Presence Past

The ambiguity of the

the constant instability of

memory,

entwined with the feeling of sorrow and the sense of

Art of Memory, Absence, and Presence

Presence Past

“Past Presence” explores the profound intersection of memory, loss, and artistic expression, spotlighting artists who navigate these themes with emotional depth and innovative approaches. This exhibition delves into the works and philosophies of Anselm Kiefer, Chiharu Shiota, Doris Salcedo, Bill Viola, Luc Tuymans, and Joseph Cornell—artists renowned for their evocative explorations of history, personal narrative, and the ephemeral nature of existence.

These artists challenge traditional boundaries, demonstrating that art can serve as a powerful conduit for processing collective and individ ual memories. By engaging with themes of war, relationships, life and death, and the passage of time, they redefine how we understand and commemorate the past. Their works, imbued with cultural commentary and emotional resonance, invite us to reconsider our perceptions of memory and loss in art.

“Past Presence” captures the essence of art that honors memory and mourns absence. This exploration offers a fresh perspective on how art can act as both a vessel for personal reflection and a mirror to societal traumas, enriching our cultural dialogue and emotional understanding.

Essay

The Shapes

of

Memory.

Selected Aspects of Contemporary Art

Eleonora Jedlińska

The Shapes of Memory. Selected Aspects of Contemporary Art consists of fourteen essays devoted to questions addressed in the art of selected artists hailing from Poland and other countries. The works discussed in the book, which have been chosen from the extensive oeuvres of the artists it presents, relate to the question of preserving, in memory, events of fundamental significance to anyone endeavouring to face up to the history of the Second World War and the Holocaust. The artistic attitudes and works of art considered here are an expression of a desire to understand and, perhaps, a warning to future generations in order to avoid a repetition of a tragedy which has forever cast a shadow over the present and the future. The accomplishments of the group of artists discussed in the book are linked by a common motif; they point to the significance of the role played by memory in the process of commemorating and adopting a stance toward that most tragic experience of modern history which was the horror of the extermination of the Jews of Europe during the Second World War. The

fourteen essays were written over the course of recent years and published in dispersed and various ways, appearing in scholarly journals and post-conference publications and given as papers at Polish and international congresses. Together, they form a cohesive and coherent narrative and they constitute a consistent endeavour to encapsulate and analyse the artists’ individual, in a sense ‘reclusive’, facing up to the extreme experience of the Holocaust and the memory bound up with it.

One aspect of their work is presented here, namely, the question of remembrance and commemoration, the feeling of sorrow and pain and the sense of the constant instability, the ambiguity of the world’s understanding in respect of a problem crucial to contemporary art; an ethical attitude toward the Holocaust; a problem in which every artist seeking allusions to the human condition in today’s reality is entangled.

Jacques le Goff wrote:

The Greeks of the archaic age made Memory a goddess—Mnemosyne. She is the mother of the nine muses, whom she has [sic] conceived in the course of nine nights spent with Zeus. She reminds men of the memory of heroes and their high deeds, and she presides over lyric poetry 1 .

Mnemosyne is thus the one who revealed the mysteries of the past to the artist, led him into the world beyond and showed him its darkest sides. She commanded him to remember, because memory is the wellspring of immortality. Thus the artist, Orpheus the Poet with his lyre, sculpted with obsessive repetitiveness in the nineteen thirties, forties and fifties by Ossip Zadkine, who increasingly ‘mutilated’ his subject, is controlled by memory and responsible for memory, a poet prophesying the future and evoking the past. This Orpheus, an artist with his rent body, with his broken instrument, as Zadkine depicted him, became a witness to bygone events, a narrator of the past.

The question of memory, which is fundamental to the Jewish tradition, can be found both in every culture of antiquity and in the Judaeo-Christian culture. Biblical texts contain a host of references to:

(...) the duty of remembrance and of the memory that constitutes it: a memory that is first of all a recognition of Yahweh, the memory that founds the Jewish identity 2

1. Jacques le Goff, History and Memory, trans. Steven Rendall and Elizabeth Claman, Columbia University Press, New York 1992, p. 68

2. Jacques le Goff, ibidem, pp. 68-69.

On the pages of the Bible, we find the phrases:

Beware that thou forget not the Lord thy God 3 (...) Lest 4 (...) thine heart be lifted up, and thou forget the Lord thy God, which brought thee forth out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage 5

and “Remember, and forget not, how thou provokedst the Lord thy God (...) 6. In Isaiah, we have:

Remember these, O Jacob and Israel: for thou art my servant; I have formed thee: thou art my servant: O Israel, thou shalt not be forgotten of me 7 .

The Jewish memory is derived from a tradition which not only enjoins remembrance of God, but also records the reciprocity of God’s remembrance. The Jewish people are a people of memory and the source of their enduring is contained within it. Memory thus conditions cleansing, which is to say, the rectification or, in Hebrew, tikkun, of evil that has befallen; memory endeavours to preserve the past, though not in order to reflect on it, but for it to serve the present and the future.

*

The essays in this book are concerned with artists alluding to the Holocaust in their work. They have been organised chronologically, reflecting the times in which the artists lived and the times in which their works were created. Chapter One opens with a presentation of the works of the artists selected; the works are their creators’ clear reaction to the Holocaust. The chapter contains an essay devoted to Władysław Strzemiński’s set of collages entitled To My

3. The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments, Authorised King James Version; The Fifth Book of Moses, Called Deuteronomy, 8:11, Collins, London, no publication date.

4. Ibidem, 8:12.

5. Ibidem, 8:14.

Friends the Jews . A series of works on paper created soon after the end of the Second World War, it is unique to his oeuvre and, in general, to the history of art.

The essay shows both how Strzemiński’s fortunes, friendships, artistic fascinations and involvement in the life of society were shaped against the backdrop of the concepts of the twentieth-century artistic avant-garde, of which he was a leading ideologist and pioneer, and

6. Ibidem, 9:7.

7. Ibidem, The Book of the Prophet Isiah, 44:21.

how, in the face of the events of the Second World War and the Holocaust, his unfulfilled, utopian dreams underwent what he deemed to be annihilation. The focus of the analysis of the To My Friends the Jews series is on the historical, political and social contexts which conditioned the creation of the ten collages; a crucial aspect here is the closeness and importance of

Strzemiński’s contact with young Jewish artists, for whom he had always remained a master and a man of great noble-mindedness.

To My Friends the Jews was preceded by several other series. The first was created in Vileyka 8 during the winter of 1939–1940 and is entitled Western Belarus ; he and his wife, Katarzyna Kobro, an artist in her own right, had

The Sticky Spot of Crime, Władysław Strzemiński, 1945, To my Friends the Jews

8. The town of Vileyka had been made a part of Poland under the Peace of Riga, which followed the Polish- Soviet War of 1919-1921. It was re-annexed by the Soviet Union after the Soviet invasion of Poland, which was launched on 17th November 1939.

fled to the East when the war broke out, believing that they would be safer there than in the central Polish city of Łódź, where they had lived since the early nineteen thirties. When they returned to Łódź in May 1940, he created a series of drawings entitled Deportations , thematically linked to the mass displacement of the city’s inhabitants. War Against Homes was

the title he gave another series of drawings, which, like those preceding them, were traced out in a torturously winding line on a blank sheet of paper. This time, the abstract forms of people were replaced by forms “grouped in blocks, sometimes fleeing toward the background as if they were coordinated masses, empty volumes” 9. In 1942, he created a series of seven drawings depicting animated, impersonal faces, which is also the generic title he gave those works, Faces . His final series of ‘war’ works were created between 1943 and 1944; Cheap as Mud comprises a set of drawings where the empty surface of the paper features irregular stains and forms, their interiors scrubbed away, leaving an outline which often closes up in some kind of shape and is often broken, either obliterating any figure whatsoever or endowing it with an element both tragic and grotesque, insistently repeated.

In some measure, those series of drawings created during the war foreshadow the one discussed in detail in the first section of the book. In January 1945, Strzemiński began a dramatic series of collages dedicated to the memory of the Jews who were killed during the Holocaust. He called the set, consisting of nine collages, To My Friends The Jews . The works are currently held in the collections of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem. A tenth collage, A Father’s Skull, which was detached from the series by Strzemiński and given to a friend, the poet Julian Przyboś, is currently held in the collections of the National Museum in Krakow. The series is an expression of grief, despair and a sense of the immeasurable tragedy of the Holocaust shown from the perspective of a witness and his helplessness in the face of it. First and foremost, though, as Andrzej Turowksi has remarked, thanks to his use of a double collage

Rothko Chapel interior, Mark Rothko, Eid Al Adha, 1972

9. Andrzej Turowski, Budowniczowie świata. Z dziejów radykalnego modernizmu w sztuce polskiej, Universitas, Kraków 2000, p. 222.

technique using photographs published in the press of the time and his own creativity, Strzemiński introduced “the dimension of memory into the structure of his composition, making a personal memory of the metaphorical narrative axis” 10. The next section of the book presents the work of two American artists, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, who were some ten to fifteen years younger than Strzemiński and thus representatives of the next generation. Both of them were connected with American abstractionism and their works, created in the nineteen fifties, sixties and seventies, constitute a dramatic reaction to the Holocaust, a reaction which is linked to their sense of national identity.

In his mature works, Mark Rothko created abstract paintings invoking Jewish mysticism and biblical messages, respecting the Second Commandment, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing (...)” 11. His large-scale works, almost monochromatic, painted onto the surface of the canvas in thin layers of dark paint, give the impression of pulsating, receding and drawing closer and they emanate an interior light which provides solace and reconcilement. They can also be considered by way of cabalistic references and a connection with the Jewish concept of the act of renewal, the concept of the Hebrew term tikkun, understood as a desire to rectify the world after destructive events. When Rothko created paintings, he supplemented their content with a religious and philosophical message and fulfilled the most vital Jewish injuctions concerning the remembrance of the dead.

In Barnett Newman’s series of abstract paintings, The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani , and in the ‘Black’ paintings in the Rothko Chapel in Houston, by way of which the two artists strove to depict extermination, the abstract

10. Ibidem, p. 228.

11. The Holy Bible..., ibidem, The Second Book of Moses, Called Exodus, 20:4.

12. A village in south-east Poland.

forms of the works, their severe, dark-toned hue, evocative seriousness and silence and, finally, the arduous process of their creation, sublimate and sacralise the victims of the Holocaust. The witness to the Holocaust borne by a painting outwardly devoid of formal allusions makes itself manifest here as a striving to express experiences which the artists had not undergone directly. The experience of the tragedy of the Jews of Europe, a community of suffering and sorrow which they felt part of, brought about their focus, in their art, on what the intellectual North America of the mid twentieth century understood as the tradition of Judaism.

Chapter Three of the book is devoted to the work of Tadeusz Kantor, one of the most important Polish artists of the twentieth century. He was born in Wielopole Skrzyńskie 12 on 6 th April 1915, ten years after Barnett Newman’s birth and twelve years after Mark Rothko’s. He died in Krakow on 8 th December 1990. The subject of the aspect of Kantor’s work presented in the essay is the significance of memory in his life and in the art he created in the Cricot 2 Theatre, which he founded in Krakow in 1955 and which evolved into his Theatre of Death, his main work. In the three productions comprising his ‘family triptych’, namely The Dead Class (1975), Wielopole, Wielopole (1980) and Let The Artists Die (1985), as well as his I Shall Never Return (1988) and his final theatrical work, Today Is My Birthday , which was its author’s ‘personal challenge’ and was premiered posthumously in Toulouse early in 1991, he made his art a medium of memory, recollections, fears, feelings and experiences.

The war filled his memory and the experiences of the twentieth century left a particular mark on his understanding of the world and of art. In Kantor’s work, experiences connected with the Second World War and with the

Holocaust find singular expression, often far removed from metaphor. The record of the memory of the events which had irreparably destroyed the world he had grown up in and witnessed found its reflection in the dreams that haunted him, the experiences of his closest friends and the memory of the saved. The Theatre of Death is a theatre of memory and it was for memory, for its homelessness, to use Kantor’s words, that, after many years of

searching, he found a place. That place was the Theatre of Death.

The chapter discussing the work of Moshe Kupferman, a Polish-Israeli artist who was born in Jarosław 13 in 1926 and died in Israel in 2003, concerns something distinctive from his oeuvre, namely, a series of eight paintings entitled The Rift in Time. In this series of outwardly abstract canvases, Kupferman, who had survived the Holocaust and had proclaimed his dislike of art alluding to it, took on a theme deeply rooted in a tradition of the Jewish mystics, in other words, the tradition of rending garments as a sigh of mourning, and, in so doing, he declared his own constant thought and pain, which had thus far found no expression in his works. The series was created four years before his death as a ‘song of mourning’, a testament to, and prayer for, the dead and, at one and the same time, as an expression of memory, a return to his religious roots and the myths of his forebears.

The essay constituting Chapter Five, which discusses the work of Christian Boltanski, is entitled Christian Boltanski: ‘Autobiography’: Memory/Death/Life. A French artist well- known in Paris, where he has presented his works and

13. A town in south-east Poland.

Wielopole, Wielopole, Tadeusz Kantor, 1980, Cricot 2 Theatre, club Stodoła, Warsaw, Poland

Let the Artists Die, Tadeusz Kantor, 1985, La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, New York

paratheatrical pieces several times, he has said of his art, which makes profound allusion to memory, that it underscores the meaning of seeking his own identity, a lost part which, as he puts it, exists in the ‘abyss of memory’. Boltanski’s art is an incessant facing up to the trauma of the past, the memory of the Holocaust and, above all, the history of his Jewish family. In this world, fiction intertwines with reality and the truth of a image/photographic portrait interweaves with an invented, albeit credible story.

For Boltanski, Tadeusz Kantor was the first and peerless master, and his world, like Kantor’s, seems to be overwhelmed by times past and by death, rendered unreal by the state of yearning and melancholy which is omnipresent here. Boltanski created the works discussed in this section of the book over a period stretching from the nineteen seventies to the present day. They allude to those aspects of human existence which are bound up with his childhood, his biography and memory understood as a primary driving force in life, conditioning existence in a concrete state, memory experienced and obsolete. That memory was formed by family stories, by collected photos, some genuinely of family members and some assumed to be, by imaginings and by confrontation with a reality enduring in the shadow of the tragedy that afflicted his Jewish kin.

The next section of the book relates to the work of Anselm Kiefer, who was born in 1945 and is one of Germany’s most outstanding artists. His biography and his work, monumental and dramatic, is focused on the problem of memory as a carrier of responsibility and expiation for the deeds of previous generations of Germans. In the essay presented here, I have turned my attention to one of the many series of book-cum-sculpture monuments from his oeuvre. The series in question, dedicated to the

memory of the outstanding poet Paul Celan, who died a tragic death, is entitled Für Paul Celan and the essay addresses three of the works in the series; Ukraine Für Paul Celan; Arche Für Paul Celan; and Runengespinst.

In Chapter Seven, Marek Chlanda: Image and Thought. Tango of Death, I present an analysis set against the backdrop of an historical context, the German occupation of Lwów 14 Marek Chlanda was born in Krakow in 1954 and

14. Now Lviv, in Ukraine; before the Second World War, the city was part of Poland. I Shall Never Return, Tadeusz Kantor, 1990, Cricot 2 Theatre, club Stodoła, Warsaw, Poland

the work in question, which dates from 2004, is entitled Cosmos – Tango of Death – in Relation to Blake. The wellspring of the work is a wellknown photo which was most probably taken in the winter of 1942 at the Janowska extermination camp, which was located at No. 134 ulica 15 Jankowska in Lwów. What interested me is how, in the world of chaos that surrounds us, the artist seeks order, desiring to recreate it by grasping that which unites and forms a dependence between things, events, memory, the ethics of behaviour and conscience. Of the essence here is the underscoring of the singular spiritual connection between the visions-cum-warnings which William Blake addressed to future generations and Marek Chlanda’s skill in reading and entering into their message. He seems to be saying that Blake’s cautions failed to hold back the course of events which occurred in the twentieth century and scarred subsequent generations with the most acute drama in the history of human suffering, pain and iniquity. In its entirety, this work of Chlanda’s consists of ten sketches-cum-exercises, drawings and notes; of these, I decided to focus on one eight-sketch series, created between 1973 and 2008.

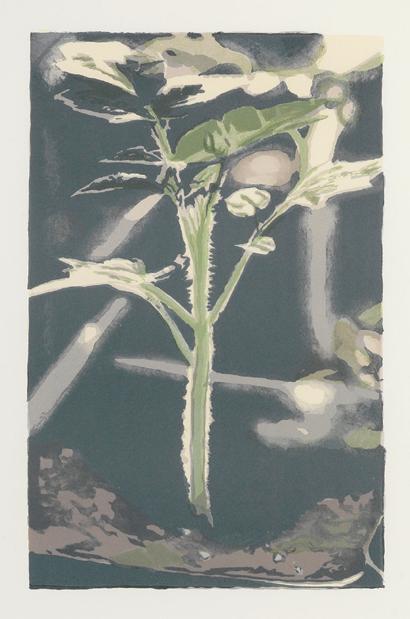

The next essay, entitled Frühlingswind, or Spring Wind , concerns the paintings of the Belgian painter Luc Tuymans, who was born in 1958. His painting, intriguing, aesthetically perfect and almost always provided with a commentary, conveys the darkest of content, hidden, camouflaged and evoking disquiet and watchfulness in the viewer. This is no recreation of truths faithfully recollected or told; Tuymans presents a world of menace, violence and pain. His pastel works, painted using traditional techniques, allude to the question of both mental and biological memory. Through its outward neutrality, we interpret his painting as a ruthless indication of what the Holocaust was, of what

15. ulica – street; when written as part of a street name, the word is not capitalised.

‘legacy’ it left contemporary people and in what way the memory of it has changed the reception of traditional portrayals and habits in the viewer’s relationship with a work of art.

Chapter Nine is devoted to the question of the image’s memory, the phenomenon of the constancy of painting in the history of culture. The early works of Zofia Lipecka, who was born in Poland in 1957 and has lived in France since the nineteen sixties, allude to the fundamental meaning of memory shaped in the most distant, archaeological past, to some extent by way of language. In her paintings from the nineteen eighties, she engages with the meaning of the sign both as an archetypal symbol which is memory’s vehicle and defender and as a category triggering tension between human beings and their past.

The next section of the book, which also makes reference to Zofia Lipecka’s work, can be considered in relation to the art of Marek Chlanda, Luc Tuymans and Rafał Jakubowicz, all of them artists who bring their thinking and work into confrontation with the memory of the Holocaust. That space in their art is perceived from the perspective of the generation which was born after the war and makes its way to the truth about the Holocaust via the memory of witnesses, historical documents, photographs and the memory of places.

In setting her work facing, and in relation to, the past and the present... her Project Trzeblinka is conceived to extend across years..., Lipecka invokes the remembrance of the Holocaust as it endures in our memories by way of place, sign and image. Here, with Project Treblinka , she remains consistent as regards her earliest artistic achievements, where she explored the prehistory of the source and endurance of the sign in culture, the sign understood as the first image. In speaking of the

Memory the

Memory the

The Shapes of Memory.

is wellspring of is wellspring of

history of a place particularly marked by the death of the Jews of Europe during the Second World War, in her annual act of photographing a place on their road to an extermination camp and, at the final stage of each work, in recreating the landscape around the camp as it looks each year, forcefully underscoring the power of painting, the value of art itself, she endeavours to defend its primordial worth, both ethical and aesthetical. The memory of which Lipecka speaks steps beyond the borders of history as an academic discipline; it decides our identity and determines the possibility of entering into a dialogue with, to call upon Giorgio Agamben’s words, that most “devastating experience in which the impossible is forced into the real” 16 As she considers the question of the memory of the Holocaust and moors herself in the present, she also undertakes a defence of postHolocaust art, pointing to landscape painting as the most traditional and most firmly rooted motif in the history of European painting. Whilst grappling with the problem of representing the Holocaust, she shows the necessity of art’s existence and permanence and, whilst neither demolishing nor deprecating the boundaries of the thematic canons of visual art, she endeavours to find the means of expression most suited to this topic.

In the next two chapters, I present the work of Rafał Jakubowicz, born in Poznań 17 in 1974. My analysis is based on works he created in 2002 and 2003. The first, The Truth is in Memory or Key Words , is concerned with the

manipulation of language applied in the Third Reich and the endurance of signs which have survived in the consciousness, or perhaps the subconsciousness, of subsequent generations. In a work entitled Seuchensperrgebiet (2002; Territory Endangered by Epidemic), he speaks of the corruption of language typical of Nazi Germany. Rather like what occurs in Tuymans work, Jakubowicz reveals something hidden be neath outwardly harmless functioning in the present day, namely, the ambiguity of banal objects, words, images and places contaminated by their use in the crime of the Holocaust. He wants to focus our attention and sensitivity on the meaning of the words and language in which we have learned to express a description of events that, it would seem, are impossible to express and to describe.

The second chapter devoted to Jakubowicz discusses a video installation, Synagogue/ Swimming Pool/שחיה בריכת , which consists of a projection of a Hebrew inscription reading שחיה בריכת (swimming pool), two video films and a postcard. My analysis here is based on sociological research and the work, which was created in the artist’s home town of Poznań, is presented as focusing the viewer’s attention on the ‘place’s memory’ and the memories of the city’s current residents who are users of a swimming pool... an erstwhile synagogue profaned by the Germans. On 4 th April 2005, the sixtieth anniversary of the Nazis’ destruction and subsequent rebuilding of the Poznań synagogue, Jakubowicz performed an artistic

16. Giorgio Agamben, Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, (Homo Sacer III), trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen, ZONE BOOKS, New York 1999, p. 148

17. Situated in west-central Poland, Poznań is one of Poland’s oldest and largest cities.

action; he projected the aforementioned Hebrew inscription onto the façade of the building. In this work, he was seeking the vestiges of memory, as well as the building’s history and original function. The video film constituting one of the elements making up Swimming Pool in its entirety shows the contemporary interior of the

former synagogue. As he makes his way inside with the camera, he hunts for places and traces which might ‘speak’ of the past and he films the swimming-pool fixtures, fittings and equipment in such a way as to suggest associations with the tragedy of the concentration camps. Jakubowicz’s work broaches an essential question, namely, the process of preserving in our memories images and events in which we were not direct participants. Their ‘activity’ penetrates our memory via mediated images, via knowledge and imagination, where truth intertwines with fiction. Jakubowicz does not so much rescue memory as hunt for its evanescent traces; he wants to explore the “meaning of the vestiges of the Holocaust in our collective imaginarium” 18 , as Izabela Kowalczyk concludes in her analysis of his installation.

In the next chapter, entitled Elżbieta Janicka’s Artistic Journey to ‘An Odd-Numbered Place’. Reflections on the Past, Memory, Time and Identity, the question of our present in relation to the Holocaust is broached. Janicka’s work, like those created by the artists of the post-war generation, Tuymans, Lipecka, Chlanda, Jakubowicz, and described in the preceding chapters, alludes to absence and, at one and the same time, appeals not only our memory and imagination, but also to places’ memories. Like the previously discussed artists, she points to the fact that there is neither place nor memory or imagination which would not be burdened by guilt... the guilt of involvement in the tragedy of the Holocaust. The artists discussed in this book turn our attention to the process of forgetting which is taking place and they show how historical memory transforms into imagination, vague associations and the photographic images preserved in our memories. Janicka’s An Odd-Numbered Place is six square photographs measuring 127 x 127 cm. They depict a

Wenn der Frühling kommt, Luc Tuymans, 2007, Portfolio with 17 digital pigment prints on semi-transparent paper, mounted on sheets of rag paper

18. Izabela Kowalczyk, Podróż do przeszłości. Interpretacja najnowszej historii w polskiej sztuce krytycznej, Academica. Wydawnictwo SWPS, Warsaw 2010, p. 237.

für Paul Celan, Anselm Kiefer, 2006, Oil, emulsion, acrylic, branches, metal, wood, and chalk on canvas mounted on board

white surface surrounded by the black edges typical of developed photographic film. The word AGFA is visible on the edges, along with the manufacturer’s numerical data. Each photo has a caption; the name of the site of a concentration camp and, with each name, a figure which tells us the number of victims murdered in that place. The photographs present nothing. They are images of the air rising (?) above the places with the names signifying that they were places of extermination; Majdanek, Bełżec, Sobibór... We interpret Janicka’s photographs as works about the impossibility of representation, about the obliteration of traces and about memory. An Odd-Numbered Place consists of several elements; the photographs, where an image of the air above former places of extermination has been preserved, the captions bearing the names of those places and the number of victims murdered in them. There is a second aspect to the Odd-Numbered Place exhibition; an interior where the sound of recordings made in those places is played. Elżbieta Janicka’s work speaks of the impossibility of expressing/ depicting the memory of the Holocaust, but it also speaks of the impossibility of keeping it alive, it speaks of obliteration, be it unintentional or deliberate.

The final chapter is devoted to an analysis of a monument as a place of memory, which is to say, the memorial raised within the grounds of the former German extermination camp at Bełżec. The camp is located in eastern Poland, not far to the south-east of the village of Bełżec, close to the railway line running between Lublin 19 and Lwów/Lviv. Between March and December 1942, the Germans murdered approximately six hundred thousand people in that place.

The building of the monument was preceded, in 1997, by a competition for an artistic solution for a new memorial. The winning

project, a collaborative work by sculptors Andrzej Sołyga, Zdzisław Pidek, and Marcin Roszczyk, provided, first and foremost, not only for the protection and commemoration of the land where mass graves holding the remains of victims had been found, but also for a symbolic representation of the camp itself. Along with the monument, a museum was designed; its tasks are to document the camp’s history, to disseminate that history to the general public and to

I Accuse the Crime of Cain and the Sin of Ham, Władysław Strzemiński, 1945, To my Friends the Jews

19. A city in east Poland.

collect any and every kind of material concerning the camp, the victims and the places where the deportations to Bełżec occurred.

First and foremost, the art discussed in this book touches upon questions relating to the past, to history and to memory. The common theme running through the works presented here is that of events connected with the Second World War and the Holocaust, along with complex relationships with, and allusions to, the post-war process of turning toward collective memory. The memory of the Holocaust is present in the work of artists around the world and, particularly, in Europe and America. The artists whose selected works are analysed and interpreted on the pages of this book, from Władysław Strzemiński’s To My Friends the Jews , created during the war and soon after it had ended, to the place of memory marked by the memorial within the grounds of the former extermination camp in Bełżec, have all undertaken questions relating to history, but seen from the perspective of the present day. For it is the present day which conditions our perception of the past; that which has been obliterated, forgotten and stifled returns in successive endeavours to evoke, in art, the events most frequently discussed within the framework of historical and political debate. The selection of works presented here is the result of choices not only subjective, but also incomplete, in that it was not originally my intention to create a compendium. The act of choosing was focused around works which direct our attention toward a past that has been ousted, a past that is, so to say, absent, overlooked, but which, for all that, is building our present day. Thus memory, endeavours to keep the memory of the victims alive and the duty of remembrance constitute the fundamental substance of the works presented in the book. The premise was also to

underscore the defence of poetry and art, the defence of painting after the Holocaust and the conviction that art is duty-bound to bear witness and transcribe memory, which constitutes the sense of the image’s enduring at all. History marches onward, marked by a sense of a lack of continuity, by crises, turning points, forgetting and seeking the vestiges of the past; what remains are images, works of art serving, inter alia , to oppose both the human inclination to surrender to fate and the inertia of the human memory. Then, works of art like this become, at one and the same time, a tool to help recover what would seem to have been lost... and that is nothing other than memory. Reviving the past, at its most painful as well, is the equivalent of grappling with what happened, with what our heritage is. Those questions are broached in this book.

English translation by Caryl Swift

Artists & Work

Anselm

born in 1945, Germany

Born at the close of World War II, Anselm Kiefer reflects on and critiques the myths and chauvinism that propelled the German Third Reich to power. With Wagnerian scale and ambition, his paintings depict the ambivalence of his generation toward the grandiose impulse of German nationalism and its impact on history. Balancing the dual purposes of powerful imagery and critical analysis, Kiefer’s work is considered part of the neo-expressionist return to representation and personal reflection that came to define the 1980s. At that time, Kiefer was the centerpiece of a critical debate on the continued validity of painting, the ability of representation to heal deep historical wounds, and the legacy of fascism.

Zweistromland: The High Priestess, 1985–87, depicts the union of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers as an intersection of rusted, crumbling modern train tracks, bridges, or superhighways. Water often signifies life, hope, and renewal, but Kiefer’s reinterpretation suggests thwarted ambition and broken promises. With hues of blue and shadowy passages of black and brown, the

Kiefer

monumental painting offers a dour look at Germany’s past—a country believed by its Nazi ancestors to be a new, modern cradle civilization on the scale of Mesopotamia and subsequently revealed to be a deeply flawed force for hate.

In Deutschlands Geisteshelden, 1973, Kiefer superimposes historical meaning on a setting of personal significance, his former studio in a rural schoolhouse. Painted on six strips of burlap sewn together, Kiefer creates a textured, wooden room receding sharply into space. The work recalls both hunting lodge and a memorial hall. Fires burn on the walls, and the surface suggests that the entire scene has been singed with flame. According to art historian Mark Rosenthal, this work demonstrates that “Kiefer’s attitude about a Germany whose spiritual heroes are in fact transitory and whose deeply felt ideals are vulnerable is not only ambivalent but also sharply biting and ironical....These great figures and their achievements are reduced to just names, recorded not in a marble edifice but in the attic of a rural schoolhouse.”

Die Himmelspaläste, 2003–18, reinforced concrete and lead

Sol Invictus, 2007, Emulsion, shellac, oil, and chalk on linen canvas

Die Orden der Nacht, 1996, emulsion, acrylic, and shellac on canvas

Die berühmten Orden der Nacht, 1997, acrylic and emulsion on canvas

Mésopotamie, 2007–20, Mixed media, Ensemble of 15 paintings

Nürnberg, 1986, Oil, straw, and mixed media on canvas

Heavy Cloud, 1985, lead and shellac on photograph, mounted on board

Black Flakes (Schwarze Flocken), 2006, Oil, emulsion, acrylic, charcoal, lead books, branches, and plaster on canvas

born in 1951, United States

Bill Viola is a video and installation artist. Viola earned a BFA degree in Experimental Studios in 1973 from Syracuse University, where he studied both visual art and electronic music. He holds multiple honorary doctorates, including those from Syracuse University, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, California Institute of the Arts, and Royal College of Art, London. His artistic contributions are considered essential to the recognition of video as a valid medium in Contemporary Art. Throughout his career— which spans four decades—Viola has used state-of-the-art technology to create video installations, electronic music, soundscapes, and television broadcasts. His work has been displayed in a variety of venues around the world, and Viola has traveled extensively, living and working in many locations, such as Italy, Japan, and Australia. Viola’s work often explores the themes of spirituality and introspection, inviting audiences to better understand themselves through their perception of sensory experience. Transcendental human experiences, such as death, birth, and understanding of

Viola

consciousness, are key themes in Viola’s art. Some of his best-known works include The Crossing (video and sound installation, 1996), The Reflecting Pool (videotape, 1977–1979), and The Passing (videotape, 1991).

Bill Viola

Ascension, 2000, Color video projection, Stereo sound, 10 min.

The Reflecting Pool, 1977–79, Color videotape, Monoaural sound, 7 min.

The Passing, Black and white video, Stereo sound, Documentary film, 54 min.

Nantes Triptych, 1992, 3 Color video projection, Stereo sound, 30 min.

Five Angels for the Millennium, 2001, 5 Color video projections, Stereo sound, 51 min.

He Weeps for You, 1976, Video/sound installation, Water drop from copper pipe, Live color camera with macro lens, Amplified drum

I Do Not Know What It Is I Am Like,

1986, Color video, Stereo sound, 89 min.

The Dreamers, 2013, Color video, Stereo sound, Continuously running

Shiota

born in 1972, Japan

Chiharu Shiota, who now lives and works in Berlin, was born in Osaka, Japan. The artist’s early studies at Kyoto Seika University, Japan, were accompanied by a semester exchange to the Canberra School of Art, Australian National University, Australia, where her aims shifted towards amalgamating painting, performance and the body.

No longer satisfied with art for art’s sake, the next step for Shiota after Kyoto was Germany and an intense period of study under artist Marina Abramović, known for her performance practice that tests physical and emotional thresholds. Chiharu’s time with Abramović seeded clarity in her practice in both concept and approach, now prioritising the relationship between memory and objects as well as the power of absence.

Her newfound ethos was apparent in her performance, Try and Go Home (1997), where she dug a cavity in the earth and rolled naked into and out of the space. Here, her interest in displacement and the affectivity of positive and negative space was born.

Known for her web-like yarn-based art installations, Chiharu Shiota’s practice is motivated by the omnipotence of memory. An exhibitor in numerous international art shows, Chiharu Shiota represented Japan at the 56th Venice Biennale. Chiharu Shiota’s is best known for her mixed-media web-like art installations using yarn in combination with an array of objects. Shiota confronts her own experiences by cultivating special spaces with a physical and emotional passage in mind.

Chiharu Shiota

The Web Above Our Lives, 2022, Bronze, rope

Accumulation - Searching for the Destination, 2023, Old suitcase, rope

A Question of Perspective, 2022, Desk, chair, paper, rope

Chiharu

Beyond Memory, 2019, Wool, paper

Chiharu Shiota

Lost Words, 2017, Bible pages in different languages, black wool

Chiharu

Over the Continents, 2014, Old shoe, red wool

Chiharu

Chiharu Shiota

Doris

Salcedo

born in 1958, Colombia

Doris Salcedo creates sculptures and installations inspired by violence and political conflict in Colombia. She received her BFA from Universidad de Bogotá, Columbia, in 1980. After receiving her MFA in Fine Art from New York University in 1984, Salcedo returned to Universidad de Bogotá to teach. Her artistic process often involves interviewing victims of violence and using their experiences as the influence behind her work. In her pieces, Salcedo combines mundane materials, like furniture and clothing, in such a way that they often evoke feelings of horror and despair. In a 2011 interview with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), the artist stresses the importance of memory and her belief that we must confront past events. Salcedo wants her work to be a connection to a sacred space where an individual’s memory is preserved with dignity. One of her most well-known installations is Atrabiliarios (1992–1997), a work in which she placed shoes in wall niches and sewed them closed using translucent animal fiber and surgical thread. Shoes were donated by the families of desaparecidos (those that have disappeared). Her most recent exhibition at London’s White Cube gallery was Plegaria Muda; the exhibition consisted of an installation made of 45 units of long tables that were stacked surface to surface with a layer of earth between them. The show also included Flor de Piel, an enormous shroud made of thousands of rose petals sewn together to serve as a collective burial site. Salcedo received a Penny McCall Foundation Grant in 1993 and a Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Grant in 1995. She was also awarded The Ordway Prize from the Penny McCall Foundation in 2005. Salcedo currently lives and works in Bogotá.

Atrabiliarios (Desafiante), 1989–92, Wall construction, Wood, found shoes, animal fiber and surgical thread

Atrabiliarios (Desafiante), 1992–93, Wall construction, Wood, found shoes, animal fiber and surgical thread

IV

Disremembered

, 2014–2015, Silk thread and nickel plated steel

Thou-less and Untitled, 2001–02, Stainless steel

Unland: the orphan’s tunic,, 1997, Wooden tables, silk, human hair and thread

Uprooted, 2020–22, 804 dead trees and steel

Doris Salcedo

Joseph

Joseph Cornell

Cornell

born in 1903, died in 1972, United States

A premier assemblagist who elevated the box to a major art form, Joseph Cornell also was an accomplished collagist and filmmaker, and one of America’s most innovative artists. When his sister and brother-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. John A. Benton, donated a collection of his works and related documentary material in 1978, the NMAA [now the Smithsonian American Art Museum] established the Joseph Cornell Study Center.

Born on Christmas Eve, 1903, Joseph Cornell was raised in an affluent, closeknit family in Nyack, New York. He attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, as a science major between 1917 and 1921, but did not graduate. While working as a textile salesman in New York between 1921 and 1931, Cornell began exploring the city and its cultural resources, and converted to Christian Science, thereafter a major influence on his life and work. In 1929, his family moved to Flushing, New York, where he lived until his death on December 29, 1972.

His art has been described as romantic, poetic, lyrical and surrealistic. Self-taught but amazingly sophisticated, he created his first

collages, box constructions and experimental films in the 1930s. By 1940, his boxes contained found materials artfully arranged, then collaged and painted to suggest poetic associations inspired by the arts, humanities and sciences.

He believed aesthetic theories were foreign to the origin of his art but said his works were based on everyday experiences, “the beauty of the commonplace.” An insatiable collector, he acquired thousands of examples of printed and three-dimensional ephemera—searching the libraries, museums, theaters, book shops and antique fairs in New York and relying on his contacts across the United States and in Europe. With these objects, he created magical relationships by seamlessly combining disparate images.

Cornell was an imaginative and private man who, mingling fantasy and reality, produced works outstanding not only for their originality and craftsmanship but for their complexity and diversity.

Untitled (Bebe Marie), early 1940s, Papered and painted wood box construction

Untitled (Medici Boy), 1942–52, Wood box construction

Palace, 1943, Box construction

Joseph Cornell

Andromeda: Grand Hôtel de l’Observatoire, 1954, Box construction

Joseph Cornell

Untitled (Hôtel de l’Etoile), 1954, Wood box construction,

The Nearest Star, an Allegory of Time, ca. 1962, Painted wood and glass box construction

Untitled n°3, ca. 1955, Box construction

Joseph Cornell

Joseph Cornell

Soap Bubble Set, 1948, Cork, glass, velvet, gouache, clay pipes, coral, painted wood, and paper collage

Luc

111

born in 1958, Belgium

Tuymans

Luc Tuymans is a Belgian visual artist best known for his paintings which explore people’s relationship with history and confront their ability to ignore it. World War II is a recurring theme in his work. He is a key figure of the generation of European figurative painters who gained renown at a time when many believed the medium had lost its relevance due to the new digital age. Much of Tuymans’ work deals with moral complexity, specifically the coexistence of ‘good’ and ‘evil’. His subjects range from major historical events such as the Holocaust to the seemingly inconsequential or banal: wallpaper, Christmas decorations or everyday objects for example. The artist’s sparsely-coloured figurative paintings are made up of quick brush strokes of wet paint. Tuymans paints from photographic or cinematic images drawn from the media or public sphere, as well as from his own photographs and drawings. They often appear intentionally out of focus. The blurred effect is, however, created purposefully with painted strokes, it is not the result of a ‘wiping away’ technique. Formal and conceptual oppositions recur in his work, which is echoed in

his remark that while ‘sickness should appear in the way the painting is made’ there is also pleasure in its making – a ‘caressing’ of the canvas. This reflects Tuymans’ semantic shaping of the philosophical content of his work. Often allegorical, his titles add a further layer of imagery to his work – a layer that exists beyond the visible. The painting Gaskamer (Gas Chamber) exemplifies his use of titles to provoke associations in the mind of the viewer. Meaning, in his work, is never fixed; his paintings incite thought. A related characteristic of Tuymans’ work is the way he often works in series, a method which enables one image to generate another through which images can be formulated and reformulated ad infinitum. Images are repeatedly analysed and distilled, and a large number of drawings, photocopies and watercolours are produced in preparation for his oil paintings. Each final painting is, however, completed in a single day.

Gen, 2004, Lithograph in colors, 40 x 25.5 cm. (10 x 15.7 in.)

Gaskamer (Gas Chamber), 1986, Oil on canvas

Abe, 2022, Oil on linen

Issei Sagawa, 2014, Oil on canvas

Wenn der Frühling kommt, 2007, Portfolio with 17 digital pigment prints on semi-transparent paper, mounted on sheets of rag paper

Corso IV, 2015, Oil on canvas

Untitled from The Temple, 1992–93, Etching and aquatint on paper, One from a portfolio of 8 aquatints

Easter, 2006, Oil on canvas

De Wandeling (The Walk), 1991, Oil on canvas

Artist Essay

Luc Tuymans

Memory

Andrea Lauterwein

‘My biography is the biography of Germany.’ 20

‘My poetry is vertical and one of its planes is fascism. But I see all of its layers.’ 21

Loss of Memory, Lack of Imagery

Anselm Kiefer was born on 8 March 1945 in Donaueschingen, in a completely ravaged country that in 1949 became the Federal Republic of Germany—that part of the country that was aligned with the West. He therefore belonged to the ‘second generation’, who grew up in a climate of simultaneous amnesia and guilt, with no personal experience or memory of the Nazi regime. 22 This generation’s awareness of Nazism and of the Shoah could therefore only be brought about through mediation, the collective memory being dependent on information transmitted directly or indirectly by the surrounding world—family and school, books, art, newspapers, the cinema, television, monuments, and political ceremonies.

At the end of the war, the ‘first generation’ was like a nation of fallen heroes, who wanted only to forget as quickly as possible their period of collective hypnosis. The institutions of the Federal Republic granted a kind of amnesty to the people, and took on complete responsibility for the past, but they also imposed a new identity which wanted to cut all ties with German tradition and the Nazi past. A leaden blanket covered up the memories of these first-generation Germans—the good as well as the bad memories of the Nazi era—and as a result, history was also blocked off from family discourse and there was no dialogue between the generations. This was to be a major obstacle to the memory research of later generations. 23

When the German people were confronted with photographs of the concentration camps being liberated, the self-censorship of the imagination was further reinforced and the memory gap widened. These horrifying images, presented in an accusatory context, had the paradoxical effect of a ‘machine of disimagination’. 24

20–37. descriptions in Endnotes.

The consequences of this memory gap were disastrous. It not only hindered the articulation of moral responsibility, but it also prevented the vague sense of collective guilt from being transformed into individual responsibility. 25 Within a cultural context, a similar blocking out of certain words, and of images which emerged where language could not cope, plunged Federal Germany into a veritable crisis of representation. 26

The history of West German art provides a good illustration of this hastily constructed new identity, which shut out individual experiences and imaginations. Artists and institutions moved abruptly from the monumental and figurative art prevalent under the Nazis to the abstractionism imported by the occupying forces. 27 During the immediate postwar period, artists therefore returned to the forms and styles that had formerly gained favour in the 1920s, or imitated lyrical French abstractionism, or copied the informal and minimalist techniques of the Americans. This movement, which turned its back on everything that had hitherto gone to make up the fundamental character of ‘German Art’—morbidity and desolation, from the engravings of Dürer through the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich right up to German Expressionism—stripped art both of subjectivity and of history.

Born around 1945, the artists of Anselm Kiefer’s generation responded critically to this sudden substitution of the ‘myth of Western art’ for the ‘myth of German art’. 28 Kiefer in particular continually defended the right to cultural individuality and denounced the contemporary artistic trends imported into Germany from the United States. 29 His opposition to all formalism, and to artworks turning into ‘design’, 30 and his distrust of the rigid theories of the Bauhaus 31 were all inseparable from his critique of ‘zero hour’. This was the concept that enabled the official history

Arminius’s Battle, Piet Mondrian, 1976, Oil on canvas

Only with Wind, Time and Sound, Anselm Kiefer, 1997, Sand, emulsion, acrylic and shellac

of Germany to be reformulated according to a teleology that took 1945 as its starting point and at the same time wiped out all collective memories of 1933 and 1942. Piet Mondrian—Arminius’s Battle , painted in 1976, exposes this dichotomy in almost didactic fashion. The prime objective for Mondrian, the ‘Calvin of abstraction’ as Kiefer called him in a book published in 1969, was to purge painting of every hint of tragedy, giving priority to light, air and surface. Kiefer, on the other hand, reaffirms the historical complexity of things by restoring narrative function and subjectivity to his lines of composition. He invests Mondrian’s bare tree with tangled forms and thick materiality, re-establishing its mythical substrata and its vertical memory.

The foundation of a new culture cannot take place without recalling those that have gone before: ‘My thought is vertical, and one of its planes was fascism. But I see all its layers. In my paintings I tell stories in order to show what lies behind history. I make a hole and I go through.’ 32 Here Kiefer connects with Celan, who observed a monstrous affinity between the language of abstraction, pure art, and the reification of the Other. In his critique of disembodied abstraction or horizontality without memory, the poet defended vertical knowledge as being designed for life and for poetry, with the inscription of words into history and of history into words. In 1960, Celan wrote in a preparatory note for The Meridian , his acceptance speech for the Georg Büchner Prize: ‘whatever is devoid of germs, aseptic, constitutes an assassin; fascism today lies in formal design’. 33

History reappeared in the German art of the late 1960s. A first wave of committed artists denounced Nazism head on. Applauded by the left wing and ignored by the right, these artists— following in the footsteps of John Heartfield— were working in occupied territory. Kiefer’s

generation, however, rejected the consensual Manichaeism of such committed art, and set out to reach a heterogeneous public in order to break up the consensus, their strategy consisting of the conscious use of ambiguity. These were the history painters, starved of imagery, who for convenience have been dubbed the German Neo-Expressionists, and who appeared at the end of the 1960s in the wake of Joseph Beuys’s memory works. Among them were figures as diverse as Gerhard Richter, Markus Lüpertz, Georg Baselitz, Jörg Immendorf, and Kiefer himself. What united them was figurative art and a return to the individual, though not any individual, for they worked with themes—without explicitly engaging in hindsight—that had once been drummed into people’s minds and had then been expunged from the collective memory. We see bodies in these pictures, and heroic figures that have been mutilated, totems of the nationalistic past, fetishes of Nazism—spades, stags, sheaves of corn, German shepherds, Stuka bombers, Nazi palaces and swastikas. By showing this iconography which the conscious mind had repressed, these artists declared that Nazism was indeed a part of their history, although in doing so they placed their new identity at risk. 34

Before taking his place in the higher echelons of West Germany (in 1999 his Only with Wind, Time and Sound [ill. 5] became part of the Bundestag collection), Anselm Kiefer was undoubtedly one of the most controversial artists of his generation. Between 1970 and 1990, even though his work had already received critical acclaim in the United States, Japan and Israel, most German critics were united by a consensual ban on representation and at the same time were hostile to the provocative and cathartic elements of his art. He was accused of depicting Nazism ‘not in order to denounce it, but in order

to joyfully perpetuate it.’ 35 Like other German artists of his generation, Kiefer questioned his own artistic heritage, focusing on the iconographic and mythological elements of German culture which initially fed the national identity, were taken over by Nazism, and then suddenly, almost overnight, were buried in the deepest strata of the collective unconscious. Kiefer also revived the mechanisms through which National Socialism exerted its fascination, in the hope that this would enable him to gain a better understanding of them and so move beyond their frozen symbolism. However, you will search his work in vain for the sadomasochism of Nazism and everything else that contributed to its ‘erotic attraction’ in the ‘new discourse’ of the 1970s— such as Jean Genet’s black leather, or the perversions of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. 36

The hostility towards Kiefer may be explained by the singularity of his appeal to the heart of his own generation, by the pathos, the personal involvement and the provocative empathy with which he tackles the collective issues that underlie his work on memory. ‘My biography is the biography of Germany,’ 37 he declared in 1988, and it is with this same effrontery and persistence that he continues to pursue a memory-based course of therapy in his works. These illustrate the different phases of grief outlined by Freud—the refusal to accept reality, the flood of emotion, separation, and finally the discovery of a new relationship with oneself and the world—a discovery which in Kiefer’s case was linked to the poetry of Paul Celan from 1981 onwards. This involvement with German memory was followed by disengagement, and the painter’s libido turned towards Jewish sources. His interest in the Jewish imagination—which other German artists of his time have scarcely considered— may explain why the controversy that exploded around him was so emotional in its nature.

in lies that in lies

I make

make

behind order to show history.

behind order to show history. a hole and go through. a hole and go through.

Bomb: Chiharu

Shiota

Interviewed by

Laura Bannister

In the early 2000s, Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota shot to fame for the labyrinthine installations she produces with colored wool, rope, and thread. These supersized, tangled spider webs swallow whole rooms and hold objects captive in midair. Knotted and twisted over multiple days with a team of assistants, her webs are both hopeful hallucinations—inferring the invisible connectivity that pervades all life on earth— and insuperable, brutal obstacles that force audiences to renegotiate how they move through space.

Shiota’s practice is still characterized by these webs but extends to drawing, sculpture, photography, and performance. Her drawings have a hurried, scrapbook quality: faceless people, swirling tornados. Conceptually, she deals in fundamental uncertainties of the human experience such as alienation and displacement,

memory and instability, the chasm between life and death.

I spoke to Shiota—she in her Berlin studio, myself in New York City—in tandem with her solo exhibition at Templon. Signs of Life is her first show in New York City in almost a decade, comprising two colossal threaded immersions, drawings, mixed-media paintings, and freestanding sculptures.

Laura Bannister

In an interview centered on your 2022 exhibition Multiple Realities, you said, “The moment people enter my works, I want them to understand what it is to live and what it is to die.” Your installations in thread and yarn seem to be life-giving and also about endings. They are as much a tangled network of connection points as a giant spider’s web, which itself is an instrument of imprisonment and death. Where do you see the idea of “what it is to die” emerging in recent thread pieces?

Chiharu Shiota

LB

CS

Everyone is going to die; everyone has an end. We know we are going to die, but we cannot feel death every day. But talking about death is thinking of life, and all human existence is thinking about why we exist. My work is actually more about presence, about now. It’s complicated, because I don’t know what death is, but I want to connect it to life.

Many of your works tackle head-on this boundary between death and life. I’m thinking of the fifty-plus life-sized hospital beds climbing toward the heavens in Connected To Life (2021), freestanding doors surrounded by black webbing in Other Side (2013), and a series of lithographs of cells you made in 2020 after starting treatment for ovarian cancer. What is your relationship to death now, having edged toward it in both life and art? Are you afraid of it?

During chemotherapy I was very close to death. I thought a lot about death, and the more I did, the more I wanted to live. I made the installation Light in the Darkness (2022) about this. I put fairy lights in my chemotherapy bags: the light is like breathing. When I was close to death, I wanted to live more; but when the cancer and sickness was gone, I forgot about death and thought about existence. I thought more about society and connection; when I was sick I thought about death and soul. How can I live after death? What is the soul? Now I think more about

LB

CS

LB

how to exist, about society and how to connect with people of all different nationalities. I am not afraid of death. “Life” and “the soul” are different for me: life is about connection, and the soul is more solitary. It is not connected with society but with the universe. The soul is about eternal life after death.

Do you have strong inclinations about what happens to us—our consciousness—after we die?

I believe the soul is connected with the universe. When we don’t have a human shape anymore, we still continue to exist somehow.

At the Brisbane Gallery of Modern Art last year you screened interviews with ten-year-old children. You asked them questions like, “What is a soul?” Did your own conception of the soul shift as you listened to the children’s perceptions of it?

Chiharu Shiota, Connected to Life, 2021, Mixed media, Insallation view from Connected to Life, ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien, Karlsruhe, Germany, photos by Felix Grünschloß

CS

Because I had cancer, I spoke to children of the same age as my daughter at the time. I wanted to know when a mother dies, how can a child feel about the soul? What is the understanding of the soul at this age? There were a lot of good answers. One girl explained that the soul is inherited from other generations and then passed along to others; it is not her soul alone. Also, you cannot see the soul from the outside, but it has a color inside. They were very pure answers. I was surprised.

Can we talk about your exhibition Signs of Life? It includes another large-scale installation with whole books and pages suspended in white thread. According to the show notes, your web takes on another meaning here in that you’re also referencing the Internet as an organism, shared knowledge, and collective memory.

The theme of my work is existence in the absence. Humans are not physically present, but their

LB

CS

existence is. It is about connection through history, across borders and feelings, across all of the human roots that are connected with white string. At funerals in Japan, the dead body is dressed in white cloth. There is also a lot of white paper. I wanted to connect with death and another world. The white thread is like a blank space connected to paper and to books and their information. There is no beginning and no end. It can all go on forever.

Another installation in the show is in red thread. In the middle on the floor are two bronze casts of your own arms. What’s the significance of this gesture?

It’s like my artwork Me Somewhere Else (2018). I feel like my body is somewhere else; my body and my feelings are not exactly connected, but I connect them with string. The bronze remains forever, even after my body dies.

Chiharu Shiota, Light in the Darkness, 2022, bed, chemotherapy bag, fairy light, Insallation view from Invisible Line, ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Denmark

LB

CS

LB

CS

LB

CS

Does your psychological connection to a site shift during the installation process?

The installation is everything I make in the space. It is never the same. It is not like an object which is made at the studio; the artwork is like a three-dimensional painting. I am making a drawing in the air and putting feeling into it.

You’re also showing a series of sculptures: different objects suspended in thread. There is a battered suitcase, monochrome photographs, miniature furniture, tiny bottles, and so on.

They’re all found objects from antique shops or flea markets. When people die, these things remain. The first time I found these old objects was up in the attic of my old studio. I discovered small furniture, little bottles... a newspaper from the ’70s. It felt like there were a lot of memories stored in them. I started to imagine stories about the objects and the people who owned them. I thought about how everyone has a story inside.

Miniatures appear in multiple works of yours, like Connecting Small Memories (2019), which is packed with tiny dollhouse furniture. I remember reading Alice Gregory on miniatures a while back for Harper’s. Her fascination was rooted in gluttony: a hoarding of sensual detail. She also found a thrill in the scale and her comparative bigness in “the masochistic ecstasy of seeing myself as a monster.” What function do the miniatures play for you?

I have collected small objects and miniature furniture for many years. When I had my solo exhibition The Soul Trembles at the Mori Art Museum, I wanted to

create something new. The exhibition space was on the fifty-third floor. When you look out the window, Tokyo looks like a miniature city. I had the idea that I wanted to connect the outside with the inside using all these little objects I’d been collecting. During Covid, I became more fascinated with miniature furniture because we all had to stay inside, looking at the same furniture every day. I wanted to connect our many stories with red thread.

LB

You’ve long been interested in memory and its slipperiness; research suggests we rewrite our memories often. Each time we recall an event, the details shift slightly. Some of our strongest memories can be total fabrications. As someone who is interviewed often, I expect you’re narrativizing your own history a lot, retelling certain beats: the manufacturing company your parents ran in Osaka that produced wooden fish boxes, an early Vincent van Gogh exhibition your mother took you to. Do you ever notice the instability or untrustworthiness of your own memories? Have you ever caught them shifting or recognized they’ve changed?

Humans are physically

Humans are physically

not but not but present present

LB

I noticed my memory changing especially when I started living in Berlin and visited Japan. My memories made Japan more beautiful than it is in reality. When I returned to Japan, I remembered the park where I played as a child very differently. For instance, at the park there was a large concrete mountain. We would try to climb up it, which was hard, and play “Heaven or Hell.” You would either be pulled down to hell or climb up to heaven. But when I returned, the mountain at the park looked so small. Also, when I was little and attending primary school, I would travel on this very long road to school every day. But when I visited Japan for the first time since moving to Germany, the road was so small and short. I continue to create more beautiful memories living far from home.

Do you keep a diary?

CS

My drawings are like my diary. I draw now every day. their existence is.

Chiharu Shiota, Connecting Small Memories, 2021, Mixed media, Installation view from The Soul Trembles, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan

1. Jacques le Goff, History and Memory, trans. Steven Rendall and Elizabeth Claman, Columbia University Press, New York 1992, p. 68

2. Jacques le Goff, ibidem, pp. 68–69.

3. The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments, Authorised King James Version; The Fifth Book of Moses, Called Deuteronomy, 8:11, Collins, London, no publication date.

4. Ibidem, 8:12.

5. Ibidem, 8:14.

6. Ibidem, 9:7.

7. Ibidem, The Book of the Prophet Isiah, 44:21.

8. The town of Vileyka had been made a part of Poland under the Peace of Riga, which followed the PolishSoviet War of 1919–1921. It was re-annexed by the Soviet Union after the Soviet invasion of Poland, which was launched on 17th November 1939.

9. Andrzej Turowski, Budowniczowie świata. Z dziejów radykalnego modernizmu w sztuce polskiej, Universitas, Kraków 2000, p. 222.

10. Ibidem, p. 228.

11. The Holy Bible..., ibidem, The Second Book of Moses, Called Exodus, 20:4.

12. A village in south-east Poland.

13. A town in south-east Poland.

14. Now Lviv, in Ukraine; before the Second World War, the city was part of Poland.

15. ulica – street; when written as part of a street name, the word is not capitalised.

16. Giorgio Agamben, Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive, (Homo Sacer III), trans. Daniel HellerRoazen, ZONE BOOKS, New York 1999, p. 148

17. Situated in west-central Poland, Poznań is one of Poland’s oldest and largest cities.

18. Izabela Kowalczyk, Podróż do przeszłości. Interpretacja najnowszej historii w polskiej sztuce krytycznej, Academica. Wydawnictwo SWPS, Warsaw 2010, p. 237.

19. A city in east Poland.

20. Anselm Kiefer, quoted by Ami Wallach, ‘Der Mystiker, der (noch) nichts in seinem Land gilt: Der Maler Anselm Kiefer’, Esquire, Munich, no.9, 1988, p.94.

21. Anselm Kiefer, Quoted by Markus Brüderlin, in ‘Die Ausstellung Die Sieben Himmelspaläste. Passagen durch Welt(en)-Räume’, in Anselm Kiefer, Die Sieben Himmelspaläste. 1937–2001, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Beyeler, Basel; Osterfildern-Ruit: Hatje-Cantz, 2001, p.33.

22. ‘Generation’ here does not mean a group of individuals on the same rung of the biological ladder; the starting point is the historical reference point of the Shoah. See also Daniel Arasse, ‘La mémoire sans souvenir d’Anselm Kiefer’, in Mémoire et archive. Définition de la culture visuelle IV, conference proceedings from the Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art, Montreal, 2000, pp. 21–32.

23. See Andréa Lauterwein, Essai sur la mémoire de la Shoah en Allemagne féderale (1945–1990), Paris: Kimé, 2005, pp. 19–58.

24. See Clément Chéroux, ‘L’épiphanie négative. Production, diffusion et réception des photographes de la libération des camps’, in Clément Chéroux (ed.), Mémoire des camps. Photographies des camps de concentration et d’extermination Nazis (1933–1999), exhibition catalogue, Paris: Marval, 2001, pp. 103–27. The term ‘machine de désimagination’ was coined by Georges Didi-Huberman; see Images malgré tout, Paris: Minuit, 2003.

25. See especially the study by the political scientist Gesine Schwan, Politics and Guilt: The Destructive Power of Silence, trans. Thomas Dunlap, Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

26. See especially Tilman Fichter, ‘Ungemalte Deutschlandbilder’, in Eckhart Gillen (ed.), Deutschlandbilder. Kunst aus einem geteilten Land, exhibition catalogue, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin; Cologne: DuMont, 1997, pp. 38–47.

27. On Nazi art, see Dieter Bartetzko, Zwischen Zucht und Exstase. Zur Theatralik von NS-Architektur, Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1985; Peter Reichel, Der schöne Schein des dritten Reichs. Faszination und Gewalt des Faschismus, Munich and Vienna: Hanser, 1991; Éric Michaud, The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany (1999), trans. Janet Lloyd, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004.

28. See Hans Belting, The Germans and Their Art: A Troublesome Relationship, trans. Scott Kleager, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998; and Identität im Zweifel. Ansichten der deutschen Kunst, Cologne: DuMont, 1999. Critical studies on postwar German art include: Yule Frederike Heibel, Toward a Reconstruction of Modernism, or the Subject’s Dialectic of Evacuation: Modern Painting in Western Germany After World War II, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991; Martin Damus, Kunst in der BRD, 1945–1990, Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1995; Christos M. Joachimides, Norman Rosenthal and Wieland Schmied (eds.), German Art in the 20th Century. Painting and Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, London and Stuttgart; Munich and London: Prestel, 1985.

29. ‘When I was a student, there was pop art. The Americans relieved us of our duty. They sent us “care packages” and democracy. The search for our own identity was postponed. In 1945, after the “accident”, as we euphemistically call it today, we thought: now we start again from the beginning. Right up until today we talk of zero hour, although such a thing cannot exist, it’s absurd. The past was made taboo, and anyone who brought it up met with denial and disgust.’ Kiefer in Jacqueline Burckhardt (ed.), Ein Gespräch. Joseph Beuys, Jannis Kounellis, Anselm Kiefer, Enzo Cucchi, Zurich: Parkett/Cantz, 1994, p. 40.

30. Kiefer in 1996: ‘I think that postwar trends (minimalism, abstract expressionism etc.) and research done on painting techniques (Turoni, Buren and others) have been very interesting, but as far as I’m concerned, we can’t stop there. Take the works of Carl Andre: they are very

powerful, but in time they have become design. It’s a style you see everywhere, in museums, in apartments, whereas before it was revolutionary. I’m not criticizing its originality—it’s important to pass through that stage— but now we have to synthesize all this research, My aim is not to revolutionize the history of art. Wanting to change paintings—that is a matter for art history, whereas personally I would prefer to change something in the history of the world. But what exactly, I don’t know. If I did, I’d be a politician.’ Interview with Bernard Comment in 1996, Anselm Kiefer, Cette obscure clarté qui tombe des étoiles, Art Press, no. 216, September 1996, pp. 24–25.

31. See Daniel Arasse, Anselm Kiefer, p. 49, and Matthew Biro, Anselm Kiefer and the Philosophy of Martin Heidegger, Cambridge: CUP, 1998, pp. 164–72.

32. Quoted by Markus Brüderlin, ‘Die Ausstellung Der sieben Himmelspaläste’, p. 33.

33. See Paul Celan, Der Meridian. Endfassung. Vorstufen. Materialen, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1999, p. 166.

34. The controversy sparked off by the depiction of these evils led to two different schools of thought. On the one side were the reactionaries, consisting of collectors who praised these works for their straightforward restoration of Germanic folklore and of German figurative painting. On the other were the progressives, who recognized in them a strategic device that aimed to revive the debate over repressed memory and to understand the mechanisms that had made Nazism so fascinating. The latter hoped that these ‘banned images’ would have a cathartic effect, as they seemed to encourage the development of a ‘post-traditional’ identity, as Habermas put it, since they demanded that the observer should preserve the ambivalence of their emotional effect. Between these two very different positions, the reactions of the general public and most of the press, who believed that the subject of a work of art inevitably reflected the political opinions of the artist, were negative or even phobic, showing all too clearly the delicate nature of symbolic links with the Nazis. For a good analysis of these different positions, see the journal Kunstforum international: Transformation und Wiederkehr. Zur künstlerischen Rezeption nationalsozialistischer Symbole und Ästhetik, no. 95, June-July 1988.

35. Petra Kipphoff, ‘Die Lust an der Angst—der deutsche Holzweg’, Die Zeit, 6 June 1980. For an account of Kiefer’s reception in his own country, see Sabine Schütz, ‘Das “Kiefer-Phänomen”. Zu Werk und Wirkung Anselm Kiefers’, in Eckhart Gillen (ed.), Deutschlandbilder, pp. 584–91.

36. See Saul Friedländer, Reflections of Nazism: An Essay on Kitsch and Death, trans. Thomas Weyr, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1993.

37. Quoted by Ami Wallach, ‘Der Mystiker, der (noch) nichts in seinem Land gilt’, p. 94.

Main Essay

The Sticky Spot of Crime, Władysław Strzemiński, 1945, To my Friends the Jews

Rothko Chapel interior, Mark Rothko, Eid Al Adha, 1972,photo by Hickey Robertson

Let the Artists Die, Tadeusz Kantor, 1985, La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club, New York

Wielopole, Wielopole, Tadeusz Kantor, 1980, Cricot 2 Theatre, club Stodoła, Warsaw, Poland, photo by Adam Hayder

I Shall Never Return, Tadeusz Kantor, 1990, Cricot 2 Theatre, club Stodoła, Warsaw, Poland, photo by Aleksander Jałosiński

Wenn der Frühling kommt, Luc Tuymans, 2007, Portfolio with 17 digital pigment prints on semi-transparent paper, mounted on sheets of rag paper, 19.7 × 15.7 in. (50 × 40 cm.)

für Paul Celan, Anselm Kiefer, 2006, Oil, emulsion, acrylic, branches, metal, wood, and chalk on canvas mounted on board, 110.2 × 224.4 × 19.7 in. (280 × 570 × 50 cm.)

I Accuse the Crime of Cain and the Sin of Ham, Władysław Strzemiński, 1945, To my Friends the Jews

Anselm Kiefer

Die Himmelspaläste, 2003–18, reinforced concrete and lead, installation view, La Ribaute, Barjac, France. Overall dimensions variable. Photo: Charles Duprat

Sol Invictus, 2007, Emulsion, shellac, oil, and chalk on linen canvas, 401.6 × 173.2 in. (1020 × 440 cm.)

Die Orden der Nacht, 1996, Emulsion, acrylic, and shellac on canvas, 140.2 × 182.3 in. (356 × 463 cm.)

Die berühmten Orden der Nacht, 1997, Acrylic and emulsion on canvas, 202.4 × 198 in. (514 × 503 cm.)

Mésopotamie, 2007–20, Ensemble of 15 paintings, Installation view from La Ribaute, Barjac, France

Nürnberg, 1986, Oil, straw, and mixed media on canvas, 110.4 × 149.9 in. (280.4 × 380.7 cm.)

Heavy Cloud, 1985, lead and shellac on photograph, mounted on board, 23.4 × 34.5 in. (59.4 × 87.6 cm.)

Black Flakes (Schwarze Flocken), 2006, Oil, emulsion, acrylic, charcoal, lead books, branches, and plaster on canvas, 129.9 × 224.4 in. (330 × 570 cm.)

Brünnhilde/Grane, 1982–93, Woodcuts and acrylic on cut and pasted papers, mounted on canvas, 106.3 in. × 96.5 in. (269.9 × 245.1 cm)

Böhmen liegt am Meer (Bohemia Lies by the Sea), 1996, Oil, emulsion, shellac, charcoal, and powdered paint on burlap

75.2 in. × 221 in. (191.1 × 561.3 cm)