10 minute read

Place in Life

By Tayo Basquiat

I am going too fast. The trail of hardened hoof prints jogs left. My front tire spins in the dog day air and plunges into the gully. My bike bucks me over the handlebars. Helmet and right shoulder smash into the earth and instinctually I roll, sending myself over the edge, tumbling like a wind-whipped weed. Fingers fanned like claws loosen scabs of pancaked clay, woody stems, and tufts of grass. The air turns dusty, fills my mouth, tastes like sage and minerals and blood. A thicket of juniper catches me near the bottom. The impact drives the wind from my lungs. I should be still, take stock. Adrenaline and pride force me into a sitting position. No searing pain. Trickles of blood make small rivulets through the dust glued by sweat on my legs and arms. I’ve bitten my tongue. My shirt at the right shoulder is tattered, exposing gashed skin cauterized with trail grit. I pick until the blood is free to run and cleanse; I flick the bloodied sediment to the ground. I am scuffed, humbled, but not broken.

Advertisement

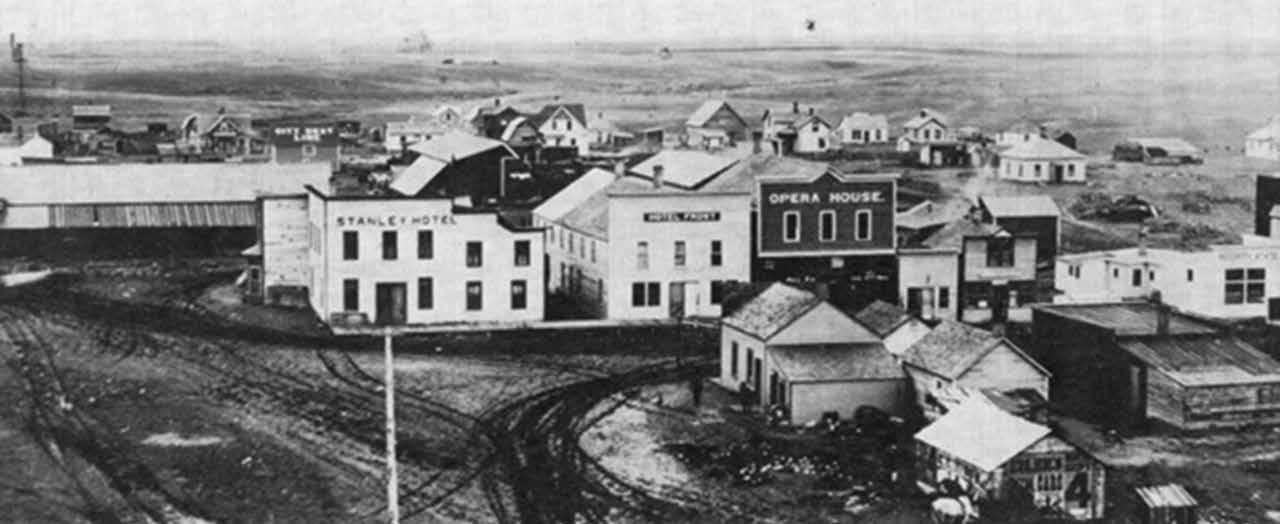

I am a six-year-old on his first horseback trail ride. When my “Whoa, horsey, whoa!” fails to impress horsey as he trods downhill, I bounce down his neck and into the middle of some brush. Mom and the sound of her screaming my name reach me at nearly the same time, grasping for me as I struggle to free myself from the bush’s clutches. I don’t cry until later at the motel, when I see the hole torn in the vest I bought with my saved birthday money in a souvenir shop in Medora. The fabric on the front is supposed to look like deer hide, and a fake coon’s tail is fastened on either side. The back is green felt adorned with an Indian headdress painted in neon colors. I’d somehow managed not to impale myself on the plastic bowie knife or the wooden tomahawk I’d secured in my belt loops. At the time, I didn’t think about anything other than getting back on that horse, and that’s what I did, caught up in something I wouldn’t be able to articulate until much later in life. But it starts on that trip, at my first glimpse of the North Dakota badlands at the Painted Canyon rest stop, a sight that launches a frenzy of nonstop jabbering and proposals.

“I could climb that one and you could pick me up on the other side,” I say, selecting the highest, gnarliest points in the landscape as we round each highway bend before the descent into Medora.

“Those hills are a lot bigger than they seem,” Dad says.

And Mom: “You’d get bit by all the rattlesnakes.”

“I’ll catch one with my bare hands and make it my friend.” I conjure a vision of it riding in the basket of my purple bike with the white banana seat.

“Get off me! You’re on my side of the line,” one sister protests as I press to the window from my prison in the middle of the backseat between two older sisters. The thought of getting loose in the badlands makes me a fidget-bucket. Mom tries to distract me with the suggestion to look for buffalo and wild horses, more oxygen to the fire.

And as I squirm and hop with excitement in the queue area for that trail ride into the most mesmerizing place I’ve ever seen—better than my favorite television show, Grizzly Adams, filled with more possibility than the small woods around the river near my hometown in northeastern North Dakota’s flat squares of farmland—I imagine the moment when I will finally charge up one of the hills, just like Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders had done at the musical the previous night. The place wouldn’t let me have it quite that way though. It enticed me with possibility, kicked me in the teeth, and then taught me I could get back up again.

---

I push myself upright to begin the climb back to the trail, where I find my bike firmly lodged by its pedals in the little ravine. It looks almost as if I parked it there. I read my story in the track of the knobby tires, the broken twigs and leaf litter, the bald slope where the broom of my body swept rock and soil to the bottomlands. Left a mark on each other we have, this place and I, and a deep one at that.

---

This awareness about places dawned slowly. I paid no attention to the idea of place until graduate school in my late twenties. In a class on human geography, the professor’s introductory lecture was basically a series of questions intended to guide our work for the semester. How is a “place” different from a “space”? At what point does a space become a place? What kinds of practices shape places? How do they change? How do places shape people? At first confused by the academic obsession with something seemingly so banal, a creative assignment the second week of the semester awakened my imagination and understanding: map the complexities of a place for a specific point in time, moving through as many conceptual categories as possible. Living in Berkeley, California, at the time, I chose a place in North Dakota, feeling lonesome or nostalgic, I suppose. I called Dad to pinpoint the coordinates, tough given his directions contained no road names or numbers: “Go about four or five miles north, then maybe another mile west until you get to a farmyard, then turn north again.” Such are the recipes and routes of rural America. Like Russian nesting dolls, I included physical features contextualized historically and in relation to surrounding spaces—landscaping by glaciers, inland seas, Lake Agassiz. I provided a political, cultural, and planetary time map related to that specific place, featuring markers from pop music, the price of a bushel of wheat, the record of the UND hockey team, and the phase of the moon.

Then I stumbled warily into the morass of why the place came to mind at all: my memory, of two square bales of straw on a hill overlooking a valley sparsely populated with trees. The land belongs to a farmer my dad knows. It’s November, I’m twelve, and my dad and I are posted up there hunting deer, trying to use the bales against the fierce arctic wind. They aren’t enough. I can’t feel my toes or fingers; the thrill of the hunt is gone, just misery now. I want release, refuge, to turn tail back to the pickup where the heater and a thermos of hot cocoa will make everything okay again, but I don’t because—can this be true?—the suffering pales in comparison to my desire to show my dad I am tough, to not disappoint him.

I bring my maps to class, feeling somehow both wrung out and brimming, completely hooked by the subject and ready to plunge into deeper waters. I started then and there to pay attention to how places were formed and how they formed me. While that little hill in the boonies northwest of the tiny town of Edinburg, North Dakota, may not be special or important for anyone else, it’s a crucible for me, a moment in my progression to manhood and self-understanding that flushes my face with shame, ignites worry over exposure of weakness, and creates an anxious, frantic craving for some place more comfortable, a niggling feeling ever present. I brought everything I was at that time to that place—my whole twelve-year-old self—and I pushed hard against it, tried to make it what I wanted and needed it to be as a proving ground, and it met me head on, revealed my limits, toppled my bravado, shocked and scared me, threatened demise with dangerous cold and unrelenting wind. I kept all my fingers and toes, but now it takes goose down and layers of wool to keep pain at bay on even a mild winter day.

---

According to humanistic geographers like Edward Relph and Yi Fu Tuan, place is much more than a spatial index. Places are something we make, and those places also make us. Places put their prints on bodies and memories, nurturing our sense of who we are and what we are. Our consciousness about this reciprocal relationship is what it means to have a sense of place. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato is often credited with the seeds of this line of thought, infusing one of the Greek words for place chora with the notion of a mothering role, that of “wetnurse, suckler, and feeder of all things.” We are products of our mother’s milk. I think of my mother’s lap, the pillow I made of her soft breasts, the blue veins I traced under the smooth skin of her hands, the smell of her lipstick and Vaseline Intensive Care lotion, a place of comfort and safety. Sometimes I crawled onto her lap just to be there, but other times she gathered me up and cradled me there because I was crying, hungry, needy. I observed a new mother recently, learning to breastfeed, and it was hard on her. The baby had to learn how to latch, and being latched onto hurts.

---

I extract the bike from its earthen stand and walk beside it for a stretch, mustering the courage to get back on—grateful I am not really hurt, that the consequences of my inattention and recklessness in this place weren’t worse. I don’t croon over the unalloyed beauty of a place. My sense of place is far from facile; these beauties have their beastly side. I’ve tried to listen and learn what places want from me, how to care for them and be responsible and ethical toward them. Now I see places as sacred, in the sense Wendell Berry invokes when he says there are only two kinds of places, sacred places and desecrated places, but again, this is complicated. I don’t always want to give what is required. I don’t always want to be where I am and I often want things on my terms. Places push back. Sometimes I stand in the National Grasslands and whisper in awe, “Look at all this wide open space.” Other times I’m beset by a restless loneliness. I can’t leave fast enough. I feel like I’m drowning.

I hop on and start pedaling, feeling the blood pooling in bruises I can’t yet see, the wind cooling my face, concentration replacing fear. Latching on hurts, but it’s what feeds us and makes us grow. Nearly forty years have passed since that horsey ride and the badlands of western North Dakota are still working on me. These places work on me. I was birthed and nurtured on Red River Valley soil, but nowadays mostly I am fed by places west of the Mighty Mo’. Here my loneliness abates in company of meadowlarks and chickadees. Here I feel small measuring my hand against the print of a mountain lion and grow large again in conquering what seemed an impossible climb. Here I bring my penchant for website click bait, my distracted mind, my annoyance with neighbors and their leaf blowers. I wish I could bring a better version of myself to the place, but that is a foolish thought. I can’t be the best version of myself without these places. I put myself in place and place works on me like a sculptor chipping away to reveal the figure within the stone, and that is the power of place in life.

TAYO BASQUIAT is associate professor of philosophy at Bismarck State College, the director of the college’s “Bringing Humanities to Life” program, a former chair and board member of the NDHC, and ongoing champion of the council’s mission and programs. He’s an avid adventurer, writer, and lover of the natural world, who can’t help but believe it would have been pretty cool to pal around with Yosemite with John Muir or the desert southwest with Edward Abbey.