reflect this sense of their being very much ‘of the world’.

One feature is their very painterliness, the blurring of the image. However, this blurring represents a deliberate and painstaking representation of the original poor quality ‘shorthand’ digital image.

These paintings combine autographic immanence with an aesthetic function far removed from the original intention behind the making of the images, thus creating a new work of art from them. The focus then comes on the picture itself, not the image, enabling us to think about the politics of the fragmenting Spectacleperhaps the only rational procedure left for thinking about painting in the contemporary world.”

- Dr. John Mulloy Lecturer in Art History and Critical Theory, Galway Mayo Institute of Technology, Ireland