I’M MI

Fragility STRENGTH IN

When you’re making a magazine, there is very little room for “I”. Ego must step aside to embrace the “we” – the power of co-creation, the mess of merging ideas. We need to trust the process, navigating between chaos and order, in pursuit of collective learning, through which creativity and innovation can flourish.

Working within the space between chaos and order involves a transformative shift, which entails flexibility, curiosity towards change, and an attitude of empathy towards others – seeing and being seen. It is a process of moving through confusion towards the clarity of the final product, which reflects not only the collective wisdom of the students working on this magazine, but the whole community of the LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts (or ‘Muotsikka’ among friends).

The LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts is the home of changemakers, problem-finders, and problem-solvers. It is a hotbed of experimentation, a place for making mistakes and finding solutions. Working in this vein is fun, but never easy. It takes courage to open up to fragility. Embracing the messy and the incomplete is the first step to tearing down self-imposed constraints, shifting your perspective, and realising that there is no such thing as “ready”. That you will never stop evolving and growing. And that it is through co-creation and support from others that you will find your own voice, your individual creativity, and your inspiration. Collectively, these are the very things that enable designers to change the world.

SARA BENGTS

Senior Lecturer, Visual Communication Design

ISSUE 01

PUBLISHER

LAB University of Applied Sciences, Institute of Design and Fine Arts 2025

Mukkulankatu 19 15210 Lahti

Finland

www.lab.fi/muotoiluinstituutti @me_olemme_mi

ISSN: 2984-6463 print

PRINTED BY

Grano Oy, Helsinki

PAPERS

MultiOffset 250 g (FSC certified) G-print 130 g (PEFC certified)

Netta Aaltonen

Valtteri Ailio

Markus Aro

Oona Haakana

Iiris Hallikainen

Pinja Hautanen

Ria Heinola

Tiia Heliävirta

Helmi Jäntti

Niklas Javanainen

Valentine Kaikkonen

Nuutti Karjalainen

Vieno Karjalainen

Iina Kilpeläinen

Ida Kinnunen

Santeri Lehto

Mira Mäkelin

Melisa Rantala

Sami Rilla

Ella Ruuska

Pipsa Soimasuo

Ville Supponen

Katja Synenko

Valtteri Viitanen

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Viljami Annanolli

Elias Jimenez

Joona Möttö

Mark Sergeev

EDITORIAL STAFF

Sara Bengts

Teemu Helo

Silja Kudel

Tero Leponiemi

Tytti-Lotta Ojala

Marion Robinson

Petri Suni

Selina Vienola

Student Exchange –a Perspective-shifting Process

Digital Experience Design

Muted Voices – How to Make Them Heard Through Indigenous Design

Interior Architechture & Furniture Design

What's in MI Bag?

Sustainable Design Business Poison Green - New Approaches to Sustainable Colour

FOSTER YOUR CREATIVITY. ALLOW YOURSELF TO BE SEEN AND HEARD, EVEN IF YOU FEEL INCOMPLETE. CREATIVITY IS DRIVEN BY IMAGINATION AND INSPIRATION.

THE FOLLOWING DISCUSSION WITH TYTTI-LOTTA OJALA, DEAN OF THE INSTITUTE OF DESIGN AND FINE ARTS, TAKES UP THE THEME OF OUR 2025 PUBLICATION, FRAGILITY – A TOPIC THAT HOLDS IMMEDIATE RELEVANCE BOTH TO THE STUDENTS’ PRESENT STUDIES AND THEIR FUTURE PROFESSIONS.

Tytti-Lotta, you work as the Dean of the Institute of Design and Fine Arts at the LAB University of Applied Sciences. Your faculty offers many programmes devoted to various creative fields. What are the overall goals shared by every major?

At the Institute of Design and Fine Arts, we not only strive to educate students to become professionals in their chosen field, but our wider mission is to work towards improving the world in general. We hope our students will gradually evolve into broad-minded analytical thinkers and problem-solvers. Whatever the field, be it Product Design, Visual Communications Design, or Fine Arts, we embrace a future-forward mindset, radical innovation and an emphasis on visual creativity.

Sustainability seems to be high on your educational agenda. What skills and knowledge are needed to construct this kind of expertise, and how does your education support this?

Our faculty educates future problem-solvers, so we strive to offer our students solid technical skills and urge them to think analytically. We foreground the connection between making and thinking. Having a logical, curious mind is a valuable asset, but empathy skills are important too. The ability to empathise is invaluable for designers and artists.

Would you tell us more about the role of empathy in the work of designers and artists?

Especially for designers, empathic observation of the world and other people is crucial. To be empathic, you must also acknowledge your own sensitivity and fragility. Nurturing sensitivity and fragility is essential in a world that admires and prioritises efficiency and action. It is a unique resource, and I believe that creative people innately possess this ability and can develop it further in themselves.

The ability to put yourself in the position of the other is necessary for a human-centred and sustainable design approach, which is the key to future problem-solving. Today, the need for collaboration is more critical than ever before. But to work together, we need to trust each other and engage in dialogue. This is essential for solving the complex challenges of our time. That’s why we like to think of ourselves as educating professionals who ‘design life’, and not just ‘design for life’.

Finding your own voice is essential for any artist or designer. How does the Institute of Design and Fine Arts support this journey?

Whatever major the students choose, our education enables them to explore different approaches, fostering self-awareness and professional identity growth. In our faculty, we strive to plant seeds and nurture the growth of our students’ creative identities. During their studies, it is important for them to find the courage to experiment, be wild, and take risks without fearing failure. Their professional skills will continue maturing to their fullest after their studies.

Your goals certainly seem ambitious. What roles do you envisage your students playing in future society?

In addition to training future creative experts, we also try to influence society to provide designers and artists with opportunities to apply their expertise beyond just the narrow confines of the conventional field of ‘design’ or ‘arts’. Art and design professionals have a unique ability to understand people, examine existing systems, and create something new that does not even exist yet. Creating new value is a skill that is highly important for the future of our society. This understanding must be embraced in all new endeavours undertaken at the core of organisations and businesses. Internationally, creative folk and design directors have taken a seat on executive teams in all kinds of companies. People have finally understood that humanity is needed everywhere, in all kinds of operations and strategies. It is the foundation upon which wealth is built. Wherever the demand for efficiency still overshadows innovation, I hope we will see creativity being empowered soon; it is a vital condition for positive growth and the foundation of lasting happiness.

“FINE ARTS SHOULD BE MORE ACCESSIBLE TO WIDER AUDIENCES IN THE FUTURE.”

WHAT KINDS OF SKILLS ARE VITAL IN YOUR FIELD?

THE ABILITY TO CONSTANTLY ENVISION NEW OBJECTIVES FOR MYSELF HAS BEEN USEFUL. BEING ABLE TO EVALUATE MY OWN MOTIVATION, SELF-DIRECTION AND SELF-REFLECTION AFTER A PROJECT KEEPS ME MOVING FORWARD. YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO FIND YOURSELF APPROPRIATE CHALLENGES THAT HELP YOU GROW AS AN ARTIST.

Interview by VALTTERI AILIO Text by VALENTINE KAIKKONEN

At the LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts, research, development and innovation, or ‘RDI’ for short, plays a crucial role in shaping the future of design, art, and creative industries. Unlike traditional universities, LAB must secure external funding to drive its development projects, making RDI an essential part of our operations.

RDI at the Institute of Design and Fine Arts is deeply intertwined with the fields of design, visual arts, and creative industries. Our projects are often practice-based, incorporating real-world applications, regional impact, and international collaboration. Our goal is to enhance education, create new opportunities for students, and strengthen the connection between the academia and industry.

For students, RDI plays a crucial role in their studio work. Many of the projects undertaken in our studios originate from RDI initiatives, connecting students with companies and organisations that are looking for creative solutions. These collaborations provide hands-on experience, allowing students to experiment with innovative concepts and tackle real-world challenges while still in university. As RDI manager Minna Liski summarises:

“Studio work is where our students most clearly see RDI in action. Many of the cases they work on stem directly from our projects.”

The Institute of Design and Fine Arts participates in various RDI projects, each with a focus relevant to the institute’s expertise. Some projects explore sustainable design innovations through collaborations with industries to test new materials and production methods, such

as concrete applications in green urban spaces. Others develop international learning methods through Erasmus-funded initiatives aimed at enhancing creative and visual learning. Efforts are also under way to integrate art with tourism, connecting visual artists with regional tourism networks to help promote cultural heritage through creative interventions. One ongoing project aims to create novel platforms for art-tourism collaboration.

The theme of fragility is inherently present in our RDI work. Innovation requires experimentation, and with that comes the possibility of failure. Many RDI projects involve testing of new ideas, some of which may not succeed, but even failure is a valuable learning experience. At the Institute of Design and Fine Arts, this fragility is embraced as part of the creative process. By allowing room for risktaking, students and researchers can push boundaries and break exciting new ground.

Many of our projects focus on sustainability and resilience, addressing both societal and environmental fragilities. Whether designing a more sustainable future or supporting emerging artists in a rapidly changing industry, RDI seeks to have lasting impact while navigating the delicate balance between creativity and practical implementation.

RDI at the Institute of Design and Fine Arts is not just about research; it is also about shaping the future of design and art through collaboration, experimentation, and innovation. By integrating RDI into education and creative practice, the Institute of Design and Fine Arts continues to push the boundaries of design and artistic exploration.

INNOVATION IS KEY WHEN IT COMES TO CREATING NEW GOODS AND SERVICES OR IMPROVING EXISTING ONES.

Interview by PINJA HAUTANEN

Text by VILLE SUPPONEN

Whatever the project, innovation inherently requires out-of-the-box thinking and courage to try new ideas. But what happens when you take innovation to the next level with radical thinking? What is radical innovation and what role does it play at the LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts? According to RDI specialist Jani Kalasniemi:

“Incremental product development proceeds towards an envisaged result with a clear end goal in mind, whereas radical innovation explores a vast territory of options to discover a wholly new route to the goal.”

Unlike incremental product development, where you work on a single idea and improve on it step by step, radical innovation adopts an approach of thinking, questioning, concepting, running quick tests and creating discardable prototypes at lightning speed.

This approach enables you to chart a broad field of innovation until a completely new idea emerges from unexpected quarters. Then and only then do you start making incremental improvements… That’s radical innovation.

With radical innovation, you bring more value to your products and services, which not only increases their innovation potential but also fosters the advancement of the whole industry, potentially bringing your work to global markets.

The Laboratory of Radical Innovation hopes to bring more students on board, not just from the Institute of Design and Fine Arts, but from all fields of study, to work together on new and exciting projects that benefit from fresh perspectives and innovative angles.

“TIME GIVES MEANING TO THE PROCESS.”

NOWADAYS, PHOTOGRAPHY AND PHOTOS ARE AN INESCAPABLE PART OF OUR DAILY LIVES, POPPING UP EVERYWHERE. I FEEL THAT OUR WORK AS PHOTOGRAPHERS IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN EVER, BUT THE GENERAL QUALITY OF IMAGES IS DECLINING. WE DO MORE THAN JUST CAPTURE AN IMAGE. THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHY, WE TELL STORIES THAT EXTEND BEYOND THE IMAGE ITSELF.

ALVA

Interior Architecture and Furniture Design

Emma came up with the idea for this project by exploring the compatibility between vases and various floral arrangements. Having often found vases to be the wrong shape for certain bouquets, she addressed this issue by creating a novel vase that can be modified to accommodate a wide range of floral arrangements, consisting of two parts that can function either together or separately. The appearance of the vase can be altered by inverting the top, making it easy to pack into a small space.

Wearable Design

Final thesis

Studies show that approximately one billion umbrellas are discarded yearly. Weighing between 300 and 500 grams each, this produces up to 500,000 tonnes of waste. The high volume of discarded umbrellas is largely due to the popularity of inexpensive models, the difficulty of repairing them, and a general lack of awareness about how to recycle umbrellas and the environmental

impact of disposing of them.

One potential solution is to repurpose the materials instead of recycling them. To tackle this challenge, Miia embarked on a thesis project seeking innovative ways of reusing old umbrellas as wearable products.

The collection was created with a zero-waste approach by draping materials over a mannequin. Inspired by the geometrical design of umbrellas,

Miia incorporated umbrella canopy fabric into outfits, while transforming repurposed metal components into form-fitting structures and wearable accessories. The thesis explores alternative forms of weather protection, which influenced the structural innovations in Miia’s designs. Rainscape combines futuristic aesthetics with functional design and innovative materials.

NOORA HUOLMAN

Fine Arts

Final Thesis

In Poistoja , Noora used an etching needle to remove segments of the paper surface. She explored the movement involved in removing material, the resulting patterns, and the relationship between the artist’s conscious actions and the traces left behind in both paper-based and processual work. Through this installation, Noora foregrounds the broader field of printmaking.

Interior Architecture and Furniture Design

Sukkula is a coat stand created as part of an in-depth workshop assignment focusing on usability and industrial manufacturability. Anu recognised early in the design process that the coat stand needed to fulfil multiple purposes while remaining sufficiently compact to fit into smaller living spaces.

The metal coat stand comprises a seat made from birch plywood. The seat is hinged, allowing it to be freely positioned. The stand can be disassembled into four separate parts and is simple to reassemble using a hex key.

Graphic Design

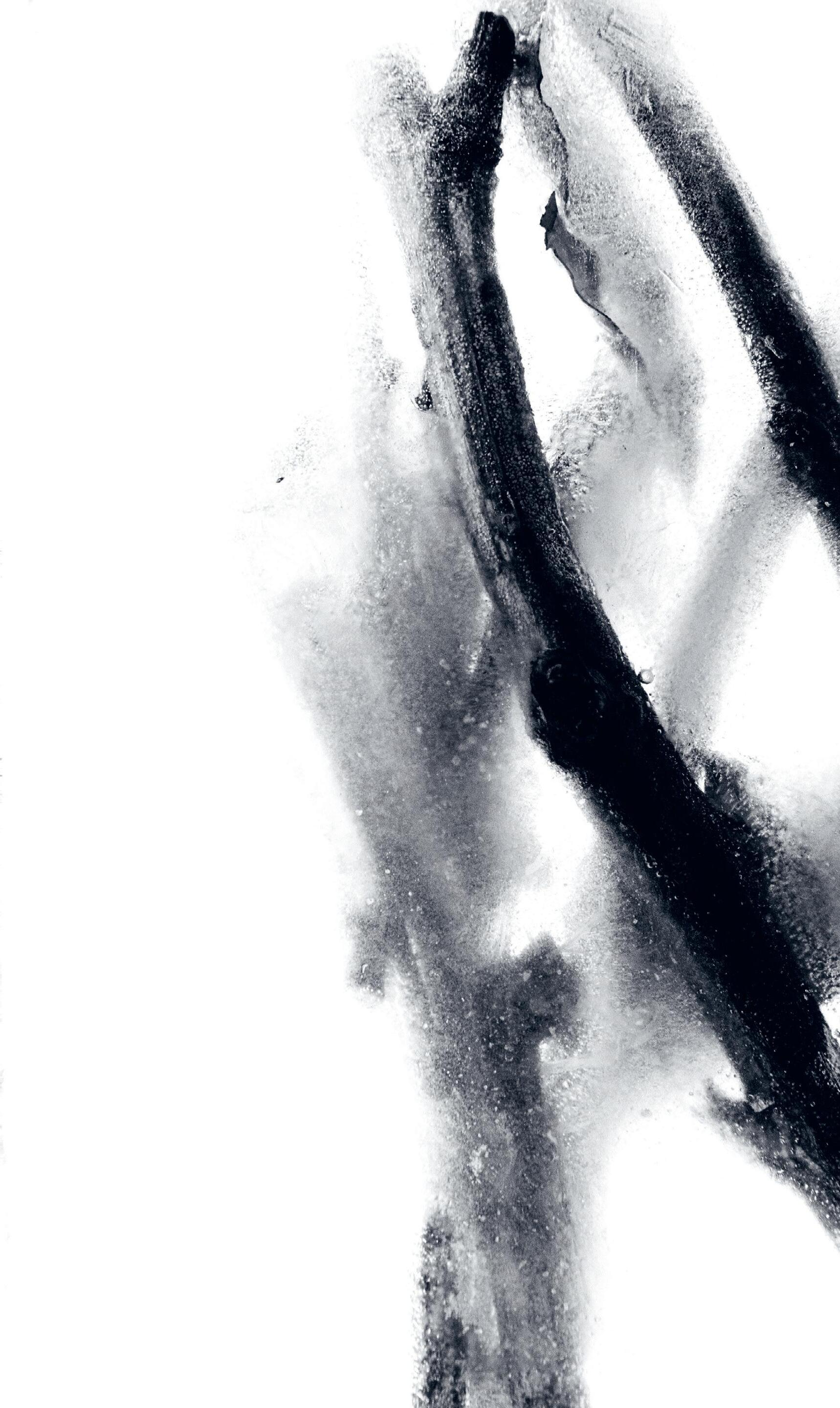

Mustat juuret is a collection of short prose by Mikko Granroth. Juhana contributed several photographs to be used as illustrations for the stories. Since Mikko was already familiar with Juhana's previous work, he gave Juhana the freedom to create illustrations based on keywords and adjectives describing the content.

COMMUNITY

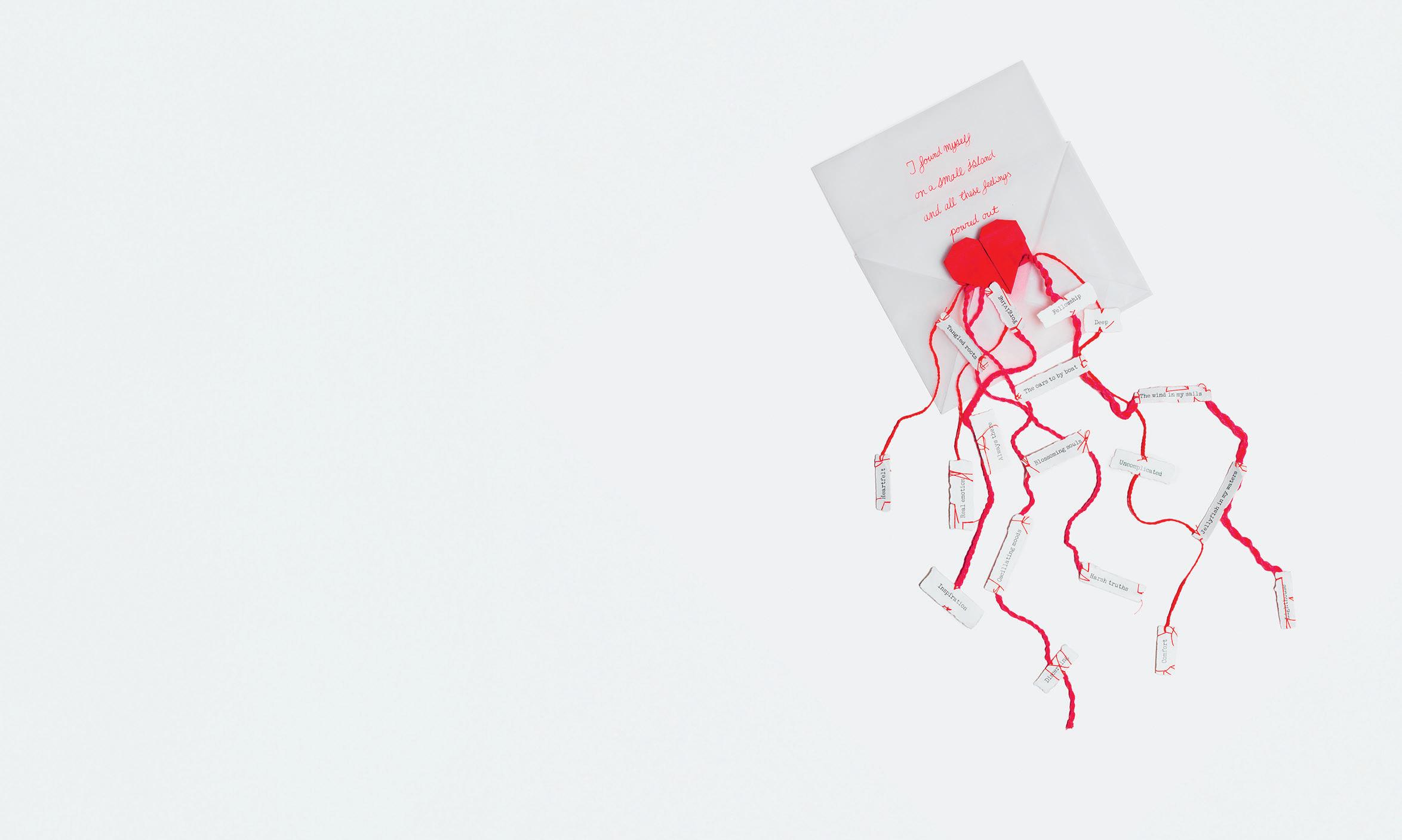

Graphic Design

At the beginning of September 2024, Rebekka spent several days on the island of Utö in the outer archipelago. During her stay, the significance of community became evident in day-to-day life on the island. The island’s residents are uniquely and powerfully affected by the forces of nature, compelling them to rely on one another more closely than mainlanders. The experience made Rebekka reflect on her own community and its meaning in her life, inspiring the letter installation aptly named Community

Sustainable Design Business

Hanieh captured the reference photo for For a Dream in Talesh County in the Iranian Province of Gilan. The painting depicts cut-down trees, signalling the end of their lives. The artist finds the image distressing, reminding her of the many lives that have been lost. The forest in the background represents her utopia.

Many people sacrifice their lives to save others or fight for the dream of a better world and freedom and prosperity for all. (Referencing Mahsa Amini Revolution and #womanlifefreedom in Iran)

SAMI BAHAOUI

Interior Architecture and Furniture Design

Plays on perspective lie at the core of Sami’s Kavela designs, which change form and appearance depending on the viewer’s angle. While Sami was initially sketching the stool/side table, he was fascinated by shapes that expand in various directions and the relationship of these shapes to small attachment points. He drew inspiration from cliffs and bluffs, particularly a boulder balancing on a smaller rock known as ‘Kummakivi’ (Strange Rock) located in Ruokolahti. The design harnesses the centre of gravity to create an optical illusion.

YATZY BOTANICAL WONDERLAND COOKIE EDITION

Packaging and Brand Design

The design of the packaging concept for Yatzy Botanical Wonderland began with thorough research. Samira and her team in the packaging studio course explored a variety of paperbased materials and analysed market trends related to cookies.

Using the insights gained from their research, they developed a prototype for the packaging and refined it until they perfected the final design. The completed packaging is sturdy, made from 400-gram virgin paper and is entirely glue-free. It aims

to foster connections through shared play. In addition to holding cookies, dice, and pencils in hidden compartments, the packaging contains collectable botanical-themed Yatzy cards and a Japanese bound rulebook to enhance the overall experience.

no. 14

BUILDING NO. 14 IN TELAKKARANTA, HELSINKI

Interior Architecture and Furniture Design

Final Thesis

The goal of Suvi’s thesis was to explore how sustainable spatial planning can be exercised with sensitivity and respect for the history and original architecture of old buildings. Since construction is a major polluter and resource consumer, Suvi aimed to identify effective tools and practical methods to minimise environmental impact by maximising the reuse of old buildings and materials.

Suvi developed a conceptual plan for an old industrial building in Helsinki’s Telakkaranta district, designing a café that also serves as an exhibition space. Her plan emphasises the reuse of existing materials, incorporating items such as the building’s original bricks and metal pipes into the café’s furniture. Suvi conducted thorough research on this concept, compiling a guide for implementing sustainable interior design practices.

STUDENT EXCHANGE IS A LEARNING EXPERIENCE THAT BRINGS OUT BOTH STRENGTH AND FRAGILITY. BEING EXPOSED TO NEW PEOPLE AND PRACTICES FORCES THE STUDENT TO CONFRONT THEIR VULNERABILITY, BUT ULTIMATELY REWARDS THEM WITH HIGHS AND LOWS TO REMEMBER FOR THE REST OF THEIR LIFE.

EXCHANGE STUDENTS HARRI HANHISUANTO (MEDIA DESIGN) AND EVELIEN DENNEMAN, (COMMUNICATION & MULTIMEDIA DESIGN) SHARE THEIR THOUGHTS ON THEIR TIME ABROAD.

The decision to apply for student exchange may be spurred by the desire to see the world, to experience new study approaches, or merely to take a break from one’s current university or country, be it however briefly. “I applied mainly because I wanted to explore and learn about new cultures,” says Harri. Evelien applied for the programme because she was suffering from study fatigue in the Netherlands. “I had wanted to go to northern Europe for a very long time. The Netherlands is a small country and there isn’t much nature. I heard from friends that Finland is a nice place.” Both Evelien and Harri suddenly found themselves transplanted in a cultural context very different from their respective homelands.

“I compare it to repotting a plant. You take the plant out, expose its bare roots, and the plant has no choice but to adjust. That’s how it felt. You lay down your roots and start growing again.”

Evelien Denneman

Most exchange applicants initially feel nervous or scared. Being alone in an unfamiliar place far from one’s safe, familiar surroundings and friends can elicit feelings of discomfort – yet this is exactly what forces the student to start interacting with their new environment. Evelien and Harri believe that putting yourself in that scary position is beneficial, as it forces you out of your bubble and makes you realise there is so much more out there. That vulnerability ultimately strengthens you in many ways.

Evelien applied to study at the LAB University of Applied Sciences in Lahti, which is surrounded by forests and natural beauty. Harri in turn ended up at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, where he discovered a giant campus area and a tight-knit student apartment community. Both Harri and Evelien noticed many differences in their new culture and study environment compared to their former universities. Harri was impressed by the lectures in Canberra, which introduced a new subject every week, rounded out by tutorials diving deeper into the lecture topics, and workshops for practical application. “The campus area was huge, with dozens of student houses, cafes and restaurants. It takes around 30 minutes to walk from end of the campus to the other.”

Evelien noticed a dramatic difference in Lahti’s academic culture. “At the beginning of my studies, I wanted to get

all the obligatory research out of the way as soon as possible, but my teammates said it was unnecessary. In the Netherlands, we have to write four- or five-page reports about what we plan to do and why, which I never liked. In Lahti, we didn’t have to write so much, which made me happy. The teachers wanted to give us more time to work on our actual projects. Studying is more chill in Finland. Frankly speaking, one reason I wanted a break from my university was because I wanted a less academically rigid approach.”

Making new friends and connecting with the community was certainly not an issue, assure both students. Harri found his first friends on his apartment floor, and Evelien thanks her groupwork-focused courses for introducing her to new friends. Neither had any trouble socialising, as there were always plenty of friendly faces inviting them to join in parties, karaoke, board games and forest walks.

“I believe my worldview is expanding daily. I now reflect on things from a greater variety of perspectives than I did before.”

Harri Hanhisuanto

From the anxiety of applying to the heartfelt moments of making new friends, the two exchange students have found themselves transformed as creatives. Their views on their dream careers have now also taken a clearer shape. In Finland, Evelien realised she has no interest in “a high expectations job” or becoming a big-name designer. Instead, she wants to enjoy her life to the fullest by creating art and spending time in nature, with her future job taking a back seat to personal fulfilment. For Harri, the diverse classes he took at his Australian exchange school sparked a deeper interest in SFX and VFX work, and he even explored composing through a movie composing course.

In the end, it comes as no surprise that both Harri and Evelien describe their student exchange experience as one of the best decisions they ever made. Both wholeheartedly recommend it to all their peers.

SHIFT YOUR PERSPECTIVE. EVERYTHING IS ALWAYS IN FLUX, INCLUDING OURSELVES. ALLOW YOURSELF TO GROW AND EVOLVE THROUGH NEW EXPERIENCES AND IDEAS.

“DESIGN

ISN’T JUST ABOUT CREATING BEAUTIFUL OBJECTS, BUT ALSO ABOUT MAKING EVERYDAY LIFE EASIER.”

HOW DOES PRODUCT DESIGN FEEL, LOOK, SOUND AND SMELL?

THIS FIELD IS BOTH INSPIRING AND CHALLENGING. IT LOOKS DIVERSE, SINCE IT ENCOMPASSES A WIDE SPECTRUM OF DIFFERENT INDUSTRIES AND PROCESSES. IT SOUNDS LIKE LEARNING THROUGH CONVERSATIONS WITH PEERS. IT SMELLS LIKE NEW MATERIALS AND PROTOTYPES. THE DESIGN PROCESS IS EXCITING AND BRIMMING WITH NEW IDEAS.

Text by the Finnish Human Technology Network

htTechnological development is reshaping society at an unprecedented pace, offering immense opportunities while also posing critical challenges, such as environmental strain, growing complexity, and threats to humanity-centred values. In a society ubiquitously dominated by IoT, AI, the platform economy, and social media, technology is never neutral – it reflects the priorities, values, and biases of its creators. Now is the time to address problems such as distraction and fragmentation and consider how technology can be harnessed to drive sustainable, equitable, and humanity-centred futures.

By embedding the principles of technological humanism, Finland can lead global markets through ethical innovation. Pilot projects, enterprise engagement, networked collaboration, new ecosystems, and targeted education can create solutions that align business growth with sustainability and fairness. This approach redefines competitive advantage while fostering technologies that respect transparency, inclusivity, and ecological balance – creating a blueprint for meaningful progress in a complex world.

Technology embodies the conscious and unconscious choices, values, norms, political and financial interests, and biases of its developers and owners about the world and its desired state. Because technology permeates all areas of life and affects us all, its development and use must be subject to open, transparent, and democratic influence.

Because technology is created by humans, we have the power to shape its direction. Technology was originally developed to ease our lives and expand our capabilities, but human interaction with technology is undergoing a significant transformation, and scholars have been turning their attention from human-centred design to examining exactly how technology is impacting humanity.

Sustainable and regenerative design addresses the root causes of global challenges, earning the respect of ethically conscious customers and stakeholders. Companies that align their growth strategies with long-term societal well-being contribute to a better world and secure their relevance and success in an evolving marketplace. By embracing these principles, businesses can position themselves as ethical leaders. In a competitive environment, prioritising human values, sustainability, and outstanding experiences is a compelling market advantage.

Respecting privacy is a critical differentiator. Customers reward companies that protect their data, explain its usage transparently, and prioritise security. By embedding privacy as a core principle, businesses safeguard trust and position themselves as leaders in ethical innovation. 9. PRIVACY AS A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT

People must come first in technological solutions, and the rights and interests of individuals must come before corporations. Trust and loyalty are built through transparent systems and respectful practices, such as avoiding manipulative dark patterns. Technological humanism commits to the ongoing search for ways of sustaining human dignity in the lives of individuals across a diverse array of social, economic, political and cultural contexts. 3.

Inclusive technology ensures access for all, particularly underserved groups such as ageing populations. Communities are strengthened through the prioritisation of collective and social solutions over isolating, “atomised” approaches. Inclusivity is not just a moral imperative; it is also a market advantage, as organisations that embrace diversity unlock broader customer bases and foster innovation. This inclusive approach also positions businesses as leaders in fairness and representation.

Sustainability is a strategic imperative. Customers favour brands that prioritise long-term environmental and societal well-being over short-term gains. By accepting the complexity of challenges and creating regenerative solutions, organisations can lead markets while earning the loyalty of ethically conscious consumers.

Trust is the currency of modern business, and transparency is its foundation. Open systems that clearly communicate data usage and decision-making processes set organisations apart by proactively addressing risks and making the invisible visible, enabling companies to strengthen user confidence and cultivate a competitive advantage in a trust-driven economy. 7. TRANSPARENCY AND TRUST

Empowering users with autonomy is a hallmark of exceptional design. Systems that reduce cognitive overload enable sound decision-making to build customer loyalty. In an era where control and clarity are valued more than ever, businesses prioritising user agency distinguish themselves as customer-centric innovators. 10. HUMAN CONTROL AND AGENCY

8. ETHICS AT EVERY STEP

Ethical frameworks are no longer optional – they are key to sustainable success. Companies that exercise caution and address root causes of potential harm can gain a competitive edge in a world where consumers increasingly value responsible practices. Ethical products and services foster trust, reduce reputational risks, and align with growing demands for accountability.

1. Thou shalt not place metrics above values.

2. Thou shalt not add complexity where simplicity sufficeth.

3. Thou shalt not hide risks beneath the rug.

4. Thou shalt not burden users with needless choices.

5. Thou shalt not bind growth to irresponsibility.

6. Thou shalt not isolate when thou canst connect.

7. Thou shalt not ignore imbalances of power.

8. Thou shalt not treat symptoms without addressing root causes.

9. Thou shalt not underestimate potential harms.

10. Thou shalt not forsake the Earth.

The Finnish Human Technology Network is a collective of researchers and practitioners promoting humanity-centred values in technological development. The manifesto proposes values to be fostered in research, development, and education across different disciplines.

Markus Ahola, Chief Specialist

LAB University of Applied Sciences

Institute of Design and Fine Arts

Harri Heikkilä, Principal Lecturer

LAB University of Applied Sciences

Institute of Design and Fine Arts

Sariseelia Sore, Principal Lecturer

LAB University of Applied Sciences

Faculty of Technology

Sami Kauppinen, Senior Specialist

Laurea University of Applied Sciences

Master School

Satu Luojus, Principal Lecturer

Laurea University of Applied Sciences

Master School

Anna Salmi, Senior Lecturer

Laurea University of Applied Sciences

Master School

Antti Pirhonen, Associate Professor

Finnish Institute for Educational Research University of Jyväskylä

Text by MIKKO ILLI

Illustration by VALENTINE KAIKKONEN

WHEN CONFRONTED WITH CRITICISM, DESIGNERS AND RESEARCHERS ARE LIABLE TO FACE COMPLEX FEELINGS OF DISAPPOINTMENT AND SHAME. IN HIS ARTICLE, MIKKO ILLI EXPLORES HOW FACE-THREATENING SITUATIONS CAN OPEN UP NEW PERSPECTIVES AND OFFER VALUABLE EXPERIENCES FOR SELF-IMPROVEMENT.

We designers and researchers invest our heart, soul, and creativity into producing outcomes that we consider important and impact the world. When these outcomes meet with resistance and harsh criticism from their intended audience, we feel disappointment and face-threatening shame. During those moments, our professional identity [1], which is a stable part of our communication within the work community, becomes diffusely located and situated in interactions. [5, 8] This article explores sociologist Erving Goffman’s concept of ‘face’ in the context of dealing with criticism. Goffman [2] identified that we struggle to preserve face when mutual considerations become misaligned and interactions begin to resemble a game, match, or negotiation.

When we experience the threat of losing face, we feel shame and separation from the social group to which we want to belong. We may respond to this situation negatively, by reacting aggressively or avoiding contact with the potential source of conflict to prevent feeling shamed again. Shame may also elicit self-criticism, potentially leading to perfectionism or maladaptive behaviours such as alcohol or drug abuse. These reactions represent dysfunctional mechanisms in coping with face-threatening situations. However, acceptance of shame in critical situations can open up opportunities for change , persuasion , and perspectival transformation by eventually turning the threat into something productive [see also 7]. In what follows, I will present personal experiences collected from work encounters in which my team or I have faced criticism, followed by a discussion of their significance.

Firstly, I will focus on a case study of positive change impelled by an experienced face threat. The case involved a research collaboration with a lift truck producer. Two R&D managers and I wanted to test the usage of designing visuals in sales work. Although we believed in our approach, and involved a third-party design consultancy to design a prototype of a brochure,

“THE TERM ‘ FACE’ MAY BE DEFINED AS THE POSITIVE SOCIAL VALUE A PERSON EFFECTIVELY CLAIMS FOR HER/HIMSELF BY THE LINE OTHERS ASSUME

S/HE HAS TAKEN DURING A PARTICULAR CONTACT.” GOFFMAN (1967)

our idea was turned down harshly. During a workshop, the sales manager expressed surprisingly negative reactions, throwing the papers in the air and exclaiming, “We are not going to waste time on things like this”. One member of the sales team proceeded to call this manager “aggressive Gabriella”. After the outburst, the workshop concluded abruptly. At the time, I felt disappointed and disconnected from the sales team, but later I was able to see the productive side of the outcome. We proved that analytical observation of visual strategies was more important in the sale of industrial machines than designing tangible solutions at this stage.

A second positive outcome of facing criticism is the opportunity to engage in persuasion , a strategy often employed by salespeople. Being persuasive involves the successful communication of knowledge, power, and emotions. The salesperson in this case study faced a complaint from a customer, who criticised the company’s technicians for “fixing problems that do not exist”. The customer also voiced a demand for “more accurate reporting,” adding that he lacked the technical knowledge to understand the specifics of lift truck manufacturing. The salesperson responded with sensitivity, harnessing knowledge as a tool of persuasion. [3] Firstly, he downplayed his own technical skills: “Same here, you need to be a pro to understand this stuff.” The salesperson then presented a visual report showing a machine-specific abstract bar chart of maintenance costs, explaining how maintenance costs are impacted by the age of each machine. The customer was placated and agreed to the salesperson’s proposals, even though he was not presented the requested detailed maintenance report. The salesperson used his persuasive skills to shift the customer’s perspective from a negative emotional state and tense power play situation towards a positive flow of emotions and sharing of useful knowledge concerning machine ageing. [4]

Face threats can also facilitate perspectival transformation . The last case study involved a

peer-review process at a scientific conference, where we faced personal criticism from an editor. In their review report, this pseudonymous editor accused us of misconduct, using the words “ethically unacceptable”. The review was released at around 11.00 pm Finnish time, and in my panic, I called my thesis advisor without considering the late hour. We had one week to redress the claim in a single A4 rejoinder. We responded by presenting clear evidence refuting any ethical misconduct, and we received a positive response from all other reviewers except the same editor, who was still not satisfied, adding further harsh comments, such as “I do not trust the authors,” while at least admitting to having limited expertise in research ethics. The editor used the blind review process to unjustly attack us. [6] I felt emotionally distressed, lost sleep, and needed support to recover from the experience. As time passed, however, I started to recognise that the editor was inexpe-

rienced and unprofessional, and faced challenges with the review process. Ever since, I have always remembered this case, and when I myself am reviewing articles, I always try to be polite to the authors and respect their efforts.

I hope the above stories will help readers to see that face threats can yield positive outcomes. We tend to think that creative workers should be resilient in the face of all kinds of criticism. In reality, we should take the opposite approach and share and discuss our experiences of criticism more openly to learn to cope with them and transform them into productive outcomes. We can, for instance, internally visualise positive and negative responses and outcomes in face-threatening situations, which can help us to identify, share, and internalise more successful facework practices. See page 78 for references

“DON’T THINK IN TERMS OF STUDENT-TEACHER ROLES, JUST FOCUS ON YOUR LEARNING JOURNEY!”

WHAT MIGHT DIGITAL EXPERIENCE DESIGN LOOK LIKE IN FIVE TO TEN YEARS FROM NOW, AND WHERE DO YOU SEE YOURSELF IN THE FUTURE?

VISUALITY SHOULD BE SEEN MORE AS A FUNCTIONAL TOOL RATHER THAN AS AESTHETIC DECORATION. I HOPE THAT THIS FIELD WILL BECOME MORE STABLE AND WIDELY ESTABLISHED, OFFERING GOOD PROSPECTS FOR EMPLOYMENT. I PERSONALLY HOPE TO FIND MYSELF WORKING ON PROJECTS THAT ALIGN WITH MY VALUES. I WANT TO BE ABLE TO MAKE PEOPLE’S EVERYDAY LIVES EASIER.

DESIGN IS OFTEN GEARED TOWARDS INNOVATION, YET IT IS EQUALLY IMPORTANT TO FOSTER ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES BY RESPECTFULLY DRAWING ON EXISTING TRADITION. THE

We are living in harsh, chaotic times, and many groups across the world are struggling to make their voices heard. Bad design and exploitative development can exclude many people and living beings, while good design can proactively improve their lives. Here, it is important to consider issues such as intersectionality, which has been at the forefront of academic debate in recent years. Intersectionality promotes an understanding of identity as something that is shaped through the interaction of multiple social dimensions (e.g. ‘race’/ethnicity, indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, disability, immigration, religion). In short, this means that people’s lives are multidimensional and that their reality is shaped by multiple social dynamics working in unison.

This article is devoted to discussing human-oriented, indigenous and regenerative design. I first encountered the theme of indigenous design when I attended the World Design Summit 2017 in Montreal, where indigenous design was the main theme of the conference. Later, I was also introduced to the Regenesis Group, which has developed a framework for processes of sustainable regenerative practice. The framework states that regenerative design entails an understanding of the potential and inherent ability of a place and its cohabitors to co-create an evolving reciprocity. At the heart of regenerative design is the need to make people feel a sense of belonging. Thus, the regenerative approach foregrounds the life of a place and its interactions with other beings. This kind of thinking is inherently characteristic of indigenous cultures, which show a capacity to comprehend and relate to com-

plex entities. This capacity is something that the rest of us might call “living in balance with all living beings”, or the ability to coexist reciprocally with the planet.

The regenerative framework methodology is one way of bridging the gap between indigenous (circular) and colonial (square) practitioners. During my visit to Montreal, I heard about and saw many examples of indigenous design. Discussions published in the book Our Voices –Indigeneity and Architecture (2018) highlight the ability of architects and designers to learn, listen and create empathy for the culture they are designing for. One of the authors, Luugigyoo Patrick Steward, is a Canadian architect who gave a speech at the 2017 summit. He opened his talk in his native language, registering an awareness that he was a stranger in another tribe’s land, in the manner of traditional indigenous greetings. Through this gesture, he wanted to show how human behaviour can be modified if we genuinely respect different groups of people.

Steward emphasised that anything that is designed in the name of indigenous culture should be planned by and with members of that culture. The same applies to all human-oriented design. Designers must be able to design together and show empathy for the people they are designing for. Regenerative design extends this approach to the whole planet, encompassing all living beings in the design process.

The following text is from the author’s notes from the Montreal World Design Summit 2017 Indigenous Design exhibition:

“The most impressive part of the exhibition for me was the conceptual intervention Speech Silencing Arms / Place d’armes by EVOQ architects and Native Montreal. Their intervention was built around a statue of Sir Maisonneuve in Montreal’s city hall square. Maisonneuve, a French officer and the founder of Montreal, is a key figure in Canada’s history of conquest. He arrived uninvited in Montreal, which at the time was inhabited by eleven indigenous communities. In the conceptual intervention, a circle of talking sticks was placed around the conqueror’s statue, whereby the indigenous peoples (including the twelfth “newcomer nations” of Montréal) welcomed Maisonneuve on their own terms. For indigenous peoples, making themselves visible in Montreal also means rediscovering their own voice. The 'talking stick' is a North American indigenous instrument of democracy giving the person carrying it permission to address the group. In the conceptual intervention, each nation’s talking stick was adorned with distinctive symbols, while an audio soundtrack told the story of their people.”

I was inspired by Canadian perspectives on indigenous design and began looking more closely at Sámi design and indigenous practices in the North. Essi Ranttila (2021) describes the tenets of Sámi design in her master’s thesis:

“Sámi design is inventive, holistic, environmentally conscious, ecological, abundant, ethical, timeless, finished and functional. In addition, it embraces a communicative approach to survival, sensitivity, symbolism and the sense of community that is integral to Sámi culture. Sámi design represents a divergent track from Finnish design because of its different starting points and unique traditions.”

“ DESIGNERS MUST BE ABLE TO DESIGN TOGETHER AND SHOW EMPATHY FOR THE PEOPLE THEY ARE DESIGNING FOR.

”

See page 78 for references

“THE DESIGN PROCESS IS CREATIVE, BUT RATIONAL. IT TAKES ME ON A JOURNEY OF DISCOVERY INTO MY SOUL AND SUBCONSCIOUS.”

DOES FRAGILITY HAVE A PLACE IN YOUR FIELD? HOW DOES IT MANIFEST ITSELF?

DEFINITELY! FRAGILITY IS THE ABILITY PICK UP SUBTLE DIFFERENCES LIKE NUANCES OF MATERIAL OR FORM, THE MOVEMENT OF LIGHT, OR THE SURROUNDING SOUNDSCAPE. IT IS A SKILL THAT ENABLES US TO UNDERSTAND EACH OTHER AND OURSELVES, TO INTERPRET THE UNSAID, AND TO HARNESS OUR FLEETING INSPIRATIONS TO GUIDE OUR CREATIVE PROCESS.

WHAT DO STUDENTS TYPICALLY CARRY AROUND ON CAMPUS? WE ASKED OUR STUDENTS TO SHOW THEIR BELONGINGS, EVEN THE EMBARRASING ONES.

Sachin Shrestha

“FINDING THE SUPPORT AND GUIDANCE YOU NEED BUILDS CONFIDENCE AND COMPETENCE.”

WHAT IS THE MOST IMPORTANT COURSE IN YOUR FIELD AND WHY?

OUT OF ALL THE IMPORTANT COURSES, I THINK STUDIO COURSES BRING THE MOST TO THE TABLE. THEY BRING OUT YOUR CREATIVITY, AND YOU GET TO WORK WITH CRUCIAL SOFTWARE ON LARGE-SCALE PROJECTS. ADDITIONALLY, BEING SURROUNDED BY PEOPLE WITH A SIMILAR INTEREST IN SUSTAINABILITY FACILITATES THE FINDING OF NEW PERSPECTIVES AND POSSIBILITIES FOR DESIGN.

Text by VILLE HUHTANEN

Illustration by VIENO KARJALAINEN

Colour lies at the very core of all aesthetic experience. It therefore possesses enormous power to affect the value of artefacts, products and services. But colour is a topic that has taken on toxic connotations in the wake of the severe risks to human and planetary health posed by colouration practices. The sustainability crisis necessitates a radical shift in thinking, and weak signals indicating the inevitability of systemic change are already inescapable. This article discusses the harmful impacts of colouration and new approaches to sustainable dyeing.

Colour is not just an aesthetic enhancement; it plays a crucial role in creating value, constructing identity, and even wielding power. Historically, the “politics of colour” have influenced everything from social hierarchies to cultural identities. Colour carries distinct meanings in diverse cultural contexts. Despite variations in these symbolic meanings – which incidentally have lesser impact on human emotion than colour’s perceived lightness and saturation – chromaticity in itself remains a powerful and universal tool for communication and value creation. Colour is a meta-discipline, according to the findings of the Colour Literacy Project, an initiative curating, producing and publishing high-quality colour knowledge based on novel colour research.[1]

The emotional impact of colour is a subject that is also undergoing a shift in contemporary discourse. Traditional approaches like the hue paradigm, which emphasises fixed associations between hues and emotions, are giving way to less language-dependent and multidimensional viewpoints on colour’s emotional impact. The way colour is used to create emotional resonance and perceived value is being explored increasingly through new scientific and artistic lenses.

Colour researcher Ellen Divers states that contemporary research on emotional responses to colour has yielded undeniable evidence pointing to the need for a shift towards the lightness-chroma paradigm. In other words, the emotional effect that colour has on us is linked to colour interactions and their perceived lightness and saturation, instead of more traditional, language-dependent approaches concentrating on differences between hues such as red and green. Indeed, according to many contem-

porary researchers, colour’s lightness and chromaticity (i.e. colourfulness or saturation) elicit almost unambiguous and uniform emotional responses, especially when observed in the context of several interacting hues. In summary, in analysing colour’s impact on our emotional responses, we should think first of how light, dark, vivid or muted it is – the hue itself holds secondary significance.[2]

Recent research on colour’s emotional impact along with emerging solidifying knowledge of colour’s role in consumer behaviour may be potent tools in supporting a shift to a more sustainable colour paradigm. When we know more about colour, we can produce and market products with longer lifespans, resulting in less discarded products and less wastage.

The environmental impact of colour production is significant. Major sustainability concerns include microplastic pollution from synthetic pigments and coatings together with toxic and unethical dyeing processes, which contribute to environmental degradation and human health risks, dependency on fossil-based raw materials for pigments and finishes, and excessive wastage, particularly in fast fashion and industrial applications.

A paradigm shift is crucial, replacing a linear approach, where colour materials are produced, used, and discarded, with a circular model that prioritises reuse, longevity, and ecological responsibility. This requires not only technological advancements but also a redefinition of colour’s aesthetic and cultural value.

01. Ecological sustainability and waste reduction in textile colouring

Reducing waste and pollution is crucial for sustainable design. Strategies for doing so include sustainable dyeing processes. Waterless dyeing technologies, natural and bio-based dyes, digital dyeing and dope-dyeing techniques are reducing the environmental and health loads caused by the human desire for chromatic stimulation. Leading

technologies in waterless dyeing include supercritical CO₂ dyeing pioneered by DyeCoo. Plasma and ultrasonic waves are also used to dye textiles without water. Digital dyeing utilises a variety of printing and spraying techniques to print desired colours in precise locations. Pigment can be integrated in the printing process also in the 3D printing of textiles. In dope-dyeing, colour is added to the polymer solution before the fibres are formed, which reduces water consumption and wastage and also increases the colour’s longevity. The sustainability of the dyeing process is further enhanced by closed-loop systems and efficient recycling. These novel sustainable practices in the manufacture of coloured textiles are rounded by wastewater recovery and reuse together with advanced methods of separating and reusing coloured materials, such as robotic sorting of coloured recycled fibres.

02. Consumer behaviour and awareness –buying cleaner colour

The environmental footprint of colour is also influenced by the way it is consumed. Recent shifts in consumer behaviour indicate an increasing awareness of sustainability. Hannele Kauppinen-Räisänen, a lecturer in consumer research at Helsinki University, argues that present consumer behaviour indicates a shift in the definition of “luxury”. Today’s concept of luxury is less status-related and more experiential by nature. [3]

The value of a product or service is furthermore a personal issue, being defined by whether it feels meaningful or valuable in one’s personal life. Value can also be constructed through the product’s narrative, for instance through its handcrafted quality, material authenticity, embedded story, or other aspects conveying uniqueness. Ethics, responsibility and longevity are simultaneously gaining importance.

The flourishing flea market business is a significant signal of changing consumer behaviour. Vintage branding and curating have evolved rapidly in recent years, indicating a significant shift in both behavioural and value paradigms.

Sustainable consumption can be fostered by encouraging consumers to care for and repair coloured products instead of discarding them. Customers should be informed openly and transparently about the manufacturing processes involved in colouring products, much in the same way as nutritional information is visible on food labels. [4], [5] Business could also be increasingly developed around repair and upcycling, possibly supported by governmental funding. Other strategies could include promoting longevity in colour design, focusing on timeless palettes rather than trend-driven cycles, and supporting brands that implement sustainable transparency in their colour supply chains.

03. Industry and regulatory action

Systemic change requires collaboration between industries, researchers, and policymakers. The ongoing multinational BioColour project, for instance, explores sustainable colouration methods that reduce environmental impact while maintaining aesthetic and functional qualities. As part of this project, a wide palette of natural colourants has been developed and tested for industrial purposes. The project has also involved R&D on sustainable colouring methods, as well as consumer and market research around the sustainability of colour. The BioColour project was awarded the Finnish Colour Association’s 2025 Iiris Prize for its exemplary work in the field of colour research. On a national or global level, industry-wide regulations and ethical frameworks can push for more responsible colour production and consumption. Political guidance holds potent tools in its arsenal for actuating change.

04. Reimagining colour aesthetics

– new notions of patina

Sustainability should not be seen as a constraint but as an opportunity. Sustainability-driven design requires a rethink of materiality and exploration of new ways to integrate colour into design processes. The brutalist movement and the conceptual design company Droog have embraced the idea of enhanced and honest materiality in archi-

tecture and design, which often means treating colour as an experience provided by the raw material itself. Assimilation of such aesthetic norms in consumer culture could result in a significant reduction in the need for colouring. According to a paper published by Durrani and Niinimäki in 2022, internal mental associations are major factors influencing colour consumption choices, serving as “lenses” through which consumers view colours. Visual preference-based thought patterns can be influenced through art and innovation, because art can suggest and distil experimental ideas and propose new aesthetics, as the history of visual culture has repeatedly testified.[6]

Emerging movements like bio-brutalism are updating traditional brutalist design thinking by incorporating organic, sustainable materials, by favouring semi-controlled or other strategically post-humanistic manufacturing processes, and by integrating time-based natural processes like fading or decomposition as a central part of the creative process. Bio-brutalism also prioritises locally sourced materials, such as side streams from agricultural practices or other found organic material. For his project at the Royal Academy of Arts, Will Eliot designed a stool by letting mealworms eat cavities into sugar-water-treated polystyrene, after which the resultant worm-sculpted form was cast and 3D-printed. Anna Tsiganchuk in turn made stool prototypes out of locally sourced, seasonally available organic materials such as leaves and twigs, giving a focal role to processes of withering, decay and the semi-random changing of colour. Using a twig fastening system, the designer retained full control of the rough form and structural decisions, while leaving open other design choices such as the material and how it changes over time.

Similar ideas are common in time- and space-related art practices. Related movements like eco-art, land art and regenerative art treat material from a post-humanistic perspective. Eco-artist Agnes Denes planted a wheatfield in downtown Manhattan as a gesture questioning the value of one of the city’s most expensive pieces of land measured in dollars. In his land art piece The Lightning Field (1977), Walter di Marias installed 400 stainless-steel poles in a grid array measuring one mile by one kilometre with pointed tips reaching towards the sky in New

Mexico.[7] The lightning-attracting installation can be interpreted as a commentary on nature’s mightiness and human smallness, inviting us to observe forces of nature as powerful agents outside our ordinary sphere of life. The philosophy of new materialism challenges the role of material in a comparable way, suggesting that material is itself an active agent, and highlighting the interconnectedness of inanimate artefacts and matter with human and non-human organisms. Centred on the ethics of care, new materialism nurtures the planetary health paradigm, foregrounding the role of other-than-humans such as bees, solar wind, algae and the Earth’s core polarity in processes of transformation. While being partly fictional and speculative by nature, new materialism is capable of transforming human-centred, anthropocentric narratives about the status of humans and other-than-humans in the cosmos by means of storytelling.[8] If we cannot imagine change, it is unlikely to occur.

The natural environment, time-based processes and local sourcing are indeed focal elements in contemporary art, combined with a hint of punk attitude. It is conceivable that strong art paradigms may rapidly spread throughout society, as has happened before repeatedly in history.

Bio-brutalism is a hyper-marginal design concept, but it represents core ideas that are distinctly similar to those recognised in consumer behaviour research. Organic vegetables and their ‘scabby’ visual appearance have already been accepted as an aesthetic standard. Perhaps we will soon see a similar sustainable aesthetic become a dominant trend in consumer products.

A sustainable approach to colour necessitates a fundamental shift in both production and perception. Imagination and creative practices such as art and design seem to play a more influential role than is usually acknowledged in the colour sustainability leap. From ecological responsibility to cultural meaning, the redefinition of colour in design and industry marks a powerful step toward a more sustainable future. By embracing innovative dyeing technologies, promoting responsible consumer practices, and fostering systemic collaboration, we can ensure that colour continues to be a meaningful yet sustainable part of our world. See page 78 for references

“WHEN YOU LOOK AT YOUR WORK THROUGH SOMEONE ELSE’S EYES, YOU SEE THE GOOD AND BAD ALIKE.”

Aino Kataja

WHAT INSIGHTS HAVE YOU GAINED DURING YOUR STUDIES?

THROUGH MY STUDIES, I HAVE FOUND MY IDENTITY AS A DESIGNER, AND THIS HAS ALSO IMPACTED MY PERSONAL LIFE. MY VALUES HAVE SOLIDIFIED, AND I HAVE FOUND MY OWN PATH IN DESIGN. MY NEWFOUND SELF-CONFIDENCE HAS ALSO HELPED ME TO FIND A TARGET AUDIENCE WHOSE VALUES ALIGN WITH MINE.

IN HER THESIS, WEARABLE DESIGN STUDENT EMILIA OKSANEN OFFERS FRESH INSIGHTS INTO WEARABLE DESIGN THAT CAN SUPPORT SENSORY-SENSITIVE INDIVIDUALS BY PROVIDING TAILORED, ERGONOMIC, AND AESTHETICALLY PLEASING SOLUTIONS.

Text & Photos by EMILIA OKSANEN

Throughout my life, I have experienced heightened responses to sensory stimuli in my environment. As a child, bright lights, loud sounds and strong scents affected my energy levels and my ability to focus. Over the years, my sensory hypersensitivity has lessened to a degree, and I have found solutions to ease the resultant discomfort. Finding comfortable clothing has been especially beneficial. I am very specific about the way textiles feel against my skin. If a seam is misplaced or the material is uncomfortable, clothing can feel like it is literally burning my skin. Many other sensory-sensitive individuals describe their responses to clothing in similar terms.

Our brains are constantly processing all the information we gather from our surroundings. When the brain fails to keep up with this rapid flood of stimuli, it results in what is called ‘sensory regulation difficulty’, or sensory hypersensitivity, to use the more common term. Sensory regulation difficulty can affect a person’s actions and behaviour, sometimes posing challenges in the form of stress and fluctuating energy levels. [5] Sensory hypersensitivity is not a medically diagnosed condition but more of an individual attribute that is commonly linked with ADHD and the autism spectrum. Sensory hypersensi-

tivity occurs in up to 70% of people on the spectrum, and it occurs in around 30-50% of people with ADHD, but it can also manifest on its own. According to scientific estimates, approximately 5-10% of the Finnish population have issues with sensory hypersensitivity. [5]

Clothing choices reflect the relationship between the individual and their environment. More subconscious factors such as metabolism, body temperature and heart rate can also have an impact on our choices. Structural solutions, thermal insulation, breathability, fabric thickness and weight are influential factors in choosing a piece of clothing. Comfortability is, in fact, the collective sum of all these factors. [3] When an item of clothing is comfortable, the wearer should ideally not even notice the garment they are wearing or its weight. To a person with sensory hypersensitivity, comfortability is linked to the crucial ability to focus. [6] I examined this issue in my thesis by conducting a survey in which respondents were asked to describe their sensations. Typical responses included the following: “I am constantly adjusting seams, belts and collars” and “If my clothing irritates me in any way, I become restless, my focus drops, and I can only think about the moment when I finally get to remove the uncomfortable item.”

Kay et al. (2024) have compiled a list of factors that should be considered in sensitive design:

▪ Careful attention should be paid to structural solutions, like seams, their location, tags and choice of fabric.

▪ Soft and smooth materials are often experienced as more comfortable.

▪ The garment should support both functional and design requirements.

▪ The clothing should allow good mobility.

▪ Used textiles are durable, long-lasting and withstand wear and tear.

▪ Affordability and availability must also be factored in.

Tactile comfort in product design must be based on an understanding of the feeling of fabric on skin and the mechanisms of tactility. [2] Quoting Niinimäki and Kos kinen (2011), Järvinen observes that people grow attached to clothing in three ways: through aesthetic properties, social situations and positive multi-sensory user experience.

Beyond visuality, the beauty of an item of clothing is additionally based on tactile sensations, scent and kinetic sensations, such as material feel, comfortability and the garment’s weight against the body. A comfortable piece interacts with its user, creating connections with tactile memory and our personal experiences and history. [2]

Objective monitoring of tactile experiences would be imperative for the future advancement of wearable design for sensory-sensitive individuals. Designers easily base their idea of tactile comfort on their own associations and experiences, but every sensory-sensitive person is an individual with their own unique responses. What works for one might cause major discomfort for another.

Based on the data collected for my thesis, I composed a guide offering tips for designing clothing for sensory-sensitive target groups. I discovered certain commonalities among sensory-sensitive individuals, for example in terms of the materials they perceived as most comfortable. Designers can utilise this and other collected data to enhance the sensitivity of wearable design.

Sensory perspectives should be considered in all design solutions,[1] not only those targeted at sensory-sensitive target groups, for whom comfort-related issues can assume greater importance than other design priorities. Despite this fact, sensory-sensitive design is still largely in its infancy, and there is enormous potential for further development of this segment. Innovations in seam design, tactile comfort, structural solutions and weighted clothes are but a few examples of possible solutions. Finally, aesthetic considerations are commonly assigned lesser priority in the case of people with special needs, but people with sensory sensitivity are naturally also interested in dressing in visually pleasing clothes. Rather than precluding one another, aesthetics and sensory comfort should be regarded as common aspirations in all sustainable design.

See page 79 for references

of the décollage artists, using errors within systems as a visual device. [7]

Text by ILMARI POHJOLAINEN

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze saw the world as consisting of two intertwined planes: the actual, where events unfold in the present, and the virtual, a plane of potential that coexists with the actual. By creating the right conditions, the unforeseen and novel events of the virtual plane can be conjured up and made actual. [5]

My thesis explores how graphic designers can create these conditions for new events to emerge through fragmentation. Citing semiotics and examples from art history, I demonstrate that fragmentation is a powerful visual tool that encompasses both the physical and interpretative reframing of design.

Fragmenting a piece transforms it from a state of clarity to vagueness, sometimes even discomfort. However, as the Cubists understood in the early 20th century, fragmentation does not lead to the destruction and disappearance of the work but rather to the creation of new interpretations. [4]

When things are broken apart, they often reveal the underlying system and its logic. The French décollage artists of the 1950s employed fragmentation by tearing down political posters in the streets at night and using the torn fragments to compose new works that reflected the unstable political atmosphere of the time. [1] Contemporary glitch artists have followed in the footsteps

Working in a similar vein, graphic designer David Carson uses the fragmentation of typography and layout primarily to emphasise expressiveness. Carson has argued that by challenging legibility, the design becomes more engaging and read able. His approach revealed that the reader’s impulse to decode is more deeply ingrained than anticipated. [4]

Beyond its visual impact, fragmentation can serve as a metaphor for human decay. The Caretaker’s six-hour-long album Everywhere at the End of Time (2019) portrays the progression of Alzheimer’s disease by gradually fragmenting 1920s ballroom music until it becomes barely recognisable. [2]

Fragmentation does not carry solely negative connotations, however. William Basinski’s composition The Disintegration Loops (2002) fragments idyllic 1980s compositions through repetition [3]. As the melody dissolves into silence, it evokes a melancholic yet restorative beauty. As critic Mark Richardson (2012) concluded his review of the album:

“But then as it started to break apart and silence took over, I started to become aware of what was around me. I could hear the engines, the rattle of the tracks, and the voices of people in the subway car… And then as the last crackle faded and the music was no more, I took in my surroundings and looked around at the faces, and I was right there with everybody, and we were alive.”

See page 79 for references

JUHO MAURINEN

GRADUATED: 2020

STUDIED: MEDIA DESIGN

FAVOURITE SONG: MY CHILDREN by PROTOMARTYS

FAVOURITE COLOR: MUSTARD YELLOW

ANIMAL GUIDE: MONKEY

FAVOURITE CHARACTER AS A CHILD: BIKER MICE FROM MARS, TURBO

THREE THINGS THAT ARE VERY "YOU": SAUNA, BICYCLES, SPEED

Text by TIIA HELIÄVIRTA, KATJA SYNENKO

Photos by ELIAS JIMENEZ

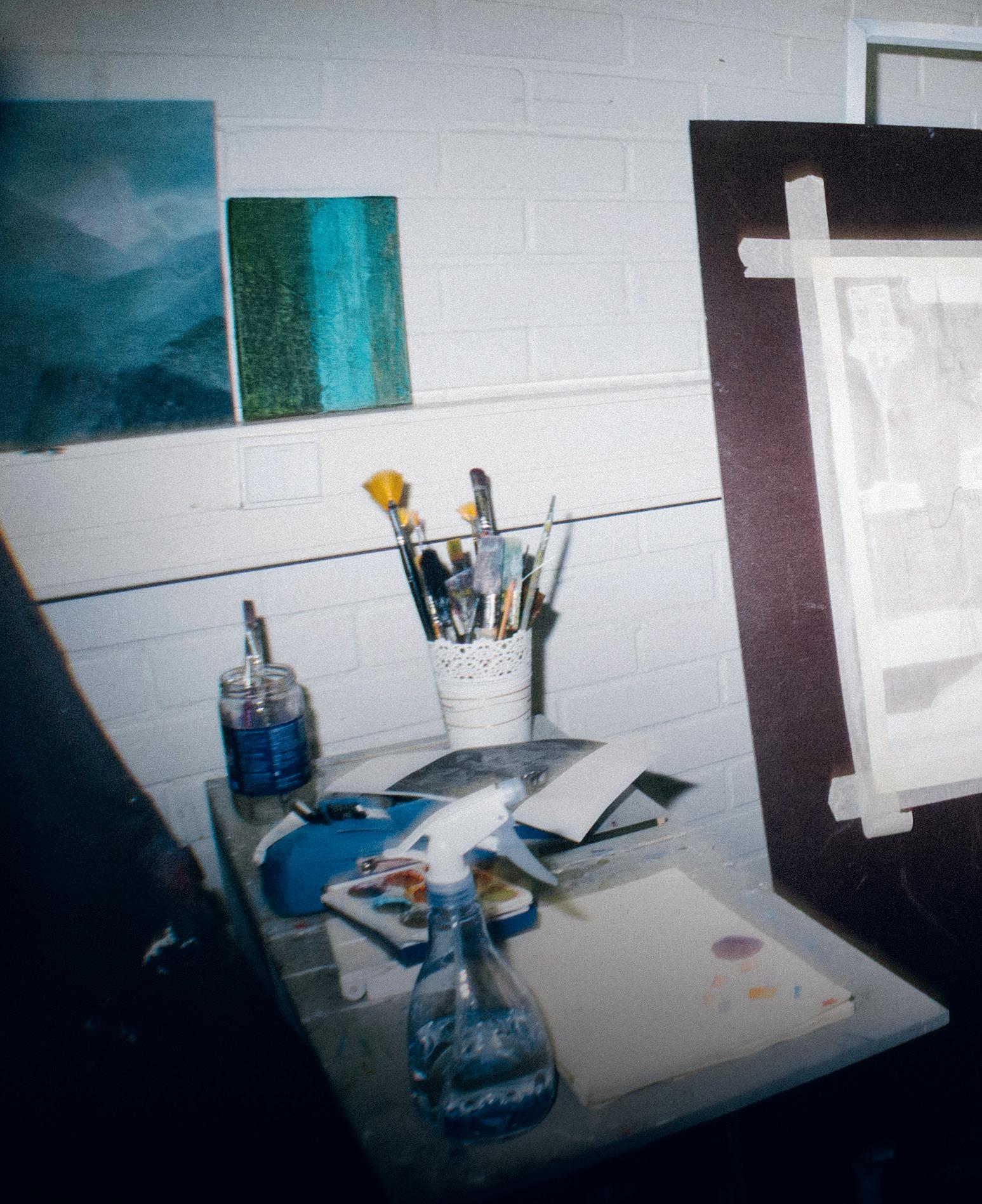

I work professionally in the fields of animation, illustration and graphic design, but considering how much time I spend on it, music is also my work.

The LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts was the first place where I truly felt part of a creative community. I graduated in 2020 and I still have very dear friends in my life from that time. At the moment, I’m working on a collaborative project with about 17 people, and 70% of them are Muotsikka graduates.

Our studies covered a wide range of stuff, including sound and moving image, which was exactly what I needed. Everything I've learned about design, I learned at Muotsikka. Obviously, animation was what stuck with me. We also collaborated on many projects, for instance we formed our own theatre group and made a musical about the Muotsikka campus move.

Muotsikka relocated to the new campus in 2018. The move was a big thing. It provoked a backlash, as big changes always do. I don’t want to be that guy who moans for the good old days, but I’d be lying if I said that I didn’t have a soft spot for the old campus. Now that I’m working as a teacher at Muotsikka, it’s good to see how the students have taken over the new campus space and made it their own.

The work I’m proudest of is the animated short film and music video MUSCLE HEARTS, which won me my first awards at animation festivals. The piece was a study in anti-cynical storytelling and comedy, which has been my passion for the past few years.

I don’t have a “professional” me. For better or for worse, I always try to be unapologetically myself in my work. I am comfortable with fragility, and can be transparent about my weaknesses.

How does FRAGILITY show in your work?

For the last few years, my work has almost exclusively dealt with sincere and sensitive themes, such as friendship and self-acceptance. Especially when I’m working with music, I have no filter. What interests me about fragility is its paradoxical nature of being openly weak which in itself feels strong. My work suggests a sort of punk aesthetic, which to me means sincerity. I don’t try to be edgy, even if my pieces have a rough, punky look.

EVERYTHING I'VE LEARNED ABOUT DESIGN, I LEARNED AT MUOTSIKKA.

GRADUATED: 2022

STUDIED: INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE AND FURNITURE DESIGN

FAVOURITE SONG: PLANET EARTH II SUITE by HANS ZIMMER, JACOB SHEA & JASHA KLEBE

FAVOURITE COLOUR: GREEN

STAR SIGN: ARIES

ANIMAL GUIDE: HELMET CASSOWARY

THREE THINGS THAT ARE VERY "YOU": VERY ARIES, PLANT-HOLIC, PARADISE

I NEVER TRULY LET GO OF MUOTSIKKA. I’D LOVE TO GO ON LIVING AND BREATHING THAT ATMOSPHERE FOREVER.

How does FRAGILITY show in your work?

Fragility is present in the materials I use. Working with glass requires a lot of precision and care. Fragility also presents itself in the huge uncertainty that always accompanies the design process. Even when you are proud of the outcome, the process leading up to it is always fraught with vulnerabilities – and nervous breakdowns!

My studies at the LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts really got out of hand when I realised you can do as many courses as you like. I wanted to get as much as I could out of my studies. The best thing about Muotsikka is the people. I arrived on campus early in the morning and went home late at night, just because I had so much fun there. But of course we also worked damned hard too.

In my opinion, the difference between Muotsikka and other schools is the hands-on approach. It’s all about playing and experimenting – that’s the essence of Muotsikka. In my former life, I worked in customer service, so when I got accepted and started my studies, the question of “who am I?” hit me hard. You could say that my identity and self-expression were built from scratch from that moment onwards.

Renovating our home has been my favourite recent project. It’s been a nightmare, but also quite an accomplishment. And, of course, I’m also very proud of my recent thesis project: the redesign of a mobile bird cleaning unit used as part of oil spill response equipment. The redesign was commissioned by WWF Finland.

Before applying to study at Muotsikka, I was a carpenter. I decided to study interior and furniture design because I wanted to create my own designs rather than just execute them on behalf of other designers.

Muotsikka fuelled the kind of creative experimentation that is very useful to me in my current position at Vaarnii. At Muotsikka, you learn by trying things out instead of only studying theory. Even during our first courses, we made real, fully finished furniture. The knowledge I gained has been a great asset in my later professional life.

My first design job was a real jackpot. Through the school, I received an invitation for an interview and was hired by the Vaarnii furniture design company. I ended up doing a lot of work there. I worked alongside my studies, and after graduating in 2024, I stayed on at Vaarnii. Combining my studies and work moulded me into the designer I am today.

GRADUATED: 2024

STUDIED: INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE AND FURNITURE DESIGN

FAVOURITE COLOUR: RED

STAR SIGN: LIBRA

FAVOURITE CHARACTER AS A CHILD: ALL THE CARE BEARS

ANIMAL GUIDE: SLOTH

Any advice for current students?

Be brave and ask for help. I personally had such a fierce drive to learn that I boldly always asked for help and instructions. The younger students tended to just sit and wait, and nothing ended up happening. Experiment and play! At a place like Muotsikka, the facilities are incredible, and you should make the most of them. You can really create anything there.

THREE THINGS THAT ARE VERY "YOU": VERY LIBRA, CONSIDERATE, SAVONIAN

THE KNOWLEDGE I GAINED HAS BEEN A GREAT ASSET IN MY LATER PROFESSIONAL LIFE.

GRADUATED: 2005

PROFESSION: VISUAL ARTIST, ILLUSTRATOR

STUDIED: GRAPHIC DESIGN

FAVOURITE SONG: SUMMER ON A SOLITARY BEACH by FRANCO BATTIATO

FAVOURITE COLOUR: GREEN

STAR SIGN: CANCER

ANIMAL GUIDE: OTTER-SNAIL-RABBIT HYBRID

I am an illustrator and visual artist living and working in Turku. I also create book covers and other graphic design. My approach is multidisciplinary, but drawing is at the heart of everything I do. I graduated from the LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts, or Muotsikka, in 2005.

I remember design school as one of the best times of my life. It was easy to make friends with my fellow classmates. We quickly became a close-knit group, maybe because we all moved to Lahti from all over Finland, and everyone was pretty much in the same boat, so we relied on each other. Some of my classmates remain my closest friends. We worked hard, but we also had a lot of fun together!

Even though graphic design has never been my main vocation, the skills have been very useful. I have been able to find employment both as an illustrator and as a graphic designer. Now that I am working primarily as a visual artist, I can design my own exhibition posters and marketing materials.

I love immersing myself in my work and kind of losing myself. For me, this relates especially to working with my hands. I don’t get the same feeling when I’m working on a computer; for me, it comes only from drawing. It feels a bit like blurring the boundaries between yourself and your work and losing track of time. It’s very enjoyable.

Any advice for current students?

You shouldn’t pressure yourself to be a “ready-made package” right at the beginning of your career. If you want to be an illustrator, it takes time to find your style. Your style may also change over time. Sometimes you need to unlearn certain things if you notice that they don’t suit you. It all takes time. Revelations only come through years of work

I am an artist originally from Oulu, now working and living in Tokyo, Japan. I mainly work in the medium of watercolour; the themes of my works sail between fantasy and mundane observations.

I studied graphic design at the LAB Institute of Design and Fine Arts, but I would describe myself more as an artist. Muotsikka absolutely changed me as a person, the school was a great setting for trying out new things and making exactly the kind of art I wanted to. I produced a lot of my own merchandise during my Muotsikka days. You should always dream big. Having dreams is what motivates me to continue working hard. After graduating, I was able to do my own thing and work as an artist. Moving to Japan was a big step for me, and now I am at a point where I am ready for my next big dream.

I have always wanted to live abroad, and that’s what led me to Japan. Speaking the language is often vital if you want to study or work in Japan, but there are many countries where you only need English to work as a graphic designer.

SOMETIMES YOU NEED TO UNLEARN CERTAIN THINGS IF AT SOME POINT YOU NOTICE THAT THEY DON’T SUIT YOU.

Big hugs to everyone studying at Muotsikka! If there was a saying I especially remember from my Muotsikka days, it would be: “Done is better than perfect!”

Höijer &

“I FEEL LIKE I STUMBLED INTO THE FIELD OF DESIGN BY ACCIDENT, BUT I’M GLAD I DID!”

WHAT FASCINATES YOU ABOUT THIS FIELD AND WHY DID YOU CHOOSE IT?

VISUALITY IS EVERYTHING! AS VISUAL COMMUNICATION DESIGNERS, WE GET TO MAKE END PRODUCTS THAT REFLECT OUR PERSONAL STRENGTHS AND INTERESTS. WORKING WITH LIKEMINDED PEOPLE IN A SAFE ENVIRONMENT IS A GREAT WAY TO IMPROVE YOUR PRESENTATION SKILLS AND YOUR ABILITY TO LEARN FROM CONSTRUCTIVE CRITICISM.

Last October, I sat at the Spirit of Paimio Conference listening to Beatriz Colomina’s speech on the interaction between architecture and microbes. As a masterpiece of modern architecture, Aino and Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium (built in 1933) set the perfect stage for the eye-opening speech given by Princeton University’s Professor of the History of Architecture.

Tuberculosis posed a constant threat of death in the 19th and early 20th century, leading the way to modern architecture. Sanatorium care became the dominant treatment for the disease, influencing not only sanatorium architecture itself, but also spurring a whole new architectural trend emphasising large windows, simplicity, clean lines and avoidance of superfluous ornamentation.

Colomina writes in her article The Bacterial Clients of Modern Architecture (2020):

“[Modern] buildings were formed by what they excluded rather than what they included. Physical, mental, moral, social and economic health were dependent on the apparent cleanliness of buildings, as conveyed by routine aesthetic descriptions like ‘clean lines’ and ‘pure form’.”

Smooth white surfaces, expansive glass, and sun terraces were primarily instruments of health. The buildings were understood to be cleansing machines that must themselves be constantly cleansed.

“Modernizing architecture was first and foremost a medical procedure to evict millions of tiny threatening organisms.”