5 minute read

Cobwebs and Memories

By Gary Hendricks

I’ve been doing some musing lately about things like words and memories, especially memories. Dean Martin even had a song in the 1950s with his recipe for memories called “Memories Are Made of This.”

Advertisement

My aunt Dora knew about memories and dreams.

I was about five years old and going to spend a full day with Dora. My folks dropped me off right after breakfast on a fall morning. (Parents were called “folks” back then, and my sisters and I were “the kids.” That’s more comfortable than parents and children. Now brothers and sisters are called “siblings,” a word that could better be used to describe piglets in the same litter rather than people. Then there’s fall—a four letter word, in my estimation, that can’t stand alone but needs to be propped up by summer on one side and winter on the other. I visualize low, cold, gray clouds spitting sleet and snow and a cold wind scattering dried up leaves across the yard.) Let’s change fall to autumn. Recall Roger Williams at the piano playing “Autumn Leaves”? I’ve never head of a song called fall leaves.

Autumn spawns memories of sunny days, calm wind, colorful leaves hanging on the trees, losing their grip and fluttering to the ground, and merry little breezes now and then from everywhere and nowhere.

On this particularly autumn morning, Dora found two laths. (There’s another word not heard much anymore. Back then, hundreds of laths were used in every house, tacked to the wall and plastered over. They were about four feet long, five-sixteenths-inch thick, and an inch and a quarter wide. Dad insisted that the laths on the wall had to be level and parallel with each other with equal space between them. I said I didn’t see why that was so important, because they were going to be covered with plaster and nobody was going to see them anyway. Dad said that you always do things right whether anybody sees them or not.)

Dora and I each had a lath, and she gave me a fruit jar and said we were going to catch cobwebs and imagine they were dreams and put them in my memory jar.

On that day, cobwebs were drifting in the air, dancing and twisting and undulating in the wisps of breeze. (If you’re still trying to visualize undulating, undulating is to sight what yodeling is to sound.)

(I don’t know why they’re called cobwebs either. I’ve shelled lots of corn and gathered up the cobs to start fire in the cookstove and I’ve never seen one spin a web. I think they’re filaments spun by spiders.)

We started collecting our cobweb “dreams,” and it was harder than it sounds. Sometimes I’d reach up to catch one and the lath would create a slight air movement, and it would drift away. Dora showed me how to use the edge of the lath to move through the air rather than the flat side so they wouldn’t drift away so easily.

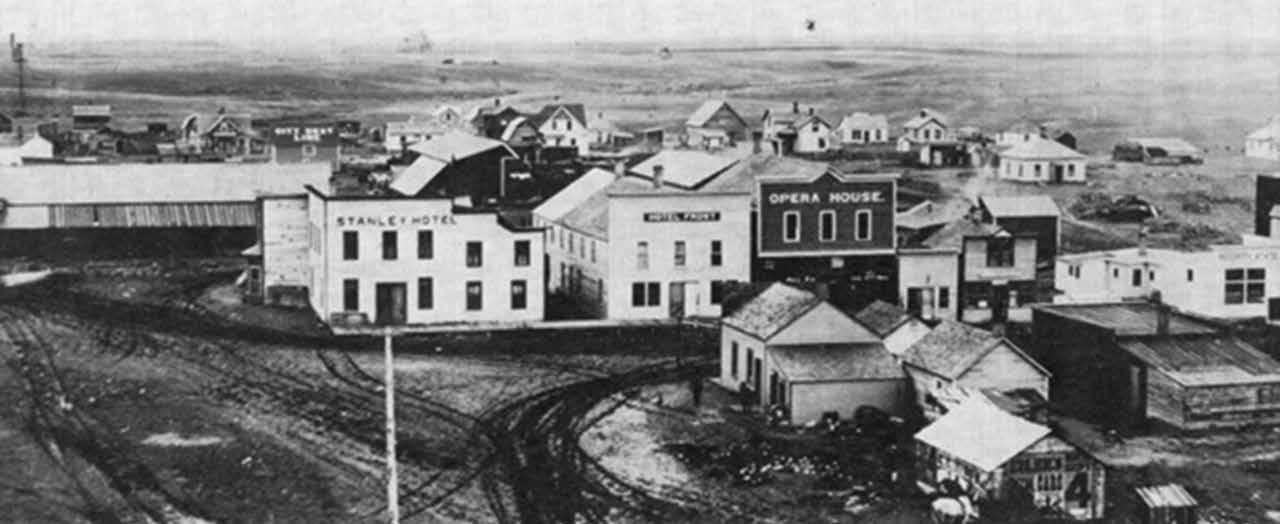

Home of Jake Hermann Sr., Liebenthal, Kansas, Germans from Russia Heritage Collection, NDSU Libraries, Fargo (110.127)

Even then, sometimes one would elude me and just be out of reach even if I stood on my tiptoes. Dora (she was taller than me, you know) would reach up with her lath and catch it and then hand the lath to me. I thought it should go in a jar for her but she said no, she already had a full jar and everybody needed help sometimes to catch their dreams.

Now and then, a whirlwind would form out of nowhere, twisting and spinning and making a commotion through the yard until it lost control of itself, fizzled out, and scattered then, because Dora said it would take a while for the air to settle down.

Dora said people are like whirlwinds sometimes. They sometimes let some little thing become a bee in their bonnet, work themselves into a frazzle, go into a tizzy, spin out of control, lose control and have a blowup, and then it takes time for things to get back to normal. (Fizzled, frazzle, and tizzy. They’re words with sizzle. They’re multidimensional. You can hear them, visualize them in your mind, and feel them. They make your tongue vibrate.)

I like whirlwinds because they meant another of Dora’s cookies. I liked catching dreams but decided I liked Dora’s cookies even better.

We chased the cobweb dreams and put each one we caught in my memory jar. Some we couldn’t catch as they were too high in the air or too elusive. Dora said that was just the way things are. Sometimes we find our dreams are just out of reach, so we just have to look for others to take their place.

When we stopped, we had lots of dreams in my memory jar, and Dora gave me a jar to take home. My dad wondered why the heck I was saving cobwebs, but Mom and Dora just looked at each other and smiled because they knew things about dreams and memories and kids that my dad was too practical to understand.

If all those dreams were going to be memories, I just hoped they wouldn’t be as tangled and twisted up in my brain as they were in the jar.

EPILOGUE

It’s seventy years later. Dora’s gone. The folks are gone. My youth, middle age, and much of my old age are gone. The memories are still here but will disappear with me.

Wait! I’ve forgotten the memory jar. It’s still here . . . on a shelf in the cellar, a pale green quart jar with a glass top held in place with a wire bail.

(Nearly forgetting the memory jar. Is that like suddenly remembering the forgotten jar? I guess I just forgot to remember to remember! Now, I nearly forgot to remember the rest of this story.)

I open the jar lid and peer inside. The jar is empty. The cobwebs have all disappeared into a fine layer of dust on the bottom.

I’ll take a copy of this story and place it in the jar, replace the lid and bail, and put the jar on the kitchen shelf alongside my grandparent’s coffee grinder, Grandpa’s shaving mirror, the churn we used to make butter when I was a kid, and the hurricane lantern used for light when milking cows and to find new lambs and bring them into the barn during long, cold, spring nights.

Someday, after I’m gone, someone will take this jar from the shelf, see the paper inside, and open it to find this story. The memories of Dora and the dreams and the lessons she taught that day will live on.

Since 1973, GARY HENDRICKS and his wife, Laureen, have operated a biological farm near Hettinger, North Dakota, raising sheep and small grains, utilizing crop rotations, cover crops, green manure crops, and rotational grazing. Using a (w)holistic management plan, their goal is building humus and organic matter and balancing soil minerals and nutrients and soil life for a healthy, sustainable future.