Welcome to Hurricane

Twelve miles off the coast of Maine lies a magical island waiting to be discovered.

Upon his arrival at Arches National Monument in the late 1950s, the late great cantankerous writer and naturalist Edward Abbey wrote: “This is the most beautiful place on earth. There are many such places. Every man, every woman, carries in heart and mind the image of the ideal place, the right place, the one true home, known or unknown, actual or visionary.”

Twelve miles off the coast of Rockland, Maine, sits another one of those right, true places. It’s called Hurricane Island.

For more than forty years, the remote outpost was home to the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School (HIOBS), known for its rock climbing, ropes course, sailing, and pulling boat programs. In 2006, Outward Bound moved inland, and in 2009, the Hurricane Island Center for Science & Leadership was established by Peter and Ben Willauer with the help of several former HIOBS instructors.

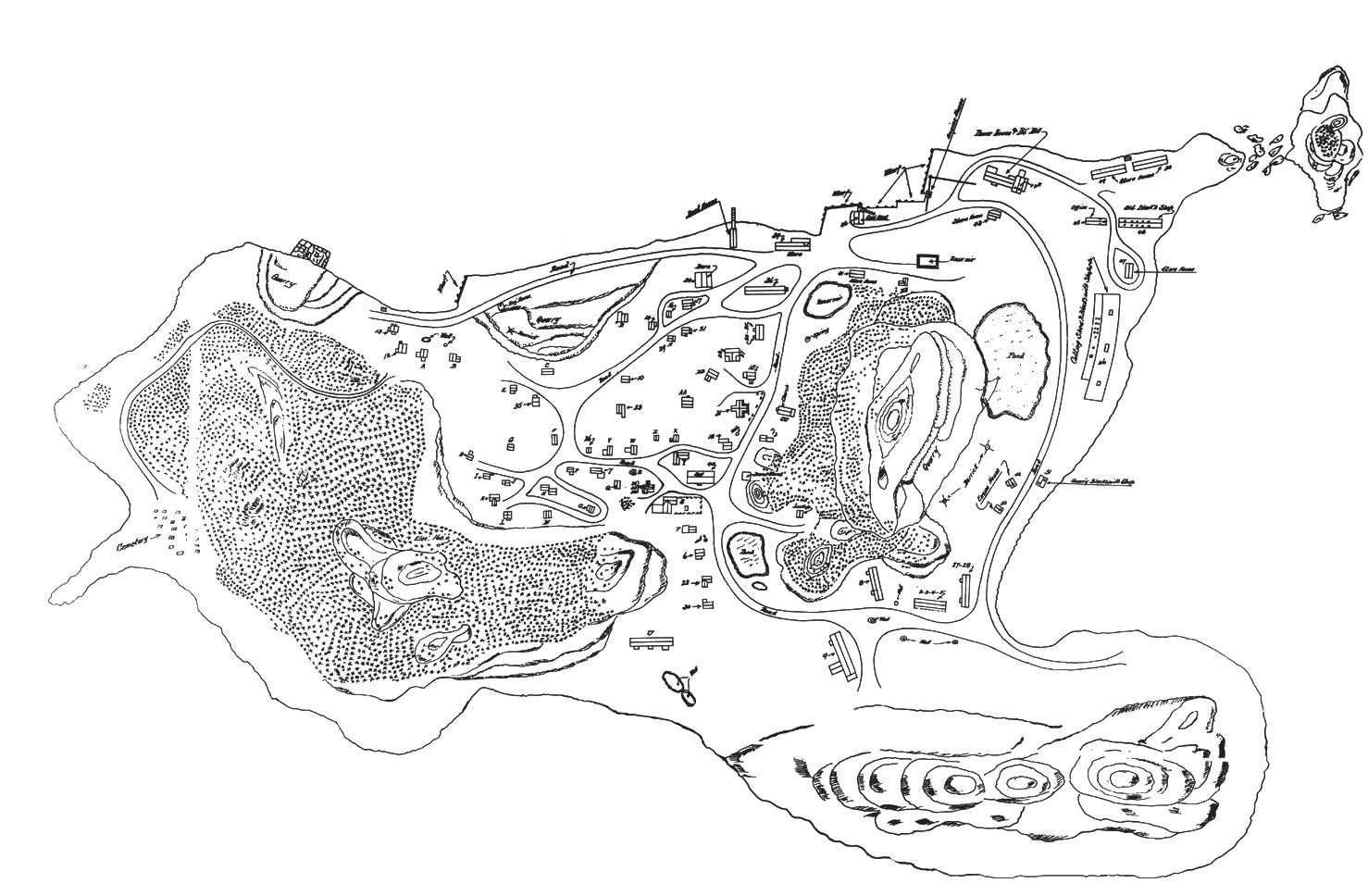

S ince 2018, small groups of Pomfret students have been coming to this low-lying granite outcropping dotted by spruce and fir to immerse themselves in a course called Marine Ecology and Climate Change on the Maine Seacoast. Measuring a mere 125 acres, the

island is one of more than 200 small privately-held islands dotting Penobscot Bay. “Hurricane Island is an ideal learning laboratory for Pomfret students and educators,” says Associate Head of School Don Gibbs, who leads and manages the program.

Gibbs is no str anger to experiential education. During his twenty-plus years at Pomfret, he has traveled with students to study geology in Hawaii, Islam in Morocco, colonization in the Sacred Valley of Peru, and biogeography in the Galápagos.

On Hurr icane, part of the Fox Island archipelago, budding marine scientists get the opportunity to learn the tools of the trade directly from a team of professional educators, trained biologists, visiting scientists, and guest lecturers. The course is for credit and counts toward the pursuit of a certificate in STEM or Sustainability. Our certificate program gives motivated, independentminded students the opportunity to gain deep exposure to a specific area of study during their time at Pomfret. Certificates are diploma distinctions that appear on a student’s transcript.

‘‘I was interested in a carnivorous gastropod called a dog whelk. An abundance or deficit of a single species can have such a big impact on the ecosystem.”

— Owen Schmidt ’26

O ver ten days, students working in small teams live and work here, learning key measurement and core sampling techniques used by the island’s resident researchers to assess the health of the marine environment. In the process, these student-researchers come to understand the ecological and economic impact that climate-related changes are having on local and regional communities in the Northeast.

On his tr ip to Hurricane, Edward King’oo ’26 studied the effects of energy intensity on intertidal species density. “Many species — including crabs, clams, and other marine invertebrates — live in the intertidal zone. I was able to show how different energy levels created by wind, tide, and waves impact where they choose to live within that zone.”

Hurr icane Island is the linchpin in a network of ocean monitoring stations called the Northeast Coastal Stations Alliance (NeCSA), which was formed to investigate and document coastal change in the Gulf of Maine. The Gulf of Maine is one of the fastest-warming bodies in the world, warming faster than 99 percent of all other marine waters on the planet. The implications for biological communities, ecosystem services, and coastal cities and towns are significant and still largely unknown.

“ I was interested in a carnivorous gastropod called a dog whelk,” says Owen Schmidt ’26. “An abundance or deficit of a single species can have such a big impact on the ecosystem. In my research, I learned that an abundance of dog whelks

often leads to a decline in the mussel population.”

S tudying (and eating!) shellfish is an important part of the Hurricane Island experience. To the north of the island, the Center maintains a three-acre aquaculture farm where students spend time exploring scallop beds and other multitrophic research projects. The work is funded through the Maine Department of Marine Resources’ Maine Sea Grant Program Development, and the goal of the initiative is to understand how local populations respond to rotational management efforts.

“ The whole student experience culminates with a marine ecology symposium in which students describe the scope and methodology of their studies and share the results,” says Gibbs. “When students return to Pomfret, they host an information session for other students who are curious about the experience.”

The beating hear t of Hurricane Island is the central campus, a spartan collection of sturdy, utilitarian buildings that include five cabins, one bunkhouse, a yurt, a full-service kitchen, a mess hall, composting toilets, a shower house, a flowing-seawater lab, a dock, two classroom spaces, and a new, sustainably-built field research station. Electricity is generated by solar arrays, and hot water is warmed with solar heaters.

This June, Pomfret’s island roots got a little deeper when it launched a new credit-bearing experience focused on the campus itself. The Certificate Program in Sustainability

Leadership is a week-long intensive course open to high school students from across the country and the world. The program is accredited by Pomfret School and taught by the Center for Science & Leadership’s resident researchers.

Using the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals as a framework, program participants monitor the Center’s electric and water usage, maintain the compost, and help keep the galley clean; they interact with research scientists and sustainability professionals; they consider new ways to improve the island community’s commitment to sustainability; and they determine how these innovations can be applied back home. “It exposes students to emerging technologies and solutions that hold promise, need investment, and could be implemented at various scales,” says Gibbs.

S tudents enrolled in the program also become part of the

team that makes the island tick. “On the island, wastewater from the bathrooms is filtered through plants and then used to water the vegetable garden,” says Nyx McIvor ’27, who studied on Hurricane Island last summer and is headed back again this August. “It taught me to be more mindful. Maybe I don’t need to take a hot shower for half an hour? Maybe I just need to have a quick rinse and come out.”

Of course, the Hurricane Island experience isn’t all work and no play. For many students, what they remember most, what tends to burrow deep down inside of them, is the way the island makes them feel.

“ The island — its atmosphere and scenery — are magical,” says Nyx. “Just the opportunity to escape technology and be immersed in nature is amazing. I really loved walking around the island during the day. But, for me, what I’ll never forget are the stars at night. Hurricane Island is just an incredibly special place.”

“The island — its atmosphere and scenery — are magical. Just the opportunity to escape technology and be immersed in nature is amazing. Hurricane Island is just an incredibly special place.”

— Nyx McIvor ’27