The hobarT and William SmiTh CollegeS and Union College ParTnerShiP for global edUCaTion

a

The hobarT and William SmiTh CollegeS and Union College ParTnerShiP for global edUCaTion

a

The Aleph: a journal of global perspectives

Volume XVIII, 2025

Kristen Welsh, Editor

Hannah Mathews, Editor and Artistic Director

Tom D’Agostino, Founding Editor

Elizabeth Palumbo, Assistant Editor

ISSN 1937-0474

Stories in The Aleph are set in Gentium, designed by Victor Gaultney and adopted by SIL International, an organization working to document thousands of dying ethnic languages, many of which are written in modified Latin scripts. Most digital fonts do not include these extended alphabets and therefore millions of people are shut out of the publishing community. Gentium is an attempt to meet this challenge. The name is Latin for belonging to the nations.

© 2025 Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Union College Partnership for Global Education

Kristen Welsh, Executive Director

Trinity Hall, 3rd Floor

Hobart and William Smith Colleges Geneva, New York 14456 (315) 781-3307

Cover Photo Credits:

Front Cover: Playing Soccer, Makhanda, South Africa [Marissa Mastracco], Piha Beach, New Zealand [Luke Viggiani]

Inside Front Cover: Flamenco Performance in the Plaza de España, Seville, Spain [Isabel Goldblatt-Hamilton]

Inside Back Cover: Ice Cream Stop, Penghu, Taiwan [Annabel Ramsay]

Back Cover: Pragser Wildsee, South Tyrol, Italy [Bradley Kutchukian], Women Talking at Shibazakura no Oka (Pink Moss Hill) in Front of Mount Buko, Saitama, Japan [Shraddha Datta]

The first edition of The Aleph: a journal of global perspectives was published in 2002 as part of the Partnership for Global Education initiative between Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Union College. Since its inception, the journal has served to reflect the wealth of international experience among students at our respective institutions, and we are pleased to have extended this opportunity to students across the New York Six Liberal Arts Consortium.

The journal takes its name from the 1945 short story “The Aleph” by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. In the story, the narrator (a writer) comes upon “a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance” in which “without admixture or confusion, all the places of the world, seen from every angle, coexist.” Through this encounter with the mystical Aleph, he is able to see all things from all perspectives – yet he despairs of the daunting task of trying to convey the enormity of this experience to his readers.

Our students face much the same challenge when they return from abroad: after crossing borders and cultures, navigating societies different from their own in which they are exposed to new values and perspectives, how can they make sense of it all? How can they adequately convey the significance of the experience to those who did not share it?

The Aleph: a journal of global perspectives was created to address this dilemma. It provides a space for reflection, analysis, and dialogue that benefits contributors and readers alike. The pieces, both written and visual, offer insight into what captivates, challenges, and inspires our students – and through these words and images we learn about the people and places they encounter, we see how they change along the way, and we are exposed to “all the places of the world, seen from every angle.”

ENGAGEMENT (p. 6)

I. Techno Culture in Berlin (Nailah Lloyd-Jones) II. Formula 1 Culture & The Zandvoort Experience (Tessa Baker) III. Nama-Stay in Italy (Emma VanGorder) IV. Celebrating Fastnacht Along the Upper Rhine (Grace Wilson)

CONNECTIONS (p. 24)

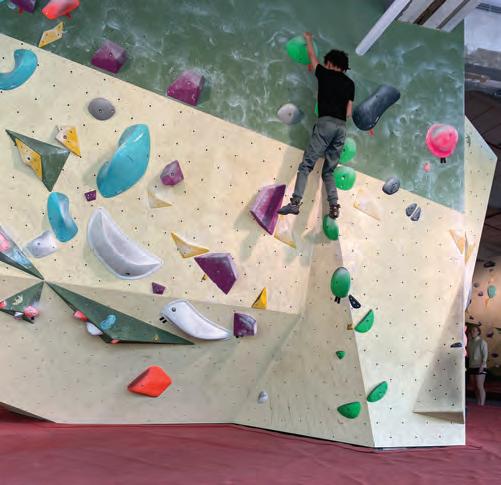

I. Meeting My Aussie Neighbors (Courtney Swenson) II. A War with a Modern-Day Vampire (Hannah Angelico) III. Demystifying Dutch Bluntness Through Fitness Culture (Tulsi Perun)

CROSSINGS (p. 40)

I. My Home Away from Home (Mia Tetrault) II. Normalizing Naked (Sydney Herbruck) III. Riverside Tales: A Year on London’s Bridges (Tinashe Manguwa) IV. Berlin to Bonn: Moving Around in Deutschland (Ali Muzaffar)

FROM MY SKETCHBOOK I (p. 65) (Ali Muzaffar)

LESSONS (p. 68)

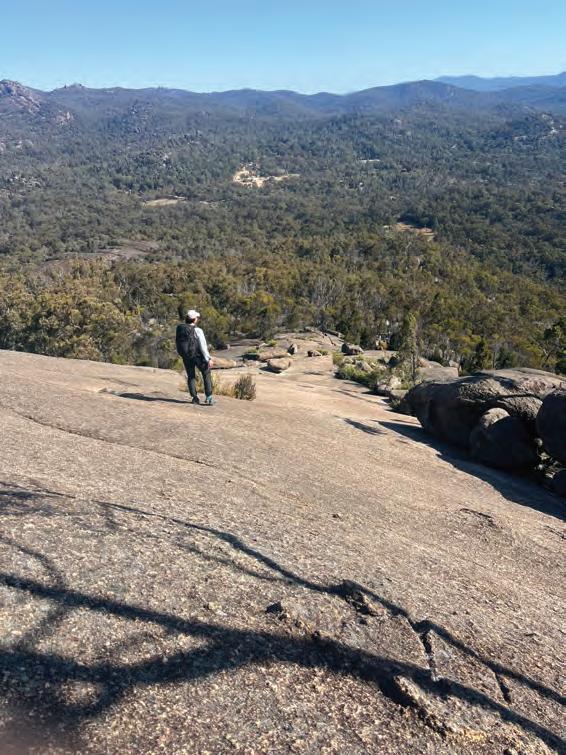

I. Lessons in Leisure (Brooke Prochniak) II. Approaching Meals with a New Perspective (Samantha Goldburg) III. Trust the Granite (May Joy) IV. Las Papas Arrugadas (Wylie Jacobs & Isabella De Nes) V. “Hey Going?”: A Reflection Crafted by Australia (Danielle Krenzer)

REFLECTIONS (p. 92)

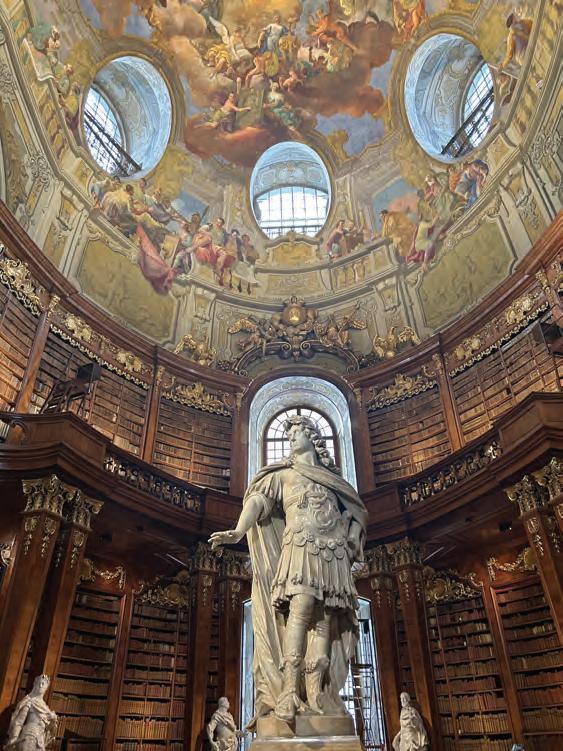

I. Thoughts from Tbilisi (Giorgi Bekauri) II. Exploring Europe Through Libraries: A Journey of Books, Architecture, and Culture (Kylie Rowland) III. Learning About Myself in Japan (Richard Garner) IV. Spontaneity (Alexandria Lacoste) V. Last Day vs. First Day in Leipzig (Hannah Green)

VERSE & VISION (p. 122)

I. Weeping for the Sea (Ilana Lehmann) II. A Journey Through Aotearoa (Anjalee Wanduragala) III. copenhagen, city of DIS (Andrew Pilet) IV. Inis Mór (Elizabeth Palumbo) V. Sakura Flowers (Shraddha Datta) VI. Stations (Maeve Reiter) VII. Seeing a Whale Shark (Isabel Goldblatt-Hamilton)

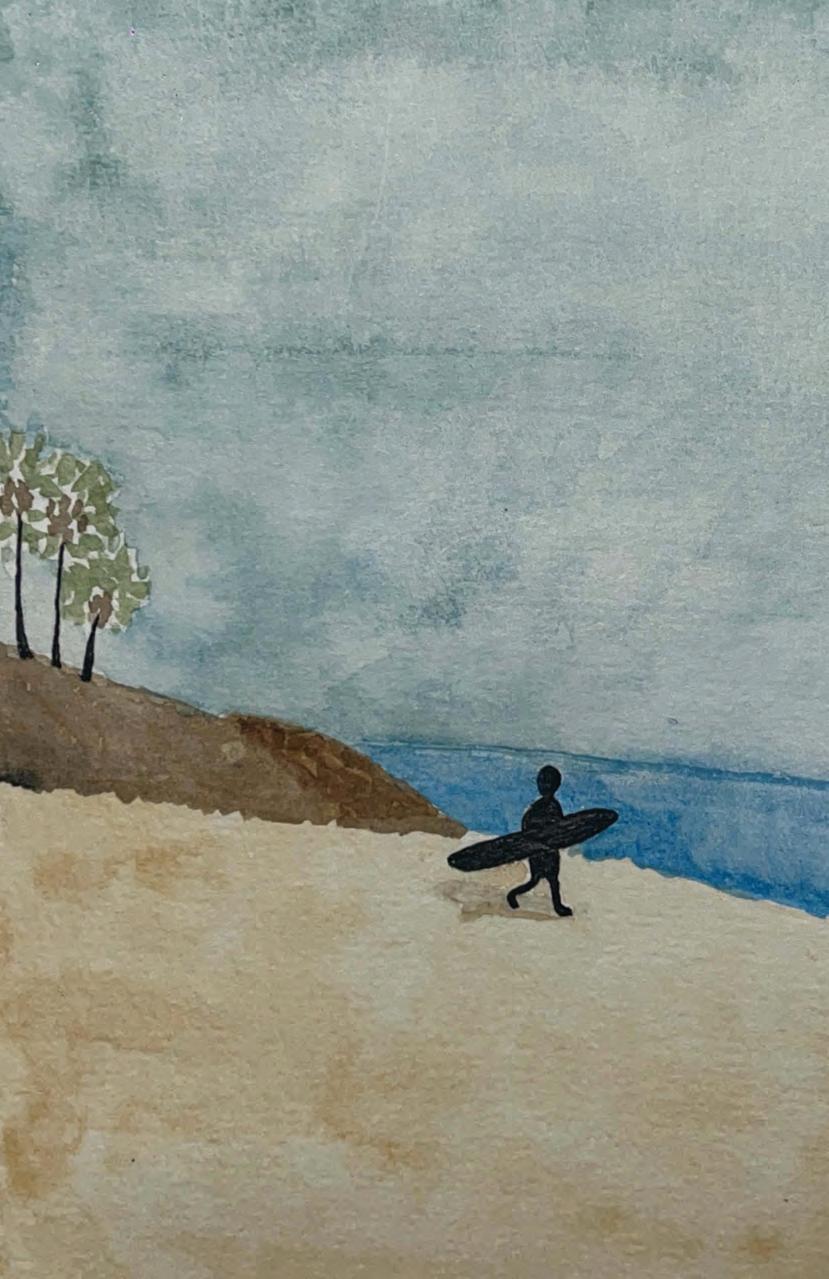

FROM MY SKETCHBOOK II (p. 138) (Hazel Rodriguez)

MOMENTS (p. 142)

I. Moments in Dubrovnik (Sophia Carlston) II. Dans Maastricht: An Exploration of Movement in the Netherlands (Zoë Breininger)

III. Stockerkahn Races (Bradley Kutchukian) IV. Denouement is a StoneShaped Brick (Everett Shinn)

FROM MY JOURNAL (p. 160) (Rachel Brooks)

n. 1. an agreed arrangement to go somewhere or do something at a specific time 2. the act of being involved in an activity

Before my semester began, I had a general idea of what to expect in Berlin: edgy individuals in black and exclusive, intimidating techno clubs. I realized that my image of the city was pieced together from TikTok snapshots; a portrait built by tourists and filtered through the lens of strangers. When I arrived, these preconceptions faded and proved they were only a piece of reality, not completely untrue but by no means encompassing the city in its entirety. Berlin offered so much more than I had imagined, providing an array of opportunities to explore. One in particular stands out among the rest, beating as the heart of the city: techno.

The influence that this genre, which I once dismissed as a bunch of sounds, could have on an entire city was unknown to me at the start. I understood the influence of hip-hop on Black Americans, reggaeton on Latinos, and reggae on the working class of the West Indies. All these genres have something in common - words being the catalyst that moves people - but techno was something I never understood. Yet, as the weeks progressed, so did my exposure, and I began to see why this genre, wordless and raw, held Berliners so tightly in its grip.

Born from the ashes of Detroit’s riots, techno emerged in the mid-1970s and flourished in the 1980s. A sound shaped by ruins, resilience, and synthesizers, techno has influences from a variety of genres including hip hop and

the German band Kraftwerk. The Civil Rights Movement and the more recent riots and war on drugs resulted in heavy industrialization in Detroit, thus leaving individuals with immense free time which, for some, sparked artistic productivity.

But, while a techno revolution was brewing in the West, repression and division persisted in Berlin - until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. The city, once split into two, joined together. East and West neighbors, long divided, walked freely among each other, strangers but kin. This newfound community was in desperate need of a reunifying force. Techno was the answer: a universal language of radicalism that mended the city’s scars after the life they once knew had fallen apart.

Tresor was the first techno club I went to in Berlin, and it soon became the one I frequented the most. What I find so amusing about this is that I didn’t even enjoy the music at

first. But there was a pull that kept bringing me back, not just to Tresor, but to the variety of techno clubs sprinkled throughout the city. Here I am now, writing and listening to techno, still wondering about the force that drew me to an environment playing music I didn’t even like. In time, with the help of my “German Popular Culture” course, I found answers. This music was much more than a collection of sounds, but rather a hidden language I was beginning to understand.

Taking us back to the Wall’s fall and its cultural impacts in Berlin, Dimitri Hegemann saw the rise of a new community that needed a place to connect. From this vision, Tresor, the first techno club in Berlin, was born. The melancholic sounds of the synthesizer resonated with the melancholic city. The melodies and rhythms layered within the music evoked movements and emotions that the daylight could never awaken. Techno was more than entertainment, it became a form of therapy, a language of freedom that spoke to the soul. Berlin’s clubs provided a unique refuge from day-to-day life, where time seemed to stop and, for a few hours, the stress of the outside world disappeared. These spaces, like adult playgrounds, invited all to express themselves without fear, transcending the boundaries of age, gender, and class. They were an oasis of liberation in a world that asked for conformity.

One of the preconceptions I carried about Berlin’s clubs was their exclusivity. This notion was molded by stories of Berghain, the world-famous club that attracts thousands yet turns most away. This idea of unpassable club gates seemed to define the city’s techno scene, with long lines of hopefuls rejected in the end. Naturally, one may assume that the clubs are extremely exclusive. However, the exclusivity here is unlike the superficiality of clubs outside Berlin’s borders, particularly in the US, where money and status trump fun and entry is based on physical attractiveness

and whether you fit the aesthetic of the club. Berlin isn’t about status or wealth but rather belonging to a culture. Many of these clubs were originally gay or queer clubs, with clubgoers concerned by judgemental techno/sexual tourists who would disrupt the culture that thrives within club walls. The intent of the clubs is clear: to create a utopia, an outlet for individuals of all backgrounds to express themselves without fear or shame. This concept is evident through their no-photography rule - a gesture to preserve

these spaces of self-expression and protect against the invasive grip of technology that plagues the outside world - allowing for a brief moment where everyone can be free.

From everything I have learned about techno culture, I can say with certainty that I’ve come to deeply appreciate the sanctuary it has created within Berlin’s nightlife. My time in Berlin has challenged my preconceived notions about the city, particularly within its techno scene. While I had been familiar with Berlin’s reputation for edgy nightlife and exclusivity, I came to understand that techno in Berlin is far more than just a music genre: it is a medium of social healing and expression. My experiences allowed me to challenge stereotypes and showed me that Berliners’ love for techno grew out of a desire for unity and freedom in the aftermath of repression. Unlike other nightlife spaces where exclusivity hinges on status or appearance, Berlin’s clubs foster inclusivity rooted in shared values of openness and authenticity. Berlin’s techno scene not only let me engage with a different form of music but also witness how a city’s history and values can be preserved and expressed through it.

So, when a bouncer waves you away, remember that it’s not a rejection but a silent safeguarding. The spaces don’t ask for an alteration of style or persona but are rather an invitation to come as you are with good vibes and an open mind. I’ve seen plenty of people turned away at the door, each seemingly out of sync with the particular haven that has been entwined into the heart of that club, at least in the bouncers’ eyes. Ultimately, Berlin offered me a transformative, cross-cultural experience, unveiling the power of embracing and truly understanding unfamiliar places and communities.

- Nailah Lloyd-Jones

While studying abroad in Maastricht in the fall of 2023, I had the privilege of attending my first Formula 1 Grand Prix. With heavy rain, crashes, and takeovers galore, it was, put simply, electrifying.

Hosting a total of 33 Grands Prix, Circuit Zandvoort is one of the most frequented in Formula 1, giving it some oldschool charm. Similar to Silverstone, Circuit Zandvoort was constructed in 1948 when motorsport culture was gaining momentum in Europe. Since its completion, Zandvoort has witnessed victories from some of the world’s most renowned drivers, including Juan Manuel Fangio, Graham Hill, Jim Clark, Niki Lauda, James Hunt, Nelson Piquet, and Max Verstappen, to name a few. I had the pleasure of visiting this circuit only two years after its 36-year hiatus ended. What makes this circuit so exciting is that Zandvoort’s track configuration contains some of the most challenging corners in Formula 1.

As a beach town in northern Holland, Zandvoort also experiences some pretty extreme weather. When I arrived for qualifiers, the August heat from the south had miraculously vanished. Wearing my Sunday best, I was met with pouring rain, 10 mile-per-hour wind, and freezing temperatures.

The highlights of qualis were Charles Leclerc’s and Logan Sargent’s crashes in the Q3 phase when they lost control of their cars and collided with the barriers at full speed, leaving them on the sidelines for the day. This is just one of many examples of Leclerc’s deteriorating relationship with Ferrari’s car this season. The car’s balance has undoubtedly cost Ferrari points and Leclerc pole positions. Leclerc was

left starting in ninth on the grid. As for Sargent, he had a lot of eyes on him as the rookie of the season. Although the driver had completed qualifying for the first time, his victory was short-lived as he crashed heavily at turn two, causing him to slump down to 10th on the grid. Surprising no one, Dutch driver Max Verstappen took pole position for Red Bull, creating a moment of pride for his country. Lando Norris similarly has reason to be proud as he took the second position on the grid, which was rare for the McLaren driver at the time. George Russell, Alex Albon, and Fernando Alonso followed.

Race day fared no better, weather-wise. Spits of rain crept up before the big countdown, leading to a sudden downpour within the first lap. Rain serves as a test for each team’s strategy and talent, making it a truly intense experience. The teams had split strategies to combat the rain, but Red Bull took the lead. Verstappen led the pack on slicks while Sergio Perez and others boxed for intermediates. The wrong tires will make or break a driver’s position within the grid. With the rain getting worse, cars that were on slicks frantically made a switch, while those who made an

early change to intermediates rose to the front. Before the rain eased up, the cars that stayed on slicks fell to the back of the pack. After boxing, Verstappen had fallen to fourth, with Zhou Guanyu, Pierre Gasly, and Perez battling for P1. This struggle came to a startling end as Zhou slid through the wet into the barrier at turn one, leading to a red flag that halted the race.

The drama, however, was far from over. Joining Zhou would be Leclerc, whose car had picked up damage, and Sargent, who outdid his quali performance with another crash. Moreover, Liam Lawson, stepping in for an injured Daniel Ricardo, made his debut appearance. With less experience in the rain than the other drivers, Lawson did well, finishing at a solid 13th on the grid. Alonso secured a second-place finish, making this his first podium since Canada in June. Perez initially secured a podium finish but was hit with a five-second penalty for speeding in the pit lane, landing him in fourth. This bolstered Gasly into a podium position,

which was well deserved considering he started in 12th. Ferrari’s Carlos Sainz and Mercedes’s Lewis Hamilton followed. This race was especially frustrating for Hamilton, who had yet to take a podium position this season and had a solid shot at Zandvoort. Hamilton attributes his lack of success to Mercedes’s strategy, leaving him with old tires towards the end of the race. His P1 position was lost, and he was quite literally left in the dust. Given the unusual number of crashes, you can also argue that a late safety car disrupted Mercedes’ strategy, but, then again, who is to say? Despite the chaos, Lando Norris (P7), Albon (P8), Oscar Piastri (P9), and Esteban Ocon (P10) were able to score significant points for their teams.

After securing a first-place finish at the Dutch Grand Prix for the third year in a row, Max Verstappen had the most to celebrate. Frankly, as a Dutch driver, Verstappen had no other choice. The crowds came alive when he crossed those checkered lines. With Red Bull fans dominating the circuit, the Stadiums were painted with red, white, blue, and orange. The Dutch wear orange as an emblem of national pride in honor of the country’s first king, William I, the Prince of Orange. This was just one of the many ways I got to learn about and experience Dutch culture while attending the Grand Prix. Although I am American (and was rooting for Ferrari), people welcomed me with open arms. I had the pleasure of meeting people from all across the country and am eternally grateful I got to experience the race within a new culture. Immersed in the stands, I had never felt so connected to my host country than at the Dutch Grand Prix. It is true: sports have a way of bringing unlikely people together.

- Tessa Baker

Rome. A place of slow living. A pace of life that embraces the human desire for indulgence. A love that includes lots of tomatoes and lots of Nutella.

Words really can’t describe or define what my experience in Rome was like. The fresh air, the parks, the people, the language: they are all a part of this fairy tale in my mind that I float into when dreaming. Looking back on my experience, I was able to learn so much about the culture and the cuisine, but one of my biggest takeaways was my yoga mat. Now, you may be thinking, “How is that possible?” It might sound crazy to you but the most memorable experience for me was not the historical jungle of the city or the beautiful Colosseum that is nestled in the center. It turns out this memory lives instead in the small holein-the-wall studio named Jiva Yoga. Practicing yoga each week was a dream, but not the original dream that I had in mind. One day while at my favorite café, Gelateria Giuffrè, minutes from my apartment in Rome, I was studying for my Italian exam, tucked away with my cappuccino al ginseng. After freshly dipping into my gelato goodness, I overheard a woman talking about a free yoga class in the park. I did some research and found that Trastevere, the place where I lived, was crawling with yoga studios.

When I arrived in Rome, I was on the search for a good dance studio because dance has always been an important part of my life. After weeks of research and outreach, I still had no luck, so I thought I would give a yoga class a chance. In the first class I attended, Benni, the owner of the yoga studio, asked if I spoke Italian. I reluctantly replied “Un po’” and pinched my fingers together to demonstrate just how little I knew. She quickly responded in Italian saying, “Beautiful! This is a great place to learn.”

I sat on my mat in awe of the language spilling over into the space. Each class from then on was completely in Italian. I have to admit, it was challenging trying to learn the phrases, movement cues, and language that I was unfamiliar with during class. I would walk away in tears some days, feeling so discouraged because I messed up or didn’t know what to do because I didn’t understand the language. But it ended up becoming a rewarding challenge because I saw myself gaining strength, not only in the movements but in my Italian language comprehension as well. It became a place where I learned how to feel comfortable trying to speak while also being extremely intentional about learning to listen. I would sit with my eyes closed, spine straight, and shoulders relaxed, listening to the phrases, the words, the noises all around me. I remember the first day, feeling so lost, like all of the words she was saying flowed into one another, but, by the end, I was able to comprehend and distinguish pretty much word for word what she was saying. Jiva Yoga is not just a yoga studio. For me, it was a place of respite. It was a place of learning the culture, the language, and the practice.

Attending yoga classes every week provided an anchor in my schedule. With each session, I gained strength, not only in my physical abilities but also mentally. Guided through meditation, I learned to silence distractions and listen to the wisdom within my body, intertwining this practice into my physical routine. To my surprise, I discovered newfound passion and grace with each challenging pose, gaining control over the connection between mind and body.

One month, I remember the sessions heavily emphasized inversions like headstands and crow poses. I was initially intimidated but felt the team of classmates and instructors around me embrace the challenge. So, I did as well. I was continuously impressed by my body’s capabilities and also the strength of those around me. Other members of the class would circle me and encourage me or assist me with a pose, then I would do the same when they needed it. A highlight from these weeks was being invited to the front row beside the lead instructor, Benni. This felt like a true testament to my dedication and progress. I found my rhythm and flow tuning into the mental and physical space I practiced in each week. I will always remember this week marking a significant milestone in my journey of selfdiscovery and communal trust.

I feel that this opportunity to do yoga was a blessing because I opened myself up to a new way of moving that helped me connect the ideas I was learning in my academic classes to what I was doing on my own. The Slow Food movement and the Mediterranean Diet are two topics that we dug into while in Rome. A common theme between these two topics is the importance they place on building community and supporting locals. I feel that I connected to the community in both of these ways by taking classes at this yoga studio. I felt challenged at the studio physically, and I also felt connected to a deeper purpose in the community.

So now, hopefully, you understand why the architecture of the Colosseum was not the most memorable part of my time in Rome. Hopefully, I was able to paint a picture of the memory of a dream that my yoga experience was in Italy. As I sit here now, I am reminded of my breath, my awareness, my purpose. I will take the lessons I learned in Jiva Yoga with me everywhere I go. Like we ended every yoga class in Italy, I will end with you here: Peace be with you. Namaste.

-Emma VanGorder

When I reflect on my time spent abroad in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany this past semester, I can recall many occasions where I was faced with unexpected obstacles or social norms of the culture that surprised and challenged me in new and exciting ways. Looking back, one memory stands out in particular as something I will hold onto for the rest of my life.

Before the beginning of what is typically understood as the liturgical season of Lent within the Roman Catholic Church, there is a festival period in the southwestern part of Germany known as Fastnacht. Traditionally, this is a time to let out sinful behaviors before a season of repentance leading up to the Resurrection of Christ on Easter. In the United States, many individuals celebrate Mardi Gras or “Fat Tuesday.” The concepts are similar in nature, and both involve drinking, eating local cuisine, and engaging in exciting parades around the city. During Fastnacht, I attended a local parade in Freiburg and witnessed the traditional costumes of witches and scary woodland spirits that townspeople wear. These were originally intended to scare off spirits of ill will, which is comparable to the tradition of donning Halloween costumes in the United States. This parade was exciting, and local German people pointed us in the direction of carts selling mulled wines and warm pretzels as we watched marching bands and troops of people clad in handmade traditional costumes take to the streets of the city center.

Later that week, after discussing this experience with one of the academic staff, I was informed of a similar celebration happening in a city not too far from us: the Morgenstreich, or morning prank, which takes place every year in Basel. At

4am, crowds would gather throughout the city and every light in the city center would be turned off. Then, the bell in the clocktower would ring and a procession of masked and costumed lantern bearers would walk the streets until sunrise. Determined to experience this festival, I attempted to recruit classmates to come with me but was unsuccessful. This did not deter me, and, at midnight on the eve of the event, I set off on a regional train excited for what lay ahead. Upon arriving in Basel, I walked from the train station to the center of town; having visited previously, I

already knew my way around. Traversing the city square, I noticed a lively hum from the local pubs surrounding the area and considered stopping in. Before I had the chance, I was approached by another woman who seemed to be lost. She happened to be a German student studying a few towns over from Freiburg and was also in Basel to experience the festival for the first time. She had not been to the city before and asked if I was familiar with the layout. I told her I was, and we began a conversation. When I told her I had traveled alone, she was surprised and invited me to join her and her group of friends, including another German student, a student originally from Istanbul who was doing a graduate program, and another one of her friends visiting from London. Together, we managed to find a student hall similar to the ones I frequented in Freiburg, and we sat down to exchange stories.

When 4am came around our group took to the streets, as did seemingly the entire town of Basel as well as many other travelers, and we waited with bated breath to see what was in store. I don’t think I will ever forget the eerie sounds of the woodwind instruments that floated through the air as the procession began, or the unexpected sense of community I felt in that moment. The experience I had at the Morgenstreich was something I carried with me throughout the rest of my time abroad. It inspired me to take risks and embrace every opportunity to seek out the unfamiliar in a way I hadn’t before.

- Grace Wilson

n. 1. a relationship in which a person, thing, or idea is linked or associated with something else 2. the action of linking one thing with another

During my semester abroad in Queensland, Australia, I lived with a host family in a very tight-knit community. I spent time with three women from the neighborhood who were all kind enough to speak with me about their experiences living in Australia and how they felt about America. These are their portraits and their stories.

Sue loves tea and having chats at “teatime.”

Sue has spent the past 73 years of her life in Australia, but she was born in a slave labor camp in Germany. When asked about her favorite natural place in Australia, she told me about Noosa Head, a beach town that used to consist of a single one-way street with very few people. As I asked how this place had changed over time, she was sad to admit that it was no longer the natural sanctuary she remembered from childhood. Now, Noosa has been built up into a tourist destination: beach houses line the shores, pollution visibly impacts the beaches, and wildlife, both on land and in the water, has been driven away from the area as a result.

Sue has been to San Francisco and New York, and she fondly remembers her time spent in Redwood National Park. However, when asked about her thoughts on America, she had very few positive things to say. To her, capitalism

was obvious as an outsider in New York City, and she was appalled by the homelessness in California. Her remarks on America were that women seemed “obsessed with beauty,” the politics were “unbelievable,” and she “hates the shootings” and gun laws.

Patty

Patty loves her dog, Giuseppe.

Patty has lived in Australia for her entire life, as has all of her family. Her favorite natural places in Australia are the Gold Coast beaches, as well as Noosa Head. Recently, the Gold Coast beaches were washed out, and Noosa has experienced flooding in the past as well. She remarked that she has seen the impacts of climate change on these beaches unfolding over her lifetime, as well as a huge increase in development and infrastructure in all of Australia. Curious about this, I asked her about bush land, which she says has been mostly unaffected except for bushfires. She told me that a major debate in Australia is planned burnings, which some people dislike. As a result of fewer planned burns, natural burns

can be more catastrophic. Patty recalled an especially harsh fire that took place on Frazier Island when people did not put out a fire while camping. She remembers this fire in particular because many koalas were burned.

Patty has never been to America, but she does want to visit her friends that live in Washington state. When asked about her general perception of America, she remarked on how “crazy” the gun laws were to her and how obsessed Americans were with politics. She also said that everything in America seemed to exist on a much larger scale than in Australia, including the size of people, which she associates with an unhealthy lifestyle and food choices.

Nicole, a single mom, loves her kids, Jazz and Billy. Jazz loves Blue Takis and Billy loves koalas.

Nicole was born in Australia but lived in London for eight years during her early childhood. She came back

to Australia to be near her family, most of whom live near Sydney. Her favorite natural place in Australia is Montville on the Sunshine Coast. She has always loved the beaches, but they have become much more touristy than she remembers from childhood - filled with more people, more development, and more trash and pollution. She also remarked that the dog park in her neighborhood is one of her favorite places because of the natural community that exists for her there.

Nicole has been to America before, having taken multiple trips to New York and San Francisco. She also spent two full summers living and working as a midwife in the Hamptons. The first thing that comes to mind when she thinks about America is gun control. She told me that she is afraid to take her children there because she has heard about so many mass shootings. She also remarked that everything in America appears to happen on a much larger scale, and she felt that people were very wasteful with their resources, like food and money. Weather was also a big issue for Nicole, who does not like the cold, and found

America to be much colder in some areas than Australia. Weather patterns were noticeably different to her in terms of how much rainfall she experienced. Nicole did, however, like the shopping in America and spoke about how there is always lots of entertainment and something to do. Overall, she found America most similar to Australia in comparison to the European and Asian countries that she has visited.

- Courtney Swenson

“It was our last night in Edinburgh, and we wanted to make it count.” That’s how most crazy stories start, right? People go out, have a fantastic time, and end up somewhere ridiculous “for the plot.” They meet incredible people and return just in time for their flight back to wherever and then they never speak to those people again, for, after all, it was just a night out. Well, for us, that’s almost the truth. Let me tell you about the war that forged perhaps my most unbelievable friendship to date (he would probably say the same).

It was our last night in Edinburgh, and we wanted to make it count. Hopefully, we’d meet some new people and see some of the nightlife before our 3:30am bus to the airport. My best friend Isabella had come to visit me while I was studying in Chichester, England and we decided to have a Scottish adventure. We had a brilliant time exploring and seeing the sights, but we really wanted to meet some new people at our hostel for our last night out. We had decided to join the hostel’s “mini” bar crawl to a small bar and then a place called Ballie Ballerson, whatever that was. Problem was, we messed up the timing and the group left without us.

Eventually, we decided to just go on our own to the second place and see what happened. We had looked it up and apparently Ballie Ballerson was a “ball pit bar” (shocking) which essentially meant it appeared to be a regular bar downstairs, but upstairs it had a ball pit. That’s right. A. Ball. Pit. Like the kind they had when you were a kid, filled with primary-colored spheres of plastic that made the most satisfying rumble of a wave when you fell into them. This bar had an entire room dedicated to one of those. Naturally,

Spittelau Incinerator, Vienna, Austria [Isabelle Goings-Perrot]

we had to check it out; maybe we would even somehow run into the group from our hostel or at least make some cool new acquaintances.

We arrived at the neon-colored fantasy land of Ballie Ballerson and acquired the wristbands allowing us access into the ball pit. After some rather crazy cocktails (there was a Capri-Sun version and Fun Dip was involved - we had to!), we decided to make our way up the strangely grand staircase to the second floor. After a few turns down the slide - because yes, of course, it was absolutely necessarywe went to the main event: the ball room. They somehow managed to make a ball room as far removed from the grimefilled memories of a McDonalds playplace as possible; the walls and ceiling were full-length mirrors, the lights were

teal, and the balls were semi-transparent white, almost like knock-off crystal balls. Overall, the effect was like a trippy secret hideout, exactly what a bunch of tipsy adults wanted so they could act like children again.

And children we were. The moment we stepped in, a shout of “NEW PEOPLE” rang out and immediately we were showered with plastic balls by every single person in the room. Laughing, we waded into the pit to get a better angle, and the battles began on every front. Soon, Isabella was targeted by a young guy named Saliou from Senegal, and, between being buried under the tides of plastic balls and

properly retaliating, I was left to fight my own battles on the other side of the room. There appeared to be a young sandy-haired guy trapped in the corner taking a break: the perfect target.

I began steadily launching the balls at him when he wasn’t looking and one of them, maybe my best shot of the night, nailed him right on the forehead. He laughed, startled, and looked around in shock. Once he realized I was the one who threw the perfectly placed projectile (perhaps because of the triumphant grin on my face, we will never know for sure…) he “figured he’d go all in” and completely recoiled, falling dead weight into the pit and sinking like a stone. I burst out laughing, looking up just in time to see him pop up out of the pit with a triumphant grin of his own, launching a ball that hit me square in the chest, knocking me over.

My vision went white, all I could see were plastic balls up and around me, and the laughter of my foe rang out across the room. Oh, it was on. For the next 20 minutes, a furious battle unlike any the world has ever seen was fought without words, using only plastic balls and dramatics. After those 20 intense minutes, I was completely spent, and my opponent managed to disappear into thin air. I waded back to Isabella and found she was still talking with Saliou, and together the three of us, plus his two French friends from school, made our way out of the ball room to the secondfloor balcony for a break.

Turns out, the three French guys were from our hostel! We had accidentally found the people we were looking for and they were leading us back to the group we had meant to join in the first place. As soon as we arrived at the table of about 10 people, I spotted him: my opponent in the furious pit battle. He looked up and froze. “It’s YOU!” his accusing finger jabbed across the table. I started at the shout, but the smirk twitching on his face belied his gruff tone and I just

grinned and waved back.

It turned out Tim (for that was my opponent’s name) was also staying in our hostel and it was his first night there. He was a sergeant from the Netherlands and about as bad a dancer as I am. Apparently, over the course of the night, our little group of six was so entertaining to watch dancing around and having fun that two older women came up to tell Tim and me that our dancing made their entire night. I managed to teach Tim a couple of ridiculous American line dances and our group even had our own dance circle. After leaving the bar and wandering around Edinburgh for a bit, chatting about nothing in particular, we meandered back to the hostel around 12:45am for a card game or two, since Tim always had a deck handy for just this sort of occasion.

After a few rounds where I was pretty much destroyed and everyone else had gone to bed, Tim and I played one more game (where I once again lost). We then hugged, traded Instagrams, and parted ways to our separate rooms around 1:30am. I dragged myself out of bed an hour and a half later, and Isabella and I caught that 3:30am bus to the airport just in time. Later that day, I was surprised by a kind text from Tim asking if I had made it back okay, and we have been talking ever since. It’s been about seven months now and, to this day, he and I are good friends, calling every now and then to catch up.

As for the “vampire” bit, well, I only met him in the dark of night, he has an affinity for vampire novels, and, to date, I have never seen him, even in a photo, in the light of day. You never know who you might meet out there.

Tim, my vampiric friend, if you ever read this, you owe me a card game.

–Hannah Angelico

Leading up to my semester in Maastricht, I was made aware of the bluntly honest nature of Dutch people. In other words, I heard that a Dutch person would not beat around the bush or hold their tongue to be polite – they would tell you exactly what they thought. I assumed I would find this approach refreshing and was not too worried. Looking back now, I remember the first time I really experienced the signature Dutch directness. I was at an event hosted by my school, University College Maastricht, and there was a pretty good turnout because food and champagne were involved. My friend and I were enjoying our dinner at one of the tables when, suddenly, we heard “You need to move, I am cleaning up. The event is over.” Stunned by the words and tone of the staff member, we quickly grabbed our plates and left, joking that we now understood what people meant about how the Dutch do not sugarcoat.

Although I was not nervous about the bluntness I might encounter abroad, something I was considering was how I would look after my physical well-being while I was away. Physical activity has always been an important part of my life, and I know how impactful exercise can be for emotional well-being, too. Thankfully, I was able to design a project around comparing Dutch and US fitness culture. Part of my project included attending Pilates classes in Maastricht and interviewing my instructors to better understand the customs and beliefs surrounding physical activity in the Netherlands.

I would begin these conversations by discussing a few statistics related to fitness and well-being. For example, according to a study of 29 countries from around the world published in 2021 by Ipsos, the Netherlands was the most physically active of that group. I also presented the findings of a study from 2020 conducted by the Commonwealth Fund that published data concerning mental health statistics in the US compared to other high-income countries,

including the Netherlands. The study revealed that people in the Netherlands are among the least likely to experience mental health struggles while people in the US were firstor second-most-likely to experience them. The data also showed that Dutch people were least likely to want to see a professional if they were experiencing emotional distress (compared to the US, which scored second-most-likely to want to seek professional help).

When speaking with my fitness instructors, I would inquire about their reaction to these statistics and ask them questions regarding their opinions on the findings and their personal experiences with exercise. I decided to begin interviews with these studies because I thought sharing information would be a good ice breaker and ground our conversations in fact. Generally, my instructors were not familiar with the research but were also not surprised, and they felt that the findings were accurate. After discussing the research, it became easier to ask more personal questions about physical and mental well-being.

The first interview I did was with a Pilates instructor named Aafke. This conversation was a nice way to ease into the interview process. I had been feeling a little intimidated to introduce my project to the instructors and ask them questions, especially because I suspected that they wouldn’t be afraid to tell me if they didn’t feel like taking time out of their day to talk to me. However, my interview with Aafke settled my nerves a lot. I always went to her classes because they were challenging but fun and full of laughter. She is a very warm and funny person, and it was easy to talk to her.

During our interview, Aafke told me she was not surprised about Dutch people being the most physically active or about Dutch people not wanting professional help with mental health struggles. Aafke stated that the results felt accurate based on her experience, and she explained that

many Dutch people take pride in fixing things themselves. She did, however, express that there may be a shift in stigma around mental health among younger generations. Another question I asked in all my interviews was whether they viewed cycling and other forms of exercise in the same way. The answers I got varied slightly. Mostly, people said riding a bicycle is a form of transportation rather than exercise. Aafke was very sure about this division. When I asked her opinion, she said that she doesn’t view cycling as exercise at all - it is “purely transportation.”

By the time my program was nearing its end, even though I had conducted several interviews and my nerves were settled about the process in general, I was still anxious about my last interview with my instructor Metcheld. I was a little intimidated when I first met her. Metcheld is tall and confident, and, when I first took her class, she seemed like a talented but stern instructor. Whereas I immediately felt at ease and welcomed during the first class I had with Aafke, my initial class with Metcheld felt stricter and more serious. I remember at one point we were doing an exercise called the hundred. Most of the time, instructors would count this movement out by tens, but Metcheld said clearly that it is never the job of an instructor to count. I definitely felt like the stereotypically candid attitude fit her personality.

I got to learn more about her during our interview, and I realized my impression of her as stern and overly blunt wasn’t true. While answering one of my questions about how physical activity impacts her mental well-being, she shared with me that she struggles with depression and told me how much exercise helps. We talked for a long time, and I saw beyond my assumptions of her as aligning with the stereotypically direct attitude of the Dutch, experiencing firsthand how sweet and sensitive she could be. This confirmed my initial feelings about Dutch bluntness as something that shouldn’t be overly intimidating.

Leading up to my time abroad, I was not worried about people being upfront. If anything, I was looking forward to experiencing a different culture that values honesty. When I actually experienced this bluntness, I thought it seemed more like rudeness. This is probably because I am accustomed to the US, where pleasantries and concealing truth to be polite are the norm. Over time, I understood that this Dutch attitude was not something one should find off-putting. Through my time abroad, I gained insight into how cultural norms vary, and I learned to be open to different cultural practices. I walked away with the lessons of not being too quick to judge and to look beyond bluntness or overly negative first impressions. I learned that initial assumptions are often informed by a narrow worldview, and that rethinking my early judgments can help expand limiting beliefs.

- Tulsi Perun

n. 1. the action of moving across, over, or through something

2. the act of being a place where two roads, paths, or routes meet

3. a passage through a border

Looking Down at the Lodge, Innsbruck, Austria [Bradley Kutchukian]

As I carried my overweight suitcase down the stairs, millions of thoughts raced through my mind. Soon, I would be saying goodbye to my family and heading on a grand adventure. Up until that point, I could only dream of what life in New Zealand would look like from the pictures online of fields filled with sheep or the breathtaking landscapes of mountains and beaches. Now was my chance to finally see New Zealand, and I looked forward to the journey ahead. When I made it to the last step, I looked back at my house and breathed in the sweet jasmine scent that filled the air and took in the scenery around me one last time. I would miss this place and my family but there was comfort in knowing that, in a few short months, I would be back home. As my parents and I drove away, I rolled down my window and looked at the palm trees swaying in the wind and the bright crescent moon shining above me. In this moment, it felt as if they were waving goodbye to me and wishing me a safe adventure.

With the song “How Bizarre” by OMC, a New Zealand group, playing in the background, my parents and I talked about the journey ahead as we drove to LAX. This was an exciting time since I would be the first in my family to travel to New Zealand. I would also be spending New Year’s on the plane and would begin 2024 in New Zealand.

Before I knew it, I could tell we were close as I saw the colorful bamboo lights in the distance. After checking in for

my flight, I gave my parents big hugs and said I would text them as soon as I made it to my gate. As I passed through security with my special Aix-en-Provence canvas bag from Pâtisserie Weibel, memories of studying abroad last summer came to mind: picking up freshly baked croissants, walking in lavender fields, swimming in the Mediterranean Sea, and dancing with friends under the streetlights. Three weeks in the South of France created memories of a lifetime, and I could hardly wait to see the adventures that New Zealand would bring.

Waking up the next morning to a bright orange sky with clouds resting underneath was magical. While most passengers were fast asleep, I happened to be one of the few completely mesmerized by the sunrise. As the sun lit the sky, the world beneath it began to slowly reveal itself. Incredible ranges of mountains and greenery filled the landscape in front of me. I could hardly believe that I had finally made it after a 14-hour flight.

After getting off the plane, curiosity and excitement overtook me at the thought of being in a different part of

the world. I was looking forward to meeting new people, learning about the Māori culture, spending time in nature, and exploring New Zealand. As I made my way to the front of the airport, I was welcomed by a friendly guide who picked up the students in our program. One of the first things he said was for us to walk on the left side of the street since that was the way they did things here. After almost bumping into several people, I eventually loaded my suitcase into a van that would take us to the residence halls in Auckland.

As we drove along the motorway, I stared out at palm trees and the greenery around me and was reminded of home. It was strange to be in a new place that looked so similar to home yet was so far away from it. Chatter filled the van as we asked our guide questions to hear the inside-scoop on New Zealand. Early on, we learned that New Zealand is filled with volcanoes, some being active while others are dormant. Our guide recommended that we hike Rangitoto Island to see views of the city and walk on trails surrounded by magma that erupted on the site approximately 700 years ago.

As the van approached the residence halls, we thanked our guide for his insights, and he wished us the best for our travels and studies. After entering a 40-story orange building, I was welcomed by a receptionist who said “Kia ora,” which means hello in Māori, the indigenous language. We’d say this often in the upcoming weeks and months. After going up the elevator to the 21st floor, I was reunited with some HWS classmates that I did not know too well at the time, but we soon became close friends.

There’s nothing quite like the feeling of walking along the streets of a new place for the first time and exploring a new part of the world with friends. You find yourself lost in a complete state of wonder, and, before you know it, you gain a sense of familiarity. After attending classes, doing a film internship with Doc Edge, and exploring other parts of the country through class trips to Waiheke Island, Rotorua, Tiritiri Matangi, and the South Island, I really came to appreciate the way of life in New Zealand. People in Auckland are fortunate to have access to so much nature, from city parks to surrounding mountains, beaches, and islands. It opens the opportunity for them to spend time

in the outdoors and it becomes integral to their lifestyles.

As I would discover during my time abroad, many people in New Zealand take on sustainable practices like growing fresh fruits or vegetables in their gardens or drying their clothes outside. When I lived in a homestay, I learned that, when there was a surplus of fruits, they would share with their neighbors and friends so that none would go to waste. The New Zealanders that I met were very kind and generous and looked out for those in their community. From the moment I got off the plane, I found that New Zealanders were welcoming to newcomers in their country. This experience would continue for the duration of my time abroad as I witnessed locals offering a helping hand to visitors in the community.

The Māori culture class that I took at the University of Auckland was crucial to my experience abroad. It deepened my knowledge of the history of the land on which I walked and informed me about current events including indigenous rights and claims to the land which continue to affect the Māori way of life. This significantly helped me engage with people in the places that I visited because I could have informed conversations with them and discuss topics that I studied in class. I will always treasure New Zealand for the unique experiences it brought me and the friendships that I made. I will also hold onto memories of listening to music in the Domain with friends, bus rides to Mission Bay, hiking Rangitoto island, surfing at Muriwai beach, and ice cream runs to Giapo.

As New Zealanders would say, “Island Time” is the best way to live. This expression means that, by taking on a more relaxed and slow-paced lifestyle, you have the chance to appreciate the world in a different way. During our class trips to Tiritiri Matangi, our guide encouraged us to take in all our surroundings and to simply be present in the

moment. As we walked around the sanctuary, we came across breathtaking views of coastlines and heard melodies sung by native birds including pīwakawaka, takahe, kererū, and tūī. Being immersed in the heart of nature awakens one’s senses and curiosity of the world. It is within these moments that meaningful reflections can be made. While abroad, spending time in nature became a way for me to find a sense of comfort and belonging in a place foreign to me. It connected me to new communities, and it gave me the opportunity to explore and discover the hidden gems of the country. New Zealand became my home away from home.

- Mia Tetrault

Boobs. Everywhere. Saggy boobs, perky boobs, Black boobs, White boobs. Boobs as far as the eye can see. The women’s gym locker room at Fitness X beams with fluorescent lighting, making every inch of these women’s bodies extremely visible. The women’s changing room, a liminal, safe space for women to undress and decompress after a workout, is home to the naked body, but I had never known naked like this until arriving in Denmark.

In my native United States, gym locker rooms are used for the same purpose, but it is highly unlikely that you will find women parading around nude. I find it hard not to stare back when it feels as though the boobs are staring at me, but I quickly know to avert my eyes before I feel like the odd one out. Almost instantly, I feel a sense of maturity, like I’m no longer a child who snickers at the sight of a naked body. I want to know what gives Danes such a sense of confidence when it comes to being naked in a communal space and how it has become so normalized among everyone. I quickly pack up my bag, eager to get back to my apartment. The walk home is brisk, my HOKA running shoes eat the pavement beneath me as I think about all of the questions I’m going to ask my Danish roommate once I get back.

“It’s completely normal,” she says as she looks at me like I’ve just asked a stupid question. Signe is 25 and has shoulder-length, dirty blonde hair and eyes the color of a stormy ocean. The soft wrinkles around her eyes suggest that she doesn’t wear sunscreen often, only when she plans on sunbathing. Those stormy oceans look at me with intent as she realizes I am seriously intrigued about the normalization of nudity in Denmark. My interest comes from a lack of exposure to nudity growing up. Having received a Catholic education from the age of 5 to 18, I was taught to dress modestly and shield my body from the evil

male gaze. Whether I dressed modestly outside of wearing my uniform at school was none of their concern, but, inside those eggshell concrete walls, I was a child of God.

We’re sitting at our kitchen table, a simple, cream-colored, five-by-three-foot rectangle with an assortment of miscellaneous chairs surrounding it. A vase of red, blooming tulips sits atop the table as if the flowers themselves are looking forward to listening to our conversation as well.

“Denmark is full of sex-positive policies and locker rooms swelling with naked Danes. It’s something we are very proud

of here.” Signe always talks as though she is delivering a speech to Congress; sometimes it makes me feel like I’m in trouble. She takes a swig from her glass of water that she has just poured from her repurposed kombucha bottle before continuing. “A few summers ago, I took an art class that was centered around drawing an accurate portrait of the naked human body. In order to do so, you need a subject who exudes enough confidence to sit for hours on end while a dozen young adults sit in a circle trying their best to replicate what they see.” I give her a nod to let her know she can continue. “It wasn’t weird or embarrassing or funny. This was his job. He walked into the studio already naked, no robe or towel covering his genitals. He entered the room like that was what he was born to do. And, even with nudity being so accepted here, of course there were a few heads that turned out of habit from seeing a naked body, but they quickly returned to setting up their art supplies.” She laughed at my open jaw. Signe’s laugh is one of force and confidence. It’s hearty. When she laughs it makes me laugh. I’m glad I can be a source of comedy for her. She continues telling her story before I have the chance to interrupt.

“And he went and started talking to the teacher as if he wasn’t naked, because to him it felt the same as being fully clothed. He then walked around and introduced himself to all of the students, which seemed to put the class more at ease. He was displaying to us that he was comfortable being naked in a room full of strangers, so we should feel comfortable enough to draw him.” Her eyes become bigger with every word, which signals to me that she is truly passionate about this topic. “Anyway, all this is to say that seeing breasts or even the entirety of a naked woman’s body in the gym locker room is more than normal. And you should feel comfortable enough to do the same if it is what you wish.”

She finishes her water and sets the empty bottle back on

our stainless-steel countertop. She asks if I have any more questions and, when I tell her I don’t, she looks satisfied. I thank her for explaining a little slice of Danish culture to me and she responds with her signature, “No problem, I was happy to help,” before walking back to her room, the sound of her house shoes sweeping across our floor.

About a week goes by and I’m still taking into consideration what Signe has said about nudity, considering I experience it nearly every day in the locker room. One day, I get back and shower off before plopping down on my bed when my American DIS roommate says, “How about we go to Malmö for a day this weekend?” Malmö! Practically the Copenhagen of Sweden. “Oh, I’m down!” Melina is about five-foot-three, was adopted from China, and has pitch black hair that almost reaches the small of her back. We were chosen to be roommates at random so I am thankful that we get along. “Great, I’ll book our train tickets now.”

Our other DIS flatmate, Justin, who is doing the year-long program and has already been to Malmö a handful of times, hears us talking about it. “Malmö!” he says, “Are you guys going to go to the nude, open-air baths?” Again with this normalization of nudity! Melina and I glance at each other before signaling him to go on. “Yeah, you pay around 20 USD and can stay for as long as you want. You cold plunge into the ocean and then scurry up the ladder and into the sauna. It’s a temperature shock for your body; it’s supposed to be good for you,” he shrugs. My interest is piqued!

“Just how nude is this nude sauna?” I ask him. It should be self-explanatory, but I have to make sure.

“It’s pretty nude,” he says. “You can rent a towel though to make you feel more comfortable if you want.” We thank him and he gives us a curt nod before continuing to his room. If Justin can go in a nude sauna, then surely Melina and I can.

We take the train to the bus stop and then the bus to the open-air baths. The ocean air is brisk against our cheeks as we make our way into the building, the water misting our faces. We each rent a towel because, while we are confident in our bodies, we are not entirely confident in the situation. They separate the baths by gender, so we mosey our way over to the women’s section. As soon as we open the door, we see fully naked bodies. It’s boobs all over again. We realize that this is what we signed up for, and, even though we just met each other a couple weeks ago, Melina and I are about to know each other a whole lot better.

Our day in Malmö in the open-air baths is amazing and eyeopening. No one cares that anyone else is naked - quite the contrary, it is welcomed and accepted. It is liberating and refreshing to have my body seen as just a body and not an oversexualized object, even if it is just for a couple hours. On the train home, I think about how excited I am to tell

Signe about my naked adventure!

I summon Signe from her room and have her sit at our dining room table as I did a week ago. She says that she’s proud of me for fully immersing myself in this part of not just Danish culture but Scandinavian culture as a whole. I thank her and explain that I wish nudity was accepted like this in the States as it made me feel so happy and free. I continue to sit at our table for a couple minutes after our conversation with my feet propped up on one of our royal blue, acrylic dining chairs. I toy with the stems of the tulips, their quiet presence grounding me as I reflect on our first and second conversations about nudity. Each time I stepped into the sweltering Fitness X gym locker room, confronted by the unapologetic abundance of naked bodies, I felt a jolt of discomfort that slowly gave way to curiosity. In time, what once unsettled me began to inspire a growing appreciation for the nude form and the way it seamlessly fit into Danish culture, challenging my own assumptions and reshaping my perspective.

- Sydney Herbruck

In London, bridges don’t just span the River Thames, they connect eras, neighborhoods, and the lives of those who cross them. During my year abroad, these crossings mark my experience, each bridge offering a glimpse into the story of modern London and my place within it.

I start near Westminster Bridge, where the Houses of Parliament loom like a history book etched in stone. Walking across it for the first time, I feel the weight of London’s grandeur and its contradictions: a city at once steeped in tradition and restless with change. Below,

riverboats churn through the waters, carrying tourists and commuters - parallel lives flowing along the same current. It is here I learn that being in London means being both an observer and a participant.

Next come the Hungerford and Golden Jubilee Bridges, twin walkways flanking the old railway bridge. These sleek pedestrian paths feel like a gesture toward the city’s modernity, their white suspension cables soaring upward in contrast to the stately grey of Victorian iron. Before crossing here at sunset, most likely on my way to watch another play at nearby Trafalgar Theatre, I linger to watch the South Bank come alive with street performers, food stalls, and laughter. These bridges teach me about London’s vitality, its refusal to stand still.

Waterloo Bridge, though, has become the centerpiece of my daily routine. Living in the bustling neighborhood of Waterloo - a mix of artsy cafés and pubs, independent bookstores, and the ever-present hum of trains from the station - I feel the energy of a city constantly on the move. It’s a place where locals greet you at the winter market stalls and tourists pause to take in the London Eye, and yet it feels like home. It is home.

Each morning, I cross Waterloo Bridge on my way to the Strand campus of King’s College London, the city unfolding in layers before me. To the east, the glittering skyscrapers of the City; to the north, the neoclassical grace of Somerset House. The walk offers a moment of clarity, a pause to think about the day ahead. In the evenings, steps retraced, the bridge is now a quieter place, its lamplights reflecting off the river. Sometimes, I stop halfway to breathe in the cool air and ponder the confluence of favor and fortune that has placed me here.

The bridge itself is unassuming, its clean lines and gray

Waterloo Bridge, London, England [Tinashe Manguwa]

stone standing in contrast to the ornate grandeur of others. But its story, a wartime bridge largely built by women, gives it a quiet power. Crossing it daily, I find myself connected not only to my present but to the countless others who have walked its span, each carrying their own stories.

Blackfriars Bridge, with its distinctive red pillars, is both industrial and poetic, a nod to Victorian engineering and the pulse of the iconic railway station that straddles it. Here, I find myself thinking again about movement - of people, ideas, goods - and how London thrives because of its ability to adapt. Beneath the bridge, the Thames mirrors the city’s churn, its waters alive with commerce and creativity.

Millennium Bridge is a study in contrasts: London at its most dazzlingly dichotomous. Dubbed the “Wobbly Bridge” after its infamous debut, it ties together the spiritual heft of St. Paul’s Cathedral with the artistic rebellion of the Tate Modern. I love this bridge for its symbolism: the sacred and the secular, history and innovation, all meeting on the thin spine of modern design. I cross it on Thursday afternoons after the Eucharist service, leaving the imposing dome of St. Paul’s to lose myself in the abstract worlds of the Tate. It is here that I learn to embrace the contradictions within myself, as London does so effortlessly.

Southwark Bridge is often overlooked, but I find solace in its quiet greens and golds, as it stands as a reminder that not everything in London needs to be a spectacle. It becomes my go-to route when I need a stillness I cannot source elsewhere, or to visit a friend who lives in that part of Bankside. It is a place where I can walk without crowds and think about the crossings I am making in my own life, between home and abroad, certainty and discovery.

London Bridge holds a charm of its own. It’s less about impression and more about utility, bustling with the energy of people on the move. It becomes the gateway to Borough Market, where I meet some companions for fresh pastries or artisanal coffee. Just after the Tube station exit by the Shard, I discover a shop selling biltong, a taste of home in a foreign city, and the bridge becomes a bridge in more than one sense: a crossing between continents, between my present and my memories. Standing on London Bridge, I often marvel at its layered history, from Viking invasions to its modern role as the city’s lifeblood. Its understated presence reminds me that not all connections need to shout their significance.

Finally, Tower Bridge. Another masterpiece of Victorian ambition, it feels like both the climax and conclusion of many of my riverside walks. Its Gothic towers and modern bascules feel like a fitting metaphor for London: a city forever looking forward while holding fast to its past. At night, lit up against the dark river, Tower Bridge becomes a beacon, a reminder that bridges are more than structures. They are stories, shaped by those who build and cross them.

London’s bridges tell me that this is not merely a city of monuments but a living organism where history, culture, and individual stories coalesce - a city constantly in flux, just like those who inhabit it, even briefly.

- Tinashe Manguwa

Tower Bridge, London, England [Tinashe Manguwa]

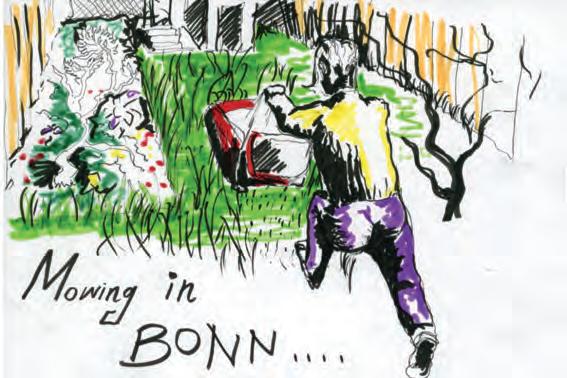

As the spring break commenced this week, marking a pause in my studies in Berlin, I decided to travel to Bonn and visit the deutsch part of my family. As I reflect on my week, this experience was essential for me to understand the comparison between Pakistan (my homeland) and Germany.

When the train rolled into Bonn, I found myself reflecting on the stark differences between this German city and the vibrant metropolis of Berlin where I had been studying and immersing myself in its rich cultural tapestry. I had previously explored that city’s dynamic energy and diversity, contrasting it with the romanticism and surveillance I experienced in Paris. Berlin, with its vibrant arts scene, eclectic neighborhoods, and inclusive atmosphere, had captured my heart in a way that Paris, despite its undeniable charm, could not replicate. The sense of community and acceptance that permeated Berlin’s streets made me feel at home, whereas Paris left

me longing for the freedom and inclusivity I had come to cherish. My experiences in both places had provided me with valuable insights into the unique characteristics of European cities, and Bonn offered yet another perspective of urban life in Germany.

As I stepped off the train in Bonn, I couldn’t help but notice the stark differences between this calm city and the busy streets of Berlin. Bonn’s serene atmosphere and slower pace of life stood in contrast to the hustle and bustle of Berlin, where life seemed to pulse through the city’s veins at every corner. The streets here were quieter, and there was a sense of tranquility that filled the city. Unlike Berlin, whose vibrant artistic environments and neighborhoods were a testament to the city’s diversity, Bonn’s cultural landscape felt more subdued and traditional.

My visit to Bonn held a special significance beyond just exploring the western parts of Germany. It was an opportunity to deepen my connection with my German family, an aspect of my identity that is often overshadowed by my Pakistani heritage. Meeting my German cousin in Bonn allowed me to bridge the gap between these two

facets of my identity and explore the cultural nuances that define both.

Being from Pakistan, a country with its own rich cultural heritage, I was keen to understand how my German family’s traditions and customs differed from my own. Spending time with my cousin provided a window into the intricacies of German family life, from the importance of punctuality and orderliness to the cherished family traditions passed down through generations.

Through conversations with my cousin and other family members, I gained valuable insights into our shared ancestry and familial connections. Stories of our family history shed light on the cultural tapestry that binds us together, despite our geographic and cultural differences.

I was also able to meet my cousin’s friends here, which provided me with another challenge: trying to understand the Kӧlsch/Bӧnnsch accent. As we engaged in conversations, I found myself challenged by the unfamiliar cadence and pronunciation of their accent. The melodic rhythm and distinctive intonation added a layer of complexity to our interactions, requiring me to listen attentively and adapt my own speech patterns to better understand and communicate with them.

Despite the initial challenge, meeting my cousin’s friends provided me with a valuable opportunity to expand my linguistic repertoire and deepen my appreciation for the diversity of dialects within Germany. Through patient listening and active engagement in conversations, I gradually began to decipher the intricacies of the Kӧlsch/ Bӧnnsch accent, gaining insights into the local culture and forging connections with new acquaintances along the way.

Moreover, navigating conversations in this accent offered

a fascinating contrast to my experiences with the Berliner dialect. While both share similarities as regional variants of the German language, each possesses its own unique vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation quirks that reflect the distinct cultural and historical influences of their respective regions.

Growing up in Pakistan, I had always been immersed in the rich tapestry of Pakistani culture, with its vibrant traditions, familial bonds, and community values. Studying in America had exposed me to a melting pot of cultures and perspectives, broadening my understanding of diversity and challenging my preconceived notions about identity. This trip led to an important realization; a new awareness mostly prompted by my introduction to my German family in Bonn.

Meeting them added yet another layer to my understanding of cultural identity. Here, in the heart of Germany, I found myself navigating the complexities of cultural exchange

and adaptation. From trying to understand the Kӧlsch/ Bӧnnsch accent to immersing myself in the local customs and traditions, I was confronted with the multifaceted nature of identity and the ways in which it is shaped by our experiences and interactions with others.

Through these experiences, I came to realize that cultural identity is not fixed or static but rather fluid and dynamic, shaped by a myriad of factors including heritage, upbringing, and personal experiences. As a Pakistani studying in America, I occupy a unique position at the intersection of multiple cultures, each contributing to my sense of self in different ways.

Moreover, my interactions with my German family highlighted the importance of empathy, understanding, and mutual respect in bridging cultural divides and forging meaningful connections with others. Despite our cultural differences, we found common ground in our shared experiences as individuals navigating the complexities of identity and belonging in a globalized world.

- Ali Muzaffar

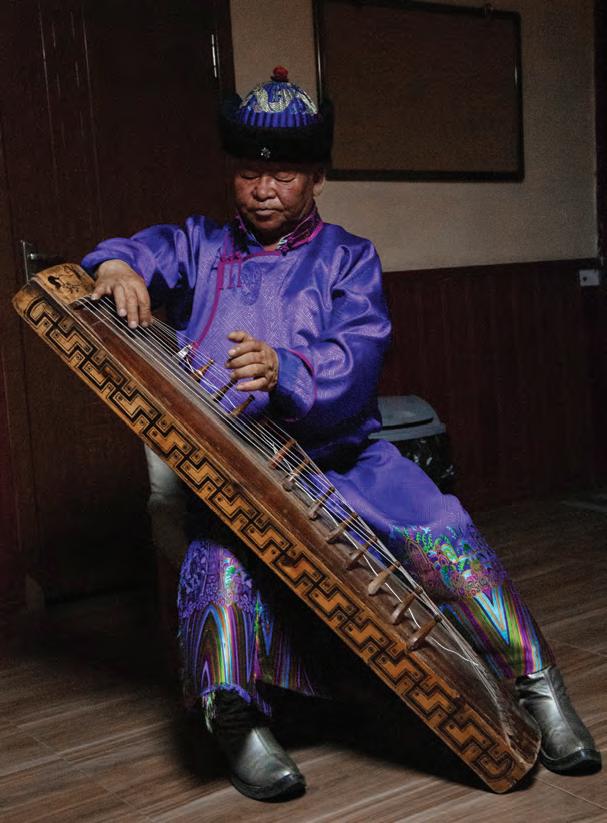

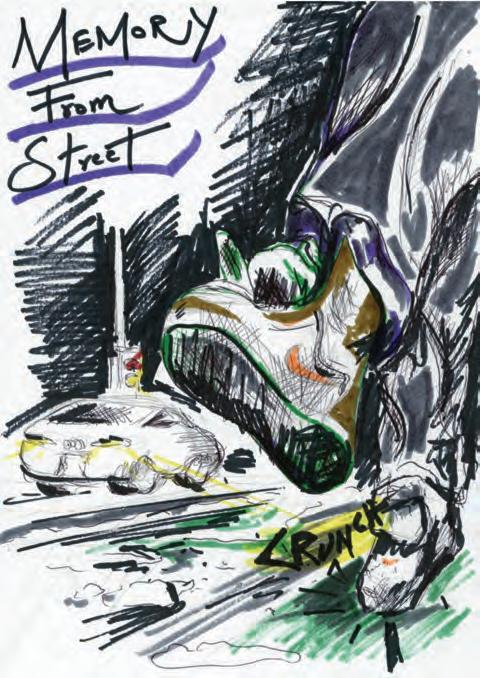

My artist book, titled Erinnerungswelt (Memory World) is a personal narrative capturing my experiences studying in Germany with a focus on Berlin. Through a series of drawings created from memory, I aim to explore the essence of human experience through the emotional resonance of urban life. The central theme revolves around the idea of preserving the unfiltered transfer of impressions. Each drawing is rendered with graffiti-like pure strokes using primarily pens and markers. By working from memory, I seek to capture the immediacy and authenticity of my impressions, free from the constraints of external reference or premeditated composition. From bustling street scenes to quiet moments of contemplation, each image encapsulates a fleeting moment in time, a marriage of personal context and emotional relativism.

- Ali Muzaffar

n. 1. a thing learned by experience

2. an occurrence that reveals, warns, or enlightens

Post-Rain Glow of the Amsterdam Canals, Netherlands [Rachel Brooks]

I learned countless lessons during my spring break girls’ trip to the quiet Menorca, an island tucked away off the coast of Spain. While many know Mallorca’s vibrant bustle, only the fortunate few discover the peaceful charm of the smaller Menorca - and I was lucky enough to be one of them. When we arrived, the airport felt like a distant memory of life in fast motion - empty and still. We followed signs to arrivals, naively expecting the usual modes of transportation - an Uber, a metro, a bus - but the island offered no such conveniences. No rush of cars, no noise of a busy city, just quiet.

Lesson #1: Always plan your transportation ahead of time when arriving in a new country.

With no choice but to walk, we began our journey toward the Airbnb we had booked. The island’s beauty was impossible to ignore - the soft sunset reflecting over every corner and the empty streets lined with massive trees felt like an abandoned fairytale setting. But, when we arrived at Suite 4B, the beauty quickly gave way to confusion. The apartment seemed abandoned, with no electricity or furniture, and, in an instant, panic began to creep in. Immediately, I thought of the next six days, stranded, left to wander the island with nowhere to stay.

Lesson #2: Try not to immediately assume the worst.

A quick phone call to our host eased the tension - turns out, we had been sent to the wrong address. Hunger set in quickly, and our search for food already felt like a challenge. The streets were quiet, and, as we checked Google Maps, we found that most restaurants were closed. It was only 7pm, yet the world around us felt like it was shutting down. By chance, we discovered a small grocery store open down the road and began our trek.

Lesson #3: Always bring a pair of comfortable sneakers when traveling.

Upon arrival, the kind storekeeper explained something unexpected: Menorca was in its off-season. What was usually a lively tourist haven in summer had slowed to a tranquil retreat for locals in spring.

Lesson #4: Sometimes, the world moves slower than we expect, and that’s okay.

The following morning, I felt a quiet excitement as I prepared to explore the stunning island. A soft knock interrupted my thoughts - Yan, who I learned was the maintenance man, introduced himself with a warm smile. At first, my American instinct was to be cautious, but it didn’t take long to see that Yan was no one to fear. He was kind, thoughtful, and eager to share his knowledge of the island with us.

Lesson #5: Keep an open mind when meeting new people.

Following his advice, we ventured to a nearby beach, a hidden gem that required a bit of effort to find. After climbing down four flights of stairs, we reached the bottom and were greeted by the sight of the most pristine beach I had ever laid eyes on - crystal-clear waters, soft sand, and

white houses nestled against the cliffs like a dream.

Lesson #6: The best things in life often require effort, but they are always worth it.

As the days passed, the island’s rhythm became my own. I found myself walking slowly through the streets, taking time to appreciate the quiet beauty of Menorca. The one coffee shop didn’t open until 10am, and the only restaurant closed by 7pm, which seemed strange at first. Quickly, it became clear that this was the island’s speed - slow, deliberate, and gentle. We spent our days wandering across fields of flowers and gazing at cliffs that seemed to stretch into eternity. Each corner of the island offered something even more beautiful than the last, from the delicate petals of wildflowers to the intricate patterns of the rocks.

Lesson #7: Life’s most beautiful moments often happen when we allow ourselves the space to see them.

Mirador del Mediterrani, Menorca, Spain [Brooke Prochniak]

On the beach, time seemed to slow down even more. I would lie in the sun for hours, listening to the waves crash gently on the shore, my breath in sync with the rhythm of the ocean. There was no rush, no pressure to do anything other than simply be. The days unfolded lazily: home-cooked meals, laughter that filled the air, card games that lasted into the night, and deep conversations with friends.

Lesson #8: Sometimes, the most meaningful connections are made when we have nothing else to do but be present.

When our last day arrived, Yan, now a familiar and friendly face, drove us to the airport. The 10-minute car ride felt like a quiet reflection on the past few days - everything that had unfolded and the lessons that had come with it. Yan blessed us with his wisdom that stemmed from his eventful life.

Lesson #9: Community is key.

Lesson #10: Be adaptable.

Lesson #11: Call your mom.

Lesson #12: Don’t eat white berries off of a plant.