Executive Summary

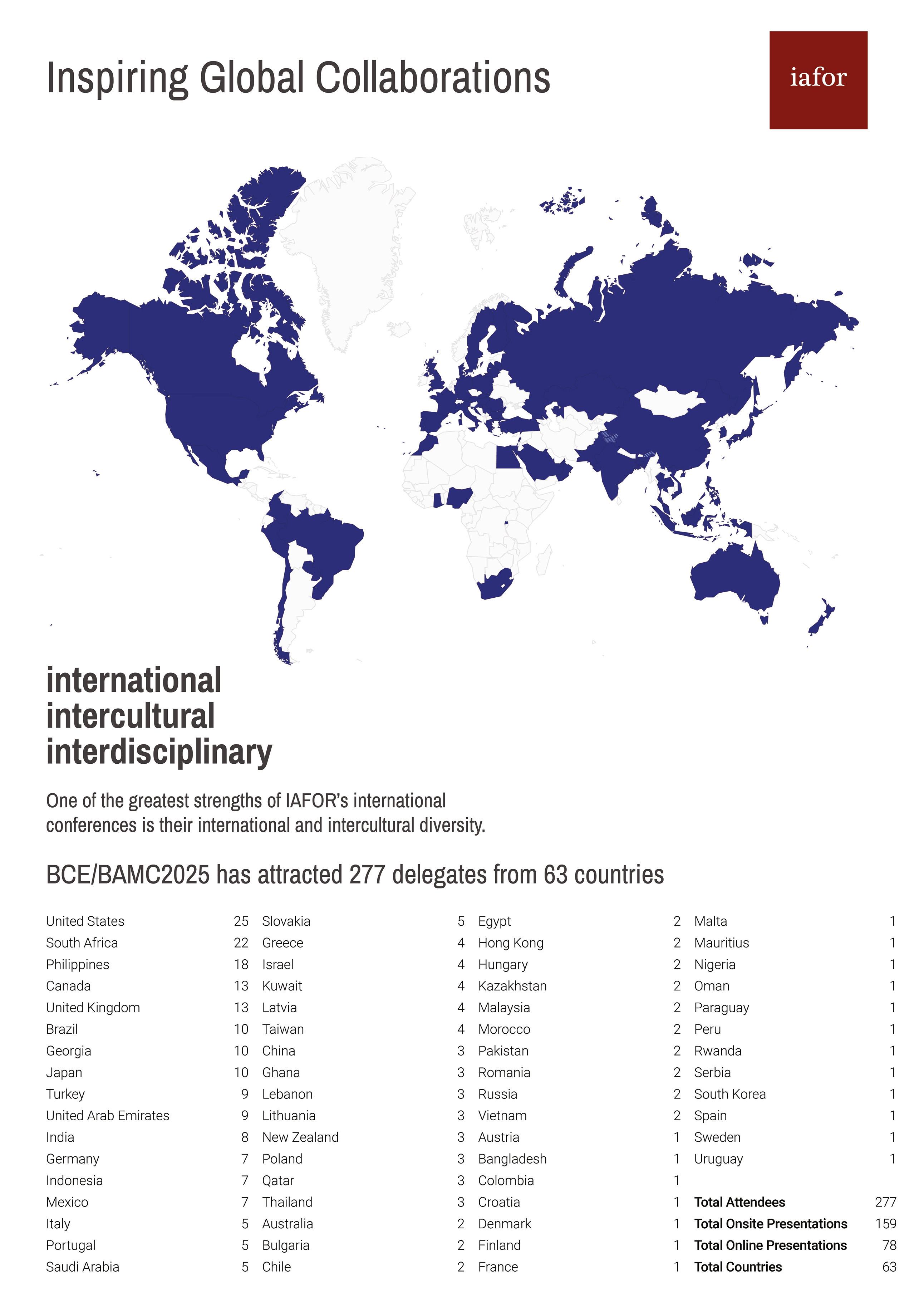

The 6th Barcelona Conference on Education (BCE2025) and The 6th Barcelona Conference on Arts, Media & Culture (BAMC2025) took place in Barcelona, Spain, from September 30 to October 4. Hosted at the Toulouse Business School (TBS) and the Hotel Barcelona Condal Mar, the conference gathered 277 delegates from 63 countries to discuss issues around the future of education and media in an era of increasing polarisation, geopolitical tension, and disruption caused by AI. Keynote and panel presentations explored questions of the relevance of education at a time when AI can outperform humans; the role of the university; what and how we teach students; the role of the media in politics; how we justify funding for education at a time of geopolitical turmoil and increasing spending on defense; how we deal with extremism; and how we can disagree well with each other.

In his keynote presentation, ‘AI-Assisted Instruction: Affordances and Issues’, Professor Carlos Delgado Kloos, Professor of Telematics Engineering at the Universidad Carlos III of Madrid, Spain, and UNESCO Chair on Scalable Digital Education for All, reflected on how the introduction of AI marks a fundamental shift in education and calls for a rethinking of both how and what we teach. While acknowledging the serious challenges and risks associated with AI, he presented concrete examples of AI-assisted instruction and emphasised the need to focus on supervision, judgment, and critical thinking (Section 2.1).

In the panel ‘Black Box Revolutions: Unpacking the Dynamics Between Design, Technology, Arts and Education in 2025’, Professor Heitor Alvelos and Dr Susana Barreto of the University of Porto, Portugal, Dr Paula Casal and Professor Carlos Alberto Scolari of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain, together with moderator Dr Joseph Haldane, CEO and Chairman of IAFOR, reflected on how artificial intelligence is reshaping creative education and practice across design, arts, and technology. The discussion explored current tensions between creativity and mimicry, ethics and inequality, and the influence of financial interests and the attention economy, while calling for a critical rather than apocalyptic approach to AI and for educators to help students engage with AI as a tool rather than as a master (Section 2.2).

In the panel ‘Embedding Social Responsibility: Service-Learning as a Tool for Knowledge Transfer in the New University Landscape’, Dr Dolors Ortega Arévalo and Dr Marta Ortega Sáez of the University of Barcelona, Spain, and Dr Catalina Ribas Segura of CESAG-Comillas Pontifical University, Spain, focused on service-learning as a way of rethinking the purpose of education and the role of the university in an era increasingly shaped by efficiency and productivity. The panellists highlighted service-learning as a socially engaged, interdisciplinary pedagogy that embeds teaching, learning, and knowledge production within communities, while also acknowledging the structural challenges it faces alongside its potential to foster active citizenship, ethical responsibility, and meaningful knowledge transfer (Section 2.3).

Dr Marcos Centeno-Martín of the University of Valencia, Spain, delivered a keynote presentation titled ‘Circulation of Japanese Newsreels on the War in Asia (1931-1945) in Spain’, in which he examined how newsreel images functioned as tools of propaganda and were repeatedly reinterpreted to serve shifting political interests, particularly in Francoist Spain. By tracing the transnational circulation of Japanese wartime footage and its changing meanings, he highlighted how images shape collective memory and drew connections to contemporary challenges facing journalism, media freedom, and democratic societies in today’s geopolitically volatile environment (Section 3.1).

Professor Anne Boddington, Provost of IAFOR, moderated the panel ‘Soft Power in Contested Spaces: Education and Arts for Peace’, bringing together Dr Maria Montserrat Rifà-Valls of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain; Professor Brendan Howe of Ewha Womans University, South Korea; and Dr Marcos Centeno-Martín of the University of Valencia, Spain, to examine how education, the arts, and culture operate as forms of soft power in contexts shaped by conflict, polarisation, and competing political priorities. The discussion engaged directly with questions of justification and value, particularly why education and the arts matter at a time of defunding and realpolitik, and explored how creative practices, cultural narratives, and pedagogical choices can challenge dominant discourses on migration, identity, and violence, while opening spaces for dialogue, empathy, and peace-building (Section 3.2).

The Forum session at BCE/BAMC2025 on ‘Global Citizenship: Education, Arts, Media, and the Rise of Extremism’ centred on questions about how people can disagree well, the role of education, arts, and media in addressing extremism, and what responsibility institutions hold in an increasingly polarised political climate. The session was moderated by Dr Melina Neophytou, IAFOR Academic Operations Manager, with Professor Brendan Howe acting as The Forum’s respondent. Participants shared reflections drawn from research, classrooms, artistic practice, and lived experience, emphasising empathy, trust, factual integrity, and the urgent need to recentre education and public discourse on human values rather than competition, fear, or market logic (Section 3.3).

1. Introduction

Technological disruptions have always transformed the way we live and see the world, but no other technology has fundamentally shaken up our economic, social, and political structures as much as AI has in the past few years. Apocalyptic visions of AI as something that ‘wants to destroy homo sapiens’, as Professor Carlos Alberto Scolari of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain, put it, see AI as taking over our jobs and inhibiting our critical and creative thinking. However, this negative, apocalyptic view also prompts us to ask very important and existential questions. What does it mean to be human, and what does it mean to be creative? What does the future job market look like, and in light of this, what, how, and why do we teach and learn? What is the role of education and the university? Are our current economic, social, and political systems sustainable? Plenary speakers at The 6th Barcelona Conference on Education (BCE2025) and The 6th Barcelona Conference on Arts, Media & Culture (BAMC2025) urged participants to abandon those apocalyptic views of AI and instead look at the opportunities that come with it. Innovations can happen during times of great disruption, and at the moment, we find ourselves not in an era of change but in a change of an era, according to Professor Carlos Delgado Kloos of the Universidad Carlos III of Madrid, Spain.

On the other hand, geopolitical tensions are also calling for concrete redefinitions of education and its purpose. At a time when national defence budgets are increasing at the expense of education and the arts, we are forced to quantify their value to justify their support. However, the value of education, especially within an atmosphere of technological disruption and increasing hostility and extremism, is measured beyond tangible outcomes, and is now higher than ever. Education and the arts as forms of soft power can be used to facilitate peacebuilding, which can start with learning on an individual level how to disagree well with others in society

and with people from different nations and cultures. As UNESCO Assistant DirectorGeneral for Education, Dr Stefania Giannini, mentioned in her welcome address at IAFOR’s Paris Conference (PCE/PCAH2025):

In this century, while governments are deeply concerned with defence and security, they forget that the best way to reach out to stability, peace, and security is by investing in a new dimension of global citizenship… and by investing in knowledge and people; what we call today “soft power”.

As Dr Marcos Centeno-Martin demonstrated in his keynote presentation, media and language can often frame narratives as instruments of propaganda. Media and the stories we consume are, therefore, also responsible for creating an unfavourable sentiment towards spending on education. Ironically, it is education and the arts that can help people decipher these strategies and critically examine who tells certain stories.

Plenary speakers at the Barcelona Conference all spoke for this intangible value of education and the arts to act as instruments of soft power wielded against hostility, extremism, war, and societal polarisation, justifying the need to stop defunding this sector. The BCE/BAMC2025 programme attempted to respond to questions on the relevance of education at a time when AI can outperform humans; the role of the university; what and how we teach students; the role of the media in politics; how we justify funding for education at a time of geopolitical turmoil and increasing spending on defense; how we deal with extremism; and how we can disagree well with each other.

IAFOR Chairman & CEO, Dr Joseph Haldane, delivered the Welcome Address at BCE/BAMC2025

2. The Future of Education

The growing presence of AI in education and creative fields raises fundamental questions about the role of education and the university in a world where many forms of knowledge production and problem-solving are increasingly automated. If AI is expected to replace or transform large parts of what humans do today in both labour and knowledge-production, this prompts deeper reflection on what we teach, how we teach, and why we teach students at all. Alongside concerns about ethics, authorship, inequality, and attention, AI has also fuelled apocalyptic narratives inherited from 20th-century popular culture, in which technology is framed primarily as a threat to human agency and meaning. According to Professor Carlos Alberto Scolari of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain, moving beyond these deterministic and dystopian visions allows for a more critical and constructive engagement with AI, one that recognises both its risks and its potential to reshape education in more reflective and human-centred ways. In this context, education cannot be reduced to adapting to technological change alone; it must also foster judgment, creativity, responsibility, and engagement with communities. These interconnected concerns were touched upon in the following three presentations, as plenary speakers urged for a radical rethinking of what, how, and why we teach today.

2.1. Education in an AI-Driven Era

Professor Carlos Delgado Kloos, Professor of Telematics Engineering at the Universidad Carlos III of Madrid, Spain and Director of the UNESCO Chair on Scalable Digital Education for All, gave a keynote speech on ‘AI-Assisted Instruction: Affordances and Issues’. The keynote speech addressed both the possibilities and potential issues that come with the introduction of AI in education, and what we can expect the future of education will look like.

He first presented a brief history of education’s evolution, focusing on the transition from traditional blackboard teaching to computer-aided instruction to AI-assisted instruction, stating that as we are entering a new ‘intelligent era, we have to rethink education’. Quoting the former CEO of Telefónica, José María Álvarez-Pallete López, he clarified that ‘it is not an era of change but a change of an era,’ where, above all, the method of learning and training has changed fundamentally. To make his point, he explained that AI differs fundamentally from traditional computing, as it works

Watch on YouTube

Professor Carlos Delgado Kloos Professor of Telematics Engineering at the Universidad Carlos III of Madrid, Spain and Director of the UNESCO Chair on Scalable Digital Education for All

in reverse, taking results and data to derive rules, rather than applying rules to data to get results. This means that ‘where there was only one truth, now truth is not absolute’. This has important implications for education. Professor Delgado Kloos quoted cognitive scientist Roger Schank to say that ‘only two things are wrong with education: what we teach and how we teach it. So basically, everything we do is wrong’. The introduction of AI into education has made this observation even clearer, and we need to rethink how and what we teach.

To address the ‘how we teach,’ Professor Delgado Kloos presented three ongoing projects at Universidad Carlos III of Madrid: the CharlieBOT, a 24/7 tutor trained on specific course content including MOOC videos, slides, and exams; an extension of Professor Eric Mazur’s peer instruction methodology from Harvard University to include AI as a third participant in student discussions; and a design agent for micro-credentials using CrewAI to help develop short upskilling programmes rapidly. Although these methods are not perfect according to him, they offer new ways of thinking about instruction that are more tailored to students’ current cognitive abilities: ‘So, the challenge for the coming years is how to adapt the techniques and methods that are well known for many years from the learning sciences to the AI era’.

As for the ‘what we teach,’ he emphasised ‘supervision, judgment, and critical thinking’ as essential skills for the future. As a provocation, he showed a nowdeleted video that mocked universities and university curricula, telling the story of the ‘Nothing University’: a university which awards students diplomas in ‘doing nothing,’ because AI can already do everything. However, his projected future is less dystopian: instead of relying on AI’s output, which essentially is problem-solving, he claimed that we need to shift our focus from problem-solving to verifying solutions. ‘Instead of learning how to compute, you learn the rules of computing to check or assess critically if something is correct. It is easier to check than to solve, but you have to teach different skills for this,’ he explained.

Despite serious issues and disruption caused by AI, such as national sovereignty, dependence, privacy, regulation, cognitive offloading, and laziness, Professor Delgado Kloos ended on a cautiously optimistic note that we have the capability of making AI’s initials stand for ‘Accessible and Inclusive’ instead. Quoting innovation entrepreneur, futurist, and academic researcher, Leah Zaidi, he concluded that ‘AI is not disrupting education. It is disrupting the industrial model for education, where we treat students like widgets on a conveyor belt.’ This is not necessarily a bad thing, according to him. ‘We have to take the opportunity to humanise education and take advantage of the affordances of AI, but knowing clearly the risks, and to rethink what education is for and why it matters’.

2.2. AI in Creative Education Classrooms

A panel titled ‘Black Box Revolutions: Unpacking the Dynamics Between Design, Technology, Arts and Education in 2025’ further explored and particularly highlighted how artificial intelligence is transforming creative education and practice across the fields of design, technology, and the arts. The panel invited Professor Heitor Alvelos and Dr Susana Barreto of the University of Porto, Portugal, Dr Paula Casal and Professor Carlos Alberto Scolari of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain, and moderator Dr Joseph Haldane, CEO and Chairman of IAFOR, to discuss whether AI represents genuine creativity or merely sophisticated mimicry, with the panellists referring to hallucinations and questioning what creativity means. The panel addressed a push and pull dynamic in education, where AI can eliminate and reinforce inequalities, raise issues of ethics and authorship, and help students see AI as a tool rather than a master. The discussion also examined apocalyptic visions of AI, the attention economy, and how platforms encourage continuous interaction in a deeply competitive environment where financial interests shape how AI is adopted.

Professor Alvelos opened with a provocative demonstration, revealing to the audience that he had used ChatGPT to write the panel’s abstract. He questioned whether AI represents genuine creativity or merely sophisticated mimicry, introducing the concept of ‘hallucinations’ as AI’s departure from factual reality. To benefit from this dilemma, he invited panellists to discuss what creativity means. In his words, ‘creativity may mean different things to different people. Despite the fact that it’s quite ambivalent and subjective, people tend to agree that it’s a good idea’. Replying to Professor Alvelos’s comment on creativity, Professor Scolari stated that AI’s weakness in producing good literary work and ‘hallucinations’ should not be condemned, but seen as a source of inspiration and creativity. According to him, it is from those hallucinations that great ideas can be born.

Dr Barreto offered her insights on how AI has transformed her classroom by drawing parallels between current AI adoption and the introduction of Adobe Photoshop in early 1990. She is currently observing a ‘push and pull dynamic’, where students are simultaneously fascinated by AI’s creative potential but have issues with ethics and authorship. She emphasised the educator’s role in helping students view AI as a tool rather than a master: ‘Let students explore freely and creatively with AI. Educators should help with framing their creativity and with ethical aspects. This will help them see AI as a tool rather than a master’.

From left to right: Dr Joseph Haldane of IAFOR, Japan, Dr Paula Casal and Professor Carlos Alberto Scolari of Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain, Professor Heitor Alvelos and Dr Susana Barreto of the University of Porto, Portugal

Watch on YouTube

Dr Casal presented a rather mixed opinion about AI’s impact in the classroom, noting that AI can both eliminate and reinforce inequalities. Dr Casal reported using ChatGPT Pro and Mistral for creating visual PowerPoints and observed significant improvements in classroom participation, especially among non-native English speakers and women, in their ability to interrupt. ‘AI has eliminated the differences that I find are very unjust between native speakers and people who are speaking a second or third language… [also] women always want to discuss in groups, because they want to check their ideas with somebody. Now, they ask ChatGPT quietly without disrupting the class.’

However, for more sophisticated and complex authors and philosophers, AI gets it wrong all the time. ‘AI cannot understand subtle differences, especially when talking about ethically controversial topics, such as abortion or euthanasia… It is always pushing you to the conservative side, always reinforcing stereotypes. There is a reproduction of inequalities and the points of view that are more represented. We have to be aware of that’.

Professor Scolari instead addressed the apocalyptic cultural narrative surrounding AI that, in some ways, obscures the opportunities that come with this transformational technology:

Our conception of AI comes from 20th-century mass culture. We have a negative, apocalyptic vision of AI coming from movies like Skynet, iRobot, and the Matrix: AI wants to destroy homo sapiens… I think we have a lot of work to do to change this view. We need a critical approach; we do not need an apocalyptic approach.

He noted that students primarily learn AI usage through platforms like TikTok rather than formal education, highlighting the urgent need to integrate AI into curricula faster than the 10-15 years it took for previous digital technologies. ‘How can we accelerate this process?’ he asked, adding that ‘IAFOR is a great place to discuss this’.

Inspired by a previous question raised during Professor Delgado Kloos’s presentation about how AI cannot and should not be regarded as ‘something that shows up out of nowhere without any kind of interest or agenda,’ Professor Alvelos noted that

Professor Heitor Alvelos and Dr Susana Barreto of the University of Porto, Portugal

there is a clear financial interest that we should not be underestimating, which is closely related to the competitive educational environment driving AI usage: ‘Isn’t it interesting that we hear about co-designing and cooperating and creativity, and yet we are so immersed in a deeply competitive environment where students, essentially, are hunting down that job that will miraculously put their lives together?’

Prompted by this, Dr Haldane posed the question of whether there were times when ChatGPT would ‘shut you down’ for pursuing lines of questioning or lines of arguments, touching upon the concept of the attention economy. Dr Casal replied that, indeed, ChatGPT asks her on a daily basis if she really wants to be ‘that polemical,’ dismissing her initial arguments and redirecting her to other activities. Dr Barreto also agreed that AI is not capable of providing her with critical, provocative, or argumentative opinions when asked, pointing her to other directions. Professor Scolari identified big tech companies like Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Meta that have social media platforms from which they gain not only the attention of the user but also a lot of user data as drivers of the attention economy. He noted that the only big company that does not have social media for getting data from users is OpenAI. ‘It seems they want to transform ChatGPT into a social media platform. Imagine ChatGPT with comments exchanged between users because they know that increases the time you spend there. And the time that we spend there is time that we do not spend on other platforms,’ he concluded.

Professor Alvelos also discussed the attention economy underlying AI platforms, noting how interfaces encourage continuous interaction through suggestions for further engagement. ‘This leads me to a really interesting question connected with Professor Delgado Kloos’s keynote,’ he said. ‘If we have that hypothetical Nothing University where AI does everything, what are we going to do with our free time?’ He went on further to critique the assumption that wealth would be redistributed evenly, which he thought was ‘a post-war ambition, very honourable but very wrong. Rather than ask about those who cannot afford to use AI, how about asking about those who can afford not to use AI as a benefit? I think we should think about that for a bit’.

Dr Paula Casal and Professor Carlos Alberto Scolari of Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain

2.3. Service-Learning as a New Educational Focus

The discussion around the future of education invited conference participants to question what its purpose should be, and in turn what the role of the university should be, in this era defined by increasing attention on efficiency and productivity and a disregard for human values. A panel titled ‘Embedding Social Responsibility: Service-Learning as a Tool for Knowledge Transfer in the New University Landscape’ further explored a potential role of education and the university through the lens of social responsibility and service-learning. Panellists Dr Dolors Ortega Arévalo and Dr Marta Ortega Sáez of the University of Barcelona, Spain, and Dr Catalina Ribas Segura of the CESAG-Comillas Pontifical University, Spain, made a good case for focusing on service-learning and social responsibility as a form of giving back to communities, in which educational institutions, teachers, students, and the whole knowledge production process are embedded.

Starting with a definition of service-learning, Dr Ribas Segura defined servicelearning as a pedagogical methodology used in universities and educational institutions worldwide based on two main principles: service to the community and learning of a curriculum by students. It differs from volunteering in that, aside from solidarity service and active participation (what she called the ‘heart’ and the ‘hands’), it also includes a curriculum and a learning component (the ‘head’). With these components in mind, students and associations work with the community to solve problems instead of working for the community.

Dr Ortega Arévalo presented a brief literature review of service-learning that highlighted the trend and relevance of service-learning as a discipline today. While it started as scattered pedagogies over seven decades ago, it has matured into an interdisciplinary field, with 75% of the field’s research conducted only after 2010, ‘mirroring global interest in active and experimental pedagogies,’ she explained. This

Panellists Dr Marta Ortega Sáez and Dr Dolors Ortega Arévalo of the University of Barcelona, Spain, and Dr Catalina Ribas Segura of the CESAGComillas Pontifical University, Spain

Watch on YouTube

is consistent with various debates within IAFOR regarding the rise of interdisciplinary teaching, learning, and research, and the need to ‘cultivate active citizenship, interdisciplinary competencies and ethical responsibility among students,’ something which Dr Ortega Arévalo claimed service-learning can do.

Also consistent with what participants have discussed during IAFOR’s Forum sessions at the previous 2025 Paris and London Conferences regarding challenges of making interdisciplinarity work is the fact that service-learning, just like most interdisciplinary fields, is underfunded and lacks recognition in promotional systems. It also lacks variability in terms of the countries that produce related research: roughly 70% of publications originate in the United States, and 96% are published in English, even though in the past few decades, there has been a notable growth of interest and application across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. However, ‘this shift offers new opportunities to examine how culture, policy and local priorities shape servicelearning designs and outcomes,’ Dr Ortega Arévalo said, advocating for a more inclusive research landscape.

According to the panellists, Spain has emerged as Europe’s leading producer of scholarship in service-learning since 2000, and as one of the most successful European countries in its institutionalisation. To demonstrate how Spanish universities have approached the integration of service-learning into formal curricula, Dr Ortega Sáez outlined various courses that have been introduced at her institution: ‘Sharing Ideas’ (informational talks and workshops for secondary school students), ‘Service-Learning Commitment and Social Transformation’ (involving environmental challenges at San Adria de Vazos beach), and the Service-Learning Chair (training, research, and knowledge transfer). Dr Ribas Segura also introduced two courses related to service-learning taught at her institution, the Comillas Pontifical University in Mallorca: ‘Service-Learning Existing While Ensuring No One’s Left Behind,’ involving sports science and primary education students working with Caritas; and ‘Media Report’ and ‘Documentary and Other Nonfiction Forums’ for media studies students.

Dr Ortega Sáez concluded by stating that, although service-learning as an interdisciplinary field has a lot of challenges to overcome, ‘the social and personal benefits outweigh the difficulties, as this is a way for organisations to become more known and for teachers and students to reach and give back to the community’.

While many questions remained unanswered during these three sessions, such as what creativity is, how to deal with AI in this attention economy, what we will do with our free time once AI takes over, and how to make interdisciplinary research and teaching more viable and attractive, Dr Haldane was hopeful that discussions at the intersection between technology, AI, and humanity and human intelligence ‘will help us find answers to questions from the small and seemingly unimportant to the large and meaningful’. As these discussions correspond to two of IAFOR’s themes for 2025-2029, they will continue to be addressed in IAFOR’s future conference programmes.

3. Narratives of War and Extremism

In a time of growing geopolitical tension, polarisation, and extremism, the ways images, stories, and cultural narratives circulate play a powerful role in shaping how conflicts are understood and remembered. Education, media, and the arts are not neutral in this process: they can reinforce dominant perspectives, but they can also challenge them, and create open and safe spaces for dialogue. At the same time, universities and educators are increasingly asked to justify education’s value in contexts where national narratives, funding priorities, and political agendas frame education as expendable or secondary. Whether through the reproduction and repurposing of propaganda images, the use of education and the arts as forms of soft power in peace-building, or the creation of spaces where disagreement can be expressed without turning into hostility or extremism, plenary speakers reflected on how education might be defended, reimagined, and practiced as a public good, and how we can disagree well with each other in uncertain and contested times.

3.1. Media and Propaganda

In his keynote presentation titled ‘Circulation of Japanese Newsreels on the War in Asia (1931-1945) in Spain’, Dr Marcos Centeno-Martín of the University of Valencia, Spain, told a story of a time during WWII, ‘when cinema and images [newsreels] emerged as a modern tool for propaganda’. By showing examples of how images that were being produced by the Japanese Empire were reinterpreted during and after WWII, he drew parallels to Francoist Spain.

Dr Centeno-Martín explained that Spain recognised the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in 1937, making it one of only three countries (alongside Nazi Germany and Italy) to do so. This diplomatic relationship facilitated the circulation of Japanese newsreels to Spanish audiences through Nazi Germany. The Spanish Fascist Party Falange used these materials as part of their propaganda strategy to establish their legitimacy, particularly since they lacked their own film production capabilities in the early years of Franco’s regime. He proceeded to show concrete examples of how the same Japanese footage was reinterpreted to serve changing Spanish political needs.

Dr Marcos Centeno-Martín of the University of Valencia, Spain

Initially (1939-1943), the newsreels emphasised Japanese victories against the British, feeding Spanish fascist fantasies about potentially taking Gibraltar. However, after 1943, when the Axis defeat became apparent, Spain strategically repositioned itself. By 1945, Spain declared war on Japan following the massacre of Spanish civilians in Manila, using this as justification to align with the Allies and secure entry into the United Nations in the 1950s.

Dr Centeno-Martín’s analysis revealed how images do not simply present reality but represent it from specific perspectives, changing meaning as they circulate across different contexts. Global circulation of propaganda images plays an important role in shaping collective memory. The same visual materials can serve completely different political narratives depending on their context of reception. Spain was not the only country in which such a reinterpretation occurred. It was at a time of the booming newsreels industry (news showed in theatres) that the United States had also repurposed Japanese images and newsreels of the Nanjing massacre in China to mobilise the American public opinion about the necessity to enter World War II. According to Dr Centeno-Martín, ‘this transnational and interdisciplinary approach to these images is very interesting because they reveal this global circulation of images… which is key to understanding how we socialise or how we create collective memories—the socialisation of memory through images. They don’t tell us much about what was going on in Asia, but they tell us something about the changing needs that were taking place in Spain’.

What does this mean for the news we consume in today’s geopolitically volatile environment? ‘This may be surprising,’ Dr Centeno-Martín revealed in a postconference interview, ‘but during WWII, journalists had more freedom to move around and film whatever they wanted. Today it is more difficult to do this than before’. He proceeded to explain how the freedom of the press became a big problem for the United States during the Vietnam War, where journalists filmed both sides of the conflict, causing great discontentment among US citizens and leading to the US Army’s withdrawal. ‘Since then, the Americans said there would be no more interviews on the other side,’ using security reasons as an excuse for journalists to stay with the Army at all times. While official news became more limited in its coverage, Dr Centeno-Martín argued that, fortunately, today, we have social media and ‘individuals who can act as new agents for providing information outside of the main agencies’. However, there have been attacks by state governments on both formal journalists and individuals, and the Geneva Convention that protects journalists is often violated, he explained. This is a real problem we are facing in journalism, media, and democracies today that needs to be addressed, Professor Centeno-Martín concluded.

3.2. Education and Arts for Peace

In a panel titled ‘Soft Power in Contested Spaces: Education and Arts for Peace’ moderated by IAFOR’s Provost, Professor Anne Boddington, panellists Dr Maria Montserrat Rifà-Valls of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain; Professor Brendan Howe of Ewha Womans University, South Korea; and Dr Marcos CentenoMartín of the University of Valencia, Spain, addressed an ongoing dialogue within IAFOR revolving around the role and use of soft power in education, the arts, and culture. At IAFOR’s conference in Paris, the UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Education, Dr Stefania Giannini, reminded us that hard power is not necessarily the best way to engage, communicate, and interact with others, especially in our increasingly polarised world. According to her, soft power as exercised through education, culture, and the arts can lead to innovative and peaceful solutions to conflict resolution. In this context, the creative industries and arts can generate alternative narratives, awareness building, whether that’s the real-life stories of refugees, various forms of creative activism, or public forms of communication, such as murals or documentary films.

‘But soft power is often either soft in its language or gentle in its messaging,’ Professor Anne Boddington stated in her opening remarks. ‘It’s often hard-hitting, contested, and controversial. It’s often uncomfortable as a form of public or community conscience’. Within the current polarised context, educators have an even greater mission to create future citizens and societies that are respectful and tolerant. According to Professor Boddington, ‘as educators, what may be more important, far more so than the subject knowledge we deliver, is what and how we deploy the knowledge we have, how we learn, how we relearn, and how we educate our students to have a dialogue, to disagree agreeably and respectfully, to practice empathy and respect rather than endlessly circulate within those bubbles of friends’.

Increasingly, arts, education, and culture must compete for space and for funding with other sectors, whether that is health, social care, or defence. Providing some hard data, Professor Boddington highlighted that the economic justification for backing arts and education does exist: creative industries contribute 126 billion pounds (5%) to the UK economy, while in Spain, the arts contribute about 34 billion euros (3.2%) to the economy, in comparison to football (1.5%).

Dr Marcos Centeno-Martín (University of Valencia, Spain), Dr Maria Montserrat Rifà-Valls (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain), and Professor Brendan Howe (Ewha Womans University, South Korea)

Watch on YouTube

Dr Rifà-Valls identified four key areas for examining visual culture’s role in dismantling narratives of conflict and war, further providing a justification for funding education and the arts. First, she touched upon the role of artists in subverting imperial narratives and geopolitical power by challenging borders, exposing structures of war, colonialism, and racism, and engaging with contemporary conflicts. Second, she mentioned that public pedagogies and art educators have the potential to act as cultural workers who foster peaceful societies and social transformation. Third, the plurality of childhoods and school environments are areas where children’s cultures respond to political, ecological, social, and economic crises, and where the architecture and ecological orientation of schools actively shape resilience, community, and learning. Finally, she provocatively questioned whether ‘soft power, a particularly visual popular culture of children and young people, is an instrument to regulate their lives, or an opportunity for them to transgress the limitations imposed by capitalism’.

In a provocative turn, Professor Howe opened his argument with the question: ‘Why bother with art and education? What’s the justification for it?’ Although education and artistic expression are ‘universal normative human rights’ and access to them has been widely endorsed, ‘that may no longer be enough,’ he said. While a lot of people may argue that we do not have to justify what is a normative human right, Professor Howe argued that ‘at a time when global geopolitical challenges and resurgent populist nationalism in domestic politics have forced a refocusing of policy and budgetary agendas back towards realpolitik and national interest, the call to do the morally right thing may no longer be sufficient.’ Instead, ‘stronger rational interest arguments must be made for the prioritisation of education and the arts’.

According to him, the fact that recent events have linked education with death is a logical and valid argument to make for funding education and the arts. The ‘horrendous’ shooting of Charlie Kirk while debating on a university campus, the ‘massacre’ of students and other civilians on campuses in Gaza, and mass shootings of students and educators are all incidents that highlight that ‘education is not just important, it is quite literally a matter of life and death’. According to Professor Howe, it is through education and the arts that people are able to discover ‘shared interests rather than adversarial positions,’ and that ‘this is where the future of peacebuilding can be found’.

In response to the two arguments, Dr Centeno-Martín highlighted an area in which conflict and contestation are currently clearly visible in Europe: the migration

Dr Maria Montserrat Rifà-Valls (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain), and Professor Brendan Howe (Ewha Womans University, South Korea)

issue. According to him, there is a disconnect between perception and reality in contemporary narratives of a migrant ‘invasion’ in Europe. Noting that Spain’s ageing society demographic challenges are similar to those of South Korea and Japan, he questioned why migration is not framed as an opportunity rather than a threat. With a question directed to the panellists, he asked how education and the arts (soft power) can challenge dominant anti-migration narratives, when visibility has been artificially increased to create a perception of larger problems than actually exist.

‘We should introduce migrant artists and artists from different nationalities, origins, social classes, genders, races, and so on in the national curriculum,’ Dr Rifà-Valls responded. She offered the example of a proposal developed by the Barcelona municipality to work with the Top Manta Collective of Sub-Saharan workers to produce clothing to sell. Eventually, this initiative enabled these Sub-Saharan migrants to create a new economy based on solidarity and cooperation. Similarly, Professor Howe mentioned that the data speaks for the acceptance of migrants, as it was proven that migration overwhelmingly benefits societies economically, socially, and culturally. ‘I think you need to look at the importance of migrant communities in reinvigorating social life in countries that, if you don’t continue evolving, you will stagnate. And I think that even super-aged and super-conservative societies like Korea are beginning to realise this,’ Professor Howe stated. He concluded by saying that it is important to educate society using some of these facts, but also to educate governments ‘to learn, to be educated, to evolve in response to not the migrant challenge,’ but the migrant opportunity.

In a closing statement, Professor Boddington offered a final provocation: ‘Who will listen to this, and who cares? Can we, with soft power, do anything about it? Is the answer a quick no? Or is it something where we can actually act? And does it matter?’ Professor Howe responded by placing the blame on those who should be promoting art and education, and their failure to do so in a way that shines the best light on immigration. ‘It’s not enough to say we’re going to continue putting on Hamlet, but we’re going to have actors from different ethnicities playing the roles. It’s not enough. All that’s doing is putting immigrants into other versions of us, instead of asking how immigration can make us better,’ he stated. His solution is to empower immigrants to be ‘their own best ambassadors’.

As writer and poet Gloria Montero put it during the Q&A session, ‘these questions that the panel brought up are terribly important to us as humans. We now live in a society that really only sees power, how to grow, get better, and get more money. We’re really losing and suffering, each one of us’. It is very important to keep asking these questions and to try to change popular narratives of conflict, despite the feeling of helplessness. The Forum session at the BCE/BAMC2025 conference attempted to make a first step in this direction, and IAFOR is committed to addressing questions of belonging and of conviviality as we enter 2026.

IAFOR’s Provost, Professor Anne Boddington, moderated the panel

3.3. Disagreeing Well in a Polarised and Increasingly Extremist World: Insights from the Forum

The Forum returned to Barcelona for a second year with a discussion on ‘Education, Arts, Media, and the Rise of Extremism.’ Driven by our IAFOR community, The Forum sessions are one-hour moderated discussions among delegates on pressing issues attuned to the local context but with a wider resonance. The topic for the Forum session in Barcelona was motivated by the need to address how to overcome challenges in an increasingly polarised world, particularly polarisation in domestic politics. Professor Brendan Howe joined Dr Melina Neophytou, IAFOR’s Academic Operations Manager, in leading the session in Barcelona, which reflected on the growing internal divisions and ‘increasingly extreme perspectives’ in nations across the globe.

With the central question of how to ‘disagree well’, participants stressed the importance of empathy and cultural awareness as a foundation for dialogue. In the icebreaker session of The Forum, a participant shared that:

We are all different, and we come from different cultures. Because of that, it is very likely that we think differently because of our different values and beliefs. So, listening to others with empathy and understanding and not judging them is important. We don’t need to show the other that ‘I know better than you’.

- A delegate from Lebanon

When participants were asked what they value most in a debate, the strongest preference was for finding common ground (42%), followed by understanding others (26%), being understood (21%), and winning the argument (11%). This prompted reflection on whether consensus should be the goal of debate. A delegate from Australia questioned this assumption, arguing:

If we are really seeking to find common ground, aren’t we then trying to reach a particular consensus? I think understanding others may trump finding a common ground. Ultimately, the value in a debate is being able to respect the other person’s position, not necessarily agree with it, but understand it, and move on. So, by finding the common ground, we are probably seeking a consensus of some sort, and I have to disagree with that.

- A delegate from Australia

The discussion then turned to how people can disagree well in a deeply polarised environment. Several participants emphasised the role of facts, emotional discipline, and openness to complexity.

How do you disagree well? The most important thing is understanding each other. But in a polarised world, it is more important that the information that is being argued, debated, or presented must be a fact, rather than an interpretation of it that might be mis- or disinformation.

- A delegate from the United States

Building on this, other participants noted the importance of separating ideas from individuals and that there is no single universal truth:

Disagreeing well is being able to differentiate between the ideas and the person, so the emotional and the logical. And what is maybe going on now, the attack on a person, or the weakening of the other, is the opposite of that.

- A delegate from Portugal

There are multiple truths in social science. We can respect that, and we should have multidimensional thinking. For example, right now we have such furious arguments about migration. People have so many varied positions on this, some political, some about poverty, etc. So, we cannot conclude that there is only one truth.

- A delegate from Ethiopia working in the United Kingdom

Participants were also asked to reflect on where they most often experience peaceful dialogue despite disagreement. Most pointed to research (34%) and classroom settings (31%), followed by professional environments (17%), art and cultural projects (11%), and community gatherings (6%), while none identified online spaces. This highlights the immense work and responsibility falling on moderators of online communities, as well as those who manage online platforms, to ensure a convivial space for dialogue in settings where our identities can be hidden and protected from public scrutiny.

Attention then shifted to the role of educators, artists, and professionals in intentionally creating environments where people feel able to speak freely and safely. Practical examples highlighted the importance of trust and moderation.

As an educator and artist, what I do in my classroom of students, mainly from South and Southeast Asia, is I create a safe space and tell them, ‘whatever you have to say, speak about it here, but whatever happens in the classroom, stays in the classroom’. I once had a student from Pakistan and one from Bangladesh who had a debate, and I told them, ‘Okay, this is your perspective - now, what is the commonality between you two?’ In the end, they became really good friends. It’s about allowing them to speak, knowing that they are safe. When there is a conflict, we as educators need to be the moderators. Students need to trust us.

- A delegate from the United Kingdom

To be an educator, an artist, or a professional means that you are in a position of power, able to influence others. So, empowering people and maybe softening others that you can influence is something we should do. I’m thinking of artists who are very close to policymakers. As educators, artists, or professionals, we need to use our power and influence.

- A delegate from Romania

How to ‘disagree well’ also extends to incredibly difficult conversations around contention, which can often be emotionally charged. One participant from Lebanon questioned whether dialogue is even possible ‘with someone who wants to kill you,’ drawing on their lived experiences related to the Gaza–Israel conflict and arguing that all this debate about ‘disagreeing well’ is useless in the face of fanaticism. In response, another participant reflected on the fragility of so-called safe spaces:

In order for us to create a safe space, we as educators need to feel safe. I think the genocide in Gaza and the situation in Lebanon, as the woman said before, show us that there is no safe space and that we cannot address issues in a safe manner. In the academic world, we also don’t feel safe talking about these things. I think it also depends on the themes: if the themes conform with the system, then we can discuss, but if the themes of discussion don’t conform with the system, it is very difficult to address issues. There is a big difference between a point of view and facts. We have facts; the genocide is a fact, not a point of view. If we are all on the same page about this, then we can start creating a safe space to discuss it.

- A delegate from an unidentified country

Finally, participants reflected on the deeper mindsets shaping institutions and society more broadly. When asked what the biggest mindset problem is in our institutions and society, many identified attitudes of ‘change is risky’ (33%) and ‘money matters most’ (23%) as key barriers, alongside ‘my rights matter most’ (17%), ‘we must avoid uncomfortable conversations’ (13%), and a fixation on ‘victory at all costs’ (10%).

In response, the discussion called for a fundamental shift in how education, media, and political discourse are structured:

We need to stop thinking of the education system as a corporation, education as a product, and students as clients.

- A delegate from the United States

I agree. When people focus more on collaboration, we can all learn from situations rather than compete. We can also get things done. Whatever needs to be done is better done in harmony than in competition.

- A delegate from Romania

One of the basic things we all need to change is to stop focusing on money and capitalism, and focus on humans. What is it that we need? What is it that our youth needs? What do we see as our future? We have no jobs, and yet we are getting AI to do everything. We are teaching and training young people… but why are we doing all of this? So many people are aware of rising drug addiction. I asked my students, and they said, ‘We have no jobs, so what can we do? We need a way to calm our minds.’ In the process, they become addicted. We really need to focus on humans first.

- A delegate from the United Kingdom

This Forum session evoked emotions of helplessness, much like author and poet Gloria Montero had previously mentioned, speaking to the gravity of the issue of extremism and the failure of our institutions and systems to create safe spaces for dialogue and inquiry. Ultimately, the key takeaway from this discussion session is the need to continue addressing issues of extremism and actively trying to create safe spaces, while rethinking our entire educational, economic, and social systems. Recentering the focus on the human will be key in this endeavour and in the coming decades.

4. Conclusion

As the world is becoming increasingly polarised and contentious, remembering what it means to be human and refocusing our economic, social, and political institutions on human values becomes more and more critical. Governments are increasing spending on so-called hard power (military offence and defence) and defunding areas of soft power like education and the arts. This shift contrasts societal needs and desires, which are often expressed in safe spaces created by education and the arts. Taking these safe spaces away means taking away valued spaces for meaningmaking, dialogue, and social cohesion, giving way to extremism and hostility. If the goal is to bring peace internationally and domestically, defunding education and the Arts further most certainly has the opposite effect, and enables governments to justify more spending on hard power.

This dynamic was explored throughout the discussions at BCE/BAMC2025, with education, the arts, and media as enablers of critical and creative thinking, expression, negotiation, disagreement, and introspection. These practices are fundamental in today’s context of technological disruption by AI, distorted media narratives, and emotional reasoning. While the dominant discourse on AI sees this technology as something to be feared and eroding human thinking, creativity, morality, and agency, it also makes visible why education needs to be redefined, and why recentering our systems around human values is important. In other words, it highlights the value of being human.

Our task, now, is to define what exactly it means to be human in this completely new context of AI and a multipolar world order, so that we can recentre our social, economic, and political systems around human values we define as essential for a peaceful and meaningful coexistence. Through our four themes of Technology & Artificial Intelligence, Humanity & Human Intelligence, Global Citizenship & Education for Peace, and Leadership, IAFOR will continue to address these critical issues and questions around peacebuilding, being human, and coexisting among people with different backgrounds and ideas.

Appendix I. Affiliations by Region

Africa

Egypt

The American University in Cairo

Ghana

University of Cape Coast

University of Education, Winneba University of Ghana

Mauritius

Open University of Mauritius

Morocco

Mohammed V University in Rabat

Moulay Ismail University

Nigeria

Rev. Fr. Moses Orshio Adasu University

Rwanda Ubuntu Cultures & Academics

South Africa

AROS

Central University of Technology

Mangosuthu University of Technology

North-West University

Sol Plaatje University

University of Johannesburg

University of KwaZulu-Natal

University of South Africa

University of the Free State

Walter Sisulu University

South America

Brazil

Community University of the Region of Chapecó

Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Goiás

Federal University of Pará

Federal University of São Carlos

Federal University of Technology – Paraná

Fluminense Federal University

Goiás State Legislative Assembly

National School of Public Administration

Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná

São Paulo State University

Chile

University of Santiago, Chile

Colombia

University of Cartagena

Paraguay

National University of Asunción

Peru

Ricardo Palma University

Uruguay

University of the Republic

Oceania

Australia

Monash University

University of New South Wales

New Zealand

Manukau Institute of Technology

Asia

Bangladesh

Eastern University

China

New York University Shanghai

Zhengzhou University

Hong Kong

Hong Kong Metropolitan University

The Education University of Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

India

Central Institute of Himalayan Culture

Studies

Ethiraj College for Women

Nirma University

Panjab University University of Calicut University of Delhi

Indonesia

National Institute of Public Administration

Nusa Cendana University

Satya Wacana Christian University

Universitas Gadjah Mada

Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia

Universitas Terbuka

Maranatha Christian University

Israel

Ariel University

Azrieli College of Engineering Jerusalem

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

Kibbutzim College of Education, Technology and the Arts

Japan

Keiai University

Kindai University

Kokushikan University

The University of Osaka

Tama Art University

Tokushima University

Waseda University

Kazakhstan

Abai Kazakh National Pedagogical University

Al-Farabi Kazakh National University

Kuwait

Kuwait University

Lebanon

Rafik Hariri University

Saint Joseph University of Beirut

Malaysia

Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah

Universiti Putra Malaysia

Oman

Oman College of Health Sciences

Pakistan

Emerson University Multan

Virtual University of Pakistan

Philippines

Bicol University

Cotabato Foundation College of Science and Technology

De La Salle University

Enderun Colleges

Ifugao State University

Integrated Bar of the Philippines

Mapúa Malayan Colleges Laguna

Mapúa Malayan Colleges Mindanao

National University

Polytechnic University of the Philippines

Rizal Technological University

University of the Philippines Los Baños

Qatar

Weill Cornell Medicine

Saudi Arabia

King Abdulaziz University

King Saud University

Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University

Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University

Prince Sultan University

South Korea

Kyung Hee University

Taiwan

Chaoyang University of Technology

National Chin-Yi

University of Technology

National Chung Cheng University

National Tsing Hua University

Thailand

Phuket Rajabhat University

Silpakorn University

Turkey

Anadolu University

Galatasaray University

Istanbul Aydın University

İzmir Bakırçay University

İzmir Katip Çelebi University

Izmir University of Economics

Marmara University

TED University

United Arab Emirates

Ajman University

United Arab Emirates University

Zayed University

Vietnam

British University Vietnam

RMIT University Vietnam

North America

Canada

Brock University

McGill University

Mount Royal University

The University of British Columbia University of Moncton

University of Montreal

University of Québec at Montréal University of Québec in Outaouais

University of Calgary

University of Lethbridge

University of Manitoba

Mexico

National Autonomous University of Mexico

Tecnológico de Monterrey

Universidad de las Américas Puebla

University of Monterrey

UTEL University

United States

Arizona State University

Aurora University

Bowie State University

California State University, Bakersfield

CUNY Lehman College

Eastern Michigan University

Prescott College

State University of New York Empire State University

Tidewater Community College

University of Arizona Global Campus

University of Arkansas

University of Connecticut

University of Florida

University of Illinois Chicago

University of Nebraska

University of North Texas

University of Southern Indiana

Waukesha County Technical College

Europe

Austria Mozarteum University Salzburg

Bulgaria

Prof. Dr. Assen Zlatarov University

Croatia University of Rijeka

Finland

University of Jyväskylä

France

École des Ponts Business School

Georgia

Caucasus University

Georgian National University SEU

International Black Sea University

Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

Germany

Philipps University of Marburg

TU Dortmund University

TU Dresden

Greece

Athena Research Center

International Hellenic University

Hungary

Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church University of Pécs

Italy

Istituto Marangoni

University of Florence University of L’Aquila

University of Modena and Reggio Emilia

University of Turin

Latvia

Daugavpils University

Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies Vidzeme University of Applied Sciences

Lithuania

Mykolas Romeris University

Vilnius Academy of Arts

Malta

The University of Malta

Poland

Kazimierz Wielki University

University of Łódź University of Silesia in Katowice

Portugal University of Aveiro

University of Évora

University of Lisbon

Romania

National Association of Public Librarians and Libraries

University of Bucharest

Russia

HSE University

Kazan Federal University

Serbia Institute of Social Sciences

Slovakia

Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra

Spain

Francisco de Vitoria University

Sweden

Södertörn University

United Kingdom

Coventry University

Cranfield University

Imperial College London

London Metropolitan University

Northumbria University

University College London

The University of Aberdeen

The University of Sheffield

University of Bedfordshire

University of Gloucestershire

University of Hertfordshire

University of Oxford

University of the Arts London