7 minute read

Understatement

By Betty Mills

At a national convention workshop I attended, we were divided into pairs and instructed to draw a floor plan of a house we had lived in before we were nine years old. That barely required squandering any brain energy, since I lived in the same house for the first twenty-one years of my life and could have drawn in the worn spots on the linoleum.

Advertisement

My partner for this exercise, however, drew a small room, a hall leading to the back door, and a pear tree. We were both astounded.

He explained that during World War II his parents followed the lucrative job market, usually leaving him with some relative. His favorite was his grandfather, a widower, who was a barber in Chicago. He lived in a house across the alley from the shop where the boy spent much of his time—escaping his bedroom out the back door, past the pear tree, and into the shop.

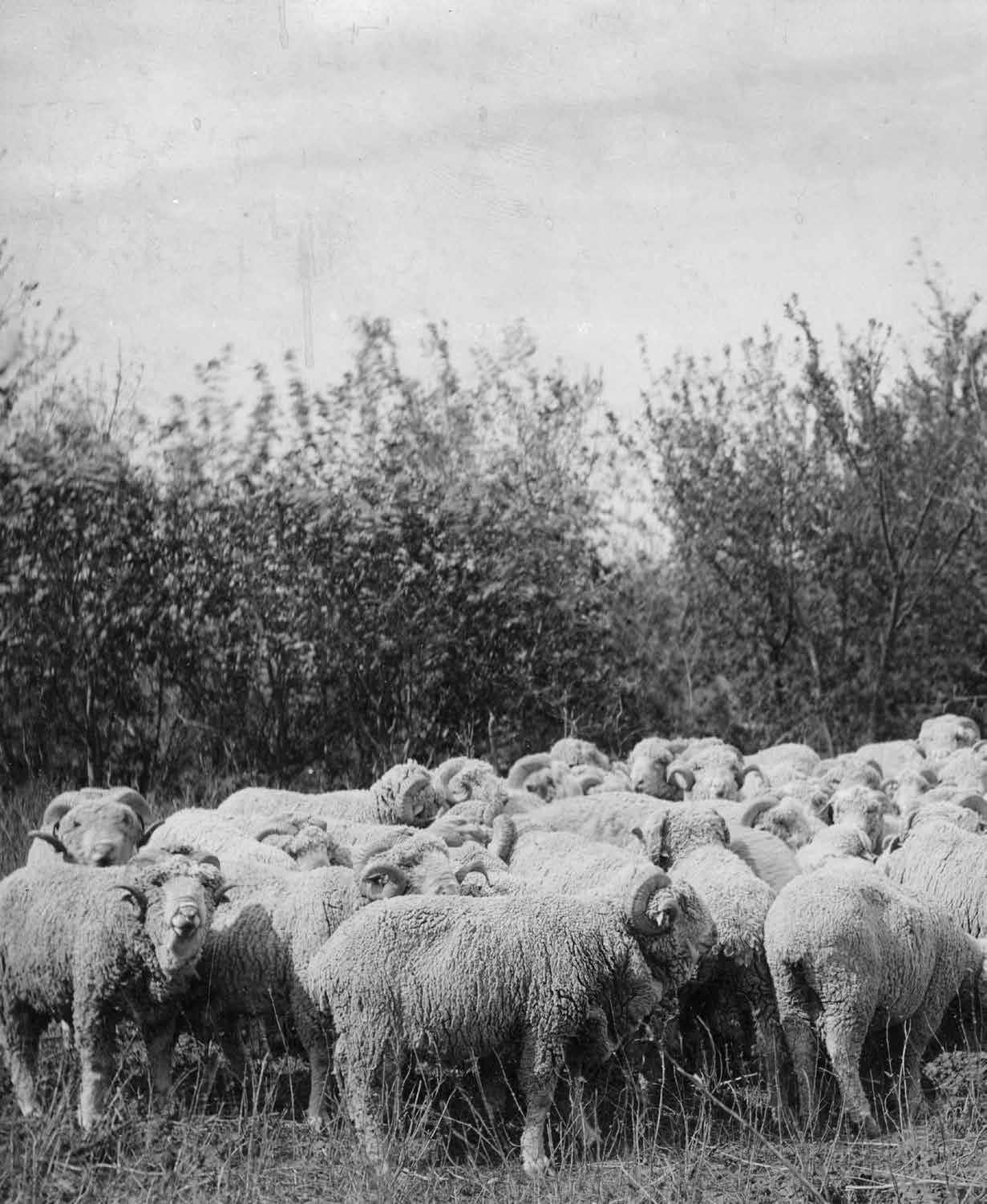

If I was intrigued by so nomadic a life at such a young age, he was equally fascinated by my life on a small sheep ranch on the western North Dakota prairie, and particularly with the thought that one or both of my parents were always around. It is still hard for me to really imagine his childhood.

His barbershop childhood had obviously not curdled his life. He was a handsome man in his late thirties, wearing a white sports jacket and sharply creased trousers, his shoes shined. A college graduate with a family and a job in the finance industry somewhere in Indiana, he was exuberant and interested in everything.

What makes his upbringing seem especially meager to me, however, is the alley and the pear tree—no knee-high prairie grass blowing in the wind, no towering elm trees to climb, no garden to plant, vegetables to water, pet lambs to feed, or flowers to pick to prove spring has really happened.

Perhaps the phrase that covers this difference is something called a “sense of place,” defined by one dictionary as “either the intrinsic character of a place, or the meaning people give it, but, more often, a mixture of both.” Who am I to judge a pear tree and an alley, and maybe for that man the barber shop still sticks in his memory as a milestone.

Or maybe the real significance of his childhood experience was shown in his particular interest in the fact that my parents were always present in my young life. So the question then becomes the range of difference in people’s perception of what they consider their own sense of place.

Ask anyone what feels like home to them and after you get past the easy chair and the smell of coffee for breakfast, their answers can be intriguing. My youngest daughter, who has lived all her adult life in the San Jose area of California, comes home in part just to be here, in North Dakota. Driving out in the country, exclaiming over the distant hills, the clouds stretched across the clear blue sky, the state of the crops in the fields as we pass, the occasional hawk sitting on a fence post unperturbed by our passing, she is clearly in love with the view.

She has now added a new image to her repertoire. “Climb the Capitol steps,” she says. “Sit down and take in the magnificent view stretching over to the distant hills. It’s wonderful!”

“Mom,” she explains, “I need this—this coming back to North Dakota. It’s like recharging my batteries. It’s how I remember who I am.”

A friend describes how, after many moves and some personal dislocation, she arrived at the farm that would become her home for many years.

“You grew up on a farm—did it remind you of home?” I ask.

“No,” she replies. “Not at all. I can’t even explain it, except even now when I’m gone and return from wherever I’ve been, that same sense of calm runs through me—the thought that at this place, here, these trees, these hills, this is my peaceful world.”

My son left home, left snow country, after high school, living in urban areas on the West Coast. He only recently moved to eastern Wyoming, some forty years later. His favorite time there is a winter night, in the silent darkness, snow on the ground, brilliant stars visible in the sky, the snow squeaking under his feet.

“You’re describing North Dakota,” I point out, and he agrees that he has come home—that the snow and stars and squeaky footsteps constitute a special place for his sense of wellbeing.

For many years there was a big old cottonwood tree I could see from my kitchen window—watch it leaf out, grow green, turn yellow, be bare again. When my life grew sudden ragged edges as all lives sometimes do, I focused on that big old cottonwood, a form of visual meditation perhaps. I let it take me back to my childhood when all was safe and serene, when the biggest excitement of summer was a chance to swim in the Heart River and cool off under the giant cottonwoods that fringed the river on my great uncle’s ranch.

I worked on my dad’s threshing crew during World War II, a wonderfully joyful experience for me—outdoors, good food, a useful life, and the constant company of my father. So I don’t like those derelict threshing machines stationed on hills adjacent to the highway, reminding me sadly of a vanished prairie life that I once so cherished.

Perhaps that is the essence of a sense of place, however: that spot in our memory, or if we’re lucky, right where we are, where our lives assume a coherent pattern, where the world makes sense or is, at the least, manageable—a halt in time where we can recapture some of the essence of how we became who we are, however far removed from that geography where we at the moment reside.

My mother, who grew up in the leafy green world of Minnesota lake country and then married a rancher in tree-scarce North Dakota, said that had we not lived in a little green valley shielded from North Dakota’s ever-present winds and from the terrible dust storms of the Dirty Thirties, she was not sure she could have survived.

In retrospect, my parents were always working on turning our yard into a small green paradise, perhaps reminiscent of my mother’s childhood terrain.

On the reverse side of that environmental coin, there are people who grow up in big cities, for whom the tall buildings, the busy streets, the noise of traffic, are part of a familiar world, and the big open space of North Dakota’s prairies is rather unnerving. Give them concrete under their feet, and they are at ease.

Sadly, there are many people for whom memory is all they have left of what once formed the essentials of their lives. Think of the current refugees who leave everything and come to a strange new country where even the language is a barrier. Gone is all familiar geography, all memory invoking glimpses of a happier world, or at least a world they can recall, that they once called home.

So how, then, do they fashion a sense of place out of this new strange territory when they are so engulfed in simple survival in a very different world? Can they somehow eventually find a substitute for the comfort they once found, some new space with new meaning, bringing with it security and comfort?

How do we arrive at a personal sense of place? Is it somehow bred in our genes, maybe farther down the list from flight or flee, but still innate? Is it something that can be consciously conjured up, more common among some types than others, easier in some geographies, strictly dependent on personal circumstances— or maybe just the result of too much imagination and inner brooding?

Maybe it is better not to nail it down with scientific analysis and precise terminology. That might spoil its magic, which is how I view it in my case. Or maybe it’s the luck of the genetic draw. So when people ask me where I’m from and I reply, “North Dakota is my home,” they have no clue that they have just heard the understatement of a lifetime.

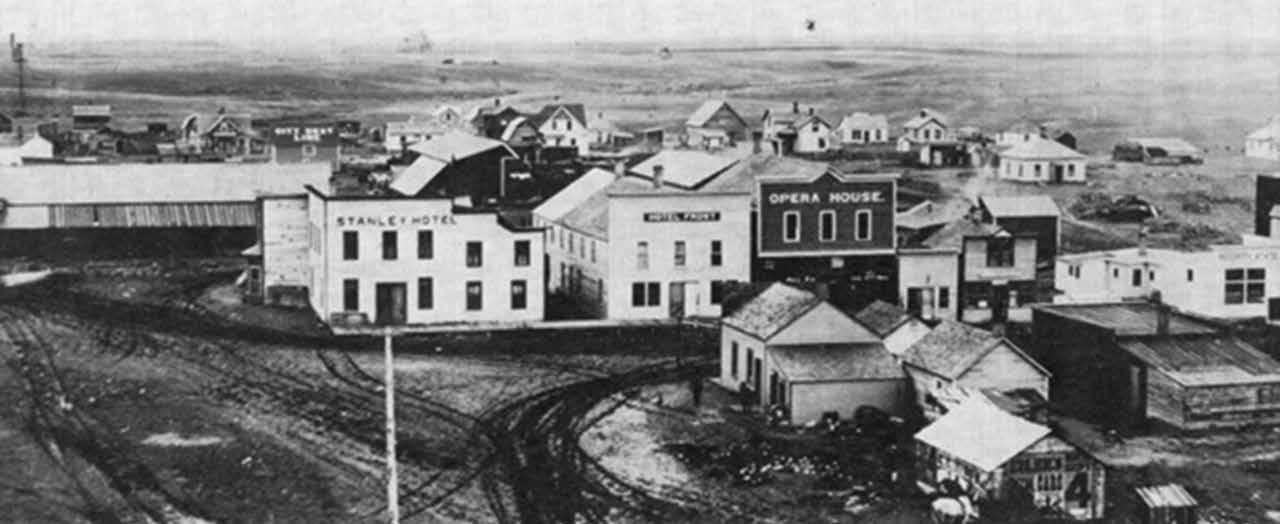

BETTY MILLS is the granddaughter of Charles and Anna Lidstrom, who homesteaded south of Glen Ullin in 1887, when this land was still Dakota Territory. She was born in 1926 to Leonard and Crystal Sletmoen Lidstrom. Tractor driver and rattlesnake hunter, she graduated from Glen Ullin High School in 1944 and Mary College in 1967 with a degree in social work. winter night, in the silent darkness, snow on the ground, brilliant stars visible in the sky, the snow squeaking under his feet.