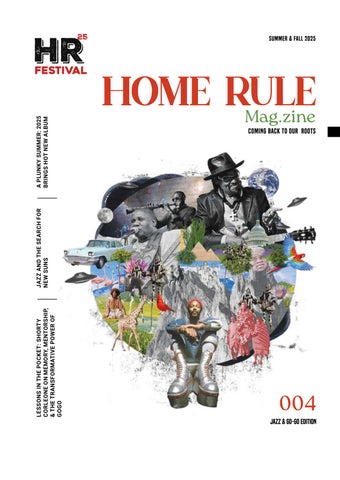

HOME RULE ZINE

SUMMER & FALL 2025

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF & ART DIRECTOR

St. Clair Castro-Wright Jr.

CREATIVE MANAGER & MANAGING EDITOR

Briona Butler

PUBLISHER

Home Rule Music Foundation

PRINTER

Heritage Printing

ASSISTANT EDITORS

Briona Butler, Jamari Tyree, Charvis Campbell

SPECIAL CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Jackson Sinnenberg

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Briona Butler, Jamari Tyree, Phillip Kulubya, Kendall Bryant

04. Editor‘s Letter 05. 2025 Sponsors 06. 2025 Perform-

ers 08. Home Rule Music Festival Marks Year 4 with a New Generation, Rooted in Rhythm 14. The Go-Go Museum & Café’s Crankin Collection 18. RHYTHM TACTICS: A Go-Go Archive for Now Playlist 20. Lessons in the Pocket: Shorty Corleone on Memory, Mentorship, and the Transforma-

tive Power of Go-Go

Long Live Go-Go

CapitalBop at 15: Still ‘taking care of us’ TABLE OF CONTENTS

Jazz and the Search for New Suns

A Plunky Summer 40. Don’t Mute

Turns Up the Volume in 2025

Letter From The Editor

Even before we put out the very first issue of Home Rule Magazine in June 2022—timed to the inaugural Home Rule Music Festival—we knew this wasn’t going to be a one-and-done situation. The work felt too necessary. Telling D.C.’s music stories, documenting our vinyl culture, and spotlighting local creative voices wasn’t just something cool to do—it was a cultural responsibility. Especially in a city where gentrification tries to pave over memory, where venues disappear, and history gets forgotten in real time.

With every issue since, we’ve aimed to sharpen that mission, and this edition might be our most rooted one yet. You’ll find threads of legacy and future throughout—from the stage to the page. Writer Jamari Tyree opens with a look at what year four of the festival means, with a new generation stepping into the spotlight. Our Youth Showcase isn’t just an opener—it’s a message: the rhythm is alive and well, and it’s already in good hands. Briona Butler delivers twice with her powerful interview with Shorty Corleone—on mentorship, memory, and the staying power of Go-Go— and with “Rhythm Tactics,” a playlist/archive made for this exact moment in time. Phillip Kulubya takes us inside the Go-Go Museum & Café’s Crankin Collection and gives us a ride through a Plunky summer, while Jackson Sinnenberg puts CapitalBop’s 15-year history into context as one of the city’s most vital incubators for boundary-pushing jazz. This issue celebrates what Go-Go was and is—and what it continues to do for the people who grow up in its pocket.

It’s a genre, a heartbeat, and a spiritual language spoken only by those who’ve sweated it out at Mad Chef, Neon, The Black Hole, Cuzco’s, and Gee’s Nightclub. I was there. Nights with UCB, TCB, Fatal Attraction, Raw Image, and of course, Backyard Band—those were my rites of passage. If you know, you know.

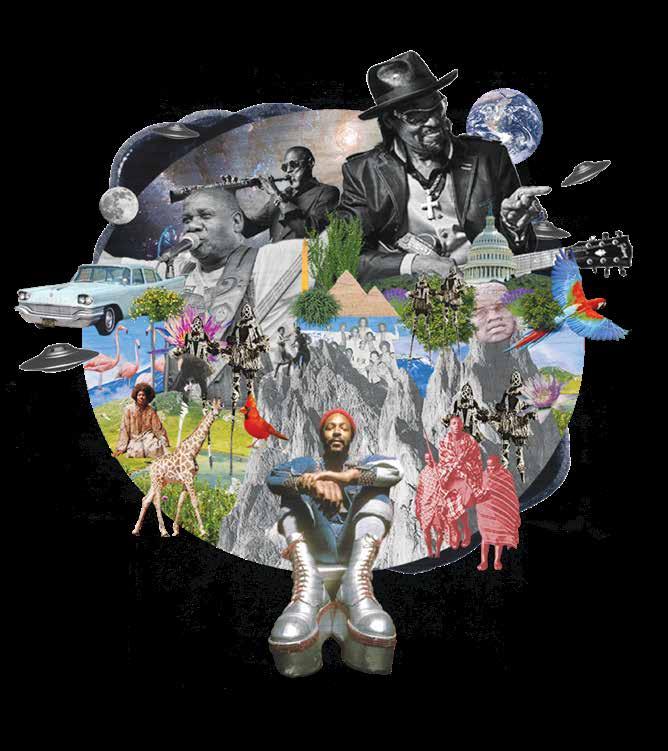

Go-Go wasn’t born in a studio. It came out of the crowd, out of call-and-response, out of grit and syncopation and joy. It grew from jazz and funk, morphed through hip-hop, and kept adapting. Like D.C. itself. And like all the music I love— whether we’re talking Pink Floyd, Cymande, Mort Garson, Sun Ra, Gato Barbieri, Carlos Santana, or any of the soulful, psychedelic, or off-kilter sounds I keep in rotation—Go-Go stands as a testament to freedom and movement. That’s what this magazine is too.

Elsewhere in the issue, Jamari returns with “Long Live Go-Go,” Kendall Bryant expands the scope with an exploration of Afrofuturist jazz in Jazz and the Search for New Suns, and Phillip closes out strong with “Don’t Mute DC Turns Up the Volume in 2025”—a reminder that this movement doesn’t end on stage or on wax. It lives wherever the people gather and play it loud.

There’s nothing passive about our music. There never was. And Home Rule—both the magazine and the festival—exists to turn it up, keep it documented, and pass it on.

So dig into this issue, spin something wild, and stay funky.

St.Clair Castro-Wright Jr.

2025 PERFORMING ARTISTS BACKYARD BAND

PLUNKY & THE ONENESS

IMANI GRACE-COOPER

FARAFINA KAN ENSEMBLE

JOANTZ: PRODUCER SHOWCASE

ARTISTS ONENESS OF JUJU

ENSEMBLE

PARKS AT WALTER REED

ALETHIA TANNER PARK

Home Rule Music Festival Marks Year 4 with a New Generation, Rooted in Rhythm

By Jamari Tyree

TOMORROW‘S SOUND HONORS YESTERDAY‘S SPIRIT

AT THE 2025 HOME RULE MUSIC FESTIVAL

THE BEAT OF CHOCOLATE CITY

Music is a huge part of showcasing the roots of where we originate by creating a significant sound that only we as a people are aware of, sharing it with the world surrounding us, and embracing the legacy and culture that come with celebrating music. For the District of Columbia, Go-Go music is more than a sound—it’s the city’s pulse through generations.

Washington, D.C.’s “Chocolate City” moniker reflects its long-standing role as a Black cultural hub. With its infectious rhythms and call-and-response vocals, Go-Go music is inseparable from D.C.’s identity. While George Clinton popularized the nickname “Chocolate City,” it was Chuck Brown, the “Godfather of Go-Go,” who birthed the sound in the mid-1970s: an infectious blend of funk, jazz, Latin rhythms, and gospel. It is a sound you don’t just hear; you move with it.

At its core is the “pocket”—a hypnotic, percussive rhythm born of Black, southern church music and sustained by the crowd.

Chuck Brown and the Soul Searchers built a groove meant to last beyond the night, keeping our people dancing until tomorrow came.

In this groove, “Chocolate City” became more than a name. It became an anthem—a city with Black mayors, a Black-majority council, and a 70% Black population. Go-Go captured our joy, our hustle, and our pride. It was the soundtrack of self-determination, a cultural claim on the city we made our own.

www.windmeupchuck.com

LEGACY CARRIES: FROM CHUCK BROWN TO BACKYARD BAND

Brown wasn’t alone. Rare Essence, Trouble Funk, Experience Unlimited (E.U.), and the Young Senators—these bands turned Go-Go into a movement. Songs like “Bustin’ Loose,” “Pump Me Up,” “Da Butt,” and “Overnight Scenario” became more than party anthems. They were declarations of identity and power, echoing through neighborhoods and across national stages like Spike Lee’s School Daze.

Go-Go wasn’t just a sound. It was—and still is—a “cultural ecosystem.” Dr. Natalie Hopkinson, curator of the Go-Go Museum & Café and author of Go-Go Live, explains: “Go-Go is a collection of Black businesses. It’s a huge industry in this area, especially at its height in the ‘80s.” It fueled an entire economy of musicians, managers, promoters, radio stations, and entrepreneurs.

Clothing brands like Madness, HOBO, All Day, and Shooters, for instance, created what we know today as the urbanwear industry. Streetwear rooted in sound, place, and perspective: “People here protected their businesses,” Dr. Hopkinson notes. “They weren’t interested in having it taken over by someone else.”

Each generation has brought something new to the beat. The ‘90s gave us Backyard Band and Northeast Groovers, who layered in gritty, hip-hop-infused styles. The bounce beat—introduced in the early 2000s—kept Go-Go evolving, keeping it alive in the hearts of younger audiences even as D.C. changed around us.

Chuck Brown playing guitar on rooftop in Washington D.C.

Photo Credit:

BLACK WOMEN: THE HEARTBEAT OF THE BEAT

And let’s be clear: Black women have always been the heartbeat of Go-Go. “There’s not Go-Go without women,” says Dr. Hopkinson. From vocalists and instrumentalists to “Mom”-agers and promoters, women have shaped the scene. Annie Lee Mack managed Rare Essence. From Pleasure to Be’La Dona to Takesa “KK” Donaldson, their determination, love, courage, and talent keeps our legacy alive. Through innovation and her archival research, Dr. Hopkinson herself remains a purveyor of the rich and particular artistry and sites of memory at which the women of Go-Go culture abide. Despite being under-recognized, Black women were—and are—central to the sound that has shaped our way of life.

#DONTMUTEDC: WHEN RHYTHM BECAME RESISTANCE

To be Black and from D.C. is to have our identity tested by racism, gentrification, policing, and cultural erasure. In 2019, when a MetroPCS store in Shaw was told to stop playing Go-Go from its loudspeakers, the community erupted. #DontMuteDC was born. Bands took to truck beds and protest marches, transforming rhythm into resistance and joy into justice.

“The music came together to protect that business,” says Dr. Hopkinson, “but also pushed for broader policy change—education, health, and criminal justice. Go-Go artists gave voice to every aspect of life in Chocolate City, and policymakers were compelled to listen.”

In 2020, Go-Go was named the “official music” of Washington, D.C., a legislative nod to a truth we’ve always known. That February 19th was a win for the genre and for the soul of Chocolate City: a city defined not by proximity to political power but by allegiance to Black culture, autonomy, and creative legacy.

Bel’a Dona Band

Photo Credit: Folklife.si.edu

ROOTED IN RHYTHM: THE FUTURE OF GO-GO

Today, Go-Go remains. It bridges the past, present, and future.

The 2025 Home Rule Music Festival proves this. Born from a commitment to keep D.C.’s Black musical legacy alive, the festival is an annual, multi-day celebration of music, art, food, and community joy.

Year 4 kicks off on June 13 with the festival’s first-ever youth showcase—“Rooted in Rhythm”—at the Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company. Young musicians from Girls Rock! DC, Let’s Go-Go Band, Soul of SEED, and the Washington Youth Choir take the stage, guided by Go-Go legend, now-radio personality, and Professional Mentor Charles “Shorty Corleone” Garris. “I think we’re heading in the right direction.”

Day 2, on June 21, moves the celebration to The Parks at Walter Reed in Takoma. In quintessential Home Rule fashion, the outdoor gathering pulses with vinyl vendors, local eats, vibrant apparel, Black art, and—of course—the living, breathing sound of GoGo. Here, past and future stand side-by-side. This summer, Backyard Band delivers the steady heartbeat of the culture, while New Impressionz electrifies the stage with a fresh spin on the classic pocket—preserving the tradition and reinventing it with every beat. They’re joined by a dynamic lineup: the legendary saxophonist and funk visionary Plunky; soulful singer-songwriter Imani-Grace Cooper; the powerful percussion and movement of Farafina Kan Ensemble; and a curated Joantz Music Producer Showcase. Together, they honor the legacy, elevate the moment, and carry Go-Go’s spirit into tomorrow.

Crowd Celebrating at Moechella in 2019

Photo Credit: Akil Ransome / Courtesy of Long Live Go-Go

We're in your corner.

People today can spend nearly half their lives over the age of 50. That’s a lot of living. So, it helps to have a wise friend and fierce defender like AARP in your corner and in your community so your money, health and happiness live as long as you do.

AARP offers custom tools, resources and local expertise here in the District to help you achieve your goals and stay connected.

Find us at aarp.org/dc.

/aarpdc @AARPDC

The Go-Go Museum & Café’s Crankin’ Collection

The museum utilizes new technology and its many supporters to celebrate Go-Go’s history

By: Phillip Kulubya

On any Saturday afternoon, you’ll see people from all walks of life stepping through the doors of the Go-Go Museum & Café. Some visitors come from as far away as California, while others live just a short walk from the museum in Washington, D.C.’s Anacostia neighborhood. Since its opening on Feb. 19, 2025, the museum has welcomed students, musicians, and longtime Southeast D.C. residents.

But what exactly draws so many to this new cultural hub?

With 16 interactive exhibits and a growing archive of GoGo artifacts, the museum has quickly become a must-see for Go-Go fans and curious visitors alike.

Go-Go music—a percussion-heavy genre indigenous to D.C.—has echoed through the city’s airwaves and streets for decades. Yet, unlike other musical genres, it lacked a dedicated museum. That’s where founder and CEO Ronald Moten came in. In 2009, the Go-Go promoter and activist announced plans for a Go-Go museum during a speech at the Go-Go Awards, an event he produced alongside

members of the local music community.

By 2019, Moten began calling on friends, associates, and fellow Washingtonians to contribute artifacts. “I really didn’t have a lot of old memorabilia other than pictures,” Moten said. “I wasn’t thinking to save it. I’ve moved so many times—it’s hard to hold on to stuff.”

Still, Moten donated several key artifacts of his own. Over the years, he’s worked closely with some of the genre’s biggest names. Among the items he contributed is an obituary program from the funeral of famed trumpet player Anthony “Little Benny” Harley, who passed away in 2010. Little Benny rose to fame with Rare Essence in the 1970s before founding Little Benny & the Masters in the ’80s.

Moten also donated a DVD of the 2003 Go-Go Live Health & Stop the Violence Concert, which he co-produced. The concert included performances by rapper 50 Cent and Go-Go bands like Backyard Band and TCB (Take Control

Band). Both the program and DVD are displayed in a glass case on the museum’s lower level.

In February 2020, the Maryland radio station WGPC 95.5 FM teamed up with Don’t Mute DC and the museum for a telethon fundraiser.

Dr. Natalie Hopkinson, the museum’s chief curator, was deeply moved by the event’s community response. “It seemed real,” Hopkinson said. “It wasn’t just some idea— somebody running their mouth. There was an outpouring of people all day long, coming up and giving money. They also started offering their artifacts and offering to donate.”

A longtime Go-Go advocate, Hopkinson has chronicled the genre as both a journalist and academic. Her 2012 book Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City traces the music’s roots and cultural legacy. Before joining the museum, she also contributed artifacts to the D.C. Public Library’s Go-Go archive.

“People have just been really great about wanting to donate their materials,” she said. “It’s all been very organic—rooted in our personal connections and networks. From there, it’s just grown.”

Journalist Alona Wartofsky, who has covered Go-Go since the 1980s, is among the many friends of the museum who’ve contributed to its collection. She donated a Rare Essence T-shirt from the ’80s that reads, “I’m an Inner City Groover,” a nod to the band’s nickname. She also shared a 1984 promotional shirt for Chuck Brown & the Soul Searchers, created to promote their single “We Need Some Mon-

ey.” Chuck Brown—revered as the “Godfather of Go-Go”— created the genre in 1976.

One of Wartofsky’s favorite items is a black button-down shirt that belonged to Brown, donated by Becky Marcus of Liaison Records.

“I liked looking at that because it just reminded me of the way Chuck was and how he dressed,” Wartofsky said. “He always had charisma—this flair.”

Another standout artifact is DJ Kool’s varsity jacket, commemorating his 1996 hit “Let Me Clear My Throat,” which went platinum in 2023. The jacket, donated by DJ Kool in 2024, is a prized addition for Moten and Hopkinson. Since its opening, the museum has gained attention for its innovative technology—including AI-powered holograms of Anwan “Big G” Glover (Backyard Band) and Gregory “Sugar Bear” Elliott (Experience Unlimited). Visitors can interact with the holograms by asking them questions about their careers and Go-Go’s evolution. The tech is powered by TimeLooper, a company specializing in immersive exhibition design.

Before the museum opened, Moten emphasized the need to engage young people. “We want to get young people into it,” he said. “It has to be interactive. We want to reach more people. Not everybody has the patience to sit and read.”

One of the most visited features is the Go-Go Meets HipHop exhibit, which plays jam sessions, D.C. rap tracks, and hits that sample Go-Go. A crowd favorite: Nelly’s 2002 chart-topper “Hot in Herre,” which samples Chuck Brown & the Soul Searchers’ “Bustin’ Loose.”

Downstairs, touchscreen exhibits like the Go-Go Family Tree allow visitors to trace the genre’s history—from Chuck Brown’s founding to future-forward bands like youth group Pock3t.

Many musicians, creatives, and scholars contributed to the museum’s content, including Darryl Brooks, Boogie Proctor, Sugar Bear, Alona Wartofsky, Charles C. Stephenson Jr., and more.

Stephenson, an author and former manager of Experience Unlimited, is excited about what’s ahead. “I think whatever they do in the future is going to be forward-leaning,” he said. “It’s going to be creative. And they’re going to use technology to educate and to share the story of the music—which I applaud.”

"It has to be interactive. We want to reach more people. Not everybody has the patience to sit and read.”

The Greg “Sugar Bear” Elliott AI-powered hologram and the Experience Unlimited exhibit at the Go-Go Museum & Café. Nov. 18, 2024.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Sam Johnson III / SamJohnson3 Photography

Lessons in the Pocket:

Shorty Corleone on Memory, Mentorship, and the Transformative Power of Go-Go

Interview By: Briona Butler

Introducting Shorty Corleone

Briona Butler:

Introduce yourself to the audience. Tell us who and what you are to Go-Go.

Shorty Corleone:

I’m Shorty Corleone—artist, ambassador, producer, Washingtonian, GoGo artist, and radio personality.

how Crank Radio, and radio in general, help keep Go-Go alive.

SC:

Crank Radio started during the pandemic with myself and Rico Anderson. While everything was shutting down, the #DontMuteDC movement helped birth the idea.

The Rise of crank radio

BB:

What is Crank Radio? How did it come to be, and how long have you been doing it?

Tell us a bit about the format and

Don Campbell—WHUR’s Don from Ground Zero—was instrumental in getting us over to SiriusXM. He knew what we were doing with the GoGo broadcast at the phone store on 7th and Florida Avenue, and WHUR caught wind of it.

We got the first call from SiriusXM in the fall—September or October—and another in December. They wanted episodes ready before the holiday break, so by December 23–24, we were in production mode.

Shorty Corleone (On Right)

Photo Credit: UNKNOWN

The wild part? I had just recovered my voice after a bad case of bronchitis. I literally couldn’t speak. My first time using my voice again wasn’t in front of 300 people at a GoGo show—it was for 30 million listeners on SiriusXM. That was major—not just for me, but for the culture.

Eventually, Rico’s schedule got packed with national projects, so I kept the show going. It evolved into Crank with Shorty Corleone. Two years ago, we got picked up on the terrestrial side of WHUR. Now we’re on FM, too.

Go-Go’s Global Future

BB:

What role does Crank Radio play in shaping the future of this genre for new listeners across the globe?

SC:

We are going to be the leading contributor to Go-Go music worldwide.

“My first time using my voice again wasn’t in front of 300 people at a Go-Go show—it was for 30 million listeners on SiriusXM.”

Rare Essence and Go-Go’s Golden Era

BB:

As someone who helped shape Rare Essence’s sound, what memories stand out as defining moments—on stage or in the community—that captured the spirit of D.C.?

SC:

When I joined, I brought a hip-hop melodic pattern into the band. I had a background in classical and R&B vocals, but I loved hip-hop, so I blended those influences.

If you listen to tracks like “Work It,” “The Heart,” “Overnight Scenario,” “Body Snatchers,” and “Call My Name,” you can hear how I adjusted my style to elevate each song. It was about fitting what the record needed.

At the time, I had just returned from a failed label deal in New York. I remember thinking, If I can’t make it in my own city, forget it. Then I got invited to a Rare Essence session. It wasn’t even a formal audition—just singing on a few tracks. Those songs ended up becoming classics. The chemistry was real.

On Band Chemistry and Personal Energy

BB:

How would you describe your energy within the band? Were you “the diplomat,” “the funniest,” “the most energetic”?

A Message to Emerging Artists

SC:

I’ve been called “the diplomat” because of how I respond to people. Some even said I should run for mayor! [laughs] But honestly, I didn’t have a master plan. I just supported whatever was needed and stayed ready. I was the youngest in the band, so I learned from the system they had in place. It was fast-paced: come prepared, knock it out, and move on. I respected that.

I didn’t even realize I was adding something unique. I just brought my energy and did the work.

BB:

What would you say to artists who feel like D.C. doesn’t have the infrastructure to uplift their work— and that they have to leave in order to succeed?

SC:

It’s a big world out there. Home will always be home, but don’t limit yourself. Go out, get your “Walmart notches,” as I call them—those lessons from the road.

D.C. is a performance town. If you want to build your stage hours, it’s the perfect place. But if you’re trying to break into the music business, you might need to be closer to radio stations or music executives.

RIGHT: Rare Essence Band with Shorty Corleone Photo Credit: UNKNOWN

The city’s evolving, though. I see D.C. becoming what folks always hoped it could be beyond politics. There are more opportunities now, but artists still need to explore. Travel. Learn. Try. Fail. Repeat.

Lessons for the Next Generation

BB:

What lessons—musical, personal, or political—do you hope this generation carries forward?

Mentorship and Legacy

BB:

What does it mean to you to be mentoring young musicians right now? How did you start as a bandleader for Let’s Go-Go Band?

SC:

You never know who’s in the room. I talk about that all the time. Conduct yourself with care, because someone’s always watching or listening.

I try to offer positive energy and meaningful feedback— and remind young people that 90% of the music they listen to has Go-Go influence. Once they understand that, they find their own lane within what we’ve built. Even the skeptics start nodding their heads like, “OK, let’s do this.”

This generation excites me. To be able to give back in this way is truly an honor.

SC:

Education. Preparedness. Eagerness. Persistence. Seriousness.

I tell them: you are a business. And if someone spends their time to come see you perform, you owe them your best. Respect yourself and respect the moment. Carry yourself like you belong in the room—because you do.

Reclaiming Space Through Go-Go

BB:

Go-Go has moved from erasure to national recognition. How do you see today’s youth reclaiming that space and rewriting the genre’s legacy?

Final Thoughts: The Power of Go-Go

SC:

We’re moving in the right direction. Social media helps— the energy travels. And the music education programs in schools are a game changer. These students are building muscle memory. They’ll carry it with them into high school, college, and beyond.

That’s how Go-Go started—in jam sessions, in high schools, on street corners. That raw creativity is making a comeback.

We just need to hold space for it. Play the beat. Spark the excitement. The culture will do the rest.

BB:

What do you want the world to understand about the power of Go-Go?

SC:

It’s a force. It’s coming. And it will always be a part of American music history. But the best? The best is yet to come.

Tune in!

You can listen to Crank Radio every Saturday and Sunday at 10 PM on SiriusXM HUR Voices (Channel 141) and Saturday nights at midnight on WHUR FM.

More stations to be announced in 2025.

Dr. Frances Toni Draper Publisher & CEO

Jazz and the Search for New Suns

By: Kendall Bryant

“‘Good music they have here,’ he remarks, drumming the table with his fingertips.

Music! The great blobs of purple and red emotion have not touched him. He has only heard what I felt.”

Zora

Neale Hurston, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” (1928) (emphasis mine)

If the blues is best understood as a “way of life,”1 as James Baldwin suggests, so is its child, jazz. Like its mother, jazz is not merely a way of playing instruments or a genre ripe for commodification. It is a means of moving and dancing, storytelling, conversing, and being in the world with the knowledge that “there is no way not to suffer.”2

Though jazz, as we know it today, spans cultures, we must never forget that the style was originally alchemized by the specific intergenerational struggle of Black Americans. Jazz and the art forms that came before it began as sites of resistance and togetherness for communities who endured the threat of lynching, laws that restricted their

movement, and exploitation in factories and on plantations. The blues and jazz are a part of a wider Black American tradition of “making a way out of no way,” or exercising agency in the most impossible of conditions. But Baldwin says it best when he notes that the blues (and thus, jazz) come from “this ability to know that, all right, it’s a mess, and you can’t do anything about it... so, well, you have to do something about it.” 3

While they are branches on the same tree, jazz and

1 James Baldwin, “The Uses of the Blues” (1964)

2 Ibid.

the blues have their distinct characteristics. As a musical style, the blues follows a standard form4. Without getting too deep into the weeds, it’s typically shaped around 12 bar segments with 3 chords that revolve around the 1st, 4th, and 5th notes of an 8-note scale. Additionally, the lyrics follow an AAB form where a phrase is repeated twice before a new one is introduced. This style was a capacious

vessel for Bessie Smith’s crooning about the flood that washed her home away5, Ma Rainey’s indignant tale of running away from her home6, and Billie Holiday’s honest reflections about loving her man but being ready to leave him and his controlling ways7. The blues’ consistency as a musical style reflects its larger role as an anchor and a life raft in Black American life. It gave its people another gram-

mar to speak and live by, catalyzing its own revolution with shared language. Conversely, jazz is all about the making of form through the breaking of form. It is a method for inventing new languages out of old ones in pursuit of the most free way to express an idea. It is a poignant representation of Octavia Butler’s point that, “There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.”8 In its unquenchable quest to find new “suns” — concepts, chord progressions, instrumental arrangements, time signatures,

feelings to both channel and evoke — jazz is one of our best guideposts for the meaning of “innovation” itself.

Poet and music critic A.B. Spellman, a friend of many jazz musicians including John Coltrane and Miles Davis, lays it out very clearly in his interview with the podcast Poetry Off the Shelf:

Ma Rainey and her Georgia Jazz band in 1923

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Micheal Ochs

Jazz had historically developed with certain specific canons. You had the New Orleans canon, then you had the Stride canon, and the Swing canon. And you had the Bebop canon. And I think it was [Ezra Pound] who talked about everything being controlled by a sort of academy that had rules and laws about how art was to be made. And then you’d get a bunch of revolutionaries against that canon and they would eventually break it. Then the art would be very new and very exciting. And there’d be a lot of innovation going on all over. And that would eventually ossify into another canon and another academy and the cycle would start again. Because you’re gonna get some people who want to say, ‘No, no, I want to be freer than that.’9

And so jazz, as a musical form and mindset, is fueled by a revolutionary drive for liberated expression. It is at once a laboratory and a playground for the creation of nimble structures that can allow us to faithfully share and explore the labyrinths of our innermost worlds. If human freedom depends on “the restructuring of the mind” and “new modes of poetic action, new networks of analogy, new possibilities of expression”10 as author Paul Garon writes, jazz may be one of our greatest tools for its cultivation.

From: City Blossoms

City Blossoms cultivates the well-being of our communities through garden-based learning and creative programming in kid driven gardens. Join us for Open Time, our free, dropin garden program where all ages can explore, create, and grow together. No registration needed! Scan QR code.

Become a volunteer! Groups and individuals welcome. More info here: (All experience levels welcome)

Learn more at www.cityblossoms.org Follow us: @cityblossomsdc

I first felt the power of jazz music at the end of Shayla’s dance class, hearing the bouncing, delicate notes of Duke Ellington’s piano in the beginning of “In a Sentimental Mood” as it fell and rose like a sea of stars.

At the time, I was 10 years old and miserable with a body that bloomed much sooner than my peers. I was tall and full breasted with a little more meat on my bones than the others and tiger-stripe stretch marks to match. I had no time to understand the rapidly changing landscape of my body, only the feeling of greedy eyes wandering my little curves and the fear they planted in the pit of my stomach. Confused, afraid, and paralyzed

by my self-consciousness, I could count on one hand the amount of times I passed a mirror without shedding a tear. But then there was Shayla, a tall, slender, copper-skinned woman who must’ve been in her early to mid-twenties when she casually changed my life.

I came to her in a forest green leotard with brown tights a little lighter than my skin and two or three sports bras layered tightly on my chest. With her warm spirit and kind eyes, she held my hand and showed me sanctuary in the mirrors of the dance room in the Bowie Community Center.

AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS - OCTOBER 27: singer Jeanne Lee performs live on stage at Meervaart in Amsterdam, Netherlands on October 27 1984 (photo by Frans Schellekens/Redferns)

The room was dimly-lit, but I remember Jill Scott’s voice coloring every corner of the room golden as Shayla shepherded us across the tan floors in joyful movement.

Me and the other girls, all of us earth-toned variations on a theme, kicked our legs high up in front of us to show off our battements like little Rockettes.

And we conjured all of the grace and momentum we could muster to fly across the room with our grand jetés. Then we all galloped to the barre and watched closely as Shayla showed us how to place our feet in first, second, third, and fourth positions. With every kick and plié, I felt my armor and despair dissolve. I became more than an object for ogling. In Shayla’s class, my body was mine.

I remember feeling proud and weary by the time Shayla would turn on the cool down music and guide us through deep stretches. This is the moment when I first met Ellington and Coltrane. I didn’t know their names at the time, just the way each moving part of the song made everything make more sense. The song was very different from any of the early 2000s Pop and Neo-soul I was accustomed to hearing in the backseat of my mother’s truck, but it still sent shockwaves through me. With my eyes closed, letting myself get lost in the drama of every passing phrase, I felt my form and everything I thought I was slipping away.

In an unexplainable way, I found myself in the shape of the melody and all its moving parts: the saxophone’s gritty sweetness, the piano’s effervescent melancholy, and the marriage of them falling over and under one another to the hush of the drum. And from that moment on, jazz has become the soundtrack of my own personal revolution. A vehicle for my pursuit of new suns.

3 Ibid.

4 Understanding the 12 Bar Blues

5 Bessie Smith, “Backwater Blues

6 Ma Rainey, “Runaway Blues”

7 Billie Holiday, “I Love My Man”

8 Epigram from unreleased novel Trickster by Octavia Butler

9 Poetry off the Shelf podcast, “Where I Live”

10 Paul Garon, Blues and the Poetic Spirit (1975)

A Plunky Summer

Summer 2025 brings warm weather and a hot new album from Plunky

By: Phillip Kulubya

Summer 2025 is set to be an exciting time for jazz saxophonist James “Plunky” Branch and his many adoring fans. The jazz legend’s summer schedule includes Plunky Day, the 2025

Home Rule Music Festival, and the release of Plunky & The Oneness of Juju’s new album, Made Through Ritual. Since founding the Afro-jazz group Plunky & The Oneness of Juju in 1971, the saxophonist has left a lasting imprint on the music world—as both a performer and a record label CEO.

The Richmond, Virginia native has built a global fanbase, thanks in large part to classics like 1977’s “Every Way But Loose,” which found particular success in London. Plunky is also the CEO of N.A.M.E. Brand Records, through which he has released 30 albums.

In 1975, Plunky co-founded the influential Black Fire Records with the late DJ and producer Jimmy Gray. Based in Washington, D.C., the label became known for pivotal releases, including Plunky & The Oneness of Juju’s African Rhythms (1975). In 2019, Plunky licensed Black Fire’s catalog to London-based Strut Records to reissue the label’s archive and share its music with new generations.

“ They were chosen to do this because they have a habit and a tradition of honoring the original intent of those recordings,” Plunky said. “They put each one out with extensive liner notes and the history of the label and the acts they included.” Strut Records will release Made Through Ritual on July 11, 2025. With this album, Plunky returns to his jazz roots. Over the years, his sound has fused jazz with R&B, funk, and blues. Now, he offers something more elemental.

Plunky Live in Concert:

Photo Credit: Unknown

“Compared to my recent recordings—recent being over the last 20 years—this is, in some ways, a throwback. If I had to characterize it, it is a jazz album,” he said. “Since African Rhythms in 1975, all of my albums have been eclectic. Many genres.” Plunky, who turns 78 in July, collaborated on the album with a vibrant circle of young musicians and producers. “They keep me young.”

Jamal Gray, son of Jimmy Gray, produced seven tracks on the album. Plunky was deeply inspired by the samples and sonic textures Gray introduced during their creative process. “I put together those songs from the tracks that Jamal and the other producers made and then created this album of material that comes off very much like vanguard jazz music,” he said. “Some of it feels like free jazz. Some of it is rhythmic, like Afro-jazz.”

Plunky’s son and longtime collaborator, Jamiah “Fire” Branch, is also a featured producer. The elder Branch made a point of inviting emerging producers from Rich-

mond as well, including DJ Punisha and Bee Boy$oul.

The album came together over six months in 2022.

Three years later, it will officially debut on Plunky Day, July 19. Established by the City of Richmond in 2024, Plunky Day honors his lifetime contributions to music. This year’s celebration includes a concert and ceremony at the Dogwood Dell Amphitheater—the day before Plunky’s 78th birthday. “It’s going to be a day of guests, local stars, blues artists, the poet laureate of the city, young R&B artists, and [Okyerema] Asante, in addition to Plunky & Oneness,” he said. “It’s going to be a grand affair. I just hope it can all fit into a two-hour presentation on July 19.”

Plunky Day isn’t his only summer show. On June 21, Plunky & The Oneness of Juju will perform at the 2025 Home Rule Music Festival, an annual celebration of Black music held at The Parks at Walter Reed in Washington, D.C.

Plunky has cultivated a deep connection with the Home Rule Music and Film Preservation Foundation, the nonprofit behind the festival. He was an executive producer of The Black Fire Documentary, which premiered on PBS in 2022. He also enjoys working with Home Rule’s Executive Director, Charvis Campbell, who owns Home Rule Records and co-produced the documentary. “He extends himself to preserving our history—both through music and now film,” said Plunky. “He and I have collaborated on those projects and continue to collaborate. And I’m back now for the fourth festival. I’m excited to come work with him again.”

James “Plunky” Branch in London. April 2025. photo credit: Courtesy of Alexis Maryon/Strut Records

James “Plunky” Branch in London. April 2025.

photo credit: Courtesy of Alexis Maryon/Strut Records

Don’t Mute DC Turns

Up the Volume in 2025

Don’t Mute DC starts a new chapter with the Go-Go Museum & Café

By: Phillip Kulubya

On a warm Thursday night, the new Go-Go Museum & Café was packed to the brim as Backyard Band performed hit after hit for a crowd of ecstatic Go-Go fans. On that day, April 10, 2025, the museum was the site of a sold-out and highly important event—the sixth anniversary of the #DontMuteDC movement. Go-Go Museum & Café founder and CEO Ronald Moten felt there was no better place to celebrate the movement and organization that made the museum a reality.

Prior to the Go-Go Museum & Café’s opening on Feb. 19, 2025, Go-Go music—a genre indigenous to Washington, D.C.—had been criminalized and silenced for decades. The versatile genre incorporates African percussion as well as elements of Black music genres like R&B and funk.

Chuck Brown, the famed guitarist and leader of the band

Chuck Brown & the Soul Searchers, invented Go-Go music in 1976. Trouble Funk, led by bassist and vocalist Tony “Big Tony” Fisher, was another trailblazing Go-Go band founded in the 1970s that helped shape the genre.

After the release of Go-Go songs like Chuck Brown & the Soul Searchers’ 1979 hit “Bustin’ Loose,” a number of talented Go-Go bands emerged on the scene. The 1980s brought bands like Junkyard Band and Mass Extension, who quickly added to the genre’s sound and cultural relevance. Alona Wartofsky, a freelance journalist who has covered Go-Go for decades, has fond memories of this time. Wartofsky refers to the mid-1980s as “Go-Go’s golden age.” “Anywhere downtown, it’s just like you couldn’t be

outside for an hour without hearing Go-Go from somebody’s car—like every car that would drive by, they’d be playing Go-Go. And it just sort of felt like the culture was so energetic, and it was new, and it was exciting, and everybody loved it.” Many bands were made up of young people from different D.C. neighborhoods who often performed at all-ages shows. Moten remembers the excitement around these youth-centered events.

“That was the way we fell in love with Go-Go,” Moten said. “You were exposed to it, not only in the house with your parents, but you got to get away from your parents to go experience it with your friends.” Soon, Go-Go music was thriving on the radio and in D.C.’s clubs. But while it reached new heights in the 1980s, the genre also faced many obstacles—both then and beyond.

In 1987, D.C. Councilmember Frank Smith Jr. introduced and ultimately passed a bill that banned people under the age of 18 from attending Go-Go dance halls late at night. Smith believed the curfew was justified due to instances of youth violence that had taken place at Go-Go venues.

Over the years, the city’s repression of Go-Go music took even more harmful forms. According to a 2019 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, between 2000 and 2013, more than 20,000 Black D.C. residents were displaced due to gentrification. Unsurprisingly,

LEFT: The Go-Go Museum & Café’s ribbon-cutting ceremony. Nov. 18, 2024.

Photo: Courtesy of Sam Johnson III/SamJohnson3 Photography

this shift affected how and where Go-Go music could be played in the city’s changing neighborhoods.

Tensions around the silencing of Go-Go music intensified in April 2019, when the Metro PCS store in D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood stopped playing Go-Go music due to a noise complaint from the residents of a new condo. The store, located at 7th Street and Florida Avenue NW, had played Go-Go for years. Longtime residents of Shaw were shocked that the store caved to the demands of its parent company, T-Mobile, and city officials.

On April 7, 2019, activist Ronald Moten and journalist and author Dr. Natalie Hopkinson launched the #DontMuteDC movement to restore Go-Go music at the Metro PCS store and preserve Go-Go culture amid D.C.’s ongoing gentrification.

Moten, Hopkinson, and a host of supporters organized protests and rallies while amplifying the movement on social media. A Change.org petition associated with the campaign ultimately garnered 80,115 signatures. T-Mobile eventually agreed to bring Go-Go music back to the Metro PCS storefront.

Hopkinson was grateful for the support of D.C. Councilmembers like Robert White and Kenyan McDuffie. “They were happy that we were speaking up, because it allowed them to be able to support us. Like usually in politics, the loudest, the squeakiest wheels get the oil. And thanks to the amazing fans of Go-Go, we were able to make a lot of noise. And it was almost immediate.”

Moten echoed the sentiment. “It gave politicians a backbone. Normally what happens is politicians will stick their neck out for their people, but then get chewed out in City Hall, as if it was a crime to help their own people.”

The success of Don’t Mute DC paved the way for the opening of the Go-Go Museum & Café. Moten, who had been talking about the idea of a Go-Go museum since 2009, felt that 2019 was the perfect time to work toward making it a reality.

On Feb. 19, 2020, Mayor Muriel Bowser signed the GoGo Music of the District of Columbia Designation Act of 2019, officially naming Go-Go as D.C.’s official music. The bill, introduced by Councilmember McDuffie, also included a plan to create a Go-Go museum to help preserve the city’s musical legacy.

Since its opening, the museum has hosted several events that celebrate the genre’s past, present, and future.

Junkyard Band and Backyard Band both performed at the ribbon-cutting ceremony on Nov. 18, 2024. On March 27, 2025, the museum hosted the “First Ladies of Go-Go” concert, featuring artists like Kimise “Songbird” Lee and J’TA performing for a multigenerational audience.

While the Go-Go Museum & Café is now a key performance venue, many of the genre’s historic spaces have closed. The historic Panorama Room and Howard Theatre still stand, but iconic venues like Chapter 3 in Southeast D.C. and Cheriy’s in Southwest D.C. are no more.

One particularly significant venue that shuttered its doors was Celebrity Hall—also known as The Black Hole.

In the 1980s, Rare Essence regularly performed at this popular Georgia Avenue venue, which was among those targeted by the 1987 youth curfew bill.

Charles C. Stephenson Jr., an author and former manager of the Go-Go band Experience Unlimited, believes the curfew and other anti-Go-Go legislation directly contributed to the closing of these spaces. “The government leaders took the easy way out. They started to scapegoat these bands for being responsible for the negative activity that was happening in our community.”

Despite the loss of venues, there is renewed excitement

about Go-Go music and where it’s being played. THR0W Social, a tropical-themed venue founded in 2017, regularly features Go-Go performances. UCB (Uncalled 4 Band) and TOB (TakeOvaBand) were on its May 2025 schedule.

of musicians and changemakers. “I’m proud to say that since the movement, there are young Go-Go bands now. There are a lot of young people who engage in activism and understand the power and purpose that they have as young people—and have had throughout history. But we still got a long way to go. So, I’m just going to always be here as a mentor to do that.”

As the Go-Go Museum & Café continues its mission, Moten is passionate about mentoring the next generation

Home Nightclub, 2004

Photo Courtesy: The Washingtonian

Little Benny & the Masters onstage in 1988.

Photo Courtesy: The Washingtonian, Credit: Thomas Sayers Ellis.

CapitalBop at 15: Still ‘taking care of us’

By: Jackson Sinnenberg

Since the 1910s, when pianist Jelly Roll Morton ragged Italian opera arias – playing the classical in the new ragtime style – the driving ideal behind the music we call jazz has been to “make it new.”

So the same is for CapitalBop, the non-profit organization devoted to presenting, preserving and promoting jazz in the District of Columbia, which celebrates 15 years of operation and service this September. (Disclosure: I have been a staffer for 10 of those 15 years).

“In addition to giving people all the information they might need to hear the music, we also felt like there was a need to reinvigorate the way people were experiencing the music,” CapitalBop co-founder and Editor-in-Chief Giovanni Russonello told NPR’s Jazz Night in America in 2016.

Those two ideas were front of mind for Russonello and Co-Founder and Artistic Director Luke Stewart when the two got together after the Rosslyn Jazz Festival in 2010. Russonello was a lifelong Washingtonian just-returning from undergraduate years at Tufts University in Boston. An aspiring pianist-turned aspiring journalist, he wanted

to begin highlighting the scene somehow. He started a google calendar and website – capitalbop.com – to begin listing jazz shows in the city.

At the same time, Stewart, a Mississippi-native who attended American University after Hurricane Katrina decimated his hometown, knew that there was a mismatch in the kind of world class musicianship that could be seen in the city and the number of ears hearing it. During his undergraduate years – Stewart told the Washington Post in 2012 – he wandered into (now closed) Twins Jazz to see veteran bop, fusion and free saxophonist Sonny Fortune.

“He was playing burning tempo [stuff] and I had never seen anybody do that. It blew my mind,” Stewart told the Post. “And there were only five people in the room.”

And even if people knew about the shows going on, the more traditional dine and listen model for clubs and

restaurants hosting shows could be a turn off to people without those means. For Stewart, the jazz club had “for a lot of younger people, somewhat oppressive conditions in terms of the price, in terms of ‘you have to be 21’,” he told NPR. “You have to really take a chance on your wallet.”

Stewart and Russonello had met one night at Bossa over the summer of 2010 and reconnected at the Rosslyn Jazz Festival. They both saw the potential to bolster each other’s vision. “Out of that... and starting to work with him [Luke]... came some broader ideas about cross-pollinating the scenes operating in DC — straight-ahead, avant-garde, fusion, jazz/punk, etc. — by doing shows, videos, etc.,” Russonello told the HR Zine in an email. (Engaging in that kind of work would also put Stewart and Russonello firmly in a legacy of egalitarian and do-it-yourself ethos key to D.C.’s hardcore punk scene starting with the Bad Brains in the late 1970s and crystalized by the band Fugazi. Fugazi insisted on all-ages shows and doing as much of their tours as DIY as possible so as to keep ticket prices close to $5-7.)

During CapitalBop’s first five years, Stewart and Russonello were blogging the scene for the burgeoning web -

site, reviewing local albums and live sets while also interviewing and reviewing national figures like Larry Willis and Sonny Rollins as they came to town. Photographer Paul Bothwell helped push the organization’s visual presence on web, social media and YouTube while volunteers Charmaine Nokuri and Jennifer White Torres helped build the website CapitalBop used until April 2025.

At the same time, they started presenting the contemporary scene in all of its evolutions both in person through shows. They would host performances by local acts at Red Door, an artist-run studio space near the convention center. When Red Door closed, shows moved to the Dunes on 14th Street NW and then Union Arts, a now-shuttered multi-studio space for visual and performing artists.

Even in those early days, CapitalBop was thinking in terms of what artists wanted to present less what audiences might think they want to hear. It was at CB’s prompting, in fact, that bassist Kris Funn – then known for traveling the world with Kenny Garrett and trumpeter Chief Xian aTunde Adjuah – organized and performed his first show

as a bandleader with his group “Corner Store” (the group’s first album was CapitalBop’s #1 D.C. Jazz Album of 2016).

“So often you hear, ‘We saw you doing this, and that got a big reaction, so why don’t you do a little bit of that?’,” drummer Dana J. Hawkins told the Post in 2018. “It’s not even close to that with CapitalBop. It’s, ‘That’s what you want to do? Come do it with us’.” While the main home for CapitalBop was places like Red Door or Union Arts, these other spaces became equally important as part of the “D.C. Jazz Loft” – as the monthly shows were branded. The name was based off of the loft scene in late 1970s New York, when the then-contemporary incarnations of the avant-garde would play in musicians’ and artists’ loft apartments in Manhattan (and were often the only place they could). [Saxophonist David Murray discussed his experience in the loft scene in the first issue of this zine]

“Every June when the DC Jazz Fest would roll around we did little fundraisers,” Russonello recalled. “The first few years via Kickstarter, and presented some bigger names from out of town on double bills with local heavies at little DIY venues, galleries, empty retail, spaces, etc.”

The festival eventually started handing CapitalBop a grant to help facilitate those shows for the festival’s main programming weekends. That model, and the first era of CapitalBop, arguably reached a pinnacle in the summer of 2015 when CapitalBop presented three high-profile shows in a pipe-and-draped DIY jazz club in the Old Hecht Warehouse as part of that year’s D.C. Jazz Festival.

The first night featured a trio of local trios and was filmed for Jazz Night in America; the second was a dance party helmed by then-breaking out bassist and singer Thundercat; and finally, a salute to the 50th anniversary of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) featuring flautist Nicole Mitchell.

This writer joined CapitalBop in September of 2015, having just graduated Georgetown University with a music degree and unsure how to make journalism a career. The organization was about to go through a major shake-up as Russonnllo was moving to New York to start a job with the New York Times and Stewart was beginning to take off nationally and internationally as a bassist of renowned. I took over much of the website, creating the monthly show calendar and writing every review and conducting every interview I could. Through 2018, with Russonello documenting New York’s jazz scene for the Times and Stewart increasingly called to tour, the presenting slowed to four times a year, usually a double bill of an out-of-town headliner and local opener.

Following the 2018 D.C. Jazz Festival, CapitalBop reorganized with former intern Jamie Sandel taking the reigns as managing director – also the website would start paying contributors for writings and interviews – all thanks to a grant from the Doris Duke Foundation. With Sandel as the first full-time paid staffer in the organization’s history, CapitalBop got back to regular presenting again for the first time since Union Arts closed in the fall of 2016. And since that time, as the scene often has, the landscape had

changed quite a bit. Early into CapitalBop’s existence, the U Street mainstay Café Nema closed – as did the jazz club HR-57. Bohemian Caverns had closed in the spring of 2016 in a major blow to the scene. Gentrification was accelerating, snapping up many of the spaces CapitalBop used to present at and used to give musicians a place to just play. So, CapitalBop partnered with a new bulwark of the scene – Rhizome – to relaunch the monthly D.C. jazz loft in Takoma Park. At the same time, the organization sought to bolster the dwindling historic space for jazz on U Street. So, in August of 2018, CapitalBop launched its Spotlight Residency at Local 16 – a now-shuttered, multi-level lounge, Afghan restaurant and club at 16th and U. Trombonist and educator Reginald Cyntje was the first resident of the program, which had a simple premise: allow D.C. musicians to present their music as they want in this dedicated space.

“CapitalBop was community, it’s for us all,” musician and activist Alex Hamburger (also CapitalBop’s current managing director) told the HR Zine. “In the activist spaces we say the phrase ‘we take care of us’ and I think that CB has always embodied that for the D.C. jazz/creative music/Black [American] Music scene.”

In 2019, CapitalBop also hired Patrick Jarenwattananon, who had helmed NPR Music’s jazz coverage for many years, as Managing Editor. Under Russonello and Jarenwattananon’s guidance, I also led the website into more hard news coverage of the scene, whether it was the launch of a new series at a restaurant or covering the D.C.

Council’s perennial attempts to effectively outlaw amplified street performances. Jarenwattananon also suggested the start of the “5 Picks” column to highlight more of the calendar, which runs on the first of every month.

Things were building and then, well, the world ground to something close to a stand still in March 2020 with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. CapitalBop pivoted the best it could: the calendar would now list livestreams musicians, venues and studios organized; the blog covered the lived experiences of musicians, venue operators and programmers; the website directed folks to resources best they could; and we would try to host livestreams best we could; later Sandel would produce mini-documentaries on some of the venues that shuttered because of the pandemic like Twins and Alice’s Jazz and Cultural Society.

Post-pandemic, the organization went through more reshuffling. Sandel was in-demand as a photographer and videographer – and sometimes touring musician – so needed to step back from the reigns. The editorial output had been 90% my byline since late 2015 and I was finally finding full-time work as a journalist in my day job. CapitalBop sought new energy in the form of executive director Jeanette Berry, a vocalist and educator, who unfortunately remained with the organization for only a few months. In many ways, the post-pandemic years for CapitalBop have been years of building. “The past three years have been dedicated to building infrastructure and defining CB’s vision while its co-founders and part-time staff juggle multi-

ple professions and priorities,” said Sara Donnelly. Donnelly, a longtime activist and advocate for the music, has been a CapitalBop board member for well over a decade and served as interim executive director for the last two years.

On the web front, the addition of A.M. Wolfe as assistant then associate editor allowed the editorial team greater flexibility. The team also sought to follow through on a long-standing desire of having more people contribute to the site. That allowed for more contributions from the likes of Dr. Thomas Stanley, the celebrated Black American Music scholar and advocate, as well as Dr. Joshua Myers of Howard University, who is now contributing editor and a leading voice of the coverage. Presenting-wise CapitalBop has been taking deliberate steps in when and what it produces such as artists with the Home Rule Festival or shows like the Matthew Shipp Trio and Mendoza-Hoff Revels – which featured CapitalBop’s first partnership with storied alt rock venue the Black Cat. In terms of the future,

Russonello knows CapitalBop needs to make sure that music remains part of the conversation of D.C.’s identity among ever-changing times. “D.C. has a whole different landscape and constitution these days,” he told HR Zine.

“The music needs to stay part of the conversation, for the benefit of our communities and especially young people. We also need to foster resources and communities that remember the paths this music has traveled through D.C. history, ways of thinking and doing that it has opened up.”

Part of the concern from Donnelly’s perspective comes as the second Trump administration whirlwind of question-

ably legal and constitutional actions impact every aspect of life in the city and region. “At this time, the music community and arts landscape at large are facing all of the negativity that the current administration is causing. Most feel that all organizations are operating on shaky ground due to funding cuts.” As the one overseeing the day-today helm, Hamburger thinks CapitalBop’s commitment to the community it is deeply intertwined with and serves –and meeting its needs on multiple levels – will continue to propel its work forward. “I think CB has had many different roles throughout the years and it’s been very adaptable to change with the changing times for this music and the city,” she explained. “I think the three pillars of our mission, presenting, preserving and promoting, can be summed up as supporting the past, present and future of this music.

“The opportunity to experiment, challenge our perceptions, teach the next generation and most importantly be together in community to uplift each other are so vital,” she adds, “And CapitalBop has always made a space for everyone to be a part of that.”

Jackson Sinnenberg is the Editor at Large and Senior Correspondent for CapitalBop. While he interviewed CapitalBop leadership for this article, no one in executive or editorial leadership had any say in the writing or editing of this article.

Sinnenberg is also the Morning Edition producer for WAMU 88.5, D.C.’s NPR News station.